Abstract

This study identifies a region of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) rep gene (nucleotides 190 to 540 of wild-type AAV-2) as a cis-acting Rep-dependent element able to promote the replication of transiently transfected plasmids. This viral element is also shown to be involved in the amplification of integrated sequences in the presence of adenovirus and Rep proteins.

It was previously reported that efficient recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) production using stable rep-cap cell lines correlated with a 100-fold amplification of the AAV-2 genes upon adenovirus infection (3, 9). This phenomenon, which occurred despite the absence of inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) generated extrachromosomal double-stranded DNA molecules harboring the rep-cap genes and required the activity of the adenovirus DNA binding protein, cellular polymerases, and Rep proteins (9). A question that remained unanswered was whether the rep-cap amplification was dependent on the activity of an as-yet-unidentified viral origin of replication present within the viral genome.

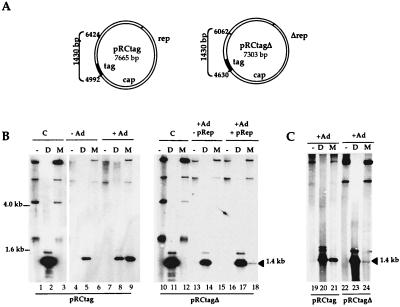

To answer this question, we investigated if a rep-cap-containing plasmid was able to replicate following transient transfection into adenovirus-infected cells. 293 cells were transfected with plasmid pRCtag containing the rep-cap genome with the ITRs deleted, ligated to a 3′ tag sequence, and then mock or adenovirally infected. After DNA extraction, replication was assessed by digestion with DpnI or MboI followed by Southern blot analysis using a tag probe (Fig. 1). Cleavage by DpnI indicates that both strands are methylated in the absence of replication of the transfected DNA; cleavage by MboI occurs only if both strands are unmethylated as a result of two rounds of replication. In the absence of adenovirus, the pRCtag plasmid did not replicate (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, upon adenoviral infection, a fraction of the plasmid DNA was susceptible to MboI digestion (Fig. 1B, lane 9), indicating that some input rep-cap molecules had replicated. After DpnI digestion, high-molecular-weight resistant bands were detected as weak signals, suggesting that pRCtag replication generated products which are heterogenous in size (Fig. 1B, lane 8).

FIG. 1.

In vivo replication analysis of pRCtag and pRCtagΔ plasmids. (A) Circular map of the pRCtag and pRCtagΔ plasmids: the tag located at the 3′ end of the rep-cap genes (hatched area) corresponds to a 404-bp φX174-derived sequence. Plasmid pRCtagΔ differs from pRCtag by a 350-bp deletion in the 5′ portion of the rep gene (nt 190 to 540 of wild-type AAV-2) that removes the entire p5 promoter and the 5′ portion of the rep open reading frame. The positions of the two relevant DpnI-MboI sites are indicated. (B) 293 cells were transfected with the pRCtag or the pRCtagΔ plasmid in the presence (+pRep) or absence (−pRep) of the pRep plasmid, encoding for the Rep proteins under the control of the AAV-2 p5 and p19 promoters, and subsequently infected (+Ad) or not infected (−Ad) with adenovirus. (C) pRCtagΔ and pRCtag were similarly transfected into HeRC32 cells that harbor one integrated copy of the ITR-deleted AAV-2 genome (1). Total genomic DNA was extracted 48 h later, digested with DpnI (D) or MboI (M), and analyzed on a Southern blot by using a tag probe. As a control (lanes 1, 2, and 3), untransfected pRCtag plasmid DNA mixed with 10 μg of total DNA from 293 cells was digested with DpnI or MboI and similarly analyzed using the tag probe. The expected 1,430-bp DpnI-MboI fragment hybridizing to the tag probe is indicated.

