Abstract

Skull base chordomas are a rare entity that requires multidisciplinary decision-making for management. We report a case wherein the patient was initially mismanaged at a peripheral centre, and was then redeemed by a multidisciplinary tumor board decision-making and specialized surgical procedures. We also present a brief review of the therapeutic options.

Keywords: Skull base chordoma, Maxillary swing, Anterior skull base

Introduction

The anatomic junction of the facial viscerocranium, with the neural viscerocranium is known as the skull base. This area is anatomically complex and critically important, as it not only supports the intracranial contents but also is a corridor for the entry and exit of vital neurovascular structures to the brain. Pathologically, the skull base is an area of interest to neurosurgeons, head and neck surgeons, and pathologists alike, owing to the diverse, but rare neoplasms and infections that may arise here. With advances in the understanding of pathological processes and improved diagnostic tools, the list of neoplasms continues to grow with every new update of our classification systems. The 5th edition of the WHO classification of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinus, and skull base tumors is depicted in Table 1 below [1].

Table 1.

2022 5th edition of WHO classification of tumors of nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base

| Diagnostic Group | Category | Diagnostic Entity Section |

|---|---|---|

| Hamartomas |

Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma Seromucinous hamartoma Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma |

|

| Respiratory epithelial lesions | ||

| Sinonasal Papilloma |

Sinonasal papilloma, inverted type Sinonasal papilloma, oncocytic type Sinonasal papilloma, exophytic type |

|

| Carcinoma |

Keratinising squamous cell carcinoma Non-Keratinising squamous cell carcinoma NUT carcinoma SWI/SNF complex deficient sinonasal carcinoma Sinonasal lymphoepithelial carcinoma Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma Teratocarcinosarcoma HPV related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma |

|

| Adenocarcinoma |

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma Non Intestinal type adenocarcinoma |

|

| Mesenchymal tumors of sinonasal tract |

Sinonasal tract angiofibroma Sinonasal tract glomangiopericytoma Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma Chordoma |

|

| Other tumors |

Sinonasal ameloblastoma Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma Meningioma of sinonasal tract Olfactory neuroblastoma |

As mentioned, skull base tumors have a very diverse histology and proximity to vital neurovascular structures [2]. Coupled with the rarity of these tumors, this group of neoplasms may pose a challenge for surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists alike. Here we discuss a case report of a skull base neoplasm which though initially mismanaged outside, was eventually redeemed with a multidisciplinary discussion, surgical adequacy, and interdepartmental coordination.

Case Report

We present a case of a 20 years old lady from Assam, who presented to our clinic with the history of left nasal bleeding for a year; on and off oral bleeding for a year; and swelling around the left eye which she noticed for 2 months. The epistaxis was episodic, unprovoked, would usually quantify to a few drops and was aggravated with upper respiratory tract infections. She did not have any nasal blockade or hyposmia. Similar history was resonated in her oral bleeding, which would often present as saliva tinged with bleed. The swelling around the left eye was gradual, painless and was not associated with decreased vision or redness of eye. She did not elicit any history suggestive of cranial nerve dysfunction, or neck node swelling.

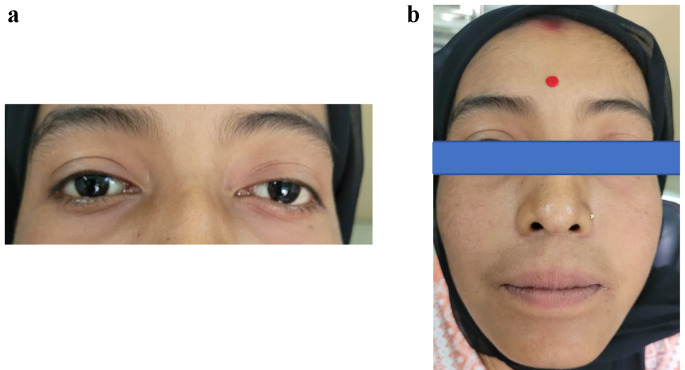

On examination, she had stable vitals, normal voice and smell function. She did not have any visual deficit. External nasal examination showed no abnormalities. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy revealed a grayish mass in the left nasal cavity with blood clots. There was no neck node swelling. She had left periorbital fullness, but no proptosis or chemosis. The clinical photographs have been depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph (a and b)

Nasal biopsy, done at a peripheral centre was suggestive of sino-nasal chordoma. She was started on neoadjuvant chemotherapy at that centre for an essentially non chemosensitive benign lesion, and she received 6 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin prior to her referral to our institute. The post chemotherapy scans showed progressive disease with the following findings. The CECT skull base showed a lobulated malignant soft tissue mass in the left infratemporal fossa with widening of Sphenopalatine foramen, pterygopalatine fossa with skull base erosion. It also depicted nasal and orbital extension. The superior extension was up to to anterior clivus and there was widening of left skull base foramina and petroclival fissure. There was intracranial extension to the epidural compartment. The left inferior orbital wall was eroded and there was extension to superior orbital fissure, inferior orbital fissure, abutting bony carotid canal and left Internal Carotid Artery.

