Abstract

An unusually projecting human ear is known as a prominent ear, otapostasis, or bat ear. It might be both bilateral and unilateral. The scapha and antihelix of the big concha are not well formed. It is the outcome of cartilage deformity that occurred during early ear development in utero. After the child reaches five years old, the abnormality can be corrected at any time. In order to prevent psychological suffering, the procedure should ideally be performed as soon as possible. Otoplasty correction is reshaping the ear cartilage to bring the ear closer to the side of the head. The cartilage is reshaped, but the skin is left in place. Hearing remains unaffected by the operation. It is mainly done for aesthetic reasons. Although they are uncommon, the post-operative consequences from the operation include hematoma development, keloid formation, infection, and asymmetry in the ears. Otoplasty is a cosmetic operation that involves permanent sutures to alter the size, shape, or location of the ear. The main purpose of otoplasty is to treat promin auris, or bulging ears. Promin auris, the principal indication for otoplasty, is the subject of this review. The indications, contraindications, and method utilized in otoplasty are reviewed in this exercise, which also emphasizes the need of pre- and post-operative care for patients having this surgery. Otoplasty results are generally lifelong and will improve the self-confidence. The goals of otoplasties are to make the ears appear more natural in comparison to the head and help with the overall contour of the ears. Final ear surgery results will be visible after a two week recovery period, with small improvements appearing for up to 12 months post-procedure. A proper understanding of the diagnosis, indications, and surgical techniques will lead to positive outcomes in otoplasty.

Keywords: Bat ear, Prominent ear, Otapostasis, Otoplasty

Introduction

The auricle is composed of a fibroelastic cartilage enveloped in its perichondrium. A layer of loose areolar connective tissue separates the auricle’s skin from the posterior perichondrium, which is adhering to the perichondrium at its anterior surface. Helix, antihelix, tragus, antitragus, concha (cymba and cavum), and the ear lobe are the six main anatomical components that make up an auricle [1].

Experience has shown that a significant number of parents who bring their kids in for noticeable ear corrections do so primarily to protect their kids from the humiliation and bullying they experienced. After their kid has had surgery, parents may decide to have an otoplasty. Satisfaction and a sense of relief are consistent aspects of their recuperation in these situations [2].

Whether to operate based on the parents’ worries or to wait till the kid expresses them, these questions are crucial to consider when determining whether it is suitable to schedule the operation. Case-by-case consideration is required while making this decision. In spite of the fact that the teasing hasn’t yet begun to negatively impact the children’s self-esteem, by the time they get close to five years old, they could have experienced bullying. They say they’re willing to get the operation done in order to stop the taunting after the conversation [3, 4].

Younger children, those under the age of five, rarely have the self-awareness to recognize when remarks about their looks or behavior indicate that surgery is necessary. Experience has also shown that these younger kids could struggle a lot to comply with the postoperative instructions (i.e., dressings and activity limits). When combined, the lowest possible patient age is five years old, with very few exceptions [5, 6].

Macgregor describes in a 1978 piece the “exquisite cruelty of young children towards the child who happens to look ‘different.‘” These young patients are very cooperative and driven. A perfectly executed otoplasty usually results in a psychological reaction that is genuinely satisfying. These kids don’t expect their otoplasties to be flawless, but the surgeon needs to be mindful that sometimes a parent or other carer has high standards. It is necessary to have an open dialogue regarding the procedure, its potential outcomes, potential side effects, and the dangers associated with anesthesia and surgery. Many adult and adolescent patients report having been embarrassed by their large ears since they were young, but their circumstances have prevented them from having corrective surgery. Additionally, many individuals probably feel quite delighted with the outcomes of surgery [7, 8].

Subtle instances of ear prominence, asymmetry, or shape distortion might not prompt a child to seek correction until they are older, more self-conscious of their appearance, or ready to try a new look that includes wearing their hair back or chopped short. In every instance, the ear or ears that were concealed are now visible [9, 10].

Assessing the patient for an otoplasty involves first identifying the anatomical reasons for the ear protrusion. A conchoscaphal angle greater than 90°, conchal hypertrophy or excess (upper pole, lower pole, or both), inadequate formation of the antihelical fold (the root, superior crus, inferior crus, or all), and a combination of conchal hypertrophy and underdeveloped antihelical fold are the most common causes of protrusion of the external ear [11].

A prominent tipped upper auricular pole, protrusion of the lower auricular pole (cauda helicis, lobule, and cavum concha), and prominence of the mastoid process are contributing features that accentuate auricular protrusion. Ear position and prominence can be greatly impacted by cranial deformity, such as in uncorrected positional plagiocephaly [12].

Auricular protrusion may be one element of a more complex auricular deformity such as a constricted ear, Stahl ear (third crus), macrotia, or syndromic facial deformity [13].

