Abstract

The corrosion inhibition action of Phalaris canariensis extract on 316 L stainless steel in the H2O-35 (wt%) LiCl mixture at different temperatures has been evaluated with the aid of weight loss, potentiodynamic polarization curves, linear polarization resistance and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy tests. These studies were complemented by Fourier Transformed Infrared spectroscopy, FTIR, gas/mass chromatography analytical techniques and detailed scanning electronic microscopy studies. Results have indicated that Phalaris canariensis extract is an efficient inhibitor, with an efficiency that increases with its concentration, but it decreases as the temperature increases. Phalaris canariensis extract is physically adsorbed onto stainless steel according to a Temkin type of adsorption isotherm. Phalaris canariensis extract affected both anodic and cathodic electrochemical reactions with a stronger effect on the anodic ones, acting, thus, as a mixed type of inhibitor. Main compounds contained in the Phalaris canariensis extract were palmitic and oleic acids, responsible for its inhibitory properties.

Keywords: Stainless steel, Phalaris canariensis extract, LiCl-H2O, Corrosion inhibition

Subject terms: Electrochemistry, Green chemistry

Introduction

Population growth, urban development and technological advances have triggered a growing demand for refrigeration and air conditioning systems driven for the need of maintaining controlled temperature conditions in a variety of environments and applications1. Nowadays 10% of global energy consumption (2000 TWh) is allocated to refrigeration and air conditioning systems. It is estimated that it will increase up to 6200 TWh by 20502. Conventional air conditioning and refrigeration cooling systems, based on vapor compression, have been essential in various industries. However, they require high energy consumption, and they also depend on refrigerants that emit greenhouse gases such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrocarbons (HCs)3. For this reason, the need to develop more efficient and environmentally sustainable cooling systems, such as absorption cooling systems (ACSs) arose. These systems can use low-temperature heat sources, such as waste heat from industrial processes or waste heat from engines and solar energy, reducing electricity consumption and can use refrigerant fluids with low environmental impact, such as ammonia/water (NH3/ H2O) minimizing greenhouse gases. Despite their advantages, ACSs have a low coefficient of performance (COP) compared to conventional vapor compression cooling systems4,5.

In recent decades, different authors have investigated new pairs of refrigerant/absorber fluids to improve the COP in ACSs. Absorbents of hygroscopic salts, such as LiBr, LiCl and CaCl2, have high effectiveness and minimal pressure loss. However, the use of these absorbents causes crystallization problems in the liquid flow system that lead to the precipitation of solids that can obstruct the flow within the pipes and cause damage to the operation of the systems6. Furthermore, the presence of the halide ions such as Br− and Cl− can cause pitting corrosion in the structural materials that make up the ACSs at high operating temperatures, reducing their useful life, especially in the case of stainless steels and copper. The aggressiveness of these ions increases in the order Br− < Cl−. These effects are intensified when fresh water, used as refrigerant, is scarce and is replaced by seawater, which increases the concentration of salt in the system7. Li et al. performed a comparison of the characteristics between the LiBr/H2O working pair and the quaternary mixtures CaCl₂-LiBr-LiNO₃/H2O and CaCl₂-LiNO₃-KNO₃/H2O, resulting in a higher COP value, a decrease in the crystallization temperature, whereas and the corrosion rate of carbon steel in the CaCl₂-LiNO₃-KNO₃/H2O and CaCl₂-LiBr-LiNO₃/H2O solutions at 80 ºC were 14.31 µmy− 1 and 104.02 µmy− 1 respectively, which were higher as that obtained in the LiBr/ H2O solution, which had a value of 9.61 µmy− 1,8. Xiang et al. studied the corrosion behavior of 316 L stainless steel and copper in the mixtures LiNO3-Diethylene glycol/H2O, LiNO₃/H2O and CaCl₂/H2O, and their results indicated that the corrosion rate for stainless steel and copper in CaCl₂/H2O was much greater than in the LiNO3-Diethylene glycol/H2O and LiNO₃/H2O mixtures9. Li et al. evaluated the thermophysical properties and corrosion rate of the LiBr/H2O, CaCl₂-LiCl/H2O, CaCl₂-LiBr-LiNO₃-KNO₃/H2O, CaCl₂-LiBr-LiNO₃/H2O and CaCl₂-LiBr/H2O mixtures. The crystallization temperature, saturated vapor pressure, density and viscosity decreased, and the COP increased compared to that obtained in the LiBr/H2O solution, while the corrosion rate of carbon steel increased considerably in all mixtures containing CaCl2 at 90 °C10. Li et al. investigated the working pair LiBr–[BMIM]Cl (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride)/H2O, finding that the crystallization temperature increased and the COP was lower compared to that found in LiBr/H2O, however, the corrosion rate for both copper and carbon steel decreased in LiBr–[BMIM]Cl/H2O at 165 °C11. According to these results, the working fluids studied failed to improve COP or address crystallization and corrosion problems simultaneously.

The application of corrosion inhibitors is one of the most economical and efficient method to control the corrosion of metals in various aggressive environments. Corrosion inhibitors are specific chemical compounds that usually contain heteroatoms such as N, S, O and P, as well as conjugated double bonds of aromatic rings, which when added in minimal quantities in the aggressive environment, are adsorbed on to the metal surface, reducing corrosion rate12,13. Several compounds of natural origin present in essential oils are applicable as good metal corrosion inhibitors. For example, fatty acids found in Horse-chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum)14, Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum)15, Pomegranate (Punica granatum)15, bitter apple seeds (Citrullus colocynthis)16, and Date Palm seeds17 can form protective films on the surface of metals, which help in preventing corrosion by replacing water molecules with organic molecules contained in the oil. In addition, certain phenolic compounds and terpenes present in essential oils have also been shown to have corrosion-inhibiting properties such as Sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum)18, Epazote (Dysphania ambrosioides)19, Green cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum)20, Spearmint (Mentha viridis)21 Calamint (Calamintha)22, Oregano (Origanum compactum)23, Cinnamon24 and Thyme (Thymbra capitata)25.

Canary seeds (Phalaris canariensis L.) Phalaris canariensis L.) is a herbaceous plant belonging to the Poaceae family. These seeds are small, elliptical in shape, about 4–5 mm in length and 1.5–2 mm in width, brown or yellow in color. It is endemic from the Mediterranean region and spread to other regions of the world such as northern Africa, southern Europe, northern and southern America. Although they are mainly used as bird food, they have gained acceptance for human consumption thanks to their nutritional properties26,27. Canary seed seeds contain important chemical compounds such as fatty acids mainly palmitic, oleic and linoleic, as well as linolenic acid in smaller proportion. Furthermore, it contains phenolic compounds, carotenoids, peptides, amino acids, proteins and minerals27–29. The chemical compounds present in canary seed seeds demonstrate its ability to regulate blood sugar levels, weight control and show anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and anti-cancer properties, among others30,31. In the present study, due to its properties, Phalaris canariensis seed extract was selected to be evaluated as a corrosion inhibitor of 316 L stainless steel in LiCl/H2O solution using the weight loss and electrochemical techniques.

Experimental

Testing material

Testing material consisted of 316 L stainless steel bars of 10 mm diameter and 12 mm length. Before each electrochemical test, the specimens were polished with 600 grade SiC emery paper, rinsed with distilled water and dried with warm air.

