Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive performance; Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is instead an objective decline in cognitive performance that does not reach pathology. Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRA) is a cell surface inhibitory receptor that was recently suggested to be involved in AD pathogenesis. In particular, the arginine-to-glycine substitution in position 78 (R78, rs1859788) was shown to be protective against AD. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection is suspected as well to be involved in AD. Interestingly, HSV-1 uses PILRA to infect cells, and HSV-1 infects more efficiently PIRLA G78 compared to R78 macrophages. We analyzed PILRA rs1859788 polymorphism and HSV-1 humoral immune responses in AD (n = 61) and MCI patients (n = 48), and in sex and age matched healthy controls (HC; n = 57). The rs1859788 PILRA genotype distribution was similar among AD, MCI and HC; HSV-1 antibody (Ab) titers were increased in AD and MCI compared to HC (p < 0.05 for both comparisons). Notably, HSV-1-specific IgG1 were significantly increased in AD patients carrying PILRA R78 rs1859788 AA than in those carrying G78 AG or GG (p = 0.01 for both comparisons), and the lowest titers of HSV-1-specific IgG1 were observed in rs1859788 GG AD. HSV-1 IgG are increased in AD patients with the protective R78 PILRA genotype. Because in AD patients brain atrophy is inversely correlated with HSV-1-specific IgG titers, results herein suggest a possible link between two important genetic and infective factors suspected to be involved in AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: HSV-1, Alzheimer’s disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, IgG1, Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRA)

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is an inflammatory and chronic neurodegenerative disease, characterized by behavioral abnormalities, progressive decline in cognitive performance, and loss of normal ability to function of activities in daily living (McKhann et al. 2011). Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) presents an objective decline in cognitive performance, greater than normally expected, but that cannot be defined as pathological (Tangalos and Petersen 2018). The etiopathogenesis of AD is still not known but is very likely due to the interaction among several factors. Genetics is one of these factors, as many genes are associated with the disease, though the only known confirmed genetic risk factor is the Apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE) (Roses 1998).

Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRA) (Rathore et al. 2018) was recently suggested to play an important role in AD. PILRA is a cell surface inhibitory receptor expressed on innate immune cells, including microglia, that recognizes specific O-glycosylated proteins (Mousseau et al. 2000); the interaction down-regulates inflammation (Wang et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2014; Kohyama et al. 2016). The PILRA gene is characterized by the rs1859788 A/G polymorphism that causes the 78 aa substitution of Glycine (G), coded by the G allele, with Arginine (R), coded by the A allele. The rs1859788 SNP was shown to be an AD risk locus (Lambert et al. 2013), and, in particular, R78 was suggested to protect against AD development and progression (Rathore et al. 2018). Notably, PILRA inhibits microglial activation via PILRB/DAP12 signaling (Mousseau et al. 2000): the R78 substitution alters the access to SA-binding pocket in PILRA, reducing the binding capacity of cellular endogenous ligands including PIANP and NPDC1, thus increasing microglial activation (Wang et al. 2014, Kohyama et al. 2016).

Infections are also hypothesized to contribute to the etiopathogenesis of AD (Itzhaki et al. 2016); human herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), in particular is strongly suspected to be a major actor in AD (Ball, 1982; Agostini et al. 2017; Harris 2018). We observed that HSV-1 IgG titers positively correlate with grey matter volumes in AD patients (Mancuso et al. 2014a; Agostini et al. 2018) and that in MCI individuals HSV-1-specific IgG avidity is inversely correlated with the likelihood of AD conversion (Agostini et al. 2016), suggesting that HSV-1 specific antibodies play a protective role against the disease.

HSV-1 and PILRA are functionally connected as this virus binds to PILRA to infect cells (Satoh et al. 2008). Notably, very recent results showed that HSV-1 infects much less successfully R78 compared to G78 macrophages, suggesting that brain microglia of R78/R78 people might be less susceptible to the virus infection and more prone to defend itself during HSV-1 recurrence and reactivation (Rathore et al. 2018).

