Abstract

Prisons, due to various risk factors, are environments that are conducive to infectious disease transmission, with significantly higher prevalence of infectious diseases within prisons compared to the general population. This underscores the importance of preventive measures, particularly vaccination. As part of the international project “Reaching the hard-to-reach: Increasing access and vaccine uptake among the prison population in Europe” (RISE-Vac), this study aimed to map the availability and delivery framework of vaccination services in prisons across Europe and beyond. A questionnaire designed to collect data on the availability and delivery model of vaccination services in prisons was validated and uploaded in SurveyMonkey in July 2023. Then, it was submitted to potential participants, with at least one representative from each European country. Potential participants emailed an invitation letter by the RISE-Vac partners and by the European Organization of Prison and Correctional Services (EUROPRIS). Twenty European countries responded. Vaccines are available in European countries, although their availability differs by country and type of vaccine. The first dose is offered to people living in prisons (PLP), mostly within one month, COVID-19 is the most widely offered vaccine. In all countries, vaccines are actively offered by healthcare workers; in most countries, there is no evaluation of vaccination status among people who work in prison. The survey shows variance in vaccine availability for PLP and staff across countries and vaccine types. Quality healthcare in prisons is not only a matter of the right to health but also a critical public health investment: enhancing vaccine uptake consistently among PLP and staff should be prioritized.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20207-3.

Keywords: Vaccination, Immunization, Prevention, Infectious diseases, Prisons

Introduction

Prisons and other places of detention are environments that are conducive to the transmission of infectious diseases among people who live and work there. This is attributed to various risk factors, with environmental, individual, and organizational factors being the primary contributors. Firstly, many prisons face environmental challenges, including overcrowding and inadequate ventilation, which can facilitate infection transmission [1]. Secondly, people living in prisons (PLP) are often more likely to engage in risk behaviors compared to the general population, primarily due to diminished risk perception [2]. Thirdly, a large proportion of PLP lack access to proper healthcare services in prisons, either due to the unavailability of such services or a shortage of healthcare providers [3]. These risk factors explain the heightened vulnerability of the prison population to infectious diseases.

Numerous outbreaks of infectious diseases have been documented in prison settings worldwide, resulting in significant incidence and mortality among PLP. In the United States, for example, from April 2020 to April 2021, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic alone resulted in over 394,000 new infections and 2,555 deaths, for a cumulative incidence rate of 30,780 per 100,000 persons [4]. At the same time, the standardized mortality rate for PLP stood at 199.6 per 100,000, which was 2.5 times higher than that of the general population in the US [4]. The issue of infectious disease outbreaks in correctional facilities, however, is not limited to COVID-19 but extends to a broad spectrum of infectious diseases, including viral hepatitis, influenza, measles, and many other diseases.

There are various strategies and interventions aimed at controlling infection transmission within prison settings [5], among them vaccination stands out as one of the most effective and cost-efficient approaches. However, there is a scarcity of data regarding the availability, accessibility, and delivery models of vaccination services within prisons, often accompanied by concerns about their quality [6]. The existing evidence suggests that only a few countries across the globe provide vaccination services within prison facilities, and these services are predominantly activated as a response to healthcare crises, such as pandemics, epidemics, and local outbreaks [6, 7]. Moreover, the interventions to enhance vaccine uptake among PLP and staff members are few and far between, with a predominant focus on disseminating knowledge and raising awareness [8–10]. Despite these efforts, several obstacles, both at the level of the individual and organizations persist, hindering access to vaccines among people who live and work in prisons [5].

The objective of this study is to map the availability and delivery framework of vaccination services in prisons across Europe as part of the “Reaching the hard-to-reach: Increasing access and vaccine uptake among the prison population in Europe” (RISE-Vac) project.

Materials and methods

RISE-Vac

This work was developed as part of the RISE-Vac project, co-funded by the European Union’s 3rd Health Program (2014–2020) under grant agreement No 101,018,353. The RISE-Vac project aims to improve the state of healthcare in European prisons by promoting vaccine literacy, enhancing vaccine offer and increasing vaccine uptake among people who live and work within European prisons. The project’s consortium consists of nine international partners from six European countries, including Cyprus, France, Germany, Italy, Moldova, and the UK. The project can also boast an international advisory board full of the leading lights of prison health research. More information regarding the project can be found on the project’s website (https://wephren.tghn.org/rise-vac/).

