Abstract

The genetic analysis of potato is hampered by the complexity of tetrasomic inheritance. An ongoing effort aims to transform the clonally propagated tetraploid potato into a seed-propagated diploid crop, which would make genetic analyses much easier owing to disomic inheritance. Here, we construct and report the large-scale genetic and heterotic characteristics of a diploid F2 potato population derived from the cross of two highly homozygous inbred lines. We investigate 20,382 traits generated from multi-omics dataset and identify 25,770 quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Coupled with gene expression data, we construct a systems-genetics network for gene discovery in potatoes. Importantly, we explore the genetic basis of heterosis in this population, especially for yield and male fertility heterosis. We find that positive heterotic effects of yield-related QTLs and negative heterotic effects of metabolite QTLs (mQTLs) contribute to yield heterosis. Additionally, we identify a PME gene with a dominance heterotic effect that plays an important role in male fertility heterosis. This study provides genetic resources for the potato community and will facilitate the application of heterosis in diploid potato breeding.

Subject terms: Plant breeding, Plant genetics, Agricultural genetics, Genetic hybridization

An ongoing effort aims to transform the clonally propagated tetraploid potato to a seed-propagated diploid crop, but our understanding of it disomic inheritance is limited. Here, the authors report genetic basis of heterosis in the elite hybrid potato and identify a male fertility-related PME gene with dominance heterotic effect.

Introduction

Understanding the genetic basis of variation for quantitative traits has been a long-standing challenge in biology. Forward genetics is the classical approach in genetics research. In contrast to reverse genetics, forward genetics progresses from phenotype to genotype, aiming to identify elements of genetic variation that underlie the corresponding phenotypes1,2. Association analysis of natural populations and linkage mapping of biparental segregating populations (F2, recombinant inbred lines [RILs], etc.) constitute two approaches to map QTLs3. The efficacy of forward genetics is affected by the density of genetic markers, the accuracy of scored phenotypes and the size of the mapping population4. Benefiting from the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, genotyping by sequencing facilitates the identification of genetic variation. More and more phenotypes can be accurately measured using the multi-omics approach, such as transcriptomics, metabolomics and phenomics5. This also underlies and enables genetical genomics or systems genetics approaches that combine genetics with gene expression analysis to understand complex traits6,7. The concept of systems genetics was proposed in the early 21st century7–9, and much progress has been made in humans10–12 and plants13–15. The application of systems genetics in crops promises to facilitate both gene discovery and molecular breeding.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is the most important tuber crop and staple food for 1.3 billion people worldwide16. However, the complexity of tetrasomic inheritance has limited genetic studies in potato. It is challenging to resolve QTLs to the single-gene level using autotetraploid populations (2n = 4x = 48). Genetic analysis at the diploid level will help to simplify analyses and identify genes associated with agronomically important traits. By overcoming self‐incompatibility17–20 and inbreeding depression21–23, tremendous efforts have already been made to reinvent potato as a seed-propagated diploid crop; yet, compared with other major crops, diploid potato breeding is still in its infancy5,24–26. Several studies have explored the potential to map QTLs using the diploid populations27–31. However, almost all of the diploid mapping populations have been derived from two heterozygous parents that contain four segregating alleles, and lack of large-scale genetic analysis limits their application in potato breeding. In a previous study, we developed a genome-design approach and created a diploid hybrid potato based on two inbred parental lines23. The two parents, coming from two different diploid accessions: S. tuberosum group Stenotomum and S. tuberosum group Phureja, have significant diversity in tuber traits, gene expression and metabolite content, etc.23,32 The segregating F2 population generated from the two lines is an ideal resource for large-scale genetic analyses of potato, especially for the genetic dissection of heterosis.

Heterosis refers to the superior performance of hybrids over their parents33–35, which has been extensively applied for agronomic purposes in animals and plants. Understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying heterosis is beneficial for future crop hybrid breeding. Dominance, overdominance and epistasis are three classical models causally explaining the phenomenon of heterosis36–38. Recent reports in rice and maize found that dominance and overdominance effects have explanatory power in the different F2 populations39,40. However, mechanisms underlying heterosis in clonally propagated crops are largely unknown. The diploid hybrid potato we created exhibits significant heterosis at different developmental stages23,32, and it constitutes suitable material for the study of mechanisms underpinning heterosis. Furthermore, genetic dissections of the key loci contributing to heterosis are achievable in the F2 population, enabling us to evaluate the potential heterotic effects of each locus.

In this study, we conduct large-scale genetic and heterotic analyses in a diploid inbred line-based F2 population. Using a multi-omics dataset, we construct a large database of genetic resources. Importantly, we reveal the genetic basis of heterosis in this elite hybrid potato cross and identify a male fertility-related PME gene with dominance heterotic effect. Our findings contribute to the molecular breeding of diploid potato and provide insights into the understanding of heterosis in clonally propagated crops.

Results

The sequencing map of an inbred line-based F2 population

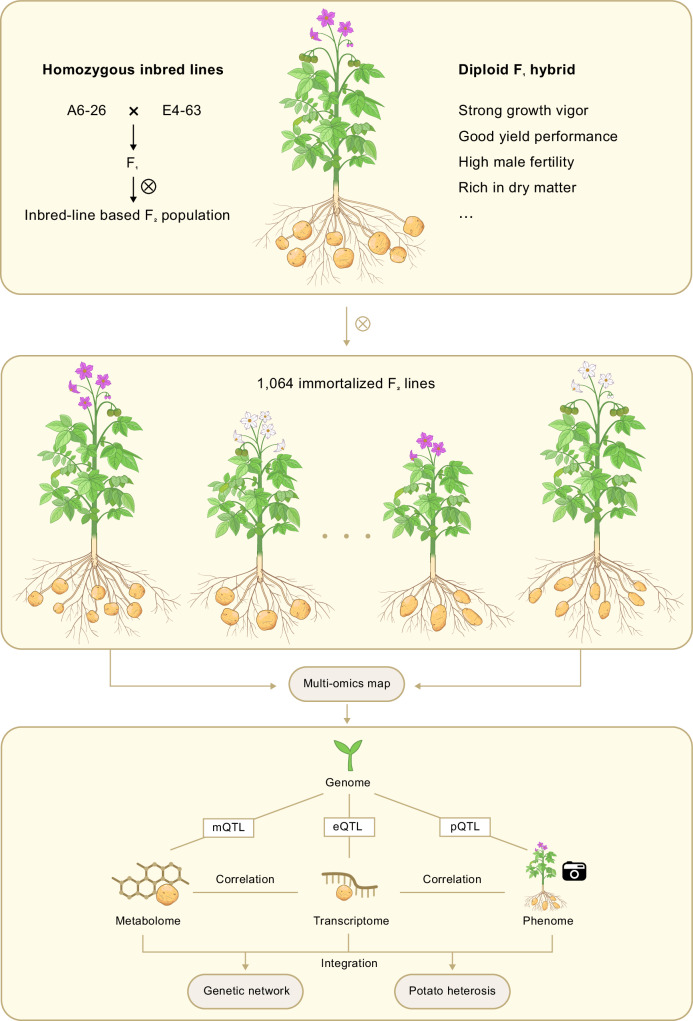

A summary of our sequencing map and research pipeline is outlined in Fig. 1. We constructed an immortalized F2 population, including 1064 individuals and conserved by tissue culture, derived from two homozygous diploid inbred lines23: A6-26 and E4-63. We re-sequenced all F2 plants with an average coverage of 3× and constructed a high-density genotype and genetic map based on 4,794,364 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for QTL mapping (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). We identified two genomic regions with severe segregation distortion (SD) where the segregation ratios in the F2 population did not agree with 1:2:1 proportion (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These two SD regions colocalize with two self-compatibility-related genes: the S-RNase mutant Ss11 on chromosome 1 (chr01) (derived from the female parent A6-26)17 and the S-locus inhibitor (Sli) on chr12 (derived from the male parent E4-63)19,20. Only pollen grains harboring either one or both genes complete the double fertilization, therefore resulting in SD in the F2 population.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of genetic and heterosis analyses in an inbred line-based F2 population.

