Abstract

Microglia are resident central nervous system (CNS) macrophages. Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection of SJL/J mice causes persistent infection of CNS microglia, leading to the development of a chronic-progressive CD4+ T-cell-mediated autoimmune demyelinating disease. We asked if TMEV infection of microglia activates their innate immune functions and/or activates their ability to serve as antigen-presenting cells for activation of T-cell responses to virus and endogenous myelin epitopes. The results indicate that microglia lines can be persistently infected with TMEV and that infection significantly upregulates the expression of cytokines involved in innate immunity (tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-18, and, most importantly, type I interferons) along with upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II, IL-12, and various costimulatory molecules (B7-1, B7-2, CD40, and ICAM-1). Most significantly, TMEV-infected microglia were able to efficiently process and present both endogenous virus epitopes and exogenous myelin epitopes to inflammatory CD4+ Th1 cells. Thus, TMEV infection of microglia activates these cells to initiate an innate immune response which may lead to the activation of naive and memory virus- and myelin-specific adaptive immune responses within the CNS.

Microglia are bone marrow-derived, macrophage-like cells which populate the central nervous system (CNS). These cells perform both scavenger (phagocytic) functions and antigen-presenting cell (APC) functions (18, 32, 36, 51, 59). Microglia are activated early in response to infection or injury and are major players in both innate and immune-mediated CNS inflammatory responses (32, 58, 59). Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease in humans that is characterized by peripheral T-cell responses to myelin proteins such as myelin basic protein, proteolipid protein (PLP), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) (4, 14, 50, 67) and demyelinating lesions in the brain and spinal cord associated with the presence of both CD4+ T cells and activated microglia-macrophages (35, 62). Epidemiological evidence suggests that infection with a neurotropic virus may trigger the development of MS (33).

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease (TMEV-IDD) serves as a highly relevant virus-induced model for human MS (44). Infection of SJL/J mice with TMEV results in a life-long persistent infection of CNS microglia, macrophages, and astrocytes (9, 39, 40). A chronic progressive autoimmune demyelinating disease is observed, with onset of clinical signs beginning around 30 to 35 days postinfection (37). Clinical signs of ascending hind limb paralysis reflect the CNS parenchymal and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltration and demyelination (11, 13, 37). However, the chronic progressive stage of the disease is mediated largely by CD4+ myelin epitope-specific T cells activated via epitope spreading (47).

Microglia originate from bone marrow precursors and then migrate into the CNS during development and are considered to be a resident macrophage population based on their expression of F4/80, FcR, and Mac-1 (3, 18, 32, 36, 51, 59). The antigen-presenting ability of microglia is somewhat controversial. In MS, microglia have been shown to phagocytize myelin and express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II along with costimulatory molecules, thus indicating their potential to activate autoreactive CD4+ Th1 cells (1). In vitro studies have shown that microglia isolated from newborn rodents and humans are capable of functioning as APCs following activation with proinflammatory cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (1). However, microglia tested directly upon isolation from adult mouse brains exist in a quiescent state compared to splenic macrophages (6). Collectively, these studies indicate that activated microglia can perform APC functions, but the extent of their participation in the initiation and progression of CNS inflammatory diseases remains to be determined.

Previous studies addressing the consequences of virus infection of CNS-resident cells utilized microglial cell lines or whole brain macrophage populations and examined the expression of only a limited number of activation markers. Infection of a human microglial cell line with coronavirus showed increased nitric oxide (NO) production (17). Infection of a glial cell line with measles virus led to increased expression of MHC class I (15). A more recent study demonstrated the activation of a microglia-macrophage population in the brains of rats infected with bornavirus (66). Relevant to TMEV-induced demyelinating disease, previous studies have demonstrated that microglia-macrophages are the predominant persistently infected cells in the CNSs of susceptible mice (40) and that mouse brain macrophages can be infected with TMEV in vitro (31, 34). Collectively, these previous studies were unable to differentiate the effects of virus infection of resident microglia from those of CNS-infiltrating macrophages and, more importantly, failed to address the effects of virus infection on APCs and the effector function of these cells.

In the current study, we asked if TMEV infection of microglia activates their innate immune functions and/or their ability to serve as APCs for the activation of T-cell responses to virus and myelin epitopes. Microglia isolated from the brains of SJL/J mice could be persistently infected with TMEV in vitro, resulting in the upregulation of cytokines involved in the innate immune response (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-12 IL-18, and, most importantly, type I IFNs) along with a dramatic upregulation of IL-12 mRNA and surface expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules (B7-1, B7-2, and CD40). Microglia activated by TMEV infection were able to process and present both virus and myelin antigens to CD4+ Th1 lines as efficiently as microglia treated with IFN-γ. Therefore, microglia respond to direct TMEV infection by upregulating cytokines critical in the innate immune response and are also capable of stimulating adaptive immune responses to virus and self myelin proteins. This is the first report demonstrating that virus infection of a quiescent APC population can directly lead to activation of APC function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Pregnant (15 to 17 days) SJL/J mice were purchased from Harlan Labs (Bethesda, Md.). Mice were housed in the Northwestern University animal facility in accordance with university and National Institutes of Health animal care guidelines. Neonatal mice 1 to 3 days old were used for the isolation of microglia.

Antigens.

PLP139–151 (HSLGKWLGHPDKF), PLP56–70 (DYEYLINVIHAFQYV), PLP178–191 (NTWTTCQSIAFPSK), VP270–86 (WTTSQEAFSHIRIPLPH), and VP324–37 (PIYGKTISTPSDY) were purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, Ky). The amino acid composition was verified by mass spectrometry, and purity was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Intact bovine PLP was prepared from chloroform-methanol (2:1) extracts of bovine white matter as previously described (23).

Media.

Mixed glial cultures were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)-F12 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma), 6 g of glucose per liter, 2.4 g of NaHCO3 per liter, 0.37 g of l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) per liter, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin (Life Technologies) per ml. Microglial cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 20% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 3 ng of recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) per ml. T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies), minimum essential medium essential vitamins (Life Technologies), 0.1 mM asparagine (Life Technologies), 0.1 mg of folic acid (Life Technologies) per ml, 0.8% T-STIM (Collaborative Biomedical Research, Bedford, Mass.), and 0.2 U of recombinant IL-2 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) per ml. TMEV infection was conducted in DMEM with no supplements. Proliferation assays and T-cell stimulations were conducted in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 5 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol.

Isolation and culture of microglia.

