Abstract

Objectives

Feline enterectomy is commonly performed in referral and general veterinary practice; however, existing studies in the veterinary literature lack significant case numbers to guide clinical decision-making. In addition, no studies have evaluated the use of surgical staplers in cats for this procedure. This study aimed to compare the use of surgical staplers for functional end-to-end anastomosis (SFEEA) with hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) in cats. Additional aims included investigating the feasibility of surgical staplers in cats as well as assessing short- and long-term complications and outcomes.

Methods

The medical records of four referral hospitals were retrospectively searched for cats that had undergone enterectomy between 2003 and 2022. Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data were compared between the SFEEA and EEA groups, with a median long-term follow-up time of 488 days (interquartile range 255–1030).

Results

In total, 54 cats met the inclusion criteria for this study, with 24 undergoing an SFEEA while 30 underwent EEA. There was a significant difference in surgical time between the two groups. The SFEEA group had a mean surgical time 34.3 ± 9.274 mins faster than the EEA group (P <0.001). Unique complications reported for the SFEEA group included haemo abdomen and anastomotic stricture.

Conclusions and relevance

SFEEA should be considered in cats where anaesthetic time should be kept as short as possible, such as patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists scores of 3–4. Stricture at the anastomotic site may be seen in the long term for cats undergoing SFEEA.

Keywords: Enterectomy, surgical stapler, suture, complications

Introduction

Enterectomy is a common procedure to remove diseased intestine for reasons including neoplasia, intestinal strangulation, poor viability secondary to foreign bodies, intussusception and penetrating trauma. 1 In contrast to studies focusing on outcomes in dogs, there are not many contemporary studies assessing the outcomes and risk factors for gastrointestinal surgical techniques in cats.2–8 To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study of a population of cats undergoing enterectomy to report on outcomes and compare closure techniques.

Anastomotic leakage as a complication of enterectomy results in considerable patient mortality, morbidity and cost. 5 The rate of dehiscence is reported in the range of 3–28% in dogs, with mortality rates of up to 85%.5–8 Preoperative factors that have been associated with an increased risk of anastomotic leakage in dogs have been well documented, including preoperative septic peritonitis (PSP), low serum albumin concentration and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status ⩾3, among others.5,7–10 In contrast, after gastrointestinal surgery in cats, dehiscence rates are consistently cited in the literature as being close to zero.2–4,8,11 One recent study of cats undergoing gastrointestinal surgery reported a dehiscence rate of only 0.8% (n = 1/126), listing PSP as a risk factor for mortality. 2

The use of linear stapling devices offers potential benefits when compared with hand-sewn techniques. In dogs, stapling devices are associated with decreased tissue handling, improved blood supply, reduced surgical time and lower dehiscence rates in the presence of PSP.5,12,13 As such, stapling devices are often employed for patients with higher ASA scores and to reduce anaesthesia time, which is associated with lower complication rates, lower costs and reduced staff fatigue.14–16 In cats, the construct time of stapled anastomosis is significantly faster than for hand-sewn anastomotic techniques; however, the effect on duration of surgery has not been reported. 17 The impression of the authors is that surgical staplers are used in cats less often owing to sparse reports in the literature, cost and patient size. In addition, until recently there have been no recommendations on staple height selection for cats. 17

The objective of this paper was to compare the use of surgical staplers for functional end-to-end anastomosis (SFEEA) with hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) in cats. In addition, this study aimed to assess the feasibility of surgical staplers in cats for enterectomy and assess short- and long-term complications and outcomes and identify risk factors. Our hypotheses were as follows: (1) cats undergoing sutured or stapled enterectomy would have similar complications and risk factors to those reported in cats and dogs undergoing gastrointestinal surgery requiring enteric closure;2–9,11,18–27 and (2) SFEEA is faster than EEA in practice, as has been described ex vivo. 17

