Abstract

Background

Hospital resilience has been well recognized among healthcare managers and providers as disruption of hospital services that threatens their business environment. However, the shocks identified in the recent hospital resilience concept are mainly related to disaster situations. This study aims to identify potential shocks that hospitals face during disruptions in Indonesia.

Method

This qualitative study was conducted in Makassar, Indonesia in August-November 2022. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with hospital managers and resilience experts using a semi-structured interview guide. 20 key informants were interviewed and data were analyzed by thematic analysis.

Results

The study identified seven shocks to hospitals during the disruption era: policy, politics, economics, hospital management shifting paradigms, market and consumer behavior changes, disasters, and conflicts. It also identified barriers to making hospitals resilient, such as inappropriate organizational culture, weak cooperation across sectors, the traditional approach of hospital management, inadequate managerial and leadership skills, human resources inadequacies, a lack of business mindset and resistance to change.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of hospital shocks during disruptions. This may serve as a guide to redesigning the instruments and capabilities needed for a resilient hospital.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-11385-2.

Keywords: Shocks, Resilience, Hospitals, Disruptions, Healthcare

Background

Research on hospital resilience and its potential for disaster risk reduction and enhancing community resilience has increased in the last decades [1]. Traditionally, the notion of hospital resilience has been used mainly as a theory in disaster contexts and as Hospital Disaster Resilience (HDR). This involved, to some extent, the ability of hospitals to withstand, absorb, and respond to disasters while maintaining critical functions and restoring hospital functions to their original state or adapting to new conditions [2]. However, the concept of hospital resilience, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), consists of 3 aspects of resilience: shocks, capacity to deal with disturbances, and levels of resilience. Shocks are conditions that disrupt the service provision system, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and other health emergencies, such as Ebola [3, 4]. Other examples include the Zika virus and hurricane Matthew in 2016 [5], the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 [6], and political conflicts that result in mass migration, such as the war in Syria [7]. The severity of the shock to the health system can vary from one situation to another. Preparation in the pre-shock phase determines how vulnerable the system is to the disturbance [8]. Capacities to deal with disturbance would illustrate the system’s adaptability to deal with and manage the shocks. This resilience capacity describes the overall goal of a system to continue to function optimally in the face of pressures to achieve its goals [9]. During a disaster, an individual, community, or organization is generally pushed from one state of relative stability or balance to another extreme [10]. The extent to which they can cope with the change is a measure of their adaptive capacity [11, 12]. This capacity varies and produces different resilience outcomes. Some organizations collapse while others recover, either becoming worse than before, or improving, while some even transform [13].

According to the WHO’s concept of resilience, we understand that when there is awareness, the shocks will make us less vulnerable when facing them. McManus highlighted the fact that resilience requires situational awareness so that organizations can identify and manage the roots of vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities in complex and dynamic environments [14]. Resilience is not a static state of the organization. Organizational resilience and the challenge it face change over time. In a period of disruption, hospitals worldwide face dynamic and challenging environmental variations in an era of enormous innovation and change that impact all existing systems, orders, and landscapes in different ways [15, 16]. This is also immense in the era of disruption, where many new things that had never been thought of before in conventional situations could spring up. Hospitals are faced with various challenges in digitizing health services [17], market dynamics [16], health-seeking behavior [18], as well as unstable economic conditions that affect hospital business processes [16].

More recently, the concept of hospital resilience tends to focus more on disaster-related shocks [8, 19–25]. In Indonesia, the resilience model was introduced in hospital accreditation standards, focusing on how to make hospitals safe during disaster situations by implementing the Hospital Safety Index (HSI) [26]. However, this new concept is not compatible with the development of the hospital business environment. There is little research that explored the shocks faced by hospitals in the era of disruption to make them resilient. This study, the first of its kind in Indonesia, attempts to develop a conceptual model of hospital resilience in Indonesia’s disruption era. The study aims to identify potential current and future disruptions faced by hospitals in the context of hospitals in Indonesia, which could serve as guide to redesign the instruments and capabilities needed for a resilient hospital.

Health resilience framework

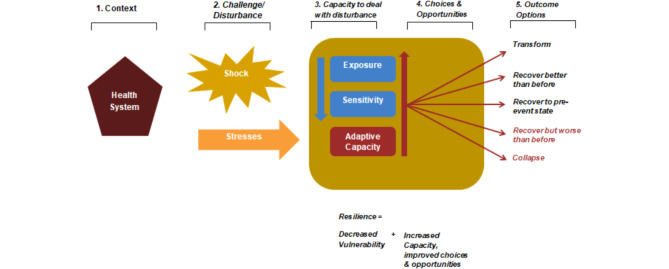

Several frameworks for measuring resilience levels have been developed, one of which is the concept of health service system resilience developed by the WHO. The concept of health system resilience encompasses the challenges or shocks faced, the capacity to deal with disturbance, and the output of resilience levels [27].

The term Resilience describes the overarching goal of a system to continue functioning as effectively as possible in the face of pressures to achieve its objectives, where resilience is a function of the system’s vulnerability and adaptability. Based on the figure, the resilience of health services is faced with challenges or disruptions, which can be in the form of shock or stress. The term “shock” describes an event that suddenly occurs or has a rapid onset, causing a disruption with a high impact on the health system, such as an outbreak of the infectious disease Ebola [28], hurricanes [5], floods, and tsunamis [28]. “Stress” describes a slow onset, indicating longer disturbances over an extended period, such as epidemics, climate change [29], the global financial crisis in 2008 [6] and political conflicts resulting in mass migration, such as the war in Syria [7].