Isolation of mixed glial cultures from neonatal mice was performed as previously described (24, 60, 65). Briefly, tissue culture flasks were coated for 3 h with 10 μg of poly-d-lysine (Sigma) per ml. The brains were removed from 1- to 3-day-old neonatal mice, and the meninges were removed. The left and right hemispheres of the brain were gently dissociated in a nylon mesh bag. The resulting cell suspension was passed through no. 60 and 100 stainless steel screens (Sigma). The cells were centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM-F12 complete medium. The cells were seeded in the poly-d-lysine-coated tissue culture flasks and incubated at 37°C. The medium was replaced at 3-day intervals. Following 10 to 14 days of incubation, microglia were removed from the astroglial layer by shaking of the flasks on an orbital shaker for 24 h at 300 rpm. The microglia which were shaken off into the medium were removed from the flasks and centrifuged. The microglia were resuspended in DMEM complete microglial medium and seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates coated with poly-d-lysine. The microglia were cloned by limiting dilution in DMEM complete microglia medium for 4 weeks to obtain pure microglial cultures. Microglial cultures were maintained for several months in 24-well tissue culture plates.

Virus infection.

The BeAn strain of TMEV was prepared and purified from confluent BHK-21 cells infected with the BeAn 8386 strain as previously described (38). Microglial cultures were infected with strain BeAn at a multiplicity of infection of 5. The microglia were washed twice with DMEM and then infected with the virus in DMEM. The infected cultures were incubated at 20°C for 1 h with intermittent shaking. Additional medium was added, and the microglia were incubated for 48 h at 34°C.

Cell surface staining.

Microglia cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates were incubated in the presence or absence of recombinant IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 24 h at 37°C or infected with the BeAn virus for 48 h. The cells were washed twice with cold fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 5% normal goat serum). Microglia were incubated with normal mouse serum and Fc receptor block for 30 min at 4°C. The microglia were then incubated for 45 min at 4°C with antibodies directly conjugated to biotin for the antigens Mac-1 (CD11b), CD45, CD40, ICAM-1 (CD54), B7-1 (CD80), B7-2 (CD86), H-2Ks (MHC class I), and I-As (MHC class II) or the appropriate isotype control antibody controls (PharMingen). Following the antibody binding, the microglia were washed twice with FACS buffer and then incubated with streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate for 30 min at 4°C. Microglia were washed twice before gentle removal of the cells from the surface. The stained cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur. The flow plots shown represent all of the cells derived from each of the various culture conditions, with 5 to 8% of the events consisting of cellular debris based on forward versus side scatter analysis.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR cytokine analysis.

Microglia were incubated in the presence or absence of recombinant IFN-γ, for 24 h, or infected with strain BeAn for 48 h for time periods predetermined to be optimal for gene expression under each condition. The cells were washed twice with PBS and then gently scraped from the surface of the tissue culture plate. The microglia were counted and pelleted, and total RNA was isolated from the cells by using an SV Total RNA Isolation Kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). First-strand cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA from the microglia by using oligo(dT)12–18 primers and an Advantage for RT for PCR Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.). Following synthesis, each cDNA sample was diluted in distilled water to a 100-μl volume and 10 μl was used for each PCR. Each PCR was conducted in a 50-μl volume containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 100 pmol of each 5′ and 3′ gene-specific primer, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.), and 10 μl of diluted cDNA. The primers were synthesized by Life Technologies. PCR cycle conditions were 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 40 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated on an ethidium bromide-containing 2% agarose gel, illuminated on a UV light source, and photographed using Polaroid type 667 film. Gel images were scanned into Adobe Photoshop using an Epson ES 1200-C scanner and imported as TIFF files into Kodak 1D Digital Science for densitometry. The sequences of the cytokine primers and the expected product sizes are as follows: IFN-α, 5′ primer 5′ GAC TCA TCT GCT GCT TGG AAT GCA ACC CTC C 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GAC TCA CTC CTT CTC CTC ACT CAG TCT TGC C 3′ (294 bp); IFN-β, 5′ primer 5′ CAG CTC CAG CTC CAA GAA AGG ACG AAC ATT CG 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ CCA CCA CTC ATT CTG AGG CAT CAA CTG ACA GG 3′ (509 bp); IL-1β, 5′ primer 5′ AAG CTC TCC ACC TCA ATG GAC AG 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ CTC AAA CTC CAC TTT GCT CTT GA 3′ (260 bp); IL-6, 5′ primer 5′ CCT CTG GTC TTC TGG AGT ACC AT 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GGC ATA ACG CAC TAG GTT TGC CG 3′ (307 bp); IL-10, 5′ primer 5′ CCA GTT TTA CCT GGT AGA AGT GAT G 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ TGT CTA GGT CCT GGA GTC CAG CAG ACT CAA 3′ (324 bp); IL-12 p40, 5′ primer 5′ ATG GCC ATG TGG GAG CTG GAG AAA G 3′ and 3′ 5′ GTG GAG CAG CAG ATG TGA GTG GCT 3′ (451 bp); IL-18, 5′ primer 5′ CTG TGT TCG AGG ATA TGA CTG 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GTG TCC TTC ATA CAG TGA AG 3′ (283 bp); TNF-α, 5′ primer 5′ GTT CTA TGG CCC AGA CCC TCA CA 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ TAC CAG GGT TTG AGC TCA GC 3′ (364 bp); inducible no synthase (iNOS), 5′ primer 5′ TGG GAA TGG AGA CTG TCC CAG 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GGG ATC TGA ATG TGA TGT TTG 3′ (306 bp); MIP-1α, 5′ primer 5′ ATG AAG GTC TCC ACC ACT GCC CTT G 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GGC ATT CAG TCC AGG TCA GTG AT 3′ (276 bp); IFN-γ, 5′ primer 5′ CTT GGA TAT CTG GAG GAA CTG GC 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GCG CTG GAC CTG TGG GTT GTT GA 3′ (271 bp); hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), 5′ primer 5′ GTT GGA TAC AGG CCA GAC TTT GTT G 3′ and 3′ primer 5′ GAG GGT AGG CTG GCC TAT AGG CT 3′ (352 bp).

T-cell proliferation assays and cytokine assays.

CD4+ Th1 T-cell lines specific for TMEV VP270–86 and VP324–37 and for PLP56–70, PLP139–151, and PLP178–191, were derived from lymph nodes removed from SJL/J mice 10 days after priming with a complete Freund's adjuvant emulsion containing 50 μg of the respective peptide and 200 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). The T cells were stimulated in vitro every 3 to 4 weeks with 5 × 106 irradiated syngeneic spleen cells and the respective peptide at 25 μM for every 106 T cells. The T cells were maintained between stimulations in the appropriate medium and used for the T-cell proliferations 14 to 21 days after stimulation. For the T-cell proliferation assays, microglia were cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates (2 × 105 cells per well) and either infected with TMEV for 48 h or stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h. The microglia were washed twice with medium, irradiated, and cultured with 5 × 104 T cells and the appropriate peptide at 10 to 50 μM. The cells were pulsed at 72 h with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine and then harvested and counted at 96 h. Proliferation was determined with triplicate wells for each condition and then expressed as mean counts per minute ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Stimulation indices (SI) were determined by dividing the counts per minute in cultures with added antigen by the counts per minute in wells containing PBS. For cytokine analysis, a duplicate set of proliferation wells was used to collect supernatants at 48 and 72 h. The concentrations of IFN-γ and TNF-α were quantitated with indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Endogen Inc., Woburn, Mass.) with detection limits of ∼100 pg/ml for IFN-γ and ∼50 pg/ml for TNF-α.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of microglia from SJL/J mouse brains.

