Abstract

The murine cytomegalovirus CC chemokine homolog MCK-2 (m131-129) is an important determinant of dissemination during primary infection. Reduced peak levels of viremia at day 5 were followed by reduced levels of virus in salivary glands starting at day 7 when mck insertion (RM461) and point (RM4511) mutants were compared to mck-expressing viruses. A dramatic MCK-2-enhanced inflammation occurred at the inoculation site over the first few days of infection, preceding viremia. The data further reinforce the role of MCK-2 as a proinflammatory signal that recruits leukocytes to increase the efficiency of viral dissemination in the host.

Primary infection with human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is associated with shedding in saliva and other body fluids (42). This virus encodes functions that modulate the host immune response (22, 23) and that influence host cell or tissue tropism (39). Due to the strict species specificity of CMVs, murine CMV has been used to gain insights into viral pathogenesis and latency (24), host immune control of virus infection (27), and viral modulation of the host immune response (22, 23). Human and murine CMVs have a colinear genome organization (46) and encode immunomodulatory functions that carry out analogous functions during infection (22, 23). Gene products that function in similar ways sometimes retain little amino acid sequence similarity in these two viruses. For example, murine and human CMVs rely on nonhomologous gene products to downmodulate major histocompatibility complex class I gene expression (1, 22, 23, 25, 61), and both have major histocompatibility complex class I homologs that are nonhomologous themselves, although both influence natural killer cell behavior (17, 31, 47).

The chemokine receptor US28 (20, 41, 56) is not conserved in murine CMV, although two other seven-transmembrane-spanning G-protein-coupled receptor homologs, M33 and M78, are (46). Both murine and human CMVs encode gene products with chemokine-like activities (35, 36, 43, 49); however, they represent different chemokine classes and lack amino acid sequence similarity. The human CMV UL146 gene encodes vCXC-1, a CXC chemokine (43), and the murine CMV m131-129 gene encodes MCK-2, a CC chemokine homolog (19, 35, 36, 49). Viral chemokine homologs (3, 14, 30, 33, 40, 67) may function as chemokines to increase leukocyte migration or may act as antagonists that block the migration of leukocyte subsets (6, 13, 15, 16, 26, 28, 43, 49, 54) to host chemokines (4, 7, 48, 63). Chemokines regulate cell effector functions such as granule release and cytokine expression, contributing to both the quality and the magnitude of inflammatory responses (2, 11, 34, 50, 58, 66). Human CMV vCXC-1 activates neutrophils via CXCR2 very much like interleukin 8 (43) and could influence neutrophil behavior (21, 51). Murine CMV open reading frame (ORF) m131 was initially predicted to encode an 81-aminio-acid (aa) chemokine, designated MCK-1, based on the presence of C spacing motifs typically conserved in CC chemokines (36). A predicted processed 63-aa synthetic form of MCK-1 was found to induce calcium flux on murine peritoneal macrophages and THP-1 cells but to neither bind to nor inhibit the binding of host chemokines to other leukocyte populations (49). This behavior led us to propose a model where MCK-1 recruits a subset of mononuclear leukocytes during viral infection (49; N. Saederup, Y. C. Lin, T. Schall, and E. S. Mocarski, Abstr. 23rd International Herpesvirus Workshop, York, England, abstr. 340, 1998).

The principal transcript arising from the m131 region was found to contain an intron such that the spliced mRNA created an in-frame fusion between MCK-1 and 199 codons that included the entire m129 ORF (19, 35). This m131-129 fusion was denoted MCK-2 (35) and was shown to be expressed as a true late (γ2) gene product (60) secreted into the medium during infection (35). Although functional evaluation of MCK-2 has not been undertaken, studies of synthetic MCK-1 (49) predicted that MCK-2 would be proinflammatory because all 81 aa of MCK-1 are contained in MCK-2. Consistent with this prediction, mck mutant viruses exhibited reduced levels of viremia and poor dissemination to salivary glands (19, 49, 55) without having an impact on dissemination to other organs, such as the spleen, liver, and lungs. Reduced dissemination to salivary glands appeared independent of the capacity to mount an adaptive immune response (55) but may be influenced by the natural killer cell response (19).

Murine CMV disseminates in two distinct phases (12) via peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes (5, 55). Primary viremia within 2 days after inoculation (12) is believed to seed sites such as the spleen, liver, lungs, and brown fat (12, 55). A readily detected secondary viremia peaks at 5 days after inoculation (12, 49, 55); from this the salivary glands, a major site of murine CMV replication and shedding, become seeded (55). Five recombinant viruses, RM461 (8, 55) (Fig. 1), RMΔ461-1 (8), Δm131Z (19), Δm131ns (19), and RM4485 (49), all of which carry mutations in the mck gene, have been shown to exhibit reduced peak titers in salivary glands. RM461 and RM4485 were shown to exhibit reduced peak levels of viremia (49). It has been found that dissemination of mck mutant viruses to other organs, including the spleen, liver, lungs, adrenal glands, kidneys, and brown fat, remains largely unaltered (8, 49, 55). Latency and reactivation characteristics of mck mutants are similar to those of wild-type viruses (8). We undertook the current study to investigate the nature of the impact of mck expression on the behavior of virus or host cells at the site of inoculation. Our study shows that mck expression is associated with a strong cellular inflammatory response at the site of inoculation and that this activity is dependent on the conserved CC chemokine motif in mck gene products.

