Abstract

Myofibers are large multinucleated cells that have long thought to have a rather simple organization. Single-nucleus transcriptomics, spatial transcriptomics and spatial metabolomics analysis have revealed distinct transcription profiles in myonuclei related to myofiber type. However, the use of local tissue collection or dissociation methods have obscured the spatial organization. To elucidate the full tissue architecture, we combine two spatial omics, RNA tomography and mass spectrometry imaging. This enables us to map the spatial transcriptomic, metabolomic and lipidomic organization of the whole murine tibialis anterior muscle. Our findings on heterogeneity in fiber type proportions are validated with multiplexed immunofluorescence staining in tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus and soleus. Our results demonstrate unexpectedly strong regionalization of gene expression, metabolic differences and variable myofiber type proportion along the proximal-distal axis. These new insights in whole-tissue level organization reconcile sometimes conflicting results coming from previous studies relying on local sampling methods.

Subject terms: Transcriptomics, Metabolomics

Multi-dimensional analysis of gene expression, myofiber types and metabolic activity in whole skeletal muscle reveals specific regionalization of gene expression and metabolites related to the glycolytic and oxidative potential of myofibers

Introduction

Myofibers in murine tibialis anterior (TA) muscle are long and cylindrical cells composed of hundreds of post-mitotic myonuclei sharing a common cytoplasm. With a diameter up to 70 μm and lengths up to 1.5 cm in murine TAs1,2, the myofiber is a syncytium that originates through fusion of myoblast during embryonic and fetal development3. Myofibers are classified into four distinct types based on the expression of MyHC isoforms Myh7 (type 1), Myh2 (type 2a), Myh1 (type 2x) and Myh4 (type 2b)4,5. These different myofiber types rely on oxidative (type 1 and type 2a) or glycolytic metabolism (type 2x and type 2b) and are further subdivided into slow (type 1) or fast-twitch (type 2) based on their contraction speed4,5.

While the nuclei contributing to each myofiber were long thought to be fairly homogeneous, recent single-nucleus transcriptomics has challenged that paradigm6–8. Distinct myonuclear populations were shown to exist within a single skeletal muscle fiber, with transcriptome profiles associated with the specific myofiber type or with neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions. These observations suggest a complex regulation of gene expression and 3D coordination within the myofiber syncytium. Unfortunately, the tissue dissociation protocols associated with single-nucleus RNA sequencing result in loss of spatial information and might result in aberrant gene expression due to stress in response to the dissociation protocol9. Even though these methods are used in combination with imaging techniques, the broad spatial organization of most myonuclei types remains unknown. Spatial omics approaches based on in situ sequencing and MSI have demonstrated organization of myofiber type-related genes and metabolites within specific tissue sections10–13, but the degree of spatial compartmentalization and 3D organization has not been explored at the whole tissue level.

In this study, our newly developed spatial multi-omics approach combining RNA tomography (TOMOseq) spatial transcriptomics14 with mass spectrometry imaging (MSI)-based spatial metabolomics and lipidomics12 enables deeper molecular analysis of whole murine TA muscles. Through this approach, we delineated the gene expression patterns and metabolic landscape at the full tissue level. We demonstrated a specific regionalization of gene expression and metabolites related to the glycolytic and oxidative potential of myofibers. We further characterize by immunofluorescence the variation in the proportion of different fiber types along the proximal-distal axis of TA, extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and soleus (SOL) muscles. Our multi-dimensional analysis of gene expression, myofiber types and metabolic activity demonstrates that skeletal muscle is a highly coordinated tissue with dedicated metabolism restricted to specific compartments within the tissue.

Results

Regionalization of gene expression patterns along the proximal-distal axis of homeostatic TA muscles

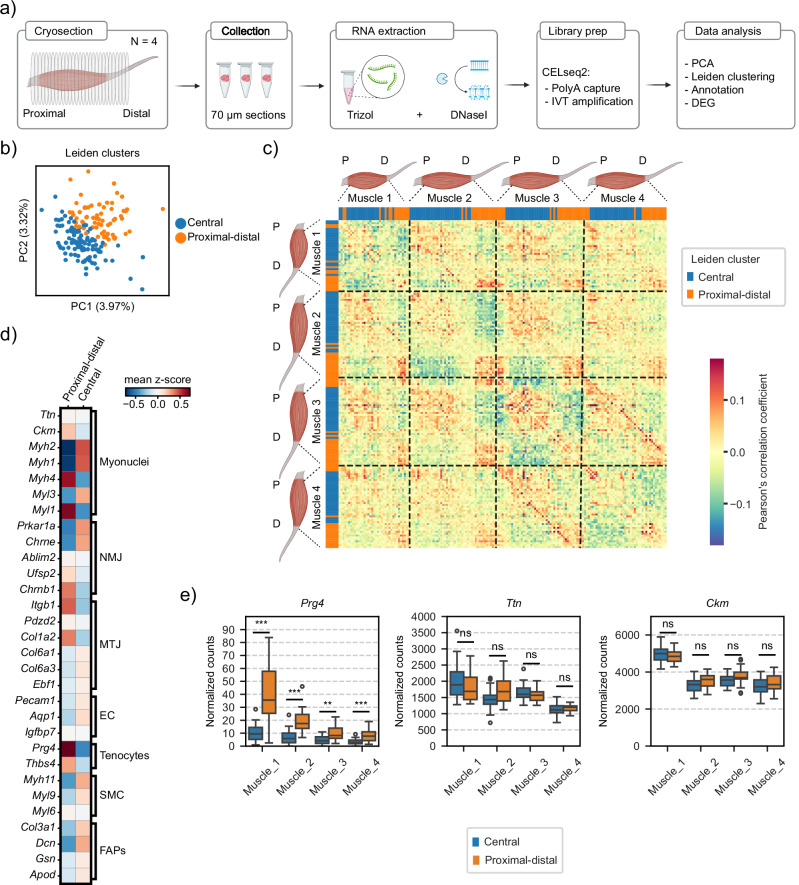

To examine the spatial distribution of transcripts across an entire muscle, we applied TOMOseq14 to TA muscles of 4- to 6-month-old mice. In this approach, entire TAs were cryosectioned along the proximal-distal axis, after which RNA was extracted and sequenced from different sections (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1, “Methods”). To investigate global gene expression patterns in our dataset, we selected the genes detected in more than four transcripts in at least three consecutive sections in all replicates (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Principal component analysis (PCA, Supplementary Fig. 1c) confirmed that batch effects (different muscles, different experiments) did not influence the PC1 and PC2 coordinates (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Instead, we observed that sections from the same anatomical region between different muscles clustered together along the PC1 and PC2 axes (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Further unsupervised Leiden clustering analysis based on the PCA, and the k-nearest neighbors’ algorithm (“Methods”) revealed a distinct separation of the sections into two groups based on their anatomical location: one consisting of the proximal-distal sections, and the other comprising the central sections (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1f and Supplementary Data 1).

Fig. 1. Spatial organization of transcripts in homeostatic TA muscles.

a Summary of TOMOseq experimental procedure: muscles were cryosectioned perpendicularly along the proximal-distal axis into 70 μm slices, and each slice was collected in a different tube. RNA extraction was performed for each tube, followed by library preparation, sequencing and data analysis. b Scatterplots after PCA displaying n = 171 sections. Sections are colored by Leiden cluster annotation (Supplementary Data 1). c Pairwise correlation heatmap of individual sections among all genes detected at more than four transcripts in at least three consecutive sections (Supplementary Data 1). Sections are colored by Leiden cluster annotation. d Mean z-score of unique transcript counts of marker genes for specialized myogenic nuclei (body myonuclei, NMJ and MTJ) and non-myogenic cells (ECs, tenocytes, SMCs and FAPs) in the two groups of sections. e Distribution of normalized transcript counts of one tenocyte marker (Prg4) and two muscle markers (Ttn and Ckm) in the two clusters of sections for each muscle. Sections are grouped and colored by Leiden cluster annotation. Box plot characteristics: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Two-side t-test and adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini–Hochberg correction, ***p = 1.23e−05 (Muscle 1), ***p = 1.19e−06 (Muscle 2), **p = 6.70e−04 (Muscle 3), ***p = 2.87e−04 (Muscle 4). Diagrams in (a) and muscle diagrams in (c) were created with BioRender.com. P proximal, D distal, IVT in vitro transcription, PCA principal component analysis, DEG differential gene expression, MTJ myotendinous junction, NMJ neuromuscular junction.

Next, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for every pairwise combination of sections irrespective of the muscle they originated from (Supplementary Data 1). As expected, adjacent sections were better correlated than sections that were spaced further apart. Individual muscles displayed two or three sets of adjacent sections showing a positive correlation with each other and delineating the tissues into three anatomical areas: proximal, central, and distal (Fig. 1c). Their spatial positions roughly corresponded to the knee myotendinous junction, the central muscle body, and the ankle myotendinous junction, respectively. Despite variability in the recovery of proximal sections due to difficulties in dissecting the tendon from the knee junction, both ends of the muscles were positively correlated to each other on Muscles 1 and 3. Additionally, sections from the same anatomical region from different muscles exhibited high correlation independently of the muscle source (Fig. 1c). We further confirmed this observation by performing a hierarchical cluster analysis based on the Pearson correlation coefficients. In agreement with the PC-based clustering, this approach grouped sections based on their anatomical region rather than the muscle from which they originated (Supplementary Fig. 2). Altogether, these results suggest that TA muscles can be anatomically sub-divided into three main regions, hereafter named proximal, central, and distal, and two transcriptomic regions characterized by a specific molecular profile defined by their distinct gene expression patterns.

