Abstract

The NS2-NS3 region of the hepatitis C virus polyprotein encodes a proteolytic activity that is required for processing of the NS2/3 junction. Membrane association of NS2 and the autocatalytic nature of the NS2/3 processing event have so far constituted hurdles to the detailed investigation of this reaction. We now report the first biochemical characterization of the self-processing activity of a purified NS2/3 precursor. Using multiple sequence alignments, we were able to define a minimal domain, devoid of membrane-anchoring sequences, which was still capable of performing the processing reaction. This truncated protein was efficiently expressed and processed in Escherichia coli. The processing reaction could be significantly suppressed by growth in minimal medium in the absence of added zinc ions, leading to the accumulation of an unprocessed precursor protein in inclusion bodies. This protein was purified to homogeneity, refolded, and shown to undergo processing at the authentic NS2/NS3 cleavage site with rates comparable to those observed using an in vitro-translated full-length NS2/3 precursor. Size-exclusion chromatography and a dependence of the processing rate on the concentration of truncated NS2/3 suggested a functional multimerization of the precursor protein. However, we were unable to observe trans cleavage activity between cleavage-site mutants and active-site mutants. Furthermore, the cleavage reaction of the wild-type protein was not inhibited by addition of a mutant that was unable to undergo self-processing. Site-directed mutagenesis data and the independence of the processing rate from the nature of the added metal ion argue in favor of NS2/3 being a cysteine protease having Cys993 and His952 as a catalytic dyad. We conclude that a purified protein can efficiently reproduce processing at the NS2/3 site in the absence of additional cofactors.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive-stranded RNA virus (7, 19). HCV infection is an important health problem, being a major cause of chronic liver disease, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma and the main indication for liver transplantation in developed countries (9). Boosted by the medical importance of HCV, the characterization of the viral genome organization has progressed rapidly since its discovery, revealing that the genomic RNA serves as a messenger that is used to drive the formation of a single polyprotein chain of about 3,000 amino acids (7). Maturational processing of this polyprotein leads to the formation of at least 10 distinct gene products and is accomplished through the interplay of host cell signal peptidase and two virally encoded proteases located within the NS2-NS3 region (23). NS3 contains both a helicase and a serine protease domain (22, 37). The latter enzymatic function is activated upon complex formation with the viral protein NS4A (24) and is responsible for all of the cleavage events occurring downstream of NS3. Cleavage at the NS2/NS3 junction was proposed to occur in an intramolecular, Zn-dependent reaction (17). Upon processing of the NS2/NS3 junction, the NS2 product is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, forming a transmembrane polypeptide of unknown function (30). Truncation experiments indicated that the NS2/3 protease activity resides in a region of the polyprotein that spans from an N-terminal boundary located between residues 898 and 923 to a C-terminal end at residue 1207, even though constructs spanning only up to residue 1137 still show some residual activity (16, 17, 30). Optimal processing at the NS2/3 junction thus appears to necessitate the presence of the NS3 serine protease domain (residues 1027 to 1206 of the HCV polyprotein) as a structural unit but does not require its serine protease activity, as demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis experiments (16). The NS2 region shares no obvious sequence homology to known proteolytic enzymes. Furthermore, it is highly hydrophobic and is associated with membranes in infected cells (30). Since the NS2/3 protease activity was found to be stimulated by Zn and inhibited by chelating agents, it was tentatively classified as a metalloprotease, a hypothesis that has gained wide acceptance (17, 27). Biochemical and structural data have subsequently shown that the NS3 serine protease domain contains a tightly bound zinc ion that is absolutely required for its structural integrity (13). The zinc dependence of the NS2/3 protease activity could therefore be related to the role of this metal ion in stabilizing the fold of NS3 and not to its participation in the catalytic mechanism. Nevertheless, a hydrolytic function of the zinc binding site within NS3 cannot be ruled out. In fact, its possible spatial nearness to the NS2/3 junction in addition to the presence, in the zinc coordination sphere, of a well-defined water molecule has been discussed in terms of this metal binding site having a catalytic role in addition to its structural one (36). On the other hand, site-directed mutagenesis experiments have shown that C993 and H952, contained within NS2, are absolutely required for NS2/3 processing, leading to the suggestion that these residues might constitute the catalytic dyad of a novel cysteine protease (15, 36). It is also not known whether processing of the NS2/3 junction requires additional cellular proteins or low-molecular-weight cofactors.

Both HCV proteases are thought to be absolutely required for viral replication and are potential targets for specific antiviral pharmaceuticals (20). Whereas the HCV serine protease has been characterized in great detail and is at present the focus of drug discovery efforts (32), the characterization of the NS2/3 protease has been severely hampered so far due to its autocatalytic nature and to the presence of a large, hydrophobic region that is an impediment to efficient heterologous expression and purification. With the ultimate goal of reproducing the activity of NS2/3 in vitro using a purified enzyme, we first attempted a fine mapping of the boundaries of NS2/3 using structure prediction algorithms, trying to define a minimal catalytic entity that is devoid of the hydrophobic region. We show that N-terminally deleted NS2/3 constructs can be expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli cells. Up to 70% of the purified protein molecules undergo self-processing under appropriate conditions. This system allowed us to characterize for the first time the cleavage reaction under defined conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence analysis and structure prediction.

