Abstract

Introduction

In the Netherlands, bariatric surgery in adolescents is currently only allowed in the context of scientific research. Besides this, there was no clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents. In this paper, the development of a comprehensive clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity in the Netherlands is described.

Methods

The clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents consists of an eligibility assessment as well as comprehensive peri- and postoperative care. Regarding the eligibility assessment, the adolescents need to be identified by their attending pediatricians and afterwards be evaluated by specialized pediatric obesity units. If the provided treatment is considered to be insufficiently effective, the adolescent will anonymously be evaluated by a national board. This is an additional diligence procedure specifically established for bariatric surgery in adolescents. The national board consists of independent experts regarding adolescent bariatric surgery and evaluates whether the adolescents meet the criteria defined by the national professional associations. The final step is an assessment by a multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. The various disciplines (pediatrician, bariatric surgeon, psychologist, dietician) evaluate whether an adolescent is eligible for bariatric surgery. In this decision-making process, it is crucial to assess whether the adolescent is expected to adhere to postoperative behavioral changes and follow-up. When an adolescent is deemed eligible for bariatric surgery, he or she will receive preoperative counseling by a bariatric surgeon to decide on the type of bariatric procedure (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy). Postoperative care consists of intensive guidance by the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. In this guidance, several regular appointments are included and additional care will be provided based on the needs of the adolescent and his or her family. Furthermore, the multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention, in which the adolescents participated before bariatric surgery, continues in coordination with the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery, and this ensures long-term counseling and follow-up.

Conclusion

The implementation of bariatric surgery as an integral part of a comprehensive treatment for adolescents with severe obesity requires the development of a clinical pathway with a variety of disciplines.

Keywords: Severe obesity, Adolescents, Bariatric surgery, Clinical pathway

Introduction

Childhood obesity is currently one of the greatest and most pressing health challenges [1, 2]. In the Netherlands, 3.6% of the children aged 4–20 years had obesity in 2021 compared to only 2.7% in 2011 [3]. These numbers are worrisome as childhood obesity is associated with several chronic and life-threatening diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease [4]. Furthermore, children and adolescents with obesity have a lower health-related quality of life and have to deal with weight-related social stigmatizing and bullying [5–7].

Multidisciplinary lifestyle interventions remain the cornerstone treatment in childhood obesity. These interventions are generally family based and focus on nutrition, physical activity, sleep, psychosocial aspects of obesity, and behavioral change [8]. The Centre for Overweight Adolescent and Children’s Healthcare (COACH) is a specialized pediatric obesity unit that offers such a tailored multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention. Previous results from the COACH intervention revealed that children with severe obesity more often achieved a clinically significant decrease in their body mass index (BMI) z-score (≥−0.25) compared to adolescents after 2 years of intervention: 49.1% of the children versus 23.8% of the adolescents [9]. These results are in line with previously conducted research among adolescents with severe obesity and suggest that this group is particularly difficult to treat [10, 11]. For this particular group, other additional treatment strategies, such as pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery, should be integrated into a comprehensive treatment, especially as a previous study revealed that obesity during adolescence is associated with an increased cardiovascular mortality in adulthood [12].

In adults, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity in achieving weight loss and the remission of obesity-related comorbidities [13]. Furthermore, both improvements in generic and obesity-specific quality of life are observed in adults undergoing bariatric surgery [14]. In recent years, bariatric surgery is also increasingly performed in adolescents [15]. A systematic review among 455 adolescents with at least 5 year follow-up showed an average decrease in BMI of 14.6 kg/m2 after surgery [16]. The Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study revealed more remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension in adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery compared to adults [17]. Another meta-analysis among 950 adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery observed a readmission rate of 11.4% and a reoperation rate of 7.9%, which is comparable to the adult population [18]. Besides this, a systematic review found improvements of depression and quality of life scores in adolescents after bariatric surgery [19]. Overall bariatric surgery seems a safe and effective treatment modality for adolescents with severe obesity.

Bariatric surgery in adolescents is currently only allowed in the context of scientific research in the Netherlands. Furthermore, there was no clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents. This paper described the development of a comprehensive clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity. The clinical pathway consists of a multidisciplinary eligibility assessment as well as comprehensive peri- and postoperative care.

Methods

Comprehensive Clinical Pathway for Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents

Eligibility Assessment

Delegates with expertise in childhood obesity or bariatric surgery from the Dutch national professional associations were involved in the modeling of the eligibility criteria and assessment. In 2019, the obesity steering committee of the Dutch Society of Pediatrics released a position statement on bariatric surgery in adolescents based on an extensive literature review [20]. The main message of this position statement was that bariatric surgery should be available as an exceptional additional treatment option when specific criteria are met. Some examples of the criteria are that the pediatrician should be in charge of referrals and pre- and postoperative care. Furthermore, bariatric surgery should be integrated into a lifelong lifestyle counseling and in collaboration with a pediatric surgical center. Bariatric surgery can only be offered to adolescents if all relevant interventions have been tried and if abstinence from bariatric surgery would give a reasonable chance of physical or mental harm. The Dutch Society of Surgery followed this position statement and endorsed it. Based on this statement, the Dutch guideline for the treatment of childhood obesity established the following eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery [21]:

The causative and maintaining factors of obesity must be well understood.

