Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an age-related, threatening neurodegenerative disorder with no reliable treatment till date. Identification of specific and reliable biomarker is a major challenge for disease diagnosis and designing effective therapeutic strategy against it. PD pathology at molecular level involves abnormal expression and function of several proteins, including alpha-synuclein. These proteins affect the normal functioning of neurons through various post-translational modifications and interaction with other cellular components. The role of protein anomalies during PD pathogenesis can be better understood by the application of proteomics approach. A number of proteomic studies conducted on brain tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid of PD patients have identified a wide array of protein alterations underlying disease pathogenesis. However, these studies are limited by the types of brain regions or biofluids utilized in the research. For a complete understanding of PD mechanism and discovery of reliable protein biomarkers, it is essential to analyze the proteome of different PD-associated brain regions and easily accessible biofluids such as saliva and urine. The present review summarizes the major advances in the field of PD research in humans utilizing proteomic techniques. Moreover, potential samples for proteomic analysis and limitations associated with the analyses of different types of samples have also been discussed.

Keywords: Biomarker, Human, Parkinson’s disease, Proteomics

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an age-related chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disorder with no reliable treatment till date. The disease is mainly characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta region of the midbrain, reduced dopamine level in the striatum, and the formation of intracytoplasmic alpha (α)-synuclein protein aggregates, known as Lewy bodies (LBs). Major motor symptoms of disease are resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia/akinesia, and postural instability. Various non-motor symptoms such as dementia, depression, sleep disturbance, anxiety, dysphagia, and constipation can appear in the PD patients during the early stages and can be aggravated with advancement of disease (Chaudhuri et al. 2006). Three primary causative factors of PD are age, environmental factors, and genetic predisposition (Dauer and Przedborski 2003). Incidence of disease occurrence increases with age with a frequency of 1% for those over the age of 60 years to 4% after 80 years. The environmental factors such as pesticide usage and heavy metal exposure have been found to be associated with increased risk of PD (Yadav et al. 2012). Familial PD caused by mutations in the genes encoding α-synuclein (SNCA), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1), and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) exhibits autosomal dominant inheritance while mutations in the genes encoding Parkin, PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and DJ-1 exhibit autosomal-recessive pattern of inheritance (Gasser 2007).

PD pathology progresses through six distinct stages with the participation of different brain regions during each stage (Braak et al. 2003). Stage 1 and 2 involve mainly dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve and locus coeruleus, stage 3 and 4 include brain stem and substantia nigra regions of the midbrain, and in final stages 5 and 6, pathology reaches to cortical area along with the aggravation of the damage occurred during the previous stages. Each stage is marked by the development of characteristic inclusion bodies in the form of thread-like Lewy neurites (LNs) within cellular processes and granular Lewy bodies (LBs) aggregates in the cell body of the affected neurons (Braak et al. 2003, 2004). Clinical diagnosis of PD is difficult at early stages due to unavailability of any reliable biomarker or diagnostic test for the disease. Physical examination of the motor symptoms is useful for PD diagnosis, but these symptoms are visible in patients who have already lost around 70% of dopaminergic neurons (Breen et al. 2011). Early diagnosis of PD by using specific biomarker is an utmost requirement in order to design therapeutic strategy for this debilitating disease.

PD is associated with a complex disease mechanism characterized by pathological expression and function of a number of proteins related to oxidative stress, inflammation, and ubiquitin proteasomal system (UPS) pathways (Licker et al. 2009). The proteotoxic stress due to the accumulation of misfolded or abnormal α-synuclein protein aggregates in PD is associated with impaired lysosomal and proteasomal clearance mechanisms causing further protein accumulation, disruption of cellular processes, and ultimately neuronal death (Olanow and McNaught 2011). This indicates the crucial role of protein homeostasis in PD pathology. Proteomics is the study of proteome of an organism which helps in quantitative comparison of changes in protein profiles under the influence of different factors such as stress, drug treatment, or as a result of aging and disease (Pienaar et al. 2008; Pienaar et al. 2010). Proteomics of brain tissue and biofluids has widely contributed in understanding the PD pathogenesis by providing evidence of dysfunctional mitochondrial electron transport, protein folding, UPS, and antioxidant defense system in the diseased sample (Dixit et al. 2013; Licker and Burkhard 2014; Kasap et al. 2017). Current advancement of the mass spectrometer in sensitivity, speed, and throughput potentially allows a much higher spatiotemporal resolution of the analysis down to (1) near single cell level to encompass cell type-specific proteome changes, and (2) large-scale screening of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)/blood for biomarker discovery. A number of mass spectrometry (MS) techniques such as electrospray ionization (ESI) MS and laser-based MS have been optimized for single-cell analysis (Yin et al. 2019), while high spatial and mass resolution can be achieved with the help of MS imaging technique (Buchberger et al. 2018). However, the development of systematic and defined therapeutic plan for PD still seems unapproachable as the identified pathways and targets do not represent the complete picture of PD development. This could be due to proteomic studies conducted on PD patients till now have used limited types of samples, and little attention has been paid to other potential brain regions and biofluids. Moreover, a specific biomarker for assessment of PD progression could not be identified yet possibly because of inaccessibility of the sample, failure in correlating it with the disease stage, or poor reproducibility of the results. Therefore, detailed proteomic analyses of PD-affected brain regions and easily accessible biofluids are needed for better understanding of the disease mechanism(s) and identification of biomarkers.

This review aims to summarize the recent advances in proteomics of different brain regions, subcellular structures, and biofluids obtained from PD patients followed by significance of other potential samples for proteomic analysis. The limitations associated with proteomic analysis of different types of samples have also been discussed at the end of this review.

Proteomics of Different Brain Regions Involved in PD Pathology

Locus Coeruleus (LC)

The first appearance of Lewy neurites in early stage and extensive neuronal loss along with norepinephrine depletion at later stages of PD is found in the LC region of the brain (Braak et al. 2003). A single proteomic study conducted on LC region of the PD-affected brain demonstrated protein alterations related to mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, cytoskeleton, and protein folding pathways. The identification of two novel proteins regucalcin (regulates intracellular calcium homeostasis) and kinectin (involved in transport of cellular components) in this study provided new insights into PD pathogenesis (van Dijk et al. 2012). However, further research is needed to validate the role of LC proteins in PD pathogenesis.

Olfactory Bulb

Olfactory dysfunction and smell impairment are considered as early premotor symptoms of PD (Doty 2012). Olfactory bulb atrophy and α-synuclein inclusions in olfactory structures are also reported in PD patients with respect to controls (Braak et al. 2003). A recent proteomic analysis of olfactory bulb region obtained from PD brain demonstrated the disruption of olfactory MAPK, PDK1/PKC, and MKK3-6/p38 MAPK signaling pathways (Lachén-Montes et al. 2019) indicating the important role of olfactory bulb proteostasis in PD pathogenesis.