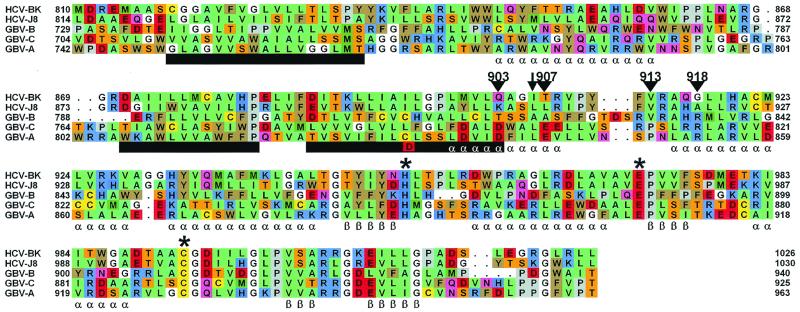

Sequences corresponding to the NS2 region of various HCV strains and the corresponding fragments of hepatitis G and GB viruses were aligned manually using Seaview software (14). Secondary structure prediction was achieved by submitting the aligned sequences of the HCV and GB virus group both separately and combined to the PHD (29) and JPRED (11) prediction servers. To reduce bias due to high sequence conservation within the groups, predictions were performed using alignments containing only sequences with less than 60% pairwise sequence identity. Prediction of transmembrane segments made use of the PHD (29), DAS (10), and HMMTM (31) algorithms. In Fig. 1, only a subset of sequences (maximum 55% pairwise sequence identity) used during the predictions are shown.

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of the NS2 region of HCV isolates and of the HCV-related viruses GBvirus B, GBvirus A, and GBvirus C. Predicted transmembrane regions are indicated as black bars below the alignment, and predicted secondary structure elements are indicated as α (helix) and β (strand). Truncation points for HCV NS2 are indicated as inverted black triangles above the alignment with an arrow showing the N-terminal end of the GB virus C NS2/NS3 protease–glutathione S-transferase fusion construct. Residues of the His-Glu-Cys sequence motif are indicated by asterisks. Sequences shown correspond to the polyprotein translations of GenBank accession no. M58335 (HCV-BK), D10988 (HCV-J8), U22304 (GBvirus B), D87714 (GBvirus C), and U22303 (GBvirus A) sequences. Amino acids are colored according to hydrophobicity.

Plasmid constructs.

Truncated NS2/3 constructs were obtained by PCR amplification of a cDNA template encoding the nonstructural region of the HCV J isolate using appropriate primers. PCR products were phosphorylated directly in the PCR mix with T4 polynucleotide kinase and cloned into a pT7.7 bacterial expression vector, using the NdeI restriction site. Ligations were performed using the Rapid DNA Ligation kit (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions. Mutations were introduced by PCR amplification of cDNA sequences using mutagenic primers. All of the constructs were routinely sequenced on both strands to exclude the introduction of mutations by the amplification procedure.

In vitro translation.

In vitro translation assays were performed with the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. For each reaction, 1 μg of RNA was translated in a reaction mixture containing 30 mM CH3COOK, 360 μM MgCl2, 30 μM amino acid mix minus methionine, 10 μl of reticulocyte lysate, 90 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 μl of radioactively labeled methionine (Amersham), 1 μl of RNasin (Promega), and water to 33 μl. Radiolabeled proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were fixed in destaining solution for 30 min, followed by 30 min of soaking in Amplify solution (Amersham) under gentle shaking, dried on 3MM paper, and subjected to autoradiography.

Expression in E. coli.

pT7.7 vectors harboring truncated NS2/3 protease sequences were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3). Cells were grown in standard M9 minimal medium supplemented with 200 μM ZnCl2 at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. Temperature was then decreased to 23°C, and protein induction was initiated by the addition of 400 μM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). For the expression of unprocessed NS2/3 precursor protein, ZnCl2 was not included in the medium. After 3 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation.

Purification of the unprocessed NS2/3 protease from inclusion bodies.

Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (40 ml/liter of growth medium) containing 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 3 mM DTT, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% CHAPS [3-(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio-1-propanesulfonate], and 15% glycerol and disrupted using a French pressure cell. MgCl2 (10 mM) was added to the homogenate, which was then incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the presence of 8 U of DNase per ml and 20 μg of RNase A per ml and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 × g. The pellet was washed twice with lysis buffer, once with lysis buffer supplemented with 1% NP-40, and once with 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5)–3 mM DTT. The protein was then resuspended in 7 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM Tris (pH 8.7)–100 mM DTT and loaded on a 26/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5)–3 mM DTT–150 mM NaCl and operating at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The fractions containing NS2/3 were pooled and loaded on a 0.5- by 20-cm Source 15RPC reversed-phase chromatography column (Pharmacia) equilibrated in 90% H2O–0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (solvent A) and 10% acetonitrile–0.08% TFA (solvent B). A gradient from 10 to 90% solvent B in 1 h at a flow rate of 4 ml/min was used to elute the NS2/3 protein in a pure form from this column. The NS2/3-containing fractions were pooled and lyophilized, and the protein was resolubilized in 7 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM Tris (pH 8.7)–100 mM DTT. Typically, the protein had a purity of >95%, as determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) done on a C4 Vydac column (4.6 by 125 mm) and was obtained with a yield of >2 mg/liter of bacterial culture. Purified proteins were routinely characterized by electrospray mass spectrometry done on an API100 instrument (Perkin-Elmer) and by N-terminal sequence analysis using Edman degradation on a 470A gas-phase sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Protein concentrations were determined by quantitative amino acid analysis or spectrophotometrically using the molar absorption coefficient ɛ = 40,200 M−1 cm−1.