Age- and sex-adjusted BMI of ≥40 kg/m2, or 35–40 kg/m2 in combination with severe comorbidity(s).

Counseling of a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for at least 1 year with inadequate results.

Tanner stage ≥4.

The adolescent is willing to participate in a postoperative multidisciplinary treatment program and lifelong follow-up.

For the development of the multidisciplinary eligibility assessment, stakeholder dialogues were held with delegates from the Dutch Society for Pediatrics, Dutch Society for Pediatric Surgery, Dutch Society for Gastrointestinal Surgery, and the Dutch Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. During these dialogues, experts in the field of childhood obesity or bariatric surgery established the eligibility assessment described below based on their own expertise and previous literature. Moreover, the Youth Care Inspectorate classified the developed eligibility assessment as diligent.

As bariatric surgery in adolescents is only allowed in the context of scientific research in the Netherlands, the abovementioned stakeholders stated that there should be one study (TEEN-BEST) [22]. The primary aim of the TEEN-BEST study is the implementation and assessment of the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of bariatric surgery as an integral part of a comprehensive treatment for adolescents with severe obesity in the Netherlands. In this study, the eligibility assessment is evaluated yearly through qualitative and quantitative methods. Based on these findings, the assessment will be optimized.

Identifying Adolescents Who Might Be Suitable for Bariatric Surgery

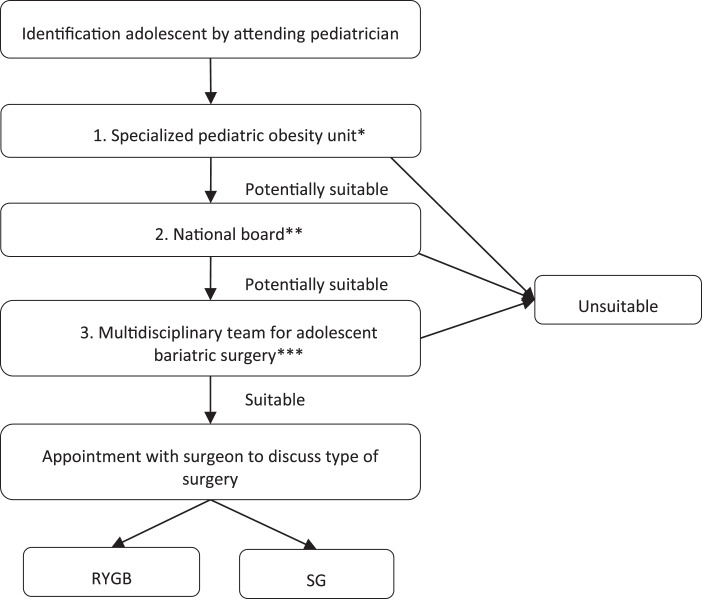

A flowchart of the eligibility assessment for bariatric surgery in adolescents is presented in Figure 1. At first, adolescents with severe obesity are identified by their attending pediatricians. If the pediatrician determines that the adolescent might be suitable for bariatric surgery according to the criteria previously described, the pediatrician refers the adolescent to one of the specialized pediatric obesity units. However, if the adolescent is already participating in a lifestyle intervention from a specialized pediatric obesity unit, then this step can be bypassed.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the eligibility assessment for bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity. RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy. *Evaluation by a specialized pediatric obesity unit will take approximately 1 month. **Evaluation by the national board will take approximately 1 month as they have a meeting once a month. ***Evaluation by the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery will take approximately 1 month as they have a meeting once a month.

Specialized Pediatric Obesity Units

In the Netherlands, there are five specialized pediatric obesity units. These units are located across the country and have expertise in the diagnostics and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. These units treat adolescents with severe obesity according to the current Dutch guideline [23]. In these units, multidisciplinary teams consisting of pediatricians, dieticians, and psychologists with a special focus on childhood obesity treat at least 100 children and adolescents with obesity a year. Furthermore, scientific research to improve diagnostics and treatment regarding childhood obesity is conducted.