Materials and methods

This retrospective study used clinical data and records from four referral hospitals in Europe and Australia. The inclusion criteria included cats undergoing enterectomy of the small or large intestine. Cats were excluded if the medical records directly relating to outcomes evaluated in this study were incomplete or there was a lack of follow-up data. Records were examined and information collected in an Excel spreadsheet recording signalment, body weight, breed, days of inappetence before presentation, evidence of pre-existing septic peritonitis, the reason for surgery, presence of concurrent infection, if corticosteroids were administered, if there was evidence of pre-existing inflammatory bowel disease based on clinical signs with a positive response to treatment or intestinal biopsy, and evidence of postoperative sepsis based on previously described criteria. 28 We also collected data on pre-existing comorbidities, such as endocrinopathies or cardiac disease. Preoperative blood work was analysed, including white blood cell count, whether there was a left shift present, platelet count, urea, total protein, albumin, globulin, lactate, packed cell volume (PCV) and postoperative PCV, and total protein. Surgical considerations were also recorded, such as surgical time, anaesthetic time, whether the surgery was an emergency, the resected region of the intestine, whether there were episodes of intraoperative hypotension, ASA score, and whether the surgery was performed by a resident or diplomate.

EEA was performed in all cases using a conventional technique with a 3/0 or 4/0 polydioxanone (PDS) synthetic monofilament. 29 Suture patterns utilised for EEA included simple interrupted, simple continuous, modified Gambee or a combination of these. SFEEA was performed using a GIA DST series, Ethicon linear cutter or Ethicon EndoGIA stapler. Stapler legs were advanced into the lumen oral and aboral of the enterectomy site and closed. Staples were deployed in two rows for the GIA DST series and three rows for the Ethicon Endo GIA staplers. A knife blade cut between the rows of staples creating a stoma, which was closed with the same GIA stapler or a TA stapling device. Crotch stitching was then performed with 3/0 or 4/0 PDS and in some cases the transverse staple line was oversewn.29–31

Normality of data distribution was assessed using a Shapiro–Wilk test and descriptive statistics were performed as appropriate. Data are reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range [IQR]). The effects of EEA vs SFEEA on surgical time were compared using a Student’s t-test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Complications were defined as minor if self-resolving or with medical intervention alone, or major if requiring surgical intervention. Complications were grouped as short term if reported <30 days after surgery and long term if >30 days after surgery. Leakage was recorded as confirmed by necropsy or a subsequent surgery with visualisation of the failed anastomosis.

Long-term follow-up was obtained by veterinarian assessment from subsequent visits to the same hospital; where this information was not available, an owner questionnaire (see Appendix A in the supplementary material) was completed by email or telephone.

Results

A total of 54 cats met the inclusion criteria, with cats in both the SFEEA and EEA groups introduced to the data set at points throughout the study period. There were 24 cats (one entire male, 17 neutered males and six neutered females) in the SFEEA group (median age 3.5 years; IQR 2–11 years; mean weight 4.7 ± 1.5 kg). There were 30 cats (one entire male, three entire females, 15 neutered males and 11 neutered females) in the EEA group (median age 6.5 years; IQR 1–11.8 years; mean weight 4.2 ± 1.7 kg).

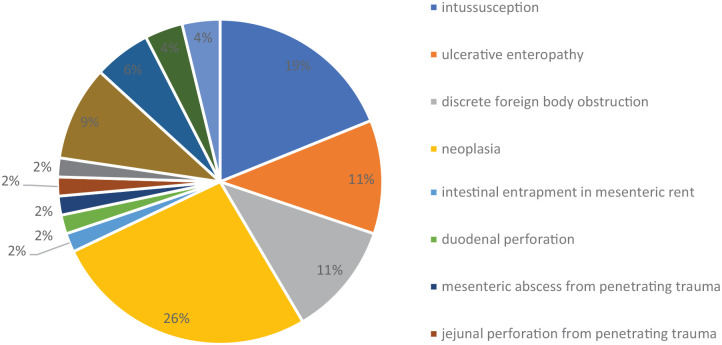

The indications for enterectomy based on surgery reports and histopathology are shown in Figure 1 and include the following: intussusception (n = 10); ulcerative enteropathy (n = 6); discrete foreign body obstruction (n = 6); lymphoma (n = 5); mass with no reported histology results (n = 5); adenocarcinoma (n = 5); megacolon (n = 3); linear foreign body obstruction (n = 2); dehiscence of previous foreign body enterotomy at the referring hospital (n = 2); leiomyosarcoma (n = 2); intestinal entrapment in a mesenteric rent (n = 1); duodenal perforation (n = 1); mesenteric abscess from penetrating trauma (n = 1); jejunal perforation from penetrating trauma (n = 1); lymphosarcoma (n = 2); mast cell tumour and intestinal lymphoma (n = 1); and eosinophilic sclerosis fibroplasia (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Indications for enterectomy based on surgery and histopathology reports

Preoperative blood work was not performed in all cats in the data set. Of the 38 cats in which the white blood cell count was recorded, 3 (7.9%) were leukopenic and 11 (28.9%) had leukocytosis. The median white blood cell count was 14.4 ×109/l (IQR 10.6–20 ×109/l). Of the 45 cats in which albumin was recorded, 20 had hypoalbuminaemia with a mean albumin concentration of 27.8 ± 5.9 g/l. Preoperative PCV was recorded in 45 cats, and of these, four were anaemic; however, this does not take into account patient hydration status at the time of blood collection.

