Abstract

The Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (PharmVar) serves as a global repository providing star (*) allele nomenclature for the polymorphic human CYP4F2 gene. CYP4F2 genetic variation impacts the metabolism of vitamin K, which is associated with warfarin dose requirements, and the metabolism of drugs, such as imatinib or fingolimod and certain endogenous compounds including vitamin E and eicosanoids. This GeneFocus provides a comprehensive overview and summary of CYP4F2 genetic variation including the characterization of 14 novel star alleles, CYP4F2*4 through *17. A description of how haplotype information cataloged by PharmVar is utilized by the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) and the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is also provided.

Introduction

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoform 4F2 (CYP4F2) was first identified in 19941 and shown to contribute to drug metabolism, the homeostasis of inflammation mediators, such as leukotriene B4 (LTB4), and the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids and other lipids2. It plays a key role in the vitamin-K dependent blood clotting process and is recognized as a pharmacogenetic biomarker associated with warfarin dose requirements3. CYP4F2 also contributes to the metabolism of drugs such as imatinib or fingolimod and certain endogenous compounds including vitamin E and eicosanoids. Moreover, CYP4F2 genetic variation has been suggested to be associated with an increased risk of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases due to impaired vitamin K metabolism and altered eicosanoid synthesis4-6. More extensive characterization of CYP4F2 genetic variation and variant function will help to understand its clinical impact not only on coagulation processes and warfarin response, but also on drug metabolism more generally. Additionally, deeper knowledge could potentially shed additional light into other cardiovascular processes. Therefore, further research in this area is warranted to assess drug-clinical phenotype associations, to ultimately conclude which interventions would be clinically relevant, promoting the implementation of precision medicine.

PharmVar serves as a global repository for pharmacogene variation7 cataloging variation within a defined gene region on the haplotype level, i.e., combinations of variants that occur together on the same chromosome using “star allele” nomenclature (a star allele describes a haplotype that can consist of one, few or many variants). The star allele nomenclature is widley used in the pharmacogenetics/genomics field including the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) and the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) which source star allele definitions from PharmVar. Star allele nomenclature is also widley used for pharmacogenetic test reporting.

CYP4F2 nomenclature was first provided by the Human Cytochrome P450 Allele Nomenclature Database, which was transitioned to PharmVar in 2017 8. At this time, only two star alleles were descibed, CYP4F2*2 and *3, defined by c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622)9, respectively. Their allele definitions did not follow current standards. Briefly, the current star allele system requires complete sequencing of defined regions that include all exons, exon/intron junctions, parts of —or the entirety of — the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTR), and additional upstream gene sequences. To identify haplotypes and provide a more comprehensive catalog of CYP4F2 allelic variation complying with current standards, PharmVar surveyed publicly available data from the 1000 Genomes Project (1K-GP)10. In addition, PharmGKB reanalyzed allele frequencies from the UK Biobank data11 to estimate star allele frequencies.

In this document, variants are described according to their relative position in the CYP4F2 NM_001082.5 reference transcript sequence with the “A” of the ATG translation start codon being +1 unless otherwise indicated. For example, the variants constituting the core CYP4F2*2, *3 and *4 allele definitions are referred to as c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622). Since this gene is encoded on the negative strand, the nucleotide changes in GRCh37 and GRCh38 are shown as their reverse complement, e.g., c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) is shown as 15897578A>C in the GRCh38 genome build.

PharmVar gene prioritization

Recently, a point-based rating system has been developed to prioritize genes for incorporation into PharmVar. Criteria used for consideration include, but are not limited to, PharmGKB clinical annotation levels, CPIC gene status, availability of CPIC clinical allele function status and the level of PharmVar curation efforts. With 90/100 points, CYP4F2 is among the high priority genes. More detailed information can be found in the “Gene Content and Prioritization” tab on the “GENES” page of the PharmVar website12.

Clinical relevance

CYP4F2, vitamin K, and coagulation

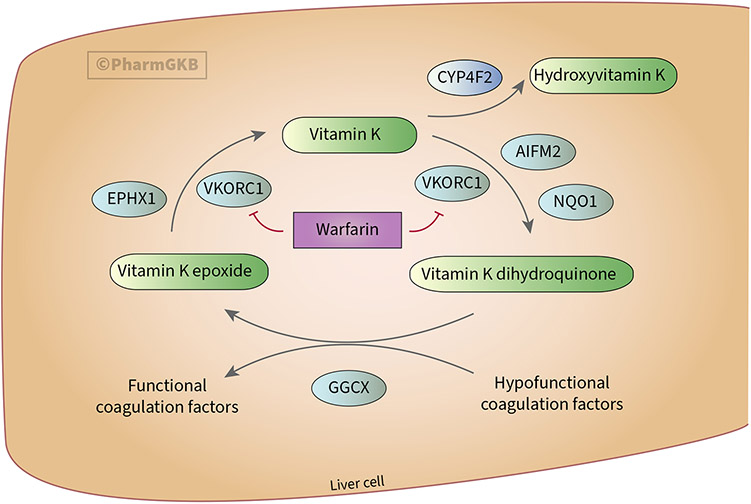

The coagulation process requires the carboxylation of hypofunctional clotting factors, which depends on the reduced form of vitamin K (i.e., vitamin K dihydroquinone)13. As shown in Figure 1, gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) mediates the carboxylation of hypofunctional coagulation factors and the simultaneous conversion of vitamin K dihydroquinone to vitamin K epoxide in the liver. Vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKORC1) then converts vitamin K epoxide to vitamin K and subsequently to vitamin K dihydroquinone in a 2-step reaction. Dietary vitamin K enters the cycle as a quinone, which is metabolized by CYP4F2 to hydroxyvitamin K, which is no longer part of the cycle; subsequent β-oxidation reactions of hydroxyvitamin K-derived compounds contribute to vitamin K elimination. In other words, vitamin K, VKORC1 and GGCX contribute to a procoagulant status by mediating the conversion of hypofunctional to functional coagulation factors, while CYP4F2 action favors an anticoagulant status by limiting vitamin K availability14.

Figure 1. Overview of the vitamin K cycle.

Figure adapted from PharmGKB warfarin pharmacodynamics pathway87 and used with permission. GGCX: gamma-glutamyl carboxylase; VKORC1: vitamin K epoxide reductase; EPHX1: epoxide hydrolase 1; AIFM2: apoptosis inducing factor mitochondria associated 2; NQO1: NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1.

Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are widely used anticoagulant drugs. By inhibiting VKORC1, VKAs limit the conversion of vitamin K epoxide to vitamin K, and vitamin K to vitamin K dihydroquinone, thereby limiting the production of functional clotting factors and causing an anticoagulant state. Patients with CYP4F2 variants that decrease function have less CYP4F2 enzyme activity, which increases the vitamin K pool in the cycle, thus contributing to a procoagulant status. Such patients require a 5-10% dose increase of the VKA warfarin3. Multiple studies and meta-analyses provide evidence supporting the influence of c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) on warfarin dose requirements3,15-19. This variant causes decreased function and is the most widely studied; it is the defining variant of the CYP4F2*3 allele and is also present on the novel CYP4F2*4 allele, which additionally has c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105). CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotyping prior to starting warfarin therapy can help to optimize dosing, along with clinical and demographic factors3. Acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon are other VKAs having the same mechanism of action as warfarin20. Though not approved for sale in the United States, they are widely used in several European countries (e.g., phenprocoumon is the most prescribed VKA in Germany [74.1%] and acenocoumarol in Spain [67.3%])15. Several studies suggest that CYP4F2 variation affects the dose requirements of acenocoumarol16-21 and phenprocoumon22-24 similarly to that of warfarin.

Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that individuals carrying c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) may have an increased risk of hypertension, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases due to impaired vitamin K metabolism and altered eicosanoid synthesis4-6, likely due to the procoagulant status associated with this variant. A possible sex-specific effect of c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) has been postulated due to its association with hypertension and ischemic stroke in males. While the underlying cause is still unknown, a complex interplay of several factors has been proposed; sex-specific factors such as hormone levels (e.g., testosterone levels) have been proposed to affect the CYP4F2-mediated metabolism of endogenous factors such as arachidonic acid, which underlays the excess of hypertension and associated vascular events observed in males compared to females25,26.

CYP4F2 substrates

Besides vitamin K, CYP4F2 is involved in the metabolism of several drugs. Imatinib is an anticancer drug that inhibits tyrosine kinases. It is mainly metabolized by CYP3A enzymes but CYP4F2 has been suggested to contribute to its biotransformation to desmethylimatinib27. Fingolimod is an immunomodulator used for multiple sclerosis management; CYP4F2 is reported to be one of the major enzymes in the elimination pathway of fingolimod in vivo28. The concomitant use of CYP4F2 inhibitors such as ketoconazole (which also inhibits other CYPs, such as CYP3A4) increases fingolimod exposure. Thus, if both drugs are co-administered, close monitoring of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is required, and, if necessary, a reduction of the fingolimod dose is advised29. Linezolid is an oxazolidinone antibiotic indicated for several gram-positive infections. CYP4F2 and CYP2J2 are reportedly responsible for 50% of its hepatic biotransformation in vitro30.

Vitamin E

A group of eight fat-soluble compounds that include four tocopherols and four tocotrienols is referred to as vitamin E. These tocopherols and tocotrienols exist as α (alpha), β (beta), γ (gamma), δ (delta), and ω (omega) counterparts. Neurological disorders are characterized by vitamin E deficiency contributing to poor conduction of nerve impulses. Studies show effectiveness of vitamin E supplementation in a variety of conditions, such as for the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease31; however, its excessive use has been related to platelet inhibition and increased risk for bleeding32. Similar to vitamin K, vitamin E metabolism begins with a ω-hydroxylation reaction which is followed by five subsequent β-oxidation cycles resulting in the formation of water-soluble end products33. A number of in silico, in vitro and in vivo studies support CYP4F2 as the main enzyme responsible for the initial ω-hydroxylation reaction, and that CYP4F2 variation, specifically c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622), impacts the ω-hydroxylation reaction, α-tocopherol levels, and/or vitamin E supplement dose requirements34-38. However, this association has not been observed with tocotrienols34 or γ-tocopherol levels39, and some studies suggest that the ω-hydroxylation step of vitamin E is not mediated by CYP4F240.

CYP4F function and expression

CYP4F2 catalyzes the NADPH-dependent oxidation of the carbon terminus of long and very long chain fatty acids, vitamin K and vitamin E side chains (tocopherols and tocotrienols), arachidonic acid and LTB414. Alade et al.41 observed a strong relationship between combined CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 protein abundance and ω-hydroxy phylloquinone formation from vitamin K in human liver microsomes, with similar intrinsic clearances and catalytic efficiencies.

Enzymes of the CYP4F subfamily are predominantly expressed in the human liver and, to a lesser extent, in small intestine and kidney42-44. CYP4F has been reported to represent up to 15% of all hepatic CYP protein content45. Wide ranges of hepatic and renal protein expression levels have been observed; however, the underlying mechanism(s) driving variable expression remain unknown45,46. These findings are in agreement with genome-wide expression databases such as the Human Protein Atlas47 and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project48.

Alade et al.41 investigated CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 mRNA expression, protein abundance, and metabolic activity in human liver samples and performed extensive modeling analyses. Key findings indicated that in most samples, CYP4F2 exhibited higher mRNA expression and protein abundance than CYP4F11. Furthermore, the CYP4F2*3-defining variant (c.1297G>A, p.V433M, rs2108622) was associated with decreased CYP4F2 protein levels. CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 protein abundances were strongly correlated with vitamin K intrinsic clearance, suggesting significant contributions from both enzymes to vitamin K metabolism in human liver. Quantifying the effect size of genetic variation in the CYP4F locus is complex due to the involvement of both CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 in the metabolism of substrates typically attributed to CYP4F2, but the authors concluded that interrogation of the CYP4F2 c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) variant is adequate for in vivo predictions, such as determining the warfarin dose required to achieve a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR).

A recent study by Sato et al49 characterized 28 CYP4F2 variants that were found in a large Japanese cohort, many of which are currently not catalogued by PharmVar. Each variant was heterologously expressed in vitro and amounts of expressed protein determined using carbon monoxide-reduced difference spectroscopy, and kinetic parameters and intrinsic clearance were assessed using arachidonic acid as substrate for measuring ω-hydroxylation. The c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) variant found in both CYP4F2*3 and *4 led to a significant reduction in holoenzyme content, resulting in a marked decreased in activity — an observation aligning with previous studies 9,34,50. Furthermore, 3D structural modeling revealed that the c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) alteration causes a loss of interaction with p.H103 in beta sheet 2, affecting enzyme stability and, consequently, activity49. In addition, Sato et al49 explored the amino acid changes c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) (CYP4F2*2 and *4), c.1555C>A (p.L519M, rs3093200) (CYP4F2*5) and c.322C>T (p.R108W, rs114396708) (CYP4F2*11). There was no detectable holoenzyme for p.R108W (CYP4F2*11) suggesting that this amino acid change may cause a severe loss or absence of CYP4F2 activity. The constructs containing p.W12G (CYP4F2*2 and *4) and p.L519M (CYP4F2*5) exhibited intrinsic clearances for ω-hydroxylation of 59% and 70%, respectively, compared to CYP4F2*1.

Inducibility and drug interactions

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug labels for acenocoumarol and warfarin, respectively, do not mention drug interactions with CYP4F2. Data supporting inhibition or induction of CYP4F2 by certain compounds are mainly derived from in vitro studies. For example, lovastatin, retinoic, lauric and stearic acids have been described to induce CYP4F251-53, whereas ketoconazole (but not the other members of the azole antifungal family)54, sesamine55 and peroxisomal proliferators, such as clofibrate, ciprofibrate or pentadecafluorooctanoic acid53 have been reported to inhibit the enzyme. Further studies are warranted to better understand the clinical relevance of these interactions with CYP4F2 in vivo.