In these specialized pediatric obesity units, the adolescents are evaluated to determine whether there are still opportunities to optimize the lifestyle intervention or work on preconditions or limiting factors (e.g., uncontrolled psychiatric disorders). If the provided treatment is considered to be insufficiently effective, the adolescents might be suitable for bariatric surgery. In short, a multidisciplinary analysis must have been performed to understand the causal and maintaining factors of obesity. Additionally, adolescents should have undergone a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for at least 1 year according to the Dutch guideline [21]. This intervention must have attempted to influence the causal and maintaining factors of obesity. Besides this, the specialized pediatric obesity units assess whether the adolescents are motivated to participate in long-term multidisciplinary lifestyle counseling and undergo bariatric surgery. All these conditions must be met before the adolescent can be evaluated anonymously by the national board.

National Board

The national board is an additional diligence procedure specifically founded in 2021 for bariatric surgery in adolescents. This board consists of pediatricians, psychologists, a pediatric surgeon, and a bariatric surgeon. All the board members have expertise in the treatment of adolescents with severe obesity or bariatric surgery. Besides this, the board is independent, and one of the members of the board is the chair. The specialized pediatric obesity units describe the adolescents according to a fixed format. In this format, the social situation, physical and psychological history, weight development, previous interventions, and motivation of the adolescents are described in detail. The board discusses the adolescents anonymously according to a checklist in an online monthly meeting. The checklist consists of 10 points developed collaboratively by the concerned professional associations (Table 1). If all members of the national board agree that the adolescent might be eligible for bariatric surgery, the board gives a positive advice and the adolescent will be referred by the specialized pediatric obesity unit to a multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. In case one or more members of the national board do not consider the adolescent eligible for bariatric surgery, the board gives a negative advice and referral is withheld. If one of the board members was the attending physician or part of the specialized pediatric obesity unit where the adolescent was evaluated before the national board, they may not offer an advice in this particular case.

Table 1.

Checklist of the national board

| 1. The adolescent is 13–17 years old and has a Tanner stage ≥IV | Yes/No |

| 2. The adolescent has severe obesity according to the IFSO criteria (adjusted for age and sex according to the IOTF criteria), with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 with at least one severe comorbidity* or a BMI ≥40 kg/m2 with less severe comorbidities** | Yes/No |

| 3. The causal and maintaining factors of the obesity are multidisciplinary analyzed according to the existing guidelines | Yes/No |

| 4. The adolescent has participated for at least 12 months in a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention including a psychological/systemic/pedagogical approach | Yes/No |

| 5. All relevant interventions have been tried, and abstinence from a bariatric procedure could cause physical or mental harm | Yes/No |

| 6. A specialized pediatric obesity unit has determined that the maximum conservative treatment has been provided and that there is therapy resistance | Yes/No |

| 7. Bariatric surgery is part of lifestyle counseling until the age of at least 25, and the adolescent is willing to participate in this | Yes/No |

| 8. There is no secondary obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, or syndromal disorder (e.g., Prader-Willi) | Yes/No |

| 9. There is a medical or psychiatric comorbidity or severe psychological suffering due to the degree of obesity | Yes/No |

| 10. Any psychological contraindications or risk factors known from the guideline*** that may promote a complicated course have been diagnosed and treated by a competent mental health professional and are therefore unlikely to pose a barrier to postoperative behavioral adaption and compliance | Yes/No |

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; IFSO, International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force [24].

*T2DM, hypertension, sleep apnea, liver fibrosis, severe psychological suffering.

**Impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, steatohepatitis, panniculitis, venous stasis, urine incontinence, weight-related joint complaints, reduced mobility due to weight, benign intracranial hypertension.

***Guideline bariatric psychology [25].

After 1 year, it will be evaluated whether the composition of the board is adequate by interviewing the board members. Admission of an adolescent who underwent bariatric surgery will be considered, as well as the need to include other disciplines. Over time, members of the board will be replaced, and new members will be carefully chosen in consensus with the board and the professional associations to ensure independence.

Multidisciplinary Team for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery

After a positive evaluation of the national board, the adolescents will be referred to one of the specialized pediatric obesity units with a multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. At the moment, there is only one multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery in the Netherlands. This team is located at the Maastricht University Medical Centre + (COACH) and Máxima MC. The team consists of a bariatric surgeon, a pediatrician, a pediatric psychologist, an academic dietician, a care coordinator, and a pediatric surgeon who can be consulted when necessary. Once 20 adolescents have undergone surgery, two other specialized pediatric obesity units will establish a similar multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. The number 20 was chosen, so that experience can be gained in one unit, and that in this unit the clinical pathway can be refined. Afterwards, this experience and the optimized clinical pathway can be shared with the other specialized pediatric obesity units.

First of all, the adolescents and their families are seen by the care coordinator; in this consultation, the pre- and postoperative care, the necessary behavioral changes, and the bariatric procedures including possible complications will be discussed. If the adolescent and his or her family want to proceed with bariatric surgery, the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery will evaluate whether the adolescent is eligible for bariatric surgery. This is a careful procedure in which the various disciplines make the assessment of eligibility based on interviews and examinations. In this decision-making process, it is crucial to assess whether the adolescent is expected to adhere to postoperative behavioral changes, postoperative counseling, and follow-up. Furthermore, it is essential to verify once again whether there are uncontrolled psychiatric or eating disorders.

