Abstract

Exogenous gaseous formaldehyde (FA) is recognized as a significant indoor air pollutant due to its chemical reactivity and documented mutagenic and carcinogenic properties, particularly in its capacity to damage DNA and impact human health. Despite increasing attention on the adverse effects of exogenous FA on human health, the potential detrimental effects of endogenous FA in the brain have been largely neglected in current research. Endogenous FA have been observed to accumulate in the aging brain due to dysregulation in the expression and activity of enzymes involved in FA metabolism. Surprisingly, excessive FA have been implicated in the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and brain cancers. Notably, FA has the ability to not only initiate DNA double strand breaks but also induce the formation of crosslinks of DNA-DNA, DNA-RNA, and DNA–protein, which further exacerbate the progression of these brain diseases. However, recent research has identified that FA-resistant gene exonuclease-1 (EXO1) and FA scavengers can potentially mitigate FA toxicity, offering a promising strategy for mitigating or repairing FA-induced DNA damage. The present review offers novel insights into the impact of FA metabolism on brain ageing and the contribution of FA-damaged DNA to the progression of neurological disorders.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Aging brain, Endogenous formaldehyde, DNA damage, Brain diseases, Exonuclease 1 (EXO1), FA scavengers

Introduction

Endogenous FA accumulation in the ageing brain

With age, all organs of the human body, including the brain, undergo a series of physiological and pathological changes, which are manifested in the decline of language ability, visuospatial ability, cognitive ability, and the decline of concentration and memory (Mattson and Arumugam 2018). At the cellular and molecular level, brain aging is characterized by the following features: increased inflammatory response, impaired mitochondrial function, oxidative folding of proteins, endogenous formaldehyde (FA) accumulation, and DNA damage (Cheng et al. 2023; Tong et al. 2011a). Gaseous FA is a common small molecule substance with strong metabolism and active chemical properties, and has been known for its strong mutagenicity and carcinogenicity for over a century (Farooqui 1983). Endogenous FA accumulation in the aging brain can be confirmed by measuring FA concentrations in humans by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. More than 40 years ago, researchers used this method to obtain FA concentrations of 0.08 mmol/L in human blood and 0.2–0.4 mmol/L in brain tissue (Heck et al. 1982). The above FA levels are at normal levels and can be metabolized by the body normally. However, the concentration of FA in the body of healthy people tended to increase with increasing age and induce decline in memory as well as cognitive disorders. The neuromolecular mechanism of FA-induced memory loss has been elucidated, that is, it can spontaneously react with the α/ε amino groups of proteins, leading to protein aggregation and loss of activity; while it can react with the cysteine sulfhydryl group on the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor, affecting the function of the NMDA receptor (Tong et al. 2011a). Moreover, the mechanism of FA-induced cognitive impairment is closely related to norepinephrine depletion. Hippocampal norepinephrine plays a very important role in learning and memory, which can enhance hippocampal long-term potentiation and memory formation (Gelinas and Nguyen 2007). It was found that FA in vitro and intrahippocampal injections can significantly reduce norepinephrine levels, which becomes a key factor in cognitive ability and memory decline (Mei et al. 2015).

FA induces genotoxicity

FA is characterized by its distinctive molecular structure and physicochemical properties, such as a limited steric hindrance, reactive carbonyl electrophilicity, cellular permeability, and temperature-dependent stability of methylene bridge adducts (Hoffman et al. 2015). Its elevated genotoxicity primarily manifests in the cells of organisms through DNA damage. The diverse forms of DNA damage caused by FA have been identified in current research, including various types of DNA breaks, DNA-DNA cross-linking, DNA-RNA cross-linking, DNA protein cross-linking (DPC), and DNA adducts. The specific mechanisms of this damage can be categorized into two aspects: direct damage to DNA through a series of chain chemical reactions, and indirect damage to DNA through impairment of the damage recognition and excision repair system (Ortega-Atienza et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2017). Recent studies have shown that endogenous FA, rather than exogenous sources, is the main cause of FA genotoxicity, challenging previous beliefs about the dangers of inhaling FA (Lu et al. 2010a). It can contribute to disease development by causing DNA damage and impairing repair processes through various pathways.

DNA damage is involved in the brain diseases

Numerous studies have linked cellular DNA damage buildup and decreased repair ability to various diseases, often resulting in impaired cell repair and proliferation in regenerative cells (Fang et al. 2016; Lautrup et al. 2019; Shiloh and Lederman 2017). In contrast, the narrow sense of nerve cells, i.e., neurons, as a kind of non-renewable cells, their DNA damage often manifests degenerative lesions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases (Misiak et al. 2017; Sykora et al. 2015). Moreover, due to the presence of a large number of glial cells in the brain, their DNA damage can manifest as primary tumors of the central nervous system, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, in which approximately 2%-10% of patients develop brain tumors in childhood (Orr et al. 2020), and the complex interaction of different DNA damages in glioblastoma results in redundant repair mechanisms, potentially causing tumor resistance to drugs (Rominiyi and Collis 2022). Various evidence indicates that DNA damage is closely associated with brain diseases, including cancer. The traditional Aβ hypothesis is still prevalent in understanding neurodegenerative diseases like AD, but the connection between these diseases and DNA damage requires further exploration.

This paper reviews how endogenous FA production in the aging brain leads to DNA damage and contributes to the development of brain diseases. It offers a novel perspective on the development of AD and FA-related diseases, along with new diagnostic markers and treatment options.

Endogenous FA accumulation in the ageing brain

Disorders of FA metabolizing enzyme systems during ageing

The brain can produce FA through a variety of pathways, the most prominent of which are enzymatic reactions, for example, semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO) (Obata 2006), cytochrome P450 (CYP450) (Hasemann et al. 1995), lipid oxidases, demethylase, endoplasmic reticulum demethylase (Kalász 2003; Yu et al. 2003) and other demethylase (Trewick et al. 2002). Of course, FA can be degraded to maintain homeostasis of FA levels in brain tissues by some enzymes, such as: glutathione-dependent FA dehydrogenase (FDH or named ADH3) and alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) (Martínez et al. 2001), and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) (Fei and Tong 2020). It has been found that abnormalities in the content and activity of these enzymes, particularly ALDH2 and dehydrogenase 5 (ADH5), can lead to FA accumulation and memory impairment. This was demonstrated in ADH5 and ALDH2 knockout mice. Among them, FA was degraded more significantly by ALDH2 compared to ADH5 when FA levels are too high (Kou et al. 2022). During the aging process, there is a decline in the function of FA metabolism enzyme system in the brains. For instance, brain FA levels were higher in 3-month-old senescence accelerated mouse-prone 8 strain compared to controls. Enzyme levels were examined and found to be elevated in SSAO expression levels, while enzyme activity of ADH3 were reduced (Qiang et al. 2014). This results in a situation where the rate of FA generation exceeds the rate at which the brain is able to degrade FA, leading to the accumulation of FA in brain tissue and brain diseases (Kou et al. 2022) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multiple metabolic pathways of endogenous FA. Red arrows: FA-generating pathways; blue arrows: FA-degrading pathways (Fei and Tong 2020). Abbreviations: ADH1, alcohol dehydrogenase 1; ADH3, alcohol dehydrogenase 3; ALDH2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; CAT, catalase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FA, formaldehyde; LSD1, lysine special demethylase 1; MeOH, methanol; MIT, mitochondria; MMA, monomethylamine; SA, sarcosine; SARDH, sarcosine dehydrogenase; SSAO, semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase; TET1, TET methylcytosine dioxygenase 1. Adapted with the permission of ref. (Fei and Tong 2020), copyright@Acta Physiologica Sinica, 2020