Of the 54 cats in this data series, 50 (93%) survived to discharge with a median duration of hospitalisation of 4 days (IQR 3–6 days). Of the 4 (7%) cats that did not survive to discharge, two were euthanased and two died in hospital. Of the two cats that died in hospital, one never recovered from anaesthesia and the other died of refractory hypotension, with enterectomy site leakage located at the duodenum. This cat originally presented with septic peritonitis after dehiscence of a sutured enterectomy performed at the referring hospital. Septic peritonitis was confirmed with positive Escherichia coli culture on the abdominal fluid. On presentation, the cat was hypoalbuminaemic (18 g/l) and was anaemic (PCV 28%). SFEEA at the site of dehiscence was performed and subsequently dehisced after 64 h (5.3 days). Among the cats that did not survive to discharge, the median duration of hospitalisation was 2.5 days (IQR 2–4 days).

Enterectomy was performed as an emergency in 25 cases and was a scheduled procedure in the remaining 34 cases. In total, 20 cats were classified as ASA 2, 20 as ASA 3 and 14 as ASA 4. There was no association between ASA score and surgical time. Two cats with ASA scores of 3 were euthanased postoperatively after the discovery of neoplastic disease. Both cats that died of surgical complications were classified as ASA grade 4 before surgery.

Of the cats in this data set, 46.2% underwent SFEEA. Staple height selection was based on the surgeon’s preference; cartridges with a 1.5 mm closed staple height were selected in 22 (91.7%) cases and a 1.0 mm closed staple height in two (8.3%) cases. Staple height selection was not related to patient weight, as the cats in which a smaller staple size was selected weighed 3.5 and 6.6 kg, respectively. Stapler type and closed staple height selection, transverse line closure technique and crotch stitch suture selection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stapler brand (type), length of stapler used when recorded, closed staple height selection, oversew technique when used and recorded, and crotch stitch suture selected when recorded

| Case number | Weight (kg) | Resected region | Stapler type | Staple size [closed height (mm)] | Transverse line closure | Transverse line staple height (mm) | Oversewing performed | Crotch stitch placed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.16 | Jejunum to colon | EndoGIA 45 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | No | 4/0 PDS |

| 2 | 6.22 | Ileocaecal junction | GIA DST Series 60 mm | 1 | GIA DST 60 mm | 1 | 3/0 PDS simple continuous | 3/0 PDS |

| 3 | 7.2 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 45 mm | 1.5 | TA30 | 1.5 | 4/0 PDS simple continuous | 4/0 PDS |

| 4 | 3.3 | Ileocaecal junction | GIA DST Series | 1.5 | TA30 | 1.5 | 4/0 PDS simple continuous | 4/0 PDS |

| 5 | 4 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 6 | 4 | Colon | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 7 | 4.4 | Ileocaecal junction | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 8 | 7 | Ileum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 9 | 3.38 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 10 | 5.7 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 11 | 4.4 | Ileocaecal junction | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 12 | 4.6 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 13 | 2.9 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 14 | 3.5 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 15 | 4.4 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | EndoGIA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 16 | 2.2 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | TA60 | 1.5 | no | 4/0 PDS |

| 17 | 3.9 | Jejunum | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1.5 | TA90 | 1.5 | no | 4/0 PDS |

| 18 | 3.5 | Ileocolic junction | EndoGIA 60 mm | 1 | TA90 | 1 | 3/0 PDS simple continuous | 3/0 PDS |

| 19 | 3.8 | Jejunum | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | TA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 20 | 6.9 | Duodenum | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | TA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 21 | 4.4 | Ileum | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | TA | 1.5 | No | 3/0 PDS |

| 22 | 5.4 | Ileocaecal junction | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | Not recorded | Not recorded | Not recorded | Not recorded |

| 23 | 6 | Jejunum | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | TA | 1.5 | 3/0 PDS simple continuous | 3/0 PDS |

| 24 | 7.4 | Jejunum | Ethicon Linear Cutter 55 mm | 1.5 | TA | Not recorded | Not recorded | Not recorded |