Apart from challenges or disturbances, when responding to the challenges faced, the system will develop the capacity to deal with disturbances. The severity of a shock is determined by the level of exposure to the disturbance and the sensitivity of the health system, which also affects adaptive abilities [8]. In the context of disasters, vulnerability is generally described as the exposure of an organization or individual to a disaster, resulting in a certain level of loss, combined with the ability to survive, prepare for, and recover from the same event. This describes the relative level of risk and vulnerability [30]. For example, vulnerability is often determined by characteristics such as poverty. However, when analyzing vulnerability, we need to recognize that not everyone suffers in the same way in response to the same event [31, 32]. Adaptive capacity is defined as the ability of a system to respond to changes in its external environment and to recover from damage to internal structures by changing strategies, operations, management systems, governance structures, and decision support capabilities to withstand disruptions [33].

Based on the shocks and the capacity to deal with disturbances, each system will demonstrate different resilience capabilities according to its level of vulnerability and adaptive capacity. Some systems may transform and recover better than before or return to their pre-event state. However, if a system does not have sufficient adaptive capabilities, the resilience outcome may result in recovery that is worse than before, or even in the system’s collapse.

Methods

This research is the first stage of the Hospital Resilience Conceptual Model research. The study of the Hospital Resilience Conceptual Model consisted of three stages. The first stage of the study was to explore the disruptions faced by the hospitals. The second stages involved exploring the hospitals’ capacities to address the disruptions identified in the first stage. The final stages were to verify the model of hospital resilience indicators. These stages were developed by adopting the frameworks of health system resilience by the WHO but in the context of hospital system as healthcare facilities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The Shocks and Barriers of Hospital Resilience during the Disruption Era adopted the Resilience Framework of WHO

This qualitative research was conducted in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia between August-November 2022. Respondents were selected key informants who were knowledgeable and had expertise in hospital resilience, using purposive sampling. Overall, 27 respondents were selected, including people employed as hospital policymakers, hospital managers, or resilience experts with a minimum of 10 years of working experience. They were contacted by phone to seek their interest and availability as well their preference of whether to be interviewed virtually (online) or face-to-face. In the end, 20 participants confirmed their willingness to participate in this research. The characteristic of key informants are shown in our previous publication [27].

This first stage of study conducted semi-structured interviews to explore shocks in disruption era categorized as technological disruption, social changes, and the economy. The categories used were based on the work of Shaw and Chisholm that identified disruption in health care [16]. The interview guide used in this study was based on interview questions that are provided as a supplementary file (Supplementary File 1).The interviews, which were audio recorded, were held in Bahasa and lasted between 30 and 60 min. Codes (1.1 to 1.20) were used to hide respondents’ identities. All recording data recorded were manually transcribed verbatim and listed into the interview tables for data cleaning.

Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. The interview transcriptions were coded based on pre-defined categories and new categories outside the pre-defined categories were added as necessary. The coding process was conducted by two people using an interview matrix in Microsoft Excel. The interview table consisted of information such as participant characteristics, participants’ responses and data reduction, and a summary of each theme. The category results were checked again by other researchers using the interview matrix. to ensure the validity of data interpretation. The result of the interview matrix was translated into English by NS. The presentation of qualitative data used direct quotes from respondents, narration, and pictorials [34]. The results of the interviews were illustrated by adopting the WHO’s (2014) framework of the resilience [35]. All procedures in this study were approved by an ethical committee from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Hasanuddin University with an approval number 9860/UN4.14.1/TP.01.02/2022.

Results

Based on the in-depth interviews with key respondents, 7 external shocks were identified as hospital disruptions in Indonesia. These external disruptions include policies, changes in the paradigm of hospital management, changes in markets and consumer behavior, technological advances, disasters, the politicization of health services, the economy, and conflicts (war). In addition, the results of the interviews also identified the hospital’s barriers that impact the ability of hospitals to become resilient. The shocks and barriers that the hospitals face are illustrated in Fig. 1.

External disruptions

Policy

Most respondents highlighted policy as one of the shocks in disruption era. The policy aspect is viewed from various perspectives by the informants. Some informants consider policy based on recently established content, and the constantly changing nature of policies. Policy disruption mentioned by the respondents includes hospital policy changes initiated during the Covid-19 pandemic, such as health service digitization, which became mandatory to using electronic medical records and telemedicine. Changes in the use of domestic medical devices pharmaceutical products and implementing a standard class of inpatients unit namely Kelas Rawat Inap Standar (KRIS). As is known, (Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial) BPJS or Social Security Administration for Health currently implements an inpatient class system divided into classes 1,2, and 3. This division categorizes participants based on the amount of contribution and the quality of the treatment room to which they are entitled. Meanwhile, in the KRIS system, all participants are entitled to the same tratment room with standards regulated by the government. This as one key informant stated:

“Policies, for example, one day the government will enforce a standard class of inpatient unit (KRIS). When implementing this policy, the hospital will redesign the master plan, make infrastructure adjustments to carry out KRIS, and implement KRIS” (I.13).