FA causes DNA damage

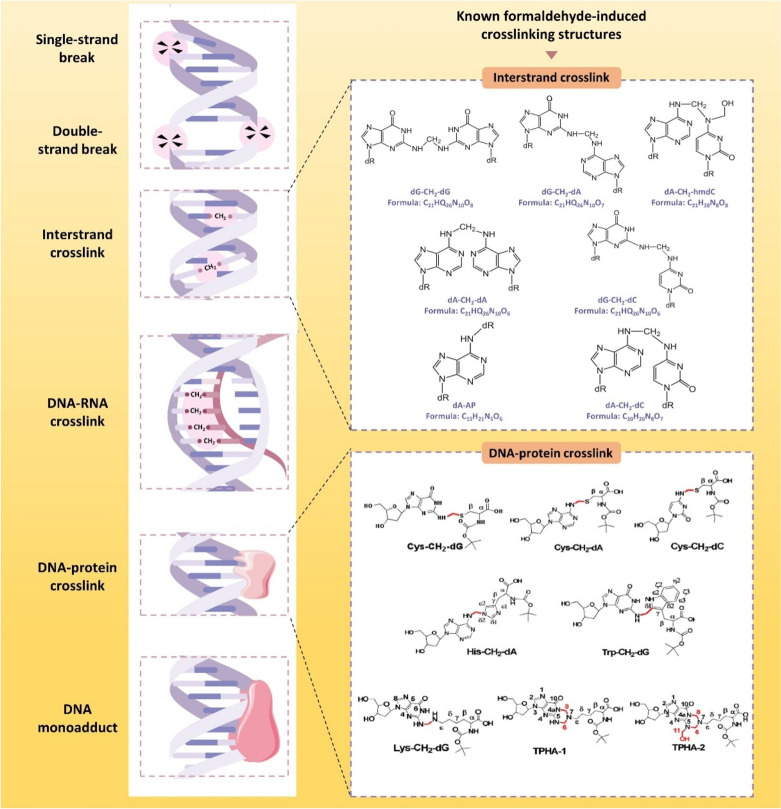

Types of DNA damage caused by FA

FA-induced mutagenesis FA is well known as a very common mutagen, which is particularly effective for deletion mutagenesis (Anderson 1995). As we have mentioned above, ALDH2 and ADH5 are the most important FA-degrading enzymes. Significant FA accumulation was present in the serum of Aldh2-/-Adh5-/- mice obtained by hybridization. At the same time, an increase in FA-modified DNA in tissues and mutational signatures was found including single-nucleotide substitutions, double-base substitutions, insertions and deletions, which is similar to patterns observed in human cancers (Dingler et al. 2020). It seems clear that FA in peripheral tissues can lead to genetic mutations and thus cause diseases. However, in contrast, few studies have addressed the relationship between FA-induced mutations and brain diseases.

FA-induced DNA breakage DNA breakage occurs when one or both strands of the DNA molecule are broken, either as single-strand breaks (SSBs) or double-strand breaks (DSBs). Different cell types show varying levels of sensitivity to FA's toxic effects (Jimenez-Villarreal et al. 2017). FA-induced DNA breaks have also been confirmed at the cellular experimental levels (Bedford and Fox 1981). FA caused DNA damage at specific concentrations (5, 7.5, 10, 15 μM) that could be quickly repaired. This indicates that FA may cause single-strand breaks at lower concentrations and DNA-DNA cross-links at higher concentrations, but the exact biological mechanism is unclear (Liu et al. 2006). In addition, FA also causes mitochondrial DNA double-strand breaks (Miwa and Brand 2003) via reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Nadalutti et al. 2020).

FA-caused DNA-DNA cross-linking There are two types of DNA-DNA cross-linking: intrastrand and interstrand. Intrastrand occurs within the same DNA strand, while interstrand occurs between two DNA strands. Helicases unwind the DNA double helix for replication and transcription, but interstrand crosslinking hinders these processes. Therefore, interstrand cross-linking is one of the most consequential DNA damages. At the same time, it is the only form of formaldehyde-induced DNA-DNA cross-linking in the available studies. FA preferentially forms dA—dA cross-links at dinucleotide sequence 5'-d(AT) in certain AT-rich double-stranded DNA sequences but the mechanism is not clear (Huang et al. 1992). Exposure of human peripheral blood lymphocytes to different concentrations of FA induced DNA-DNA cross-linking when FA concentration was greater than 25 μM (Liu et al. 2006).

FA-induced DNA-RNA cross-linking DNA-RNA cross-links were found in NNK-treated mouse lung DNA in 2022. The authors propose that these cross-links may be DNA-RNA hybrids formed during transcription, replication, or gene expression, and that FA reacts with the base portions of DNA and RNA to induce these cross-links on the R-loop (Dator et al. 2022). In addition, mechanisms of FA-induced DNA-RNA cross-linking are unclear, which need to be further investigated.

FA-caused DPCs The DPCs, complexes formed when DNA and protein interact through a series of non-covalent forces, are considered to be the most consequential type of DNA damage and are widely found in FA-induced DNA damage (Weickert and Stingele 2022). FA, a common cross-linking agent, can cause various damages by inducing excessive DPCs and interfering with normal cellular physiological activities such as DNA replication and transcription. However, FA induces the production of DPCs only at higher concentrations, because the induced DPCs could be slowly repaired within the cell and would not accumulate for a long period of time (Liu et al. 2006).

FA-induced DNA adducts The DNA adducts are a piece of DNA covalently bound to some chemical substances (Parthiban et al. 2015). In order to distinguish between DNA adducts induced by endogenous and inhaled FA exposure, rats were exposed to 10 ppm [13CD2] FA for 1 or 5 days (6 h/day) using a nose-only chamber. The N2 -HO13CD2-dG produced by exogenous [13CD2]-FA exposure is formed only in DNA at the nasal inlet; endogenous N6 -hydroxymethyl-dA is present in all tissues (Lu et al. 2010a). Tissue samples from rats exposed to 1,30 and 300 ppb FA were analyzed by the same method as above. Endogenous adducts were detected, while exogenous adducts were not found in any groups (Leng et al. 2019). FA can activate certain drugs to bind covalently to DNA, in addition to directly binding and forming DNA adducts. In the process of forming certain drug-DNA adducts, FA plays a crucial role, particularly in the case of anthracyclines and anthracenediones. Mitoxantrone, an anticancer anthracenedione, was identified as the initial anthracenedione capable of generating substantial DNA crosslinks facilitated by FA (Pumuye et al. 2020) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Types of DNA damage induced by FA. The types of damage induced by FA include DNA break, interstrand crosslink, DNA-RNA crosslink, DPCs, and DNA monoadducts. Among the several types of DNA damage induced by FA, relevant studies have clarified the specific chemical structures of DNA interstrand crosslink, reproduced with the permission of ref. (Hu et al. 2019), copyright@American Chemical Society, 2019 and DNA–protein crosslink, reproduced with the permission of ref. (Lu et al. 2010b), copyright@American Chemical Society, 2010, including 7 types of ICLs and 8 types of DPCs respectively

FA-induced RNA–protein crosslinking In addition to the above widely studied types of FA-induced DNA damage, a 2023 study demonstrated for the first time FA-induced RPCs, which stall ribosomes and thus inhibit the translation process (Suryo Rahmanto et al. 2023). The newly established modeling system photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking can help to confirm this process (Zhao et al. 2023). Such RPCs significantly activate K6-linked ubiquitination while marginally increasing K33-linked ubiquitination, ultimately resolved by the ubiquitin-dependent remodeler valosin-containing protein (Suryo Rahmanto et al. 2023). More issues remain to be investigated, such as the levels of RPCs in physiologic and certain disease states and whether they cause cytotoxicity other than the translational process.

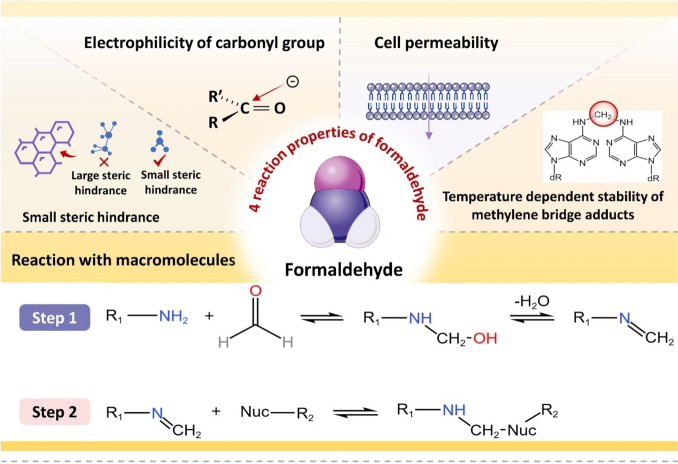

Mechanisms of DNA damage caused by FA

Molecular structures of the complex of FA/nucleic acids

FA is an active alkylating agent with its own unique molecular structure and physicochemical properties: 1) simple and small-sized molecular structure leading to a small spatial site resistance; 2) active carbonyl group electrophilicity; 3) cell permeability; 4) temperature-dependent stabilization of methylene-bridge-containing adducts etc. (Hoffman et al. 2015). These properties make FA easy to cross-link with various macromolecules and form a variety of adducts (Fraenkel-conrat et al. 1945). It is commonly used as a cross-linking agent in various biological assays due to its strong cross-linking properties (Hoffman et al. 2015; Kim and Dekker 2018; Klockenbusch et al. 2012; Sutherland et al. 2008), and the more commonly used techniques are chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and chromosome conformation capture (3C) analysis (Kim and Dekker 2018). In living cells, high levels of macromolecules and FA can cause significant DNA damage. Research has been done to understand how FA interact with DNA and other molecules in a controlled setting. (Feldman 1973; McGhee and von Hippel 1975a; McGhee and von Hippel 1975b; Metz et al. 2004), which are summarized in a review (Hoffman et al. 2015). This difference poses challenges in detection, yet it is essential to acknowledge that FA's distinctive molecular structure and physicochemical properties confer a significant advantage in inducing DNA damage (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Reaction properties of FA and the basic process of reaction with biological macromolecules. FA is an active alkylating agent with its own unique molecular structure and physical and chemical properties, which is shown in the upper part of the figure. Existing studies have clarified the specific steps of the reaction between FA and biological macromolecules such as DNA and proteins through in vitro experiments, which are shown in the lower part of this figure, adapted with the permission of ref. (Hoffman et al. 2015), copyright@Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2015