PDS = polydioxanone

For the 47 cases that reported surgery time, a two-sample t-test was performed on the surgery time, testing the effect of EEA and SFEEA. The mean surgery time for EEA and SFEEA was 99.21 ± 34.13 mins and 64.87 ± 29.13 mins, respectively. There was a significant difference in the mean surgery times in the EEA and SFEEA groups (P <0.001). The surgery time in the SFEEA group was a mean of 34.4 ± 9.274 mins faster than in the EEA group (95% confidence interval [CI] 15.66–53.02).

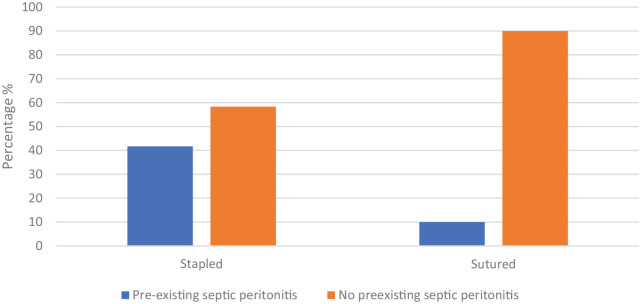

PSP was present in 13 (24%) cases. Of these cases, 10 (77%) underwent SFEEA, while only three (23%) underwent EEA (Figure 2). Veterinarians were >3 times more likely to use a surgical stapler in the presence of pre-existing septic peritonitis.

Figure 2.

Proportions of hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis vs surgical staplers for functional end-to-end anastomosis in cats with and without evidence of septic peritonitis

The overall complication rate after feline enterectomy was 19.2%, with a complication rate after EEA of 14.3% and after SFEEA of 29.2%. Complications are reported in Table 2. Complications relating to the underlying disease process or concurrent illness were excluded. In total, 40 cats were available for long-term follow-up. Minor short-term complications included surgical site infection and seroma. Major short-term complications included haemoabdomen (n = 1), dehiscence (n = 1) and stricture (n = 2). No minor long-term complications were reported; major long-term complications included delayed surgical site infection and stricture.

Table 2.

Complications after feline enterectomy due to the surgical procedure

| Enterectomy technique | Incidence reported | Overall Incidence | Primary operator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical site infection | EEA

SFEEA |

7.1% (n = 2/28)

4.2% (n = 1/24) |

5.8% | Specialist |

| Delayed surgical site infection | EEA

SFEEA |

3.6% (n = 2/28)

0% (n = 0/24) |

1.9% | Specialist |

| Seroma | EEA

SFEEA |

0% (n = 0/28)

4.2% (n = 1/24) |

1.9% | Specialist |

| Haemoabdomen | EEA

SFEEA |

0% (n = 0/28)

4.2% (n = 1/24) |

1.9% | Resident |

| Did not recover from anaesthesia | EEA

SFEEA |

0% (n = 0/28)

4.2% (n = 1/24) |

1.9% | Specialist |

| Dehiscence | EEA

SFEEA |

0% (n = 0/28)

4.2% (n = 1/24) |

1.9% | Specialist and resident |

| Stricture | EEA

SFEEA |

0% (n = 0/28)

8.3% (n = 2/24) |

3.8% | Specialist and resident |

| Total complication rate | 19.2% (n = 10/52) |

Primary operator refers to the level of experience of the surgeon performing the enterectomy. For both cases where stricture and dehiscence occurred, both a specialist and resident performed the enterectomy together. NB: the case of delayed surgical site infection refers to a cat that developed a cellulitis 5 weeks postoperatively on the suture line and required surgical intervention

EEA = hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis; SFEEA = stapler for functional end-to-end anastomosis

Long-term follow-up was obtained in 35 cats (17 SFEEA and 18 EEA) with a median of 488 days (IQR 255–1030 days). All concerns reported by owners at the long-term follow-up were related to the underlying disease process, apart from one cat that underwent two further enterotomies in the jejunum at the SFEEA site due to stricture formation and subsequent foreign body obstruction.