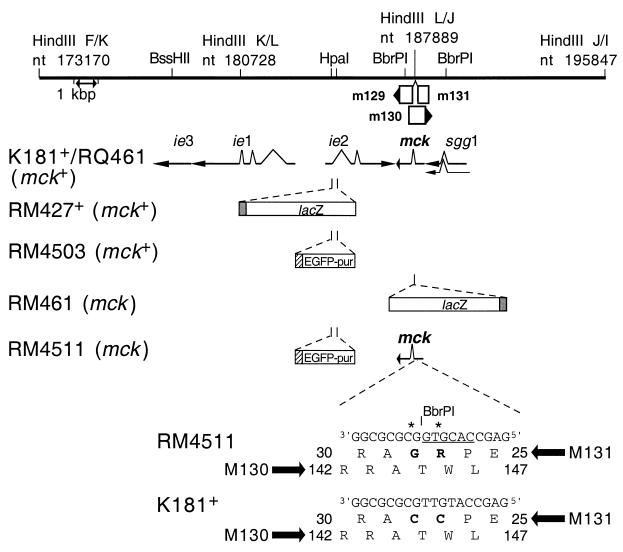

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of mutant virus genomes. The top line represents a restriction map of the HindIII K, L, and J DNA fragments in murine CMV strain K181+, corresponding to nts 173170 to 195847 of the Smith strain genome (46) (GenBank accession number U68299). Restriction sites for HindIII and selected BssHI, HpaI, and BbrPI sites are indicated above the line, and a 1-kbp scale marker is indicated by a double-headed arrow below the line. Open boxes with arrowheads depict the positions of viral ORFs, with m131 and m129 contributing the coding sequences for MCK-2 (35). m130 overlaps mck on the opposite DNA strand (46). Solid arrows depict transcripts (ie1, ie3, ie2, mck, and sgg1) encoded by wild-type viruses. The mutations introduced into mutant viruses RM427+, RM4503, RM461, and RM4511 are depicted below the transcripts. The 3.9-kbp lacZ insert carried by RM427+ and RM461 (open box) is controlled by a 199-bp human CMV ie1-ie2 promoter fragment (shaded box) encompassing positions −219 to −19 relative to the transcription start site (8, 37, 55). The 1.7-kbp EGFP-puro insert in RM4503 and RM4511 (open box) is controlled by a 248-bp human CMV ie1-ie2 promoter fragment (hatched box) encompassing positions −242 to +7 relative to the transcription start site (59). The expanded region shows aa 25 to 30 of m131 and aa 142 to 147 of m130, including the two nucleotide point mutations (denoted by asterisks) introduced into RM4511, generating a new BbrPI site (underlined) and altering the MCK-2 amino acid sequence (C27R and C28G; bold type). Wild-type strain K181+ nucleotide and amino acid sequences are shown at the bottom.

Construction of recombinant viruses to assess the mck chemokine motif.

First, we isolated RQ461, a rescue of the mck mutation in RM461 (49, 55). Then, we constructed mutant virus RM4511, with a mutation in the conserved CC chemokine motif (Fig. 1). Rescued virus RQ461 was constructed by transfecting MluI-linearized pON4457 into RM461-infected cells by use of Superfect (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and, after harvesting at 72 hours postinfection, expanding viral progeny at a low multiplicity of infection (<0.1) on NIH 3T3 cells. pON4457 (59) carries a wild-type murine CMV DraI/EcoRI fragment (nucleotides [nts] 183086 to 189674), spanning the sgg1, mck, and ie2 genes, as well as the major immediate-early enhancer, cloned into pGEM-2 (Promega, Milwaukee, Wis.).

To select for recombinants and to reduce the likelihood of isolating viruses with adventitious mutations (55), the virus pool was passaged twice through mice by inoculating footpads and screening salivary gland sonicates 14 days later for lacZ-deficient plaques. Viruses were isolated and subjected to three rounds of limiting dilution purification. White plaques were observed with pON4457 but not with control plasmid pME18S (57). Initially, two independent isolates of RQ461 were selected based on replacement of the lacZ insert with a wild-type copy of the mck gene (Fig. 1). Both of these isolates exhibited growth properties similar to those of the wild-type parental virus, and one of these was designated RQ461.

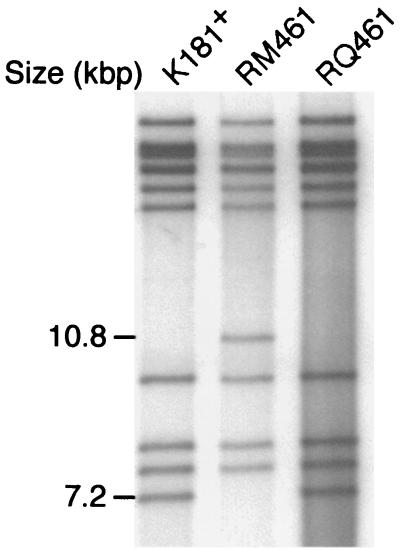

The RQ461 genome structure was compared to those of RM461 and K181+ by separation of [α-32P]dCTP-end-labeled HindIII-digested virion DNA by agarose gel electrophoresis. Virion DNA (0.5 to 1.0 μg) was digested with HindIII, BssHII, AflII, or SpeI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and end labeled in the presence of 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham), 125 μM each dATP, dGTP, and dTTP, and 0.5 U of Klenow polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.) for 15 min at room temperature in 20 μl of restriction enzyme buffer. Restriction fragments were separated on a 0.6% agarose gel, which was fixed in 95% ethanol and vacuum dried at 80°C, followed by autoradiography. RQ461 displayed a restriction pattern distinct from that of mutant RM461 but similar to that of wild-type K181+ (Fig. 2). Restriction digest analysis using AflII, HpaI, or SspI showed that the genome of the rescued virus did not contain detectable adventitious deletions or rearrangements (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Restriction digestion analysis of RQ461 DNA. Autoradiograph of 32P-end-labeled HindIII fragments from K181+, RM461, and RQ461 DNA following electrophoretic separation on a 0.7% agarose gel.

All previously characterized mck mutant viruses (19, 49), including RM461, disrupt the m130 ORF located on the cDNA strand in addition to the intended disruption of m131. The m130 ORF, predicted from genome sequence analysis of murine CMV (46), completely overlapped the chemokine domain of m131 (Fig. 1); however, m130 has not been subjected to evaluation. In order to establish that the phenotype of mck mutant viruses was independent of m130, point mutations were introduced to disrupt the two adjacent conserved amino-terminal cysteines of m131. These would be expected to eliminate the chemokine activity of mck gene products based on the well-established role of this conserved CC motif in forming disulfide bonds that are critical for chemokine function (9, 10, 45). We changed these two adjacent cysteines in m131 to arginine and glycine (C27R and C28G) in a way that did not alter the sequence of m130 (A144 and T145; Fig. 1) or any other known ORF within the murine CMV genome (46).

pON4511 was constructed by replacing a 393-bp AflII/BssHII fragment of pON4503 which spans the amino terminus of mck (murine CMV nts 188185 to 188577) with a PCR-generated AflII/BssHII fragment containing T79C and T82G mutations of mck, resulting in C27R and C28G mutations of the MCK-2 protein. PCR was conducted with primers 5′GAGGCTATCTTAAGACTATC3′ and 5′GCGCGCCACGTGGCTCGCGGAGGTCC3′, pON4457 as a template, and an Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The PCR fragment was cloned into pGEMT-EZ (Promega), and the sequences of both DNA strands were determined prior to ligation into AflII/BssHII-digested pON4503. This mutation created a BbrPI site (CACGTG) that was used to aid in the isolation of plasmid pON4511 and recombinant virus RM4511. In addition to the mutation, RM4511 was engineered to carry an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-puromycin (EGFP-puro) cassette (59) within the ie2 gene to facilitate selection (Fig. 1). ie2 mutant viruses have been repeatedly found to exhibit wild-type growth patterns in cell cultures as well as after experimental infection of mice (8, 32, 59; S. A. Aguirre, unpublished data). The mck CC mutant virus RM4511 was made by the same protocol as RQ461, except that RM427+ virus (32, 49) was the parent and AflII/PacI-linearized pON4511 contained the mutation in addition to the EGFP-puro marker (59). After two rounds of selection, RM4511 transfection pools were expanded under low-multiplicity-of-infection conditions in tissue cultures and passaged through mice as described for RQ461. Individual RM4511 clones (designated RM4511.1 and RM4511.2) were isolated from independent pools by two rounds of limiting dilution and two rounds of plaque purification using a β-galactosidase substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) overlay (37) to confirm the absence of parental virus RM427+ (<1 plaque/106 PFU).