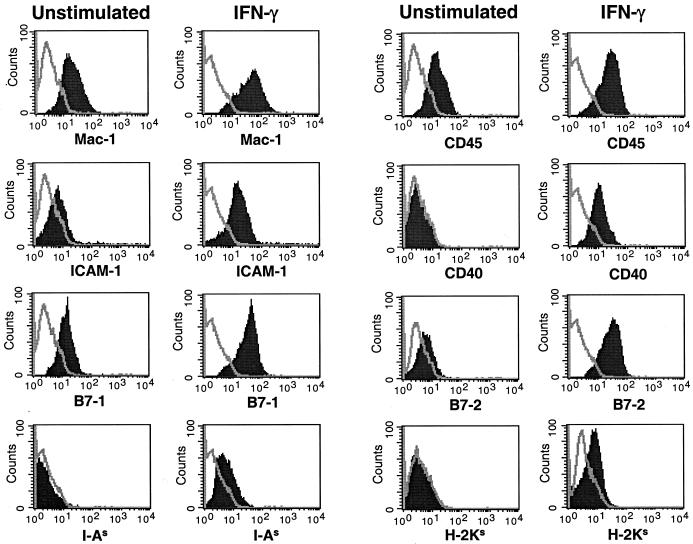

Microglial cells were isolated from the brains of newborn SJL/J mice. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the isolated microglia for the expression of cell surface markers (Fig. 1). These cells failed to express GFAP, B220, or CD11c markers for astrocytes, B cells, and dendritic cells, respectively, indicating lack of contamination of the cultures with blood-derived cells (data not shown). SJL microglia expressed Mac-1 (CD11b) and F4/80 on the cell surface (Fig. 1), similar to splenic peripheral macrophages, but unlike peripheral APCs, they failed to express MHC class II (data not shown). The distinguishing difference between microglia and macrophage populations is the level of CD45 expression on the cell surface (19). Macrophages express high levels of CD45, while microglia express low-to-moderate levels of CD45. Similar to previous reports (6), the isolated microglia population expressed an intermediate level of CD45 (19). The microglia also expressed low levels of B7-1 and almost no B7-2 and ICAM-1 and did not express MHC class I, MHC class II, or CD40. As previous studies have shown that IFN-γ activates microglia (2, 20), we assessed the effects of IFN-γ activation on cell surface antigen expression. IFN-γ-stimulated microglia expressed slightly higher levels of Mac-1 and CD45 than did unstimulated microglia (Fig. 1). However, IFN-γ-stimulated microglia significantly upregulated cell surface expression of the APC-related B7-1, B7-2, ICAM-1, CD40, MHC class I, and MHC class II molecules.

FIG. 1.

Expression of APC surface markers on unstimulated and IFN-γ-treated SJL microglia. Microglia cultures were unstimulated or stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h. The microglia were stained with antibodies for Mac-1 (CD11b), CD45, ICAM-1 (CD54), CD40, B7-1 (CD80), B7-2 (CD86), MHC class II (I-AS), and MHC class I (H-2KS). Surface expression was then analyzed by flow cytometry, with the single line in each histogram representing the isotype antibody control and the solid peak representing the surface marker staining listed on the x axis. The flow plots shown represent all of the cells derived from each of the various culture conditions. These results are representative of four separate experiments.

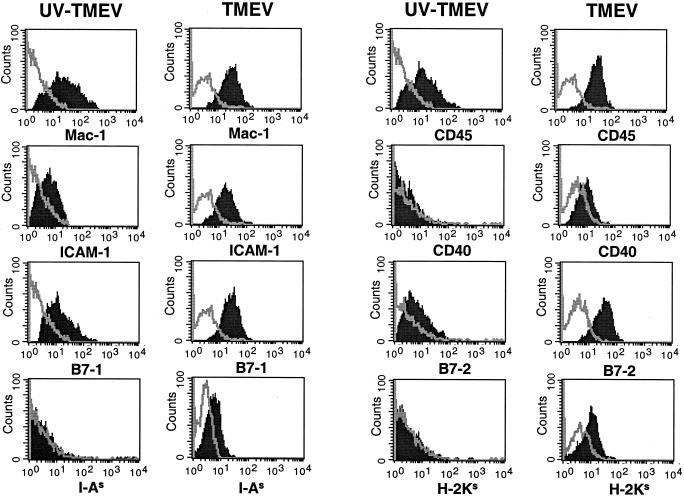

Viral infection stimulates microglial APC surface marker expression.

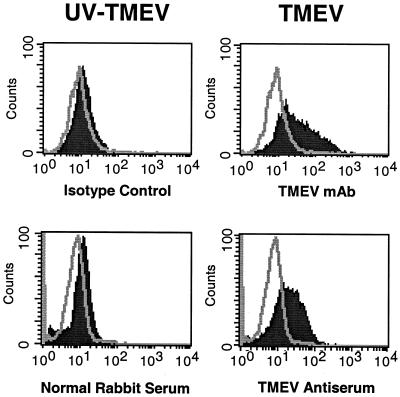

Microglia have previously been suggested to be a major source of persistent virus in the CNS during TMEV infection (9, 40). In addition, brain macrophages can be infected in vitro with the DA strain of TMEV and produce detectable levels of viral RNA and release viral particles (34). We thus asked if TMEV infection of SJL microglia would result in a persistent infection and, if so, what effect the infection would have on the activation state of these cells. SJL microglia were infected for 48 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of viral proteins using two virus-specific antibodies. The infected microglia contained a high level of viral proteins compared to microglia infected with UV-inactivated BeAn (Fig. 2). In addition, no significant loss in the number of microglia was detected (data not shown), suggesting that the virus had no significant cytolytic affect on the microglia compared to other cell types (e.g., BHK-21) which are lysed by the virus within 24 h following infection. Thus, infection of microglia with TMEV resulted in persistent infection of the cells, which could be maintained in culture for 1 to 2 weeks with similar levels of viral proteins, as determined by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). TMEV-infected microglia were next analyzed to determine the effect of virus infection on the expression of APC-related molecules (Fig. 3). TMEV-infected microglia upregulated the cell surface expression of B7-1, B7-2, ICAM-1, CD40, MHC class I, and MHC class II compared to microglia incubated with UV-inactivated TMEV-uninfected microglia. With the exception of that of CD40, expression levels of the various molecules in virus-infected microglia were similar to the levels induced by stimulation with IFN-γ (Fig. 1). Thus, TMEV infection, similar to activation with IFN-γ, leads to microglial activation and expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules required for antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 2.

