Abstract

Surgical success includes a planned incision, achieving haemostasis, good mechanical closure and optimal maintenance of the surgical wound. New materials, as tissue adhesives, have been suggested as substitutes for sutures, to overcome their disadvantages. This study aimed at gathering the differences of using surgical adhesives in oral surgery compared with the conventional method of using sutures as a wound closure technique. PRISMA analyses, PICO criteria and PubMed/Medline database, EBSCO and Cochrane Library were used for research. Inclusion criteria included prospective, randomized controlled trials and case–control studies published in English with full access, where clinical advantages and demerits/limitations were reported in patients who underwent oral surgical incisions, without time restrictions. Exclusion criteria comprised literature with lower level of evidence. A total of 15 studies were assessed and analysed 15 parameters as alternatives to sutures (100%), cost‐effectiveness (6,6%), postoperative pain (53,3%), time consumption (73,3%), haemostasis (46,6%), homeostasis (13,3%), aids healing (26,6%), tissue inflammation (26,6%), safety (6,6%), graft dimension (3,13), biocompatibility (13,3%), adhesion to tissue (6,6%), bacteriostatic effect (20%), oedema (13,3%) and ease of application (26,6). Selected articles' results indicate that surgical glues can be a suitable alternative and/or adjuvant to oral sutures, presenting numerous advantages.

Keywords: cyanoacrylates, fibrin sealant, oral mucosa, sutures, wound closure

1. INTRODUCTION

Incision is a basic step for surgical procedures. 1 Achieving haemostasis and good mechanical closure of the surgical wound is of paramount importance in the field of surgery, 2 as well as optimal maintenance of the surgical area, being them the most important factors to affect proper wound healing and surgical success. 1 Therefore, a carefully planned surgery needs proper immobilization of the healing area. 3 This involves choosing a synthesis technique from the wide range of existing ones. Regardless, the basic goals are the same: to minimize ‘dead space’ and the risk of infection, and to have an appropriate approximation of wound edges, so acceptable aesthetics and function are achieved. 4 For this, a close approximation of wound edges with appropriate means and methods is needed to accomplish healing by primary intention, which is preferable, because there is less scarring, quicker healing and reduced discomfort for the patient. 5 Complications of healing after surgery may result because of any of the following reasons or a combination of them: inadequate preoperative assessment, faulty/traumatic surgery and/or inadequate postoperative care. 3

Sutures have remained the mainstay of wound and bleeding management for centuries. 2 , 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 Despite that, there are disadvantages such as execution time, need for technical skill, difficult access to posterior regions of the oral cavity and the trauma caused by needle penetration. 6 , 7 , 8 For suturing, there are numerous materials for flap synthesis, such as silk, nylon, steel, catgut, polyglycolic‐polylactic acid derivatives, amongst others. 9 Braided silk is the most commonly used material for closing oral wounds. 6 , 9 It allows an easy manipulation and good knot security and is economical. However, non‐resorbable sutures do have some disadvantages for instance needing a second appointment to remove the suture, being an additional cost and inconvenience to the patient; on the other hand, in resorbable sutures, resorption rate is unpredictable in the oral cavity, meaning they can either weaken or resorb too quickly or remain in the incision site for too long. 1 , 6 It also shows a ‘wicking’ phenomenon, which makes the suture a site for bacteria to retain and enter the tissue, giving place to secondary infection. In 1974, Postlethwaite discovered that silk has the maximum amount of inflammatory tissue response which may lead to many complications, such as stitch abscess, epithelial inclusion cysts, railroad track scar, fistulation, granuloma formation, wound dehiscence, foreign body reactions, tissue ischemia and tissue tearing. Needle prick injuries are a drawback too, due to the emergence of diseases like AIDS, hepatitis and several others, which carry high risk of transmission through it. 1 , 3 , 9 In order to overcome these obstacles, there is a need to find better alternatives to sutures. 3 , 4 , 6 , 9 , 10

New materials such as staples, tapes and tissue adhesives have been suggested as substitutes for sutures. In the 20th century, tissue adhesives of fibrin, cyanoacrylates, bovine collagen and thrombin, polyethylene glycol polymer and glutaraldehyde were developed. 2 , 10

Plastic adhesives (cyanoacrylates) were discovered and synthetized by a German chemist in 1949, as an attempt to substitute and overcome sutures' disadvantages, and 10 years later, Coover et al. reported their use in surgical procedures, submitting the report to the FDA in 1964. 1 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 11 Since then, it has been an area of interest as alternative to, or replacement for, sutures in surgical wound closure. 1 , 6

The ideal tissue adhesive should demonstrate shelf stability, complete polymerization even in the presence of moisture (blood, saliva or water), adequate working time, spread to cover the optimum area, provide wettability, not produce excess heat during the process of polymerization, provide strong and flexible bond, be tissue compatible (non‐toxic), biodegradable, easily applicable and non‐carcinogenic. 3 Cyanoacrylates have been described to be a group of simple, inexpensive, practical and effective adhesives with a wide range of applications in surgery, being in use for about the last 50 years in medical and dental practice. This is because of their immediate haemostatic/embolic effect, long half‐life, rapid adherence to hard and soft tissues (moist environments), ease of application, which shortens operation time and not requiring to be removed during the postoperative follow‐up. In addition, they are biodegradable, biocompatible and have an anti‐microbial effect in the oral cavity because of its bacteriostatic nature. 1 , 4 , 6 , 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 The cyanoacrylate materials are characterized according to the length of the carbon chain conjugated to the cyanoacrylate component and have a chemical formula CH2 = C(CN)‐COOR, where R‐donates any alkyl group, ranging from methyl to decyl. Altering the type of alkyl chains with a longer molecular chain prolongs the heat generated during curing, reducing or virtually eliminating the heat produced that could damage the soft tissue and hamper its blood supply, thus reducing tissue toxicity. 1 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 Previously ethyl and methyl cyanoacrylate were used for wound closure; however, they were discarded given their potential toxicities. 4 , 12 In 1964, the Tennessee Eastman Lab developed longer molecular chains and newer generation of cyanoacrylates that includes n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, octyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate and isoamyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, 1 , 4 , 11 which adhesive action produces an exothermic polymerization catalysed by the presence of small quantities of a weak base such as the water in saliva, blood or air. 1 , 6 , 8 , 11 , 15

The anionic polymerization is thought to provide the bonding action, as the polar CN and ester groups of the glue interact with amino and carboxyl groups of protein molecules of tissues freed of moisture and produce secondary intermolecular forces, such as hydrogen bonding, aided by mechanical interlocking of irregular and porous surfaces, resulting in high adhesive strength, higher tensile strength compared with suture, which keeps the wound edges in contact, allowing for healing by primary intention. Polymerization occurs within seconds (4 s in the spray form and 10–15 s in droplet form). 1 , 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 15 The adhesiveness is maximized by spreading the free‐flowing liquid in a very thin film, optimally less than one millimetre thick. 1 These materials are not absorbable and are sloughed from the surface of the skin and mucosa 7 to 10 days after adhesive application and are approved for external application only, not being used as internal tissue adhesives because of reactions, toxicity and carcinogenicity. 6 , 8 , 11 , 15

