Abstract

Unleashing prodrugs through nitro-reduction is a promising strategy in cancer treatment. In this study, we present a unique bioorthogonal reaction for aromatic nitro reduction, mediated by 4,4‘-bipyridine. The reaction is a rare example of organocatalyst-mediated bioorthogonal reaction. This bioorthogonal reaction demonstrates broad substrate scope and proceeds at low micromolar concentrations under biocompatible conditions. Our mechanistic study reveals that water is essential for the reaction to proceed at biorelevant substrate concentrations. We illustrate the utility of our reaction for controlled prodrug activation in mammalian cells, bacteria, and mouse models. Furthermore, a nitro-reduction-annulation cascade is developed for the synthesis of indole derivatives in living cells.

Subject terms: Drug delivery, Chemical biology, Chemical tools

Releasing prodrugs through nitroreduction is a promising strategy in cancer treatment. In this study, the authors present a 4,4‘-bipyridine-mediated bioorthogonal aromatic nitro reduction for activation of nitro prodrugs.

Introduction

Controlled prodrug activation is a general strategy to improve drug delivery efficiency and reduce toxicity in cancer treatment. The development of efficient bioorthogonal reactions or click chemistry1–7 has sparked new interest in using chemical biology approaches for prodrug activation. Clinically, the most advanced example is SQP33, a trans-cyclooctene (TCO)-caged doxorubicin prodrug that is unleashed at the tumor site via TCO-tetrazine ligation8,9. Phase 1/2a clinical trial in advanced solid tumors indicated that SQ3370 is safe, well tolerated, and induces a cytotoxic T-cell supportive tumor microenvironment. A common approach to deliver cytotoxins to tumor cells is the use of antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). Compared to traditional ADCs, the potential advantage of click-to-release strategy for prodrug activation by inverse electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction (IEDDA) includes the ability to target non-internalizable receptors, the flexibility to tune the drug-antibody-ratio throughout drug development, and the ease of choosing different payloads during treatment. Other strategies leveraging bioorthogonal reactions have also been reported that hold the potential for prodrug activation in clinical applications10–32. Despite these advances, development of fast and efficient bioorthogonal reactions is the keystone to advance this field.

Selective reduction of aromatic nitro group is an appealing strategy for prodrug activation. Hypoxia is a common phenomenon in the majority of solid tumors33,34. Hypoxia-activated prodrugs (HAP) are a promising class of anticancer drugs that can selectively target hypoxic tumor cells35. The majority of these prodrugs rely on one-electron reduction of nitroarenes to generate a potent cytotoxin in hypoxic tumors. Despite extensive research interest into this class of prodrugs, there has been limited clinical success to date, with two compounds (CP-506 and tarloxotinib) in clinical trial and no FDA approval yet. The major reason for the limited success of this strategy is the complex heterogeneous nature of solid tumors and a lack of widely accessible and reliable biomarkers for hypoxia in clinic36. Heterologous expression of Nitroreductase is another promising strategy for the activation of nitroaromatic prodrugs. The Nitroreductase enzyme can efficiently reduce various nitroaromatic substrates utilizing either NADPH or NADH as cofactors37. These enzymes have been widely used as activating enzymes for nitroaromatic prodrugs of the dinitrobenzamide class38. 5-(aziridin-1-yl)−2,4-dinitrobenzamide (CB1954), an anticancer prodrug, is reduced by Escherichia coli nitroreductase NfsB to yield the 2-and 4-hydroxylamines, which is further metabolized to induce crosslinking of DNA and rapid cell death39. Albeit entered Phase II clinical trial, the efficacy of this approach is limited by low enzymatic efficiency and low overall gene transfection efficiency40. New strategies that can bypass the intrinsic biological properties of the tumor cells to improve the activation efficiency of nitroaromatic prodrugs are needed in order for advancing these prodrugs in cancer therapeutics.

Synthetically, practical methods for the reduction of aromatic nitro groups include the use of metal powders or hydrogenation by heterogeneous catalysts41–49. However, such methods require harsh reaction conditions and the use of toxic metals thus are not compatible with biological environment. Elegant work by Weng et al. demonstrated the first example of biocompatible nitroarene reduction by a metallo−nitroreductase complex for targeting pathogenic formate-dependent bacteria50. Although it paved a new way for antibacterial chemotherapeutics, the application of this method in mammalian cells as well as in animal models remains to be demonstrated.

We envisioned that metal- and enzyme-free aromatic nitro reduction conditions would be more biocompatible. A few examples of diboron-mediated chemoselective nitro reduction51–54 have been brought to our attention because element boron is biocompatible. Recently, reduction of enamine N-oxide by diboron reagents has been utilized as a dissociative on-demand strategy for drug release29.

Herein, we report our efforts on the development of a 4,4‘-bipyridine-mediated aromatic nitro reduction reaction for prodrug activation (Fig. 1), which is a rare example of bioorthogonal reactions mediated by an organocatalyst. The reaction proceeds at low micromolar concentration under biocompatible conditions. We discovered that water plays a critical role in enabling the reaction at biologically relevant substrate concentrations. We demonstrate that this prodrug activation reaction is compatible in mammalian cells, bacteria, and animal models. In addition, we showcase a 4,4’-bipyridine-mediated reduction-annulation cascade for the synthesis of indole derivatives in living cells.

Fig. 1. 4,4‘-bipyridine-mediated aromatic nitro reduction for prodrug activation in mammalian cells, bacteria and animal models.

(Created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en).

Results

In previous reports, 4,4’-bipyridine-catalyzed nitro reduction proceeds either at high temperature or in organic solvents51–54. To explore whether this reaction can be conducted in aqueous solution under mild conditions, we began to screen various diboron reagents using 5-nitro-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1a) as the model substrate. The reaction was significantly affected by the substitutions on the boron atom: reduction of 1a in the presence of B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine in DMSO: PBS (1: 9) at 37 °C gave near quantitative yields (98%, Supplementary Table 1, entry 1), while the yields decreased dramatically when replacing B2(OH)4 with B2hex2 (Supplementary Table 1, entry 3). 2a was obtained in 65% or 92% yields when B2nep2 or B2pin2 was used (Supplementary Table 1, entry 2, 4). Mechanistic investigation indicated that the different reactivity of diboron reagents relates to their ability to hydrolyse to B2(OH)4. The hydrolysis products of B2nep2 and B2pin2 were observed after 30 min in DMSO: H2O (1:9), while no hydrolysis was observed for B2hex2 under the same conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Considering the low solubility of B2pin2 in water, we continued our screen with B2(OH)4. Lowering the amount of B2(OH)4 or 4,4’-bipyridine decreased the yields of 2a (Supplementary Table 1, entry 4–9).