Preparation of Phalaris canariensis seed extract

The Phalaris canariensis seeds were obtained from a local market, they were crushed in a mortar, then a 0.40 mm sieve was used to separate the fine particles. For the extraction process, a total of 400 g of Phalaris canariensis powder was used, which was distributed equally among seven cellulose extraction cartridges. These cartridges were placed in seven separate Soxhlet systems, thus ensuring simultaneous extraction. For the oil extraction, 100 ml of hexane was placed in round-bottom flasks, which were connected to each extraction tube. The systems were mounted on a heating grill at the boiling temperature of hexane (b.p. 68.7 °C), once the distillation and extraction process had started, it was maintained for 24 h. At the end of the process, the solvent in the flasks containing the extracted oil was eliminated using a rotary evaporator, leaving only the extracted Phalaris canariensis oil.

Guideline and Legislation Compliance

The authors declare that the collection of plant material (Phalaris canariensis) and experimental research complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. All authors confirm that all methods followed the relevant guidelines in the method section. All authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Electrolyte

H2O-35 (wt%) LiCl mixture was prepared by using analytical grade reagents. Phalaris canariensis extract was added to the solution at concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 ppm. The steel specimens were introduced into the electrolyte solution at temperatures of 25, 45 and 70 ºC. These temperatures will allow the inhibitor behaviour to be compared over a wide range of operating conditions typical of absorption refrigeration systems.

Chemical characterization

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis were carried out for the chemical characterization of Phalaris canariensis extract. FTIR analysis was performed using a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer in the spectral region from 4000 to 500 cm− 1. 32 scans of the sample and background were performed, using Happ-Genzel apodization and Mertz phase correction. For GC-MS analysis, an Agilent Technologies was used, equipped with an HP-5ms capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness) coupled to a 5973 N mass spectrometer as a detector.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using a potentiostat/galvanostat/ZRA 1010E Gamry Interface. A three-electrode electrochemical cell was configured consisting of a 316 L stainless steel sample prepared as a working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and an auxiliary electrode (graphite rod). These electrodes were immersed in the electrolyte solution containing H2O-35 (wt%) LiCl mixture. Open circuit potential (OCP) measurements were carried out for 3600 s, before starting the test, the electrode potential was allowed to stabilize during 15 min. For the Linear polarization resistance (LPR) measurements, steel specimens were polarized at ± 0.015 V with respect to Ecorr at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s. The polarization curves were obtained in a potential range of ± 1 V with respect to OCP at a scan rate of 1 mV/s. Passivation current density was used to calculate the corrosion current density value, icorr. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out in a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz with respect to Ecorr, an AC voltage signal of 10 mV was applied. The EIS parameters were determined by fitting the experimental results to an equivalent electric circuit by using the Zview software. All electrochemical measurements were performed in triplicate to confirm the reproducibility of the results.

Weight loss tests

Cylindrical samples having 10 mm in diameter and 12 mm in length of 316 L stainless steel were used for the weight loss tests. These samples were polished with 2000 grade SiC emery paper, rinsed with distilled water, degreased with ethanol, and dried with warm air. The weight loss value, ΔW (mg/cm2 h) was determined in an immersion period of 72 h at 25, 45 and 70 ºC, weighing the samples before and after introducing them into the H2O-35 (wt%) LiCl mixture in the absence and presence of different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract. Three specimens were used in each experiment. After weight loss tests, the samples were cleaned to remove all corrosion products according to ASTM G1. Samples were examined using a JEOL scanning electron microscopy whereas microchemical analysis was performed by using an Oxford energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) equipment.

Results

Phalaris canariensis extract characterization

FTIR analysis identified the different functional groups present in Phalaris canariensis extract (Fig. 1). Absorption peaks were observed at 2923, 2857, 1462 and 1374 cm− 1 associated with the stretching vibration of the C-H bond, which are indicative of the presence of long aliphatic chains in the fatty acids of Phalaris canariensis oil. In addition, absorption peaks detected at 1741 and 1714 cm− 1 correspond to the stretching vibration of the C = O carbonyl group. These results suggest the presence of aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, or esters. The absorption peak obtained at 1161 cm− 1 indicates the presence of the C-O bond, confirming the presence of esters, alcohols, or terpenes in the Phalaris canariensis extract. The absorption peak observed at 718 cm− 1 shows the stretching vibration of the C = C bond corresponding to the presence of alkenes or aromatic compounds.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectrum of Phalaris canariensis extract.

The results of the GC-MS analysis revealed eight components present in Phalaris canariensis extract, with their retention time (RT), chemical formula and area %, as are shown in Table 1. The main components were fatty acids such as palmitic acid (n-Hexadecanoic acid), with RT of 19.90 min and oleic acid, with RT of 21.66 min. In smaller proportion, 17-octadecynoic acid was also found. Saturated fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, have a carbon chain without double bonds, which provides a highly compact and stable molecular structure (Fig. 2). This structural stability makes saturated fatty acids less susceptible to oxidation. Its simple bonds hinder the formation of free radicals and the propagation of oxidation reactions. On the other hand, unsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic acid, contain double bonds in their carbon chain (Fig. 2). The presence of double bonds confers antioxidant properties to these fatty acids by acting as hydrogen donors in free radical neutralization reactions32–34. Furthermore, unsaturated fatty acids can act as precursors for the synthesis of endogenous antioxidant compounds, such as eicosanoids and isoprostanes, which may have antioxidant activities35. In addition, aldehydes (13-Tetradecenal and 2,4-Decadienal, (E, E)-), the alcohol cis-1,2-Cyclododecanediol and an aromatic compound Biphenylene, 1,2,4a,4b,7,8 were identified. These results are in agreement with those obtained in the FTIR analysis.

Table 1.

GC-MS analysis of Phalaris canariensis extract.

| RT (min) |

Component | Chemical formula | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.02 | Oxirane, octyl | C10H20O | 4.69 |

| 9.56 | Biphenylene, 1,2,4a,4b,7,8,8a,8b-octahydro- | C12H16 | 3.53 |

| 10.00 | Biphenylene, 1,2,4a,4b,7,8,8a,8b-octahydro- | C12H16 | 4 |

| 11.39 | 13-Tetradecenal | C14H26O | 3.49 |

| 11.86 | 2,4-Decadienal, (E, E)- | C10H16O | 6.17 |

| 12.20 | 2,4-Decadienal, (E, E)- | C10H16O | 6.82 |

| 12.81 | cis-1,2-Cyclododecanediol | C12H24O2 | 3.52 |

| 13.34 | 17-Octadecynoic acid | C18H32O2 | 3.78 |

| 19.90 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 60.2 |

| 21.66 | Oleic Acid | C18H34O2 | 100 |

Fig. 2.

GC-MS chromatogram and the chemical structure of the main components found in the Phalaris canariensis extract.

Weight loss tests

Figure 3 shows the weight loss for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture at different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract at 25, 45 and 70 ºC. Weight loss decreases as the concentration of Phalaris canariensis extract increases at all temperatures. This effect can be attributed to its ability of the inhibitor molecules to be adsorbed on the surface of the steel to form a protective layer. An increase in the temperature brings an increase in the weight loss, this indicates that increasing the kinetic energy of the molecules absorbed on the metal surface causes their desorption, the molecules that remain adsorbed continue to provide a protective layer.

Fig. 3.

Weight loss tests for 316 L type stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture in presence of Phalaris canariensis extract at different testing temperatures.

