Abstract

Genomic screened homeobox 1 (Gsx1 or Gsh1) is a neurogenic transcription factor required for the generation of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons during spinal cord development. In the adult, lentivirus (LV) mediated Gsx1 expression promotes neural regeneration and functional locomotor recovery in a mouse model of lateral hemisection spinal cord injury (SCI). The LV delivery method is clinically unsafe due to insertional mutations to the host DNA. In addition, the most common clinical case of SCI is contusion/compression. In this study, we identify that adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (AAV6) preferentially infects neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs) in the injured spinal cord. Using a rat model of contusion SCI, we demonstrate that AAV6 mediated Gsx1 expression promotes neurogenesis, increases the number of neuroblasts/immature neurons, restores excitatory/inhibitory neuron balance and serotonergic neuronal activity through the lesion core, and promotes locomotor functional recovery. Our findings support that AAV6 preferentially targets NSPCs for gene delivery and confirmed Gsx1 efficacy in clinically relevant rat model of contusion SCI.

Keywords: Genomic screened homeobox 1 (Gsh1 or Gsx1), Gene therapy, Neural stem/progenitor cell, Neurogenesis, Neural regeneration, Traumatic spinal cord injury

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a complex tissue injury resulting in degenerating damage to the central nervous system (CNS) and is characterized by a low quality of life. The clinical pathophysiology of SCI is heterogenous and greatly affected by the extent, location, and type of injury [1]. Immediately following initial mechanical damage, a cascade of cellular/molecular effects occurs, resulting in localization of inflammatory cells to the injury site [2], mass cell apoptosis [3], release of reactive oxygen species [4], and glutamate-induced excitotoxicity [5]. Demyelination and neuronal degeneration occur in the mechanically damaged and adjacent spared tissue. The resulting microenvironment is unfavorable for cellular growth and isolated by the glial scar border over a period of weeks.

Neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs), characterized by multipotency and self-renewal, are highly diverse with various established markers, e.g., Nestin, Sox2, Foxj1, and NG2 [[6], [7], [8]]. These unique cells produce newborn neurons and glia in the neurogenic niches of the developing and adult CNS [9]. In the normal adult spinal cord, NSPCs are quiescent; they become activated and proliferate to contribute glial fated progeny to the glial scar after injury [10]. NSPCs are a major target for regenerative therapy to treat SCI (see reviews in Refs. [7,11]).

The genomic screened homeobox 1 (Gsx1 or Gsh1) is a neurogenic transcription factor known to regulate the formation of dorsal excitatory and inhibitory spinal cord interneurons during embryonic development [12,13]. In the adult, the role of inhibitory dorsal interneuron population four is to modulate our perception of pain and itch sensation, whereas excitatory dorsal population five modulates our perception of pain, itch, heat, and touch sensation [14]. Interestingly, the mature dorsal populations formed via Gsx1 expression in the embryo do not contribute to circuits involved in motor function. However, our recent study demonstrated that lentivirus (LV) mediated Gsx1 (LV-Gsx1) expression largely affects NSPCs, reduces reactive gliosis and glial scar formation, promotes serotonin (5-HT) neuronal activity and locomotor functional recovery in a mouse model of lateral hemisection SCI [15]. In addition, virus mediated Sox2 expression directly converts GFAP+ astrocytes [16] and NG2+ polydendrocytes [17] into neurons, and results in functional improvement in a mouse model of hemisection SCI.

While it has been demonstrated that Gsx1, Sox2, and other neurogenic factors promote regeneration after SCI [[16], [17], [18], [19]], the LV gene delivery method is not ideal. As a retrovirus, the LV incorporates its genome into the host DNA and is prone to random insertional mutations [20]. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a clinically safe alternative as its mechanism of action does not require incorporation of its genome into the host DNA, and thus reduces risk of harm to the patient [21]. A cell specific promoter, e.g., GFAP for astrocytes and NG2 for polydendrocytes, or a particular AAV serotype can be used to target various cell populations in the spinal cord.

The goal of the Gsx1 therapeutic is to target and engineer endogenous NSPCs to produce functional interneurons instead of glia to restore signal transmission through the injury site. In this study, we first identify that AAV serotype 6 (AAV6) is a highly effective gene delivery system to target NSPCs in the injured spinal cord. We then examine the efficacy of both AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1 in a clinically relevant rat model of contusion SCI. Overall, our study advances the development of clinically relevant AAV6-based gene therapy for NSPC targeting and provides insight into the cellular/molecular and behavioral effects of Gsx1 reactivation in adult rat models of SCI.

Results

AAV6 preferentially transduces NSPCs in the injured rat spinal cord

Since LV bears biosafety concerns, e.g., insertional mutagenesis [[22], [23], [24]], we performed a literature search for AAV serotypes with NSPC affinity. Initially, we identified three potential serotypes: AAV5 [25,26], AAV6 [25,27], and AAVrh10 [28,29] based on their known tropism. We then evaluated which AAV serotype transduces NSPCs with the highest efficiency. We screened the three selected candidates in a rat model of lateral hemisection SCI. Viral constructs with a ubiquitous cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and GFP reporter, i.e., AAV5-GFP, AAV6-GFP, and AAVrh10-GFP, were selected and tested. LV-GFP served as a positive control. A total number of 12 male Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into the following groups: SCI + AAV5-GFP, SCI + AAV6-GFP, SCI + AAVrh10-GFP, SCI + LV-GFP. A total of 3.0 μl virus was injected at three depths into the spinal cord at 500 nl/min: 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, at approximately 1.0 mm rostral/caudal to the injury site immediately following SCI (supplemental Fig. S1). Animals were sacrificed and spinal cords were harvested in the acute stage at 4 days post-injury (4 dpi) (supplemental Fig. S1).

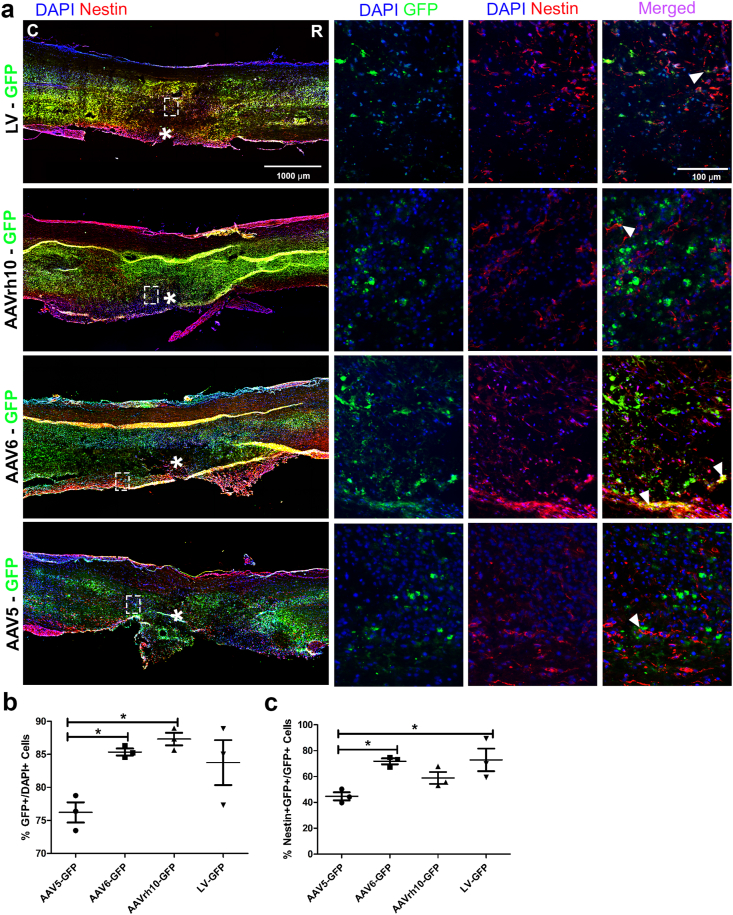

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed to quantify the expression of well-established NSPC marker Nestin. The efficiency of viral transduction was determined by the percentage of virally infected cells (GFP+) among the total number of cells (DAPI+) at the viral injection site adjacent to the lesion core (Fig. 1). Transduction efficiency in NSPCs was defined as the percentage of GFP and Nestin co-labeled cells (GFP+/Nestin+) among virally infected cells (GFP+). We observed that the GFP+ cells were concentrated at the injection sites and evenly distributed throughout the injury, approximately 1 mm rostral/caudal to the lesion core (supplemental Fig. S2). The Nestin+ cells were concentrated near the lesion site and did not distinctly pass through the ependymal layer of the central canal (CC) into the uninjured side. However, some NSPC activation was observed on the uninjured lateral side closest to the hemisection injury (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

