Abstract

Background

Pediatric cardiology fellows often deliver serious news to families. Effective clinician-patient communication is the basis of strong therapeutic relationships and improves health outcomes, increases patient adherence, and enhances patient satisfaction. Communication training improves physicians’ communication skills, ability to deliver serious news, and meet the informational and emotional needs of patients and family members. However, there is little data surrounding pediatric cardiology fellows competencies or training in communication skills.

Methods

Pediatric cardiology fellows participated in a 3-hour communication training session. The session used VitalTalk methodology and was facilitated by two VitalTalk facilitators. Fellows spent 1 h learning the skills of delivering serious news and responding to emotion and 2 h in role play with standardized actors followed by a brief group wrap-up activity. Participants took an anonymous, electronic pre- and post-survey and an 8-month follow-up survey via REDCap. Participants were asked about their preparedness and comfort performing certain communication skills and leading challenging conversations specific to pediatric cardiology. Response options used a combination of 0 (low comfort/preparedness) to 100 (high comfort/preparedness) point scales and multiple choice.

Results

9 fellows participated in the training and 100% completed all three surveys. Eight were first-year fellows and 1 was a third-year fellow. Finding the right words, balancing honesty with hope, and clinical and prognostic uncertainty were the top three factors that contributed to making conversations difficult. Following the course, there was a significant increase in fellow preparedness to communicate a new diagnosis of congenital heart disease, discuss poor prognoses, check understanding, and respond to emotion and an increase in fellow comfort responding to emotions. Four fellows reported using the skills from this training course in various clinical settings at 8-month follow up.

Conclusions

Communicating serious news effectively is a skill that can be learned in a sustainable way and is essential in the field of pediatric cardiology. Our study demonstrates that an interactive, VitalTalk course can improve preparedness and comfort to deliver serious news in a cohort of pediatric cardiology trainees. Future studies are needed to evaluate translation of skills to clinical practice and durability of these skills in larger cohorts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06078-7.

Keywords: Communication, Delivering serious news, Fellowship education, Medical education

Introduction

Effective clinician-patient communication is the basis of strong therapeutic relationships and has been shown to improve health outcomes, increase patient adherence to medical recommendations, and enhance patient satisfaction with care [1–8]. Conversely, poor communication may undermine the alliance between patients and families, interfere with delivering effective clinical care, and is often cited as the reason for patient dissatisfaction [4, 5, 8].

Consequently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has made communication a core curricular competency for graduate medical trainees. The ACGME tasks residency and fellowship programs with training effective communicators who can engage in shared decision-making with their patients and families and participate in end-of-life (EOL) discussions and care plans [9].

Effective communication is an essential skill for clinicians in pediatric cardiology. Clinicians must lead conversations disclosing the diagnosis of congenital heart disease (CHD), discussing options for invasive cardiac procedures, supporting families in the setting of prognostic uncertainty, and facilitating EOL care discussions for patients across a wide age range, from fetuses to adults. Numerous studies have highlighted areas for improvement in communication between cardiology clinicians and patients, CHD diagnosis to EOL discussions [10–13]. A recent study revealed discrepancies between parents of children with advanced heart disease and their physicians regarding the adequacy of communication, receipt of conflicting information, and the most effective way for parents to receive information [11]. This study concluded that communication training for physicians caring for children with CHD could be an important intervention to address these challenges.

Communications skills training improves physicians’ global communication skills [14, 15], as well as their ability to deliver serious news [15, 16], respond to patient emotional cues [15, 16], check patient understanding [17, 18], and meet informational and emotional needs of patients and family members [19]. VitalTalk provides an evidence-based methodology to train clinicians in communication skills with seriously ill patients that includes didactic sessions to teach skills, demonstrations of skills to learners, and role-plays with trained actors playing the role of the patient [20, 21]. This methodology is flexible and has been successfully adapted to many different populations of learners including palliative care and gerontology fellows (GeriTalk) [22], surgical residents (SurgTalk) [23], and nephrology fellows (NephroTalk) [24].