Sex and developmental differences

Little information is available regarding sex or developmental differences impacting CYP4F2-dependent metabolism. A meta-analysis of 24 relevant studies showed no significant difference in doses of coumarin between male and female patients56. No studies were found examining the impact of developmental differences. Alade et al. 41 reported that females had modestly higher hepatic CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 mRNA levels than males. Patients aged ≤18 years showed 23% lower CYP4F2 mRNA levels than those aged 19-55 or 55 and older; for CYP4F11, values were 8.9% and 9.5% lower, respectively. However, there were no significant associations between sex and age when used as predictors for CYP4F2 or CYP4F11 mRNA expression levels.

CYP4F2 in PharmGKB and CPIC

PharmGKB collects, curates, and disseminates knowledge about the impact of human genetic variation on drug response57. The CYP4F2 gene page at PharmGKB58 allows structured access to curated gene-specific pharmacogenomic knowledge. Data are displayed in sections including prescribing information, drug label annotations, clinical annotations, variant annotations, curated pathways, and more. As of January 2024, the CYP4F2 gene page included one clinical guideline annotation for the CPIC guideline for CYP2C9, CYP4F2, VKORC1 and warfarin dosing3. Though there are no drug labels containing CYP4F2 to annotate, PharmGKB does provide the FDA Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations entry for CYP4F2 and warfarin59.

PharmGKB’s clinical annotations are evidence-rated, genotype-level summaries for specific variant/allele–drug combinations based on curated literature. Twelve clinical annotations are available, including one level 1A annotation for warfarin and one level 2A annotation for acenocoumarol dosage. PharmGKB pathways are evidence-based diagrams depicting the pharmacokinetics (PK) and/or pharmacodynamics (PD) of a drug with relevant (or potential) pharmacogenetic associations. CYP4F2 is included in the imatinib PK/PD pathway and the warfarin PD pathway.

PharmGKB and CPIC work collaboratively to develop gene-specific resources that accompany each CPIC guideline, including allele definition mapping, allele functionality, allele frequency, and diplotype to phenotype mapping files in a standardized format, which are created together with the guideline authors. The current CPIC warfarin guideline only includes CYP4F2*3 (c.1297G>A, p.V433M, rs2108622), and neither allele function nor phenotypes were assigned. Hence, only allele definition and frequency files are available60. The dosing recommendation flowchart (Figure 2 from the 2017 CPIC warfarin guideline update3) includes optional consideration for rs2108622 variant carriers (i.e., those with the c.1297G>A variant) with non-African ancestry3. At the time of the writing of this GeneFocus, CPIC guidelines have not been updated to include the new CYP4F2 haplotypes PharmVar has added to its catalog, including CYP4F2*4, which also has c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622).

Prior to the inclusion of CYP4F2*4 (c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622)) into PharmVar, frequencies for CYP4F2*2 (c.34T>G, p.W12G, rs3093105) and *3 (c.1297G>A, p.V433M, rs2108622) were captured based on the single variant defining each of these alleles. However, given that both variants are present in the newly defined CYP4F2*4 allele, CYP4F2*2, *3, and *4 allele frequencies are likely reported inaccurately. Analyzing allele frequencies using an integrated 200K UK Biobank genetic dataset61 and the Pharmacogenomics Clinical Annotation Tool (PharmCAT)62 with CYP4F2 allele definitions per September 2023 shows a substantial change compared to previous estimates for CYP4F2*1, *2, and *3 allele frequencies (see Frequency table60). The frequency of CYP4F2*1 is now lower due to the inclusion of CYP4F2*5-*15. For the unphased UK Biobank data, the PharmCAT calling algorithm could not distinguish between CYP4F2*1/*4 and *2/*3 diplotypes, assigning CYP4F2*1/*4 to subjects who are heterozygous for both c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622), due to a higher matching score. In an attempt to distinguish these alleles and differentiate between CYP4F2*1/*4 and *2/*3, two upstream variants, i.e., c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091) were included in the CYP4F2*3 and *5 allele definitions for reanalysis (at the time this analysis was performed, c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091) were only found on CYP4F2*3 and *5). The resulting diplotype calls revealed that only a small fraction (0.04%) of the prior CYP4F2*1/*4 calls were reassigned as CYP4F2*2/*3 with this approach, meaning that CYP4F2*3 is considerably less common compared to CYP4F2*4. The percentage changed slightly for different biogeographical groups (Europeans 0.04%, African American/Afro-Caribbeans 0.09%)60. Furthermore, data suggested that c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091) also occur without the CYP4F2*3 and *5 variants, as evidenced by *1.007 which was identified among the 1K-GP samples.

For core alleles defined by a unique variant, the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)63 can also be used to obtain frequency data. CYP4F2*5 (c.1555C>A, p.L519M, rs3093200) is prevalent in all populations represented in gnomAD v.4.1.0, with a frequency of 14.12% in Africans/African Americans. In non-Finnish Europeans, Admixed Americans, and Middle Eastern and South Asians, the allele has a frequency between 3.37 and 6.36%, while it is only present at <0.02% in East Asians. The frequency of CYP4F2*6 (c.554G>T, p.G185V, rs3093153) is 5.30% in non-Finnish Europeans, 3.20% in Admixed Americans, and 3.02% in Middle Eastern populations. In Africans/African Americans, it is present at a frequency of 3.23%, while it is observed at 0.74% and 0.02% in South and East Asians, respectively. CYP4F2*7-*15 are only found in some populations with frequencies below 1%, except CYP4F2*7 (c.46G>C, p.A16P, rs114099324), which has a frequency of 1.27% in African/African Americans, 0.16% in Admixed Americans, and 0.15% in Middle Eastern populations, and CYP4F2*14 (c.1021C>G, p.L341V, rs145174239) with a frequency of 1.85% in South Asians.

Allele frequencies are estimates and may change over time as new data become available, especially for populations which are underrepresented in databases such as the UK Biobank and gnomAD, and new star alleles are being defined. PharmGKB now also offers star allele frequencies for CYP4F2*1 through *7 from the All of Us Program. Although frequencies for CYP4F2 alleles are remarkably similar across these databases as illustrated for CYP4F2*7 (0.99% and 1.34 % for African American/Afro-Caribbean and Sub-Saharan African in the UK Biobank, 1.29% for AFR in All of Us, and 1.27% in African/Afrian American in gnomAD), these should only be cautiously extrapolated to admixed or geographically isolated populations.

The CYP4F2 gene locus

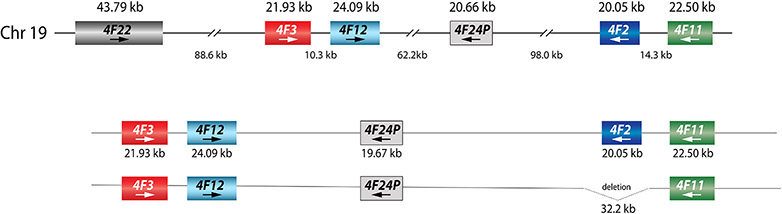

Located on chromosome 19, the CYP4F gene locus contains six genes, CYP4F22, CYP4F3, CYP4F12, the CYP4F24 pseudogene, CYP4F2 and CYP4F11 (Figure 2). CYP4F2 has 13 exons. Notably, the ATG translation start codon is in exon 2 (NG_007971.2 position 5464 counting from the sequence start), leaving the first exon untranslated.

