Abstract

Background

Despite the explicit biomechanical advantages associated with FNS, it is currently inconclusive, based on the existing literature, whether Femoral Neck System (FNS) outperforms Cannulated cancellous screws (CSS) in all aspects. Due to variances in bone morphology and bone density between the elderly and young cohorts, additional research is warranted to ascertain whether the benefits of FNS remain applicable to elderly osteoporosis patients. This study aimed to investigate the biomechanical properties of FNS in osteoporotic femoral neck fractures and propose optimization strategies including additional anti-rotation screw.

Methods

The Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture models were reconstructed using finite element numerical techniques. The CSS, FNS, and modified FNS (M-FNS) models were created based on features and parameterization. The various internal fixations were individually assembled with the assigned normal and osteoporotic models. In the static analysis mode, uniform stress loads were imposed on all models. The deformation and stress variations of the femur and internal fixation models were recorded. Simultaneously, descriptions of shear stress and strain energy were also incorporated into the figures.

Results

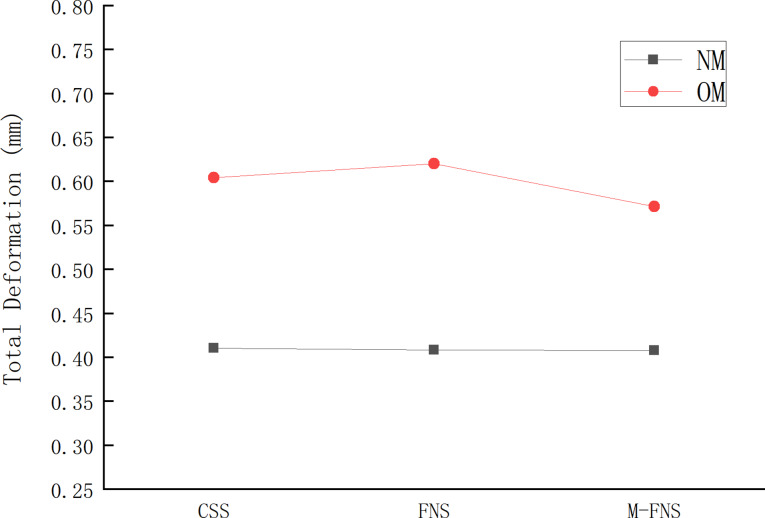

Following bone mass reduction, deformations in CSS, FNS, and M-FNS increased by 47%, 52%, and 40%, respectively. The equivalent stress increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 3%, 43%, 17%, respectively. Meanwhile, variations in strain energy and shear stress were observed. The strain energy increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 4%, 76%, and 5%, respectively. The shear stress increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 4%, 65% and 44%, respectively. Within the osteoporotic model, M-FNS demonstrated the lowest total displacement, shear stress, and strain energy.

Conclusion

Modified FNS showed better stability in the osteoporotic model (OM). Using FNS alone may not exhibit immediate shear resistance advantages in OM. Concurrently, the addition of one anti-rotation screw can be regarded as a potential optimization choice, ensuring a harmonious alignment with the structural characteristics of FNS.

Keywords: Femoral neck system, Femoral neck fractures, Finite element analysis, Osteoporosis

Background

In general, basicervical fractures or Pauwels III type fractures are deemed mechanically unstable, requiring the utilization of internal fixation devices [1]. Despite the availability of numerous biomechanical pieces of evidence, there is still controversy regarding the choice of implants for femoral neck fractures [2]. FNS has been widely embraced by numerous orthopedic surgeons for the treatment of femoral neck fractures [3]. The FNS group exhibited a comparatively shorter average surgical duration in comparison to the CSS group. Simultaneously, lower complications such as implant failure, loss of reduction, avascular necrosis, and non-union were observed in the FNS group [4–7]. Numerous finite element analysis experiments have been conducted to substantiate the biomechanical advantages of FNS. In the management of Pauwels III type femoral neck fractures, the integration of angular stability and compression sliding was achievable with FNS [8].