Procedure

This survey was one of the activities defined within the RISE-Vac work package oriented to promote evidence-informed policies for prison health systems. A questionnaire on vaccine offering was designed by the researchers and sent to the consortium and advisory board members of the project for review to ensure its internal and external validity. The questionnaire was revised based on the reviewers’ comments and uploaded to the SurveyMonkey platform (https://it.surveymonkey.com) in July 2023. Potential participants were invited through an invitation letter emailed by the RISE-Vac partners as well as by the EUROPRIS to their network members with assistance from the experts of the EUDA. Senior technical staff (one per country) from either the Ministry of Justice or the Ministry of Health, depending on the specific organizational structure of the country, were invited to complete the survey. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Participants received an invitation letter detailing the purpose of the RISE-Vac project, the survey procedures, and assurances of data confidentiality and exclusive use for the project’s objectives. Participation was voluntary.

Scope

Key figures from 24 countries in three continents, namely Africa, Asia, and Europe responded to our survey. These countries include Belgium (Total prison population, including pre trial detainees and remand prisoners [11]: 12,316; imprisonment rate per 100,00011: 104), Croatia (4,073; 106), Cyprus (947; 103), England (87,699; 145), Finland (2,839; 51), France (75,897; 111), Ghana (14,991; 45), Ireland (1,887; 98), Italy (61,049; 104), Latvia (3,229; 172), Luxembourg (705; 107), Malta (690; 132), Moldova (6,084; 236), Nepal (27,550; 90), Netherlands (11,447; 65), Nigeria (77,934; 34), Norway (3,076; 56), Portugal (12,272; 117), Romania (23,608; 124), Slovakia (9,717; 179), Spain (54,197; 113), Sweden (8,635; 82), Uganda (75,764; 150), and Ukraine (48,038; 123).

Survey

The questionnaire consisted of 17 questions divided into three main sections. Section I comprised questions on the participant’s contact name and information; availability of national and subnational guidelines on implementing vaccination in prisons; vaccinations offered to PLP; when, to whom and how these vaccinations are offered; barriers to implementing vaccination and vaccine uptake by PLP; and the strategies and interventions implemented to overcome these obstacles at a national level. Section II aimed to collect information on vaccination for prison staff members. The questions addressed whether and when the vaccination status of the prison staff members is checked; either routine assessment of vaccine-preventable diseases among prison staff members is in place; what the main barriers towards vaccine uptake among prison staff members are; and which strategies and interventions are implemented to overcome these obstacles. Section III assessed the state of availability, accessibility, and model of delivery of services at the prison level (optional; recommended in case national data were not available). The complete questionnaire is available in Appendix 1.

Ethical aspects

The survey was conducted considering all the ethical aspects of research in biomedical sciences. As mentioned in the invitation letter, participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and the participants were assured that their personal data (e.g., their name and contact information) would remain confidential. In addition to the considerations above, the RISE-Vac has been approved by the ethics committee of the University of Pisa (approval number: 0049433/2022).

Data extraction and analysis

The reported data, aggregated from the SurveyMonkey platform, or received directly via email from the participants, were collated in January 2024. The extracted data were collated, categorized and reported descriptively.

Results

The survey participants, delegates from the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Justice, represented 20 European countries including Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, England, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Republic of Moldova (Moldova), the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain (Catalonia), Sweden, and Ukraine.

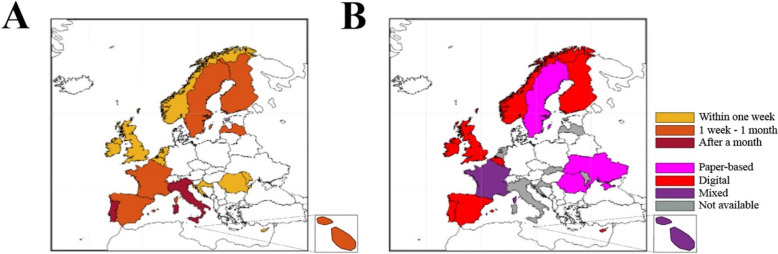

Vaccination services for PLP

In European countries, the first dose or only dose of vaccines is offered to PLP within one week (6/20), between one week and a month (10/20) and after one month (2/20) from prison entrance. These data are depicted in Fig. 1A. Slovakia declared that vaccinations are suggested by medical staff during the medical examination according to the calendar specified in the Slovak Republic Ministry of Health Decree 585/2008. No data about time of vaccination offering has been reported by Ukraine.

Fig. 1.

Geographic representation of the data collected in Q4 and Q11. A 1st dose/only dose timing in PLP. B Characteristics of the immunization information system (IIS)

Table 1 summarizes the vaccinations offered to PLP, described in detail in the following subparagraphs. Overall, the COVID-19 vaccination is the most offered vaccine in prison (100%). It is followed by influenza (Flu:95%), Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)/Diphtheria, Tetanus and Pertussis (DTP) (85%), Hepatitis A Virus (HAV:75%), Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR)/Pneumococcal (70%), Human Papillomavirus (HPV: 60%), Monkeypox (50%), Herpes Zoster (45%) and Meningococcal (30%) vaccinations.

Table 1.

