Abstract

Teratomas are rare tumors that originate from all three primary germinal layers and can develop anywhere along the body’s midline, most commonly in the sacrococcygeal area. Within the head-and-neck region, they are infrequent, especially in the oropharyngeal area, and predominantly occur in infants. This case report presents an unusual instance of a teratoma in the left palatine tonsil, also known as giant epignathus, of a 25-year-old female. The patient experienced a progressively enlarging mass over six to seven months without recurrent sore throat, fever, respiratory difficulties, or weight loss. Clinical and imaging assessments revealed a 2 cm x 3 cm irregular mass in the left palatine tonsil, which was surgically excised. Histopathology confirmed a mature teratoma. The patient was followed up for six months without evidence of recurrence. This case underlines the importance of considering teratomas in the differential diagnosis of tonsillar masses, even in adults, and highlights complete surgical excision as the treatment of choice to minimize recurrence risks and achieve optimal patient outcomes.

Keywords: Teratoma, Palatine tonsil, Mature teratoma, Oropharyngeal mass, Surgical excision

Introduction

Teratomas are rare tumors that originate from all the three primary germinal layers. These tumors are predominantly found in the sacrococcygeal area but can develop anywhere in the body along the midline [1]. Within the head-and-neck area, teratomas are relatively rare, with an estimated rate of 1 in 35,000 to 1 in 200,000 live births [2]. Head-and-neck teratomas account for 1–9% of all teratomas [3]. Teratomas occurring in head-and-neck region are mostly found in the cervical and nasopharyngeal areas with occurrences in oropharyngeal area being rarer [4]. Teratomas of the tonsils are exceedingly rare and almost exclusively occur in infants, particularly neonates. In this report, we present a unique case of a teratoma discovered in an adult. Despite their benign histopathology, oropharyngeal teratomas can pose a life-threatening risk due to their potential to obstruct the airway and compromise respiration.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old female presented to our institute with a progressively enlarging mass on the left side of her tonsil. The mass had been present for approximately 6–7 months and had increased in size over that period that was not associated with pain and congestion of tonsil. The patient did not report any recurrent episodes of sore throat, fever, or respiratory difficulties, nor were there any reports of weight loss. There was no previous history of HIV or immunodeficiency disorder. There was no history of unsafe sexual practices as well. Discomfort while feeding was the main presenting complaint.

Patient was admitted in ENT department and his baseline as well as specific investigations were ordered. In the same manner, the observations like blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR) and Temperature (Temp) was normal at the time of admission and remain so through out the stay in hospital. Similarly, the baseline investigations were also within the reference ranges. Upon detailed examination of the oral cavity, an irregular mass measuring 2 cm x 3 cm was observed as shown in Fig. 1. It was protruding from the left palatine tonsil and extending across the midline. The mass was mobile and non-pulsatile. Examination of the nose and nasal cavity revealed no abnormalities, and the cervical lymph nodes were not enlarged.

Fig. 1.

Showing the left tonsillar mass measuring 2 cm x 3 cm, extending from the left tonsillar fossa to the oropharynx

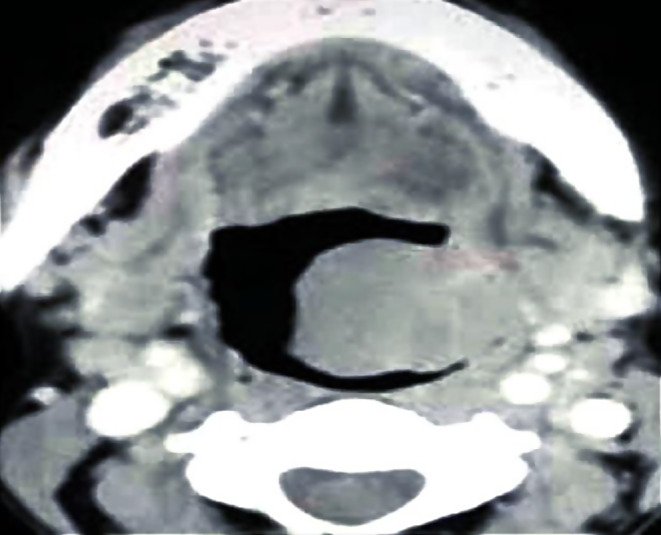

A Computed Tomography (CT) scan identified a fat attenuation cyst in the left tonsillar bed, with no evidence of intracranial extension. It also showed a Homogeneous soft tissue density mass measuring 2.3 cm X 3 cm on left side of oropharynx arising from tonsillar floor, crossing the midline and causing effacing the oropharyngeal column partially. It is well away from ipsilateral carotico-jugular complex that is appears patent. No surrounding enlarged cervical lymph nodes. The CT-scan demonstration is given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Showing the CT scan findings of the patient

The patient was prepared for surgery, and the mass was surgically excised. Histopathological examination confirmed the mass to be a mature teratoma originating from the left tonsil. Post-excision, the patient was followed up for a six-month period, during which there was no evidence of recurrence or new growth. The histopathological demonstration of the palatine tonsil is given in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Showing the histopathological description of the Tonsillar Teratoma with Neuro-ectodermal tissue on the left and mesodermal, ectodermal and endodermal tissues on the right

Discussion

Teratomas are rare neoplasms of uncertain etiology, comprising heterotrophic tissues that are typically not found at the site where they occur [5]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain their formation, with the prevailing notion suggesting abnormal proliferation of pluripotent cells sequestered during embryogenesis, resulting in disorganized structures, containing a variety of tissues [6]. This distinction is crucial, separating teratomas from hamartomas, which solely comprise indigenous tissues [7].