FA induces oxidative stress

FA-damaged antioxidant system Living organisms have both oxidative and antioxidant systems, with enzymes and non-enzymatic substances playing a role in these reactions. Among them, the oxidative system includes superoxide radicals (-O2-), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (-OH) in ROS, xanthine oxidase (XO), and the lipid peroxidation end-products malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4- HNE), etc.; in the antioxidant system, glutathione (GSH) is the most important antioxidant in the body, in addition to the three classical enzymatic antioxidants: superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and catalase (CAT) (Sies 1997). In addition to the above substances there are glutathione reductase (GR) and glutathione s-transferase (GST) involved in the system. Under physiological conditions, the oxidative and antioxidant systems are in a balanced homeostasis. However, FA exposure leads to dysregulation of the oxidative and antioxidant systems associated with a decrease in the levels of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, XO, GSH and MDA, while an increase in the level of ROS in the cerebellar cortex (Zararsiz et al. 2011).

FA-impaired mitochondria The mitochondria are the main site of ATP generation by aerobic respiration in most eukaryotic cells and are closely associated with various redox reactions (Zorova et al. 2018). In living cells, mitochondria are the main source of ROS, a central substance of oxidative stress (Miwa and Brand 2003). However, FA can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction through a variety of pathways. For example, FA can reduce in mitochondrial membrane potential levels and an increase in Cyt-c transfer from mitochondria to the cytoplasm (Tang et al. 2012), and inhibit the respiratory chain by inactivating the phosphate transport system in the mitochondrial membrane, blocking ATP production in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Tyler 1969).

FA-induced oxidative stress associated with brain diseases FA-induced oxidative stress is associated with brain diseases. Although there is no definitive conclusion on the involvement of FA-induced oxidative stress as a dominant factor in brain diseases, it is certain that oxidative stress plays an important role. Using multiple bioinformatics analyses, provided important guidance on candidate genes and possible pathways of FA leading to brain cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (NDD). Through toxicogenomic databases, it was found that among the FA exposure-related genes, the antioxidant enzyme SOD2 gene overlapped the most with genes related to common brain diseases, which included brain cancer, AD, PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other NDD while the antioxidant enzyme SOD1 ranked the third, which included PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other NDD. Indeed, 20% of the genes in oxidative stress are affected by FA exposure. In addition, among the significantly enriched pathways for FA and NDD subgroups or brain tumor-related genes, the oxidative stress pathway was highly enriched (Rana et al. 2021).

FA inhibits DNA damage recognition and excision repair in cells

FA not only directly damages DNA through various pathways, but also impairs the DNA damage recognition and excision repair system, thus preventing the repair of damaged DNA and causing irreversible DNA damage. For example, a large number of proteasome-targeted k48-linked polyubiquitin proteins were detected in the nuclei and cytoplasm of human lung epithelial cells treated with FA exposure for a short period of time and triggered a strong heat shock response, suggesting that a large number of damaged proteins accumulated rapidly in the cells (Ortega-Atienza et al. 2016). In addition, FA-induced DPCs are mainly repaired by hydrolysis through proteasomal scavenging (Ortega-Atienza et al. 2015; Quievryn and Zhitkovich 2000). The formation and accumulation of a large number of damaged proteins in the cell caused by FA reduces the ability of the ubiquitin–proteasome system to remove DNA cross-linking proteins, thus hindering the repair of DPCs (Ortega-Atienza et al. 2016). Especially, breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2) is a tumor suppressor with DNA repair ability, which is one of the important components in the DNA damage recognition and excision repair system, and BRCA2 mutation is closely related to the occurrence of many types of cancers, especially breast cancer (Xie et al. 2022). It has been shown that FA depletes BRCA2 protein in a dose-dependent manner, which causes DNA replication stress and results in DNA damage that is difficult to be repaired (Tan et al. 2017). In conclusion, this novel mechanism helps us to understand the relationship between FA and DNA damage from a more comprehensive and deeper perspective (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms of DNA damage induced by FA. FA mainly causes DNA damage through three ways, including direct cross-linking of large molecules by FA, inducing oxidative stress and inhibiting DNA damage repair. First of all, FA can induce and promote the formation of monoadducts, and cross-linking between DNA strands, DNA-RNA cross-linking and DNA–protein cross-linking. Secondly, FA can cause the imbalance of oxidative and antioxidant systems, while it can also cause mitochondrial dysfunction. Both pathways will eventually cause the increase of ROS production in mitochondria, which will directly attack the DNA base and the backbone, resulting in base damage and DNA breakage. At the same time, lipid peroxidation is triggered, and the aldehydes such as MDA and 4-HNE produced together with ROS participate in the covalent binding of DNA monoadducts. Finally, FA destroys damage repair proteins by virtue of its protein toxicity, thus inhibiting DNA damage repair. Abbreviations: CAT, catalase; FA, formaldehyde; GA, glutathione reductase; GSH, glutathione; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, super oxide dismutase; XO, xanthine oxidase; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal

FA-damaged DNA is involved in the brain diseases

Numerous basic and clinical investigations have demonstrated the involvement of DNA damage in the pathogenesis of various neurological disorders such as AD, PD, and brain cancers. Additionally, conclusive clinical data supports the notion that endogenous FA contributes to disease progression by inducing DNA damage. Deficiencies in endogenous fatty acid scavenging mechanisms, such as impaired activity of the detoxification enzymes mitochondrial ALDH2 and cytoplasmic ADH5, can lead to the accumulation of endogenous FA. This accumulation may contribute to genomic instability and somatic mutations by inducing DNA damage, overwhelming the DNA repair machinery, and ultimately promoting the development of leukemia (Dingler et al. 2020). A meta-analysis clearly demonstrated an association between FA exposure and some neurodegenerative diseases and brain tumors (Rana et al. 2021). But as mentioned above, detecting the different impairments induced by FA is challenging. So, in many cases, despite the clear increase in FA levels, there is limited work linking other specific types of lesions to these brain disorders.

FA levels are elevated in AD Research in both basic science and clinical trials has demonstrated that levels of FA increase progressively with age, leading to cognitive decline and memory impairment. (Tong et al. 2013, 2017). Brain FA levels were higher in senescence accelerated mice-prone 8 strain, 3-month-old APP/PS1 transgenic mice, and 6-month-old APP transgenic mice than in controls (Tong et al. 2011b). In clinical studies, FA concentrations in morning urine were positively correlated with cognitive decline in patients with AD (Tong et al. 2017). Unsurprisingly, FA levels were elevated in the hippocampus of AD patients at autopsy (Tong et al. 2011b). SSAO expression in brain samples obtained from autopsies of AD patients was increased (Ferrer et al. 2002), plasma SSAO activity is increased, which may contribute to oxidative stress (del Mar Hernandez et al. 2005). In addition to aging factors, Aβ can directly induce FA production through oxidative demethylation at serine8/26 on the one hand. In the synthetic Aβ42 mutants, FA production was found to be significantly reduced. This phenomenon was present in both single and double mutations (Fei et al. 2021). On the other hand, Aβ promote FA accumulation by inactivating FA-degrading enzymes, FDH and ADH5. FDH-Aβ complexes in brain homogenates and mitochondrial extracts demonstrated that Aβ can bind FDH. Injection of Aβ42 into the hippocampus of male wild-type mice resulted in a time-dependent increase in FA levels and a decrease in FDH activity. Similarly, Aβ42 was found to bind to human ADH5, inducing structural changes in ADH5 and thereby leading to its inactivation. This was also further confirmed in the cultured cells and APP/PS1 mice (Fei et al. 2021; Kou et al. 2022). In turn, FA accelerates the accumulation of Aβ. Cross-linking of FA with the K28 (lysine, K) residue in the β-turn of Aβ monomer promotes the formation of Aβ dimers, oligomers, and fibers. Eventually, the two form a vicious circle (Kou et al. 2022).