Some respondents also mentioned that hospital policies that were established long ago are still disrupting hospital operations such as Social Security Administration for Health or called Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial (BPJS) for health payment rates policies for hospitals that have not changed in the last 6 years, BPJS for Health is a legal entity established to administer the health insurance program in Indonesia. This point as illustrated below:

“We know exactly that by working with BPJS (health) it means that approximately 80–90% are BPJS patients. We know that the BPJS (health) regulation is indeed the obstacle, the current rates used since 6 years ago, are no longer relevant to the current condition of hospitals. The course of the disease, even for this catastrophe, which has a large portion, costs quite a lot, and this is also increasing, so the cost becomes large. So it’s true that the funding from BPJS (health) seems to have needed to be revised to suit the current conditions and the current disease.”(I.6).

The last issue related to policy aspects mentioned by informants is the constantly changing government policies. Based on the interview results, three informants indicated that the frequently changing hospital policies are one of the disruptions, as illustrated by the following interview quote:

“The main issue is BPJS Health, as it is an independent national institution. Due to numerous economic and political issues, its policies often change. In the past, we frequently received feedback from employees about the constantly changing and inconsistent management. We have to follow and adapt to external regulations”(I.10).

Changes in the hospital management paradigm

Another shock that was raised by the majority of respondents was regarding the shifting of the hospital management paradigm. Several respondents reported that in the last decades, hospital industrialization has faced a major shift in terms of changing the financing system in hospitals from a fee service to the INA-CBGs system, BPJS as a single-payer for national health insurance, as highlighted below by one of the respondents:

“shifting, service transformation, back several years ago, the hospital used the concept of provider base. who was the provider? doctor, hospital. He determined everything, how much it cost, etc. Since the implementation of the national health insurance system through BPJS, it started to go in there, eventually shifting to cost-based, all costs were calculated; it was like a tsunami for doctors who were used to setting their rates. But now, people can seek health treatment anywhere at the same price. this is an extraordinary disruption” (I.15).

Some respondents also predicted there would be a big shift in hospital care if the mono-loyalty of medical staff is implemented and linked to the application of the Health Facilities Information System (H.F.I.S) BPJS as explained below:

Doctors can practice in 3 places, but it will no longer be possible in the future because there will be mono-loyalty. This is a challenge for hospitals, especially private hospitals, because they usually use specialist doctors from government hospitals (I.6).

Market changes and consumer behaviour

The changes in the market and consumer behavior were also mentioned as factors leading to hospital disruption. The changes in health service delivery using online consultation and online delivery have influenced patient behavior:

And then the demand for drug delivery and teleconsultation has recently increased, now they are probably used to shopping online with gadgets, so they also hope to shop for health from home, so we as hospital practitioners feel right, there are changes and demands like that(I.16).

Besides that, the community limits face-to-face meetings and prefers not to linger in queues.

From a social aspect, especially regarding patient behavior, patients don’t want to spend a long time in the hospital because they are afraid. this is a challenge (I.16).

Advances in technology

Another shock that some respondents mentioned is technological advancement, as technology is seen as one of the disruptions that has changed the hospital business, such as the rapid development of medical device technology, the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the use of robots in health services as illustrated below:

Yes, of course, we know that in the context of this disruption, of course, many (of) our jobs will be taken over by digital, for example, or let’s say one thing might also be robotics, for example, that’s what happened (I.13).

The use of AI was also seen as one of disruptions as stated below:

“In the context of Indonesia, Artificial Intelligence is still not widely used here. In our hospital, we are offered a software to read X-ray results using AI, so it no longer relies solely on the radiologist, but it is indeed not widely used in Indonesia yet. But this issue challenges (to) our radiologist“(I.16).

The use of robots in health services was also mentioned as one of disruption as illustrated below:

“Someday in the future, like our surgeries with laparoscopy which can be robotic, the surgeries will be done by robots instead of humans. Of course, our hospitals, if we compare them to abroad, our robotic technology is still not there yet. But someday, if it’s available, it will become threatened because people’s mindset may change—they will definitely choose the certainty and sophistication of robots”(I.4).

Politicizations of health services

Disruption due to politics includes political influence in determining strategic positions in hospitals, especially in government hospitals. In some hospitals, managers who are appointed do not have the required qualifications and experience. In addition, respondents identified a concern about the fact hospital policies keep changing when the leadership changes, which impact on the continuity of some aspects of hospital functions as stated by one respondent.:

must be freed from politics, from political attachments. Because normally, health is always used as a political commodity ahead of elections, the election of the president, regional head, or council members. But once the election is over, that’s it; let it go again. when it comes to health, it must be based on the plan. Changing the regional head, changing the president, the policy change, something we have planned is suddenly cut short in the middle of implementation (I.7).

Disaster

The other important point mentioned repeatedly is a ‘disaster’. Some key informants explained the condition of Indonesia, which is located in a disaster-prone area. Disasters such as earthquakes, floods and landslides are very common, hence causing disruptions to the normal functioning of hospitals.

“Then about disruption, specifically for Indonesia. In a year there are around 3992 disasters that happen. It means that every day we have 8 disasters happen, and then maybe around 56 times per week, per month, multiply it may be up to 300. What does that mean, it means that disaster is a necessity in Indonesia, and the trend is increasing”. (I.19)

Most of the respondents mentioned that hospitals should be aware and be prepared to face global warming that causes climate change. Likewise, some key respondents emphasized the need for hospitals to be prepared for non-natural disasters such as pandemics that occurred a few years ago and will continue to do so.

“We were not ready, so far, there hasn’t been a pandemic since we were in Europe before, right? We were unaware, so we didn’t prepare the infection room based on needs. As soon as it explodes, unpreparedness occurs”(I.17).