The F1 hybrid potato with strong heterosis was selfed to generate the F2 segregating population. The analyses of genetic network and potato heterosis were conducted using multi-omics data including genomic, phenomic (macro-phenome), transcriptomic and metabolomic data.

To boost the progress of gene discovery in potato, we developed a high-throughput phenome detection and analysis system that integrates multi-omics technology and further divided the potato phenome into macro-phenome and micro-phenome. The macro-phenome includes traits investigated by manual and high-throughput optical imaging (RGB camera, hyperspectral imaging and structured light imaging) (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Methods 1 and 2). We thus generated 537 macro-traits including pollen viability, yield-related traits, tuber structure-related traits, morphology-related traits, etc. (Supplementary Data 1). The micro-phenome consists of the transcriptome and the metabolome of tuber. After filtering out low-quality data, we identified 19,166 expressed genes and 679 metabolites for genetic and heterotic analyses.

QTL mapping of the multi-omics traits

We mapped several qualitative traits to known loci using bulked-segregant analysis (BSA). For example, genes controlling tuber flesh color and tuber shape mapped to the ends of chr03 and chr10, corresponding to the Y locus41 and the Ro gene29,42, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Purple Tuber Bud is located on chr02, corresponding to the same region as purple flower32 and possibly regulated by DFR (Dihydroflavonol-4-reductase, D locus)43 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The gene associated with yellow leaf was mapped to chr12 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). The underlying gene yl1 came from parent A6-26 and was also found in progeny of PG6359 (the parental line of A6-26)21,23.

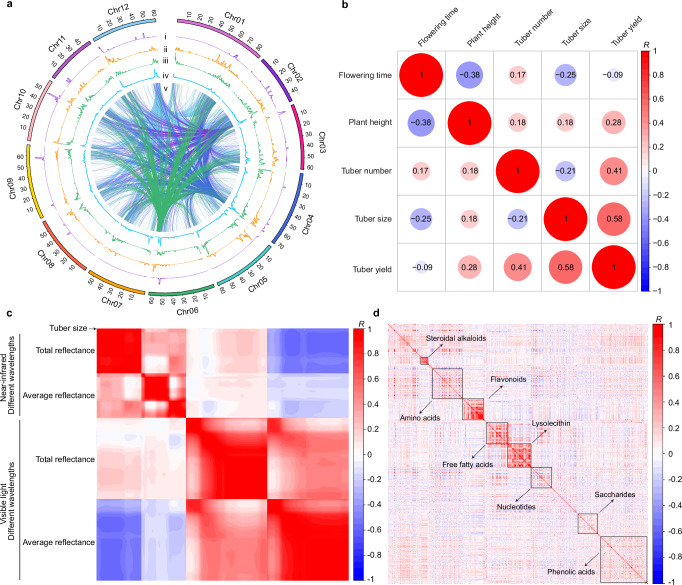

We applied the composite interval-mapping method to map quantitative traits, identifying 135 macro-phenome QTLs (pQTLs) (Fig. 2a, Table 1, Supplementary Data 2). We collected data on pollen viability (male fertility-related) and flowering time (yield-related) during the 2021 trial and obtained data for four other yield-related traits (plant height, tuber yield, tuber number and tuber size) during the trials in 2021 and 2023, with three replicates each year (see Methods). The correlations between five yield traits of the 1064 individuals revealed that tuber number, tuber size and plant height all positively contribute to tuber yield in two years, while tuber size and tuber number are negatively correlated, consistent with abundant observations to that effect (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4). Among the 135 pQTLs, 68 are related to shoot RGB image-based above-ground traits involving shoot greenness-related traits, shoot morphology-related traits, etc (Supplementary Methods 1 and 2). Of those, C01G_Bin340 controls seven morphology-related traits (Supplementary Data 2) and harbors an OVATE transcription factor (St_E4-63_C01G002870). The OVATE family proteins have been reported to regulate plant architecture44 and fruit morphology45. Since the hyperspectral imaging is primarily used for prediction and has been successfully applied to predict water content, yield and metabolites in wheat46,47, they are excluded from genetic mapping. Correlation coefficients of tuber size and tuber reflectance reveal that tuber size is positively correlated with total reflectance of near-infrared (R > 0.7, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 for all wavelengths), but negatively correlated with average reflectance of visible light (R < −0.4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 for all wavelengths) (Fig. 2c). To further connect the tuber spectroscopic data with tuber-related traits, we modeled them using stepwise linear regression analysis. We found that tuber reflectance could be a good indicator of tuber dry matter and tuber yield, whose direct measurement is labor-intensive and time-consuming. Through a 10-fold cross-validation, we further identified the wavelengths that are most effective for predicting dry matter and yield (Supplementary Data 3 and 4). The best prediction accuracy of correlation coefficients (R2) is 0.81 for tuber dry matter and 0.62 for tuber yield (Supplementary Fig. 5), which indicates these tuber reflectance traits can be used for non-destructive selection of potato lines with higher dry matter or yield. The same strategy was used to predict the content of tuber metabolites. We identified 162 metabolites that can be well predicted (R2 > 0.5) using hyperspectral reflectance (Supplementary Data 3 and 4). Tuber structure, including shape-related traits (length, width and height) and size-related traits (surface area and volume), was detected by structured light imaging (Supplementary Methods 1 and 2). The QTLs of these traits are mainly enriched on chr09 (all five traits) and chr10 (tuber length, tuber width and tuber height), consistent with the results generated by manual investigation (Supplementary Data 2). These results indicate that the high-throughput optical imaging system can be applied for efficient phenotype detection of potato.

Fig. 2. Overview of QTLs at the whole genome and correlation of different traits.

a QTL distribution analyzed by sliding windows with 1-Mb window and 100-kb step sizes. The y-axis of i–iv indicates QTL number. i, pQTLs; ii, mQTLs; iii, local eQTLs; iv, distant eQTLs; v, the regulatory network of distant eQTL hotspots. b Correlation of tuber yield-related traits in 2021. c Correlation of tuber size and tuber reflectance. The first row concerns tuber size, indicated by the arrow. d Correlation of metabolites. Different kinds of metabolites can be separated by their levels of correlation (R). The x and y axes indicate different kinds of metabolites. In (b–d), red indicates positive and blue indicates negative correlations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Table 1.

Numbers of traits and QTLs

| Trait | Number | Traits with QTLs | QTL number | Local eQTLs | Distant eQTLs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome | 19,166 | 14,835 | 24,371 | 7273 | 17,098 |

| Metabolome | 679 | 538 | 1264 | ||

| Phenome | 537 | 47* | 135 | ||

| Total | 20,382 | 15,420 | 25,770 |

*Note: A total of 488 hyperspectral imaging traits are excluded from genetic mapping.