The percentage of inhibition efficiency (% I.E) at different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract in H2O-LiCl mixture at temperatures of 25, 45 and 70 ºC are shown in Fig. 4. In this case, % I.E was determined by using the data obtained from the weight loss measurements, using Eq. (1)

| 1 |

Fig. 4.

Inhibition efficiency obtained from weight loss tests for 316 L type stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture in presence of Phalaris canariensis extract at different testing temperatures.

where ΔW1 and ΔW2 represent the weight losses in the absence and presence of Phalaris canariensis extract, respectively. The inhibition efficiency improves with increases with increasing extract concentration, but decreases with increasing temperature, due to the greater number of molecules adsorbed on the steel surface.The π electrons present in the C = C double bonds of the unsaturated fatty acids contained in Phalaris canariensis extract, such as oleic acid and 17-Octadecynoic acid, eliminate free radicals generated by Cl− ions in the solution, which contributes to reducing the corrosion rate. The optimal concentration was obtained at 100 ppm at 25 °C, achieving an efficiency value of 81%.

Effect of temperature

The effect of temperature on the efficiency of Phalaris canariensis extract in terms of weight loss (ΔW), in H2O-LiCl mixture for 316 stainless steel can be observed in the Arrhenius diagram (Fig. 5). This diagram represents the relationship between log ΔW and the reciprocal of temperature (1000/T) in the absence and presence of the inhibitor. The values of the slopes of the lines obtained in the graph allow the values of the activation energy (Ea) to be determined using the Arrhenius kinetic Eq. (2)36.

| 2 |

Fig. 5.

Arrhenius plot for 316 L type stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture in presence of Phalaris canariensis extract.

where A represents the collision frequency factor of the molecules, R is the constant of the ideal gases and T is the absolute temperature. The calculation results for 25 ºC at the different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of inhibitor concentration on the activation energy values, Ea, for 316 L stainless steel in the H2O-LiCl mixture.

| Cinh (ppm) | Ea (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 5.4 |

| 5 | 6.3 |

| 10 | 6.9 |

| 25 | 7.9 |

| 50 | 8.5 |

| 100 | 9.2 |

The results in Table 2 reveal that Ea values increase with increasing inhibitor concentration. This demonstrates the strong absorption of the molecules of Phalaris canariensis extract on the surface of the steel, forming a protective layer that reduces the interaction between the metal and the corrosive medium, thus slowing the corrosion process. As the concentration of the inhibitor increases, the protective layer becomes thicker and more uniform. This adsorbed layer requires a higher activation energy to break the interactions between the inhibitor molecules and allow the steel oxidation reaction to occur. Several studies37–39 have observed similar results, supporting this relationship between the concentration of the inhibitor and the activation energy necessary for the corrosion process to take place.

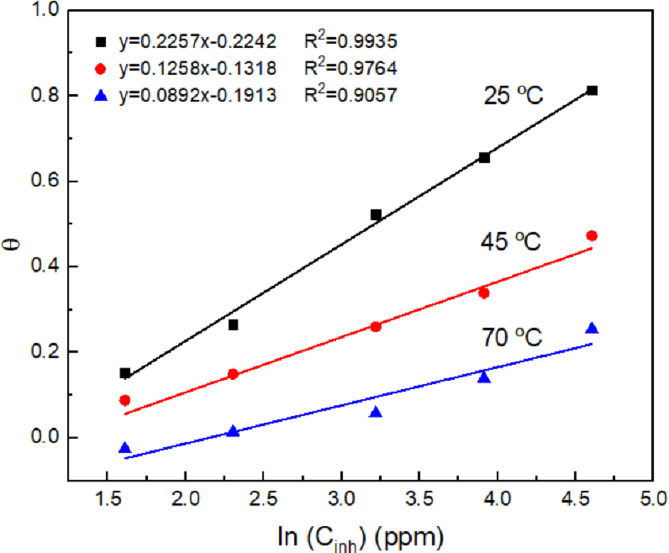

To determine the type of adsorption of Phalaris canariensis extract molecules on the steel surface, Lagmuir, Temkin, Freundlich, Flory-Huggins and Frumkim adsorption isotherms were used. The Temkin isotherm was the one that best fit the experimental data (Fig. 6). This plot shows the relationship between the degree of surface coverage (θ) of the inhibitor and the concentration of Phalaris canariensis extract at 25, 45 and 70 ºC. It is observed that as the extract concentration increases, θ increases, indicating greater adsorption of the inhibitor on the steel surface. However, as the testing temperature increases, a decrease in θ is observed, which indicates that the organic molecules present in Phalaris canariensis extract are adsorbed in a weak way. This suggests that the adsorption could be predominantly physical. The analysis of the isotherms was complemented with the Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔGads) that provides a thermodynamic measure of the spontaneity of the adsorption process. The ΔGads was calculated using Eq. (3)40.

| 3 |

Fig. 6.

Temkin adsorption isotherm for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture in presence of Phalaris canariensis extract at different testing temperatures.

where Kads, is the equilibrium constant, 55 is the water concentration in mol/L, R, is the ideal gas constant and T, temperature in K. A negative value of ΔGads indicates a process spontaneous adsorption. The calculation results obtained were − 24.42, -23.25 and − 20.8 kJ/mol at 25, 45 and 70˚C, respectively, indicating a physical adsorption characterized by weak interactions between the metal and the inhibitor, such as Van Der Waals forces. For more negative values, such as -40 kJ/mol, it suggests stronger chemical adsorption involving covalent or ionic bonds41.

Electrochemical tests

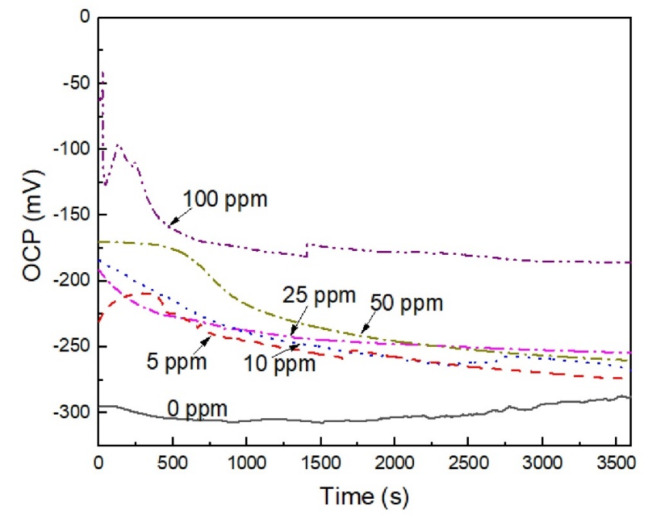

Open circuit potential (OCP)

The effect of the concentration of Phalaris canariensis extract on the variation of the OCP value with time for 316 L type stainless steel in the H2O-LiCl mixture at 25 ºC is given in Fig. 7. It is shown that the uninhibited solution, the OCP value shifts slightly towards more active values due to the dissolution of any pre-formed oxide layer, but later it shifts towards slightly nobler values, this indicates that the steel surface is forming a protective layer composed of chromium oxide (Cr₂O₃), which is very adherent and stable at room temperature (Tian 2024). With the addition of the inhibitor and the increase in its concentrations, the OCP values move to nobler values of -228 mV to -25 mV at 100 ppm, obtaining the noblest value with the addition of 100 ppm of inhibitor. The addition of Phalaris canariensis extract forms a protective layer on the surface of the steel that reduces its susceptibility to corrode. As time passes, the OCP moves towards more active values, although it is still higher than that of the uninhibited solution. This suggests that there may be a desorption of the extract from the metal surface, however, the inhibitor still protects against corrosion of the steel in the H2O-LiCl mixture.