Recent studies have focused on non‐toxic higher homologues, such as the butyl form of cyanoacrylates, as it fulfils most of the properties required for wound healing. N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate is obtainable in sealed sterile containers, which can be stored in a refrigerator. It is available as ‘Histoacryl blue’, ‘Tissueacryl’ and ‘Enbucrilate’ and has been widely used as a tissue adhesive, due to its advantages like achieving immediate haemostasis (thrombogenic property), easiness of application, bacteriostatic properties and faster bonding and curing capacity to hard and soft tissues, compared to those of octyl cyanoacrylate and iso amyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate. 1 , 3 , 4 , 12 , 14 Because butyl cyanoacrylate is broken down slowly, it is not advisable to place a continuous layer of it between two healing surfaces; instead, it should be held in place and the adhesive should be placed on the top of the approximated wound. 1 Swabs, gloves and instruments should be kept clear of the adhesive, or they stick to the tissue. The material can then be removed from instruments with acetone. 14 The use of cyanoacrylates in the medical field has been done successfully in the maxillofacial area, wound closure, skin graft, face lifts, blepharoplasty, brow lifts and cosmetic surgeries; treatment of extraction sockets, fixation of mandibular fractures, healing of intraoral wounds, fixation of free gingival grafts (FGG) and healing of periodontal flaps were also found successful with the application of this cyanoacrylate. 1 , 3 , 15 On the contrary, several side effects were reported, such as irreversible retinal damage; therefore, patients should wear eye protection during the procedure. Eliminated products occur in urine, faeces and expired air, process that starts several minutes after gluing. The products of cyacryn degradation accumulate partially in different organs for a period up to 10 months. Maximum accumulation of the products of biodegradation occurs in the pituitary, brain, thyroid gland and liver. 1 , 14

Another sutureless technique that has received special attention for mimicking the natural fibrin mesh is Fibrin Fibronectin Sealing System (FFSS). It has been in use since the early 1900s, because of its effectiveness in mechanical and biological closure of intraoral wounds, as the synthetic fibrin material creates a fibrin clot. It is a combination of fibrinogen and thrombin, in which the thrombin acts as an enzyme and converts the fibrinogen to fibrin, which can act as a tissue adhesive. In addition to having an adhesive property, it also possesses an anti‐enzymatic effect, which promotes fibroblast aggregation, their growth and adhesion. It functions as an haemostatic agent (first reported use by Bergel in 1909), tissue adhesive and anastomotic agent (nerves and skin grafting) and is also able to reduce interventional time, less postoperative pain and, consequently, a significant increase in patient's comfort. 2 , 7 , 14 Fibrin sealants have diverse clinical applications. Mention of fibrin sealants in the oral and maxillofacial literature is limited, with only a few reports of its application as an ‘adjunct’ in vestibuloplasty, aesthetic facial surgery, head and neck reconstruction and periodontal procedures. The role of fibrin sealants in routine dentoalveolar and intraoral surgical procedures needs to be explored and assessed, for better clinical application, as they may also be a valuable tool for patients with special indications, such as for haemophiliacs and patients on oral anticoagulants such as warfarin, whom have a greater degree of haemorrhage and tighter control is required. 2 , 14

For this reason, an attentive systematic review of the literature was performed with the aim of gathering the differences of using surgical adhesives in oral surgery when compared to the conventional method of using sutures as a wound closure technique.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Methodology of review

The ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA)’ was applied for this study. 16

2.2. Formulation of research question and keywords selection

The approach used to formulate the research question, keyword selection and to answer the research question was PICO [Patient population (P), Intervention (I), Comparison (C), Outcomes (O)], since the use of PICO framework may lead to higher precision and relevancy of search results. 17

PICO criteria for the research question were: ‘What are the clinical differences (O) of using tissue adhesives (I) in patients who underwent oral surgical incisions (P) in comparison with conventional sutures used as an intraoral wound closure material (C)?’ Having in account this research question, the following keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used for the search: ((((((fibrin) OR ((tissue) OR (mucosa))))) AND (glue)) OR (adhesive)) AND ((oral surgery) OR (dentistry)) AND (incisions) AND (wound closure). Clinical trials and randomized controlled trials were the types of study used as filters to find the articles used in this review.

2.3. Search strategy

The literature included in this review was found on PubMed/Medline, EBSCO and Cochrane Library. For this, the keywords and MeSH terms were searched individually and combined with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ to identify the needs for this review. No systematic review was found exactly on this question under the defined criteria, which provided further interest and vindication to perform this review. The attentive search for the selection of studies was carried out from 5 April to 8 July 2022.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

The selection criteria applied for this study comprised patient population, language, timeline, study characteristics, outcomes and exclusion criteria. For patient population, patients who underwent oral surgical incisions were included in this study. With regard to the type and language of the chosen articles, articles published worldwide written in English with full access were chosen for the references. Regarding timeline, there were no restrictions. Prospective, randomized controlled trials and case–control studies were preferred and filtered on the databases to select bibliography. With respect to the outcomes, included articles had to mention clinical advantages, demerits/limitations, such as price, clinical postoperative results, easiness of application, aesthetics and so forth. Adding to that, our exclusion criteria ranged from animal studies, books, case reports and case series, cross‐sectional studies, Cohort studies, commentaries and conference papers, grey literature, policy and guidelines, review articles to unpublished data. This information is available in table form on Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Selection criteria.

| Patient population | Patients who underwent oral surgical incisions. |

|---|---|

| Language | Articles published worldwide written in English with full access. |

| Timeline | No restrictions. |

| Study characteristics | Prospective, randomized controlled trials and case–control studies. |

| Outcomes | Articles where clinical advantages, demerits/limitations (price, clinical postoperative results, easiness of application, aesthetics, etc.) were reported. |

| Exclusion criteria | Animal studies, books, case reports and case series, cross‐sectional studies, cohort studies, commentaries and conference papers, grey literature, policy and guidelines, review articles and unpublished data. |

2.5. Study selection process

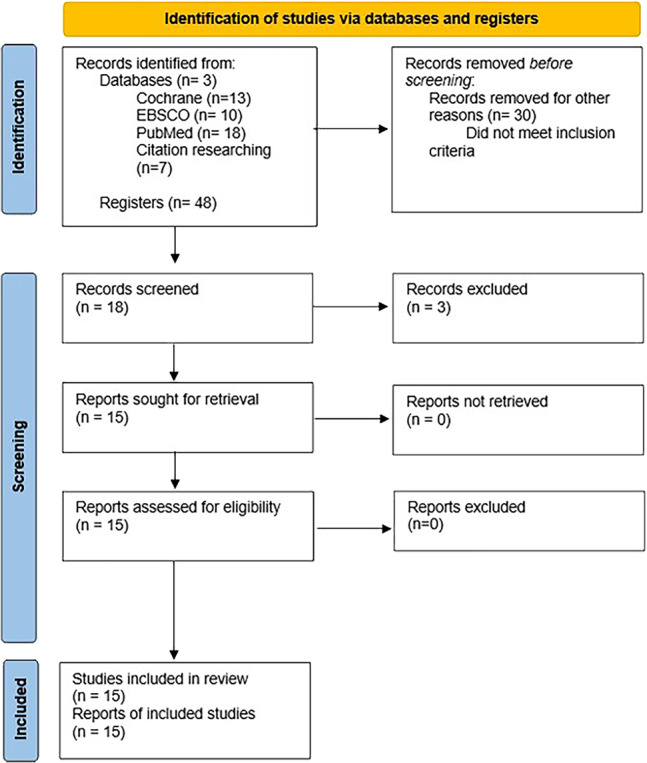

As a result of the systematic research with MeSH terms and citation researching, 48 articles were identified, 18 from PubMed/Medline, 13 from Cochrane Library, 10 from EBSCO and 7 from citation researching. Two reviewers independently matched studies to inclusion and exclusion criteria, and if there was any disagreement, a third reviewer aimed to mediate a consensus agreement. After preliminary screening of titles and abstracts was performed, 30 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria and three records were excluded for not being fully available. Out of these, 15 were assessed in English for full reading, meeting full settings agreement, and were selected for analysis and data extraction, according to the recommendations of the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA)’. A flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, which included searches of databases and registers only.