Medical Assessment

The medical assessment involves collecting information on demographics (e.g., educational level, intoxications), anthropometry, pubertal development, growth assessment, medical history, comorbidities, and medication use. Furthermore, blood and urine sampling will be performed to assess obesity-related comorbidities. Regarding the radiological work-up, an ultrasound of the liver will be made to determine if there is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and a DEXA scan will be made to evaluate bone health and body composition. The adolescents will also be asked to fill in questionnaires regarding quality of life (RAND-36, Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Kids, Kidscreen-27), depression and anxiety symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder questionnaire), sleep behavior (Epworth Sleepiness Scale), and reflux disease (GERD-Q) [26–33].

Psychological Assessment

The psychological assessment consists of two interviews performed by a pediatric psychologist. The first interview takes 60–90 min and starts with the adolescent and his/her parent(s)/caregiver(s). After approximately 30 min, the interview will continue with the adolescent alone and the parent(s)/caregiver(s) will be asked to complete several questionnaires (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning [BRIEF-2], Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL], and FEEL-KJ) [34–36]. Subsequent to the interview, the adolescent will also be asked to complete several questionnaires (Competence Experience Scale for Adolescents [CBSA], BRIEF-2, Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale [CRIES], and FEEL-KJ) [37, 38]. The topics discussed during the interview are presented in Table 2. The ultimate goal of the interview is to gain understanding of the adolescent’s and parents/caregivers’ coping skills, as well as the protective and limiting factors related to life after a bariatric procedure. Furthermore, the current state of mind and psychiatric history of the adolescent will be explored to once again determine whether there is an uncontrolled psychiatric disorder (contra-indication for bariatric surgery) as well as to assess the risk of psychiatric deterioration after surgery. The psychologist also determines whether there are specific additional needs regarding the peri- and postoperative counseling. When all the information is collected, the results will be discussed with the psychological staff.

Table 2.

Topics discussed with families during psychological assessment for bariatric surgery

| Topics discussed with parent(s)/caregiver(s) and adolescent | Topics discussed with adolescent |

|---|---|

| • Decision process for surgery and expectations after surgery (weight loss, excess skin, behavioral change, daily vitamin supplements, alcohol use) | • Psychiatric history and current psychiatric complaints (auto-mutilation, suicide, trauma) |

| • Previous treatment for obesity (how did this help, what did they learn) | • Influence of obesity on social and other aspects of life |

| • Bariatric surgery within family or friends (how did they deal with behavioral changes) | • Eating behavior (binge eating, emotion-regulated eating, weight, and body image) |

| • Expectations of the parent(s)/caregiver(s) about the support their adolescent needs after surgery (family support system) | • Social functioning (support system, dreams for the future) |

| • Medication and intoxications |

In the second interview (60 min), the results of the questionnaires will be explained, and it will be discussed whether the behavioral patterns might relate to behavior after surgery. Discrepancies between parent(s)/caregiver(s) and adolescents will also be reviewed.

Dietetic Assessment

The dietician will evaluate whether the adolescent will be eligible for bariatric surgery based on the knowledge of nutrition, awareness of their own eating pattern, eating behavior, and the presence of eating disorders (contra-indication for bariatric surgery). He or she will also assess whether the adolescent can sustain with the necessary dietary changes postoperatively. Besides this, the dietician determines whether there are specific points of attention for the peri- and postoperative care. Topics discussed during dietetic assessment are as follows:

Dietary history (what treatment took place, how did this help).

Eating pattern and choice of products.

Eating disorders and/or eating problems (binge eating, emotion-regulated eating).

Awareness of their own eating habits.

Assessing the impact of surgery on the postoperative eating pattern.

Multidisciplinary Meeting of the Team for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery

After the evaluations, the adolescents will be discussed in a meeting of the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. In this meeting, the pediatrician or care coordinator will summarize their findings. Afterwards, both the psychologist and the dietician discuss their evaluation. In the end, all the team members give an advice.

-

1.

Positive advice: the adolescent is eligible for bariatric surgery.

-

2.

Provisional negative advice: the adolescent receives a targeted advice to follow a particular trajectory or counseling in which specific points of attention should be addressed. If the counseling is followed for a specific amount of time and if the points of attention have been addressed, the adolescent will once more be discussed in the team to evaluate if he or she does now qualify for bariatric surgery.

-

3.

Negative advice: at the moment the adolescent is not eligible for bariatric surgery. Other long-term treatment is recommended before bariatric surgery can be reconsidered.

If the psychologist, bariatric surgeon, pediatrician, and dietician all give a positive advice, the adolescent is suitable for bariatric surgery. Additionally, a tailored plan will be made according to the pre- and postoperative needs of the adolescent and his or her family. In case there is a provisional negative advice or negative advice of one of the team members, the adolescent is currently not suitable for bariatric surgery.