Economy and conflict

Finally, some respondents also mentioned the economy, which affects the ability to pay because of high inflation and rising costs, as well as conflicts (wars), e.g. the war between Russia and Ukraine, which have devastating impacts because of the shocks and disruptions they cause.

“While our hospital services have not returned to normal like before the pandemic, not completely normal yet. Recently, operational costs are still the same, maybe even higher with inflation, all taxes have increased, and other costs have also increased. Many things in our economy, people’s Ability to Pay has fallen” (I.9).

Barriers to hospital resilience

Inappropriate organizational culture

Several respondents also explained that several things make it difficult for hospitals. They mentioned barriers such as the organizational capacities of hospitals, which include poor organizational culture as illustrated below:

“Because firstly, there is always an organizational culture, the hospitals belongs to the government, the government buy the health equipment’s, we never feel that we belong, so we don’t want to struggle to support the hospital. But how can you support yourself if you don’t have a good business plan and activity? In the end, you have to wait for the patients to come, your patients are more than 80% are only BPJS patients, while at X hospital, they have 75–80% non-BPJS.” (I.15).

Weak cooperation cross-sector

Another barrier stated by respondents is weak cooperation cross-sector. For example, public hospitals as institutions under the Ministry of health when facing the COVID-19 pandemic, had difficulty in providing oxygen gas through Ministry of Health. Hospitals must have cross-ministerial cooperation so they can obtain oxygen gas quickly as stated by one respondent:

No support for health service from another ministry. Cooperation. Why? For example, we hear about the issue of oxygen scarcity during a pandemic. Oxygen is not the Ministry of Health authority; oxygen is the Ministry of Industry because oxygen is an industrial gas, but one type is medical oxygen, and so far, the Ministry of Health did not expect that the demands would be over capacity (I.17).

The traditional approach of hospital management

Most of the respondents also identified the application and practice of traditional hospital management as important barriers. Hospital still apply the concept which prioritizes social functions without paying attention to business continuity, marketing management, cost effectiveness, cost containment and patient-centered services as illustrated by the following quotes:

”hospital in Indonesia is not like those abroad, having a customer first and marketing value”(I.12)

“…University hospitals and government hospitals’ monthly revenue with very big resources is only 4–5 billion. Private hospital with a similar amount of bed, and human resources has bigger revenue, they gain 40 billion monthly. How come? The hospital board committee should identify the gap. Private hospital has a good brand image, why do government hospital not build branding image as well?”(I.15).

Inadequate managerial skills of leadership and Human resources (HR) capabilities

Another important barrier mentioned is inadequate managerial skills of leadership and HR capabilities.Hospital leaders especially in middle management are often considered to lack good leadership competence due to they were chosen not based on their qualifications for the positions as illustrated below:

…….the inability of hospital managers to understand the concept of management (I.14)

So, if we look at it now, from the position of director to the middle manager, especially at the Regional Hospital, not all of them are chosen by considering their job competency (I.5).

Lack of business mindset in managing hospitals

In addition, a lack of business mindset in managing hospitals was also mentioned as barrier to be resilient hospital. as explained by one respondent.

Hospital in Indonesia serves so many patients that they do not target the amount of patients. Abroad, hospitals are shown as an industry. They create medical tourism hospitals and become devices. In Indonesia, hospitals are not shown as an industry. (I.12)

Resistance to change

Finally, resistance to change is also one of the barriers mentioned by respondents. The respondent gave an example of when the human resources were resistant to digitalization as illustrated below:

“.In the past, everything was done by man; now, they will use technology a lot because it will make the job easier. One of the obstacles that I experienced during my time as the main director of the hospital was implementing electronic medical records. The doctors have to input data, and they think it takes time for them, rather than handwriting” (I.13).

Discussion

The study aimed to identify potential shocks that hospitals may face during disruption era in Indonesia. The shocks are identified to be external or internal to a hospital system. Our research findings highlighted the views of key informants who believe that frequent changes or a policy disrupts the current situation in most hospitals. Hospitals must be able to anticipate changes in hospital policies. Based on the interview results, policy disruptions are often viewed in terms of the content or substance of the policies themselves The recent development of regulations forces hospitals to adjust, such as hospital classification policies, a standard class for inpatient units, accreditation policies, and digitalization policies [36]. For example, a standard inpatient class policy obligates the standard of an inpatient room in terms of area, size, and facilities [37], as well as digitization policies for the hospital information system with the BPJS system.

Furthermore, the policy process itself is also a concern for informants, with some indicating that current policy implementation is suboptimal and needs review, such as the BPJS service tariff policy. One of the disruptions related to BPJS policy mentioned is the lack of capitation rate increased since 2016. However, in 2023, the Ministry of Health released a policy regarding the Adjustment of Tariffs for the National Health Insurance Program, as stipulated in Minister of Health Regulation Number 3 of 2023 concerning Standard Tariffs for Health Services in the Implementation of Health Insurance. This standard tariff replaces the health service tariff standard in hospitals, which had not changed since 2016. The tariff changes in the policy include changes in the coverage of services covered and the top-up tariff policy for certain health services.