Three points are used to assess auricular protrusion: the level of the inferior helical rim, the postlateral projection point of the mid-auricle, and the most superior aspect of the rim. For such points, the average measurements are 10–12 mm, 20–22 mm, and 16–18 mm, in that order. The auricular protrusion at the UL (upper level), ML (middle level), and LL (lower level) is demonstrated by means of the three lines [14].

Otoplasty has very few contraindications. Surgery is appropriate and very well tolerated in the pediatric population, as long as the child does not strongly object to the idea of having surgery. Delaying surgery until the child expressly requests it is the best course of action if the child starts to misbehave or shows signs of being overly anxious about even visiting the doctor for a preoperative consultation or going to the hospital. A history of undiagnosed and untreated chronic ear infections and drainage is another contraindication. Children who have had a myringotomy or pressure equalizer (PE) tube inserted in the past are not unusual. Otoplasty can be safely performed if there is no significant drainage or active infection [15].

Patients, parents, and/or carers should be made aware of any asymmetrical features of the ears, and a distinction should be made between those that are likely to improve with surgery and those that will remain the same. There is no doubt that the patient, family, and friends’ postoperative assessment of the otoplasty is more thorough than any preoperative assessment [16].

The algorithm might take racial and cultural factors into account. Celtic people are known for having prominent ears, and in Japan, it is believed that having prominent ears indicates intelligence. Children, however, typically adapt to the cultural norms of their adopted nation quite quickly [17].

The generally accepted goals of otoplasty have been well described and include decreasing the prominence and protrusion of the ear, producing an antihelical fold, and superior crus of absent or effaced and making the lobule proportionate to the rest of the ear [18].

Furthermore, all surgical methods must allow for symmetry and restore the natural appearance of the auricle, avoiding the appearance of pinned ears. Variations on the Masturde, Furnas, and Stenstrom cartilage scoring techniques are popular methods [19].

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

In this study, all procedures involving human participants followed the institutional research editorial boards’ ethical standards, the1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards. Damietta faculty of medicine IRB_ Al Azhar university- (IRB00012367). Registration number (IRB00012367-23-11-001).

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study.

Study Subjects

This was a study evaluating patients with bat ears. Informed consent and approval were obtained.

Collection of Data

This study was carried out on 35patients (26 males (74.3%) and 9 females (25.7%)) with age ranging from 5 to 36 years with bat ear. This study was carried out in Al-Azhar University Hospital, Damietta, Egypt at 2022–2023. Written informed consent for all procedures was obtained from patients. Detailed history, clinical examination, routine investigations were carried out. Standard Performa was prepared dually filled for each patient. Only those patients were included in the study who were suffering from bat ear and were available for follow up and those patients who were unfit for surgery and those cases operated somewhere else were excluded from the study. The follow up of cases was carried out from 3 months to 12 months. All the patients were operated for otoplasty (Masturde technique).

Exclusion Criteria

patients unfit for surgery.

Consent

Informed Consent

and approval were obtained.

Preoperative Details

Prior to surgery, pay close attention to each patient’s and parent’s concerns and make sure to ask and address them. Preoperatively addressing concerns and expectations raises the likelihood that a technically flawless otoplasty will be looked back on with gratitude and satisfaction after surgery. Developing a customized surgical plan that offers the patient a superior outcome is a critical first step towards achieving patient satisfaction. The first step in this process is to carefully evaluate the flaw. The most important component of preoperative planning is accurately assessing the patient’s deformity [20].

Correcting protrusion, reversing the helix and antihelix that are clearly visible while maintaining a visible helical rim, forming a smooth anti-helical fold, preventing disruption of the postauricular sulcus, and preventing a “pinned back” or plastered-down appearance are the objectives of otoplasty. The method must be adjusted to address minute variations between the two sides and each deformity must be critically assessed in order to meet these objectives. Though this method emphasizes the role of the concha in the prominent ear, previous emphasis has focused on the significance of correcting the antihelical effacement. This leads to a treatment plan that seamlessly accomplishes all of the aforementioned objectives while ensuring that a pointed back appearance and sharp, irregular antihelix are avoided [21].

Every patient needs to have their family doctor perform a standard history and physical examination in addition to any necessary laboratory work for adults. To ensure that all relevant views are captured on camera, preoperative photos are taken and examined [11].

The deformity’s specifics are addressed, and any potential asymmetries between the two ears are noted with caution. The process is explained in detail, including a review of the anesthesia (general anesthesia in most pediatric cases, possibly local anesthesia with or without sedation in minor cases or in adults), incisions, dressings, and postoperative care. Risks are reviewed along with their treatment options and implications. These risks include infection, hematoma, and chondritis. A discussion of potential mild asymmetry after otoplasty that might be fixed with a small revisional procedure is included [12].

