Abstract

Background:

Uganda is burdened by high unintended and teen pregnancies, high sexually transmitted infections, and harm caused by unsafe abortion.

Objectives:

Explore factors influencing sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in Uganda by synthesizing evidence from qualitative studies using a scoping review.

Eligibility Criteria:

Original qualitative peer-reviewed research studies published between 2002 and 2023 in any language exploring factors influencing SRHR in Uganda.

Sources of Evidence:

Eight databases searched using qualitative/mixed methods search filters and no language limits.

Charting Methods:

Information extracted included author, article title, publication year, study aims, participant description, data collection type, sample size, main findings, factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and policy levels, implications for SRHR in Uganda, and study limitations. Quality of the selected articles was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool.

Results:

One hundred seventy-three studies met inclusion criteria. At the individual level, knowledge and attitudes toward SRHR, risky sexual behavior, and access to maternal SRHR services were identified as critical factors influencing health outcomes. Interpersonal factors included communication with sexual partners and relationships with family, school, and community members. Healthcare organization factors included adolescent access to education, SRHR services, and HIV prevention. Cultural and social factors included gendered norms and male involvement in SRHR. Policy-level factors included the importance of aligning policy and practice.

Conclusions:

Multiple factors at individual, interpersonal, community, healthcare, cultural, and policy levels were found to influence SRHR in Uganda. The findings suggest that interventions targeting multiple levels of the socio-ecological system may be necessary to improve SRHR outcomes. This review highlights the need for a holistic approach that considers the broader socio-ecological context. Reducing identified gaps in the literature, particularly between policy and practice related to SRHR, is urgently needed in Uganda. We hope this review will inform the development of policies and interventions to improve SRHR outcomes.

Keywords: reproductive health, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), qualitative research, scoping review, Uganda

Plain language summary

A scoping review of qualitative studies on sexual and reproductive health and rights in Uganda

In Uganda, there are significant challenges regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), including high rates of unintended and teen pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, and unsafe abortions. To better understand these issues, we conducted a comprehensive review of qualitative studies published between 2002 and 2023. Our analysis identified 173 studies that revealed various factors influencing SRHR in Uganda across different levels. At the individual level, factors such as knowledge and attitudes toward SRHR, risky sexual behavior, and access to maternal SRHR services were found to significantly impact health outcomes. Interpersonal relationships also played a crucial role, with communication with sexual partners and relationships with family, school, and community members being identified as important influences. Furthermore, the organization of healthcare services was found to be vital, particularly regarding adolescent access to education, SRHR services, and HIV prevention. Cultural and social factors, including gender norms and the involvement of males in SRHR, were noted as significant contributors to SRHR outcomes. Additionally, the alignment of policy and practice was emphasized as essential for improving SRHR outcomes in Uganda. Overall, the review concluded that addressing SRHR challenges in Uganda requires interventions that target multiple levels of the socio-ecological system. A holistic approach considering individual, interpersonal, community, healthcare, cultural, and policy factors is necessary. There is an urgent need to bridge gaps between policy and practice related to SRHR. Findings could inform the development of policies and interventions aimed at improving SRHR outcomes in Uganda.

Introduction

Uganda is highly burdened by sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) issues.1 –3 The unintended pregnancy rate is 145 in Uganda per 1,000 women aged 15–49 years. 4 Teenage pregnancies are common in Uganda, with one in four adolescents aged 15–19 being mothers or pregnant with their first child. 5 The illnesses and injuries from unsafe abortion significantly burden women and the Ugandan healthcare system. 6 In Uganda, the prevalence of self-reported sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has remained persistently high, with up to 1.5 million cases reported between 2015 and 2017.7,8 These pressing SRHR issues arise at different levels within Uganda’s society and healthcare system. However, our understanding of how these factors and their intricate interactions play out in impacting SRHR outcomes is limited.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (EST) proposes that multiple interacting factors at different social and ecological system levels shape an individual’s behavior and health.9 –12 Within this framework, an individual functions as an integrated system where psychological processes—cognitive, affective, emotional, motivational, and social—operate in coordinated manner to influence behaviors and health outcomes. 13 Understanding these factors and their interactions is crucial for improving SRHR outcomes in Uganda and countries with similar contexts for various reasons. Beyond being fundamental human rights, ensuring access to comprehensive SRHR services is essential for public health and mitigating maternal mortality and morbidity in Uganda. 14 Promoting social justice by empowering marginalized groups, fostering economic development by enabling individuals to make informed reproductive choices, and fulfilling global commitments can be done through improving SRHR. 15 Recognizing the interconnectedness of SRHR with broader social, economic, and environmental challenges is imperative for promoting the well-being and rights of individuals and communities in Uganda and beyond. 16

For this review, we operationalized SRHR comprehensively as encompassing a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being relating to the reproductive system, including sexuality education, preconception care, antenatal and safe delivery care, postnatal care, STI/HIV prevention services, preventive screening, and early diagnosis and treatment of reproductive health illnesses and cancers. 17

A scoping review of qualitative studies on SRHR in Uganda guided by EST can provide an understanding of the factors at multiple levels influencing SRHR outcomes. The EST was chosen because it provides a robust framework for scoping reviews, allowing researchers to explore diverse evidence, understand complex contextual interactions, and identify gaps in the literature to drive evidence-informed decision-making.18 –20 We are doing a scoping review of qualitative studies on SRHR in Uganda to consolidate knowledge, identify gaps, and provide insights to inform policies, practices, and research priorities in this critical area of public health and human rights. The objective of the scoping review is to identify and synthesize qualitative evidence on individual, interpersonal, healthcare, cultural, and policy level factors influencing SRHR in Uganda. The research question is “What are the factors influencing SRHR outcomes in Uganda at multiple levels?.” Understanding these factors can inform the development of comprehensive, context-specific interventions that address the broader socio-ecological context in which individuals live.

Methods

This scoping review followed the methodology of Arksey and O’Malley 21 for scoping reviews to identify the research question, search for relevant studies, select studies based on predefined criteria, chart the data from included studies, and then collate, summarize, and report findings. This method provides a structured approach for mapping the literature on SRHR, offering flexibility in study selection and data synthesis. 21 Overall, Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology facilitates a comprehensive overview of existing evidence while allowing for adaptability to different research contexts.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted by a health sciences informationist (GKR) in May 2022 and updated in May 2023.The eight databases searched were MEDLINE (via Ovid interface), EMBASE (via Embase.com), Scopus, CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), Web of Science Core Collection (via Thomson Reuters), Global Health (via CABI), PsycINFO (via EBSCOhost), and Women’s Studies International (via EBSCOhost). Keyword and controlled vocabulary search terms were used to represent concepts related to SRHR in Uganda. Geographic search terms focused search retrieval on articles referencing Uganda at the country level, by district 22 or capital city of Kampala. A revised qualitative/mixed methods search filter was used in all eight database searches. 23 Two unique qualitative/mixed methods search filters were revised for use in Ovid Medline to maximize retrieval of qualitative studies.23,24 Final search strategies were determined through test searching and search syntax to enhance search retrieval. Search results were limited to articles published from 2002 to 2023. No language limits were applied. Selecting the last 20 years as a timeframe ensured a focus on recent literature, capturing contemporary developments and trends, particularly relevant in the post-conflict setting of northern Uganda. This timeframe struck a balance between covering a substantial period for comprehensive analysis while excluding older literature that may be less relevant due to changes in methodologies or contexts, thereby enhancing the review’s relevance and applicability to current practice and research in the post-conflict environment of Uganda. The search strategies can be accessed at https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/8639

The comprehensive literature search was conducted to address overall SRHR in Uganda as a whole. Due to the breadth and scope of the literature retrieval, this one search was used to inform two scoping reviews on qualitative studies: one to address family planning and comprehensive abortion care in Uganda 25 ; and this review which addresses SRHR in Uganda. The study selection for each of the two scoping reviews was differentiated by their use of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study selection, screening, and data extraction

Inclusion criteria were original qualitative research studies that explored factors influencing SRHR in Uganda with Ugandan citizens of any age or gender, published between 2002 and 2023 in any language in peer-reviewed scientific publications. We included studies with data from several countries if Uganda-specific data were reported separately. Exclusion criteria were studies not focused on SRHR; not completed with qualitative or mixed methods; not published in a peer-reviewed journal, dissertations, abstracts, commentaries, or editorials; and did not include Ugandan citizens, or conducted outside Uganda.