Figure 2. Overview of the CYP4F gene locus.

As shown in the top panel, the gene locus spans approximately 426 kilobase pairs (kb). As indicated by the arrows, three of these genes are encoded on the negative strand, including CYP4F2. The length of each gene and respective intergenic regions are shown in kb. A large deletion comprising 32.2 kb affects the entire CYP4F2 gene (bottom panel); this structural variant/copy number variation (SV/CNV) containing allele is designated as CYP4F2*16.

Structural variation/copy number variation (SV/CNV), such as deletion and duplication events, affecting the CYP4F locus have been described in the literature and the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV)64. A 32.2 kb-long deletion encompassing the entire CYP4F2 gene was first described by Santos et al.65 (Figure 2); the deletion is cataloged by the DGV under accession number esv3643780. The deletion breakpoints were identified and experimentally validated using Coriell sample NA19010. A survey of whole genome sequencing (WGS) data from the 1K-GP10 revealed two other samples with this gene deletion. Notably, all three Coriell samples with this deletion are Japanese and direct genotyping revealed a frequency of 0.8% in this population48. PharmVar designated this SV/CNV affecting the entire gene as CYP4F2*16. This deletion was also found in six individuals (all East Asian) using WGS (Isabelle Lucas-Beckett unpublished data, personal communication). Another large deletion (DGV accession esv2671181) appears to affect the entire CYP4F2 gene and partial deletions of the adjacent CYP4F11 and CYP4F24P genes. Given that there was no further information available as of February 2024, this SV/CNV was not given an allele designation. CYP4F2 gene deletions have also been described in Koreans66; however, these were also not further characterized. Regarding duplications, several are annotated by the DGV database and have been reported in Koreans66. There is scarce information, though, regarding the size of duplications, which star allele(s) are duplicated or the exact number of gene copies. Additional information about SVs/CNVs can be found in the online Structural Variation document available at the PharmVar gene page67.

The PharmVar CYP4F2 gene page

All defined star alleles are listed on the CYP4F2 gene page67. Figure 3a provides an excerpt of the CYP4F2 gene page showing the CYP4F2*1, *2, *3 and *4 core alleles and selected suballeles. Information presented for each allele includes the variants defining the allele, haplotype evidence level, references supporting allele definitions, and cross-references to their legacy name if they were first published under a different name. PharmVar has recently updated the gene pages, which now display the rsID numbers of the variants along with variant positions and impact (e.g., amino acid change). Hyperlinks embedded in the rsIDs allow users to directly link-out to the dbSNP database. The CYP4F2 gene page67 also hosts the Read Me, Change Log, and Structural Variation documents which provide additional relevant gene-specific information, resources and examples. Each haplotype has a unique numerical identifier, the PharmVar ID (PVID). PVIDs and their respective haplotype definitions can be tracked in the database using the PVID Lookup function. Each allelic group also has a PVID that encompasses one or more haplotypes (suballeles).

Figure 3. Overview of CYP4F2 allele categorization in PharmVar.

An excerpt of the CYP4F2 gene page is provided in Panel (a) with NM_001082.5 as the reference sequence. The CYP4F2*1, *2, *3 and *4 core allele definitions are depicted by gray bars. All or selected suballeles are displayed underneath each core allele. Core variants, PharmVar ID (PVID), haplotype evidence levels, and citations are shown for each allele. Legacy allele names are cross-referenced. rsIDs are provided for each variant with direct link-out capability to dbSNP. Panel (b) is a graphical representation of selected alleles with their respective core variants highlighted in red. The blue boxes represent exons; the 5’ and 3’ UTRs are shown in light blue. Note that exon 1 is part of the 5’UTR and exon 13 is part of the 3’UTR. Since CPIC has not yet assigned clinical allele function for CYP4F2, function is shown as “CPIC Clinical Function N/A” (not available) for all star alleles. Two variants in the upstream region, c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091), are found in all CYP4F2*3 and CYP4F2*5 alleles, and may help facilitate discriminating CYP4F2*3 from CYP4F2*4; these variants are, however, also found on the CYP4F2*1.007 suballele which is depicted in Panel (a). Panel (c) represents the graphical output of PharmVar’s Comparative Allele ViewEr (CAVE) tool for all currently defined CYP4F2 star alleles except the CYP4F2*16 gene deletion. The PharmVar symbols indicate which variants are unique to an allele and the function symbol signifies that the variant alters function.

Variant mapping

PharmVar maps CYP4F2 variants to the genomic and transcript reference sequences NG_007971.2 and NM_001082.5. In addition, variants are also mapped to the GRCh37 and GRCh38 genome builds. These sequences match the CYP4F2*1 reference allele. Although some pharmacogenes, such as CYP2C19 and CYP2D6, have a Locus Reference Genomic (LRG) sequence, there is no LRG for CYP4F2 (LRGs are no longer issued by the NCBI). PharmVar offers two count modes, which provide variant positions from the sequence start (i.e., the first nucleotide in the reference sequence) or from the ATG translation start codon (with “A” from the ATG as +1). As mentioned above, in this GeneFocus, variant positions are provided using the transcript reference sequence NM_001082.5 (counting from ATG +1) unless specified otherwise.

Variant annotations according to the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS)68 are provided in the Variant Window along the more traditional PharmVar display format. This window is activated by clicking on a variant in the table view. More detailed information, along with examples, can be found in the Read Me document, available on the CYP4F2 gene page on the PharmVar website67.

Variants in the following regions are included in PharmVar star alleles definitions for CYP4F2: 5′ flanking sequence, the 5’UTR, all 13 exons, exon/intron junctions, and 250 base pairs (bp) of the 3’UTR. Specifically, star allele definitions contain variants within the 5’ limit (NG_007971.2 position 4751) and the 3’ limit (NG_007971.2 position 24554) spanning a total of 19.8 kb. Counting from the ATG translation start of NG_007971.2, these positions correspond to −713 (5’ limit) and 19091 (3’limit). All sequence variants within these limits, excluding intronic variants, must be submitted for star allele designation. Intronic variants may be submitted for allele definition if they are within splice recognition sequences, or if there is convincing evidence that the variant has a functional impact. As of the writing of this GeneFocus, no CYP4F2 star alleles contain intronic variants of functional relevance.

CYP4F2 haplotype evidence levels

PharmVar assigns Allele Evidence Levels for each star allele. As described on the “criteria” page in PharmVar69, definitive (Def), moderate (Mod), and limited (Lim) indicate the level of evidence supporting the existence of the haplotype or star allele (not their function). For CYP4F2, many of the defined alleles have an evidence level of Def, and there are currently no star alleles with a Lim evidence level. To lift evidence levels to Def, PharmVar solicits submissions for all alleles with a lower evidence level. Submissions for alleles with a Def evidence level but having only a single citation are also encouraged to further corroborate haplotype definitions.

