Abstract

Natural secondary metabolites are medically, agriculturally, and industrially beneficial to humans. For mass production, a heterologous production system is required, and various metabolic engineering trials have been reported in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase their production levels. Recently, filamentous fungi, especially Aspergillus oryzae, have been expected to be excellent hosts for the heterologous production of natural products; however, large-scale metabolic engineering has hardly been reported. Here, we elucidated candidate metabolic pathways to be modified for increased model terpene production by RNA-seq and metabolome analyses in A. oryzae and selected pathways such as ethanol fermentation, cytosolic acetyl-CoA production from citrate, and the mevalonate pathway. We performed metabolic modifications targeting these pathways using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and demonstrated their effectiveness in heterologous terpene production. Finally, a strain containing 13 metabolic modifications was generated, which showed enhanced heterologous production of pleuromutilin (8.5-fold), aphidicolin (65.6-fold), and ophiobolin C (28.5-fold) compared to the unmodified A. oryzae strain. Therefore, the strain generated by engineering multiple metabolic pathways can be employed as a versatile highly-producing host for a wide variety of terpenes.

Subject terms: Applied microbiology, Fungal genetics, Metabolic engineering, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

Genome editing-mediated large-scale engineering, which modified 13 genes involved in multiple metabolic pathways, enabled us to develop a versatile filamentous fungal host highly-producing heterologous natural products.

Introduction

Natural products, such as polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs), and terpenes, are produced as secondary metabolites by a wide range of organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and plants, and they are utilised, among their derivatives, as pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, nutraceuticals, and volatile flavours1–5. However, in many cases, their production levels from the original source are not sufficient for evaluating their activities or industrial production, and organic chemical synthesis is not suitable for eco-environments3–6. Therefore, heterologous production systems using microorganisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been developed3–5.

Metabolic engineering to increase the availability of substrates for natural products is an effective strategy for enhancing their production and has been widely investigated. In addition, accumulated metabolic engineering and rewiring into a single strain employing different genetic modification technologies, such as the potentiation, shutoff, and reconstruction of specific metabolic pathways, have recently been applied to the production of various natural products, including polyketides and terpenes3–5,7. In particular, multiple metabolic pathways are involved in terpene biosynthesis, and attempts have been made to consolidate modifications which ultimately increase terpene titre within single production strains3–5,7. Terpenes are produced using metabolites derived from isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), which is synthesised from pyruvate and acetyl-CoA via the methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in E. coli or the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in S. cerevisiae (Supplementary Fig. 1). Examples of enhanced production strains include an E. coli strain where expressional optimisation of eight MEP pathway genes achieved 1 g/L production of taxadiene, a precursor for Taxol8. In S. cerevisiae, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMGR) is a rate-limiting enzyme in the MVA pathway (Supplementary Fig. 1), and overexpression of a truncated HMG-CoA variant (tHMG1), which is released from negative feedback regulation, increases the production of the triterpenoid protopanaxadiol9. In addition, it was reported that the production of a sesquiterpene amorphadiene, a precursor for artemisinin, was increased by overexpression of multiple genes involved in the MVA pathway10, which has been also applied for various terpene and terpenoid production11–16. Moreover, activation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) bypass, which is a cytosolic pathway to synthesise acetyl-CoA from pyruvate via acetaldehyde and acetate (Supplementary Fig. 1), overexpression of an alcohol dehydrogenase gene ADH2 involved in reverse reaction of ethanol fermentation, and inhibition of glyoxylate cycle showed as additive effect on production of a sesquiterpene α-santalene with modification targeting the MVA pathway17.

Filamentous fungi, including Aspergillus oryzae, have also been used as hosts for the heterologous production of polyketides, NRPs, and terpenes4,18,19 and are especially suitable for the production of natural products originally produced by filamentous fungi, such as pleuromutilin20,21 natively produced by a basidiomycete, aphidicolin22, and ophiobolins23,24, which are natively produced by ascomycetes. However, unlike E. coli and S. cerevisiae, large-scale metabolic engineering for the enhanced production of natural products has rarely been performed in filamentous fungi because of the absence of efficient genetic modification tools. Recently, we established a CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique as an efficient genetic modification tool and developed a plasmid recycling method for A. oryzae that allowed repetitive genetic modifications to accumulate an unlimited number of genetic modifications in a single strain25,26. Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, Yuan et al. increased the production of a sesterterpene, mangicol J, by overexpressing the MVA pathway genes27. However, the versatility of the strain overexpressing the MVA pathway genes for other products is unclear, and engineering of pathways other than the MVA pathway remains to be investigated to further enhance the production of natural products.

Here, the candidate metabolic pathways to be modified were evaluated by RNA-seq and metabolome analyses in A. oryzae. Subsequently, we attempted to construct a versatile highly-producing host for the heterologous production of natural products through metabolic engineering of these candidate pathways using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing.

Results

Elucidation of metabolic pathways involved in the heterologous production of pleuromutilin

To evaluate the productivity of natural products, we selected the diterpene pleuromutilin as a model compound because it has already been heterologously produced in A. oryzae20,21. Pleuromutilin is an antibiotic compound naturally produced by the basidiomycete fungus Clitopilus passeckerianus and is considered a lead compound for useful derivatives because of its unique ability to inhibit protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit of bacteria20,28,29. As pleuromutilin is biosynthesised from farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), an intermediate of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway, by seven enzymes, Ple1–7 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), the expression cassettes of these biosynthetic genes were sequentially integrated with a single copy into the wA, niaD, and pyrG loci of the A. oryzae wild strain RIB40 using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, yielding the PL001 strain (Supplementary Fig. 2b). For expression of ple genes, the strongly inducible amyB/constitutive enoA promoters of A. oryzae (PamyB and PenoA, respectively) and the constitutive AngpdA promoter of A. nidulans (PAngpdA) were used according to the previous report21. Deletion of the wA, niaD, and pyrG genes caused phenotypic changes, and thereby, the desired strain, in which the ple1–7 expression cassettes were introduced, was easily obtained. In the PL001 strain, pleuromutilin production was detected using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and the extract showed antibiotic activity against Bacillus subtilis (Supplementary Fig. 2c). In addition, we attempted simultaneous integration of the ple1–7 expression cassettes using a genome editing plasmid targeting all three loci with each donor plasmid and successfully obtained the pleuromutilin-producing strain tPL001 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The level of pleuromutilin production in the PL001 strain increased to 25.9 ± 1.3 mg/L through initial 5 days of growth and did not change after 6 days of growth (Supplementary Fig. 2d).

Although engineering of the carbon metabolic pathway promises to enhance the heterologous production of natural products, the carbon metabolic pathway involved in the heterologous production of natural products is not well understood in A. oryzae. Therefore, its carbon metabolic features must be characterised for metabolic engineering. First, we evaluated the growth and carbon metabolites of the culture supernatant, including maltose, glucose, and ethanol. As the model compound pleuromutilin was produced through 5 days of growth, these analyses were performed using the mycelia of the A. oryzae RIB40 strain, which was cultured in maltose peptone yeast (MPY) liquid medium containing 2% maltose as the carbon source from day 1 to day 5. The RIB40 strain proliferated actively within the first day/gradually up to 3 days and then shifted to the stationary phase (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Maltose was rapidly consumed within day 1, and glucose and ethanol were produced; however, they were also consumed after 2 and 3 days of growth, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Considering these results, we performed time-course RNA-seq and metabolome analyses to evaluate carbon metabolic pathways. As terpenes are produced from FPP, the carbon metabolic pathways involved in FPP production, such as the glycolytic pathway, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, mevalonate pathway, and biosynthetic pathway to FPP, are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4. Genes that function in these metabolic pathways in A. oryzae were searched based on the pathway information in KEGG and the RNA-seq results (Supplementary Table 1). As most genes involved in glycolysis showed high expression levels through 5 days of growth (Fig. 1), we concluded that modification of the glycolytic pathway would not be effective in enhancing pleuromutilin production.

Fig. 1. Expression levels of the genes involved in the terpene production-related metabolic pathways.

The RIB40 strain was cultured in an MPY liquid medium for 1–5 days, and RNA-seq analyses were performed using total RNA extracted from the mycelia at each time point. The TPM values of the genes are the means of three independent RNA-seq analyses and are shown as a heatmap using the values of log2(TPM + 1) at each time point.