Vaccinations offered to PLP. The different symbols refer to whom the vaccinations are offered (✔: no specification to whom; ●: all PLP; ■: specific age group; ▲: high-risk groups; ▼: PLP with comorbidities)

| Country | COVID-19 | Flu | HBV | DTP | HAV | MMR | Pneumococcal | HPV | Monkeypox | Herpes Zoster | Meningococcal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | ■ | ▼ | ✔ | ● | ▲ | ▲ | ✔ | ▲ | ▼ | ||

| Cyprus | ● | ● | ● | ● | ▲▼ | ▲ | |||||

| Croatia | ● | ● | ■▲▼ | ▲▼ | ▲▼ | ■▲▼ | |||||

| England | ■ | ■ | ● | ● | ▲ | ● | ■▲ | ■ | ▲ | ■ | ■ |

| Finland | ● | ● | ● | ▲ | ● | ▲ | ■▲▼ | ■ | ▲ | ▲ | |

| France | ● | ■ | ● | ● | ▲ | ● | ■▲ | ▲ | ● | ||

| Ireland | ■▲▼ | ■▲▼ | ✔ | ● | ● | ● | ✔ | ● | ▲ | ▲ | |

| Italy | ● | ● | ● | ■▲ | ▲ | ■ | ■▲ | ■▲▼ | ▲ | ■▲ | ▲ |

| Latvia | ● | ■▲▼ | ● | ||||||||

| Luxemburg | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ■▲▼ | ■ | ▲▼ | ● | ■ |

| Malta | ● | ● | ● | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ||||

| Moldova | ● | ▲▼ | ● | ● | |||||||

| Netherlands | ■▼ | ▼ | ▲▼ | ■ | ▲ | ■ | ■▼ | ■ | ▲ | ||

| Norway | ● | ● | ● | ● | ▲▼ | ● | ● | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ● |

| Portugal | ● | ● | ✔ | ● | ● | ● | ■▲ | ▼ | ▼ | ||

| Romania | ● | ■▲▼ | |||||||||

| Slovakia | ● | ■▲ | ● | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||

| Spain (Catalonia) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ■▲ | ▲ | ■ | ||

| Sweden | ■▲▼ | ■▲▼ | ● | ● | ■▲▼ | ● | ■▲▼ | ||||

| Ukraine | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

COVID-19

COVID-19 vaccination is offered in all the countries surveyed. Specifically, it is either offered to everyone (14/20) or only to specific age groups (2/20). Moreover, one country offers COVID-19 vaccination to PLP with comorbidities and/or at specific age, while two countries offer it to all categories (specific age groups, vulnerable groups). Data on COVID-19 vaccination in Ukraine are missing.

Flu

Influenza vaccines are offered in 19/20 European countries; 9 of the 19 countries offer this vaccination to everyone, 2/19 countries offer it only to PLP of a specific age, and 2/19 countries offer it only to PLP with comorbidities. In addition, 1/19 countries offers vaccination to PLP of a specific age and/or at high-risk, while Moldova offers it to PLP at high-risk and/or with comorbidities. 4/19 countries offer influenza vaccination to PLP in all these categories.

HBV

HBV vaccines are offered in 18/24 countries surveyed (EU: 17/20; non-EU: 1/4). As shown in Table 1, 11 out of the 17 European countries offer HBV vaccination to all PLP, 1/17 to PLP of specific age groups, of high-risk groups and/or with comorbidities and 1/17 to PLP of high-risk groups and/or with comorbidities. Of the remaining 4/17 countries, information about whom HBV vaccinations are offered is unavailable.

DTP

DTP vaccination is offered in 17/20 European countries. It is offered to everyone (12/17) or only to PLP with specific age (1/17) or only to PLP of high-risk groups (2/17). Conversely, 1/17 countries offers it to PLP of high-risk groups and/or with specific age. Ukraine offers DTP vaccines, but the information related to the target population is unavailable.

HAV

Vaccination is only offered in 15/20 European countries. It is offered in 6/15 countries to all PLP, 7/15 countries only to PLP in high-risk groups, and 2/15 countries to PLP in high-risk groups and/or with comorbidities.

MMR

MMR vaccination is offered to PLP in 14/20 European countries. 6 out of 14 countries offer it to everyone, 2/14 countries offer it only to PLP with specific age and 4/14 offer it only to PLP in high-risk groups. Conversely, 1/14 countries offers it to PLP in high-risk groups and/or with comorbidities. Ukraine offers MMR vaccines, but no information is available about the target population.

Pneumococcal disease

Pneumococcal vaccination is offered in 14/20 European countries. In 2/14 countries, information on its distribution is not available. In 2/14 countries it is offered to everyone, and in 1/14 countries only to high-risk groups. In 4/14 countries, this vaccination is proposed to PLP: (I) belonging to high-risk groups; (II) with specific age; (III) with comorbidities. In 3/14 countries, this vaccination is proposed to PLP: (I) belonging to high-risk groups; (II) with specific age. In one of fourteen countries, this vaccination is offered to PLP: (I) belonging to high-risk groups; (II) with comorbidities. Similarly, 1/14 countries offers the vaccine to PLP: (I) with specific age; (II) with comorbidities.

