Abstract

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) technology has emerged as a revolutionary therapeutic technology in dermatology, recognized for its safety, effectiveness, and minimal side effects. CAP demonstrates substantial antimicrobial properties against bacteria, viruses, and fungi, promotes tissue proliferation and wound healing, and inhibits the growth and migration of tumor cells. This paper explores the versatile applications of CAP in dermatology, skin health, and skincare. It provides an in-depth analysis of plasma technology, medical plasma applications, and CAP. The review covers the classification of CAP, its direct and indirect applications, and the penetration and mechanisms of action of its active components in the skin. Briefly introduce CAP’s suppressive effects on microbial infections, detailing its impact on infectious skin diseases and its specific effects on bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. It also highlights CAP’s role in promoting tissue proliferation and wound healing and its effectiveness in treating inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo. Additionally, the review examines CAP’s potential in suppressing tumor cell proliferation and migration and its applications in cosmetic and skincare treatments. The therapeutic potential of CAP in treating immune-mediated skin diseases is also discussed. CAP presents significant promise as a dermatological treatment, offering a safe and effective approach for various skin conditions. Its ability to operate at room temperature and its broad spectrum of applications make it a valuable tool in dermatology. Finally, introduce further research is required to fully elucidate its mechanisms, optimize its use, and expand its clinical applications.

Keywords: Cold atmospheric plasma, Dermatological diseases, Inflammatory skin diseases, Skincare

Introduction

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) has garnered significant attention in recent years as an innovative therapeutic technology with broad applications in various fields of medicine, including dermatology. CAP is a partially ionized gas that operates at room temperature, which makes it particularly suitable for medical applications. Its unique properties, including generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) and ultraviolet radiation, contribute to its efficacy in treating many skin conditions. These properties enable CAP to combat microbial infections effectively, promote wound healing, and inhibit tumor cell growth and migration [1–3]. Studies have shown that CAP can effectively eliminate bacteria, viruses, and fungi, making it a potent tool in dermatological treatments [4–6]. Additionally, CAP has been demonstrated to support tissue regeneration and wound healing, offering promising applications for chronic wound management and other skin conditions [7, 8].

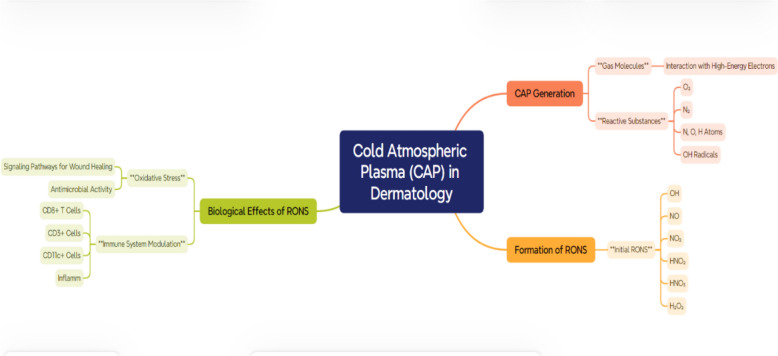

Figure 1 provides a summary of the key mechanisms by which CAP acts on the skin, highlighting its therapeutic potential in dermatology. The process begins with the generation of RONS through the interaction of high-energy electrons with gas molecules. These RONS, including molecules like OH, NO, and H2O2, initiate oxidative stress and trigger biological signaling pathways that are crucial for wound healing, antimicrobial effects, and tissue regeneration. In this picture, the effect of CAP on transdermal drug delivery is also depicted through two methods: transdermal plasma delivery (plasmaporation) and tissue penetration. CAP’s electric field creates a breakdown of the stratum corneum, the skin’s natural barrier, which allows active ingredients and RONS to reach deeper skin layers. This process increases skin permeability, which in turn assists in the transfer of drugs and bioactive molecules and, at the same time, does not lead to the destruction of the underlying tissues. Besides serving as a factor in drug delivery, CAP couscous regenerates the skin by inducing both collagen synthesis and angiogenesis and promoting epithelialization, hence speeding up the repair of wounds and tissues.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) mechanism in dermatological applications illustrates the various steps involved in CAP’s interaction with skin tissues for therapeutic purposes. CAP generates reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) through high-energy collisions, which play a pivotal role in biological processes such as oxidative stress, immune modulation, and wound healing. The figure details how CAP facilitates transdermal drug delivery by breaking down the stratum corneum and enhancing permeability through plasmaporation. Additionally, it highlights CAP’s ability to promote tissue regeneration, target infected or cancerous cells selectively, and modulate lipid composition for improved skin barrier function

Numerous studies have documented the promising applications of CAP in dermatology. For instance, Gan et al. [1] conducted a systematic review highlighting CAP’s applications in dermatology and its safety and effectiveness [9]. Braný et al. [2] emphasized the decisive role of CAP in modern medicine, focusing on its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties and potential to promote tissue regeneration [10]. Laroussi [3] discussed the new frontier of low-temperature plasma applications in healthcare, underscoring CAP’s role in medical treatments [11]. Bekeschus et al. [7] explored the mechanisms by which CAP-stimulated wound healing occurs, providing valuable insights into its therapeutic potential [12]. Park et al. [8] reviewed various atmospheric pressure plasma sources for biomedical applications, offering a comprehensive overview of the technology’s versatility [13]. Busco et al. [19] highlighted the emerging potential of CAP in skin biology, discussing its role in skin health and disease management [14]. Chen et al. [9] modeled plasma–biofilm and plasma–tissue interactions, shedding light on the intricate mechanisms at play [15]. Alizadeh and Ptasińska [15] examined recent advances in plasma-based cancer treatments, approaching clinical translation with a focus on intracellular mechanisms [16]. These studies collectively underscore the multifaceted benefits of CAP in dermatology.

Despite the extensive research on CAP, several gaps remain in fully understanding its mechanisms and optimizing its use in clinical settings. More comprehensive studies are needed to explore the long-term effects of CAP treatments, standardize application protocols, and assess the safety and efficacy of CAP across diverse patient populations. While CAP’s antimicrobial properties are well-documented, its potential in treating inflammatory skin diseases and cosmetic applications warrants further investigation.

This comprehensive review aims to address these research gaps by providing an in-depth analysis of the current state of CAP applications in dermatology. The paper explores the fundamental principles of plasma technology and the various medical applications of plasma and specifically focus on CAP. It will classify CAP, detail its direct and indirect applications, and elucidate its active components’ penetration and mechanisms of action in the skin. Furthermore, the review will examine CAP’s suppressive effects on microbial infections, its role in promoting tissue proliferation and wound healing, and its efficacy in treating inflammatory and immune-mediated skin diseases. The paper also discusses the safety and tolerance of CAP applications, as well as the challenges and potential solutions in implementing CAP treatments for skin disease and skincare. Finally, the review outlines the prospects of CAP in dermatology, aiming to foster further advancements in plasma medicine.

This interdisciplinary field drives healthcare innovation by integrating plasma physics, life sciences, and clinical medicine [1–4]. Plasma, an ionized gas, shows therapeutic potential across medical areas. In disinfection, plasma offers a novel approach to pathogen eradication. Low-temperature atmospheric plasmas release specific reactive substances for healing [11–14].

Moreover, plasma medicine is advancing cancer treatment, with research at top universities [15]. Its influence extends to neuroscience, combining plasma physics, biology, and engineering to explore new applications. Plasma medicine transforms healthcare with innovative treatments, impacting wound healing, blood coagulation, cancer treatment, and more [1–3, 14–17]. Monitoring plasma’s real-time effects is crucial for tailoring therapies and opening new paths for clinical interventions [1–3, 14, 17].

Various plasma sources, such as dielectric barrier discharges (DBD) and cold atmospheric plasma (CAP), are used in biomedical settings [1–4]. These sources operate at safe body temperatures for tissue applications and device sterilization. Research into different plasma sources continues to drive medical advancements, showcasing the field’s interdisciplinary potential [1–5]. Plasma can be differentiated into high- and low-temperature types with more distinctions based on thermodynamics. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treats skin diseases, including cancer, because it operates under normal temperature and pressure conditions. CAP releases reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species, affecting living organisms and cancer cells, respectively. Ongoing studies are looking at novel plasma sources that will help advance modern medicine [1–4]. Table 1 presents a summary of the leading biomedical applications of plasmas.

