Abstract

Background

The study aimed to identify the optimal model for predicting rectal cancer liver metastasis (RCLM). This involved constructing various prediction models to aid clinicians in early diagnosis and precise decision-making.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 193 patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma were randomly divided into training set (n = 136) and validation set (n = 57) at a ratio of 7:3. The predictive performance of three models was internally validated by 10-fold cross-validation in the training set. Delineation of the tumor region of interest (ROI) was performed, followed by the extraction of radiomics features from the ROI. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression algorithm and multivariate Cox analysis were employed to reduce the dimensionality of radiomics features and identify significant features. Logistic regression was employed to construct three prediction models: clinical, radiomics, and combined models (radiomics + clinical). The predictive performance of each model was assessed and compared.

Results

KRAS mutation emerged as an independent predictor of liver metastasis, yielding an odds ratio (OR) of 8.296 (95%CI: 3.471–19.830; p < 0.001). 5 radiomics features will be used to construct radiomics model. The combined model was built by integrating radiomics model with clinical model. In both the training set (AUC:0.842, 95%CI: 0.778–0.907) and the validation set (AUC: 0.805; 95%CI: 0.692–0.918), the AUCs for the combined model surpassed those of the radiomics and clinical models.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that KRAS mutation stands as an independent predictor of RCLM. The radiomics features based on MR play a crucial role in the evaluation of RCLM. The combined model exhibits superior performance in the prediction of liver metastasis.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12880-024-01439-6.

Keywords: RC, KRAS mutation, Radiomics, RCLM, MRI

Introduction

Globally, rectal cancer (RC) ranks as the third most prevalent malignancy, characterized by a considerable mortality rate. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that over 1.9 million new cases of colorectal cancer, including the anus, occurred, resulting in 935,000 deaths [1].A significant proportion, exceeding 30%, of colorectal cancer (CRC) cases pertains to RC, primarily constituted by rectal adenocarcinoma (READ) [2]. Despite the diverse treatments available for RC, liver metastasis persists as a challenge, impacting both the overall survival (OS) rate and the prognosis. Reports indicate that 14.5% exhibit synchronous liver metastases at the time of initial diagnosis, and approximately one-third will subsequently develop metastases during the course of treatment or follow-up [3]. Patients with liver metastasis of CRC experience a median survival ranging from 5 to 20 months in the absence of treatment [4]. Therefore, accurately identifying and diagnosing rectal cancer liver metastasis (RCLM) early on is crucial for ensuring favorable long-term prognoses for patients.

The onset and progression of RC result from the combined action of numerous factors. Beyond the influence of external factors, the occurrence of RC is also intricately linked to various gene mutations. Research has demonstrated the involvement of genes such as APC, c-myc, RAS (KRAS and NRAS), p53, p16, DCC, MCC, DPC4, BRAF, and others in the carcinogenesis of intestinal mucosal epithelia. Notably, KRAS mutations represent an early event in CRC tumorigenesis [5], occurring in 35–45% of CRC patients [6–8]. Numerous previous studies have established the significance of the KRAS gene, closely associating it with RC. Mao et al. [9]observed that colorectal cancer liver metastasis (CRLM) with KRAS mutation exhibited higher maximum standard uptake value (SUV) and retention index (RI) in 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Additionally, SUV values were identified as predictors of KRAS mutation status in patients with CRLM. Modest et al. [10]and Souglakos et al. [11]demonstrated that the presence of KRAS mutation in patients with CRLM was linked to inferior progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. Several studies have indicated that KRAS mutation in patients with CRLM is associated with resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy [12].

With the development of computers, machine learning plays an important role in the field of medicine, it includes deep learning and classic handcrafted radiomics. Among them, deep learning has achieved excellent results in many fields, such as, the potential of the drug to cross the placenta, estimation of sex and age of electrocardiogram patients and so on [13, 14]. Radiomics is an emerging discipline that involves the analysis and extraction of numerous advanced and quantitative imaging features from computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US) images. A study using US images introduced a method that incorporates a modified Pyramid Scene Parsing module within optimized neural network backbones to achieve real-time segmentation while maintaining high accuracy [15]. Interventional radiologists extensively use CT scans for diagnosing and treating cancer and metastases in visceral organs. Because, CT imaging serves as an alternative to MRI for patients with metallic implants and pacemakers [16]. Imaging modalities like CT and MRI are employed in computer-aided diagnosis to assess disease conditions. Segmentation of CT/MRI images significantly enhances clinical decision support by playing a crucial role in current computer-aided diagnosis systems [17]. Imaging techniques can also be used for thermal ablation of malignant liver tumors. One study indicates that fusion imaging modalities, including CT/US, MRI/ US, and PET/CT, provide a promising approach to improve technical efficacy, safety margins, and local tumor progression rates for thermal ablation treatments [18]. The above indicates that imaging technology is widely used in the medical field. The quantitative analysis of radiomics characteristics can unveil the underlying pathophysiological information of each disease and acquire additional insights not attainable through conventional methods. Radiomics features, when combined with other information, can be correlated with clinical outcomes data and employed for evidence-based clinical decision support [19]. The combination of this specific subset of radiomics features with genomic data holds significant potential in aiding cancer patients in selecting diverse treatment modalities, evaluating treatment sensitivity (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), and predicting potential drug resistance [20]. The majority of prior radiomics studies have concentrated on assessing the KRAS mutation status in primary lesions of CRC [21, 22]. As far as we know, limited information is available concerning the radiomics features of liver metastasis lesions based on MR T2WI and their correlation with the genomic characteristics of KRAS and other clinical features.

In this study, we developed radiomics model, clinical model and combined model. The purpose of this study was to explore the efficacy of the three models in predicting liver metastasis in RC patients and select the optimal model to assist clinicians in categorizing and managing patients based on their varying probabilities of developing RCLM.

KRAS mutation stands as an independent predictor of liver metastasis in RC.

The radiomics features based on MR oblique axial T2WI play a crucial role in the evaluation of liver metastasis.

The combination of radiomics and KRAS exhibits superior performance in the prediction of liver metastasis.