Using Rayyan, a web-based screening tool, 26 at least two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts, and full-text articles (JMB, EA, RG, FPP, FJD, AGA, EK, TE, and YS) for eligibility. A third reviewer from the same group resolved any discrepancies. Independent screening by multiple reviewers helped to minimize bias.

Data extraction included information on the author(s), article title, year of publication, study population, study aims, sample size, factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and policy levels that influence SRHR outcomes in Uganda, study limitations, and implications for SRHR in Uganda (JMB, RG, FPP, FJD, AGA, EK) (Supplemental Appendix 1). The use of the data extraction forms helped ensure consistency and reduce bias. The quality of the selected articles was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies. 27 To use the CASP tool, we began by carefully reading the study to understand its objectives, methods, and findings. Then, we systematically applied the CASP tool’s criteria, such as assessing the appropriateness of the research design, data collection methods, and analysis procedures, to critically evaluate the study’s rigor, credibility, and relevance to the review. Hand searching of reference lists was not performed.

Data synthesis involved systematically collecting, organizing, and summarizing information from scientific sources to provide an overview of existing literature on SRHR in Uganda. Thematic analysis was used to synthesize the data and identify common themes across the studies. Themes were identified through iterative processes of data coding and categorization, with emerging patterns and concepts refined through discussions among researchers. Validation involved checking the consistency of identified themes against the data, ensuring they accurately reflected the breadth and depth of the scientific literature. Findings were reported under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. 28

Results

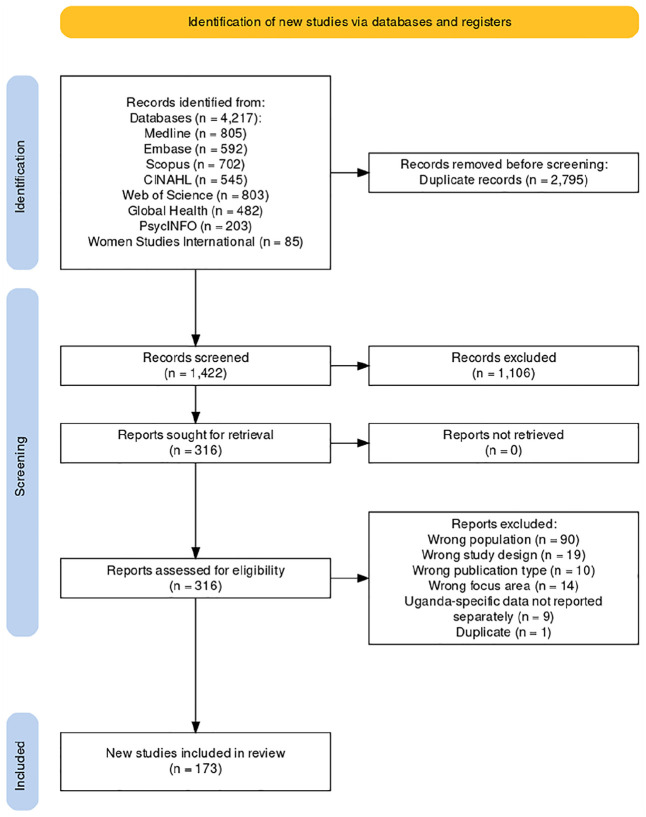

A total of 173 qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this scoping review of investigations exploring factors influencing SRHR in Uganda. The PRISMA diagram is shown in Figure 1, generated using a web-based tool created by Haddaway et al. 29 The data extraction form is available in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of articles screened for scoping review of qualitative studies of sexual and reproductive health and rights in Uganda, 2002–2023.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

Study topic areas and aims

Over the last two decades, researchers in Uganda have studied various topics related to SRHR. Figure 2 depicts the most frequently studied topic areas. The most common topics studied were adolescent and younger adult (ages 13–24 years) health (n = 64), HIV (n = 56), and maternal health (n = 27). Regarding adolescent and young adult health, topics most often covered included sexual education (n = 15), pregnancy (n = 13), HIV (n = 13), and cultural and gender norms (n = 9). Pertaining to HIV, researchers more often studied prevention (n = 12), serodiscordance in HIV status within a couple (n = 10), pregnancy decision-making (n = 8), and sex work (n = 4). For maternal health, topics researched more frequently were access to SRHR services (n = 8), childbirth experiences (n = 6), male involvement (n = 4), and obstetric fistula (n = 3). Other topics studied included gender norms (n = 6), cervical cancer prevention (n = 5), access to SRHR services for people living with disabilities or mental health concerns (n = 5), sexual- and gender-based violence (n = 4), and access to SRHR services during COVID (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Qualitative study topic areas related to SRHR in Uganda 2002–2023. The size of the wedges represents the number of the topic areas relative to the total number of studies included. The outer wedge represents the top 3 most frequent study topics within each sub-category.

SRHR: sexual and reproductive health and rights.

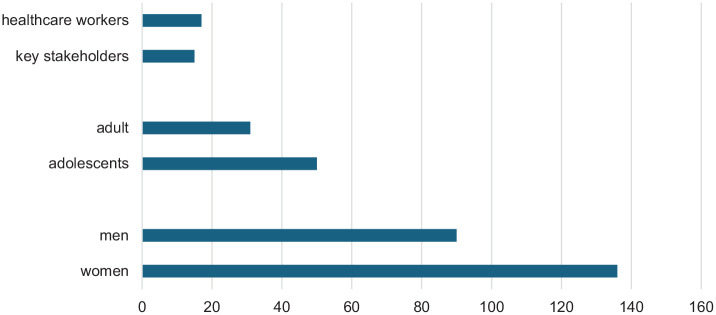

Study participants

Regarding study participants, women were the most common study population gender (n = 136) and adolescents (n = 50) were the most common study population age. A smaller number of investigations included key healthcare policymakers (n = 15) and healthcare workers (n = 17) (Figure 3). Some investigations included both men and women, mixed ages (adolescents and adults), and had diverse participant types (e.g., key stakeholders and healthcare workers). Several articles did not define what they meant by stakeholders, most articles defined them as policy makers, ministry of health officials, village elders, etc.

Figure 3.

Types and frequency of Ugandan study populations in published SRHR investigations, 2002–2023. More than one population may have been included in a single study; therefore the frequency adds to greater than the total number of studies (n = 173).

SRHR: sexual and reproductive health and rights.

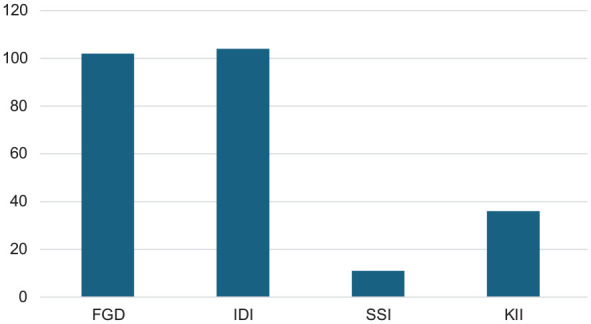

Qualitative data collection approaches

Regarding data collection, focus group discussion (FGD) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) were the most commonly used data collection methods, with 102 manuscripts using FGDs and 104 using IDIs (Figure 4). Of the 173 manuscripts identified, 11 studies used semi-structured interviews, and 36 included key-informant interviews as data collection approaches.

Figure 4.

Data collection approaches used by sexual and reproductive health and rights investigations in Uganda, 2002–2023. If a study had multiple data collection types, it was included in this figure multiple times.