Table 1.

Plasma and its multifaceted biomedical applications

| Application | Description |

|---|---|

| Cold atmospheric plasma | An emerging multi-agent technology and multi-modal therapy with diverse applications across various biomedical fields [5] |

| Oral biofilm-related infections | Plasma medicine effectively addresses oral biofilm-related infections, showcasing its efficacy in promoting oral health [6] |

| Therapeutic use of physical plasma | Involves the direct application of physical plasma on or in the human body for therapeutic purposes [7] |

| Plasma technology for biomedical applications | There is growing interest in utilizing plasmas for biomedical applications, particularly in plasma medicine, focusing on therapeutic advancements [8] |

| Biomedical applications of cold atmospheric plasma | Encompasses sterilization, wound healing, blood coagulation, oral/dental disease treatment, cancer therapy, and immunotherapy [5, 7, 9] |

| Diverse range of applications | Demonstrates various applications and advancements, offering examples of ideas and applications in the medical and biomedical domains [10] |

The medical applications of plasma involve using different types of plasma to achieve specific therapeutic goals. This multidisciplinary field, plasma medicine, seamlessly integrates principles from plasma physics, medicine, biology, plasma chemistry, and engineering [1, 17]. The direct application of physical plasma on or within the human body has proven effective for therapeutic purposes, including antimicrobial effects, wound healing, and cancer treatment, expanding the scope of knowledge in this emerging field [1–5, 15, 18].

The CAP device showcased in Fig. 2 results from meticulous design and operation by our hospital’s dedicated research group. Comprising a surface discharge plasma generator device and a voltage regulating instrument, the components include an electric power supply for plasma initiation, a voltage regulator for stable output, a high-voltage probe for safety monitoring, a digital storage oscilloscope for signal analysis, and an electrode for surface CAP interaction. Figure 2B elucidates plasma generation’s working principles and subsequent interaction with targeted surfaces. This visual representation serves as a guide to understanding the intricate processes that occur within the device. By illustrating the interplay of various components, the schematic offers a comprehensive view of the technology’s underlying mechanisms. Figure 2C focuses on detecting and analyzing activated water treated with CAP. This segment highlights the broader applications of the technology, particularly in the biomedical and sterilization realms. By showcasing the methodology and apparatus employed for water analysis, this section underscores the versatility and potential impact of the CAP device in advancing healthcare and related fields.

Fig. 2.

The features of the CAP device developed and operated by our hospital research group include A a surface discharge plasma generator device and a voltage regulating instrument. 1 Electric power supply; 2 voltage regulator; 3 high-voltage probe; 4 digital storage oscilloscope; 5 electrode for surface CAP. B Schematic diagram of plasma working principle. C Detection of activated water treated with CAP

Plasma medicine demonstrates its relevance in neuroscientific applications, emphasizing its interdisciplinary nature [17]. This therapeutic approach is not confined to a singular method but encompasses a spectrum of plasma types tailored for specific therapeutic goals [14]. The potential applications extend to disinfection, wound healing, and cancer treatment, marking plasma medicine as a promising avenue in clinical practice [18–20]. Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of diverse medical applications within plasma medicine. Notably, most of the research in plasma medicine is conducted in vitro and animal models, highlighting the emerging nature of the field and its integration of plasma physics, life sciences, and clinical medicine [1–4, 17]. Even though many of the studies related to CAP are only in vitro and animal, one must remember how those data can be used medically on humans. Developing from preclinical research to clinical trials is very important to check the security and utility of CAP for human therapy. Performing human trials will facilitate the process of closing the porthole and develop a commercial way to include CAP in dermatological treatments [1–4, 17].

Table 2.

Various medical applications of plasma medicine

| Medical applications | Description |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic purposes | Direct application of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) for various medical treatments [20, 21] |

| Disinfection | Utilizes ionized gas (physical plasma) for disinfection, effectively inactivating various microorganisms, including viruses, resistant microbes, fungal cells, bacteria, spores, and biofilms created by microbes [13, 22, 23] |

| Healing | Understudy for its potential in healing, plasma medicine stimulates cell proliferation and angiogenesis with lower plasma treatment intensity, contributing to wound healing [17, 21, 24] |

| Cancer treatment | Exploration of plasma medicine for cancer treatment can inactivate cells and initiate cell death with higher plasma intensity [25–28] |

| Blood coagulation | Utilization of plasma for blood coagulation [28, 29] |

| Dental applications | Application of ionized gas in plasma medicine for various dental purposes [20, 30] |

| Sterilization of implants and surgical instruments | Plasma-generated active species are harnessed for sterilizing implants and surgical instruments [31, 32] |

| Modifying biomaterial surface properties | Plasma medicine can modify biomaterial surface properties [33, 34] |

| Treatment of skin diseases and wounds | Ongoing research on the potential of plasma medicine for treating skin diseases and wounds [17, 21, 24, 35] |

| Multidisciplinary research | Intersection of scientific domains for diverse research in plasma medicine, combining plasma physics, life sciences, and clinical medicine [1–3, 17] |

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) and its safety

CAP is a non-thermal plasma that operates at or near room temperature. CAP has gained medical attention due to its diverse applications, including wound healing, sterilization, and cancer treatment. The operational mechanism of non-thermal biocompatible plasma (NBP) may be associated with the collaborative effects of its constituents, including ultraviolet radiation and reactive species [36]. The unique property of CAP is its ability to generate various RONS without significantly increasing the temperature of the surrounding tissues. This makes CAP suitable for delicate medical procedures where maintaining a low-temperature environment is crucial. Studies have shown promising results in using CAP for wound disinfection and promoting tissue proliferation [5, 36, 37].

CAP, which contains heavy ions at low temperatures, is the focus of this study. CAP has gained increasing attention in clinical medicine, particularly dermatology [1–3]. Plasma is formed by ionizing gases under heat or a strong electromagnetic field, resulting in a cloud of charged particles, including electrons, ions, metastable species, ultraviolet light, visible light, electromagnetic fields, and reactive substances [1–3, 38]. Named for its equal distribution of positive and negative charges, plasma exhibits diverse characteristics based on temperature, categorizing it into thermal plasma (around 10,000 K), warm plasma (3000–5000 K), and cold plasma (near room temperature) [39]. CAP, a type of non-equilibrium plasma, has gained attention, especially in dermatology, due to its ability to operate at room temperature safely and efficiently [1–3]. CAP influences organisms through active components such as chemical active particles RONS, ultraviolet radiation (UV), and charged particles (electrons and positive and negative ions) at the molecular level, making it suitable for skin treatment [18, 40, 41]. When applied to skin tissues, it should meet three characteristics: (1) operation at atmospheric pressure below 40 °C, (2) generation of average electron energy for impact excitation, and (3) without causing thermal damage to the skin [2, 3]. Consequently, as research on plasma medicine deepens, the rapid development of this field expands its scope of study, with skin being an excellent site for plasma treatment [2, 3]. CAP represents a distinct form of plasma characterized by operating at or proximal to room temperature and under atmospheric pressure conditions. Unlike conventional plasmas that typically function at elevated temperatures and low pressures, CAP offers a unique profile by operating at temperatures conducive to room conditions. This attribute renders it particularly applicable in diverse domains, including medical, material processing, and surface treatment, where concerns about excessive heat are pertinent. CAP’s operation at atmospheric pressure is significant, obviating the need for vacuum systems and allowing for facile generation and sustenance in open-air environments. This accessibility enhances its practical utility across various settings.

The applications of CAP are broad and encompass medical aspects, such as wound healing, sterilization of medical apparatus, and potential applications in cancer treatment [17]. Additionally, CAP finds utility in material processing, where it contributes to the enhanced adhesion and modification of surface properties, as well as in sterilization procedures, leveraging its capacity to generate reactive species effective against bacteria and microorganisms. Diverse methodologies are employed in CAP generation, including dielectric barrier discharges and atmospheric pressure glow discharges, selected based on the specific requisites of the intended application. The resultant plasma generates an array of reactive species, including ions, electrons, free radicals, and excited atoms and molecules, all of which play pivotal roles in the varied applications of CAP. Ongoing research continues to explore novel applications and refine existing technologies. The capability of CAP to operate at room temperature and atmospheric pressure broadens the horizons of plasma utilization, particularly in contexts where conventional high-temperature plasmas may pose limitations. Traditional plasmas are often generated at high temperatures and low pressures, such as in stars or industrial processes [42]. However, cold atmospheric pressure plasmas are created at temperatures close to or at room temperature, making them suitable for various applications, including medicine, materials processing, and surface treatment [15–18, 43, 44].