Yet despite the essential role of strong communication skills in pediatric cardiology and the recognized effectiveness of communication training, there are limited studies assessing the effectiveness of formalized communication training for pediatric cardiology fellows. Our objective was to adapt VitalTalk methodologies to teach pediatric cardiology fellows how to effectively communicate serious news and respond to patient and family emotions. We hypothesized that a role play-based course, specific to pediatric cardiology trainees, would improve the preparedness and comfort of participating pediatric cardiology fellows in delivering serious news with patients and families.

Materials and methods

This single-arm longitudinal study was conducted at Boston Children’s Hospital from July 2023 to April 2024. The half-day, in-person communication training was delivered during fellow bootcamp, a month at the start of training dedicated to learning the fundamentals of pediatric cardiology prior to starting clinical rotations and patient care.

Course description

The VitalTalk-based course was developed in collaboration with faculty and fellows from the Department of Cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital and from the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care and Pediatric Care at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The role play sessions were facilitated by faculty who completed the VitalTalk Faculty Development Course, each with extensive experience in facilitation and communication course design. Two local actors, both of whom had previously participated in communication training sessions, met with faculty for a 2-hour training session the week before the course.

A 3-hour, interactive course was developed consisting of (1) a brief (20 min) didactic outlining the communication skills of delivering serious news and responding to emotion, (2) a demonstration of the skills by faculty facilitators, (3) role play with experienced actors, and (4) a brief, facilitated group wrap-up activity. Each group consisted of 1 facilitator, 1 actor, and 4 learners. Each learner had the opportunity to participate in at least one role play with an actor. Learners identified a goal for the encounter, had the opportunity to “time out” during the encounter as needed to ask for help, and received feedback from the group on “what was going well.” After identifying a stuck point and brainstorming a response, the learner “replayed” a moment within the communication encounter. The faculty facilitator guided the learner in debriefing the re-winded scenario to identify a learning point for future practice. All learners remained engaged throughout the role plays by observing and recording the encounter through written notes and providing specific, positive feedback during the debrief.

We developed two cases for the simulation experiences that were specific to pediatric cardiology. The first case was a toddler diagnosed with acute viral myocarditis requiring escalation to mechanical circulatory support. The second case was an infant with single ventricle congenital heart disease who required a prolonged inpatient admission for failure to thrive and poor feeding. The objectives of both scenarios were to succinctly deliver a clinical update or “headline” to the parent and subsequently recognize and attend to their emotions that arose. Each case included a short clinical vignette for the fellow learner followed by a detailed character description for the actor portraying the child’s parent/ caregiver. Character descriptions included emotions they might express, personal history of the character, tone of the environment, underlying fears they might have, and an explanation of the clinical scenario for someone without medical training. The scenarios were provided to the actors in advance of the training session and a pre-course rehearsal allowed for exploration of the character and for mutual exchange between course faculty and actors to ensure the objectives of the case and expectations were clear. This training procedure for the actors has been previously described [25].

Evaluation

The training session was evaluated by administering surveys at three points in time immediately prior to the session, immediately following the session to be completed within 2 weeks of the training, and then approximately 8 months after the training. The surveys were modeled after several successful examples in the literature using the VitalTalk methodology [26–28] and were reviewed by experts in palliative care and cardiology for content and face validity.

The surveys were anonymously completed via REDCap. In the first survey (pre-course) (Supplemental Material 1), participants were asked about their prior experience with formal communication training, preparedness and comfort with communication skills, and preparedness and comfort leading challenging conversations specific to pediatric cardiology. In the second survey (post-course) (Supplemental Material 2), participants were again asked about their preparedness and comfort performing certain communication skills, preparedness and comfort leading challenging conversations specific to pediatric cardiology, and reactions to the course. Pre-course and post-course surveys were paired. In the final survey (medium-term follow-up) (Supplemental Material 3), participants were asked about their application of the training course in clinical practice. Response options utilized a combination of 0 (low comfort/preparedness) to 100 (high comfort/preparedness) point scales, multiple choice, and open-ended options.