Discussion

The results of this study show that SFEEA is feasible in feline patients and has similar outcomes to EEA. The primary hypothesis is only partially accepted as the low numbers of negative outcomes observed, similar to other feline reports, did not allow the identification of risk factors.2–8,11,18,32,33 The secondary hypothesis, that SFEEA is performed faster than EEA, was accepted. This potentially reduces anaesthesia and surgical times for often critical patients with higher ASA scores.

This is the first study concentrating solely on feline enterectomy, with 93% of cats surviving to discharge. Only one episode of dehiscence was reported in this population, which occurred after an enterectomy that was performed at a primary care hospital. That cat developed septic peritonitis and was referred to a specialist hospital where the subsequent SFEEA dehisced. These results are in agreement with the limited studies that include cats undergoing gastrointestinal surgery and have reported low complication rates, with a reported incidence of dehiscence of 0–1.2%.2–4,8,11,19,20 All but two of these studies included small populations and no studies have yet evaluated the long-term outcomes.2–4,8,11,19,20 This is in contrast to a recent study of large intestinal full-thickness incisions in cats that reported a higher rate of dehiscence of 8.3%, where partial colectomy or colocolic anastomosis were noted to be risk factors for dehiscence. 21 This difference in rates of dehiscence may reflect different properties of the small and large intestine, and a large proportion of these cases was affected by malignancy (68.8%). 21 The aforementioned study did not specify if a surgical stapler or suture was used to perform the enterectomy. 21

The cats that did not survive to discharge were complex cases with multifaceted clinical issues. As a result of the low number of negative outcomes, we could not link any risk factors for dehiscence, as have been established for dogs.5–8,11 PSP was present in 24% of cats in our data set, and of this subset of cats, immediate perioperative period death occurred in 15.4% (n = 2). This is comparable to similar reports in dogs reporting a 22% incidence of PSP. 8 Although case numbers in this study did not allow the determination of statistical significance, these results are consistent with similar data sets of larger numbers reporting low dehiscence rates of <1% in cats undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. 2 This study was able to link PSP with a 6.7 times higher odds of mortality but did not group stapled closure technique specifically in these cases. 2 In dogs with PSP, cases undergoing SFEEA have a rate of dehiscence of 9.7%. This is much lower when compared with EEA, for which dehiscence rates are reported in the range of 21.1–35%.5,8 Cats in our data set with PSP were more likely to undergo SFEEA (77%) than EEA (23%). The rate of dehiscence for cats in our data set undergoing SFEEA was 4.2%, whereas no cats dehisced after EEA. It is possible that the surgeon’s decision was biased by the outcomes of SFEEA reported in dogs.

In the present study, preoperative hypoalbuminaemia was common in cats undergoing enterectomy. Of the cats, 44% were considered hypoalbuminaemic, defined as an albumin <28 g/l. In dogs, low serum albumin has been strongly linked to the development of intestinal dehiscence, 8 while in cats only one study (n = 172) has been able to show a significant relationship between low serum albumin and definite dehiscence; however, in this study, all odds ratios had wide 95% CIs. 11 As a result of the high prevalence of preoperative hypoalbuminemia, and considering that two of the four patients with negative outcomes in our data set had normal albumin levels, we cannot link hypoalbuminemia with perioperative complications including dehiscence.

The feline gastrointestinal tract is commonly sutured with a 3-0 or 4-0 monofilament suture in a simple continuous, modified Gambee or simple interrupted pattern. 29 Also reported is the use of skin staples and, more recently, the use of barbed suture, again with both of these techniques not affecting outcome.22–24 In dogs and cats, 1.5 mm closed staple heights are commonly used in the small intestine, while 2.0 mm closed staple heights are reserved for the stomach. Fixed staple heights mean that if the staples are too small, the staple may fail to incorporate the submucosa and this can result in iatrogenic damage due to compression and local ischaemia.30,33,34 If the staple height is too large, the staple may not form a leakproof seal or close vessels, leading to bleeding. 30 Interspecies variations in intestinal mural thickness warrant consideration when selecting a staple height, which should be selected on the basis of individual patient intestinal thickness. 17 The feline small intestine is 1.43 times as thick as a human intestine and has a similar mural thickness to that of dogs. 17 This data set supports the use of a surgical stapler in cats with a body weight as low as 2.2 kg utilising closed staple heights of 1.5 mm or 1.0 mm. Stapling devices, including the GIA DST series, Ethicon Flex Endo GIA or Ethicon Linear Cutter, can be used with lengths of 45–60 mm with the transverse line closed with the same GIA or a TA stapler. Oversewing the transverse staple line is based on surgeon preference and did not affect the outcome in the cats in this cohort. Crotch stitching was reported for all but two cases where the information was missing from the clinical record. Further studies in cats are warranted to investigate this requirement.