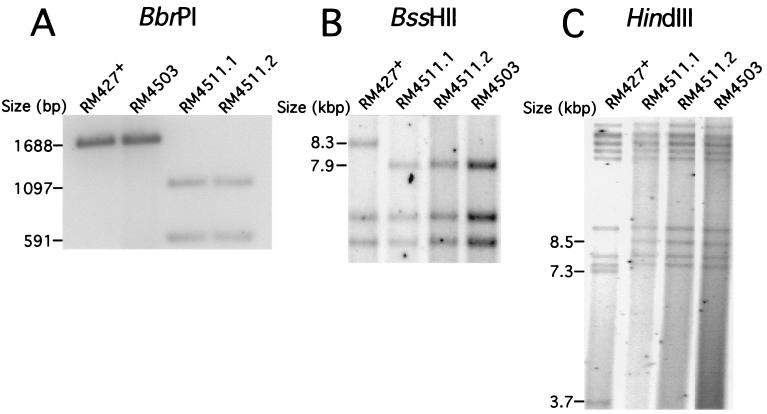

RM4511 DNA was subjected to blot hybridization analysis to detect the introduced BbrPI site by following established protocols (37, 44, 60). A HindIII/AflII fragment from pON4457 (murine CMV nts 187890 to 188578) was radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP as an mck probe (18). This detected 1,097 and 591-bp BbrPI restriction fragments in RM4511 DNA. DNA from parental virus RM427+ or EGFP control virus RM4503 (59) had only the expected 1,688-bp BbrPI fragment (Fig. 3A) of the wild-type mck gene. Thus, the substitution mutations had been introduced at the correct genomic locations. To confirm the position of the EGFP-puro insert, end-labeled BssHII DNA fragments were generated from all viruses, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and subjected to autoradiography to reveal a 7.9-kbp RM4511 fragment in place of the 8.3-kbp fragment observed in parental virus RM427+ (Fig. 3B). Thus, the EGFP-puro cassette was inserted within the ie2 gene of RM4511 in a manner similar to that in RM4503 (59). RM4511 DNA was also digested with HindIII, generating the expected 8.5-kbp fragment instead of the two fragments (3.7 and 7.3 kbp) found in RM427+ DNA. No adventitious genomic deletions or rearrangements were detected in RM4503 or either of the RM4511 isolates when subjected to HindIII, SpeI, or BssHII restriction analysis (Fig. 3C and data not shown). Together, these results demonstrated that both independent RM4511 isolates carried the intended substitution mutations in mck and the marker gene insert in ie2. As expected from extensive analyses of previous ie2 mck double mutants in cultures and in mice (8), the two independent RM4511 isolates produced peak titers in NIH 3T3 cells that were indistinguishable from those of K181+ and RM427+ (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Restriction digestion analysis of RM4511 DNA. (A) Detection of the RM4511 mck mutation by BbrPI digestion. Autoradiograph of BbrPI-digested (Roche) virion DNA from parental RM427+, RM4503, and two isolates of RM4511 (RM4511.1 and RM4511.2) following electrophoretic separation on a 1% agarose gel and hybridization with a HindIII/AflII fragment mck probe. (B) Detection of the EGFP-puro insert in RM4503 and RM4511. Autoradiograph of electrophoretically separated, BssHII-digested 32P-end-labeled DNA fragments. (C) Autoradiograph of electrophoretically separated 32P-end-labeled HindIII fragments of DNA from RM427+, RM4503, and two isolates of RM4511.

Role of mck in peripheral blood mononuclear cell-associated viremia.

Previous studies of mck mutant viruses in mice suggested that this gene affected the behavior of host mononuclear cells in a way that resulted in poor dissemination to salivary glands (8, 19, 49, 55). Although our studies have discounted any impact on the adaptive immune response or viral latency, one study suggested that mck modulated the host immune response (19). To date, precise m131-specific mutations have not been studied, so differences in the behavior of mutant viruses may have resulted from an impact on viral genes, such as m130, that overlap m131 (19, 49). We compared the growth properties of mck mutants and control viruses, initially evaluating peak levels of viremia at 5 days postinoculation (106 PFU, intraperitoneal [i.p.] route). PBLs were collected from CO2-asphyxiated mice for coculturing with permissive NIH 3T3 cells. Peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) were washed, suspended in growth medium at 106 cells/ml, serially diluted, and subjected to an infectious-center assay on NIH 3T3 cells overlaid with complete growth medium (37) containing 0.75% carboxymethyl cellulose. For this and all other experiments, groups of female mice (3 to 5 weeks of age) were used with the approval of the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

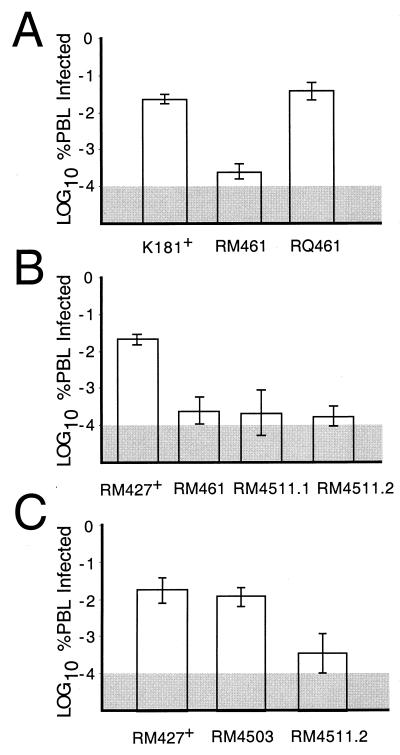

Peak viremia was reduced 50- to 100-fold in mice infected with RM461 compared to either rescued virus RQ461 or parental wild-type virus K181+ (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous observations (49). To investigate the contribution of the conserved chemokine sequence motif in m131, mice were inoculated with RM461, RM4511.1, RM4511.2, RM4503, or RM427+; PBLs were harvested at 5 days postinoculation for assay. The previously observed decrease in RM4511.1 or RM4511.2 infection resulted in peak viremia that was 25- to 50-fold lower than that seen with either parental virus RM427+ (Fig. 4B) or control virus RM4503 (Fig. 4C). These results showed that mck expression correlated with increased viremia, that mck function depended upon the conserved CC motif, and that the m130 ORF did not contribute to the phenotype.

FIG. 4.

Evaluation of peak levels of viremia at 5 days after i.p. inoculation of BALB/c mice with 106 PFU. (A) Comparison of K181+, RM461, and RQ461. (B) Comparison of RM427+, RM461, RM4511.1, and RM4511.2. (C) Comparison of RM427+, RM4503, and RM4511.2. PBLs (106) were harvested and subjected to an infectious-center assay on NIH 3T3 cells. Bar height indicates the geometric mean, and vertical bars indicate standard deviations of the geometric mean. The shaded area indicates the limit of detection of virus.