Survey instruments are available as Supplemental Materials 1-3, and the two clinical cases used for the training are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Statistical analysis

Responses to all surveys and demographic questions were tabulated. We conducted descriptive analysis using both mean and standard deviation (SD) as well as median and interquartile range (IQR). A Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to assess change in fellow preparedness and comfort from the pre-course assessment to the post-course assessment. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

Participant demographics, prior communication training, and comfort with communication

Basic participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Eight first year fellows and one third year fellow participated in the training session. The response rate on all three surveys was 100%. Most fellows characterized their previous training sessions as helpful (mean 74 ± SD 18, 0 = not helpful, 100 = very helpful). All fellows felt that fellows should be allowed to lead the communication during challenging encounters.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Year of Fellowship | |

| 1st year | 8 (89) |

| 3rd year | 1 (11) |

| Previous Formal Communication Training (Y) | |

| Medical student | 8 (89) |

| Resident | 5 (56) |

| Type of Communication Training as Resident | |

| Formal lectures | 4 (80) |

| Role play with other trainees | 4 (80) |

| Standardized actors as patients | 4 (80) |

| Case scenarios | 4 (80) |

| Responsible Group for Communication Training as Resident | |

| Palliative care | 4 (80) |

| General pediatrics | 1 (20) |

| Should Fellows Lead Challenging Communication Encounters? | |

| Yes | 9 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) |

Using a scale from 0 to 100 where 0 is very difficult and 100 is very easy, fellows found that discussions regarding surgical/procedural complications (mean 16 ± SD 15), new diagnosis with a poor prognosis (mean 20 ± SD 14), new diagnosis with significant morbidity (mean 21 ± SD 21), and redirection of care (mean 21 ± SD 17) to be the most challenging. Discussions with the highest scores were those regarding a new diagnosis with good prognosis (mean 69 ± SD 30) and care conferences (mean 53 ± SD 17). The top three factors that most contributed to difficult communication encounters included that it is “hard to find the right words” (67% of respondents), “difficult to balance honesty with hope” (78% of respondents), and uncertainty (78% of respondents).