DNA damage in AD AD is the most common type of dementia, accounting for about 60–70% of the total number of dementia, and has been the subject of much research since its discovery in the twentieth century due to its insidious onset, long course, poor prognosis, and high burden of care (Lin et al. 2020). AD, as a disease originating in the central nervous system, produces a large amount of ROS due to the extremely high metabolic level of the nerve cells, which leads to a significant increase in DSBs, and SSBs in the cortex and hippocampus of patients with AD (Adamec et al. 1999; Shanbhag et al. 2019). Epidemiologic studies have shown that excessive amounts of FA were observed in AD patients (Tong et al. 2017). An elevated level in 8-hydroxyguanine, 8-hydroxyadenine, and 5-hydroxyuracil has been found in the temporal and parietal lobes of AD patients (Gabbita et al. 1998). In addition animal experiments also revealed significant increases in ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, decreases in GSH and superoxide dismutase levels, and elevated levels of 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OH-dG) following FA exposure in the mouse brain directly indicating the presence of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in the mouse brain (Liu et al. 2018). These data indicate that FA-induced DNA damage promotes AD onset.

FA levels are elevated in PD The relationship between PD and FA has only been gradually discovered and elucidated in recent years. In 2023, a related study constructed the first near-infrared (NIR) lysosome-targeted formaldehyde fluorescent probe (named NIR-Lyso-FA), which first detected elevated FA levels in cellular, zebrafish, and mouse PD models (Quan et al. 2023). S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) was shown to induce DA depletion and PD-like behaviors such as tremor, rigidity, and hypokinesia in rats, which may be associated with increased methylation (Charlton and Crowell 1995). Meanwhile, SAM could significantly increase the production of methanol, FA, and formic acid in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, reaching stabilization 4 h after the onset of the reaction. FA was the most toxic of these metabolites. Therefore, in terms of long-term effects, excessive carboxymethylation of proteins may be involved in SAM-induced PD-like changes and aging process through the toxic effects of FA (Lee et al. 2008). A naturally occurring lysine modification is formed by the FA reaction, and this post-translational modification has been shown to be possibly associated with normal aging and loss of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons in PD (Floor et al. 2006).

DNA damage in PD PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, occurring in 2–3% of the population over the age of 65 years, and its underlying pathology is characterized by dyskinesia and a variety of non-motor problems due to degeneration of the corpus striatum (Poewe et al. 2017). As a disease that originates in the central nervous system (CNS), the previously described conclusion that the CNS is susceptible to ROS leading to DNA damage applies equally to PD patients (Alam et al. 1997; Hegde et al. 2006; Sanders et al. 2014). Mitochondrial dysfunction is considered to be one of the bases of the pathogenesis of idiopathic and familial PD, and thus has been a major research hotspot in the field of PD (Bose and Beal 2016). FA has a relationship with PD that cannot be ignored, and above we mentioned that FA may play an important role in ROS generation for the development of PD. However, the mechanisms of FA involvement in PD are unclear.

FA levels are elevated in brain cancer It is well known that FA, as a strong carcinogen, is associated with the development of many cancers. In fact, a variety of cancers are closely related to the rise of endogenous FA, including prostate cancer, bladder cancer, breast cancer and leukemia (Ebeler et al. 1997; Kato et al. 2001; Spanel et al. 1999; Thorndike and Beck 1977; Trézl et al. 1983). Certain concentrations of FA have a predisposing effect on carcinogenesis, because FA can enhance cell proliferation while decreases apoptotic activity (Szende and Tyihák 2010). In addition, endogenous FA concentrations have been found to be elevated in cancer cells and tumor tissues (Tong et al. 2010). LSD1, one of the FA-producing enzymes, is strongly expressed in undifferentiated neuroblastoma cells and inhibition of LSD1 reduces tumor growth in vivo (Schulte et al. 2009).

DNA damage in brain cancer Common brain tumors include gliomas, meningiomas, brain metastases, etc., of which glioblastoma is the most common malignant tumor of the central nervous system, accounting for about 80% of all primary malignant tumors (Pourhanifeh et al. 2020; Weller et al. 2015). Abnormalities in DNA damage and repair may promote genomic instability, which may activate related signaling pathways and lead to cancer (O'Connor 2015). Unexpectedly, an amount of FA has been found to enhance cancer cell growth (Szende and Tyihák 2010). FA is known to be a small molecule in life, and appeared in the quality of substandard furniture and decoration materials. It has a strong carcinogenicity, by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a human carcinogen. Frequent contact or long-term exposure to FA concentrations in the environment will seriously harm human health, occupational exposure to FA is associated with the occurrence of a variety of tumors (Blackwell et al. 1981). In fact, although there are still conflicting opinions on whether low levels of FA cause cancer, low-level FA exposure should not be taken lightly. On the one hand, oral administration of low levels of FA in food additives is not carcinogenic, as it can be quickly metabolized by the liver. It is the repeated administration of large amounts of FA that causes blocking pathologic changes in the stomach (Restani and Galli 1991). On the other hand, in studies of skin carcinogenesis, it has been found that even low doses of FA (18 h, 75 mM) can delay DNA damage recognition and DNA excision repair in human fibroblasts. Reducing FA exposure in the general population may therefore significantly reduce overall cancer incidence (Luch et al. 2014). In conclusion, the carcinogenicity of low levels of FA varies across exposure concentration, durations and in different organ tissues. It is important to avoid exogenous or endogenous FA exposure as much as possible (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Brain DNA damage is involved in the occurrence and development of many brain diseases. Brain diseases associated with brain DNA damage mainly include neurodegenerative diseases and brain cancers. First, it was found that both DSBs and SSBs were significantly increased in the cortex and hippocampus of AD patients. DNA damage and repair defects can affect the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells and lead to abnormal cell metabolism and disturbance of energy production. This eventually results in neuronal dysfunction and aging. Secondly, DNA damage also plays an important role in PD. In all mechanisms, mitochondrial dysfunction caused by mtDNA damage is considered to be one of the foundations of idiopathic and familial PD pathogenesis. Finally, it is well known that DNA damage is closely related to the occurrence and development of cancer. Under the influence of carcinogenic factors, both DNA damage and abnormal repair may promote genomic instability, and then activate relevant signaling pathways, which can lead to cancer. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; PD, Parkinson's disease

Specific FA-induced DNA damage repair mechanism

Several modalities are involved in the repair of DNA damage, however the resistance of these repair systems to FA is unknown. In a recent study in 2024, using the C. elegans, which downregulates ALDH2 and ADH5, as a model of endogenous FA overload, three distinct repair modes of FA-induced DNA damage were identified: Transcription-coupled repair (TCR) operating nucleotide excision repair (NER) independently during developmental growth or through NER during adulthood, as well as in concert with global-genome NER, in the germline and early embryonic development. Among them, the investigators showed that TCR deficiency is a determinant of FA sensitivity in human somatic cells. This may provide valuable therapeutic guidance for DNA damage due to FA accumulation, which in turn leads to a variety of diseases. A good example of this is the role of the FA quencher N-acetyl-L-cysteine in relieving FA toxicity and reversing DNA repair defects during development (Rieckher et al. 2024).

FA-resistant genes drive the repair of FA-induced DNA damage

FA induces various forms of significant damage to an organism's DNA, particularly DPCs, prompting the activation of damage recognition and excision repair pathways within the cell to combat the ensuing DNA damage. However, these repair mechanisms are broad in scope and lack specificity. A recent study utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 screening has identified EXO1 as a gene that confers resistance to DNA damage induced by FA. This study demonstrates that EXO1 plays a protective and stabilizing role in the genome under FA environmental exposure, both in vivo and in vitro, acting independently of other genes. The study revealed that EXO1 knockout cell lines displayed heightened sensitivity to FA and illustrated the proficient ability of the 5'-3' exonuclease activity facilitated by EXO1 to effectively eliminate FA-induced DPCs in an in vitro setting. (Gao et al. 2023). This finding offers new insights into how FA causes DNA damage and repair, potentially leading to new treatment targets for related diseases.