In S. cerevisiae, cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA is generated by the PDH bypass, and its availability is important to produce its downstream metabolites via the MVA pathway30. In response to this bypass, S. cerevisiae produces ethanol from acetaldehyde under glucose-rich conditions31, and eliminating ethanol fermentation results in a high accumulation of cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA32. However, the PDH bypass and ethanol fermentation pathways in A. oryzae have not yet been characterised. The RNA-seq results showed high expression levels of the pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc) and alcohol dehydrogenase (adh) genes involved in ethanol fermentation at the early stage of growth (Fig. 1), implying that shutting off ethanol fermentation could lead to enhanced pleuromutilin production. In addition, as the RNA-seq results also showed low expression levels of genes involved in the MVA pathway (Fig. 1), it is possible that potentiation of this pathway could also enhance pleuromutilin production. Furthermore, the amounts of the metabolites in the TCA cycle tended to exhibit relatively high levels from 3 days to 5 days of growth (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting the potential for modification of the TCA cycle to increase the production of pleuromutilin. Taken together, we concluded that modification of the PDH bypass, the ethanol fermentation pathway, the MVA pathways, and the TCA cycle has the potential to increase pleuromutilin production.

Effects of metabolic modifications for increased cytosolic acetyl-CoA on heterologous pleuromutilin production

The PDH bypass and ethanol fermentation pathway utilise pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALD), acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to produce acetyl-CoA and ethanol (Fig. 2a), and these enzymes of A. oryzae were identified as follows; AO090003000661 for PDC, AO090003001112 for ACS, AO090023000467 for ALD, and AO090009000634 for ADH (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, these genes were deleted from the pleuromutilin-producing strain (Supplementary Fig. 5). The deletion of pdc and adh involved in ethanol fermentation resulted in increased pleuromutilin production, 53.8 ± 10.0 mg/L, and 47.5 ± 1.2 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 2b). This suggests a potential competition between pleuromutilin production and ethanol fermentation. Decreased ethanol levels in the culture supernatants of the pdc and adh deletion strains support this possibility (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the deletion of acs and ald, which are involved in the PDH bypass, did not alter pleuromutilin titre compared to the original production strain, PL001 (Fig. 2b). This suggests that the PDH bypass hardly contributes to terpene production in A. oryzae, unlike S. cerevisiae, in which the cytosolic acetyl-CoA used for terpene production is mainly supplied by this bypass30.

Fig. 2. Effects of metabolic engineering in ethanol fermentation and the PDH bypass on pleuromutilin production.

a The ethanol fermentation pathway and the PDH bypass with the enzymes catalysing each reaction. The processes with the proteins indicated as blue box were blocked by gene deletion. Pleuromutilin production (b) and ethanol amount in the culture supernatant (c) in the indicated strains. The strains were cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30 °C for 5 days (b) and 1 day (c). Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) with dot plot indicating each data of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test compared to the WT strain. “N.D.” indicates “not detected”.

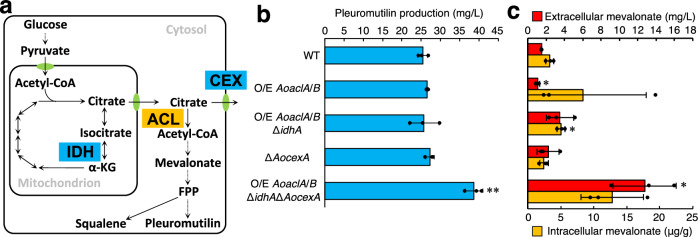

As the PDH bypass was not suggested to contribute to terpene production in A. oryzae, acetyl-CoA introduced into the MVA pathway was possibly supplied from another pathway via mitochondrial citrate (Fig. 3a). Therefore, we first analysed the AoaclA and AoaclB genes encoding ATP citrate lyase (ACL), which catalyses the conversion of citrate to acetyl-CoA in A. oryzae (Supplementary Table 1). The single- and double-deletion strains of AoaclA and AoaclB, which were constructed from the pleuromutilin-producing strain, exhibited severe growth defects on a medium containing glucose as the carbon source, in agreement with the findings in A. nidulans (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b)33. When pleuromutilin production levels were measured, no change in the AoaclA and AoaclB single deletion strains was observed (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Furthermore, the production level could not be measured in the double deletion strain because of severe growth defects. Therefore, we could not evaluate the contribution of ACL to terpene production. For further investigation, a strain overexpressing AoaclA and AoaclB from the constitutive tef1 promoter of A. oryzae (Ptef1)34 at their native loci was constructed, and its pleuromutilin production was measured; pleuromutilin production did not change in the strain (Supplementary Fig. 7a, Fig. 3b). Considering this result, we hypothesised that overexpression of AoaclA and AoaclB did not affect pleuromutilin production due to low cytosolic citrate levels and attempted to add further genetic modifications for cytosolic citrate accumulation. Although genes related to the TCA cycle were predicted to be essential for growth, A. oryzae possesses two genes, idhA and idhB, encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) (Supplementary Table 1), and a single deletion of these genes was expected to increase cytosolic citrate levels without lethality. As expected, an idhA deletion strain was obtained, despite severe growth defects (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). However, idhA deletion did not affect pleuromutilin production in the AoaclA and AoaclB overexpressing strains (Fig. 3b), indicating the need for additional modifications. To investigate whether immediate export of citrate cancelled the effects of these genetic modifications, AocexA, which encodes a citrate exporter (CEX) in A. oryzae35, was deleted (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). AocexA deletion increased pleuromutilin production (38.7 ± 2.3 mg/L) in the idhA deletion strain overexpressing AoaclA and AoaclB but not in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3b), indicating that the combination of these modifications was effective for terpene production. Additionally, extracellular/intracellular mevalonate accumulated in this quadruple-modified strain (Fig. 3c), suggesting that these genetic modifications enhanced the introduction of substrates into the MVA pathway. These results suggest that enhancement of the pathway supplying acetyl-CoA from citrate is an effective strategy for heterologous pleuromutilin production in A. oryzae.

Fig. 3. Effects of metabolic engineering for increased cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA via citrate on pleuromutilin production.

a The pathway to synthesise cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA from pyruvate via citrate with the enzymes catalysing each reaction and a citrate exporter CEX. The processes with the proteins indicated as blue box were blocked by gene deletion, and that with the protein indicated as orange box were potentiated by gene overexpression. Pleuromutilin production (b) and extracellular/intracellular mevalonate amount (c) in the indicated strains. The strains were cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30 °C for 5 days. Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) with dot plot indicating each data of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test compared to the WT strain.

Effects of the potentiated MVA pathway on heterologous pleuromutilin production

Overexpression of genes involved in the MVA pathway results in enhanced production of a precursor for the sesquiterpene lactone artemisinin in S. cerevisiae10. In addition, overexpression of the eight genes in this pathway was effective for mangicol J production in A. oryzae (Fig. 4a)27. Therefore, to investigate the effect of MVA pathway modifications on pleuromutilin production, we first focused on the genes encoding HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR), which catalyses a rate-limiting step in sterol biosynthesis36. In S. cerevisiae, the truncation of HMGR Hmg1 (tHmg1) releases it from negative feedback regulation, and the overexpression of tHMG1 results in the accumulation of squalene37. This strategy has been used for heterologous production of various terpenes and terpenoids in yeast4,9. Among the two HMGR found in A. oryzae, AO090103000311 had a structure similar to that of Hmg1, which has an HMG-CoA reductase domain, an HMG-CoA reductase N-terminal domain, a sterol-sensing domain, and several transmembrane domains, and was designated as AoHmg1 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Based on sequence homology between Hmg1 and AoHmg1, truncated AoHmg1 (tAoHmg1) was designed (Supplementary Fig. 8b). In contrast to AoHmg1, AO090120000217 (AO217) has an HMG-CoA reductase domain and only two transmembrane domains (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Strains overexpressing AoHmg1, truncated AoHmg1 (tAoHmg1), and AO217 from Ptef1 at their native loci were constructed (Supplementary Fig. 8c–e), and their pleuromutilin production levels were measured. Although Aohmg1 overexpression did not affect pleuromutilin production, AO217 overexpression led to increased production, and tAohmg1 overexpression tended to increase pleuromutilin production (Supplementary Fig. 8f). These results suggest that stimulation of HMGR activity is effective in increasing terpene production in A. oryzae and S. cerevisiae. Considering these results, further activation of HMGRs and their combination with the modification of upstream metabolic pathways is hypothesised to result in further enhanced production. Therefore, we constructed a strain named MEwnpPL001, in which tAoHmg1 and AO217 were overexpressed and the adh gene was replaced with an additional AO217 overexpression cassette with Ptef1 (Supplementary Fig. 8g). When the pleuromutilin production level was measured, increase of pleuromutilin production was detected in this strain (Fig. 4c; Strain WT vs. Strain 1), indicating that combination of genetic modifications in multiple metabolic pathways is effective for heterologous pleuromutilin production.