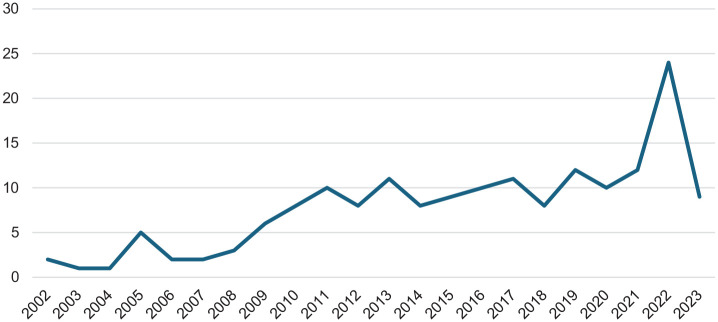

Publication years

Figure 5 shows the publication years of the 173 studies included in our sample. The publishing trend increases over time and spikes with 24 publications in 2022. The 2023 publication data are incomplete and may explain the lower number.

Figure 5.

Frequency of SRHR manuscript publication per year in investigations conducted in Uganda, 2002–2023.

SRHR: sexual and reproductive health and rights.

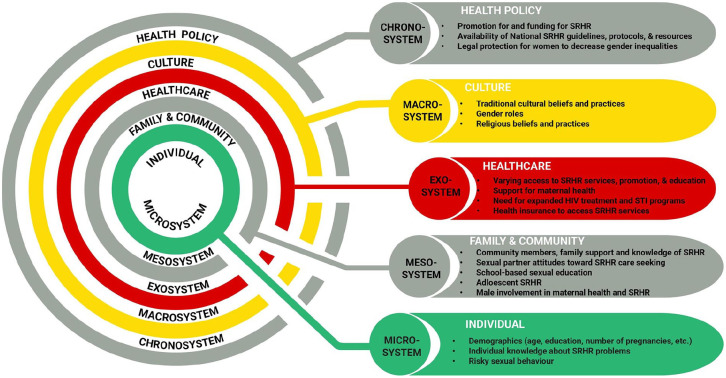

Data analysis

Overall, we can situate factors influencing SRHR in Uganda at various levels of the socio-ecological system. Bronfenbrenner’s EST proposes that an individual’s development is influenced by a complex interplay of multiple environmental systems.9 –12 These systems include the microsystem (immediate environment), mesosystem (interactions between microsystems), exosystem (external environments indirectly affecting the individual), macrosystem (cultural and societal norms), and chronosystem (temporal changes over an individual’s lifespan).9 –12 The EST emphasizes the dynamic interactions between these systems, highlighting the importance of considering broader contextual factors beyond immediate influences.9 –12 This scoping review of qualitative studies provides a comprehensive understanding of the multiple factors influencing SRHR outcomes. We incorporated factors influencing SRHR found in qualitative studies in Uganda into an adapted EST model, modified from the model proposed by Buser et al., 30 shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Adapted Ecological Systems Theory model to show factors influencing SRHR found in qualitative studies in Uganda, 2002–2023.

SRHR: sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Overview of qualitative studies in Uganda framed by the Ecological Systems Theory

Table 1 provides representative quotations from participants of included studies organized by EST level.

Table 1.

Representative quotations of participant views on sexual and reproductive health and rights in Uganda framed by the Ecological Systems Theory.

| Ecological Systems Theory level | Representative quotation |

|---|---|

| Individual (microsystem) | “I got a pregnancy that I did not want and this was the birth of my second born because my first born was still young and by that time I did not know anything about birth control methods because I was still young.” (Female, 31, HIV−, IDI) 31 “. . .I think that it is because of the too much work that women have at home that stops them from going to the hospital.” (Woman, IDI) 32 |

| Family and community (mesosystem) | “With this male circumcision, most men in the village have become Muslims and for me I am worried my wife may not be enjoying sex as before because now my foreskin which was sensational is gone.” (middle-aged male participant, FGD)

33

“In our culture as ‘Bunyoro’ people, those [reproductive health] issues a girl only discusses with the mother. A man can never enter into such discussions.” (FGD 4) 34 |

| Healthcare organization (exosystem) | “The People With Physical Disabilities (PWPDs) are not well catered for in our hospitals. Labor wards lack special facilities for PWPDs such as adjustable delivery beds and health centers are not easily accessed due to many steps and lack of ramps. Although suggestions have been made on the need to make healthcare facilities disability friendly, the Ministry of Health has not yet put [this] into consideration.” (Key informant)

35

“I came here when my wife was going to deliver, but the midwife harassed me and my wife who was in pain. She said that my wife was not able to give birth and needed to be referred to Kabale Hospital but in no time the baby came out. Since then I swore never to accompany my wife to the hospital because I cannot stand witnessing such harassment without retaliating.” (middle-aged male participant, FGD) 33 |

| Culture (macrosystem) | “They also [healers] give us herbal medicine, which is administered through bathing it mixed with water [in form of herbal bath]. It is important to take herbal bath when pregnant. . this medicine is got from the traditional healers. It refreshes body and helps to regain energy.” (Pregnant married adolescent, FGD)

36

“The senga (father’s sister) gave examples of different situations in which men or boys could seduce us. They told us different ways of avoiding trouble. They often narrated their own experiences and told us tricks they used to avoid such risk. They often helped us to relate their situations to ours and then judge for ourselves. Now if a boy insists too much, I ask him to come to my home. Most boys fear coming home because of your parents. They definitely fear to face your parents, then they leave you alone.” (Schoolgirl, FGD) 37 |

| Health policy (chronosystem) | “There is a policy on adolescent reproductive health; there is also another policy on provision of integrated youth friendly. . . reproductive health services, but the implementation of the policy is what is lacking.” (Female Nursing Officer, IDI)

38

“Neither were health workers trained to receive men nor do they do anything for men when they come. Men weren’t allowed inside, and it wasn’t convenient. Even now they really struggle with what to do with men? Because a lot of the health facilities are like dormitories and even maternity wards are quite like dormitories so then how do you bring in a man?” (FGD participant) 39 |

FGD: focus group discussion; IDI: in-depth interview.

Individual level (microsystem)

At the individual level, the included studies identified knowledge and attitudes toward SRHR, risky sexual behavior, and access to maternal SRHR services as key factors influencing health outcomes in Uganda. Many of the articles focused on themes related to HIV. The themes were individuals’ knowledge of the HIV epidemic,40 –43 their perception of their own risk,44 –46 and the effect of their risk-perception on their behavior.47 –51 Studies also explored the experience of young people born with HIV.52 –55 Researchers found there is a disconnect between the educational information the health service providers give to HIV-positive young people and their actual needs and desires, 54 and that HIV-positive youth need support in developing the appropriate behavioral skills to adopt healthy sexual behaviors. 53

Several articles explored why individuals from varied study populations engage in risky behavior, focusing on street youth, 56 university students, 57 people with mental illness, 58 individuals exposed to war trauma, 59 those with food insecurities, 60 and adolescents. 61 Among adolescents and youth who moved from rural districts to the streets of the capital city, Kampala, three primary pathways were found to drive risky sexual behavior: (1) rural–urban migration itself, through sexual exploitation of and violence toward street youth, especially young girls, (2) economic survival through casual jobs and sex work, and (3) personal physical safety through friendships and networks, which led to having multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex. 56 Meanwhile, Lundberg et al. highlight how serious mental illness and gender inequality contribute to sexual risk behaviors and sexual health risks, including HIV risk, and call for targeting this population with HIV risk reduction interventions. 58

Matovu and Ssebadduka and Wanyenze et al. explored individuals’ choices to use condoms.62,63 Study findings underscore the need for interventions that address condom use barriers and misconceptions about female condoms.62,63