Fig. 7.

Effect of the concentration of Phalaris canariensis extract on the variation of the OCP for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture at 25 ºC.

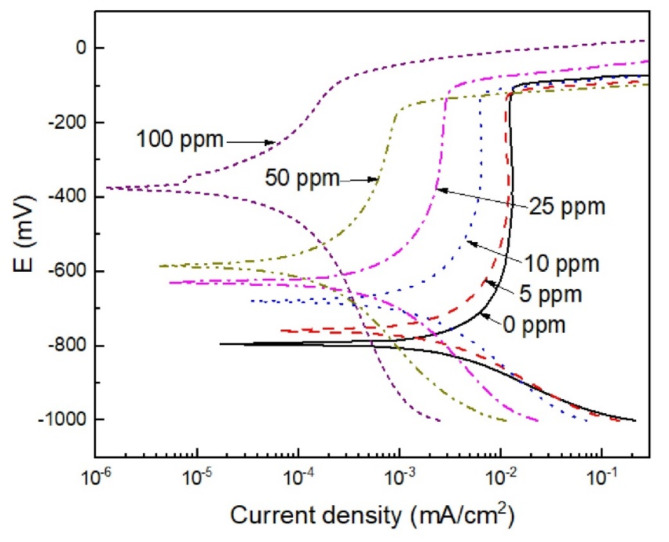

Potentiodynamic polarization measurements

Figure 8 shows the potentiodynamic polarization curves for 316 L type stainless steel in a H2O-LiCl mixture at different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract at 25 °C. Polarization curves displayed an active-passive behavior regardless of the presence of inhibitor, displaying a wide passive layer composed mainly of some iron oxides and hydroxides (FeOOH, Fe2O3 and Fe3O4), chromium oxides and hydroxides (Cr2O3, Cr(OH)3), and chlorides such as FeCl342,43. On the cathodic branch, main cathodic reactions involve oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution reactions. In absence of inhibitor, this passive zone starts around a potential value of -700 mV and finishes at a potential value close to -100 mV where the pitting potential value, Epit, was achieved. Electrochemical parameters such as free corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (icorr), cathodic Tafel slope (βc) and inhibitor efficiency (I.E.) were determined are given in Table 3. The % I.E was calculated by using Eq. (4):

| 4 |

Fig. 8.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture without and with Phalaris canariensis extract at 25 ºC.

Table 3.

Electrochemical parameters obtained from polarization curves for 316 L stainless steel in the H2O-LiCl mixture without and with inhibitor.

| Cinh (ppm) |

Ecorr (mV) |

icorr (µA/cm2) |

βa (mV/dec) |

−βc (mV/dec) |

I.E. (%) |

θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -800 | 10 ± 0.30 | -- | 114 | -- | -- |

| 5 | -750 | 7 ± 0.21 | -- | 150 | 30 | 0.3 |

| 10 | -700 | 4 ± 0.12 | -- | 200 | 60 | 0.6 |

| 25 | -640 | 2 ± 0.06 | -- | 250 | 80 | 0.8 |

| 50 | -580 | 0.30 ± 0.009 | -- | 280 | 97 | 0.97 |

| 100 | -340 | 0.10 ± 0.001 | -- | 560 | 99 | 0.99 |

where icorr1 and icorr2 represent the corrosion current density in the absence and presence of Phalaris canariensis extract, respectively. The Ecorr value shifted towards nobler values in the presence of the inhibitor, suggesting a lower tendency of the steel to corrode in H2O-LiCl mixture, whereas the Epit value was virtually unaffected, which made the passive zone to become narrower. As the concentration of the Phalaris canariensis extract increased, the icorr value decreased by two orders of magnitudes, from10 to 0.1 µA/cm2 at 100 ppm, indicating a decrease in the corrosion rate due to the formation of a protective layer on the metal surface that blocks the active sites for the protons adsorption.

The passive current density value, Ipas, decreased whereas cathodic Tafel slope showed a decrease with the addition of Phalaris canariensis extract, which indicates a decrease in the reaction rate both in the steel dissolution, the O2 reduction and hydrogen evolution reactions, demonstrating that the inhibitor affects both anodic and cathodic reactions, which confirms its nature as a mixed type inhibitor mainly anodic. On the other hand, the % I.E increased with the concentration of Phalaris canariensis extract up to 99% at a concentration of 100 ppm. At this concentration, the degree of coverage (θ) reaches 0.99, protecting a large surface area of the metal, suggesting a high adsorption of the inhibitor on the steel surface. Other authors have achieved good efficiencies using oil-derived inhibitors when added in solutions containing Cl- ions, which have proven to be effective in reducing the corrosion rate by forming a protective layer on the metal surface. Simovic et al. found that essential oil of Pinus nigra reached an efficiency of up to 97% at 200 ppm of inhibitor, reducing the corrosion rate of carbon steel in 1 M HCl, acting as a mixed-type inhibitor44. Mirinioui et al., revealed that the essential oil of Dysphania ambrosioides achieved an efficiency of 90% for 4 g/L of oil in the corrosion of mild steel C38 in 1 M HCl at 298 K. The inhibitor acted as a mixed-type inhibitor, primarily cathodic45. The study conducted by Mohamed et al. showed that the essential oil of Anethum graveolens is a mixed-type inhibitor that reduces the corrosion rate of C38 steel in 1 M HCl with an efficiency of up to 94% for 2 g/L of inhibitor at 298 K. However, the inhibition efficiency decreases as the test temperatures increase from 308 to 318, 328 and 338 K46.

Linear polarization resistance (LPR)

The results obtained from the polarization resistance (Rp) over time with LPR measurements for 316 stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture in the absence and presence of different concentrations of Phalaris canariensis extract at 25 ºC are shown in Fig. 9. According to the Stern-Geary equation, the corrosion current density, icorr is inversely proportional to Rp. According to the results obtained from the polarization curves, a decrease in icorr was observed as the inhibitor concentration is increased. These results are consistent with the LPR measurements, since Rp increases proportionally with the inhibitor concentration. In the uninhibited solution, an Rp value of 1 × 104 ohm cm2 was recorded, while, with the highest inhibitor concentration of 100 ppm, this value increased significantly up to 5 × 106 ohm cm2. The increase in Rp is attributed to the formation of a protective layer due to the adsorption of Phalaris canariensis extract on the steel surface. Furthermore, over time, an increase in Rp is observed, which is attributed to the continuous adsorption of the inhibitor on the metal surface that can lead to an increase in the thickness of the protective layer.

Fig. 9.

Polarization resistance over time for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture without and with Phalaris canariensis extract at 25 ºC.