Refolding of the purified NS2/3 protease and activity assays. (i) Method A.

A solution of 2.5 μM NS2/3 protease in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM Tris (pH 8.7)–100 mM DTT was diluted 50-fold into a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 3 mM cysteine, 50% glycerol, 1% CHAPS, 50 μM ZnCl2, and 250 mM NaCl (refolding buffer A) at a temperature of 4°C. After 5 min, the temperature was rapidly raised to 23°C, thereby initiating the cleavage reaction. The yield of refolded, active protein reached up to 70% and is highly dependent on buffer composition and on protein concentration and amino acid composition of the NS2/3 precursor.

(ii) Method B.

A solution (200 μl) containing 3 μM NS2/3 protease in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM Tris (pH 8.7)–100 mM DTT was dialyzed against 20 ml of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–50 μM ZnCl2–3 mM DTT–750 mM guanidine hydrochloride (refolding buffer B) using a SpectraPor dialysis membrane with a cutoff of 3.5 kDa. The dialysis was performed at 4°C. After 2 h, the protein solution was withdrawn, aliquoted, and shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen. No cleavage occurred during this dialysis, and the protein could be activated to undergo cleavage upon addition to a buffer that supports the cleavage reaction as outlined below. Proteins refolded according to method B were diluted at least fivefold into refolding buffer A. At timed intervals, aliquots were withdrawn, the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.1% SDS, and samples were loaded on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed upon electrophoresis by silver staining or by Western blotting. Proteins refolded according to method A were incubated at 23°C for up to 2 h in refolding buffer A and analyzed in the same way. Alternatively, 200-μl aliquots were withdrawn at timed intervals and 20 μl of 10% TFA was added to stop the reaction. The solution was then injected on a Poros R1/H reversed-phase perfusion chromatography column (4.6 by 50 mm; PerSeptive Biosystems) equilibrated with 90% H2O–0.1% TFA (buffer A) and 10% acetonitrile–0.08% TFA (buffer B). The column was operated at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min using a Merck-Hitachi high-performance liquid chromatograph equipped with a fluorescence detector. A gradient from 10 to 90% solvent B in 15 min was used to separate the precursor from its cleavage fragments. By monitoring of tryptophan fluorescence (excitation, 280 nm; emission, 350 nm), less than 5 nM protein could be reliably detected and quantified by peak integration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Subjecting HCV NS2 sequences to prediction algorithms aimed at identifying transmembrane segments gave no conclusive answer about their number or location. While cleavage of the NS2 N terminus from the E2/p7 protein occurs through a signal peptidase within the endoplasmic reticulum, processing at the NS2/NS3 juncture has instead to happen in the cytosolic space. In order to obtain a plausible membrane topology, an uneven number of transmembrane segments had therefore to be postulated. It was further assumed that the segments could be shorter than prototype helical transmembrane motifs, a feature also present in envelope proteins of HCV and other flaviviruses (8). Three segments of generally hydrophobic character were therefore manually identified by analyzing a multiple sequence alignment of HCV NS2 proteins, the last segment ending around NS2 residue 902 (Fig. 1). An analogous analysis was then performed on aligned fragments of putative NS2 proteins of the related GB virus family, which were subsequently manually aligned against the group of HCV NS2 sequences. Significant sequence similarity between the two groups was present only in the C-terminal part (approximately the last 80 residues) of the alignment, the region that contains a conserved sequence motif (His-Glu-Cys) whose integrity has been demonstrated elsewhere to be essential for NS2/NS3 cleavage (16, 17, 30). In the N-terminal part of the alignment, no obvious conserved sequence patterns could be detected, and the two groups were instead aligned primarily according to the conservation of hydrophobicity. Since the last predicted transmembrane segment in the HCV group matched a similar segment in the GB virus group, the start of the C-terminal cytoplasmic portion of NS2 was placed at NS2 residue 903. Additional support for this hypothesis came from the experimental results of Belyaev and coworkers, who expressed a truncated functional GB virus C NS2/NS3 protease as a C-terminal fusion to glutathione S-transferase (3). With respect to the aligned HCV NS2 sequences, the truncation point (residue 805 of the GB virus C polyprotein) was located close to the predicted start of the C-terminal cytoplasmic portion of HCV NS2. To account for possible errors in the prediction, four truncated versions of the HCV NS2 protein were designed. The first two (at residues Q903 and T907, respectively) start immediately after the last predicted transmembrane segment, assuming that the complete predicted C-terminal cytoplasmic portion of NS2 is necessary for NS2/NS3 protease activity. For the third and fourth truncation (starting at residues V913 and G918, respectively), the helix predicted to exist between residues 915 and 928 was instead taken as the first structurally and/or functionally important segment.