Materials and methods

Patients

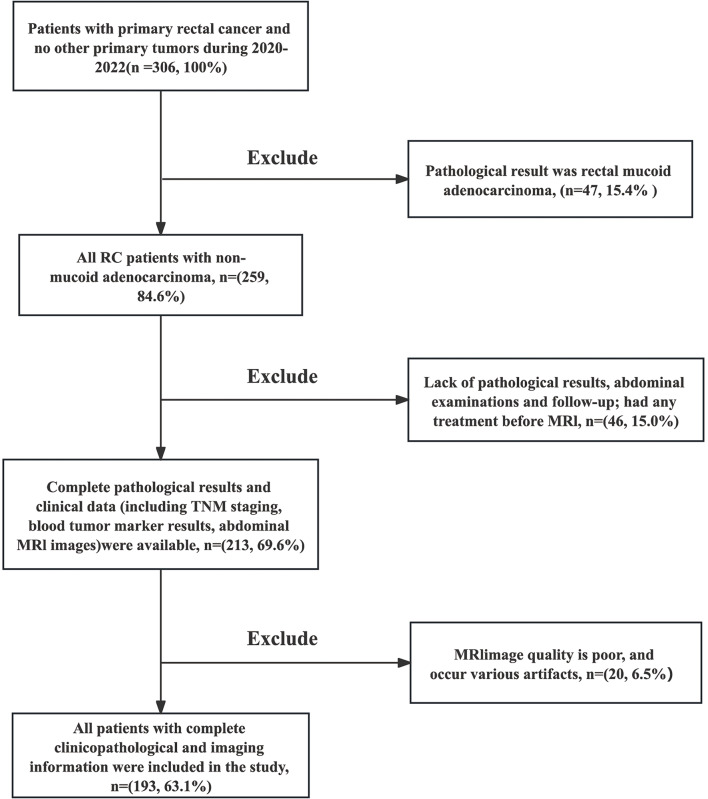

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 193 patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma through preoperative colonoscopy and pathological examination at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University from January 2020 to December 2022. All these patients were followed up until death or last follow-up of December 2023.The inclusion criteria were as follows (refer to Fig. 1): (I) all patients had complete RC MRI images and (II) had no history of any treatment before MRI; (III) complete pathological results and clinical data (including TNM staging, blood tumor marker results, abdominal MRI, or CT images) were available. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) pathological results indicated rectal mucoid adenocarcinoma, because mucoid composition can affect the delineation of lesions (n = 47, 15.4%); (II) poor MRI image quality with various artifacts (n = 20, 6.5%); (III) lack of pathological results, abdominal examinations, and follow-up (n = 46, 15.0%). These patients were randomly allocated into two groups: the training set (n = 136) and the validation set (n = 57), maintaining a ratio of 7:3.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of inclusion and exclusion criteria

MR Imaging Protocol

MRI examinations were conducted using a Discovery MR750w 3.0T MR scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) equipped with a phased-array coil, following a standardized protocol that captured oblique axial, sagittal, and coronal views perpendicular to the maximum diameter of the rectal tumor. High-resolution the oblique axial T2-weighted images were analyzed in this study. Before the MRI scan, the enema was administered using water to minimize artifacts caused by intestinal contents in the image. For this study, the oblique axial T2WI was performed with the following protocol: TR/TE, 5248/77; field of view (FOV), 26 cm; and 5-mm thickness with 1 mm slice spacing.

Lesion segmentation, imaging features extraction and selection

We utilized 3D Slicer 5.1.0 (http://www.slicer.org) to delineate the ROI and extract image features. The Region of Interest (ROI) was defined as the lesions with the largest cross-sectional area and relatively clear boundaries. In this study, we chose the layer displaying the perpendicular to the maximum diameter of the rectal tumor on the MR oblique axial T2-weighted image for delineation. As per PyRadiomics, radiomics features are categorized into the following classes: first-order features, shape-based (3D) features, shape-based (2D) features, and textural features. Specifically, the textural features are further divided into five textural matrices, namely gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), gray level run length matrix (GLRLM), gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM), neighboring gray tone difference matrix (NGTDM), and gray level dependence matrix (GLDM).

To assess the interobserver reproducibility of radiomics features, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each extracted radiomics feature within the ROIs. Features with an ICC below 0.75 were excluded from further analysis [23].Two experienced radiologists with 10 and 15 years of experience, blinded to patient clinical and pathological information, were chosen to outline the ROI on the omnidirectional T2WI maps and extract radiomics features. To ensure result accuracy, a senior radiologist with 20 years of experience meticulously reviewed the results. Any discrepancies between the two radiologists in assessing these features were resolved with the assistance of another medical professional.

LASSO regression was employed for variable screening to select radiomics features strongly associated with liver metastasis. Various types of machine learning algorithms exist, with LASSO being the most commonly used and demonstrated to exhibit optimal performance [24, 25]. LASSO can reduce the computational complexity of subsequent studies and, at the same time, minimize data overfitting to improve data reliability, and it can effectively identify important feature values with non-zero coefficients [26, 27].A 5-fold cross-validation was employed to determine the most appropriate lambda value (Fig. 2a). The lambda value associated with the smallest deviation was deemed the most appropriate. This corresponds to the lambda values indicated by the dashed line on the left in Fig. 2a. Simultaneously, having the smallest error helps avoid overfitting and ensures model simplicity. LASSO coefficient profiles of the radiomics features are depicted in Fig. 2b. With an increase in the lambda value, the coefficient of each feature tended to approach zero. This filtering process excludes unimportant features, retaining only those with non-zero coefficients, thereby enhancing the robustness of the model. Subsequently, we will conduct multivariate Cox analysis on radiomics features that have undergone dimensionality reduction through LASSO regression analysis. Coefficients and p-values of radiomics features were obtained. Statistical significance was assessed using the p-value. Radiomics features with a p-value greater than 0.05 will be discarded (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

The plots of radiomics features selection (a) The dashed line on the left represents the smallest lambda value, corresponding to the point of the smallest deviation. The lambda value associated with the smallest deviation was deemed the most appropriate, having the smallest error helps avoid overfitting and ensures model simplicity. In this case, the associated radiomics features are 10. (b) LASSO coefficient profiles of the radiomics features are depicted. With an increase in the lambda value, several unimportant features are filtered out, retaining features with non-zero coefficients. (c) The bar chart depicts the results of multivariate Cox analysis of radiomics features, with the p-value of each feature shown. The dashed line represents a p-value equal to 0.05, and all features with a p-value greater than 0.05 will be discarded, five features with p values less than 0.05 were retained