Dissemination of mck mutants after inoculation.

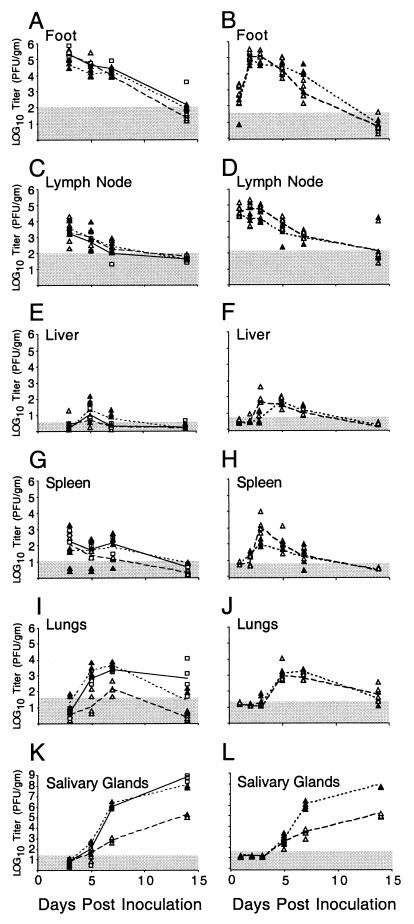

We used the footpad inoculation route to evaluate whether mck influenced dissemination to salivary glands as it does following i.p. inoculation (8, 19, 49). This inoculation route introduces virus in the periphery at a location more distal to organs and tissues that become involved during acute infection. This route may also be considered a model of natural transmission that is dependent on animal behavior such as biting. The impact of mck on viral dissemination was examined in several independent experiments (Fig. 5). We observed lower virus titers in the salivary glands at day 7 or 14 postinoculation with RM461 than with K181+ or rescued virus RQ461 (Fig. 5K and L). Following either i.p. or footpad inoculation, mck mutant or wild-type viruses reached peak levels in the salivary glands between days 14 and 21 and began to decrease by day 28 (8, 55; J. Huang, unpublished data). Footpads (Fig. 5A and B), draining popliteal lymph nodes (Fig. 5C and D), and organs such as the liver and spleen (Fig. 5E through H) showed similar titers for all viruses tested. Except for the significantly reduced titers in the salivary glands, growth of the mck mutant viruses could not be distinguished from that of the wild-type virus. Although a report (19) suggested that viral replication in the spleen and liver may be influenced by mck, we have not detected any consistent differences (Fig. 5 and data not shown). In our experiments, variable virus titers in the spleen, liver, and lungs have sometimes been observed (8), but these differences are not consistently associated with a particular virus genotype, as exemplified by the data in Fig. 5I and J.

FIG. 5.

Replication patterns for RM461, RQ461, and K181+ in BALB/c mice. Experiment 1 (A, C, E, G, I, and K) shows virus titers in organs at 3, 5, 7, and 14 days postinoculation (four animals per group). Experiment 2 (B, D, F, H, J, and L) shows titers at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 14 days postinoculation (five animals per group). Footpads of 3-week-old BALB/c mice were inoculated with 106 PFU. Titers in organ sonicates were determined by plaque assays on NIH 3T3 cells. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. K181+ (□), RM461 (▵), and RQ461 (▴) were the viruses used. The lines connect the geometric means for each virus (solid, K181+; dotted, RQ461; dashed, RM461). The shaded area indicates the limit of detection of virus.

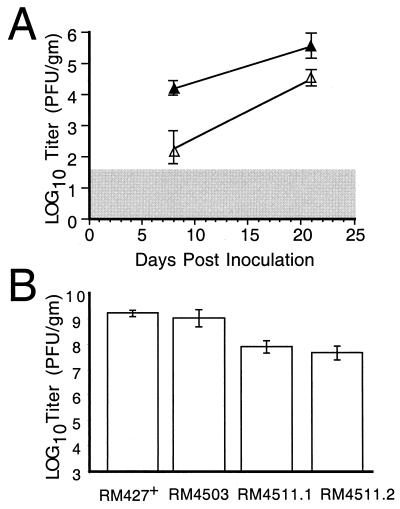

The high inoculum dose (106 PFU) used for experimental infection likely exceeds the dose typical of natural infection. To evaluate the impact of mck on dissemination under low-dose conditions, groups of five mice were inoculated i.p. with either 102 or 104 PFU of mck mutant or control virus. Virus titers in salivary glands at 8 and 21 days postinoculation showed that the mck phenotype was preserved at a dose of as low as 102 PFU (Fig. 6A) as well as at a dose of 104 PFU (data not shown). Thus, the mck gene plays an important role as a determinant of dissemination at high doses as well as at low doses that better approximate natural transmission. Interestingly, titers of either virus in salivary glands were significantly lower than when higher doses were used and were most variable following the lowest dose. Despite the variability, the impact of mck on the levels of virus present in this tissue remained highly significant over a broad range of doses using either tissue culture-derived or salivary gland-passaged virus inocula (8, 19, 49, 55; this study).

FIG. 6.

Dissemination of mck mutant viruses to salivary glands. (A) Levels of RM461 (▵) or RQ461 (▴) in the salivary glands at 8 and 21 days postinoculation of 100 PFU into footpads of 3-week-old BALB/c mice (four animals per group). (B) Levels of RM427+, RM4503, RM4511.1, and RM4511.2 in the salivary glands at 14 days postinoculation of 106 PFU into footpads of 3-week-old BALB/c mice (four animals per group). Titers of organ sonicates were determined by plaque assays on NIH 3T3 cells, and mean values were plotted. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations of the geometric mean. The shaded area indicates the limit of detection of virus.

To assess the contribution of the m131 CC chemokine motif to dissemination, salivary gland sonicates were collected at 14 days postinoculation with RM4511.1, RM4511.2, RM4503, or RM427+. The RM4511 isolates replicated to levels 10- to 30-fold lower than those of control mck-expressing viruses (Fig. 6), consistent with a role for the CC chemokine motif in dissemination to this tissue. Although RM4503 and RM427+ replicated to similar levels (P > 0.3; Student's two-sided t test) that were comparable to those of wild-type K181+ (Fig. 5K), differences between any of the control viruses and the RM4511 isolates were significant (P values determined by Student's two-sided t test of RM4503 compared to either RM4511.1 or RM4511.2 were <0.002 and <0.0008, respectively). When RM4511.1 and RM4511.2 were isolated from salivary gland sonicates and analyzed, both retained the BbrPI restriction site indicative of the introduced mutation (data not shown). These results show that the CC chemokine motif mutation was stable and suggest a substantial proinflammatory activity for mck.