AAV serotype 6 targets NSPCs in acute SCI. (a) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green) and NSPCs (Nestin, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 4 dpi. (b) Percentage of GFP+ cells over DAPI+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (c) Percentage of GFP+Nestin+ cells over total GFP+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, AAV5-GFP, AAV6-GFP, and AAVrh10-GFP versus the control group (LV-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Cell count analysis showed the percentage of AAV6-GFP+ cells (85.36% ± 0.52; n = 3) and AAVrh10-GFP+ cells (87.32% ± 0.95; n = 3) among the total number of cells (DAPI+) in the counted area were significantly higher than that of the AAV5-GFP group (76.20% ± 1.53; n = 3), compared with the percentage of LV-GFP (83.75% ± 3.40; n = 3) control group. This indicates that the serotypes of AAV6 and AAVrh10 have a higher transduction efficiency than AAV5 (Fig. 1b). The percentage of GFP+/Nestin+ cells among virally infected cells (GFP+) in AAV6-GFP (71.75% ± 2.28; n = 3) and AAVrh10-GFP (58.84% ± 4.59; n = 3) were significantly higher than that of AAV5-GFP group (44.71% ± 3.07; n = 3), compared with LV-GFP (72.89% ± 8.75; n = 3) control (Fig. 1c). While no significant difference in transduced NSPCs was found between AAV6-GFP and AAVrh10-GFP, a trend and greater significant difference with AAV5-GFP infected NSPCs (Fig. 1b) indicates that AAV6 serotype has the highest transduction efficiency for NSPCs. The high transduction efficiency and NSPC specific transduction rates reflect the infected cells at the injection sites, directly overlapping with a region of high NSPC activation after SCI. Based on our findings, the NSPC specific AAV6 was selected to further test the efficacy of Gsx1 for SCI treatment in a rat model of contusion SCI.

AAV6-Gsx1 promotes NSPC activation, proliferation, and neurogenesis in the acute SCI

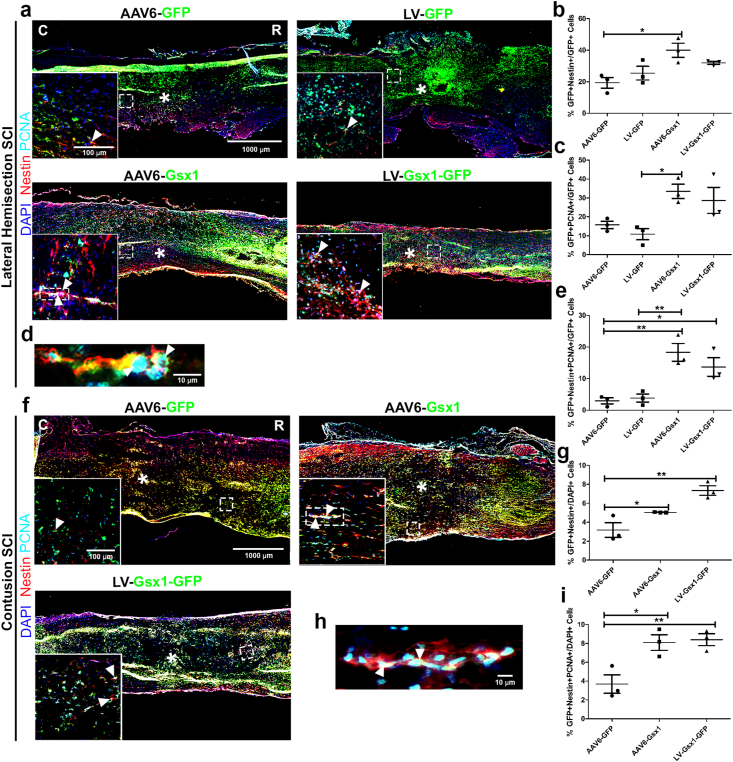

We next tested the efficacy of AAV6-Gsx1 to activate NSPCs and induce cell proliferation in the following groups: SCI + AAV6-GFP, SCI + AAV6-Gsx1, SCI + LV-GFP, SCI + LV-Gsx1-GFP in a rat model of lateral hemisection SCI (Fig. 2). We sacrificed animals and harvested spinal cords at 4 dpi. IHC analysis was used to quantify the expression of Nestin (NSPCs) and PCNA (proliferating cells). We found co-labeled Nestin+/GFP+ cells throughout and immediately adjacent to the lateral hemisection injury site and expressed this value among virally infected cells (GFP+) to represent the virus induced NSPC activation (Fig. 2a). We also expressed this value as a percentage of total cells (DAPI+) and raw cell values (supplemental Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Gsx1 promotes NSPC activation, proliferation, and neurogenesis in acute hemisection and contusion SCI. Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green), NSPCs (Nestin, red), and proliferation (PCNA, cyan) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 4 dpi. (b) Percentage of GFP+Nestin+ cells over total GFP+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (c) Percentage of GFP+PCNA+ cells over total GFP+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (d) Percentage of Nestin+PCNA+GFP+ cells over total GFP+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (e) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally infected (Gsx1+) proliferating (PCNA+) neural stem cells (Nestin+) in the injured spinal cord with AAV6-Gsx1 treatment. (f) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (in green), NSPCs (Nestin, red), and proliferation (PCNA, cyan) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 4 dpi. (g) Percentage of GFP+Nestin+ cells over total DAPI+ cells at injection sites adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (h) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally infected (Gsx1+) proliferating (PCNA+) neural stem cells (Nestin+) in the injured spinal cord with AAV6-Gsx1 treatment. (i) Percentage of Nestin+PCNA+GFP+ cells over total DAPI+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1 induce neurogenesis in the injured spinal cord. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP versus the control groups (AAV6-GFP, LV-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Cell count analysis showed that AAV6-Gsx1 (39.98% ± 4.45; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (31.96% ± 0.96; n = 3) significantly increased Nestin+ NSPC activation in comparison with controls: LV-GFP (25.45% ± 4.32; n = 3) and AAV6-GFP (19.36% ± 3.36; n = 3) (Fig. 2b). We also found many co-labeled PCNA+/GFP+ cells throughout the tissue surrounding the injury and injection sites (Fig. 2a) and expressed this value among virally infected cells (GFP+) to quantify virus-induced proliferation. We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (33.49% ± 3.79; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (28.71% ± 6.91; n = 3) significantly increased cell proliferation in comparison with controls LV-GFP (10.86% ± 2.94; n = 3) and AAV6-GFP (15.74% ± 1.97; n = 3) (Fig. 2c). We further investigated Gsx1-induced neurogenesis by quantifying cells with the co-labeling of markers: virally infected (GFP+) proliferating (PCNA+) NSPCs (Nestin+). We observed many Gsx1-induced co-labeled neurogenesis positive cells between the 1 mm rostral/caudal of the injection sites and throughout the injury (Fig. 2a). AAV6-Gsx1 (18.30% ± 2.80; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (13.66% ± 2.93; n = 3) induced neurogenesis in comparison with controls LV-GFP (3.84% ± 1.28; n = 3) and AAV6-GFP (2.97% ± 0.95; n = 3) (Fig. 2d), e.g., AAV6-Gsx1-induced activated proliferating NSPCs (Fig. 2e). We found that Gsx1 promoted NSPC activation and proliferation, and induced neurogenesis in the acute injured spinal cord.

We proceeded to investigate AAV6-Gsx1-induced NSPC activation, proliferation, and neurogenesis in a more clinically relevant rat model of contusion SCI (Fig. 2). Rats were subject to contusion SCI and injected with viral treatments in the following groups: SCI + AAV6-GFP, SCI + AAV6-Gsx1, SCI + LV-Gsx1-GFP. A total of 3.0 μl virus was injected into the spinal cord in four corners of the contusion injury site approximately 1 mm rostral/caudal to the epicenter immediately following SCI (supplemental Fig. S1). The consistency of each contusion injury was confirmed visually during surgery and behaviorally following surgery with complete rear hind limb paralysis below the thoracic injury level. We sacrificed animals and harvested spinal cords at 4 dpi. IHC analysis was used to quantify the expression of Nestin (NSPCs), Sox2 (neural progenitor cells), NG2 (glial progenitor cells/polydendrocytes), and PCNA (proliferating cells). The virally infected GFP+ cell signal was distributed evenly on either side of the contusion injury site, sparse in the lesion core, and consistently dispersed throughout the lesion border (supplemental Fig. S4). The majority of GFP+ cells were found at/near lesion or injection site and appeared to diffuse in the rostral/caudal directions. The Nestin signal was prominent in the lesion border and spread rostral/caudal neural tissue. Nestin+/GFP+ and PCNA+/GFP+ co-labeled cells among total cells (DAPI+) (Fig. 2f) and virally infected cells (GFP+) (supplemental Fig. S5) were quantified.