Regarding efforts to decrease maternal mortality, Ssebunya and Matovu and Austin-Evelyn et al. studied possible solutions to motivate women to give birth in healthcare facilities.64,65 Ssebunya and Matovu explored how women decided to travel to healthcare facilities in motorcycle ambulances and found that those who had made birthing plans with their male partners were more likely to access transportation. 64 The study emphasized the need for reproductive health interventions to involve men. Austin-Evelyn et al. studied why women choose to deliver in a facility rather than at home and determined that when well implemented, in-kind goods, such as baby blankets and diapers, given at the healthcare facility, can be important complements in broader efforts to incentivize facility delivery. 65

Studies also evaluated the knowledge and perceptions among women of using prenatal sonograms to determine the fetus’ sex and the factors that affect whether mothers breastfeed.66,67 Gonzaga found that women preferred to know the sex of their fetuses in order to better plan. 66 Lack of information on nutrition also affected how women are able to feed their infants. 67 Namujju et al. explored women’s experiences of childbirth and concluded that because these experiences were unique, there is a need to design interventions focusing on individualized care. 68 Chemutai et al., along with Kabwigu and Nsibirano, analyzed the challenges of motherhood and teen pregnancy.69,70 Mathur et al. explored how men felt about parenthood and found that young men consistently reported the desire for fatherhood as a cornerstone of masculinity and a transition to adulthood. 71 Three other studies explored the decision-making of HIV-affected couples who want children.72 –74

Interpersonal level (mesosystem)

At the interpersonal level, studies focused on relations with school, family, the community, and sexual partners. There were studies on the link between school enrollment and health risks,75,76 and how knowledgeable school students were about SRHR issues.57,77,78 Iyer and Aggleton explored teachers’ views of appropriate sex education and found that teachers express negative attitudes toward young people’s sexual activity and are not neutral delivery mechanisms in schools. 79 Their attitudes and beliefs must be considered and addressed in the development of school-based sex education programs. Meanwhile, Muhanguzi and Ninsiima investigated the need for sexual education to be designed around students’ experiences and called for a rigorous re-examination of the current sexuality learning resources. 80 Furthermore, they advocate for an empowerment approach that integrates gender dynamics throughout the teaching of sexuality matters to address both boys’ and girls’ sexual needs.

Pichon et al. and Ndugga et al. explored how parents communicate SRHR issues with their children.81,82 Pichon et al. found that parents used three approaches to discuss sex and transactional sex with their daughters: (1) frightening their daughters into avoiding sex; (2) being “strict”; and (3) relying on mothers rather than fathers to “counsel” daughters. 82

Råssjö and Kiwanuka examined how the community influences young peoples’ perspectives on SRHR and they advocate for a single strong message from healthcare workers and teachers to dispel myths about abstinence, being faithful, and using condoms. 83 The community’s perspective on obstetric fistulas, 84 cesarean delivery, 85 breastfeeding, 67 and male involvement in maternal care86,87 were also studied and found similar themes. Several studies looked at the relationships of sexual partners. Nalukwago et al. and Nobelius et al. sought to understand why adolescents have concurrent sex partners and the related health risks.88,89 Other studies focused on female sex workers (FSWs), for example, how men perceive their relationships with FSWs and the risk of HIV.90 –92 Mujugira et al. explored how FSWs’ prevention choices are influenced by HIV treatment availability and proposed that communicating the benefits of HIV self-testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to stakeholders could strengthen the uptake and use of combination prevention interventions in this marginalized population. 93 Nyanzi et al. also studied how income from selling vegetables, garments, or other goods at markets empowers women to negotiate sex and condom use with their partners. 93 They discovered that market work did not change societal expectations regarding “correct behavior” for wives 94 Consequently, women still faced challenges when it came to initiating sex, denying sex, or asking for condoms. 94 This study illuminates the intricate relationship among economic empowerment, gender norms, and sexual health, emphasizing the necessity for holistic strategies that tackle both financial independence and gender roles to enhance women’s welfare and mitigate risks of adverse consequences. Several studies focused on communication between couples. Grilo et al. explored the perception of couples with recent unintended pregnancies and found that a lack of communication between partners compounded a lack of agency at the individual level. 31 The topic of HIV serodiscordance in couples and how they navigate preventing HIV transmission was discussed by King et al., 95 Nakku-Joloba et al., 96 Matovu et al., 97 and Pratt et al. 92 Coercion was also explored: how it leads to unwanted pregnancy, 98 other negative health outcomes. 99 Birungi et al. sought to understand how adolescents viewed coercion and Kyegombe et al. looked at the link between coercion and transactional sex in adolescents.100,101 Meanwhile, Wagman et al. explored how interventions could influence young people to voice their opinions within relationships more and proposed that violence prevention programs develop various strategies for addressing sexual coercion among adolescents. 99

Healthcare organization (exosystem)

At the level of healthcare organization, some of the studies focused on adolescents’ access to education and SRHR services, while others investigated HIV treatment. They investigated how teens perceive sex education80,102 and how they act on the information they are taught. 103 Some studies examined where the adolescents were getting and how well they retained the information. Miller et al. compared the knowledge learned through media versus from parents, school, and religion and identified the need for further investigation of the role of exposure to sexual TV programming in the sexual socialization of Ugandan youth. 104 McGranahan et al. and Nobelius et al. explored how out-of-school children and those living in slums receive SRHR information.105,106 They found that while there are many sources accessible to children, including the media and parents, they need access to formal accurate information. The need for accurate sex education in schools was also apparent in studies that looked at what students knew about HIV and pregnancy77,79 and how HIV related to puberty. 107

Other studies at this level explored adolescents’ access to services. Atuyambe et al., 36 Atuyambe et al., 108 Nambile Cumber et al., 109 Namutebi et al., 110 and Rukundo et al. 111 specifically looked at the services available to teen mothers and pregnant teens. McGranahan et al. explored the role of service providers in influencing young people to utilize SRHR services and suggested that targeted interventions for the realizing adolescent girls’ and young women’s SRHR can address underlying causes and positively shift attitudes to promote health. 105 Akatukwasa et al. also studied how effectively HIV and SRHR services for young people have been integrated into the healthcare system. 38 Atuyambe et al. explored young people’s attitudes toward the available SRHR services and concluded that Ugandan adolescent SRHR problems and needs are multifaceted and multi-leveled which require multi-stakeholder engagement and multi-sectoral interventions at all levels from households, community structures, health facilities, and policy levels. 112 Onukwugha et al. explored the experience of unwed adolescents who access the SRHR services and determined that a youth-friendly health policy does not translate into adequate youth-friendly service provision. 113

Some studies explored issues of access and service delivery more broadly. Rutakumwa and Krogman and Weeks et al. looked at the effect of not having access to affordable healthcare.114,115 There were also studies about the limited access to SRHR services by marginalized groups such as those with disabilities and mental illnesses.35,116 –120 Magunda et al. explored what factors influence people to use SRHR services, 117 other studies looked at the experience of women who sought services.32,108,121 –123 Mwase et al. studied women’s experience using a new toll-free line to access Maternal and Newborn Health Services and proposed that addressing maternal mortality in low-income settings necessitates increased investment and scale-up such high-impact mHealth interventions. 124 Nakku et al. studied the feasibility of delivering perinatal mental healthcare and identified a need for interventions to respond to this neglected public health problem and a willingness of both community- and facility-based healthcare providers to provide care for mothers with mental health problems. 125 Two studies looked at how men were encouraged to be involved in reproductive and maternal healthcare.33,126