To explore genetic variants involved in gene expression, we conducted expression QTL (eQTL) mapping using normalized FPKM values. We identified 24,371 eQTLs associated with 14,835 genes, accounting for 77.4% of tuber-expressed genes (Fig. 2a, Table 1, Supplementary Data 2). About 43.0% of the genes (6735) are regulated by more than one eQTL. To better understand the regulatory mechanism of eQTLs, we further divided them into 7273 local eQTLs and 17,098 distant eQTLs, based on the distance between eQTLs and their corresponding genes. In our dataset, we identified nine distant eQTL hotspots (permutation test, p-value < 0.01, distant eQTL number > 223). These hotspots comprise 3009 correlations and can regulate the expression of 2876 genes (Fig. 2a).

For the tuber metabolome, we found that different kinds of metabolites can be separated by their strength of correlation (Fig. 2d). The similar accumulation patterns of highly correlated abundance of some metabolites suggests that they might be controlled by the same regulator or affected by a change in the abundance of upstream metabolites from a single pathway. We detected 1264 mQTLs for 538 metabolites (Fig. 2a, Table 1, Supplementary Data 2). Among these metabolites, 69.1% have more than one mQTL. Moreover, we found that some metabolites with high correlation were mapped to the same genetic regions. For example, several steroid alkaloids (also called solanine in potato) are all regulated by C01G_Bin334–C01G_Bin338. Some flavonols, mainly glycosylated substances, colocalize in C01G_Bin210–C01G_Bin222 (Supplementary Data 2). This finding can help identify potential master regulators of these metabolites.

The systems genetics of the F2 population

Integrating the multi-omics data, we applied a systems-genetics approach to construct the genetic network of this population (Supplementary Fig. 6a). First, we conducted a weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) to identify genes with similar expression patterns, uncovering 21 modules (referred to as M1–M21) based on 19,166 tuber-expressed genes (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Correlation analysis between gene expression and tuber-related traits (yield and metabolites) identified 66,512 correlations (q-value < 0.001) with a median correlation coefficient of 0.35, associated with 12,824 genes, 376 metabolites and three yield-related traits (Supplementary Data 5).

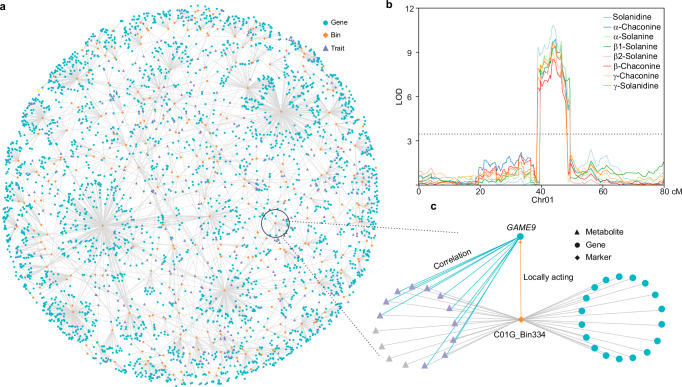

Next, according to the results of QTL mapping, we analyzed the bins regulating both gene expression and tuber-related traits (metabolite content and yield-related traits), defined as so-called triple relationships. A total of 3499 triple relationships (gene–bin–trait) emerged, including 2728 genes, 361 metabolites and three yield-related traits (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 6). Solanine content of potato tubers is a domesticated trait and plays an important role in tuber quality. As mentioned above, solanines have a common mapping region at C01G_Bin334 (Fig. 3b). Since the identified solanines are highly correlated, we further conducted QTL mapping using the dimensionality reduction method48, and the same locus was found on chr01 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The WGCNA data show that Module 20 (M20) is highly correlated with various types of solanines (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis revealed that genes in M20 are significantly enriched in the “steroid biosynthesis” term (Supplementary Fig. 7b), such as St_ E4-63_C04G002433 (cycloartenol synthase), St_ E4-63_C01G002910 (sterol 4 α-methyl oxidase), and others. Based on the triple relationships, 19 genes are also regulated by the solanine-common bin C01G_Bin334, of which three are regulated in a locally acting manner: St_E4-63_C01G002818, St_E4-63_C01G002829 and St_E4-63_C01G002853, with only St_E4-63_C01G002818 belonging to M20. The correlation data of gene expression and metabolites revealed that only St_E4-63_C01G002818 shows significant correlation (q-value < 0.001) with all colocalized solanines (Fig. 3c). According to its gene annotation, St_E4-63_C01G002818 encodes an ethylene-responsive transcription factor known as GAME9, a master regulator of solanine49,50. We then checked the expression level of GAME9 and solanine content of the parents’ tubers. We found that GAME9 is more highly expressed in A6-26 than in E4-63 (p-value < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Additionally, by comparing the promoter sequence (2000 bp upstream of the ATG) of GAME9 in the two parental lines, we identified an activation sequence-1 (as-1) element that can activate gene expression in plants51 and was disrupted by an 11-bp insertion in E4-63, which may lead to lower expression of GAME9 (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Consistent with this, the tubers of A6-26 contain markedly more solanines than those of E4-63 (p-value < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 7e), which further suggests that GAME9 is responsible for solanine accumulation in this population. Interestingly, GAME9 is located at a domestication-selection sweep in potato52, which is consistent with the domestication of solanines. We applied the same strategy for colocalized flavonols and identified two candidate genes (Supplementary Fig. 7f–h). These results demonstrate the high efficacy of this genetic network and bode well for its use in gene discovery.

Fig. 3. The systems-genetics network.

a The triple relationships (gene–bin–trait) associated with 2728 genes, 245 bins, 361 metabolites and three yield-related traits. b QTLs of different kinds of solanines on chr01. The dotted line shows the LOD cutoff value (3.5). c The regulatory network of GAME9. C01G_Bin334 regulates the expression of GAME9 in a locally acting manner; GAME9 significantly correlates with solanines (purple triangles) in the WGCNA (q-value < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Single-locus heterotic effects in the diploid potato hybrid

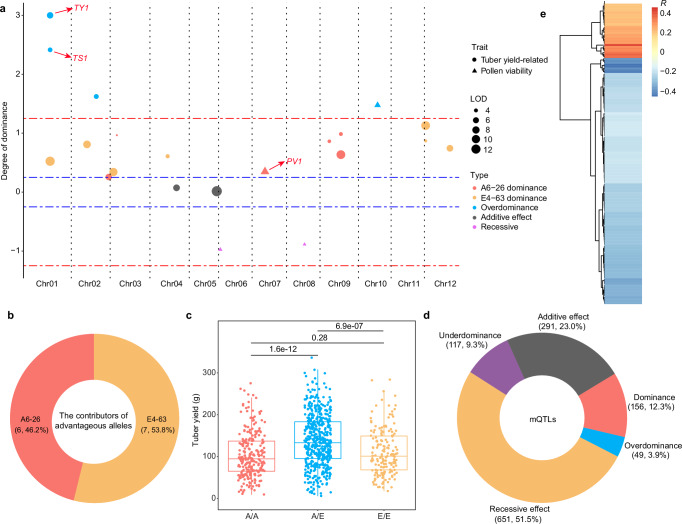

Heterosis, characterized by the better performance of hybrids compared to their parents, has been extensively applied in crop breeding. To better understand the mechanisms underlying heterosis in potato, we estimated the genetic effects of the identified QTLs. By comparing the heterozygous genotype with both homozygous genotypes, we used the degree of dominance (d/a) of each QTL to estimate single-locus heterotic effects.