Policy changes are seen as a threat because of their possible implications. Implementing policies in hospitals determines the cooperation as the result of a hospital contract with the single national health bridging insurance (BPJS), the largest target market of hospitals in Indonesia. In addition, the situation became more complex when the Ministry of Health initiated a health system transformation following the Covid-19 pandemic. This policy influences the operational policies of health facilities at almost all levels of the health service provision [38]. With the constantly changing policies, hospitals are faced with increasing complexity, especially with the continuously updated national health insurance system regulations aimed at achieving the best quality of care for patients [39]. Policy changes require efforts to transform inputs and organizational structures, which ultimately will impact the productivity of hospitals [40]. This is in line with Blank and Eggink’s (2013) study, which has shown the influence of hospital policy changes on the health workforce, material supplies, and capital inputs within the organization [41].

Another identified disruption was the change in the paradigm of hospital management. Since 2014, the Indonesian government has implemented Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [42]. The implementation of UHC is a disruption for hospitals in Indonesia, especially related to changing the payment mechanism for health service providers from a fee-for-service system to an Indonesia Case-Based Groups (INA-CBG) system [43]. Hospitals, which initially played a major role in determining prices, have completely changed based on the INA-CBGs system. Hospital income changes, and hospital managers begin to estimate the resources needed to treat the disease and predict the required medical expenses [44]. The hospital’s focus has changed to efficiency gains and cost containment in providing services. Besides that, another shifting paradigm also raised in this study is the issue of mono doctor loyalty. This involves limiting health facilities of doctor work practice from 3 health facilities to only one health facility. However, the challenge of this issue is that the current distribution of doctors is not well distributed, and even the number is still lacking in certain areas [45].

Other disruptions that are also reported in findings of other studies are market changes and consumer behavior [46, 47], technology advances [40, 47–53], and the economy [16, 54, 55]. Changes in the health service market are shown as one of the shocks due to changes in how people seek treatment. For example, people prefer to access health service information using social media [56], consult a doctor using video consultations [57], patient expectations to use hospital services at home, and increased concerns for safety in the hospital setting [58]. These findings are similar to a study in India about the experiences of 715 patients during the Covid-19 pandemic, which revealed that 31.7% of patients continued consultations using telemedicine after the Covid-19 pandemic [59]. Another study in Indonesia showed 44% of respondents used Telemedicine [60] and Australia also showed that more than 60% of patients like to communicate using technology [18].

Health service market change was also triggered by changes in health technology which were developing rapidly. The technology that significantly changes the way entire industries operate, becomes disruptive and appears to be a primary source of disruption [61]. Most changes are due to the evolving health technology, with the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating the digitization of the business environment. The increased use of digital tools blurs the lines between work, lifestyle, social interaction, and domains such as mobility, health, and finance [62]. The current rapid development of medical device technology is driven by innovation, with continuous efforts to improve efficiency, productivity, and trends towards smarter and smaller devices [63].

Various innovations in the health sector, such as biomedical engineering, robotics, artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and the cost of data, have implications for exponential change, accelerating the disruption phase [26, 64]. Changes due to this technology, as reported by Viknesh et al. (2020), are called disruption innovations. From a health providers perspective, technology disruption could be the change of technology with one that is similar to or better in quality but has a great deal lower cost and uses data-based technology or delivery methods, and exhibits an exponential increase or improvement in size, speed, quality of care [26]. This disruption causes market changes due to the new business model and many customers adopting the technology [26, 65]. In such conditions, medical and hospital administrative staff are required to be tech-savvy. However the challenges of digitalizing health services in hospitals in Indonesia relate to various factors, including hospitals’ lack of interest in digital investment, difficulty in national-scale data integration, traditional organizational culture and bureaucracy, lack of clarity in laws for personal data protection, and outdated and poorly integrated technology [66].

In this study, we have also identified shocks developed in conventional resilience concepts, namely disasters. As in previous resilience studies, earthquakes, climate change, floods, landslides, and pandemics are the shocks. Hospital resilience capability in dealing with disruption due to disasters is a necessity. Geographical and geological structure makes Indonesia one of the disaster-prone countries [67]. In 2022, the number of natural disasters that have occurred is 3,531 times with a moderate to mild impact [68]. Hospitals have a very important role in saving lives and reducing the suffering of injured people during and after disasters. Disasters create spikes in demand that can quickly overwhelm the capacity of healthcare service providers. Hospitals are expected to create a safe environment for patients and staff and provide health services for disaster victims [69].

Another disruption issue that was also the concern of the informants was the politicization of health services. The existence of political intervention in hospital management, such as determining strategic positions in government hospitals, without considering the person’s qualifications. Apart from that, policy changes related to hospitals can change or even be stopped when there is a change in position. In the political context, hospital construction is sometimes used as a political promise without considering whether the community needs hospitals and whether resources are available to build them. Hospital development policies certainly involve allocating significant budgets for buildings, medical equipment, and Human Resources (HR) investments. The disruption from politicizing healthcare services affects resource management in hospitals because government technical interventions are not based on standards.

Finally, this research attempts to develop a hospital resilience framework in the era of disruption by identifying the shocks it faces. We modified the framework developed by WHO (2014) by adding the internal challenges faced by hospitals, which also affect the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of the hospital to become resilient. This study found several obstacles to enhancing hospitals’ resilience. This is not categorized as a disruption because all the challenges originate within the organization. Sandrun (2014) refers to this obstacle as operational risk, which concerns poor capacity management, Supply chain issues, Employee issues, and Operating controls. [70]. In facing this risk, hospitals must identify what can be done to reduce these organizational weaknesses. Some of these internal factors are even domains that are widely discussed in the resilience capabilities needed to become a resilient hospital, for example, governance [71], human resources [71, 72], organizational culture [71, 73, 74], and leadership [71, 75–78].