Peri- and Postoperative Care

The peri- and postoperative care for adolescents who are undergoing bariatric surgery is provided by the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery in coordination with the team members of the multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention the adolescents participated in before surgery. The care is based on the clinical pathway for adult bariatric surgery patients of Máxima MC. Before the development of the peri- and postoperative care, the members of the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery were trained by dieticians and psychologists with expertise in adult bariatric surgery. Afterwards, the care was developed and adjusted to the needs of adolescents.

The multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery and the participating adolescents will be interviewed about their experiences regarding the peri- and postoperative care, as it is one of the aims of the TEEN-BEST study to assess and further optimize the clinical pathway. Furthermore, the team members fill in the care process self-evaluation tool questionnaire at 1, 3, and 5 years after the start of the study [39]. The team members and the participating adolescents will also be asked about their satisfaction regarding the clinical pathway. Based on these findings, the peri- and postoperative care will be adapted and optimized.

Perioperative Care

Once an adolescent is deemed eligible for bariatric surgery, he or she receives perioperative care. This care aims to prepare the adolescent and family for the bariatric procedure and the necessary behavioral changes postoperatively.

Bariatric Surgeon. During the consultation with the bariatric surgeon, a final decision will be made regarding the type of bariatric procedure: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Together with the adolescent and his or her family, the bariatric surgeon discusses the pros and cons of each procedure. Advantages of an RYGB include more long-term weight loss, a more positive effect on DM, and fewer reflux complaints. Disadvantages of an RYGB include the occurrence of dumping syndrome, vitamin deficiencies, and internal herniations. Advantages of an SG are its technical ease and possibly fewer complications. Disadvantages of an SG are more reflux complaints and weight regain [40, 41]. Through shared decision making, an intervention that best suits the adolescent will be chosen. Informed consent will be obtained from all adolescents. If the adolescents are below the age of 16, informed consent will also be obtained from parents/legal guardians.

Dietician. The dietician will prepare the adolescents for surgery through education on nutrition, lifestyle, and practical recommendations. The adolescents need to become aware of their own eating behavior and need to create a regular and frequent eating pattern with six to nine meals every day. Additionally, attention will be given to nutrition-related complications, nutritional deficiencies, and the prevention/treatment of these complications. To prevent nutritional deficiencies, the adolescents must take daily multivitamins and calcium/vitamin D3 1,000 mg/800 IU 4 weeks prior to surgery, and they should do so for the rest of their lives. Furthermore, education is given on a very low-calorie diet, which the adolescents should start 2 weeks prior to surgery. This diet decreases the liver volume and therefore improves laparoscopic workspace and reduces postoperative complications [42]. Besides this, examples of a daily menu regarding the 2 weeks prior to surgery (very low-calorie diet), the first two weeks after surgery (liquid diet), and more than 2 weeks after surgery are given to the adolescents.

Bariatric Procedures. Adolescents in the Netherlands will undergo either an RYGB or SG, since these are the procedures with which most experience has been gained in adolescents worldwide [16, 43]. To ensure high quality of the performed procedures, surgical standard operating procedures have been written and previously published [44].

Use of Medication. During hospital stay and the first 4 weeks after surgery, the adolescents need to inject 5,000 IU dalteparin subcutaneously daily to prevent venous thromboembolisms. Besides this, the adolescents are required to take pantoprazole 40 mg daily for the first year after bariatric surgery.

Postoperative Care

After the bariatric procedure, the adolescents will participate in long-term counseling and follow-up. The follow-up consists of 5-year regular follow-up and then monitoring through primary care. In the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery, a tailored plan is made according to the needs of each adolescent and his or her family. However, there are also several regular appointments with the bariatric surgeon, pediatrician, dietician, and psychologist. In the appointments with the pediatrician and bariatric surgeon, attention will be given to anthropometric data, obesity-related comorbidities, and complications such as micronutrient deficiencies. Furthermore, the radiological work-up will assess non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, bone health, and body composition (Table 3).

Table 3.

Follow-up visits with pediatrician or bariatric surgeon

| When? | With whom? | What? |

|---|---|---|

| Two months after surgery | Bariatric surgeon | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications |

| Six months after surgery | Pediatrician | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood sampling* |

| One year after surgery | Bariatric surgeon | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood and urine sampling*, questionnaires** |

| 1.5 years after surgery | Pediatrician | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications |

| Two years after surgery | Pediatrician | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood and urine sampling*, DEXA scan |

| Three years after surgery | Pediatrician | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood and urine sampling*, ultrasound liver, questionnaires** |

| Four years after surgery | Pediatrician or bariatric surgeon | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood sampling* |

| Five years after surgery | Pediatrician or bariatric surgeon | Anthropometrics, obesity-related comorbidities, complications, blood and urine sampling*, DEXA scan, ultrasound liver, questionnaires** |

*Blood count, minerals, fats, glucose metabolism, liver and kidney enzymes, hormones, and vitamins.