Having established the optimal conditions, we evaluated the substrate scope. Heterocyclic compounds 5-nitro-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (Table 1, 1a) and 5-nitro-indole (1b) gave near quantitative yields. Fluorescent dyes 5-nitro-coumarine (1c) and 5-nitro-tetramethylrhodamine (1d) were reduced to the corresponding anilines 2c and 2d in 82% and 63% yields. Nitroarene 1e and 1 f were converted to the sulfonamide-derived antibacterial drug Sulfanilamide (2e) and Sulfamethazine55 (2f) in 96% and 90% yields, respectively. Nitro reduction of prodrugs 1g-1k gave the corresponding anilines, including a voltage-gated potassium channel blocker Amifampridine56 (2g), an antiinflammatory agent Mesalazine57 (2h), local anesthetic Benzocaine58 (2i), Procainamide59 (2j), and an immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide60,61 (2k) in good to excellent yields.

Table 1.

Substrate Scope for the Reduction of Aromatic Nitro Compoundsa,b

aReaction conditions: substrates 1a–k (500 μM), diboron reagents (10 mM, 20 equiv.), 4,4’-bipyridine (2.5 mM, 5 equiv.) in DMSO: PBS (1:9) at 37 °C for 30 min. bYields were determined by HPLC using a standard curve. cYields determined by NMR analysis using DSS as the internal standard. dIsolated Yields.

Next, we probed the mechanism of this reaction. We conducted the reduction of 1c in deuterated DMSO or d6-DMSO/D2O at 500 μM concentration, and the crude mixture was analyzed by 1H-NMR. When the reaction was performed in deuterated DMSO, no product was formed, and the starting material 1c was recovered (Fig. 2A(a)). However, full conversion of 1c to deuterated 2c was observed in d6-DMSO/D2O (1:9) (Fig. 2A, B). The formation of deuterated 2c was further confirmed by HR-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). To exclude the possibility that 1c is not a suitable substrate for nitro reduction in DMSO, we repeated the reaction in DMSO with 1a and 1e (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Again, at 500 μM substrate concentration, we observed no reactivity in DMSO, but the reactions proceed to give near quantitative 2a and 2e in DMSO/H2O (1:9). To further confirm the importance of H2O, we conducted the nitro-reduction of 1c at 500 μM with different ratios of DMSO and H2O as solvent. We observed an increase of reaction yields when higher ratio of H2O was used (Supplementary Fig. 5). The observation that H2O is indispensable is different from the previous report50 that the reaction can proceed in either DMF or DMSO. To probe into this inconsistency, we conducted the reaction with 150 mM 1c in DMSO. The reduction product 2c was obtained in 87% NMR yield (Fig. 2B). The reaction yields dropped significantly when the concentration of 1c is below 25 mM in DMSO (Supplementary Fig. 6). Reduction of nitrosobenzene at 500 μM concentration also requires H2O (Supplementary Fig. 7). These experiments confirmed the critical role of water for the nitro reduction reaction at low substrate concentrations. Previous mechanistic investigation indicated the formation of a catalytically active boron-coordinated 4,4‘-bipyridinylidene62,63. To probe whether formation of this complex might also requires water. We monitored the mixture of 4,4‘-bipyridine and B2(OH)4 by 1H- and 11B-NMR. We observed shifts of NMR peaks when using d6-DMSO and D2O as the solvent. The peak shifts were not seen when using d6-DMSO alone. This NMR study indicated that water might also play a role in assiting the formation of the 4,4‘-bipyridine-B2(OH)4 complex (Supplementary Fig. 8). We then studied the kinetics of the reaction. We monitored the fluorescence intensity of 2c upon addition of B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine to 1c at different concentrations by a micro-plate reader. Reaction progress kinetic analysis revealed a pseudo-first-order kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 9) with the rate constant of 1.5 × 10−3 s−1 at 37 °C. The reaction kinetics using 4,4’-bipyridine derivatives as the catalysts were also determined. 2,6-dimethyl-4,4’-bipyridine, 2,6-dichloro-4,4’-bipyridine and 2-trifluoromethyl-4,4’-bipyridine showed faster reaction rate (k = 3.0 × 10−3 s−1, 2.3 × 10−3 s−1 and 2.1 × 10−3 s−1, respectively), indicating that tuning of the 4,4’-bipyridine core can further improve the efficiency of this transformation (Supplementary Fig. 10). Furthermore, we measured the kinetics of 4,4’-bipyridine and B2(OH)4. Both 4,4’-bipyridine and B2(OH)4 showed zero-order kinetics, indicating that these reagents are not involved in the rate-limiting step (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Fig. 2. The mechanistic and kinetic study of the aromatic nitro reduction.

A (a) Crude 1H-NMR (red) of the nitro reduction of 1c under the optimized conditions (500 μM 1c, 20 eq. B2(OH)4 and 5 eq. 4,4’-bipyridine) at 37 °C in d6-DMSO. Standard 1H-NMR of 1c (purple) were shown. (b) Crude 1H-NMR (green) of the nitro reduction of 1c (150 mM) under the optimized conditions (3 eq. B2(OH)4 and 0.5 mol%. 4,4’-bipyridine) at 37 °C in d6-DMSO; Crude 1H-NMR (red) of the nitro reduction of 1c (500 μM) under the optimized conditions (20 eq. B2(OH)4 and 5 eq. 4,4’-bipyridine) at 37 °C in d6-DMSO: D2O (1:9). Standard 1H-NMR of 2c (purple) were shown. B Summary of the NMR study in A). The yield of the 500 μM reaction was calculated by HPLC analysis, and the yield of the 150 mM reaction was calculated by 1H-NMR.

To test whether our nitro reduction reaction is compatible with living cells, we incubated THP-1 cells with 50 μM 1d. The fluorescence of 1d was quenched by the nitro group via PeT mechanism64, while reduction of 1d to 2d restored the fluorescence (Fig. 3A). Addition of B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine increased the fluorescence intensity of the cells, as observed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3B, C), indicating that the reaction can proceed in biocompatible conditions. To investigate whether the reduction product can be obtained inside living cells, we treated 1d-CA with HeLa cells stably expressing Halo-NES. 1d-CA will covalently conjugated to Halo-NES to avoid its diffusion out of the living cells. After extensive washing steps, we treated the cells with B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine for another 2 h. Again, we observed an increase of fluorescence inside the cells (Supplementary Fig. 12), showing that this reaction is compatible within the cellular context. To estimate the reaction efficiency in cultured cells, we incubated 10 μM or 20 μM of the reduction product 2d with THP-1 cells for 2 h and quantified the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3B). Our quantification data indicates that the reaction yields was in the range of 20–40% in cultured cells (Fig. 3C). To further quantify the reaction yields in cultured cells, we incubated the cells with different concentrations of 2d (5–50 μM), analysed the mean fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry and plotted a standard curve (fluorescence intensity vs concentration of 2d, Supplementary Fig. 13). The reaction yields was 34% when using 50 μM of 1d, as calculated according to the standard curve (Supplementary Fig. 13). The result is consistant with our confocal analysis. Although the lipophilicity of B2pin2 might facilitate its cell penetration, the reduction of 1d by B2pin2/4,4’-bipyridine in cellulo gave same yields (34%, Supplementary Fig. 13). However, we speculated that the fluorescence measurement might underestimate the reaction yields inside the cells since the rhodamine derivative 2d could shift to a spirolactone nonfluorescence form in hydrophobic environment65 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Due to the hydrophobic nature of 2d, the compound might stick to hydrophobic membranes inside living cells thus become non-fluorescent. To measure the reaction conversion in cellulo, we subjected the cells treated with 1d, B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine to quantitative MS analysis. Cells treated with 1d alone were set as the control group. Satisfyingly, the remaining 1d after the reaction was 0.39 ng in 2.5 × 106 cells, compared to 37.78 ng in 2.5 × 106 cells in the control group (conversion >98 %). The reduction product 2d was obtained in 33.71 ng in 2.5 × 106 cells (Supplementary Fig. 15). The toxicity of B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine was measured by Cell Counting-Lite 2.0 assay in 293 T, HeLa and THP-1 cells. Cell viability was not significantly affected by these reagents (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Fig. 3. Nitro reduction of 1d in living cells.