In most cases, and especially in pediatric cases, it is useful to look at pictures of a number of otoplasty cases that illustrate a range of prominent ear deformities; in the case of some of the more atypical deformities, such as helical rim and constricted ears, it helps to explain possible limitations of the surgery while still highlighting its advantages as shown in Figs. 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 and 22 [22].

Preoperative, intraoperative, and early postoperative evaluations of the auricular cartilage’s properties as a material and its biomechanical reactions to internal and external forces are necessary. Selecting the right surgical course requires careful consideration of the limber, stiff, or floppy cartilage that makes up the auricular cartilage [23].

Procedure

Anesthesia

Otoplasty can be performed under various depths of anesthesia including local anesthesia, intravenous sedation (also called twilight anesthesia, MAC anesthesia, or IV sedation), and general anesthesia. Each option has advantages and disadvantages, including variations in cost, awareness, safety, and side effects. Because otoplasty is considered to be an elective, non-emergent procedure, pre-operative testing is sometimes performed to determine anesthetic suitability. However, the vast majority of otoplasty patients enjoy good overall health and can choose from any of the aforementioned anesthetic options. Regardless of the anesthetic option, all otoplasty anesthesia is performed in conjunction with local anesthesia (lidocaine mixed with epinephrine) to numb the nose and to reduce bleeding. Few surgeons use local anesthesia alone due to the anxiety and discomfort associated with injecting and operating upon a fully awake patient [24].

Steps

Position

The patient was placed in supine position with the head supported in a ring and the head end elevated 15 degrees.

Procedure

The posterior skin excision is fashioned in an elliptical pattern with the posterior line at the sulcus. The excision should be planned so as to bring the helical margin to 2 cm of the mastoid, approximately. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are incised down to the perichondrium and the soft tissue island was removed. The skin is undermined to the border of the helical rim laterally and to the external auditory canal and mastoid periosteum medially [25].

With gentle pressure the auricle was bent to form a normal antihelix. Three needles or sutures were passed through the anterior surface of the ear, at the junction of the concha and the antihelix, to determine the lateral extent of the conchal cartilage resection. The exit points of the needles were marked with methylene blue and a curvilinear incision was made in the posterior surface of the auricle. The cartilage was then incised and elevated from the anterior perichondrium and finally resected [26].

The cartilage was manually resected to form a new antihelix. Marking sutures were then passed through the anterior surface of the ear, by molding the new antihelical fold with a needle containing 3 − 0 sutures, which were visible on the exposed posterior surface of the cartilage. This was performed at three points: superior crus, middle portion of the antihelix, antihelix at the level of the antitragus [27].

The silk marking sutures guide the position at which white Mersilene Mustarde sutures were placed posteriorly. The Mersilene sutures were placed in a horizontal mattress fashion at right angle to the silk guide sutures. The Mustarde sutures were tightened sufficiently to create a natural appearing antihelix. The middle sutures were tied first to form the most prominent portion of the antihelix followed by superior and inferior sutures [28].

The conchal set back was performed by passing a horizontal 4 − 0 Mersilene mattress from midpoint of the antihelical cartilage to the mastoid periosteum. Skin was closed with 4 − 0 prolene sutures. Gauze was placed in the posterior auricular region and molded around the concha and scapha followed by more gauze around the ear, finally mastoid process dressing was applied [29]. As shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

Fig. 1.

Site of incision

Fig. 2.

Elliptical incision

Fig. 3.

Undermining the skin and exposure of surface of the posterior surface of the auricle

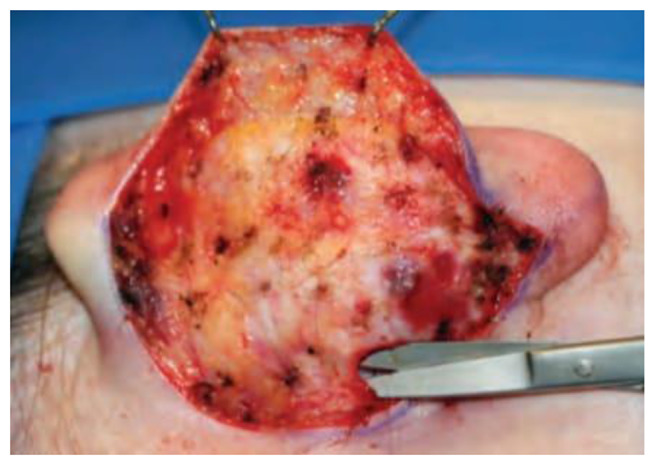

Fig. 4.

The subcutaneous tissue over the mastoid the cartilage is dissected

Fig. 5.