SFEEA in cats was significantly faster by a mean of 34.3 ± 9.274 mins compared with EEA (P <0.001). This is consistent with studies of dogs that report SFEEA to be up to 10 times faster than EEA. 33 The same study noted no difference in leak pressures between EEA and SFEEA in dogs. 33 Shorter anaesthesia times obtained by utilising SFEEA compared with EEA result in a shorter window for potential surgical or anaesthetic complications. Sick patients assessed by higher ASA scores (3–5) before anaesthesia are at a higher risk of anaesthetic death when compared with healthy animals. 35 Urgent and emergency procedures are associated with 17 times the odds of general anaesthetic-related death in cats and dogs regardless of the reason for anaesthesia. 35 In dogs undergoing gastrointestinal surgery, those with ASA >3 were more likely to develop dehiscence than those with lower ASA scores. 27 This is consistent with the results in our data set, with those cats not surviving the perioperative period being of ASA status 3 or 4; however, this was not unique to non-survivors. Of the cats undergoing enterectomy in our data set, 63% were ASA grade 3 or 4 and of higher anaesthetic risk.

The use of skin staples or barbed sutures for feline enteric closure reduces surgical time; however, the disadvantage of the these techniques is stricture formation at the enterectomy site.23,24 This complication has previously been reported in a small number of dogs using a GIA stapler with staples of 1.5 mm closed height as well as in both dogs and cats after sutured side-to-side anastomosis.6,36 Studies assessing intestinal motility after SFEEA are conflicting, but some suggest that reduced transit time may contribute to the lodgement of foreign bodies at this site in dogs.25,37 Two cats in this data set were confirmed to have stricture at the SFEEA site causing mechanical obstruction that required revision surgery. One cat was euthanased 3 days postoperatively owing to early anastomotic stricture and the other cat underwent two additional sutured enterotomies at the same location as the SFEEA site in the long-term follow-up period due to intestinal foreign body obstruction. Anastomotic conformation as well as enteric closure technique may contribute to stricture development; however, further studies in cats are warranted to investigate if there are stenotic changes and alterations to intestinal motility after SFEEA compared with EEA.

Of the cats that had complications occur at the SFEEA site, stricture and dehiscence were reported with the use of the Ethicon Linear Cutter, staples of 1.5 mm closed height and transverse line closure with a TA stapling device with a 1.5 mm closed staple height without oversewing. A crotch stitch was placed with 3/0 PDS in one case of stricture and one case of dehiscence, but was not recorded in the case of stricture occurring twice in the long-term period. No complications associated with the anastomotic site were reported with the use of the GIA DST Series stapler with a 1.5 mm closed staple height with oversewing and crotch augmentation or the EndoGIA stapler with a 1.5 mm closed staple height, with or without oversewing and crotch augmentation. Ex vivo, the use of an EndoGIA stapler with a tri-staple cartridge of 1.2–1.8 mm closed height with or without oversewing and a TA stapler with a 1.5 mm closed staple height has been shown to provide supraphysiological leak pressures. 17 Augmentation by placement of a crotch stitch increases leak pressures in dogs but has not been demonstrated in cats. 38 Further prospective studies evaluating stapling techniques are warranted.

Haemoabdomen developed 24 h postoperatively in one cat after SFEEA with the GIA DST series stapler with a 1 mm closed staple height for the horizontal and transverse staple line with oversewing and crotch stitch augmentation. Exploratory coeliotomy was performed and staple failure was suspected to have resulted in bleeding at the anastomotic site. A previous study has reported staple failure due to malformed staples in the transverse line and suggested that a 1.0 mm closed staple height selection may not have engaged the submucosa, potentially resulting in staple dislodgement. 17 Haemoabdomen has previously been reported in one study of 15 cats undergoing subtotal colectomy utilising a circular stapling device, where two cats developed this complication. 26

The limitations of this study include those related to the retrospective nature of the study design, including incomplete patient records and owner memory bias when completing the questionnaire. Although the sample size is comparable to that in similar canine studies, there were not enough negative outcomes to identify the risk factors for dehiscence or mortality. Owing to the small sample size, the timespan to collect patient data was long, during which time advancements in other aspects of patient care may have influenced the outcomes. Higher complication rates noted for stapled enterectomy may be due to selection bias as these cases were more likely to have concurrent pathology, which may have influenced the outcomes. Future prospective controlled studies with larger case numbers are warranted.

