Abstract

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which generally has an aggressive course. Its pathophysiology seems to be related with the malignant transformation of B-cell mantle zone lymphocytes due to the CCND1 rearrangement. The occurrence of MCL in the oral cavity is especially rare. In this report, we present an exceptional case of oral MCL diagnosed in the palate in a 56-year-old male patient, highlighting its distinct morphological and immunohistochemical features that may assist in the accurate diagnosis.

Keywords: Mantle cell lymphoma, Non-hodgkin lymphoma, Oral lymphoma, Cyclin D1

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which generally has an aggressive course, accounting for 6–10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Its pathophysiology seems to be related with the malignant transformation of B-cell mantle zone lymphocytes due to the CCND1 rearrangement [1]. MCL primarily affects lymph nodes in men during their sixth decade of life, but it can also manifest extranodally in sites such as the gastrointestinal tract, Waldeyer’s ring, skin, lacrimal glands, and central nervous system [1]. The occurrence of MCL in the oral cavity is especially rare, with a higher incidence observed in the hard palate presenting as asymptomatic nonulcerated swellings [2, 3]. A comprehensive immunohistochemical panel is required for the MCL diagnosis. In this report, we present an exceptional case of oral MCL diagnosed in the palate, highlighting its distinctive morphological and immunohistochemical features that may assist in the accurate diagnosis.

Case Report

A 56-year-old male presented to a healthcare service due to a persistent palate lesion that had been present for 2 years following an eating trauma. During the medical history interview, the patient disclosed a 50-year smoking habit. The extraoral examination revealed no abnormalities. In the intraoral examination, a nodule, measuring 2.0 cm, was observed in the midline in transition between the hard and soft palate. The lesion was asymptomatic, with a fibroelastic consistency, exhibited areas of erythema and vascularity in the surface.

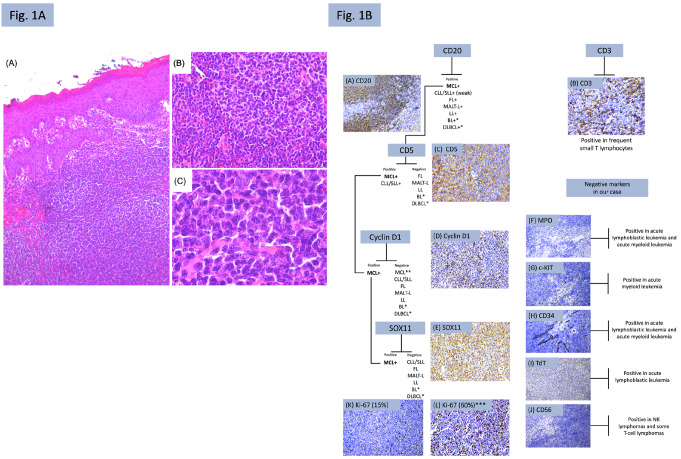

An incisional biopsy was performed, and microscopic evaluation revealed a diffuse and monotonous proliferation of small neoplastic cells. These cells appeared as small to medium-sized lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, evenly distributed chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 1A). Based on these morphological features, an immunohistochemical panel for a histologically low-grade lymphoma was conducted. The tumor was positive for CD20, CD5, Cyclin D1, and SOX11. Frequent small T lymphocytes exhibited positivity for CD3. Negativity was observed for CD56, TdT, and MPO. Internal control showed positivity for CD34 and c-KIT. The Ki-67 index was determined to be 15% (Fig. 1B). The immunohistochemical description panel is detailed in Table 1. The diagnosis of extranodal mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in the palate was established. The patient was subsequently referred for onco-hematological treatment.

Fig. 1.