Despite the explicit biomechanical advantages associated with FNS [9, 10], it is currently inconclusive, based on the existing literature, whether FNS outperforms CSS in all aspects. It is noteworthy that previous biomechanical studies collected data from young volunteers. Due to the differences in bone morphology and density between older and younger individuals, further research is required to determine whether the advantages of FNS remain applicable to elderly patients with osteoporosis [11, 12]. Yeoh demonstrated that in elderly patients with osteoporosis, FNS did not exhibit superior advantages compared to CSS [13]. The author delineated shortcomings of FNS treatment for elderly low bone mass femoral neck fractures in terms of factors such as blood loss and hospitalization duration. However, based on our understanding, there are currently no precise biomechanical experiments available to corroborate this assertion.

Therefore, we aimed to construct an osteoporotic model using finite element numerical techniques for subsequent biomechanical validation. We hypothesized that in the low bone mass femoral neck fracture model, FNS may not demonstrate absolute biomechanical superiority. In our study, various indicators such as displacement, shear stress, and equivalent stress from different finite element models were presented. Our objective was to investigate the biomechanical properties of FNS in femoral neck fractures with low bone mass and propose optimization strategies.

Materials and methods

Modeling the initial proximal femur

A 65-year-old female volunteer was recruited, with a weight of 60 kg and a height of 160 centimeters. She had no history of hip joint or systemic diseases. Prior to undergoing CT, the informed consent form had already been signed. The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee ([2022]053). The scanned CT images were fully imported into MIMICS 20.0 (materialize, Leuven, Belgium). The target bone structure was preliminarily identified through the customization of thresholds. Efforts were made to remove excess noise while preserving the original bone morphology to the extent possible. After removing abnormal surface patches, a three-dimensional reconstruction was conducted, and the project was exported in STL format. The initially smoothed model was imported into Geomagic - Wrap 2017( Geomagic, USA). Due to the irregular morphology of the proximal femur, the boundary curves of the model need to be redefined. During this process, we eliminated degenerate corners while retaining essential local features to ensure the authenticity of the proximal femur. After fitting the surfaced model, it underwent verification and was subsequently imported into SolidWorks 2017 (Dassault, France).

Modelling of fractures and internal fixation models

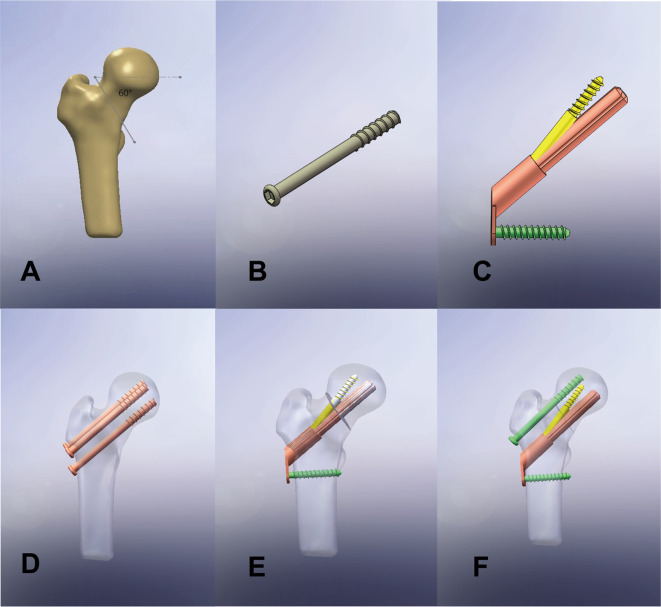

Adjusting the Pauwels angle to 60 degrees was done to simulate the Pauwels III type fracture model (Fig. 1A). The FNS (DePuy Synthes, Zuchwil, Switzerland) and CSS models were drawn using the sketching tool (Fig. 1B, C). The main features and threads of the screws were retained, while some features were simplified to adapt to the biomechanical analysis. The grayscale value assignment method for material properties: ρ= -13.4 + 1017*GV (g/m³), E-modulus-=388.8 + 5925*ρ(Pa) [14], was employed to simulate the normal model and the osteoporotic model. Based on previous studies by scholars [15], the bone density in the osteoporotic model was reduced to 75% of the initial bone density. In the assembly mode, the femoral model and the internal fixation model were combined through boolean logical operations. The femoral model was divided into the normal model (NM) and the osteoporotic model (OM), while the internal fixation model was divided into CSS, FNS, and M-FNS models (Fig. 1D, E, F). The three cannulated screws(7.3 mm) were positioned parallel to the neck shaft angle (approximately 129 degrees) and arranged in a triangular pattern. The main nail of the FNS model measured 85 mm in length and was positioned centrally along the coronal plane of the femoral neck, with a placement depth of 5 mm below the cartilage of the femoral head. In the M-FNS model, to ensure non-interference of internal fixation, the hollow screw was placed superiorly, while the FNS was placed inferiorly. Interference checks were mandatory for all models before proceeding with further biomechanical analysis in Ansys 17.0(Ansys, Canonsburg, PA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual diagrams of all models: Pauwels type III fracture model (A); CSS model (B); FNS model (C); CSS fixed model (D); FNS fixed model (E); M-FNS fixed mode (F)