FA scavengers and brain diseases

In recent years, some compounds have been found to act as FA scavengers to react spontaneously with FA, including the exogenous FA scavengers resveratrol (Res), curcumin (Cur), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), and the endogenous FA scavengers coenzyme Q10, melatonin (MT), and GSH (Zhao et al. 2021). In addition, aminoguanidine (AG) and metformin have also been shown to have FA scavenging effects (Chen et al. 2024). Among them, metformin was clearly found to protect against FA-induced DNA damage (Mai et al. 2020). AG not only rapidly interacts with FA in vitro, but also efficiently scavenges FA in vivo, thereby preventing pathophysiological processes such as FA-induced cytotoxicity and protein mis-folding (Kazachkov et al. 2007). Metformin directly reacts with endogenous FA, thereby protecting against FA-induced protein and DNA damage (Mai et al. 2020). Nanoparticle-packed coenzyme Q10 (Nano-Q10) can scavenge FA, break down Aβ dimers, and ameliorate Aβ-induced AD pathological phenotypes (Zhao et al. 2021). As mentioned earlier, GSH, an important antioxidant in the body, reacts with endogenous metabolic levels of FA to produce HSMGSH (Umansky et al. 2022), which has a more sensitive FA scavenging effect. Moreover, 1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid or α-lipoic acid acts as a natural dithiol and antioxidant cofactor for mitochondrial α-ketoacid dehydrogenase, which promotes GSH synthesis and participates in the scavenging of endogenous FA, and may therefore be beneficial for the improvement of the condition of AD patients (Shindyapina et al. 2017). EGCG, an active substance in tea polyphenols, acting as a FA scavenger (Hojo et al. 2008), can attenuate FA-induced neurotoxicity and improve cognitive behaviors (Huang et al. 2019; Na and Surh 2008). Resveratrol (Res), a polyphenolic antioxidant, can reduce FA and alleviate AD (He et al. 2016). Curcumin (Cur, a potential FA scavenger) plays a positive therapeutic role in AD (Dubey et al. 2023).

In conclusion, the therapeutic impact of FA inhibitors on AD and brain cancer is evident, whereas their potential benefits for PD remain inconclusive, suggesting a need for further investigation in this area. As previously stated, oxidative damage is the primary mechanism of DNA damage caused by FA. FA scavengers have the potential to directly mitigate the accumulation of FA and alleviate FA-induced oxidative damage and associated pathophysiological processes. This intervention may offer promise in mitigating FA-induced DNA damage and improving outcomes in brain diseases (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Drugs involved in scavenging FA (a) and possible mechanisms by which FA scavengers ameliorate brain diseases by reducing DNA damage (b). Oxidative stress is one of the most important mechanisms of FA-induced DNA damage, and FA scavengers can reduce FA-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage by directly reducing FA on the one hand, and directly resisting oxidative stress on the other. The final effect is to rescue DNA damage and improve the occurrence of AD-based brain diseases. It should be noted that there is no direct evidence of FA scavengers rescuing FA-induced DNA damage in AD, PD, and brain cancer, and most of the existing studies are about each of the two, pending more systematic studies. Figure (a) was adapted with the permission of ref. (Kazachkov et al. 2007; Mai et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2021), copyright@Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 2007; @Environ Toxicol, 2020; @ChemMedChem, 2021. Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer's disease; AG: aminoguanidine; Cur: curcumin; EGCG: polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin gallate; FA: formaldehyde; GSH: glutathione; MT: melatonin; PD: Parkinson’s disease; Q10: coenzyme Q10; Res: resveratrol; ROS: reactive oxygen species

Methods of detecting FA-induced DNA damage and brain diseases

This paper examines the mechanisms of five distinct forms of DNA damage caused by formaldehyde exposure, as well as the specific molecular structures associated with certain types of damage. Numerous prior investigations have demonstrated that various forms of DNA damage, particularly DNA adducts, can serve as specific biomarkers for various diseases and are commonly utilized in animal research. Various DNA adducts can result from the covalent interaction of various chemicals with DNA, and can be identified using sensitive methods. For instance, the DNA adduct induced by FA (N2-HOMe-dG) serves as a specific biomarker, as outlined in this study, and was effectively identified using ultrasensitive nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ULCC-MS) (Leng et al. 2019). Given the favorable attributes of DNA adducts, it is anticipated that this increasingly specific biomarker will see greater utilization in clinical settings in the foreseeable future. This is expected to advance the timeframe for disease detection, enhance diagnostic accuracy, improve the quality of medical care, and ultimately benefit a larger population of patients. The simplicity, sensitivity, specificity, and high tolerability of DNA adducts make them a promising diagnostic method. In addition, in the context of various forms of DNA damage, the comet tail cell DNA ratios observed in alkaline comet assays are frequently employed as a surrogate measure for the level of DNA fragmentation (Jimenez-Villarreal et al. 2017), the combined use of NMR and mass spectrometry detection has allowed precise structural discrimination of DPCs (Lu et al. 2010b), and interactions between nucleic acids, including DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA cross-links, present challenges in detection and necessitate the use of highly sensitive detection methods to facilitate their identification.. The combined application of nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry can accurately identify the structure of DPCs. Hence, achieving an accurate diagnosis of a specific disease state depends not only on the identification and utilization of the aforementioned exceptional biomarkers, but also on the advancement of more refined and sensitive detection technologies, facilitating early disease prognosis and the integration of precision medicine.

Prospects and challenges

The conventional pathway of DNA damage induced by FA through oxidative stress has been extensively studied. A novel mechanism has been identified by researchers, wherein FA depletes proteins involved in damage excision repair due to high proteotoxicity, leading to impaired DNA damage repair (Ortega-Atienza et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2017). This study offers a novel perspective for future research, contributes additional evidence to support the genotoxicity of FA, and suggests new avenues for the treatment and investigation of associated diseases. Hence, reduction of endogenous FA-induced DNA damage may be a new target for the treatment of several brain diseases.

Currently, there is a lack of comprehensive investigation and systematic research on the impact of FA-induced DNA damage in brain diseases, despite ample evidence supporting the accumulation of FA in the aging brain and pathological conditions, the involvement of endogenous FA in DNA damage, and the strong correlation between DNA damage and brain diseases. However, it is indisputable that FA scavengers hold significant promise and research value in the improvement of brain diseases, thereby presenting opportunities for the discovery of novel applications of current medications in the treatment of such conditions.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADH1

Alcohol dehydrogenase 1

- ADH3

Alcohol dehydrogenase 3

- ADH5

Alcohol dehydrogenase 5

- AG

Aminoguanidine

- ALDH2

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2

- AP

Apurinic/apyrimidinic

- Aβ

β-Amyloid

- BER

Base excision repair

- BRCA2

Breast cancer susceptibility gene 2

- CAT

Catalase

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- cNOS

Constitutive nitric oxide synthase

- CNS

Central nervous system

- COX-1

Cyclooxygenase-1

- CPR

Cytochrome P450 reductase

- Cur

Curcumin

- CYP450

Cytochrome P450

- DDR

DNA damage repair

- DHTIQs

6,7-Dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines

- DPCs

DNA-protein crosslinks

- DSBs

Double-strand breaks

- EGCG

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- EXO1

Exonuclease 1

- FA

Formaldehyde

- GA

Glutathione reductase

- GBM

Glioblastomas

- GSH

Glutathione

- GSH-Px

Glutathione peroxidase

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- HSMGSH

S-hydroxymethyl-glutathione

- ICLs

DNA interstrand crosslinks

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LRRK2

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- LSD1

Lysine special demethylase 1

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MDMS

Dialkanesulfonate methylene dimethyl sulfonate

- MeOH

Methanol

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- MIT

Mitochondria

- Mito5-DNA

Mito-anthraquinone-DNA

- MMA

Monomethylamine

- MPTP

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MRN

MRE11-RAD50-NBS1

- MT

Melatonin

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- NDD

Neurodegenerative diseases

- NER

Nucleotide excision repair

- NNK

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- NSCs

Neural stem cells

- PARP1

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1

- PCF

Prefrontal cortex

- PCH

Pericentromeric heterochromatin

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- Res

Resveratrol

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SA

Sarcosine

- SARDH

Sarcosine dehydrogenase

- SOD

Super oxide dismutase

- SSAO

Semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase

- SSBs

Single-strand breaks

- TBARS

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- TCR

Transcription-coupled repair

- TET1

TET methylcytosine dioxygenase 1

- XO

Xanthine oxidase

- 3C

Chromosome conformation capture

- 4-HNE

4-Hydroxynonenal

Authors’ contributions

Zixi Tian, Kai Huang, Wanting Yang, Yin Chen, Wanjia Lyu and wrote the main manuscript text. Zixi Tian, Beilei Zhu and Xu Yang prepared figures. Pin Ma and Zhiqian Ton supervised and revised the manuscript. All of the authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Zixi Tian, Kai Huang and Wanting Yang contributed equally.

