Abstract

Intrinsically disordered protein regions exist in a collection of dynamic interconverting conformations that lack a stable three-dimensional structure. These regions are structurally heterogeneous, ubiquitous, and found across all kingdoms of life. Despite the absence of a defined 3D structure, disordered regions are essential for cellular processes ranging from transcriptional control and cell signalling to sub-cellular organization. Through their conformational malleability and adaptability, disordered regions extend the repertoire of macromolecular interactions and are readily tunable by their structural and chemical context, making them ideal responders to regulatory cues. Recent work has led to major advances in understanding the link between protein sequence and conformational behaviour in disordered regions, yet the link between sequence and molecular function is less well-defined. Here, we consider the biochemical and biophysical foundations that underlie how and why disordered regions can engage in productive cellular functions, provide examples of emerging concepts, and discuss how protein disorder contributes to intracellular information processing and regulation of cellular function.

Introduction

Molecular interactions directly determine cellular fate and function. Proteins are the central conduits for the reception, processing, and transmission of cellular information, a collection of activities we refer to as ‘molecular communication’. Proteins often control biological function through well-structured molecular interactions mediated by folded domains. However, many proteins also possess intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)1-5, protein domains that can mediate essential cellular interactions without long-lived (stable) structures.

IDRs are defined by an amino acid sequence that gives rise to dynamic polypeptide chains unable to acquire a stable tertiary structure3. This inability to fold often reflects an insufficient proportion of hydrophobic amino acids to form a hydrophobic core. Despite the absence of a well-defined 3D structure, IDRs are essential for cellular function. They are found across all cellular locations, from integral membrane proteins to soluble cytoplasmic proteins to chromatin-associated proteins (Fig. 1). They function in cellular processes including but not limited to transcription, translation, signalling, cell division, genome maintenance, immune surveillance, circadian biology, and cellular homeostasis6-15. On the molecular scale, IDRs can function as flexible linkers, as tunable modules for molecular recognition, as binding interfaces for simultaneous interactions with multiple partners, as cellular sensors, and as drivers of subcellular organization3,16-22. IDRs range in length from short (5-10 residue) to long (1000+ residue) regions, and can exist as tails, linkers, and loops. Along an IDR, distinct sequence properties can be concentrated in specific parts of the sequence, enabling discrete molecular functions to co-exist in a single IDR23-25. While serving a variety of functions, a common feature shared by many IDRs is their ability to enable multivalent, tunable, and malleable molecular recognition that would otherwise be challenging to mediate via folded domains. In this way, IDRs offer a route to enhance and expand molecular communication.