Several studies looked at HIV treatments. Lofgren et al. explored the barriers to care. 127 Kipp et al. and Kwiringira et al. explored the availability of testing and counseling.128,129 Larsson et al. explored men’s view of testing couples for HIV and proposed that to implement a successful, culturally adapted couple testing policy in Uganda, gender differences in health-seeking behavior, health systems’ different effects on men and women, and gender structures in society at large must be taken into account. 130 Meanwhile, Logie et al. explored testing strategies among urban youth and suggest that findings can inform multi-level strategies to foster enabling HIV testing environments with urban refugee youth, including tackling intersecting stigma and leveraging refugee youth peer support. 131 Kawuma et al. 48 looked at how FSWs access HIV treatment and Mbonye et al. 91 looked at the uptake by men in relationships with FSWs. Lofgren et al., Lubega et al., and Zakumumpa et al. explored barriers to continuing treatment.127,132,133 Bell and Aggleton explored how to improve HIV interventions within the local context. 134 Kayesu et al. 49 and Muyinda et al. 37 focused on how to reach adolescents. Atuyambe et al. also explored the challenges faced by young people living with HIV transitioning from pediatric to adult care services. 36 A few studies explored how service providers shaped childbearing decisions by people with HIV.135 –137

Other studies looked at the views of treatments for other SRHR issues, including access to cervical cancer screening138,139 and treatments of obstetric fistula.84,140,141 Mangwi Ayiasi et al. explored the benefit of Village Health Teams (VHTs) home visits using mobiles to link professional healthcare workers and proposed that home visits made by VHTs and backed up by formal healthcare systems through the use of mobile phone consultation can contribute to prompt and accurate educational messages offered for maternal and newborn care. 142

Social and cultural (macrosystem)

At the social and cultural level, researchers investigated how gender norms affected how young people gained SRHR knowledge. Achen et al. looked into how gender norms changed how parents communicate with their children about SRHR issues and proposed that gender stereotypes can be addressed through community programs that engage boys in activities traditionally reserved for girls and girls in activities reserved for boys. 143 Iyer and Aggleton explored how views of gender affected what was deemed “appropriate content” for sex education classes, 79 whereas Evelo and Miedema studied how gender norms shaped students’ participation in sex education classes. 144

Investigations of adolescent SRHR and teenage pregnancy were also common. Achen et al. and Bell and Aggleton explored the role of culture in shaping young people’s sexual health.145,146 Ninsiima et al. 147 and Råssjö and Kiwanuka 83 looked at how social constructs and gender norms influence adolescent agency in making decisions around sex. Although Kyegombe et al., Lundgren et al., Ninsiima et al., and Nobelius et al. explored how young people in society are deemed ready for sex,148 –151 Neema et al. explored the cultural drivers of child marriage. 152 The experiences of teen mothers and pregnant teens within the society were also studied.108,153,154 Beyeza-Kashesy et al. explored the cultural influences of high fertility motivation among young people and proposed that innovative cultural practices and programs that increase women’s social respectability, such as emphasis that a girl can be an heir and inherit her father’s property are needed to reduce son preference. 155

Other studies explored how gender relations from childhood lead girls into sex work.147,156,157 Ninsiima et al. concluded that in addition to educating children, teachers, and parents about the values of gender equality, there is a need for Uganda to strengthen the legal framework. 147 Researchers put forth that an enabling legislative and policy framework is critically important in supporting adolescents, teachers and parents to address the health and well-being of adolescents. 147

Several articles studied the intersection of culture and HIV. For example, how the importance of childbearing in Uganda culture impacted how HIV affected couples’ and individuals’ childbearing decisions.136,158,159 King et al. explored how cultural norms and stigma experienced by the LGBTQ community drive HIV transmission.160,161 Meanwhile, Rugambwa et al. explored how indigenous knowledge can positively affect HIV prevention but found that adolescents receive misleading health misinformation that exposes them to the risk of HIV infections. 162

Researchers also investigated society’s views on SRHR impact treatment. These include how views of the cause of obstetric fistula delay diagnoses,140,141 how beliefs affect voluntary medical male circumcision, 163 and how views of sexual violence affect women’s reproductive health outcomes.164,165

A few articles specifically explored male involvement in SRHR. Gopal et al. explored the influences of men’s perceptions of male involvement initiatives and suggested that community engagement is critical to successful implementation. 39 Schmidt-Sane and Schmidt-Sane studied the gender and power dynamics of men in relationships with FSWs.92,166

Public health policy (chronosystem)

At the Public Health Policy level, the studies explored factors related to aligning policy and practice. They sought how likely new policies would solve problems. For instance, Lofgren et al. looked at barriers to antiretroviral therapy initiations and HIV care to inform the implementation of a Universal Test-and-Treat policy and concluded that stigma still prevents people from accepting care, and initiatives that give social support are needed. 127 Katahoire et al. studied the readiness of communities to accept a human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine policy and found that most respondents did not know about cervical cancer but understood the benefits of vaccination. 167 However, key-informant interviews from the national level indicated Uganda does not have a cervical cancer screening program, and there are significant barriers to developing one. 166

Researchers also explored the efficacy of existing policies. These policies included HIV risk-reduction interventions, 168 male involvement initiatives, 39 and pre-antiretroviral care policies. 132 Pre-antiretroviral care policies refer to healthcare protocols and guidelines implemented before the initiation of antiretroviral therapy for individuals living with HIV/AIDS to assess the patient’s health status, readiness for antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and to address any co-existing medical conditions or psychosocial needs before initiating antiretroviral therapy. 169 Research by Lubega et al. underscores the importance of adopting a comprehensive strategy toward pre-antiretroviral care, encompassing not solely medical interventions but also addressing social, economic, and cultural elements. 132 Sensoy Bahar et al. found their intervention improved participants’ ability to engage in safer sex, 168 while Gopal et al. determined male involvement initiatives could be sustained through community engagement with the Ugandan government and donors. 39

One study also explored the effect of “Mama Kits” on women’s decision to give birth in a facility and found that when available, kits positively affected women’s perceptions of facility delivery because they associated availability of kits with affordability of care, but when not available, women’s perceptions of their actual or expected delivery experience were negatively affected. 65 Meanwhile, Rijsdijk et al. explored the Universal Declaration of SRHR within the context of Uganda and found discrepancies between the universally formulated rights to complete and accurate information and education on SRHR and rights to sexual self-determination on SRHR matters and the (political, economic, and community) context young Ugandans live in Uganda. 170 Rijsdijk et al. proposed that comprehensive rights-based sex education should consider (content, style, and form) the local context to make SRHR meaningful for Ugandan adolescents. 170

Other studies focused on how policies affect access to SRHR services by young people,109,111,113 people with disabilities, 35 and mental illness. 120 These described age restrictions denying adolescents care 113 but also the belief that the government is not putting enough of an effort into programs that support adolescents. 113 The distances to access facilities and the price also are a barrier. 35 A subset of these studies explored how COVID-19-related policies affected access to SRHR services.171 –173 Several participants in the Bukuluki et al. study noted difficulties in traveling to health facilities during the COVID-19 lockdown, including harassment and mistreatment from security agencies. 171 The requirement for detailed explanations and documented evidence to be allowed to go to health facilities disrupted their access to SRHR services. 171 Kibira et al. concluded that improving core health system elements such as a continued focus on community engagement, ensuring healthcare workers are informed, equipped, and supported, improving transportation, and ensuring commodities are available is essential for a resilient system in Uganda. 173

Limitations of scoping review studies

As identified by researchers, there were limitations in qualitative studies on SRHR in Uganda, including social desirability bias leading to potentially skewed responses,34,55,56,119,137 while issues surrounding the sensitive nature of subjects like transactional sex,40,156 and personal concealment 101 introduce further biases. Scope restrictions, whether in terms of geography,82,112 specific groups,53,98 –100,174,175 or age categories,77,176 hinder the generalizability of findings. Dominance effects within FGDs,67,131 coupled with definitional inconsistencies101,112 and researcher biases 67 could undermine the validity of results. Selection59,75,136 and recall55,154 biases further compromise reliability, and even challenges in translation 177 introduce additional complexities. These limitations underscore the necessity for cautious interpretation and more comprehensive methodologies when conducting and conveying qualitative SRHR research in Uganda.