It was previously reported (49) that low-level viremia of mck mutant virus was complemented by coinoculation with mck-expressing virus. In order to determine whether mck-expressing virus was able to complement mutant virus dissemination to salivary glands, lacZ-tagged mck mutant virus RM461 was inoculated i.p. alone or together with control virus RM4503 into groups of four BALB/c mice. We used 2 × 106 PFU of RM461 or 1 × 106 PFU of RM4503 for independent inoculation and 1 × 106 PFU of RM461 plus 5 × 105 PFU of RM4503 (1.5 × 106 PFU total) for coinoculation. Virus titers in salivary gland sonicates were determined at 5, 7, and 15 days postinoculation. In tissues from the coinfected animals, lacZ-expressing mck mutant RM461 plaques were distinguished from RM4503 plaques by staining with X-Gal. RM461 titers were enhanced 4- to 50-fold in coinoculated animals (Table 1), the highest levels of complementation being observed on day 7 postinoculation. At this time, the ratio of titers for RM461 and RM4503 in the coinfected mice was 0.1, compared to 0.002 for independently inoculated mice. Apparently, mck mutant virus was able to disseminate 50 times more efficiently in coinfected mice. RM461 levels in salivary glands were also complemented by RM4503 at day 5, when titers were very low, as well as at day 15 postinoculation, when peak levels of virus were observed at this site (55). The variations in these ratios were entirely due to differences in the levels of RM461. Titers of mck-expressing virus RM4503 were unaltered by the presence of mutant virus (data not shown). The peak complementation at day 7 followed the period of peak viremia (49) and coincided with the initial rise in viral replication levels in salivary glands (Fig. 5), suggesting that the expression of MCK-2 (35) by RM4503 increased the dissemination of mutant virus RM461.

TABLE 1.

Complementation of mck mutant dissemination to salivary glands

| Mouse infection | RM461/RM4503 ratio at the following days postinoculation:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 7 | 15 | |

| Independenta | 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Combinedb | 0.9c | 0.1 | 0.06 |

Four mice per time point were inoculated with 1 × 106 PFU of RM4503 or 2 × 106 PFU of RM461. The data are the ratios of the mean salivary gland titers of RM461 and RM4503 cohorts at the indicated time.

Four mice per time point were coinoculated with 5 × 105 PFU of RM4503 and 1 × 106 PFU of RM461. The data are the means of individual ratios of paired RM461-RM4503 salivary gland titers calculated for each coinfected mouse.

Three mice were assayed in this group.

Modulation of foot swelling by mck.

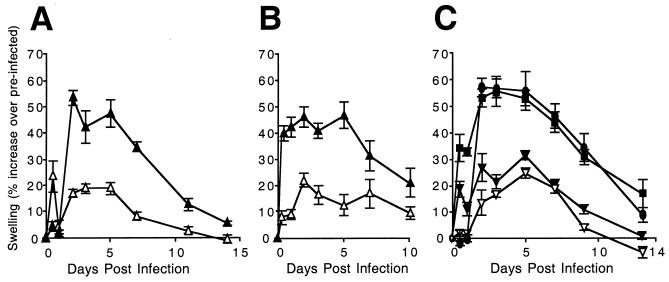

Foot thickness, measured with a caliper, can provide an indicator of local inflammatory responses, particularly in conjunction with direct histological evaluation of tissue sections (62, 64, 65). Groups of 3-week-old BALB/c mice were inoculated (106 PFU) with mck mutant or rescued virus, and the foot thickness of restrained mice was measured before and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, and 14 days after inoculation using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan). Virus-infected mice did not show outward signs of illness, so to control investigator bias, all inocula were coded. Foot swelling was defined as the percent increase in thickness relative to the preinoculation measurement. This variation in foot thickness in different groups of mice was found to be low, between 0.3 and 0.7%, based on measurements taken over a 2-week period. We found that mck mutant virus RM461 induced significantly less swelling than either rescued virus RQ461 (Fig. 7A) or parental wild-type virus K181+ (data not shown). A consistent pattern developed by day 2, when the level of swelling in RQ461-inoculated feet increased markedly, about 50% over preinoculation levels, compared to the results obtained with RM461. These levels were maintained through day 5, started to decline by day 7, and approached baseline by day 14 for all viruses. All swelling resulted from the effects of virus in the inoculum because tissue culture medium alone failed to elicit any response (data not shown). The differences in swelling corresponded to the expected timing of expression of MCK-2 (35), starting at day 2, and were consistently observed in several independent experiments (Fig. 7). Swelling continued throughout the period during which viral replication was detected (Fig. 5A and B). The induction of an mck-dependent swelling response correlated with the true late (γ2) kinetics of mck expression (35). Swelling before 48 h, when MCK-2 is expressed, was variable without regard to virus genotype or inoculum dose. The appearance of dramatic, sustained differences in inflammation starting at day 2 provided confirmation for the suggested proinflammatory role of mck (19, 49).

FIG. 7.

Time course analysis of footpad swelling. (A and B) Measurement of RM461 (▵)- or RQ461 (▴)-induced swelling following footpad inoculation of 3-week-old BALB/c mice in groups of five (A) or four (B) animals. (C) Measurement of RM4511.1 (▾)-, RM4511.2 (▿)-, RM4503 (•)-, or RM427+ (▪)-induced swelling following footpad inoculation of three 5-week-old mice. Mice were inoculated with 106 PFU of virus. Foot thickness was measured with a digital caliper at the times indicated after inoculation, and mean values were plotted. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations of the mean.

To assess whether the m131 CC chemokine motif contributed to the intensity of the swelling response, we evaluated foot swelling during infection with either of the RM4511 isolates (Fig. 7C). The level of swelling induced by RM4511.1 or RM4511.2 was similar to that induced by mck mutant virus RM461 (Fig. 7A and B) and was lower than that induced by either parental virus RM427+ or control virus RM4503 (Fig. 7C). RM427+ induced swelling similar to that seen with other mck-expressing viruses, almost 60% above preinoculation levels in this experiment and more than double that observed following inoculation of RM4511.1 or RM4511.2. A similar pattern was induced by other mck-expressing viruses throughout a 10- to 14-day observation period (data not shown). Taken together, these data show that the increased swelling induced by wild-type viruses is dependent upon the conserved CC chemokine motif in m131, further implicating MCK-2 as a proinflammatory protein.

Modulation of local inflammation by mck.