Conclusions

Feline enterectomy performed with sutured EEA or a surgical stapling device is associated with low rates of dehiscence. Mortality is more likely related to health status at the time of surgery or concurrent pathologies. Using a surgical stapler is significantly faster (mean 34.3 ± 9.274 mins; P <0.001) than hand-sewing the enterectomy site, and is associated with a shorter anaesthetic time and therefore a shorter window for potential life-threatening complications in patients already at higher anaesthetic risk. Where available, surgeons should consider using a surgical stapler in cats requiring an enterectomy while being aware of the potential long-term small risk of stricture at the anastomotic site.

Supplemental Material

owner questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Evelyn Hall for her assistance with statistical analysis and data interpretation.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material: The following file is available as supplementary material:

Appendix A: owner questionnaire.

Ethical approval: The work described in this manuscript involved the use of non-experimental (owned or unowned) animals. Established internationally recognised high standards (‘best practice’) of veterinary clinical care for the individual patient were always followed and/or this work involved the use of cadavers. Ethical approval from a committee was therefore not specifically required for publication in JFMS. Although not required, where ethical approval was still obtained, it is stated in the manuscript.

Informed consent: Informed consent (verbal or written) was obtained from the owner or legal custodian of all animal(s) described in this work (experimental or non-experimental animals, including cadavers) for all procedure(s) undertaken (prospective or retrospective studies). No animals or people are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

ORCID iD: Sorcha Costello  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9871-6491