Discussion

The findings of this scoping review on factors influencing SRHR outcomes in Uganda, guided by the EST, suggest that a comprehensive and multi-level approach is necessary to address the complex and interrelated factors influencing SRHR outcomes in Uganda. At the individual level, the studies identified limited knowledge and negative attitudes toward SRHR as crucial factors influencing health outcomes in Uganda. These findings highlight the existence of limited SRHR educational and awareness-raising activities in Uganda and the need for targeted education and awareness-raising campaigns to improve knowledge and attitudes toward SRHR, particularly among men, who play a critical role in decision-making related to SRHR in intimate relationships. It will also improve the involvement of men in the struggle to improve health seeking behavior for men and their role in the SRHR service utilization, which will translate into better SRHR health outcomes.

At the interpersonal level, the studies identified communication within intimate relationships, school, and social support as key factors in SRHR. These findings suggest the need for interventions that promote access to sexual education, facilitate open communication within intimate relationships, and address gender-based violence. Notably, the review highlights the critical gap in the attempt to mitigate sexual and gender based violence. The findings could be used to generate strategies to target gender based violence as an interpersonal and a cultural challenge. Interventions designed to target policies at both levels could mitigate the sexuality-related communication and sex education gaps in Uganda. At the healthcare organization level, the review identified barriers to accessing SRHR services and HIV treatment, indicating a need for interventions that improve access to SRHR services, particularly for HIV, and that engage communities in efforts to address the modifiable barriers.

While the scoping review of qualitative studies on SRHR in Uganda is unique, we can situate our findings in relation to other studies focused on the region. Regarding adolescent and young adult SRHR, in line with findings, researchers reviewing the progress toward fulfilling young people’s SRHR by East and Southern African health ministries found that adolescent and young adults still face challenges, but propose that sustained political, technical, and financial investment in their health and rights will ensure that countries in the region will thrive in the future. 178 The article provides a review of progress made between 2013 and 2018 toward fulfilling young people’s SRHR within the East and Southern Africa Ministerial Commitment, offering insights into achievements and challenges in the region’s efforts to address SRHR needs among young people. 178

Furthermore, a review of qualitative research in four East African countries concluded that parents and other adults’ discussion with adolescents on reproductive health issues is imperative in reducing risky behaviors among adolescents. 179 The article presents a review of qualitative research in four East African countries, highlighting barriers to parent–child communication on SRHR issues. 179 For effective communication on reproductive health issues, parents and adults need to be educated on their roles as primary sources of SRHR information to their children, and there is also a need to address gender differences and socio-cultural norms that hinder effective communication. 179

Related to male involvement in SRHR, researchers conducting a narrative systematic review on men’s involvement in SRHR in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) found contributors to poor SRHR service uptake to include a lack of access and availability of SRHR services, poor health-seeking behavior among men, and SRHR facilities without “male friendly” spaces and not providing men’s services under one roof. 180 These researchers shed light on other barriers including cultural norms, stigma, and limited awareness, while facilitators to male involvement in SRHR were perceived benefits, partner influence and access to information. 180 These findings are consistent with the SRHR studies conducted in Uganda included in this review.

Pertaining to HIV, researchers in a rural Kenyan setting explored the psychosocial and mental health challenges experienced by emerging adults living with HIV, while also exploring the support systems that facilitate their positive coping mechanisms. 181 They adapted the EST to investigate the challenges faced by emerging adults living with HIV and determined they face various challenges at the individual, family, and community level, some of which are cross-cutting, 181 and are consistent with the findings of the SRHR studies conducted in Uganda included in this review. Their findings underscore the need for designing multi-level youth-friendly interventions to address modifiable challenges encountered by emerging adults living with HIV in Kenya and similar settings, such as Uganda. 181

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this review is that it is the first qualitative scoping review of factors influencing SRHR in Uganda of which we are aware. Since the review was focused on Uganda, findings might not be generalizable to other settings.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this scoping review highlight the existence of factors operating at individual, interpersonal, community, healthcare organization and policy levels and underscore the need for a multi-level and comprehensive approach to improving SRHR outcomes in Uganda. Interventions and policies that address factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, healthcare organization, and policy levels are needed to create an enabling environment for improved SRHR outcomes in Uganda. A focus on reducing the identified gaps in the qualitative literature, particularly between policy and practice related to SRHR, is urgently needed in Uganda to improve health outcomes. It can potentially improve the well-being of individuals and communities in Uganda. We hope this scoping review will contribute to the evidence base on SRHR in Uganda and inform the development of policies and interventions that aim to improve SRHR outcomes in the country and similar settings.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057241285193 for A scoping review of qualitative studies on sexual and reproductive health and rights in Uganda: Exploring factors at multiple levels by Julie M Buser, Edward Kumakech, Ella August, Gurpreet K Rana, Rachel Gray, Anna Grace Auma, Faelan E Jacobson-Davies, Tamrat Endale, Pebalo Francis Pebolo and Yolanda R Smith in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Julie M Buser  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0346-0710

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0346-0710

Carmella August  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036

Pebalo Francis Pebolo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1205-1150

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1205-1150

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable. IRB approval was not required for this scoping review because it involved synthesizing existing literature rather than collecting new data from human subjects.

Consent for publication: Not applicable. Consent for publication was not required for this scoping review since we analyzed existing literature rather than involving direct data collection from human subjects.

Author contribution(s): Julie M Buser: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Edward Kumakech: Formal analysis; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Ella August: Formal analysis; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Gurpreet K Rana: Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Rachel Gray: Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Anna Grace Auma: Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Faelan E Jacobson-Davies: Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Tamrat Endale: Funding acquisition; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Pebalo Francis Pebolo: Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Yolanda R Smith: Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Center for International Reproductive Health Training at the University of Michigan (CIRHT-UM).

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: The search data and strategies can be accessed at https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/8639 There are no materials to make available.

References

- 1. Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Bulenzi-Gulere G, et al. Vulnerability to violence against women or girls during COVID-19 in Uganda. BMC Public Health 2023; 23: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mac-Seing M, Zinszer K, Eryong B, et al. The intersectional jeopardy of disability, gender and sexual and reproductive health: experiences and recommendations of women and men with disabilities in Northern Uganda. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2020; 28: 1772654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Renzaho AMN, Kamara JK, Georgeou N, et al. Sexual, reproductive health needs, and rights of young people in slum areas of Kampala, Uganda: a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0169721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bearak JM, Popinchalk A, Beavin C, et al. Country-specific estimates of unintended pregnancy and abortion incidence: a global comparative analysis of levels in 2015–2019. BMJ Glob Health 2022; 7: e007151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF. 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR245/SR245.pdf (2017, accessed 10 October 2023).

- 6. Nanvubya A, Matovu F, Abaasa A, et al. Abortion and its correlates among female fisherfolk along Lake Victoria in Uganda. J Family Med Prim Care 2021; 10: 3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anguzu G, Flynn A, Musaazi J, et al. Relationship between socioeconomic status and risk of sexually transmitted infections in Uganda: multilevel analysis of a nationally representative survey. Int J STD AIDS 2019; 30: 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masanja V, Wafula ST, Ssekamatte T, et al. Trends and correlates of sexually transmitted infections among sexually active Ugandan female youths: evidence from three demographic and health surveys, 2006–2016. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol 1977; 32: 513–531. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Ann Child Dev 1989; 6: 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. Read Dev Child 1994; 2: 37. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of cognitive. In: College student development and academic life: psychological, intellectual, social, and moral issues. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge, 1997, p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arnott G, Otema C, Obalim G, et al. Human rights-based accountability for sexual and reproductive health and rights in humanitarian settings: findings from a pilot study in northern Uganda. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022; 2: e0000836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akinwale AA. Gender equity and social progress: empowering women and girls to drive sustainable development in Sub–Saharan Africa. Int J Innov Res Adv Stud 2023; 2: 66. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Logie CH. Sexual rights and sexual pleasure: Sustainable Development Goals and the omitted dimensions of the leave no one behind sexual health agenda. Glob Public Health 2023; 18: 1953559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. UNFPA. Sexual & reproductive health. United Nations Population Fund, https://www.unfpa.org/sexual-reproductive-health (2023, accessed 14 August 2023).