Substantia Nigra (SN)

Dopaminergic neuronal loss and formation of LBs in SN are associated with the middle stages of PD (Braak et al. 2003). Proteomic analysis of SN region of human brain demonstrated downregulation of neurofilament-L/M chains and upregulation of peroxiredoxin (Prx) 2, mitochondrial complex III, ATP synthase D, complexin I, profilin, L-type calcium channel δ-subunit, and fatty acid-binding protein in PD patients in comparison to control subjects. These results provide the evidence of disrupted mitochondrial and antioxidant function in PD (Basso et al. 2004). Two other proteomic studies utilizing SN region of PD patients also confirmed the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, cytoskeleton impairment, and oxidative stress in PD pathogenesis (Kitsou et al. 2008; Licker et al. 2012). A recent proteomic study conducted on SN and ventral tegmental area (VTA) of brain has shown that the level of prohibitin protein, involved in maintenance of mitochondrial integrity, was decreased in PD patients in comparison to controls (Dutta et al. 2018). Additionally, proteins (calmodulin, γ-enolase, and myelin basic protein) identified in the SN region have shown an overlap with the proteins previously reported in CSF (Kitsou et al. 2008). Licker and colleagues have found that the expression of a novel protein, cytosolic non-specific dipeptidase 2, was increased in SN region of PD patients. The protein could be associated with protein aggregation in PD (Licker et al. 2012). Many other proteins related to mitochondria, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism were also found to be differentially regulated in this study (Table 1). Dysregulation of proteins involved in various pathways such as retinoid metabolism, L-DOPA methylation, redox metabolism, iron metabolism, glial activation along with few novel proteins such as adenosylhomocysteinase (methylation), aldehyde dehydrogenase 1, and cellular retinol-binding protein 1 (aldehyde metabolism), was found in the SN region of the PD brain in comparison with normal controls. The study also showed that there was no change in the expression pattern of familial PD-related proteins DJ-1 and UCHL1 between controls and PD patients (Werner et al. 2008). A recent proteomic study of nigral tissues of PD patients identified 1795 proteins and out of them, 204 proteins were found to be differentially expressed in PD patients in comparison to controls (Licker et al. 2014). Two novel proteins, nebulette and gamma glutamyl hydrolase (GGH), were found to be upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in PD samples in comparison to control subjects. Upregulation of nebulette has been correlated with impaired cytoskeleton and downregulation of GGH, a key enzyme in folate metabolism, could be due to loss of iron-containing neurons in the SN region during PD (Licker et al. 2014). Overall, proteomics of the SN region of PD sufferer’s brain has confirmed the central role of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and protein aggregation in PD pathology along with identification of many novel proteins (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of some important proteomic studies conducted on brain tissue and biofluids of PD patients

| S. no. | Cell/tissue/region | Pathway/organelle affected | Major proteins altered | Level/modification in PD patients (in comparison to controls) | Techniques used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain regions | ||||||

| 1 | LC | Calcium homeostasis and transport | Regucalcin | Upregulation | 1-DE and nano-LC–MS/MS | van Dijk et al. (2012) |

| Kinectin | Downregulation | |||||

| 2 | Olfactory bulb | Cell signaling | Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1, p38 α and β subunits, monomeric α-synuclein | Upregulation | MALDI-IMS | Lachén-Montes et al. (2019) |

| ERK1/2, MKK3/6-p38 MAPK | Downregulation | |||||

| 3 | SN | Mitochondria, cytoskeleton | Prx2, mitochondrial complex III, ATP synthase D chain, complexin I, profilin, fatty acid-binding protein | Upregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-TOF–MS | Basso et al. (2004) |

| L and M neurofilament chains | Downregulation | |||||

| 4 | SN | Aldehyde metabolism, L-DOPA methylation, Glial activation, redox metabolism, iron metabolism | Aldehyde dehydrogenase A1 and cellular retinol-binding protein 1, S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase 1, glutathione-S-transferase (GST) M3, GST P1, GST O1, and SH3-binding glutamic acid-rich-like protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, glial maturation factor β, galectin 1, and sorcin A, H-ferritin, β-tubulin cofactor A, Annexin V | Upregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-MS | Werner et al. (2008) |

| V-type ATPase A1 | Downregulation | |||||

| 5 | SN | Mitochondria, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism | Cytosolic non-specific dipeptidase 2, guanine nucleotide binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit β, vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 29, Ferritin L-chain | Upregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-TOF/TOF–MS | Licker et al. (2012) |

| cytochrome b–c1 subunit 2, and ATP synthase subunit D | Downregulation | |||||

| 6 | SN | Cytoskeleton, folate metabolism | γ-glutamyl hydrolase | Upregulation | Tandem mass tag labeling, LC–MS/MS | Licker et al. (2014) |

| Nebulette | Downregulation | |||||

| 7 | SN and VTA | Mitochondrial integrity | Prohibitin | Downregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-TOF/TOF | Dutta et al. (2018) |

| 8 | Cortex | Antioxidation | SOD 1 | Carbonylation and oxidation | MALDI-TOF–MS and HPLC- ESI–MS/MS | Choi et al. (2005) |

| 9 | Cortex | Glycolysis | Aldolase A, enolase, glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase | Oxidation | 2-DE and capLC nano-ESI- MS/MS | Gómez and Ferrer (2009) |

| 10 | Cortex | Antioxidation | Prx2 and Prx6 | Upregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-MS | Krapfenbauer et al. (2003) |

| Prx3 | Downregulation | |||||

| 11 | Cortex | Ubiquitination pathway | UCHL1 | Carbonylation and Oxidation | 2-DE, MALDI-TOF/MS, and HPLC-ESI/MS/MS | Choi et al. (2004) |

| 12 | Cortex | Oxidative stress | DJ-1 | Upregulation, Carbonylation and Oxidation | 2-DE, MALDI-TOF/MS, MALDI-TOF/TOF/MS/MS, and HPLC-ESI/MS/MS | Choi et al. (2006) |

| Subcellular structure | ||||||

| 13 | Mitochondrial fraction (SN region) | Mitochondrial stress | Ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase iron–sulfur subunit | Upregulation | Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology, Isotope Coded Affinity Tag and Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture | Jin et al. (2006) |

| Mortalin/mthsp70/GRP75, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit B14.7, ubiquinone oxidoreductase | Downregulation | |||||

| Biofluids | ||||||

| 14 | CSF | Oxidative stress, protein folding | DJ-1, α-synuclein | Downregulation | Gel filtration, MS, and Luminex assay | Hong et al. (2010) |

| 15 | CSF | Immune system, cell survival, antioxidation, lipoprotein metabolism | ApoE and autotaxin | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Guo et al. (2009) |

| Complement C3, C4α, isoforms of haptoglobin | Downregulation | |||||

| SOD1 | Oxidation | |||||

| 16 | CSF | Immune system | Complement proteins C3b, C4b, factor B | Downregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-TOF/TOF | Finehout et al. (2005) |

| 17 | CSF | Hemoglobin/globin metabolism | Serum albumin precursor, serum albumin chain-A, proline-rich repeat 14, and serum transferrin N-terminal lobe | Upregulation | 2-DE, MALDI-TOF, and LC–MS | Sinha et al. (2009) |

| hemoglobin β fragment and mutant globin | Downregulation | |||||

| 18 | CSF | Iron transportation, lipoprotein metabolism | Ceruloplasmin, ApoH | Downregulation | Isobaric Tagging for Relative and Absolute protein Quantification and MS/MS | Abdi et al. (2006) |