2.6. Quality assessment tool

The ‘Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Controlled Trials’ was used to assess the quality of the included studies. If all criteria were low for every domain, that meant that criteria were met, the study would be categorized as ‘good’. If one criterion was high risk for any domain, then the study was labelled as fair. If two or more criteria were high risk or unclear in more than two domains, then the study was labelled as poor. 18

2.7. Data analysis

Meta‐analyses were conducted using Review Manager version 5.4.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, United Kingdom, 2020). Dichotomous variables were analysed using a Mantel–Haenszel test with a random effects model, and the pooled effect was reported as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous data were analysed with an inverse‐variance method using a random effects model and expressed as mean differences (MDs) with corresponding 95% CIs. To calculate the MD, only studies reporting the mean and standard deviation (SD) were included in the meta‐analysis. Heterogeneity between studies was considered considerable when I 2 exceeded 75%. A p‐value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Studies were excluded from the meta‐analysis if there were zero events of the outcome measured in both arms of the study population.

3. RESULTS

After withholding articles following scanning of titles, abstracts and full texts, 15 studies were identified and included in the systematic review as: Study 1, Aljasser et al., 2021; Study 2, Ghoreishian et al., 2009; Study 3, Giray et al., 1997; Study 4, Gogulanathan et al., 2015; Study 5, Gümüş & Buduneli, 2014; Study 6, Joshi et al., 2011; Study 7, Kulkarni et al., 2007; Study 8, Oladega et al., 2019; Study 9, V Raj Kumar et al., 2010; Study 10, Setiya et al., 2015; Study 11, Suresh Kumar et al., 2013; Study 12, Suthar et al., 2020; Study 13, Vastani & Maria, 2013; Study 14, Pulikkotil & Nath, 2012 and Study 15, Stavropoulou et al., 2019. As mentioned before, these studies were categorized as randomized clinical trials and case–control studies.

The tables that summarize these studies including their characteristics regarding the name of the study, authors, year of publication, study design, aim, sample, materials, method, results and conclusions (viz‐a‐viz quality analysis) are listed down below in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the selected articles, regarding the name of the study, authors, year of publication, language, study design, aim, sample, materials and parameters assessed.

| No. | Study | Authors, year | Study design | Aim | Sample | Material | Assessed parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Comparison of polymeric cyanoacrylate adhesives with suturing in free gingival graft stability: A split‐mouth trial | Aljasser et al., 2021 14 | Case–control study | To compare the use of cyanoacrylate adhesives with the conventional suture technique in terms of stability and healing of FGG in the anterior and mandibular premolar regions. | 22 participants, ages ≥18 years old | Control group: sutures; Test group: butyl cyanoacrylate | KTW, GTT, FGG% shrinkage and pain using the VAS score. |

| 2. | Tissue adhesive and suturing for closure of the surgical wound after removal of impacted mandibular third molars: A comparative study | Ghoreishian, Gheisari and Fayazi, 2009 15 | Controlled clinical trial | To evaluate and compare the effectiveness of cyanoacrylate in the postoperative period of pain and haemorrhage with that of suture. | 16 patients (nine women and seven men; ages 18–24) with bone impaction and similar mandibular third molar inclination, on the right and left sides. | After bone removal and tooth resection, the right flap was closed with 3–0 silk sutures and the left flap with cyanoacrylate. | Postoperative period of pain and haemorrhage |

| 3. | Clinical and electron microscope comparison of silk sutures and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate in human mucosa | Giray et al., 1997 12 | Case–control study | Compare and evaluate the clinical and microscopic results of mucosal incisions closed with silk suture and with histoacryl blue (cyanoacrylate surgical glue) | 15 patients with primary diagnosis of apical granuloma | Silk suture thread and N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue | Pain, oedema, bleeding, epithelialization, necrosis and scar formation |

| 4. | Evaluation of fibrin sealant as a wound closure agent in mandibular third molar surgery—a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial | Gogulanathan et al., 2015 2 | Prospective randomized, controlled trial | Evaluate the effectiveness of fibrin sealants in achieving haemostasis and wound closure after mandibular third molar extraction compared with conventional suturing | 30 patients with bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars, without systemic diseases, with similar degrees of difficulty by Pell and Gregory classification and informed consent were recruited for the study | Fibrin sealants (test) and 3–0 black silk suture thread (control) | Time required to achieve wound closure and haemostasis; postoperative mouth opening, pain and oedema on postoperative days 1 and 7 |

| 5. | Graft stabilization with cyanoacrylate decreases shrinkage of free gingival grafts | Gümüş and Buduneli, 2014 13 | Randomized, controlled, blinded clinical trial | Comparatively evaluate three different stabilization methods with regards to the amount of shrinkage in free gingival graft | 45 patients divided into three groups (15 each, one male/14 females); 20–50 years old | Standardized 5–0 propylene sutures (conventional group); 7–0 propylene sutures and 2.5x magnification loupe (microsurgery group); butyl cyanoacrylate (PeriAcryl®, Glustitch, Delta, Canada) (cyanoacrylate group) | Pain in recipient and donor sites (visual analogue scale within the first postoperative week) |

| 6. | A comparative study: Efficacy of tissue glue and sutures after impacted mandibular third molar removal | Joshi et al., 2011 11 | Controlled clinical trial | To compare the effectiveness of amcrylate cyanoacrylate placement (versus conventional silk suture technique) for wound closure after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars and to assess the incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain. | 30 patients (19 women and 11 men; age range 20 to 32 years) with bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars—mesio‐angular or horizontal (Position B Class II, Pell & Gregory classification 1933, with difficulty index −5) | Conventional suture thread and cyanoacrylate glue | Incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain. |

| 7. | Healing of periodontal flaps when closed with silk sutures and N‐butyl cyanoacrylate: A clinical and histological study | Kulkarni, Dodwad and Chava, 2007 9 | Case–control study | Evaluate the healing of periodontal flaps using silk sutures and using N‐butyl cyanoacrylate | 24 patients aged 35–50 years with periodontal pockets of 6 millimetres or deep periodontal pockets, indicated for surgical procedures with periodontal flap | Black braided silk 3–0 and N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate | Epithelium and three areas with the most inflammatory cells to assess inflammatory cell count and vascularity/endothelial proliferation |

| 8. | Comparative evaluation of n‐ butyl cyanoacrylate and silk sutures in intraoral wound closure—A clinical study | Kumar and Rai, 2010 1 | Case–control study | To compare and contrast the effects on healing of intraoral wounds in cases of alveoloplasty when closure was carried out by n‐butyl cyanoacrylate and black braided silk suture through the assessment of amount of time taken to achieve wound closure, immediate and postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain and incidence of postoperative wound infection. | 20 patients requiring alveoloplasty either bilateral in the same arch or in the upper and lower arch. |

3–0 braided silk sutures‐Group I N‐Butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate bio adhesive (Histoacryl blue)‐Group II |

Amount of time taken to achieve wound closure, immediate and postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain and incidence of postoperative wound infection. |

| 9. | Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or silk suture for closure of surgical wound following removal of an impacted mandibular third molar: A randomized controlled study | Oladega, James and Adeyemo, 2019 6 | Randomized controlled trial | Compare the postoperative sequelae and wound healing between cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and silk suture. | 120 subjects (75 women and 45 men), over 18 years old (mean age 27.2 years), no known systemic disease, no allergies to drugs or anaesthetics, good oral hygiene, non‐smokers and with mesio‐angularly impacted third molars. | Cyanoacrylate surgical glue and silk suture thread. | Postoperative pain, oedema, trismus, bleeding, dehiscence and wound infection |

| 10. | Comparative evaluation of efficacy of tissue glue and sutures after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars—A prospective controlled clinical study | Setiya et al., 2015 8 | Clinical, prospective, controlled trial | To evaluate the efficacy, advantages and disadvantages of cyanoacrylate glue (Iso amyl 2‐cyanoacrylate) in sutureless surgical wound closure after surgical removal of impacted third molars. | 50 patients with impacted bilaterally symmetrical third molars; 20 males and 30 females; ages 18–35 | Silk suture and cyanoacrylate Glue (Iso amyl 2‐cyanoacrylate) | Postoperative pain severity, haemorrhage and swelling. |