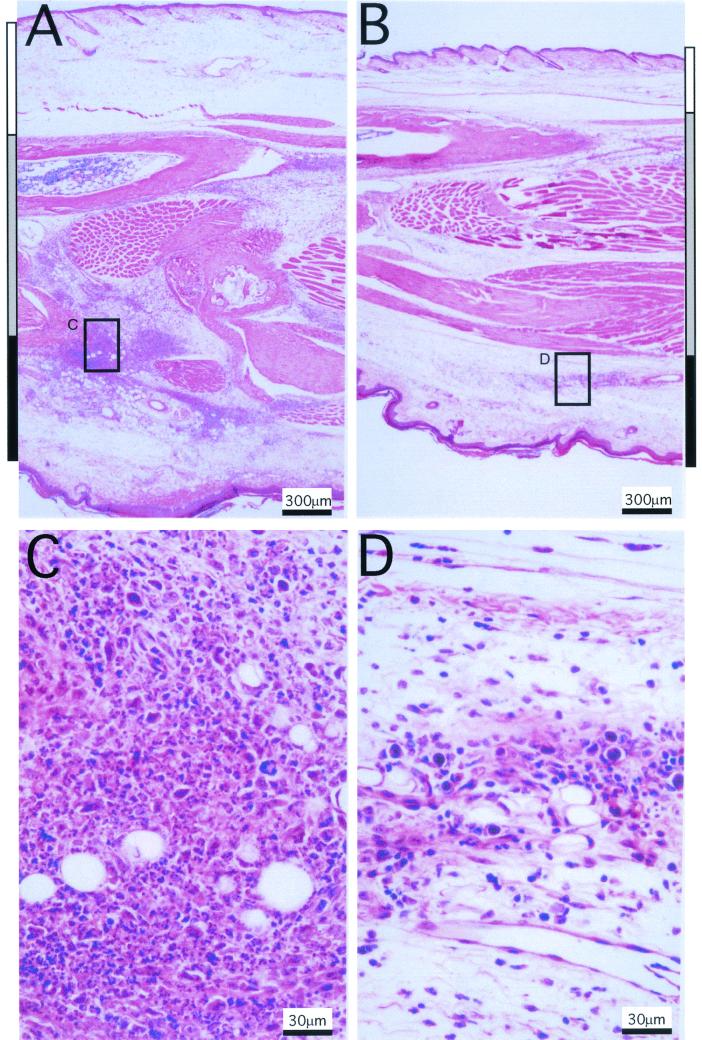

In order to directly investigate cellular infiltrates in response to mck, BALB/c mouse footpads were inoculated with mutant virus RM461 or rescued virus RQ461 (106 PFU). Feet were collected from sacrificed mice at 48 h postinoculation, and midline longitudinal sections were prepared from 10% neutral buffered formalin-fixed (Ex Cal II; Fisher Scientific), paraffin-embedded (Histo Tech, Inc.) blocks. Examination by light microscopy at a low power (×40) revealed substantially larger amounts of both cellularity and edema in mck-expressing virus- than in control virus-infected feet (Fig. 8). All areas of inoculated feet (dorsal, internal, and ventral) appeared less inflamed following infection with mutant virus RM461 (Fig. 8B) than following infection with mck-expressing control virus RQ461 (Fig. 8A). The differences in foot thickness measured grossly using calipers (Fig. 7) correlated with the histopathological findings and appeared to result from increases in both cellularity and edema (Fig. 8A and B). In a pattern that was readily appreciated at a low power, the expression of mck correlated with a much more intense local inflammatory response in the regions closest to the inoculation sites. At a higher power (×400), differences in cellular infiltrates with increased neutrophils were readily apparent, and there was more necrosis in tissues from mck-expressing virus-infected mice (Fig. 8C) than in those from mutant virus-infected mice (Fig. 8D). All of these inflammatory changes were due to the presence of virus in the inoculum, because injection of culture medium alone failed to induce any response over that seen in sham (medium)-inoculated controls (data not shown). These observations suggested that the expression of mck altered and intensified the innate inflammatory response to virus infection.

FIG. 8.

Inflammatory responses induced by RM461 and RQ461 following footpad inoculation. Tissues were harvested from an inoculated mouse foot 48 h after inoculation with RQ461 or RM461 (106 PFU in 3 μl of growth medium), formalin fixed, and decalcified; after embedding in paraffin, 5-μm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (A) RQ461. (B) RM461. (C) RQ461. (D) RM461. The dorsal, internal, and ventral areas are denoted by white, grey, and black bars, respectively, on the sides of panels A and B. Areas boxed in panels A and B are magnified in panels C and D, respectively.

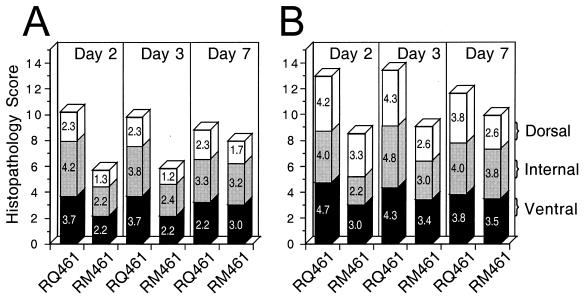

To determine how the host inflammatory response was modulated by the expression of mck during infection, histological sections from groups of mice were analyzed. Sections were evaluated semiquantitively at 2, 3, and 7 days postinoculation, and mean scores for the intensity of cellular infiltration and edema in the dorsal, internal, and ventral areas of midline longitudinal sections (5 μm) of infected feet were assigned numerical values: minimal, 1; mild, 2; moderate, 3; marked, 4; and severe, 5 (Fig 9). Dorsal, internal, and ventral regions of the feet were evaluated by light microscopy at low-power magnification for levels of edema and cellularity and at high-power magnification for changes in cell type and necrosis. When separate areas of the feet were scored for cellularity and edema, the ventral and internal regions exhibited greater differences at day 2 or 3 than did the dorsal region, although mutant virus infection consistently induced a less intense response than wild-type virus infection in all of these areas. Overall, these differences reflected the extent of swelling measured using calipers (Fig. 7). The total levels of cellularity (Fig. 9A) and edema (Fig. 9B) were depicted by combining the mean scores of individual areas. These levels peaked at day 2 or 3 following inoculation with wild-type virus and were markedly lower in mutant virus-infected tissues. Mononuclear cell infiltrates increased and neutrophil infiltrates decreased at between days 3 and 7 for both viruses (data not shown), consistent with the transition from an innate to an adaptive immune response over this time (27). When the intensity of cellularity or edema in separate areas was evaluated (Fig. 9A and B), results continued to show a marked difference in mutant-infected and control tissues. On day 2 or 3 postinoculation, levels of cellularity during infection with mutant virus were approximately 60% the levels seen with wild-type virus, with differences being most marked in the ventral and internal areas. On day 2 or 3 postinoculation, levels of edema during infection with mutant virus were variable (55 to 79% the levels of the wild type) but were consistently lower than the levels seen with wild-type virus. Together, these results show that mck expression correlated with a more intense inflammatory response in the infected tissues at times when the innate response predominated. It seems likely that mck acts to profoundly alter and intensify the early antiviral inflammatory response, albeit in a manner that is apparently independent of the effectiveness of that response. Quite remarkably, the profound increase in the inflammatory response induced by mck-expressing viruses does not result in a greater clearance of infection (Fig. 5).

FIG. 9.

Histopathological evaluation of edema and cellularity following footpad inoculation. Groups of five mice were inoculated in a single footpad with either RM461 or RQ461 as described in the legend to Fig. 8, and foot sections were collected for analysis at days 2, 3, and 7 postinoculation. Sections from each foot were evaluated for inflammatory changes at low-power magnification by light microscopy (×40) and assigned numerical values (see the text) for levels of cellularity (A) and edema (B). Bars correspond to the mean values for the dorsal (open), internal (grey), and ventral (black) areas and are depicted to appreciate the score for an area as well as a total score (maximum of 15) that incorporates the evaluation of all three areas.