Cell count analysis showed that AAV6-Gsx1 (5.04% ± 0.02; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (7.35% ± 0.51; n = 3) increase Nestin+ NSPC activation in comparison to control (3.18% ± 0.77; n = 3) (Fig. 2g). The PCNA signal was less obvious but overlapped with the Nestin throughout the lesion border (Fig. 2f). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (12.01% ± 0.8; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (13.29% ± 2.18; n = 3) did not significantly increase cell proliferation in comparison with the control (7.72% ± 1.41; n = 3), however a positive trend is obvious (supplemental Fig. S5). To investigate neurogenesis in the NSPC populations, we observed and quantified the co-labeling of GFP+, Nestin+, and PCNA+ cells in the injured spinal cord (Fig. 2h). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (8.09% ± 0.83; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (8.38% ± 0.63; n = 3) induce neurogenesis in comparison to control (3.68% ± 0.98; n = 3) (Fig. 2h), e.g., a group of AAV6-Gsx1-induced proliferating NSPCs between the lesion core and caudal injection site (Fig. 2i).

We also observed activation of NG2+ progenitors approximately 1.5 mm rostral/caudal to the injury site, counted co-labeled NG2+/GFP+ cells, and expressed over the GFP+ population (supplemental Fig. S6a). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (8.26% ± 2.07; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (8.10% ± 2.11; n = 3) do not significantly increase NG2+ NSPC activation in comparison to the control (10.01% ± 2.16; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S6c). In addition, we observed Sox2 neural progenitor activation throughout the lesion site and counted co-labeled Sox2+/GFP+ cells and expressed over the GFP+ population (supplemental Fig. S7a). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (48.85% ± 2.61; n = 3) significantly increased Sox2+ NSPC activation in comparison with the control (29.51% ± 1.74; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S7c). However, LV-Gsx1-GFP (37.21% ± 4.73; n = 3) did not significantly activate Sox2 progenitors (supplemental Fig. S7c).

We used Ilastik [30], a non-biased machine learning based bioimage pixel classification analysis software to supplement our cell count analysis and quantified the total molecular marker signal among total cells. We found no difference in transduction efficiency between AAV6-Gsx1 (6.37% ± 0.34; n = 3), LV-Gsx1-GFP (8.02% ± 1.27; n = 3), and control AAV6-GFP (5.18% ± 0.52; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S8a). AAV6-Gsx1 (4.29% ± 0.34; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (4.35% ± 0.24; n = 3) promoted Nestin+ NSPC activation in comparison to control (2.30% ± 0.21; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S9a). AAV6-Gsx1 (1.31% ± 0.08; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (1.28% ± 0.14; n = 3) increased cell proliferation in comparison with the control (0.75%%±0.04; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S9b). We investigated total NG2 progenitor activation and found that AAV6-Gsx1 (12.91% ± 0.57; n = 3) activated NG2 polydendrocytes in comparison with the control (8.88% ± 0.69; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S6c). Interestingly, LV-Gsx1-GFP did not activate NG2 polydendrocytes in comparison with the control (supplemental Fig. S6b). We investigated total Sox2 progenitor activation and found that AAV6-Gsx1 (1.98% ± 0.18; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (2.26% ± 0.21; n = 3) did not activate Sox2+ neural progenitors in comparison with the control (2.23% ± 0.28; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S7b).

Overall, Gsx1 activated various NSPC populations, increased cell proliferation, and induced neurogenesis in both the rat models of lateral hemisection and contusion SCI. The contusion SCI model is representative of the most common clinical injury and is thus used for our Gsx1 therapy efficacy analysis in three major stages: acute, subacute, and chronic.

AAV6-Gsx1 promotes neuroblast and immature neuron formation in the subacute contusion SCI

We next examined the presence of newborn or immature neuron formation at 14 dpi (subacute SCI) initiated by Gsx1-induced neurogenesis at 4 dpi (Supplemental Fig. S1). Rats were subject to contusion SCI and injected with viral treatments in the following three groups: SCI + AAV6-GFP, SCI + AAV6-Gsx1, SCI + LV-Gsx1-GFP. A total of 3.0 μl virus was injected into the spinal cord in four corners of the contusion injury site approximately 1 mm rostral/caudal to the epicenter immediately following SCI. Animals were sacrificed and spinal cords were harvested at 14 dpi.

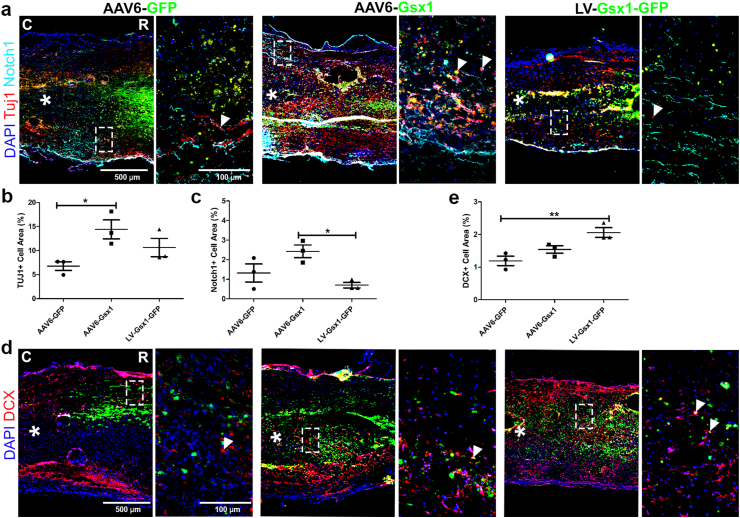

IHC analysis was used to examine the injured spinal cord for established molecular markers DCX (neuroblasts), Tuj1 (immature neurons), and Notch1 (canonical notch activity). The injured area was clear and tissue damage was extensive, spanning 1–2 mm rostral/caudal to the injury epicenter (Supplemental Fig. S10). The GFP+ cell distribution was concentrated at the injection sites and spread approximately 2 mm rostral/caudal to the lesion core. GFP+ cells were clearly present rostral/caudal to the injury epicenter, throughout the injured tissue (Supplemental Fig. S10). We found that LV-Gsx1-GFP (10.97% ± 0.64; n = 3) transduced a higher percentage of cells in comparison to AAV6-Gsx1 (6.53% ± 0.44; n = 3), and control AAV6-GFP (6.67% ± 1.14; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S8b). Tuj1 signal was distributed throughout the injection sites and rostral/caudal to the lesion core (Fig. 3a). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (14.41% ± 1.96; n = 3) significantly increased the percentage of Tuj1+ cells among total cells and LV-Gsx1-GFP (10.62% ± 1.89; n = 3) did not in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (6.76% ± 0.91; n = 3) (Fig. 3b). The canonical notch pathway is upregulated during cell proliferation and NSPC activation in early stages after SCI and decreases during cell differentiation. Here, we used the Notch1 marker to support Gsx1 induced differentiation, indicated by a lack of canonical pathway notch activity at 14 dpi. Our Notch1 signal was evenly distributed throughout the lesion border and spared tissue 0.5 mm rostral/caudal to the injection sites (Fig. 3a). We found that LV-Gsx1-GFP (0.70% ± 0.14; n = 3) significantly reduced the percentage of Notch1+ cells among total cells in comparison with the AAV6-Gsx1 treatment (2.42% ± 0.32; n = 3), supporting neuronal differentiation of LV-mediated Gsx1 activated NSPCs during subacute SCI (Fig. 3c). The DCX signal was only present at the injection sites and dissipated into the lesion core in our control SCI group (Fig. 3d). LV-Gsx1-GFP (4.73% ± 0.33; n = 3) significantly increased the percentage of DCX+ cells over total cells, however AAV6-Gsx1 (3.36% ± 0.12; n = 3) did not in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (2.75 ± 0.16; n = 3) (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Gsx1 promotes neuroblast and immature neuron formation in subacute SCI. (a) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green), immature neurons (Tuj1, red), and canonical notch activity (Notch1, cyan) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 14 dpi. (b) Percent of Tuj1+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (c) Percent of Notch1+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (d) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green) and neuroblasts (DCX, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 14 dpi. (e) Percent of DCX+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP versus the control group (AAV6-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

The low percentages of newborn and immature neurons reflect the quantification area, approximately 2 mm rostral/caudal to and throughout the lesion core, and the extent of tissue damage. Collectively, the Gsx1 gene treatments promoted newborn and immature neuronal formation at 14 dpi following Gsx1-induced activation, proliferation, and neurogenesis of NSPCs at 4 dpi.