To characterize the two distinct transcriptomic profiles, we explored the presence of previously described markers of non-myogenic cells (tenocytes, endothelial cells (ECs), smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs))15–17, and specialized myonuclei subtypes (body myonuclei, myotendinous junction and neuromuscular junction myonuclei)6–8 (Fig. 1d). As expected, there was an enrichment of neuromuscular junction markers in the central sections. Additionally, Prg4 expression was enriched in proximal-distal sections (Fig. 1e) suggesting the presence of tenocytes in these sections18. In both the proximal and distal ends of the TAs we did not recover sections with tendon identity, likely due to the large differences in size of the cross-sectional area between the muscle and tendon in the ankle, resulting in inefficient RNA extraction from smaller sections and insufficient signal-to-noise ratio in transcript counts (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Indeed, both proximal-distal and central sections displayed a predominant muscle identity with no significant difference in the expression levels of the two canonical muscle markers Ttn and Ckm (Fig. 1e), a clear indication that most transcripts within the sections were from muscle fiber origin. However, other myofiber transcripts displayed heterogeneous distribution between central and proximal-distal sections. These results demonstrate that the two distinct groups of sections were not only characterized by the heterogeneous distribution of previously known regionalized transcripts related to myotendinous (Col1a2, Itgb1, Prg4 and Thbs4) and neuromuscular junctions (Prkar1a, Chrne and Chrnb1), but also by an unexpectedly distinct distribution of genes related to fiber types (Myh2, Myh1, Myh4, Myl3 and Myl1).

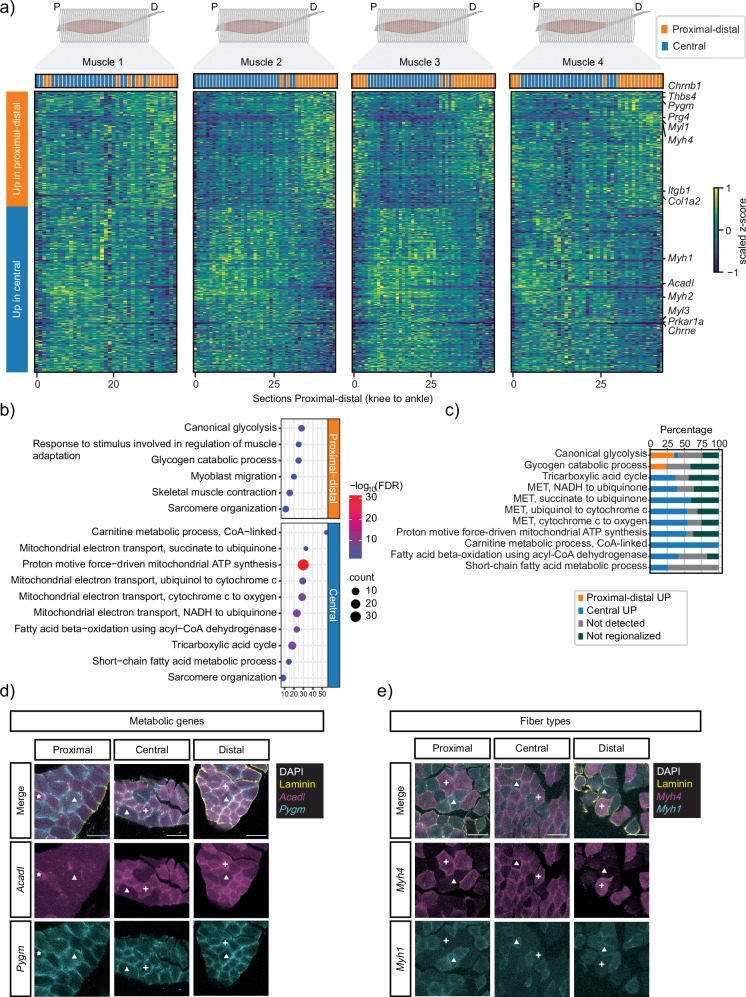

TOMOseq reveals two spatial compartments with different metabolic programs

To further understand whole tissue gene expression patterns, we performed differential gene expression analysis between the two groups of sections (Supplementary Data 1, “Methods”). In central sections, 405 genes were enriched and 281 in proximal-distal sections. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) shared consistent expression patterns along the proximal-distal axis across the four TA muscles (Fig. 2a). In proximal-distal sections, enriched genes were related to glycolytic fiber types (Myh4 and Myl1), the myotendinous junction (Prg4, Thbs4, Itgb1 and Col1a2) and glycolytic metabolism (Pygm). Central sections stood out by the expression of markers for oxidative fiber types (Myh1, Myh2 and Myl3), neuromuscular junction-related genes (Prkar1a and Chrne) and oxidative metabolism (Acadl). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis19–21 revealed that genes enriched in the proximal-distal sections were associated to physiological processes including glycolysis, skeletal muscle contraction, and glycogen metabolism (Fig. 2b). In central sections, the most significantly enriched biological processes were related to the fatty acid metabolism, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, the electron chain transport and mitochondrial ATP production. To further investigate the spatial organization of GO terms, we selected some of the terms related to metabolic processes in Fig. 2b and, for each, we classified their annotated genes in four categories (up-regulated in proximal-distal, up-regulated in central, not detected and not regionalized; Fig. 2c). We found that most of the genes in each GO term were only enriched in one of the two groups of sections. Taken together, these results demonstrate that spatio-differentially expressed genes are related to fiber type and metabolic activity. Since myofiber types differ in their metabolic energy production pathways4,5, these results suggest a distinct, spatial organization of fiber type proportions along the length of TA muscles, where proximal and distal areas are enriched in glycolytic Myh4 myofibers, whereas central sections display enrichment in oxidative Myh1 and Myh2 myofibers.

Fig. 2. Differential gene expression analysis between proximal-distal and central areas of TA muscles.

a Heat maps display the average proximal–distal expression patterns of the 686 DEG between proximal/distal and central sections detected by TOMOseq in each muscle. Genes were clustered based on the proximal-distal expression pattern. b GO-term analysis for the DEGs shown in (a). c Bar chart displays the percentage of genes that are differentially expressed between the clusters of sections, not regionalized, or not detected from selected GO categories in (b). HCR RNA-FISH for metabolic (d) and fiber type (e) genes identified by TOMOseq on proximal, central, and distal sections. Gray, DAPI; yellow, laminin subunit α-1. Scale bar, 50 μm. d White triangles indicate expression of Pygm; white crosses indicate expression of Acadl and Pygm; white stars indicate expression of Acadl. e White triangles and crosses indicate expression of Myh1 and Myh4, respectively. Muscle diagrams in (c) were created with BioRender.com. P proximal, D distal, MET mitochondrial electron transport, FDR false discovery rate.

To validate the presence of regionalized fiber type and metabolism-related genes in different fibers, we performed RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (HCR™ RNA-FISH) on sections from proximal, central, and distal areas of TAs. We first selected Acadl and Pygm as markers for oxidative and glycolytic metabolism, respectively. In the three different areas of the muscle, a subset of myofibers expressed exclusively the glycolytic marker Pygm (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3a, c). The majority of remaining myofibers expressed both Pygm and Acadl, and only a few fibers expressed solely Acadl (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3a, c). Subsequently, to confirm the presence of different fiber types along the proximal-distal axis of TA identified by TOMOseq (Fig. 2a), we performed HCRTM RNA-FISH22 for Myh4 (enriched in the proximal-distal cluster) and Myh1 (enriched in the central cluster) on different areas of the muscle. Both MyHC isoforms were detected in the different regions of the muscle and, additionally, their expression was largely restricted to distinct fibers (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Our results confirm previous reports7,23 of coordinated expression of MyHC isoforms together with metabolic-related genes within the same myofibers in TA muscles. These further suggest that gene expression patterns along the proximal-distal axis of the TA arise from differences in fiber type proportions along the length the muscle.

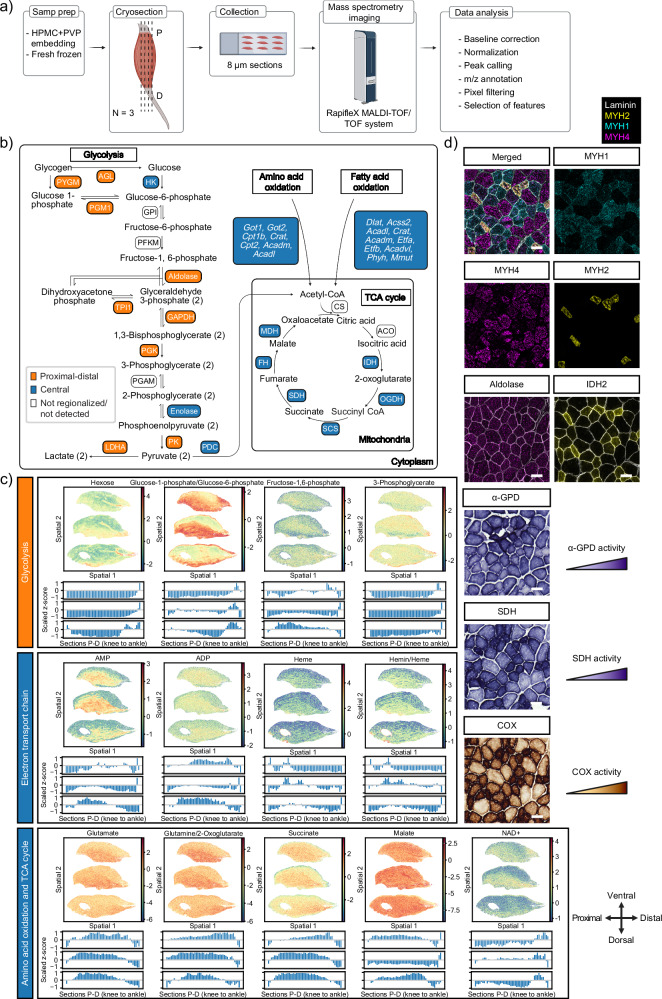

Mass spectrometry imaging confirms distinct distribution of energy-producing metabolic pathways