- 18. Buser JM, Boyd CJ, Moyer CA, et al. Operationalization of the Ecological Systems Theory to guide the study of cultural practices and beliefs of newborn care in rural Zambia. J Transcult Nurs 2020; 31: 582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lantiere AE, Rojas MA, Bisson C, et al. Men’s involvement in sexual and reproductive health care and decision making in the Philippines: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Mens Health 2022; 16: 155798832211060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho Y-CL, Mahirah D, Ho CZ-H, et al. The role of the family in health promotion: a scoping review of models and mechanisms. Health Promot Int 2022; 37: daac119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Republic of Uganda Ministry of Local Government. Districts, https://molg.go.ug/districts/ (2021, accessed 10 October 2023).

- 23. El Sherif R, Pluye P, Gore G, et al. Performance of a mixed filter to identify relevant studies for mixed studies reviews. J Med Libr Assoc 2016; 104: 47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Slater L. A focused filter to retrieve qualitative studies from the MEDLINE database. Edmonton, AB: John W. Scott Health Sciences Library, University of Alberta, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KdReD-h5NL5pX3vdEsOLxK2VtAsRe8ZM_uzuZPWcitQ/edit?usp=embed_facebook (2017, accessed 9 October 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buser JM, Pebolo PF, August E, et al. Scoping review of qualitative studies on family planning in Uganda. PLOS Glob Public Health 2024; 4: e0003313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rayyan. AI powered tool for systematic literature reviews, https://www.rayyan.ai/ (2021, accessed 25 October 2023).

- 27. CASP. CASP Checklists—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (2018, accessed 9 October 2023).