KRAS mutation status testing

The pathological samples of all the patients were obtained before primary tumor resection. Paraffin sections were prepared from the tumor tissue of each patient diagnosed with RC in this study. Subsequently, the paraffin sections underwent histological assessment. DNA extraction from paraffin sections was conducted for KRAS gene mutation analysis using the ConcertBio FFPE gDNA extraction kit (ConcertBio Co., Ltd.). Concentration of the extracted DNA was determined using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and fragment distribution was assessed with the QIAxcel Advanced System (QIAGEN Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, mechanical fragmentation of genomic DNA (gDNA) was achieved using the Covaris M220 Focused-ultrasonicator. Following terminal repair, joint connection, amplification, magnetic bead purification, and additional procedures, the library was constructed, and samples with index labels were obtained. Finally, library samples with different indices were pooled, and sequencing was performed using the paired-end 100 bp reads (PE100) sequencing strategy on the MGISEQ2000 sequencing platform (MGI Tech Co., Ltd.).

Model construction and validation

Logistic regression analysis was employed to construct three prediction models: clinical model, radiomics model, and a combined model (radiomics + clinical), aiming to predict the probability of liver metastasis in RC patients. ROC curve analysis was employed to assess the predictive efficiency of each model in the training set. The AUC (95%CI), sensitivity, specificity, false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) for each of the three models were determined. The predictive performance of three models was internally validated by 10-fold cross-validation in the training set. In this method, the dataset is randomly partitioned into 10 equally sized subsets, or “folds”. The model is then trained on 9 of these folds (the training set) and tested on the remaining 1 fold (the test set). This process is repeated 10 times, with each of the 10 folds serving as the test set once. The results from each iteration are then averaged to provide a more reliable estimate of the model’s performance. Moreover, the predictive performance of the models will undergo further testing in the validation set. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was employed to illustrate the net benefits at threshold probabilities for each of the three models. Calibration curves of the combined model were analyzed in both the training and validation sets.

Statistical analysis

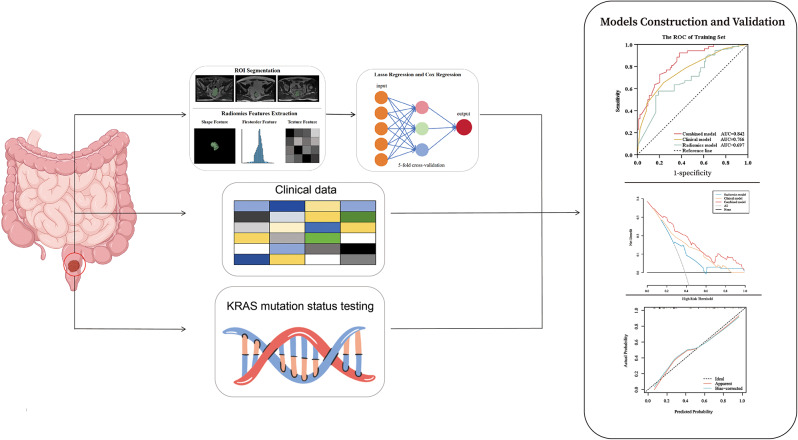

All statistical analyses were performed using Python (version 3.10.9), R (version 4.2.3), and SPSS (version 27.0.1.0). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Mann-Whitney U tests were employed, using SPSS software, to assess the differences in age, gender, TNM stage, CEA, CA199, and KRAS mutation status between the training and validation sets. LASSO regression and multivariate Cox analysis, based on the R language, were employed to reduce the dimensionality of the radiomics features. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted, using R software, to select radiomics and clinical features and construct prediction models. Diagnostic performance was compared through ROC analysis, and differences in AUCs between these models were compared using DCA. In this study, numerous R packages, including “rms,” “ggplot,” “survival,” “pROC,” “rmda,” “glmnet,” “lrm,” and “Hmisc,” were employed to conduct LASSO and Cox analyses, build the nomogram, plot the AUC, perform DCA, and generate calibration curves. The R packages were deposited into the public database (https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/). Figure 3 illustrates the workflow of this study.

Fig. 3.

Framework of the necessary steps in this study. ROIs in RC were delineated, and MRI images were segmented using a three-dimensional, semi-automatic segmentation method by two radiologists. Radiomics features of the ROI were quantified, encompassing shape, first-order, and texture features, using 3D Slicer. LASSO regression and Cox regression were employed to select radiomics features with statistical significance. We assessed the performance of the three models using ROC and DCA curve. Finally, we examined the calibration curves of the combined model

Results

Patients

The study comprised a total of 193 patients, with 136 randomly allocated to the training set and 57 assigned to the validation set in a 7:3 ratio. Simple randomization technique based R was used to group patients. Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of all patients. The TNM stage was categorized into two groups: T1-2 and T3-4. No significant differences in age or gender were detected between RCLM (+) group and RCLM (-) group. Between these two groups, significant differences were observed in TNM stage (p = 0.008), CEA (p < 0.001), CA199 (p = 0.015), and KRAS mutation (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of all patients

| Characteristic | Total (n = 193) |

Training Set (n = 136) | Validation Set (n = 57) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCLM(+) (n = 52) |