AAV6-Gsx1 increases excitatory and reduces inhibitory interneuron populations in the chronic contusion SCI

The synaptic excitatory/inhibitory cell balance in the spinal cord is maintained by interneuron subtypes and required to functionally transmit signal from the brain through the spinal cord [31]. The neurogenic gene Gsx1 drives the formation of dorsal excitatory and inhibitory interneurons during development [32]. We demonstrated that Gsx1-induced newborn and immature neurons were generated in subacute SCI (Fig. 3). We next investigate the role of Gsx1 on the neuronal balance and the identity of differentiated newborn and immature neurons as they develop and integrate into spinal cord neuronal circuitry. Injured animals with viral treatments were sacrificed at 56 dpi (chronic SCI) (Supplemental Fig. S1).

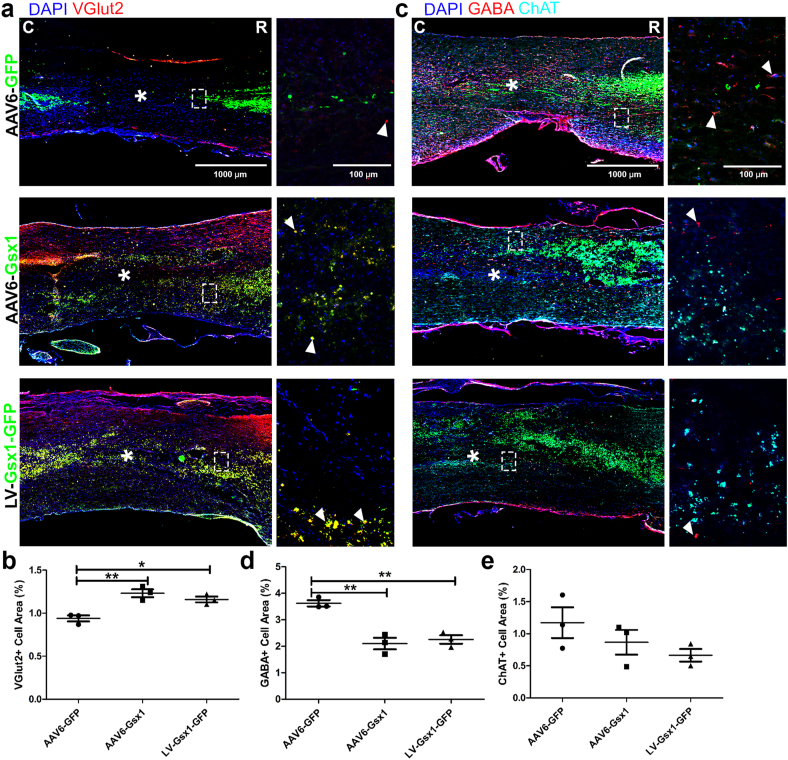

IHC analysis was used to examine the markers of vGlut2 (excitatory), GABA (inhibitory), and ChAT (cholinergic) interneurons. The injured area is clear and spans 2 mm rostral/caudal to the injury epicenter. The GFP+ cell distribution is concentrated at the injection sites, approximately 1–2 mm rostral/caudal to the lesion core, and some GFP+ cells can be found even further, indicating extensive viral spread. GFP+ cells were clearly present rostral/caudal to the injury epicenter, throughout the injured tissue (Supplemental Fig. S11). However, no GFP+ cells were present in the injury epicenter, consistent with our findings at 4 dpi (Supplemental Fig. S4) and 14 dpi (Supplemental Fig. S9). At the injury epicenter, the microenvironment is not favorable for cell growth, thus cells do not usually survive (Supplemental Fig. S11). The vGlut2 signal was distributed throughout our control treatment rostral and slightly caudal to the injured area. Interestingly, our treatments contained many co-labeled GFP+vGlut2+ cells throughout the lesion site spanning 4 mm rostral to caudal, indicated by yellow signal (Fig. 4a). AAV6-Gsx1 (1.23% ± 0.05; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (1.16% ± 0.03; n = 3) increased the percentage of VGlut2+ among total cells in comparison to control AAV6-GFP (0.94% ± 0.04; n = 3) (Fig. 4b). The most prominent GABA signal was present in our control and consistent rostral/caudal to the lesion core, but not present in the lesion core. We found very few if any co-labeled GFP+/GABA+ cells (Fig. 4c). AAV6-Gsx1 (2.1% ± 0.22; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (2.25% ± 0.16; n = 3) reduced the percentage of GABA+ cells among total cells in comparison to control (3.62% ± 0.12; n = 3) (Fig. 4d). The ChAT signal was distributed evenly throughout the rostral spinal cord but interrupted by the lesion site and not present caudal to the lesion (Fig. 4c). Notably, AAV6-Gsx1 (0.87% ± 0.19; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (0.66% ± 0.10; n = 3) did not increase ChAT+ cells in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (1.17% ± 0.24; n = 3) (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Gsx1 increases excitatory and reduces inhibitory interneuron populations in chronic SCI. (a) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green), excitatory interneurons (vGlut2, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 56 dpi. (b) Percent of vGlut2+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (c) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (GFP, green), inhibitory interneurons (GABA, red) and cholinergic interneurons (ChAT, cyan) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 56 dpi. (d) Percent of GABA+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (e) Percent of ChAT+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP versus the control group (AAV6-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Overall, Gsx1 alters the excitatory/inhibitory cell balance in the chronic injured spinal cord by reducing inhibition and increasing excitation at the lesion core. The large number of co-labeled virally infected excitatory interneurons in our AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP treatments suggest that the newborn and immature neurons formed at 14 dpi (Fig. 3) have differentiated into excitatory interneurons at 56 dpi (Fig. 4).

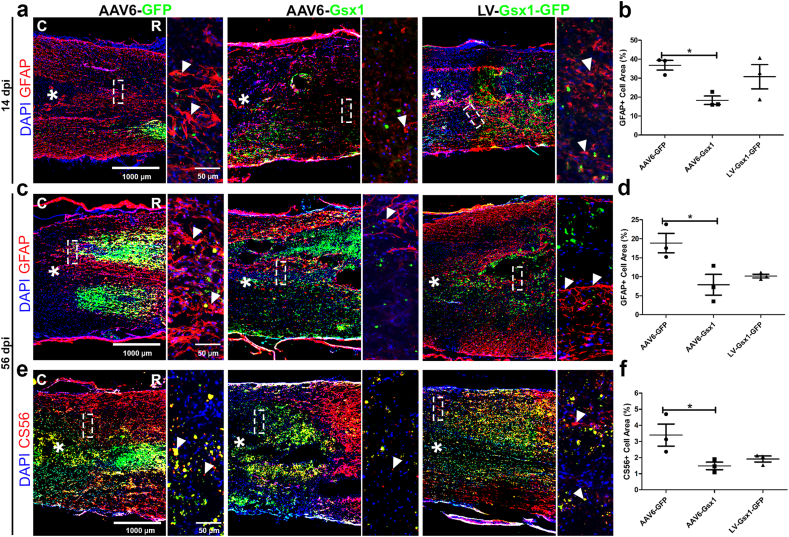

AAV6-Gsx1 reduces reactive gliosis and glial scar formation in the subacute and chronic SCI

The glial scar presents a physical and chemical barrier to regeneration due to a dense astrocyte/fibroblast cell layer, thick secreted ECM, and inhibitory molecules, e.g., CSPGs, collogen [33]. NSPCs play a significant role in scar border formation and contribute glial fate progeny to the astrocyte scar populations [34]. Gsx1 promotes newborn and immature neuronal populations in subacute SCI (Fig. 3). We also identified that these populations differentiate into excitatory and not inhibitory interneurons (Fig. 4).