While thermal equilibrium plasma has shown significant potential in medical applications, patients often struggle with the discomfort caused by increased skin temperature. In contrast, CAP does not induce such side effects. The CAP treatment of biological tissues is feasible, ensuring that the temperature of the treated skin remains between 37 and 38 °C [15–18]. This is attributed to the faster heating rate of electrons compared to ions in an electric field, resulting in plasma generation at room temperature or close to it [2]. Common discharge forms of CAP in laboratories include glow, spark, corona, DBD, sliding arc discharge, microwave, radiofrequency, etc. [4, 45, 46]. CAP devices can be categorized into three types: direct plasma source, indirect plasma source, and mixed plasma source. Direct plasma sources use the human body (skin or internal tissues) as an electrode. In contrast, indirect plasma sources involve exciting plasma between two electrodes, with the active components acting on the target tissue. Mixed plasma sources combine the advantages of both types, typically achieved by using a grid-like metal electrode with lower tissue resistance [3]. DBD, a direct type of cold plasma, demonstrates efficacy in various biomedical applications by utilizing dielectric barriers [4]. The atmospheric pressure non-equilibrium plasma jet (N-APPJ), operating at atmospheric pressure, is a non-thermal biocompatible plasma source, versatile in medical, agricultural, and hygiene applications [1–5]. Other biomedical plasma sources, including surface micro-discharges and plasma brushes, present unique advantages tailored for specific medical use cases [5]. Fundamental research is ongoing to establish basic requirements for plasma sources in medicine, aiming to enhance practicality and effectiveness in medical fields [4]. Plasma health applications have emerged as a thought model in recent years, representing interdisciplinary research in medicine, biology, physics, chemistry, and engineering [1–5], with research increasingly intensifying [47, 48].

Applying cold atmospheric pressure plasma in medicine can be classified into direct and indirect forms. Direct applications include DBD and APPJ, both devices [4, 47]. Indirect plasma applications primarily involve plasma-activated liquids (PAL) to exert their effects. Plasma-activated liquids result from the interaction between plasma and liquid surfaces and include plasma-activated water (PAW), plasma-activated media (PAM), plasma-activated solution (PAS), plasma-activated oil (PAO), and plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) [49]. Even without additional chemical substances, gaseous plasma interacting with water produces unique chemical reactions and energy transfer, yielding plasma-activated water (PAW) with significant transient broad-spectrum biological activity [50], as depicted in Fig. 3. RONS play crucial roles in the dermatological application of cold atmospheric pressure plasma [12, 13]. The interaction between plasma and liquids can lead to various direct reactions at the gas–liquid interface and indirect cascade reactions in the liquid. This results in plasma-activated liquids containing a mixture of highly reactive species. Reactive nitrogen oxides (RONS) can be classified into long-lived and short-lived types [51]. Examples of short-lived species include hydroxyl radicals (OH−), singlet oxygen (1 O2), and superoxide anions (O2−), with lifetimes ranging from seconds to minutes [52]. In contrast, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), nitrous acid (HNO2), and ozone (O3) belong to long-lived species [53]. Most RONS found in the liquid phase during the indirect action of cold atmospheric pressure plasma are long-lived [51–53]. The plasma device and working gas greatly influence the type and concentration of reactive species in PALs and the liquid used [47]. Given the presence of RONS in plasma-activated liquids, they also hold potential applications in the biomedical field [1–5, 48].

Fig. 3.

The formation, penetration, and characterization of CAPs entail complex interactions influenced by chemical and physical factors. CAPs interact intricately with treated targets, generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) from atmospheric gases and water vapor. CAP exposure enriches aqueous media with species like hydrogen peroxide. Furthermore, CAP therapy influences the extracellular matrix (ECM), a crucial three-dimensional network in skin health. This interaction may modulate skin inflammation and infection, while the ECM’s role as a cell scaffold is essential for tissue development. Factors influencing species quantity include plasma settings and distance from the target. [19, 51, 53]

RONs and skin

The application of CAP in skin diseases includes direct treatment, plasma-activated water, and the activation of matrix injection. However, the epidermis acts as a natural barrier, posing a challenge to the delivery of drugs or charged active ingredients into the skin [33]. In CAP, colliding gas molecules with high-energy electrons can generate original reactive substances such as O2 and N2 molecules, N, O, and H atoms in ground and excited states, and OH radicals. Further reactions between these original substances produce RONS, including OH, NO, NO2, HNO2, HNO3, and H2O2 [51–53]. RONS play a pivotal role in the biological effects of CAP. CAP generates RONS, instigating oxidative stress and influencing various physiological processes [51–53]. RONS trigger signaling pathways associated with wound healing and antimicrobial activity. CAP’s impact extends to the immune system by modulating immune cell infiltration, notably CD8+ T cells, CD3+ cells, and CD11c+ cells [54]. These cells orchestrate inflammatory responses and participate in tissue repair mechanisms [54, 55]. Furthermore, CAP influences the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, potentially ameliorating inflammatory skin conditions and contributing to overall skin health [52–55]. Regarding skin regeneration, CAP fosters a regenerative response characterized by enhanced collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and epithelialization. These processes expedite wound healing and tissue repair [37]. CAP exhibits selective cytotoxicity, inducing apoptosis in cancerous or infected cells while sparing healthy tissues. This targeted approach holds promise for treating skin cancers and infections [24, 28, 31]. Moreover, CAP alters the lipid composition of the skin, potentially bolstering its barrier function. This alteration is particularly advantageous for individuals with dermatitis, offering relief and protection [1, 13, 16]. The transport of active particles from CAP to the skin includes two pathways: transdermal plasma delivery (plasma puncture) and tissue penetration [53–55].

Transdermal plasma delivery occurs when the electric field of the plasma generates a voltage drop on the skin, with most of the voltage drop applied to the high-resistance stratum corneum. When the surface potential reaches the driving voltage, this distribution leads to corneum breakdown [49, 53–55]. The CAP air plasma directly applied to the skin surface generates an electric field of about 170 kV cm−1 between the skin surface and the underlying layers, eventually penetrating the skin and forming holes [14]. When CAP acts on the skin, it generates rapid but mild heat, which breaks down the lipid structure of the stratum corneum, thereby increasing skin permeability without damaging deeper tissues and improving transdermal delivery [53–57]. Simultaneously, CAP perforation promotes the transfer of NO generated on the skin surface to the skin tissue, ultimately leading to increased vasodilation, blood flow, and tissue oxygenation [19].

The penetration of active particles from CAP into tissues includes penetration through tissue moisture and direct interaction with skin tissues [58]. The RONS produced by CAP must pass through three barriers before entering cells: the plasma–tissue fluid barrier, fluid–tissue barrier, and tissue–cell barrier [14]. CAP affects liquids by changing liquid surface dents and flow patterns, making the liquid surface charged, causing convection, etc., which promotes the entry of active ions into the liquid phase [59]. The direct effect of CAP on skin tissues has been mainly studied through gelatin and agarose models. The results show that CAP jets can penetrate 150 μm gelatin directly and detect plasma effects up to 4 mm in agarose models [19]. In addition, the active components generated by CAP can create nano-sized pores in the phospholipid bilayer and disrupt the phospholipid bilayer structure, facilitating the entry of RONS into cells [14].

Various methods have been explored to enhance medication absorption into the human skin. Non-thermal biocompatible plasma (NBP) enhances medication absorption into human skin. A recent study examined the potential of NBP in improving the absorption of medications into human skin. The study investigated the effect of NBP on niacinamide permeation, revealing that NBP-treated skin exhibited a significant 60-fold higher penetration rate than untreated skin. The enhanced transdermal absorption was observed from 0.5 to 6 h, continuing over a 12-h incubation period. Plasmaporation, a result of NBP treatment, was identified as the primary contributor to this increased permeability. Findings suggest that NBP is a potential candidate for improving cosmetic and pharmaceutical delivery applications [55, 56].