A Schematic illustration for the reduction of 1d. B Confocal fluorescence images of live THP-1 cells treated with different conditions (1d: 50 μM, BP: B2 (OH)4: 1.5 mM and 4,4’-Bipyridine: 250 μM, 2d: 10 μM and 20 μM). C Quantification of fluorescence intensity in (B), Data represent the mean intensity of fifteen randomly chosen cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 15 samples). P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ****P < 0.0001. Scale bars: 20 μm. Original data are provided in Source Data file.

Immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs), such as lenalidomide, thalidomide, pomalidomide and iberdomide66, are widely used as immunomodulatory drugs for treating multiple myeloma via inducing the degradation of IKZF1/3 (Ikaros zinc finger transcription factor 1/3), Ikaros family transcriptional factors by engaging the E3 ligase CRBN67. To demonstrate the utility of our nitro-reduction protocol as a complementary strategy for controlled prodrug activation, we designed and synthesized 3, a prodrug of iberdomide, by caging the glutarimide nitrogen with a reductive-labile para-nitro aryl carbamate group68 (Fig. 4A). A total of 500 μM prodrug 3 was treated with 20 eq. B2(OH)4 and 5 eq. 4,4’-bipyridine. Release of the active compound iberdomide after 30 min was confirmed by HPLC (Fig. 4B). Treatment of 4 (Iberdomide) causes degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in human multiple myeloma cells MM.1S (Supplementary Fig. 17). We treated MM.1S cells with increasing concentrations of 3 and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine for 14 h and analyzed the protein level of IKZF1/3 by western blot. Gratifyingly, robust degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 was observed with 5 μM 3 and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine (Fig. 4C). As a negative control, addition of prodrug 3 alone showed minimal IKZF1/3 degradation. Neddylation of CUL4, a CRBN adaptor protein, is necessary for proper assembly and function of the CRBN E3 ligase complex. To confirm the degradation was indeed proceeded via the ubiquitin- proteasome pathway, MM.1S cells were treated with 1 μM of the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 before being treated with 5 μM prodrug 3 and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine. Addition of MLN4924 rescued IKZF1/3 levels, suggesting the degradation is neddylation-dependent. Furthermore, treatment of B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine only did not degrade IKZF1/3 (Fig. 4D). In addition, we tested the toxicity of 5 μM prodrug 3 and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine by Cell Counting-Lite 2.0 assay in HeLa, 293 T, THP-1 and MM.1S cells to exclude the effect of toxicity on the degradation effect (Supplementary Fig. 18). Decaging byproducts formaldehyde and ammonia did not cause degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 (Supplementary Fig. 18).Taken together, these results not only demonstrate the utility of our nitro-reduction reaction for prodrug activation in mammalian cells, but also provide a complementary strategy for controlled protein degradation.

Fig. 4. Nitro reduction of prodrug 3 in MM.1S cells.

A Schematic illustration for reduction of 3. B HPLC analysis of the Nitro reduction of prodrug 3. C Dose- dependent degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in MM.1S cells by activated prodrug 3. The concentrations of 3 were set to 0.1 μM, 0.5 μM, 1 μM, 5 μM, with the addition of 30 eq. B2(OH)4 and 5 eq. 4,4’-Bipy. The cells were shaken for 2 h, followed by 12 h static incubation. D Control experiments. The cells were shaken with 5 μM 3, 150 μM B2 (OH)4, and 25 μM 4,4’-Bipy, with or without 1 μM the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 for 2 h, followed by 12 h static incubation. C, D Each experiment was repeated independently for twice. B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine group was set as control. BP: B2(OH)4 and 4,4’-bipyridine. Original data are provided in Source Data file.

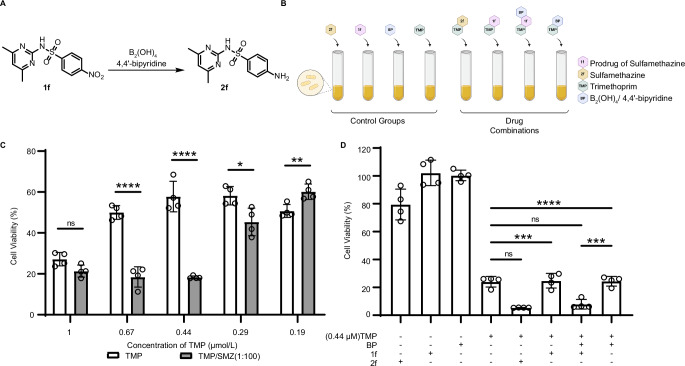

Synergy between antibacterial drugs has been utilized therapeutically ever since streptomycin and benzylpenicillin were the only antibiotics available. The combination of trimethoprim (TMP) and sulfonamide has been historically used to treat bacterial infections69. We speculated our nitro-reduction protocol could also be utilized for selective killing of pathogenic bacteria. To prove our hypothesis, we first optimized the TMP and Sulfamethazine (SMZ) concentration for a maximum bacterial growth inhibition effect. We found that the combination of 0.44 μM TMP and 44 μM SMZ, or 0.67 μM TMP and 67 μM SMZ showed the highest synergistic effect (Fig. 5C). Next, we treated Escherichia coli with either 0.44 μM TMP, combinations of 0.44 μM TMP and 44 μM prodrug 1 f, combinations of 0.44 μM TMP and 44 μM Sulfamethazine 2 f, or combinations of 0.44 μM TMP, 44 μM prodrug 1 f and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine (Fig. 5B). Only the addition of Sulfamethazine 2 f (Fig. 5D, column 5) or activated 1 f (column 7) showed synergistic effect against E. coli. As a control, 1 f or 2 f as a single agent, or the combination of TMP and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine did not affect the growth of the bacteria (Fig. 5D, columns 1,2 and 8). These experiments demonstrated a complementary prodrug strategy enabled by the 4,4’-bipyridine-mediated nitro-reduction for anti-microbial therapeutics. The combination of 0.67 μM TMP and 67 μM 1 f or 2 f also results in synergistic killing effect. However, at these concentrations, we observed cytotoxicity of B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine (Supplementary Fig. 19, columns 4 and 8).