SJL mouse microglia can be persistently infected with viable TMEV. Microglia were infected for 48 h with either viable or UV-inactivated strain BeAn of TMEV and then stained with an anti-VP3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or polyclonal antiserum raised against TMEV (supplied by Robert Fujinami). The single line in each histogram represents the isotype antibody control. The solid peak in each histogram represents anti-TMEV staining.

FIG. 3.

SJL microglia infected with TMEV upregulate expression of APC surface markers. Microglia were infected for 48 h with the BeAn strain of TMEV and then stained with antibodies for Mac-1, CD45, ICAM-1, CD40, B7-1, B7-2, MHC class II, and MHC class I. The single line in each histogram represents the isotype antibody control. The solid peak in each histogram represents the specific antibody staining for the surface markers listed on the x axis. These results are representative of four separate experiments.

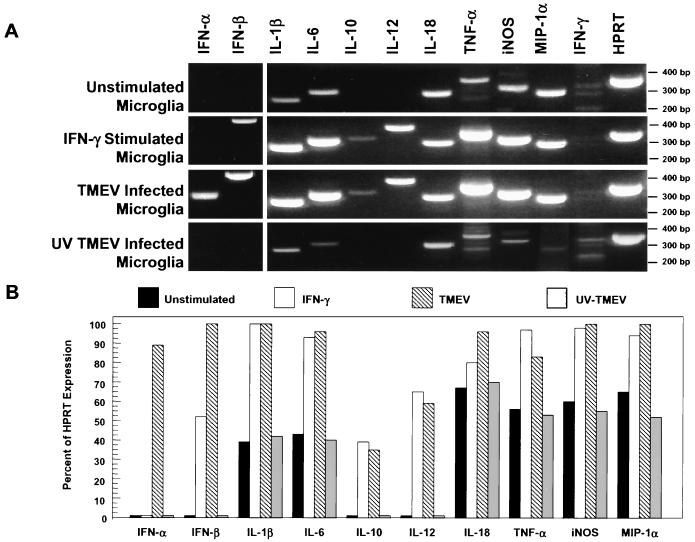

TMEV-infected microglia express cytokines involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses.

IFN-γ and TMEV-infected microglia were next compared for the ability to express critical cytokines and chemokines, which may direct the migration and activation of CNS inflammatory cells. Recent reports have shown that multiple cytokines are secreted during the innate immune response to infectious agents, and these cytokines not only direct the innate immune response but also determine the nature of the ensuing adaptive immune response (42). TMEV is a picornavirus and thus contains a positive-sense RNA genome. It is well established that double-stranded RNA can act as a “molecular pattern” recognized by “pattern recognition molecules” of the innate immune system (25). Activation of these molecules by double-stranded RNA results in cytokine expression, most importantly type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β. Therefore, expression of multiple chemokines, cytokines, and inflammatory effector molecules was analyzed by RT-PCR methods. mRNA was isolated from microglia cultured with no additions, cultured with IFN-γ, or infected with viable or UV-inactivated TMEV (Fig. 4). The levels of expression were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene for HPRT. Unstimulated microglia expressed low levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α, iNOS, and MIP1-α and failed to express IL-10 or IL-12 p40. Microglia stimulated with IFN-γ upregulated the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α, iNOS, and MIP1-α mRNAs. IFN-γ-stimulated microglia also expressed low levels of IFN-β and IL-10 and a moderate level of IL-12 p40 mRNA. Interestingly, microglia infected with viable, but not with UV-inactivated, TMEV also upregulated the expression of high levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α, iNOS, and MIP1-α mRNAs and low-to-moderate levels of IL-10 and IL-12 p40. As expected, neither unstimulated nor stimulated microglia expressed detectable levels of the IFN-γ message. The light bands in the IFN-γ gel lanes (Fig. 4) are nonspecific bands and do not correspond to the 271-bp size expected for IFN-γ. Therefore, TMEV infection of microglia resulted in upregulated expression of multiple cytokines critical for initiating and controlling the innate immune response, as well as in triggering of the adaptive immune response. Persistently infected microglia also expressed a relevant chemokine (MIP-1α) involved in T-cell trafficking to the CNS and inflammatory effector molecules (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS) which are important in the innate and adaptive immune responses in the CNS.

FIG. 4.

Induction of cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression by IFN-γ-treated and TMEV-infected SJL mouse microglia. RNA were isolated from unstimulated microglia, from microglia stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h, and from microglia infected with viable or UV inactivated TMEV 48 h previously for time periods determined in preliminary experiments to be optimal for gene expression. The RNA for each microglia group was then analyzed by RT-PCR to determine IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, TNF-α, iNOS, MIP-1α, IFN-γ, and HPRT mRNA expression levels. The products were separated on a 2% agarose gel and then analyzed for expression of the various cytokines relative to the HPRT expression levels (A). Similar results were observed in 10 separate experiments. (B) The mRNA levels for the various molecules are presented as percentages of the expression of HPRT based on densitometric scanning.

Virus-infected microglia can process and present myelin protein epitopes.

During acute TMEV infection of SJL mice, macrophage-microglia-mediated bystander damage to myelin results in the phagocytosis and processing of myelin debris by these mononuclear cells (31). Previous reports from our laboratory have shown that CD45+ APCs isolated from the CNSs of TMEV-infected mice present various myelin basic protein, PLP, and MOG peptides during the ongoing demyelinating disease (31, 52). As a result, epitope spreading is initiated wherein CD4+ T-cell responses to the immunodominant PLP139–151 epitope are initiated approximately 3 weeks after the onset of clinical disease and responses to additional myelin epitopes (MOG92–106, PLP56–70, and PLP178–191) develop as the disease progresses (47). Thus, microglia, particularly those infected with TMEV or activated by IFN-γ, may play a critical role in the processing and presentation of myelin epitopes to CNS-infiltrating CD4+ T cells during chronic autoimmune demyelinating diseases. The current results indicate that TMEV-infected microglia upregulate MHC class II and costimulatory molecules (B7-1, B7-2, and CD40). We thus compared the abilities of unstimulated and stimulated microglia to process and present myelin protein epitopes to specific Th1 cells.