Fig. 4. Effects of metabolic engineering of the MVA pathway on pleuromutilin production.

(a) The ethanol fermentation and MVA pathways with the enzymes catalysing each reaction. The process with the protein indicated as blue box was blocked by gene deletion, and those with the proteins indicated as orange box were potentiated by gene overexpression. To activate HMGRs, their truncated variants were also overexpressed. b The cartoons indicate the wA loci of the indicated strains. Pleuromutilin production (c) and extracellular/intracellular mevalonate amount (d) in the indicated strains. The numbering of each strain corresponds to the strain numbering in the panel b. The strains were cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30°C for 5 days. “Δ” indicates deletion of adh, “O/E” indicates overexpression of the corresponding genes, and “O/E-tr” indicates overexpression of the truncated HMGR genes. Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) with dot plot indicating each data of three independent experiments. Data are analysed using Tukey’s (c) and Holm’s (d) multiple comparison test, and means sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). The significance of intracellular mevalonate is indicated as a’ and b’ (d).

To further enhance pleuromutilin production, we overexpressed all nine genes that encode enzymes in the MVA pathway (Fig. 4a). To efficiently integrate multiple overexpression cassettes into A. oryzae genome, we developed a method involving stepwise integration into the wA locus. As the wA gene is required for the pigmentation of asexual spores (conidia), this method used the change in conidial colour to select transformants in which the overexpression cassettes were successfully integrated. To use this strategy, we first removed the expression cassettes of pleuromutilin biosynthetic genes ple1–7 from the wA, niaD, and pyrG loci of the MEwnpPL001 strain, yielding the ME001 strain (Supplementary Fig. 9a–c). Subsequently, all these expression cassettes were reintegrated into the wA locus of ME001 strain with single copy, yielding the strain MEwAPL001, which forms white conidia, in which the promoter and 5′ regions of wA were deleted (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). During integration, an artificial target sequence of Cas9 was inserted downstream of the pgkA terminator (TpgkA) for modification of this locus (Supplementary Fig. 11; Blue target sequence). Pleuromutilin non-productivity in ME001 and productivity in MEwAPL001 were confirmed using GC-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Then, overexpression cassettes of the MVA pathway genes were substantially integrated into the wA locus. For overexpression of the MVA pathway genes, promoters, genes of which showed constitutive strong expression, were selected based on the RNA-seq result. Using the artificial target sequence of Cas9 downstream of TpgkA, the overexpression cassettes for erg10 and erg13 were integrated into the wA locus of the MEwAPL001 strain. During this integration, the promoter and 5′ regions of the wA gene were reintegrated together with the native target sequence of Cas9 at the upstream of wA used for the integration of the ple1–7 cassettes (Supplementary Fig. 11; Red target sequence), and the yielded MEwAPL002 strain formed green conidia (Fig. 4b; Strain 2, Supplementary Fig. 11; Step 1). Then, using the native target sequence of Cas9 upstream of wA, the overexpression cassettes of truncated AO217 (tAO217) and erg12 were integrated into the wA locus with a partial deletion of the wA gene, yielding the MEwAPL003 strain, which formed white conidia (Fig. 4b; Strain 3, Supplementary Fig. 11; Step 2). In this strain, the artificial target sequence was reintegrated (Supplementary Fig. 11; Blue target sequence). Finally, using the artificial target sequence, the overexpression cassettes of erg8, erg19, idi1, and erg20 were integrated into the wA locus with its promoter and 5′ regions, yielding the MEwAPL004 strain, which formed green conidia (Fig. 4b; Strain 4, Supplementary Fig. 11; Step 3).

The integration of the erg10/erg13 overexpression cassettes increased pleuromutilin production (Fig. 4c; 77.3 ± 6.5 mg/L in Strain 1 vs. 99.9 ± 3.0 mg/L in Strain 2). Although the tAO217/erg12 overexpression cassettes did not increase pleuromutilin production (Fig. 4c; Strain 2 vs. Strain 3), additional erg8/erg19/idi1/erg20 overexpression cassettes further increased its production (Fig. 4c; 97.6 ± 5.1 mg/L in Strain 3 vs. 130.9 ± 5.6 mg/L in Strain 4). Highly accumulated extracellular/intracellular mevalonate was produced by overexpressing erg10, erg13, tAO217, and erg12 (Fig. 4c; Strain 3), suggesting that these modifications potentiated the MVA pathway. In contrast, overexpression of erg8, erg19, idi1, and erg20 decreased extracellular/intracellular mevalonate, while further increasing pleuromutilin production (Fig. 4c; Strain 4). This was probably because the accumulated mevalonate was used for pleuromutilin production by potentiating the downstream part of mevalonate in the MVA pathway. These results indicate that potentiation of the MVA pathway is effective for heterologous pleuromutilin production in A. oryzae.

Combination of metabolic modifications for enhanced heterologous pleuromutilin production

Since we identified several metabolic modifications that enhance pleuromutilin production in the above analyses, the combined effects of these metabolic modifications were investigated. Therefore, genetic modifications, which involved shutoff of ethanol fermentation, enhanced acetyl-CoA production from mitochondrial citrate, and potentiation of the MVA pathway, were introduced into a single strain (Fig. 5a). In this construction, the deletion of idhA was omitted because of its severe effects on growth (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 7c). When AoaclA and AoaclB were overexpressed using the MEwAPL004 strain with adh deletion and potentiated MVA pathway as the parent strain, pleuromutilin production did not increase, whereas extracellular/intracellular mevalonate accumulated (Fig. 5b, c). In contrast, the additional deletion of AocexA increased pleuromutilin production but not mevalonate levels (Fig. 5b, c). These results indicate that the modification targeting acetyl-CoA production from citrate further enhanced pleuromutilin production under adh deletion and MVA pathway potentiation. In addition, the finally obtained strain containing a total of 13 genetic modifications showed 161.6 ± 7.6 mg/L pleuromutilin production, which was an 8.5-fold increase compared to the control strain without any metabolic modifications (Fig. 5b). This indicates that our strategy, involving modifications of multiple metabolic pathways, including ethanol fermentation, acetyl-CoA production from citrate, and the MVA pathway, was highly effective in enhancing pleuromutilin production.

Fig. 5. Effects of accumulated metabolic engineering on pleuromutilin production.

a The pathways involved in pleuromutilin production with the enzymes catalysing each reaction and a citrate exporter CEX. The processes with the proteins indicated as blue box were blocked by gene deletion, and those with the proteins indicated as orange box were potentiated by gene overexpression. To activate HMGRs, their truncated variants were also overexpressed. Pleuromutilin production (b) and extracellular/intracellular mevalonate amount (c) in the indicated strains. The strains were cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30°C for 5 days. “Δ” indicates deletion of adh and AocexA, and “O/E” indicates overexpression of the corresponding genes including overexpression of the truncated HMGR genes. Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) with a dot plot indicating each data of three independent experiments. Data are analysed using Tukey’s multiple comparison test, and means sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). The significance of intracellular mevalonate is indicated as a’ and b’ (c).