HPV

HPV vaccination is offered to PLP in 12/20 European countries. It is offered to everyone in 2/12 countries, or only to PLP of certain ages in 4/12 countries or only to high-risk groups in 3/12 countries. 2 out of 12 countries offer HPV vaccination to PLP: (I) belonging to high-risk groups; (II) with specific age.

Monkeypox

Monkeypox vaccination is offered in 10/20 European countries. It is offered only to PLP from high-risk groups in 7/10 and to PLP with comorbidities in 2/10 countries. 1/10 offers vaccination to both aforementioned categories.

Herpes zoster

Herpes Zoster vaccination is offered in 9/20 European countries. Notably, it is offered to everyone in 1/9 countries, only to specific age groups in 2/9, to high-risk groups in 4/9, or to PLP with comorbidities in 1/9 countries. Moreover, it is also offered to PLP in specific age groups and/or high-risk groups in 1/9 countries.

Meningococcal disease

Meningococcal vaccination is offered in 6/20 European countries. In 2/6 countries, it is offered to everyone. Furthermore, 2/6 and 1/6 offer this vaccination only to PLP of specific age or only to PLP of high-risk groups, respectively. 1/6 offer it to PLP of all above-mentioned categories.

Other preventable diseases

As far as other vaccinations are concerned, varicella and polio vaccines are offered to all PLP by Luxemburg, whereas tuberculosis vaccines are offered by France (PLP with comorbidities) and Cyprus.

In 17 out of 20 European countries, these vaccinations are actively offered to PLP only by healthcare workers. Latvia and Slovakia offer vaccinations through healthcare workers and on request by PLP, while Cyprus offers vaccinations only upon PLP request. After release from prison, a follow-up program exists in 8 out of 20 European countries (Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain (Catalonia) and Slovakia).

The doses of vaccine administered are usually recorded in the Immunization Information Systems (IIS), available in 14/20 European countries (3/14: paper-based, 8/14: electronic format; 3/14: mixed electronic/paper formats). These data are shown in Fig. 1B.

Implementation of the vaccination programs

National/subnational guidelines on the implementation of vaccination services in prison exist in 15/20 European countries (Belgium, Cyprus, England, France, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Spain (Catalonia), Slovakia, Sweden, Ukraine).

In surveyed countries, vaccination programs are implemented only by healthcare staff members in 15/20 countries (Belgium, England, Finland, France, Italy, Ireland, Luxemburg, Malta, Moldova, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain (Catalonia), Sweden and Slovakia) or by the cooperation between the healthcare staff with the community health system (4/20: Cyprus, Croatia, Norway, Ukraine) or with the custodial staff (1/20: Latvia).

Table 2 summarizes the infrastructural barriers to vaccination implementation, the main barriers to vaccine uptake among PLPs and the main strategies/interventions to address them. 10/20 countries reported no infrastructural barriers and 2/20 of them also reported no obstacles to PLP vaccine uptake. As barriers to vaccination uptake, the Netherlands, and Ukraine also reported a lack of interest, knowledge and risk perception, refusal of vaccination, and lack of government/NGOs provision for regular vaccination among PLP. Regarding strategies and interventions to increase vaccine uptake, the Netherlands reported that physicians offer vaccinations if there is an indication.

Table 2.

Vaccination implementation and uptake among PLP: barriers and strategies/interventions

| Country | Infrastructural barriers | Vaccine uptake: main barriers | Strategies and interventions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of budget | Lack of Human Resources | Vaccine Shortage | Store Vaccines: lack of quipment | Lack of knowledge/Misinformation | Conspiracy Theory/Misbeliefs | Distrust in Prison Authorities | Vaccines are not free of charge | Knowledge dissemination | Peer-education | Question/Answer sessions with experts | Active recommendation of vaccines/Opt-out programs | |

| Belgium | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Cyprus | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Croatia | No Barriers | No Barriers | ||||||||||

| England | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Finland | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| France | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Ireland | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Italy | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Latvia | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Luxemburg | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Malta | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Moldova | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Netherlands | No Barriers | ● | Healthcare staff offer vaccination based on clinical indications | |||||||||

| Norway | No Barriers | No Barriers | ||||||||||

| Portugal | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Romania | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Slovakia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Spain (Catalonia) | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Sweden | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Ukraine | No Barriers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

Vaccination status of staff members

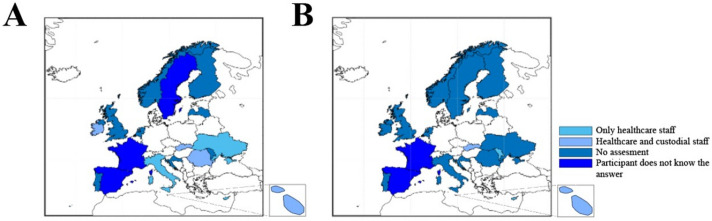

Figure 2 depicts the state of evaluation of the vaccination status before (Fig. 2A) and after (Fig. 2B) the employment of staff members in surveyed countries.