We analyzed whether HSV-1-specific humoral immune responses could be correlated with polymorphisms on PILRA (G78R) gene in AD and MCI.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Controls

One-hundred-sixty-six HSV-1 seropositive individuals were included in the study: 61 AD patients, 48 MCI individuals, and 57 sex and age matched healthy controls (HC). All subjects were recruited by the Rehabilitative Neurology Unit of the IRCCS Santa Maria Nascente, Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi—ONLUS, in Milan, Italy. Patients were diagnosed with probable AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria (McKhann et al. 2011) or with MCI according to Petersen criteria (Petersen 2004). The cognitive status of HC was assessed by administration of MMSE (score for inclusion as normal control subjects > 28). The study conformed to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki; all subjects or their legal guardians gave informed and written consent according to a protocol approved by the local ethics committee of the Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi—ONLUS.

Quantitation of HSV-1 Serum Total IgG Titers and IgG Subclasses

HSV-1-specific IgG titers were measured in sera by using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (IBL International, Hamburg, German), according to standard protocol. Optical densities (OD) were determined at 450/620 nm. HSV-1 IgG titers were expressed as antibody index (AI), calculated by dividing OD measurement generated from the assay by OD cut-off calibrator. Subjects with AI > 1.1 were seropositive, whereas subjects with AI < 0.9 were seronegative. If the results were in grey zone (AI between 0.9 and 1.1), the tests were repeated in triplicated and, if the results remained in grey zone, the subjects were excluded from the study. Quantitation of the four different HSV-1 IgG subclasses was carried out by ELISA using subtype-specific monoclonal antibodies, as previously reported (Agostini et al. 2018).

PILRA and ApoE Genotyping

Custom-designed TaqMan probes were used for the PILRA rs1859788 polymorphism genotyping by allelic discrimination using Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, US). Primers and probes are: Forward primer: 5′-GCT CCC GAC GTG AGA ATA TCC-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-GCG GCC TTG TGC TGT AGA A-3′; Reporter 1 sequence: HEX 5′-ACT TCC ACG GGC AGT C-3′- MGBEQ; Reporter 2 sequence: FAM 5′-ACT TCC ACA GGC AGT C-3′-MGBEQ. Regarding ApoE, custom-design TaqMan probes for the 112 and 158 codons were used to determine the genotype, as reported in our previous study (Costa et al. 2017).

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed data were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD), and comparison among groups were analyzed by ANOVA test and Student t test. Not-normally distributed data were summarized as median and Interquartile Range (IQR: 25th and 75th percentile), and comparisons were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Qualitative data were compared using Fisher’s exact test. The statistical analyses were accomplished using commercial software (MedCalc Statistical Software version 14.10.2, Ostend, Belgium). p value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characterization of Study Subjects

Gender and age were comparable in the three groups examined; global cognitive levels (MMSE) were, as expected, significantly reduced in AD and MCI compared to HC (p < 0.0001) and in AD compared to MCI (p < 0.0001). A significantly higher frequency of ApoE ε-4 carriers was detected in AD (p = 0.003) and MCI individuals (p = 0.008) compared to HC. Demographic and clinical characteristic of the individuals enrolled in the study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the individuals enrolled in the study

| AD patients | MCI subjects | Healthy controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 61 | 48 | 57 |

| Gender (M:F) N | 25:36 | 22:26 | 23:34 |

| Age, years mean ± SD | 76.5 ± 6.3 | 73.7 ± 5.7 | 70.0 ± 8.0 |

| MMSE mean ± SD | 19.1 ± 4.3^ | 25.3 ± 2.4^ | 29.0 ± 0.6 |

| APOE ε-4 carriers (%) | 43* | 26* | 18 |

| HSV-1 Ab titers (AI) | 8.9 | 8.8 | 7.5 |

| Median and IQR | (2.8–13.3)° | (3.9–14.3)° | (1.3–11.7) |

N Absolute number, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI Mild cognitive impairment, M Male, F Female, N Absolute number, SD Standard deviation, MMSE Mini mental state evaluation, APOE Apolipoprotein E, AI Antibody index, IQR Interquartile range