We have shown that the expression of MCK-2 during acute infection in mice contributes to an increase in the inflammatory response at the footpad site of inoculation as well as to higher peak levels of viremia and more efficient dissemination to salivary glands. Efficient mck-dependent dissemination is not affected by the capacity of the host to mount an adaptive immune response (8, 55) but appears to interface with the innate immune response over the first few days of infection. Fleming et al. (19) observed approximately twofold lower levels of inflammation in the liver at 2 days after i.p. inoculation with mck mutant viruses; however, this result does not reflect differences in the levels of inflammation in the peritoneal cavity, which are similar for mck mutant and control viruses (N. Saederup, unpublished observations).

Recombinant viruses carrying specific mutations disrupting the conserved CC chemokine motif within m131 provide the strongest evidence that inflammation at the footpad inoculation site is under the control of MCK-2 and that the intensity of the local inflammatory response influences the level of viremia that precedes dissemination to the salivary glands. Consistent with a proposed role as a secreted chemokine, the requirement for MCK-2 can be complemented by coinoculating an mck-expressing virus together with a mutant virus. Although we cannot discount a direct immunomodulatory role for MCK-2, we believe that the major impact of mck is to recruit mononuclear leukocytes that disseminate virus. Many other immunomodulatory viral gene products probably contribute to altering the effectiveness of innate and adaptive immune responses (reviewed in references 29, 38, 52, and 53). mck function therefore appears to be focused on the recruitment of cells that facilitate dissemination to the salivary glands during acute infection. With a pirated function used to increase dissemination, mck appears suited to the needs of a virus that gains access to the salivary glands in order to be shed into saliva and transmitted to new hosts (24).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grants AI30363 and AI33852 (to E.S.M.) as well as PHS training grant T32 GM07328 (to N.S.) and PHS Clinical Scientist Career Development Award K08 AI 01638 (to S.A.A.).