To identify the cis element(s) involved in pRCtag replication, we focused on the 5′ portion of the rep gene which includes a Rep binding site (RBS). (nucleotides [nt] 260 to 284 of wild-type AAV-2) and a trs-like motif (nt 287 of wild-type AAV-2) (4, 12). The presence of both elements in the ITRs is known to be essential for wild-type AAV-2 replication (6, 8). A rep-cap plasmid containing a deletion in the 5′ portion of the rep gene (nt 190 to 540 of wild-type AAV-2) was generated (pRCtagΔ) and evaluated as described above. Because pRCtagΔ no longer produced the large Rep proteins (data not shown), its replicative activity was tested with or without a cotransfected pRep plasmid to provide Rep proteins in trans. In adenovirus-infected 293 cells, replication of the pRCtagΔ plasmid was undetectable and only partially restored in the presence of Rep proteins (Fig. 1B, lanes 15 and 18). To exclude the possibility that the low level of pRCtagΔ replication was due to the inefficient transfection of plasmid pRep, the same experiment was reproduced using HeRC32 cells, a stable cell line which expresses the four Rep proteins upon adenovirus infection (1). Again, plasmid pRCtagΔ replicated much less efficiently than plasmid pRCtag (Fig. 1C, lanes 21 and 24). Overall, these data suggested that this 350-nt region of the rep gene behaved as a cis-acting replication element (CARE). The residual level of pRCtagΔ replication observed with 293 and HeRC32 cells could be due either to a recombination event between the plasmid and the cotransfected or endogenous rep sequences or to the presence of additional replication element(s) in the deleted rep-cap genome.