Plasmaporation is the cornerstone mechanism driving the efficacy of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) in dermatological applications. This term encapsulates the transdermal electric fields and conduction facilitated by gas plasmas, pivotal in CAP’s therapeutic interventions for various skin ailments [56]. Plasmaporation’s significance lies in its multifaceted impact on dermatology. By harnessing radical species and electric fields, CAP induces diverse physiological responses that are beneficial for treating skin diseases. Notably, CAP aids in wound healing, inflammation reduction, and tissue regeneration [56]. Understanding plasmaporation elucidates CAP’s prowess in dermatology. Its ability to permeate skin barriers non-invasively while promoting healing processes underscores its clinical relevance and potential for future therapeutic advancements [56].

In recent research, an atmospheric pressure plasma jet (APPJ) was topically applied to the skin, and the resulting electric field in different skin layers was meticulously measured using optical methods [57]. Another study delved into the synergistic effects of nanosecond pulsed atmospheric pressure plasma jets (ns-APPJ) in combination with pulsed electric fields, evaluating their efficacy for bacterial inactivation [58]. Electric field measurements in atmospheric pressure plasmas were explored through various methods, including optical emission spectroscopy [59]. Additionally, the electric field profile in a kHz atmospheric pressure plasma jet was investigated concerning the influence of a target [59]. These studies contribute to understanding atmospheric pressure plasma jets’ diverse applications and characteristics in different contexts. Kalghatgi, Tsai, Gray, and Pappas explored the application of atmospheric pressure non-thermal dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma for transdermal drug delivery without causing thermal or structural damage. Initial experiments using dextran molecules demonstrated the feasibility of enhancing drug delivery across porcine skin. Non-thermal DBD plasma, applied for 1 min at a power density of 10 W/cm2, significantly improved the transdermal delivery of 3 kDa dextran molecules without inducing thermal damage, reaching the epidermal layer at a depth of approximately 300 μm within one hour [60]. Further experiments revealed that 1 min cold plasma exposure enabled the transdermal delivery of larger molecules, including 10 and 70 kDa dextran molecules, SiO2 nanoparticles, and proteins, to considerable depths within one hour. The study also addressed the challenge of delivering drug delivery vehicles like liposomes and micelles, highlighting the potential of non-thermal plasma to transport 100 nm liposomes transdermally, surpassing the efficacy of electroporation without associated side effects [61]. The authors hypothesized that non-thermal plasma achieves transdermal drug delivery through ‘plasmaporation’, involving the temporary formation of pores in the stratum corneum. This method presents a non-invasive, safe approach for transdermal delivery and the cellular uptake of molecules, drugs, and vaccines at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, with additional benefits such as concurrent skin sterilization and eliminating biohazardous waste.

Moreover, research conducted by the Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology and the Institute of Pharmacy at the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University of Greifswald, Germany, delves into the interactions between plasma and biological systems. Notably, the study reveals that biological effects are not solely a result of direct plasma–cell or plasma–tissue interaction but are mediated by liquids. When treated by atmospheric pressure plasma, simple liquids like water or physiological saline exhibit antimicrobial activity attributed to generating lowly reactive molecular species. The findings also indicate that plasma treatment stimulates specific aspects of cell metabolism and temporarily enhances the diffusion properties of biological barriers. The authors introduce a new field, “plasma pharmacy”, focusing on potential applications such as generating biologically active liquids, optimizing pharmaceutical preparations, supporting drug transport across barriers, and stimulating biotechnological processes [62]. The article underscores the potential of plasma in revolutionizing pharmaceutical practices, providing innovative avenues for drug development, delivery, and therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, Daeschlein et al. [63] investigated the comparative efficacy of cold plasma treatment, electrochemotherapy (ECT), and their combined therapy in a melanoma mouse model. The results demonstrated that the combined therapy, precisely the combination of ECT and argon-fed jet plasma (ECJ), exhibited superior effectiveness in delaying tumor growth kinetics (TGA) and reducing the tumor volume (DVP) compared to individual treatments with either cold plasma (CP) or ECT alone. The survival analysis further revealed a significant improvement in survival days after ECJ treatment, showcasing its potential as a novel palliative adjunct for advanced melanoma with skin and soft tissue metastases. The experimental outcomes indicated that ECJ achieved the highest percentage survival rates, with 100% survival after 38 days and 55% after 46 days post-treatment. In contrast, ECT alone showed 80% survival after 38 days and 40% after 46 days. The study also highlighted the limitations, such as the small number of mice in each treatment group, emphasizing the need for more extensive trials to confirm the observed results. Despite the promising findings, the study acknowledged the ongoing investigation into the mechanisms underlying the interaction between cold plasma and cancer tissue, emphasizing further research to elucidate the potential synergistic effects of cold plasma in combination with electrochemotherapy [63].

Interestingly, in a recent study led by Sohail Mumtaz and colleagues, a novel approach was explored to enhance the efficiency of plasma usage time in medical applications. This innovative method sought to optimize the duration of plasma exposure, focusing on improving its effectiveness in medical settings. The investigation delved into the influence of varying plasma exposure durations while maintaining a constant duty ratio on generating reactive species within plasma-treated media. Given the pivotal role of these reactive species in biological applications, the study underscored the significance of studying and optimizing plasma on time. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma (NTAPP) typically denotes low-temperature plasma operation, minimizing environmental heating. Conversely, CAP explicitly emphasizes the absence of substantial temperature increase during its generation. Current biomedical research is concentrated on optimizing the therapeutic range of NTAPP [64]. This study examined the effects of varied plasma times while keeping duty ratios and treatment times constant [64]. The evaluation encompassed electrical, optical, and soft jet properties at 10 and 36% duty ratios, with plasma on-times ranging from 25 to 100 ms [4]. Additionally, the study probed the impact of plasma on time on reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) levels in a plasma-treated medium (PTM) [4]. Following treatment, characteristics of DMEM media and PTM, including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), were scrutinized [64]. EC and ORP increased with extended plasma on time, while pH remained constant [64]. Subsequently, the investigation assessed cell viability and ATP levels in U87-MG brain cancer cells using PTM. Interestingly, increased plasma on time significantly elevated ROS/RNS levels in PTM, influencing the viability and ATP levels of U87-MG cells [64]. These findings mark a significant advancement by introducing plasma on-time optimization to enhance the efficacy of soft plasma jets in biomedical applications [4]. Modifying ROS/RNS levels through varied plasma on-times within fixed duty ratios and treatment times presents a promising avenue for further exploration [64].

The application of CAP in dermatology

In contemporary dermatology, CAP has gained recognition for its diverse applications, demonstrating potential benefits in treating various skin conditions. Studies by Bernhardt et al. highlight CAP’s capacity to positively affect atopic eczema, itch, and pain, suggesting a promising therapeutic avenue [2]. Furthermore, a systematic review underscores the effectiveness of CAP in providing therapy for various skin diseases [13, 22, 23]. The emerging potential of CAP for dermo-cosmetic treatments, including aging prevention, has been acknowledged [19].

This evolving landscape underscores the multifaceted role of CAP in dermatology, with ongoing research exploring intricate mechanisms and expanding clinical applications [2, 13, 19, 22, 23]. Recent investigations contribute to a nuanced understanding of CAP’s impact on skin health. Additionally, CAP has demonstrated promising applications in dermatology, showing efficacy in inducing pro-apoptotic effects more efficiently in tumor cells compared to benign counterparts, highlighting its potential for targeted therapy in skin-related conditions [1, 25–28]. Recent studies further suggest that CAP can ameliorate various skin diseases, showcasing its therapeutic potential in dermatology [1–3, 17]. Its emerging role in skin therapy presents a novel approach with potential benefits in clinical dermatology, supported by achievements and ongoing research [1–3, 17].