| 11. | Fibrin sealant as an alternative for sutures in periodontal surgery | Shaju Jacob Pulikkotil and Sonia Nath, 2012 7 | Split‐mouth randomized controlled clinical trial | To compare wound healing of periodontal flap closure clinically, histologically and morphometrically, using fibrin sealant and sutures. | 10 patients, ages 18–60 years, at least four teeth of either quadrant in a single jaw with pockets of ≥6 millimetres. | Fibrin sealant (test sites, n = 10) and sutures (control sites, n = 10) | The number of fibroblasts, inflammatory cells and blood vessels in both test and control sites after 8 days of wound healing. Plus, wound healing at 7, 14 and 21 days. |

| 12. | A randomized clinical trial of cyanoacrylate tissue adhesives in donor site of connective tissue grafts | Stavropoulou et al., 2019 10 | Randomized Clinical Trial | To compare patient‐centred outcomes, early wound healing and postoperative complications at palatal donor area of subepithelial CTG between cyanoacrylates tissue adhesives and PTFE sutures. | 35 patients (10 males and 25 females; ages 23–81) who required harvesting of CTG were assigned to one of two groups (‘suture’ and ‘cyanoacrylate’). | Standardized continuous interlocking 6–0 PTFE sutures, for the ‘suture’ group and a high viscosity blend of n‐butyl and 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate, for the ‘cyanoacrylate’ group |

Primary outcomes: the discomfort (eating, speaking, amongst others) from the donor site during the first postoperative week (self‐reported on a VAS). Secondary outcomes: time required for suture placement or cyanoacrylate application, patient self‐reported pain on the first day, and the first week after surgery, the analgesic intake and the MEHI. |

| 13. | Comparison between silk sutures and cyanoacrylate adhesive in human mucosa—A clinical and histological study | Suresh Kumar et al., 2013 3 | Case–control study | To compare the effectiveness of black silk sutures with cyanoacrylate surgical glues in closing surgical incisions. | 10 patients, between 15 and 30 years of age | 3–0 black silk suture thread and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue |

Clinical observations: epithelialization, inflammation, scar formation. Histological observations: inflammatory infiltrate and scar formation. |

| 14. | Comparing intraoral wound healing after alveoloplasty using silk sutures and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate | Suthar et al., 2020 4 | Prospective randomized, controlled trial, in vivo | To evaluate and compare the healing of an intraoral wound, using 3–0 silk suture and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, after alveoloplasty. | 20 patients (four women and 16 men; ages 45–78) indicated for bilateral (upper and lower) alveoloplasty, with no pre‐existing pathological condition or systemic disease. | 3–0 silk suture thread, braided and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue | Time to surgical wound synthesis, incidence of immediate and postoperative haemostasis, the timing of recurrence to SOS medication, the side on which pain appears first, and the side on which wound healing begins earliest |

| 15. | Healing of intraoral wounds closed using silk sutures and isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate glue: A comparative clinical and histologic study | Vastani and Maria, 2013 5 | Randomized prospective trial | Compare the clinical and histologic healing of intraoral wounds closed using 3–0 silk suture versus isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate glue | 30 patients (21 men and nine women), 40‐70 years old | 3–0 silk suture on side one and isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate on side two |

Clinical observations: incidence of tenderness and erythema Histological observations: inflammatory cell infiltration, vascularity and fibroblastic activity |

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

All studies compared different types of wound closure materials. Study 1 compared the use of cyanoacrylate adhesives with the conventional suture technique, assessing stability and healing of gain the anterior and mandibular premolar regions; Study 2 compared the effectiveness of cyanoacrylate in the postoperative period of pain and haemorrhage versus suture; Study 3 compared clinical and microscopic results of mucosal incisions closed with silk suture and with cyanoacrylate surgical glue (Histoacryl Blue); Study 4 compared the effectiveness of fibrin sealants in achieving haemostasis and wound closure after mandibular third molar extraction versus conventional suturing; Study 5 compared three different stabilization methods with regard to the amount of shrinkage in free gingival graft, using 5–0 propylene sutures, 7–0 propylene sutures and butyl cyanoacrylate; Study 6 compared the effectiveness of Amcrylate cyanoacrylate placement versus conventional silk suture technique, for wound closure after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars and assessed the incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain; Study 7 compared the healing of periodontal flaps using silk sutures and using N‐butyl cyanoacrylate; Study 8 compared the postoperative sequelae and wound healing between cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and silk suture after the removal of impacted mandibular third molars; Study 9 compared the effects on healing of intraoral wounds in cases of alveoloplasty when closure was carried out by n‐butyl cyanoacrylate and black braided silk suture, assessing amount of time taken to achieve wound closure, immediate and postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain and incidence of postoperative wound infection; Study 10 compared the effectiveness of black silk sutures with cyanoacrylate surgical glues in closing surgical incisions; Study 11 compared the efficacy, advantages and disadvantages of cyanoacrylate glue (Iso amyl 2‐cyanoacrylate) in sutureless surgical wound closure after surgical removal of impacted third molars; Study 12 compared the healing of an intraoral wound, using 3–0 silk suture and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, after alveoloplasty; Study 13 compared the clinical and histologic healing of intraoral wounds closed using 3–0 silk suture versus isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate glue; Study 14 compared wound healing of periodontal flap closure clinically, histologically and morphometrically, using fibrin sealant and sutures; Study 15 compared patient‐centred outcomes, early wound healing and postoperative complications at palatal donor area of subepithelial connective tissue grafts between cyanoacrylates tissue adhesives and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sutures.

Each study assessed a diversity of parameters to compare the effectiveness of the experimental materials. In Study 1, keratinized tissue width (KTW) gingival tissue thickness (GTT), FGG% shrinkage and pain (using the VAS score) were evaluated; in Study 2, postoperative period of pain and haemorrhage were evaluated; in Study 3, pain, oedema, bleeding, epithelialization, necrosis and scar formation were evaluated; in Study 4, time required to achieve wound closure and haemostasis; postoperative mouth opening, pain and oedema on postoperative days 1 and 7 were evaluated; in Study 5, pain in recipient and donor sites, using the visual analogue scale (VAS) within the first postoperative week, were evaluated; in Study 6, incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain was evaluated; in Study 7, epithelium and three areas with the most inflammatory cells were observed to assess inflammatory cell count and vascularity/endothelial proliferation; in Study 8, postoperative pain, oedema, trismus, bleeding, dehiscence and wound infection were evaluated; in Study 9, the amount of time taken to achieve wound closure, immediate and postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain and incidence of postoperative wound infection was evaluated; in Study 10, postoperative pain severity, haemorrhage and swelling were evaluated; in Study 11, clinical observations, such as epithelialization, inflammation, scar formation and histological observations, as inflammatory infiltrate and scar formation were assessed; in Study 12, time to surgical wound synthesis, incidence of immediate and postoperative haemostasis, the timing of recurrence to SOS medication, the side on which pain appears first and the side on which wound healing begins earliest were evaluated; in Study 13, clinical observations, as the incidence of tenderness and erythema and histological observations, as inflammatory cell infiltration, vascularity and fibroblastic activity, were assessed; in Study 14, the number of fibroblasts, inflammatory cells and blood vessels on the 8 days of wound healing, plus, wound healing at seven, 14 and 21 days; in Study 15, primary outcomes, such as the discomfort (eating, speaking, etc.) from the donor site during the first postoperative week (self‐reported on a VAS) and secondary outcomes like time required for suture placement or cyanoacrylate application, patient self‐reported pain on the first day, and the first week after surgery, the analgesic intake and the Modified Early‐wound Healing Index (MEHI) were evaluated (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the selected articles, regarding method, results and conclusion.

| No. | Study | Authors, year | Method | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Comparison of polymeric cyanoacrylate adhesives with suturing in free gingival graft stability: A split‐mouth trial | Aljasser et al., 2021 14 |

Split‐mouth study. Each side (second premolar to central incisor) was randomized to determine control (suture) and test (butyl cyanoacrylate) groups. Complete clinical parameters were used to assess periodontal health. |