The limitation in this study that need to be mentioned is all the informants are from Indonesia. This means that the views on disruptions are specific to how hospitals operate and do business in Indonesia. Because of this, it is hard to apply our findings to hospitals in other countries, especially those in developed regions where the rules, healthcare systems, and market conditions are different. Additionally, we could get a better understanding of disruptions in the hospital industry if we included informants from different countries. Having participants from various backgrounds would give us a wider range of insights and help us see the similarities and differences in how disruptions are dealt with around the world. Future research should try to include more diverse informants from different countries. This would help us better compare strategies and policies across different healthcare systems and come up with findings that apply more broadly.

Conclusion

We have identified several shocks that hospitals potentially face in the era of disruption. The results of this study can enrich the framework for the concept of hospital resilience, which has so far focused on the concept of shocks related to disasters. In this study, the shocks identified were not only related to disasters, but several challenges faced by hospitals in their strategic business environment from policies, to paradigm shifts in hospital management concepts, economics, politics, market changes, and technological developments. Shocks in the era of disruption are very dynamic so hospitals need to prepare themselves to be more flexible and agile. In addition, this research also identifies hospital barriers to increasing its adaptive capacity to become a resilient hospital that focuses on the internal challenges hospitals face. Future research needs to be carried out to explore the capabilities that hospitals face in the context of shock identified in this study. This research can also be input for the Indonesian government to enrich the concept of hospital resilience, which is currently used in hospital accreditation standards that still use the Hospital Safety Index (HSI) instrument.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World Health Organization

- HDR

Hospital Disaster Resilience

- UHC

Universal Health Coverage

- INA-CBGs

Indonesian Case-Based Groups

- HSI

Hospital Safety Index (HIS)

- KRIS

Kelas Rawat Inap Standar

Author contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualizing the research concept. The original draft was written by NS. MO contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscripts. SAP and AID contributed to data collection. I, YT, ML, DA contributed to the research methodology. NS conducted data analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education Indonesia for research funding Grant 2022.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Hospital Management Department, Public Health Faculty of Hasanuddin University upon reasonable request. Requests for access to these data should be directed to corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Review Committee of the Public Health Faculty, Hasanuddin University (Approval No. 9860/UN4.14.1/TP.01.02/2022) approved ethics approval and consent to participate in this study. All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. All subjects’ informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Witter S, Hunter B. Resilience of health systems during and after crises – what does it mean and how can it be enhanced? 2017;1–4. https://rebuildconsortium.com/media/1535/rebuild_briefing_1_june_17_resilience.pdf

- 2.Fallah-Aliabadi S, Ostadtaghizadeh A, Ardalan A, Fatemi F, Khazai B, Mirjalili MR. Towards developing a model for the evaluation of hospital disaster resilience: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Strengthening Health Resilience to Climate Change. 2014;24.

- 4.Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet [Internet]. 2015;385(9980):1910–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Berry P, Ogawa-Onishi Y, McVey A. The vulnerability of threatened species: adaptive capability and adaptation opportunity. Biology (Basel). 2013;2(3):872–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas S, Keegan C, Barry S. Richard Layte2 MJ and CN. A framework for assessing health system resilience in an economic crisis: Ireland as a test case. Health Policy Plan. 2013;8(2):150–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammar W, Kdouh O, Hammoud R, Hamadeh R, Harb H, Ammar Z et al. Health system resilience: Lebanon and the Syrian refugee crisis. J Glob Health. 2016;6(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Blanchet K, Nam SL, Ramalingam B, Pozo-Martin F. Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: Towards a new conceptual framework. Int J Heal Policy Manag [Internet]. 2017;6(8):431–5. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Roser-Renouf C, Maibach EW, Li J. Adapting to the changing climate: An Assessment of Local Health Department Preparations for Climate Change-Related Health threats, 2008–2012. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuzzo JB, Meyer D, Snyder M, Ravi SJ, Lapascu A, Souleles J, et al. What makes health systems resilient against infectious disease outbreaks and natural hazards? Results from a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vugrin ED, Verzi SJ, Finley PD, Turnquist MA, Griffin AR, Ricci KA, et al. Modeling hospitals’ adaptive capacity during a loss of infrastructure services. J Healthc Eng. 2015;6(1):85–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen KJ, Friel S, Ebi K, Butler CD, Miller F, McMichael AJ. Governing for a healthy population: towards an understanding of how decision-making will determine our global health in a changing climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(1):55–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahrens CW, James EA. Regional Genetic structure and Environmental Variables Influence our Conservation Approach for feather heads (Ptilotus macrocephalus). J Hered. 2016;107(3):238–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus S, Seville E, Vargo J, Brunsdon D. Facilitated process for improving Organizational Resilience. Nat Hazards Rev. 2008;9(2):81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaivo-oja JRL, Lauraeus IT. The VUCA approach as a solution concept to corporate foresight challenges and global technological disruption. Foresight. 2018;20(1):27–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw B, Chisholm O. Creeping through the Backdoor: disruption in Medicine and Health. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11(June):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rachinger M, Rauter R, Müller C, Vorraber W, Schirgi E. Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. J Manuf Technol Manag. 2019;30(8):1143–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander KE, Ogle T, Hoberg H, Linley L, Bradford N. Patient preferences for using technology in communication about symptoms post hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biddle L, Wahedi K, Bozorgmehr K. Health system resilience: a literature review of empirical research. Health Policy Plan. 2020;1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Nuzzo JB, Meyer D, Snyder M, Ravi SJ, Lapascu A, Souleles J, et al. What makes health systems resilient against infectious disease outbreaks and natural hazards? Results from a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iflaifel M, Lim RH, Ryan K, Crowley C. Resilient Health Care: a systematic review of conceptualisations, study methods and factors that develop resilience. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieny Mpaule, Evans DB, Kadandale S. Health-system resilience: reflections on the Ebola crisis in western Africa. 2014;149278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.The Infrastructure Security Partnership (TISP). Regional Resilience Disaster a Guide for developing an action plan 2011 edition. Alexandria: The Infrastructure Security Partnership; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coiera E. Jeffrey Braithwaite. Turbulence health systems: engineering a rapidly adaptive health system for times of crisis. BMJ Heal Care Inf. 2021;30(01):017–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EU Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment (HSPA). Assessing the resilience of health systems in Europe: an overview of the theory, current practice and strategies for improvement [Internet]. 2020. 88 p. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/systems_performance_assessment/docs/2020_resilience_en.pdf