| 19 | CSF | Inflammation, neurodegeneration | EPHA4 and LRP1 | Upregulation | LC–MS/MS | Shi et al. (2015) |

| SPP1, CSF1R and TIMP1 | Downregulation | |||||

| 20 | CSF | Cell-surface adhesion protein Serum Glycoproteins | Neurexin-1 | Upregulation | LC- MALDI-TOF/TOF | Pan et al. (2008) |

| α-1-Acid glycoprotein | Downregulation | |||||

| 22 | CSF | Cell growth, lipoprotein metabolism, Immune system | Interleukin 8, β2-microglobulin, and vitamin D-binding protein | Upregulation | Multiplex assay | Zhang et al. (2008a, b) |

| brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ApoA2 and ApoE | Downregulation | |||||

| 23 | CSF | Cell adhesion | Neural cell adhesion molecule-120, α-dystroglycan | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Yin et al. (2009) |

| 24 | Blood Plasma | Hemoglobin clearance/metabolism | Haptoglobin-related protein precursor, truncated β-globin | Upregulation | 2-DE and MALDI-TOF/TOF | Sinha et al. (2007) |

| 25 | Blood Plasma | Inflammation, phagocytosis, cell signaling | PRNP, HSPG2, MEGF8, and NCAM1 | Upregulation | Selected reaction monitoring, N-glycocapture, and LC–MS | Pan et al. (2014) |

| 26 | Blood Plasma | Lipid metabolism, immunity, protein folding | Clusterin, complement C1r subcomponent, ApoA1 (exosomal proteins) fibrinogen γ-chain | Downregulation | 2D-DIGE and MALDI-TOF/TOF/MS | Kitamura et al. (2018) |

| 27 | Blood Serum | Aggregation of proteins | Serum amyloid P component | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Chen et al. (2011a, b) |

| 28 | Blood Serum | Lipid metabolism, intracellular transport, cell proliferation, and immunoregulation | Clusterin, transthyretin, immunoglobulin kappa-chain VK-1, Ig γ-3 chain C region, β-2-glycoprotein 1 | Upregulation | 2-DE and ESI-Q-TOF–MS/MS | Zhao et al. (2010) |

| Serum amyloid A protein, haptoglobin, complex-forming glycoprotein HC, KIAA0325 protein, and myosin heavy chain IIx/d | Downregulation | |||||

| 29 | Blood Serum | Blood clotting | Fibrinogen γ-chain, full size inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Lu et al. (2014) |

| fragmented ApoA4 | Downregulation | |||||

| 30 | Blood Serum | Inflammation, immune response, lipoprotein metabolism | Transthyretin, ApoA1, complement factor H | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Alberio et al. (2013) |

| complement C3, haptoglobin, ApoE | Downregulation | |||||

| 31 | Blood Lymphocytes | Cytoskeleton, mitochondria | Cofilin-1, actin, mitochondrial ATP synthase β-subunit | Upregulation | 2-DE and LC–MS/MS | Mila et al. (2009) |

| Tropomyosin, γ -fibrinogen | Downregulation | |||||

| 32 | Tears | Immune response, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress | Prx6, annexin-A5, and glutathione-S-transferase-A1, ApoD, ApoA4, ApoA1, α-2-macroglobulin | Upregulation | Bottom up LC–MS/MS | Boerger et al. (2019) |

| α-1-antiproteinase, Profilin 1, lactotransferrin, clusterin, galectin 3, β-2 microglobulin | Downregulation | |||||

1-DE one-dimensional gel electrophoresis, 2-DE two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, 2-D DIGE two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis, MALDI-TOF/TOF–MS matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, MALDI-IMS matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry, HPLC–ESI–MS/MS high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry, LC–MS/MS liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, ESI electrospray ionization, ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS electrospray ionization-quadrupole-time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry

Cerebral Cortex

The cerebral cortex is found to be severely affected in later stages of PD. Several disease-associated features such as mitochondrial abnormalities and decreased glucose metabolism are reported in the cerebral cortex of PD patients (Ferrer 2009). Three enzymes aldolase A, enolase 1 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were found to be altered by oxidation in frontal cortex of PD patients, which provide evidence for impaired glycolysis and energy metabolism in PD (Gómez and Ferrer 2009). A number of antioxidant proteins in the brain, such as Prx, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, provide protection against oxidative stress. Proteomic analysis of the cerebral cortex of the PD brain shows that the expression of Prx2 and Prx6 was increased while Prx3 was decreased in the frontal cortex of PD patient in comparison to control subjects. However, there was no significant change in the levels of Prx1, SOD2, and glutathione-S-transferase ω1 between both the groups (Krapfenbauer et al. 2003). Another proteomic study conducted in the frontal cortex region of brain of PD patients revealed that there is carbonylation and oxidation of Cys-146 to cysteic acid in the SOD1 protein (Choi et al. 2005). These studies demonstrate that the compromised antioxidant defense system is critical for PD pathogenesis.

Oxidative modification, carbonylation, or phosphorylation of familial PD-related proteins in cerebral cortex of PD patients could be responsible for their altered function in PD brain. The UCHL1 protein was found to be severely modified by carbonyl formation, methionine oxidation, and cysteine oxidation (Choi et al. 2004) while DJ-1 protein was found irreversibly oxidized by carbonylation and methionine oxidation in PD brains (Choi et al. 2006). A large-scale proteomic study conducted on prefrontal cortex sample of PD patients supported the involvement of mitochondrial pathways in PD pathology. Furthermore, with the application of Genome Wide Association Study, it was found that SNCA loci showed significantly increased protein level, but no alteration in RNA level, which again supports that the altered level of α-synuclein protein is involved in PD pathogenesis (Dumitriu et al. 2016). Another recent global quantitative proteomic analysis of two brain regions (frontal cortex and anterior cingulate gyrus) obtained from four different groups; healthy controls, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), PD, and co-morbid AD/PD cases led to the identification of 127,321 total unique peptides which mapped to 11,840 unique protein groups. This dataset is useful for understanding the molecular signatures and pathways involved in the pathogenesis of both AD and PD (Ping et al. 2018).

Proteomics of Subcellular Organelle of PD Brain

Among various subcellular organelles, mitochondria are the most studied organelle for understanding PD pathogenesis and are known to play a central role in PD pathology. A number of proteins related to disease such as PINK1, DJ-1, and parkin are either localized inside or interact with mitochondria, and death of dopaminergic neurons is caused due to induction of oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways involving mitochondria (Nicotra and Parvez 2002; Dixit et al. 2013). However, only a single proteomic study has been conducted on the mitochondrial fraction of the SN region of the PD brain, which demonstrated that 119 out of 842 identified proteins were significantly different in their relative abundance in comparison to age-matched controls. Out of these proteins, a novel mitochondrial stress protein mortalin (mthsp70/GRP75) was found to be decreased in PD patients in comparison to controls. The study also showed that mortalin mediates rotenone-induced toxicity in cellular model of PD through enhanced oxidative stress, and mitochondrial and proteasomal dysfunctions (Jin et al. 2006).