Core allele definitions

A core allele is defined only by sequence variants that cause an amino acid change or impact function, e.g., changing expression levels or by interfering with splicing, and are present in all suballeles within an allele group. This rule-based system allows alleles with the same star number to be collapsed into a single “core” definition. For example, all alleles listed in the CYP4F2*2 group share c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and all CYP4F2*3 alleles share c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622); thus, c.34T>G and c.1297G>A are part of their respective core allele definitions (Figure 3). Currently, only CYP4F2*1, *2 and *3 have two or more suballeles listed within their respective groups. All suballeles within a group are presumed to be functionally equivalent. Therefore, even if a test can distinguish between suballeles within a particular star allele group, they can be reported using their core allele definitions. CYP4F2*4 (c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622)) is the only CYP4F2 core allele with two amino acid changes at the time of this writing; importantly, each can also occur by itself defining CYP4F2*2 and *3, respectively. CYP4F2 core allele definitions are utilized for annotations throughout PharmGKB.

The PharmVar Comparative Allele ViewEr (CAVE) and filter options

The Comparative Allele ViewEr (CAVE) tool allows users to compare core alleles graphically. Figure 3c visualizes the utility of this tool by comparing all CYP4F2 alleles defined to date, except for CYP4F2*16, which denotes an allele harboring a large deletion encompassing the entire gene. The CAVE tool makes it easy to see which core variants are unique to a star allele, and which ones are shared among star alleles (e.g., c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) are part of CYP4F2*2, *3 and *4). Alternatively, haplotypes can also be selectively displayed using the filter option available in the Variant Window (e.g., by selecting a variant position, or rsID), or using the “Show Haplotypes With This Variant” option.

Revisions and changes to previously published CYP4F2 star allele definitions

Prior to PharmVar’s curation efforts conducted in 2023, only CYP4F2*1, *2, and *3, which were transitioned from the cytochrome P450 nomenclature website, were available and displayed as originally defined. The genomic RefSeq NG_007971.2 matches the CYP4F2*1.001 suballele; this sequence also matches transcript reference sequences NM_001082.5 and GRCh38 (NC_000019.10), but not GRCh37 (NC_000019.9), which has the g.15989040G>C (rs1272) variant. Additional CYP4F2*1 suballeles, *1.002-*1.007, have been identified and named; none of their defining variants cause amino acid changes or are known to impact splicing or gene expression. The CYP4F2*2 and *3 alleles were originally defined by c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622), respectively9. Although the core definitions of these allele groups have not changed, their full characterization revealed that all haplotypes consolidated within each allelic group contain additional variants, e.g., CYP4F2*2.001 has c.-293C>A (rs3093092), c.165A>G (rs3093106) and c.246C>T (rs3093114) in addition to c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105), and CYP4F2*3.001 contains c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091) in addition to c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622). In other words, our data mining efforts using the high-coverage WGS data from the 1000 Genomes Project (1K-GP)10 did not reveal haplotypes that had only the core variants.

Reference materials and test recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–based Genetic Testing Reference Materials Coordination Program (GeT-RM) is tasked with the coordination of efforts to develop appropriate and characterized reference materials for quality control, proficiency testing, test development and validation, as well as research70. In 2016, GeT-RM reported genotype analyses performed on the DNA of 137 cell lines for 28 pharmacogenes, including CYP4F271. However, only limited testing was performed for CYP4F2. The now retired Affymetrix DMET array was used by one laboratory and included CYP4F2*2 (c.34T>G, p.W12G, rs3093105), CYP4F2*3 (c.1297G>A, p.V433M, rs2108622) and several select amino acid changes, namely p.W12C (c.36G>C, rs2906891), p.P13R (c.38C>G, rs2906890), p.G185V (c.554G>T, rs3093153) (now defining CYP4F2*6), and p.L278F (c.832C>T, rs4605294). Another laboratory tested solely for c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) to call CYP4F2*3. Among the samples tested, only CYP4F2*2 and *3 were identified, with CYP4F2*2 being reported as tentative as this allele was tested by only one laboratory. Considering the limitations regarding the extent of testing, the fact that c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622) is also part of the CYP4F2*4 haplotype, as well as the now expanded catalog of star alleles, there is a need for GeT-RM to not only reevaluate the previously published data but also to develop a set of reference materials covering the newly defined star alleles.

The Association of Molecular Pathology (AMP), in collaboration with other organizations, publishes recommendations for clinical genotyping allele selection, including recommendations for clinical warfarin genotyping allele selection72. The CYP4F2*3 allele (defined as having c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622)) was classified as a Tier 2 allele based on its association with decreased function and relatively high allele frequencies across populations. As noted earlier, routine testing may not be able to discriminate CYP4F2*1/*4 from *2/*3. Thus, adding c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091) to the genotyping strategy may help discriminate these diplotypes.

CYP4F2 allele characterization: methods, approaches, and pitfalls

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and therefore variant linkage are essential concepts to understand pharmacogene characterization. In this section, several examples of PharmVar submissions are reviewed to illustrate how haplotypes were determined using high-quality WGS data from the 1K-GP10. Additional information on this topic, including other approaches, can be found in previously published GeneFocus articles73-78.

Haplotypes can be easily and unambiguously inferred when all variants identified in an individual within the required regions are homozygous, or if only one variant is heterozygous. Figure 4a shows a sample (HG02501 is one example among many others) that is homozygous for five variants, including c.34T>G (p.W12G, rs3093105) and c.1297G>A (p.V433M, rs2108622), unequivocally demonstrating that these two variants occur in cis, i.e., on the same chromosome (or allele). This common haplotype was designated CYP4F2*4.001. Likewise, NA07348 (among other subjects) shown in Figure 4b is heterozygous for one variant only, c.554G>T (p.G185V, rs3093153), and therefore also allows for haplotype inference. This novel haplotype was designated CYP4F2*6.001.

Figure 4. Characterization of novel CYP4F2 allelic variants.

Panels (a-d) provide examples of alleles identified in high-quality WGS data from the 1000 Genomes Project (1K-GP). Nonsynonymous variants are highlighted in red with amino acids changes in bold red. Panels (a and b) exemplify samples with haplotypes that can unequivocally be determined as specified. Panel (c) illustrates how variant phasing can be inferred using inheritance in a family trio. Panel (d) details a trio in which c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) was confirmed in the mother by Sanger resequencing of a CYP4F2-specific PCR product. WGS data also produced a false-positive heterozygous call for this variant in the child (shown in blue and on the maternally inherited allele due to the mother having this variant). The absence of this variant was corroborated by the child’s diplotype, which shows they inherited the CYP2F4*2.001 allele (which does not have this variant) from the mother. Coriell sample IDs are as indicated.

However, if two or more variants are heterozygous, the variants may be in cis or in trans. Variant phasing can sometimes be achieved by short-read next-generation sequencing (NGS) data if the two variants are in close proximity, while they are in trans when observed independently across reads). For example, cis or trans configuration can be ascertained for samples that are heterozygous for c.-300C>A (rs3093090) and c.-299C>T (rs3093091), or c.165A>G (rs3093106) and c.246C>T (rs3093114), as they are close enough to be found on the same reads.