Finite element pre-processing and mechanical analysis

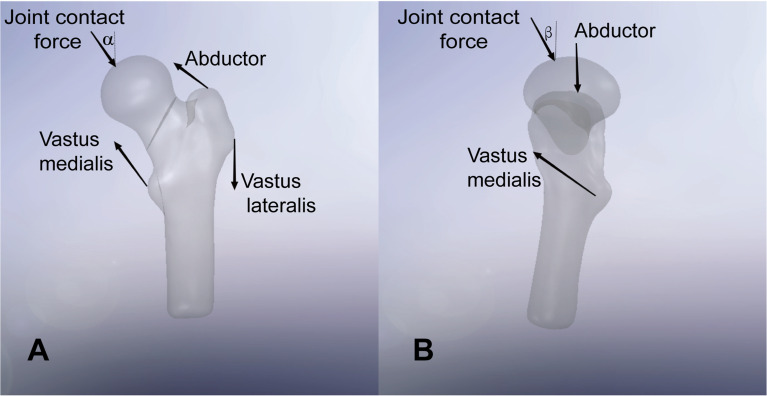

All internal fixation materials were made of titanium alloy with elastic modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio of 110,000 MPa and 0.3, respectively. The connection between fracture surfaces was set as frictional, with a friction coefficient of 0.46 [16, 17]. The contact condition between the internal fixation screws and the femur was set to bonded. In accordance with convergence experiments, the selected mesh size was 1 mm. Considering the intricate geometric structure of the femur, we chose a non-uniform mesh size, with a maximum of 1 mm and a minimum of 0.8 mm (Fig. 2). The distal end of the femur was immobilized, and its degrees of freedom were constrained. The simulation boundary conditions specified a load applied to the hip joint equivalent to approximately 3.0 times the body weight, corresponding to 1800 N [18]. The muscle loading model at the proximal end of the femur was simplified [19, 20](Fig. 3). The validation of the model’s efficacy was grounded in our previously published research [21].

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of mesh: Non-uniform meshing at the proximal end of the femur (A); Mesh details of the internal fixation (B)

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of the simplified muscle loading model of the proximal femur: The coronal plane angle (α) was configured at 13° (A); The sagittal plane angle (β)was set to 3°(B)

Evaluation indicators

In the static analysis mode, uniform stress loads were imposed on all models. The deformation and stress variations of the femur and internal fixation models were recorded. Simultaneously, descriptions of shear stress and strain energy were also incorporated into the figures.