**Quality of life (RAND-36, Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Kids, Kidscreen-27), depression and anxiety symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder questionnaire), sleep behavior (Epworth Sleepiness Scale), and reflux disease (GERD-Q) [26–33].

Psychological Care. In case no specific areas of concern have been identified preoperatively, the psychological care consists of one regular follow-up moment with the pediatric psychologist 6 months after surgery. At this time, screening of anxiety, depression, and eating behavior will be performed both in a clinical interview and with the same questionnaires as used previously. In case the adolescent needs additional counseling based on the opinion of the team, a tailored plan will be made for the coming years.

Dietary Care. Four regular appointments with the dietician will be scheduled in the first year after surgery. The appointments approximately take place at 3 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months after surgery. The dietician aims to improve nutritional status, increase knowledge and understanding of nutrition and lifestyle, and prevent complications (e.g., nutrition deficiencies, vomiting, dumping syndrome, passage complaints, and malabsorption). During these appointments, attention will be given to food intake and structure, behavioral change and maintenance, medication use, and managing expectations regarding weight loss. After 1 year, the dietician decides whether additional care is needed in coordination with the multidisciplinary team.

Furthermore, the adolescents will be evaluated on a regular basis in a meeting of the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery. This will be done based on the needs of the adolescent and the stakeholders involved. During this evaluation, the current care will be evaluated and adjusted according to the needs of the adolescent and his or her family. All adolescents will at least be discussed in this meeting 1 year after surgery.

Multidisciplinary Lifestyle Intervention. Before the adolescents underwent bariatric surgery, they participated in multidisciplinary lifestyle interventions. Based on the needs of the adolescent and his or her family, and in coordination with the multidisciplinary team for adolescent bariatric surgery, this care will continue. These interventions ensure long-term counseling and focus on nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and behavioral change. In these lifestyle interventions, a multidisciplinary team develops an individualized, integral treatment plan tailored to the operative situation in which individual guidance will be offered to the families.

Discussion

In this paper, the development of a clinical pathway for adolescent bariatric surgery in the Netherlands is described. Adolescent bariatric surgery is supported by several national guidelines. These guidelines emphasized the importance of a multidisciplinary eligibility assessment to adequately identify suitable adolescents [21, 45, 46]. In line with this, previous articles described eligibility criteria for adolescent bariatric surgery patients and identified essential team members [47–55]. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery guideline, which was published in 2018, identified a pediatrician, a psychologist, and a bariatric surgeon with expertise in adolescent bariatric surgery as essential team members [48]. A systematic review based on recommendation documents for bariatric surgery in adolescents concluded that there is a need for documents that describe the whole perioperative clinical pathway in detail [56]. Selection criteria alone provide limited guidance for physicians who perform or want to perform bariatric surgery on adolescents. In previous literature, the multidisciplinary eligibility assessment for bariatric surgery in adolescents was rarely described in detail [54, 55]. Therefore, in this report the development of the Dutch multidisciplinary eligibility assessment for bariatric surgery in adolescents is described in detail.

According to several guidelines, long-term multidisciplinary guidance and follow-up are essential for bariatric surgery in adolescents to reduce complications and improve outcomes [21, 45, 46]. Despite the fact that this is considered crucial, only a small amount of articles described the peri- and postoperative care of adolescent bariatric surgery patients, and the majority of the articles did not focus on long-term postoperative care and guidance [50–53, 55, 57]. A recent qualitative study on Israeli adolescents even revealed that there is a need to improve postoperative follow-up [58]. Therefore, it has been decided by the Dutch national professional associations that bariatric surgery should be integrated into a comprehensive long-term treatment and the care should be tailored to the operative situation. The description of our comprehensive clinical pathway might help other developed countries to establish or optimize their clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in adolescents.

Conclusion

Recent data suggest that adolescents with severe obesity can safely benefit from bariatric surgery when lifestyle interventions are insufficiently effective. The implementation of bariatric surgery as an integral part of a comprehensive treatment for adolescents with severe obesity requires the development of a clinical pathway with a variety of disciplines.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol of the TEEN-BEST was reviewed and approved by the medical Ethical Committee of the Máxima MC [W18.015]. Written informed consent will be obtained from participants and/or parents who will participate in the TEEN-BEST in the future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