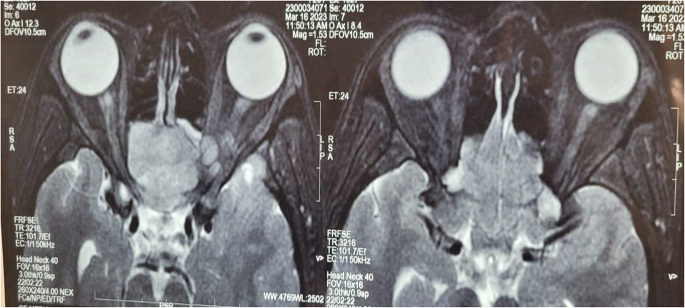

MRI of skull base showed a 46.9 × 52.8 × 46.5 cm lesion epicentred in the left ITF with positive Holman miller sign and compressing and remodeling inferior orbital wall. It was also shown to compresses the optic nerve. There was soft tissue present in orbital apex with no extension to anterior cranial fossa. The images have been shown in Fig. 1. The tumor was staged as cT1N0M0Gx.

The biopsy slide was reviewed and confirmed to be chordoma by the oncopathologists at our institute. The case was discussed in the skull base disease management group and the decision taken was upfront surgery. The surgical team decided to approach the tumor by maxillary swing. A neurosurgery back up was planned for the intracranial component. Pre-operative consent was taken informing about the facial incisions, loss of sensation in the infraorbital nerve distribution, possible loss of the maxilla bone, wound dehiscence and breakdown, visual disturbances, incomplete resection, oronasal and oronasopharyngeal fistulae and ectropion Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

T2 weighted MRI of the Skull Base showed an enhancing lobulated mass in the nasal cavity with compression of the optic nerve. There was also soft tissue extension into the orbital apex with pushing edges. No intradural extension was noted

Fig. 3.

MRI skull base shows the lesion epicentred in the left ITF with epidural extension, remodelling of the bony posterior wall of maxilla with nasal and orbital extension

Subsequently, the surgery was planned in four stages. The first stage was incision and soft tissue preparation. The second stage was osteotomies, maxillary swing and piecemeal resection of the tumor. Thirdly, miniplate preparation and reposition of the maxilla. Lastly, wound closure. These have been depicted in Figs. 4, 5 and 6.

Fig. 4.

Incision, skin flap and maxillary swing

Fig. 5.

Maxillary swing and reposition of maxilla

Fig. 6.

Closure of the incisions and osteotomy

Incision Planning

A Weber Ferguson incision was given. On the hard palate mucosa a incision was on the side of the swing. A mark was made from the junction of the hard and soft palate posteriorly to the premaxilla mucosa anteriorly where the incision turned towards the midline and to the gingiva between the lateral incisor and the canine. The mucosal incision and the bony incision were planned to be 0.5 cm apart to prevent overlapping of the incision and subsequent wound complications. The maxillary tuberosity and the bony spines of the pterygoid plates and pterygoid hamulus were identified immediately posterior to the tuberosity. The posterior end of the hard palate incision was continued laterally through the soft palate mucosa to the posterior surface of the ipsilateral maxillary tubercle Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Photograph of the patient at discharge

With a gentle pressure on the globe, along with the retraction of the cheek skin, the lower eyelid was put under tension and the skin incised with a number 15 blade. The skin is divided until the orbicularis oculi muscle is visible. The inferior orbital septum or anterior capsule of the inferior orbital fat pad was preserved. The lower eyelid skin was retracted with skin hooks, the skin and orbicularis muscle were elevated with sharp dissection as a unit. As the medial end of the lower eyelid incision curved inferiorly, the angular vein and artery were identified and ligated.

The soft tissues of the cheek were elevated off the upper maxilla in a subperiosteal plane to the level of the infra-orbital foramen, using a periosteal elevator. The infraorbital nerve and vessels were identified, ligated and divided.

Osteotomies and Maxillary Swing

The following osteotomies were planned and given:

The first osteotomy was marked at 90 degrees to the postero-inferior border of the zygoma. This osteotomy completed the division of the zygoma.

A second vertical osteotomy was marked in the midline of the anterior surface of the maxilla and extended between the lateral incisor and the canine. This osteotomy divided the maxilla just off the midline away from the septum, so that the septum remained intact articulating with the contralateral maxilla.

Superiorly the infraorbital horizontal osteotomy in a classical maxillary swing was not given. The upper osteotomy cut was at the frontonasal process. The orbital floor was included in the swing so as to access the retro-orbital area.