Plasma, formed by ionizing gas under heat or a strong electromagnetic field, constitutes a cloud of charged particles, including electrons, ions, metastable species, ultraviolet light, visible light, electromagnetic fields, and reactive substances [1–3]. Due to its equal distribution of positive and negative charges, plasma represents the fourth state of matter alongside solids, liquids, and gases. Plasmas can be categorized into thermal, warm, and cold plasma based on gas temperature. CAP, a non-equilibrium plasma applicable in medical contexts, occurs at atmospheric pressure with significantly higher electron temperatures than gas temperatures yet remains tolerable for the human body [5].

Despite the diverse components generated within the plasma, reactive nitrogen oxides are the key active agents. Plasma exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial action, cell proliferation, tissue regeneration stimulation at low doses, and programmed cell death (apoptosis) induction at high doses [53]. Since the twentieth century, researchers have utilized plasma to eradicate bacteria, leading to the emergence of plasma medicine. Currently, plasma medicine finds widespread application and exploration in medical device sterilization, dentistry, oncology, dermatology, and other fields [1–3, 17].

CAP’s suppressive effect on microbial infection

Infectious skin diseases

The application of CAP has garnered significant attention due to its remarkable oxidative capabilities mediated by RONS. Various studies have highlighted the potent antimicrobial properties of CAP and plasma-activated liquids against different microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites [17, 21, 24, 35]. Compared to traditional antibiotics, CAP offers distinct advantages, such as a reduced likelihood of inducing drug resistance and minimal toxicity [65]. Notably, CAP’s efficacy extends to inhibiting microbial infections on diverse surfaces, encompassing non-living surfaces, biofilms, and bacteria and fungi within contaminated or infected tissues [66].

Maisch et al. conducted a comprehensive investigation into the inhibitory effects of CAP on Gram-positive (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli) [67]. Their study involved inoculating bacteria on the skin surface of six-month-old pigs, followed by CAP treatment. The results indicated that a 6-min CAP treatment achieved a sterilization rate of 99.9% for Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. In contrast, a 4-min treatment was effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Importantly, no discernible morphological changes in tissues and cells indicated CAP’s safety [67].

Further insights into CAP’s inhibitory mechanisms were proposed by Mai-Prochnow et al. [68]. They suggested that CAP components, including reactive oxygen and nitrogen, act directly on cell walls or membranes. Reactive oxygen triggers lipid peroxidation reactions, deactivating iron-dependent dehydrases, destruction of monocyte cell iron proteins, and DNA damage, ultimately causing cell deactivation [68]. Dezest et al. [69] explored CAP’s inhibitory effect on Escherichia coli, revealing that CAP induced bacterial death by altering the bacterial structure and initiating oxidative stress reactions. The study emphasized complex interactions, including electric field and ion effects [69].

CAP’s broad-spectrum antimicrobial mechanism, disrupting biofilm matrices and inactivating bacterial quorum sensing signals, presents a challenge for bacteria in developing resistance [70, 71]. In a study of diabetic foot infections, CAP significantly reduced bacterial loads in chronic diabetic foot ulcers, leading to improved wound healing [72]. The CAP-treated group exhibited a lower incidence of systemic inflammatory responses and required fewer surgical interventions, highlighting the potential applications of CAP in treating chronic diabetic foot infections [73]. These findings collectively underscore the promising role of CAP in combating infectious diseases with unique advantages over conventional treatments.

Effects of CAP on bacteria

Extensive in vitro and in vivo research has unequivocally demonstrated atmospheric pressure cold plasma’s direct inhibitory and bactericidal effects on bacteria and their biofilms [63, 66, 74]. In both settings, applying atmospheric pressure cold plasma has proven effective in inhibiting and destroying bacteria and disrupting biofilm structures [75]. Notably, plasma-activated liquids (PALs) have emerged as a promising avenue for bacterial eradication, with studies showcasing their efficacy against common strains such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae [76, 77]. The mechanism behind this antimicrobial action involves the generation of RONS in plasma-activated water (PAW), impacting the oxidation–reduction status of antioxidants, penetrating bacterial cell membranes, disrupting cell structures, and ultimately leading to bacterial death [78, 79]. Furthermore, investigations by Liu et al. [80] underscore the potential of plasma-activated saline in modulating inflammatory factors and genes, altering the morphological structure of pathogens, and enhancing the host’s immune response against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, thereby illustrating its therapeutic promise in addressing infections associated with biofilms.

Biofilms, intricate communities of microbial cells (bacteria and fungi) adhered to various surfaces, present a formidable challenge for traditional antibiotics, disinfectants, and standard immune clearance methods [81]. Their complex structures contribute to chronic and persistent infections, as these conventional approaches often have limited efficacy against biofilms. The dynamic and prolonged presence of RONS generated by plasma-activated water (PAW) is pivotal in disrupting biofilm structures, rendering bacteria more susceptible to elimination [82, 83]. This innovative approach capitalizes on the unique properties of PAW to address the challenges posed by biofilms, offering a promising avenue for treating biofilm-associated infections. The interdisciplinary nature of this research, spanning microbiology, chemistry, and immunology, underscores the multifaceted potential of atmospheric pressure cold plasma and plasma-activated liquids in revolutionizing our approach to combating bacterial infections and biofilm-related complications.

Effects of CAP on fungi

Various fungi, encompassing dermatophytes, Candida, molds, and spore-forming fungi, have the potential to induce skin infections, with nail fungal infections, particularly onychomycosis, posing a clinical challenge due to the dense structure of the nail plate, leading to low drug concentrations and extended treatment durations. Exploratory research has showcased the efficacy of plasma in combating the causative agents of nail fungal infections across pathogen models, detached nail models, and clinical trials [1, 84, 85]. White Candida albicans and Trichophyton mentagrophytes treated with atmospheric pressure plasma jet (APPJ) displayed inhibited growth, reduced adhesion, and decreased infectivity in a nail model [86, 87]. Furthermore, findings for other dermatophytes, such as Epidermophyton floccosum and Trichophyton verrucosum, affirmed that CAP can impede the growth and infection of skin fungi [88, 89]. In a pilot study involving 19 participants with nail fungal infections, the overall clinical cure rate was 53.8%, and the mycological cure rate was 15.4%, with high patient satisfaction and no significant or prolonged adverse reactions, establishing atmospheric pressure cold plasma as a safe method for treating nail fungal infections [90]. In a cohort of 40 patients with nail fungal infections, the integration of atmospheric pressure cold plasma therapy with nail plate ablation and refreshment (NPAR) or antifungal drug treatment resulted in clinical cure rates exceeding 70%, and mycological cure rates increased to 85.7% [90]. Cold plasma emerges as a promising alternative therapy for skin fungal infections, with longer plasma treatment times associated with more potent inhibition by plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) compared to plasma-activated water (PAW) [91], offering a potential novel approach for future treatments of skin fungal diseases.

Effects of CAP on viruses and parasites

Reports suggest that atmospheric pressure cold plasma has some antiviral effects [92]. However, its current utilization in dermatology is relatively limited. Friedman et al. [93, 94] reported positive outcomes in treating viral warts using cold plasma in two adults and five pediatric patients. Bunz et al. [95] observed cold plasma’s lower but measurable antiviral effect on HSV-1. Further exploration is required to investigate the impact of other atmospheric pressure cold plasma devices and parameters on viruses. Furthermore, studies have shown the efficacy of plasma against parasites like Demodex mites and head lice. Malik et al. [96] conducted a half-face survey of three patients with rosacea, comparing bi-weekly cold plasma treatment with daily topical ivermectin. The proportion of Demodex mites in the follicles and the total number decreased significantly in the ivermectin and cold plasma treatment sites without adverse reactions. Bosch et al. [97] developed an atmospheric pressure cold plasma device designed by Professor A. Schulz, who leads product and industrial design at HAWK. This device, resembling a comb (CAPComb), treats head lice. The results indicated that a single application of a plasma comb on hair could cause death to lice and eggs. The study concluded the safety of the plasma comb based on ozone concentration, UV emission rate, and leakage current.