Fig. 5. The anti-bacterial effect was demonstrated by 1 f nitroaromatic reduction.

A Schematic illustration for the reduction of 1 f. B Schematic illustration of the combination anti-bacterial therapy. (B Created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en). C The cell viability of the combination of TMP and SMZ (TMP: SMZ 1:100), the concentration of TMP was diluted to 1 μM, 0.67 μM, 0.44 μM, 0.29 μM, 0.19 μM,and SMZ was diluted to 100 μM, 67 μM, 44 μM, 29 μM, 19 μM accordingly. E coli. was treated with TMP and SMZ for 24 h. Cell viability of E coli. was measured by OD600 and calculated as indicated in supporting information. D Cell viability of E coli. as measured 24 h after compound treatment by OD600 (TMP: 0.44 μM, SMZ(2 f): 44 μM, 1 f: 44 μM, B2(OH)4: 893 μM, 4,4’-bipyridine: 223 μM). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 samples). P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns: no significance. Exact P values are provided in Source Data file.

Indole is a versatile pharmacophore with a wide range of pharmacological activities via different mechanisms of action70. We envisioned that ortho-acetaldehyde substituted nitroarene might undergo annulation after nitro reduction to form an indole ring (Fig. 6A). This cascade reaction would provide an example of indole synthesis in living cells71. To test this idea, ortho-nitro phenylacetaldehyde (5) was synthesized and subjected to the optimized nitro-reduction conditions. Satisfyingly, the desired indole product was obtained in 91% yield. To illustrate the compatibility of this cascade reaction with living cells, we synthesized an o-nitro phenylacetaldehyde derivative 7. Prodrug 7 underwent cascade cyclization upon addition of B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine in DMSO: PBS (1: 9) at 37 °C. The conversion of 7 to the indole derivative 8, a potent antimitotic agent72, was confirmed by HPLC (Supplementary Fig. 34). We treated Jurkat cells with 100 nM or 1 μM of prodrug 7, active compound 8, or prodrug 7 and B2(OH)4/4,4’-pyridine for 24 h and measured the cell viability by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. While prodrug 7 or B2(OH)4/4,4’-pyridine alone showed minimal cytotoxicity, activation of 7 by B2(OH)4/4,4’-pyridine significantly increased the cell-killing effect of the compound, indicating that 7 was converted to 8 in Jurkat cells in the presence of the diboron reagent. These experiments demonstrated that the nitro-reduction-annulation cascade can be applied as a complementary strategy for indole synthesis in living cells.

Fig. 6. Indole synthesis in living cells by aromatic nitro reduction-annulation cascade.

A Schematic illustration for the indole synthesis. B Schematic illustration for activation of prodrug 7. C The Jurkat cells were shaken with 7 (100 nM or 1 μM) and BP (30 eq. B2(OH)4, 5 eq. 4,4’-Bipy) for 2 h, followed by 24 h static incubation. 8 (100 nM or 1 μM) was set as a positive control, the BP group was added separately to eliminate toxic interference. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 samples). P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001, ns: no significance. Exact P values are provided in Source Data file.

To demonstrate the efficacy of our approach in vivo. We constructed a 4T1 cell line stably expressing super degron (SD) fused firefly luciferase (FLuc). The SD system is a 61 amino acids chimeric sequence of ZFN91 and IKZF3 that render any fused protein susceptible to degradation upon IMiDs treatment73. We envisioned that compound 3, a prodrug of Iberdomide (Pro-Iber) can be activated under the nitro reduction condition to give Iberdomide (Iber), which can then degrade the SD fused firefly luciferase by recruiting E3 ligase CRBN. We first tested this degradation system in vitro. 4T1 cells expressing FLuc-SD were treated with Pro-Iber and B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine. Cells treated with Pro-Iber alone, B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine alone, Iber, or DMSO were used as controls. After 14 h, the cells were analysed by a micro-plate reader. We observed decrease of luminescence signal for Pro-Iber+ B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine and Iber groups, indicating that such strategy can successfully activate Pro-Iber and degrade FLuc-SD (Fig. 7A). The luminescence signal was not changed for Pro-Iber alone, B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine alone, or DMSO groups, demonstrating that the degradation effect was not caused by the catalyst or the prodrug. To demonstrate the prodrug activation strategy in vivo, Balb/c mice were subcutaneously injected with 4T1 cells stably expressing FLuc-SD on both sides of the flanks on day 0. Pro-Iber was intravenously injected on day 7. Intratumor injection of B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine was performed 1h and 2 h after the pro-Iber treatment. The entire drug delivery process was repeated on day 8. Bioluminescence imaging was performed just before the first treatment and 12 h after the second treatment (Fig. 7B). Satisfyingly, we observed a decrease of the bioluminescence signal for the drug treatment group (Fig. 7C, D). The decrease of the bioluminescence signal was also observed for mice subjected to intravenous injection of the active drug Iberdomide on days 7 and 8. In contrast, we saw increase of the bioluminescence signal for mice treated with Pro-Iber, PBS or B2(OH)4/4,4’-bipyridine alone. No mouse death was observed during the treatment. This experiment illustrated that our prodrug activation strategy by nitro reduction is biocompatible in vivo and holds the promise for targeted drug delivery.

Fig. 7. In vivo protein degradation of Fluc-SD induced by Prodrug activation of Pro-Iberdomide.

A Reduction of Fluorescence Signal in 4T1-Fluc-SD Cells Induced by prodrug activation. The 4T1-Fluc-SD Cells were shaken with Pro-Iber (2.5 μM) and BP (30 eq. B2(OH)4, 5 eq. 4,4’-Bipy) for 2 h, followed by 12 h incubation. Iberdomide (2.5 μM), Pro-Iber and BP groups were set as controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 samples). P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ****P < 0.0001. B Balb/c mice were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106 4T1-Fluc-SD cells on the flanks on day 0. For the drug treatment group, on day 7, tumor-bearing mice were i.v. injected with 5 mg/kg Pro-Iberdomide at 0 h, BP (20 mg/kg B2(OH)4, 5.9 mg/kg 4,4’-Bipy) were intratumorally injected twice after 1 h and 2 h at both side of the tumors. The treatment process was repeated at 24, 25 and 26 h. At 38-h time point, bioluminescence imaging was performed. Pro-Iberdomide (5 mg/kg), Iberdomide (5 mg/kg), Vehicle (A PBS solution containing 2% DMSO) and BP (20 mg/kg B2(OH)4, 5.9 mg/kg 4,4’-Bipy) were used as control groups. Intravenous injections of Pro-Iberdomide (5 mg/kg), Iberdomide (5 mg/kg), and Vehicle (A PBS solution containing 2% DMSO) were performed at 2 h and 26 h. BP (20 mg/kg B2(OH)4, 5.9 mg/kg 4,4’-Bipy) were intratumorally injected for four times at 1 h, 2 h, 25 h and 26 h. (B Created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en). C The bioluminescence imaging results of the tumor-bearing mice. D Quantification of BLI signals from (C). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 samples). P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P values are provided in Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we herein report a biocompatible 4,4’-bipyridine-mediated aromatic nitro reduction reaction for controlled prodrug activation. The reaction illustrates excellent substrate compatibility and proceeds at low micromolar concentration in biocompatible conditions. Mechanistic study indicated the key of water in this reaction. Using a fluorescence “turn-on” substrate, we demonstrated the compatibility of our reaction with living cells. We then synthesized the prodrug of iberdomide and performed the nitro-reduction reaction in MM.1S cells to illustrate the application of our reaction in on-demand protein degradation. In addition, we showed that our prodrug activation strategy can be applied for anti-microbial therapeutics. Furthermore, we designed a nitro-reduction-annulation cascade for the synthesis of indole motifs in living cells and applied this cascade reaction for the synthesis of bioactive indole derivatives to induce cancer cell death. Finally, we conducted an in vivo protein degradation experiment to demonstrate the ability of this bioorthogonal chemistry to activate prodrugs in animal models. We envisioned that our 4,4’-bipyridine-mediated nitro reduction reaction would be a valuable tool in chemical biology and drug delivery.