*p < 0.01 compared to HC

^°p< 0.0001 compared to HC

°p < 0.05 compared to HC

HSV-1 Antibody Titers and IgG Subclasses

As per definition of enrollment, all the studied subjects were HSV-1 seropositive. HSV-1-specific IgG titers were significantly increased in AD (median; IQR: 8.9; 2.8–13.3 AI) and MCI individuals (8.8; 3.9–14.3 AI) compared to HC (7.5; 1.3–11.7 AI; p < 0.05 for both comparisons) whereas no differences were observed among the three groups regarding IgG subclasses.

PILRA rs1859788 Genotype Distribution

Molecular genotyping analyses showed that the PILRA (A/G) rs1859788 polymorphism genotype distribution was in Hardy–Weinberg (HW) equilibrium. Genotype and allelic analyses showed that PILRA rs1859788 was not differently distributed among AD, MCI, and HC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype distribution of PILRA rs1859788 SNP in the study population

| PILRA rs1859788 | AD patients | MCI subjects | Healthy controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| AA | 7 | 11.5 | 1 | 2.1 | 7 | 12.3 |

| AG | 22 | 36.1 | 24 | 50.0 | 22 | 38.6 |

| GG | 32 | 52.4 | 23 | 47.9 | 28 | 49.1 |

| Total | 61 | 48 | 57 | |||

AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI Mild cognitive impairment

Association Between PILRA rs1859788 Genotype and HSV-1-Specific Humoral Immunity

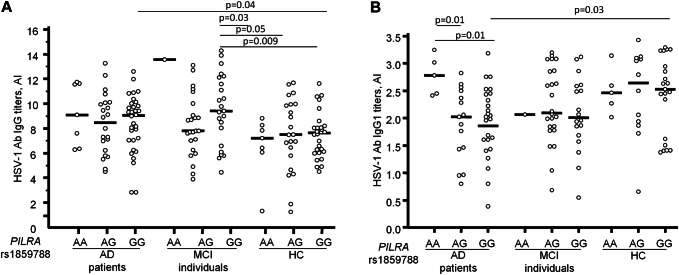

As PILRA is a key protein in the process of HSV-1 entry and infection of cells, possible associations between HSV-1 IgG and PILRA genotypes were evaluated. Results showed that higher HSV-1-specific IgG titers (9.04; 2.8–12.6 AI) were seen in AD patients and MCI individuals (9.40; 4.43–14.29 AI) carrying the rs1859788 GG genotype which codes for the G78 residue compared to HC carrying the same genotype (7.6; 4.5–11.6 AI, AD vs. HC: p = 0.04; MCI vs. HC: p = 0.009). Interestingly, MCI individuals carrying the rs1859788 GG genotype showed higher HSV-1-specific IgG titers compared to all the HC groups, regardless the rs1859788 genotype (p ≤ 0.05 for each comparison). However no differences in HSV-1-specific IgG titers were observed inside each group when stratified for the rs1859788 genotype. All these results are represented by Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of serum HSV-1-specific IgG titers (panel A) and IgG1 titers (panel B) in AD, MCI and HC subjects according to PILRA rs1859788 genotypes. AI Antibody index, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI Mild cognitive impairment, HC Healthy controls

When HSV-1 IgG subclasses were considered, associations between IgG1 and the PILRA rs1859788 genotype were found. In particular, considering each group, AD patients carrying rs1859788 AA were characterized by significantly higher IgG1 titers (2.78; 2.41–3.24) compared to AD carrying either the AG (2.03; 0.80–2.82) or the GG (2.02; 0.39–3.19; p = 0.01 for both) genotypes. Finally, significantly lower IgG1 titers were seen in AD patients carrying rs1859788 GG compared to HC who carried the same genotype (2.53; 1.38–3.29; p = 0.03) (Fig. 1b). No correlations could be detected between PILRA genotypes and either IgG2, IgG3, or IgG4 HSV-1-specific antibody subclasses (data not shown).