No significant differences were observed in mean KTW values or FGG% contraction at six time points (p < 0.05), while highly significant differences were observed in mean GTT values at six time points (F = 3 0.32; p = 0.008). | The use of CAA in FGG stability and healing is comparable to conventional suturing for soft tissue grafts in terms of successful results and present cost‐effectiveness, lower time consumption, postoperative pain and stability, and comparable graft dimensions. |

| 2. | Tissue adhesive and suturing for closure of the surgical wound after removal of impacted mandibular third molars: A comparative study |

Ghoreishian, Gheisari and Fayazi, 2009 15 |

Third molar surgery was performed in two phases, 4 weeks apart, under local anaesthesia. The severity of pain and bleeding on postoperative days was assessed using a VAS. |

Data analysis showed that postoperative bleeding with cyanoacrylate method was less significant than with suture on the first and second days after surgery (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in pain severity between the two methods (p > 0.05). | The efficacies of cyanoacrylate and suture in wound closure were similar in pain severity, but the use of cyanoacrylate resulted in better haemostasis. |

| 3. | Clinical and electron microscope comparison of silk sutures and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate in human mucosa | Giray et al., 1997 12 |

Root recessions were made on the upper incisor teeth, using silk suture and cyanoacrylate glue on both sides of the frenum, as synthesis materials. The healing evolution was observed on the first, second, third, seventh, 14th and 21st days, and the suture was removed after 7 days. Punch biopsies were obtained from both sides. |

Clinical observations show: higher epithelialization on the n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate side, at day 3 and 7; more marked scar formation and more local inflammation on the suture side, on day 21. Electron microscopic observation of the punch biopsies showed normal ultrastructural morphology on both sides. |

Histocryl is a non‐cytotoxic surgical adhesive and can be used as an alternative to oral sutures, presenting numerous advantages. |

| 4. | Evaluation of fibrin sealant as a wound closure agent in mandibular third molar surgery—a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial | Gogulanathan et al., 2015 2 | Wound closure was performed after extraction with fibrin sealant on the study side and suture on the control side (each patient is their own control). Time gap between surgery on each side was 3 weeks to avoid overlap of postoperative symptoms. | The study group demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the duration to achieve haemostasis (1.2 vs. 251.9 s; p < 0.001) and wound closure (152.8 vs. 328.8 s; p < 0.001) compared with the control group. The study group also had significantly reduced pain scores (2.0 vs. 3.5; p < 0.001) and increased mouth opening after surgery (p < 0.001). No adverse effects of fibrin sealant were observed. | Fibrin sealant is a superior intraoral closure and haemostatic agent and a worthy alternative to suturing. |

| 5. | Graft stabilization with cyanoacrylate decreases shrinkage of free gingival grafts | Gümüş and Buduneli, 2014 13 |

Patients were split in three study groups, according to how stabilization was achieved with conventional technique, cyanoacrylate or microsurgery. A specific software on standard photographs was used to calculate keratinized tissue width, graft area, gingival recession at baseline, 1‐, 3‐, 6‐month follow‐ups. Duration of surgery was also recorded. |

The cyanoacrylate group showed significantly less graft shrinkage, pain in the recipient site and less duration of surgery. Change in keratinized tissue width was similar in the study groups at all times. |

Cyanoacrylate may be considered as an alternative for stabilization of free gingival grafts |

| 6. | A comparative study: Efficacy of tissue glue and sutures after impacted mandibular third molar removal | Joshi et al., 2011 11 | After extraction, closure was performed with conventional sutures on one side and with cyanoacrylate on the other side. | Data analysis showed that postoperative haemorrhage with the cyanoacrylate method was less significant than with suture on the first and second days after surgery. There was no significant difference in pain severity between the two methods. | This study suggested that the effectiveness of both cyanoacrylate and suturing in wound closure were similar in pain severity, but the use of cyanoacrylate showed better haemostasis. |

| 7. | Healing of periodontal flaps when closed with silk sutures and N‐butyl cyanoacrylate: A clinical and histological study | Kulkarni, Dodwad and Chava, 2007 9 |

The patients were divided into three groups of eight patients: Group A—day seven group; Group B—day 21 group and Group C—day 6 group. The selection of the suture and cyanoacrylate site was done randomly: simple interdental knot with suture in one half of the surgical area and in the other half with N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, placed drop by drop on the flap margins, which were kept in place until a thin film of cyanoacrylate was formed. Evaluation of all patients after 7 days and removal of sutures and any cyanoacrylate present. Gingival punch biopsies were taken in group B at day 21 and C at day 6. |

Compared to suture thread, cyanoacrylate glue shows less inflammation during the first week. Over a period of 21 days to 6 weeks, both surgical glue and suture show similar healing patterns. |

Cyanoacrylate promotes and assists the initial healing phase. |

| 8. | Comparative evaluation of n‐butyl cyanoacrylate and silk sutures in intraoral wound closure—A clinical study | Kumar and Rai, 2010 1 | Surgical sites were divided into two groups, in the same patient, according to materials used: Group I wounds closed with sutures and Group II wound closure using N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate bio adhesive. |

The length of incision was shorter in Group I but the time taken for closure was more compared with Histoacryl. Group I: during the immediate postoperative period, 10 patients had mild ooze after suturing; pain on third and seventh postoperative days (19 patients); wound dehiscence (two patients) Group II: Immediate haemostasis; mild pain on third day (two patients) and the other 18 patients were asymptomatic; no wound dehiscence was observed. |

Although N‐butyl‐2‐ cyanoacrylate has a higher cost, it can effectively be used for intraoral wound closure: the procedure is relatively painless and quick, the material causes less tissue reaction and it achieves immediate homeostasis it is bacteriostatic (protection from wound infection). |

| 9. | Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or silk suture for closure of surgical wound following removal of an impacted mandibular third molar: A randomized controlled study | Oladega, James and Adeyemo, 2019 6 |

The sample was divided into two groups of 60 participants: control group (silk suture thread) and study group (cyanoacrylate surgical glue). Follow‐up: 7 weeks |

There was no significant difference in the parameters evaluated, with the exception of postoperative bleeding, in which the control group had a statistically significant difference greater than the study group. | Cyanoacrylate surgical glue compares favourably with silk suture as wound synthesis materials and appears to have beneficial haemostatic effects on postsurgical bleeding. |

| 10. | Comparative evaluation of efficacy of tissue glue and sutures after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars—A prospective controlled clinical study | Setiya et al., 2015 8 | The sample was divided into two groups: Control group (surgical wound closure with conventional suture); Study group (surgical wound closure with cyanoacrylate glue). | Postoperative pain severity with cyanoacrylate glue was less significant than with suturing on the first, second and seventh day after surgery, while postoperative haemorrhage and swelling with cyanoacrylate glue were less significant than with cyanoacrylate glue. | Both cyanoacrylate glue and conventional suture are shown to be effective in healing the surgical wound; however, cyanoacrylate glue has better haemostasis, less pain and oedema and is a quick procedure. |

| 11. | Fibrin sealant as an alternative for sutures in periodontal surgery | Shaju Jacob Pulikkotil and Sonia Nath, 2012 7 | After the participants had periodontal surgery, fibrin sealant was applied for flap closure in the test sites and sutures on the control site. Clinical observation of wound healing was made at seven, 14 and 21 days, and biopsy was taken on the 8 days. | On day 7, healing was better in fibrin sealant site. Histologically mature epithelium and connective tissue formation was seen in fibrin sealant site with increased density of fibroblasts (F = 70.45 ± 7.22; S = 42.95 ± 4.34, p < 0.001) and mature collagen fibres. The suture site had a greater number of inflammatory cells (S = 32.58 ± 4.29; F = 20.91 ± 4.46, p < 0.001) and a greater number of blood vessels (S = 11.89 ± 3.64; F = 5.74 ± 2.41, p = 0.005). | Fibrin sealant can be a better alternative to sutures for periodontal flap surgery. |

| 12. | A randomized clinical trial of cyanoacrylate tissue adhesives in donor site of connective tissue grafts | Stavropoulou et al., 2019 10 | After the graft was harvested from the patients, they were randomly assigned to one of two groups (‘suture’ group and ‘cyanoacrylate’ group), in which the periodontal flaps were closed with the materials mentioned. | The median value of discomfort was 1.49 in the ‘suture’ group and 1.86 in the ‘cyanoacrylate’ (p = 0.56). The mean time required for suture placement was 7.31 minutes and for cyanoacrylate application 2.16 minutes (p < 0.0001). No statistically significant differences were found between the two methods in reported pain level, analgesic intake and MEHI | Cyanoacrylate acts similarly to sutures and can be used for wound closure of the donor site of CTG. The application was about 5 minutes faster than conventional suture placement, reducing the total time of the surgical procedure. |

| 13. | Comparison between silk sutures and cyanoacrylate adhesive in human mucosa—A clinical and histological study | Suresh Kumar et al., 2013 3 |