Proteomics of Biofluids of PD Patients

Biofluids such as plasma, serum, and CSF are always preferred human samples than brain tissue for proteomic analysis due to their easy and disease stage-specific availability. As the genomic or transcriptomic study is not possible for these fluids, the proteomics approach is the suitable choice for the analysis of global changes taking place in these samples and for the discovery of diagnostic biomarkers (Veenstra et al. 2005).

CSF

CSF represents a useful source for the identification of PD biomarkers (Guo et al. 2009; Waybright 2013). Since CSF proteins are not present in a large amount as compared to their corresponding serum proteins, a sensitive analytical technique is required to analyze these proteins (Romeo et al. 2005). CSF can be obtained at any stage of PD which makes it possible to assess and monitor the protein alterations with the progression of disease. Various proteomic studies have been successfully conducted on CSF of PD patients in search of biomarker for the disease (van Dijk et al. 2010) (Table 1). The proteins such as neurexin-1, R-1-acid glycoprotein, and β-2-glycoprotein 1 were validated as biomarkers in the CSF of PD patients by applying targeted quantitative proteomics approach (Pan et al. 2008). Use of sensitive Luminex assay revealed that DJ-1 and α-synuclein protein levels were decreased in CSF of PD patients in comparison to normal controls and AD patients. However, no association was reported between DJ-1 and α-synuclein levels and PD severity (Hong et al. 2010). Guo et al. reported the decreased abundance of Apolipoprotein (Apo) E and autotaxin, and increased levels of complement C3, C4α, and three isoforms of haptoglobin along with oxidative modification of SOD1 in CSF samples of PD patients in comparison to controls (Guo et al. 2009). Similarly, another proteomic study showed alterations in complement protein isoforms C3b, C4b, and factor B in CSF of PD patients in comparison to controls suggesting compromised immunity in PD patients (Finehout et al. 2005). Sinha et al. have shown that hemoglobin β-fragment and mutant globin were decreased while serum albumin precursor, serum albumin chain-A, proline-rich repeat 14, and serum transferrin N-terminal lobe were increased in CSF samples of PD patients in comparison to controls (Sinha et al. 2009).

Ceruloplasmin is a ferroxidase enzyme that protects tissues from oxidative damage by regulating iron metabolism. Increase in protein carbonylation and oxidation of ceruloplasmin was observed in the CSF of PD patients in comparison to AD, dementia with LBs (DLB), and control samples which might be responsible for aggravated oxidative stress in PD patients (Olivieri et al. 2011). A multiplex quantitative proteomic approach applied to CSF samples of PD, AD, and DLB patients identified 72 proteins. Out of these, ceruloplasmin, chromogranin B, and ApoH proteins were found to be important for differentiating PD patients from controls as well as from other neurological patients (Abdi et al. 2006). Validation of these results in CSF samples of control subjects, AD, and PD patients has revealed an increased expression of interleukin 8 and vitamin D-binding protein, and decreased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ApoA2, and ApoE proteins in neurodegenerative diseases as compared to control samples (Zhang et al. 2008a, b). Similarly, another study has reported the upregulation of neural cell adhesion molecule-120 and α-dystroglycan in CSF of AD and PD patients in comparison to normal controls (Yin et al. 2009). The level of these proteins can be useful to distinguish PD patients from normal neurological controls. However, other protein β2-microglobulin was found upregulated specifically in PD patients and could help in differentiating PD from other neurodegenerative diseases (Zhang et al. 2008a, b; Yin et al. 2009). The proteome profiling of CSF of PD, AD patients (diseased controls), and healthy controls revealed that a combination of two peptides belonging to proteins TIMP1 (metalloproteinase inhibitor 1) and APLP1 (amyloid-like protein 1) is significantly correlated with disease severity in PD and a panel of five peptides belonging to proteins SPP1, LRP1, CSF1R, EPHA4 (Osteopontin, Prolow-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein1, Macrophage colony-stimulating factor1 receptor, Ephrin type-A receptor4), and TIMP1 are important in differentiating PD from healthy and diseased (AD) controls (Shi et al. 2015). Another recent proteomic study conducted on CSF samples obtained from control subjects and patients suffering from PD and atypical parkinsonian syndrome showed that the levels of acute phase/inflammatory proteins and neuronal/synaptic proteins were, respectively, increased or decreased in atypical parkinsonism, while their levels in PD subjects were intermediate between controls and atypical parkinsonism (Magdalinou et al. 2017). This reveals that neurodegeneration in PD is comparatively slower than other forms of Parkinsonism.

Blood

Expression of blood proteins changes rapidly in response to any external factor or pathological condition, and blood contains proteins derived from other tissues as well. This makes the blood a rich source of information for analyzing disease progression (Ray et al. 2011). The blood represents the useful source for the discovery of protein biomarker for PD due to the presence of various pathological features such as increase in the level of hydroxyl radicals with duration of disease (Ihara et al. 1999) and mitochondrial complex I deficiency in blood platelets of PD patients (Parker et al. 1989). Comparative proteomics of serum samples of PD patients and controls revealed alterations in 21 proteins belonging to different categories such as cell degeneration, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Out of these, 11 proteins were abnormally expressed only in the patients having mild symptoms and 14 in moderate-to-severe PD stage which shows that the proteome component of blood responds to disease severity (Goldknopf et al. 2009). Similarly, in another study, comparison of serum proteome of Chinese PD patients with control subjects revealed 15 differentially displayed proteins related with antioxidation, lipid metabolism, intracellular transport, cell proliferation, and immunoregulation (Zhao et al. 2010) (Table 1). Lu and colleagues have reported that fibrinogen γ-chain and inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 proteins show an increased abundance in serum samples of PD patients in comparison to controls while fragmented ApoA4 was present mainly in control samples. The level of these proteins may serve as diagnostic criteria for PD (Lu et al. 2014).

An automated literature analysis of studies conducted on the plasma samples of PD and control subjects revealed 9 proteins, including haptoglobin, transthyretin, ApoA1, serum amyloid P component, ApoE, complement factor H, fibrinogen γ, thrombin, and complement C3 as potential diagnostic proteins. Except serum amyloid P component, fibrinogen γ and thrombin, other 6 proteins were confirmed experimentally as markers of PD (Alberio et al. 2013). On the contrary, another proteomic study showed a significant increase in the level of serum amyloid P component in plasma of PD patients in comparison to controls which indicates the possibility of the protein to serve as a biomarker for PD (Chen et al. 2011a, b). An increase in haptoglobin-related protein precursor and truncated β-globin proteins in plasma of untreated PD patients and their restoration after L-DOPA treatment has been demonstrated by proteomic approach. Reduction in the abundance of truncated β-globin was observed in smoker PD patients pointing towards the protective role of smoking in PD (Sinha et al. 2007). A study conducted on plasma samples of the larger cohort (around 300 subjects) of PD patients along with healthy and diseased controls depicted that a combination of several peptides derived from proteins PRNP, HSPG2, MEGF8, and NCAM1 (major prion protein, heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2, multiple EGF-like domains 8, neural cell adhesion molecule 1) is useful to distinguish PD from normal subjects, and a combination of two peptides derived from proteins, MEGF8 and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1), show significant correlation with PD severity (Pan et al. 2014). Proteome profiling of exosomes isolated from plasma samples of PD patients and healthy subjects demonstrated that expression of ApoA1 protein in exosomes correlates with the disease progression while the level of plasma protein fibrinogen γ-chain was decreased in PD patients in comparison to controls and could be important for initial PD screening (Kitamura et al. 2018).