RCLM(-) (n = 84) |

p value | RCLM(+) (n = 25) |

RCLM(-) (n = 32) |

p value | ||

| Age: mean ± SD | 62.8 ± 5.6 | 63.1 ± 5.2 | 62.8 ± 5.5 | 0.728 | 62.8 ± 5.8 | 62.4 ± 6.6 | 0.606 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 103(53.4%) | 30(57.7%) | 41(48.8%) | 12(48.0%) | 20(62.5%) | ||

| Female | 90(46.6%) | 22(42.3%) | 43(51.2%) | 0.315 | 13(52.0%) | 12(37.5%) | 0.278 |

| TNM stage | |||||||

| I- II | 41(21.2%) | 7(13.5%) | 24(28.6%) | 2(8.0%) | 8(25.0%) | ||

| III- IV | 152(78.8%) | 45(86.5%) | 60(71.4%) | 0.008* | 23(92.0%) | 24(75.0%) | 0.097 |

| CEA | |||||||

| ≤ 5 ng/mL | 89(46.1%) | 19(36.5%) | 50(59.5%) | 5(20.0%) | 15(46.9%) | ||

| >5 ng/mL | 104(53.9%) | 33(63.5%) | 34(40.5%) | <0.001* | 20(80.0%) | 17(53.1%) | 0.037* |

| CA199 | |||||||

| ≤ 37 U/mL | 78(40.4%) | 16(30.8%) | 37(44.0%) | 7(28.0%) | 18(56.2%) | ||

| >37 U/mL | 115(59.6%) | 36(69.2%) | 47(56.0%) | 0.015* | 18(72.0%) | 14(43.8%) | 0.035* |

| KRAS mutation | |||||||

| Yes | 45(23.3%) | 24(46.2%) | 7(8.3%) | 11(44.0%) | 3(9.4%) | ||

| No | 148(76.7%) | 28(53.8%) | 77(91.7%) | < 0.001* | 14(56.0%) | 29(90.6%) | 0.003* |

CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA199 carbohydrate antigen 199, both of them were derived from patient blood tests

*p < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference

Features selection, construction, and validation of prediction models

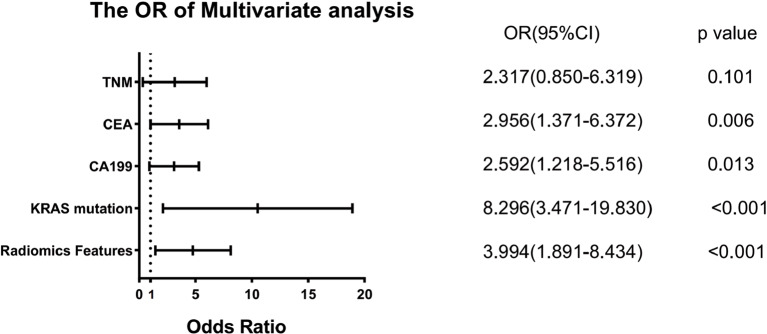

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to investigate the risk factors of liver metastasis in patients with RC. The results indicated that TNM stage, CEA, CA199, KRAS mutation, and radiomics features were statistically significant in the univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2).The multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis determined that CEA, CA199, KRAS mutation, and Radiomic Features were independent risk factors for liver metastasis (Table 2).Among these factors, KRAS mutation exhibited the most prominent effect on liver metastasis in patients with RC(odds ratios (OR): 8.296; 95%CI: 3.471–19.830; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).Consequently, we concluded that the KRAS mutation status serves as an independent predictor of liver metastasis in patients with RC.

Table 2.

The univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factor for liver metastasis of all patients

| Parameters | Univariate analysis | p value | Multivariate analysis | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |||

| Age | 1.011 | 0.960–1.064 | 0.687 | |||

| Gender | 1.082 | 0.607–1.928 | 0.789 | |||

| TNM stage | 2.878 | 1.286–6.442 | 0.010* | 2.317 | 0.850–6.319 | 0.101 |

| CEA | 2.815 | 1.536–5.158 | < 0.001* | 2.956 | 1.371–6.372 | 0.006* |

| CA199 | 2.117 | 1.151–3.892 | 0.016* | 2.592 | 1.218–5.516 | 0.013* |

| KRAS mutation | 8.833 | 4.015–19.433 | < 0.001* | 8.296 | 3.471–19.830 | < 0.001* |

| Radiomics Features | 3.326 | 1.690–6.544 | < 0.001* | 3.994 | 1.891–8.434 | < 0.001* |

*p < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference

Fig. 4.

The forest plot of the OR of multivariate analysis for liver metastasis. The dashed line indicates that the OR value is equal to 1, indicating that the clinical features included in the study have no significant effect on liver metastasis. When the OR value is greater than 1, it indicates that the clinical factor is a risk factor for liver metastasis. When the OR value is less than 1, it indicates that the clinical feature inhibits the occurrence of liver metastasis. The OR value of KRAS mutation was the highest, which indicates that KRAS mutation is strongly associated with liver metastasis in RC patients

Of the 107 extracted radiomics features (Supplementary Table 1), 12 features with ICC lower than 0.75 were excluded. In total, 95 quantitative radiomics features were retained for subsequent analysis, comprising 12 shape-based features, 15 first-order features, 19 GLCM features, 13 GLDM features, 16 GLRLM features, 16 GLSZM features, and 4 NGTDM features. The details of these 95 radiomics features are available in Supplementary Table 2. After LASSO and multivariate COX regression analyses, ultimately, 5 radiomics features—Imc1, Coarseness, Large Dependence Low Gray Level Emphasis, Zone Entropy, and Gray Level Non Uniformity—were selected. Furthermore, 3 clinical features—CEA, CA199, and KRAS mutation—were included following multivariate logistic regression analysis. These features will be used in the construction of later prediction models.