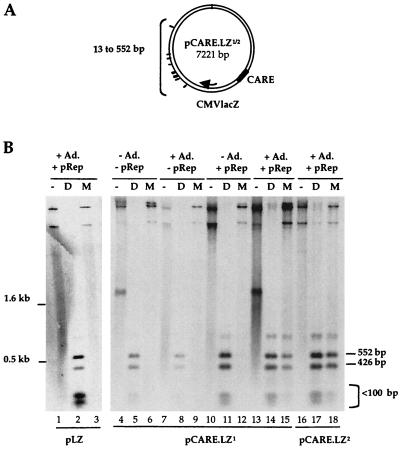

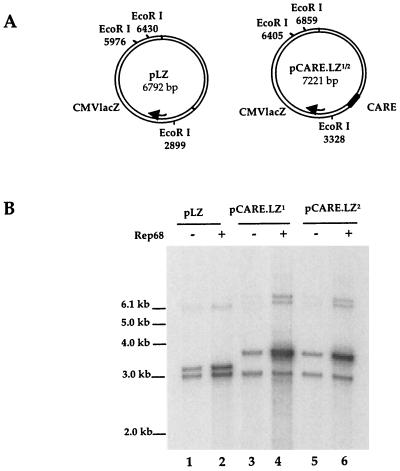

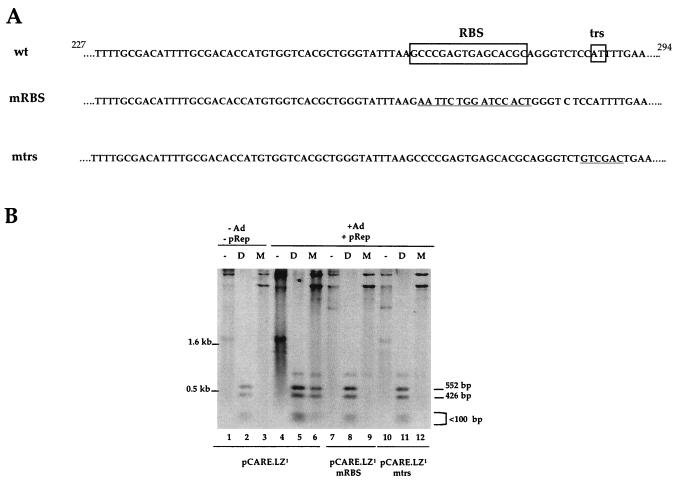

To confirm the role of this viral region in replication, the CARE element was cloned upstream of the lacZ gene in the same or opposite orientation and tested as previously described (Fig. 2). Both pCARE.LZ1 and pCARE.LZ2 plasmids replicated in the presence of Rep proteins and adenovirus (Fig. 2B, lanes 15 and 18), whereas no replication products were detected with a pLZ control plasmid (lanes 1 to 3). The ability of CARE to promote replication in a Rep-dependent manner was further evidenced by two additional experiments. First, a cell-free DNA replication assay was performed, in which EcoRI-digested pLZ, pCARE.LZ1 or pCARE.LZ2 plasmids were incubated with cell extracts from uninfected HeLa cells with or without purified Rep68 protein (7, 13). Despite a significant level of DNA repair which occurred with each DNA template, addition of purified Rep68 resulted in a 13- and 8.5-fold increase in the incorporation of labeled nucleotides only in the upper band containing the CARE sequence, for both plasmids CS pCARE.LZ1 and pCARE.LZ2, respectively (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 6). Second, the RBS and the trs-like elements contained in the p5 region were individually mutated in the pCARE.LZ1 plasmid (Fig. 4A). When tested in a replication assay, mutation of either the RBS or the trs element impaired replication of the pCARE.LZ1 plasmid despite the presence of Rep proteins and adenovirus (Fig. 4B, lanes 9 and 12). The same result was obtained upon transfection in HeRC32 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

In vivo replication assay of pCARE.LZ plasmids. (A) Circular map of pCARE.LZ plasmids. The CARE sequence (190 to 540 bp of wild-type AAV-2), indicated by the hatched area, was introduced upstream of the CMVLacZ cassette either in the same (pCARE.LZ1) or opposite (pCARE.LZ2) orientation. The positions of the relevant DpnI-MboI sites are indicated. (B) 293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmid in the presence or absence of the pRep plasmid and adenovirus infection. DNA was analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 1 by using a lacZ probe. The expected 552-, 426-, and <100-bp DpnI-MboI fragments hybridizing to the lacZ probe are indicated.

FIG. 3.

In vitro replication assay of pCARE.LZ plasmids. (A) Circular map of the pLZ and pCARE.LZ1/2 plasmids. Two major linear species are generated upon EcoRI digestion: one of 3,077 bp that is common to both plasmids and corresponds to the lacZ gene and one of 3,261 and 3,690 bp for pLZ and pCARE.LZ1/2, respectively, that corresponds to the CARE sequence associated with the rest of the plasmid. (B) The EcoRI-digested plasmid DNA was used directly in the in vitro replication assay, so each reaction mixture contained equimolar amounts of the two larger DNA fragments. Replication assays were performed as previously described using a cellular extract from uninfected HeLa cells, supplemented or not with purified Rep68 protein (13).

FIG. 4.

Mutational analysis of CARE element. (A) Sequence of the wild-type (wt) and mutated CARE element between nt 227 and 294 of wild-type AAV-2. The mRBS mutation was previously described by Pereira et al. (5). The mtrs mutation was introduced by changing 6 bp surrounding the trs site described by Wang et al. (12). The presence of each mutation was verified by sequencing. (B) 293 cells were transfected with the indicated construct with or without the pRep plasmid and adenovirus infection. DNA was analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 1 by using a lacZ probe.

Altogether, these findings established the presence of a Rep-dependent replication element between nt 190 and 540 of wild-type AAV-2. These results support and extend the observation made by Tullis and Shenk (10), who demonstrated the presence of a positive cis-acting element between nt 194 and 1882 of AAV-2. Furthermore, CARE features resembled those already described for the chromosome 19 AAVS1 region that also contains an RBS and a trs element (2, 11, 14).