Effects of 13 metabolic gene modifications on heterologous aphidicolin and ophiobolin C production

In the above investigations, we generated a pleuromutilin highly-producing MEwAPL007 strain from the wild-type strain RIB40 via the ME001 strain by accumulating a total of 13 metabolic modifications (Fig. 6a). To evaluate the effects of metabolic engineering on the production of other terpenes, we constructed a genome editing plasmid targeting both edges of the ple1–7 expressing region, and the ple1–7 expression cassettes were removed from the strain with 13 genetic modifications, yielding the ME007 strain (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 12a). The loss of pleuromutilin production in this strain was confirmed using GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Next, the expression cassettes of the biosynthetic genes for terpenes, aphidicolin (Supplementary Fig. 13a), and ophiobolin C (Supplementary Fig. 14a) were introduced into this strain. Aphidicolin produced by various fungi, including Phoma betae PS-13, is an inhibitor of DNA polymerase α, thereby blocking cell cycle at early S phase38,39, and ophiobolin C is a compound with phytotoxic, nematocidal, and cytotoxic activities produced by some fungi, including Bipolaris maydis and Aspergillus calidoustus40. Both terpenes have been previously produced using A. oryzae heterologously22,24. As four genes need to be introduced for aphidicolin production (Supplementary Fig. 13b), the expression cassettes of these genes from PamyB were integrated into the niaD locus of the wild-type strain RIB40, the metabolically engineered ME001 strain with three gene modifications, and the ME007 strain with 13 gene modifications (Supplementary Fig. 13c). Because the three genes must be introduced for ophiobolin C production (Supplementary Fig. 14b), the expression cassettes of these genes from PamyB were integrated into the HS201 locus41 of the RIB40, ME001, and ME007 strains (Supplementary Fig. 14c). For ophiobolin C production, the strains were cultivated on the rice medium according to the previous report24. The metabolically modified strains derived from the ME001 and ME007 backgrounds showed increased aphidicolin and ophiobolin C production (Fig. 6b, c). In particular, in the ME007 background, aphidicolin and ophiobolin C production reached 7.34 mg/L aphidicolin and 4.76 mg/kg, respectively. This represents a remarkable increase of 65.6-fold and 28.5-fold, respectively, compared to the control strains without any metabolic modifications (Fig. 6b, c). These results indicate that the metabolically modified strain developed in this study can be used as a versatile highly-producing host for a wide range of terpenes.

Fig. 6. Effects of metabolic engineering on aphidicolin and ophiobolin C production.

Scheme for generating the versatile highly-producing host ME007 for terpene production from the wild-type strain RIB40. The ME001 strain was generated from RIB40 via three modifications, and pleuromutilin biosynthetic genes and ten further modifications were introduced. Finally, pleuromutilin biosynthetic genes were removed, yielding the ME007 strain. Aphidicolin (b) and ophiobolin C (c) production in the indicated strains. “Δ” indicates deletion of adh and AocexA, “O/E” in HMGR indicates overexpression of tAohmg1, AO217, and tAO217, and the other “O/E” indicates overexpression of the corresponding genes. Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) with dot plots indicating the data from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test compared to the control strain.

Discussion

In this study, we elucidated the potential metabolic modifications in multiple metabolic pathways to stimulate the heterologous production of natural products using transcriptome and metabolome analyses in A. oryzae and demonstrated the effectiveness of these modifications on heterologous pleuromutilin production. Moreover, we engineered multiple metabolic pathways using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and generated a versatile host strain for heterologous terpene production containing a total of 13 metabolic modifications.

pdc and adh deletion increased pleuromutilin production in A. oryzae (Fig. 2b). In the deletion strains, ethanol production was completely or largely abolished (Fig. 2c), indicating that ethanol fermentation competed with heterologous terpene production. As pyruvate is consumed during ethanol fermentation, elimination of this pathway may accelerate the utilisation of pyruvate for terpene production. The accumulation of acetyl-CoA by eliminating ethanol fermentation in S. cerevisiae supports this hypothesis32. In contrast to pdc and adh deletions, ald and acs deletions did not affect pleuromutilin production (Fig. 2b), indicating that the PDH bypass hardly contributed to terpene production. Considering the importance of the PHD bypass for terpene production in S. cerevisiae17, the metabolic pathways supplying cytosolic acetyl-CoA are suggested to differ between A. oryzae and S. cerevisiae. In contrast, pleuromutilin production was increased by the stimulation of the acetyl-CoA pathway via citrate (Fig. 3b). However, this pathway has not been investigated for the production of natural products in S. cerevisiae. Nevertheless, considering the growth defects and decreased acetyl-CoA in ACL-deficient strains of A. niger and deletion strains of the mitochondrial citrate transporter genes in A. luchuensis42,43, improved acetyl-CoA availability may result in increased pleuromutilin production. In A. oryzae, the accumulation of mevalonate upon stimulation of acetyl-CoA production from citrate supports this possibility (Fig. 3c). The mevalonate accumulation was probably caused by the limited downstream flux, and therefore, a combined metabolic modification of the MVA pathway was effective for heterologous terpene production. Potentiation of the MVA pathway was effective for the production of pleuromutilin (Fig. 4c). Potentiation of the MVA pathway has been widely used for production of natural products in S. cerevisiae9,10 and mangicol J production in A. oryzae27. When MVA pathway genes were sequentially introduced, mevalonate was highly accumulated by potentiation of the upstream part of the MVA pathway, such as ERG10, ERG13, HMGR, and ERG12 (Fig. 4d). The mevalonate accumulation under overexpression of erg12 encoding mevalonate kinase was unexpected. S. cerevisiae has feedback inhibition of Erg12 by the downstream intermediates, such as DMAPP, GPP, and FPP44. Hence, it is hypothesised that potentiation of the upstream in the MVA pathway increases these intermediates in a limited flux of the downstream pathway, which inhibit ERG12 and thereby accumulate mevalonate. This mevalonate accumulation was largely cancelled by additional potentiation of the downstream part of the MVA pathway (Fig. 4d), supporting the hypothesis. Taken together, these results indicate that the overexpression of all genes is required to fully potentiate the MVA pathway.

In this study, we demonstrated engineering of multiple metabolic pathways, including gene deletion and integration, using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in A. oryzae. Efficient selection of successfully modified strains based on their phenotypic changes and marker-free transformation involved in forced plasmid recycling achieved repetitive modifications26. Although the candidate genes related to phenotypic changes were limited, the sequential integration technique developed in this study uses repeated deletion and recovery of the wA gene involved in conidial pigmentation, which allows unlimited integration of exogenous DNA fragments into the A. oryzae genome with high efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 11). Although metabolic modifications of the MVA pathway have previously been performed for mangicol J production in A. oryzae27, the effectiveness of this strategy for other natural products is unclear. Here, we succeeded in removing the pleuromutilin biosynthetic genes and introduced other biosynthetic genes for aphidicolin and ophiobolin C production (Supplementary Figs. 12–14, and Fig. 6). Through these steps, we demonstrated the versatility of our host strain for heterologous production of various terpenes. Taken together, our CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique is a useful tool for biosynthetic research and production of various natural products using A. oryzae.

In this study, we generated a strain containing 13 metabolic gene modifications involved in ethanol fermentation, acetyl-CoA supply from citrate, and the MVA pathway into a single strain. This strain showed excellent productivities of terpenes, including 161.6 mg/L pleuromutilin, 7.34 mg/L aphidicolin, and 4.76 mg/kg ophiobolin C, marking 8.5-fold, 65.6-fold, and 28.5-fold increase in production levels, respectively, compared to the control strains without any metabolic modifications. As the highest heterologous production of pleuromutilin and aphidicolin reported previously was 74.5 mg/L and 0.33 mg/L, respectively20,22, the strain generated in this study is a versatile and powerful host for terpene production. In many cases, the production levels of natural products from the original source are not sufficient for analyses of their structures, activities, and mechanisms of action3–6; therefore, our host will contribute to biosynthetic and biochemical research of various terpenes. However, further enhancement is required for industrial mass production. Although we integrated a single copy of the biosynthetic genes for terpene production to accurately evaluate the effects of metabolic modifications, stable multiple-copy integration of the biosynthetic genes is expected to further enhance the production of natural products, as previously reported for S. cerevisiae45 and A. oryzae20. In addition, we used strong inducible amyB promoter and constitutive promoters for expression of biosynthetic genes and overexpression of metabolic genes, while optimised expression of these genes would be effective for further enhanced production as performed in E. coli8. Moreover, metabolic modelling46 would be a promising approach for enhanced production if knowledge about metabolic fluxes and related enzymatic kinetics is sufficiently accumulated in A. oryzae. Culture conditions are also an important factor for the production of natural products, and jar fermentation is an effective means to further enhance the production. Curiously, the improved production levels of aphidicolin and ophiobolin C were much lower than that of pleuromutilin (Figs. 5b and 6b, c). However, the amounts of extracellular/intracellular mevalonate were remarkably increased to mostly comparable levels regardless of the produced compounds (Supplementary Fig. 15), supporting that the endogenous metabolic fluxes to mevalonate, possibly to FPP, were similarly enhanced in the modified strains producing the three different compounds. Thus, the low productivities of aphidicolin and ophiobolin C could be attributed to the heterologous biosynthetic processes from FPP to the final products. Reasons for varied productivities of heterologous natural products are not well understood; there might be limiting factors in the processes such as transcription/splicing/translation from heterologous genes, stability/catalytic activity of biosynthetic enzymes, and heterologous metabolic fluxes, which are to be investigated for individual heterologous natural products in future analyses.