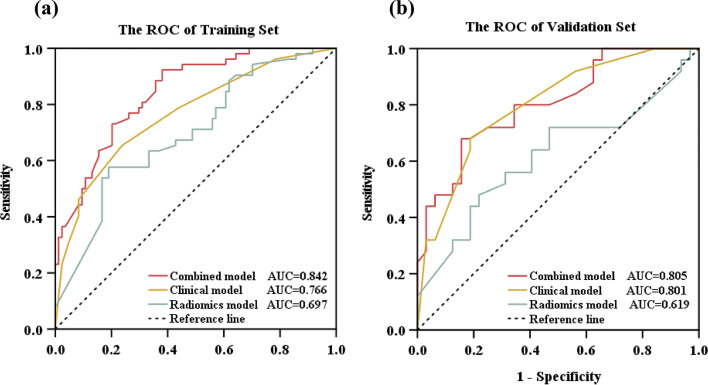

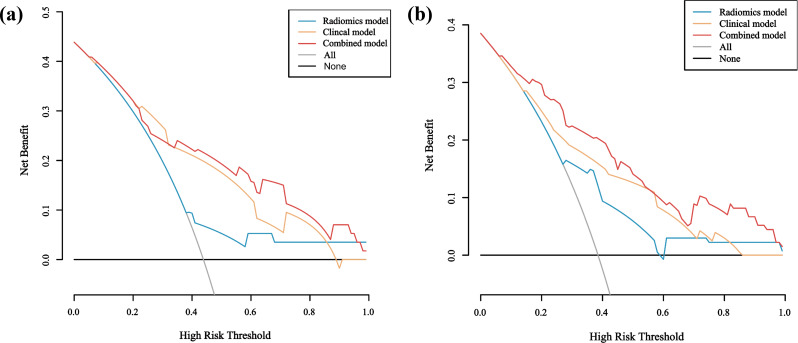

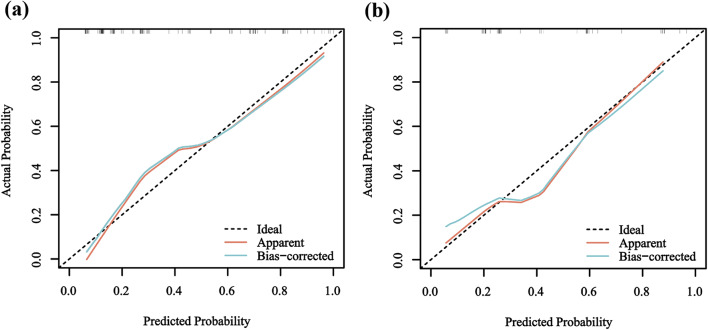

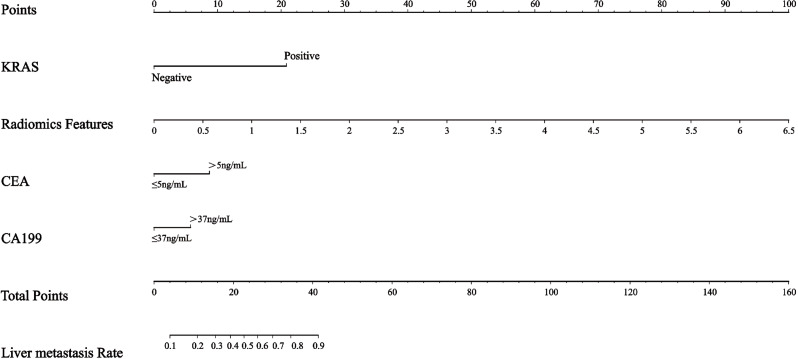

We constructed three prediction models: clinical, radiomics, and combined models. The clinical model was developed using three factors—CEA, CA199, and KRAS mutation. The radiomics model comprised 5 features with p values less than 0.05, as depicted in Fig. 2C. The combined model was formulated by integrating the radiomics model into the clinical model, with corresponding OR of 2.956 for CEA, 8.296 for KRAS mutation, 2.592 for CA199, and 3.994 for radiomics features, as summarized in Table 2. First, we performed internal validation of the three models using 10-fold cross-validation. The results showed that the clinical model had an AUC of 0.731, the radiomics model had an AUC of 0.721, and the combined model had an AUC of 0.870. This also indicates that the combined model’s predictive performance is superior to that of both the clinical model and the radiomics model. Figure 5 depicts the ROC curves of the clinical, radiomics, and combined models, illustrating their capability to differentiate liver metastasis from non-liver metastasis in both the training and validation sets. Table 3 provides a summary of the detailed information for the three models. In the training set, the AUC value of the combined model (AUC: 0.842, 95%CI: 0.778–0.907) surpassed that of the radiomics model (AUC: 0.697, 95%CI: 0.607–0.787) and the clinical model (AUC: 0.766, 95%CI: 0.683–0.850), suggesting an enhanced predictive performance for liver metastasis in patients with RC. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the combined model outperformed any single model in terms of prediction accuracy. This observation was validated with an AUC of 0.805 (95%CI: 0.692–0.918) for the combined model in the validation set. Furthermore, Fig. 6 displays the DCA curve, calculated to assess the net benefit of the three models. The DCA demonstrated that utilizing the combined model for predicting liver metastasis in patients with RC would yield greater benefits compared to the clinical and radiomics models. Figure 7 illustrates the calibration curves of the combined model in both the training and validation sets. A predictive nomogram was generated in Fig. 8, incorporating all features with p < 0.05 derived from the multivariable logistic regression analysis for liver metastasis in patients with RC.

Fig. 5.

The ROC of three models in Training (a) and Validation (b) Sets for predicting liver metastasis. The AUC of the combined model in both the training and validation sets was higher than that of the radiomics model and the clinical model

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of the radiomics model, clinical model, and the combined model in training and validation sets for predicting liver metastasis

| Data Set | Model | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | False positive | False negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | Radiomics model | 0.697(0.607–0.787) | 0.577 | 0.810 | 0.190 | 0.423 |

| Clinical model | 0.766(0.683–0.850) | 0.654 | 0.762 | 0.238 | 0.346 | |

| Combined model | 0.842(0.778–0.907) | 0.923 | 0.619 | 0.381 | 0.077 | |

| Validation Set | Radiomics model | 0.619(0.466–0.772) | 0.480 | 0.781 | 0.219 | 0.520 |

| Clinical model | 0.801(0.687–0.915) | 0.680 | 0.508 | 0.492 | 0.320 | |

| Combined model | 0.805(0.692–0.918) | 0.680 | 0.844 | 0.156 | 0.320 |

Fig. 6.

The DCA curve of training and validation sets. The DCA curves for the three models in the training (a)and validation(b) sets were compared. The x-axis represents the high-risk threshold probability, and the y-axis indicates the net benefit. The gray oblique line represents the net benefit of intervention for all patients, while the horizontal line represents the net benefit of no intervention. Notably, the combined model achieved a higher net benefit than other models across the major range of threshold probability

Fig. 7.

The calibration curves of combined model in Training and Validation Sets. (a) Calibration curves of combined model in training set. (b) Calibration curves of combined model in validation set. Calibration curves illustrate the calibration of the combined models by assessing the agreement between the predicted risks of liver metastasis and the observed outcomes. The y-axis illustrates the actual liver metastasis rate, while the x-axis depicts the predicted liver metastasis risk. The diagonal dotted line represents a perfect prediction made by an ideal model. The blue line represents the performance of the combined model, with a closer alignment to the diagonal dotted line indicating a more accurate prediction

Fig. 8.