Proteome profiling of blood cells has provided the significant insights into the protein alterations in PD patients receiving different therapies. Comparison of proteome profile of peripheral lymphocytes of PD patients under L-DOPA or subthalamic nucleus deep-brain stimulation therapy with normal controls revealed that cytoskeletal proteins such as cofilin-1, tropomyosin, and an actin isoform were altered in patients regardless of the therapy. However, three proteins, namely, tropomyosin variant, protein disulfide isomerase A3, and actin fragment were found to be altered differently between the two therapy conditions (Mila et al. 2009). Peripheral blood lymphocytes respond well towards dopaminergic treatment as shown by the proteomic study conducted on T-lymphocytes derived from PD patients under L-DOPA and/or dopamine agonist treatment. Expression of 2 proteins, ATP synthase subunit β and proteasome subunit β type-2, was linearly correlated with L-DOPA dose while 7 proteins, namely, prolidase, actin-related protein 2, F-actin-capping protein subunit β, tropomyosin α-3 chain, proteasome activator complex subunit 1, Prx6, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase isoform were altered in patients receiving dopamine agonists. These results suggest that therapies involving dopaminergic stimulation may affect immunity of patients by altering T cell proteome (Alberio et al. 2012).

Tears

Dysfunction of lacrimal glands and reduction in tear secretion are common non-motor symptoms of PD (Bagheri et al. 1994). A recent proteomic analysis explored the potential of easily accessible tear fluid for PD diagnosis and demonstrated the dysregulation of several proteins related with immune response, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress in PD patients in comparison to normal controls (Boerger et al. 2019). The study provided the candidate proteins to be further validated as biomarker for PD.

Potential Samples from PD Patients for Proteomic Analysis: Future Directions

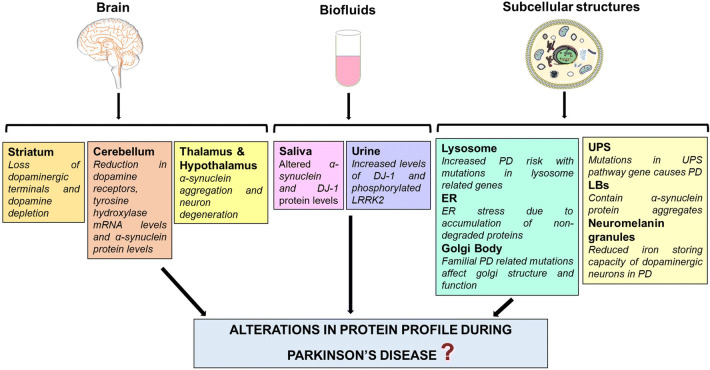

As described above, proteomic studies conducted on specific brain regions and biofluids of PD patients have provided significant clues about its mechanism and possible therapeutic options. However, careful analysis of past and present literature related to PD research points towards the crucial role of other prospective brain regions as well as biofluids in PD pathology which in future could serve as a useful source for the biomarker discovery by applying proteomic approach (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prospective samples for proteomic analysis of PD patients. Brain regions, biofluids, and subcellular structures derived from brain tissue have been selected on the basis of representation of disease-associated features/pathways in these samples

Brain Regions

Like SN, pathology of the striatum is also related to middle stages of PD progression and there is a 80% reduction in dopamine content in the striatum with the onset of motor symptoms in PD. Neurodegeneration in PD takes place through ‘dying back’ mechanism which means that neuronal terminals in striatum region are more prone to death than their cell bodies in the SN region (Dauer and Przedborski 2003). The study of protein profile of the striatum region of PD brain may solve many unanswered questions related to initiation of neurodegeneration process. Another important brain region is the cerebellum, which controls posture and motor functions (Wu and Hallett 2013). Akinesia has been correlated with abnormally increased blood flow in the cerebellum (Payoux et al. 2004). The levels of dopamine receptor, tyrosine hydroxylase, and α-synuclein were found to be decreased in the cerebellum of PD patients (Hurley et al. 2003). Future studies focusing on protein profiling of the cerebellum of PD sufferers may help to identify the proteins involved in the regulation of motor functions. Similarly, thalamus and hypothalamus regions of the PD patient’s brain show a significant amount of neurodegeneration at advanced stages of PD and can be used for proteomic analysis (Prakash et al. 2016).

Biofluids

Abnormal salivation is one of the common non-motor symptoms of PD (Edwards et al. 1991). Additionally, Lewy pathology in the glands responsible for saliva secretion and altered expression of α-synuclein and DJ-1 is reported in the saliva of PD patients (Del Tredici et al. 2010; Devic et al. 2011). DJ-1 level in saliva has also been correlated with disease severity (Masters et al. 2015). Proteomics of saliva of PD patients represent a convenient and useful tool for biomarker discovery as the sample can be obtained in large quantity and at various time intervals. The use of saliva is also advantageous in comparison to blood and CSF due to its non-invasive sampling (Haas et al. 2012).

An increase in the level of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, an indicator of oxidative stress, and DJ-1 protein was found in the urine of PD patients in comparison to control (Sato et al. 2005; Ho et al. 2014). Also, an elevated ratio of phosphorylated Ser-1292 LRRK2 to total LRRK2 in urine exosomes was found to be associated with PD in LRRK2 mutation carriers (Fraser et al. 2016). These studies indicate the strong possibility of discovering specific biomarker for PD in future with the help of protein profiling of urine.

Subcellular Structures

The central role of mitochondria in the pathophysiology of PD has been well documented (Jin et al. 2005; Pienaar et al. 2010); however, it does not provide a complete picture of PD mechanism. The involvement of endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi body, lysosome, UPS, and important role of the proteins localized within these structures in PD pathology should not be ignored (Slodzinski et al. 2009; Ruan et al. 2010; Rabouille and Haase 2015; Domingues et al. 2008). Besides, detailed analysis of the mitochondrial proteome of SN and other brain regions is required to understand the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD. As neuronal cell death in PD involves intercommunication and participation of these subcellular structures (Domingues et al. 2008; Arduíno et al. 2009), identification of changes in their protein profile may fill the knowledge gaps associated with the mechanism of neurodegeneration in PD.

Subcellular structures such as LBs and neuromelanin granules are potential samples for future investigations of PD mechanism with the help of proteomics. LBs are the pathological hallmark of PD and contain primarily α-synuclein protein aggregates. Proteomic analysis of LBs obtained from brain tissue of patients with LB pathology revealed that the several kinases and ubiquitin ligases together with a novel deubiquitinating enzyme (otubain 1) were co-enriched with α-synuclein. (Xia et al. 2008). Another proteomic study conducted on porcine brain synaptosomes identified the conformation-specific interacting proteins of human α-synuclein monomers and oligomers (Betzer et al. 2015). These studies depict the role of interacting proteins in the formation of α-synuclein inclusions and its toxicity in neurodegenerative diseases. Leverenz and colleagues collected around 2500 cortical LBs from the temporal cortex of patients with cortical LB disease by utilizing laser capture microdissection technique. Proteomic analysis of these LBs identified 296 proteins including 14-3-3, α-synuclein, heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein, amyloid-β A4, and UCHL1 indicating the important role of these proteins in LB formation and neurodegeneration in PD (Leverenz et al. 2007).