While teratomas are predominantly located in the sacrococcygeal region, accounting for the majority, the head and neck region represents a mere 5% of all cases. Teratomas typically manifest in infants under the age of one, with a higher incidence observed among neonates, our case stands out remarkably, as the teratoma presented in adulthood at the age of 25. Teratomas are usually benign neoplasms which have been classified into four types such as dermoid, teratoid, true teratoma, and epignathi. Of these teratomas, dermoids comprise the vast majority; true teratomas occur less frequently. Histologically, teratomas may present as mature or immature, or mixed tumors. In our case, a diagnosis of mature teratoma was confirmed. Mature teratomas are thought to have a benign character.

Imaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosing teratomas, particularly when they are well-differentiated, as they offer an opportunity for tissue characterization [8]. Various modalities such as lateral skull films, CT scans, and MRI have been employed for this purpose. CT and MRI often show a soft tissue mass filling the oropharynx, often exhibiting features like calcification and cystic formation. CT scans are generally preferred for identifying bony dehiscence. Some studies have employed angiography during preoperative assessments to exclude the presence of vascular lesions [9]. However, it is unnecessary if one is sure of the diagnosis. Additional preoperative evaluation may include aspiration of the mass to test for CSF and glucose content to rule out intracranial involvement [10]. Alternatively, fine needle aspiration may be utilized [11]. In our patient, a CT scan revealed a left tonsillar mass without signs of infiltration or intracranial extension. The presence of fatty components favored the diagnosis of teratoma. The usefulness of MRI is also an important factor in not only diagnosis, but also for follow up of the patient as well. The complementary role of MRI can also be utilized to see any airway obstruction by the mass and to rule out any intracranial extension. However, the CT scan findings were not suggestive of any extension therefore the mass was removed and patient was asked for Follow up.

Surgical excision remains the treatment of choice for mature tonsillar teratomas. Transoral resection, typically via transection at the base of the stalk is the preferred surgical approach. Recurrence is rare and is usually attributed to remnants of the original tumor or missed secondary lesions rather than true recurrence. Overall prognosis is favorable following complete excision.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report a rare case of teratoma in an adult involving the palatine tonsils. Despite their extreme rarity, teratomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially when presenting in an atypical age group. CT scan serves as a crucial diagnostic tool, aiding in accurate assessment and localization. Complete excision of the tumor remains imperative to minimize the risk of relapse and ensure optimal patient outcome.

Declarations

Human and Animal Participants

Humans were involved in this particular research.

Informed Consent

All patients were informed about the nature of the Project and their verbally and written consent was taken for participation in our study.

Conflict of interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tapper D, Lack EE (1983) Teratomas in infancy and childhood. A 54-year experience at the children’s Hospital Medical Center. Ann Surg 198(3):398–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenhaute B, Leteurtre E, Lecomte-Houcke M, Pellerin P, Nuyts JP, Cuisset JM, Soto-Ares G (2000) Epignathus teratoma: report of three cases with a review of the literature. Cleft palate-craniofacial Journal: Official Publication Am Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association 37(1):83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon MJ, Chescheir NC, Kuller JA, Wells SR, Wright LN, Nakayama DK (1996) Perinatal management of a lingual teratoma. Obstet Gynecol 87(5 Pt 2):848–851 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly A, Bough ID Jr, Luft JD, Conard K, Reilly JS, Tuttle D (1996) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Surg 31(5):704–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kountakis SE, Minotti AM, Maillard A, Stiernberg CM (1994) Teratomas of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol 15(4):292–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noguchi T, Jinbu Y, Itoh H, Matsumoto K, Sakai O, Kusama M (2006) Epignathus combined with cleft palate, lobulated tongue, and lingual hamartoma: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 101(4):481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graeme-Cook F, Pilch BZ (1992) Hamartomas of the nose and nasopharynx. Head Neck 14(4):321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell CG, Van Tassel P, Gammal E, T (1984) High resolution computed tomography in neonatal nasopharyngeal teratoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 8(6):1179–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe LD (1980) Neonatal airway obstruction secondary to nasopharyngeal teratoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1979) 88(3):221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt GR, Holt JE, Weaver RG (1979) Dermoids and teratomas of the head and neck. Ear Nose Throat J 58(12):520–531 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rybak LP, Rapp MF, McGrady MD, Schwart MR, Myers PW, Orvidas L (1991) Obstructing nasopharyngeal teratoma in the neonate. A report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117(12):1411–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]