- 26.Friebe M. Healthcare in need of innovation: exponential technology and biomedical entrepreneurship as solution providers (Keynote Paper). 2020;(March):28.

- 27.Sari N, Omar M, Pasinringi SA, Zulkifli A, Sidin AI. Developing hospital resilience domains in facing disruption era in Indonesia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2023;23(1):1–14. 10.1186/s12913-023-10416-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kruk M, Myers M, Varpilah S, Lancet BDT. 2015 undefined. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. thelancet.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 4]; https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-67361560755-3/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hanefeld J, Mayhew S, Legido-Quigley H, Martineau F, Karanikolos M, Blanchet K, et al. Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health systems shocks. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(3):355–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEntire DA. Triggering agents, vulnerabilities and disaster reduction: towards a holistic paradigm. Disaster Prev Manag Int J. 2001;10(3):189–96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidaranlu E, Khankeh H, Ebadi A, Ardalan A. An Evaluation of the Non-Structural Vulnerabilities of Hospitals Involved in the 2012 East Azerbaijan Earthquake. Trauma Mon [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Nov 19];21(2):28590. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/197b/8850380535ed491c0869bbbd830c38ea0645.pdf

- 32.Berry P, Enright PM, Shumake-Guillemot J, Villalobos Prats E, Campbell-Lendrum D. Assessing Health vulnerabilities and Adaptation to Climate Change: a review of International Progress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Dalziell EP, Mcmanus ST. Resilience, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity: implications for system performance. Int Forum Eng Decis Mak. 2004;(January):17.

- 34.Boog B. Qualitative research practice. J Soc Interv Theory Pract. 2005;14(2):47. [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Operational framework for building climate resilient health systems [Internet]. World Health Organisation. Geneva. 2015. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081888

- 36.Law O, List NI. Future of Indonesian hospitals following recent regulatory developments. 2021;1–5.

- 37.Kurniawati G, Jaya C, Andikashwari S, Hendrartini Y, Dwi Ardyanto T, Iskandar K, et al. Kesiapan Penerapan Pelayanan Kelas Standar Rawat Inap Dan Persepsi Pemangku Kepentingan. J Jaminan Kesehat Nas. 2021;1(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harwiati EVI, Kep NS. Indonesian Health Syst. 2023;7–9.

- 39.Fadilla NM, Setyonugroho W. Sistem informasi manajemen rumah sakit dalam meningkatkan efisiensi: mini literature review. J Tek Inf Dan Sist Inf. 2021;8(1):357–74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meskó B, Drobni Z, Bényei É, Gergely B, Győrffy Z. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. mHealth. 2017;3:38–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blank JLT, Eggink E. The impact of policy on hospital productivity: a time series analysis of Dutch hospitals. Health Care Manag Sci. 2014;17(2):139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sisyani, Pribadi F, Urhmila M, Perbedaan Kualitas Pelayanan Pada Sistem Pembayaran INA-CBGs Dengan Fee For Service Di RS PKU Muhammadiyah Bantul. J Asos Dosen Muhammadiyah Magister Adm Rumah Sakit [Internet]. 2016;2(2):1–9. https://mars.umy.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/PAPER-SISYANI.pdf

- 43.Mahendradhata Y, Trisnantoro L, Listyadewi S, Soewondo P, MArthias T, Harimurti P, et al. Repub Indonesia Health Syst Rev Vol. 2017;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Happy A. The implementation of INA-CBGs System Impact on Financial Performance of Public Hospital, the Indonesia Case: a systematic review. KnE Life Sci. 2018;4(9):1. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sucahyo N. Pemerintah Wacanakan Pembatasan Praktik Dokter Hanya di Satu Tempat. Voaindonesia [Internet]. 2021;1–5. https://www.voaindonesia.com/a/pemerintah-wacanakan-pembatasan-praktik-dokter-hanya-di-satu-tempat/6291966.html

- 46.De Jong M, Van Dijk M. Disrupting beliefs: a new approach to business-model innovation. McKinsey Q. 2015;3:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halamka JD, Alterovitz G, Buchanan WJ, Cenaj T, Clauson KA, Dhillon V et al. Top 10 blockchain predictions for the (Near) Future of Healthcare. Blockchain Healthc Today. 2019;1–9.