Discussion

HSV-1 has long been suspected to be involved in AD onset and development; recent results showing that HSV-1-specific humoral responses differ in AD and MCI patients compared to HC (Lovheim et al. 2015; Agostini et al. 2017) suggest that the quality of humoral response may be important for the development of disease.

We focused our attention on PILRA, a protein expressed on the surface of human cells which is used by HSV-1 to infect cells through the interaction with its gB protein, and whose engagement results in an inflammation-inhibitory signal (Satoh et al. 2008). Recent results indicated that the rs1859788 SNP R78 PILRA variant might be protective against AD (Rathore et al. 2018), possibly because of a reduced inhibitory signaling in microglia and/or a reduced susceptibility of the microglia to HSV-1 infection upon viral reactivation.

Based on these data, we verified whether there is a relation between the host HSV-1-specific humoral immunity and the PILRA G78R variant. Initial results confirmed that AD patients and MCI individuals are characterized by higher HSV-1-specific IgG titers compared to HC. Stratification for rs1859788 SNP showed that the differences remain statistical significant only between AD and HC carrying the PILRA GG genotype, probably because this is the most common variant for each group. Notably, HSV-1-specific IgG1 titers were significantly increased in AD patients with the rs1859788 AA genotype compared to those with the AG or GG genotypes. These differences were not seen in either MCI or HC.

The hypothesis that PILRA rs1859788 AA genotype is protective against AD was reinforced by our results indicating that the AA genotype is indeed very rare in AD and MCI patients; these differences were not statistically significant upon comparison with HC, probably because of the small number of individuals examined.

The temporal and orbito-frontal cortices were shown to be better preserved in those AD patients in whom higher HSV-1-specific titers are detected (Mancuso et al. 2014a, b), because IgG1 is the most abundant IgG subclass (Gilljam et al. 1985), we can hypothesize that AD patients with high IgG1 titers are characterized by lesser brain damage. Results herein show that those AD patients with the “protective” PILRA R78 (AA) rs1859788 genotype are the same in whom higher HSV-1-specific IgG1 titers are present. Conversely, AD patients without the protective PILRA genotype also have lower IgG1 titers.

Results herein, although preliminary and needing confirmation in bigger cohort of patients, indicate the presence of intriguing interactions between distinct genetic and environmental risk factors suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of AD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 2018–2019 Ricerca Corrente (Italian Ministry of Health).

Author Contributions

MC, SA, and ASC designed the experiment; RN recruited subjects and collected biological samples; ASC, RM, and SA performed experiments and data collection; ASC, FG, and SA analyzed the data; and MC, ASC, and SA interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi—ONLUS committee (reference number: 12_21/06/2018) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants, or their legal guardians, included in the study.