CAP promotes tissue proliferation and wound healing

The effectiveness of CAP in wound healing is evident, showcasing its abilities to foster antiseptic properties and pro-angiogenic effects. Furthermore, CAP exhibits notable efficacy in promoting tissue proliferation, thereby contributing significantly to the overall process of wound healing [98, 99]. Researchers, including Hasse et al., explored the impact of CAP on skin wounds. In their study, tissue samples with a 5 mm diameter were extracted from normal human skin and subjected to CAP irradiation [100]. The results revealed that a 1 to 3 min CAP exposure stimulated cell proliferation, promoting epidermal repair and wound healing. Interestingly, partial cell apoptosis was observed after 3–5 min of CAP exposure. Another study by Arndt et al. [101] investigated the influence of CAP on gene expression in keratinocytes, the cells responsible for skin barrier formation. Using MicroPlaster-β to generate CAP, they treated wounds and found that CAP induced the expression of genes coding for interleukin (IL)-8, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, and TGF-β2. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that keratinocytes’ proliferation, migration, and apoptosis processes were not significantly affected during wound healing. The experiments highlighted the time-dependent nature of CAP in promoting wound healing. Within specific timeframes and doses, CAP could stimulate the expression of cell factors related to wound healing without compromising the activity of keratinocytes. This underscores CAP’s potential to facilitate wound healing effectively. The results showed that CAP treatment significantly accelerated wound healing compared to the control group. Specifically, CAP increased re-epithelialization, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen synthesis while reducing the inflammatory response. CAP has a promoting effect on cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis [101]. Researchers found that CAP significantly promoted cell proliferation and the release of growth factors and chemokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), by activating fibroblasts. Vascular endothelial growth factor is crucial for angiogenesis and wound healing, while fibroblast growth is essential for tissue repair and regeneration [102]. The promoting effect of CAP on wound healing has also been confirmed in a study on human skin wounds. Rat skin wounds were treated with CAP, and the results showed increased angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, and collagen synthesis [20]. These findings suggest that CAP can accelerate wound healing by promoting cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and the release of growth factors. It stimulates skin cell proliferation and migration [103, 104]. While a meta-analysis suggested limited clinical benefit for chronic wounds, smaller studies have associated CAP with positive outcomes, including improved wound infection and healing [105]. Moreover, atmospheric pressure cold plasma can facilitate wound healing through other mechanisms. In a randomized clinical trial by Stratmann [106], cold plasma therapy accelerated the healing of chronic wounds. However, there was no significant difference in microbial load between atmospheric pressure cold plasma and placebo groups. Even before this clinical trial, atmospheric pressure cold plasma therapy had been proven beneficial for chronic wounds, not solely due to its antibacterial effects [105, 106]. Nevertheless, basic research indicates CAP’s ability to eliminate refractory skin bacteria in vitro and positively impact wound healing in rat models [107]. Considering the significant role of CAP in treating bacterial infections, it can promote wound healing by significantly reducing bacterial load in the treated wounds, ensuring safety [105, 106].

Moreover, CAP can facilitate wound healing through other mechanisms. Over the past decade, a series of in vitro studies have indicated that plasma-triggered wound healing depends on stimulating cell proliferation and survival [53, 54], synthesis of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [108–110], changes in adhesion proteins and cytoskeletal structures [111–113], and apoptosis of cells [114, 115]. Additionally, some studies suggest that atmospheric pressure cold plasma treatment can induce genes involved in wound healing [116] and facilitate oxidative-reductive regulation of known critical targets for wound healing [117–121]. To ensure a more uniform treatment of wounds, many scholars have further investigated the mechanisms and applications of plasma-activated liquids in wound treatment, as depicted in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Gas plasma treatment effects on wound healing targets. Gas plasma treatment influences key cells (keratinocytes, fibroblasts, immune cells) in and around the wound bed, reducing microbial growth. It stimulates keratinocytes and fibroblasts, activates macrophages, and attracts neutrophils and lymphocytes toward the damaged tissue [7]

They found that plasma-activated water (PAW) could accelerate wound healing by reducing bacterial counts in treated wounds [7, 118]. In their study, Lee et al. [118] cultured keratinocytes with plasma-activated media (PAM) and treated a mouse model with PAW. PAM treatment promoted the transformation and migration of keratinocytes, attributed to changes in the expression of integrin-dependent focal adhesion molecules and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The study also identified increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels as a driving force for cell migration, regulated by NADPH oxidase and changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. In in vivo experiments using a full-thickness acute skin wound model in mice, PAW treatment contributed to an increased re-epithelialization rate, emphasizing the activation of potential intracellular ROS-dependent signaling molecules. Zou et al. [119] produced plasma-activated oil by treating olive oil with cold plasma. PAO not only killed bacteria on the wound but also promoted the release of growth factors such as CD34 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), resulting in a 28.5% faster wound healing rate than the control group. Applying plasma-activated liquid in a fibroin-silk fibroin (SF) composite hydrogel showed that plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) significantly enhanced the healing of radiation-induced wounds. Cell and tissue responses to PAH promoted the regenerative process of wounds, while atmospheric pressure cold plasma also improved the mechanical and chemical properties of SF gel [120].

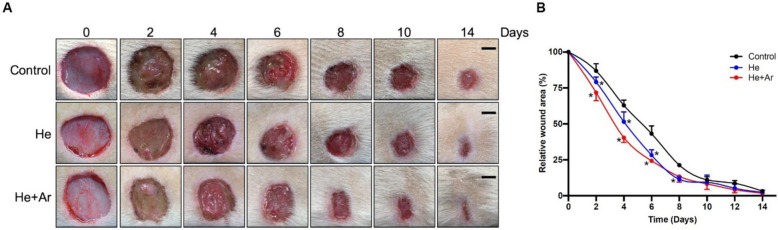

Moreover, a study by Lou indicated the efficacy of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) in accelerating wound healing. The scientists employed He-CAPJ and He/Ar-CAPJ jet plasmas toward rats’ wounds as models for 60 s. As shown in Fig. 5, there were measurements of wound closure on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 14. Compared to the untreated control group, a considerable decrease in the size of wounds was observed within the treated plasma experimental groups. These pictures indicated a significant wound contraction with noticeable improvements from day 8 to 14, particularly in those treated with helium–argon (He/Ar-CAPJ). Additionally, it was confirmed by the measurement of the wound area that the He/Ar-CAPJ treatment had faster wound closure at early stages (days 2–8) than He-CAPJ.

Fig. 5.

A study by Lou et al. explored how helium/argon cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) influences wound healing in rats. Wound closure was measured on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 14 after applying He-CAPJ and He/Ar-CAPJ for 60 s. Results showed significant wound reduction in plasma-treated wounds compared to the control group. Pronounced wound contraction occurred after He/Ar-CAPJ treatment between days 8 and 14, with better wound closure results than He-CAPJ from days 2 to 8. The study also evaluated wound closure after treating the wounds with He/Ar-CAPJ for 1, 3, and 5 min.

Reproduced with permission from Ref. [121]. Copyright 2020 Frontiers

It was an experiment involving three groups: control, He-CAPJ, and He/Ar-CAPJ, each consisting of six animals equaling eighteen rats. Furthermore, figures showed images from the healing process where a statistical analysis revealed significant improvement between (*P < 0.05) in plasma-treated groups, especially in the He/AR CAP group [121]. These findings indicate that if more research is carried out on CAP’s ability to enhance wound healing, it can become a viable option for treatment or intervention.

CAP for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases

CAP regulates the formation of stratum corneum cells through the reactive oxygen pathway [122]. Stratum corneum cells play a crucial role in maintaining skin barrier function. Research indicates that CAP modulates the redox balance, inducing alterations in the structure and function of stratum corneum cells [123]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that CAP can improve symptoms by reducing skin inflammation and restoring the normal differentiation of stratum corneum cells [85]. The redox-sensitive transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) plays a key role in mediating the effects of CAP on stratum corneum cells. CAP activates NRF2, leading to the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes and the restoration of redox homeostasis in stratum corneum cells [84]. The modulation of NRF2 by CAP may represent a novel therapeutic approach for skin diseases characterized by oxidative stress and inflammation [122–125]. CAP exerts its effects by regulating cell viability, proliferation, migration, and inflammatory responses, offering a novel approach to managing Inflammatory skin disorders [121–125].