Results

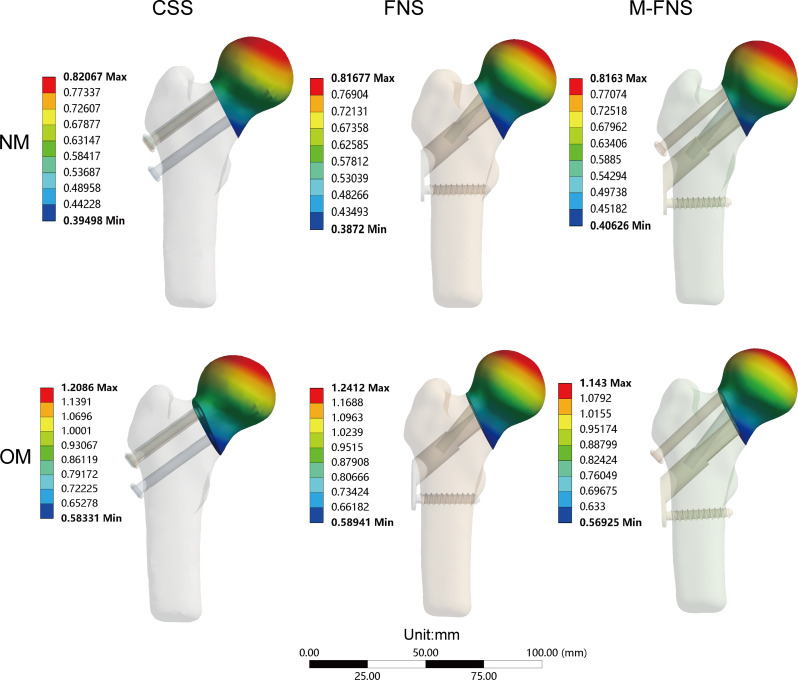

The total deformation status of all models was depicted in Fig. 4. Deformation primarily concentrated in the weight-bearing region of the femoral head. Following bone mass reduction, deformations in CSS, FNS, and M-FNS increased by 47%, 52%, and 40%, respectively. The M-FNS exhibited the least overall deformation in OM. The distribution of equivalent stress for each model was illustrated in Fig. 5. The red bands indicated areas of stress concentration. In the context of osteoporosis, an increase in equivalent stress was observed across all models. The equivalent stress increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 3%, 43%, 17% respectively. In the normal model, there was evident stress concentration around the distal screw of the CSS, whereas the stress distribution was relatively dispersed in the FNS and M-FNS. In the osteoporotic model, CSS and FNS both showed significant stress concentration, whereas the stress distribution in M-FNS was relatively homogeneous.

Fig. 4.

The band graph illustrated the total displacement of each model. The three charts above depicted the displacement within the NM (normal model). The subsequent three charts showcased the displacement within the OM ((osteoporotic model). Each chart was accompanied by a dedicated legend

Fig. 5.

The band graph illustrated equivalent stress of each internal fixation model. The three charts above depicted the equivalent stress within the NM (normal model). The subsequent three charts showcased the equivalent stress within the OM (osteoporotic model). Each chart was accompanied by a dedicated legend