Methods

Chemical synthesis

Synthesis protocol and additional characterization can be found in the Supplementary Information.

General procedure for the aromatic nitro reduction

To a solution of PBS (1800 μL) and DMSO (63.3 μL) in 3 mL glass sample bottles was added a solution of nitro compound 1a ~ 1k (500 μM, 20 μL, 1 eq.), tetrahydroxydiborane (10 mmol, 66.7 μL, 20 eq.), 4,4′-bipyridine (2.5 mmol, 50 μL, 5 eq.) in DMSO. The resulting mixture was stirred at 37 °C for 30 min. After the reaction completion, the yields of product is measured by analytical HPLC or 1H-NMR.

Analysis of yields and reaction kinetic by microplate reader

To a solution of 1c (100 μM, 200 μM or 500 μM) in PBS was added tetrahydroxydiborane (20 eq.), 4,4′-bipyridine (5 eq.). The resulting mixture was stirred at 37 °C for 30 min. The yields of 1c were calculated by the emission intensity λ450 nm which was excited at 350 nm.

Pseudo first-order rate constant were calculated by the equation below:

Where [A] is concentration of A at time t, [A0] is initial concentration of A and k is pseudo first-order reaction rate constant, t is time.

High-resolution MS analysis of 1c reduction

To a solution of diluted 1c (500 μM) in d6-DMSO/D2O (1:9, 1 mL) was added B2(OH)4 (10 mM, 20 eq.) and 4,4’-bipyridine (2.5 mM, 5 eq.) in 3 mL glass sample bottles containing a PTFE-coated magnetic stir bar. Reaction in DMSO/H2O (1:9) was used as a control. The reaction mixture was stirred at 37°C for 30 min. After the reaction, the crude solution was analysed by HRMS after filtration.

Cell culture

THP-1(Cat# TIB202), MM.1S(Cat# CRL-2974), Jurkat, Clone E6-1(Cat# TIB152), 293 T (Cat# CRL-3216), 4T1(Cat# CRL-2539) and HeLa(Cat# CRM-CCL-2) cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC). THP-1, MM.1S and Jurkat were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, 1x penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 humidity incubator at 37 °C, and MM.1S was supplemented with 1x Glutamax and 1x Sodium pyruvate. 293 T, 4T1 and HeLa were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1x penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 humidity incubator at 37°C. E.Coli (DH5α) was inoculated in LB broth with 37 °C at 170 rpm.

Antibodies

Anti-IKZF1 antibodies (D6N9Y) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (14859 s, Lot 1). Anti-IKZF3 antibodies (EPR9342) were purchased from Abcam (ab139408). Anti-GAPDH antibodies (60004-1-lg) were purchased from Proteintech. HRP goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (32430), and HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (31466) were purchased from Huaxingbio. Primary antibodies were applied as a 1:1000, secondary antibodies were applied as a 1:10000.

Fluorescence imaging assay of 1d reduction

THP-1 cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were treated with 50 μM 1d with or without 30 eq. B2(OH)4/5 eq. 4,4-bipyridine, 10 or 20 μM 2d. Cells were shaken at 170 rpm for 2 h. Then cells were collected and washed with PBS, pH 7.4 for 3 times, then suspended in 1 mL PBS buffer. For imaging, the cells were seeded into 20 mm confocal dishes. Fluorescent signal was excited by 560 nm laser and collected at 620 ± 50 nm by using Olympus FV1200. FIJI was used to extract line-intensity profiles for each image for quantitative comparison of signal intensity.

Flow cytometry assay of 1d reduction

THP-1 cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were treated with increasing concentrations of 2d (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 μM), or 1d at the same concentration as negative control to eliminate the interference of background intensities. Cells were shaken in 37 °C for 2 h, and washed 3 times with PBS. Data were collected at 560 nm excitation by flow cytometry. Considering that the background intensities of 1d are much lower than 2d at any given concentration, to simplify the calculation, we set the background fluorescence of 1d as a constant number (the average of 1d fluorescence intensity at concentrations from 5 μM to 50 μM). A standard curve was plotted using the fluorescence intensity of 2d plus this constant number as the y axis, and the concentration of 2d as the x axis. For the experimental group, THP-1 cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were shaken with 50 μM 1d, 30 eq. B2(OH)4 or B2Pin2, 5 eq. 4,4’-bipyridine at 37 °C for 2 h. Then the cells were collected, washed with PBS for 3 times, and the fluorescence intensities of the cells were analysed by flow cytometry using 560 nm excitation. The yields of the nitro reduction reaction were calculated according to the standard curve.

The cell extraction protocol for quantitative MS analysis

THP-1 cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL, then cells were shaken with 50 μM 1d, with or without 250 μM (5 eq.) 4,4’-bipyridine, and 1.50 mM (30 eq.) B2(OH)4 for 2 h. Cell lysates containing reactant were extracted as follows: Centrifuged the cells at 1000 g for 5 min, aspirate the medium completely, suspend cells with PBS buffer, transfer to the 1.5 mL tube and wash using PBS buffer 3 times gently. Put the tubes on dry ice and add 1 mL of 80% (V/V) methanol (pre-chilled to −80 °C) and incubate the plates at −80 °C for 2 h. Then, centrifuge the tube at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and transfer 500 μL metabolite-containing supernatant to a new 1.5 ml tube on dry ice. Finally, Speedvac was used to dry the supernatant at room temperature. Store the dried samples in −80 °C freezer or perform quantitative MS analysis. The quantitative MS analysis was performed on the UPLC system that was coupled to a Q-Exactive HFX orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, CA) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) probe. Extracts were separated by a BEH C18 100 × 2.1 mm 1.7 μm column (Waters, USA). A binary solvent system was used, in which mobile phase A consisted of 100% H2O (0.1% FA), and mobile phase B of 100% ACN (0.1% FA). A 12-min gradient with flow rate of 300 μL/min was used. Column chamber and sample tray were held at 45 °C and 10 °C, respectively. Data with mass ranges of m/z 70-1050 was acquired at positive ion mode with data dependent MSMS acquisition. The full scan and fragment spectra were collected with resolution of 60,000 and 15,000 respectively. The source parameters are as follows: spray voltage: 2800 v; capillary temperature: 320 °C; heater temperature: 300 °C; sheath gas flow rate: 35 Arb; auxiliary gas flow rate: 10 Arb. Data analysis were performed by the software Xcalibur (Thermo Fisher, CA). Mass tolerance of 10 ppm was applied for precursor search. Flowcytometry was performed on LSRFortessa cell analyzer (BD biosciences, USA) equipped with BD FACSDiva software.