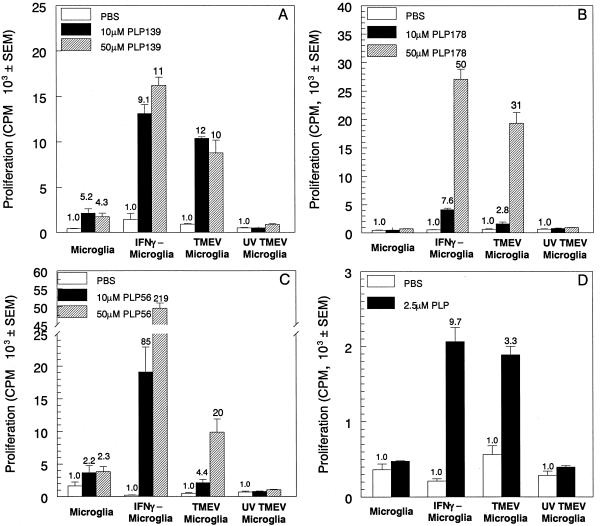

The microglia were analyzed by using T-cell proliferation assays to determine their ability to present PLP peptides to specific CD4+ T-cell lines. Unstimulated microglia were unable to effectively present PLP139–151 (Fig. 5A), PLP178–191 (Fig. 5B), or PLP56–70 (Fig. 5C) to induce proliferation of specific Th1 lines. However, microglia stimulated with IFN-γ induced significant activation of T-cell lines specific for each of these epitopes. TMEV-infected microglia also effectively presented these epitopes in comparison to control cells infected with UV-inactivated TMEV. It should be stressed that professional APCs (i.e., splenic macrophages) were more efficient in presenting PLP peptides than either IFN-γ-stimulated or TMEV-infected microglia with SI two- to threefold higher than the SI of microglia (data not shown). The microglia were further analyzed for the ability to process PLP139–151 from intact PLP and present the peptide to PLP139–151-specific T cells. IFN-γ-stimulated and TMEV-infected microglia were able to process and present PLP139–151 from intact PLP to PLP139–151 CD4+ T cells, while unstimulated and UV-inactivated TMEV-infected microglia were ineffective (Fig. 5D). Similar results were obtained when microglia were analyzed for the ability to process and present PLP178–191 and PLP56–70 peptides from intact PLP (data not shown). Therefore, TMEV infection of microglia conferred an antigen-presenting function on these cells, indicating their potential importance in presenting endogenous myelin peptides during chronic demyelinating diseases.

FIG. 5.

Activated microglia process and present myelin epitopes to initiate proliferation in CD4+ Th1 lines. Microglia were unstimulated, stimulated for 24 h with IFN-γ, or infected for 48 h with viable or UV-inactivated TMEV. The cells were cultured with various concentrations of PLP139–151 (A), PLP178–191 (B), or PLP56–70 (C) and the corresponding specific T-cell lines for 96 h. Alternatively, microglia were cultured with whole PLP protein and PLP139–151-specific T cells (D). T-cell proliferation was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation during the last 24 h of the assay. Proliferation is expressed as mean counts per minute ± the SEM, and the SI is listed above each bar. These results are representative of five separate experiments.

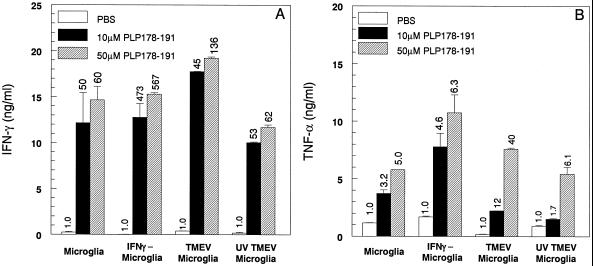

The abilities of the various microglial populations to activate proinflammatory cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF-α) production by the PLP peptide-specific Th1 lines were also assessed. Interestingly, PLP178–191-pulsed, unstimulated microglia induced the secretion of moderate levels of both IFN-γ (Fig. 6A) and TNF-α (Fig. 6B) from the PLP178–191-specific T-cell line, despite the fact that the Th1 cells in these cultures failed to proliferate (Fig. 5B). IFN-γ secretion was observed in T cells cocultured with unstimulated, IFN-γ-stimulated, and TMEV-infected microglia (Fig. 6A), despite the differential abilities of these microglial populations to induce proliferation, indicating that IFN-γ secretion is independent of T-cell proliferation. In contrast, although unstimulated microglia also induced the production of moderate amounts of TNF-α, its production was higher when the T-cell lines were activated with IFN-γ-stimulated microglia or microglia infected with viable TMEV (Fig. 6B). Similar proinflammatory cytokine expression patterns were also observed when T-cell lines specific for PLP139–151 and PLP56–70 were used (data not shown). Consistent with their failure to induce proliferation, unstimulated microglia and those infected with UV-inactivated TMEV failed to induce IL-2 production from the myelin-specific Th1 lines (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that both naive and activated microglia can support the production of proinflammatory cytokines from myelin-specific Th1 cells.

FIG. 6.

Both resting and activated microglia induce proinflammatory cytokine secretion from PLP178–191-specific Th1 cells. Culture supernatants were collected at 48 h from the PLP178–191-specific T-cell proliferation assay (Fig. 5B). The supernatants were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for IFN-γ (A) and TNF-α (B). Secretion of each cytokine was determined for the differing peptide concentrations listed and expressed as nanograms per milliliter. The values above the bars indicate the fold increases in cytokine expression over that of the PBS control (1.0). These experiments were performed five times, and the results of one representative experiment are shown.

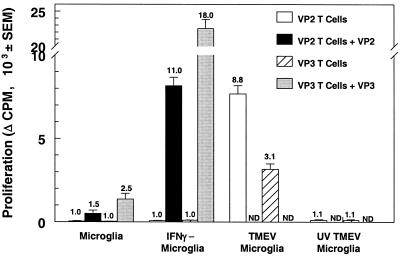

Microglia infected with strain BeAn can process and present endogenous viral antigens.