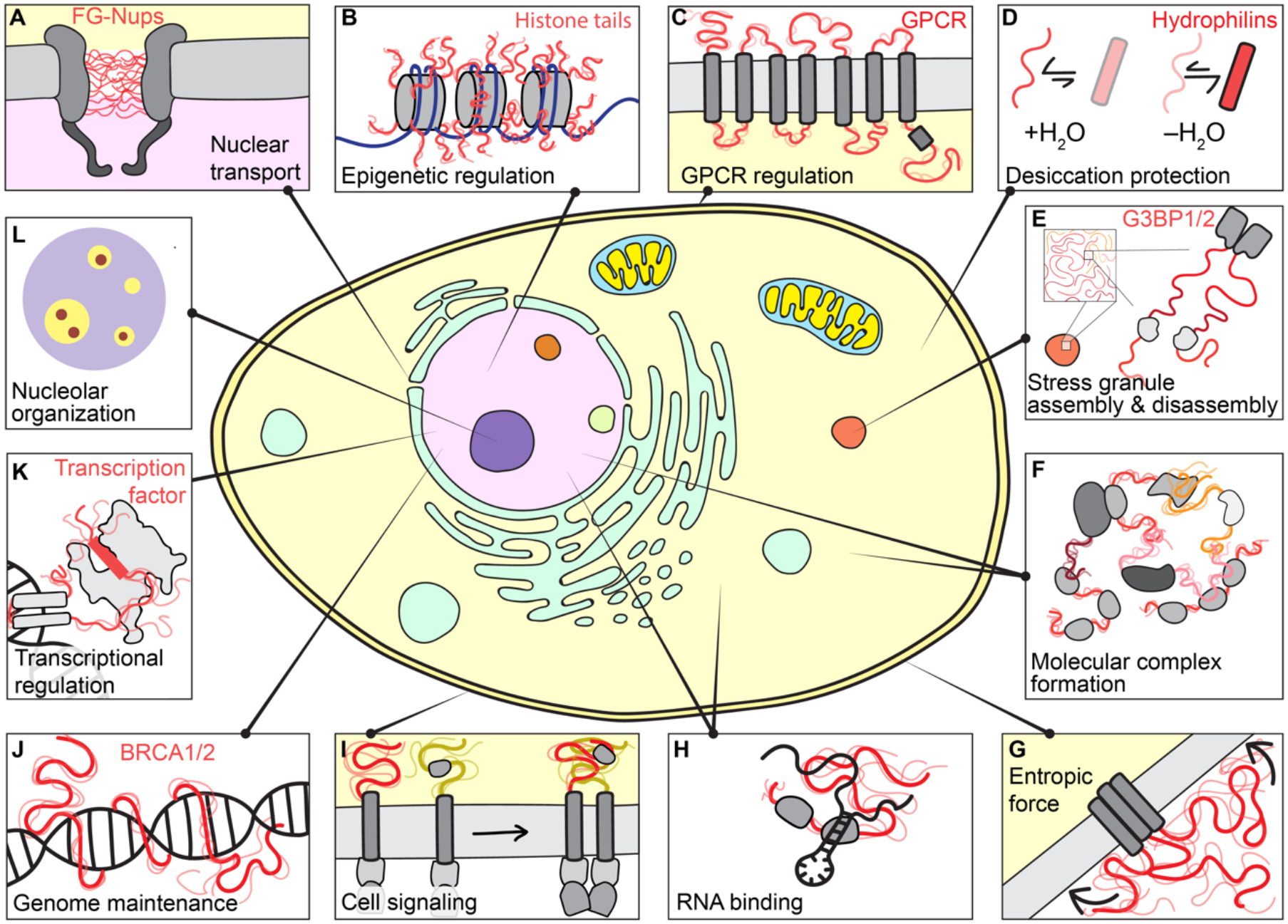

Figure 1: IDRs are central to cellular function.

IDRs play critical cellular roles across cellular compartments. From top left clockwise. (a) The nuclear pore complex is a macromolecular portal that controls the partitioning of biomolecules between the nucleus and cytosol and regulate passage through the nuclear envelope. The central lumen of its pore is filled with a chemically-tuned meshwork of IDRs — phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats — from nucleoporin (Nup) proteins that enable selectivity through favourable transient interactions with nuclear transport receptors. (b) Histones are among the most abundant proteins in Eukaryotes and act as positively charged counterions to compact negative DNA into chromatin. Histone tails are IDRs that undergo extensive post-translational modification (PTM), enabling both changes to the intrinsic biophysical behaviour and the recruitment or exclusion of partner proteins to determine epigenetic state. (c) G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a large class of membrane-bound receptors that transduce extracellular stimuli into chemical information. Many GPCRs contain IDRs in their intracellular and extracellular loops and tails. These IDRs are highly variable in composition and length, suggesting they may act as evolutionary-labile sensors connected to a more conserved signal-transduction machine. (d) For many organisms, resilience to low levels of water is among the strongest selective pressures. Most identified desiccation-resistance proteins (e.g., hydrophilins, CAHS proteins etc.) are disordered when in aqueous environments, although many also acquire helicity upon desiccation. The molecular details that underlie how and why disordered proteins appear to play key roles in desiccation tolerance remains enigmatic. (e) Stress granules are an evolutionarily conserved class of cytoplasmic condensate that form in response to cellular stress. In humans, stress granule formation often depends on the largely disordered paralogous proteins G3BP1/2. More broadly, however, many core stress granule proteins contain large IDRs, potentially related to their roles in RNA binding and environmental responsiveness. (f) IDRs are often found in multidomain proteins that facilitate the formation of large dynamic macromolecular complexes. In these, they may act as flexible linkers connecting folded domains, or as molecular recognition modules that facilitate complex formation. (g) IDRs can