The bulky postauricular soft tissue, auricularis posterior muscle fibers and fibrofatty tissues excised

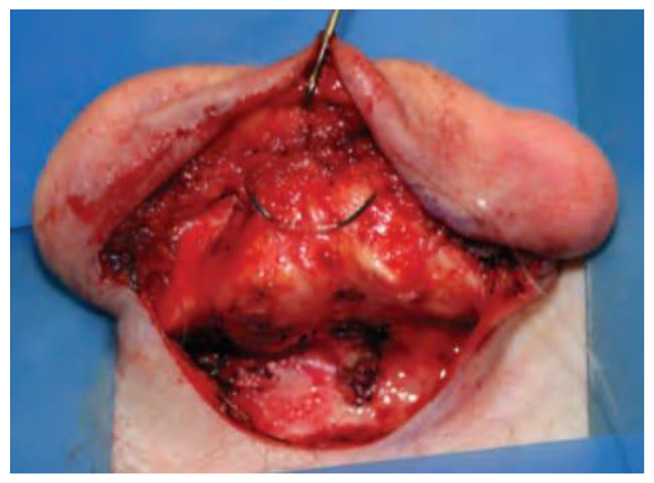

Fig. 6.

Fixation of the antihelical fold with mattress sutures

Fig. 7.

Antihelix Formation with Mustarde Sutures

Fig. 8.

Conchal Setback

Fig. 9.

Final Shape of the auricle

Contraindications

Otoplasty is contraindicated in any patient with unrealistic expectations. Patients must receive appropriate preoperative counseling. Discuss existing facial asymmetries, and emphasize that a restoration of anatomic balance to the face is the goal of any surgery. Patients unable or unwilling to cooperate with postoperative care are not candidates for surgery. Advise patients with a history of hypertrophic scarring or keloids that these may occur after otoplasty, possibly distorting an otherwise excellent surgical result. Patients with chronic otitis media, otitis externa, or conditions such as scalp infections or acne must be treated well in advance of surgery. A simple surgical wound infection can lead to an ear-threatening chondritis [30].

Postoperative Details

Follow-Up

Observe the patient for routine follow-up care on the first postoperative day and for suture removal and examination at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Follow-up photographs are made at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month visits with standard views for comparison. Subsequent follow-up visits are conducted periodically, and patients are photographed and the images are compared before and after the surgical procedure as shown in Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 [31].