Trio or inheritance data were also utilized to establish the phase of CYP4F2 variants for star allele designation. Figure 4c depicts WGS data of a trio (Coriell family NG49) of which the father (HG03169) is heterozygous for two variants (c.46G>C (p.A16P, rs114099324) and c.165A>G (rs3093106)), the mother (HG03168) is heterozygous for three variants (c.165A>G (rs3093106), c.385G>A (p.E129L, rs145875499) and c.1739G>A (rs1126433)), and the child (HG03170) is heterozygous for three variants also (c.46G>C (p.A16P, rs114099324), c.385G>A (p.E129L, rs145875499) and c.1739G>A (rs1126433)). Trio information informed the individuals’ respective diplotypes as CYP4F2*1.005/*7.001 (father), *1.005/*12.001 (mother) and *7.001/*12.001 (child). This trio was used to define CYP4F2*12.001 and to confirm *7.001. The latter was informed by a homozygous individual, HG02721, which was also identified among the 1K-GP data set.

A separate trio (Coriell family 1463) analyzed with WGS revealed irregular inheritance patterns for c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346): the variant was called for the child (NA12878), but not for either parent. To investigate this issue, a CYP4F2 specific PCR fragment was generated from NA12878 (as well as several other samples with a positive c.1414A>G call) and Sanger sequenced (method as described in the CYP4F2 Read Me document67). Results indicated that WGS produced a false-positive call, possibly due to misalignments of reads originating from another CYP4F gene.

However, as demonstrated by trio Y061 and shown in Figure 4d, the c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) variant does, in fact, occur in CYP4F2. Here, the WGS call and phase from the mother (NA19122) were confirmed for both of her haplotypes (*2.001 and *17.001) using 10x Genomics LR data79 and Sanger resequencing of a CYP4F2 specific PCR amplicon, demonstrating that c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) is indeed present on the allele designated as CYP4F2*17.001. Notably, c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) was called by WGS for the child (NA12878). However, the trio data unequivocally showed that the child inherited the CYP4F2*2.001 from the mother which does not harbor c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) and CYP4F2*3.001 from the father, indicating that the WGS call represents a false-positive call.

There was one additional sample (HG03313) with a false-positive WGS call, in this instance, c.*58A>G (rs3952538) which is located in the 3’UTR. CYP4F2-specific Sanger resequencing identified the aforementioned variant as false-positive, while heterozygosity of c.1555C>A (p.L519M, rs3093200, CYP4F2*5) in exon 13 was confirmed. Taken together, these findings indicate that WGS variant calls for c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346), c.*58A>G (rs3952538) and other variants within this particular gene region require careful validation.

Mappability scores obtained from UCSC Mappability Tracks80 indicate regions with uniquely mappable reads of certain lengths (24 bp, 36 bp, 50 bp, and 100 bp). This tool indicates that CYP4F2 exons 5, 7 and 13 are potentially challenging regions which is consistent with our observations of false-positive calls residing in exon 13 and the 3’UTR. In addition to inconsistent inheritance data, WGS reference to alternative read ratios may help identify false-positive calls. For the exon 13 variant c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346), read ratios were skewed in confirmed false-positive cases. NA19123 (child), for example, had a ratio of reads with “A” and reads with “G” of 39:10, while those for the confirmed heterozygous sample (NA19122, mother) had a A:G ratio of 21:17. It is unknown, however, whether such skewed read ratios reliably identify false-positive calls. Reads ratios provided by gnomAD63 v4.0.0 are also noticeably skewed. Furthermore, variant frequencies for c.1414A>G (p.T472A, rs4020346) differ vastly among gnomAD v4.1.0, the 1K-GP and the Human Genome Diversity project (HGDP) within and across populations (e.g., 0.1719 vs 0.0011 vs 0.0000, respectively, for Europeans). In addition, gnomAD reports only four homozygotes, all East Asian, which is inconsistent with their reported variant frequencies (for Europeans 2.95% or about 2,792 indivuduals would be expected to by homozygous); 1K-GP and HGDP do not report any homozygotes.

When aligning a false-positive WGS short read of NA19123 (child of family Y061) or NA12878 (child of family 1463) with other CYP4F exon 13 sequences using the NCBI BLAST tool81, the closest match was CYP4F3. These particular misaligned reads had three mismatches with the CYP4F3 RefSeq NG_007964.2 and two with the CYP4F2 RefSeq NG_007971.2. Furthermore, CYP4F3 harbors three commonly observed SNVs within exon 13 (rs10404649, MAF=0.56; rs4343407, MAF=0.58; rs2460817, MAF=0.98), which conversely, all match the CYP4F2 reference nucleotides at these positions. Given that CYP4F2 and especially variant CYP4F3 short reads covering this region are highly similar, CYP4F3-derived misaligned reads are likely interfering with accurate read alignments and causing the false-positive variant calls.

Taken together, it appears that the CYP4F2 exon 13 region is prone to inconsistent NGS variant calls, and that frequency data provided by commonly utilized databases must be used with caution. There are no star alleles defined to date with variants in exons 5 or 7. However, these regions were not further scrutinized and thus, the possibility of false-negative calls in these gene regions cannot be excluded.

Bioinformatic tools

Increasing utilization of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) as the method of choice for clinically important pharmacogenes requires the availability of bioinformatic tools that accurately interpret the variant data. These tools, known as automatic star-allele callers, utilize BAM and/or VCF file formats to translate variant calls into star-allele diplotypes. While the performance of these tools has been assessed and/or compared for several genes82-85, there are no comparative studies on the performance of allele calling tools for CYP4F2 yet since the star allele nomenclature has only recently been updated. Of star-allele callers that support CYP4F2 interpretation, Aldy84, PharmCAT62, PyPGx86, and StellarPGx83 are highlighted here as they are actively maintained and updated. Of those, StellarPGx and PharmCAT call CYP4F2*2-*15 and *2-*15 and *17, respectively (alleles defined as of February 2024). It is therefore of utmost importance to understand which star alleles a tool is able to call (i.e., are contained in its catalogue) at the time it is being utilized. Since most of these tools are only periodically updated, it is good practice to check whether the tool being utilized is current with the PharmVar catalog of alleles. Furthermore, tools may be limited regarding the type of input data format. Aldy and PyPGx support data from short (exome and WGS) and long read NGS, while enhancements for StellarPGx are underway. Aldy and PyPGx also offer interpretation of array data, which fills a gap for star allele calling. PharmCAT accepts data from any source provided data are converted into VCF format but is currently unable to manage SV/CNVs. Each tool has strengths and weaknesses users should be aware of. There is no information regarding the impact of false-positive WGS calls on the accuracy of star allele calls made by these tools. Using a combination of tools to interpret HTS data may be one way to assess call accuracy and identify cases that require manual verification or interpretation.

Conclusions

This PharmVar GeneFocus provides information about the CYP4F2 pharmacogene. It highlights PharmVar efforts to assign and catalog CYP4F2 alleles, complementing information for clinical implementation provided by CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB. PharmVar works collaboratively with PharmGKB to standardize the information and make it useful and easily accessible to the entire pharmacogenetics community. CYP4F2 represents an enzyme with a niche role in oxidative metabolism of drugs and certain endogenous compounds. Appreciation of its relevance to VKA action due to effects on vitamin K metabolism has led to further studies showing its more direct relevance to metabolism of drugs such as imatinib and fingolimod. There are also well-established contributions to both eicosanoid and vitamin E metabolism. Recent systematic studies to define CYP4F2 variants across a range of ethnic groups and understand their functional relevance, including a possible role in disease susceptibility, makes inclusion of CYP4F2 in PharmVar an important advance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Wendy Wang , MLS(ASCP)CMMBCM for technical assistance with Sanger resequencing and the preparation of PharmVar submissions.