We then sought to confirm the spatial delineation of distinct metabolic areas within the muscle by performing matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-MSI. This technique enables sensitive, specific, and spatially correlated detection of metabolites and lipids via mass spectrometry12,13. We used MALDI-MSI on longitudinal sections of three TA muscles from 4- to 6-month-old mice to capture differences in the spatial distribution of metabolites and lipids because in these sections we can find regions from the proximal, central and distal end of each muscle (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Data 2, “Methods”). We focused on analyzing regionalized metabolites associated with ATP-producing pathways (Fig. 3b), which exhibited differential expression in the spatial transcriptomic dataset (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Among all the putative annotations of the regionalized metabolites (Supplementary Data 3), we tentatively identified multiple regionalized metabolites from glycolysis (hexose, glucose-1-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6-phosphate, and 3-phosphoglycerate), TCA cycle (2-oxoglutarate, succinate, malate and NAD+), electron transport chain (AMP, ADP, hemin and heme), and amino acid oxidation (glutamine and glutamate) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 1). Besides the expected proximal-distal regionalization, we also observed a marked differential distribution of metabolites between the dorsal and ventral regions. This regionalization is most likely a result of differential distribution of fiber types on the dorsal-ventral axis in TAs24 (Supplementary Fig. 6). As a consequence, this introduced a strong source of variability in metabolite distribution and masked any effects of differences in metabolites along the proximal-distal axis. Therefore, to integrate the spatial metabolomics results with our spatial transcriptomic data, we binned the MALDI-MSI data and created a pseudobulk mass spectrometry dataset along the proximal-distal axis (methods) that was parallel to our TOMOseq sections. Although the in silico reconstruction of MALDI-MSI sections along the proximal-distal axis only contained a subset of fibers in comparison to a TOMOseq section, we were able to recover the expected patterns of the different metabolites according to our spatial transcriptomics results. Overall, in the proximal-distal area of the tissue the intensity of tentatively identified glycolysis metabolites increased, while intensities of tentatively identified TCA cycle, electron chain and amino acid oxidation metabolites decreased (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Mass spectrometry imaging on longitudinal sections of TA muscles.

a Summary of MALDI-MSI experimental procedure: muscles were cryosectioned longitudinally along the proximal-distal axis into 8 μm slices. Sections were processed with a rapifleX MALDI-TOF/TOF system (Bruker Daltonics) and solariX 15 T MALDI-2xR-FTICR and spatial distribution maps of metabolites and lipids were reconstructed. b Scheme of different metabolic pathways identified by TOMOseq. Colors indicate in what cluster the enzyme (capitals), or gene (italics) is enriched based on the DEG analysis of TOMOseq data. c Heatmaps and in silico TOMOseq from MALDI-MSI display spatial distribution of identified metabolites from glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, electron transport chain and amino acid oxidation in three different muscles (top to bottom: Muscle 1, Muscle 2, and Muscle 3). Color bar indicates the z-score of the log10 transformed normalized intensity values. Black arrows display proximal-distal (spatial 1) and dorsal-ventral (spatial 2) orientation of the tissue sections. d Immunofluorescence and histochemistry stainings to characterize the glycolytic and oxidative capacity of different fiber types on consecutive TA cryosections. Scale bar, 50 μm. Images in (a) and (b) were created with BioRender.com. P proximal, D distal, ACADL, ACADM, ACADVL acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase, ACO aconitase, ACSS2 acyl-Coenzyme A synthetase, AGL glycogen debranching enzyme, CPT1B CPT2, carnitine palmitoyltransferase, CRAT carnitine o-acetyltransferase, CS citrate synthase, DLAT dihydrolipoamide s-acetyltransferase, ETFA, ETFB electron transfer flavoprotein, FH fumarate hydratase, GAPDH glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GOT1, GOT2 aspartate aminotransferase, GPI glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, HK hexokinase, IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase, LDHA lactate dehydrogenase-A, MDH malate dehydrogenase, MMUT methylmalonyl Coenzyme A mutase, OGDH oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, PDC pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, PFKM phosphofructokinase, PGAM phosphoglycerate mutase, PGK phosphoglycerate kinase, PGM1 phosphoglucomutase, PHYH phytanoyl-Coenzyme A hydroxylase, PK pyruvate kinase, PYGM glycogen phosphorylase, SDH succinate dehydrogenase, SCS succinyl Coenzyme A synthetase, TPI1 Triosephosphate Isomerase, α-GPD α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, COX cytochrome c oxidase.

To further validate the annotation of the tentatively identified features, we performed histochemistry and immunofluorescence assays of two glycolytic enzymes (aldolase and α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, α-GPD), two TCA enzymes (succinate dehydrogenase, SDH, and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2, IDH2) and one component of the electron chain complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase, COX). To ensure the compatibility of MALDI-MSI with histological tissue characterization methods on consecutive tissue sections, we applied a tissue embedding technique based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)25. To assess the glycolytic potential of the different fibers, we performed a α-GPD activity assay, which overlapped with the patterns observed in the MALDI-MSI data (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Additionally, we observed a strong overlap between the feature tentatively annotated as succinate (Fig. 3c) and the activity of the upstream TCA cycle enzyme SDH (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We also detected a strong correlation of electron chain transport metabolites (Fig. 3c) with the COX reactivity assay (Supplementary Fig. 7c) and an increased abundance of blood vessels and capillaries (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Furthermore, immunostainings for the glycolytic enzyme aldolase and TCA cycle enzyme IDH2 reproduced the spatial organization of their metabolic substrate fructose-1,6-phosphate and product 2-oxoglutarate, respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). Taken together, these observations support our tentative identification of the regionalized metabolites in TA muscles. In agreement with previous reports24, myofiber types appeared to be heterogeneously distributed along the dorsal-ventral axis, which resulted in intensity differences of metabolites in multiple body axes (Supplementary Fig. 7g). By combining MALDI-MSI with histological characterization of tissues, we demonstrate that the spatially restricted metabolic areas are associated to the difference in glycolytic and oxidative capacity of different fibers (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, we confirmed previously reported12,13,26 differences in the chemical composition of myofiber types (Supplementary Fig. 8). Altogether, these results further demonstrate that metabolites are enriched in specific fiber types and suggest regionalization of glycolytic fibers in ventral and proximal-distal areas of the TA muscle, while oxidative fibers are preferentially localized in dorsal and central areas.

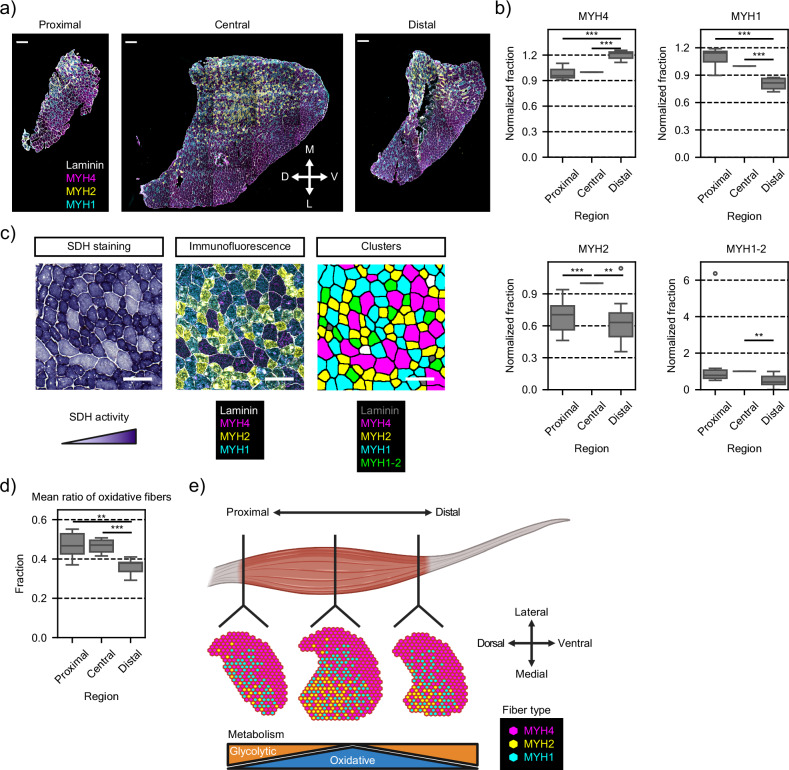

Heterogeneous contribution of fiber types along the proximal-distal axis of TAs

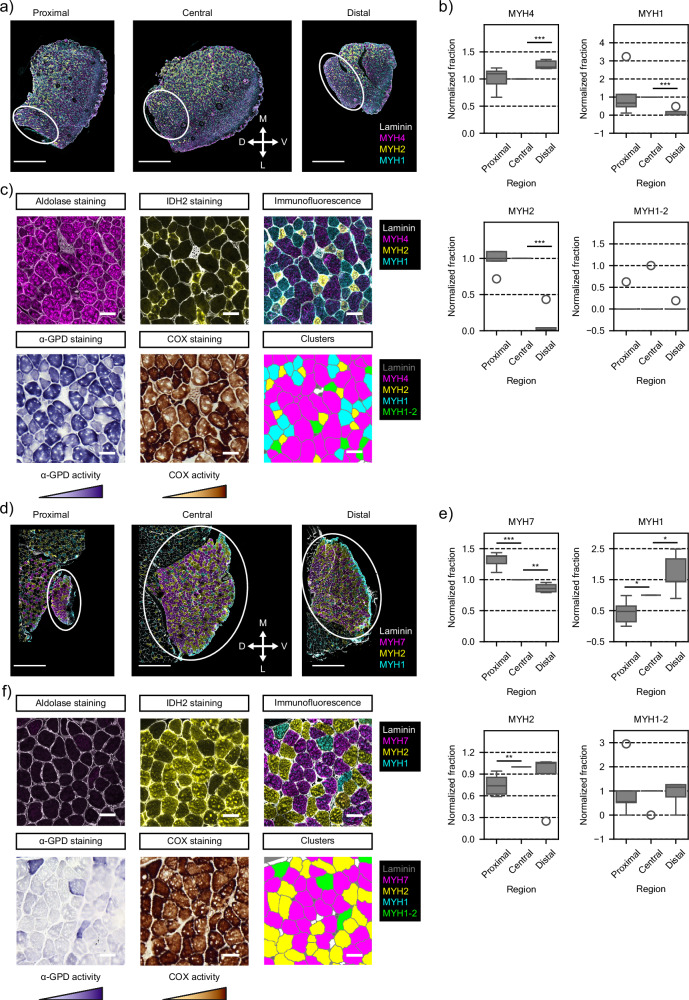

To further characterize the heterogeneity in fiber type proportions along proximal-distal without biases introduced by dorsal-ventral regionalization, we performed multiplex immunofluorescence staining of the MyHC isoforms detected by TOMOseq (Myh4, Myh2 and Myh1) on cross-sections from the three different areas of the muscle (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). In line with our staining on longitudinal sections and published results24, we observed enrichment of MYH1 and MYH2 fibers on the dorsal side of the muscle. To compare the proportions of fiber types between the three areas, myofiber type composition on each section was quantified using a previously published pipeline27. We detected three types of myofibers expressing one MyHC isoform (MYH4, MYH2 or MYH1) and one hybrid myofiber type expressing both MYH1 and MYH2 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9b, c), which is in accordance with previously reported fiber types in TAs28,29. While these studies also reported the presence of a small proportion of hybrid MYH1 and MYH4 fibers in TAs, we did not recover this group of fibers in our analysis. This could be due to the different antibodies used to label MYH4 fibers or that the low percentage of double positive MYH1 and MYH4 fibers was insufficient to classify these fibers in a separate group in our non-supervised clustering analysis. In line with our transcriptomic, metabolomic and lipidomic data, we found significant differences in relative proportions of myofiber types in proximal, central, and distal sections of TA muscles (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Fiber type characterization along the proximal-distal axis of TAs.