Since TMEV establishes a persistent infection of microglia in the CNS, it was of interest to determine if microglia persistently infected with TMEV could process and present viral antigens from the infecting virus. Thus, microglia were infected with the strain BeAn virus or the UV-inactivated strain BeAn virus and then cultured with T cells specific for the immunodominant viral protein epitopes VP270–86 (21) and VP324–37 (69) in an antigen presentation assay (Fig. 7). As anticipated, activation of the VP2- and VP3-specific T cells was significantly enhanced when the peptide was presented by IFN-γ-stimulated microglia rather than by unstimulated cells. Most interestingly, TMEV-infected microglia activated the proliferation of both lines in the absence of added peptide while UV-inactivated TMEV-infected microglia did not activate the proliferation of these virus-specific T-cell lines. Therefore, TMEV-infected microglia can process and present viral epitopes from the infecting virus to CD4+ T cells, indicating that the virus peptides can access the MHC class II processing-presentation pathway. This was confirmed by showing that proliferation of the VP2- and VP3-specific T-cell lines could be inhibited by the addition of anti-I-As monoclonal antibody MK-S4 to the culture (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Virus-infected microglia process and present endogenous viral antigens to CD4+ T cells. Microglia were unstimulated, stimulated for 24 h with IFN-γ, or infected for 48 h with viable TMEV or UV-inactivated TMEV, irradiated, and incubated with T cells specific for immunodominant TMEV capsid protein epitope VP270–86 or VP324–37 for 96 h in the presence or absence of the specific VP peptide. T-cell proliferation was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation during the last 24 h of the assay. Viral peptides were not added to the virus-infected microglia (ND). Proliferation is expressed as the mean change in counts per minute ± the SEM, where the background of wells containing PBS for each group was subtracted from the experimental wells, and the SI is listed above each bar. These data are representative of three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here show that microglia from SJL/J mice can be persistently infected in vitro with TMEV and that, as a result of this infection, these cells are activated to function as competent APCs with the ability to process and present both virus and myelin epitopes to memory CD4+ Th1 cells. Concomitant with the acquisition of this functional antigen presentation capacity, TMEV infection induced the upregulation of cytokines involved in innate immune responses and of cytokines and costimulatory molecules required for the activation and differentiation Th1 effector cells. Most significantly, direct TMEV infection of microglia was nearly as effective as stimulation with high levels of IFN-γ in conferring APC function.

TMEV-IDD is a well-characterized CD4+ T-cell-mediated model of MS (44). Life-long persistent viral infection of CNS-resident microglia, macrophages, and astrocytes (9, 39, 40) is directly related to the development of the chronic demyelinating disease (8). Initial myelin damage is mediated by a bystander mechanism wherein the primary effector cells are mononuclear phagocytes (microglia-macrophages) activated by inflammatory cytokines produced from TMEV-specific Th1 cells responding to viral epitopes that persist in the CNS (29, 45, 46). Early myelin destruction leads to the de novo activation of myelin-specific T cells. The initial myelin response is directed toward the immunodominant PLP139–151 epitope (47), and epitope spreading then leads to an ordered progression of T-cell responses to multiple myelin autoepitopes which appear to play a significant role in the chronic phase of the disease by escalating the demyelinating process (31).

TMEV infection of microglia led to the rapid upregulation of mRNA for multiple cytokines involved in mediating both innate and adaptive immune responses (Fig. 3). Cytokines produced by the innate immune response have a critical role in shaping the ensuing adaptive immune responses, as well as other innate immune responses (42). The innate immune response recognizes invading pathogens by differentiating self from non-self by using pattern recognition receptors which recognize pathogen-expressed molecular arrays or patterns (43). Much attention has recently focused on the initiation of innate immune responses to bacterial infections through the mammalian Toll-like receptors, but it has long been recognized that type I interferons, IFN-α and IFN-β, are produced in response to double-stranded RNA (25). Double-stranded RNA is commonly found in the replication cycles of multiple viruses, including TMEV, but is not found in mammalian cells (42). Type I interferons are best known for preventing viral infection, but IFN-α and IFN-β also elicit the secretion of IFN-γ by natural killer cells and T cells, which promotes Th1 responses (10).

Via the production of cytokines and chemokines, the innate immune response can signal the development of an inflammatory response, can function in activating various Th subsets through the upregulation of MHC molecule expression and regulation of costimulatory molecules, and can control the induction of inflammatory effector functions (42). TMEV-infected microglia induced new expression of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-10, and IL-12 and significantly upregulated the basal expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α, iNOS, and MIP-1α (Fig. 4). Expression of type 1 interferons, IFN-α and IFN-β, induced by double-stranded RNA, can regulate the innate response through transcriptional control of the expression of several cytokines and APC surface markers. Viral RNA can induce the expression of cytokines-chemokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and MIP1-α, which direct the inflammatory response by controlling the migration of T cells to the site of infection (28, 49, 54, 57, 64).

TMEV infection of microglia also resulted in upregulation of the expression of TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-18, which contribute to the activation and differentiation of proinflammatory Th1 T cells (5, 27). In addition, TMEV-infected microglia upregulated the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules necessary for Th1 expansion. The innate response has been shown to upregulate MHC class I and class II on the surface of APCs through control of transcriptional regulators (42, 56). Double-stranded RNA has also been shown to induce the expression of the B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules and of other costimulatory molecules (ICAM-1 and CD40) that contribute to T-cell activation (22, 25).

TMEV infection of microglia also led to the upregulation of various genes, e.g., that for TNF-α, whose products have been implicated in the effector stages of the demyelination process (55). Expression of iNOS results in the production of NO, which regulates the production of various cytokines at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Activation of microglia by IFN-α and IFN-β-dependent processes following intracellular microbial infections and by CD40-CD40 ligand interactions can upregulate the production of effector inflammatory mediators, e.g., NO and matrix metalloproteinases (41, 61), which aggravate inflammatory processes (16, 53, 63). Thus, microglia-macrophages activated directly by TMEV infection may also contribute to the effector phase of myelin destruction (12).

It is of great interest to determine whether the autoreactive Th1 cells induced via epitope spreading are activated locally in the CNS and/or in the peripheral lymphoid organs and to determine which APC populations (CNS resident and/or peripheral) present endogenous myelin peptides. The CNS contains several cell types which may serve as APCs—microglia, astrocytes, and cerebrovascular endothelial cells (1, 48, 60, 68). In support of the possibility that microglia, either activated directly by TMEV infection or via Th1-derived IFN-γ, may present endogenous myelin epitopes in TMEV-infected mice, previous studies have determined that microglia-macrophages in the CNSs of TMEV-infected SJL mice contain infectious virus (9, 40) and ingested myelin debris (31). We have also shown that the majority of F4/80+ macrophages-microglia isolated from the spinal cords of mice with ongoing TMEV-induced demyelinating disease coexpress high levels of MHC class II as well as B7-1 and B7-2, and that these cells endogenously present both virus and self myelin epitopes to specific Th1 lines (30, 31, 52). However, these studies were unable to differentiate microglia from CNS-infiltrating macrophages to determine their individual roles in viral and myelin immune responses. The present results demonstrate that viral infection of isolated microglial cells can directly induce upregulation of MHC classes I and II, necessary for T-cell receptor signaling, as well as a variety of costimulatory molecules (B7-1, B7-2, CD40, and ICAM-1) (Fig. 3) required for the activation of both naive and memory Th1 cells (26). Critically, the current results demonstrate that TMEV-infected microglia were able to process and present endogenous viral epitopes from the infecting virus (Fig. 7) and various PLP epitopes (Fig. 5 and 6) to antigen-specific Th1 cells, indicating that microglia may play a critical role both in the initiation of myelin destruction via activation of TMEV-specific T cells and in epitope spreading via activation of myelin epitope-specific T cells (30, 31). Our results also confirm an earlier report on microglia isolated from normal adult brain (7) by showing that unstimulated cells are unable to activate the proliferation of Th1 clones (Fig. 5) but are able to induce proinflammatory cytokine production (Fig. 6) in spite of the minimal endogenous expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules.