K.G.H.P., A.C.E.V., L.J., W.K.G.L., M.K., M.C., I.R., E.J.H., E.M., R.W., L.M.W.H., W.G.G., and F.M.H.D. developed the clinical pathway. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data that will be generated or analyzed during the study will be included in future articles. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Di Cesare M, Sorić M, Bovet P, Miranda JJ, Bhutta Z, Stevens GA, et al. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: a worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization [Internet] . World obesity day 2022 – accelerating action to stop obesity. 2022. [cited 2023 February 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2022-world-obesity-day-2022-accelerating-action-to-stop-obesity [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek [Internet] . Lengte en gewicht van personen, ondergewicht en overgewicht; vanaf 1981 2022. [cited 2023 February 23]. Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/81565NED/table?ts=1553851467369

- 4. Kelly AS, Barlow SE, Rao G, Inge TH, Hayman LL, Steinberger J, et al. Severe obesity in children and adolescents: identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(15):1689–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buttitta M, Iliescu C, Rousseau A, Guerrien A. Quality of life in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a literature review. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(4):1117–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Puder JJ, Munsch S. Psychological correlates of childhood obesity. Int J Obes. 2010;34(Suppl 2):S37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rankin J, Matthews L, Cobley S, Han A, Sanders R, Wiltshire HD, et al. Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:125–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overgewicht en obesitas bij volwassenen en kinderen 2022 [cited 2023 February 23]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/overgewicht_en_obesitas_bij_volwassenen_en_kinderen/diagnostiek_ondersteuning_en_zorg_voor_kinderen_met_obesitas.html

- 9. van de Pas KGH, Lubrecht JW, Hesselink ML, Winkens B, van Dielen FMH, Vreugdenhil ACE. The effect of a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention on health parameters in children versus adolescents with severe obesity. Nutrients. 2022;14(9):1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danielsson P, Kowalski J, Ekblom Ö, Marcus C. Response of severely obese children and adolescents to behavioral treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knop C, Singer V, Uysal Y, Schaefer A, Wolters B, Reinehr T. Extremely obese children respond better than extremely obese adolescents to lifestyle interventions. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Twig G, Yaniv G, Levine H, Leiba A, Goldberger N, Derazne E, et al. Body-mass index in 2.3 million adolescents and cardiovascular death in adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. English WJ, Williams DB. Metabolic and bariatric surgery: an effective treatment option for obesity and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(2):253–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coulman KD, Blazeby JM. Health-related quality of life in bariatric and metabolic surgery. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(3):307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kyler KE, Bettenhausen JL, Hall M, Fraser JD, Sweeney B. Trends in volume and utilization outcomes in adolescent metabolic and bariatric surgery at children's hospitals. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(3):331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruiz-Cota P, Bacardí-Gascón M, Jiménez-Cruz A. Long-term outcomes of metabolic and bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity with a follow-up of at least 5 years: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(1):133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Brandt ML, Xanthakos SA, et al. Five-year outcomes of gastric bypass in adolescents as compared with adults. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shoar S, Mahmoudzadeh H, Naderan M, Bagheri-Hariri S, Wong C, Parizi AS, et al. Long-term outcome of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 950 patients with a minimum of 3 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27(12):3110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. White B, Doyle J, Colville S, Nicholls D, Viner RM, Christie D. Systematic review of psychological and social outcomes of adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery, and predictors of success. Clin Obes. 2015;5(6):312–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nederlandse vereniging voor kindergeneeskunde [Internet]. Standpunt ‘Bariatrie bij adolescenten’. 2019. [cited 2023 February 23]. Available from: https://www.nvk.nl/over-nvk/vereniging/dossiers-en-standpunten/standpunt?componentid=25329664&tagtitles=Cardiologie%2cNefrologie%252b%252526%252burologie

- 21.Behandeling van kinderen met Obesitas Indicatiestelling bariatrische chirurgie bij kinderen met obesitas. 2020. [cited 2023 February 23]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/behandeling_van_kinderen_met_obesitas/indicatiestelling_bariatrische_chirurgie_bij_kinderen_met_obesitas.html

- 22.Laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for severe obesity in teenagers: a prospective cohort study 2022 [cited 2023 23 February]. Available from: https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=NTR7382

- 23.Overgewicht en Obesitas bij volwassenen en kinderen. Overgewicht en obesitas bij kinderen: diagnostiek, ondersteuning en zorg voor kinderen met obesitas of overgewicht in combinatie met risicofactoren en/of co-morbiditeit [cited 2024 February 9]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/overgewicht_en_obesitas_bij_volwassenen_en_kinderen/diagnostiek_ondersteuning_en_zorg_voor_kinderen_met_obesitas.html

- 24. Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dutch Bariatric Psychology Workgroup [internet] Guideline bariatric psychology. [cited 2024 February 9]. Available from: https://psynip.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Richtlijn-Bariatrische-Psychologie-10-10.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ware Jr JE, Gandek B; IQOLA Project Group . The SF-36 health survey: development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA project. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23(2):49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kolotkin RL, Zeller M, Modi AC, Samsa GP, Quinlan NP, Yanovski JA, et al. Assessing weight-related quality of life in adolescents. Obesity. 2006;14(3):448–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The KIDSCREEN Group Europe [Internet] . KIDSCREEN: health related quality of life questionnaire for children and young people and their parents. [cited 2024 February 9]. Available from: www.kidscreen.org