Funding

This work received from the State Natural Sciences Foundation Monumental Projects (62394314), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071214), the Fund of Talent Launch Project of Oujiang Laboratory (OJQDSP2022011), the Fund from Kangning Hospital (SLC202304), and the National College Students' innovation and entrepreneurship training program (202210343071).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We declare that all work described here has not been published before and that its publication has been approved by all co-authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure statement

We report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Highlights.

•Gaseous formaldehyde (FA) can damage DNA and impact human health.

•Age-related endogenous FA contributes to neurodegenerative diseases.

•FA elicits DBS and crosslinks of DNA-DNA, DNA-RNA, and DNA-protein.

•EXO1 gene and FA scavengers reduce FA-induced DNA damage.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zixi Tian, Kai Huang and Wanting Yang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ping Ma, Email: maping@hbstu.edu.cn.

Zhiqian Tong, Email: tzqbeida@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- Adamec E, Vonsattel JP, Nixon RA. DNA strand breaks in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1999;849:67–77. 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam ZI, Jenner A, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Cairns N, Marsden CD, Jenner P, Halliwell B. Oxidative DNA damage in the parkinsonian brain: an apparent selective increase in 8-hydroxyguanine levels in substantia nigra. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1196–203. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Mutagenesis. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:31–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford P, Fox BW. The role of formaldehyde in methylene dimethanesulphonate-induced DNA cross-links and its relevance to cytotoxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 1981;38:119–28. 10.1016/0009-2797(81)90158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M, Kang H, Thomas A, Infante P. Formaldehyde: evidence of carcinogenicity. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J ;1981 42:A34, A6, A8, passim [PubMed]

- Bose A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 1):216–31. 10.1111/jnc.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton CG, Crowell B Jr. Striatal dopamine depletion, tremors, and hypokinesia following the intracranial injection of S-adenosylmethionine: a possible role of hypermethylation in parkinsonism. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1995;26:269–84. 10.1007/bf02815143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chen W, Zhang J, Zhao H, Cui J, Wu J, Shi A. Dual effects of endogenous formaldehyde on the organism and drugs for its removal. J Appl Toxicol. 2024;44:798–817. 10.1002/jat.4546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Ji Q, Wang L, Wang C, Liu G, Wang L. Reducing oxidative protein folding alleviates senescence by minimizing ER-to-nucleus H O release. EMBO reports. 2023;24:e56439. 10.15252/embr.202256439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dator RP, Murray KJ, Luedtke MW, Jacobs FC, Kassie F, Nguyen HD, Villalta PW, Balbo S. Identification of Formaldehyde-Induced DNA-RNA Cross-Links in the A/J Mouse Lung Tumorigenesis Model. Chem Res Toxicol. 2022;35:2025–36. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.2c00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Mar HM, Esteban M, Szabo P, Boada M, Unzeta M. Human plasma semicarbazide sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO), beta-amyloid protein and aging. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384:183–7. 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingler FA, Wang M, Mu A, Millington CL, Oberbeck N, Watcham S, Pontel LB, Kamimae-Lanning AN, Langevin F, Nadler C, Cordell RL, Monks PS, Yu R, Wilson NK, Hira A, Yoshida K, Mori M, Okamoto Y, Okuno Y, Muramatsu H, Shiraishi Y, Kobayashi M, Moriguchi T, Osumi T, Kato M, Miyano S, Ito E, Kojima S, Yabe H, Yabe M, Matsuo K, Ogawa S, Göttgens B, Hodskinson MRG, Takata M, Patel KJ. Two Aldehyde Clearance Systems Are Essential to Prevent Lethal Formaldehyde Accumulation in Mice and Humans. Mol Cell. 2020;80:996-1012.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey T, Sonawane SK, Mannava MC, Nangia AK, Chandrashekar M, Chinnathambi S. The inhibitory effect of Curcumin-Artemisinin co-amorphous on Tau aggregation and Tau phosphorylation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;221:112970. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeler SE, Clifford AJ, Shibamoto T. Quantitative analysis by gas chromatography of volatile carbonyl compounds in expired air from mice and human. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;702:211–5. 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang EF, Kassahun H, Croteau DL, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Marosi K, Lu H, Shamanna RA, Kalyanasundaram S, Bollineni RC, Wilson MA, Iser WB, Wollman BN, Morevati M, Li J, Kerr JS, Lu Q, Waltz TB, Tian J, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, Nilsen H, Bohr VA. NAD(+) Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell Metab. 2016;24:566–81. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui MY. Formaldehyde. J Appl Toxicol. 1983;3:264–5. 10.1002/jat.2550030510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei X, Zhang Y, Mei Y, Yue X, Jiang W, Ai L, Yu Y, Luo H, Li H, Luo W, Yang X, Lyv J, He R, Song W, Tong Z. Degradation of FA reduces Aβ neurotoxicity and Alzheimer-related phenotypes. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:5578–91. 10.1038/s41380-020-00929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei X, Tong Z. Endogenous formaldehyde regulates memory. Acta Physiologica Sinica. 2020;72:12 (in Chinese with English abstract). 10.13294/j.aps.2020.0026 [PubMed]

- Feldman MY. Reactions of nucleic acids and nucleoproteins with formaldehyde. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1973;13:1–49. 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Lizcano JM, Hernández M, Unzeta M. Overexpression of semicarbazide sensitive amine oxidase in the cerebral blood vessels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Neurosci Lett. 2002;321:21–4. 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floor E, Maples AM, Rankin CA, Yaganti VM, Shank SS, Nichols GS, O’Laughlin M, Galeva NA, Williams TD. A one-carbon modification of protein lysine associated with elevated oxidative stress in human substantia nigra. J Neurochem. 2006;97:504–14. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel-conrat H, Cooper M, Olcott HS. The Reaction of Formaldehyde with Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1945;67:950–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbita SP, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Increased nuclear DNA oxidation in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2034–40. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Guitton-Sert L, Dessapt J, Coulombe Y, Rodrigue A, Milano L, Blondeau A, Larsen NB, Duxin JP, Hussein S, Fradet-Turcotte A, Masson JY. A CRISPR-Cas9 screen identifies EXO1 as a formaldehyde resistance gene. Nat Commun. 2023;14:381. 10.1038/s41467-023-35802-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas NJ, Nguyen VP. Neuromodulation of Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity, Learning, and Memory by Noradrenaline. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:17–33. 10.2174/187152407780059196. [Google Scholar]

- Hasemann CA, Kurumbail RG, Boddupalli SS, Peterson JA, Deisenhofer J. Structure and function of cytochromes P450:a comparative analysis of three crystal structures. Structure. 1995;3:41–62. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Li Z, Rizak JD, Wu S, Wang Z, He R, Su M, Qin D, Wang J, Hu X. Resveratrol Attenuates Formaldehyde Induced Hyperphosphorylation of Tau Protein and Cytotoxicity in N2a Cells. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:598. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck HD, White EL, Casanova-Schmitz M. Determination of formaldehyde in biological tissues by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1982;9:347–53. 10.1002/bms.1200090808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde ML, Gupta VB, Anitha M, Harikrishna T, Shankar SK, Muthane U, Subba Rao K, Jagannatha Rao KS. Studies on genomic DNA topology and stability in brain regions of Parkinson’s disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;449:143–56. 10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EA, Frey BL, Smith LM, Auble DT. Formaldehyde crosslinking: a tool for the study of chromatin complexes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:26404–11. 10.1074/jbc.R115.651679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo H, Fukai K, Nanjo F. Application of green tea catechins as formaldehyde scavengers. 2008