IKZF1/3 degradation in MM.1S cells

MM.1S cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were treated with varying concentrations of 3, B2(OH)4 (30 eq.)/4,4’-bipyridine (5 eq.), and/or MLN4924, as indicated in Figs. 4C or 4D. Cells were shaken at 170 rpm for 2 h and were transferred to 6-well plate for another 12 h. Cells were washed by PBS twice before lysis for Immunoblot assay.

Immunoblot assay

MM.1S cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. The lysates were then resolved by 4–20% Mini Protein Gel (Bio-Rad) at 90 V for 120 min. Then the proteins were transferred from the gel to PVDF membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010) at 300 mA for 60 min. The membrane was incubated with 5% nonfat milk for 60 min, followed by primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. On the next day, the membranes were washed 3 times with TBST, incubated secondary antibody for 60 min at room temperature and then washed 3 times with TBST. The membranes were detected under the Tanon 4600 Gel Image System after brief incubation with ECL substrate (Tanon, 180-5001).

Cell viability assays

Cellular toxicity of 1d reduction in 293 T, HeLa, and THP-1 cells

293 T, HeLa, and THP-1 cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were treated with 50 μM 1d, 30 eq. B2(OH)4 and 5 eq. 4,4-bipyridine. Cells were shaken at 170 rpm for 2 h and seeded into 96-well black plate at 100 μL /well. Cell Viability Assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the chemicals (Cell Counting-Lite 2.0, Vayzme, DD1101-02) following product instructions. The signals were monitored by TECAN-Spark microplate reader.

Cell viability were caculated by the equation below:

Where I stands for the luminescence of the cells treated with chemicals, I0 is the luminescence of blank group cells without any chemicals.

Cell toxicity of 3 reduction in HeLa, 293 T, THP-1 and MM.1S cells

HeLa, 293 T, THP-1 and MM.1S cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, then cells were treated with 25 μM (5 eq.) 4,4’-bipyridine, and 150 μM (30 eq.) B2(OH)4 for 2 h shaking. After that, there would be 12 h static incubation. Then cells were seeded into 96-well black plate at 100 μL /well. Cell Viability Assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the chemicals (Cell Counting-Lite 2.0, Vayzme, DD1101-02) following product instructions. The signals were monitored by TECAN-Spark microplate reader.

Cell viability of 7 reduction in Jurkat cells

Jurkat cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, and were treated with 7 only, 7 + BP, BP only and 8 only at 100 nM or 1 μM, where BP only group served as negative control and 8 only group served as positive control. Cells were shaken at 170 rpm for 2 h and were seeded into 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well for antoher 24 h. CCK-8 Cell Counting Kit was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of each condition. 10 μL CCK-8 solution was added into each well and cells were incubated for further 2 h. The absorption of each well at 450 nm was recorded via TECAN-Spark microplate reader.

Anti-bacterial assay

The E. coli were inoculated in LB broth and cultured at 37 °C at 170 rpm until log phase. Afterwards, E. coli was inoculated into tubes with a density of 5 × 106 CFU/ml per tube, followed by additional gradient concentration of test chemicals prepared in LB broth. Tubes were then shaken at 37 °C for 2 h, then cells were seeded into 96-well plate well at 100 μl/well, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. OD600 value of each well was measured by Tecan-Spark. The cell viability on the bacteria was calculated according to Equation below:

where is the average OD value of E. coli without chemicals, and is the OD value of E. coli exposed to the test chemicals.

Generation of the 4T1-Fluc-SD cell line

The Super-Degron (SD) and Fluc sequences were gene synthesized and subsequently cloned into pDest9 vector. For lentiviral packaging, pDest9-Fluc-SD plasmid was co-transfected with pMD2.G (Addgene 12259) and psPAX2 (Addgene 12260) into 293 T cells according to the standard protocol. Media collected from transfected 293 T cells was used to infect 4T1 cells for 2 days, then the 4T1 cells were selected with 2.5 μg/mL puromycin for 3 days. 4T1-Fluc-SD cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1× penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 humidity incubator at 37 °C.

SD fused firefly luciferase degradation in vitro

4T1-Fluc-SD cells were cultured in tubes (2 mL per tube) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, then cells were treated with 2.5 μM Pro-Iberdomide, 12.5 μM (5 eq.) 4,4’-bipyridine, and 75 μM (30 eq.) B2(OH)4 for 2 h’ shaking. 2.5 μM Pro-Iberdomide only, 2.5 μM Iberdomide only or BP only was set as controls. After that, there would be 12 h static incubation. Then cells were seeded into 96-well white plate at 100 μL /well. Bright-LiteTM Luciferase Assay System (Vayzme, DD1204-03) was used to evaluate the fluorescence signal intensity following product instructions. Cell Viability Assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the chemicals (Cell Counting-Lite 2.0, Vayzme, DD1101-02) following product instructions. The signals were monitored by TECAN-Spark microplate reader.

Animal

Female Balb/c mice of age 6–8 weeks were purchased from Beijing Vital River (Beijing, China). This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. All work performed on animals was in accordance with and approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at Tsinghua University. Animals were housed in 12 light/12 dark cycle, 65–75 °F (~18–23 °C), and 40–60% humidity condition. Animals were euthanized when the tumor reached 15 mm in any dimension or when they became moribund with severe weight loss or unhealing ulceration. This limit was not exceeded at any point.

In vivo protein degradation assay

Tumor-bearing mice were established by subcutaneously injecting a suspension of 2 × 106 4T1-Fluc-SD cells per mouse into both sides of flanks (1 × 106 for each side) on day 0. When tumor volume reached 80–100 mm3, the animals were randomly divided into five groups (n = 3). The mice were administered different compounds suspended in PBS containing 2% DMSO. Pro-Iber (5 mg/kg) was injected via the tail vein on day 7 (0 h). Intratumor injection of B2(OH)4 (20 mg/kg, 30 eq.)/4,4’-bipyridine (5.9 mg/kg, 5 eq.) was performed 1 and 2 h after the pro-Iber treatment. The treatment process was repeated at 24, 25 and 26 h. Bioluminescence imaging was performed just before the first treatment and 12 h after the second treatment.