- 48.Kickbusch I, Agrawal A, Jack A, Lee N, Horton R. Governing health futures 2030: growing up in a digital world—a joint The Lancet and Financial Times Commission. Lancet [Internet]. 2019;394(10206):1309. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32181-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Dearment A. AI in healthcare means grafting Star Trek onto The Flintstones - MedCity News. 2019;1–5. https://medcitynews.com/2019/09/ai-in-healthcare-means-grafting-star-trek-onto-the-flintstones/

- 50.Harrer S, Shah P, Antony B, Hu J. Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Trial Design. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(8):577–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coventry L, Branley D. Cybersecurity in healthcare: A narrative review of trends, threats and ways forward. Maturitas [Internet]. 2018;113(March):48–52. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Devi S. Disruptive Innovation and Challenges in Healthcare 3. 0 Evolving Global Scenario in Healthcare. 2021;1–8.

- 53.Franklin R. What is disruptive healthcare technology ? Disruptive innovation defined Disruptive technology in healthcare. 2021;1–6.

- 54.Amukele T. The economics of medical drones. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020;8(1):e22. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30494-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Elger C. 3 Reasons Why Health Care Providers are Facing Disruption [Internet]. 2019. https://ideawake.com/3-reasons-why-health-care-providers-are-facing-disruption/

- 56.Coates DR, Chin JM, Chung STL. Dangers and opportunities for social media in medicine Dr. Bone [Internet]. 2013;23(1):1–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3624763/pdf/nihms412728.pdf

- 57.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C. Video consultations for covid-19. BMJ [Internet]. 2020;368(March):1–2. 10.1136/bmj.m998 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Deloitte. Changing consumer preferences towards health care services: The impact of COVID-19. 2020; https://www2.deloitte.com/in/en/pages/life-sciences-and-healthcare/articles/covid-impact-lshc.html

- 59.Vaidheeswaran S, Karmugilan MK. Consumer buying Behaviour on Healthcare Products and Medical devices during Covid-19 pandemic Period-a new spotlight. Volatiles Essent Oils. 2021;8(5):9861–72. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malau K, TELEMEDICINE ACCEPTANCE, AND USAGE IN JAKARTA METROPOLITAN AREA. J Widya Med Jr. 2022;4:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 61.El Namaki MSS. Disruption in business environments: a Framework and Case evidence. Int J Manag Appl Res. 2018;5(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puttaiah M, Raverkar AK. All change: how COVID-19 is transforming consumer behaviour. 2020.

- 63.Thompson N. Medical technology trends for 2023: from sustainably to remote monitoring. 2023;1–7.

- 64.Batra N, Judah R, Betts D, MS ST. Forces Change Health. 2019;1–13.

- 65.Sounderajah V, Patel V, Varatharajan L, Harling L, Normahani P, Symons J, et al. Are disruptive innovations recognised in the healthcare literature? A systematic review. BMJ Innov. 2021;7(1):208–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kagama. Kagama Health Talks: Pentingnya Digitalisasi Rumah Sakit untuk Pelayanan Kesehatan. 2022.

- 67.Wibowo A, Surbakti I, Yunus R. Indonesia Disaster Database. Expert Gr Meet Improv Disaster Data to Build Resiliance Asia Pacific. 2013;3.

- 68.Statista. Number of natural disasters that have occurred in Indonesia in from 2012 to 2021. StatistaCom [Internet]. 2022;(2022):2020–3. https://www.statista.com/statistics/954348/indonesia-number-natural-disasters/#:~:text=In 2021%2 C there were around,occurring in Indonesia in 2021.

- 69.Arab MA, Khankeh HR, Mosadeghrad AM, Farrokhi M. Developing a hospital disaster risk management evaluation model. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.sandrun risk. Risk Management. What We Do. 2014. pp. 4–6.

- 71.Thomas S, Sagan A, Larkin J, Cylus J, Figueras J, Karanikolos M. Strengthening health systems resilience: key concepts and strategies. Strength Heal Syst Resil Key concepts Strateg; 2020. [PubMed]

- 72.Nunez E, Mitchell P. Tackling human and organisational factors: the human contribution. improve.bmj.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 19]; https://improve.bmj.com/sites/default/files/resources/tackling_human_and_organisational_factors.pdf

- 73.Lee AV, Vargo J, Seville E. Developing a Tool to measure and compare Organizations’ Resilience. Nat Hazards Rev. 2013;14(1):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Carvalho AO, Ribeiro I, Cirani CBS, Cintra RF. Organizational resilience: a comparative study between innovative and non-innovative companies based on the financial performance analysis. Int J Innov. 2016;4(1):58–69. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ree E, Ellis LA, Wiig S. Managers’ role in supporting resilience in healthcare: a proposed model of how managers contribute to a healthcare system’s overall resilience. Int J Heal Gov. 2021.

- 76.Sweya LN, Wilkinson S, Kassenga G, Mayunga J. Developing a tool to measure the organizational resilience of Tanzania’s water supply systems. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2020;39(2):6–19. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barasa E, 1 2 W, Cloete K, Gilson L. 4 5. From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Heal Policy Plan [Internet]. 2017;32:iii91–4. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=ppvovfts&NEWS=N&AN=00003845-201711003-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Punit Renjen. The essence of resilient leadership: business recovery from COVID-19. 2019. 43–6.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Hospital Management Department, Public Health Faculty of Hasanuddin University upon reasonable request. Requests for access to these data should be directed to corresponding author.