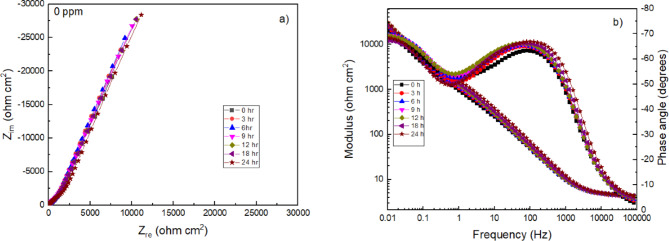

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

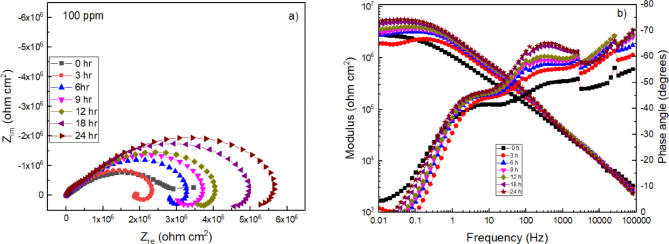

EIS measurements were performed during a period of 24 h to obtain more information on the corrosion mechanism of 316 stainless steel in a H2O-LiCl mixture in the absence of the Phalaris canariensis extract (Fig. 10) and at a concentration of 100 ppm (Fig. 11), which was found to be the most efficient with the techniques described above. In the Nyquist diagram, in the absence of the inhibitor (Fig. 10a), in all spectra it is observed that, at high frequencies, a capacitive semicircle is formed. At low and intermediate frequencies, the formation of a second semicircle is distinguished. This indicates that the corrosion mechanism is controlled by charge transfer on the metal surface. The diameter of the high frequency semicircle increases as the immersion time increases. When stainless steel is exposed to a chloride solution, Cl− ions can penetrate and destabilize the passive layer formed by iron and chromium oxides/hydroxides47. As a result, a greater number of defects are formed in the passive layer, allowing for greater interaction between the metal and the electrolyte. This interaction leads to an increase in the electrical resistance of the system, as the opposition to current flow through the metal/solution interface is increased. Therefore, the electrical impedance of the system increases, which is reflected in an increase in the diameter of the semicircles.

Fig. 10.

(a) Nyquist and (b) Bode plots for 316 L stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture without inhibitor at 25 ºC.

Fig. 11.

(a) Nyquist and (b) Bode plots for 316 L type stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture with Phalaris canariensis extract at 25 ºC.

The chemical reactions associated with the corrosion of stainless steel in the presence of chlorides are given in Eq. (5) and Eq. (6).

| 5 |

| 6 |

Fe(OH)3 and Cr(OH)3 formed through the above reactions can undergo dehydration to transform into FeOOH and CrOOH, respectively Eq. (7) and Eq. (8). These dehydrated compounds can be further dehydrated, leading to the formation of Fe3O2 and Cr2O3 Eq. (9) and Eq. (10).

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

Both FeOOH and CrOOH as well as Fe2O3 and Cr2O3 precipitate and accumulate as scales, constituting the main corrosion products on stainless steel42,43. The Bode diagrams in modulus and phase angle format in the absence of the inhibitor are shown in Fig. 10b. The impedance modulus at low frequencies shows an increase as the immersion time progresses, where it reaches a value of 3 × 104 ohm cm2 at 24 h. This increase is attributed to the formation and growth of layers of corrosion products, such as hydroxides (Fe(OH)3 and Cr(OH)3) and oxides (Fe2O3 and Cr2O3). On the other hand, the phase angle values showed a single broad peak from 1 to 1000 Hz which was slightly increasing and broadening with a value of -66º at 100 Hz to 24 h. This response may be due to the formation of Fe and Cr hydroxide and oxide layer on the steel surface which exhibit capacitive properties.

With the addition of the inhibitor, a modification in the electrochemical response is observed in the Nyquist diagram (Fig. 11a). All spectra show the formation of capacitive semicircles at high frequencies and the formation of an inductive loop at ilow frequencies. The presence of the inductive loop is related to the adsorption of intermediate species on the steel surface48.

The main intermediate species formed on the stainless steel exposed in the LiCl solution are detailed in Eq. (11) and Eq. (12):

| 11 |

| 12 |

These equations represent the dissolution processes of iron in the presence of chloride ions49. The inhibitor can influence the formation of FeCl₂ and FeCl₃, by adsorbing on the steel surface, reducing the corrosion of the material. The adsorption of the inhibitor from the solution onto the steel metal replacing the adsorbed water molecules which goes to the solution is given by following reaction50:

| 13 |

Thus, the adsorption/desorption of species given by Eqs. (11)-(12) give rise to the observed inductive loops in Fig. 11a. The diameter of the inductive loop increases as the immersion time increases. Initially, the exposure of the steel to the H2O-LiCl solution causes the dissolution of the metal, as the chloride ions attack the protective passive layer. When the inhibitor is added, it is adsorbed on the steel surface, forming a new protective layer by the organic compounds of the inhibitor. Over time, this layer becomes thicker, providing greater protection to the steel. This same phenomenon is reflected in the Bode diagrams, Fig. 11b, the impedance modulus at low frequencies shows an increase as the immersion time progresses, where it reaches a value of 5 × 106 ohm cm2 at 24 h. This increase indicates the formation of a protective layer of the inhibitor that minimizes the permeability, blocking the penetration of the chloride ions present in the solution. The phase angle shows the formation of two peaks, one present at 260 Hz, with a value of -65º, which could be related to the adsorption of the inhibitor on the steel surface, while the other present at 2 Hz, with a phase angle value of -45º could be associated with the capacitive behavior at the metal-solution interface.

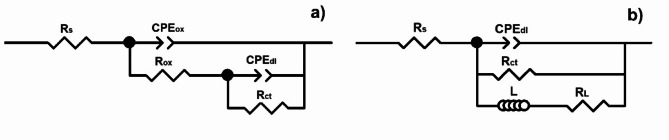

The EIS parameters of the uninhibited solution inhibitor and for an inhibitor concentration of 100 ppm were simulated by using equivalent electrical circuits as shown in Fig. 12. In these circuits, Rs, represents the solution resistance, Rct, is the charge transfer resistance, CPEdl is a phase element constant replacing the electrochemical double layer capacitance (Cdl), to describe the non-ideal behavior of the electrode-electrolyte interface. The impedance of a CPE is described by Eq. (14):

| 14 |

Fig. 12.

Equivalent electric circuits used to simulate the EIS data for solution containing (a) 0 and (b) 100 ppm of inhibitor.

where ZCPE, is the impedance of CPE, Y0 is the proportionality constant, j is an imaginary unit, ω is the angular frequency and n is a parameter of the heterogeneity and roughness of the surface51. Rox and CPEox are the resistance and the constant phase element that describe the electrochemical behavior of the layer of oxides and hydroxides, or in general, any corrosion products that is formed on the steel surface. L represents the inductive element and RL represents its resistance. The presence of the inductance in the system is indicative of the adsorption and desorption of the intermediate species such as FeCl₂ and FeCl₃.

Tables 4 and 5 show the electrochemical parameters obtained by simulating the EIS data of the uninhibited solution and for an inhibitor concentration of 100 ppm, respectively. The efficiency of the Phalaris canariensis extract (I.E.%) was evaluated by Eq. (15):

| 15 |

Table 4.

Electrochemical parameters used to fit the EIS results for the uninhibited solution.

| Tiempo (h) |

Chi-Sqr |

R

s

(ohm cm2) |

R

ct

(ohm cm2) |

CPEdl (µFcm− 2) |

n dl |

R

ox

(ohm cm2) |

CPEox (µF/cm2) |

n ox |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.16 × 10− 3 | 4.29 | 1.19 × 103 | 1.42 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 1.92 × 104 | 2.49 × 10− 4 | 0.7 |

| 3 | 4.17 × 10− 4 | 4.22 | 1.53 × 103 | 1.28 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 2.31 × 104 | 2.36 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 4.97 × 10− 4 | 4.20 | 1.73 × 103 | 1.25 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 2.99 × 104 | 2.12 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

| 9 | 5.78 × 10− 4 | 4.21 | 1.92 × 103 | 1.21 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 2.67 × 104 | 1.91 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

| 12 | 6.35 × 10− 4 | 4.28 | 2.17 × 103 | 1.19 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 2.77 × 104 | 1.80 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

| 18 | 1.39 × 10− 3 | 4.27 | 2.11 × 103 | 1.05 × 10− 4 | 0.8 | 2.46 × 104 | 2.26 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

| 24 | 1.15 × 10− 3 | 4.26 | 2.37 × 103 | 8.46 × 10− 5 | 0.8 | 2.83 × 104 | 2.01 × 10− 4 | 0.8 |

Table 5.