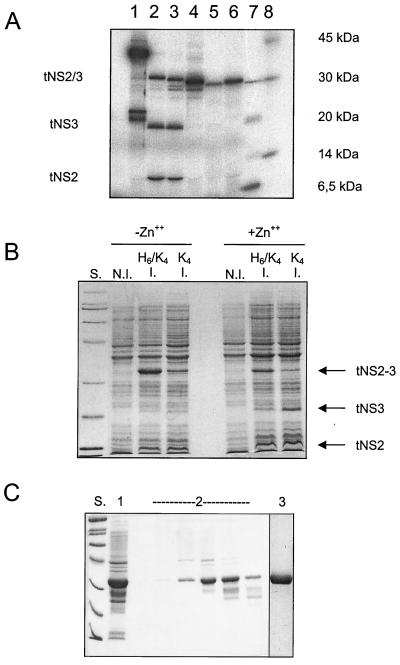

Truncated proteins starting at residue 903, 907, 913, or 918 and ending at residue 1206 were tested in a coupled in vitro transcription-translation system (Fig. 2). In line with the predictions, truncations up to residue 907 resulted in proteins that were still capable of autoprocessing whereas further deletions abolished activity (Fig. 2). An NS2/3(907–1206) construct carrying the solubilizing sequence tag ASKKKK, henceforth termed NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4, was also efficiently expressed and underwent autoprocessing in E. coli (Fig. 2). Addition of an N-terminal histidine tag to our truncated NS2/3 construct increased protein production but decreased the relative amount of cleavage products (Fig. 2). Our next aim was to maximize the expression of uncleaved precursor protein in a way that would allow its purification and subsequent reactivation in vitro. To this end, we took advantage of our previous observation that the NS3 protease domain requires Zn for proper folding (13). The zinc concentration present in minimal growth medium is not sufficient to replenish the NS3 zinc binding site, thereby leading to the accumulation of unfolded protein in inclusion bodies (13). In analogy to what happens with the NS3 protease domain, NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 or His-tagged NS2/3(907–1206)H6/ASK4 also was produced mainly in an insoluble form if induced in minimal medium (data not shown). Furthermore, induction in minimal medium decreased the extent of the self-processing reaction, presumably because under these conditions the proper folding of the NS3 portion of the molecule that is necessary for the cleavage reaction is impaired (Fig. 2). This procedure allowed easy purification to homogeneity of the uncleaved NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 precursor from E. coli inclusion bodies (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Identification, expression, and purification of truncated NS2/3 protease. (A) In vitro translation of NS2/3 protease constructs with different N termini spanning the indicated residues of the HCV polyprotein: lane 1, residues 810 to 1206 carrying C-terminal ASKKKK extension; lane 2, residues 903 to 1206; lane 3, residues 907 to 1206; lane 4, residues 913 to 1206; lane 5, residues 918 to 1206; lanes 7 and 8, molecular mass markers. (B) Expression of NS2/3(907–1206) constructs in E. coli carrying either the solubility-enhancing sequence ASKKKK (labeled K4) at the C terminus or, in addition, a six-histidine tag at the N- terminus (labeled H6/K4), visualized on a Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were induced by the addition of IPTG, as described in Materials and Methods (lanes labeled I.), and the band pattern was compared to that for the preinduction controls (lanes labeled N.I.). E. coli BL21 cells were grown in minimal medium with no further additions (“−Zn++”) or in minimal medium supplemented with 200 μM ZnCl2 (“+Zn++”). (C) Purification of NS2/3(907–1206) ASK4 from E. coli shown on a Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel. Lane S, molecular weight markers; lane 1, washed inclusion bodies; lanes 2, peak fractions from size-exclusion chromatography; lane 3, pure protein after reversed-phase chromatography.

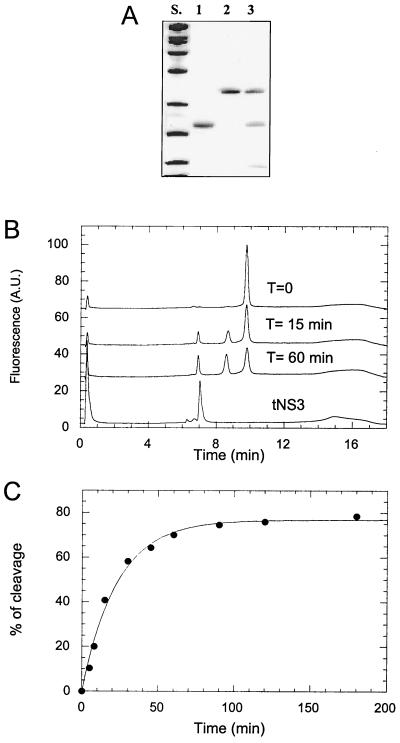

Attempts to refold the purified NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 protein under conditions where the isolated NS3 protease domain quantitatively regains activity (33) failed, indicating that the presence of the truncated NS2 sequence considerably alters physicochemical properties of the protein and/or its folding pathway. We therefore set up a systematic screen for refolding conditions (6) to identify factors that crucially influence the reaction. As readout, we chose to monitor the percentage of soluble protein after 100,000 × g centrifugation and the recovery of NS3 protease activity as well as the capability of the precursor protein to undergo self-cleavage (see below). Following these parameters, the stepwise optimization of physicochemical conditions led to the following composition of the refolding buffer: 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 50% glycerol, 1% CHAPS, and 3 mM DTT (refolding buffer A; see Materials and Methods). Under these conditions, the refolded protein underwent time-dependent self-processing that could be monitored by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or by reversed-phase perfusion HPLC (Fig. 3). In both cases, one of the cleavage fragments comigrated with an appropriate NS3 standard. This fragment was isolated and characterized by N-terminal sequence analysis using Edman degradation. The sequence found, A-P-I-T, is consistent with the cleavage reaction of the purified protein occurring at the authentic NS2/3 junction between residues 1026 and 1027 of the HCV polyprotein. Up to 70% of the denatured precursor protein could be refolded, as inferred from the maximum percentage of processed NS2/3 precursor after an overnight reaction. Notably, the amount of refolded protein measured following NS3 serine protease activity coincided with the amount of precursor protein capable of self-cleavage (data not shown). Under the same conditions, NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 proteins carrying either the C993A, H952A, or L1026P plus A1027P mutations did not undergo processing, whereas a protein carrying the single A1027P mutation showed some residual cleavage activity (data not shown). The cleavage reaction of the wild-type protein was also impaired by the addition of EDTA, and inhibition by this chelating agent could be overcome by addition of Zn (data not shown). The time course of the cleavage reaction could be fitted to a single exponential equation (Fig. 3). The apparent first-order rate constant obtained from this fit, kobs = 0.05 min−1, was very similar to that of a full-length construct analyzed upon in vitro translation (12), for which kobs = 0.04 min−1 was obtained. This indicates that the N-terminal truncation of our purified protein is not significantly affecting the efficiency of the processing reaction. It has to be pointed out that, even though our data show that processing at the NS2/3 junction can be accomplished by a purified truncated protein, efficient processing of the full-length precursor in infected cells might still require other cofactors such as chaperones.