We next investigated the effect of Gsx1 on reactive gliosis and glial scar formation at 14 dpi and 56 dpi. IHC analysis was used to determine the expression of GFAP (reactive astrocytes) at 14 dpi and CS56 (CSPGs) and GFAP (astrocyte density) in the mature glial scar at 56 dpi. The GFAP signal distribution at 14 dpi was most prominent in the spared neural tissue adjacent to the lesion site, and clearly astrocytes were elongating processes to begin formation of the glial scar (Fig. 5a). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (18.32% ± 2.22; n = 3) reduced reactive gliosis (GFAP/total cells) in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (36.79% ± 2.56; n = 3) at 14 dpi (Fig. 5b). The CS56 signal distribution at 56 dpi was diffuse and most densely occurring at the scar border at the edge of the lesion core but spread 2 mm rostral/caudal to the injury site (Fig. 5c). AAV6-Gsx1 (1.48% ± 0.23; n = 3) reduced CSPG deposition (CS56/total cells) in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (3.40% ± 0.69; n = 3) at 56 dpi (Fig. 5d). The GFAP distribution formed a clear dense border surrounding the injury site with diffuse signal spreading 0.5–1 mm away from the injury scar border (Fig. 5e). AAV6-Gsx1 (7.91% ± 2.73; n = 3) also reduced glial scar border astrocyte density (GFAP/total cells) in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (18.86% ± 2.56; n = 3) at 56 dpi (Fig. 5f). Interestingly, LV-Gsx1-GFP did not significantly reduce reactive gliosis (27.77% ± 3.53; n = 3) at 14 dpi (Fig. 5b), CSPGs (1.91% ± 0.19; n = 3) (Fig. 5d) and astrocyte density (10.18% ± 0.49; n = 3) (Fig. 5f) at 56 dpi compared with the AAV6-GFP control, however displayed a trend toward glial scar reduction. These results suggest that AAV6-Gsx1 reduced astrocyte populations during reactive gliosis and scar border maturation. Thus, our Gsx1-transduced NSPCs produced less glial fated cells (Fig. 5), e.g., astrocyte subtypes, and instead promoted differentiation into neuronal subtypes such as excitatory interneurons (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Gsx1 reduces reactive gliosis and glial scar formation in subacute and chronic SCI. (a) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green) and astrocytes (GFAP, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 14 dpi. (b) Percent of GFAP+ cells adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (c) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of astrocytes (GFAP, red) and gene therapy (Virus, green) in coronal spinal cord sections at 56 dpi. (d) Percent of GFAP+ cells in the glial scar border adjacent to the lesion epicenter. (e) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green) and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPG) (CS56, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections taken at the lesion edge at 56 dpi. (f) Percent of CS56+ signal in the scar border adjacent to the lesion epicenter. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, AAV6-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP versus the control group (AAV6-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Gsx1 promotes 5-HT neuronal activity and locomotor functional recovery in the chronic SCI

The serotonergic (5-HT) neuronal activity is required for the normal transmission of signal in the spinal cord to generate autonomic, motor, and sensory function [35,36]. Locomotor function is directly impacted by 5-HT activity, by modulating spinal network activity required for motor control [37]. After SCI, a loss of 5-HT projections occurs resulting in innervation of motoneurons [[37], [38], [39]]. Thus, the restoration of 5-HT neuronal activity is necessary to promote effective signal transmission through motor circuits in the injured spinal cord and facilitate locomotor recovery. To examine this, we performed IHC to examine 5-HT neuronal activity at 56 dpi. The 5-HT signal was extremely dense and distributed in parallel projections from rostral to caudal. The rostral signal was interrupted by the lesion core and did not continue into caudal spinal cord in our control (Fig. 6a). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (6.54% ± 0.46; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (6.56% ± 0.30; n = 3) increased 5-HT relative intensity in comparison to AAV6-GFP control (4.27% ± 0.56 n = 3) at 56 dpi (Fig. 6b). In our treatments, 5-HT signal continued through the lesion core in two ways: (1) directly through the lesion core with no interruption in the AAV6-Gsx1 group, (2) around the injury epicenter and penetrating through the scar border in the LV-Gsx1-GFP group (Fig. 6a). Thus, Gsx1 promotes restoration of neuronal activity and sprouts neuronal circuits through the lesion core at 56 dpi.

Fig. 6.

Gsx1 induces local network restoration and promotes functional recovery in chronic SCI. (a) Representative immunofluorescence photomicrograph of virally transduced cells (green) and serotonergic neuronal activity (5-HT, red) in longitudinal spinal cord sections at 56 dpi. (b) Relative Intensity of 5-HT+ cells through the lesion epicenter. (c) Impact of AAV6- and LV-mediated Gsx1 treatment on functional recovery after chronic contusion SCI. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, AAV-Gsx1 and LV-Gsx1-GFP versus the control group (AAV6-GFP). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

To examine the effect of Gsx1 therapy on the locomotor functional recovery in injured animals, a blinded analysis of an open field locomotor test was performed with the Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) locomotor scoring scale assessed at 1, 14, 35, and 56 dpi. BBB scores in rats with the injection of AAV6-Gsx1 (13.5 ± 0.31 at 35 dpi and 14 ± 0.21 at 56 dpi; n = 12) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (14.4 ± 0.48 at 35 dpi and 15.2 ± 0.33 at 56 dpi; n = 10) show significantly increased functional locomotor recovery compared with the AAV-GFP control (11.95 ± 0.44 at 35 dpi and 12.6 ± 0.43 at 56 dpi; n = 10) (Fig. 6c and Supplemental Fig. S12).

The BBB locomotor scoring scale is divided into three major recovery stages: early (1–7), intermediate (8-13), and late (14–21) [40,41]. At 35 dpi, Gsx1 rescued coordination of injured animals. Our controls (SCI+AAV6-GFP) remained in the intermediate stage, defined by uncoordinated and inconsistent hind limp plantar stepping, and our treatment groups ascended into the late stage, defined by coordination of front and hind limbs and consistent plantar stepping. At 56 dpi, Gsx1 treated animals continued to improve coordination between front and hind limbs and display consistent plantar stepping, whereas control animals still showed uncoordinated movement and inconsistent plantar stepping in the hind limbs. However, the Gsx1 treatment did not restore bladder functions. Overall, the Gsx1 therapy resulted in the restoration of coordinated function in the hind limbs, consistent weight bearing plantar stepping beginning at 5 weeks, and development of variable coordination between forelimbs and hindlimbs at 8 weeks. In contrast, complete hind limb coordination was never observed in the control animals.

Gsx1 does not change endogenous neuron function after SCI

Neuronal degeneration, demyelination, dysfunction and death occur after SCI due to primary mechanical damage and prolonged inflammatory response in the acute and subacute SCI phases [11]. To rule out any secondary effects of the Gsx1 therapy and account for the established AAV6 neuronal tropism, we investigated Gsx1-mediated changes in neuron populations at 14 dpi. IHC analysis was used to examine the spinal cord for established molecular markers MAP2 or NeuN (mature neurons), Caspase-3 (cell death), 5-HT (serotonergic neuronal activity), Myelin Basic Protein (MBP, myelination), and Synaptophysin (synapses).

Fluorescence imaging of mature neurons was conducted approximately 2 mm away from the lesion core due to high neuronal cell death. The NeuN and MAP2 mature neuron signal was observed 2 mm rostral to the lesion core and not present caudal (Supplemental Figs. S13a and S13c). LV-Gsx1-GFP (10.14% ± 1.24; n = 3) and AAV6-Gsx1 (11.36% ± 0.54; n = 3) did not increase the percentage of NeuN+ cells compared with the AAV6-GFP control (14.41% ± 1.34; n = 3) (Supplemental Fig. S13b). Cell counting analysis showed the percentage of GFP+ and MAP2+ co-labeled cells among virally infected GFP+ cells in AAV6-Gsx1 (84.33% ± 0.25; n = 3) and AAV-GFP groups (85.91% ± 2.39; n = 3) were significantly greater than LV-Gsx1-GFP (67.63% ± 1.83; n = 3) group (Supplemental Fig. S13e). The Caspase-3 (Casp-3) signal was concentrated around the lesion core and dispersed 1 mm rostral/caudal (Supplemental Fig. S13c). We found that AAV6-Gsx1 (51.29% ± 4.08; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (45.09% ± 4.15; n = 3) did not enhance neuron survival as compared to the percentage of GFP+/Casp-3+ co-labeled cells among MAP2+ cells in AAV-GFP (45.32% ± 4.92; n = 3) control group (Supplemental Fig. S13d).

The MBP signal was observed rostral to and throughout the lesion core border (Supplemental Fig. S14a). AAV6-Gsx1 (61.54% ± 4.12; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (48.09% ± 7.77; n = 3) did not increase neuron myelination (GFP+/MBP+ cells among MAP2+ cells) in comparison to AAV-GFP (55.58% ± 3.28; n = 3) control (Supplemental Fig. S14b). The 5-HT signal was distributed clearly rostral to the lesion core and was not present caudal (Supplemental Fig. S14c). AAV6-Gsx1 (17.12% ± 4.16; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (24.87% ± 6.12; n = 3) do not promote serotonergic neuronal activity (GFP+/5-HT+ cells among MAP2+ cells) in comparison to AAV-GFP (21.06% ± 6.14; n = 3) control (Supplemental Fig. S14d). The Synaptophysin signal was distributed rostral and caudal to lesion core (Supplemental Fig. S14e). We also found that AAV6-Gsx1 (30.21% ± 1.29; n = 3) and LV-Gsx1-GFP (33.98% ± 4.09; n = 3) do not promote neuronal synaptogenesis (GFP+/SYN+ cells among MAP2+ cells) in comparison to AAV-GFP (22.52% ± 3.20; n = 3) control (Supplemental Fig. S14f).