Comparison of pre-course and post-course comfort and preparedness

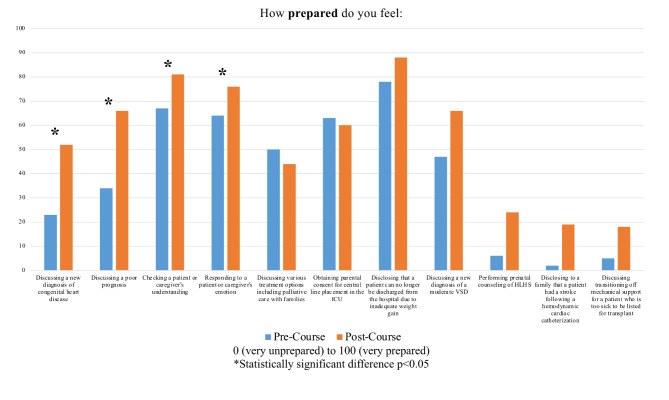

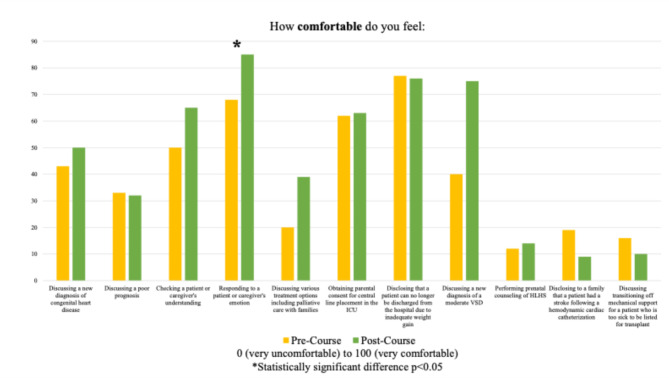

Median preparedness and comfort for almost all queried scenarios increased after the training session (Figs. 1 and 2). The increases were significant in preparedness to discuss a new diagnosis of congenital heart disease, preparedness to discuss a new diagnosis with a poor prognosis, preparedness to check understanding, preparedness to respond to emotion, and comfort with responding to emotion. Median and interquartile values for the pre-course and post-course survey and p-values are shown in Table 2. Fellows agreed that the training was important to their training as a pediatric cardiologist (mean 85 ± SD 17, 0 = strongly disagree, 100 = strongly agree), and that they would use the skills taught in the session in their clinical practice (mean 81 ± SD 18, 0 = strongly disagree, 100 = strongly agree).

Fig. 1.

Change in Median Preparedness Following Session

Fig. 2.

Change in Median Comfort Following Session

Table 2.

Change in median preparedness and comfort following Session

| Question | Pre-Course Median (IQR 25-75%) | Post-Course Median (IQR 25-75%) | Wilcoxon signed-rank p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| How prepared* do you feel: | |||

| Discussing a new diagnosis of congenital heart disease | 23 (1–60) | 52 (31–72) | 0.021 |

| Discussing a poor prognosis | 34 (12–65) | 66 (41–78) | 0.015 |

| Checking a patient or caregiver’s understanding | 67 (55–77) | 81 (65–98) | 0.033 |

| Responding to a patient or caregiver’s emotions | 64 (56–72) | 76 (68–90) | 0.028 |

| Discussing various treatment options including palliative care with families | 50 (29–69) | 44 (29–65) | 0.889 |

| Obtaining parental consent for a central line placement in the ICU | 63 (13–92) | 60 (34–85) | 0.575 |

| Disclosing that a patient can no longer be discharged from the hospital for inadequate weight gain | 78 (56–92) | 88 (73–96) | 0.069 |

| Discussing a new diagnosis of a moderate VSD in an infant | 47 (12–84) | 66 (25–89) | 0.293 |

| Performing prenatal counseling for a diagnosis of HLHS | 6 (0–31) | 24 (5–52) | 0.108 |

| Disclosing to a family that a patient had a stroke following hemodynamic cardiac catheterization | 2 (0–41) | 19 (4–52) | 0.236 |

| Discussing transitioning off mechanical support for a patient who is too sick to be listed for transplant | 5 (2–33) | 18 (0–57) | 0.674 |

| How comfortable^ do you feel: | |||

| Discussing a new diagnosis of congenital heart disease | 43 (16–56) | 50 (29–75) | 0.263 |

| Discussing a poor prognosis | 33 (4–44) | 32 (27–68) | 0.214 |

| Checking a patient or caregiver’s understanding | 50 (67–87) | 65 (82–95) | 0.139 |

| Responding to a patient or caregiver’s emotions | 68 (57–76) | 85 (77–94) | 0.015 |

| Discussing various treatment options including palliative care with families | 20 (13–51) | 39 (21–63) | 0.236 |

| Obtaining parental consent for a central line placement in the ICU | 62 (20–98) | 63 (26–93) | 0.866 |

| Disclosing that a patient can no longer be discharged from the hospital for inadequate weight gain | 77 (37–99) | 76 (67–94) | 0.374 |

| Discussing a new diagnosis of a moderate VSD in an infant | 40 (9–69) | 75 (21–80) | 0.213 |

| Performing prenatal counseling for a diagnosis of HLHS | 12 (0–36) | 14 (0–47) | 0.553 |

| Disclosing to a family that a patient had a stroke following hemodynamic cardiac catheterization | 19 (1–34) | 9 (3–53) | 0.398 |

| Discussing transitioning off mechanical support for a patient who is too sick to be listed for transplant | 16 (1–25) | 10 (3–58) | 0.260 |