Male fertility and tuber yield are two key traits for hybrid potato breeding. Through the analysis, we identified four pollen viability and 24 yield-related QTLs which were identified in both years. For all 28 QTLs, 21 exhibited consistent heterotic patterns in two years (including 1-year traits). We found that (partial) dominance constitutes the main heterotic effect, followed by overdominance (Fig. 4a), similar to reports in rice39 and maize40. The dominance model of heterosis implies that the trait value of the heterozygous QTL is the same as that of the advantageous homozygous genotype. Thus, to further elucidate the contributors of advantageous alleles in F1 hybrids, we assessed the trait values of all dominant QTLs. The contributions of better yield and pollen viability from the two parents are almost equal (Fig. 4b). For instance, both A6-26 and E4-63 contribute to tuber yield of hybrids (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Five QTLs (Tuber Yield, TY; Tuber Size, TS) show dominance effects (TY2, TY4, TY5, TS3 and TS4). In these dominant QTLs, TY4 and TS4 were contributed by E4-63 (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c), and TY2, TY5 and TS3 were contributed by A6-26 (Supplementary Fig. 8d–f). The complementation of these dominant QTLs in F1 hybrids results in partial yield heterosis.

Fig. 4. Single-locus effects of heterosis in the diploid hybrid.

a The heterotic effects of yield and pollen viability QTLs. The y axis indicates d/a values; d/a values > 3 are displayed as 3. The red dotted line indicates ±1.25 and the dotted blue lines indicate ±0.25. Data from 2021 were used. b The contributor (parental) source of advantageous alleles in hybrid potato. c The yield of different genotypes of TY1 in 2021. A/A, the A6-26 homozygous genotype (A6-26/A6-26); A/E, the heterozygous genotype (A6-26/E4-63); E/E, the E4-63 homozygous genotype (E4-63/E4-63); n = 253, 498 and 163 for A/A, A/E and E/E, respectively. The upper and lower edges of the boxes denote 75% and 25% quartiles, and the central line indicates the median. Whiskers extend to the lower hinge –1.5× interquartile range and upper hinge +1.5× interquartile range of the data. P values are obtained by Student’s t tests (two-tailed). d The proportion of different genetic effects of mQTLs. The numbers in parentheses refer to QTL numbers and percentages. e Correlations (R) between dry matter and metabolites with p-values < 0.01. P values are computed with Pearson correlation tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Of the overdominant or pseudo-overdominant QTLs, TY1 (C01G_Bin337) showed the largest heterotic effect in both 2021 and 2023 (d/a = 14.35 [2021] and 19.01 [2023]), explaining 6.55% and 4.21% of the phenotypic variance for 2021 and 2023, respectively (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). Trait value analysis of TY1 showed that the yield of TY1/ty1 was significantly higher than that of TY1/TY1 (E/E, p-value = 6.9 × 10−7) and ty1/ty1 (A/A, p-value = 1.6 × 10−12), whereas there was no significant difference between the parents (p-value = 0.28) (Fig. 4c). The same heterotic pattern was found for TY1 in 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Interestingly, C01G_Bin337 is the common QTL of three yield-related traits (tuber yield, tuber size and plant height) (Supplementary Data 2). Consistent with the tuber yield, C01G_Bin337 (TS1 for tuber size) also showed overdominant/pseudo-overdominant effect for tuber size in both two years (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). Also, there were no negative heterotic effects (recessive or underdominance) in yield heterosis. All yield QTLs added positive or additive contributions to yield performance in heterozygous genotypes, leading to yield heterosis in F1 hybrids. For a deeper understanding of yield heterosis, additional efforts are needed to resolve the identified QTLs to the single-gene level.

The expression patterns of genes also contribute to crop heterosis. We found that additive effects are the major genetic effects of gene expression. About 37.7% of eQTLs show additive effects (Supplementary Fig. 10a), indicating that the gene expression level controlled by these eQTLs in heterozygous genotypes is about half the level of the two (combined) homozygous genotypes. We then focused on (partial) dominance/overdominance and further identified 1878 genes with positive eQTLs (all eQTLs associated with the expression of a gene show dominance or overdominance effects) (Supplementary Data 7). The KEGG analysis found that genes with positive eQTLs are significantly enriched in some primary metabolic pathway, such as “citrate cycle” and “biosynthesis of amino acids” (Supplementary Fig. 10b), which might be associated with the energy metabolism process in tubers.

We found different patterns when estimating the heterotic effects of metabolites. In contrast to yield-related traits, the recessive model (51.5%) represents the principal heterotic effects for metabolites (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 10c). Dominance and overdominance account for only 12.3% and 3.9%, respectively (Fig. 4d). Although the primary metabolites are associated with more positive mQTLs than those of secondary metabolites, the overall patterns of primary and secondary metabolites are consistent with the pattern for the entirety of metabolites (Supplementary Fig. 10d, e). This implies that most mQTLs tend to cause the heterozygous genotypes to contain fewer small-molecule metabolites than the mid-parent value. Our previous study demonstrated that most metabolites in F1 tubers show negative mid‐parent heterosis32, consistent with the findings in the F2 population. As conjectured for F1 hybrids, this indicates that the energy of heterozygous-genotype tubers is preferentially used to synthesize dry matter such as starch and proteins, which cannot be detected by metabolome technology used in this study. Correlation analysis showed that 84.0% of metabolites are negatively correlated with dry matter (p-value < 0.01) (Fig. 4e). We then evaluated the d/a of the mQTLs using dry matter as the input trait. For the recessive/underdominant mQTLs, only 19.0% were also regarded as recessive or underdominant effects for dry matter, while the dominance/overdominance increased to 73.1% (Supplementary Fig. 10f), the opposite pattern between dry matter and metabolites (more dry matter and fewer metabolites content in F1 tuber). These results further support our findings in metabolites heterosis.

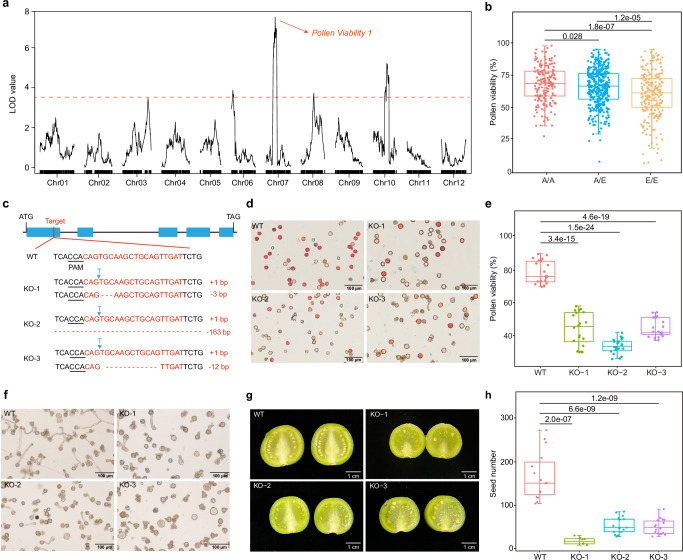

A pectin methylesterase contributes to male fertility heterosis

Among the four pollen viability QTLs, the locus on chr07 with the highest LOD value (PV1) exhibited a dominance heterotic effect (Fig. 4a and Fig. 5a). The trait value analysis revealed that the beneficial allele comes from the A6-26 parent (Fig. 5b). Although the pollen viability of A6-26 was inferior to that of E4-6332, A6-26 produced more seeds than E4-63. To investigate whether PV1 is associated with this phenomenon, we integrated genomic and transcriptomic data to clone this major-effect gene governing pollen viability in this population.