Fig. 2.

Geographic/bar representation of the data collected in Q12, Q13 and Q14. A Checking of the vaccination status of prison staff members before employment. B Checking of the vaccination status of prison staff members regularly after employment

Among prison staff members, HBV is the most frequently vaccine-preventable disease assessed regularly (38.89%), followed by Flu/COVID-19 (27.78%), and DTP (16.67%). Overall, 61.11% of countries reported not conducting any routine evaluation among prison staff members. No information was available for Sweden and Ukraine Table 3.

Table 3.

Routine assessment of vaccine-preventable diseases among European prison staff members

| Country | Pneumonia | VZV | MMR | HBV | DTP | Flu/COVID-19 | No Routine Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | ● | ||||||

| Cyprus | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Croatia | ● | ● | |||||

| England | ● | ● | |||||

| Finland | ● | ||||||

| France | ● | ||||||

| Ireland | ● | ||||||

| Italy | ● | ||||||

| Latvia | ● | ||||||

| Luxemburg | ● | ● | |||||

| Malta | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Moldova | ● | ||||||

| Netherlands | ● | ||||||

| Norway | ● | ||||||

| Portugal | ● | ||||||

| Romania | ● | ||||||

| Slovakia | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Spain (Catalonia) | ● | ||||||

| Sweden | Not specified | ||||||

| Ukraine | Not specified | ||||||

Table 4 breaks down the main barriers related to vaccine uptake among staff members. Lack of knowledge/misinformation, conspiracy theory/misbelief and costs of vaccines were mentioned in 10/20, 6/20 and 2/20 European countries, respectively. One country (the Netherlands) declared the absence of interest from staff members, and the absence of barriers was reported by five European countries (Belgium, England, Luxemburg, Norway, and Romania). Ukraine identifies barriers other than those described above, but no details are available Considering only the countries where barriers were identified, the approaches used to facilitate vaccine uptake among staff members are knowledge dissemination (in 10/15 countries), peer education (2/15), question-and-answer sessions with experts (3/15) and active recommendation of vaccines/opt-out programs (9/15) (Table 4). Moreover, the Netherlands did not report any strategies, and Sweden uses online information from national health authorities.

Table 4.

Reported barriers on the vaccine uptake (on the left) among European prison staff members, and strategies and intervention suggested (on the right)

| Country | Vaccine uptake: main barriers | Strategies and Interventions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of knowledge/Misinformation | Conspiracy Theory/Misbeliefs | Vaccines are not free of charge | Knowledge dissemination | Peer-education | Question/Answer sessions with experts | Active recommendation of vaccines/Opt-out programs | Other | |

| Belgium | No Barriers | |||||||

| Cyprus | ● | ● | ||||||

| Croatia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| England | No Barriers | |||||||

| Finland | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| France | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Ireland | ● | ● | ||||||

| Italy | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Latvia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Luxemburg | No Barriers | |||||||

| Malta | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Moldova | ● | ● | ||||||

| Netherlands | No interest, lack of risk perception | ● | ||||||

| Norway | No Barriers | |||||||

| Portugal | ● | ● | ||||||

| Romania | No Barriers | |||||||

| Slovakia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Spain (Catalonia) | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Sweden | ● | ● | ||||||

| Ukraine | ● | |||||||

Prison facilities providing vaccination services

Since no information is available from Belgium, 17/19of the respondents work for prisons providing vaccination services. The vaccinations offered to PLP are illustrated in Table 5. Vaccinations against influenza (16/17), COVID-19 (16/17), HBV (15/17) and pneumococcal (14/17) infections are the main offered.

Table 5.

Prison vaccination services and vaccinations offered to PLP

| Country | Seasonal Vaccinations/Vaccination during outbreak | Childhood Life-Course Vaccinations/Booster doses | Cancer Preventable Vaccination | Fragile population | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flu | COVID-19 | DTP | MMR | Meningococcal | HAV | HBV | HPV | Pneumococcal | Hib | VZV | |

| Cyprus | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Croatia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| England | ● | ● | It should be offered but, in practice, varies by prison | ● | It should be offered but, in practice, varies by prison | ● | It should be offered but, in practice, varies by prison | ||||

| Finland | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| France | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Ireland | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Italy | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Latvia | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Luxemburg | ● | ● | ● | ● |

● In progress |

● | ● |

● In progress |

● |

● In progress |

● |

| Malta | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Moldova | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Netherlands | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Norway | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Portugal | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Slovakia | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

|

Spain (Catalonia) |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Sweden | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

Discussion and conclusions

A total of 20 European countries responded to our survey. According to the results, the first dose/only dose of vaccines is offered to PLP mainly between one week and a month from prison entrance. COVID-19 is the most widely offered vaccine in prisons in European countries. In 17/20 respondent countries, vaccines are actively offered to PLP by healthcare workers. After release from prison, a follow-up program exists in only 8/20.