Electrochemical parameters used to fit the EIS data for an inhibitor concentration of 100 ppm.

| Tiempo (h) |

Chi-Sqr |

R

s

(ohm cm2) |

R

ct

(ohm cm2) |

CPEdl (µFcm− 2) |

n dl |

R

L

(ohm cm2) |

I.E. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.73 × 10− 3 | 5.37 | 1.29 × 106 | 2.02 × 10− 7 | 0.6 | 1.12 × 106 | 99 |

| 3 | 8.89 × 10− 3 | 5.29 | 1.98 × 106 | 1.15 × 10− 7 | 0.6 | 1.38 × 106 | 99 |

| 6 | 6.59 × 10− 3 | 6.27 | 1.38 × 106 | 9.48 × 10− 8 | 0.6 | 1.49 × 106 | 99 |

| 9 | 7.92 × 10− 3 | 6.28 | 2.75 × 106 | 8.30 × 10− 8 | 0.6 | 1.44 × 106 | 99 |

| 12 | 8.09 × 10− 3 | 4.35 | 3.03 × 106 | 7.72 × 10− 8 | 0.6 | 1.55 × 106 | 99 |

| 18 | 1.22 × 10− 2 | 4.35 | 3.35 × 106 | 5.40 × 10− 8 | 0.7 | 1.81 × 106 | 99 |

| 24 | 1.38 × 10− 2 | 5.39 | 4.21 × 106 | 3.09 × 10− 8 | 0.8 | 4.47 × 106 | 99 |

where Rct1 and Rct2 denote the charge transfer resistance in the presence and absence of Phalaris canariensis extract, respectively. From Tables 4 and 5 it can be seen that the Rs values virtually remains unaffected neither by the presence of the inhibitor nor by the elapsing time. By containing fatty acids, the inhibitor creates a hydrophobic barrier that hinders the access of corrosive species such as O2− and Cl− ions, thus reducing the ionic conductivity in the solution. The Rct values increase in the presence of the inhibitor. Under uninhibited solution conditions, Rct values increase with immersion time reaching a value of 2.37 × 103 ohm cm2 at 24 h, while, by adding the inhibitor, the Rct values increase to 4.21 × 106 ohm cm2. This is due to the lowering of metal ions such as Fe2+ and Cr3+ crossing the double electrochemical layer due to a decrease in the metal dissolution rate with a decrease in the double layer conductivity, and thus, an increase in its resistance. The CPEdl values decrease both in the absence and presence of the inhibitor as the immersion time increases. In the absence of the inhibitor in Table 4, CPEdl values from 1.42 × 10− 4 µFcm− 2 to 8.46 × 10− 5 µFcm− 2 can be observed due to the adsorption of the inhibitor on to the steel surface which replaces the water molecules. In the presence of the inhibitor in Table 5, the CPEdl values decrease even more compared to the solution without inhibitor from 2.02 × 10− 7 µFcm− 2 to 3.09 × 10− 8 µFcm− 2. This adsorption displaces the water molecules and ions present in the solution [52]. Since the inhibitor molecules are much bigger than water molecules, the double electrochemical layer thickness increases, decreasing its capacitance since this is inversely proportional to its thickness52. The ndl and nox values are close to 1 when the inhibitor is present, indicating a smoother steel surface due to a decreased steel dissolution rate, while the n value close to 0.5 is related to a rougher surface due to a higher steel corrosion rate.

In absence of the inhibitor, the corrosion products resistance value, Rox, increased with immersion time due to the formation of Fe and Cr oxides and hydroxides on the steel surface and the increase in its thickness, and therefore CPEox decreases since they are inversely proportional. On the other hand, the RL values increase with immersion time due to the formation of the protective layer that decreases the speed of the electrochemical reactions, which is reflected in an increase in the inductive resistance of the system, since aggressive ions have more difficulty reaching the metal surface. The % E.I. reached a value of 99%, as evidenced by the results of polarization curves. These results indicate that the Phalaris canariensis extract is effective in protecting steel from corrosion in H2O-LiCl mixture.

Surface analysis

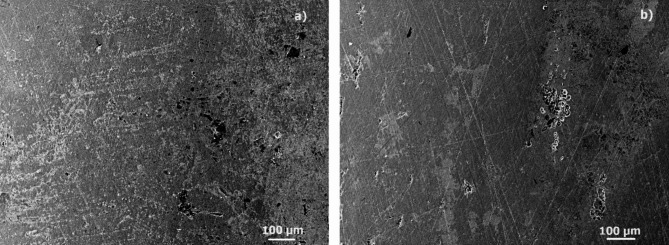

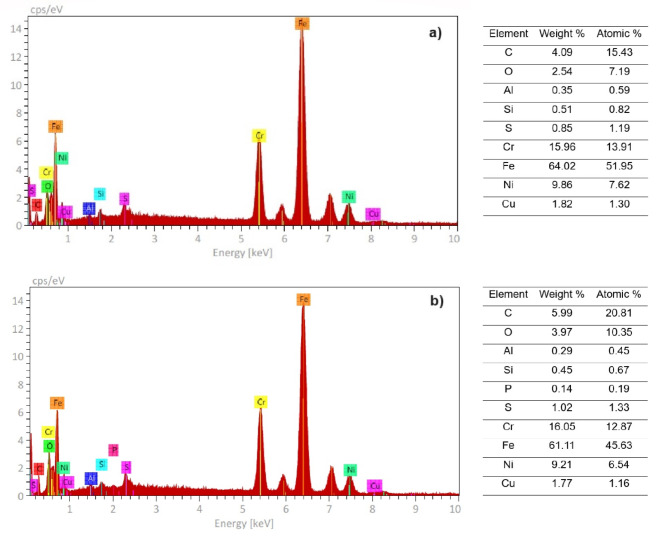

Micrographs of corroded specimens in the absence and presence of 316 L type stainless steel after immersion in a H2O-LiCl mixture are given in Fig. 13 whereas microchemical analysis performed on to the corrosion products is given in Fig. 14. In the images for the uninhibited solution at 25 ºC (Fig. 13a), a surface with the presence of black spots that could be Fe or Cr oxides is observed. For specimen corroded in the presence of 100 ppm of inhibitor at 25 ºC (Fig. 13b), polishing marks are observed, indicating less degradation of the steel, in addition to the presence of some deposits on the metal surface. In both cases the presence of some pitts, characteristic of this type of steel when corroded in Cl-containing environments, can be seen, although they are present in a higher number in the uninhibited solution. On the other hand, EDS chemical analysis carried out in both specimens, Fig. 14, show the presence of the chemical elements present in the steel such as Fe, Cr, Ni and C, however, the intensity that corresponds to C in the steel corroded in presence of inhibitor, Fig. 14b, is higher than that present on the steel corroded in the absence of the inhibitor. This indicates that the inhibitor was adsorbed onto the steel surface, since it is an organic compound, and, just as shown in the chemical structure of the main compounds found in the inhibitor, C is one of the main chemical elements contained within their chemical structure.