In summary, the current in vitro analysis demonstrates that persistent infection of microglia with TMEV induces potent activation of the innate immune response. The consequences of this activation have important implications for the initial inflammatory response, the ensuing adaptive immune response, and the effector mechanisms involved in myelin destruction in TMEV-IDD. Early expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the CNSs of infected mice leads to the initial infiltration of peripherally activated virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Activated microglia which have upregulated MHC class II and costimulatory molecules can then induce the further activation of these T cells, triggering the production of Th1-derived proinflammatory chemokines-cytokines, including IFN-γ, which would lead to the further influx and activation of peripheral monocytes-macrophages. Activated microglia can then induce myelin destruction via the secretion of effector molecules (e.g., TNF-α and NO), resulting in the uptake, processing, and presentation of ingested endogenous myelin epitopes. In turn, this would lead to the local activation of myelin-specific autoreactive T cells, which play a major role in chronic disease progression by perpetuating the chronic inflammatory process (47). Collectively, our results suggest that microglia may provide the first response to invading viruses through an innate immune response and subsequently direct the development of the adaptive immune response in the CNS initially to the invading pathogen and subsequently to tissue-specific autoantigens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by USPHS NIH grants NS23349, NS40460, and NS30871. J.K.O. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Spinal Cord Research Foundation (2046-01) and the NIH (F32 NS-10893). A.M.G. was supported by NIH training grant T32 AI-07476.