Psoriasis

Gan et al. [1, 126], the therapeutic effects of CAP on psoriasis were investigated through cellular and animal experimentation. To simulate a psoriatic cell model, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) was introduced into human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT cells), and the cells were cultured with plasma-activated medium (PAM). Subsequently, an atmospheric pressure plasma jet (APPJ) was directly applied to a mouse model of psoriasis induced by imiquimod. Results showed that PAM increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HaCaT cells, leading to cell apoptosis. Interestingly, imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis exhibited gradual improvement following APPJ treatment, demonstrating reduced epidermal hyperplasia and thinning of the epidermal layer. The ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) generated by cold plasma inhibited excessive proliferation of keratinocytes, promoting apoptosis. Moreover, it suppressed the proliferation of T lymphocytes and enhanced the expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which negatively correlates with T lymphocyte proliferation [127]. Furthermore, ROS and RNS directly regulated the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-12, and VEGF at the site of skin lesions, contributing to the alleviation of psoriasis [128]. Case reports also indicated satisfactory outcomes in treating inverse psoriasis and recalcitrant palmoplantar psoriasis using atmospheric pressure cold plasma [129, 130]. Kim et al. [61] developed atmospheric pressure cold plasma patches for treating psoriatic skin lesions. These patches produced ROS and RNS on flexible polymer film surfaces using surface dielectric barrier discharge. The patches alleviated psoriasis symptoms by inducing the opening of calcium ion channels in keratinocytes and mitigating the effects of the electric field [131].

Atopic dermatitis

Researchers have explored the therapeutic effects of atmospheric pressure cold plasma on different mouse models of atopic dermatitis (AD), demonstrating positive outcomes in alleviating skin inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and oxidative stress [132, 133]. Scholars have explored the positive effects of treating AD mice models with non-thermal atmospheric plasma; cold plasma reduced skin cell apoptosis in a mouse model induced with dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB). It alleviated skin inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and oxidative stress mediated by plasma-induced MANF expression [134].

Furthermore, localized treatment with cold plasma in a mouse model induced by house dust mite extract decreased the severity of dermatitis, transepidermal water loss (TEWL), and serum IgE levels [132]. In another dust mite AD model, plasma inhibited the increase in epidermal thickness recruitment of mast cells and eosinophils and reduced the expression of AD-associated cytokines and chemokines [135]. Choi et al. demonstrated the positive effects of cold plasma on keratinocytes stimulated with pro-inflammatory cytokines and in AD model mice induced by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). The study suggested that non-thermal plasma could improve AD by modulating NF-κB activity [136]. Microbiome analysis further indicated a significant reduction in the proportion of Staphylococcus aureus in the treated group [137].

Vitiligo

As of the most recent advancements in dermatology, there have been notable updates in the application of CAP for treating vitiligo. This innovative therapeutic approach harnesses the power of low-temperature plasma to stimulate repigmentation in areas affected by vitiligo, a chronic skin disorder characterized by depigmented patches. Research studies and clinical trials have shown promising results, highlighting the potential of CAP in enhancing melanocyte activity and promoting the restoration of normal pigmentation [138]. Zhai et al. [139] conducted a study on the efficacy and safety of PAH (cold atmospheric plasma) in vitiligo, utilizing mouse models and patients with active focal vitiligo. Skin biopsies revealed that local treatment of vitiligo-like lesions on the dorsal skin of mice with cold atmospheric plasma restored melanin distribution. This treatment led to a reduction in T cells and dendritic cell infiltration and a decrease in the release of inflammatory factors. The study observed an enhancement in the expression of the transcription factor NRF2 and a reduction in inducible nitric oxide synthase activity, thereby increasing cellular resistance to oxidative stress and excessive immune responses. In this randomized controlled trial, atmospheric pressure cold plasma treatment achieved partial and complete pigmentation in 80 and 20% of vitiligo skin lesions. Notably, during the treatment and follow-up periods, there were no occurrences of pigmentation or other adverse events in the surrounding areas [139].

CAP suppresses tumor cell proliferation and migration

The research on the use of plasma in treating tumors has rapidly expanded from cellular studies to animal models [140, 141]. Among various potential anti-tumor mechanisms, apoptosis induced by cold atmospheric plasma under atmospheric pressure has been extensively studied [142, 143]. This process involves the activation of different signaling pathways, including MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, leading to cell death [144]. Other possible mechanisms include the induction of autophagy [145, 146], pyroptosis [147], ferroptosis [148, 149], and the regulation of cancer cell metabolism [150], which can cause cell cycle arrest, DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction [151].

Studies indicate exceptional responsiveness of melanoma cells to cold plasma, with melanoma cells exhibiting higher sensitivity to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) induced by cold plasma compared to normal skin cells [152]. This heightened sensitivity suggests cold plasma’s potential applicability and safety in anti-cancer treatments [152]. Researchers investigated the inhibitory effect of CAP on melanoma cells in vitro. The study found that CAP could induce apoptosis in melanoma cells, significantly increasing intracellular ROS levels [153]. CAP treatment also caused DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and reduced cell migration. Furthermore, CAP inhibited the growth of melanoma xenografts in mice, demonstrating its potential as a novel therapy for melanoma. Another study investigated varying the induction of apoptosis or senescence in melanoma tumor cells in response to different doses of a novel cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) device, revealing a previously undocumented mechanism of senescence critical for the therapeutic potential of CAP [145]. Many studies indicate melanoma cells react remarkably to cold plasma [154–157]. When normal skin and melanoma cells are treated with cold plasma, melanoma cells show higher sensitivity to the RONS induced by cold plasma, making cold plasma applicable and safe in cancer therapy [158].

Clinical demonstrations have also highlighted CAP’s effectiveness in treating actinic keratosis (AK), a pre-cancerous skin condition, emphasizing its potential as a therapeutic intervention for pre-cancerous lesions and contributing to the evolving landscape of dermatological care [159]. Moreover, skin tumors include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and there is also a significant effect of using atmospheric pressure cold plasma indirectly [160, 161]. In a study on skin squamous cell carcinoma, CAP inhibited tumor cell proliferation and induced apoptosis through the generation of ROS [159–161]. Additionally, CAP reduced squamous cell carcinoma cells’ invasive and migratory abilities, suggesting its potential as an adjuvant therapy for skin cancer. CAP-induced apoptosis in tumor cells is thought to be related to the selective activation of pro-apoptotic pathways while sparing normal cells. The increased sensitivity of tumor cells to CAP-induced apoptosis may be attributed to their higher intracellular ROS levels, making them more susceptible to additional oxidative stress [159–161]. The anti-tumor effects of CAP have also been demonstrated in other types of cancer, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer [162, 163].

Wang et al. studied the effects of plasma-activated medium (PAM) on squamous cell carcinoma cells and its mechanisms [164]. They chose the A431 epidermal cancer cell line and cultured A431 cells with PAM for two hours. The results showed that PAM increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in a dose/time-dependent manner and reduced A431 cell proliferation. Furthermore, PAM induced apoptosis in A431 cells. Another group of researchers prepared PAM using atmospheric pressure cold plasma irradiation with DMEM and PBS. The in vitro treatment of TE354T cells with PAM showed that PAM induced apoptosis signals in basal cell carcinoma cells, and this effect was associated with the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [165]. However, due to the penetration ability of atmospheric pressure cold plasma ranging from nanometers to millimeters [166], it is not easy to penetrate deep into tissues. PAM has strong flowability, making it difficult to control its range of action inside the body, and it can be diluted. Plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) can help overcome some clinical limitations and provide a convenient carrier to combine cold plasma with existing drugs, enhancing treatment response and contributing to the clinical translation of cold plasma. A review offers practical considerations and prospects for the development of PAH by integrating expertise in biomaterials and plasma medicine [167]. Zhang et al.’s study indicates that plasma-activated thermosensitive biological hydrogels can eliminate residual tumor tissue after surgical resection, inhibit in situ recurrence, and exhibit no apparent systemic toxicity [168]. The biological hydrogel has excellent storage capacity, can slowly release plasma-generated ROS, and demonstrates sound ROS-mediated anti-cancer effects in vitro. The research results indicate that this novel plasma-activated biological hydrogel is an effective therapeutic agent for postoperative local cancer treatment.