Fig. 13.

SEM images (x100 magnification) for 316 L type stainless steel after immersion in H2O-LiCl mixture containing (a) 0 and (b) 100 ppm of inhibitor at 25 ºC.

Fig. 14.

EDS analysis of corrosion products formed on 316 L type stainless steel after immersion in H2O-LiCl mixture containing (a) 0 and (b) 100 ppm of inhibitor at 25 ºC.

Conclusions

The present study evaluated the corrosion of 316 stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixture at different temperature conditions and in the presence of Phalaris canariensis extract. The results obtained showed that the inhibitor is physically adsorbed on the steel surface, mainly following the Temkin isotherm. The capacity of the inhibitor to adsorb and form a protective layer on the metal surface decreases with increasing solution temperature. The inhibitor efficiency increased with its concentration, and maximum inhibition efficiency was 99% at a concentration of 100 ppm at 25 ºC. Agreement was found between the inhibition efficiencies calculated by polarization curves and EIS. The polarization resistance and the charge transfer resistance increased in the presence of the inhibitor as the immersion time increased, due to the gradual formation of a thicker protective layer. Inhibitor affected both the anodic and cathodic electrochemical reactions with a more pronounced effect on the anodic one. This indicated that the inhibitor acts as a mixed type inhibitor, mainly anodic. GC-MS analysis revealed that the main compounds responsible for the inhibition properties are palmitic acid and oleic acid.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and J.G.G.R.; methodology, E.G., A.K.G.L and J.G.G.R; software, R.L.S and A.M.R.A; validation, R.L.S and A.M. R. A.; investigation, E.G.; writing and editing, A.K.G.L and J.G.G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit sectors.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1. Ali, M., Habib, M. F., Sheikh, N. A., Akhter, J., & Gilani, S. I. U. H. Experimental investigation of an integrated absorption- solid desiccant air conditioning system. Appl. Therm. Eng.. 203, 117912. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.117912 (2022).

- 2. Woods, J. et al. Humidity’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions from air conditioning. Joule 6 (4), 726–741. 10.1016/j.joule.2022.02.013 (2022).

- 3. Vuppaladadiyam, A. K. et al. Progress in the development and use of refrigerants and unintended environmental consequences. Sci Total Environ. 823, 153670. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153670 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Hosseini, P. Deep-learning neural network prediction of a solar-based absorption chiller cooling system performance using waste heat. Sustain. Energy Technol.53, 102683. 10.1016/j.seta.2022.102683 (2022).

- 5. Nikbakhti, R., Wang, X., Hussein, A. K., & Iranmanesh, A. Absorption cooling systems – Review of various techniques for energy performance enhancement. Alex. Eng. J.59 (2), 707–738. 10.1016/j.aej.2020.01.036 (2020).

- 6. Elsafi, A. M., & Bahrami, M. A novel spherical micro-absorber for dehumidification systems. In. J. Refrig. 157, 73–85. 10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2023.11.006 (2024).

- 7. Du, S., Xu, Z., Wang, R., & Yang, C. Development of direct seawater-cooled LiBr–H2O absorption chiller and its application in industrial waste heat utilization. Energy. 294, 130816. 10.1016/j.energy.2024.130816 (2024).

- 8. Li, Y., Li, N., Luo, C., & Su, Q. Study on a Quaternary Working Pair of CaCl2-LiNO3-KNO3/H2O for an Absorption Refrigeration Cycle. Entropy. 21 (6), 546. 10.3390/e21060546 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Xiang, F., Luo, C., & Su, Q. Crystallization Temperature, Vapor Pressure, Density, Viscosity, Specific Heat Capacity, and Corrosivity of the LiNO3-DEG/H2O Ternary System. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 68 (2), 303–313. 10.1021/acs.jced.2c00395 (2023).

- 10. Li, Y., Li, N., Luo, C., & Su, Q. Study on CaCl2-LiCl/H2O as working pair of absorption refrigeration cycle. CIESC J. 70 (9), 3483–3494. 10.11949/0438-1157.20190169 (2019).

- 11. Li, Y., Li, N., Luo, C., & Su, Q. Thermodynamic performance of a double-effect absorption refrigeration cycle based on a ternary working pair: Lithium Bromide + Ionic Liquids + Water. Energies. 12 (21), 4200. 10.3390/en12214200 (2019).

- 12. Assad, H., & Kumar, A. Understanding functional group effect on corrosion inhibition efficiency of selected organic compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 344, 117755. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117755 (2021).

- 13. Wang, J. et al. Frontiers and advances in N-heterocycle compounds as corrosion inhibitors in acid medium: Recent advances. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 321, 103031. 10.1016/j.cis.2023.103031 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Varvara, S. et al. Multiscale electrochemical analysis of the corrosion control of bronze in simulated acid rain by horse-chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum L.) extract as green inhibitor. Corros. Sci. 165, 108381. 10.1016/j.corsci.2019.108381 (2020).

- 15. Moustafa, A. H. E., Abdel-Rahman, H. H., Awad, M. K., Naby, A. A. N. A., & Seleim, S. M. Molecular dynamic simulation studies and surface characterization of carbon steel corrosion with changing green inhibitors concentrations and temperatures. Alex. Eng. J. 61 (3), 2492–2519. 10.1016/j.aej.2021.07.041 (2022).

- 16. Doumane, G. et al. Corrosion inhibition performance of citrullus colocynthis seed oil extract as a mild steel in 1.0 M HCl acid using various solvants such as petroleum ether (CSOP) and cyclohexan (CSOC) polymerics. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 155, 111042. 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111042 (2023).

- 17. Mohammed, N. J., & Othman, N. K. Date Palm Seed Extract as a Green Corrosion Inhibitor in 0.5 M HCl Medium for Carbon Steel: Electrochemical Measurement and Weight Loss Studies. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 15 (10), 9597–9610. 10.20964/2020.10.45 (2020).

- 18. Ansari, A. et al. Experimental, Theoretical Modeling and Optimization of Inhibitive Action of Ocimum basilicum Essential Oil as Green Corrosion Inhibitor for C38 Steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 Medium. Chemistry Africa 5 (1), 37–55. 10.1007/s42250-021-00289-x (2021).

- 19. Daoudi, W. et al. Essential oil of Dysphania ambrosioides as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl solution. J. Mol. Liq. 363, 119839. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119839 (2022).

- 20. Tarfaoui, K. et al. Natural Elettaria cardamomum Essential Oil as a Sustainable and a Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in 1.0 M HCl Solution: Electrochemical and Computational Methods. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 7 (4). 10.1007/s40735-021-00567-8 (2021).

- 21. Lazrak, J. et al. Mentha viridis oil as a green effective corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M HCl medium. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib.9 (4), 1580–1606. 10.17675/2305-6894-2020-9-4-25 (2020).

- 22. Aatiaoui, A. E. et al. Anticorrosive potential of essential oil extracted from the leaves of Calamintha plant for mild steel in 1 M HCl medium. J. Adhes. Sci.Technol. 37 (7), 1191–1214. 10.1080/01694243.2022.2062956 (2022).

- 23. Lazrak, J. et al. Origanum compactum essential oil as a green inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid solution: Experimental and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 7486–7493. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.233 (2021).