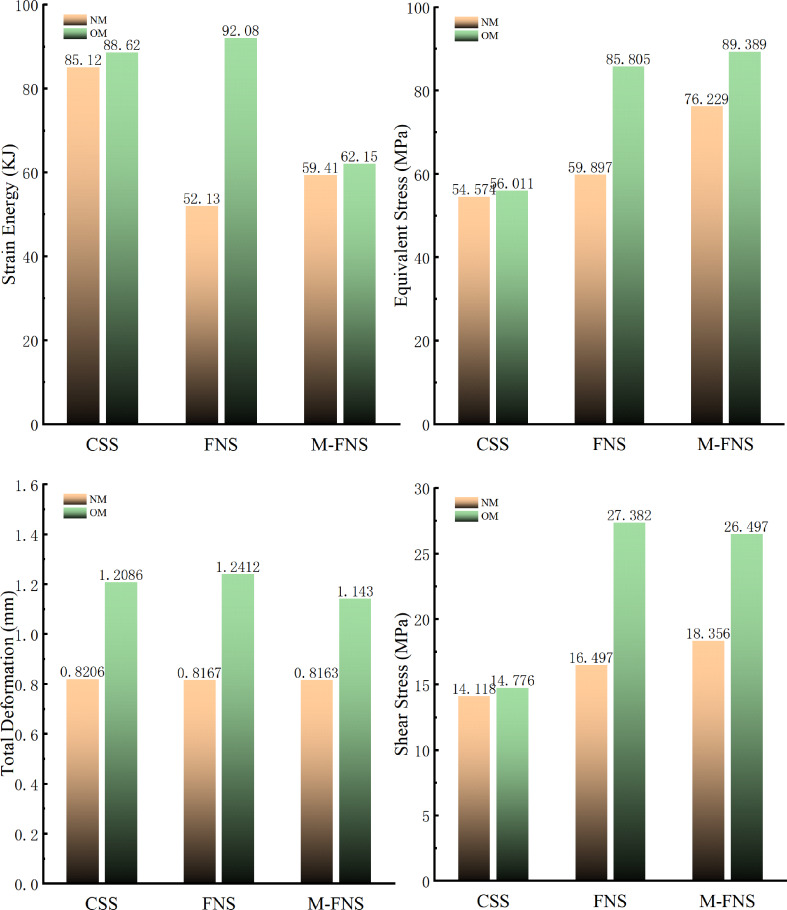

Meanwhile, variations in strain energy and shear stress were observed in Fig. 6. Strain energy serves as a pivotal metric in structural mechanics, providing insights into the stability of the structure. In the context of osteoporosis, an increase in strain energy was observed across all models. The strain energy increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 4%, 76%, and 5% respectively. FNS demonstrated the lowest strain energy in the NM, whereas in the OM model, M-FNS exhibited the least strain energy. Shear stress refers to the force per unit area that causes parallel layers of a material to slide relative to each other. It is a fundamental mechanical parameter used to analyze the response of materials and structures to applied loads, particularly in situations where deformation occurs due to sliding or shearing forces. In the context of osteoporosis, an increase in shear stress was observed across all models. The shear stress increments for CSS, FNS, and M-FNS were 4%, 65% and 44% respectively.

Fig. 6.

The figure presented the peak details of each model. Equivalent stress, total displacement, shear stress, and strain energy were recorded. Each chart was individually titled, and they shared a unified legend

Additionally, we applied a torsional load of 2.5 N·m to the femoral head to simulate twisting motions and recorded the total deformation of the model [22]. The result was consistent with the trend observed under the one-legged standing condition, with the M-FNS demonstrating better stability.(Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The total deformation of each model under torsional conditions: NM (normal model); OM (osteoporotic model)

Discussion

The elevated failure rate [23] in the management of femoral neck fractures stems from both the substantial energy trauma [24]of the fracture itself and the biomechanical stability milieu [14]. The biomechanical indices of internal fixation stability in fractures serve as metrics for evaluating the stability of the internal fixation system at the fracture site. These metrics encompass strength, rigidity, stress distribution, and biocompatibility, among others. In our finite element analysis, within the model of normal bone quality, the biomechanical indicators of FNS were found to be overall superior to those of CSS, which was consistent with the results reported in other literature [9, 10]. In aging female populations, diminished bone quality can potentially negate the mechanical benefits provided by sophisticated systems like the FNS. In contrast, the performance of CSS, which are less dependent on bone quality for their stability, might be on par with those of more advanced systems when treating such patients. In clinical practice, some physicians have adopted the approach of adding an additional hollow screw to address this issue. Despite achieving good clinical outcomes, its biomechanics have not been validated.

Clinical research indicated that FNS represented a safe and efficacious internal fixation therapeutic approach [25, 26]. FNS has also undergone more extensive scrutiny by scholars in the treatment of femoral neck fractures. Jung optimized the spatial positioning of the FNS main nail to enhance stability [27]. We constructed an osteoporotic model using finite element numerical techniques for subsequent biomechanical validation. Although it cannot fully replicate in vivo conditions, it can enhance the credibility and reproducibility of experiments. In our research, all models and operating conditions remained consistent, with the only variable being the type of internal fixation.

Total deformation in finite element analysis refers to the overall deformation of a structure or component under applied loads. It is obtained by applying loads to the finite element model and solving for the resulting deformations, typically represented as vectors or scalars. Total deformation encompasses various types of deformations in the structure, including translation, rotation, and stretching, reflecting the overall response of the structure to external loads. In engineering practice, total deformation is an important indicator for evaluating structural performance and stability. In our study, as bone mass decreased, there was an increase in the total displacement of the model, but the range of deformation mostly remained within the stress zone of the femoral head. In all models, M-FNS demonstrated the lowest overall displacement, indirectly suggesting the highest stability of M-FNS.

Despite the 5% increase in equivalent stress of M-FNS compared to FNS as observed in OM, the difference between the two is marginal due to their consistent yield strength under identical stress rates and temperatures. Inappropriate stress distribution of internal fixation may lead to complications such as non-fracture site fractures, soft tissue injuries, nerve damage, etc. Understanding the significance of stress distribution of fracture internal fixation guides the design and optimization of treatment plans, assesses treatment efficacy, predicts the risk of complications, thereby improving treatment success rates and patient quality of life. As bone mass decreased, the stress concentration zones within all models’ internal fixations increased significantly. In OM, FNS demonstrated the largest stress concentration area, whereas M-FNS exhibited a more homogeneous stress distribution.