For comparison, the remaining four control groups received tail intravenous injections of Pro-Iber (5 mg/kg), Iber (5 mg/kg) or PBS at 2 h and 26 h (Starting of day 7 as 0 h), BP (20 mg/kg B2(OH)4, 5.9 mg/kg 4,4’-bipyridine) were intratumorally injected for four times at 1 h, 2 h, 25 h and 26 h.

At 38-h time point, mice were given luciferin (150 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection, anesthetized with isoflurane, and bioluminescence imaging was performed on an In vivo Imaging System IVIS Lumina series III (Revvity, USA). Bioluminescence images were obtained and analyzed using Living Image software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this work was provided by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFA0910900, L.C.), “Thousand Youth Talents Plan” (L.C.), Beijing Frontier Research Center for Biological Structure (L.C.), startup funding and “Dushi Plan” from Tsinghua University (L.C.), Center for Life Sciences postdoctoral fellowship (Y.S., W.W.). We would like to thank Jia He and Dr. Rui Kuai (Tsinghua University) for their help with the animal experiments. We thank the staff members at Metabolomics and Lipidomics Center at Tsinghua - National Protein Science Facility (Beijing) for providing facility support.

Author contributions

Y.S., Q.W. and L.C. designed the experiments. Y.S. performed the chemical synthesis, with the help from Q.W. and S.Y. Q.W. performed the cellular experiments and mouse experiments. Y.Z. generated the 4T1 cell line stably expressing Fluc-SD. W.W. generated the HeLa cell line stably expressing Flag-Halo-NES. L.C. wrote the manuscript with feedbacks from all other authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main manuscript and Supplementary Information. Source Data for the figures in the main text and in the Supplementary Information are provided in the Source Data file. Data are also available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qing Wang, Yikang Song.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52604-y.