FIG. 3.

In vitro processing of purified NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4. (A) To 200 nM NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 refolded according to protocol A (Materials and Methods), 5% trichloroacetic acid was added either immediately (lane 2) or after 1 h of incubation at 23°C (lane 3). The samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 25,000 × g, resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and loaded on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel. In lane 1, NS3(1027–1206)ASK4 was loaded as a standard. Lane S, molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad): from bottom to top, 14.5, 21.5, 31, 45, 66, 97.4, 116, and 200 kDa. (B) NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 (100 nM) was refolded according to protocol A and either immediately quenched with 10% TFA (T = 0) or incubated for 15 or 60 min prior to TFA addition. Samples were analyzed by HPLC using reversed-phase chromatography. A.U., arbitrary units. (C) Cleavage kinetics of 50 nM NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 were analyzed by HPLC, and data were fitted with a single exponential equation.

We subsequently investigated the NS3 protease activity of our refolded truncated NS2/3 protease. To this end, we used the H952A mutant that did not show detectable NS2/3 protease activity. The NS3 protease active-site concentration in our refolded NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4H952A preparation was determined by titration with a tight-binding NS3 protease inhibitor (26) and was used to normalize protein concentrations. Next, the affinity for an NS3 protease NS4A cofactor peptide (34) and the kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of two NS3 peptide substrates were determined for both the NS3 protease domain (residues 1026 to 1207 of the HCV polyprotein) and our truncated NS2/3 precursor (residues 907 to 1207). The data, summarized in Table 1, are indicative of the NS2 portion having no major effect on either cofactor or substrate binding by the NS3 serine protease moiety of the precursor. Neither did the NS2 sequence significantly affect the catalytic constants of peptide substrate hydrolysis by the NS3 serine protease domain.

TABLE 1.

NS3 serine protease activity of refolded NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4H952Aa

| Construct | Km Pep1 (μM) | kcat Pep1 (min−1) | Km Pep2 (μM) | kcat Pep2 (min−1) | Kd Pep4AK (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS3(1026–1206)ASK4 | 8 | 30 | 17 | 8 | 0.47 |

| NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 H952A | 14 | 26 | 49 | 5 | 0.12 |

Peptide cleavage and Pep4AK cofactor binding were measured as previously described (34). The NS3 protease domain was purified according to previously published procedures (13), whereas NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4H952A was purified and refolded according to method A as described in Materials and Methods. Assay conditions were as follows. Cleavage of Pep1 (EAGDDIVPCSMSTWTGA), derived from the NS5AB junction of the HCV polyprotein, and the equilibrium dissociation constant Kd for the cofactor peptide Pep4AK (KKKGSVVIVGRIILSGR) were measured in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–15% glycerol–3 mM DTT–150 mM NaCl–0.05% Triton X-100. Cleavage of the substrate Pep2 (DEMEECASHLPYK), corresponding to the NS4AB cleavage site of the HCV polyprotein, was determined in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–15% glycerol–3 mM DTT–0.05% Triton X-100.