*Prepared scale from 0 (very unprepared) to 100 (very prepared)

^Comfort scale from 0 (very uncomfortable) to 100 (very comfortable)

8-month follow-up

A summary of the 8-month follow-up survey questions is shown in Table 3. Four of the 9 (44%) fellows indicated they used the communication skills taught in the course in clinical practice since the training session. All fellows felt more prepared to have serious conversations with their patients after the course. Finally, 56% (5/9) of fellows noted they would handle a past clinical encounter differently following exposure to the communication skills course. Some examples of such clinical encounters included discussing a new diagnosis or clinical deterioration with a family and communicating with colleagues.

Table 3.

Follow-Up survey

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you used your communication training in clinical practice? | |

| Yes | 4 (44) |

| How many times? | |

| Several times | 2 (50) |

| Weekly | 1 (25) |

| Once | 1 (25) |

| In what clinical environment? | |

| Cardiology clinic | 2 (50) |

| Inpatient floor | 3 (75) |

| Cardiac intensive care unit | 2 (50) |

| Cardiology consult service | 3 (75) |

| No | 5 (56) |

| Have you felt more prepared having serious conversations with patients after the training course? | |

| Yes | 9 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| Have you felt more comfortable having serious conversations with patients after the training course? | |

| Yes | 6 (67) |

| No | 3 (33) |

| Would you handle a past clinical encounter differently following the training course? | 5 (56%) |

| Do you think a refresher course would be helpful? | |

| Yes | 8 (89) |

| What format? | |

| Emailed content | 1 (13) |

| Brief didactic during fellowship conference | 7 (88) |

| Role play with standardized patients | 1 (13) |

| Online, self-paced module | 1 (13) |

| No | 1 (11) |

Discussion

Communication is a vital skill for pediatric cardiology providers, who care for seriously ill children and their families. Using validated techniques and methodologies, clinician communication is a skill that can be effectively taught [14–19]. However, few studies have evaluated communication curricula in pediatric cardiology providers [29].

In this single-site, longitudinal assessment of a pediatric cardiology-focused communication training session, we confirmed that a communication skills course using VitalTalk methodology can be effectively tailored to pediatric cardiology trainees, as evidenced by a significant increase in participant preparedness or comfort to discuss new diagnoses of congenital heart disease, check patient and caregiver understanding, and respond to patient and caregiver emotions. Most of our learners had experience with formal communication training sessions in the past, perhaps representing a trend in medical education to recognize the importance of communication training. Despite this prior experience, learners still benefited from the course, suggesting that communication is a longitudinal skill that requires contextualization as learners progress through their training.

This study builds on previous evaluation of a similar curriculum in pediatric cardiology fellows [29] by identifying the types of conversations by which fellows feel most challenged. These included conversations that center on poor prognosis and significant morbidity. Future training with pediatric cardiology trainees should perhaps be tailored to focus on these difficult encounters.

Leading challenging conversations may be inherently uncomfortable or difficult, even for expert communicators, and a single skills session would not be expected to completely prepare learners or to make them completely comfortable with these scenarios. Rather, we chose to focus on interval growth, and employed a more granular 100-point visual analog scale to detect changes that may not have been evident using a standard 5-point Likert scale [30, 31]. While a positive change in self-perception was identified, it should be noted that the values indicated on the scales themselves are somewhat more difficult to interpret, underscoring the importance of alternative measures of applicability and behavioral change as assessed in our follow-up surveys.

Pediatric cardiologists have the unique responsibility of engaging with patients and families in many different settings including inpatient, outpatient, pre- and post-procedural, and pre- and post-surgical settings. Our study demonstrates that the skills learned from the course have been actively applied in all these patient environments.