a Immunofluorescence staining of representative cryosections from proximal, central, and distal regions of TA muscles used for quantification of fiber types. White arrows display medial-lateral and dorsal-ventral orientation of the tissue sections. Yellow, type 2a myofiber (MYH2); cyan, type 2x myofiber (MYH1); magenta, type 2b myofiber (MYH4); gray, laminin subunit α-1. Scale bar, 300 μm. D dorsal, V ventral, M medial, L lateral. b Distribution of normalized fractions of the four different fiber types (MYH4, MYH1, MYH2 and MYH1-2) across seven replicates (Muscle 1, n = 3; Muscle 2, n = 2; Muscle 3, n = 2). For each replicate, central sections were used as reference for normalization. Box plot characteristics: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Two-side t-test, ***p = 5.00e−05 (MYH4 proximal vs. distal), ***p = 1.14e−06 (MYH4 central vs. distal), ***p = 8.17e−05 (MYH1 proximal vs. distal), ***p = 4.57e−06 (MYH1 central vs. distal), ***p = 6.05e−04 (MYH2 proximal vs. central), **p = 4.68e−03 (MYH2 central vs. distal), **p = 2.16e−03 (MYH1-2 central vs. distal). c Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) staining analysis for oxidative capacity on TA muscle (left panel); immunofluorescence staining for fiber types of consecutive cryosections (middle panel); and, assigned fiber type based on clustering analysis of the immunofluorescence staining (right panel). Scale bar, 100 μm. d Distribution of oxidative fibers ratios (MYH2, MYH1 and MYH1-2) across seven replicates (Muscle 1, n = 3; Muscle 2, n = 2; Muscle 3, n = 2). Box plot characteristics: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Two-side t-test, **p = 4.58e−03 (proximal vs. distal), ***p = 5.22e−04 (central vs. distal). e Schematic representation of the heterogeneous distribution of fiber types and metabolism along the three body axes of TA muscles. Images in (e) were created with BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Quantification of fiber types across proximal, central, and distal TA sections used for fiber type quantification analysis

| Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fiber type cluster | Proximal | Central | Distal | Total |

| data_m1_rep1 | MYH1 | 298 (47.38%) | 1280 (41.30%) | 414 (31.44%) | 1992 (39.48%) |

| MYH2 | 23 (3.66%) | 161 (5.20%) | 42 (3.19%) | 226 (4.48%) | |

| MYH4 | 282 (44.83%) | 1526 (49.24%) | 814 (61.81%) | 2622 (51.97%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 26 (4.13%) | 132 (4.26%) | 47 (3.57%) | 205 (4.06%) | |

| Total | 629 (12.47%) | 3099 (61.43%) | 1317 (26.11%) | 5045 | |

| data_m1_rep2 | MYH 1 | 454 (44.12%) | 1207 (37.10%) | 331 (30.23%) | 1992 (37.05%) |

| MYH2 | 67 (6.51%) | 296 (9.10%) | 63 (5.75%) | 426 (7.92%) | |

| MYH4 | 483 (46.94%) | 1628 (50.05%) | 676 (61.74%) | 2787 (51.83%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 25 (2.43%) | 122 (3.75%) | 25 (2.28%) | 172 (3.20%) | |

| Total | 1029 (19.14%) | 3253 (60.50%) | 1095 (20.36%) | 5377 | |

| data_m1_rep3 | MYH1 | 477 (43.96%) | 1178 (37.49%) | 334 (32.12%) | 1989 (37.76%) |

| MYH2 | 61 (5.62%) | 206 (6.56%) | 43 (4.13%) | 310 (5.89%) | |

| MYH4 | 514 (47.37%) | 1599 (50.89%) | 646 (62.12%) | 2759 (52.38%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 33 (3.04%) | 159 (5.06%) | 17 (1.63%) | 209 (3.97%) | |

| Total | 1085 (20.60%) | 3142 (59.65%) | 1040 (19.75%) | 5267 | |

| data_m2_rep1 | MYH1 | 337 (34.89%) | 884 (31.07%) | 141 (27.17%) | 1362 (31.45%) |

| MYH2 | 70 (7.25%) | 312 (10.97%) | 46 (8.86%) | 428 (9.88%) | |

| MYH4 | 521 (53.93%) | 1506 (52.93%) | 306 (58.96%) | 2333 (53.88%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 38 (3.93%) | 143 (5.03%) | 26 (5.01%) | 207 (4.78%) | |

| Total | 966 (22.31%) | 2845 (65.70%) | 519 (11.99%) | 4330 | |

| data_m2_rep2 | MYH1 | 297 (39.65%) | 900 (34.68%) | 155 (30.27%) | 1352 (35.06%) |

| MYH2 | 35 (4.67%) | 129 (4.97%) | 29 (5.66%) | 193 (5.01%) | |

| MYH4 | 399 (53.27%) | 1444 (55.65%) | 318 (62.11%) | 2161 (56.04%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 18 (2.40%) | 122 (4.70%) | 10 (1.95%) | 150 (3.89%) | |

| Total | 749 (19.42%) | 2595 (67.30%) | 512 (13.28%) | 3856 | |

| data_m3_rep1 | MYH1 | 352 (34.82%) | 1280 (38.82%) | 260 (27.87%) | 1892 (36.10%) |

| MYH2 | 17 (1.68%) | 120 (3.64%) | 13 (1.39%) | 150 (2.86%) | |

| MYH4 | 637 (63.01%) | 1883 (57.11%) | 659 (70.63%) | 3179 (60.66%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 5 (0.49%) | 14 (0.42%) | 1 (0.11%) | 20 (0.38%) | |

| Total | 1011 (19.29%) | 3297 (62.91%) | 933 (17.80%) | 5241 | |

| data_m3_rep2 | MYH1 | 383 (36.37%) | 1257 (37.51%) | 241 (27.80%) | 1881 (35.69%) |

| MYH2 | 19 (1.80%) | 130 (3.88%) | 12 (1.38%) | 161 (3.05%) | |

| MYH4 | 641 (60.87%) | 1959 (58.46%) | 614 (70.82%) | 3214 (60.98%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 10 (0.95%) | 5 (0.15%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (0.28%) | |

| Total | 1053 (19.98%) | 3351 (63.57%) | 867 (16.45%) | 5271 | |

Absolute numbers of each fiber type or total number of fibers per region are shown in each cell. Percentages of different fiber types in each region or percentage of fibers across different regions are shown in brackets.

Because both spatial transcriptomics and spatial metabolomics datasets revealed regionalization of oxidative and glycolytic metabolic pathways, we re-analyzed the different fiber types based on their oxidative potential measured by enzymatic activity of succinic dehydrogenase (SDH) into oxidative (MYH2, MYH1 and MYH1-2) or glycolytic (MYH4) fibers (Fig. 4c). We found that the proportion of oxidative fibers was significantly decreased in distal sections compared to central sections (Fig. 4d). Additionally, other sarcomere components known to be enriched in different fiber types30 were similarly differentially expressed in our spatial transcriptomic data (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Taken together, these results confirm our hypothesis of differential fiber type distribution along the length of TA.

Identification of similar metabolic compartments associated with fiber type distribution along the proximal-distal axis of EDL and SOL

In line with our experiments, TA muscle is considered a fast-twitch muscle and is mainly composed of type 2 fibers. In mice, the EDL muscle contains only type 2 fibers and is known to be the most glycolytic and fast-twitch muscle31. In contrast, the SOL muscle is mainly composed of slow type 1 fibers and oxidative type 2 fibers. The different fiber-type composition of these three muscles offers the possibility of a comprehensive analysis of fiber types distribution and metabolic compartments in muscles with different functions and architectures. Therefore, to explore the extent of regionalization beyond the TA muscle we performed multiplex immunofluorescent stainings for MyHC in EDL and SOL. In accordance with previously reported data31, we detected three types of myofibers expressing one MyHC isoform (MYH4, MYH2 or MYH1) and one hybrid myofiber type expressing both MYH1 and MYH2 in EDLs (Fig. 5a and Table 2). For the SOL, in line with previous studies28,31, we detected three types of myofibers expressing one MyHC isoform (MYH7, MYH2 or MYH1) and one hybrid myofiber type characterized by the expression of both MYH1 and MYH2 (Fig. 5d and Table 3).

Fig. 5. Fiber type characterization along the proximal-distal axis of EDLs and SOLs.