- 28. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, et al. PRISMA2020: an R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev 2022; 18: e1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buser JM, August E, Rana GK, et al. Scoping review of qualitative studies investigating reproductive health knowledge, attitudes, and practices among men and women across Rwanda. PLoS One 2023; 18: e0283833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grilo SA, Catallozzi M, Heck CJ, et al. Couple perspectives on unintended pregnancy in an area with high HIV prevalence: a qualitative analysis in Rakai, Uganda. Glob Public Health 2018; 13: 1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chi PC, Bulage P, Urdal H, et al. A qualitative study exploring the determinants of maternal health service uptake in post-conflict Burundi and Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muheirwe F, Nuhu S. Are health care facilities and programs in Western Uganda encouraging or discouraging men’s participation in maternal and child health care? Int J Health Plann Manage 2019; 34: 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. De Fouw M, Stroeken Y, Niwagaba B, et al. Involving men in cervical cancer prevention; a qualitative enquiry into male perspectives on screening and HPV vaccination in Mid-Western Uganda. PLoS One 2023; 18: e0280052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ahumuza SE, Matovu JK, Ddamulira JB, et al. Challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services by people with physical disabilities in Kampala, Uganda. Reprod Health 2014; 11: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Annika J, et al. Seeking safety and empathy: adolescent health seeking behavior during pregnancy and early motherhood in central Uganda. J Adolesc 2009; 32: 781–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muyinda H, Nakuya J, Whitworth JAG, et al. Community sex education among adolescents in rural Uganda: utilizing indigenous institutions. AIDS Care 2004; 16: 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Akatukwasa C, Bajunirwe F, Nuwamanya S, et al. Integration of HIV-sexual reproductive health services for young people and the barriers at public health facilities in Mbarara Municipality, Southwestern Uganda: a qualitative assessment. Int J Reprod Med 2019; 2019: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gopal P, Fisher D, Seruwagi G, et al. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: evaluating gaps between policy and practice in Uganda. Reprod Health 2020; 17: 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mathur S, Romo D, Rasmussen M, et al. Re-focusing HIV prevention messages: a qualitative study in rural Uganda. AIDS Res Ther 2016; 13: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nyanzi S, Nyanzi B, Kalina B. Contemporary myths, sexuality misconceptions, information sources, and risk perceptions of Bodabodamen in Southwest Uganda. Sex Roles 2005; 52: 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Orach CG, Musoba N, Byamukama N, et al. Perceptions about human rights, sexual and reproductive health services by internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2009; 9(Suppl 2): S72–S80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yousafzai AK, Edwards K, D’Allesandro C, et al. HIV/AIDS information and services: The situation experienced by adolescents with disabilities in Rwanda and Uganda. Disabil Rehabil 2005; 27: 1357–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allen C, Mbonye M, Seeley J, et al. ABC for people with HIV: responses to sexual behaviour recommendations among people receiving antiretroviral therapy in Jinja, Uganda. Cult Health Sex 2011; 13: 529–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Green EC, Kajubi P, Ruark A, et al. The need to reemphasize behavior change for HIV prevention in Uganda: a qualitative study. Stud Fam Plann 2013; 44: 25–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Joshi A. Multiple sexual partners: perceptions of young men in Uganda. J Health Organ Manag 2010; 24: 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Graffy J, Goodhart C, Sennett K, et al. Young people’s perspectives on the adoption of preventive measures for HIV/AIDS, malaria and family planning in South-West Uganda: focus group study. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kawuma R, Ssemata AS, Bernays S, et al. Women at high risk of HIV-infection in Kampala, Uganda, and their candidacy for PrEP. SSM Popul Health 2021; 13: 100746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kayesu I, Mayanja Y, Nakirijja C, et al. Uptake of and adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women at high risk of HIV-infection in Kampala, Uganda: a qualitative study of experiences, facilitators and barriers. BMC Womens Health 2022; 22: 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mujugira A, Kasiita V, Bagaya M, et al. “You are not a man”: a multi-method study of trans stigma and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among trans men in Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24: e25860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ntozi JP, Mulindwa IN, Ahimbisibwe F, et al. Has the HIV/AIDS epidemic changed sexual behaviour of high risk groups in Uganda? Afr Health Sci 2003; 3: 107–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ashaba S, Zanoni BC, Baguma C, et al. Challenges and fears of adolescents and young adults living with HIV facing transition to adult HIV care. AIDS Behav 2023; 27: 1189–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nabukeera-Barungi N, Nöstlinger C, et al. Sexual risk reduction needs of adolescents living with HIV in a clinical care setting. AIDS Care 2008; 20: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Birungi H, Obare F, Mugisha JF, et al. Preventive service needs of young people perinatally infected with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Care 2009; 21: 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Muhwezi WW, Katahoire AR, Banura C, et al. Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and rural Uganda. Reprod Health 2015; 12: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bwambale MF, Birungi D, Moyer CA, et al. Migration, personal physical safety and economic survival: drivers of risky sexual behaviour among rural–urban migrant street youth in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2022; 22: 1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Choudhry V, Petterson KO, Emmelin M, et al. ‘Relationships on campus are situationships’: a grounded theory study of sexual relationships at a Ugandan university. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0271495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lundberg P, Johansson E, Okello E, et al. Sexual risk behaviours and sexual abuse in persons with severe mental illness in Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2012; 7: e29748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Muhwezi WW, Kinyanda E, Mungherera M, et al. Vulnerability to high risk sexual behaviour (HRSB) following exposure to war trauma as seen in post-conflict communities in Eastern Uganda: a qualitative study. Confl Health 2011; 5: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Miller CL, Bangsberg DR, Tuller DM, et al. Food insecurity and sexual risk in an HIV endemic community in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2011; 15: 1512–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Aluzimbi G, Lubwama G, Muyonga M, et al. HIV testing and risk perceptions: a qualitative analysis of secondary school students in Kampala, Uganda. J Public Health Afr 2017; 8: 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Matovu J, Ssebadduka N. Knowledge, attitudes & barriers to condom use among female sex workers and truck drivers in Uganda: a mixed-methods study. Afr Health Sci 2013; 13: 1027–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wanyenze RK, Atuyambe L, Kibirige V, et al. The new female condom (FC2) in Uganda: perceptions and experiences of users and their sexual partners. Afr J AIDS Res 2011; 10: 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ssebunya R, Matovu JKB. Factors associated with utilization of motorcycle ambulances by pregnant women in rural eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016; 16: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Austin-Evelyn K, Sacks E, Atuyambe L, et al. The promise of Mama Kits: Perceptions of in-kind goods as incentives for facility deliveries in Uganda. Glob Public Health 2017; 12: 565–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gonzaga M. An exploratory study of the views of Ugandan women and health practitioners on the use of sonography to establish fetal sex. Pan Afr Med J 2011; 9: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Scarpa G, Berrang-Ford L, Twesigomwe S, et al. Socio-economic and environmental factors affecting breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices among Batwa and Bakiga communities in south-western Uganda. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022; 2: e0000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Namujju J, Muhindo R, Mselle LT, et al. Childbirth experiences and their derived meaning: a qualitative study among postnatal mothers in Mbale regional referral hospital, Uganda. Reprod Health 2018; 15: 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chemutai V, Nteziyaremye J, Wandabwa GJ. Lived experiences of adolescent mothers attending Mbale Regional Referral Hospital: a phenomenological study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2020; 2020: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kabwigu S, Nsibirano R. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Luuka District, Eastern Uganda: a mixed methods study. Texila Int J Public Health 2022; 10: 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mathur S, Higgins JA, Thummalachetty N, et al. Fatherhood, marriage and HIV risk among young men in rural Uganda. Culture, Health Sex 2016; 18: 538–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kaler A, Alibhai A, Kipp W, et al. Enough children: reproduction, risk and ‘Unmet Need’ among people receiving antiretroviral treatment in Western Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health 2012; 16: 133–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kastner J, Matthews LT, Flavia N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy helps HIV-positive women navigate social expectations for and clinical recommendations against childbearing in Uganda. AIDS Res Treat 2014; 2014: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kisakye P, Akena WO, Kaye DK. Pregnancy decisions among HIV-positive pregnant women in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Cult Health Sex 2010; 12: 445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nobelius A-M, Kalina B, Pool R, et al. Delaying sexual debut amongst out-of-school youth in rural southwest Uganda. Cult Health Sex 2010; 12: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Santelli JS, Mathur S, Song X, et al. Rising school enrollment and declining HIV and pregnancy risk among adolescents in Rakai District, Uganda, 1994–2013. Glob Soc Welf 2015; 2: 87–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chacko S, Kipp W, Laing L, et al. Knowledge of and perceptions about sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy: a qualitative study among adolescent students in Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr 2007; 25: 319–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hennegan J, Dolan C, Steinfield L, et al. A qualitative understanding of the effects of reusable sanitary pads and puberty education: implications for future research and practice. Reprod Health 2017; 14: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Iyer P, Aggleton P. ‘Sex education should be taught, fine. . .but we make sure they control themselves’: teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards young people’s sexual and reproductive health in a Ugandan secondary school. Sex Educ 2013; 13: 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Muhanguzi FK, Ninsiima A. Embracing teen sexuality: Teenagers’ assessment of sexuality education in Uganda. Agenda 2011; 25: 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ndugga P, Kwagala B, Wandera SO, et al. “If your mother does not teach you, the world will. . .”: a qualitative study of parent-adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in Border districts of eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health 2023; 23: 678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pichon M, Howard-Merrill L, Wamoyi J, et al. A qualitative study exploring parent–daughter approaches for communicating about sex and transactional sex in Central Uganda: implications for comprehensive sexuality education interventions. J Adolesc 2022; 94: 880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Råssjö E-B, Kiwanuka R. Views on social and cultural influence on sexuality and sexual health in groups of Ugandan adolescents. Sex Reprod Healthc 2010; 1: 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kasamba N, Kaye DK, Mbalinda SN. Community awareness about risk factors, presentation and prevention and obstetric fistula in Nabitovu village, Iganga district, Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013; 13: 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Waniala I, Nakiseka S, Nambi W, et al. Prevalence, indications, and community perceptions of caesarean section delivery in Ngora District, Eastern Uganda: mixed method study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2020; 2020: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bagenda F, Batwala V, Orach CG, et al. Benefits of and barriers to male involvement in maternal health care in Ibanda District, Southwestern, Uganda. Open J Prev Med 2021; 11: 411–424. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Singh D, Lample M, Earnest J. The involvement of men in maternal health care: cross-sectional, pilot case studies from Maligita and Kibibi, Uganda. Reprod Health 2014; 11: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nobelius A-M, Kalina B, Pool R, et al. Sexual partner types and related sexual health risk among out-of-school adolescents in rural south-west Uganda. AIDS Care 2011; 23: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nalukwago J, Alaii J, Borne BVD, et al. Application of core processes for understanding multiple concurrent sexual partnerships among adolescents in Uganda. Front Public Health 2018; 6: 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Mbonye M, Siu GE, Kiwanuka T, et al. Relationship dynamics and sexual risk behaviour of male partners of female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res 2016; 15: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mbonye M, Siu G, Seeley J. Marginal men, respectable masculinity and access to HIV services through intimate relationships with female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Soc Sci Med 2022; 296: 114742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Schmidt-Sane MM. Provider love in an informal settlement: men’s relationships with providing women and implications for HIV in Kampala, Uganda. Soc Sci Med 2021; 276: 113847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mujugira A, Nakyanzi A, Kasiita V, et al. HIV self-testing and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis are empowering for sex workers and their intimate partners: a qualitative study in Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24: e25782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nyanzi B, Nyanzi S, Wolff B, et al. Money, men and markets: Economic and sexual empowerment of market women in southwestern Uganda. Cult Health Sex 2005; 7: 13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. King R, Kim J, Nanfuka M, et al. “I Do Not Take My Medicine while Hiding”—a longitudinal qualitative assessment of HIV discordant couples’ beliefs in discordance and ART as prevention in Uganda. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0169088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nakku-Joloba E, Pisarski EE, Wyatt MA, et al. Beyond HIV prevention: everyday life priorities and demand for PrEP among Ugandan HIV serodiscordant couples. J Intern AIDS Soc 2019; 22: e25225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Matovu JKB, R Kisa, Malek AM, et al. Coping mechanisms of previously diagnosed and new HIV-discordant, heterosexual couples enrolled in a pilot HIV self-testing intervention trial in central Uganda. Front Reprod Health 2021; 3: 700850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Tusiime S, Musinguzi G, Tinkitina B, et al. Prevalence of sexual coercion and its association with unwanted pregnancies among young pregnant females in Kampala, Uganda: a facility based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2015; 15: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wagman J, Baumgartner JN, Waszak Geary C, et al. Experiences of sexual coercion among adolescent women: qualitative findings from Rakai District, Uganda. J Interpers Violence 2009; 24: 2073–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Birungi R, Nabembezi D, Kiwanuka J, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of sexual coercion in Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res 2011; 10: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kyegombe N, Meiksin R, Wamoyi J, et al. Sexual health of adolescent girls and young women in Central Uganda: exploring perceived coercive aspects of transactional sex. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2020; 28: 1700770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Achora S, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Akpor OA, et al. Perceptions of adolescents and teachers on school-based sexuality education in rural primary schools in Uganda. Sex Reprod Healthc 2018; 17: 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Råssjö E-B, Darj E. “Safe sex advice is good—but so difficult to follow”. Views and experiences of the youth in a health centre in Kampala. Afr Health Sci 2002; 2: 107–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Miller AN, Nalugya E, Gabolya C, et al. Ugandan adolescents’ sources, interpretation and evaluation of sexual content in entertainment media programming. Sex Educ 2016; 16: 707–720. [Google Scholar]

- 105. McGranahan M, Bruno-McClung E, Nakyeyune J, et al. Realising sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls and young women living in slums in Uganda: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 2021; 18: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nobelius A-M, Kalina B, Pool R, et al. Sexual and reproductive health information sources preferred by out-of-school adolescents in rural southwest Uganda. Sex Educ 2010; 10: 91–107. [Google Scholar]