References

- 1.Kolb, H. C. & Sharpless, K. B. The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today8, 1128–37 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sletten, E. M. & Bertozzi, C. R. Bioorthogonal chemistry: fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.48, 6974–98 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim, R. K. & Lin, Q. Bioorthogonal chemistry: recent progress and future directions. Chem. Commun. (Camb.)46, 1589–600 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKay, C. S. & Finn, M. G. Click chemistry in complex mixtures: bioorthogonal bioconjugation. Chem. Biol.21, 1075–101 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson, D. M., Nazarova, L. A. & Prescher, J. A. Finding the right (bioorthogonal) chemistry. ACS Chem. Biol.9, 592–605 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devaraj, N. K. The future of bioorthogonal chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci.4, 952–959 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scinto, S. L. et al., Bioorthogonal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers1, 30 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wu, K. et al. Click activated protodrugs against cancer increase the therapeutic potential of chemotherapy through local capture and activation. Chem. Sci.12, 1259–1271 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McFarland, J. M. et al. Click chemistry selectively activates an auristatin protodrug with either intratumoral or systemic tumor-targeting agents. ACS Cent. Sci.9, 1400–1408 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, J. & Chen, P. R. Development and application of bond cleavage reactions in bioorthogonal chemistry. Nat. Chem. Biol.12, 129–37 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji, X. et al. Click and release: bioorthogonal approaches to “on-demand” activation of prodrugs. Chem. Soc. Rev.48, 1077–1094 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, J., Wang, X., Fan, X. & Chen, P. R. Unleashing the power of bond cleavage chemistry in living systems. ACS Cent. Sci.7, 929–943 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, J. et al. Palladium-triggered deprotection chemistry for protein activation in living cells. Nat. Chem.6, 352–61 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss, J. T. et al. Extracellular palladium-catalysed dealkylation of 5-fluoro-1-propargyl-uracil as a bioorthogonally activated prodrug approach. Nat. Commun.5, 3277 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller, M. A. et al. Nano-palladium is a cellular catalyst for in vivo chemistry. Nat. Commun.8, 15906 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Lopez, A. M. et al. Gold-triggered uncaging chemistry in living systems. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.56, 12548–12552 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann, K., Gambardella, A., Lilienkampf, A. & Bradley, M. Tetrazine-mediated bioorthogonal prodrug-prodrug activation. Chem. Sci.9, 7198–7203 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu, J., Xu, M., Parvez, S., Peterson, R. T. & Franzini, R. M. Bioorthogonal removal of 3-isocyanopropyl groups enables the controlled release of fluorophores and drugs in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 8410–8414 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao, Q. et al. Synergistic enzymatic and bioorthogonal reactions for selective prodrug activation in living systems. Nat. Commun.9, 5032 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sancho-Albero, M. et al. Cancer-derived exosomes loaded with ultrathin palladium nanosheets for targeted bioorthogonal catalysis. Nat. Catal.2, 864–872 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Learte-Aymami, S., Vidal, C., Gutierrez-Gonzalez, A. & Mascarenas, J. L. Intracellular reactions promoted by bis(histidine) miniproteins stapled using palladium(II) complexes. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.59, 9149–9154 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira, B. L. et al. Platinum-triggered bond-cleavage of pentynoyl amide and N-propargyl handles for drug-activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 10869–10880 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang, T. C., Vong, K., Yamamoto, T. & Tanaka, K. Prodrug activation by gold artificial metalloenzyme-catalyzed synthesis of phenanthridinium derivatives via hydroamination. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.60, 12446–12454 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maslah, H. et al. In-cell generation of anticancer phenanthridine through bioorthogonal cyclization in antitumor prodrug development. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.60, 24043–24047 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, C. et al. A cationic micelle as in vivo catalyst for tumor-localized cleavage chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.60, 19750–19758 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding, Z. et al. Radiotherapy reduces N-oxides for prodrug activation in tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 9458–9464 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunsmore, L. et al. Controlled masking and targeted release of redox-cycling ortho-quinones via a C-C bond-cleaving 1,6-elimination. Nat. Chem.14, 754–765 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong, Q. et al. A carbon-carbon bond cleavage-based prodrug activation strategy applied to beta-lapachone for cancer-specific targeting. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.61, e202210001 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang, D., Lee, S. & Kim, J. Bioorthogonal click and release: a general, rapid, chemically revertible bioconjugation strategy employing enamine N-oxides. Chem8, 2260–2277 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, L., Zhang, D., Johnson, M. & Devaraj, N. K. Light-activated tetrazines enable precision live-cell bioorthogonal chemistry. Nat. Chem.14, 1078–1085 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng, Y. et al. A membrane-embedded macromolecular catalyst with substrate selectivity in live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 1262–1272 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng, C., Shen, L. & Ang, W. H. Harnessing endogenous formate for antibacterial prodrug activation by in cellulo ruthenium-mediated transfer hydrogenation reaction. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.59, 9314–9318 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singleton, D. C., Macann, A. & Wilson, W. R. Therapeutic targeting of the hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.18, 751–772 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen, Z., Han, F., Du, Y., Shi, H. & Zhou, W. Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.8, 70 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter, F. W., Wouters, B. G. & Wilson, W. R. Hypoxia-activated prodrugs: paths forward in the era of personalised medicine. Br. J. Cancer114, 1071–7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiegelberg, L. et al. Hypoxia-activated prodrugs and (lack of) clinical progress: The need for hypoxia-based biomarker patient selection in phase III clinical trials. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol.15, 62–69 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knox, R. J., Friedlos, F., Jarman, M. & Roberts, J. J. A new cytotoxic, DNA interstrand crosslinking agent, 5-(aziridin-1-yl)-4-hydroxylamino-2-nitrobenzamide, is formed from 5-(aziridin-1-yl)-2,4-dinitrobenzamide (CB 1954) by a nitroreductase enzyme in Walker carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharm.37, 4661–9 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams, E. M. et al. Nitroreductase gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy: insights and advances toward clinical utility. Biochem J.471, 131–53 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung-Faye, G. et al. Virus-directed, enzyme prodrug therapy with nitroimidazole reductase: a phase I and pharmacokinetic study of its prodrug, CB1954. Clin. Cancer Res7, 2662–8 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel, P., et al. A phase I/II clinical trial in localized prostate cancer of an adenovirus expressing nitroreductase with CB1954 [correction of CB1984. Mol. Ther. 17, 1292–9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Yu, C., Liu, B. & Hu, L. Samarium(0) and 1,1’-dioctyl-4,4’-bipyridinium dibromide: a novel electron-transfer system for the chemoselective reduction of aromatic nitro groups. J. Org. Chem.66, 919–24 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corma, A. & Serna, P. Chemoselective hydrogenation of nitro compounds with supported gold catalysts. Science313, 332–4 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wienhofer, G. et al. General and selective iron-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of nitroarenes without base. J. Am. Chem. Soc.133, 12875–9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsudome, T. et al. Design of a silver-cerium dioxide core-shell nanocomposite catalyst for chemoselective reduction reactions. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.51, 136–9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westerhaus, F. A. et al. Heterogenized cobalt oxide catalysts for nitroarene reduction by pyrolysis of molecularly defined complexes. Nat. Chem.5, 537–43 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei, H. et al. FeOx-supported platinum single-atom and pseudo-single-atom catalysts for chemoselective hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarenes. Nat. Commun.5, 5634 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jagadeesh, R. V. et al. Hydrogenation using iron oxide-based nanocatalysts for the synthesis of amines. Nat. Protoc.10, 548–57 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furukawa, S., Takahashi, K. & Komatsu, T. Well-structured bimetallic surface capable of molecular recognition for chemoselective nitroarene hydrogenation. Chem. Sci.7, 4476–4484 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, S. et al. High catalytic activity and chemoselectivity of sub-nanometric pd clusters on porous nanorods of CeO2 for hydrogenation of nitroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 2629–37 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weng, C., Yang, H., Loh, B. S., Wong, M. W. & Ang, W. H. Targeting pathogenic formate-dependent bacteria with a bioinspired metallo-nitroreductase complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 6453–6461 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du, H.-C. et al. A Mild, DNA-compatible nitro reduction using B2(OH)4. Org. Lett.21, 2194–2199 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jang, M., Lim, T., Park, B. Y. & Han, M. S. Metal-free, rapid, and highly chemoselective reduction of aromatic nitro compounds at room temperature. J. Org. Chem.87, 910–919 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu, H. et al. Metal-free reduction of aromatic nitro compounds to aromatic amines with B2pin2 in isopropanol. Org. Lett.18, 2774–6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uozumi, Y. et al. Metal-free reduction of nitro aromatics to amines with B2(OH)4/H2O. Synlett29, 1765–1768 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ovung, A. & Bhattacharyya, J. Sulfonamide drugs: structure, antibacterial property, toxicity, and biophysical interactions. Biophys. Rev.13, 259–272 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoon, C. H., Owusu-Guha, J., Smith, A. & Buschur, P. Amifampridine for the management of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: a new take on an old drug. Ann. Pharmacother.54, 56–63 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paridaens, K., Fullarton, J. R. & Travis, S. P. L. Efficacy and safety of oral Pentasa (prolonged-release mesalazine) in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Med Res Opin.37, 1891–1900 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khair-Ul-Bariyah, S. et al. Benzocaine: review on a drug with unfold potential. Mini Rev. Med Chem.20, 3–11 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ellenbogen, K. A., Wood, M. A. & Stambler, B. S. Procainamide: a perspective on its value and danger. Heart Dis. Stroke2, 473–6 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kronke, J. et al. Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science343, 301–5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu, G. et al. The myeloma drug lenalidomide promotes the cereblon-dependent destruction of Ikaros proteins. Science343, 305–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hosoya, H. et al. 4,4’-bipyridyl-catalyzed reduction of nitroarenes by Bis(neopentylglycolato)diboron. Org. Lett.21, 9812–9817 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qi, J.-Q. & Jiao, L. DFT study on the mechanism of 4,4′-bipyridine-catalyzed nitrobenzene reduction by diboron(4) compounds. J. Org. Chem.85, 13877–13885 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niu, H. et al. Photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) based fluorescent probes for cellular imaging and disease therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev.52, 2322–2357 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lukinavičius, G. et al. A near-infrared fluorophore for live-cell super-resolution microscopy of cellular proteins. Nat. Chem.5, 132–139 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matyskiela, M. E. et al. A cereblon modulator (CC-220) with improved degradation of ikaros and aiolos. J. Med Chem.61, 535–542 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holstein, S. A. & McCarthy, P. L. Immunomodulatory drugs in multiple myeloma: mechanisms of action and clinical experience. Drugs77, 505–520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.An, K. et al. Stimuli-responsive PROTACs for controlled protein degradation. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl.62, e202306824 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masters, P. A., O’Bryan, T. A., Zurlo, J., Miller, D. Q. & Joshi, N. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole revisited. Arch. Intern Med163, 402–10 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumari, A. & Singh, R. K. Medicinal chemistry of indole derivatives: Current to future therapeutic prospectives. Bioorg. Chem.89, 103021 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.D’Avino, C., Gutierrez, S., Feldhaus, M. J., Tomas-Gamasa, M. & Mascarenas, J. L. Intracellular synthesis of indoles enabled by visible-light photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 2895–2900 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shetty, R. S. et al. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of N-(3-(1H-indol-4-yl)-5-(2-methoxyisonicotinoyl)phenyl)methanesulfonamide (LP-261), a potent antimitotic agent. J. Med Chem.54, 179–200 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jan, M. et al. Reversible ON- and OFF-switch chimeric antigen receptors controlled by lenalidomide. Sci. Transl. Med.13, eabb6295 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main manuscript and Supplementary Information. Source Data for the figures in the main text and in the Supplementary Information are provided in the Source Data file. Data are also available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.