The sample underwent bilateral apicectomy, the surgical incision being closed with 3–0 black silk suture on one side of the frenum and with n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue on the other side. A clinical evaluation was performed on the first, second, third and seventh days after surgery. On the seventh day, the sutures were removed and small punch biopsies were performed at both sites for histopathological analysis under an electron microscope. |

Clinical observations showed that on the third‐ and seventh‐day epithelialization was better on the side treated with n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, and that on the sutured side, there was significant inflammation and scar formation. Histological observations showed that the sutured tissues had a dense inflammatory infiltrate and scar formation along the edges of the incision and that the sites where cyanoacrylate glue was applied had less inflammatory infiltrate and a uniform distribution of neutrophils, lymphocytes, histocytes and eosinophils. |

Compared with suture, cyanoacrylate glue has less postoperative inflammation and good healing, clinically and histologically. |

| 14. | Comparing intraoral wound healing after alveoloplasty using silk sutures and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate | Suthar et al., 2020 4 |

The sample underwent the surgical procedure of alveoloplasty, and the wound was closed with suture thread on one side and cyanoacrylate glue on the other (chosen by the ‘coin toss’ method): Group one: wounds closed with 3–0 braided silk suture thread; Group two: wounds closed with n‐buty‐2‐cyanoacrylate (Endocryl). |

Compared with 3–0 silk suture thread, cyanoacrylate surgical glue has superior haemostatic properties, less surgical intervention time, less postoperative pain and better healing. | The results obtained show that cyanoacrylate surgical glue is a suitable and superior alternative to conventional sutures (3–0 silk suture thread) for surgical wound synthesis after alveoloplasty. |

| 15. | Healing of intraoral wounds closed using silk sutures and isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate glue: A comparative clinical and histologic study | Vastani and Maria, 2013 5 |

Alveoloplasty was performed in the mandibular anterior region of edentulous arches. The surgical sites were evaluated on the first, seventh, 14th and 21st postoperative days for tenderness and erythema. Incisional biopsies were performed on both sutured and glued sides: in group A (15 cases) on the seventh postoperative day and in group B (15 cases) on the 14th postoperative day. Microscopic examination was made. |

The incidence of tenderness and erythema was increased on the sutured side on the first, seventh and 14th postoperative days but was similar to that on the glued side on the 21st postoperative day. In the patients biopsied on the seventh postoperative day, values of inflammatory cell infiltration and vascularity were higher on the sutured side, whereas in patients biopsied on the 14th postoperative day, only vascularity was higher on the sutured side. |

Isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate may aid initial healing, besides being safe, rapid, painless and easy to use for the closure of uninfected intraoral incisions after bringing the edges together and creating a saliva‐free field. |

These studies compared the outcomes of using surgical adhesives with the conventional method of using sutures as a wound closure technique. These parameters assessed are shown in Figure 2 with the respective percentage of their mentioning in the evaluated articles.

FIGURE 2.

Parameters assessed.

The age range of the participants in the fifteen included studies was 18 and above. Both genders were included. All studies included in this current review were published between 1997 and 2021.

3.2. Quality assessment of the included studies

The RoB version 2.0 was used to evaluate risk of bias under five domains as well as an overall evaluation of each trial as low or high risk of bias. 19 , 20

In Study 1, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given clearly, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study and age of participants are given. In the control group, sutures were used to stabilize the FGG, while in the test group, it was stabilized with butyl cyanoacrylate. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. KTW, GTT, FGG% shrinkage and pain using the VAS score were assessed as possible postoperative complications, in different time points (baseline, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 days). All parameters were assessed using objective clinical protocols, being the VAS score the most subjective one, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. On that account, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 2, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation were not available, which gives some concerns on allocation and concealment bias. Sample size of study, diagnosis, age and gender of participants are given. After bone removal and tooth resection, the right flap was closed with 3–0 silk sutures and the left flap with cyanoacrylate. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as postoperative period of pain and haemorrhage. Parameters were assessed the subjective VAS score by the patient, being analysed in a computer software for data analyses afterwards, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. As a consequence, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 3, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given, which makes this study questionable from allocation and concealment bias. Sample size of study and diagnosis are given. Root recessions were made on the upper incisor teeth, using silk suture and cyanoacrylate glue on both sides of the frenum, as synthesis materials. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as pain, oedema, bleeding, epithelialization, necrosis and scar formation assessed on the first, second, third, seventh, 14th and 21st days. All parameters were assessed by clinical observation and small punch biopsies for electron microscopic observation, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. In this way, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 4, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given clearly, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study, inclusion and exclusion criteria are given. The use of fibrin sealants and 3–0 black silk suture thread were used. Blindness of study is also mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as time required to achieve wound closure and haemostasis; postoperative mouth opening, pain and oedema on postoperative days 1 and 7. All parameters were assessed with clinical visits to check for pain on day 1 postoperative and for maximum interincisal opening and swelling on days 1 and 7 postoperative; a numerical pain rating scale was used to assess pain; facial swelling was measured in millimetres and recorded, using fixed references; a baseline measurement was made just before surgery and similar measurements were done on days 1 and 7 post‐surgery; the degree of swelling was calculated as the difference between the averages of the preoperative and postoperative values. This makes it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For this matter, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 5, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given clearly, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age and gender of participants are given. Standardized 5–0 propylene sutures (conventional group); 7–0 propylene sutures and 2.5x magnification loupe (microsurgery group); butyl cyanoacrylate (cyanoacrylate group) were used. Blindness of study is mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such probing depth, plaque index and clinical attachment level (at six sites; mesio‐buccal, mid‐buccal, disto‐buccal, mesio‐lingual, mid‐lingual and disto‐lingual locations), and papilla bleeding index was recorded on each tooth present except third molars at baseline, 1‐, 3‐ and 6‐month follow‐ups. All parameters were assessed using clinical photographs, statistical analysis, 1‐, 3‐ and 6‐month follow‐ups, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. On that account, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 6, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age, gender and diagnosis of participants are given. Conventional suture thread and cyanoacrylate glue are used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain in a 1‐month follow‐up. Parameters were assessed using the VAS score by the patient and posteriorly analysed statistically, which gives some concerns for the risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is some concerns. As a consequence, overall risk of biasness of study shows some concerns.