To date, no versatile host strains for the heterologous production of natural products have been developed for filamentous fungi. The A. oryzae strain developed in this study is the first versatile host for terpene production. In addition, versatile highly-producing hosts for the heterologous production of other natural products, such as polyketides and NRPs, can be generated, as our genome editing tool can be used for multiple metabolic engineering in any A. oryzae strain. Such versatile highly-producing host strains will allow increased production of various natural products, which accelerates their biosynthetic and biochemical research.

Methods

A. oryzae strains and culture conditions

The A. oryzae strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2. MPY medium (20 g/L maltose, 10 g/L polypeptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L KH2PO4, and 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O [pH 5.5]) was used for production assay of terpenes, RNA-seq, and analyses of metabolites. The rice medium was used to measure ophiobolin C production. To prepare the rice medium, polished rice immersed in distilled water for 1 h was autoclaved at 105 °C for 1 h. For pyrG mutants’ growth, 5 g/L uridine and 2 g/L uracil were added. For niaD mutant growth, M medium (2 g/L NH4Cl, 1 g/L (NH4)SO4, 0.5 g/L KCl, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, and 20 g/L glucose [pH 5.5]) was used.

Transformation of A. oryzae

Transformation using genome editing of A. oryzae was performed according to the previous report26 as follows. Dextrin-peptone-yeast extract (DPY) medium (20 g/L dextrin, 10 g/L polypeptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L KH2PO4, and 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O) or dextrin-peptone (DP) medium (20 g/L dextrin, 10 g/L polypeptone, 5 g/L KH2PO4, and 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O) were used for pre-culture. The mycelia were incubated in the solution I (50 mM maleic acid, 0.6 M (NH4)2SO4, and 0.1% Yatalase (TaKaRa Bio, Ohtsu, Japan) [pH 5.5]) to form protoplasts, and the protoplasts were washed with the solution II (1.2 M sorbitol, 50 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 35 mM NaCl, and 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). The genome editing plasmid and the donor plasmid were added into 200 μL of the protoplast suspension (1.0–5.0 × 106/mL), and the suspension was incubated on ice for 30 min. The suspension was mixed with the solution III (60% polyethylene glycol 4000, 50 mM CaCl2·2H2O, and 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the suspension was mixed with the selection medium. Czapek-dox (CD) medium (3 g/L NaNO3, 2 g/L KCl, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.002 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, and 20 g/L glucose [pH 5.5]) was used to select the transformants. For selection using the pyrithiamine-resistant ptrA marker, 0.1 μg/mL pyrithiamine was added. Dextrin, instead of glucose, was added to the CD medium to remove the genome-edited plasmid containing ptrA from the transformants. To remove the pyrG-bearing editing plasmid, 5 g/L uridine, 2 g/L uracil, and 1 g/L 5-fluoroorotic acid were added to the CD medium. To positively select pyrG and niaD mutants, the selection medium (1.31 g/L leucine, 2 g/L KCl, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.002 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, 20 g/L glucose, 0.015 g/L methionine, 57.6 g/L KClO3, 5 g/L uridine, 2 g/L uracil, and 1 g/L 5-fluoroorotic acid [pH 5.5]) was used.

DNA manipulation

Escherichia coli DH5α strain was used for DNA manipulation. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for plasmid construction was performed using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa Bio) and KOD-Plus-Neo (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). An In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio) was used for plasmid construction. Genomic PCR was performed using the KOD FX Neo (TOYOBO). The primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The plasmid sequences were confirmed using commercial sequencing analysis (Fasmac, Atsugi, Japan).

Plasmid construction

Target sequences of Cas9 were designed based on their specificities and evaluated using CRISPRdirect (https://crispr.dbcls.jp/) and BLAST to avoid off-target effects.

For the separate integration of the ple1–7 expression cassettes into the wA, niaD, and pyrG loci, the genome editing plasmids pRGEgwAup26, pRGEgnDdown26, and ppAsATC9a2gpG26 were used. To construct genome-editing plasmids targeting a single locus that bore ptrA marker, the promoter of the U6 gene of A. oryzae (PU6) attached to the target sequence was amplified from pRGEgwAup using SmaIIF-PU6-F2nd and the corresponding reverse primers and inserted into the SmaI-site of pRGE-gRT626. To construct genome editing plasmids targeting a single locus that bore pyrG marker, PU6 attached to the target sequence was amplified from pRGE-gwAup using SmaIIF-PU6-F2nd and the corresponding reverse primers, and inserted into the SmaI-site of pRpG-gRT647. To construct genome-editing plasmids targeting two or three loci, additional sgRNA expression cassettes were inserted into the Bst1107I and NheI sites of a genome-editing plasmid targeting a single locus.

To construct the donor plasmid to integrate the ple3/4 expression cassettes into the wA locus, the expression cassettes were amplified from pUSA2-ple3/421 using the primers wAupDN-ple34F/R and inserted into the SmaI-site of pwAupDN26, yielding pwA-ple34. To construct the donor plasmid to integrate the ple5–7 expression cassettes into the niaD locus, the expression cassettes were amplified from pTAex3500-ple5/6/721 using the primers nDdownDN-ple567F/R and inserted into the SmaI-site of pnDdownDN26, yielding pnD-ple567. For integration of the pyrG locus, the upstream and downstream flanking regions of pyrG were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets 19IF-pyrGDN-F/pyrGDN-5R2 and pyrGDN-3F2/19IF-pyrGDN-R, respectively, and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19 (TaKaRa Bio), yielding ppyrGDN2. To construct the donor plasmid to integrate the ple1/2 expression cassettes into the pyrG locus, the expression cassettes were amplified from pUSA2-ple1/221 using the primers pyrGDN2-ple12F/R and inserted into the SmaI-site of ppyrGDN2, yielding ppG-ple12. To construct the donor plasmid for the wA locus, including the amyB promoter (PamyB) and the pgkA terminator (TpgkA), PamyB and TpgkA were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the corresponding primer sets and inserted into the SmaI-site of pwAupDN, yielding pwADNA-PamyBTpgkA. To construct the donor plasmid to integrate the ple1–7 expression cassettes into the wA locus, the ple1/2 expression cassettes were amplified from pUSA2-ple1/2 using the primers PamyBIF-Mlu1ple1_F/TpgkAIF-ple2_R and inserted into the SmaI-site of pwADNA-PamyBTpgkA, yielding pwA-ple12. The ple3/4 expression cassettes were amplified from pUSA2-ple3/4 using the primers PamyBIF-Mlu1ple3_F/Ple1IF-BssH2ple4_R and inserted into the MluI-site of pwA-ple12, yielding pwA-ple3412. Finally, the ple5/6/7 expression cassettes were amplified from pTAex3500-ple5/6/7 using the primers Ple4IF-BssH2ple5_F/Ple1IF-BssH2ple7_R and inserted into the BssHII-site of pwA-ple3412, yielding pwA-ple3456712.