A, (A): Classic variant characterized by a diffuse and monotonous proliferation of small-sized neoplastic cells (hematoxylin and eosin (H&E 5x); (B, C): Neoplastic cells in the classic variant present as small lymphocytes with irregular nuclear contours and inconspicuous nucleoli (H&E; 20x, 100x); B, Diagnostic algorithm and immunohistochemical analysis of the present case. (A) CD20 showed strong and diffuse positivity (IHC, 20x); (B) CD3 positivity was observed in frequent small T lymphocytes (IHC, 40x); (C) CD5 was positive (IHC, 40x); (D) Nuclear positivity for Cyclin D1 (IHC; 40x); (E) Nuclear positivity for SOX11 (IHC; 40x) (F, G, H, I, J): negativity in neoplastic cells (IHC, 20x); (K) Ki-67 index was 15% (IHC, 20x); (L): ***example of Ki-67 marking rate in a case of MCL (blastoid variant) (IHC, 20x); MCL: Mantle cell lymphoma; CLL/SLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/ small lymphocytic lymphoma; FL: Follicular lymphoma; MALT-L: Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; LL: Lymphoblastic lymphoma; BL: Burkitt’s lymphoma; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. *: when the morphology is compatible with the blastoid and pleomorphic variants; **: in cases where Cyclin D1 is negative, SOX11 can be used to confirm the diagnosis of MCL

Table 1.

Summary of the immunohistochemical panel used in our case

| Antibody | Company | Clone | Dilution | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD20 | DAKO | L26 | 1:300 | Positive |

| CD5 | DAKO | 4C7 | 1:30 | Positive |

| Cyclin D1 | DAKO | EP12 | 1:100 | Positive |

| SOX11 | Cell Marque | MRQ58 | 1:50 | Positive |

| CD3 | DAKO | A0452 | 1:150 | Positive in frequent small T lymphocytes |

| MPO | Bio SB | RPab | 1:200 | Negative |

| c-KIT | Cell Marque | YR145 | 1:100 | Negative (positive internal control) |

| CD34 | DAKO | QBEnd/10 | 1:150 | Negative (positive internal control) |

| TdT | Cell Marque | EP266 | 1:100 | Negative |

| CD56 | Cell Marque | 123C3.D5 | 1:100 | Negative |

| Ki-67 | DAKO | MIB-1 | 1:600 | 15% rate |

Discussion

MCL usually presents clinically in men in their sixth or seventh decades of life, with an average age of 70 years. Extranodal involvement is rare and, in the oral cavity, only a few cases of MCL have been reported to date, representing around 8.4% of cases. The lesions usually present as asymptomatic, non-ulcerated swellings on the palate, as observed in our case [1]. The World Health Organization classification of lymphoid tumors recognizes that MCL is a lymphoid neoplasm that presents classically as a monotonous proliferation of small to medium-sized cells, with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, round nuclei, and and the absence of evident nucleoli (classic variant) [1, 4]. In addition to the classical variant, MCL exhibits two other variants: blastoid and pleomorphic. In the former, cells are of medium size, with speckled chromatin and an increased number of mitoses. In pleomorphic, the cells are medium to large size, displaying greater pleomorphism and nuclear irregularity [1, 4].

Regardless of the morphological presentation, MCL exhibits immunohistochemical expression of CD20, CD5, Cyclin D1, and SOX11, in addition to BCL2. Negativity is observed for CD3, CD10, BCL6, and CD23 [2, 5]. The hallmark oncogenic event of MCL is the strong nuclear expression of the cyclin D1 protein in neoplastic B cells due to the genetic translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) between the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) and CCND1 genes [4, 5]. However, there are rare cases of Cyclin D1-negative MCL, where mutations in the CCND2 oncogene led to the expression of Cyclin D2 and Cyclin D3. In such cases, SOX11 can be used as an additional marker, as its nuclear positivity is detected in both Cyclin D1-positive and Cyclin D1-negative cases [1]. In our case, the diagnosis of MCL was established based on Cyclin D1 and SOX11 positivity and other immunohistochemical findings, as shown in our diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, accurately determining the diagnosis of the lymphoma subtype is often challenging, given that MCL carries a more unfavorable prognosis compared to other low-grade histological lymphomas, resembling that of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) [1, 6].