In Europe, 10/20 countries reported no infrastructural barriers to implementing vaccination services. Regarding vaccine uptake, the main barrier was “Lack of knowledge/Misinformation”.; Active recommendation of vaccines (opt-out programs) was reported as the primary strategy to increase vaccine uptake in prisons.

Vaccine hesitancy is one of the most critical obstacles to controlling vaccine-preventable diseases in prisons [12]. People living in prisons may refuse vaccination for various reasons, including but not limited to concerns about side effects [12], low levels of perceived risk [13], distrust of authorities, vaccine, or vaccinator [14], or even pain from the needle [12]. These reasons highlight the need for scaling up a strong information, education and communication (IEC) system before or in parallel with the vaccination programs, focusing on risk. Working closely with external players, including NGOs and people with lived experience of incarceration, to provide IEC about the target vaccines and infectious diseases can help improve vaccine knowledge and help tackle vaccine hesitancy in prisons. In some countries, however, “criminal background checks” are a requirement for entering prisons, hindering the provision of services via people with lived experience of imprisonment [10].

In addition to the aforementioned personal barriers, the lack of vaccine uptake in prisons may be due to the unavailability of vaccines or vaccination programs. High turnover of PLP [15], divergent organizational cultures and priorities in prisons and community health systems [10], lack of equipment to maintain cold chain, and the need to provide advanced notice to prison authorities [13] are among the environmental, infrastructural, and policy-related issues resulting in the lack of vaccination services and vaccine uptake in prisons reported in the literature. According to the UN’s Mandela Rules, the state is responsible for ensuring that PLP are provided with healthcare services at least equivalent to that available in the community [16]. Hence, states are responsible for ensuring that vaccination services are in place in prisons, that are at least equivalent to the vaccination services available for the general population.

As mentioned previously, the protection of people living in prisons’ health worldwide is the responsibility of various organizations, including ministries of health and/or justice, national health services, or multiple organizations [17]. The growing integration of prison health with public health services in recent years has been an attempt to improve the quality of healthcare services, respond to the shortage of prison staff members, address threats to the professional role of healthcare staff members, and acknowledge the human rights of people living in prisons [18]. This change started following the recommendations by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) that public health services take responsibility for prison health [19]. Nevertheless, data on the impact of governance arrangements on health outcomes of PLP are limited and do not lead to clear conclusions [17]. Regardless of which organization is responsible for providing healthcare services in prisons, efforts should be undertaken to ensure the availability, accessibility and quality of vaccination programs for all people who live and work in prisons and continuity of care after release.

Due to numerous infrastructural and behavioral factors, people in prisons are at greater risk of acquiring and transmitting a number of infectious diseases, including COVID-19 [20]. Hence, at the beginning of the current COVID-19 pandemic, a large number of specialists tried to draw the attention of prison health policymakers to the potential threats of the pandemic in prisons in order to take immediate preventive actions [21, 22]. Accordingly, many countries undertook preventive actions, including developing guidelines, reducing the prison population, providing protective equipment and materials, e.g., masks and disinfectants, and scaling up vaccination programs. In the countries offering COVID-19 vaccines in prisons, vaccination plans varied from those which have explicitly prioritized PLP and prison staff members as a higher-risk group to the countries which have not explicitly referred to the prison populations in their national vaccination programs [23]. Although the prioritization of PLP in national vaccination programs was not assessed in our survey, COVID-19 vaccines were available to all people who lived and worked in all surveyed prisons, which is a great achievement for the healthcare systems of these countries. On the other hand, the lack of availability of the other vaccines — in particular hepatitis A, meningococcal disease, and herpes — in the surveyed prisons is a serious cause for public health concern that needs to be addressed as soon as possible.

Limitations of the study

This study represents the first attempt to provide an overview of vaccination services offered in prisons across twenty European countries. While the selection of participants was carefully linked to specific regions or countries, limitations emerged due to varying availability and quality of the information provided.One such limitation was the restricted number of countries participating in our survey. Despite our efforts to engage a broader range of respondents and incorporate more countries, we could only solicit responses from 20 European countries. Another limitation was the possible lack of uniformity in the method of assessing vaccination status across different countries, as it was not possible to collect the specific methods used, which may have included self-assessment, incomplete vaccination records, or serological testing. Future research should aim to address these gaps by expanding participant selection criteria and focusing on more detailed data collection, to build a more comprehensive understanding of vaccination practices in correctional facilities.