To construct donor plasmids for gene deletion, the upstream and downstream flanking regions were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the corresponding primer sets and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19. The plasmid for deletion of the cexA gene was designated as pdcexADN. To construct donor plasmids for gene overexpression at the native locus, its upstream and 5′ regions of ORF and the tef1 promoter (Ptef1)34 were amplified from the RIB40 genomic DNA using the corresponding primer sets and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19. The plasmids for overexpression of aclA and aclB were designated as pPtef1-aclA and pPtef1-aclB, respectively. For AO217 overexpression at the adh locus, the upstream and downstream flanking regions of adh were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA, and the AO217 overexpression cassette was amplified from the genomic DNA of the AO217 overexpressing strain using the corresponding primer sets. These DNA fragments were inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pdadhDN-tefAO217.

To remove the ple1–7 expression cassettes from the wA, niaD, and pyrG loci, DNA fragments, including the deletion parts and their upstream and downstream flanking regions, were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the corresponding primer sets and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19. To remove the ple1–7 expression cassettes from the wA locus, the wA upstream region and TpgkA were amplified from the RIB40 genomic DNA using the corresponding primer sets and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19.

Plasmids containing several promoter/terminator sets were constructed for integration experiments with multiple expression cassettes. The DNA fragments of the amyB terminator (TamyB) and PamyB were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primers 19IF-TamyB_F/FP-TamyBPamyB_R and PamyB_F/19IF-amyB_R, respectively, and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pTamyBPamyB. The DNA fragments TamyB, Ptef1, the tef1 terminator (Ttef1), the pet9 promoter (Ppet9), the pet9 terminator (Tpet9), and the fbaA promoter (PfbaA) were amplified from the RIB40 genomic DNA using primer sets 19IF-TamyB_F/FP-TamyBPtef1_R, Ptef1_F2/R2, Ptef1IF-Ttef1_F/FP-Ttef1Ppet9_R, Ppet9_F/R, Ppet9IF-Tpet9A_F/FP-Tpet9PfbaA_R, and fbaA_F/19IF-fbaA_R, respectively, and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pTamyBtef1pet9fbaA.

For stepwise integration into the wA locus, two donor vectors were constructed. The DNA fragments TpgkA, Ptef1, Ttef1, and upstream and 5′ regions of wA were amplified from the RIB40 genomic DNA using primer sets 19IF-TpgkA_F/Ptef1IF-TpgkA_R, Ptef1_F/R, FPPtef1-Ttef1_F/Ttef1_R, and Ttef1IF-wAup_F/19IF-wADN_R, respectively, and inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pwADNB-Ptef1Ttef1. Ttef1 and PenoA, which were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer set 19IF-Ttef1_F/PenoAIF-Ttef1_R and PenoA_F/R,respectively, and TpgkA with the middle region of wA, which was amplified from pwADNA-PamyBTpgkA using the primers FPPenoA-TpgkA_F/19IF-wADN_R, were inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pwADNC-PenoATpgkA.

To overexpress erg10 and erg13, each ORF was amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets Ptef1IF-erg10_F/Tpet9IF-erg10_R and FPPpgkA-erg13_F/Ttef1-erg13_R, respectively, and the Tpet9 and PpgkA fragments were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets Tpet9_F/FPPpgkASg1-Tpet9 and PpgkA_F/PpgkA_R. These DNA fragments were inserted into the SmaI-site of pwADNB-Ptef1Ttef1, yielding pwAB-erg10erg13. For the overexpression of truncated AO217 (tAO217) and erg12, each ORF was amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets PenoAIF-tAO217_F/Ttef1IF-tAO217_R and FPPpet9-erg12_F/TpgkAIF-erg12_R, respectively. The Ttef1-Ppet9 fragment was amplified from pTamyBtef1pet9fbaA using the primers Ttef1_F/Ppet9_R. These DNA fragments were inserted into the SmaI-site of pwADNC-PenoATpgkA, yielding pwAC-trAO217erg12. To overexpress erg8, erg19, idi1, and erg20, the ORFs of erg8 and erg19 were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets Ptef1If-erg8_F/TfbaAiF-erg8_R and FPPgpdA-erg19_F/Ttef1Mlu1IF-erg19_R, respectively. The TfbaA and PgpdA fragments were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using primer sets TfbaA_F/FPPgpdASg2-TfbaA_R and PgpdA_F/PgpdA_R. These fragments were inserted into the SmaI-site of pwADNB-Ptef1Ttef1, yielding pwAB-erg8erg19. TamyB and the AO803 promoter were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using primer sets erg19IF-TamyB_F/FPPao803Sg1-TamyB_R and Pao803_F/Pao803_R, respectively, and then fused using erg19IF-TamyB_F/Pao803_R. TenoA and PfbaA were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using primer sets TenoA_F/ FPPfbaASg3-TenoA_R and PfbaA_F/PfbaA_R, respectively, and then fused using TenoA_F/PfbaA_R. The ORFs of idi1 and erg20 were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets FPPao803IF-idi1_F/TenoAIF-idi1_R and FPPfbaA-erg20_F/Ttef1IF-erg20_R, respectively. The TamyB-PAO803 fragment, idi1, TenoA-PfbaA fragment, and erg20 were inserted into the MluI-site of pwAB-erg8erg19, yielding pwAB-erg8erg19idi1erg20.

To integrate the gene expression cassettes into the niaD locus, the PamyB-TpgkA fragment was amplified from pwADNA-PamyBTpgkA using the primers nDIF-PamyB_F/pnDIF-TpgkA_R and inserted into the SmaI-site of pnDdownDN, yielding pnDDN-PamyBTpgkA. To construct the donor plasmid for aphidicolin production, the PbGGS-TamyB and PamyB-PbACS-TamyB fragments were first amplified from ppTR1-GGS22 and pTAex3-ACS22 using PamyBIF-GGS_F/Sg1IF-TamyB_R and Sg1-PamyB_F/TpgkAIF-Nhe1Sg2aTamyB_R, respectively, and then inserted into the SmaI-site of pnDDN-PamyBTpgkA, yielding pnD-GGSACS. Next, the PamyB-Pbp450-1-TamyB and PamyB-Pbp450-2-TamyB fragments were amplified from pTAex3-PbP450-122 and pUSA-P450-222 using primer sets Nhe1Sg2a-PamyB_F/Sg3IF-TamyB_R and Sg3-PamyB_F/TpgkAIF-Nhe1TamyB_R, respectively, and then inserted into the NheI-site of pnD-GGSACS, yielding pnD-aphi.

To integrate gene expression cassettes into the HS201 locus, the flanking regions of the target sequence in this locus of Cas9 were amplified from RIB40 genomic DNA using the primer sets 19IF-HS201_F/Sg4HS201_5R and Sg5HS201_3F/19IF-HS201_R, and then inserted into the SmaI-site of pUC19, yielding pHS201DN. In addition, the PamyB-TpgkA fragment amplified from pwADNA-PamyBTpgkA using the primers Sg4IF-PamyB_F/Sg5IF-TpgkA_R was inserted into the SmaI-site of pHS201DN to yield pHS201-PamyBTpgkA. To construct the donor plasmid for ophiobolin C production, the AcOS ORF was first amplified from pTAex3-AcOS24 using the primers PamyBIF-AcOS_F/TpgkASma1IF-AcOS_R and then inserted into the SmaI-site of pHS201-PamyBTpgkA, yielding pHS201-AcOS. Next, the TamyB-PamyB fragment amplified from pTamyBPamyB using the primers TamyB_F/PamyB_R and oblDBm-TamyB-PamyB-oblBBm fragments amplified from pUSA2-oblBD24 using the primers PamyBIF-oblDbm_F/TpgkAIF-oblBbm_R were inserted into the SmaI-site of pHS201-AcOS, yielding pHS201-ophi.

Extraction of total RNA and RNA-seq analysis

The total RNA was extracted from mycelia of RIB40 strain cultured in MPY medium at 30°C through days 1–5 according to the previous report48 as follows. Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of mycelia, which were homogenised with a multi-bead shocker (Yasui Kikai, Osaka, Japan), using ISOGEN (NIPPON GENE, Tokyo, Japan) and purified using RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) following their instructions. DNA library preparation and sequencing using a NovaSeq 6000 were performed commercially by Novogene (Beijing, China). The sequence reads were trimmed and filtered by fastp 0.20.149, and the filtered reads were mapped to the genome sequence of A. oryzae RIB40 strain using HISAT2 v2.2.150. The output SAM files were converted into BAM files and indexed using Samtools 1.14 (https://www.htslib.org/). The number of reads mapped to each gene was counted using featureCounts v2.0.151, and the transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) was calculated. Based on the means of the TPM of three independent experiments, log2(TPM + 1) values were calculated, and a heatmap was constructed using these values.