exert entropic force, here shown in membrane proteins. Any reduction in available volume of an IDR – for example, by the presence of an adj acent membrane – results in a corresponding force proportional to the entropic cost levied by the lost volume (highlighted by arrows). (h) IDRs are often found in RNA binding proteins. They can bind RNA directly and can enhance or suppress the binding affinity of canonical RNA binding domains. Given the size mismatch between mRNA and most proteins, productive RNA recognition events may require the collective behaviour of many proteins, and IDRs may contribute to both protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions. (i) Transmembrane signalling proteins (e.g., T-cell receptors, cytokine receptors, and growth factor receptors) often contain intracellular disordered regions that contribute to signal amplification upon receptor clustering. These regions can interact with other IDRs, act as a platform upon which downstream signalling molecules can co-assemble or undergo PTMs (especially phosphorylation) to indicate signalling status. (j) Genome maintenance represents an essential set of cellular programmes conserved from yeast to humans. Many of the core proteins that drive central steps in different aspects of genome maintenance contain large IDRs with important cellular functions (e.g., p53, BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, MLH, XPA). These IDRs may aid in the coordination of DNA repair by recruiting other proteins but may also interact directly with DNA. (k) Transcription factors are DNA-binding proteins that dictate the set of genes being expressed at any given moment. Most transcription factors contain IDRs. In addition to mediating the recruitment of appropriate partner proteins – which also typically contain IDRs – to activate or repress gene expression (often via folding-upon binding), emerging work suggests transcription factor IDRs can even guide the specific of transcription factors for DNA sequences. (l) Biomolecular condensates are membrane-less non-stochiometric assemblies that concentrate specific biomolecules and exclude others. IDRs, owing to their multivalency, can participate in phase transitions associated with biomolecular condensate formation. In particular, the nucleolar substructure observed in vitro and in vivo is coordinated at least in part by sequence features in IDRs. These observations illustrate how mesoscopic organization can emerge despite disorder at the level of individual molecules.