Funding

P.Z. is supported by Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Margarita Salas grant for the requalification of the Spanish university system.

J.D. is supported by grant 1R16GM149372-01 of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

PharmGKB and CPIC (T.E.K., M.W.C., and K.S.) gratefully acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health NHGRI/NICHD/NIDA U24 HG010615 and NHGRI U24 HG010135).

PharmGenetix GmbH acknowledges the Österreichische Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft GmbH (FFG) for support via the PGx-Next Generation Analytics Part 2 grant (FO0999891633/42175800).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests

J.S. is an employee of AccessDx Laboratories and C.N. is employed by PharmGenetix GmbH, a private laboratory providing PGx testing, reporting, and interpretation services. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

References

- 1.Kikuta Y. et al. Cloning and expression of a novel form of leukotriene B 4 ω-hydroxylase from human liver. FEBS Letters 348, 70–74 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information CYP4F2 cytochrome P450 family 4 subfamily F member 2 [ Homo sapiens (human) ]. Gene ID: 8529. NIH Gene website; (2023) at <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/8529> [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson J. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Pharmacogenetics-Guided Warfarin Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 102, 397–404 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shekhar S. et al. Conflicting Roles of 20-HETE in Hypertension and Stroke. IJMS 20, 4500 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang T, Yu K & Li X Cytochrome P450 family 4 subfamily F member 2 (CYP4F2) rs1558139, rs2108622 polymorphisms and susceptibility to several cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18, 29 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng H, Li B, Wang Y & Wang L Association Between the CYP4F2 Gene rs1558139 and rs2108622 Polymorphisms and Hypertension: A Meta-Analysis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 23, 342–347 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaedigk et al. , Pharmacogene Variation Consortium: A Global Resource and Repository for Pharmacogene Variation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021. Sep;110(3):542–545. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2321. Epub 2021 Jun 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaedigk A. et al. The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: Incorporation of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103, 399–401 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stec DE, Roman RJ, Flasch A & Rieder MJ Functional polymorphism in human CYP4F2 decreases 20-HETE production. Physiol Genomics 30, 74–81 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrska-Bishop M. et al. High-coverage whole-genome sequencing of the expanded 1000 Genomes Project cohort including 602 trios. Cell 185, 3426–3440.e19 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B. et al. Frequencies of pharmacogenomic alleles across biogepgraphical groups in a large-scale biobank. Am J Hum Genet 110, 1628–1647 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PharmVar Genes. PharmVar at <https://www.pharmvar.org/genes>

- 13.Hao Z, Jin D-Y, Stafford DW & Tie J-K Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of coagulation factors: insights from a cell-based functional study. Haematologica 105, 2164–2173 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarellos ML et al. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for CYP4F2. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 25, 41–47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Heuzey J-Y et al. Differences among western European countries in anticoagulation management of atrial fibrillation. Data from the PREFER IN AF registry. Thromb Haemost 111, 833–841 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wypasek E, Branicka A, Awsiuk M, Sadowski J & Undas A Genetic determinants of acenocoumarol and warfarin maintenance dose requirements in Slavic population: a potential role of CYP4F2 and GGCX polymorphisms. Thromb Res 134, 604–609 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smires FZ et al. Influence of genetics and non-genetic factors on acenocoumarol maintenance dose requirement in Moroccan patients. J Clin Pharm Ther 37, 594–598 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna Kumar D. et al. An acenocoumarol dosing algorithm exploiting clinical and genetic factors in South Indian (Dravidian) population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71, 173–181 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerezo-Manchado JJ et al. Effect of VKORC1, CYP2C9 and CYP4F2 genetic variants in early outcomes during acenocoumarol treatment. Pharmacogenomics 15, 987–996 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borobia AM et al. An acenocoumarol dosing algorithm using clinical and pharmacogenetic data in Spanish patients with thromboembolic disease. PLoS One 7, e41360 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajmi M. et al. Influence of genetic and non-genetic factors on acenocoumarol maintenance dose requirement in a Tunisian population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 74, 711–722 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danese E. et al. Impact of the CYP4F2 p.V433M polymorphism on coumarin dose requirement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 92, 746–756 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Schie RMF, Aoussar A, van der Meer FJM, de Boer A & Maitland-van der Zee AH Evaluation of the effects of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in CYP3A4 and CYP4F2 on stable phenprocoumon and acenocoumarol maintenance doses. J Thromb Haemost 11, 1200–1203 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teichert M. et al. Dependency of phenprocoumon dosage on polymorphisms in the VKORC1, CYP2C9, and CYP4F2 genes. Pharmacogenet Genomics 21, 26–34 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fava C. et al. The V433M Variant of the CYP4F2 Is Associated With Ischemic Stroke in Male Swedes Beyond Its Effect on Blood Pressure. Hypertension 52, 373–380 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fava C, Ricci M, Melander O & Minuz P Hypertension, cardiovascular risk and polymorphisms in genes controlling the cytochrome P450 pathway of arachidonic acid: A sex-specific relation? Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators 98, 75–85 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rochat B. et al. In vitro biotransformation of imatinib by the tumor expressed CYP1A1 and CYP1B1. Biopharm Drug Dispos 29, 103–118 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin Y, Zollinger M, Borell H, Zimmerlin A & Patten CJ CYP4F enzymes are responsible for the elimination of fingolimod (FTY720), a novel treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Drug Metab Dispos 39, 191–198 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovarik JM et al. Ketoconazole increases fingolimod blood levels in a drug interaction via CYP4F2 inhibition. J Clin Pharmacol 49, 212–218 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obach RS Linezolid Metabolism Is Catalyzed by Cytochrome P450 2J2, 4F2, and 1B1. Drug Metab Dispos 50, 413–421 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perumpail BJ et al. The Role of Vitamin E in the Treatment of NAFLD. Diseases 6, 86 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Office of Dietary Supplements National Institutes of Health (NIH) Vitamin E. Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. (2021) at <https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminE-HealthProfessional/#en17>