Morphologically, MCL can show various growth patterns. This varies from the “in situ” form, in which there is only an expansion of the mantle zone of the follicles without loss of nodal architecture, progressing to the nodular form, characterized by an extensive expansion of the mantle zone in the lymph nodes with distorted architecture, and, finally, a diffuse form, characterized by the total loss of nodal architecture [1, 4]. Depending on the histological type (classic, blastoid or pleomorphic) and the histological growth pattern, different differential diagnoses should be considered [1, 4].

When MCL presents in its classic “in situ” form, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia can be a differential diagnosis. However, when assessed by immunohistochemistry, cyclin D1 and SOX11 are negative. In its nodular form, MCL must be differentiated from follicular lymphoma (FL), Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and Marginal zone lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). FL is commonly negative for CD5, Cyclin D1 and SOX11, but shows expression of CD10 and BCL6, in addition to the expression of BCL2 due to t(14;18)(q32;q21) [5]. CLL/SLL will commonly be positive for CD20 (weak), CD5, CD23 and CD43 while CD10, CD103, CD38/138, Cyclin D1, SOX11 are negative. As in peripheral blood/bone marrow involved tissues the co-expression of CD5 and CD23 in mature B cells is often found and the expression of CD5 is observed in MCL and in CLL, it becomes useful to confirm the diagnosis of CLL/SL [1, 4]. The negativity for Cyclin D1 and SOX11 contributes to this differentiation [5]. MALT is another type of low-grade B-cell lymphoma that enters in the differential diagnosis of extranodal lymphomas. This tumor usually shows negativity for CD5, CD10, BCL6, CD23, Cyclin D1 and SOX11. Due to the absence of positivity for CD5, Cyclin D1 and SOX11, the diagnosis of MCL is ruled out [1, 4].

When MCL presents in its diffuse form, in addition to FL, CLL/SLL and MALT, described above, T lymphomas and leukemias should be excluded. As the lesion affects the palate, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL) should also be a differential diagnosis [4, 7]. ENKL is a rare histological subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that is strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and commonly affects the nasal cavity region. The lesion can perforate the palate region up to the oral cavity, causing necrosis and pain [7]. In the microscopic diagnosis, negativity for CD56 and T-cell markers, combined with positivity for B-cell markers, contribute to excluding ENKL as the diagnosis in our case [7]. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ALL) as well as acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML) must be discarded. Immunohistochemistry results will show negativity for MPO, c-KIT, CD34, and TdT will contribute to excluding ALL [8], while negativity for MPO, c-KIT, and CD34 for AML [9].

It is important to note the morphological differences between the classic variant of MCL, the blastoid, and pleomorphic variants. When the blastoid variant is present, the diagnoses of ALL and AML must also be excluded, as described above. Also, Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) must be excluded. BL is commonly positive for CD20, CD10, BCL6, MYC, and negative for BCL2, CD5, Cyclin D1, and SOX11 [4, 10]. EBV can be positive by in situ hybridization [1, 5, 11]. A proliferative rate of practically 100% seen by Ki-67 marker is also found [12]. However, in cases of the blastoid variant, even though the Ki-67 index is higher than the conventional variant, this index remains lower than in cases of BL (Fig. 1B-L). When the pleomorphic variant presents, in addition to the differential diagnoses of AML and T lymphomas already described, DLBCL must also be differentiated from the pleomorphic variant. In cases of DLBCL, negativity for Cyclin D1, SOX11 and infrequent expression of CD5 will be found [2].

There is no standard treatment for MCL. Therapy combines chemo-immunotherapy with/out stem cell transplantation [1, 11]. The survival rate ranges from 29.2 to 54.5%, with improvements following the introduction of rituximab and other novel biological agents [1, 2, 4]. The observed better survival trend for oral MCL is also in accord with a previously recorded better 5-year overall survival (approximately 63%) in primary MCL tumors of head and neck region, compared to other nodal or extranodal sites [1, 2, 4]. The patient reported here was referred for onco-hematological treatment, however the follow-up was lost after a period.