Overall, the Gsx1 treatments infected mature neurons but did not enhance neuronal survival, serotonergic neuronal activity, myelination, or synapse formation at 14 dpi. This suggests that Gsx1-induced functional locomotor recovery is due to neurogenesis at 4 dpi, newborn neuron formation at 14 dpi, and regeneration of neurons and neuronal activity at 56 dpi.

Discussion

Our previous study established the efficacy of LV mediated Gsx1 expression to promote functional locomotor recovery in a mouse model of lateral hemisection SCI [15]. In this study, we found that AAV6 infects NSPCs with highest efficiency (Fig. 1). The targeting of endogenous NSPC populations prior to Gsx1 efficacy testing was an important step to move the technology forward for clinical use and maintain or increase efficacy. The LV delivery system results in robust transgene expression, however, is prone to host insertional mutagenesis [20]. Here, we transitioned from the LV to a clinically safe AAV6 delivery system [21] and demonstrated the novel application of AAV6 to target NSPCs in the injured spinal cord.

We used a larger murine rat SCI model, to select for NSPC specific AAV serotypes and evaluate Gsx1 therapeutic efficacy. Major differences between the mouse model of SCI and human clinical SCI include increased regenerative capacity in mice [42], cystic cavity formation in humans [43], and varying inflammatory reactions [44]. However, in both the human and rat SCI pathophysiology, spontaneous regeneration does not occur and fluid filled cystic cavities form [45]. Thus, a rat model of SCI is more representative of clinical human injury and was used for all experiments.

Previously, AAV6 has been shown to target neuronal populations in the CNS, e.g., motoneurons [25], dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons [46,47], and many others [48]. AAV serotypes including AAV1, 2, 5, 6, 9, exhibit a known tropism for microglia and astrocytes [25,49]. We show AAV6 preferentially infects Nestin+ NSPCs in a rat model of acute lateral hemisection SCI. This finding provides a viable delivery system to target NSPCs in the injured spinal cord and can be customized with a cell specific promotor, e.g., NG2 for polydendrocytes [50] and Foxj1 for ependymal cells [51].

Most clinical SCI cases are traumatic and occur due to sports, vehicular accidents, and falls [52]. Thus, the contusion/compression SCI type is most representative of clinical pathophysiology [53]. Our studies demonstrated the efficacy of AAV6- and LV-mediated Gsx1 delivery in both rat models of lateral hemisection and clinically relevant contusion SCI. These findings support the utility of the Gsx1 therapeutic in the heterogeneous clinical setting and provide a delivery method to target NSPCs in the CNS for future therapeutic applications. We also compared commonly used SCI models in the field and provide insight into differences between Gsx1 reactivation in distinct acute SCI types. Promising results in both SCI types serves as evidence that the Gsx1 therapeutic can be used to treat heterogeneous clinical SCI, as the rat models of lateral hemisection and contusion SCI are extremely distinct and contusion injuries occur frequently in the clinic.

The AAV6 mediated Gsx1 expression induces neurogenesis (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), increases the number of neuroblasts/immature neurons (Fig. 3) and excitatory interneurons (Fig. 4), reduces inhibitory interneurons (Fig. 4) and glial scarring (Fig. 5), and restores neuronal activity (Fig. 6) in a rat model of contusion SCI. The Gsx1 gene therapy significantly increases functional locomotor recovery using both the AAV6 and LV delivery system (Fig. 6). The Gsx1 gene therapy results in the restoration of coordinated function in the hind limbs, consistent weight bearing plantar stepping beginning at 5 weeks, and development of variable coordination between forelimbs and hindlimbs. This difference could signify a major change in the quality of life and independence of SCI patients.

In recent years, other neurogenic transcription factors have been used to promote functional locomotor recovery in the injured spinal cord [54]. LV driven Sox2 expression in NG2 polydendrocytes after SCI reduced glial scar formation, promoted local network restoration, and promoted functional locomotor recovery [17]. LV driven NeuroD1 expression directly reprogrammed glial cells into functional neurons and promoted locomotor recovery [16]. A recent study identified a single recovery-organizing population of excitatory interneurons that is necessary and sufficient to regain walking after paralysis in both mice and humans [55]. Consistent with this finding, our Gsx1 therapy promotes excitatory and reduces inhibitory neurons, indicating restoring excitatory/inhibitory ratio may be required to achieve therapeutic effects [56].

Overall, we identify an AAV serotype 6 with the highest affinity for NSPCs in the injured spinal cord and demonstrate the efficacy of the Gsx1 gene therapy in a clinically relevant rat model of contusion SCI. We bring this technology one step closer to human clinical trials and demonstrate the efficacy of both LV- and AAV6- based Gsx1 gene therapy to treat SCI in a rat model using clinically relevant contusion injury, and safe gene delivery method. The next stages of development for the Gsx1 therapy are preclinical examination in larger mammals, e.g., canine, swine, or proceed to human clinical trials. Further mechanistic understanding of Gsx1 reactivation is necessary to consider this for treatment in humans. Limitations of the study include cell/molecular quantification techniques, i.e., IHC, which examines the protein content and distribution. Next-generation sequencing techniques, e.g., single-cell transcriptomic and ChIP-seq analysis, may be the next step to understand the mechanism of Gsx1 gene therapy. It should be noted that protein expression dictates cellular function, therefore this study provides further understanding of Gsx1-induced changes in cellular function after SCI.

Materials and Methods

AAV and LV constructs

Viral constructs: ssAAV5-CMV-eGFP, ssAAV6-CMV-eGFP, ssAAVrh10-CMV-eGFP, ssAAV6-CMV-eGFP, and scAAV6-CMV-Gsx1 were manufactured by Vector Biolabs (Malvern, PA); LV-CMV-eGFP and LV-CMV-Gsx1-SV40-eGFP were manufactured by Applied Biological Materials Inc. (Richmond, BC, Canada).

Rat model of lateral hemisection SCI

Male Sprague Dawley rats (8–12-week-old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Rats were acclimated to the animal facility for 1 week. Rats were anesthetized with 3% Isoflurane and maintained at 2% Isoflurane, then placed on heating pad set to low. Eye lubricant was applied, the surgical site shaved, and sterilized using betadine and 70% ethanol solutions. Analgesics were administered including buprenorphine SR and bupivacaine 0.125%. An incision was made with 10 blade scalpel between cervical and lumbar spinal level. The muscle was dissected using surgical microscissors and remove the dorsal process of thoracic vertebrae 9 (T9) and T10 were removed with bone rongeur to expose the spinal cord. A clamp was applied to the surrounding muscle and a lateral hemisection spinal cord injury was generated via surgical microscissors. 1.5 μL virus treatment was injected in the BSL2 facility at 500 nL/min using 10 μL Hamilton syringe at 1.0 mm rostral/caudal to injury site. A volume of 0.5 μL virus treatment was injected at depths: 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm to ensure total 3.0 μL virus penetrates throughout the injured spinal cord. Adipose tissue from the nape of neck was removed and placed on the exposed T9-10 spinal cord injury site. Two 3-0 sutures were applied to close the muscle and fat adjacent to the laminectomy. Wound clips were applied, and the animal was placed in recovery cage on heating pad and observed until awake and alert. Sterile saline was administered throughout the surgery to ensure animal hydration and cefazolin antibiotic was administered immediately after the surgery. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

Animals were monitored daily for pain, distress, hydration, and surgical site infection. Animal bladders expressed twice daily and administered 1.0 mL bolus saline and cefazolin antibiotic daily for the duration of the study. Bladder infections were treated with enrofloxacin and autophagia was treated with acetaminophen as needed. All procedures were carried out under protocols approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to NIH guidelines. Rutgers Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Protocol 999900038.

Rat model of contusion SCI

Female Sprague Dawley rats (8–12-week-old) were anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5%) before performing a laminectomy to remove the dorsal process of thoracic vertebrae 9 (T9) and expose the spinal cord. The lateral processes of T8 and T10 were clamped and a 200 kDyn injury was induced using the Infinite Horizon Impactor (Precision Systems & Instrumentation). Body temperature was monitored and maintained throughout the surgery using a thermo-regulated heating pad. Following injury, animals received viral treatment: AAV6-GFP, AAV-Gsx1, or LV-Gsx1-GFP via stereotaxic injection into the 4 corners of injury site in the BSL2 facility. After injection, muscle layers were sutured (Ethicon) and skin was closed using wound clips and analgesics, ringer lactate, antibiotics were administered, and returned to the hazard room facility for postoperative care. Animals were housed in temperature-controlled incubators until normothermic and then placed in cages on temperature regulated heating pads in a recovery area. Animals were housed in pairs in standard plastic cages. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was administered twice-a-day for the first three days post-surgery to alleviate pain. Lactated Ringer's solution (10 ml) was provided 1–2 times per day for the first three days post-surgery to prevent dehydration. Gentamycin (5 mg/kg) was administered once daily for the first 7 days post-surgery to prevent infections.