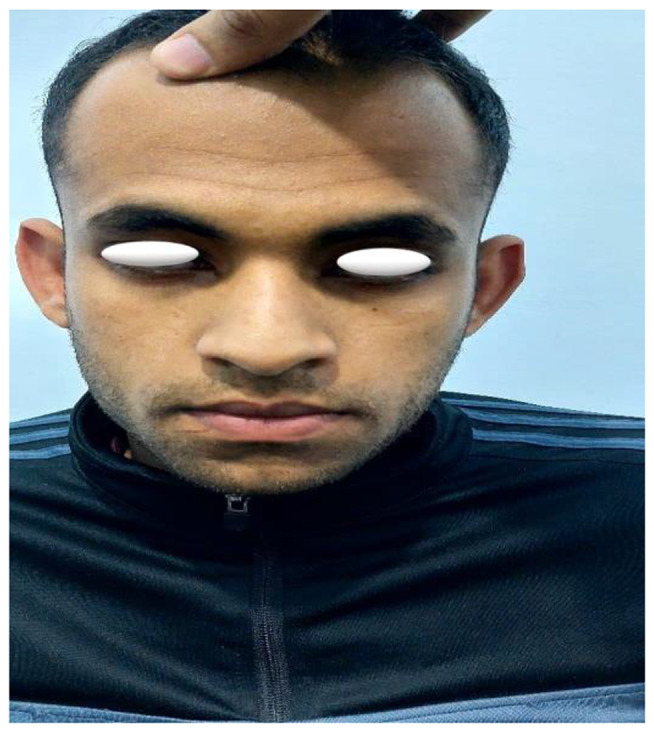

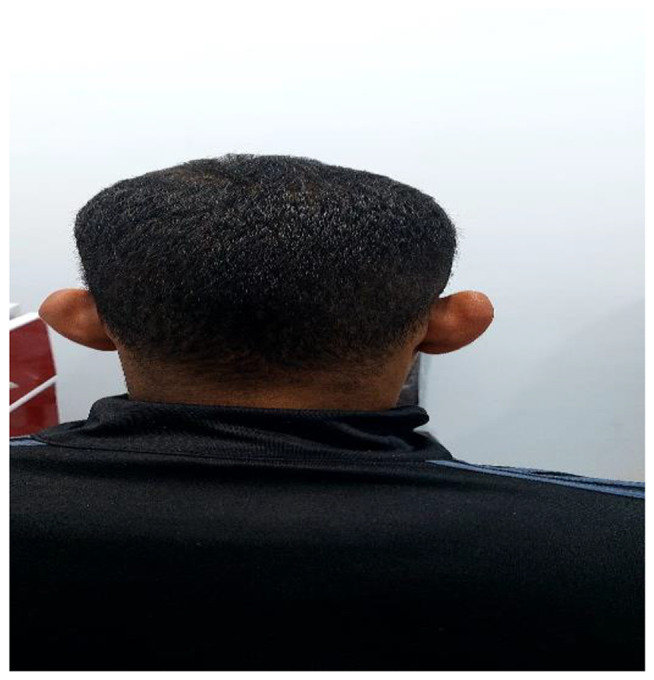

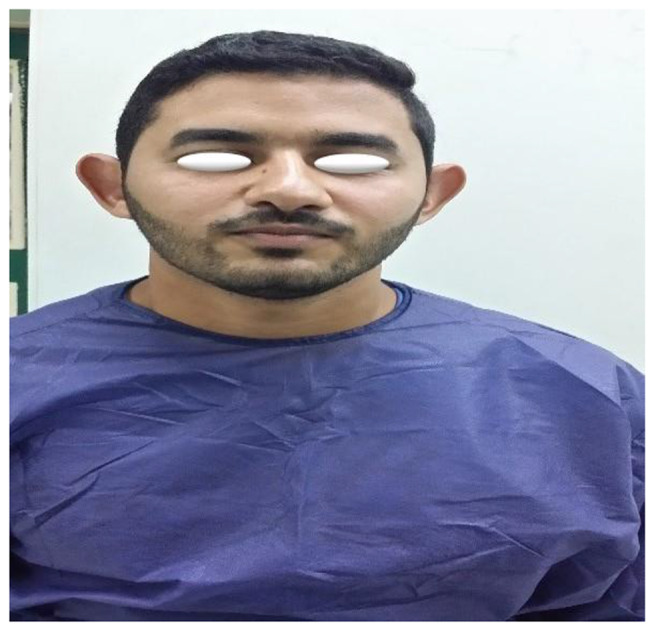

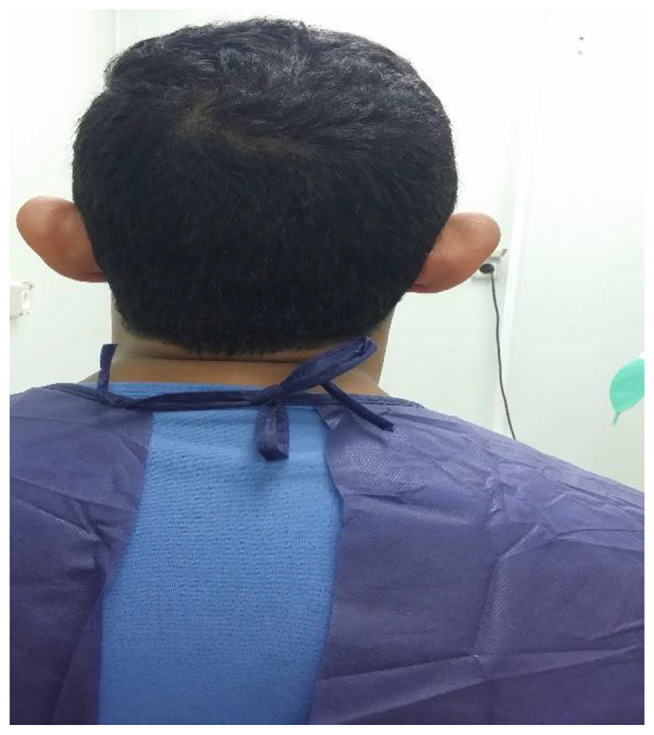

Fig. 10.

Before otoplasty

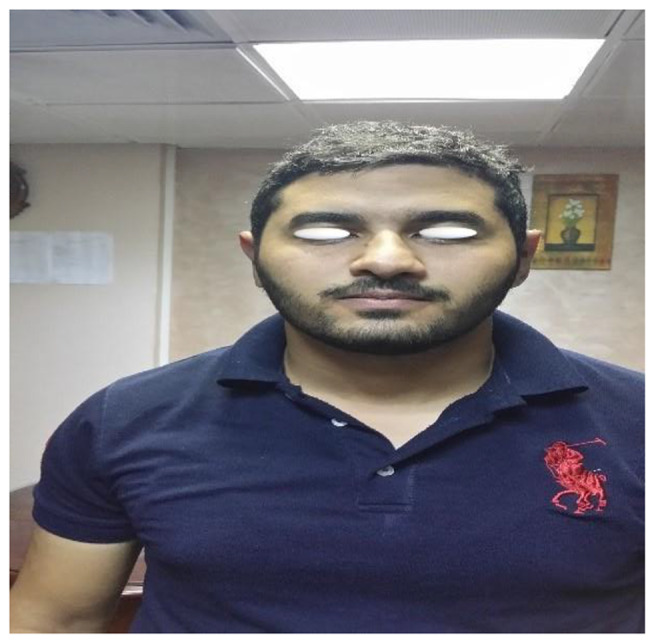

Fig. 11.