Protein disorder is ubiquitous across the kingdoms of life. In eukaryotic proteomes, 30-40% of residues are in IDRs, with a similar fraction in many viruses25,26. An entire protein can be disordered, in which case the protein is referred to as an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP). However, most protein disorder is found in IDRs positioned terminally (tails) or connecting two folded domains (linkers) (Fig. 2a and Box 1). Around 70% of proteins in the human proteome possess one or more IDRs of 30 residues or longer (see Box 1). While prokaryotes contain fewer IDRs (see Box 1), emerging work suggests these also play key roles27.

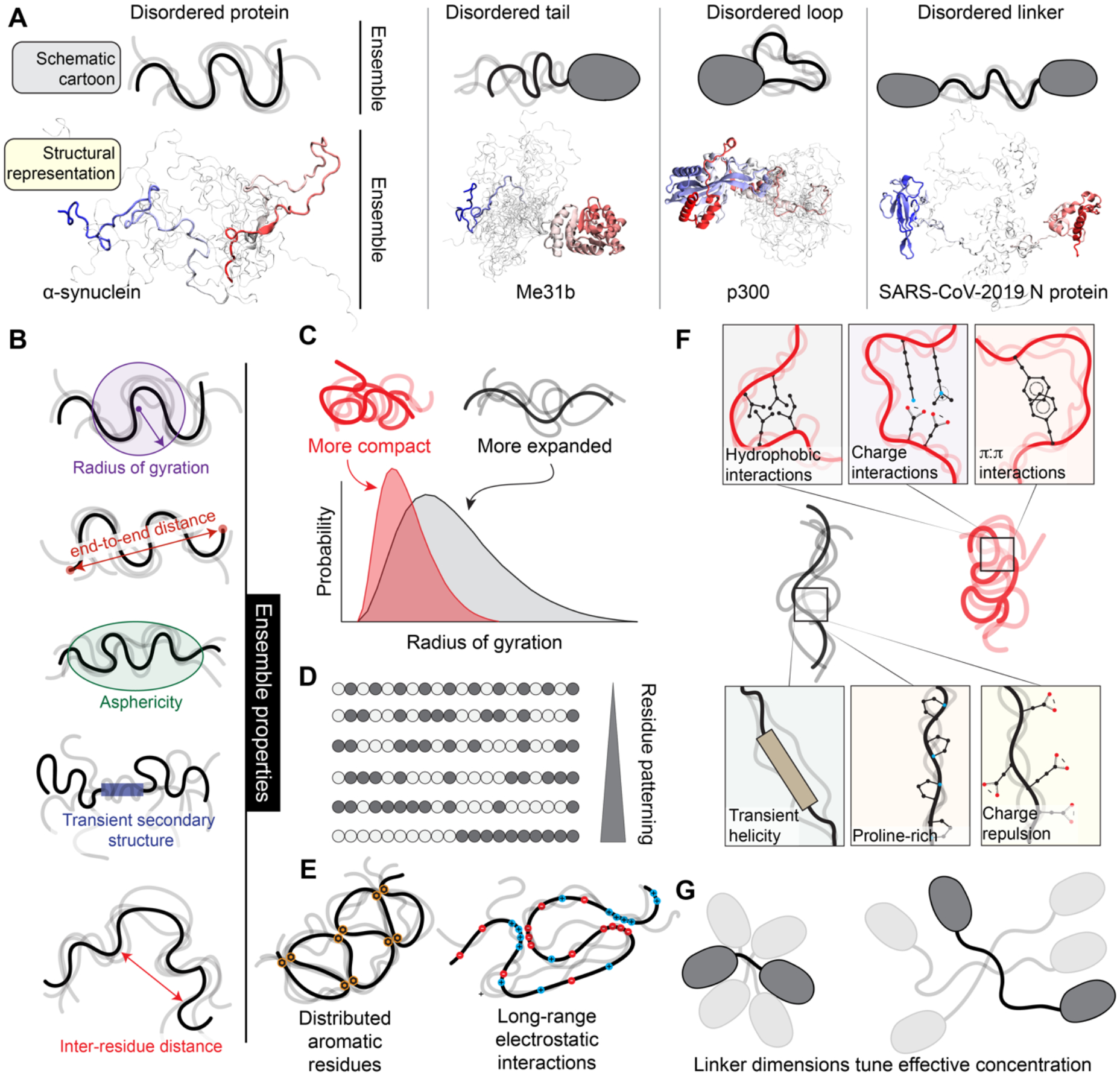

Figure 2: IDRs exist in ensembles dictated by protein sequence features.

(a). IDRs exist in ensembles — a collection of dynamic conformations that are energetically accessible to a disordered region. Although folded domains also exist in ensembles, the conformations associated with a folded domain are typically structurally similar. By contrast, for IDRs, ensemble conformations are highly heterogeneous. Here we compare structural models for IDR ensembles in different molecular contexts (bottom) with schematized representations of IDR ensembles (top). Only a small number of separate conformations are shown for visual accessibility, however in reality, IDRs exchange between tens of thousands of different conformations. The four proteins depicted here are examples of IDRs from either a fully disordered protein (furthest left) or IDRs in different structural contexts. In each representation, one specific conformation is highlighted, and a collection of additional conformations are superimposed in shaded lines, with the goal of illustrating the structural heterogeneity associated with an ensemble. For a clearer demonstration of an ensemble, see Movie M1, a rendering from an all-atom simulation of the low complexity domain from the RNA binding protein hnRNPA1 (see Box 1). PDB codes for structures: left (homology model based on PDB:4CT5), centre (PDB:6GYR), right (PBD: 6YI3); note disordered regions are not visible in deposited PDB structures. (b) Because IDRs exist in ensembles, they cannot be represented by a single 3D structure. Consequently, IDR ensembles are described in terms of ensemble properties: specific metrics that can be measured, calculated, or predicted for the collection of conformations to quantify the ensemble. Commonly used ensemble properties include the radius of gyration and the end-to-end distance (measures of global ensemble dimensions), asphericity (a measure of ensemble shape), transient secondary structure (a measure of local structural acquisition) and inter-residue distances (a measure of specific ensemble dimensions). These properties can be calculated from simulations or measured experimentally (see Box 2). (c) IDR ensemble properties should ideally be described in terms of probability distributions. For example, the distribution of the radius of gyration is shown for two IDRs. One IDR (red) is compact, while the other IDR (black) is more expanded. (d) IDR ensembles often depend on residue patterning, which quantifies how segregated/clustered residues of one chemical group (here depicted as white or grey beads) are with respect to another. (e) Local sequence properties can influence IDR ensembles, such as charge patterning (left) and evenly spaced aromatic residues (right). (f) Overall, IDR ensemble properties are a consequence of the sequence-encoded physical chemistry and the context-dependence of interactions endowed by that physical chemistry. (g) Ensemble properties of IDR linkers tune the effective concentration of folded domains to one another. Two folded domains connected by a short IDR are inherently close to one another, yet if long IDRs are relatively compact, folded domains will remain close, despite the superficially “large” intervening disordered linker (see panel 2c). For two domains that interact with one another, linker properties (modulated via post-translational modifications or changes in linker sequence over evolution) can therefore tune inter-domain communication, thereby influencing local inhibition or activation or altering binding affinity for target molecules.