Contusion surgeries, animal care, locomotor and bladder function analysis, and euthanasia were performed by the Burke Neurological Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine (White Plains, NY). All procedures were carried out under protocols approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to NIH guidelines.

Locomotor and bladder function analysis

Recovery of motor function was assessed via BBB locomotor scale method [40]. Prior to recording baseline measurements, rats were allowed to adapt to the open field and pretrained for 10 days. Pre-injury baseline values were collected on the day before SCI surgery (day 0). Following SCI and gene therapy intervention rats' ability to locomote was observed, scored, and documented on post-injury days 1, 4, 14, 35 and 56. Briefly, animals were placed on a flat surface with 6+ inch high walls and allowed to move/walk around the “pool” for 4 min. Sham and SCI rat's joint movement, hindlimb movements, stepping, forelimb and hindlimb coordination, trunk position and stability, paw placement and tail position were monitored and scored. The scale (0–21) represents sequential recovery stages. Bladders were expressed twice daily and relative volume was measured manually.

Tissue processing, sectioning, and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Animals were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and placed on dissection tray. An incision was made in the mid-abdomen and the diaphragm dissected. Incisions on either side of the ribcage were made and the ribcage pinned above the chest. The heart was held with forceps and the right anterior vena cava cut using surgical microscissors. A safety blood collection needle was placed into the left ventricle and 15 ml standard 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (1xPBS) was pumped at a rate of 4 ml/min into the left ventricle, followed by 15 ml 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution. Vertebral columns were removed, placed on ice in 4% PFA, and animal carcasses were disposed. An 8 mm section centered at T9-10 was dissected immediately using forceps, surgical microscissors, and bone rongeur. Rats were perfused with saline and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and spinal cords were collected, dissected, and cryopreserved in 30% sucrose solution.

Tissues were washed overnight in 4% PFA, then washed in 1xPBS for 1.5 h and placed in sucrose. After 24–48 h, tissues were saturated and submerged in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) fluid at −80C. Tissues were sectioned using cryomicrotome, e.g., coronal, or sagittal plane, at 12 μm thickness onto charged glass slides and split into 6 major sections of the spinal cord. Sectioned tissues were stored in long term at −80 °C or short term in 4 °C.

Cryosectioned tissues were removed from −80 °C and placed in room temperature for 30 min. Tissues were rehydrated with 1xPhosphate buffered saline (PBS) and placed into slide chamber. Methanol antigen retrieval was performed for 10 min and washed with 1xPBS twice for 5 min. Tissues were incubated with diluted primary antibody solutions (Supplemental Table S1) and placed overnight at 4 °C. Tissues were washed in 1xPBS three times for 10 min and incubated with diluted secondary antibody solutions for 60 min at room temperature. The tissues were then washed with 1xPBS twice for 10 min and incubated with diluted DAPI nuclear stain solution for 5 min. Tissues were washed in 1xPBS three times for 5 min. Slides were removed from chamber and left to dry, then mounting media and glass cover slip were applied. The Gsx1 antibody was used to evaluate virally infected cells in the SCI+AAV-Gsx1, as the virus is self-complementary and limited in size. Virus mediated Gsx1 expression was validated by IHC using anti-Gsx1 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich #SAB2104632; supplemental Fig. S15).

Microscopy and image analysis

Four to six sections from each animal were analyzed. Images were captured at the same exposure, threshold, and intensity per condition using Zeiss AxioVision imager A1 (Zeiss, Germany) and Echo Revolve (San Diego, CA) at wavelengths 488, 547, 649 nm. Images were processed and cell counted using ImageJ. Co-labeled cells with viral reporter GFP and specific markers were manually counted in separate RGB channels and merged images in an area of 438 μm by 328 μm region adjacent to the injection and lesion site. Alternatively, ZVI files were converted to TIFF format using python code and TIFF files are analyzed using Ilastik's pixel classification module [30]. Pixel intensity and area are quantified, and statistical analysis is performed. A minimum of 5–10 images per animal are required to generate data using cell counting or Ilastik analysis methods. Overall, considerations include systematic/random sampling, antibody staining clearly identifying cells or protein of interest, and calculation of total cell signal were made. Images containing artifacts, tissue folds, and non-specific or unclear antibody binding were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 was used for all statistical analysis. Comparisons between two individual groups were analyzed with two-tailed students T-test (α = 0.05). Comparisons between three groups or more were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test (α = 0.05). BBB scores and vector biodistribution were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (α = 0.05) with a Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test.

Author contributions

Z.F., S.G., and L.C. conceived the project. Z.F. and S.K. performed the animal surgeries. Z.F., F.E, and B.R. conducted animal perfusions, tissue dissections, processing and cryosectioning. Z.F., F.E., T.C, and A.J. performed IHC. Z.F., F.E., A.J., T.C., and J.G. conducted fluorescence imaging. A.J., B.R., H.A., M.D., M.E., A.J.G., J.S., H.P., S.K.G., H.T., S.Z., S.N., performed cell counting for molecular markers. Z.F., M.J.T., and A.J.G. developed the image processing pipeline. Z.F. and F.E. analyzed IHC data. Z.F. and L.C. wrote and edited this paper.

Data availability

All data supporting the results reported in the article can be found in supplemental materials including all prism files and excel files for individual data points.