- 24. Lazrak, J. et al. Valorization of Cinnamon Essential Oil as Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in 1.0 M Hydrochloric Acid Solution. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 57 (3), 360–373. 10.3103/s1068375521030108 (2021).

- 25. Chraka A. et al. Identification of Potential Green Inhibitors Extracted from Thymbra capitata (L.) Cav. for the Corrosion of Brass in 3% NaCl Solution: Experimental, SEM–EDX Analysis, DFT Computation and Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 6 (3). 10.1007/s40735-020-00377-4 (2020).

- 26. Perera, S. P., Hucl, P., L’Hocine, L., & Nickerson, M. T. Microstructure and distribution of oil, protein, and starch in different compartments of canaryseed (Phalaris canariensis L.). Cereal Chem. 98 (2), 405–422. 10.1002/cche.10381 (2020).

- 27. Patterson, C. A., Malcolmson, L., Lukie, C., Young, G., Hucl, P. Glabrous canary seed: a novel food ingredient. Cereal Foods World. 63, 194–200. 10.1094/cfw-63-5-0194 (2018).

- 28. Escalante, F., Castellanos, A., Castañeda, E., Chel, L., & Betancur, D. Development of Low Glycemic Index Pancakes Formulated with Canary Seed (Phalaris Canariensis) Flour. Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 79 (1), 120–126. 10.1007/s11130-023-01138-7 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Juárez, N. et al. Nutritional, physicochemical and antioxidant properties of sprouted and fermented beverages made from Phalaris canariensis seed. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 58 (10), 5299–5310. 10.1111/ijfs.16637 (2023).

- 30. Park, L. et al. Effects of canary seed on two patients with disseminated granuloma annulare. Dermatology Reports 15, 9614. 10.4081/dr.2023.9614 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. Urbizo-Reyes, U. et al. Canary Seed (Phalaris canariensis L.) Peptides Prevent Obesity and Glucose Intolerance in Mice Fed a Western Diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (23), 14927. 10.3390/ijms232314927 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Machado, M., Rodriguez-Alcalá, L. M., Gomes, A. M., & Pintado, M. Vegetable oils oxidation: mechanisms, consequences and protective strategies. Food Rev. Int. 39(7), 4180–4197. 10.1080/87559129.2022.2026378 (2022).

- 33. Musakhanian, J., Rodier, J. D. & Dave, M. Oxidative Stability in Lipid Formulations: a Review of the Mechanisms, Drivers, and Inhibitors of Oxidation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 23, 151. 10.1208/s12249-022-02282-0 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Rustan, A. & Drevon, C. Fatty Acids: Structures and Properties. eLS. 9780470015902. 10.1038/npg.els.0003894 (2005).

- 35. Davinelli, S., Medoro, A., Intrieri, M., Saso, L., Scapagnini, G., & Kang, J. X. Targeting NRF2–KEAP1 axis by Omega-3 fatty acids and their derivatives: Emerging opportunities against aging and diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 193, 736–750. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.11.017 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36. Ituen, E., Mkpenie, V., Yuanhua, L., & Singh, A. Inhibition of erosion corrosion of pipework steel in descaling solution using 5-hydroxytryptamine-based additives: Empirical and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1204, 127562. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.127562 (2020).

- 37. Al-Amiery, A. A., Betti, N., Isahak, W. N. R. W., Al-Azzawi, W. K., & Nik, W. M. N. W. Exploring the Effectiveness of Isatin–Schiff Base as an Environmentally Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in Hydrochloric Acid. Lubricants. 11(5), 211. 10.3390/lubricants11050211 (2023).

- 38. Ikeuba, A. I. et al. Experimental and theoretical evaluation of Aspirin as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic medium. Results In Chemistry. 4, 100543. 10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100543 (2022).

- 39. Masaret, G. S., & Jahdaly, B. A. A. Inhibitive and adsorption behavior of new thiazoldinone derivative as a corrosion inhibitor at mild steel/electrolyte interface: Experimental and theoretical studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 338, 116534. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116534 (2021).

- 40. Shahzad, K. et al. Electrochemical and thermodynamic study on the corrosion performance of API X120 steel in 3.5% NaCl solution. Scientific Reports. 10 (1). 10.1038/s41598-020-61139-3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Mohamad, S. I., Younes, G. & El-Dakdouki, M. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in acidic solutions using Phaseolus vulgaris L. extract as a green inhibitor. Mor. J. Chem. 12 (2), 473–492. 10.48317/IMIST.PRSM/morjchem-v12i2.45865 (2024).

- 42. Chen, X., Liu, H., Sun, X., Zan, B., & Liang, M. Chloride corrosion behavior on heating pipeline made by AISI 304 and 316 in reclaimed water. RSC Adv. 11 (61), 38765–38773. 10.1039/d1ra06695a (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43. Xu, X., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Smith, K., & Cui, Y. Corrosion of stainless steel valves in a reverse osmosis system: Analysis of corrosion products and metal loss. Eng. Fail. Anal. 105, 40–51. 10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.06.026 (2019).

- 44. Simović, A. R., Grgur, B. N., Novaković, J., Janaćković, P., & Bajat, J. Black Pine (Pinus nigra) Essential Oil as a Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel. Metals 13 (3), 508. 10.3390/met13030508 (2023).

- 45. Mirinioui, A., Attari, H. E., Fdil, R., Zefzoufi, M., & Jorio, S. Dysphania ambrosioides Essential Oil: An Eco-friendly Inhibitor for Mild Steel Corrosion in Hydrochloric and Sulfuric Acid Medium. J. Bio- Tribo-corros. 7 (4). 10.1007/s40735-021-00584-7 (2021).

- 46. Mohamed, Z. Experimental, Quantum Chemical and Molecular Dynamic Simulations Studies on the Corrosion Inhibition of C38 Steel in 1 M HCl by Anethum graveolens Essential Oil. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 11 (10), 1426–1451 (2019).

- 47. De Souza, L. M., Pereira, E., Da Silva Amaral, T. B., Monteiro, S. N., & De Azevedo, A. R. G. (2024). Corrosion Study on Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S31803 Subjected to Solutions Containing Chloride Ions. Materials. 17 (9), 1974. 10.3390/ma17091974 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48. Islam, M. M., Pojtanabuntoeng, T., Gubner, R., & Kinsella, B. Electrochemical investigation into the dynamic mechanism of CO2 corrosion product film formation on the carbon steel under the water-condensation condition. Electrochim. Acta. 390, 138880. 10.1016/j.electacta.2021.138880 (2021).

- 49. Parapurath, S., Ravikumar, A., Vahdati, N., & Shiryayev, O. Effect of Magnetic Field on the Corrosion of API-5L-X65 Steel Using Electrochemical Methods in a Flow Loop. Appl. Sci. 11 (19), 9329. 10.3390/app11199329 (2021).

- 50. Harvey, T.J., Walsh, F.C., & Nahlé, A.H. A review of inhibitors for the corrosion of transition metals in aqueous acids. J. Mol. Liq. 266 (15), 160–175. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.06.014 (2018).

- 51. Kherraf S. et al. Lavandula Stoechas as a Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Monel 400 in Sulfuric Acid: Electrochemical, Gravimetrical, and AFM Investigations. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 42 (8). 10.30492/IJCCE.2023.563710.5656 (2023).

- 52. Salman, M. et al. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of substituted triazines and their corrosion inhibition behavior on N80 steel/acid interface. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57 (5), 2157–2172. 10.1002/jhet.3936 (2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.