Our study also highlights some of the challenges with sustaining communication skills. Only 4 of the 9 fellows reported using the skills taught in their training. However, many more felt improved comfort at medium-term follow up and almost all fellows felt a refresher course would be helpful. While this relies on self-reported outcomes and fellows may not remember using skills taught in this course, it raises the concern that further work is required to reinforce the skills taught in the communication course. Therefore, future directions could include training all members of the care team in this methodology to foster a shared language and approach or offering refresher sessions to remind learners of their new skills. Direct faculty observation, rather than self-report, could also assist in more accurate assessment of skill utilization and competency.

Our study has several other important limitations in addition to reliance on self-reported outcomes of comfort and preparedness as well as self-reported behavior change. The small sample size may limit the ability to generalize these findings to other populations. In review of the literature, no standardized assessment tool existed to evaluate the impact of this course. Therefore, we developed a survey tool like those used in other VitalTalk courses. Given limited time and learner experience, our course taught the first half of the VitalTalk curriculum focusing on effectively sharing difficult news, and we did not cover the “REMAP” tool that assists with addressing goals of care. Exploring patient values and preferences is an important component of skilled communication, and the authors plan to incorporate this material in a follow up course later in fellowship training. However, this could explain why learners were not more comfortable with certain skills like discussing end-of-life care on the post-course survey. Finally, our participants were primarily first year fellows who had very little pediatric cardiology training prior to the session. While little clinical knowledge of pediatric cardiology was required to participate in the course, this could have contributed to starting pre-course values being lower than if fellows with more cardiology experience also participated.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates the feasibility of adapting and implementing a communication curriculum with pediatric cardiology trainees and that communication skills are then utilized in the diverse patient encounters required in pediatric cardiology. Future studies will be needed to assess these findings in larger cohorts of learners and the impact these trainings have on family perception of provider communication.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- ACGME

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- CHD

Congenital heart disease

- EOL

End-of-life

- IQR

Interquartile range

- SD

Standard deviation

Author contributions

LC, CT, EB, and CR conceptualized the evaluation. LC, CT, EB, MI, AF, JS, AL, CR were involved in training course development. AF, JS, and AL taught the training course. LC collected data and was involved in quantitative analysis. LC, CT, EB, MI, AF, JS, AL, CR were involved in writing, revising, and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was partially supported by grants from the Joseph Middlemiss Foundation and the Dorothy & Howard Dulman Fund.

Data availability

Data collected during this study is available upon request by reaching out to Lauren Crafts (lauren.crafts@cardio.chboston.org). Materials used for the VitalTalk session are also available upon request.

Declarations

Clinical trial number

Not applicable as this was not a clinical trial.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval was obtained from the Boston Children’s Hospital IRB.

Consent for publication

The authors listed have all provided consent for this study to be published in its current state. There are no identifying images or other personal or clinical details of participants presented that compromise anonymity.

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing interests or relevant financial disclosures.