The last osteotomy was done to separate the maxillary tuberosity from the soft tissue attachments of the pterygoid plates, after deepening the intra oral incision.

The maxillary swing was performed to expose the tumor. The only attachment of the swung maxilla was to the cheek skin flap. The intranasal, as well as the intracranial, retro-orbital extensions were removed piecemeal and was sent for histopathology. Hemostasis was achieved.

Miniplates and Reposition of Maxilla

Miniplates were inserted at the osteotomy sites and maxilla was reposited back along with the cheek skin flap.

Wound Closure

Facial incision was closed with 4 − 0 Nylon. Palatal incision was closed with 3 − 0 vicryl.

Post operative period was uneventful. There was no CSF leak or meningitis or visual problems. Patient was on ryle’s tube feeds for 7 days. She was discharged on 7th post operative day. Repeat CECT scan showed no residual disease. Figure 8 shows the post operative images on follow up.

Fig. 8.

Follow up images of the patient at 2 months after surgery

Post op Histopathology showed sheets, cords and nests of atypical epitheloid cells with irregular hyperchromatic hyperchromatic nuclei, fine chromatn with eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm. There was no necrosis/mitosis. No sarcomatoid areas were seen. IHC results were as follows: CK negative, EMA: focal weak positive, S-100 diffuse strongly positive. IHC was consistent with chordoma. No adjuvant radiotherapy was planned for this patient in view of histology and radiological assessment.

Presently, the patient is on regular follow up. Repeat CECT scan showed no residual disease.

Discussion

Virchow microscopically characterised chordomas, for the first time, in 1857. He described the histology to be physaliferous: consisting of a unique, intracellular, bubble-like vacuolar appearance, a term now synonymous with their histopathology [3]. These are locally aggressive neoplasms, arising from notochord remnants.

Remnants of the notochord may be found anywhere along the axial skeleton, however, it was historically presumed that chordomas present in the sacrum more than in the skull base [4]. The current evidence shows equal distribution in the skull base (32%), mobile spine (32.8%), and sacrum (29.2%) [5]. Chordomas are more common in males and usually occur in the fifth to seventh decades [6]. Pathologically, chordromas are divided into three subtypes: conventional, chondroid and dedifferentiated [3].

Like other anterior skull base malignancies, the imaging protocol encompasses a combination of Computed Tomography (CT scan) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging(MRI). Chordomas are isointense (75%) to hypointense on T1- weighted images (T1WI). On T2-weighted images (T2WI), they are of high signal with heterogeneous signal noted in 79% cases [7, 8]. Diffusion weighted MRI, and ADC values help in distinguishing chondrosarcomas and chordomas radiologically.

The Chordoma foundation, in 2015, published a global consensus based on the input of experts from the fields of medical oncology, radiation oncology, neurosurgery, and orthopedic surgery during the 2013 European Society for Medical Oncology annual meeting [9]. While surgery with negative margins wherever possible is the mainstay of treatment, the management should be discussed extensively in multidisciplinary board meetings. Although complete resection is the norm, in an anatomically complex area like the skull base, subtotal resection, by open or endoscopic approaches may be acceptable to prevent debilitating effects of extensive resection [10]. In cases of low volume residual tumors, it was shown that high-dose radiotherapy is an effective management strategy [11].

While we have managed this patient with open surgery, endoscopic resection for clival tumors have developed and favored over the past few decades [12]. Limitations to endoscopic resection include tumor volume > 20 cc, lower clival lesion with lateral extension and recurrent disease. Appropriate reconstruction may be needed for extensive resection and CSF leaks.

Radiotherapy is not advocated as a primary treatment. However in an adjuvant setting, immediate post-operative radiotherapy showed benefits, especially in low dose residual disease [11]. The recommended radiation dose in these radioresistant tumors is of at least 74 Gy using conventional fractionation (1.8–2 Gy per fraction) preferably in the form of intensity modulated radiotherapy is recommended [13]. At present, there is no role of systemic chemotherapy in management of chordomas [14]. A summary of various studies related to skull base chordomas have been summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of literature on management of skull base chordoma

| Author | Year | Sample Size | Type of Study | Modality | Mean Follow up time | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tzortzidis et al. [15] | 2006 | 47 | Retrospective | Gross Tumor Resection (GTR) and Subtotal Tumor Resection | 86 months |

OS 67.9% after surgery at 10 years Recurrence-free survival at 10 years– 44.6% |

| Sen et al. [16] | 2010 | 71 | Retrospective | Radical surgery +/- PORT | 66 months |