We thank Carol L. Vanderlugt for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aloisi F, Ria F, Adorini L. Regulation of T-cell responses by CNS antigen-presenting cells: different roles for microglia and astrocytes. Immunol Today. 2000;21:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01512-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloisi F, Ria F, Penna G, Adorini L. Microglia are more efficient than astrocytes in antigen processing and in Th1 but not Th2 activation. J Immunol. 1998;160:4671–4680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barron K D. Comparative observations on the cytological reactions of central and peripheral nerve cells to axotomy. In: Kao C C, Bunge R P, Reier P J, editors. Spinal cord reconstruction. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard C C, de Rosbo N K. Immunopathological recognition of autoantigens in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. 1991;13:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biron C A, Nguyen K B, Pien G C, Cousens L P, Salazar-Mather T P. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson M J, Reilly C R, Sutcliffe J G, Lo D. Mature microglia resemble immature antigen-presenting cells. Glia. 1998;22:72–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199801)22:1<72::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carson M J, Sutcliffe J G, Campbell I L. Microglia stimulate naive T-cell differentiation without stimulating T-cell proliferation. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:127–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990101)55:1<127::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clatch R J, Lipton H L, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. II. Survey of host immune responses and central nervous system virus titers in inbred mouse strains. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:327–337. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clatch R J, Miller S D, Metzner R, Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Monocytes/macrophages isolated from the mouse central nervous system contain infectious Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) Virology. 1990;176:244–254. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90249-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousens L P, Peterson R, Hsu S, Dorner A, Altman J D, Ahmed R, Biron C A. Two roads diverged: interferon alpha/beta and interleukin 12-mediated pathways in promoting T cell interferon gamma responses during viral infection. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1315–1328. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal Canto M C, Barbano R L. Immunocytochemical localization of MAG, MBP and P0 protein in acute and relapsing demyelinating lesions of Theiler's virus infection. J Neuroimmunol. 1985;10:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(85)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Primary demyelination in Theiler's virus infection. An ultrastructural study. Lab Investig. 1975;33:626–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Ultrastructural immunohistochemical localization of virus in acute and chronic demyelinating Theiler's virus infection. Am J Pathol. 1982;106:20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Rosbo N K, Hoffman M, Mendel I, Yust I, Kaye J, Bakimer R, Flechter S, Abramsky O, Milo R, Karni A, Ben-Nun A. Predominance of the autoimmune response to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) in multiple sclerosis: reactivity to the extracellular domain of MOG is directed against three main regions. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3059–3069. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhib-Jalbut S, Xia J, Rangaviggula H, Fang Y Y, Lee T. Failure of measles virus to activate nuclear factor-kappa B in neuronal cells: implications on the immune response to viral infections in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 1999;162:4024–4029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diefenbach A, Schindler H, Donhauser N, Lorenz E, Laskay T, MacMicking J, Rollinghoff M, Gresser I, Bogdan C. Type 1 interferon (IFNalpha/beta) and type 2 nitric oxide synthase regulate the innate immune response to a protozoan parasite. Immunity. 1998;8:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards J A, Denis F, Talbot P J. Activation of glial cells by human coronavirus OC43 infection. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;108:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(00)00266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federoff S. Development of microglia. In: Kettenmann H, Ransom B R, editors. Neuroglia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford A L, Goodsall A L, Hickey W F, Sedgwick J D. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. J Immunol. 1995;154:4309–4321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frei K, Siepl C, Groscurth P, Bodmer S, Schwerdel C, Fontana A. Antigen presentation and tumor cytotoxicity by interferon-gamma-treated microglial cells. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1271–1278. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerety S J, Karpus W J, Cubbon A R, Goswami R G, Rundell M K, Peterson J D, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. V. Mapping of a dominant immunopathologic VP2 T cell epitope in susceptible SJL/J mice. J Immunol. 1994;152:908–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. The role of CD40 ligand in costimulation and T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:85–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampson D R, Poduslo S E. Purification of proteolipid protein and production of specific antiserum. J Neuroimmunol. 1986;11:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(86)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harry G J, Billingsley M, Bruinink A, Campbell I L, Classen W, Dorman D C, Galli C, Ray D, Smith R A, Tilson H A. In vitro techniques for the assessment of neurotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl. 1):131–158. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann J A, Kafatos F C, Janeway C A, Ezekowitz R A. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science. 1999;284:1313–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.June C H, Bluestone J A, Nadler L M, Thompson C B. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol Today. 1994;15:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanakaraj P, Ngo K, Wu Y, Angulo A, Ghazal P, Harris C A, Siekierka J J, Peterson P A, Fung-Leung W P. Defective interleukin (IL)-18-mediated natural killer and T helper cell type 1 responses in IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1129–1138. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karpus W J, Lukacs N W, McRae B L, Streiter R M, Kunkel S L, Miller S D. An important role for the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha in the pathogenesis of the T cell-mediated autoimmune disease, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1995;155:5003–5010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karpus W J, Pope J G, Peterson J D, Dal Canto M C, Miller S D. Inhibition of Theiler's virus-mediated demyelination by peripheral immune tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1995;155:947–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz-Levy Y, Neville K L, Girvin A M, Vanderlugt C L, Pope J G, Tan L J, Miller S D. Endogenous presentation of self myelin epitopes by CNS-resident APCs in Theiler's virus-infected mice. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:599–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz-Levy Y, Neville K L, Padilla J, Rahbe S M, Begolka W S, Girvin A M, Olson J K, Vanderlugt C L, Miller S D. Temporal development of autoreactive Th1 responses and endogenous antigen presentation of self myelin epitopes by CNS-resident APCs in Theiler's virus-infected mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:5304–5314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreutzberg G W. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:312–318. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtzke J F. Epidemiologic evidence for multiple sclerosis as an infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:382–427. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy M, Aubert C, Brahic M. Theiler's virus replication in brain macrophages cultured in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:3188–3193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3188-3193.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Cuzner M L, Newcombe J. Microglia-derived macrophages in early multiple sclerosis plaques. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1996;22:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling E A, Penney D, Leblond C P. Use of carbon labeling to demonstrate the role of blood monocytes as precursors of the ‘ameboid cells’ present in the corpus callosum of postnatal rats. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:631–657. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipton H L, Dal Canto M C. Susceptibility of inbred mice to chronic central nervous system infection by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. Infect Immun. 1979;26:369–374. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.1.369-374.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipton H L, Friedmann A. Purification of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus and analysis of the structural virion polypeptides: correlation of the polypeptide profile with virulence. J Virol. 1980;33:1165–1172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1165-1172.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipton H L, Kratochvil J, Sethi P, Dal Canto M C. Theiler's virus antigen detected in mouse spinal cord 2 1/2 years after infection. Neurology. 1984;34:1117–1119. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.8.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipton H L, Twaddle G, Jelachich M L. The predominant virus antigen burden is present in macrophages in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol. 1995;69:2525–2533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2525-2533.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik N, Greenfield B W, Wahl A F, Kiener P A. Activation of human monocytes through CD40 induces matrix metalloproteinases. J Immunol. 1996;156:3952–3960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzhitov R, Janeway C A., Jr Innate immunity: impact on the adaptive immune response. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medzhitov R, Janeway C A., Jr Innate immunity: the virtues of a nonclonal system of recognition. Cell. 1997;91:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller S D, Gerety S J. Immunologic aspects of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. Semin Virol. 1990;1:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller S D, Gerety S J, Kennedy M K, Peterson J D, Trotter J L, Tuohy V K, Waltenbaugh C, Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. III. Failure of neuroantigen-specific immune tolerance to affect the clinical course of demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;26:9–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller S D, Karpus W J. The immunopathogenesis and regulation of T-cell mediated demyelinating diseases. Immunol Today. 1994;15:356–361. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller S D, Vanderlugt C L, Begolka W S, Pao W, Yauch R L, Neville K L, Katz-Levy Y, Carrizosa A, Kim B S. Persistent infection with Theiler's virus leads to CNS autoimmunity via epitope spreading. Nat Med. 1997;3:1133–1136. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikcevich K M, Gordon K B, Tan L, Hurst S D, Kroepfl J F, Gardinier M, Barrett T A, Miller S D. Interferon-gamma activated primary murine astrocytes express B7 costimulatory molecules and prime naive antigen-specific T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:614–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Garra A, Steinman L, Gijbels K. CD4+ T-cell subsets in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:872–883. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ota K, Matsui M, Milford E L, Mackin G A, Weiner H L, Hafler D A. T-cell recognition of an immunodominant myelin basic protein epitope in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 1990;346:183–187. doi: 10.1038/346183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perry V H, Andersson P B, Gordon S. Macrophages and inflammation in the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:268–273. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90180-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pope J G, Vanderlugt C L, Lipton H L, Rahbe S M, Miller S D. Characterization of and functional antigen presentation by central nervous system mononuclear cells from mice infected with Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1998;72:7762–7771. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7762-7771.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reiss C S, Komatsu T. Does nitric oxide play a critical role in viral infections? J Virol. 1998;72:4547–4551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4547-4551.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sedgwick J D, Riminton D S, Cyster J G, Korner H. Tumor necrosis factor: a master-regulator of leukocyte movement. Immunol Today. 2000;21:110–113. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selmaj K, Raine C S. Tumor necrosis factor mediates myelin and oligodendrocyte damage in vitro. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:339–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sen G C, Lengyel P. The interferon system. A bird's eye view of its biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5017–5020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimizu Y, Newman W, Tanaka Y, Shaw S. Lymphocyte interactions with endothelial cells. Immunol Today. 1992;13:106–112. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90151-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shrikant P, Benveniste E N. The central nervous system as an immunocompetent organ: role of glial cells in antigen presentation. J Immunol. 1996;157:1819–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Streit W. Microglia. In: Kettenmann H, Ransom B R, editors. Neuroglia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan L J, Gordon K B, Mueller J P, Matis L A, Miller S D. Presentation of proteolipid protein epitopes and B7–1-dependent activation of encephalitogenic T cells by IFN-gamma-activated SJL/J astrocytes. J Immunol. 1998;160:4271–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian L, Noelle R J, Lawrence D A. Activated T cells enhance nitric oxide production by murine splenic macrophages through gp39 and LFA-1. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:306–309. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Traugott U, Reinherz E L, Raine C S. Multiple sclerosis: distribution of T cell subsets and Ia- positive macrophages in lesions of different ages. J Neuroimmunol. 1983;4:201–221. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(83)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Veen R C, Hinton D R, Incardonna F, Hofman F M. Extensive peroxynitrite activity during progressive stages of central nervous system inflammation. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;77:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walker W S, Gatewood J, Olivas E, Askew D, Havenith C E. Mouse microglial cell lines differing in constitutive and interferon-gamma-inducible antigen-presenting activities for naive and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;63:163–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weissenbock H, Hornig M, Hickey W F, Lipkin W I. Microglial activation and neuronal apoptosis in Bornavirus infected neonatal Lewis rats. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:260–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wekerle H. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis as a model of immune-mediated CNS disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1993;3:779–784. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90153-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao B G, Link H. Is there a balance between microglia and astrocytes in regulating Th1/Th2-cell responses and neuropathologies? Immunol Today. 1999;20:477–479. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yauch R L, Kerekes K, Saujani K, Kim B S. Identification of a major T-cell epitope within VP3(24–37) of Theiler's virus in demyelination-susceptible SJL/J mice. J Virol. 1995;69:7315–7318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7315-7318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]