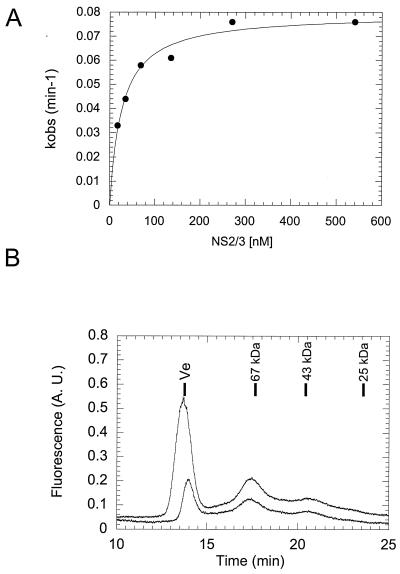

We set out to further characterize the NS2/3 cleavage reaction using our truncated precursor protein and the optimized buffer conditions. An unexpected finding was that the rate of the cleavage reaction depended on the concentration of the NS2/3 precursor protein (Fig. 4A). From the data in Fig 4A, we estimated 30 nM as the concentration of NS2/3 precursor giving a half-maximal cleavage rate. For an intramolecular reaction, no such concentration dependence would be predicted. In contrast, a concentration dependence of the reaction rate could be explained by assuming that the active species is a dimer or a multimer. This observation therefore induced us to gain more information about the multimeric state of the refolded protein by using size-exclusion chromatography. The optimized buffer required to observe the processing reaction was incompatible with chromatographic analysis due to its viscosity. In addition, substantial cleavage is expected to occur prior to detection during a chromatographic run performed under conditions where NS2/3 is active. By monitoring protein fluorescence as a function of chaotrope concentration, we found that the NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 protein would refold in the presence of 0.75 M guanidine hydrochloride but that this concentration of chaotropic agent would not allow the cleavage reaction to occur (data not shown). Taking advantage of this finding, we refolded NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 by dilution into our optimized refolding buffer and immediately loaded the sample on a size-exclusion column equilibrated with a buffer containing 0.75 M guanidine hydrochloride. Under these conditions, the resulting chromatogram revealed the presence of three species (Fig. 4B): one eluting with the void volume and thus probably representing an aggregate formed during the refolding procedure and two additional species eluting with apparent molecular masses of 72 and 38 kDa. Taking into account, the fact that the molecular mass of our truncated NS2/3 construct is 33 kDa, detection of a 72-kDa species by gel filtration chromatography is compatible with the formation of a dimer. The same sample showed a single peak when analyzed on a reversed-phase column (data not shown), indicating that noncovalent interactions were responsible for dimerization. Increasing the protein concentration slightly increased the intensity of the 72-kDa peak but also dramatically augmented the fraction of the protein eluting with the void volume, indicating that aggregation was becoming the dominant reaction at protein concentrations above 200 nM (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Dimerization of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4. (A) The rate constants kobs obtained from a fit of the processing kinetics of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 were plotted as a function of protein concentration. (B) NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 (200 [lower curve] or 500 [upper curve] nM) refolded according to method A (Materials and Methods) was loaded on an HR10/10 Superdex 75 size-exclusion chromatography column equilibrated in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–3 mM DTT–0.75 M guanidine hydrochloride–50 μM ZnCl2 and operating at 0.4 ml/min. Protein elution was monitored by monitoring tryptophan fluorescence (excitation, 280 nm; emission, 350 nm) on a Merck-Hitachi L-7840 fluorescence detector. The bars indicate the elution positions of blue dextran (Ve) and of the indicated molecular mass markers. A. U., arbitrary units.

Our data may help to rationalize previous reports about trans-cleavage activity of NS2/3 obtained in cells (28, 35). In those experiments, it was shown that NS2/3 constructs defective in either the NS2 or the NS3 portion were able to trans-complement each other. In addition, NS2/3 proteins carrying mutations in residue H952 or C993 and therefore unable to self-process and constructs in which cleavage was prevented through mutagenesis of the NS2/3 cleavage site were also shown to trans-complement each other, resulting in cleavage of the active-site mutant (28, 35). trans-cleavage activity may require the prior formation of a stable complex. We therefore attempted to investigate a possible cleavage reaction in trans using our truncated NS2/3 protein. Incubation of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4L1026P+A1027P (cleavage-site mutant) and either NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4C993A or NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4H952A (active-site mutant) failed to lead to detectable cleavage products (data not shown). Also, addition of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4C993A to the wild-type NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 protein failed to negatively affect its cleavage kinetics (data not shown). Such an inhibition would be expected for an obligate trans-cleavage reaction. A possible explanation for the apparent discrepancy of our findings with the data reported earlier by Reed and colleagues (28) may come from the analysis of the refolding efficiency of our mutant constructs, which was consistently two- to threefold lower than that observed for the wild-type protein (data not shown). Furthermore, size-exclusion chromatography of the H952A or C993A mutant revealed a considerably lower amount of dimeric form than that for the wild-type protein (data not shown). If the trans-cleavage reaction is less efficient because of a higher dimer dissociation constant of the mutant proteins, we might simply not generate enough heterodimer in our assay conditions, which could explain our failure to detect trans-cleavage or trans- inhibition. On the other hand, refolding yields decrease with increasing protein concentration, which sets a practical limit to the range of protein concentrations that can be explored in our assay system.

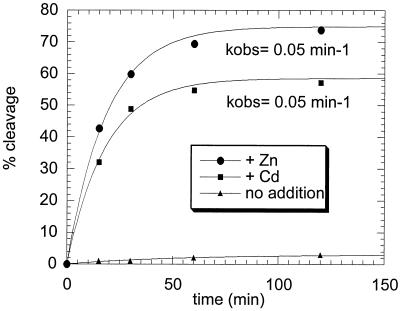

We next focused on the question about the mechanism of the cleavage reaction. Cysteine- or metalloprotease-specific mechanism-based inhibitors attached to a pentapeptide derived from the sequence of the NS2/3 cleavage site (GWRLL carrying either an aldehyde or a hydroxamic acid moiety) failed to inhibit the reaction, as did several peptides spanning the cleavage site (Table 2). As previously reported by other (17), EDTA was found to significantly inhibit the reaction (Table 2). The lack of inhibition by peptide-derived inhibitors might indicate that the active site of the protein is not readily accessible to relatively large peptides. The active-site zinc of several zinc proteases can be replaced by other metal ions. Substitution of cadmium for zinc results in an impaired amide bond hydrolysis in carboxypeptidase A (2), matrilysin (5), thermolysin (18), and Clostridium hydrolyticum gamma and zeta collagenases (1). In contrast, refolding of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 in the presence of cadmium under conditions where proteolytic activity absolutely depends on added metal ions did not significantly affect the cleavage kinetics (Fig. 5), which argues in favor of a structural role of the metal ion and against its involvement in the catalytic mechanism. These data agree with a previous report showing that NS2/3 protease activity could be restored by addition of cadmium after EDTA addition to an in vitro-translated precursor protein (27).