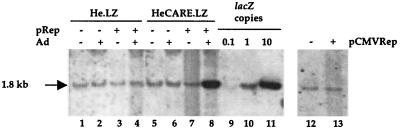

Finally, we wanted to determine if CARE could also induce the amplification of an integrated sequence. A stable cell line (HeCARE.LZ) was obtained by cotransfection of pCARE.LZ1 and the PGK-Neo plasmids into HeLa cells. Control cells (He.LZ) that integrated a lacZ sequence without CARE were obtained similarly. The cells were then tested for the amplification of integrated lacZ sequences. As seen by Southern blot analysis using a lacZ probe, an increase in the lacZ copy number was observed in HeCARE.LZ cells upon adenovirus infection and transfection of plasmid pRep, but not in control He.LZ cells (Fig. 5, lanes 8 and 4). The level of lacZ gene amplification measured in HeCARE.LZ cells was likely underestimated due to the low transfection efficiency of HeLa cells (less than 10%). Importantly, neither adenovirus infection alone nor expression of the rep gene under the control of either the p5 (plasmid pRep) or the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (plasmid pCMVRep) was sufficient to induce lacZ gene amplification in HeCARE.LZ cells (Fig. 5, lanes 6, 7, and 13). These results indicated that integration of CARE can lead to the amplification of an heterologous adjacent sequence and that Rep proteins are necessary together with adenovirus for this phenomenon to occur. This finding suggests that the amplification of an integrated rep-cap genome, which shares this dual requirement (9), is also CARE dependent. As such, the identification of CARE has important implications for the design of stable AAV-2-packaging cells.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of lacZ amplification in stable CARE-lacZ HeLa cells. He.LZ or HeCARE.LZ cells, containing an integrated lacZ or a CARE-lacZ sequence, respectively, were either transfected with a Rep-expressing plasmid (+pRep or +pCMVRep), infected with wild-type adenovirus (+Ad), or both. Total genomic DNA extracted 48 h later was digested with HincII and analyzed on a Southern blot by using a lacZ probe. The position of the expected 1.8-kb lacZ band is indicated. The standard samples with 0.1, 1, and 10 lacZ, copies per cell were obtained by adding 4, 40, and 400 pg of pCARE.LZ plasmid, respectively, to 10 μg of total genomic DNA from noninfected HeLa cells.

Acknowledgments

Pascale Nony and Jacques Tessier contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Vaincre les Maladies Lysosomales (VML), Association Nantaise de Thérapie Génique (ANTG), and the Fondation pour la Thérapie Génique en Pays de la Loire. It was also supported, in part, by NIH grants DK55609 and DK57746 to R.M.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chadeuf G, Fayre D, Tessier J, Provost N, Nony P, Kleinschmidt J, Moullier P, Salvetti A. Efficient recombinant adeno-associated virus production by a stable rep-cap HeLa cell line correlates with adenovirus-induced amplification of the integrated rep-cap genome. J Gene Med. 2000;2:260–268. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200007/08)2:4<260::AID-JGM111>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Voulgaropoulou F, Chen R, Johnson P R, Clark K R. Selective rep-cap gene amplificiation as a mechanism for high-titer recombinant AAV production from stable cell lines. Mol Ther. 2000;2:394–403. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarty D M, Pereira D J, Zolotukhin I, Zhou X, Ryan J H, Muzyczka N. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1994;68:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4988-4997.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira D J, McCarty D M, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein acts as both a repressor and an activator to regulate AAV transcription during a productive infection. J Virol. 1997;71:1079–1088. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1079-1088.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith D H, Ward P, Linden R M. Comparative characterization of Rep proteins from the helper-dependent adeno-associated virus type 2 and the autonomous goose parvovirus. J Virol. 1999;73:2930–2937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2930-2937.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snyder R O, Im D S, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tessier J, Chadeuf G, Nony P, Avet-Loiseau H, Moullier P, Salvetti A. Characterization of adenovirus-induced inverted terminal repeat-independent amplification of integrated adeno-associated virus rep-cap sequences. J Virol. 2001;75:375–383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.375-383.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tullis G E, Shenk T. Efficient replication of adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors: a cis-acting element outside of the terminal repeats and a minimal size. J Virol. 2000;74:11511–11521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11511-11521.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X-S, Srivastava A. A novel terminal resolution-like site in the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome. J Virol. 1997;71:1140–1146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1140-1146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward P, Dean F B, O'Donnell M E, Berns K I. Role of the adenovirus DNA-binding protein in in vitro adeno-associated virus DNA replication. J Virol. 1998;72:420–427. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.420-427.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weitzman M D, Kyostio S R, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]