In Study 7, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age and diagnosis of participants are given. Black braided silk 3–0 and N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate are used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as epithelium and three areas with the most inflammatory cells to assess inflammatory cell count and vascularity/endothelial proliferation in a follow‐up of 7 days (group A), 21 days (group B) and 6 days (group C). Parameters were assessed the Turesky‐Gilmore‐Glickman modification of the Quigley‐Hein plaque index, and the Löe and Silness gingival index were used to record the respective data and the biopsy specimens were first observed under the microscope at 10x magnification for assessment of the epithelium, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For that, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 8, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given clearly, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age, gender and diagnosis of participants are given. Cyanoacrylate surgical glue and silk suture thread were used. Blindness of study is mentioned. Patient/carer was not aware in regards to the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were aware of it, only after surgery. Thus, the risk of bias due to deviation from intended intervention is low. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as postoperative pain, oedema, trismus, bleeding, dehiscence and wound infection for a 7‐week follow‐up. Data were analysed using the SPSS for Windows (version 16.0, Chicago, IL, USA). The student t‐test was used in analysis of measures of pain, interincisal mouth opening and facial swelling between the two groups; the proportion of those with wound healing complications in the two groups was compared using Chi‐square; cross‐tabulation test was used in the analysis of postoperative bleeding between the two groups and the critical level of significance was set at p < 0.05, which makes it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. Correspondingly, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 9, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study and diagnosis of participants are given. 3–0 braided silk sutures and N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate bio adhesive (Histoacryl Blue) were used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were (probably) aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as the amount of time taken to achieve wound closure, immediate and postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain and incidence of postoperative wound infection on the third, seventh, 14th and 21st postoperative days. Parameters were assessed by clinical observation and patient report of symptoms, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For this matter, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 10, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age, gender and diagnosis of participants are given. Silk suture and cyanoacrylate glue (Iso amyl 2‐cyanoacrylate) were used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as postoperative pain severity, haemorrhage and swelling for a 7‐week follow‐up. Parameters were assessed using VAS scales for bleeding and pain and clinical observation, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For that reason, overall risk of biasness of study shows some concerns.

In Study 11, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study and age of participants are given. 3–0 black silk suture thread and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue were used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as clinical observations (epithelialization, inflammation and scar formation) and histological observations (inflammatory infiltrate and scar formation) for a 7‐day follow‐up. Parameters were assessed by clinical and histological observation, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. As a result, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 12, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age, gender and diagnosis of participants are given. 3–0 silk suture thread, braided and n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate surgical glue were used. Blindness of study is not mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as time to surgical wound synthesis, incidence of immediate and postoperative haemostasis, the timing of recurrence to SOS medication, the side on which pain appears first and the side on which wound healing begins earliest. All parameters were assessed by clinical observation and the data were analyses using the IBM SPSS Statistics (ver. 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), with a P‐value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For that reason, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 13, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are not given clearly, which makes this study questionable from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age and gender of participants are given. 3–0 silk suture and isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate were used. Blindness of study is mentioned for the assessment observers. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as clinical observations (incidence of tenderness and erythema) and histological observations (inflammatory cell infiltration, vascularity and fibroblastic activity) for a 7‐day follow‐up. Parameters were assessed by clinical and histopathological observation, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. As a consequence, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 14, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age and diagnosis of participants are given. Fibrin sealant and sutures were used. Blindness of study is mentioned to choose the intervention's site. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as the number of fibroblasts, inflammatory cells and blood vessels in both test and control sites after 8 days of wound healing and assessment of wound healing at seven, 14 and 21 days. All parameters were assessed by clinical and histological assessment, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. Thus, overall risk of biasness of study is low.

In Study 15, details regarding randomization of allocation and concealment of allocation are given clearly, which makes this study free from allocation bias. Sample size of study, age and gender of participants are given. Standardized continuous interlocking 6–0 PTFE sutures and a high viscosity blend of n‐butyl and 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate were used. Blindness of study is mentioned. No information was given on patient/carer awareness regarding the type of intervention being sued while practitioners were probably aware of it. This shows some concerns on biasness due to deviation from intended intervention. Outcomes of all the randomized participants were given, and bias from missing outcomes data was low. For the assessment of possible postoperative complications, there was a list of parameters, such as primary outcomes (the discomfort from the donor site during the first postoperative week—self‐reported on a VAS) and secondary outcomes (time required for suture placement or cyanoacrylate application, patient self‐reported pain on the first day and the first week after surgery, the analgesic intake and the Modified Early‐wound Healing Index). All parameters were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank, Fisher exact test and Program R version 3.5.1, which make it a low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes. The risk of bias in the selection of the reported results is low. For that reason, overall risk of biasness of study is considered low.

Overall, in this review, it was found that thirteen studies had low risk of bias and two showed some concerns, which arose mainly from randomization process, deviations from intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome. On Figure 3 of the appendix, a traffic light graph illustrates the risk assessment for the selected studies.

FIGURE 3.

Risk assessment of included trials (n = 15).

3.3. Data analysis

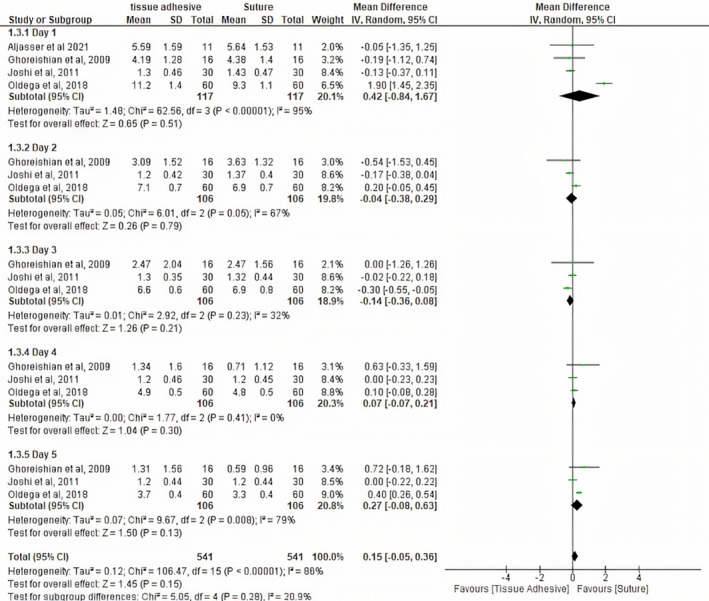

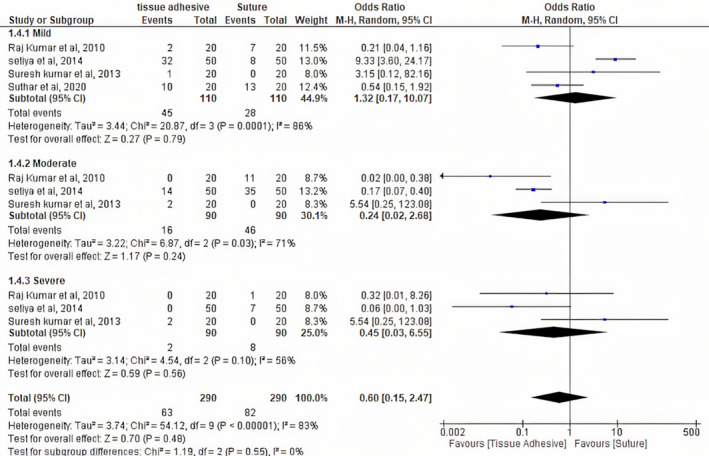

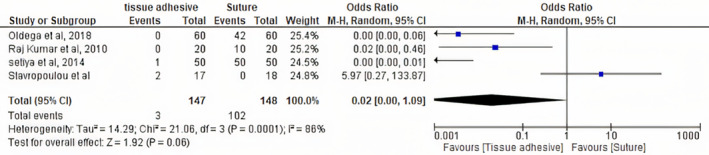

A random effect meta‐analysis was performed to determine the effectiveness of tissue adhesives versus sutures in terms of postoperative pain index and incidence of postoperative pain. The mean difference of 95 percent confidence interval was calculated for continuous variables, and the odd ratio (OR) was calculated for dichotomous variables such as the incidence of postoperative pain. A total of four studies of tissue adhesives and sutures were added to the postoperative pain index outcome. No statistically significant difference was found in the mean of both groups with a mean difference of 0.15, [95% CI −0.05, 0.36], p = 0.15 and I 2 of 86% as shown in Figure 4. Similarly for pain incidence on day 2, no statistically significant difference was found with an OR of 0.60, [95% CI 0.15, 2.47] p = 0.48 and I 2 of 83% as shown in Figure 5. Giray et al. (1997) measured postoperative pain qualitatively few patients in the suture group, and minimal patients in the tissue adhesive group had pain on day 2.