Reduced capacity of neuromelanin to accumulate iron in the diseased state makes dopaminergic neurons more vulnerable to oxidative stress (Double et al. 2002). The iron-storing protein, L-ferritin, has been identified by proteomic approach in the neuromelanin granules of the SN region of normal brain, which directly indicates the role of neuromelanin in iron homeostasis (Tribl et al. 2009). Neuromelanin granules can be isolated with the help of a sequential fractionation strategy or by laser microdissection and can be further used for proteomic analysis (Tribl et al. 2005; Plum et al. 2016). The latter technique uses a relatively reduced sample amount, i.e., 10-μm-thin sections of brain tissue, which is particularly important in human studies where the SN tissue sample is limited. Study of sub-proteome allows more specific and detailed analysis of various subcellular structures and helps to overcome the dominance of the most abundant proteins over those proteins that are distinctively expressed in disease-associated cells (Tribl et al. 2006).

Limitations

Proteomic analyses of human brain tissue, blood, and CSF provide evidence-based direct information about the pathological changes occurring in PD and has raised the hope for the development of specific biomarker and treatment plans for the incurable PD. However, there are vital challenges which need to be surpassed for obtaining more accurate results using proteomic technique. Major limitations of proteomics of human brain tissue include difficult accessibility and ethical concerns related to its use for the experimental purpose (Ward et al. 2009). Moreover, a human brain can be used only after the death of the patient, which will reflect pathological changes present at the last stage of PD. Sometimes, the long post-mortem delay can affect the expression level of proteins or lead to their degradation (Licker et al. 2009; Licker and Burkhard 2014).

Brain tissue sample prepared by traditional methods does not contain only neuronal cells of interest, but is a mixture of heterogeneous cell population, including glial cells, astrocytes, and other types of brain cells. The data obtained from whole brain tissue proteomics represent the low signal-to-noise ratio, which can be overcome by fractionation of brain tissue (Craft et al. 2013). However, analysis of sub-proteome further involves many challenges. Isolation of specific cell organelle suffers from the impurities of other cellular structures which may yield non-specific results. Fractionation of desired part of the tissue and further its subfractionation are crucial steps and require more sophisticated and reliable techniques. Moreover, this decreases the amount of protein available for the experiment. Since there is no amplification method available for protein sample, a highly sensitive technique is required for sub-proteome analysis of the brain tissue (Craft et al. 2013).

There are several limitations linked with proteomics of CSF or blood samples. Despite the easy availability of CSF samples from PD patients in comparison to brain tissue, it is very difficult to receive ethical approval for the lumbar puncture to collect CSF sample and it becomes even more challenging in case of normal individuals (Ward et al. 2009). Characterization of CSF proteome requires a careful approach in sample collection, storage, preparation, analysis, and data mining for reproducible results (Waybright 2013). Salt and blood contaminants should be completely removed from the CSF sample before analysis. Moreover, due to the low protein content of CSF, prefractionation of sample is necessary in some cases (Shi et al. 2009). Sample collection, storage time, and duration have a significant effect on blood proteome as well. The major limitation of blood proteomics is the presence of some proteins in a fairly large amount which masks the expression of other low abundant proteins (Anderson and Anderson 2002). Technical difficulties associated with proteomic analysis of saliva and urine samples include low protein concentration and high intra-individual and inter-individual variability (Thongboonkerd 2007).

Conclusions

In spite of the great revolution in the technology, it is still a dream to develop an efficient treatment strategy for the PD, a strategy which not only slows down its progression but also eradicates this fatal disease from the patient’s body. Advanced as well as conventional techniques in the field of proteomics can offer a new vision to identify and develop the novel biomarkers and therapeutic plans for PD. Detailed analysis of global and subcellular proteome of PD-associated brain regions may decipher the cellular basis of disease mechanism along with role of specific brain regions in PD pathogenesis. Since the origin of PD is in the brain, the poorly accessible organ, the discovery of a PD biomarker from easily available sample is necessary for the diagnosis of the disease. Proteomic analysis of biofluids such as blood, saliva, tears and urine may lead to the discovery of such biomarkers which will help in early detection of PD.

Acknowledgements

Dr. M. P. Singh and CSIR-Indian Institute of Toxicology Research, Lucknow, India are acknowledged for providing guidance and research facilities to AD.

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- UCHL1

Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1

- LRRK2

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- PINK1

PTEN-induced kinase 1

- LNs

Lewy neurites

- LBs

Lewy bodies

- LC

Locus coeruleus

- SN

Substantia nigra

- Prx

Peroxiredoxin

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- GGH

Gamma glutamyl hydrolase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Apo

Apolipoprotein

- TIMP1

Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1

- APLP1

Amyloid-like protein 1

- LRP1

Prolow-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- CSF1R

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor

- EPHA4

Ephrin type-A receptor 4

- PRNP

Major prion protein

- HSPG2

Heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2

- MEGF8

Multiple EGF-like domains 8

- NCAM1

Neural cell adhesion molecule 1

- 2-DE

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- 2-D DIGE

Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis

- MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- MALDI-IMS

MALDI imaging mass spectrometry

- LC-ESI-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry

- ESI-Q-TOF MS/MS

Electrospray-quadrupole-time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry

- ESI-MS

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

Author Contributions

AD-Review design, literature collection, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. RM-Review design and manuscript preparation. AKS-Review design and manuscript preparation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All reported studies involving human participants/animals have been previously published and procedures performed in studies were in accordance with applicable ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee, international, national, and/or institutional guidelines, and 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the reported studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdi F, Quinn JF, Jankovic J et al (2006) Detection of biomarkers with a multiplex quantitative proteomic platform in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. J Alzheimers Dis JAD 9:293–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberio T, Pippione AC, Comi C et al (2012) Dopaminergic therapies modulate the T-CELL proteome of patients with Parkinson’s disease. IUBMB Life 64:846–852. 10.1002/iub.1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberio T, Bucci EM, Natale M et al (2013) Parkinson’s disease plasma biomarkers: an automated literature analysis followed by experimental validation. J Proteomics 90:107–114. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NL, Anderson NG (2002) The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP 1:845–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduíno DM, Esteves AR, Cardoso SM, Oliveira CR (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria interplay mediates apoptotic cell death: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 55:341–348. 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri H, Berlan M, Senard JM et al (1994) Lacrimation in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 17:89–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso M, Giraudo S, Corpillo D et al (2004) Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Proteomics 4:3943–3952. 10.1002/pmic.200400848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzer C, Movius AJ, Shi M et al (2015) Identification of synaptosomal proteins binding to monomeric and oligomeric α-synuclein. PLoS ONE 10:e0116473. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerger M, Funke S, Leha A et al (2019) Proteomic analysis of tear fluid reveals disease-specific patterns in patients with Parkinson’s disease—a pilot study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U et al (2003) Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U et al (2004) Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res 318:121–134. 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen DP, Michell AW, Barker RA (2011) Parkinson’s disease—the continuing search for biomarkers. Clin Chem Lab Med 49:393–401. 10.1515/CCLM.2011.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchberger AR, DeLaney K, Johnson J, Li L (2018) Mass spectrometry imaging: a review of emerging advancements and future insights. Anal Chem 90:240–265. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AHV, National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2006) Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 5:235–245. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Yoshioka H, Kim GS et al (2011a) Oxidative stress in ischemic brain damage: mechanisms of cell death and potential molecular targets for neuroprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 14:1505–1517. 10.1089/ars.2010.3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H-M, Lin C-Y, Wang V (2011b) Amyloid P component as a plasma marker for Parkinson’s disease identified by a proteomic approach. Clin Biochem 44:377–385. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Levey AI, Weintraub ST et al (2004) Oxidative modifications and down-regulation of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 associated with idiopathic Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. J Biol Chem 279:13256–13264. 10.1074/jbc.M314124200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Rees HD, Weintraub ST et al (2005) Oxidative modifications and aggregation of Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase associated with Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. J Biol Chem 280:11648–11655. 10.1074/jbc.M414327200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Sullards MC, Olzmann JA et al (2006) Oxidative damage of DJ-1 is linked to sporadic Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases. J Biol Chem 281:10816–10824. 10.1074/jbc.M509079200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft GE, Chen A, Nairn AC (2013) Recent advances in quantitative neuroproteomics. Methods San Diego Calif 61:186–218. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S (2003) Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 39:889–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Tredici K, Hawkes CH, Ghebremedhin E, Braak H (2010) Lewy pathology in the submandibular gland of individuals with incidental Lewy body disease and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 119:703–713. 10.1007/s00401-010-0665-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devic I, Hwang H, Edgar JS et al (2011) Salivary α-synuclein and DJ-1: potential biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Brain 134:e178–e178. 10.1093/brain/awr015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit A, Srivastava G, Verma D et al (2013) Minocycline, levodopa and MnTMPyP induced changes in the mitochondrial proteome profile of MPTP and maneb and paraquat mice models of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Mol Basis Dis 1832:1227–1240. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues AF, Arduíno DM, Esteves AR et al (2008) Mitochondria and ubiquitin-proteasomal system interplay: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med 45:820–825. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL (2012) Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 8:329–339. 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Double KL, Ben-Shachar D, Youdim MBH et al (2002) Influence of neuromelanin on oxidative pathways within the human substantia nigra. Neurotoxicol Teratol 24:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu A, Golji J, Labadorf AT et al (2016) Integrative analyses of proteomics and RNA transcriptomics implicate mitochondrial processes, protein folding pathways and GWAS loci in Parkinson disease. BMC Med Genomics 9:5. 10.1186/s12920-016-0164-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D, Ali N, Banerjee E et al (2018) Low levels of prohibitin in substantia nigra makes dopaminergic neurons vulnerable in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 55:804–821. 10.1007/s12035-016-0328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LL, Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM et al (1991) Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 6:151–156. 10.1002/mds.870060211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I (2009) Early involvement of the cerebral cortex in Parkinson’s disease: convergence of multiple metabolic defects. Prog Neurobiol 88:89–103. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finehout EJ, Franck Z, Lee KH (2005) Complement protein isoforms in CSF as possible biomarkers for neurodegenerative disease. Dis Markers 21:93–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser KB, Moehle MS, Alcalay RN, West AB (2016) Urinary LRRK2 phosphorylation predicts parkinsonian phenotypes in G2019S LRRK2 carriers. Neurology 86:994–999. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser T (2007) Update on the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 22(Suppl 17):S343–350. 10.1002/mds.21676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldknopf IL, Bryson JK, Strelets I et al (2009) Abnormal serum concentrations of proteins in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 389:321–327. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez A, Ferrer I (2009) Increased oxidation of certain glycolysis and energy metabolism enzymes in the frontal cortex in Lewy body diseases. J Neurosci Res 87:1002–1013. 10.1002/jnr.21904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Sun Z, Xiao S et al (2009) Proteomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson’s disease patients. Cell Res 19:1401–1403. 10.1038/cr.2009.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BR, Stewart TH, Zhang J (2012) Premotor biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease—a promising direction of research. Transl Neurodegener 1:11. 10.1186/2047-9158-1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DH, Yi S, Seo H, et al (2014) Increased DJ-1 in urine exosome of Korean males with Parkinson’s disease. BioMed Res Int. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/704678/. Accessed 8 Oct 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hong Z, Shi M, Chung KA et al (2010) DJ-1 and α-synuclein in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 133:713–726. 10.1093/brain/awq008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley MJ, Mash DC, Jenner P (2003) Markers for dopaminergic neurotransmission in the cerebellum in normal individuals and patients with Parkinson’s disease examined by RT-PCR. Eur J Neurosci 18:2668–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara Y, Chuda M, Kuroda S, Hayabara T (1999) Hydroxyl radical and superoxide dismutase in blood of patients with Parkinson’s disease: relationship to clinical data. J Neurol Sci 170:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Meredith GE, Chen L et al (2005) Quantitative proteomic analysis of mitochondrial proteins: relevance to Lewy body formation and Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 134:119–138. 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Hulette C, Wang Y et al (2006) Proteomic identification of a stress protein, mortalin/mthsp70/GRP75: relevance to Parkinson disease. Mol Cell Proteomics 5:1193–1204. 10.1074/mcp.M500382-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasap M, Akpinar G, Kanli A (2017) Proteomic studies associated with Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Proteomics 14:193–209. 10.1080/14789450.2017.1291344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y, Kojima M, Kurosawa T et al (2018) Proteomic profiling of exosomal proteins for blood-based biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 392:121–128. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsou E, Pan S, Zhang J et al (2008) Identification of proteins in human substantia nigra. Proteomics Appl 2:776–782. 10.1002/prca.200800028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N et al (2003) Aberrant expression of peroxiredoxin subtypes in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res 967:152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachén-Montes M, González-Morales A, Iloro I et al (2019) Unveiling the olfactory proteostatic disarrangement in Parkinson’s disease by proteome-wide profiling. Neurobiol Aging 73:123–134. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverenz JB, Umar I, Wang Q et al (2007) Proteomic identification of novel proteins in cortical lewy bodies. Brain Pathol Zur Switz 17:139–145. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00048.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licker V, Burkhard PR (2014) Proteomics as a new paradigm to tackle Parkinson’s disease research challenges. Transl Proteomics 4–5:1–17. 10.1016/j.trprot.2014.08.001 [Google Scholar]