Fig. 5. The PME gene contributes to male fertility heterosis in potato.

a The QTL mapping of pollen viability. The cutoff LOD value was set to 3.5. b The pollen viability of different genotypes of PV1. A/A, the A6-26 homozygous genotype (A6-26/A6-26); A/E, the heterozygous genotype (A6-26/E4-63); E/E, the E4-63 homozygous genotype (E4-63/E4-63); n = 185, 399 and 233 for A/A, A/E and E/E, respectively. The upper and lower edges of the boxes denote 75% and 25% quartiles, and the central line indicates the median. Whiskers extend to the lower hinge –1.5× interquartile range and upper hinge +1.5× interquartile range of the data. P values are obtained by Student’s t tests (two-tailed). c The sequence of knockout target and main mutant type of PMEKO plants. d The pollen grain stain of WT and PMEKO plants. Red means good viability. e Statistics of pollen viability of WT and PMEKO plants. n = 20 for WT, KO-1, KO-2 and KO-3; The upper and lower edges of the boxes denote 75% and 25% quartiles, and the central line indicates the median. Whiskers extend to the lower hinge –1.5× interquartile range and upper hinge +1.5× interquartile range of the data. P values are obtained by Student’s t tests (two-tailed). f Pollen germination of WT and PMEKO plants. g The fruit and seed pictures of WT and PMEKO plants. h Statistics of seed number of WT and PMEKO plants. n = 15, 8, 17 and 18 for WT, KO-1, KO-2 and KO-3, respectively. The upper and lower edges of the boxes denote 75% and 25% quartiles, and the central line indicates the median. Whiskers extend to the lower hinge –1.5× interquartile range and upper hinge +1.5× interquartile range of the data. P values are obtained by Student’s t tests (two-tailed). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Based on the reference genome of E4-63, 21 genes were identified within the PV1 interval spanning a 310-kb interval. We conducted anther transcriptome sequencing of E4-63 including four important developmental stages, encompassing the initial to complete maturity stages (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Among the 21 genes, 11 were expressed (FPKM > 1.5) in at least one stage (Supplementary Fig. 11b). To pinpoint the candidate gene, we checked their expression in other tissues23 and found only St_E4-63_07G001402 and St_E4-63_07G001408 showed lower expression in other tissues but higher expression in anther (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Notably, these two genes displayed a rising-then-falling expression pattern in anther, peaking at stage 3 (with FPKMs of 6.32 and 23.72 for St_E4-63_07G001402 and St_E4-63_07G001408, respectively). Based on gene annotation, St_E4-63_07G001402 encodes a zinc/iron permease, while St_E4-63_07G001408 encodes a pectin methylesterase (PME) with a signal peptide and a predicted PME domain. To our knowledge, zinc/iron permease is not associated with pollen development, but PME is a widely distributed cell wall-related enzyme in plants, implicated in pollen wall synthesis53.

To verify the function of the PME gene in potato, we constructed a CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting the first exon to knock out the PME gene in the diploid potato clone 01-58. Although carrying different mutant types, the two alleles of PME gene in three PME-knockout (PMEKO) plants were mutational in the transgenic T0 plants (Fig. 5c). Pollen viability in PMEKO plants (34–45%) was significantly reduced compared to that in wild-type (WT) plants (~80%) (Fig. 5d, e). Scanning electron microscopy revealed that some pollen grains of the PMEKO plants exhibited aberrant morphology (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). As pectin plays a vital role in pollen hydration, the lack of PME could impair pectin demethylation, affecting pollen tube germination54. The germination assays in vitro revealed a reduced number of germinated pollens in PMEKO plants compared to WT plants (Fig. 5f). Consistent with this phenotype, when selfing, the PMEKO plants produced fewer seeds per fruit, with the average seed number in WT plants exceeding that of PMEKO plants by over threefold (Fig. 5g, h). To further confirm these results and avoid the possible off-target effect, we conducted deep whole-genome sequencing (~60×) of 01-58 and three PMEKO plants. According to a reported method55, we identified 131 possible off-target sites (Supplementary Data 8) and detected no off-target effects at any of the possible 131 sites in three PMEKO plants. These results indicated that the phenotypes of PMEKO plants are caused by mutation of PME gene. In summary, the PME gene with the dominance heterotic effect confers superior pollen viability and enhanced pollen tube germination, leading to male fertility heterosis in hybrids.

Discussion

Mining functional genes is a critical part of plant biology and crop breeding. Based on genetic manipulations of functionally important genes, researchers have achieved de novo domestication breeding of wild tomato56 and rice57. A quantitative genomics map of rice was generated by utilizing mapped QTLs/genes to guide breeding58. Unlike these well-researched crops, progress in mapping of functional QTLs/genes in potato has been hampered by the complexities of tetrasomic inheritance. Potato is going through a green revolution via efforts to transform it into a seed-propagated diploid crop23,59, promising to greatly simplify genetic analyses. In this study, we conducted the large-scale genetic analysis of an inbred line-based F2 population comprising 1064 individuals. The parents A6-26 and E4-63 were derived from different lineages of S. tuberosum, with many traits segregating in the F2 population. Thanks to the advancements in omics technologies, we can now more quickly and accurately identify plant phenotypes at different levels compared to traditional manual surveys. In this study, we identified 20,382 traits and 25,770 QTLs using transcriptomics, metabolomics and phenomics (including RGB imaging, structured light imaging and hyperspectral imaging) technologies (Fig. 2a, Table 1, Supplementary Data 1, 2). Several phenotypes were mapped to previously reported loci, such as tuber shape29,42 and tuber flesh color41 (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting the reliability of our database. This QTL database will provide useful genetic markers for molecular breeding and gene discovery in potato.

Systems genetics combines genetics with gene expression analysis to explain complex traits7. In this study, we integrated multi-omics analyses to explore potato traits using the F2 population. Considering that any changes in gene expression would lead to later changes in the accumulation and composition of metabolites in tubers at a final mature stage, we advanced the sampling time for the transcriptome analysis to better correlate gene expression with the final metabolite content (see Methods). This approach has been proven effective15,60. Combined with QTL results, we constructed a systems-genetics network in this F2 population. Based on this network, we efficiently identified the master regulator GAME9 controlling solanine accumulation. Although the systems-genetics network can help to narrow down the suite of candidate genes, the traits affected by variations on protein function require further study (fine mapping, etc.). However, since the F2 population has experienced only one round of recombination, the average resolution of QTLs is ~190 kb in this study, making it difficult to directly identify candidate genes. Additionally, the high genomic and phenotypic diversity in this F2 population leads to many minor QTLs, hampering the identification of major QTLs. For example, we identified seven tuber yield QTLs in this study. TY1 with the highest LOD value explains only 6.55% and 4.21% of the phenotypic variance in 2021 and 2023, while the total explanation of all seven QTLs is 25.4% and 24.4%, respectively. Thus, a near-isogenic line population based on backcrosses is necessary to further fine-map promising genes and reduce the genetic variance to elevate the genetic effect of targeted QTLs. The genome information of the parental lines enables us to track the source of advantageous alleles and select the more suitable parent for backcrossing. Combined with genetic markers and whole-genome resequencing, this will turn complex quantitative traits into simple qualitative traits.