After otoplasty

Fig. 12.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 13.

After otoplasty

Fig. 14.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 15.

After otoplasty

Fig. 16.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 17.

After otoplasty

Fig. 18.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 19.

After otoplasty

Fig. 20.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 21.

After otoplasty

Fig. 22.

Before otoplasty

Fig. 23.

After otoplasty

Complications

Otoplasty complications are categorized into two groups: early sequelae that appear up to 14 days after surgery, and late sequelae that appear beyond that 14-day window. Hematoma and pain are uncommon side effects that can be brought on by coagulopathy, postoperative trauma, insufficient hemostasis, or the rebound effect of adrenaline. On the first postoperative day, the ears are routinely examined. One uncommon consequence is infection. To avoid chondritis, begin appropriate and timely antibiotic treatment as soon as there is a suggestive sign. Hospitalization, intravenous antibiotics, and drainage are typically needed if chondritis is diagnosed. If chondritis is not treated promptly, significant cartilage loss and ear deformity may result [32].

Hypertrophic scarring or keloids in the postauricular incision occur in rare cases. The accepted treatments for hypertrophic scarring and keloids are pressure application and intralesional injection of corticosteroid preparations; after keloids are excised in adults, low-dose radiation seems to help prevent recurrence. Suture complications as erosion of the postauricular thin skin; if a suture is exposed, it is usually many months after the original otoplasty, and the suture is no longer necessary—it is simply removed. Hypersensitivity in the postauricular area is an uncommon complication, especially during the height of wound immaturity. Regenerating axons typically cause this tenderness, which lessens with time [33].

Recurrence of ear prominence is extremely uncommon and happens when the pull of the sutures causes soft, floppy cartilage to buckle or when the anchoring tissues are too strong for the stiff, heavy conchal cartilage. The reasons behind the relapse are taken into consideration when choosing a repeat procedure. Another relapse is unlikely if the procedure is carefully chosen and carried out. For six to twelve months following surgery, an elastic headband is worn [34].

Biomechanical effects or external pressures (such as shifting head dressings or gravitational pressure during sleep) can cause contour defects and irregularities. For smaller irregularities, Steri-Strips can be used to correct them in the early postoperative phase; for larger areas of involvement, elastic headbands and ear wedges can be used. A positive response is typically the consequence of early diagnosis and quick treatment. Over correction of the ears can result in a hidden helix, which is invisible from a frontal perspective. This is a common finding in normal ears, but in an otoplasty, it is not regarded as aesthetically pleasing. A telephone deformity results from either insufficient correction of the upper and lower poles or excessive reduction of the concha, which causes the upper and lower poles to be relatively prominent [35].

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Data analysis was performed by SPSS software, version 25 (SPSS Inc., PASW statistics for windows version 25. Chicago: SPSS Inc.). Qualitative data were described using number and percent. Quantitative data were described using mean ± Standard deviation for normally distributed data after testing normality using Kolmogrov-Smirnov test. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the (≤ 0.05) level. Chi-Square test was used to compare qualitative data between groups as appropriate. Student t test was used to compare 2 independent groups for normally distributed data.

Results

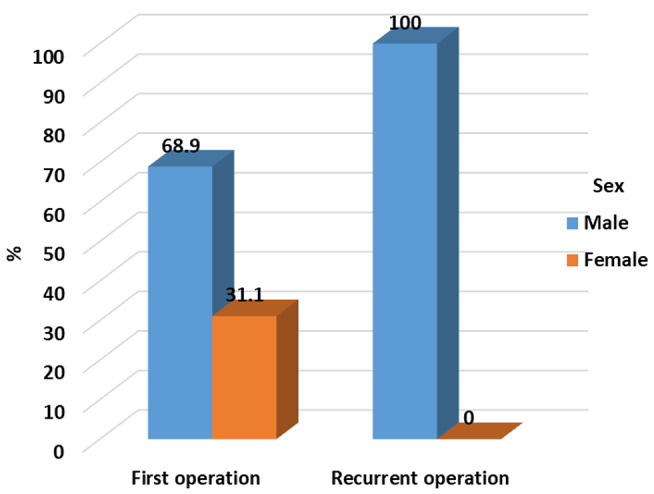

This study was carried out on 35 patients (26 males (74.3%) and 9 females (25.7%)) with age ranging from 5 to 36 years with bat ear as shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4; Figs. 24 and 25.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the studied group

| NO | Total number = 35 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/ years mean ± SD (Min-MAX) | 24.78 ± 16.55 ( 5–36) | |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 26 | 74.3% |

| Females | 9 | 25.7% |

Table 2.

Type of operation

| First operation | 29 | 82.9% |

|---|---|---|

| Recurrent operation | 6 | 17.1% |

Table 3.