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting, May 2-6, 2024, Toronto, Canada.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649–57. 10.1542/peds.2005-0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer EC, Sellers DE, Browning DM, McGuffie K, Solomon MZ, Truog RD. Difficult conversations: improving communication skills and relational abilities in health care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(3):352–9. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181a3183a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14–9. 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies B, Connaughty S. Pediatric End-of-life care: lessons learned from parents. JONA J Nurs Adm. 2002;32(1). https://journals.lww.com/jonajournal/Fulltext/2002/01000/Pediatric_End_of_life_Care__Lessons_Learned_From.1.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3044–9. 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Rubenfeld GD. The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N26-33. 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction*. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7). https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/Fulltext/2004/07000/Family_satisfaction_with_family_conferences_about.5.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ravitz P, Lancee WJ, Lawson A, et al. Improving physician-patient communication through coaching of simulated encounters. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Resid Train Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(2):87–93. 10.1176/appi.ap.11070138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross RD, Brook M, Koenig P, et al. 2015 SPCTPD/ACC/AAP/AHA Training Guidelines for Pediatric Cardiology Fellowship Programs (revision of the 2005 Training guidelines for Pediatric Cardiology Fellowship Programs): introduction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(6):672–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morell E, Miller MK, Lu M, et al. Parent and physician understanding of prognosis in hospitalized children with advanced heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(2):1–11. 10.1161/JAHA.120.018488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MK, Blume ED, Samsel C, Elia E, Brown DW, Morell E. Parent-provider communication in hospitalized children with Advanced Heart Disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2022;43(8):1761–9. 10.1007/s00246-022-02913-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto NM, Patel A, Delaney RK et al. Provider insights on shared decision-making with families affected by CHD. Cardiol Young. Published online 2021. 10.1017/S1047951121004406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Arya B, Glickstein JS, Levasseur SM, Williams IA. Parents of children with congenital heart disease prefer more information than cardiologists provide. Congenit Heart Dis. 2013;8(1):78–85. 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00706.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goelz T, Wuensch A, Stubenrauch S, et al. Specific training program improves oncologists’ palliative care communication skills in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3402–7. 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander SC, Keitz SA, Sloane R, Tulsky JA. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents’ communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):1008–12. 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242580.83851.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453–60. 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159–66. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibon A-S, Merckaert I, Liénard A, et al. Is it possible to improve radiotherapy team members’ communication skills? A randomized study assessing the efficacy of a 38-h communication skills training program. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2013;109(1):170–7. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan AM, Rock LK, Gadmer NM, Norwich DE, Schwartzstein RM. The impact of Resident Training on communication with families in the Intensive Care Unit. Resident and Family outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(4):512–21. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-495OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Barley GE, Pea RD, et al. Faculty development to change the paradigm of communication skills teaching in oncology. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VitalTalk. Accessed May 9, 2024. www.vitaltalk.org.

- 22.Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, Goldberg GR, Lim BB, Litrivis E, et al. Geritalk: communication skills training for geriatric and palliative medicine fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman NL, Berlin A, Fischkoff K, Lee-Kong SA, Blinderman CD, Nakagawa S. Annual Structured Communication Skills Training for Surgery Residents. J Surg Res [Internet]. 2023;281:314–20. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022480422005868 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Cohen RA, Bursic A, Chan E, Norman MK, Arnold RM, Schell JO. NephroTalk Multimodal Conservative Care Curriculum for Nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(6):972–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton AJ, Greco L, Airaldi R, Tulsky JA. Development of an Actor Rehearsal Guide for Communication Skills Courses. BMJ Support & Palliat Care [Internet]. 2024;spcare-2023-004509.Available from: http://spcare.bmj.com/content/early/2024/01/09/spcare-2023-004509.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.File W, Bylund CL, Kesselheim J, Leonard D, Leavey P. Do pediatric hematology/oncology (PHO) fellows receive communication training? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(3):502–6. 10.1002/pbc.24742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold RM, Back AL, Barnato AE, Prendergast TJ, Emlet LL, Karpov I et al. The Critical Care Communication project: Improving fellows’ communication skills. J Crit Care [Internet]. 2015;30(2):250–4. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nakagawa S, Fischkoff K, Berlin A, Arnell TD, Blinderman CD. Communication Skills Training for General Surgery Residents. J Surg Educ [Internet]. 2019;76(5):1223–30. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S193172041830833X [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Das N, Brown A, Harris TH. Delivering Serious News in Pediatric Cardiology–A Pilot Program. Pediatr Cardiol [Internet]. 2024;(0123456789). 10.1007/s00246-024-03440-w [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Funke F, Reips UD. Why semantic differentials in web-based Research should be made from Visual Analogue scales and not from 5-Point scales. Field Methods. 2012;24(3):310–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung YT, Wu JS. The visual analogue scale for rating, ranking and Paired-Comparison (VAS-RRP): a new technique for psychological measurement. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(4):1694–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data collected during this study is available upon request by reaching out to Lauren Crafts (lauren.crafts@cardio.chboston.org). Materials used for the VitalTalk session are also available upon request.