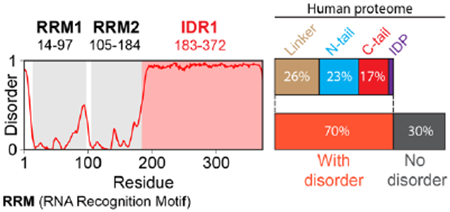

Box 1. Identifying IDRs.

Early work on IDRs was driven by bioinformatics, with initial predictors enabling disordered and folded domains to be delineated 391-394 Over the last twenty-five years, disorder predictors have become increasingly accurate. In 2021, the first Critical Assessment of Intrinsic Disorder (CAID) competition was held, comparing different predictors in terms of accuracy and performance51. Based on results from the most recent CAID competition, the accuracy among the top ten predictors is similar, with AlphaFold2 also performing well52. Predictors have also gotten faster. For example, using one of the top-performing predictors, metapredict V2-FF, all IDRs in the human proteome can be predicted in a few minutes24,395. Disorder predictors provide a linear assessment of whether a residue falls within a disordered region or not (see figure, disorder profile for the human RNA binding protein hnRNPAl; RNA Recognition Motifs [RRMs] are folded domains). Proteome-wide analysis with metapredict (V2-FF) reveals that across the human proteome, ~40% of proteins have IDRs that are 100 residues or longer (18,074 IDRs), and ~70% of proteins possess IDRs that are 30 residues or longer (29,698 IDRs). Of those 29,698 IDRs, ~37% are linkers, ~34% are N-terminal tails, ~25% are C-terminal tails, and the remainder are fully disordered proteins. Such proteome-wide analyses have helped reveal that IDRs are common in eukaryotes and viruses while generally less common in bacteria and archaea26.

In addition to predicting IDRs, a repository of known SLiMs exist in the Eukaryotic Linear Motif Resource 264 Although the number of known SLiMs now approaches the thousands, it is estimated that up to 100,000 different SLiMs could exist255. While consensus SLiMs can be identified from sequence, whether these function as bona fide SLiMs typically requires direct experimental validation, highlighting the importance of context in licensing SLiM function.

Instead of a stable 3D structure, IDRs exist in a collection of rapidly interconverting structurally distinct conformations known as an ensemble (Fig. 2a,b, Movie M1)2,28,29. An ensemble can be considered the landscape of accessible IDR conformations. Although folded domains also exist in ensembles, these are typically much less structurally heterogeneous than those of IDRs30. Moreover, while it is convenient to discuss IDRs and folded domains as distinct entities, in reality, they exist along a continuum of structural heterogeneity31. Just as structure and folds (e.g., four-helix bundle, β-barrel) can quantitatively describe a folded domain, an IDR can be quantitatively described by its ensemble properties32-34

Ensemble properties are quantifiable parameters that describe 3D features derived from the ensemble. They include global IDR dimensions (i.e., how expanded or compact the protein conformations in an ensemble are), local transient structure (i.e., lowly populated helices and extended conformations), and inter-residue distances (Fig. 2b). IDR global dimensions are often quantified by the radius of gyration, end-to-end distance, or hydrodynamic radius. Importantly, ensemble properties are determined by molecular interactions encoded by the IDR sequence and its context (discussed below) and can be determined using experimental and computational approaches (see Box 2).

Box 2. Characterizing IDRs.

Experimental characterization of IDR ensemble properties can be achieved via a range of experimental approaches. Measuring residue-specific interactions relies on techniques that provide residue-specific information. These include NMR spectroscopy396,397, single-molecule Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) with specific positions labeled398,399, and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry400. NMR and smFRET also enable global, ensemble properties to be measured401,402, as do additional techniques, including ensemble FRET120, small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)403-405, dynamic light scattering (DLS)18, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS)406, circular dichroism (CD)407, and collision cross-section mass spectrometry (CCS-MS)408. While measuring both local (e.g. helicity, NMR chemical shifts) and global (e.g. radius of gyration, end-to-end distance) IDR ensemble properties for the same IDR can be time-consuming and challenging, integrative biophysical studies — in which several methods measure distinct properties of a single IDR — have played key roles in developing our current understanding of sequence-ensemble relationships32,57,61,64,87,246,402,409-415.