The nomogram for predicting liver metastasis in RC patients

Discussion

In our study, we identified the value of KRAS mutation, with the highest OR, as an independent predictor of liver metastasis. The integrative models (AUC: 0.842, 95%CI: 0.778–0.907), which combined radiomics with CEA, CA199, and KRAS mutation, demonstrated improved predictive power for liver metastasis compared to models constructed with any single factor in the training set. The sensitivity and specificity of the combined model were 0.923 and 0.619 in the training set, and 0.680 and 0.844 in the validation set, indicating the combined model can offer a more comprehensive set of information than each individual model alone. However, the combined model showed relatively low specificity in the training set, so it is necessary to improve the specificity of the combined model in future clinical applications. Furthermore, on the basis of clinical and radiomics features, we developed a nomogram as an individualized and visual tool to offer the estimated probability of liver metastasis for a newly diagnosed RC. Decision curves analysis was performed, the combined model achieved a higher net benefit than other models across the major range of threshold probability in both training and validation sets. Calibration curves were also built to illustrate the calibration of the combined models.

Currently, various clinical characteristics, including age, gender, CEA, CA199, TNM, and tumor size, among others, are utilized for predicting liver metastasis in RC. In comparison to these common characteristics, our study introduces a unique predictive factor—KRAS mutation status, exhibiting the highest OR of 8.296 among all features, indicating its excellent capacity to predict liver metastasis. Previous studies have attempted to investigate the relationship between radiomics features and KRAS gene mutations in CRC, CRLM, or RC. Lubner et al. [28] suggested that in patients with CRLM, CT-based texture features were correlated with tumor TNM stage, baseline serum CEA value, and KRAS gene mutation status. Our findings aligned with the study conducted by Hutchins et al. [29]and Modest et al. [10] whom reported that KRAS served as an adverse prognostic factor, impacting PFS and OS in RC patients. Nevertheless, the role of KRAS in RCLM remains somewhat controversial. In contrast, another study reported no significant association between KRAS mutation status and the PFS or OS [30]. This might be attributed to limited sample sizes and the inclusion of single-center studies. Our clinical model also incorporated additional variables, including CA199 and CEA, a previous study showed the elevated CA199 and elevated CEA was associated with liver metastasis [29, 31], this is consistent with our research. Chuang et al. [32]showed that preoperative serum CEA levels could affect the probability of liver metastasis in CRC patients after radical resection. This is consistent with this study.

Due to the limitations of histopathological methods, predicting liver metastasis in RC patients requires a more comprehensive approach, including associated imaging techniques. Recently, there have been limited studies on rectal MRI aimed at identifying noninvasive independent predictors of liver metastasis. Assessing RCLM in MRI images visually is subjective and inherently limited, thereby compromising its clinical significance. Consequently, several studies had sought to apply potential quantitative radiomics features for predicting liver metastasis in RC. Radiomics, which integrates numerous high-dimensional imaging features for quantifying tumor heterogeneity, has the potential to enhance oncologic diagnosis and prognosis prediction. A study based on CT scans revealed that radiomics can provide valuable biomarkers for identifying patients at a high risk of developing CRLM [33]. Li et al. investigated CT-based radiomics analyses of primary tumors (colon and/or rectum) to predict synchronous liver metastases. Their first study enrolled 48 colon cancer patients and built a two-dimensional radiomics model based on a single slice of the tumor region. Their radiomics model achieved an AUC of 0.85 and was internally validated by repeated cross-validation [34]. The second study included a larger sample size of CRC patients (n = 100), and the model had an AUC of 0.79 on the validation set [35]. Liang et al. [36] showed that the radiomics model based on baseline rectal MRI has a high potential to predict heterochronic liver metastases, and they speculated that adjusting follow-up strategies and developing improved MRI imaging methods may help improve the survival rate and prognosis of patients with RC. The findings of a recent study applying radiomics analysis based on MRI to predict preoperative synchronous distant metastasis in RC were encouraging, Liu at al. [31] revealed that the clinical-radiomics combined model, with AUC of 0.847 and 0.827, exhibited superior performance compared to the clinical model in both the training and validation datasets. Zhang et al. [37]demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-radiomics models as a visual prognostic tool for predicting lymphatic vascular infiltration in rectal cancer. Consistent with our research, our results are also promising, particularly regarding the enhanced prediction power of the combined model in comparison to the any single model, this may be due to the fact that the combined model obtains more information than the any single model, which can evaluate the patient’s condition more comprehensively. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the predictive efficiency of the combined model surpasses that of individual models [31, 38, 39]. These studies are consistent with this study, and also show that the predictive power of the combined model is better than that of any single model. The results of this study show that the AUC value of the radiomics model in the training set is 0.697, which may be related to the small sample size of this study and the inclusion of only unimodal-based radiomics features. The FP and FN of the combined model were 0.381 and 0.077, respectively, this may be due to the fact that we used limited methods for dimensionality reduction on the data, leading to the inclusion of redundant or irrelevant features in the model. Another possible reason is that our model is relatively simple, which limits its ability to capture the complexity of the data. Limited training data might not provide enough examples for the model to learn effectively, leading to missed positive instances. Due to limitations in the experimental design and sample size, the above issues will be addressed in future research. For example, we will use multiple methods for dimensionality reduction and remove redundant or irrelevant features to improve the model’s accuracy, test more complex models or algorithms that may better capture the underlying patterns in the data and collect more data, especially positive samples, to provide a more comprehensive training set that can help the model learn to identify positives more effectively. In future studies, multi-modal studies based on multi-directional and multi-sequence radiomics features such as T1 enhanced sequences and diffuse-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences should be further combined. The radiomics features in our study were computed exclusively using high-resolution oblique axial T2-weighted images, as T2WI is the essential and pivotal sequence in the assessment of primary RC [40]. However, the combined model, which combines the radiomics model with clinical features, greatly improves the AUC value and predictive efficiency of the model. Therefore, routine examination of KRAS gene mutation status in RC patients, along with other clinical and radiomics indicators, is of great significance to help clinicians identify liver metastases quickly and early. Extensive research has been conducted on the relationship between radiomics or clinical features and liver metastasis in numerous previous studies. However, there is limited exploration of the impact of combining genomics with radiomics on liver metastasis. A prior study demonstrated that integrating radiomics features with clinical information, including age, sex, T stage, and N stage, enhanced performance compared to a standardized prediction model using only clinical information [41].The distinction lies in the fact that our study integrated pertinent information from genomics and radiomics based on MRI to predict liver metastasis in RC. Our proposed combined prediction model validated the viability of MR T2WI-based radiomics analysis, offering a potentially effective and user-friendly model for clinical practice. This integration effectively identifies patients at a high risk of liver metastasis and enhances the model’s robustness for informing clinical decision-making and follow-up treatment. By utilizing our nomogram, clinicians can calculate an estimated probability of liver metastasis by referencing the selected T2WI-based radiomics features, MRI staging, KRAS mutation status and other clinical information. MRI-based radiomics approaches may indicate the presence of latent lesions that are not visible with current imaging modalities. Individualized treatment strategies may change based on early detection of metastases, and more high-risk patients with metastases may have the opportunity to receive individualized treatment and improve outcomes.