FIGURE 4.

Pain index (VAS score).

FIGURE 5.

Pain events.

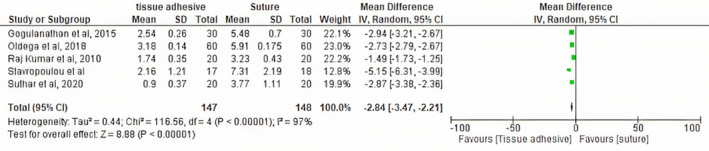

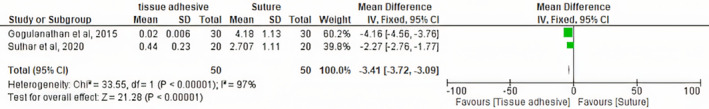

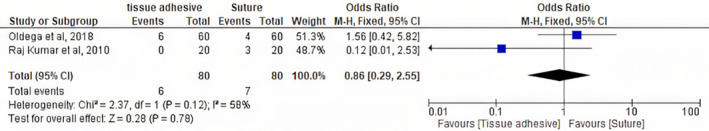

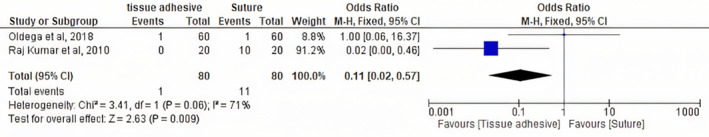

Tissue adhesives have less average time for closure of wound as compared to the suture group with a mean difference of −2.84 [95% CI −3.47, −2.21] p < 0.001 and I 2 of 97% as shown in Figure 6. Regarding postoperative bleeding or haemorrhage incidence, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups with an OR of 0.02 [95% CI −0.01, 1.09], p = 0.06 and I 2 of 86% as shown in Figure 7. Tissue adhesive was associated with less time to achieve homeostasis as compared to sutures with a mean difference of 3.41 [95% CI −3.72, −3.09], p < 0.001 and I 2 of 97% as shown in Figure 8. Raj Kumar et al. (2010) reported that immediate haemostasis was observed after the application of histoacryl during the incision wound closure. Two studies by Oldega et al. (2019) and Raj Kumar et al. (2010) reported wound dehiscence and infection as the results are shown in Figures 9 and 10, respectively. Kulkarni et al. (2007) revealed that plaque index scores of the suture and the cyanoacrylate sites in the 7th‐day group were significantly different (p < 0.01). It also showed that chronic inflammatory cells were present in all specimens. No histiocytes, foreign body giant cells or phagocytes were detected. The chronic inflammatory cells were present on all three observation days in both sites. A statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between the suture and cyanoacrylate sites was detected only in the 7th‐day group. Pulikkotil & Nath (2012) showed that the mean number of fibroblasts was higher in tissue adhesives (70.45 ± 7.22) than in the sutures (42.95 ± 4.344), and it was statistically significant (p = 0.000). The number of blood vessels and inflammatory cells was more in the suture site (11.89 ± 3.64; 32.58 ± 4.29) than in tissue the adhesive site (5.74 ± 2.41; 20.91 ± 4.46), and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.005).

FIGURE 6.

Average time for closure.

FIGURE 7.

Postoperative bleeding.

FIGURE 8.

Time to homeostasis.

FIGURE 9.

Wound dehiscence.

FIGURE 10.

Postoperative infection.

4. DISCUSSION

Sutures have prevailed the base for wound and bleeding management for centuries, yet show some obstacles, which motivated the need to find and develop alternatives and/or substitutes to overcome their disadvantages, such as surgical glues. 2 , 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 10

In total, the fifteen studies included in this systematic review compared the use of sutures (silk and PTFE) with several tissue adhesives, such as n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate, 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate, isoamyl 2‐cyanoacrylate and fibrin sealants, for closure of surgical incisions in 477 adult patients. All studies had as exclusion criteria ages 18 years old and above, being medically comprised. Both genders were integrated in all the articles. Method, results and conclusions of all studies are listed below in Table 2. For a better systematization of results, discussion will be presented in topics per theme assessed in the studies:

4.1. Periodontal application

A split‐mouth study conducted in 22 adult patients showed no significant differences in mean KTW values or FGG% contraction at the six time points assessed, while highly significant differences were observed in mean GTT values at those time frames. Hence, the use of cyanoacrylates adhesives may be a promising alternative to conventional and microsurgical techniques for stabilizing FGG in the oral cavity, due to its cost‐effectiveness, lower time consumption, postoperative pain and stability and comparable graft dimensions. 14

In 2014, Gümüş and Buduneli gathered that the cyanoacrylate group showed significantly less graft shrinkage, pain in the recipient site and less duration of surgery, while change in KTW was similar in the study groups at all times. So, cyanoacrylate may be considered an alternative for stabilization of FGG. 13

The healing of periodontal flaps using silk sutures and cyanoacrylate through microscopical observation was evaluated, and cyanoacrylate glue showed less inflammation during the first week, compared with suture thread; over a period of 21 days to 6 weeks, both surgical glue and suture showed similar healing patterns. So, it can be said that cyanoacrylate promotes and assists the initial healing phase. 9

Fibrin sealant can be a better alternative to sutures for periodontal flap surgery, since clinical observations show better healing in fibrin sealant site (on day 7) and, histologically mature epithelium and connective tissue formation, with increased density of fibroblasts and mature collagen fibres. The suture site had a greater number of inflammatory cells and blood vessels. 7

No statistically significant differences were found between the cyanoacrylate and suture in reported pain level, analgesic intake and Modified Early‐wound Healing Index. Because cyanoacrylate acts similarly to sutures, it can be used for wound closure of the donor site of subepithelial connective tissue graft, with the perk that its application is about 5 minutes faster than conventional suture placement, reducing the total time of the surgical procedure. 10

4.2. Third molar surgery

Third molar surgery was performed by Ghoreishian et al. (2009) on 16 patients with bone impaction in two phases, 4 weeks apart, under local anaesthesia. The results of their study suggested that the efficacies of cyanoacrylate and suture in wound closure were similar in pain severity, but the use of cyanoacrylate resulted in better haemostasis. Postoperative bleeding with cyanoacrylate method was less significant than with suture on the first and second days after surgery, and there was no significant difference in pain severity between the two methods. 15

Wound closure was performed after extraction with fibrin sealant on the study side and compared with suture on the control side, with a time gap between surgery on each side of 3 weeks to avoid overlap of postoperative symptoms. The fibrin sealant group demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the duration to achieve haemostasis and wound closure versus the control group, as well as significantly reduced pain scores and increased mouth opening after surgery. No adverse effects of fibrin sealant were observed. For that reason, it was concluded that fibrin sealant is a superior intraoral closure and haemostatic agent, being a worthy alternative to suturing. 2

Joshi et al. (2011) compared the effectiveness of cyanoacrylate placement with conventional silk suture technique for wound closure after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars and assessed the incidence of postoperative sequelae of haemorrhage and pain. Postoperative haemorrhage with the cyanoacrylate method was less significant than with suture on the first and second days after surgery, and there was no significant difference in pain severity between the two methods. Therefore, this study suggested that the effectiveness of both cyanoacrylate and suturing in wound closure were similar in pain severity, but the use of cyanoacrylate showed better haemostasis. 11

In a study conducted in 60 participants who were split into control group (silk suture thread) and study group (cyanoacrylate surgical glue) and followed through a 7‐week period, no significant difference in the parameters evaluated was found, excepting postoperative bleeding, in which the control group had a statistically significant difference greater than the study group. For that reason, cyanoacrylate surgical glue compares favourably with silk suture as wound synthesis materials and appears to have beneficial haemostatic effects on postsurgical bleeding. 6