OS at 5years: 75% Distant Metastasis free survival(DMFS) at 5 years: 98% |

| Koutourousiou et al. [12] | 2012 | 60 | Retrospective | Endoscopic Endonasal approach as an alternative to open surgery | 17.8 months | The mean recurrence-free period was 14.4 months. GTR achievable in 66.7% |

| Wu et al. [17] | 2010 | 106 | Retrospective | Outcomes following surgical resection | 64 months | 5-year OS and DMFS at 86% and 100% |

| Chugh R et al. [14] | 2005 | 51 | Phase II RCT | Role of 9-Nitro-Camptothecin (9-NC) in locally advanced/metastatic Chordoma | Not Reported | 9NC has no role in operable disease. It delays progression in unresectable/metastatic chordomas |

| Yasuda et al. [18] | 2012 | 40 | Retrospective | Surgery +/- Adjuvant Proton Beam | 57 months | 5-year OS and DMFS at 70% and 87% |

Conclusion

Chordoma of skull base is a rare group of tumors which is primarily managed by surgery. The role of radiotherapy is limited to adjuvant setting for curative intent, and there is no established role of systemic therapy at present. Chordomas, like all other skull base tumors need an extensive discussion in disease management groups for treatment planning and management.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and the next of kin. The approval of the ethical committee does not apply to individual case study. The therapeutic decision was made after a multidisciplinary meeting. Consent was informed and written for therapeutic management. Patient Consent Written informed consent was obtained from the patient?s next of kin for the publication of the report and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thompson LDR, Bishop JA (2022) Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck tumors: Nasal Cavity, Paranasal sinuses and Skull Base. Head Neck Pathol 16(1):1–18. 10.1007/s12105-021-01406-5Epub 2022 Mar 21. PMID: 35312976; PMCID: PMC9018924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bi WL, Santagata S (2022) Skull Base tumors: Neuropathology and Clinical implications. Neurosurgery 90(3):243–261. 10.1093/neuros/nyab209Epub 2021 Nov 24. PMID: 34164689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaniv D, Soudry E, Strenov Y, Cohen MA, Mizrachi A (2020) Skull base chordomas review of current treatment paradigms. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 6(2):125–131. 10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.01.008PMID: 32596658; PMCID: PMC7296475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heffelfinger MJ, Dahlin DC, MacCarty CS et al (1973) Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull base. Cancer 32:410–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, Ishibe N, Parry DM (2001) Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973e1995. Cancer Causes Control 12:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neill P, Bell BA, Miller JD, Jacobson I, Guthrie W (1985) Fifty years of experience with chordomas in southeast Scotland. Neurosurgery 16:166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sze G, Uichanco LS 3, Brand-Zawadzki MN et al (1988) Chordomas: MR Imaging Radiol 166:187e191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Meyers SP, Hirsch WL Jr, Curtin HD, Barnes L, Sekhar LN, Sen C (1992) Chordomas of the skull base: MR features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 13:1627e1636 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacchiotti S, Sommer J, Chordoma Global Consensus Group (2015) Building a global consensus approach to chordoma: a position paper from the medical and patient community. Lancet Oncol 16:e71–e83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh H, Harrop J, Schiffmacher P, Rosen M, Evans J (2010) Ventral surgical approaches to craniovertebral junction chordomas. Neurosurgery 66:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potluri S, Jefferies SJ, Jena R et al (2011) Residual postoperative tumour volume predicts outcome after high-dose radiotherapy for chordoma and chondrosarcoma of the skull base and spine. Clin Oncol (R Collradiol) 23:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koutourousiou M, Gardner PA, Tormenti MJ et al (2012) Endoscopic endonasal approach for resection of cranial base chordomas: outcomes and learning curve. Neurosurgery 71:614–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amichetti M, Amelio D, Cianchetti M, Giacomelli I, Scartoni D (2017) The treatment of chordoma and chondrosarcoma of the skullbase with particular attention to radiotherapy. Clin Oncol 2:1195 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chugh R, Dunn R, Zalupski MM et al (2005) Phase II study of 9-nitrocamptothecin in patients with advanced chordoma or soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 23:3597e3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzortzidis F, Elahi F, Wright D et al (2006) Patient outcome at long-term follow-up after aggressive microsurgical resection of cranial base chordomas. Neurosurgery 59(2):230–237. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000223441.51012.9D. discussion 230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen C, Triana AI, Berglind N, Godbold J, Shrivastava RK (2010) Clival chordomas: clinical management, results, and complications in 71 patients. J Neurosurg 113:1059–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z, Zhang J, Zhang L et al (2010) Prognostic factors for long-term outcome of patients with surgical resection of skull base chordomas-106 cases review in one institution. Neurosurg Rev 33:451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasuda M, Bresson D, Chibbaro S, Cornelius JF, Polivka M, Feuvret L, Takayasu M, George B (2012) Chordomas of the skull base and cervical spine: clinical outcomes associated with a multimodal surgical resection combined with proton-beam radiation in 40 patients. Neurosurg Rev 35(2):171–182 discussion 182-3. 10.1007/s10143-011-0334-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]