Sex difference between cases with first and recurrent operations

| First operation | Recurrent operation | Test of significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 29(%) | N = 6(%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 20 (68.9) | 6 (100) | X2 =2.51 |

| Female | 9 (31.1) | 0 | P = 0.133 |

χ2=Chi-Square test

Table 4.

Age difference between cases with first and recurrent operations

| First operation | Recurrent operation | Test of significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 29 | N = 6 | ||

| Age / years | 25.01 ± 12.6 | 24.52 ± 13.25 | t = 0.086 |

| p = 0.93 |

t: Student t test

Fig. 24.

Type of operation

Fig. 25.

Type of operation among sex groups

Otoplasty results are generally lifelong and will improve the self-confidence. The goals of otoplasties are to make the ears appear more natural in comparison to the head and help with the overall contour of the ears. Final ear surgery results will be visible after a two weeks recovery period, with small improvements appearing for up to 12 months post-procedure.

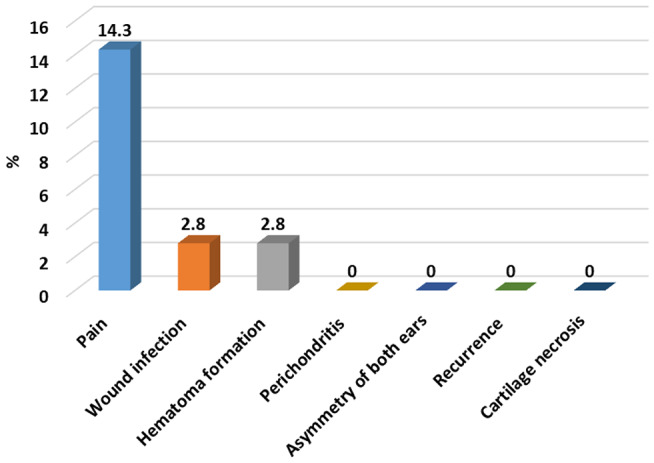

In our study the otoplasty operation was done for the first time in 29 cases and 6 cases as a revision surgery. Complications were found in 7 cases (20%) as shown in Table 5; Fig. 26.

Table 5.

Incidence of complications

| NO | Complications | No of Patient [35] | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wound infection | 1 | 2.8 |

| 2 | Hematoma formation | 1 | 2.8 |

| 3 | Pain | 5 | 14.3 |

| 4 | Perichondritis | 0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Asymmetry of both ears | 0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | Recurrence | 0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | Cartilage necrosis | 0 | 0.0 |

Fig. 26.

Type of operation among sex groups

Discussion

Otoplasty is a cosmetic procedure used to change the position, shape, or size of the ear using permanent sutures. The primary indication for otoplasty is to correct promin auris, or protruding ears.

To perform successful otoplasty operation, surgeons should be highly experienced and well-trained. Open discussion with the patient to select appropriate surgical technique and its possible risks with your plastic surgeon to ensure the highest level of safety and satisfaction.

This study was carried out on 35 patients (26 males (74.3%) and 9 females (25.7%)) with age ranging from 5 to 36 years with bat ear.

In our study the otoplasty operation was done for the first time in 29 cases and 6 cases as a revision surgery. Complications were found in 7 cases (20%).

Conclusion

A proper understanding of the diagnosis, indications, and surgical techniques will lead to positive outcomes in otoplasty.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks and gratitude to Mr. Ahmed Shawky Abdel-Ghani for the linguistic review of this research paper and his continuous support. Many thanks and gratitude to all of those with whom I have had the pleasure to work during this and other related projects.

Author Contributions

M. A.: methodology, idea formulation, data collection and review writing and revision; M. A, A. I: reference collection and final revision, formal analysis and idea formulation; N. Z: editing final draft and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Funding

The authors have no funding or financial relationships to disclose.

Data Availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for Publication

Formal consent was signed by the patients to share and to publish their data in this research.