In the osteoporotic model, M-FNS demonstrated minimal shear stress, establishing its superior mechanical stability. The significance of internal fixation shear stress lies in its assessment of fixation system stability and fracture fragment displacement. Effective management of shear stress is critical for preventing fixation system loosening or failure, thereby facilitating fracture healing. Excessive shear stress can lead to fixation system damage or delayed fracture union, underscoring the importance of meticulous attention to detail in fixation device design and utilization.

Furthermore, we incorporated the description of the strain energy. Our study indicated that under osteoporotic conditions, the strain energy increment and peak values were highest for FNS, whereas M-FNS demonstrated superior biomechanical stability. The internal fixation strain energy refers to the energy generated within a material due to the interactions between atoms or molecules when deformation occurs internally. When a material is subjected to external forces, the distances between atoms or molecules change, leading to deformation of the material. This deformation causes a change in internal energy, with a portion of the energy stored in the form of strain, known as internal strain energy. Internal fixation strain energy is related to the elasticity of the material. When the external force ceases, the material returns to its original shape, releasing the stored internal strain energy. This released energy helps the material resist the external force, giving it a certain level of elasticity and deformation capability. Internal fixation strain energy is also an important property of materials during processes such as bending and stretching. A lower strain energy signifies reduced deformation under loading in internal fixation, thereby preserving structural stability.

As reported in the literature, when using FNS alone, central placement was the best option. Lower-placed FNS increased the interfragmentary sliding distance, which reduced the overall stability. In the M-FNS model, the added cannulated screws served an anti-rotation and compression function, thereby compensating for the mechanical shortcomings of the lower-placed FNS. Compared with the application of FNS alone, CSS and M-FNS can provide multidirectional fixation in an osteoporotic environment. Theoretically, M-FNS not only retains the advantages of FNS but also compensates for the mechanical deficiencies of using FNS alone in an osteoporotic environment.

Nevertheless, our study also exhibited certain limitations. Due to variations in modeling details, specific numerical values may not be entirely congruent with those reported in other literature. Nonetheless, the overarching trends remain consistent. None of the models reached the state of ultimate load-bearing, thus requiring further validation of their credibility. Our experiments did not investigate the mechanical performance under dynamic loading conditions, necessitating further validation through in vivo experiments.

Conclusions

Modified FNS showed better stability in the osteoporotic model (OM). Using FNS alone may not exhibit immediate shear resistance advantages in OM. Concurrently, the addition of one anti-rotation screw can be regarded as a potential optimization choice, ensuring a harmonious alignment with the structural characteristics of FNS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

ChongNan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing-review& editing.Yuxiu Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Editing.Di Zhang: Writing instructionYazhuo Qin: Visualization, Investigation.Hetong Yu: Software, Validation.Yong Liu: Language Proofreading.Zhanbei Ma: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Baoding City Science and Technology Plan Project( 2241ZF228).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Baoding No.1 Central Hospital([2022]053). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The volunteer agreed to the trial protocol and informed consent was obtained from her.