- 29. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck depression inventory-II. SanAntonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nederlands Jeugdinstituut [Internet] . ADHD-vragenlijst (AVL). [cited 2024 February 9]. Available from: https://www.nji.nl/instrumenten/adhd-vragenlijst-avl

- 32. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, Vakil N, Halling K, Wernersson B, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(10):1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baron IS. Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychol. 2000;6(3):235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Youth & FamiliesBurlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cracco E, Van Durme K, Braet C. Validation of the FEEL-KJ: an instrument to measure emotion regulation strategies in children and adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137080–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nederlands Jeugdinstituut [Internet] . Competentiebelevingsschaal voor adolescenten (CBSA). [cited 2024 February 9]. Available from: https://www.nji.nl/instrumenten/competentiebelevingsschaal-voor-adolescenten-cbsa [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith P, Perrin S, Yule W, Hacam B, Stuvland R. War exposure among children from Bosnia-Hercegovina: psychological adjustment in a community sample. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(2):147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Depreitere R, Van Zelm R, De Bleser L, Proost K, et al. Development and validation of a care process self-evaluation tool. Health Serv Manage Res. 2007;20(3):189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chirurgische behandeling van obesitas . Operatietechniek bij volwassenen bij chirurgische behandeling van obesitas. [cited 2024 March 23]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/chirurgische_behandeling_van_obesitas/operatietechniek_bij_chirurgische_behandeling_van_obesitas/operatietechniek_bij_volwassenen_bij_chirurgische_behandeling_van_obesitas.html [Google Scholar]

- 41. van de Pas KGH, Bonouvrie DS, Janssen L, Romeijn MM, Luijten AAPM, Leclercq WKG, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy in young adults: a Dutch registry study. Obes Surg. 2022;32(3):763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Nieuwenhove Y, Dambrauskas Z, Campillo-Soto A, van Dielen F, Wiezer R, Janssen I, et al. Preoperative very low-calorie diet and operative outcome after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a randomized multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2011;146(11):1300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Olbers T, Beamish AJ, Gronowitz E, Flodmark CE, Dahlgren J, Bruze G, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe obesity (AMOS): a prospective, 5-year, Swedish nationwide study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(3):174–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bonouvrie DS, Beamish AJ, Leclercq WKG, van Mil E, Luijten A, Hazebroek EJ, et al. Laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy for teenagers with severe obesity: teen-best: study protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, Aminian A, Angrisani L, Cohen RV, et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and metabolic disorders (IFSO) indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2023;33(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022060641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Michalsky M, Reichard K, Inge T, Pratt J, Lenders C; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery . ASMBS pediatric committee best practice guidelines. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pratt JSA, Browne A, Browne NT, Bruzoni M, Cohen M, Desai A, et al. ASMBS pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery guidelines, 2018. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(7):882–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pratt JS, Lenders CM, Dionne EA, Hoppin AG, Hsu GL, Inge TH, et al. Best practice updates for pediatric/adolescent weight loss surgery. Obesity. 2009;17(5):901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Michalsky M, Kramer RE, Fullmer MA, Polfuss M, Porter R, Ward-Begnoche W, et al. Developing criteria for pediatric/adolescent bariatric surgery programs. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 2):S65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Michalsky MP, Inge TH, Teich S, Eneli I, Miller R, Brandt ML, et al. Adolescent bariatric surgery program characteristics: the teen longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery (Teen-LABS) study experience. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(1):5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alqahtani AR, Elahmedi MO. Pediatric bariatric surgery: the clinical pathway. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):910–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Davies DA, Hamilton J, Dettmer E, Birken C, Jeffery A, Hagen J, et al. Adolescent bariatric surgery: the Canadian perspective. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(1):31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ahmad N, Bawazir OA. Assessment and preparation of obese adolescents for bariatric surgery. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2016;3(2):47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Elahmedi MO, Alqahtani AR. Evidence base for multidisciplinary care of pediatric/adolescent bariatric surgery patients. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(3):266–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Childerhose JE, Alsamawi A, Mehta T, Smith JE, Woolford S, Tarini BA. Adolescent bariatric surgery: a systematic review of recommendation documents. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(10):1768–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wulkan ML, Walsh SM. The multi-disciplinary approach to adolescent bariatric surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(1):2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tashlizky Madar R, Zion Yohay N, Grinstein Cohen O, Cohen L, Newman-Heiman N, Dvori Y. Post-bariatric surgery care in Israeli adolescents: a qualitative study. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(8):1281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data that will be generated or analyzed during the study will be included in future articles. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.