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9871-6491

Benjamin McRae  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3539-1879

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3539-1879

Rachel M Basa  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9599-3054

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9599-3054

References

- 1. Brown DC. Small intestines. In: Slatter DH. (ed). Textbook of small animal surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2003, pp 644–664. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hiebert EC, Barry SL, Sawyere DM, et al. Intestinal dehiscence and mortality in cats undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. J Feline Med Surg 2022; 24: 779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weisman DL, Smeak DD, Birchard SJ, et al. Comparison of a continuous suture pattern with a simple interrupted pattern for enteric closure in dogs and cats: 83 cases (1991–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 1507–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayes G. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies in dogs and cats: a retrospective study of 208 cases. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50: 576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis DJ, Demianiuk RM, Musser J, et al. Influence of preoperative septic peritonitis and anastomotic technique on the dehiscence of enterectomy sites in dogs: a retrospective review of 210 anastomoses. Vet Surg 2018; 47: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DePompeo CM, Bond L, George YE, et al. Intra-abdominal complications following intestinal anastomoses by suture and staple techniques in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018; 253: 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Snowdon KA, Smeak DD, Chiang S. Risk factors for dehiscence of stapled functional end-to-end intestinal anastomoses in dogs: 53 cases (2001–2012). Vet Surg 2016; 45: 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ralphs SC, Jessen CR, Lipowitz AJ. Risk factors for leakage following intestinal anastomosis in dogs and cats: 115 cases (1991–2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 223: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jardel N, Hidalgo A, Leperlier D, et al. One stage functional end-to-end stapled intestinal anastomosis and resection performed by nonexpert surgeons for the treatment of small intestinal obstruction in 30 dogs. Veterinary Surgery 2011; 40: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen LA, Smeak DD. In vitro comparison of leakage pressure and leakage location for various staple line offset configurations in functional end-to-end stapled small intestinal anastomoses of canine tissues. Am J Vet Res 2015; 76: 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swinbourne F, Jeffery N, Tivers MS, et al. The incidence of surgical site dehiscence following full-thickness gastrointestinal biopsy in dogs and cats and associated risk factors. J Small Anim Pract 2017; 58: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller AK, Regier PJ, Collins MC, et al. Performance time and leak pressure of hand-sewn and skin staple intestinal anastomoses and enterotomies in cadaveric cats. Vet Surg 2024; 53: 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duell JR, Thieman Mankin KM, Rochat MC, et al. Frequency of dehiscence in hand-sutured and stapled intestinal anastomoses in dogs. Vet Surg 2016; 45: 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beal MW, Brown DC, Shofer FS. The effects of perioperative hypothermia and the duration of anesthesia on postoperative wound infection rate in clean wounds: a retrospective study. Vet Surg 2000; 29: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smeak DD, Monnet E. Enterectomy. In: Gastrointestinal surgical techniques in small animals. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2020, pp 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng H, Clymer JW, Po-Han Chen B, et al. Prolonged operative duration is associated with complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res 2018; 229: 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanders JE, Regier PJ, Waln M, et al. Gastrointestinal thickness, duration, and leak pressure of five intestinal anastomosis techniques in cats. Vet Surg 2024; 53: 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson T, Beever L, Hall J, et al. Outcome following surgery to treat septic peritonitis in 95 cats in the United Kingdom. J Small Anim Pract 2021; 62: 744–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ullman SL, Pavletic MM, Clark GN. Open intestinal anastomosis with surgical stapling equipment in 24 dogs and cats. Vet Surg 1991; 20: 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith AL, Wilson AP, Hardie RJ, et al. Perioperative complications after full-thickness gastrointestinal surgery in cats with alimentary lymphoma. Vet Surg 2011; 40: 849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lux CN, Roberts S, Grimes JA, et al. Evaluation of short-term risk factors associated with dehiscence and death following full-thickness incisions of the large intestine in cats: 84 cases (1993–2015). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2021; 259: 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwartz Z, Coolman BR. Closure of gastrointestinal incisions using skin staples alone and in combination with suture in 29 cats. J Small Anim Pract 2018; 59: 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benlloch-Gonzalez M, Gomes E, Bouvy B, et al. Long-term prospective evaluation of intestinal anastomosis using stainless steel staples in 14 dogs. Can Vet J 2015; 56: 715–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Williams EA, Monnet E. Clinical outcomes of the use of unidirectional barbed sutures in gastrointestinal surgery for dogs and cats: a retrospective study. Vet Surg 2023; 52: 1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Toyomasu Y, Mochiki E, Ando H, et al. Comparison of postoperative motility in hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis and functional end-to-end anastomosis: an experimental study in conscious dogs. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 2489–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kudisch M, Pavletic MM. Subtotal colectomy with surgical stapling instruments via a trans-cecal approach for treatment of acquired megacolon in cats. Vet Surg 1993; 22: 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gill SS, Buote NJ, Peterson NW, et al. Factors associated with dehiscence and mortality rates following gastrointestinal surgery in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019; 255: 569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Babyak JM, Sharp CR. Epidemiology of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis in cats hospitalized in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2016; 249: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giuffrida MA, Brown DC. The small intestine. In: Tobias K, Spencer J, Peck JN, et al. (eds). Veterinary surgery: small animal expert consult. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2017, pp 1730–1749. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tobias KM. Surgical stapling devices in veterinary medicine: a review. Vet Surg 2007; 36: 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goto T, Kawasaki K, Fujino Y, et al. Evaluation of the mechanical strength and patency of functional end-to-end anastomoses. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 1508–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams JM. Feline gastrointestinal surgery. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mullen KM, Regier PJ, Waln M, et al. Gastrointestinal thickness, duration, and leak pressure of six intestinal anastomoses in dogs. Vet Surg 2020; 49: 1315–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chekan E, Whelan RL. Surgical stapling device–tissue interactions: what surgeons need to know to improve patient outcomes. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014; 7: 305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bille C, Auvigne V, Libermann S, et al. Risk of anaesthetic mortality in dogs and cats: an observational cohort study of 3546 cases. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012; 39: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ciammaichella L, Foglia A, Magno S, et al. Retrospective evaluation of a hand-sewn side-to-side intestinal anastomosis technique in dogs and cats. Open Vet J 2023; 13: 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hocking MP, Carlson RG, Courington KR, et al. Altered motility and bacterial flora after functional end-to-end anastomosis. Surgery 1990; 108: 384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duffy DJ, Chang Y-J, Moore GE. Influence of crotch suture augmentation on leakage pressure and leakage location during functional end-to-end stapled anastomoses in dogs. Vet Surg 2022; 51: 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

owner questionnaire.