- Licker V, Kövari E, Hochstrasser DF, Burkhard PR (2009) Proteomics in human Parkinson’s disease research. J Proteomics 73:10–29. 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licker V, Côte M, Lobrinus JA et al (2012) Proteomic profiling of the substantia nigra demonstrates CNDP2 overexpression in Parkinson’s disease. J Proteomics 75:4656–4667. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licker V, Turck N, Kövari E et al (2014) Proteomic analysis of human substantia nigra identifies novel candidates involved in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Proteomics 14:784–794. 10.1002/pmic.201300342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wan X, Liu B et al (2014) Specific changes of serum proteins in Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS ONE 9:e95684. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdalinou NK, Noyce AJ, Pinto R et al (2017) Identification of candidate cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Parkinsonism using quantitative proteomics. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 37:65–71. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters JM, Noyce AJ, Warner TT et al (2015) Elevated salivary protein in Parkinson’s disease and salivary DJ-1 as a potential marker of disease severity. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 21:1251–1255. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mila S, Albo AG, Corpillo D et al (2009) Lymphocyte proteomics of Parkinson’s disease patients reveals cytoskeletal protein dysregulation and oxidative stress. Biomark Med 3:117–128. 10.2217/bmm.09.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra A, Parvez S (2002) Apoptotic molecules and MPTP-induced cell death. Neurotoxicol Teratol 24:599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, McNaught K (2011) Parkinson’s disease, proteins, and prions: milestones. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 26:1056–1071. 10.1002/mds.23767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri S, Conti A, Iannaccone S et al (2011) Ceruloplasmin oxidation, a feature of Parkinson’s disease CSF, inhibits ferroxidase activity and promotes cellular iron retention. J Neurosci 31:18568–18577. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3768-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S, Rush J, Peskind ER et al (2008) Application of targeted quantitative proteomics analysis in human cerebrospinal fluid using a liquid chromatography matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (LC MALDI TOF/TOF) platform. J Proteome Res 7:720–730. 10.1021/pr700630x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C, Zhou Y, Dator R et al (2014) Targeted discovery and validation of plasma biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. J Proteome Res 13:4535–4545. 10.1021/pr500421v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker WD, Boyson SJ, Parks JK (1989) Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 26:719–723. 10.1002/ana.410260606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payoux P, Remy P, Damier P et al (2004) Subthalamic nucleus stimulation reduces abnormal motor cortical overactivity in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 61:1307–1313. 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar IS, Daniels WMU, Götz J (2008) Neuroproteomics as a promising tool in Parkinson’s disease research. J Neural Transm Vienna Austria 1996 115:1413–1430. 10.1007/s00702-008-0070-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar IS, Dexter DT, Burkhard PR (2010) Mitochondrial proteomics as a selective tool for unraveling Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Expert Rev Proteomics 7:205–226. 10.1586/epr.10.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping L, Duong DM, Yin L et al (2018) Global quantitative analysis of the human brain proteome in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Sci Data 5:180036. 10.1038/sdata.2018.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum S, Steinbach S, Attems J et al (2016) Proteomic characterization of neuromelanin granules isolated from human substantia nigra by laser-microdissection. Sci Rep. 10.1038/srep37139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash K, Bannur B, Chavan M et al (2016) Neuroanatomical changes in Parkinson′s disease in relation to cognition: an update. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 7:123. 10.4103/2231-4040.191416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabouille C, Haase G (2015) Editorial: Golgi pathology in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurosci 9:489. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Reddy PJ, Jain R et al (2011) Proteomic technologies for the identification of disease biomarkers in serum: advances and challenges ahead. Proteomics 11:2139–2161. 10.1002/pmic.201000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo MJ, Espina V, Lowenthal M et al (2005) CSF proteome: a protein repository for potential biomarker identification. Expert Rev Proteomics 2:57–70. 10.1586/14789450.2.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Q, Harrington AJ, Caldwell KA et al (2010) VPS41, a protein involved in lysosomal trafficking, is protective in Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 37:330–338. 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Mizuno Y, Hattori N (2005) Urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels as a biomarker for progression of Parkinson disease. Neurology 64:1081–1083. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000154597.24838.6B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Caudle WM, Zhang J (2009) Biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases: a proteomic approach. Neurobiol Dis 35:157–164. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Movius J, Dator R et al (2015) Cerebrospinal fluid peptides as potential Parkinson disease biomarkers: a staged pipeline for discovery and validation. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP 14:544–555. 10.1074/mcp.M114.040576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Patel S, Singh MP, Shukla R (2007) Blood proteome profiling in case controls and Parkinson’s disease patients in Indian population. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 380:232–234. 10.1016/j.cca.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Srivastava N, Singh S et al (2009) Identification of differentially displayed proteins in cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson’s disease patients: a proteomic approach. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 400:14–20. 10.1016/j.cca.2008.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slodzinski H, Moran LB, Michael GJ et al (2009) Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum protein (herp) is up-regulated in parkinsonian substantia nigra and present in the core of Lewy bodies. Clin Neuropathol 28:333–343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongboonkerd V (2007) Practical points in urinary proteomics. J Proteome Res 6:3881–3890. 10.1021/pr070328s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribl F, Gerlach M, Marcus K et al (2005) “Subcellular proteomics” of neuromelanin granules isolated from the human brain. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP 4:945–957. 10.1074/mcp.M400117-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribl F, Marcus K, Bringmann G et al (2006) Proteomics of the human brain: sub-proteomes might hold the key to handle brain complexity. J Neural Transm Vienna Austria 1996 113:1041–1054. 10.1007/s00702-006-0513-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribl F, Asan E, Arzberger T et al (2009) Identification of L-ferritin in neuromelanin granules of the human substantia nigra: a targeted proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP 8:1832–1838. 10.1074/mcp.M900006-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk KD, Teunissen CE, Drukarch B et al (2010) Diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease: a pathogenetically based approach. Neurobiol Dis 39:229–241. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk KD, Berendse HW, Drukarch B et al (2012) The proteome of the locus ceruleus in Parkinson’s disease: relevance to pathogenesis: locus ceruleus proteomics in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol 22:485–498. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra TD, Conrads TP, Hood BL et al (2005) Biomarkers: mining the biofluid proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP 4:409–418. 10.1074/mcp.M500006-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M, Güntert A, Campbell J, Pike I (2009) Proteomics for brain disorders—the promise for biomarkers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1180:68–74. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waybright TJ (2013) Preparation of human cerebrospinal fluid for proteomics biomarker analysis. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ 1002:61–70. 10.1007/978-1-62703-360-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner CJ, Heyny-von Haussen R, Mall G, Wolf S (2008) Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Proteome Sci 6:8. 10.1186/1477-5956-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Hallett M (2013) The cerebellum in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 136:696–709. 10.1093/brain/aws360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q, Liao L, Cheng D et al (2008) Proteomic identification of novel proteins associated with Lewy bodies. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr 13:3850–3856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S, Dixit A, Agrawal S et al (2012) Rodent models and contemporary molecular techniques: notable feats yet incomplete explanations of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Mol Neurobiol 46:495–512. 10.1007/s12035-012-8291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin GN, Lee HW, Cho J-Y, Suk K (2009) Neuronal pentraxin receptor in cerebrospinal fluid as a potential biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res 1265:158–170. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Zhang Z, Liu Y et al (2019) Recent advances in single-cell analysis by mass spectrometry. The Anal 144:824–845. 10.1039/C8AN01190G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sokal I, Peskind ER et al (2008a) CSF multianalyte profile distinguishes Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Am J Clin Pathol 129:526–529. 10.1309/W01Y0B808EMEH12L [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sokal I, Peskind ER et al (2008b) CSF multianalyte profile distinguishes Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Am J Clin Pathol 129:526–529. 10.1309/W01Y0B808EMEH12L [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Xiao WZ, Pu XP, Zhong LJ (2010) Proteome analysis of the sera from Chinese Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett 479:175–179. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]