Cosmetic and skincare applications of CAP

Microplasma radiofrequency technology, acting through thermal effects and high-energy generation, has been clinically used to treat atrophic scars and seborrheic keratosis [169–171]. Meanwhile, atmospheric pressure cold plasma at room temperature also finds applications in beauty [172]. Stretch marks or striae are common skin lesions, typically caused by rapid changes in body weight, hormonal imbalance, or the excessive use of steroids [2, 173, 174]. In Suwanchinda’s clinical study, 23 patients with striae distensae were divided into two halves. One side received bi-weekly CAP treatment for five sessions, followed by a 30-day follow-up, while the other half remained untreated [175]. In a separate clinical trial conducted by Suwanchinda on hypertrophic scars, objective assessment demonstrated noteworthy enhancement in color, melanin, hemoglobin, and texture on the treated side compared to the untreated side, except for volume. Patient satisfaction levels were 72.2% moderate, 11.1% significant, 11.1% slight, and 5.6% reported no change. Notably, only one patient reported a small scab as an adverse effect. Following atmospheric pressure cold plasma treatment, diverse subjective and objective indicators exhibited significant improvement [176].

Moreover, the ROS in plasma alters the connective network, promotes tissue oxygenation, oxidizes sebaceous lipids, and limits the penetration of the model drug curcumin. This suggests that plasma may provide a new, sensitive tool for regulating the skin barrier, offering a novel treatment for sensitive and barrier-damaged skin [18, 110, 147]. In a study, researchers designed a portable atmospheric pressure cold plasma device for skin regeneration and studied its effects on rat skin when combined with vitamin C ointment. Mechanical measurements showed positive effects of atmospheric pressure cold plasma on treated tissues compared to the control group. Additionally, changes in collagen levels and epidermal thickness were examined histologically. The results showed increased collagen levels after plasma treatment alone, and the skin response was accelerated when both were used. After applying high-voltage cold plasma, the thickness of the epidermis increased, indicating improved skin elasticity. This research suggests that using a portable plasma device combined with vitamin C ointment positively affects skin beauty [177].

CAP’s role in treating immune-mediated skin diseases

Immune skin diseases are diseases caused by the imbalance of immune regulation, affecting the body’s immune response [178]. Among them, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo are highly prevalent and representative immune skin diseases. CAP has been reported to have a specific therapeutic effect on these diseases in laboratory and clinical settings. Researchers have conducted a series of studies to explore the therapeutic effects of CAP on psoriasis. The results showed that CAP jets alleviated imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in mice, and in vitro experiments showed that CAP upregulated ROS levels in HaCaT cells and induced apoptosis [126]. In addition, our developed CAP jet array enhanced the transdermal delivery of drugs, and its combination with topically applied Tripterygium glycosides significantly reduced imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in mice [179]. The active components RONS in CAP inhibit the excessive proliferation of keratinocytes and promote their apoptosis. They can also inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation by upregulating the expression of PDGL1 protein [127, 180].

In addition, ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) can directly stimulate the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-12, and VEGF within skin lesions, thereby alleviating psoriasis [128]. Clinical experiments have also reported the effectiveness of CAP in the treatment of psoriasis: a cold plasma patch used for treating psoriatic skin lesions blocks discharge-induced ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) on the surface of flexible polymer films, thereby regulating calcium channels in keratinocytes to alleviate psoriatic skin lesions [131]. Reports show that handheld dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma devices have achieved good clinical results in treating two cases of inverse psoriasis and one of palmoplantar psoriasis [129, 130].

CAP has shown positive effects in different models of atopic dermatitis (AD) in mice. In a mouse model induced by 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB), CAP reduced skin cell apoptosis and alleviated skin inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and oxidative stress, and this anti-inflammatory effect was mediated by MANF expression [134]. In a mouse model induced by house dust mite extract (DFE), local treatment with CAP reduced the severity of dermatitis, transepidermal water loss (TEWL), and serum IgE levels [132]. CAP inhibited the epidermal thickness and the recruitment of mast cells and eosinophils in the AD mouse model induced by house dust mite (HDM) while reducing the expression of AD-related cytokines and chemokines [135]. CAP inhibited the release of inflammatory factors, the number of mast cells and eosinophils in the AD mouse model induced by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB), and significantly suppressed AD-related immune reactions compared to the use of 1% hydrocortisone ointment alone [136]. Clinical studies have also demonstrated the therapeutic potential of CAP for AD. In a clinical study involving 22 patients with mild-to-moderate AD, CAP improved AD skin lesions and itching. Microbiome analysis showed a significant reduction in the proportion of Staphylococcus aureus in the CAP treatment group [137].

Plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) has shown promising efficacy and safety in mouse models of vitiligo and active localized vitiligo patients. Skin biopsies showed that local treatment with PAH increased melanin distribution in depigmented lesions on the backs of mice reduced T-cell and dendritic cell infiltration, and decreased the release of inflammatory factors. CAP upregulated the expression of the transcription factor NRF2 and weakened nitric oxide synthase activity to enhance cell resistance to oxidative stress and excessive immune responses [181]. In a randomized controlled trial, CAP treatment partially and completely pigmented 80 and 20% of vitiligo lesions, respectively, with no excessive pigmentation or other adverse events during treatment and follow-up [181]. Table 3 delineates the various applications of cold atmospheric plasma in dermatology.

Table 3.

Cold atmospheric plasma applications in dermatology

| Application | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. CAP’s suppressive effect on microbial skin infection | With advantages over traditional antibiotics, CAP effectively inhibits infections on diverse surfaces. Studies demonstrate its safety and efficacy in sterilizing bacteria, disrupting biofilms, and reducing bacterial loads in diabetic foot ulcers. CAP’s broad-spectrum mechanism challenges bacterial resistance, making it promising for combating infectious diseases |

| 1.1 Effects of CAP on bacteria | Research confirms CAP’s efficacy against bacteria and biofilms, including common strains like Escherichia coli. Plasma-activated liquids, especially plasma-activated water (PAW), show promise by generating reactive species, disrupting biofilms, and modulating inflammation, offering a novel approach to address biofilm-related infections |

| 1.2 Effects of CAP on fungi | CAP has shown efficacy in treating nail fungal infections, inhibiting the growth of causative agents in pathogen models and clinical trials. A pilot study and a cohort of 40 patients demonstrated overall clinical cure rates exceeding 70%, establishing atmospheric pressure cold plasma as a safe and promising alternative therapy for skin fungal infections |

| 1.3 Effects of CAP on viruses and parasites | CAP shows potential antiviral effects, with positive outcomes reported in treating viral warts and lower but measurable results on HSV-1. It also demonstrates efficacy against parasites like Demodex mites and head lice, suggesting its possible use in dermatology pending further exploration and studies |

| 2. CAP promotes tissue proliferation and wound healing | CAP is effective in wound healing by promoting antiseptic properties, pro-angiogenic effects, tissue proliferation, and the expression of growth factors and chemokines. CAP accelerates wound healing by reducing bacterial load, stimulating cell proliferation, and inducing gene expression, offering a promising approach for improved wound treatment, including the use of plasma-activated liquids like plasma-activated water (PAW) and plasma-activated hydrogel (PAH) |

| 3. CAP for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases | CAP regulates the formation of stratum corneum cells by modulating the redox balance and activating the NRF2 pathway. Clinical studies show that CAP can alleviate skin inflammation, restore normal cell differentiation, and may represent a novel therapeutic approach for inflammatory skin disorders by regulating cell viability, proliferation, migration, and inflammatory responses |

| 3.1 Psoriasis | CAP demonstrated therapeutic effects on psoriasis in cellular and animal studies, reducing epidermal hyperplasia and improving symptoms by inducing apoptosis and regulating reactive species. Atmospheric pressure cold plasma patches also showed promise in treating psoriatic skin lesions by mitigating electric field effects and inducing calcium ion channel opening in keratinocytes |

| 3.2 Atopic dermatitis | CAP has shown positive effects in alleviating atopic dermatitis (AD) in mouse models by reducing skin inflammation, oxidative stress, and dermatitis severity. Clinical studies on AD patients revealed improvements in skin lesions, itching, and a reduction in Staphylococcus aureus proportion after plasma treatment |