Research Involving Animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Simone Agostini and Andrea Saul Costa have contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- Agostini S, Mancuso R, Baglio F, Cabinio M, Hernis A, Costa AS, Calabrese E, Nemni R, Clerici M (2016) High avidity HSV-1 antibodies correlate with absence of amnestic mild cognitive impairment conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 58:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostini S, Mancuso R, Baglio F, Clerici M (2017) A protective role for herpes simplex virus type-1-specific humoral immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 15:89–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostini S, Mancuso R, Hernis A, Costa AS, Nemni R, Clerici M (2018) HSV-1-specific IgG subclasses distribution and serum neutralizing activity in Alzheimer’s disease and in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 63:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MJ (1982) Limbic predilection of Alzheimer’s dementia: is reactivated herpes virus involved? Can J Neurol Sci 9:303–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa AS, Agostini S, Guerini FR, Mancuso R, Zanzottera M, Ripamonti E, Racca V, Nemni R, Clerici M (2017) Modulation of immune responses to herpes simplex virus type 1 by IFNL3 and IRF7 polymorphisms: a study in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 60:1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilljam G, Sundqvist VA, Linde A, Philstedt P, Eklund AE, Wahren B (1985) Sensitive analytic ELISAs for subclass herpes virus IgG. J Virol Methods 10:203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SA, Harris EA (2018) Molecular mechanisms for herpes simplex virus type 1 pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 10:48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki RF, Lathe R, Balin BJ, Ball MJ, Bearer EL, Braak H, Bullido MJ, Carter C, Clerici M, Cosby SL, Del Tredici K, Field H, Fulop T, Grassi C, Griffin WS, Haas J, Hudson AP, Kamer AR, Kell DB, Licastro F, Letenneur L, Lovheim H, Mancuso R, Miklossy J, Otth C, Palamara AT, Perry G, Preston C, Pretorius E, Strandberg T, Tabet N, Taylor-Robinson SD, Whittum-Hudson JA (2016) Microbes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 51:979–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama M, Matsuoka S, Shida K, Sugihara F, Aoshi T, Kishida K, Ishii KJ, Arase H (2016) Monocyte infiltration into obese and fibrilized tissues is regulated by PILRα. Eur J Immunol 46:1214–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C et al (2013) Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 45:1452–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, Elgh F (2015) Reactivated herpes simplex infection increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11:593–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso R, Baglio F, Cabinio M, Calabrese E, Hernis A, Nemni R, Clerici M (2014a) Titers of herpes simplex virus type 1 antibodies positively correlate with grey matter volumes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 38:741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso R, Baglio F, Agostini S, Cabinio M, Laganà MM, Hernis A, Margaritella N, Guerini FR, Zanzottera M, Nemni R, Clerici M (2014b) Relationship between herpes simplex virus-1-specific antibody titers and cortical brain damage in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci 6:285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Moris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Reccomendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau DD, Banville D, L’Abbe D, Bouchard P, Shen SH (2000) PILRα, a novel immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing protein, recruits SHP-1 upon tyrosine phosphorylation and is paired with the truncated counterpart PILRb. J Biol Chem 275:4467–4474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC (2004) Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entry. J Intern Med 256:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore N, Ramani SR, Pantua H, Payandeh J, Bhangale T, Wuster A, Kapoor M, Sun Y, Kapadia SB, Gonzales L, Zarrin AA, Goate A, Hansen DV, Behrens TW, Graham RR (2018) Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha G78R variant alters ligand binding and confers protection to Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Genet 14:e1007427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roses AD (1998) Alzheimer diseases: a model of gene mutations and susceptibility polymorphisms for complex psychiatric diseases. Am J Med Genet 81:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Arii J, Suenaga T, Wang J, Kogure A, Uehori J, Arase N, Shiratori I, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi Y, Spear PG, Lanier LL, Arase H (2008) PILRα is a herpes simplex virus-1 entry co-receptor that associates with glycoprotein B. Cell 132:935–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Caplazi P, Zhang J, Mazloom A, Kummerfeld S, Quinones G, Senger K, Lesch J, Peng I, Sebrell A, Luk W, Lu Y, Lin Z, Barck K, Young J, Del Rio M, Lehar S, Asghari V, Lin W, Mariathasan S, DeVoss J, Misaghi S, Balazs M, Sai T, Haley B, Hass PE, Xu M, Ouyang W, Martin F, Lee WP, Zarrin AA (2014) PILRa negatively regulates mouse inflammatory arthtritis. J Immunol 193:860–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangalos EG, Petersen RC (2018) Mild cognitive impairment in geriatrics. Clin Geriatr Med 34:563–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shiratori I, Uehori J, Ikawa M, Arase H (2014) Neutrophil infiltration during inflammation is regulated by PILRA via modulation of integrin acitvation. Nat Immunol 2:860–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]