Heterosis has been extensively applied in hybrid crop breeding, particularly in maize and rice38,61. However, heterosis of clonally propagated crops has rarely been analyzed. Using the parental lines and their F1 hybrids, our previous study revealed the multi-omics basis of potato heterosis32. Here, we further explored the genetic basis of heterosis of the elite potato hybrid. The dominance, recessive and additive effects are the principal single-locus heterotic effects of yield-related traits, metabolites and gene expression, respectively (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 10). We found that hybrid tubers contain more dry matter and fewer metabolites content and over 60% of mQTLs show negative heterotic effects (Fig. 4d). This phenomenon might be explained by a trade-off theory between dry matter and small-molecule metabolites. As an energy sink of potato, tubers are storage compartments for dry matter62 that serves as the nutrition provider for asexual reproduction. In heterozygous-genotype tubers, the distribution of energy or resource utilization seems more rational, and energy or resources might preferentially flow to fuel the synthesis of dry matter leading to a relatively lower small-molecule metabolites in hybrids. Similar results were also found in maize63 and Arabidopsis64. Moreover, we identified a PME gene with a dominance heterotic effect involved in male fertility in potato. The advantageous allele comes from A6-26 and confers better pollen viability and more seeds for hybrids, potentially explaining the dominant effect.

However, we did not identify epistatic interactions between the 24 yield-related QTLs in both years. To further identify the interactions on the whole genome-wide (all markers involved), backcross populations can be developed to reduce the genetic diversity within the population, because the interactions in the F2 population are complex and hard to be detected accurately65. This process can be carried out simultaneously with the construction of introgression lines. Therefore, we believe that for genetic studies on this population, F2-derived populations should be primarily constructed. This approach not only focuses on cloning genes associated with agronomically important traits but also aims to utilize key genetic loci for improvement of diploid inbred lines.

Overall, molecular breeding and functional genomics study in diploid potatoes are still in its infancy. This study provides valuable genetic and phenotypic resources for the potato community. By integrating multi-omics data to construct a systems genetics network, along with studies on heterosis, our findings in this work contribute to gene discovery and enhance our understanding of the genetic basis of heterosis in potatoes.

Methods

Plant materials

The parents and their F1 hybrid (A6-26 × E4-63) were developed in a previous study23. The homozygosity of the parents is 98.16% and 98.52% for A6-26 and E4-63, respectively. The F2 population was generated through selfing the F1 hybrid. The 1064 F2 individuals were randomly selected. Each F2 individual was planted on MS medium for permanent preservation by tissue culture.

Construction of the genotype map and genetic map

Genomic DNA of the 1064 lines was extracted from fresh leaves by the CTAB method. Whole-genome sequencing was conducted on the DNBSEQ platform at Annoroad Gene Technology company (Beijing, China). For each line, ~2 Gb clean data with 150-bp read length were generated. The clean reads were aligned against the E4-63 reference genome23 using BWA (0.7.5a-r405)66. GATK (v4.2.1.0) was used to mark duplicated reads67. We used SAMtools (v.1.9)68 and BCFtools (v.1.9)66 to extract SNPs. The SNPs between two parents were identified based on 50× DNA resequencing data32. The SNPs were further filtered with base quality ≥ 40, mapping quality ≥ 30 and 20 ≤ depth ≤ 100, and only “1/1” genotype was reserved. Then, these filtered SNPs were used to construct a parent SNP database. Only SNPs of F2 individuals in this database were reserved for subsequent analyses (use BCFtools parameter -R). The genotype map was constructed by calculating the genotype of each bin21,69. A total of 2475 bins were identified in the genotype map of 1064 individuals. For genetic map construction, we fed the bins of the genotype map to QTL IciMapping (v4.2)70.

Segregation distortion analysis

In the F2 population, the expected segregation ratios of zygotes and gametes are 1:2:1 and 1:1, respectively. The χ2 test was applied to determine the significance between the observed segregation ratio and the expected segregation ratio with a cutoff value of P = 0.001.

Collection of phenome data

Individuals used for collecting different traits are listed in Supplementary Data 1. In 2021 and 2023, the 1064 individuals were cultivated with three replicates in Kunming, China. Plant height, tuber yield, tuber number, and tuber size were assessed in both years, while flowering time and pollen viability were investigated in 2021. Yield-related traits (plant height, flowering time, tuber yield, tuber size and tuber number) and the qualitative traits (Supplementary Fig. 3) were measured manually. The individuals used for BSA are listed in Supplementary Data 1. For BSA, 20–50 individuals according to the different traits were selected as a pool (Supplementary Data 1). Using our previously developed high-throughput phenotyping facility71, 38 aboveground traits were identified with an RGB camera using two photo angles (from the top and from the sides) at 60 days after transplanting (Supplementary Data 1). With the RGB imaging device, six side-view images and one top-view image of each plant were taken from a fixed horizontal projection of equal angles. Using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging (1000–1700 nm, Headwall Hyperspec Starter Kit-VNIR, USA) and a visible-light hyperspectral imaging (400–1000 nm, Headwall VNIR A-Series, USA), the mature tubers were scanned, and 488 hyperspectral traits were analyzed using hyperspectral image-analysis pipeline72,73 (Supplementary Method 1). Mature tubers were scanned using the structured light imaging (Reeyee Pro, WIIBOOX, China), and five tuber traits were analyzed using structured light image analysis pipeline74 (Supplementary Method 1). Potato image processing, image trait extraction and definition of the macro-phenomics traits are explained in Supplementary Methods 1 and 2. For each F2 individual, three replicates were phenotyped in our experiment. The average values of all traits were used for the further genetic analyses.

To determine the elements regulating gene expression, we conducted transcriptome sequencing of developing tubers of 204 F2 individuals (80 days after transplanting) that were randomly selected. To ensure the accuracy of subsequent analyses, genes with low expression level (FPKM < 1) in over 90% of the 204 samples were filtered out. Finally, 19,166 expressed genes remained after our filtering steps, accounting for 40.4% of all annotated genes.

We applied an ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) approach to detect metabolite content in mature tubers of 215 F2 individuals (120 days after transplanting), of which 191 are shared with the transcriptome dataset. The other 24 samples were selected randomly. We thus identified 679 metabolites. The individuals used for detecting transcriptomes and metabolomes were selected randomly. The metabolome and transcriptome data of parents sampled at the same stage have been reported32.

Metabolite detection

For each sample, three mature tubers in 2021 were freeze-dried and mixed. The tuber extracts were analyzed using a UPLC-MS/MS system. The UPLC was equipped with a 1.8 µm, 2.1 mm * 100 mm Agilent SB-C18 column. The mobile phase included pure water with 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (solvent B). The column temperature was set to 40 °C and the injection volume was 4 μL. Metabolites were quantified by multiple reaction monitoring mode (MRM) of MS/MS with collision gas (nitrogen) set to medium. According to the metabolites eluted, a specific set of MRM transitions was monitored for each period. Analyst (v1.6.3) software (https://sciex.com/products/software/analyst-software) was used to assess and quantify the MS data.

Transcriptome profiling

Total RNA was extracted from three developmental tubers (mixed together) collected at 80 days after transplanting in 2021 and sequenced on the DNBSEQ platform at the China National GeneBank (Shenzhen, China). The raw data were filtered to remove low‐quality reads and adapters using SOAPnuke (v1.5.6)75. Then, the ~4 Gb clean reads for each sample were mapped to the E4-63 reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)76. Gene expression levels were quantified using FPKM values, calculated using StringTie (v2.1.1)77.