TABLE 2.

Inhibition of the in vitro processing reaction of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4a

| Compound (mM) | % Inhibition |

|---|---|

| DSFGEQGWRRLLAPITAYSQQTR (0.1) | <5 |

| EQGWRRLLAPITAYS (0.1) | <5 |

| GWRRLLAPITA (0.1) | <5 |

| Ac-GWRRLL-CHO (0.1) | <5 |

| Ac-GWRRLL-CONHOH (0.1) | <5 |

| TPCK (0.5) | 35 |

| IAM (0.5) | 25 |

| NEM (5) | 70 |

| EDTA (2) | 60 |

| H2O2 (0.5) | 87 |

NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 (50 nM) was refolded according to method A as described in Materials and Methods. Incubation with inhibitors was done on ice for 15 min. The temperature was rapidly raised to 23°C using a Thermomixer, and reactions were stopped after 15 min and analyzed by HPLC. Percent inhibition was calculated by integration of the NS3 peak area with respect to a control sample. In the peptides spanning the NS2/3 cleavage site, the residues flanking the scissile bond are shown in boldface. TPCK, tosyl phenyl chloromethyl ketone; IAM, iodoacetamide; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide.

FIG. 5.

Refolding kinetics of NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 in the presence of Zn or Cd. All solutions were treated with Chelex resin to remove adventitious metal ions. NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 (2.5 μM) in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride–25 mM Tris (pH 8.7)–100 mM DTT–1 mM EDTA was refolded by 50-fold dilution into 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–3 mM cysteine–50% glycerol–1% CHAPS–250 mM NaCl or into the same buffer supplemented with either 100 μM ZnCl2 or 100 μM CdCl2. The processing reaction was monitored by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. The lines through the experimental points are fittings to a single exponential equation.

Cysteine proteases are characterized by having a highly reactive thiolate anion as a nucleophile in their active sites. This thiolate anion is activated by a nearby histidine residue and readily reacts with thiol-reactive agents (4). The presence of a peculiarly reactive cysteine residue in NS2/3 would be a strong indication in favor of a cysteine protease being responsible for the processing of the NS2/3 junction. NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 is in fact highly susceptible to inactivation by the alkylating agents N-ethylmaleimide, tosylphenyl chloromethyl ketone, and iodoacetamide (Table 2). Analysis of the iodoacetamide-inactivated protein by mass spectrometry, however, revealed that this inactivation was highly unspecific, with all of the nine cysteine residues present in the protein eventually becoming modified. This is likely to reflect the relatively unspecific, high reactivity of the reagents used in this experiment. More specific inhibitors such as E-64 or dipyridyl disulfide did not inhibit (data not shown). We noticed that NS2/3(907–1206)ASK4 is sensitive to oxidative inactivation (e.g., by H2O2 [Table 2]) and absolutely requires reducing agents for activity. DTT as a reducing agent had also to be added to the denatured protein in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride prior to refolding in order to obtain an active protein. We found that when DTT was replaced by β-mercaptoethanol in this step a progressive, time-dependent inactivation of the protein occurred. Tryptic digestion and mass spectrometric analysis demonstrated a covalent modification of the protein by β-mercaptoethanol on several cysteine residues, comprising Cys993 (data not shown; a detailed report will be published elsewhere). Again, a peculiar reactivity of this residue with respect to other cysteines could not be conclusively demonstrated. Our data thus do not allow an unambiguous assessment of the catalytic mechanism of the NS2/3 cleavage reaction. However, they do favor the cysteine protease hypothesis. In fact, taking into account the essential role of Cys993 and His952 in the cleavage reaction as well as our metal substitution experiments showing that the cleavage rate is unchanged in the presence of either Zn or Cd, the most likely explanation is that these residues indeed form the catalytic dyad of a novel cysteine protease. This active site appears not to be readily accessible either to peptides or to low-molecular-weight thiol reagents.