Immunofluorescence staining of representative cryosections from proximal, central, and distal regions of EDL (a) and SOL (d) muscles used for quantification of fiber types. White arrows display medial-lateral and dorsal-central orientation of the tissue sections. Circles surround the muscle of interest. Yellow, type 2a myofiber (MYH2); cyan, type 2x myofiber (MYH1); magenta, type 2b (MYH4) or type 1 myofiber (MYH7); gray, laminin subunit α-1. Scale bar, 1000 μm. D dorsal, V ventral, M medial, L lateral. b Distribution of normalized fraction of the four different fiber types (MYH4, MYH1, MYH2 and MYH1-2) across 5 EDL replicates (Muscle 1, n = 1; Muscle 2, n = 2; Muscle 3, n = 2). For each replicate, central sections were used as reference for normalization. Box plot characteristics: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Two-side t-test, ***p = 8.06e−05 (MYH4 central vs. distal), ***p = 1.21e−05 (MYH1 central vs. distal), ***p = 5.09e−06 (MYH2 central vs. distal). e Distribution of normalized fraction of the four different fiber types (MYH7, MYH1, MYH2 and MYH1-2) across 5 SOL replicates (Muscle 1, n = 2; Muscle 2, n = 1; Muscle 3, n = 2). For each replicate, central sections were used as reference for normalization. Box plot characteristics: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Two-side t-test, ***p = 5.80e−04 (MYH7 proximal vs. central), **p = 2.87e−03 (MYH7 central vs. distal), **p = 5.72e−03 (MYH2 proximal vs. central), *p = 1.47e−02 (MYH1 proximal vs. central), *p = 4.26e−02 (MYH1 central vs. distal). Histochemistry and immunofluorescence staining for oxidative and glycolytic potential of fibers on consecutive cryosections of EDL (c) and SOL (f), and assigned fiber type based on clustering analysis of the immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Table 2.

Absolute number of fiber types across proximal, central, and distal EDL sections used for fiber type quantification analysis

| Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fiber type cluster | Proximal | Central | Distal | Total |

| data_m1_rep1 | MYH1 | 37 (14.80%) | 153 (22.08%) | 62 (10.63%) | 252 (16.51%) |

| MYH2 | 22 (8.80%) | 85 (12.27%) | 31 (5.32%) | 138 (9.04%) | |

| MYH4 | 184 (73.60%) | 424 (61.18%) | 485 (83.19%) | 1093 (71.63%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 7 (2.80%) | 31 (4.47%) | 5 (0.86%) | 43 (2.82%) | |

| Total | 250 (16.38%) | 693 (45.41%) | 583 (38.20%) | 1526 | |

| data_m2_rep1 | MYH1 | 211 (40.11%) | 211 (12.40%) | 8 (0.46%) | 430 (10.80%) |

| MYH2 | 24 (4.56%) | 71 (4.17%) | 1 (0.06%) | 96 (2.41%) | |

| MYH4 | 291 (55.32%) | 1420 (83.43%) | 1743 (99.49%) | 3454 (86.78%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 0 (%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) | |

| Total | 526 (13.22%) | 1702 (42.76%) | 1752 (44.02%) | 3980 | |

| data_m2_rep2 | MYH1 | 89 (23.18%) | 272 (20.16%) | 5 (0.36%) | 366 (11.72%) |

| MYH2 | 34 (8.85%) | 69 (5.11%) | 3 (0.22%) | 106 (3.39%) | |

| MYH4 | 261 (67.97%) | 1008 (74.72%) | 1382 (99.42%) | 2651 (84.89%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 384 (12.30%) | 1349 (43.20%) | 1390 (44.51%) | 3123 | |

| data_m3_rep1 | MYH1 | 21 (6.82%) | 217 (14.63%) | 2 (0.28%) | 240 (9.58%) |

| MYH2 | 11 (3.57%) | 53 (3.57%) | 0 (0%) | 64 (2.55%) | |

| MYH4 | 276 (89.61%) | 1213 (81.79%) | 713 (99.72%) | 2202 (87.87%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 308 (12.29%) | 1483 (59.18%) | 715 (28.53%) | 2506 | |

| data_m3_rep2 | MYH1 | 6 (1.50%) | 218 (12.84%) | 17 (2.46%) | 241 (8.64%) |

| MYH2 | 22 (5.50%) | 97 (5.71%) | 0 (0%) | 119 (4.27%) | |

| MYH4 | 372 (93.00%) | 1383 (81.45%) | 673 (97.54%) | 2428 (87.09%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 400 (14.35%) | 1698 (60.90%) | 690 (24.75%) | 2788 | |

Absolute numbers of each fiber type or total number of fibers per region are shown in each cell. Percentages of different fiber types in each region or percentage of fibers across different regions are shown in brackets.

Table 3.

Absolute number of fiber types across proximal, central, and distal SOL sections used for fiber type quantification analysis

| Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fiber type cluster | Proximal | Central | Distal | Total |

| data_m1_rep1 | MYH1 | 3 (2.26%) | 37 (3.48%) | 75 (7.55%) | 115 (5.25%) |

| MYH2 | 28 (21.05%) | 359 (33.74%) | 352 (35.41%) | 739 (33.73%) | |

| MYH7 | 92 (69.17%) | 513 (48.21%) | 458 (46.08%) | 1063 (48.52%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 10 (7.52%) | 155 (14.57%) | 109 (10.97%) | 274 (12.51%) | |

| Total | 133 (6.07%) | 1064 (48.56%) | 994 (45.37%) | 2191 | |

| data_m1_rep2 | MYH1 | 1 (0.64%) | 41 (4.39%) | 26 (3.93%) | 68 (3.88%) |

| MYH2 | 42 (26.75%) | 338 (36.19%) | 254 (38.43%) | 634 (36.19%) | |

| MYH7 | 100 (63.69%) | 472 (50.54%) | 307 (46.44%) | 879 (50.17%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 14 (8.92%) | 83 (8.89%) | 74 (11.20%) | 171 (9.76%) | |

| Total | 157 (8.96%) | 934 (53.31%) | 661 (37.73%) | 1752 | |

| data_m2_rep1 | MYH1 | 36 (19.67%) | 181 (19.89%) | 297 (28.75%) | 514 (24.18%) |

| MYH2 | 90 (49.18%) | 475 (52.20%) | 489 (47.34%) | 1054 (49.58%) | |

| MYH7 | 57 (31.15%) | 254 (27.91%) | 247 (23.91%) | 558 (26.25%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 183 (8.61%) | 910 (42.80%) | 1033 (48.59%) | 2126 | |

| data_m3_rep1 | MYH1 | 0 (%) | 11 (1.39%) | 34 (3.46%) | 45 (2.33%) |

| MYH2 | 62 (39.74%) | 368 (46.52%) | 489 (49.75%) | 919 (47.62%) | |

| MYH7 | 82 (52.56%) | 302 (38.18%) | 302 (30.72%) | 686 (35.54%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 12 (7.69%) | 110 (13.91%) | 158 (16.07%) | 280 (14.51%) | |

| Total | 156 (8.08%) | 791 (40.98%) | 983 (50.93%) | 1930 | |

| data_m3_rep2 | MYH1 | 14 (6.45%) | 121 (13.55%) | 169 (19.40%) | 304 (15.35%) |

| MYH2 | 57 (26.27%) | 398 (44.57%) | 97 (11.14%) | 552 (27.86%) | |

| MYH7 | 108 (49.77%) | 321 (35.95%) | 248 (28.47%) | 677 (34.17%) | |

| MYH1-2 | 38 (17.51%) | 53 (5.94%) | 357 (40.99%) | 448 (22.61%) | |

| Total | 217 (10.95%) | 893 (45.08%) | 871 (43.97%) | 1981 | |

Absolute numbers of each fiber type or total number of fibers per region are shown in each cell. Percentages of different fiber types in each region or percentage of fibers across different regions are shown in brackets.

Similar to our results in TA muscles, we found significant differences in relative proportions of myofiber types in proximal, central, and distal sections of EDL (Fig. 5b) and SOL muscles (Fig. 5e). In both muscles, the most oxidative fibers were lost and glycolytic fibers were enriched in the distal end. In contrast, neither EDL or SOL displayed a strong differential distribution of fiber types along the dorsal-ventral or medial-lateral axis as we had observed in TA muscles. Additionally, we confirmed that differences in fiber types resulted in the existence of different metabolic compartments along the proximal-distal axis, in both EDL (Fig. 5c) and SOL (Fig. 5f), by analyzing α-GPD and COX activity, and the presence of aldolase or IDH2 in the different fiber types. As expected, we observed an increase in signal of SDH, COX and IDH2, and a decrease of α-GPD and aldolase in SOL compared to TA and EDL muscles. In summary, these results demonstrate that the proportion of fiber types changes along the length of the proximal-distal axis in both EDL and SOL muscles in a similar manner as it occurred in TA muscles.

Discussion

By integrating spatially resolved multi-omics and myofiber type characterization we revealed that the proportions of myofiber subtypes differ along the length of murine TA, EDL and SOL muscles (Fig. 4e). This resulted in regionalization of metabolic pathways to produce ATP. Fast myofiber types, metabolites and genes related to glycolysis were enriched in proximal and distal areas of both TA and EDL muscles. In the center of these two muscles, there was an enrichment of oxidative myofiber types, metabolites and genes related to the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Regarding the SOL, which has a different composition of fiber types, we detected a loss of slow type 1 fibers and an increase of fast type 2a and type 2x in distal areas of the muscle. In summary, our data suggested an increase of glycolytic fibers near the myotendinous junction of the ankle in both fast and slow muscle types in the murine hindlimb.

In the spatial transcriptomics data, among the differentially expressed genes enriched in central sections of the TA, we identified hemoglobin genes. The detection of these genes could be attributed to differences in blood vessel distribution as suggested by the enrichment of smooth muscle myosins (Myh11, Myl9 and Myl6) and endothelial cell (Pecam1, Aqp1 and Igfbp7) transcripts in central sections of our TOMOseq data (Fig. 1d). In line with previous studies demonstrating that oxidative fiber types have more capillaries associated to them than glycolytic fibers29, we confirmed heterogeneous distribution of blood vessels along the proximal-distal axis of the muscle (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Additionally, we observed an increased abundance of myoglobin in center sections, which is known to be higher expressed in oxidative myofibers to facilitate oxygen transport32. Alternatively, a few studies have reported that hemoglobin can be detected in the mitochondrial fraction of muscle tissue33,34. Unfortunately, our spatial transcriptomics approach cannot establish the cell type expressing hemoglobin because RNA from myofibers and blood vessels is extracted together. Therefore, future work needs to be done to validate the presence of hemoglobin expression in myofibers.