Consent to Participate

Explanation and informed written consent for this research has been taken from all patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Driessen J, Borgstein J, Vuyk H (2011 Nov) Defining the protruding ear. J Craniofac Surg 22(6):2102–2108 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Jones E, Gibson J, Dobbs T, Whitaker I (2020) The psychological, social and educational impact of prominent ears: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 73(12):2111–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Songu M, Kutlu A (2014 Sep) Long-term psychosocial impact of otoplasty performed on children with prominent ears. J Laryngol Otol 128 (9):768–771 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kajosaari L, Pennanen J, Klockars T (2017 Sep) Otoplasty for prominent ears - demographics and surgical timing in different populations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 100:52–56 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Papadopulos N, Niehaus R, Keller E, Henrich G, Papadopoulos O, Staudenmaier R et al (2015) The psychologic and psychosocial impact of Otoplasty on children and adults. J Craniofac Surg 26:2309–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Songu M, Kutlu A (2014 Jun) Health-related quality of life outcome of children with prominent ears after otoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 271(6):1829–1832 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sirin S, Abaci F, Selcuk A, Findik OB, Yildirim A (2019) Psychosocial effects of otoplasty in adult patients: a prospective cohort study.Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 276:1533–1539 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hao W, Chorney JM, Bezuhly M, Wilson K, Hong P (2013) Analysis of Health-Related Quality-of-life outcomes and their predictive factors in Pediatric patients who Undergo Otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 132:811e–817e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masnari O, Schiestl C, Rossler J, Gutlein SK, Neuhaus K, Weibel L et al (2013) Stigmatization predicts Psychological Adjustment and Quality of Life in Children and adolescents with a facial difference. J Pediatr Psychol 38:162–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun T, Hainzinger T, Stelter K, Krause E, Berghaus A, Hempel JM (2010) Health-Related Quality of Life, Patient Benefit, and clinical outcome after Otoplasty using suture techniques in 62 children and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg 126:2115–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker D, Lai S, Wise J (2006) Steiger j. Analysis in Otoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 14:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider AL, Sidle DM (2018) Cosmetic Otoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 26(1):19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fioramonti P, Serratore F, Tarallo M, Ruggieri M, Ribuffo D (2014) Otoplasty for prominent ears deformity. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 18(21):3156–3165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathews R (2012) Bat ears: Pinnaplasty. The Plastic Surgeon. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 2 December

- 15.Ali K, Meaike J, Maricevich R, Olshinka A (2017) The protruding ear: Cosmetic and Reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg 31(3):152–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haworth R, Sobey S, Chorney JM, Bezuhly M, Hong P (2015 Dec) Measuring attentional bias in children with prominent ears: a prospective eye-tracking study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 68(12):1662–1666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kurt Ozkaya N, Mert DG, Bitgen M, Cepni M (2020) Prospective evaluation of Psychological Healing in adults who underwent Otoplasty for prominent ear. Aesthetic Plast Surg. May 18 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lin S (2022) October. Prominent ear. Medscape.org. Retrieved 27

- 19.Boroditsky M, Van Slyke A, Arneja J (2020) Outcomes and complications of the Mustardé Otoplasty: a good-fast-cheap technique for the prominent ear deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 8(9):e3103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley P, Hollier L, Stal S (2003) Otoplasty: evaluation, technique, and review. J Craniofac Surg 14:643–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janis JE, Rohrich RJ, Gutowski KA (2005) Otoplasty Plast Reconstr Surg 115:60e–72e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ungarelli LF, de Andrade CZ, Marques EG et al (2016) Diagnosis and prevalence of prominent lobules in otoplasty: analysis of 120 patients with prominent ears. Aesthetic Plast Surg 40:645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal A, Bahia H, Ahmad T et al (2006) Comparison of cartilage scoring and cartilage sparing otoplasty—a study of 203 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 59:1170–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer H, Bouhadana G, Cugno S Local Versus General Anesthesia in Pediatric Otoplasty: a cost and efficiency analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2023 Jul 2:10556656231186268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Punj P, Chong HP, Cundy TP et al (2018) Otoplasty techniques in children: a comparative study of outcomes. ANZ J Surg 88:1071–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawar SS, Koch CA, Murkami C (2015) Treatment of prominent ears and otoplasty: a contemporary review. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 17(6):449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basat S, Ceran F, Askeroglu U et al (2016) Preventing suture extrusion and recurrence in Mustardé and Furnas otoplasties by using laterally based postauricular dermal flap, long-term results. J Craniofac Surg 27:1476–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun T, Hainzinger T, Stelter K et al (2010) Health-related quality of life, patient benefit, and clinical outcome after otoplasty using suture techniques in 62 children and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg 126:2115–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horlock N, Misra A, Gault DT (2001) The postauricular fascial flap as an adjunct to Mustardé and Furnas type otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 108:1487–1490 discussion 1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenneth L, Katrib K StatPearls [Internet]. Jan-2023

- 31.Binet O, El Ezzi A, Roessingh D (November 2020) A retrospective analysis of complications and surgical outcome of 1380 ears: experience review of paediatric otoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Volume 138:110302 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Sadhra S, Motahariasl S, Hardwicke J (2017 Aug) Complications after prominent ear correction: a systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 70(8):1083–1090 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Calder J, Naasan A (1994) Morbidity of otoplasty: a review of 562 consecutive cases Br. J Plast Surg 47(3):170–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey Ann. Surg 240(2):205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadhum M, Atherton S, Jawad A, Wilson-Jones N, Javed M A retrospective analysis of Pinnaplasty outcomes: the Welsh experience. Facial Plast Surg. 10.1055/a-2150-8632 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.