The absence of data from Germany, a partner country in RISE-Vac, posed another limitation to our survey. While we managed to gather data from two prisons in two distinct states (Bundesländer) within Germany, these findings were not representative of the entire nation and were consequently excluded. In Germany, the provision of healthcare to incarcerated individuals is a state responsibility. This decentralized approach results in variations in healthcare policies across the 16 different states of Germany, including vaccination services available in prisons in this country.

Recommendations

Drawing on the findings, the following recommendations will assist prison health policymakers and healthcare providers in implementing effective vaccination programs for people who live and work in prisons:

Healthcare and custodial staff members can act as vehicles to transmit infectious diseases from outside into prisons and vice versa; therefore, special attention should be paid to the implementation of vaccination programs, regular assessment of vaccination status, as well as tackling vaccine refusal among this critical population. Although the availability and comprehensive coverage of vaccination programs against COVID-19 in prisons is an outstanding achievement, the current pandemic should not distract prison health systems from the other vaccine-preventable diseases in prisons.

Lack of information is a primary barrier to the surveillance of diseases and the assessment of the effectiveness of interventions (e.g., vaccination programs in prisons). Prison policymakers should enable and support scientists in conducting research on vaccinations within prisons. This will provide essential evidence on various aspects of vaccine use and effectiveness, aiming to address existing gaps and reduce the impact of vaccine-preventable diseases in prison populations.

Vaccine refusal is a common challenge for health systems in the community and prisons. A robust information, education and risk communication system in prisons before implementation or in parallel with vaccination services can help deal with this crucial issue and enhance vaccine uptake among people who live and work in prisons.

Distrust of prison authorities is one of the main reasons for the lack of service uptake in specific vaccination services among PLP. Taking on board external players, including NGOs and people with lived experience of imprisonment as service providers, is recommended to build trust and improve vaccine uptake among people in prisons.

For vaccines with more than one required dose, the course of vaccination is interrupted if PLP get released to the community before receiving boosters. This issue highlights the importance of scaling up and strengthening the immunization information systems to ensure vaccination completion among PLP after release.

The experience accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic is an invaluable asset that should be used to set up and expand preventive activities against infection transmission in prisons in the future.

Conclusions

We surveyed 20 European countries to assess the vaccine delivery models and reveal the gaps in the existing programs in prisons in Europe and abroad. According to the results, the availability of vaccines for PLP and prison staff members varies widely by country, setting, and type of vaccine. Initiating HBV vaccination program with support from the RISE-Vac project in Moldova is a good example, highlighting the importance of support from external players in providing evidence-based interventions in prisons. In addition, the lack of information on various aspects of vaccination in prisons is an obstacle to evaluating the efficacy, efficiency and effectiveness of the program in the target institutions. In conclusion, prisons offer a distinct opportunity to deliver services to vulnerable populations who often find these services hard to access in the community. Since the majority of PLP will return to the community, vaccination in prison should be considered a public health investment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The content of this manuscript represents the views of the authors only and is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. We would like to acknowledge the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA) and the European Organisation of Prison and Correctional Services (EuroPris) for their support and collaboration in this research. Their contributions and resources were essential to the completion of this study.

Disclaimer

The content of this manuscript represents the views of the authors only and is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Abbreviations