Our experimental setup limited our ability to track single fibers throughout the entire muscle. Consequently, we could not rule out the possibility that myofibers change fiber type along the length of the muscle. Such regionalized expression of different MyHC isoforms within the same fiber has been observed in various muscles in rabbits35,36. Nonetheless, our integrative analysis of multi-omics data with RNA FISH and fiber type composition together with indirect evidence, such as the decrease in the number of fibers at both ends of the muscle (Table 1) and the differences in fiber length in TAs37,38 and human muscles39, suggest that MYH1 and MYH2 myofibers are shorter compared to MYH4 fibers and that these fibers would attach more centrally within the muscle to the knee and ankle tendons40. This hypothesis is further supported by the presence of tenocyte markers, such as Prg4, Col1a2 and Thbs4, in distal sections of our TOMOseq data (Figs. 1e and 2a), which indicates that the tendon is embedded within the muscle at the posterior end.

There is contradictory evidence in the current literature regarding myofiber distribution within a single muscle. In rabbit extraocular muscle, distinct distribution of MyHC isoforms was reported along the length of the muscle36 and the specific superfast extraocular myofibers were restricted to the innervation zone41. In human skeletal muscle biopsies, longitudinal orientation contributed to differential fiber type distribution in extraocular muscles42, but not in the vastus lateralis43. Other reports on in situ spatial transcriptomics10,11 and metabolomics analysis12,13 of skeletal muscle, where sections were only taken from central areas in the tissue, also failed to explore the fiber type contribution across different areas of the muscle. However, in addition to previously reported heterogeneous distribution of fiber types in cross-sections24, we observed variation in proportion of myofiber types within the TA. The discrepancy between the results of these studies could be attributed to variability introduced by the local tissue sampling approaches used, which might have overlooked the full complexity of myofiber distribution at whole-tissue level.

The different outcomes listed above highlight the necessity of collecting information from the entire tissue in order to get a complete 3D reconstruction of gene expression patterns within a single muscle. In our study, the combination of TOMOseq and MALDI-MSI clearly demonstrates how spatial gene expression regulation, myofiber type specification and catabolic activities coincide within a single muscle. Notably, our integrated approach describes how skeletal muscle is highly compartmentalized along the muscle with dedicated metabolism. Fiber type heterogeneity within the same muscle is key to enabling repetitive low-intensity contractions (posture) and quick high-intensity activities (weight-lifting)44. Our results suggest that different myofibers types are organized in time and/or space to coordinate muscle contraction in TA, EDL and SOL muscles. Coordinated contraction would be achieved through fast contraction of long type 2b fibers, followed by shorter slower contracting fiber types (type 2x and 2a), that would result in synchronized muscle movement.

This insight has potential implications for the understanding of degenerative muscle disorders. For example, type 2b myofibers are known to be preferentially affected in many inherited myopathies and muscle-related disorders, as well as in aging, which is associated with muscle weakness4. Even though the molecular mechanism behind the disappearance of type 2b myofibers, and the physiological impact on the overall change in ratio of the myofiber type remains unclear, some reports have demonstrated that enhancing mitochondrial function (vitamin A45, nicotinamide riboside46, trigonelline47 or PGC-1α activation48) promoted fiber switching towards a more oxidative phenotype and restored skeletal muscle function. Understanding the spatial component in gene expression regulation in muscle disorders and aging could provide insights into the molecular pathways involved in modulating myofiber type proportions and potentially contribute to the development of therapies.

Methods

Animals

DCM–Polr2b:m2rtTA (Polr2b–DCM)49 mice (kindly provided by Dr. J. Gribnau) were housed at the animal facility of Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam. Pax7nGFP (Tg(Pax7-EGFP)15Tajb)50 mice (kindly provided by Dr. S. Tajbakhsh, Pasteur Institute Paris, France) were housed at the animal facility of Leiden University Medical Center. 4 to 6-month-old mice used in this research mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The experiments were evaluated and approved by the local animal welfare committee under DEC numbers 11600, AVD11600202013788 and AVD10100202115681.

TOMOseq

TOMOseq was performed as previously described14,51. Briefly, TA muscles were collected from two female Polr2b–DCM mice (muscles 1 and 2) and two male Tg(Pax7-EGFP)15Tajb (muscles 3 and 4). Dissected skeletal muscle tissues were embedded in OCT, frozen in liquid nitrogen chilled isopentane for 30 s and stored at −80 °C. Frozen TA muscles were cryosectioned along the proximal-distal axis in 70 μm slices at −20 °C. Sections were collected in individual low-retention 2 mL tubes and stored at −80 °C until further processing. For RNA extraction, odd sections were incubated in a mix containing 1.5 mL TRIzol™ Reagent (#15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 μL GlycoBlue (#AM9516, Themo Fisher Scientific) and 2 μL 1:50,000 Ambion™ ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (#4456740, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min at room temperature shacking at 2000 rpm. Next, 0.3 mL chloroform (#650498, Sigma) was added, and incubated at room temperature for 3 min and tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. In total, 750 μL of upper aqueous phase was transferred to a clean 1.5 mL tube and 750 μL of isopropanol were added. After overnight incubation at −20 °C, tubes were centrifuged at 7500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to pellet the RNA. The pellet was washed with in ice-cold 75% ethanol, centrifuged at 7500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and air-dried for 5–10 min on ice. Each RNA pellet was eluted in 22 μL of nuclease-free water and transferred to a 96-well plate. To remove DNA contamination from the sample, 8 μL of DNase mix (5 μL RQ1 DNase I and 3 μL 10x buffer; #M6101, Promega) was added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. RNA was purified using 1.8x RNAClean XP beads (#A63987, Beckman Coulter) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Purified RNA was eluted in 10 μL of nuclease-free water and concentration was measured with Qubit™ RNA High Sensitivity (#Q32852, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five ng of RNA in 1 μL of nuclease-free water were transferred to a 96-well plate prefilled with 50 μL mineral oil (#M5904, Merck) and 1 μL CELseq2 primers (with a unique 8 bp barcode for each well). Library preparation was performed by Single Cell Discoveries (TOMOseq service) according to SORTseq52 (robotized CELseq2-based scRNAseq) on 96-well plate format using a Nanodrop II liquid handling platform (GC biotech). Paired-end (75 bp) sequencing was performed on the Illumina next-seq sequencing platform.

Processing TOMOseq data

The first six bases of read 1 contain the unique molecular identifier and the next eight bases contain the cell or section barcode, while read 2 contains the transcript information. Reads 2 with a valid cell or section barcode were selected, trimmed using TrimGalore (v.0.6.6) with default parameters, and mapped using STAR (v.2.7.7a) with default parameters to the mouse GRCm38 genome (Ensembl 102). Only reads mapping to gene bodies (exons or introns) were used for downstream analysis. For each section, the number of transcripts was obtained as previously described52. We refer to transcripts as unique molecules based on unique molecular identifier correction.

Sections were removed based on their total transcript counts (Muscle 1 < 1e5, Muscle 2 < 1e4.85, Muscle 3 < 1e4.9, Muscle 4 < 1e5, Supplementary Fig. 1f). Genes linked to mapping errors (Kcnq1ot1, Mir5109, Lars2 and Malat1)53, spike-ins, ribosomal genes, low detected genes (fewer than four unique transcripts in three consecutive sections) and genes with saturated unique molecular identifier counts were excluded from downstream analysis. For each muscle, data was normalized to the median number of unique transcript counts per section. To assess reproducibility between biological replicates, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed on the total sum of unique transcript counts from all sections from the same muscle for all pairs of replicates (Supplementary Fig. 1a). To integrate the data from the different muscles, gene expression values in each sample dataset were transformed to z-scores within sample sections and a count table was created for all the shared genes across the four muscles. PCA was performed on the z-score transformed data using the Scanpy package (v.1.9.3)54 treating sections as single cells. The first 16 PCs were used to compute the k-nearest neighbors (k = 65) with Euclidian distances and Leiden clusters (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Supplementary Data 1). Annotation of clusters was based on anatomical features. For correlation analysis between sections, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated across all genes for each pairwise combination of sections from the entire dataset (Supplementary Data 1). Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the Pearson correlation coefficients using the clustermap function from Seaborn (v.0.12.0)55 with Euclidean distances and the Wart.D method. DEG were determined in two steps, first using the ranked genes function of Scanpy with two-side t-test and adjusting for multiple testing with Benjamini–Hochberg correction (Supplementary Data 1). Next, we calculated the mean z-score of each gene in the two groups of sections and computed the mean z-score difference between the clusters. Genes with a p value smaller than 0.05 and a mean z-score difference higher than 0.4 were considered differentially expressed. DEG were hierarchically clustered using Euclidean distances and the Wart.D method.

MALDI-MSI

Tissues were prepared for MALDI-MSI as previously described25. TA muscles were dissected from one female (Muscle 1) and two males (Muscle 2 and 3) Pax7nGFP50 mice, embedded in 7.5% HPMC (#H8384-25G, Merck) + 2.5% PVP (#PVP360-100G, Merck) on ice and snap frozen in dry ice chilled isopropanol for 2 min. Subsequently, tissues were transferred to liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane for 30 s and stored at −80 °C. MALDI-MSI was performed as previously described56. Frozen tissue blocks were cryosectioned longitudinally along the proximal-distal axis into 8 μm slices at −20 °C. The sections were thaw-mounted onto indium-tin-oxide (ITO)-coated glass slides (VisionTek Systems) and placed in a vacuum freeze-dryer for 15 min before MALDI-matrix application (7 mg/mL N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDC), Sigma-Aldrich) in methanol/acetonitrile/deionized water (70:25:5% vol/vol/vol). MALDI-TOF/TOF-MSI measurement was performed using a rapifleX MALDI-TOF/TOF system (Bruker Daltonics) and negative-ion-mode mass spectra were acquired at a pixel size 20 × 20 μm2 over a mass range of m/z 80–1000. MALDI-FTICR-MSI was performed on a prototype 15 T solariX 2xR-FTICR mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) in negative-ion mode, using 25 laser shots per pixel and a 75 × 75 μm2 pixel size, covering a mass range of m/z 550–1000.