Metabolome analysis

The RIB40 strain was cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30 °C through days 1, 3, and 5, and 50 mg mycelia were washed with distilled water and mixed with 1.6 mL methanol and internal standard. These samples were commercially analysed by Human Metabolome Technologies (HMT; Tsuruoka, Japan). The samples were mixed with 1.6 mL chloroform and 0.64 ml Milli-Q water and centrifuged at 2300 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The water layer was filtered using a 5 kDa cutoff filter (Ultrafree MC PLHCC, HMT) with 9,100 × g at 4 °C for 120 min, evaporated, and then dissolved with 25 μL Milli-Q water. The prepared samples were analysed using CE-TOFMS. Relative peak areas of metabolites to that of the internal standard were calculated using the result from the single experiment, and the values were normalised to those obtained at the first day of culture.

Extraction and measurement of metabolites

To extract metabolites, 2 × 107 conidia were inoculated into 20 mL MPY liquid medium and cultured at 30 °C. Mycelia and culture supernatant were separately collected with a filter. To prepare the extract from the culture supernatant, 5 mL culture supernatant was mixed with 3 mL ethyl acetate and incubated at room temperature overnight. To purify the organic layer, 200 μL organic layer with internal standard (methyl stearate; 136-07971, FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was treated with silica gel and eluted with 600 μL ethyl acetate. To detect pleuromutilin, samples were analysed using GCMS-QP2010 SE (SHIMAZDU, Kyoto, Japan) with a DB-1 MS capillary column (0.32 mm × 30 m, 0.25 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.). Each sample was injected onto the column at 80 °C in the splitless mode. After isothermal hold at 100 °C for 3 min, the column temperature was increased by 14 °C/min to 268 °C. The flow rate of the helium carrier gas was 0.66 mL/min. The specific peak with high intensity of pleuromutilin at m/z 163, which was previously used for its detection21, was used for its quantification. The pleuromutilin concentration was quantified using a linear standard curve based on the relative peak area of pleuromutilin at m/z 163 to that of the internal standard at m/z 74. A standard curve was generated using pleuromutilin.

To detect aphidicolin, 5 mL culture supernatant mixed with 3 mL ethyl acetate was incubated at room temperature overnight, and 2 mL of the organic layer was evaporated and then resuspended with 200 μL organic solvent (chloroform: methanol = 9:1) before column purification. The samples were analysed using a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) system (SHIMAZDU) with Shim-pack GIS C18 column (4.2 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm particle size; SHIMAZDU) and with an electrospray ionisation (ESI) source in the positive and negative modes. The LC conditions were as follows; 0–19 min, linear gradient of 20–80% CH3CN/0.1% formic acid with H2O/0.1% formic acid and 80% of the same solvent system at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The aphidicolin concentration was quantified using a linear standard curve based on the area of the peak at m/z 285 (Supplementary Fig. 13d), which exhibited high intensity as previously reported22. A standard curve was generated using commercially available aphidicolin (011-09811, FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation).

To detect extracellular mevalonate, 200 µL of culture supernatant was transferred to a 1.5 mL tube and added with 50 µL of 2 M HCl. After mixing by vortex for 15 min, 250 µL of ethyl acetate was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 5 min. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, 200 µL of the upper layer (ethyl acetate layer) was transferred to a 1.5 mL vial (SHIMADZU), diluted with an equal volume of ethyl acetate, and then subjected to GC/MS analysis. To detect intracellular mevalonate, 250 mg of mycelia were homogenised with a multi-bead shocker (Yasui Kikai) and mixed with 500 μL of distilled water. Then, mycelial debris was removed by centrifugation, and the sample was prepared in a manner similar to that for extracellular mevalonate extraction. The samples were analysed using a GCMS-QP2010 SE apparatus equipped with a DB-1 MS capillary column. Each sample was injected into the column at 70°C in the splitless mode. After isothermal hold at 150 °C for 1 min, the column temperature was increased by 30 °C/min to 300°C. The flow rate of the helium carrier gas was 0.6 mL/min. The mevalonate concentration was quantified using a linear standard curve based on the peak area at m/z 43. A standard curve was generated using commercially available mevalonate (M339025-500MG; Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Canada).

To detect maltose, glucose, and ethanol, the culture supernatant was diluted with ultrapure water twice and analysed using an HPLC system (SHIMAZDU) with a ROA-Organic Acid H+ (8%) column (0.32 mm × 300 mm; SHIMAZDU). The mobile phase was 0.025 N H2SO4 with 0.6 mL/min flow rate, and metabolites were detected using a refractive index detector RID-10A (SHIMAZDU). The concentrations were quantified using a linear standard curve based on the peak areas.

Detection of ophiobolin C was performed according to the previous study24 with some modifications. For cultivation on the rice medium 500 μL of conidial suspension (2 × 107 conidia/mL) was mixed with the rice medium prepared from 10 g of polished rice and incubated at 30 °C for 10 days. To prepare the extract, 10 mL chloroform was added to the culture, and 2 mL of the supernatant was evaporated and dissolved with 200 μL chloroform. Samples were analysed using the LC-MS system (SHIMAZDU) with ZORBAX XDB-C18 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm, 5 μm particle size; Agilent Technologies) and with an ESI source in the positive mode. The LC conditions were as follows; 0–15 min, linear gradient of 50–100% CH3CN/0.1% formic acid with H2O/0.1% formic acid; 15–25 min, 100% CH3CN/0.1% formic acid; 25–26 min, 100–50% CH3CN/0.1% formic acid with H2O/0.1% formic acid; and then 26–35 min, 50% of the same solvent system at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The ophiobolin C concentration was quantified using a linear standard curve based on the peak area at m/z 387 (Supplementary Fig. 14d), which was previously used for its detection52. The standard curve was generated using commercially available ophiobolin C (sc-202268, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, U.S.A).

Antibiotic assay of pleuromutilin

Strains were cultured in MPY liquid medium at 30 °C for 5 days, and 5 mL culture supernatant mixed with 3 mL ethyl acetate was incubated at room temperature overnight. One mL of the organic layer was evaporated and then resuspended with 50 μL ethyl acetate, and 5 mL of TSB top agar [BactoTM Tryptic Soy Broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U. S. A.), 0.5% Agar] containing B. subtilis spore was incubated at 70°C for 30 min and layered on a water agar plate. A 6 mm paper disk was put onto the plate, and 10 µL of the sample was spotted onto the disk and cultured overnight at 37°C.

Statistics and reproducibility

The results of three independent experiments and their mean values are shown as dot plots and bar graphs, respectively, and error bars represent the standard deviation (S.D.), as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was tested using a two-sample Student’s t-test in Microsoft Excel, and the results are indicated as *p < 0.05, or **p < 0.01. Multiple comparison tests were performed with Tukey’s or Holm’s methods using software “R” version 4. 0. 3, with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17H05431, 19H04644, 21H02098, 23H04547 (JM), JP19H02891 (HO), JP16H06446, 23H04533, and 24H01741 (AM)).

Author contributions

J.M. conceived and supervised the research. N.S. designed and performed all experiments with support from T.K., A.M., H.O., and J.M., and N.S., T.K., and J.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Katherine Williams and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Koon Ho Wong and Ophelia Bu. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data underlying graphs can be obtained in Supplementary Data 1. The RNA-seq raw data have been deposited in the DNA DataBank of Japan (DDBJ) with the accession code BioProject PRJDB17490. Plasmids have been deposited at the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene with the ID numbers; pwA-ple34 (227337), pnD-ple567 (227338), ppG-ple12 (227339), pwA-ple3456712 (227340), pdadhDN-tefAO217 (227341), pPtef1-aclA (227342), pPtef1-aclB (227343), pdcexADN (227344), pwAB-erg8erg19idi1erg20 (227345), pwAB-erg10erg13 (227346), pwAC-trAO217erg12 (227347), pnD-aphi (227348), pHS201-ophi (227349).