The study has several limitations. Firstly, it is a single-center study with a small sample size and only internal validation. In future studies, the reproducibility of the predictive model in this study under different imaging modalities should be demonstrated by more external validation. Then, although this study included all RC patients in stages T1-2 and T3-4, and although this staging was reasonable when analyzing the relationship between imaging characteristics and genetic status of RC patients, it may be a better choice to include only patients in stage 4, because in terms of KRAS gene mutation, stage 4 RC patients have low heterogeneity within the tumor [42]. Secondly, due to the lack of a standardized definition and effective reference value for radiomics at present, different results may be produced when the same radiomics data are analyzed using different image conversion techniques or feature selection methods. The absence of standardization may influence the reproducibility of our results and the generalizability of our conclusions. In the future, we will advocate for the development and adoption of standardized protocols and reference values within the radiomics community. We will also suggest collaborative efforts to create comprehensive guidelines that can enhance consistency across studies. Furthermore, in most studies, the selection and delineation of ROI are still performed manually, significantly increasing the workload of doctors and introducing subjectivity that could potentially affect the subsequent model establishment, resulting in low repeatability and similarity of results. Moreover, a more sensitive imaging modality, such as liver contrast-enhanced MRI, is not commonly utilized in routine practice due to limited resources and high costs. Finally, we exclusively conducted oblique axial T2WI-based radiomics analysis to construct models. We anticipate that incorporating more sequences could enhance the predictive value of radiomics analysis in the future. Combining conventional MRI sequences with some of the latest functional sequences, such as DWI and T1 enhanced sequence, may help to extract more valuable features and thus build models stably and efficiently. Therefore, prior to clinical application, future research will necessitate large sample sizes, multi-center approaches, and a comprehensive exploration of multiple variables to validate our prediction models. Meanwhile, develop a user-friendly interface for the nomogram that can be incorporated into electronic health record systems or as a standalone tool accessible via a web or mobile application.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study affirms that KRAS mutation serves as an independent predictor of liver metastasis in patients with RC. Furthermore, the combined model, constructed with radiomics features based on MR T2WI and a clinical model based on CEA, CA199, and KRAS mutation, demonstrates the most excellent performance in predicting liver metastasis. The nomogram shows promising clinical potential for predicting liver metastasis. These findings can aid in identifying high-risk patients with liver metastasis and managing them appropriately, it can improve the long-term survival rate and prognosis of patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CRLM

Colorectal liver metastasis

- CT

Computed tomography

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FOV

Field of view

- GLCM

Gray level co-occurrence matrix

- GLCME

Entropy of GLCM

- GLDM

Gray level dependence matrix

- GLRLM

Gray level run length matrix

- GLSZM

Gray level size zone matrix

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- NGTDM

Neighboring gray tone difference matrix

- OR

Odds ratio

- OS

Overall survival

- PET

Positron emission computed tomography

- PFS

Progression free survival

- RC

Rectal cancer

- READ

Rectal adenocarcinoma

- RI

Retention index

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- ROI

Region of interest

- SUV

Maximum standard uptake value

- US

Ultrasound

- WHO

World health organization

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MJQ, LH, SSM and WYP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LXF and MJQ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.Conceptualization: LXF and MJQ; Methodology: LXF, MJQ, LH, SSM and WYP; Formal analysis and investigation: MJQ, LH, SSM and WYP; Writing - original draft preparation: MJQ; Writing - review and editing: LXF; Funding acquisition: LXF; Resources: LXF, NXS, KXJ, XLQ, LN, HLL; Supervision: NXS, KXJ, XLQ, LN, HLL.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps [2021AB029].