Processing MALDI-MSI data

MSI data processing was performed as previously described13. We performed baseline correction and normalization to the total ion count. Peak picking was performed on the average spectrum and matrix peaks were excluded from the m/z feature list. Low-intensity pixels (<1e3.3) and pixels with fewer than 140 features were filtered out (Supplementary Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 2). Additionally, features with patterns related to freezing damage were excluded from the dataset (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The count table was normalized to the total intensity mean of all remaining pixels. Scaled and log10 transformed values were used for visualizations. Putative peak annotation was performed using two publicly available databases: the Human Metabolome Database (https://hmdb.ca/) and the LIPID MAPS Structure Database (https://www.lipidmaps.org/databases/lmsd/browse), in combination with work by Wang et al.57 (Supplementary Data 3). In addition, to validate our putative annotations we performed image validations by comparing MALDI-FTICR-MSI with MALDI-TOF-MSI spectra and image distributions (Supplementary Fig. 5). We selected the most likely candidate from the putative annotations based on multiple levels of annotation, as well as prior knowledge of the biological system (Supplementary Table 1).

Integration TOMOseq and MALDI-MSI dataset

To integrate the transcriptomic and metabolic datasets, we performed an in silico transformation of the MSI data into sections resembling TOMOseq. First, to create a pseudoTOMOseq of mass spectra data, the MALDI-MSI data was binned along the proximal-distal axis into fifty regions of the same length. To account for size differences along the tissues, the binned data was normalized to the number of pixels inside the bin. Scaled z-score transformed data was used for bar plots.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (HCR™ RNA-FISH) and immunofluorescence staining on thick sections

HCRTM RNA-FISH was performed as previously described22,51 using reagents and probes from Molecular Instruments on proximal, central and distal areas of TA muscles from two Pax7nGFP mice. Muscles were dissected and immediately submerged in ice-cold 4% PFA. After overnight fixation at 4 °C, tissues were cut into 350 μm slices using a McIlwain Tissue Chopper. Thick slices were washed twice for 5 min on ice in PBST (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS). Subsequently, tissues were dehydrated with an increasing gradient of methanol solutions (25%, 50%, 75% and 100%) in PBST for 5 min on ice. Tissues were stored in 100% methanol at −20 °C. For HCRTM RNA-FISH staining, tissues were rehydrated in a decreasing gradient of methanol solutions (75%, 50% and 25%) in PBST for 10 min on ice. The next day tissues were washed for 10 min at room temperature in PBST. All following incubation steps were performed on a thermomixer at 200 rpm. Tissues were treated with proteinase K solution (10 µg/mL) for 10 min at room temperature and washed twice for 5 min in PBST. Subsequently, sections were postfixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature and washed three times for 5 min in PBST. Sections were incubated twice in 150 μL of probe hybridization buffer, first for 5 min followed by 30 min incubation at 37 °C. Each section was incubated in 150 μL of 16 nM probe solution overnight at 37 °C. Negative controls were incubated in probe solution without primary probes (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The next day, tissues were washed four times for 15 min in probe wash buffer at 37 °C and twice with 5x SSCT (5X Saline Sodium Citrate containing 0.1% Tween-20) at room temperature. Pre-amplification buffer was added to tissues twice, first for 5 min and then for 30 min, at room temperature. Tissues were incubated in 150 μL of 3 μM hairpin solution overnight at room temperature. The next day, tissues were washed in 5x SSCT twice for 5 min, twice for 30 min and once for 5 min.

Following HCRTM RNA-FISH, thick sections were co-stained for DAPI and laminin subunit α-1 (1:200, #L9393, Sigma) to delimitate the myofiber perimeter as previously described58. After immunofluorescence, sections were dehydrated in a series of increasing ethanol solutions (25, 75, 50 and 100%) and cleared in ethyl cinnamate (ECi)59. Sections were mounted in ECi on glass slides with Grace Bio-Labs SecureSeal™ imaging spacers and imaged at 63x on a Sp8 confocal microscope (Leica).

Tissue collection histochemistry assays and immunofluorescence

Muscles were dissected from both male and female Pax7nGFP mice. Collected tissues were embedded in OCT, frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane for 30 s and stored at −80 °C. Frozen tissues were cryosectioned into 8 μm slices, collected on superfrost slides and stored at −20 °C.

α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (α-GPD) histochemistry

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for α-GPD histochemistry as previously described60 with some modifications. Tissue slides were air-dried for 10 min at room temperature. Followed by incubation in staining solution (9.3 mM rac-Glycerol 1-phosphate sodium salt hydrate (#61668, Sigma), 2.3 mM menadione (#M5625, Sigma) and 1.2 mM of nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (#N6495, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 0.05 M Tris buffer pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37 °C. Sections were then washed three times in deionized water for 1 min. Followed by 1 min washes in increasing (30%, 60%, 90%) and decreasing (90%, 60%, 30%) concentrations of acetone. Next, sections were rinsed three times in deionized water, dehydrated in increasing concentrations (50%, 70%, 100%) of ethanol, washed in xylene and mounted in Entellan™ new (#1.07962, Sigma). Slides were imaged at 20x on a Panoramic 250 slide scanner (3DHistech).

Succinic dehydrogenase (SDH) histochemistry

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for SDH histochemistry as previously described61. Tissue slides were air-dried for 10 min at room temperature. Followed by incubation in staining solution (28.4 mg/ml of sodium dibasic phosphate (#S5136, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 24 mg/ml of sodium monobasic phosphate anhydrous (#5011, Sigma), 27 mg/ml of sodium succinate dibasic hexa-hydrate (#S2378, Sigma) and 1 mg/ml of nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (#N6495, Thermo Fisher Scientific), pH 7.6) for 60 min at 37 °C. Sections were then washed three times in deionized water for 1 min, followed by 1 min washes in increasing (30%, 60%, 90%) and decreasing (90%, 60%, 30%) concentrations of acetone. Next, sections were rinsed three times in deionized water, dehydrated in increasing concentrations (50%, 70%, 100%) of ethanol, washed in xylene and mounted in Entellan™ new (#1.07962, Sigma). Slides were imaged at 20x on a Panoramic 250 slide scanner (3DHistech).

Cytochrome c oxidase (COX) histochemistry

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for COX histochemistry as previously described62. Tissue slides were air-dried for 10 min at room temperature. Followed by incubation in staining solution (28.4 mg/ml of sodium dibasic phosphate (#S5136, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 24 mg/ml of sodium monobasic phosphate anhydrous (#5011, Sigma), 100 μM cytochrome c (#C-2506, Sigma), 4 mM diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (#D-5637, Sigma) and 20 μg/ml of catalase (#C-9322, Sigma), pH 7.0) for 90 min at 37 °C. Sections were then washed three times in PBS for 1 min. Next, sections were rinsed three times in deionized water, dehydrated in increasing concentrations (50%, 70%, 100%) of ethanol, washed in xylene and mounted in Entellan™ new (#1.07962, Sigma). Slides were imaged at 20x on a Panoramic 250 slide scanner (3DHistech).

Blood vessel immunofluorescence

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for visualization of blood vessels. Fresh frozen slides were air-dried for 15–30 min at room temperature and rinsed in PBST buffer (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS). Subsequently, tissues were blocked for 1 h in PBS-MT (1% skim milk, 0.4% TritonX-100, 0.2% BSA and 0.1% goat serum in PBS). Tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C in PBS-MT buffer with primary antibodies against laminin subunit α-2 (1:250, #L0663, Sigma) to delineate fiber borders, and CD31 (1:50, #ab28364, Abcam). The next day, samples were washed in PBST buffer three times for 5 min. Subsequently, secondary antibodies AF488 Goat anti-Rat IgG (#A-11006, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and AF647 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (#A-21245, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature at concentrations of 1:500 in PBST. Then, sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBST. Sections were mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS and imaged at 10x on a LSM900 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Aldolase immunofluorescence

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for visualization of aldolase. Fresh frozen slides were air-dried for 15–30 min at room temperature. Tissues were fixed on ice-cold acetone for 10 min and washed in PBST for 1 min. Next, tissues were incubated in TrueBlack® Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher (Biotium, #23007) diluted 1:20 in 70% ethanol for 1 min. Tissues were washed three times for 1 min in PBST. Subsequently, tissues were blocked for 1.5 h in blocking buffer (5% skim milk, 10% goat serum and 5% horse serum in PBST). Tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 1% goat serum in PSBT with primary antibodies against laminin subunit α-2 (1:250, #L0663, Sigma) to delineate fiber borders, and aldolase (1:250, #ab252953, Abcam). The next day, samples were washed in PBST buffer three times for 5 min. Subsequently, secondary antibodies AF488 Goat anti-Rat IgG (#A-11006, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and AF647 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (#A-21245, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature at concentrations of 1:500 in PBST. Then, sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBST. Sections were mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS and imaged at 10x on a LSM900 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

IDH2 immunofluorescence

Consecutive fresh-frozen cryosections from muscles prepared for MALDI-MSI or histochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were used for visualization of IDH2. Fresh frozen slides were air-dried for 15–30 min at room temperature. Tissues were fixed on ice-cold acetone for 10 min and washed in PBST for 1 min. Subsequently, tissues were blocked for 1 h in blocking buffer (5% skim milk in PBST). Tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C in blocking buffer with primary antibodies against laminin subunit α-2 (1:250, #L0663, Sigma) to delineate fiber borders, and IDH2 (1:500, #ab131263, Abcam). The next day, samples were washed in PBST buffer three times for 5 min. Subsequently, secondary antibodies AF488 Goat anti-Rat IgG (#A-11006, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and AF647 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (#A-21245, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature at concentrations of 1:500 in PBST. Then, sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBST. Sections were mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS and imaged at 10x on a LSM900 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