QTL mapping

QTL mapping was carried out by R/qtl using the composite interval-mapping method78. Bins with LOD values > 3.5 were selected. Consecutive QTLs (LOD > 3.5) were merged and considered as one QTL. Gene expression levels were normalized with quantile–quantile normalization.

eQTL analysis

The eQTLs were divided into local and distant eQTLs based on their distance from the corresponding genes. To identify local eQTLs, we selected the flanking bins of the peak-containing bin as the eQTL borders. If the distance of the interval of flanking bins is within 100 kb with the regulated gene, the eQTL was defined as a local eQTL; otherwise, it was considered a distant eQTL. The distant eQTL hotspots were identified by 10,000 permutation tests. In each permutation, all distant eQTLs were randomly assigned to each 1-Mb genomic interval. Then, numbers of distant eQTLs in each interval were counted to determine hotspots with a cutoff p-value < 0.01.

Correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients and p-values were calculated using the R package ‘Hmisc’ using the ‘rcorr’ function79. The R package ‘corrplot’ was used to visualize the results79.

Construction of the systems-genetics network

First, WGCNA was performed to identify gene modules using the R package WGCNA80. The soft-thresholding power b was set to 16. We identified 21 gene modules. The online tool (https://cloud.metware.cn) was used to conduct GO and KEGG analyses. The “corPvalueStudent” function of WGCNA was used to analyze relationships of gene modules/genes and traits. The triple relationships were linked by QTLs. To ensure the reliability of results, only QTLs with LOD values > 5.0 were considered for triple-relationship analysis. We selected QTLs associated with both classes of traits (i.e. metabolites and yield-related traits, data from 2021) and gene expression, and we then merged QTLs within 30 kb. The triple relationships were visualized with Cytoscape software81. The WGCNA data coupled with the triple relationships comprise the systems-genetics network.

Evaluation of single-locus effects

The degree of dominance for each QTL was estimated by the ratio of dominant effect/additive effect (d/a). The dominant effect (d) rests on the difference between the heterozygous genotypes and mid-parent values. The additive effect (a) is determined by half the difference between the two homozygous genotypes. The genetic model was further partitioned into five types using the following standards40: (1) overdominance: d/a ≥ 1.25; (2) dominance (including partial dominance): 0.25 ≤ d/a < 1.25; (3) additive effect: −0.25 ≤ d/a < 0.25; (4) recessive effect (including partial recessive effect): −1.25 < d/a < −0.25; (5) underdominance: d/a ≤ −1.25.

Detection of pollen viability and pollen tube germination assay

The mature pollen grains were collected from freshly opened flowers. Then, the pollen grains were stained using 0.4% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sangon Biotech) at 37 °C for 20 min. After staining, the pollen solution was dispensed onto a glass slide and the red pollen grains (good viability) were observed under the microscope.

Ca2+ and boric acid are necessary substances for the in vitro germination of potato pollen. In this study, we used a medium containing 17% sucrose, 0.05% CaCl2, 0.01% boric acid and 0.05 % agar. The pollen grains were incubated in medium at 28 °C in the dark for 20 hours, and the pollen tube germination was observed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Xuehui Huang (Shanghai Normal University) for critical comments. This work was supported by Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research to S.H. (2021B0301030004), Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ZDRW202404), Natural Science Foundation of China to C.Z. (32022075), Natural Science Foundation of China to D.L. (32302541), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (BX20230426) to D.L., National Key Research and Development Plan (2022YFD2002304) to W.Y., National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20205) to W.Y. and Key Projects of Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2021CFA059) to W.Y.

Author contributions

C.Z., S.H., and W.Y. conceived the project and designed the study. D.L., P.W., and Y.Z. constructed the F2 population. X.J. and H.D. contributed to the construction of the genotype and genetic map. D.L. collected the genomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic data. Z.G., S.X., H.F., D.L., C.H., and Q.L. collected and analyzed the phenome data. D.L. conducted the genetic and heterotic analysis. G.Z. and Y.S. provided the computing platform. H.L., Y.J., Yao Z., and Y.W. assisted in bioinformatics analyses. D.L. wrote the draft manuscript. D.L., T.S., S.H., C.Z., and W.Y. revised to develop the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The metabolome data have been deposited at the potato multi-omics database [http://solomics.agis.org.cn/potato/ftp/Metabolomics_of_potato_tuber/]. The macro-phenome data are available in Supplementary Data 1. The whole-genome sequencing and transcriptome data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with BioProject accession number PRJNA878602. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dawei Li, Zedong Geng.

Contributor Information

Wanneng Yang, Email: ywn@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Sanwen Huang, Email: huangsanwen@caas.cn.

Chunzhi Zhang, Email: zhangchunzhi01@caas.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-53044-4.