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06958-0.

References

- 1.Atanasov, A. G. et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol. Avd.33, 1582–1614 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod.83, 770–803 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navale, G. R., Dharne, M. S. & Shinde, S. S. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology for isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.105, 457–475 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang, Z., Zhi, H., Fang, Z. & Zhang, P. Genetic engineering of yeast, filamentous fungi and bacteria for terpene production and applications in food industry. Food Res. Int.147, 110487 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu, J., Wang, X., Dai, G., Zhang, Y. & Bian, X. Microbial chassis engineering drives heterologous production of complex secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv.59, 107966 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu, X., Liu, Y., Du, G., Ledesma-Amaro, R. & Liu, L. Microbial chassis development for natural product biosynthesis. Trends Biotechnol.38, 779–796 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milke, L. & Marienhagen, J. Engineering intracellular malonyl-CoA availability in microbial hosts and its impact on polyketide and fatty acid synthesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.104, 6057–6065 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajikumar, P. K. et al. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science330, 70–74 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai, Z. et al. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of ginsenosides. Metab. Eng.20, 146–156 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ro, D. K. et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature440, 940–943 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrendorff, J. B., Vickers, C. E., Chrysanthopoulos, P. & Nielsen, L. K. 2, 2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl as a screening tool for recombinant monoterpene biosynthesis. Microb. Cell Fact.12, 76 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, J., Zhang, W., Du, G., Chen, J. & Zhou, J. Overproduction of geraniol by enhanced precursor supply in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biotechnol.168, 446–451 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tippmann, S., Ferreira, R., Siewers, V., Nielsen, J. & Chen, Y. Effects of acetoacetyl-CoA synthase expression on production of farnesene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol.44, 911–922 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asadollahi, M. A., Maury, J., Schalk, M., Clark, A. & Nielsen, J. Enhancement of farnesyl diphosphate pool as direct precursor of sesquiterpenes through metabolic engineering of the mevalonate pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng.106, 86–96 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou, P. et al. Alleviation of metabolic bottleneck by combinatorial engineering enhanced astaxanthin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzym. Microb. Technol.100, 28–36 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López, J. et al. Production of β-ionone by combined expression of carotenogenic and plant CCD1 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Fact.14, 84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, Y., Daviet, L., Schalk, M., Siewers, V. & Nielsen, J. Establishing a platform cell factory through engineering of yeast acetyl-CoA metabolism. Metab. Eng.15, 48–54 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oikawa, H. Reconstitution of biosynthetic machinery of fungal natural products in heterologous hosts. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.84, 433–444 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang, Y. M., Lin, T. S. & Wang, C. C. C. Total heterologous biosynthesis of fungal natural products in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Nat. Prod.85, 2484–2518 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey, A. M. et al. Identification and manipulation of the pleuromutilin gene cluster from Clitopilus passeckerianus for increased rapid antibiotic production. Sci. Rep.6, 25202 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamane, M. et al. Biosynthetic machinery of diterpene pleuromutilin isolated from Basidiomycete Fungi. ChemBioChem18, 2317–2322 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii, R. et al. Total biosynthesis of diterpene aphidicolin, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase α: Heterologous expression of four biosynthetic genes in Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.75, 1813–1817 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiba, R., Minami, A., Gomi, K. & Oikawa, H. Identification of ophiobolin F synthase by a genome mining approach: a sesterterpene synthase from Aspergillus clavatus. Org. Lett.15, 594–597 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narita, K. et al. Multiple oxidative modifications in the ophiobolin biosynthesis: P450 oxidations found in genome mining. Org. Lett.18, 1980–1983 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katayama, T. et al. Development of a genome editing technique using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the industrial filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Biotechnol. Lett.38, 637–642 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katayama, T. et al. Forced recycling of an AMA1-based genome-editing plasmid allows for efficient multiple gene deletion/integration in the industrial filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.85, e01896–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan, Y. et al. Efficient exploration of terpenoid biosynthetic gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Nat. Catal.5, 277–287 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidovich, C. et al. Induced-fit tightens pleuromutilins binding to ribosomes and remote interactions enable their selectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA.104, 4291–4296 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown, P. & Dawson, M. J. A perspective on the next generation of antibacterial agents derived by manipulation of natural products. Prog. Med. Chem.54, 135–184 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paramasivan, K. & Mutturi, S. Progress in terpene synthesis strategies through engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol.37, 974–989 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otterstedt, K. et al. Switching the mode of metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Rep.5, 532–537 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian, J., Si, T., Nair, N. U. & Zhao, H. Design and construction of acetyl-CoA overproducing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Metab. Eng.24, 139–149 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hynes, M. J. & Murray, S. L. ATP-citrate lyase is required for production of cytosolic acetyl coenzyme A and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell9, 1039–1048 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamoto, N. et al. Utilization of the TEF1-α gene (TEF1) promoter for expression of polygalacturonase genes, pgaA and pgaB, in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.50, 85–92 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura, E. et al. Citrate exporter enhances both extracellular and intracellular citric acid accumulation in the koji fungi Aspergillus luchuensis mut. kawachii and Aspergillus oryzae. J. Biosci. Bioeng.131, 68–76 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burg, J. S. & Espenshade, P. J. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase in mammals and yeast. Prog. Lipid Res.50, 403–410 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polakowski, T., Stahl, U. & Lang, C. Overexpression of a cytosolic hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase leads to squalene accumulation in yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.49, 66–71 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikegami, S. et al. Aphidicolin prevents mitotic cell division by interfering with the activity of DNA polymerase-α. Nature275, 458–460 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ichihara, A. et al. 3-Deoxyaphidicolin and aphidicolin analogues as phytotoxins from Phoma betae. Agric. Biol. Chem.48, 1687–1689 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian, W., Deng, Z. & Hong, K. The biological activities of sesterterpenoid-type ophiobolins. Mar. Drugs15, 229 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, C. et al. Efficient reconstitution of Basidiomycota diterpene erinacine gene cluster in Ascomycota host Aspergillus oryzae based on genomic DNA sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 15519–15523 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, H., He, X., Geng, H. & Liu, H. Physiological characterization of ATP-citrate lyase in Aspergillus niger. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol.41, 721–731 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kadooka, C. et al. Mitochondrial citrate transporters CtpA and YhmA are required for extracellular citric acid accumulation and contribute to cytosolic acetyl coenzyme A generation in Aspergillus luchuensis mut. kawachii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.85, e03136–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Primak, Y. A. et al. Characterization of a feedback-resistant mevalonate kinase from the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.77, 7772–7778 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng, B. et al. An in vivo gene amplification system for high level expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Commun.13, 2895 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu, H. et al. Multiscale models quantifying yeast physiology: towards a whole-cell model. Trends Biotechnol.40, 291–305 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu, C. et al. Mitochondrial fission dysfunction alleviates heterokaryon incompatibility-triggered cell death in the industrial filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. BioRxiv, 10.1101/2021.12.10.472196.

- 48.Katayama et al. Novel Fus3- and Ste12-interacting protein FsiA activates cell fusion-related genes in both Ste12-dependent and -independent manners in Ascomycete filamentous fungi. Mol. Microbiol.115, 723–738 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods12, 357–360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan, J. et al. The biosynthesis and transport of ophiobolins in Aspergillus ustus 094102. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 1903 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data underlying graphs can be obtained in Supplementary Data 1. The RNA-seq raw data have been deposited in the DNA DataBank of Japan (DDBJ) with the accession code BioProject PRJDB17490. Plasmids have been deposited at the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene with the ID numbers; pwA-ple34 (227337), pnD-ple567 (227338), ppG-ple12 (227339), pwA-ple3456712 (227340), pdadhDN-tefAO217 (227341), pPtef1-aclA (227342), pPtef1-aclB (227343), pdcexADN (227344), pwAB-erg8erg19idi1erg20 (227345), pwAB-erg10erg13 (227346), pwAC-trAO217erg12 (227347), pnD-aphi (227348), pHS201-ophi (227349).