It is of interest to compare the maturation of NS2/3 in HCV with that occurring in the evolutionarily related pestiviruses. In bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), a pestivirus that may cause fatal mucosal disease in cows, cytopathogenicity strictly correlates with processing at the NS2/3 site. In fact, noncytopathogenic BVDV strains produce an uncleaved NS2/3 precursor protein. The mature form of NS3 that is present in cytopathogenic BVDV strains may arise by several different molecular mechanisms, including RNA recombination or point mutations within NS2 (21, 25). Possibly, the NS2 region of pestiviruses contains a highly inefficient proteolytic activity that becomes activated by mutations. The identification of catalytic domains in pestivirus NS2, based on the findings of this work, is, however, not straightforward due to the relatively low sequence similarity with the corresponding region of HCV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Raffaele De Francesco for many helpful discussions. We also thank Concetta Capo and Raffaele Petruzelli for N-terminal sequence analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angleton E L, Van Wart H E. Preparation by direct metal exchange and kinetic study of active site metal substituted class I and class II Clostridium histolyticum collagenases. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7413–7418. doi: 10.1021/bi00419a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auld D S, Valle B L. Carboxypeptidase A. In: Neuberger A, Brocklehurst K, editors. Hydrolytic enzymes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1989. pp. 201–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belyaev A S, Chong S, Novikov A, Kongpachith A, Masiarz F R, Lim M, Kim J P. Hepatitis G virus encodes protease activities which can effect processing of the virus putative nonstructural proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:868–872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.868-872.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocklehurst K, Willenbrock F, Salih E. Cysteine proteinases. In: Neuberger A, Brocklehurst K, editors. Hydrolytic enzymes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1989. pp. 39–158. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cha J, Pedersen M V, Auld D S. Metal and pH dependence of hepatapeptide catalysis by human matrilysin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15831–15838. doi: 10.1021/bi962085f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen G Q, Gouaux E. Overexpression of a glutamate receptor (GluR2) ligand binding domain in Escherichia coli: application of a novel protein folding screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13431–13436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choo Q-L, Kuo G, Weiner A J, Overby L R, Bradley D W, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocquerel L, Wychowski C, Minner F, Penin F, Dubuisson J. Charged residues in the transmembrane domains of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins play a major role in the processing, subcellular localization, and assembly of these envelope proteins. J Virol. 2000;74:3623–3633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3623-3633.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Consensus Panel. EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis C, Paris, 26–28 February 1999, consensus statement. J Hepatol. 1999;30:956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cserzo M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 1997;10:673–676. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuff J A, Clamp M E, Siddiqui A S, Finlay M, Barton G J. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:892–893. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darke P, Jacobs A R, Waxman L, Kuo L. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus NS2/3 processing by NS4A peptides. Implications for control of viral processing. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34511–34514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Francesco R, Urbani A, Nardi M C, Tomei L C, Steinkühler, Tramontano A. A zinc binding site in viral serine proteinases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13282–13287. doi: 10.1021/bi9616458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorbalenya A E, Snijder E J. Viral cysteine proteases. Perspect Drug Discov Des. 1996;6:64–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02174046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grakoui A, McCourt D W, Wychowski C, Feinstone S M, Rice C M. A second hepatitis C virus-encoded proteinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10583–10587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hijikata M, Mizushima H, Akagi T, Mori S, Kakiuchi N, Kato N, Tanaka T, Kimura K, Shimotohno K. Two distinct proteinase activities required for the processing of a putative nonstructural precursor protein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1993;67:4665–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4665-4675.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland D R, Hausrath A C, Juers D, Matthews B W. Structural analysis of zinc substitutions in the active site of thermolysin. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1955–1965. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houghton M. Hepatitis C viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven, Publishers; 1996. pp. 1035–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolykhalov A A, Mihalik K, Feinstone S M, Rice C M. Hepatitis C virus-encoded enzymatic activities and conserved RNA elements in the 3′ nontranslated region are essential for virus replication in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:2046–2051. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.2046-2051.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kümmerer B M, Stoll D, Meyers D. Bovine viral diarrhea virus strain Oregon: a novel mechanism for processing of NS2–3 based on point mutations. J Virol. 1998;72:4127–4138. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4127-4138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong A D, Kim J L, Rao G, Lipovsek D, Raybuck S A. Hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. Antivir Res. 1998;40:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohman V, Koch J O, Bartenschlager R. Processing pathways of the hepatitis C virus proteins. J Hepatol. 1996;24:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Love R A, Parge H E, Wickersham J A, Hostomsky Z, Habuka N, Moomaw E W, Adachi T, Margosiak S, Dagostino E, Hostomska Z. Conformational changes in hepatitis C virus NS3 proteinase during NS4A complexation: correlation with enhanced cleavage and implications for inhibitor design. In: Schinazi R F, Sommadossi J P, Thomas H C, editors. Therapies for viral hepatitis. London, United Kingdom: International Medical Press; 1998. pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers G, Thiel H J. Molecular characterization of pestiviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:53–118. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narjes F, Brunetti M, Colarusso S, Gerlach B, Koch U, Biasiol G, Fattori D, De Francesco R, Matassa V, Steinkühler C. Alpha-ketoacids are potent slow binding inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1849–1861. doi: 10.1021/bi9924260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieroni L, Santolini E, Fipaldini C, Pacini L, Migliaccio G, La Monica N. In vitro study of the NS2–3 protease of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1997;71:6373–6380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6373-6380.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed K, Grakoui A, Rice C M. Hepatitis C virus-encoded NS2–3 protease: cleavage site mutagenesis and requirements for bimolecular cleavage. J Virol. 1995;69:4127–4136. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4127-4136.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santolini E, Pacini L, Fipaldini C, Migliaccio G, La Monica N. The NS2 protein of hepatitis C virus is a transmembrane polypeptide. J Virol. 1995;69:7461–7471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7461-7471.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonnhammer E L, von Heijne G, Krogh A. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1998;6:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinkühler C, Koch U, Narjes F, Matassa V. Inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:919–932. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urbani A, Bazzo R, Nardi M C, Cicero D, De Francesco R, Steinkühler C, Barbato G. The metal binding site of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. A spectroscopic investigation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18760–18769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urbani A, Biasiol G, Brunetti M, Volpari C, Di Marco S, Sollazzo M, Orrù S, Dal Piaz F, Casbarra A, Pucci P, Nardi C, Gallinari P, De Francesco R, Steinkühler C. Multiple determinants influence complex formation of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease domain with its NS4A cofactor peptide. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5206–5215. doi: 10.1021/bi982773u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson C S. Hepatitis C virus NS2–3 proteinase. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:611. doi: 10.1042/bst025s611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Z, Yao N, Le H V, Weber P. Mechanism of autoproteolysis at the NS2-NS3 junction of the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:92–94. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao N, Reichert P, Taremi S S, Prosise W W, Weber P C. Molecular views of viral polyprotein processing revealed by the crystal structure of the hepatitis C virus bifunctional protease-helicase. Struct Fold Des. 1999;15:1353–1563. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]