MyHC immunofluorescence

Muscle fiber type composition was determined as previously described27 with some modifications on two or three sets of proximal, central, and distal sections of muscles from three Pax7nGFP mice. For MyHC isoform staining, fresh frozen slides were air-dried for 15–30 min at room temperature and rinsed in PBST buffer (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS). Subsequently, tissues were blocked for 1 h in 5% skim milk in PBST and treated with the Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M) immunodetection kit (BMK-2202, Vector laboratories) according to manufacturer instructions. Tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C in M.O.M diluent buffer with primary antibodies against laminin subunit α-1 (1:200, #L9393, Sigma) to delineate fiber borders, and MyHC isoforms: MYH4 diluted 1:50 (#14-6503-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or MYH7 diluted 1:10 (BA-D5, DSHB), MYH1 diluted 1:10 (6H1, DSHB) and MYH2 diluted 1:25 (SC-71, DSHB). The next day, samples were washed in PBST buffer three times for 5 min. Subsequently, secondary antibodies AF405 Goat anti-Mouse IgM (#ab175662, Abcam), AF488 Goat anti-Mouse IgG2b (#A-21141, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or AF488 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (#A-11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific), AF594 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (#A-11037, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or AF568 Goat anti-Mouse IgG2b (#A-21144, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and AF647 Goat anti-Mouse IgG1 (#A-21240, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature at concentrations of 1:500 in PBST. Then, sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBST. Sections were mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS and imaged at 10x on a LSM900 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Fiber type quantification

Quantitative analysis of myofiber type composition was performed as previously described27 for each group of proximal, central, and distal sections individually (Table 1), EDL (Table 2) and SOL (Table 3). We adjusted the thresholds to filter automated segmentation errors based on mean fluorescence intensity of the laminin channel inside the object (Mean < 99th percentile) and at the boundary (Mean_boundary > 1st percentile). The threshold for filtering based on cross-sectional area (CSA) was modified (TA: Muscle 1, 7th percentile < Area < 99.9th percentile; Muscle 2, 2.5th percentile < Area < 99.9th percentile; Muscle 3, 2nd percentile < Area < 99.9th percentile. EDL: 1st percentile < Area < 99.9th percentile. SOL: 10th percentile < Area < 99.9th percentile) to include differences in CSA of myofiber types across different muscles63. Fiber type fractions were calculated for each set of sections and normalized to the central section. For statistical analysis, the normalized fraction of each myofiber was calculated across technical and biological replicates for the three different regions (proximal, central, and distal). Differences in fiber type contribution were determined using a two-sided t-test. In general, central areas of the muscles displayed more significant differences in fiber type proportions compared to distal areas than to proximal areas. Most likely, central and distal sections are recovered in all experiments, and this is not always the case for proximal sections. Therefore, what we initially considered to be anatomically proximal sections could be better classified as central.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Stem Cell Medicine (reNEW) grant number NFF21CC0073729. The authors thank the LUMC animal facility, LUMC Light and Electron Microscopy, and the LUMC Center for Proteomics and Metabolomics facilities, especially Elena Sánchez López for providing the raw MSI data. We thank Single Cell Discoveries for performing the library preparations and sequencing. Pax7nGFP mice were kindly provided by S. Tajbakhsh (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). DCM–Polr2b:m2rtTA mice were kindly provided by J. Gribnau (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands).

Author contributions

N.G. and F.S. conceived and designed the project. C.M.M. carried out the experiments with assistance from P.P., I.D.P., M.R. and M.v.K. with guidance from F.S. and A.A. throughout. C.M.M. analyzed and interpreted the results with input from F.S., A.A. and N.G. C.M.M. prepared the material for the metabolomics analysis, the experiment was performed by the LUMC Center for Proteomics and Metabolomics under the guidance of B.H. C.M.M. wrote the paper and assembled the data with assistance from F.S., A.A. and N.G. The rest of the authors provided comments on the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Zheng-Jiang Zhu and Joao Valente. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All RNA sequencing datasets produced in this study are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE253441. The MSI data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE64 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD048809. Source Data for Figs. 1–5 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 4, 8 and 9 are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Code availability

All code is available at GitHub (https://github.com/anna-alemany/mouseGastruloids_scRNAseq_tomoseq and https://github.com/claramartinezmir/TOMOseq_skeletalMuscle) or Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.13789539 and 10.5281/zenodo.13795695).

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: during the writing of the manuscript, B.H. was employed by Bruker Daltonics GmbH.

Ethical approval

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fanny Sage, Email: f.g.sage@lumc.nl.

Niels Geijsen, Email: n.geijsen@lumc.nl.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06949-1.

References

- 1.Cramer, A. A. W. et al. Nuclear numbers in syncytial muscle fibers promote size but limit the development of larger myonuclear domains. Nat. Commun.11, 6287 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansson, K.-A. et al. Myonuclear content regulates cell size with similar scaling properties in mice and humans. Nat. Commun.11, 6288 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scime, A., Caron, A. Z. & Grenier, G. Advances in myogenic cell transplantation and skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Front. Biosci.14, 3012–3023 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talbot, J. & Maves, L. Skeletal muscle fiber type: using insights from muscle developmental biology to dissect targets for susceptibility and resistance to muscle disease. WIREs Dev. Biol.5, 518–534 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith, J. A. B., Murach, K. A., Dyar, K. A. & Zierath, J. R. Exercise metabolism and adaptation in skeletal muscle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.24, 607–632 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, M. et al. Single-nucleus transcriptomics reveals functional compartmentalization in syncytial skeletal muscle cells. Nat. Commun.11, 6375 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dos Santos, M. et al. Single-nucleus RNA-seq and FISH identify coordinated transcriptional activity in mammalian myofibers. Nat. Commun.11, 5102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrany, M. J. et al. Single-nucleus RNA-seq identifies transcriptional heterogeneity in multinucleated skeletal myofibers. Nat. Commun.11, 6374 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Brink, S. C. et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals dissociation-induced gene expression in tissue subpopulations. Nat. Methods14, 935–936 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Ercole, C. et al. Spatially resolved transcriptomics reveals innervation-responsive functional clusters in skeletal muscle. Cell Rep.41, 111861 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKellar, D. W. et al. Spatial mapping of the total transcriptome by in situ polyadenylation. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 513–520 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo, L. et al. Spatial metabolomics reveals skeletal myofiber subtypes. Sci. Adv.9, eadd0455 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olie, C. S. et al. The metabolic landscape in chronic rotator cuff tear reveals tissue‐region‐specific signatures. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle13, 532–543 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junker, J. P. et al. Genome-wide RNA tomography in the zebrafish embryo. Cell159, 662–675 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Micheli, A. J., Spector, J. A., Elemento, O. & Cosgrove, B. D. A reference single-cell transcriptomic atlas of human skeletal muscle tissue reveals bifurcated muscle stem cell populations. Skelet. Muscle10, 19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKellar, D. W. et al. Large-scale integration of single-cell transcriptomic data captures transitional progenitor states in mouse skeletal muscle regeneration. Commun. Biol.4, 1280 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Micheli, A. J. et al. Single-cell analysis of the muscle stem cell hierarchy identifies heterotypic communication signals involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Rep.30, 3583–3595.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey, T., Flamenco, S. & Fan, C.-M. A Tppp3+Pdgfra+ tendon stem cell population contributes to regeneration and reveals a shared role for PDGF signalling in regeneration and fibrosis. Nat. Cell Biol.21, 1490–1503 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas, P. D. et al. PANTHER: making genome‐scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Sci.31, 8–22 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aleksander, S. A. et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics224, iyad031 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet.25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi, H. M. T. et al. Third-generation in situ hybridization chain reaction: multiplexed, quantitative, sensitive, versatile, robust. Development145, dev165753 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dos Santos, M. et al. A fast Myosin super enhancer dictates muscle fiber phenotype through competitive interactions with Myosin genes. Nat. Commun.13, 1039 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redmond, A. K., Davies, T. M., Schofield, M. R. & Sheard, P. W. New tools for the investigation of muscle fiber-type spatial distributions across histological sections. Skelet. Muscle13, 7 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dannhorn, A. et al. Universal sample preparation unlocking multimodal molecular tissue imaging. Anal. Chem.92, 11080–11088 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unsihuay, D. et al. Multimodal high-resolution nano-DESI MSI and immunofluorescence imaging reveal molecular signatures of skeletal muscle fiber types. Chem. Sci.14, 4070–4082 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbassi-Daloii, T. et al. Quantitative analysis of myofiber type composition in human and mouse skeletal muscles. STAR Protoc.4, 102075 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyagi, S., Beqollari, D., Lee, C. S., Walker, L. A. & Bannister, R. A. Semi-automated analysis of mouse skeletal muscle morphology and fiber-type composition. J. Vis. Exp.126, e56024 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giacomello, E. et al. Age dependent modification of the metabolic profile of the tibialis anterior muscle fibers in C57BL/6J mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 3923 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murgia, M. et al. Protein profile of fiber types in human skeletal muscle: a single-fiber proteomics study. Skelet. Muscle11, 24 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bloemberg, D. & Quadrilatero, J. Rapid determination of myosin heavy chain expression in rat, mouse, and human skeletal muscle using multicolor immunofluorescence analysis. PLoS ONE7, e35273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, G., Mac Gabhann, F. & Popel, A. S. Effects of fiber type and size on the heterogeneity of oxygen distribution in exercising skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE7, e44375 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shephard, F., Greville-Heygate, O., Marsh, O., Anderson, S. & Chakrabarti, L. A mitochondrial location for haemoglobins—dynamic distribution in ageing and Parkinson’s disease. Mitochondrion14, 64–72 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebanks, B. et al. Mitochondrial haemoglobin is upregulated with hypoxia in skeletal muscle and has a conserved interaction with ATP synthase and inhibitory factor 1. Cells12, 912 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korfage, J. A. M., Kwee, K. E., Everts, V. & Langenbach, G. E. J. Myosin heavy chain expression can vary over the length of jaw and leg muscles. Cells Tissues Organs201, 130–137 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]