- PLP

People Living in Prisons

- EUDA

European Union Drugs Agency

- EUROPRIS

European Organization of Prison and Correctional Services

- HBV

Hepatitis B Virus

- DTP

Diphtheria Tetanus and Pertussis

- HAV

Hepatitis A Virus

- Hib

Haemophilus influenzae type B

- MMR

Measles Mumps and Rubella

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

- VZV

Varicella Zoster Virus

- COVID

19-Coronavirus Disease 2019

- NGOs

Non-Governmental Organizations

- IEC

Information, Education, and Communication

- UNODC

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- WHO

World Health Organization

- IIS

Immunization Information Systems

Authors' contributions

B.M. and M.P.T.F. have contributed equally to this manuscript. B.M., E.D.V., M.P.T. F., and L.T. contributed to the design and implementation of the research. D.P. and B.M. draft the survey. M.P.T.F. and E.D.V. were responsible for data collection and data analysis. M.P.T. F. was responsible for data visualisation. B.M., E.D.V., and M.P.T. F. wrote the main manuscript text. I.B., R.R., N.C., A.M. H.S., L.B., E.D.V. and L.T. reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was developed as part of the RISE-Vac project, co-funded by the European Union’s 3rd Health Program (2014–2020) under grant agreement No 101018353.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information (Appendix 1).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The RISE-Vac project has been approved by the ethics committee of the University of Pisa (approval number: 0049433/2022).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Babak Moazen and Maria Tramonti Fantozzi contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.MacDonald M. Overcrowding and its impact on prison conditions and health. Int J Prison Health. 2018;14(2):65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moazen B, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Silbernagl MA, Lotfizadeh M, Bosworth RJ, Alammehrjerdi Z, Kinner SA, Wirtz AL, Bärnighausen TW, Stöver HJ, Dolan KA. Prevalence of drug injection, sexual activity, tattooing, and piercing among prison inmates. Epidemiol Rev. 2018;40(1):58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamarulzaman A, Reid SE, Schwitters A, Wiessing L, El-Bassel N, Dolan K, Moazen B, Wirtz AL, Verster A, Altice FL. Prevention of transmission of HIV, Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in prisoners. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquez N, Ward JA, Parish K, Saloner B, Dolovich S. COVID-19 incidence and mortality in federal and state prisons compared with the US Population, April 5, 2020, to April 3, 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1865–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moazen B, Agbaria N, Ismail N, Mazzilli S, Klankwarth UB, Amaya A, Rosello A, D’Arcy J, Plugge E, Stöver H, Tavoschi L. Interventions to increase vaccine uptake among people who live and work in prisons: a global multistage scoping review. J Community Psychol. 2023;1–17. 10.1002/jcop.23077. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Moazen B, Ismail N, Agbaria N, Mazzilli S, Petri D, Amaya A, D’Arcy J, Plugge E, Tavoschi L, Stöver H. Vaccination against emerging and reemerging infectious diseases in places of detention: a global multistage scoping review. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1323195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madeddu G, Vroling H, Oordt-Speets A, Babudieri S, O’Moore É, Noordegraaf MV, Monarca R, Lopalco PL, Hedrich D, Tavoschi L. Vaccinations in prison settings: a systematic review to assess the situation in EU/EEA countries and in other high income countries. Vaccine. 2019;37(35):4906–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison M, Musser B, Satterwhite C, Ault K, Kelly P, Ramaswamy M. Human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge and intention among adult inmates in Kansas, 2016–2017. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(8):1000–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berk J, Murphy M, Kane K, Chan P, Rich J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Initial SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Uptake in a correctional Setting: cross-sectional study. JMIRx Med. 2021;2(3):e30176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerson A, Allison M, Kelly PJ, Ramaswamy M. Barriers and facilitators of implementing a collaborative HPV vaccine program in an incarcerated population: a case study. Vaccine. 2020;38(11):2566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fair H, Walmsley R. World prison population list fourteenth edition. May 2024. Available from: https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_14th_edition.pdf. Access 20 Jun 2024.

- 12.Allison M, Emerson A, Pickett ML, Ramaswamy M. Incarcerated adolescents’ attitudes toward Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Report from a Juvenile Facility in Kansas. Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19855290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman PN, Szoko N, Lynch L, Rankine J. Vaccination for justice-involved youth. Pediatrics. 2022;149(4):e2021055394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junghans C, Heffernan C, Valli A, Gibson K. Mass vaccination response to a measles outbreak is not always possible. Lessons from a London prison. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(13):1689–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couper S, Bird SM, Foster GR, McMenamin J. Opportunities for protecting prisoner health: influenza vaccination as a case study. Public Health. 2013;127(3):295–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Nations General Assembly. United Nations standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules). Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/Nelson_Mandela_Rules-E-ebook.pdf. Access 14 Nov 2022.

- 17.McLeod KE, Butler A, Young JT, Southalan L, Borschmann R, Sturup-Toft S, Dirkzwager A, Dolan K, Acheampong LK, Topp SM, Martin RE, Kinner SA. Global Prison health care governance and health equity: a critical lack of evidence. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(3):303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patient or prisoner: does it matter which Government Ministry is responsible for the health of prisoners? Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/126410/e94423.pdf. Access 14 Nov 2022.

- 19.WHO Europe. Good governance for prison health in the 21st century: a policy brief on the organization of prison health. 2013. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/231506/Good-governance-for-prison-health-in-the-21st-century.pdf. Access 14 Nov 2022.

- 20.Moazen B, Assari S, Neuhann F, Stöver H. The guidelines on infection control in prisons need revising. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):301–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinner SA, Young JT, Snow K, Southalan L, Lopez-Acuña D, Ferreira-Borges C, O’Moore É. Prisons and custodial settings are part of a comprehensive response to COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(4):e188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burki T. Prisons are in no way equipped to deal with COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1411–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penal Reform International and Harm Reduction International. COVID-19 vaccinations for prison populations and staff: Report on global scan. 2021. Available from: https://cdn.penalreform.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/HRI-PRI_CovidVaccinationReport_Dec2021.pdf. Access 14 Nov 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information (Appendix 1).

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.