Declaration of competing interest

L.C. is listed as a co-inventor in the patent application related to this work. L.C. is a founder of NeuroNovus Therapeutics Inc. and a member of the scientific advisory board. S.G. was the CEO of NeuroNovus Therapeutics Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the New Jersey Commission on Spinal Cord Research (NJCSCR)15IRG006 (L.C.), the TechAdvance Fund (L.C.), HealthAdvance Fund (L.C.), the NJCSCR graduate fellowship 22FEL016 (Z.F.), the NIH Biotechnology Pre-Doctoral Training Fellowship T32GM008339 (T.C. and B.R.); and NSF-EEC-1950509, REU Site in Cellular Bioengineering (J.G.). M.J.T. and A.J.G. acknowledge support from NIH NIGMS R35GM138296.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2024.e00362.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sekhon L.H., Fehlings M.G. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2–S12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112151-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li E., Yan R., Yan K., Zhang R., Zhang Q., Zou P., et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the role of immune-related autophagy in spinal cord injury in rats. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.987344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Z., Yuan S., Shi L., Li J., Ning G., Kong X., et al. Programmed cell death in spinal cord injury pathogenesis and therapy. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(3) doi: 10.1111/cpr.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu W., Chi L., Xu R., Ke Y., Luo C., Cai J., et al. Increased production of reactive oxygen species contributes to motor neuron death in a compression mouse model of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(4):204–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park E., Velumian A.A., Fehlings M.G. The role of excitotoxicity in secondary mechanisms of spinal cord injury: a review with an emphasis on the implications for white matter degeneration. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(6):754–774. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molofsky A.V., Pardal R., Iwashita T., Park I.K., Clarke M.F., Morrison S.J. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature. 2003;425(6961):962–967. doi: 10.1038/nature02060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkel Z., Esteban F., Rodriguez B., Fu T., Ai X., Cai L. Diversity of adult neural stem and progenitor cells in physiology and disease. Cells. 2021;10(8) doi: 10.3390/cells10082045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marichal N., Reali C., Trujillo-Cenoz O., Russo R.E. Spinal cord stem cells in their microenvironment: the ependyma as a stem cell niche. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1041:55–79. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69194-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bond A.M., Berg D.A., Lee S., Garcia-Epelboim A.S., Adusumilli V.S., Ming G.L., et al. Differential timing and coordination of neurogenesis and astrogenesis in developing mouse hippocampal subregions. Brain Sci. 2020;10(12) doi: 10.3390/brainsci10120909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesp Z.C., Yoseph R.Y., Suzuki R., Jukkola P., Wilson C., Nishiyama A., et al. Proliferating NG2-cell-dependent angiogenesis and scar formation alter axon growth and functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurosci. 2018;38(6):1366–1382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3953-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford T., Finkel Z., Rodriguez B., Joseph A., Cai L. Current advancements in spinal cord injury research-glial scar formation and neural regeneration. Cells. 2023;12(6) doi: 10.3390/cells12060853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman H., Riesenberg A., Ehrman L.A., Kohli V., Nardini D., Nakafuku M., et al. Gsx transcription factors control neuronal versus glial specification in ventricular zone progenitors of the mouse lateral ganglionic eminence. Dev Biol. 2018;442(1):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei Z., Wang B., Chen G., Nagao M., Nakafuku M., Campbell K. Homeobox genes Gsx1 and Gsx2 differentially regulate telencephalic progenitor maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1675–1680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008824108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S., Kawaguchi R., Heinrichs E., Gallardo S., Castellanos S., Mandric I., et al. In vitro atlas of dorsal spinal interneurons reveals Wnt signaling as a critical regulator of progenitor expansion. Cell Rep. 2022;40(3) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel M., Li Y., Anderson J., Castro-Pedrido S., Skinner R., Lei S., et al. Gsx1 promotes locomotor functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol Ther. 2021;29(8):2469–2482. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su Z., Niu W., Liu M.L., Zou Y., Zhang C.L. In vivo conversion of astrocytes to neurons in the injured adult spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai W., Wu W., Wang L.L., Ni H., Chen C., Yang J., et al. In vivo reprogramming of NG2 glia enables adult neurogenesis and functional recovery following spinal cord injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(5):923–937 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W., Zhang B., Xu S., Lin R., Wang W. Lentivirus carrying the NeuroD1 gene promotes the conversion from glial cells into neurons in a spinal cord injury model. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel M., Anderson J., Lei S., Finkel Z., Rodriguez B., Esteban F., et al. Nkx6.1 enhances neural stem cell activation and attenuates glial scar formation and neuroinflammation in the adult injured spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2021;345 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranzani M., Cesana D., Bartholomae C.C., Sanvito F., Pala M., Benedicenti F., et al. Lentiviral vector-based insertional mutagenesis identifies genes associated with liver cancer. Nat Methods. 2013;10(2):155–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naso M.F., Tomkowicz B., Perry W.L., 3rd, Strohl W.R. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31(4):317–334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothe M., Modlich U., Schambach A. Biosafety challenges for use of lentiviral vectors in gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2013;13(6):453–468. doi: 10.2174/15665232113136660006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milone M.C., O'Doherty U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia. 2018;32(7):1529–1541. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connolly J.B. Lentiviruses in gene therapy clinical research. Gene Ther. 2002;9(24):1730–1734. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder B.R., Gray S.J., Quach E.T., Huang J.W., Leung C.H., Samulski R.J., et al. Comparison of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes for spinal cord and motor neuron gene delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(9):1129–1135. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng S.P., Kugler S., Ma Z.K., Shen Y.Q., Schachner M. Comparison of AAV2 and AAV5 in gene transfer in the injured spinal cord of mice. Neuroreport. 2011;22(12):565–569. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0b013e328348bff5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dirren E., Towne C.L., Setola V., Redmond D.E., Jr., Schneider B.L., Aebischer P. Intracerebroventricular injection of adeno-associated virus 6 and 9 vectors for cell type-specific transgene expression in the spinal cord. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25(2):109–120. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoshino Y., Nishide K., Nagoshi N., Shibata S., Moritoki N., Kojima K., et al. The adeno-associated virus rh10 vector is an effective gene transfer system for chronic spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9844. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46069-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bey K., Deniaud J., Dubreil L., Joussemet B., Cristini J., Ciron C., et al. Intra-CSF AAV9 and AAVrh10 administration in nonhuman primates: promising routes and vectors for which neurological diseases? Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;17:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg S., Kutra D., Kroeger T., Straehle C.N., Kausler B.X., Haubold C., et al. ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat Methods. 2019;16(12):1226–1232. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzone G.L., Mohammadshirazi A., Aquino J.B., Nistri A., Taccola G. GABAergic mechanisms can redress the tilted balance between excitation and inhibition in damaged spinal networks. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58(8):3769–3786. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizuguchi R., Kriks S., Cordes R., Gossler A., Ma Q., Goulding M. Ascl1 and Gsh1/2 control inhibitory and excitatory cell fate in spinal sensory interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(6):770–778. doi: 10.1038/nn1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKeon R.J., Schreiber R.C., Rudge J.S., Silver J. Reduction of neurite outgrowth in a model of glial scarring following CNS injury is correlated with the expression of inhibitory molecules on reactive astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1991;11(11):3398–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03398.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnabe-Heider F., Goritz C., Sabelstrom H., Takebayashi H., Pfrieger F.W., Meletis K., et al. Origin of new glial cells in intact and injured adult spinal cord. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(4):470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flaive A., Fougere M., van der Zouwen C.I., Ryczko D. Serotonergic modulation of locomotor activity from basal vertebrates to mammals. Front Neural Circ. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fncir.2020.590299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sizemore T.R., Hurley L.M., Dacks A.M. Serotonergic modulation across sensory modalities. J Neurophysiol. 2020;123(6):2406–2425. doi: 10.1152/jn.00034.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang C.X., Zhao Y., Mao J., Wang Z., Xu L., Cheng J., et al. An injury-induced serotonergic neuron subpopulation contributes to axon regrowth and function restoration after spinal cord injury in zebrafish. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):7093. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27419-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perrin F.E., Noristani H.N. Serotonergic mechanisms in spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2019;318:174–191. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fauss G.N.K., Hudson K.E., Grau J.W. Role of descending serotonergic fibers in the development of pathophysiology after spinal cord injury (SCI): contribution to chronic pain, spasticity, and autonomic dysreflexia. Biology. 2022;11(2) doi: 10.3390/biology11020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basso D.M., Beattie M.S., Bresnahan J.C. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong J.K., Sharp K., Steward O. A straight alley version of the BBB locomotor scale. Exp Neurol. 2009;217(2):417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ung R.V., Lapointe N.P., Tremblay C., Larouche A., Guertin P.A. Spontaneous recovery of hindlimb movement in completely spinal cord transected mice: a comparison of assessment methods and conditions. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(5):367–379. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang C., Morozova A.Y., Abakumov M.A., Gubsky I.L., Douglas P., Feng S., et al. Precise delivery into chronic spinal cord injury syringomyelic cysts with magnetic nanoparticles MRI visualization. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2015;21:3179–3185. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sroga J.M., Jones T.B., Kigerl K.A., McGaughy V.M., Popovich P.G. Rats and mice exhibit distinct inflammatory reactions after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462(2):223–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.10736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kjell J., Olson L. Rat models of spinal cord injury: from pathology to potential therapies. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9(10):1125–1137. doi: 10.1242/dmm.025833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buss N., Lanigan L., Zeller J., Cissell D., Metea M., Adams E., et al. Characterization of AAV-mediated dorsal root ganglionopathy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;24:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kudo M., Wupuer S., Fujiwara M., Saito Y., Kubota S., Inoue K.I., et al. Specific gene expression in unmyelinated dorsal root ganglion neurons in nonhuman primates by intra-nerve injection of AAV 6 vector. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2021;23:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pellissier L.P., Hoek R.M., Vos R.M., Aartsen W.M., Klimczak R.R., Hoyng S.A., et al. Specific tools for targeting and expression in Muller glial cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2014;1 doi: 10.1038/mtm.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu G., Martins I.H., Chiorini J.A., Davidson B.L. Adeno-associated virus type 4 (AAV4) targets ependyma and astrocytes in the subventricular zone and RMS. Gene Ther. 2005;12(20):1503–1508. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishiyama A., Komitova M., Suzuki R., Zhu X. Polydendrocytes (NG2 cells): multifunctional cells with lineage plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(1):9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mothe A.J., Tator C.H. Proliferation, migration, and differentiation of endogenous ependymal region stem/progenitor cells following minimal spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2005;131(1):177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding W., Hu S., Wang P., Kang H., Peng R., Dong Y., et al. Spinal cord injury: the global incidence, prevalence, and disability from the global burden of disease study 2019. Spine. 2022;47(21):1532–1540. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiu C.W., Cheng H., Hsieh S.L. Contusion spinal cord injury rat model. Bio Protoc. 2017;7(12) doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finkel Z., Cai L. Transcription factors promote neural regeneration after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17(11):2439–2440. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.335805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kathe C., Skinnider M.A., Hutson T.H., Regazzi N., Gautier M., Demesmaeker R., et al. The neurons that restore walking after paralysis. Nature. 2022;611(7936):540–547. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05385-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen B., Li Y., Yu B., Zhang Z., Brommer B., Williams P.R., et al. Reactivation of dormant relay pathways in injured spinal cord by KCC2 manipulations. Cell. 2018;174(3):521–535 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the results reported in the article can be found in supplemental materials including all prism files and excel files for individual data points.