We thank Jing Huang for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn K, Angulo A, Ghazal P, Peterson P A, Yang Y, Fruh K. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits antigen presentation by a sequential multistep process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10990–10995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam R, Kumar D, Anderson-Walters D, Forsythe P A. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha and monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 elicit immediate and late cutaneous reactions and activate murine mast cells in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:1298–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baggiolini M, Loetscher P. Chemokines in inflammation and immunity. Immunol Today. 2000;21:418–420. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bale J F, Jr, O'Neil M E. Detection of murine cytomegalovirus DNA in circulating leukocytes harvested during acute infection of mice. J Virol. 1989;63:2667–2673. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2667-2673.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boshoff C, Endo Y, Collins P D, Takeuchi Y, Reeves J D, Schweickart V L, Siani M A, Sasaki T, Williams T J, Gray P W, Moore P S, Chang Y, Weiss R A. Angiogenic and HIV-inhibitory functions of KSHV-encoded chemokines. Science. 1997;278:290–294. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher E C, Williams M, Youngman K, Rott L, Briskin M. Lymphocyte trafficking and regional immunity. Adv Immunol. 1999;72:209–253. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardin R D, Boname J M, Abenes G B, Jennings S A, Mocarski E S. Reactivation of murine cytomegalovirus from latency. In: Michelson S, Plotkin S A, editors. Multidisciplinary approaches to understanding cytomegalovirus disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark-Lewis I, Dewald B, Loetscher M, Moser B, Baggiolini M. Structural requirements for interleukin-8 function identified by design of analogs and CXC chemokine hybrids. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16075–16081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark-Lewis I, Kim K S, Rajarathnam K, Gong J H, Dewald B, Moser B, Baggiolini M, Sykes B D. Structure-activity relationships of chemokines. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:703–711. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins P D, Jose P J, Williams T J. The sequential generation of neutrophil chemoattractant proteins in acute inflammation in the rabbit in vivo. Relationship between C5a and proteins with the characteristics of IL-8/neutrophil-activating protein 1. J Immunol. 1991;146:677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins T M, Quirk M R, Jordan M C. Biphasic viremia and viral gene expression in leukocytes during acute cytomegalovirus infection of mice. J Virol. 1994;68:6305–6311. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6305-6311.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dairaghi D J, Fan R A, McMaster B E, Hanley M R, Schall T J. HHV8-encoded vMIP-I selectively engages chemokine receptor CCR8. Agonist and antagonist profiles of viral chemokines. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21569–21574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dairaghi D J, Greaves D R, Schall T J. Abduction of chemokine elements by herpesviruses. Semin Virol. 1998;8:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damon I, Murphy P M, Moss B. Broad spectrum chemokine antagonistic activity of a human poxvirus chemokine homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6403–6407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endres M J, Garlisi C G, Xiao H, Shan L, Hedrick J A. The Kaposi's sarcoma-related herpesvirus (KSHV)-encoded chemokine vMIP-I is a specific agonist for the CC chemokine receptor (CCR)8. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1993–1998. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell H E, Vally H, Lynch D M, Fleming P, Shellam G R, Scalzo A A, Davis-Poynter N J. Inhibition of natural killer cells by a cytomegalovirus MHC class I homologue in vivo. Nature. 1997;386:510–514. doi: 10.1038/386510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1984;137:266–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming P, Davis-Poynter N, Degli-Esposti M, Densley E, Papadimitriou J, Shellam G, Farrell H. The murine cytomegalovirus chemokine homolog, m131/129, is a determinant of viral pathogenicity. J Virol. 1999;73:6800–6809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6800-6809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao J L, Murphy P M. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerna G, Zipeto D, Percivalle E, Parea M, Revello M G, Maccario R, Peri G, Milanesi G. Human cytomegalovirus infection of the major leukocyte subpopulations and evidence for initial viral replication in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from viremic patients. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1236–1244. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hengel H, Brune W, Koszinowski U H. Immune evasion by cytomegalovirus–survival strategies of a highly adapted opportunist. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:190–197. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hengel H, Reusch U, Gutermann A, Ziegler H, Jonjic S, Lucin P, Koszinowski U H. Cytomegaloviral control of MHC class I function in the mouse. Immunol Rev. 1999;168:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho M. Cytomegalovirus: biology and infection. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1991. pp. 327–353. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones T R, Sun L. Human cytomegalovirus US2 destabilizes major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J Virol. 1997;71:2970–2979. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2970-2979.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kledal T N, Rosenkilde M M, Coulin F, Simmons G, Johnsen A H, Alouani S, Power C A, Luttichau H R, Gerstoft J, Clapham P R, Clark-Lewis I, Wells T N C, Schwartz T W. A broad-spectrum chemokine antagonist encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Science. 1997;277:1656–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koszinowski U H, del Val M, Reddehase M J. Cellular and molecular basis of the protective immune response to cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:189–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krathwohl M D, Hromas R, Brown D R, Broxmeyer H E, Fife K H. Functional characterization of the CC chemokine-like molecules encoded by molluscum contagiosum virus types 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9875–9880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lalani A S, Barrett J W, McFadden G. Modulating chemokines: more lessons from viruses. Immunol Today. 2000;21:100–106. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01556-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee L F, Wu P, Sui D, Ren D, Kamil J, Kung H J, Witter R L. The complete unique long sequence and the overall genomic organization of the GA strain of Marek's disease virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6091–6096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong C C, Chapman T L, Bjorkman P J, Formankova D, Mocarski E S, Phillips J H, Lanier L L. Modulation of natural killer cell cytotoxicity in human cytomegalovirus infection: the role of endogenous class I major histocompatibility complex and a viral class I homolog. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1681–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y-C. Ph.D. thesis. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J L, Lin S F, Xia L, Brunovskis P, Li D, Davidson I, Lee L F, Kung H J. MEQ and V-IL8: cellular genes in disguise? Acta Virol. 1999;43:94–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loetscher P, Seitz M, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Activation of NK cells by CC chemokines. Chemotaxis, Ca2+ mobilization, and enzyme release. J Immunol. 1996;156:322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacDonald M R, Burney M W, Resnick S B, Virgin H I. Spliced mRNA encoding the murine cytomegalovirus chemokine homolog predicts a beta chemokine of novel structure. J Virol. 1999;73:3682–3691. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3682-3691.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald M R, Li X Y, Virgin H W., IV Late expression of a beta chemokine homolog by murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1997;71:1671–1678. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1671-1678.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manning W C, Stoddart C A, Lagenaur L A, Abenes G B, Mocarski E S. Cytomegalovirus determinant of replication in salivary glands. J Virol. 1992;66:3794–3802. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3794-3802.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFadden G, Lalani A, Everett H, Nash P, Xu X. Virus-encoded receptors for cytokines and chemokines. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:359–368. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mocarski E S, Courcelle C T. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication. In: Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2629–2673. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore P S, Boshoff C, Weiss R A, Chang Y. Molecular mimicry of human cytokine and cytokine response pathway genes by KSHV. Science. 1996;274:1739–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neote K, DiGregorio D, Mak J Y, Horuk R, Schall T J. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signaling characteristics of a C-C chemokine receptor. Cell. 1993;72:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pass R F. Cytomegalovirus. In: Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2675–2705. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penfold M E, Dairaghi D J, Duke G M, Saederup N, Mocarski E S, Kemble G W, Schall T J. Cytomegalovirus encodes a potent alpha chemokine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9839–9844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prichard M N, Duke G M, Mocarski E S. Human cytomegalovirus uracil DNA glycosylase is required for the normal temporal regulation of both DNA synthesis and viral replication. J Virol. 1996;70:3018–3025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3018-3025.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajarathnam K, Sykes B D, Dewald B, Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. Disulfide bridges in interleukin-8 probed using non-natural disulfide analogues: dissociation of roles in structure from function. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7653–7658. doi: 10.1021/bi990033v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rawlinson W D, Farrell H E, Barrell B G. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1996;70:8833–8849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8833-8849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reyburn H T, Mandelboim O, Vales-Gomez M, Davis D M, Pazmany L, Strominger J L. The class I MHC homologue of human cytomegalovirus inhibits attack by natural killer cells. Nature. 1997;386:514–517. doi: 10.1038/386514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saederup N, Lin Y C, Dairaghi D J, Schall T J, Mocarski E S. Cytomegalovirus-encoded beta chemokine promotes monocyte-associated viremia in the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10881–10886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sallusto F, Mackay C R, Lanzavecchia A. The role of chemokine receptors in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saltzman R L, Quirk M R, Jordan M C. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection. Molecular analysis of virus and leukocyte interactions in viremia. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:75–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI113313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith G L, Symons J A, Khanna A, Vanderplasschen A, Alcami A. Vaccinia virus immune evasion. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:137–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spriggs M K. One step ahead of the game: viral immunomodulatory molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:101–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stine J T, Wood C, Hill M, Epp A, Raport C J, Schweickart V L, Endo Y, Sasaki T, Simmons G, Boshoff C, Clapham P, Chang Y, Moore P, Gray P W, Chantry D. KSHV-encoded CC chemokine vMIP-III is a CCR4 agonist, stimulates angiogenesis, and selectively chemoattracts TH2 cells. Blood. 2000;95:1151–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoddart C A, Cardin R D, Boname J M, Manning W C, Abenes G B, Mocarski E S. Peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes mediate dissemination of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1994;68:6243–6253. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6243-6253.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Streblow D N, Soderberg-Naucler C, Vieira J, Smith P, Wakabayashi E, Ruchti F, Mattison K, Altschuler Y, Nelson J A. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell. 1999;99:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takebe Y, Seiki M, Fujisawa J, Hoy P, Yokota K, Arai K, Yoshida M, Arai N. SR alpha promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:466–472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taub D D, Ortaldo J R, Turcovski-Corrales S M, Key M L, Longo D L, Murphy W J. Beta chemokines costimulate lymphocyte cytolysis, proliferation, and lymphokine production. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:81–89. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Den Pol A N, Mocarski E, Saederup N, Vieira J, Meier T J. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism, replication, and gene transfer in brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10948–10965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10948.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vieira J, Farrell H E, Rawlinson W D, Mocarski E S. Genes in the HindIII J fragment of the murine cytomegalovirus genome are dispensable for growth in cultured cells: insertion mutagenesis with a lacZ/gpt cassette. J Virol. 1994;68:4837–4846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4837-4846.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiertz E, Hill A, Tortorella D, Ploegh H. Cytomegaloviruses use multiple mechanisms to elude the host immune response. Immunol Lett. 1997;57:213–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson S D, Kuchroo V K, Israel D I, Dorf M E. Expression and characterization of TCA3: a murine inflammatory protein. J Immunol. 1990;145:2745–2750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Witt D P, Lander A D. Differential binding of chemokines to glycosaminoglycan subpopulations. Curr Biol. 1994;4:394–400. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolpe S D, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse D G, Nguyen H T, Moldawer L L, Nathan C F, Lowry S F, Cerami A. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167:570–581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolpe S D, Sherry B, Juers D, Davatelis G, Yurt R W, Cerami A. Identification and characterization of macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:612–616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wuyts A, Van Osselaer N, Haelens A, Samson I, Herdewijn P, Ben-Baruch A, Oppenheim J J, Proost P, Van Damme J. Characterization of synthetic human granulocyte chemotactic protein 2: usage of chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 and in vivo inflammatory properties. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2716–2723. doi: 10.1021/bi961999z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou P, Isegawa Y, Nakano K, Haque M, Horiguchi Y, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 6 open reading frame U83 encodes a functional chemokine. J Virol. 1999;73:5926–5933. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5926-5933.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]