References

- 1.Peters, J. L., Cnudde, F. & Gerats, T. Forward genetics and map-based cloning approaches. Trends Plant Sci.8, 484–491 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneeberger, K. & Weigel, D. Fast-forward genetics enabled by new sequencing technologies. Trends Plant Sci.16, 282–288 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han, K. et al. QTL mapping and GWAS reveal candidate genes controlling capsaicinoid content in Capsicum. Plant Biotechnol. J.16, 1546–1558 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackay, T. F., Stone, E. A. & Ayroles, J. F. The genetics of quantitative traits: challenges and prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet.10, 565–577 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindhout, P. et al. Towards F1 hybrid seed potato breeding. Potato Res.54, 301–312 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Civelek, M. & Lusis, A. J. Systems genetics approaches to understand complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet.15, 34–48 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li, J. & Burmeister, M. Genetical genomics: combining genetics with gene expression analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet.14, R163–R169 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen, R. C. & Nap, J. P. Genetical genomics: the added value from segregation. Trends Genet.17, 388–391 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadarmideen, H. N., von Rohr, P. & Janss, L. L. From genetical genomics to systems genetics: potential applications in quantitative genomics and animal breeding. Mamm. Genome17, 548–564 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emilsson, V. et al. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature452, 423–428 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert, F. W. & Kruglyak, L. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet.16, 197–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu, Z. et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet.48, 481–487 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, R. Z. et al. A systems genetics approach reveals PbrNSC as a regulator of lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruit. Genome Biol.22, 313 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keurentjes, J. J. B. et al. Regulatory network construction in Arabidopsis by using genome-wide gene expression quantitative trait loci. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA104, 1708–1713 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu, G. et al. Rewiring of the fruit metabolome in tomato breeding. Cell172, 249–261 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokstad, E. The new potato. Science363, 574–577 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye, M. et al. Generation of self-compatible diploid potato by knockout of S-RNase. Nat. Plants4, 651–654 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enciso-Rodriguez, F. et al. Overcoming self-incompatibility in diploid potato using CRISPR-Cas9. Front. Plant Sci.10, 376 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggers, E. J. et al. Neofunctionalisation of the Sli gene leads to self-compatibility and facilitates precision breeding in potato. Nat. Commun.12, 4141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma, L. et al. A nonS-locus F-box gene breaks self-incompatibility in diploid potatoes. Nat. Commun.12, 4142 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, C. et al. The genetic basis of inbreeding depression in potato. Nat. Genet.51, 374–378 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou, Q. et al. Haplotype-resolved genome analyses of a heterozygous diploid potato. Nat. Genet.52, 1018–1023 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, C. et al. Genome design of hybrid potato. Cell184, 3873–3883 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansky, S. H. et al. Reinventing potato as a diploid inbred line-based crop. Crop Sci.56, 1412–1422 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, Y., Li, G., Li, C., Qu, D. & Huang, S. Prospects of diploid hybrid breeding in potato. Chin. Potato J.27, 96–99 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang, D. et al. Genome evolution and diversity of wild and cultivated potatoes. Nature606, 535–541 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prashar, A. et al. Construction of a dense SNP map of a highly heterozygous diploid potato population and QTL analysis of tuber shape and eye depth. Theor. Appl. Genet.127, 2159–2171 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, X. Q., De Jong, H., De Jong, D. M. & De Jong, W. S. Inheritance and genetic mapping of tuber eye depth in cultivated diploid potatoes. Theor. Appl. Genet.110, 1068–1073 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Eck, H. J. et al. Multiple alleles for tuber shape in diploid potato detected by qualitative and quantitative genetic analysis using RFLPs. Genetics137, 303–309 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endelman, J. B. & Jansky, S. H. Genetic mapping with an inbred line-derived F2 population in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet.129, 935–943 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, D. et al. Dissected Leaf 1 encodes an MYB transcription factor that controls leaf morphology in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet.136, 183 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, D. et al. The multi-omics basis of potato heterosis. J. Integr. Plant Biol.64, 671–687 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birchler, J. A., Yao, H., Chudalayandi, S., Vaiman, D. & Veitia, R. A. Heterosis. Plant Cell22, 2105–2112 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruce, A. B. The Mendelian theory of heredity and the augmentation of vigor. Science32, 627–628 (1910). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lippman, Z. B. & Zamir, D. Heterosis: revisiting the magic. Trends Genet.23, 60–66 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crow, J. F. Alternative hypotheses of hybrid vigor. Genetics33, 477–487 (1948). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger, U., Lippman, Z. B. & Zamir, D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet.42, 459–463 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, Z. J. Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nat. Rev. Genet.14, 471–482 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang, X. et al. Genomic architecture of heterosis for yield traits in rice. Nature537, 629–633 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, H. et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of heterotic loci in three maize hybrids. Plant Biotechnol. J.18, 185–194 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kloosterman, B. et al. From QTL to candidate gene: genetical genomics of simple and complex traits in potato using a pooling strategy. BMC Genomics11, 158 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonierbale, M. W., Plaisted, R. L. & Tanksley, S. D. RFLP maps based on a common set of clones reveal modes of chromosomal evolution in potato and tomato. Genetics120, 1095–1103 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Jong, W. S., De Jong, D. M., De Jong, H., Kalazich, J. & Bodis, M. An allele of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase associated with the ability to produce red anthocyanin pigments in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet.107, 1375–1383 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang, C., Ma, Y., He, Y., Tian, Z. & Li, J. OsOFP19 modulates plant architecture by integrating the cell division pattern and brassinosteroid signaling. Plant J.93, 489–501 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, S. et al. A common genetic mechanism underlies morphological diversity in fruits and other plant organs. Nat. Commun.9, 4734 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vergara-Diaz, O. et al. Assessing durum wheat ear and leaf metabolomes in the field through hyperspectral data. Plant J.102, 615–630 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu, N. et al. Predicting micronutrients of wheat using hyperspectral imaging. Food Chem.343, 128473 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu, S. et al. MODAS: exploring maize germplasm with multi-omics data association studies. Sci. Bull.67, 903–906 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cardénas, P. D. et al. GAME9 regulates the biosynthesis of steroidal alkaloids and upstream isoprenoids in the plant mevalonate pathway. Nat. Commun.7, 10654 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Itkin, M. et al. Biosynthesis of antinutritional alkaloids in solanaceous crops is mediated by clustered genes. Science341, 175–179 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krawczyk, S., Thurow, C., Niggeweg, R. & Gatz, C. Analysis of the spacing between the two palindromes of activation sequence-1 with respect to binding to different TGA factors and transcriptional activation potential. Nucleic Acids Res.30, 775–781 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardigan, M. A. et al. Genome diversity of tuber-bearing Solanum uncovers complex evolutionary history and targets of domestication in the cultivated potato. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, E9999–E10008 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yue, X., Lin, S., Yu, Y., Huang, L. & Cao, J. The putative pectin methylesterase gene, BcMF23a, is required for microspore development and pollen tube growth in Brassica campestris. Plant Cell Rep.37, 1003–1009 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haas, K. T., Wightman, R., Peaucelle, A. & Höfte, H. The role of pectin phase separation in plant cell wall assembly and growth. Cell Surf.7, 100054 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin, S. et al. Genome-wide specificity of prime editors in plants. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1292–1299 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li, T. et al. Domestication of wild tomato is accelerated by genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol.36, 1160–1163 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, H. et al. A route to de novo domestication of wild allotetraploid rice. Cell184, 1156–1170 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei, X. et al. A quantitative genomics map of rice provides genetic insights and guides breeding. Nat. Genet.53, 243–253 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu, Y. et al. Phylogenomic discovery of deleterious mutations facilitates hybrid potato breeding. Cell186, 2313–2328.e15 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao, K. et al. Combined nature and human selections reshaped peach fruit metabolome. Genome Biol.23, 146 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu, J., Li, M., Zhang, Q., Wei, X. & Huang, X. Exploring the molecular basis of heterosis for plant breeding. J. Integr. Plant Biol.62, 287–298 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dwelle, R. B. Source/sink relationships during tuber growth. Am. Potato J.67, 829–833 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romisch-Margl, L. et al. Heterotic patterns of sugar and amino acid components in developing maize kernels. Theor. Appl. Genet.120, 369–81 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyer, R. C. et al. The metabolic signature related to high plant growth rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.104, 4759–4764 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanksley, S. D. & Nelson, J. C. Advanced backcross QTL analysis: a method for the simultaneous discovery and transfer of valuable QTLs from unadapted germplasm into elite breeding lines. Theor. Appl. Genet.92, 191–203 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res.20, 1297–303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang, X. et al. High-throughput genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res.19, 1068–1076 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meng, L., Li, H. H., Zhang, L. Y. & Wang, J. K. QTL IciMapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J.3, 269–283 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang, W. et al. Combining high-throughput phenotyping and genome-wide association studies to reveal natural genetic variation in rice. Nat. Commun.5, 5087 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feng, H. et al. An integrated hyperspectral imaging and genome-wide association analysis platform provides spectral and genetic insights into the natural variation in rice. Sci. Rep.7, 4401 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu, X. et al. Using high-throughput multiple optical phenotyping to decipher the genetic architecture of maize drought tolerance. Genome Biol.22, 185 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qin, Z. et al. Cereal grain 3D point cloud analysis method for shape extraction and filled/unfilled grain identification based on structured light imaging. Sci. Rep.12, 3145 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. GigaScience7, 120 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 907–915 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol.33, 290–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Broman, K. W., Wu, H., Sen, S. & Churchill, G. A. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics19, 889–890 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

- 80.Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform.9, 559 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13, 2498–2504 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The metabolome data have been deposited at the potato multi-omics database [http://solomics.agis.org.cn/potato/ftp/Metabolomics_of_potato_tuber/]. The macro-phenome data are available in Supplementary Data 1. The whole-genome sequencing and transcriptome data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with BioProject accession number PRJNA878602. Source data are provided with this paper.