- 33.Schmölz L, Birringer M, Lorkowski S & Wallert M Complexity of vitamin E metabolism. World J Biol Chem 7, 14–43 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardowell SA, Stec DE & Parker RS Common variants of cytochrome P450 4F2 exhibit altered vitamin E-{omega}-hydroxylase specific activity. J Nutr 140, 1901–1906 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sontag TJ & Parker RS Cytochrome P450 omega-hydroxylase pathway of tocopherol catabolism. Novel mechanism of regulation of vitamin E status. J Biol Chem 277, 25290–25296 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Athinarayanan S. et al. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 4F2, vitamin E level and histological response in adults and children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who participated in PIVENS and TONIC clinical trials. PLoS One 9, e95366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J. et al. Change in plasma α-tocopherol associations with attenuated pulmonary function decline and with CYP4F2 missense variation. Am J Clin Nutr 115, 1205–1216 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang L & Zheng Q Insights into the binding mechanism between α-TOH and CYP4F2: A homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation study. J Cell Biochem 124, 573–585 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Major JM et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants associated with circulating vitamin E levels. Hum Mol Genet 20, 3876–3883 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farley SM et al. ω-Hydroxylation of phylloquinone by CYP4F2 is not increased by α-tocopherol. Mol Nutr Food Res 57, 1785–1793 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alade AN et al. Cytochrome P450 Family 4F2 and 4F11 Haplotype Mapping and Association with Hepatic Gene Expression and Vitamin K Hydroxylation Activity. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci acsptsci.3c00287 (2024).doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.3c00287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirani V, Yarovoy A, Kozeska A, Magnusson RP & Lasker JM Expression of CYP4F2 in human liver and kidney: assessment using targeted peptide antibodies. Arch Biochem Biophys 478, 59–68 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grangeon A. et al. Determination of CYP450 Expression Levels in the Human Small Intestine by Mass Spectrometry-Based Targeted Proteomics. Int J Mol Sci 22, 12791 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Majdoub ZM et al. Quantitative Proteomic Map of Enzymes and Transporters in the Human Kidney: Stepping Closer to Mechanistic Kidney Models to Define Local Kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110, 1389–1400 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michaels S & Wang MZ The revised human liver cytochrome P450 ‘Pie’: absolute protein quantification of CYP4F and CYP3A enzymes using targeted quantitative proteomics. Drug Metab Dispos 42, 1241–1251 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirani V, Yarovoy A, Kozeska A, Magnusson RP & Lasker JM Expression of CYP4F2 in human liver and kidney: assessment using targeted peptide antibodies. Arch Biochem Biophys 478, 59–68 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uhlen M. et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat Biotechnol 28, 1248–1250 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carithers LJ & Moore HM The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreserv Biobank 13, 307–308 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato Y. et al. Functional Characterization of 29 Cytochrome P450 4F2 Variants Identified in a Population of 8380 Japanese Subjects and Assessment of Arachidonic Acid ω-Hydroxylation. Drug Metab Dispos 51, 1561–1568 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim W-Y et al. Identification of novel CYP4F2 genetic variants exhibiting decreased catalytic activity in the conversion of arachidonic acid to 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 131, 6–13 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu M-H, Savas U, Griffin KJ & Johnson EF Regulation of human cytochrome P450 4F2 expression by sterol regulatory element-binding protein and lovastatin. J Biol Chem 282, 5225–5236 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X & Hardwick JP Regulation of CYP4F2 leukotriene B4 omega-hydroxylase by retinoic acids in HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 279, 864–871 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Chen L & Hardwick JP Promoter activity and regulation of the CYP4F2 leukotriene B(4) omega-hydroxylase gene by peroxisomal proliferators and retinoic acid in HepG2 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 378, 364–376 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park J-W, Kim K-A & Park J-Y Effects of Ketoconazole, a CYP4F2 Inhibitor, and CYP4F2*3 Genetic Polymorphism on Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin K1. J Clin Pharmacol 59, 1453–1461 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe H, Yamaori S, Kamijo S, Aikawa K & Ohmori S In Vitro Inhibitory Effects of Sesamin on CYP4F2 Activity. Biol Pharm Bull 43, 688–692 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Danese E. et al. Impact of the CYP4F2 p.V433M polymorphism on coumarin dose requirement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 92, 746–756 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whirl-Carrillo M. et al. An Evidence-Based Framework for Evaluating Pharmacogenomics Knowledge for Personalized Medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110, 563–572 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.PharmGKB CYP4F2 at <https://www.pharmgkb.org/gene/PA27121>

- 59.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations. (2022) at <https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/precision-medicine/table-pharmacogenetic-associations>

- 60.PharmGKB Gene-specific Information Tables for CYP4F2 at <https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp4f2RefMaterials>

- 61.Li B. et al. Frequencies of pharmacogenomic alleles across biogeographic groups in a large-scale biobank. Am J Hum Genet 110, 1628–1647 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sangkuhl K. et al. Pharmacogenomics Clinical Annotation Tool (PharmCAT). Clin Pharmacol Ther 107, 203–210 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karczewski KJ et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) at <http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home>

- 65.Santos M. et al. Novel copy-number variations in pharmacogenes contribute to interindividual differences in drug pharmacokinetics. Genetics in Medicine 20, 622–629 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han N, Oh JM & Kim I-W Combination of Genome-Wide Polymorphisms and Copy Number Variations of Pharmacogenes in Koreans. J Pers Med 11, 33 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.PharmVar CYP4F2 at <https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP4F2>

- 68.den Dunnen JT et al. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum Mutat 37, 564–569 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.PharmVar Allele Designation Criteria and Evidence Levels at <https://www.pharmvar.org/criteria>

- 70.Scott SA The Genetic Testing Reference Materials Coordination Program: Over 10 Years of Support for Pharmacogenomic Testing. J Mol Diagn 25, 630–633 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pratt VM et al. Characterization of 137 Genomic DNA Reference Materials for 28 Pharmacogenetic Genes: A GeT-RM Collaborative Project. J Mol Diagn 18, 109–123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pratt VM et al. Recommendations for Clinical Warfarin Genotyping Allele Selection: A Report of the Association for Molecular Pathology and the College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn 22, 847–859 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sangkuhl K. et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C9. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110, 662–676 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez-Antona C. et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP3A5. Clin Pharmacol Ther 112, 1159–1171 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramsey LB et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: SLCO1B1. Clin Pharmacol Ther 113, 782–793 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nofziger C. et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2D6. Clin Pharmacol Ther 107, 154–170 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Desta Z. et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2B6. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110, 82–97 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Botton MR et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C19. Clin Pharmacol Ther 109, 352–366 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.GitHub & Bekritsky, M. HiSeqX PGx Cohort (2018) at <https://github.com/Illumina/Polaris/wiki/HiSeqX-PGx-Cohort>

- 80.Karimzadeh M, Ernst C, Kundaje A & Hoffman MM Umap and Bismap: quantifying genome and methylome mappability. Nucleic Acids Research (2018).doi: 10.1093/nar/gky677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) at <https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi>

- 82.Twesigomwe D. et al. A systematic comparison of pharmacogene star allele calling bioinformatics algorithms: a focus on CYP2D6 genotyping. NPJ Genom Med 5, 30 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Twesigomwe D. et al. StellarPGx: A Nextflow Pipeline for Calling Star Alleles in Cytochrome P450 Genes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110, 741–749 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hari A. et al. An efficient genotyper and star-allele caller for pharmacogenomics. Genome Res 33, 61–70 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gaedigk A. et al. CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 Characterization Using Next-Generation Sequencing and Haplotype Analysis: A GeT-RM Collaborative Project. J Mol Diagn 24, 337–350 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee S-B, Shin J-Y, Kwon N-J, Kim C & Seo J-S ClinPharmSeq: A targeted sequencing panel for clinical pharmacogenetics implementation. PLoS One 17, e0272129 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.PharmGKB Warfarin Pathway, Pharmacodynamics at <https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA145011114>