- Hu CW, Chang YJ, Cooke MS, Chao MR. DNA Crosslinkomics: A Tool for the Comprehensive Assessment of Interstrand Crosslinks Using High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2019;91:15193–203. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Solomon MS, Hopkins PB. Formaldehyde preferentially interstrand cross-links duplex DNA through deoxyadenosine residues at the sequence 5’-d(AT). J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9240–1. 10.1021/ja00049a097. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lu Y, Zhang B, Yang S, Zhang Q, Cui H, Lu X, Zhao Y, Yang X, Li R. Antagonistic effect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on neurotoxicity induced by formaldehyde. Toxicology. 2019;412:29–36. 10.1016/j.tox.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Villarreal J, Betancourt-Martinex ND, Carranza-Rosales P, Valdez EV, Guzman-Delgado NE, Lopez-Marquez FC, Moran-Martinez J. Formaldehyde induces DNA strand breaks on spermatozoa and lymphocytes of Wistar rats. Tsitol Genet. 2017;51:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalász H. Biological role of formaldehyde, and cycles related to methylation, demethylation, and formaldehyde production. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2003;3:175–92. 10.2174/1389557033488187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Burke PJ, Koch TH, Bierbaum VM. Formaldehyde in human cancer cells: detection by preconcentration-chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2992–7. 10.1021/ac001498q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazachkov M, Chen K, Babiy S, Yu PH. Evidence for in vivo scavenging by aminoguanidine of formaldehyde produced via semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase-mediated deamination. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:1201–7. 10.1124/jpet.107.124123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Dekker J. Formaldehyde Cross-Linking. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2018;2018. 10.1101/pdb.prot082594 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Klockenbusch C, O’Hara JE, Kast J. Advancing formaldehyde cross-linking towards quantitative proteomic applications. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:1057–67. 10.1007/s00216-012-6065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou Y, Zhao H, Cui D, Han H, Tong Z. Formaldehyde toxicity in age-related neurological dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;73:101512. 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautrup S, Caponio D, Cheung HH, Piccoli C, Stevnsner T, Chan WY, Fang EF. Studying Werner syndrome to elucidate mechanisms and therapeutics of human aging and age-related diseases. Biogerontology. 2019;20:255–69. 10.1007/s10522-019-09798-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ES, Chen H, Hardman C, Simm A, Charlton C. Excessive S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methylation increases levels of methanol, formaldehyde and formic acid in rat brain striatal homogenates: possible role in S-adenosyl-L-methionine-induced Parkinson’s disease-like disorders. Life Sci. 2008;83:821–7. 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng J, Liu CW, Hartwell HJ, Yu R, Lai Y, Bodnar WM, Lu K, Swenberg JA. Evaluation of inhaled low-dose formaldehyde-induced DNA adducts and DNA-protein cross-links by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Arch Toxicol. 2019;93:763–73. 10.1007/s00204-019-02393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Kapoor A, Gu Y, Chow MJ, Peng J, Zhao K, Tang D. Contributions of DNA Damage to Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. 10.3390/ijms21051666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Li CM, Lu Z, Ding S, Yang X, Mo J. Studies on formation and repair of formaldehyde-damaged DNA by detection of DNA-protein crosslinks and DNA breaks. Front Biosci. 2006;11:991–7. 10.2741/1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang Y, Wu R, Ye M, Zhao Y, Kang J, Ma P, Li J, Yang X. Acute formaldehyde exposure induced early Alzheimer-like changes in mouse brain. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2018;28:95–104. 10.1080/15376516.2017.1368053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Collins LB, Ru H, Bermudez E, Swenberg JA. Distribution of DNA adducts caused by inhaled formaldehyde is consistent with induction of nasal carcinoma but not leukemia. Toxicol Sci. 2010a;116:441–51. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Ye W, Zhou L, Collins LB, Chen X, Gold A, Ball LM, Swenberg JA. Structural characterization of formaldehyde-induced cross-links between amino acids and deoxynucleosides and their oligomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2010b;132:3388–99. 10.1021/ja908282f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luch A, Frey FC, Meier R, Fei J, Naegeli H. Low-dose formaldehyde delays DNA damage recognition and DNA excision repair in human cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai X, Zhou F, Lin P, Lin S, Gao J, Ma Y, Fan R, Ting W, Huang C, Yin D, Kang Z. Metformin scavenges formaldehyde and attenuates formaldehyde-induced bovine serum albumin crosslinking and cellular DNA damage. Environ Toxicol. 2020;35:1170–8. 10.1002/tox.22982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez SE, Vaglenova J, Sabrià J, Martínez MC, Farrés J, Parés X. Distribution of alcohol dehydrogenase mRNA in the rat central nervous system. Consequences for brain ethanol and retinoid metabolism. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5045–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M, Arumugam T. Hallmarks of Brain Aging: Adaptive and Pathological Modification by Metabolic States. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1176–99. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee JD, von Hippel PH. Formaldehyde as a probe of DNA structure. I. Reaction with exocyclic amino groups of DNA bases. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1281–96. 10.1021/bi00677a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee JD, von Hippel PH. Formaldehyde as a probe of DNA structure. II. Reaction with endocyclic imino groups of DNA bases. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1297–303. 10.1021/bi00677a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Y, Jiang C, Wan Y, Lv J, Jia J, Wang X, Yang X, Tong Z. Aging-associated formaldehyde-induced norepinephrine deficiency contributes to age-related memory decline. Aging Cell. 2015;14:659–68. 10.1111/acel.12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz B, Kersten GF, Hoogerhout P, Brugghe HF, Timmermans HA, de Jong A, Meiring H, ten Hove J, Hennink WE, Crommelin DJ, Jiskoot W. Identification of formaldehyde-induced modifications in proteins: reactions with model peptides. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6235–43. 10.1074/jbc.M310752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misiak M, Vergara Greeno R, Baptiste BA, Sykora P, Liu D, Cordonnier S, Fang EF, Croteau DL, Mattson MP, Bohr VA. DNA polymerase β decrement triggers death of olfactory bulb cells and impairs olfaction in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2017;16:162–72. 10.1111/acel.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa S, Brand MD. Mitochondrial matrix reactive oxygen species production is very sensitive to mild uncoupling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1300–1. 10.1042/bst0311300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na HK, Surh YJ. Modulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant and detoxifying enzyme induction by the green tea polyphenol EGCG. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1271–8. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadalutti CA, Stefanick DF, Zhao ML, Horton JK, Prasad R, Brooks AM, Griffith JD, Wilson SH. Mitochondrial dysfunction and DNA damage accompany enhanced levels of formaldehyde in cultured primary human fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5575. 10.1038/s41598-020-61477-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata T. Diabetes and semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO) activity: a review. Life Sci. 2006;79:417–22. 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60:547–60. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr BA, Clay MR, Pinto EM, Kesserwan C. An update on the central nervous system manifestations of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139:669–87. 10.1007/s00401-019-02055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Atienza S, Green SE, Zhitkovich A. Proteasome activity is important for replication recovery, CHK1 phosphorylation and prevention of G2 arrest after low-dose formaldehyde. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:135–41. 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Atienza S, Rubis B, McCarthy C, Zhitkovich A. Formaldehyde Is a Potent Proteotoxic Stressor Causing Rapid Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1 Activation and Lys48-Linked Polyubiquitination of Proteins. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:2857–68. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban J, Babu N, Masthan K, Shanmugam K. Kesavan K DNA adducts. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2015;8:113–6. 10.13005/bpj/660. [Google Scholar]

- Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, Halliday GM, Brundin P, Volkmann J, Schrag AE, Lang AE. Parkinson Disease Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17013. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourhanifeh MH, Vosough M, Mahjoubin-Tehran M, Hashemipour M, Nejati M, Abbasi-Kolli M, Sahebkar A, Mirzaei H. Autophagy-related microRNAs: Possible regulatory roles and therapeutic potential in and gastrointestinal cancers. Pharmacol Res. 2020;161:105133. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumuye PP, Evison BJ, Konda SK, Collins JG, Kelso C, Medan J, Sleebs BE, Watson K, Phillips DR, Cutts SM. Formaldehyde-activated WEHI-150 induces DNA interstrand crosslinks with unique structural features. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020;28:115260. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang M, Xiao R, Su T, Wu BB, Tong ZQ, Liu Y, He RQ. A novel mechanism for endogenous formaldehyde elevation in SAMP8 mouse. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:1039–53. 10.3233/JAD-131595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan W, Zhang G, Li Y, Song W, Zhan J, Lin W. Upregulation of Formaldehyde in Parkinson’s Disease Found by a Near-Infrared Lysosome-Targeted Fluorescent Probe. Anal Chem. 2023;95:2925–31. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c04567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Loss of DNA-protein crosslinks from formaldehyde-exposed cells occurs through spontaneous hydrolysis and an active repair process linked to proteosome function. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1573–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana I, Rieswijk L, Steinmaus C, Zhang L. Formaldehyde and Brain Disorders: A Meta-Analysis and Bioinformatics Approach. Neurotox Res. 2021;39:924–48. 10.1007/s12640-020-00320-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restani P, Galli CL. Oral toxicity of formaldehyde and its derivatives. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1991;21:315–28. 10.3109/10408449109019569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckher M, Gallrein C, Alquezar-Artieda N, Bourached-Silva N, Vaddavalli PL, Mares D, Backhaus M, Blindauer T, Greger K, Wiesner E, Pontel LB, Schumacher B. Distinct DNA repair mechanisms prevent formaldehyde toxicity during development, reproduction and aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52:8271–85. 10.1093/nar/gkae519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rominiyi O, Collis SJ. DDRugging glioblastoma: understanding and targeting the DNA damage response to improve future therapies. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:11–41. 10.1002/1878-0261.13020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LH, McCoy J, Hu X, Mastroberardino PG, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ, Chu CT, Van Houten B, Greenamyre JT. Mitochondrial DNA damage: molecular marker of vulnerable nigral neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:214–23. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte JH, Lim S, Schramm A, Friedrichs N, Koster J, Versteeg R, Ora I, Pajtler K, Klein-Hitpass L, Kuhfittig-Kulle S, Metzger E, Schüle R, Eggert A, Buettner R, Kirfel J. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 is strongly expressed in poorly differentiated neuroblastoma: implications for therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2065–71. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag NM, Evans MD, Mao W, Nana AL, Seeley WW, Adame A, Rissman RA, Masliah E, Mucke L. Early neuronal accumulation of DNA double strand breaks in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:77. 10.1186/s40478-019-0723-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y, Lederman HM. Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T): An emerging dimension of premature ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;33:76–88. 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyapina AV, Komarova TV, Sheshukova EV, Ershova NM, Tashlitsky VN, Kurkin AV, Yusupov IR, Mkrtchyan GV, Shagidulin MY, Dorokhov YL. The Antioxidant Cofactor Alpha-Lipoic Acid May Control Endogenous Formaldehyde Metabolism in Mammals. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:651. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H. Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:291–5. 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanel P, Smith D, Holland TA, Al Singary W, Elder JB. Analysis of formaldehyde in the headspace of urine from bladder and prostate cancer patients using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1999;13:1354–9. 10.1002/(sici)1097-0231(19990730)13:14%3c1354::Aid-rcm641%3e3.0.Co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryo Rahmanto A, Blum CJ, Scalera C, Heidelberger JB, Mesitov M, Horn-Ghetko D, Gräf JF, Mikicic I, Hobrecht R, Orekhova A, Ostermaier M, Ebersberger S, Möckel MM, Krapoth N, Da Silva FN, Mizi A, Zhu Y, Chen JX, Choudhary C, Papantonis A, Ulrich HD, Schulman BA, König J, Beli P. K6-linked ubiquitylation marks formaldehyde-induced RNA-protein crosslinks for resolution. Mol Cell. 2023;83:4272-89.e10. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland BW, Toews J, Kast J. Utility of formaldehyde cross-linking and mass spectrometry in the study of protein-protein interactions. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:699–715. 10.1002/jms.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykora P, Misiak M, Wang Y, Ghosh S, Leandro GS, Liu D, Tian J, Baptiste BA, Cong WN, Brenerman BM, Fang E, Becker KG, Hamilton RJ, Chigurupati S, Zhang Y, Egan JM, Croteau DL, Wilson DM 3rd, Mattson MP, Bohr VA. DNA polymerase β deficiency leads to neurodegeneration and exacerbates Alzheimer disease phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:943–59. 10.1093/nar/gku1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szende B, Tyihák E. Effect of formaldehyde on cell proliferation and death. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:1273–82. 10.1042/cbi20100532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SLW, Chadha S, Liu Y, Gabasova E, Perera D, Ahmed K, Constantinou S, Renaudin X, Lee M, Aebersold R, Venkitaraman AR. A Class of Environmental and Endogenous Toxins Induces BRCA2 Haploinsufficiency and Genome Instability. Cell. 2017;169:1105-18.e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XQ, Ren YK, Zhou CF, Yang CT, Gu HF, He JQ, Chen RQ, Zhuang YY, Fang HR, Wang CY. Hydrogen sulfide prevents formaldehyde-induced neurotoxicity to PC12 cells by attenuation of mitochondrial dysfunction and pro-apoptotic potential. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:16–24. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike J, Beck WS. Production of formaldehyde from N5-methyltetrahydrofolate by normal and leukemic leukocytes. Cancer Res. 1977;37:1125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Luo W, Wang Y, Yang F, Han Y, Li H, Luo H, Duan B, Xu T, Maoying Q, Tan H, Wang J, Zhao H, Liu F, Wan Y. Tumor tissue-derived formaldehyde and acidic microenvironment synergistically induce bone cancer pain. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10234. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Zhang J, Luo W, Wang W, Li F, Li H, Luo H, Lu J, Zhou J, Wan Y, He R. Urine formaldehyde level is inversely correlated to mini mental state examination scores in senile dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:31–41. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Han C, Luo W, Wang X, Li H, Luo H, Zhou J, Qi J, He R. Accumulated hippocampal formaldehyde induces age-dependent memory decline. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:583–96. 10.1007/s11357-012-9388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Wang W, Luo W, Lv J, Li H, Luo H, Jia J, He R. Urine Formaldehyde Predicts Cognitive Impairment in Post-Stroke Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55:1031–8. 10.3233/jad-160357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Han C, Miao J, Lu J, He R. Excess Endogenous Formaldehyde Induces Memory Decline. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2011a;38:5 (in Chinese). 10.3724/SP.J.1206.2011.00241

- Trewick SC, Henshaw TF, Hausinger RP, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B. Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature. 2002;419:174–8. 10.1038/nature00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trézl L, Rusznák I, Tyihák E, Szarvas T, Szende B. Spontaneous N epsilon-methylation and N epsilon-formylation reactions between L-lysine and formaldehyde inhibited by L-ascorbic acid. Biochem J. 1983;214:289–92. 10.1042/bj2140289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler DD. Evidence of a phosphate-transporter system in the inner membrane of isolated mitochondria. Biochem J. 1969;111:665–78. 10.1042/bj1110665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky C, Morellato AE, Rieckher M, Scheidegger MA, Martinefski MR, Fernández GA, Pak O, Kolesnikova K, Reingruber H, Bollini M, Crossan GP, Sommer N, Monge ME, Schumacher B, Pontel LB. Endogenous formaldehyde scavenges cellular glutathione resulting in redox disruption and cytotoxicity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:745. 10.1038/s41467-022-28242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert P, Stingele J. DNA-Protein Crosslinks and Their Resolution. Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91:157–81. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-032620-105820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M, Wick W, Aldape K, Brada M, Berger M, Pfister SM, Nishikawa R, Rosenthal M, Wen PY, Stupp R, Reifenberger G. Glioma Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15017. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Luo J, He Y, Jiang L, Zhong L, Shi Y. BRCA2 gene mutation in cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31705. 10.1097/md.0000000000031705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Cauglin C, Wempe K, Gubisne-Haberle D. A novel sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography/electrochemical procedure for measuring formaldehyde produced from oxidative deamination of methylamine and in biological samples. Anal Biochem. 2003;318:285–90. 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zararsiz I, Meydan S, Sarsilmaz M, Songur A, Ozen OA, Sogut S. Protective effects of omega-3 essential fatty acids against formaldehyde-induced cerebellar damage in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;27:489–95. 10.1177/0748233710389852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Huang X, Tong Z. Formaldehyde-Crosslinked Nontoxic Aβ Monomers to Form Toxic Aβ Dimers and Aggregates: Pathogenicity and Therapeutic Perspectives. ChemMedChem. 2021;16:3376–90. 10.1002/cmdc.202100428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Cordes J, Caban KM, Götz MJ, Mackens-Kiani T, Veltri AJ, Sinha NK, Weickert P, Kaya S, Hewitt G, Nedialkova DD, Fröhlich T, Beckmann R, Buskirk AR, Green R, Stingele J. RNF14-dependent atypical ubiquitylation promotes translation-coupled resolution of RNA-protein crosslinks. Mol Cell. 2023;83:4290-303.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorova LD, Popkov VA, Plotnikov EY, Silachev DN, Pevzner IB, Jankauskas SS, Babenko VA, Zorov SD, Balakireva AV, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ, Zorov DB. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Anal Biochem. 2018;552:50–9. 10.1016/j.ab.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.