Conclusion

In summary, due to the histological heterogeneity of lymphomas, a comprehensive immunohistochemical panel is mandatory for the subtype diagnosis. Although MCL is uncommon in the oral cavity, head and neck pathologists must be familiar with this tumor and its differential diagnosis. The evaluation of Cyclin D1 and SOX11 expression is particularly important in suspected cases of MCL.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Coordination of Training of Higher Education Graduate Foundation (CAPES, Brasilia, Brazil, Finance Code 001) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant number 22/11861-6).

Author Contribution

M.W.A. Gonçalves, F.V. Mariano and L.L.L. de Freitas contributed to the conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation drafted and critically revised the manuscript. L. Lavareze, C.T. Chone, and E.S.A. Egal contributed to the data acquisition and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. A. Altemani contributed to the conception, design, and critically revised manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jain P, Wang M (2019) Mantle cell lymphoma: 2019 update on the diagnosis, pathogenesis, prognostication, and management. Am J Hematol 94:710–725. 10.1002/ajh.25487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho MVR, Rodrigues-Fernandes CI, de Cáceres CVBL, Mesquita RA, Martins MD, Román Tager EMJ et al (2023) Mantle cell lymphoma involving the oral and maxillofacial region: a study of 20 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 135:101–109. 10.1016/j.oooo.2022.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgaki M, Theofilou VI, Pettas E, Piperi E, Stoufi E, Panayiotidis P et al (2022) Blastoid Mantle Cell Lymphoma of the palate: report of a rare aggressive entity and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 16:631–642. 10.1007/s12105-021-01391-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Seto MM-HH (2017) Mantle cell lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, edsWorld Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, revised. Lyon, Fr IARC. ;4th ed:285–90

- 5.Wagner VP, Rodrigues-Fernandes CI, Carvalho MVR, Santos JN, Barra MB, Hunter KD et al (2021) Mantle cell lymphoma, malt lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma of the oral cavity: an update. J Oral Pathol Med 50:622–630. 10.1111/jop.13214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S, Tang G, Jain P, Lin P, Xu J, Miranda RN et al (2024) SOX11 + large B-Cell neoplasms: cyclin D1-Negative Blastoid/Pleomorphic Mantle Cell Lymphoma or large B-Cell lymphoma? Mod Pathol 37:100405. 10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Arruda JAA, Abrantes T, de Cunha C, Roza JLS, Agostini ALOC, Abrahão M (2021) Mature T/NK-Cell lymphomas of the oral and maxillofacial region: a multi‐institutional collaborative study. J Oral Pathol Med 50:548–557. 10.1111/jop.13205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrestha R, Bhatt VR, Guru Murthy GS, Armitage JO (2015) Clinicopathologic features and management of blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 56:2759–2767. 10.3109/10428194.2015.1026902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes KS, Gallottini M, Castro T, Amato MF, Lago JS, Braz-Silva PH (2018) Gingival leukemic infiltration as the first manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia. Spec Care Dent 38:160–162. 10.1111/scd.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreyling M, Klapper W, Rule S (2018) Blastoid and pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma: still a diagnostic and therapeutic. Challenge! Blood 132:2722–2729. 10.1182/blood-2017-08-737502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H-Y, Zu Y (2017) Diagnostic algorithm of common mature B-Cell lymphomas by immunohistochemistry. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141:1236–1246. 10.5858/arpa.2016-0521-RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arboleda LPA, Rodrigues-Fernandes CI, Mariz BALA, de Andrade BAB, Abrahão AC, Agostini M et al (2021) Burkitt lymphoma of the head and neck: an international collaborative study. J Oral Pathol Med 50:572–586. 10.1111/jop.13209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]