Consent for publication

The authors certify that written informed consent has been obtained from the subject for the publication of identifiable information in this online open-access publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chong Nan and Yuxiu Liu are authors contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Augat P, Bliven E, Hackl S. Biomechanics of femoral Neck fractures and implications for fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(Suppl 1):S27–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, McKee M, Bhandari M. Management of young femoral neck fractures: is there a consensus. Injury. 2015;46(3):435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel S, Kumar V, Baburaj V, Dhillon MS. The use of the femoral neck system (FNS) leads to better outcomes in the surgical management of femoral neck fractures in adults compared to fixation with cannulated screws: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2023;33(5):2101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildirim C, Demirel M, Karahan G, Cetinkaya E, Misir A, Yamak F, Bozdağ E. Biomechanical comparison of four different fixation methods in the management of Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures: is there a clear winner. Injury. 2022;53(10):3124–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y, Zhang Z, Wang L, Xiong W, Fang Q, Wang G. Femoral neck system versus inverted cannulated cancellous screw for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in adults: a preliminary comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu H, Cheng J, Feng M, Gao Z, Wu J, Lu S. Clinical outcome of femoral neck system versus cannulated compression screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in younger patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou XQ, Li ZQ, Xu RJ, She YS, Zhang XX, Chen GX, Yu X. Comparison of early clinical results for femoral Neck System and Cannulated screws in the treatment of unstable femoral Neck fractures. Orthop Surg. 2021;13(6):1802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng Y, Zhang Y, Guo C. Finite element analysis of femoral neck system in the treatment of Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture. Med (Baltim). 2022;101(28):e29450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schopper C, Zderic I, Menze J, et al. Higher stability and more predictive fixation with the femoral Neck System versus Hansson Pins in femoral neck fractures Pauwels II. J Orthop Translat. 2020;24:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoffel K, Zderic I, Gras F, Sommer C, Eberli U, Mueller D, Oswald M, Gueorguiev B. Biomechanical evaluation of the femoral Neck System in Unstable Pauwels III femoral Neck fractures: a comparison with the dynamic hip screw and cannulated screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(3):131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Augat P, Schorlemmer S. The role of cortical bone and its microstructure in bone strength. Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii27–2731. 10.1093/ageing/afl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham AC, Agarwalla A, Yadavalli A, McAndrew C, Liu JY, Tang SY. Multiscale predictors of femoral Neck in situ strength in Aging women: contributions of BMD, cortical porosity, reference point indentation, and nonenzymatic glycation. J Bone Min Res. 2015;30(12):2207–14. 10.1002/jbmr.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeoh SC, Wu WT, Peng CH, et al. Femoral neck system versus multiple cannulated screws for the fixation of Pauwels classification type II femoral neck fractures in older female patients with low bone mass. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang D, Zhan S, Hai H, et al. What makes vertical femoral neck fracture with posterior inferior comminution different? An analysis of biomechanical features and optimal internal fixation strategy. Injury. 2023;54(8):110842. 10.1016/j.injury.2023.110842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goffin JM, Pankaj P, Simpson AH, Seil R, Gerich TG. Does bone compaction around the helical blade of a proximal femoral nail anti-rotation (PFNA) decrease the risk of cut-out? A subject-specific computational study. Bone Joint Res. 2013;2(5):79–83. 10.1302/2046-3758.25.2000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sensoz E, Özkal FM, Acar V, Cakir F. Finite element analysis of the impact of screw insertion distal to the trochanter minor on the risk of iatrogenic subtrochanteric fracture. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2018;232(8):807–18. 10.1177/0954411918789963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Lin J, Huang A, et al. Modified cannulated screw fixation in the treatment of Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures: a biomechanical study. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon). 2020;74:103–10. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Houcke J, Schouten A, Steenackers G, Vandermeulen D, Pattyn C, Audenaert EA. Computer-based estimation of the hip joint reaction force and hip flexion angle in three different sitting configurations. Appl Ergon. 2017;63:99–105. 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffin JM, Pankaj P, Simpson AH. The importance of lag screw position for the stabilization of trochanteric fractures with a sliding hip screw: a subject-specific finite element study. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(4):596–600. 10.1002/jor.22266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tianye L, Peng Y, Jingli X, et al. Finite element analysis of different internal fixation methods for the treatment of Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108658. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nan C, Ma L, Liang Y, Li Y, Ma Z. Mechanical effects of sagittal variations on Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures treated with femoral Neck System(FNS). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1045. 10.1186/s12891-022-06016-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt E, Verdonschot N. Biomechanical analysis of the sliding hip screw, cannulated screws and Targon1 FN in intracapsular hip fractures in cadaver femora. Injury. 2011;42(2):183–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Christie J. Hip fractures in adults younger than 50 years of age. Epidemiology and results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(312):238–46. [PubMed]

- 24.Jiang D, Zhan S, Cai Q, Hu H, Jia W. Long-term differences in clinical prognosis between crossed- and parallel-cannulated screw fixation in vertical femoral neck fractures of non-geriatric patients. Injury. 2021;52(11):3408–14. 10.1016/j.injury.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stassen RC, Jeuken RM, Boonen B, Meesters B, de Loos ER, van Vugt R. First clinical results of 1-year follow-up of the femoral neck system for internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021. 10.1007/s00402-021-04216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vazquez O, Gamulin A, Hannouche D, Belaieff W. Osteosynthesis of non-displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly population using the femoral neck system (FNS): short-term clinical and radiological outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):477. 10.1186/s13018-021-02622-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung CH, Cha Y, Yoon HS, et al. Mechanical effects of surgical variations in the femoral neck system on Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture: a finite element analysis. Bone Joint Res. 2022;11(2):102–11. 10.1302/2046-3758.112.BJR-2021-0282.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.