Data availability

Due to sensitivity reasons, the data supporting this study cannot be made publicly available. Data access can be obtained through a formal request and authorization process.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machackova T, Prochazka V, Kala Z, Slaby O. Translational potential of micrornas for preoperative staging and prediction of chemoradiotherapy response in rectal cancer. Cancers. 2019;11(10):E1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valderrama-Treviño AI, Barrera-Mera B, Ceballos-Villalva JC, Montalvo-Javé EE. Hepatic metastasis from Colorectal Cancer. Euroasian J Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2017;7(2):166–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos JL. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49(17):4682–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruera G, Cannita K, Di Giacomo D, Lamy A, Troncone G, Dal Mas A, et al. Prognostic value of KRAS genotype in metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) patients treated with intensive triplet chemotherapy plus bevacizumab (FIr-B/FOx) according to extension of metastatic disease. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JC, Renfro LA, Al-Shamsi HO, Schrock AB, Rankin A, Zhang BY, et al. Non-V600BRAF MutadefineDefclinicallyidistinctsmolecularesubtypeubtymetastaticscolorectalrcancerCancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2624–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanelli GN, Dal Pozzo CA, Depetris I, Schirripa M, Brignola S, Biason P, et al. The heterogeneous clinical and pathological landscapes of metastatic braf-mutated colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao W, Zhou J, Zhang H, Qiu L, Tan H, Hu Y, et al. Relationship between KRAS mutations and dual time point 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in colorectal liver metastases. Abdom Radiol N Y. 2019;44(6):2059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modest DP, Ricard I, Heinemann V, Hegewisch-Becker S, Schmiegel W, Porschen R, et al. Outcome according to KRAS-, NRAS- and BRAF-mutation as well as KRAS mutation variants: pooled analysis of five randomized trials in metastatic colorectal cancer by the AIO colorectal cancer study group. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1746–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R, Marwah S, Silver M, Tzardi M, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(3):465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zilkens C, Miese F, Herten M, Kurzidem S, Jäger M, König D, et al. Validity of gradient-echo three-dimensional delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of hip joint cartilage: a histologically controlled study. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(2):e81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrasekar V, Ansari MY, Singh AV, Uddin S, Prabhu KS, Dash S, et al. Investigating the Use of Machine Learning models to understand the drugs permeability across Placenta. IEEE Access. 2023;11:52726–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansari MY, Qaraqe M, Charafeddine F, Serpedin E, Righetti R, Qaraqe K. Estimating age and gender from electrocardiogram signals: a comprehensive review of the past decade. Artif Intell Med. 2023;146:102690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansari MY, Yang Y, Meher PK, Dakua SP. Dense-PSP-UNet: a neural network for fast inference liver ultrasound segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2023;153:106478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansari MY, Yang Y, Balakrishnan S, Abinahed J, Al-Ansari A, Warfa M, et al. A lightweight neural network with multiscale feature enhancement for liver CT segmentation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansari MY, Abdalla A, Ansari MY, Ansari MI, Malluhi B, Mohanty S, et al. Practical utility of liver segmentation methods in clinical surgeries and interventions. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22(1):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rai P, Ansari MY, Warfa M, Al-Hamar H, Abinahed J, Barah A, et al. Efficacy of fusion imaging for immediate post-ablation assessment of malignant liver neoplasms: a systematic review. Cancer Med. 2023;12(13):14225–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fusco R, Granata V, Petrillo A. Introduction to Special Issue of Radiology and Imaging of Cancer. Cancers. 2020;12(9):E2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SJ, Pak K, Kim K. Diagnostic performance of F-18 FDG PET/CT for prediction of KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol. 2019;44(5):1703–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai D, Wang Y, Zhu L, Jin H, Wang X. Prognostic value of KRAS mutation status in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based competing risk analysis. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi R, Chen W, Yang B, Qu J, Cheng Y, Zhu Z, et al. Prediction of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF status in colorectal cancer patients with liver metastasis using a deep artificial neural network based on radiomics and semantic features. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(12):4513–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang YQ, Liang CH, He L, Tian J, Liang CS, Chen X, et al. Development and validation of a Radiomics Nomogram for Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichling C, Taieb J, Derangere V, Klopfenstein Q, Le Malicot K, Gornet JM, et al. Artificial intelligence-guided tissue analysis combined with immune infiltrate assessment predicts stage III colon cancer outcomes in PETACC08 study. Gut. 2020;69(4):681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muthukrishnan R, Rohini R. LASSO: A feature selection technique in predictive modeling for machine learning. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Computer Applications (ICACA) [Internet]. Coimbatore, India: IEEE; 2016 [cited 2024 Sep 27]. p. 18–20. Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7887916/

- 27.Xue F, Yang L, Dai B, Xue H, Zhang L, Ge R, et al. Bioinformatics profiling identifies seven immune-related risk signatures for hepatocellular carcinoma. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubner MG, Stabo N, Lubner SJ, del Rio AM, Song C, Halberg RB, et al. CT textural analysis of hepatic metastatic colorectal cancer: pre-treatment tumor heterogeneity correlates with pathology and clinical outcomes. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(7):2331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J, et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HS, Heo JS, Lee J, Lee JY, Lee MY, Lim SH, et al. The impact of KRAS mutations on prognosis in surgically resected colorectal cancer patients with liver and lung metastases: a retrospective analysis. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Zhang C, Wang L, Luo R, Li J, Zheng H, et al. MRI radiomics analysis for predicting preoperative synchronous distant metastasis in patients with rectal cancer. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(8):4418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang SC, Su YC, Lu CY, Hsu HT, Sun LC, Shih YL, et al. Risk factors for the development of metachronous liver metastasis in colorectal cancer patients after curative resection. World J Surg. 2011;35(2):424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taghavi M, Trebeschi S, Simões R, Meek DB, Beckers RCJ, Lambregts DMJ, et al. Machine learning-based analysis of CT radiomics model for prediction of colorectal metachronous liver metastases. Abdom Radiol N Y. 2021;46(1):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Eresen A, Shangguan J, Yang J, Lu Y, Chen D, et al. Establishment of a new non-invasive imaging prediction model for liver metastasis in colon cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9(11):2482–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li M, Li X, Guo Y, Miao Z, Liu X, Guo S, et al. Development and assessment of an individualized nomogram to predict colorectal cancer liver metastases. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10(2):397–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang M, Cai Z, Zhang H, Huang C, Meng Y, Zhao L, et al. Machine Learning-based analysis of rectal Cancer MRI Radiomics for Prediction of Metachronous Liver Metastasis. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(11):1495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, He K, Guo Y, Liu X, Yang Q, Zhang C, et al. A Novel Multimodal Radiomics Model for Preoperative Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in rectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng H, Chen L, Wang M, Luo Y, Huang Y, Ma X. Integrative radiogenomics analysis for predicting molecular features and survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging. 2021;13(7):9960–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Chen XL, Liu H, Lu T, Li ZL. MRI-based multiregional radiomics for predicting lymph nodes status and prognosis in patients with resectable rectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1087882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jhaveri KS, Hosseini-Nik H. MRI of rectal Cancer: an overview and update on recent advances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(1):W42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S, Choe EK, Kim SY, Kim HS, Park KJ, Kim D. Liver imaging features by convolutional neural network to predict the metachronous liver metastasis in stage I-III colorectal cancer patients based on preoperative abdominal CT scan. BMC Bioinformatics. 2020;21(Suppl 13):382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldus SE, Schaefer KL, Engers R, Hartleb D, Stoecklein NH, Gabbert HE. Prevalence and heterogeneity of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations in primary colorectal adenocarcinomas and their corresponding metastases. Clin Cancer Res off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2010;16(3):790–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to sensitivity reasons, the data supporting this study cannot be made publicly available. Data access can be obtained through a formal request and authorization process.