Computational characterization of IDR ensembles has been essential in understanding sequence-to-ensemble relationships416. Computational approaches can generally be classified as either top-down or bottom-up. Bottom-up approaches offer predictions of ensemble properties without experimental data. Top-down approaches take experimental data and construct ensembles consistent with those data. For bottom-up approaches, molecular simulations at a range of resolutions have proven invaluable64,112,113,117,410,411,417,418. While – historically speaking – many all-atom forcefields lead to the over-compaction of IDRs, recent efforts to address this weakness have led to major improvements419-425. In parallel, improvements in coarse-grained forcefields have also enabled rapid characterization of ensemble properties 335,426-429. In a recent preprint, ensemble properties of all IDRs in the human proteome were calculated from coarse-grained simulations60, while instantaneous predictions of global dimensions using deep learning based approaches trained on coarse-grained simulations enable ensemble properties (e.g., radius of gyration, end-to-end distance) to be predicted directly from sequence in milliseconds 24. For top-down approaches, tools including flexible-meccano430 and EOM431 for building ensembles from experimental data and various approaches for selecting an ensemble from the larger set of conformations and reweighting to optimize correspondence with the experimental data (e.g., ASTEROIDS432, Bayesian inference433,434, maximum entropy approaches435, metainference436, and deep learning437) have been applied to construct experimentally consistent ensembles at atomistic resolution438,439.

IDR ensemble properties can play key roles in biological function33. For example, transient secondary structure can predispose an IDR to bind a specific partner and play important roles in binding energetics21,35,36. In other instances, the average end-to-end distance of an IDR that connects two folded domains may position these at a functionally-relevant average distance from one another37-40. As a corollary, the modulation of ensemble properties can influence cellular function. Understanding that IDRs are defined by sequence-specific ensembles with unique physicochemical features acknowledges that ensemble properties can alter in response to molecular interactions, changes in the cellular environment, or post-translational modifications (PTMs).

Ensemble properties are best described in terms of probability distributions (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, IDR ensembles can possess well-defined structural and conformational preferences encoded by the underlying protein sequence, biasing them towards certain functionally relevant conformations or average ensemble properties. Just as folded proteins have a sequence-structure-function relationship, IDRs possess an analogous sequence-ensemble-function relationship, where that ensemble can be quantified in terms of ensemble properties (Fig. 2b, c).

The ensemble properties of an IDR depend on both the IDR sequence and its context. We define context as i) the local solution context, i.e., the proximity to other biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, small molecules, etc.), solution temperature, presence of osmolytes or ions, ii) the chemical context of the IDR, namely PTMs and changes in pH leading to protonation and deprotonation effects41, and iii) the structural context, i.e., the presence or absence of adjacent folded domains. Moreover, the binding of IDRs to ligands – be they other proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids, metal ions, carbohydrates, or other molecules – can influence ensemble properties and contribute to context42-45. While context can also alter folded domain ensembles, the absence of a network of stable intramolecular contacts in IDRs means they are generally more sensitive to changes in context46. Given that contexts can alter IDR ensemble properties in various ways, and changes in ensemble properties can be synergistic or antagonistic to specific functions, it stands to reason that IDR function can be tuned or even completely rewired by different combinations of ensemble-influencing perturbations. This allows IDRs to integrate complex signalling cascades and crosstalk across many cellular input pathways.

The molecular details that underlie how IDRs confer biological function are, in many cases, opaque. This knowledge gap partly stems from the need to integrate molecular biophysics and cell biology to fully interpret how function emerges, e.g., sequence-specific effects may alter IDR ensembles and hence function. In this Review, we aim to provide the conceptual tools needed to tease apart the molecular basis for IDR-mediated cellular function and regulation.

Sequence-to-Ensemble Relationships in IDRs

The relative deficiency of hydrophobic amino acids in many IDRs means their sequence composition often differs from folded proteins. It is therefore possible to assess the probability of a region being disordered from its sequence alone. Indeed, many accurate and robust disorder predictors have emerged over the years (see Box 1). Moreover, recent advances in structure prediction have provided a convenient corollary to disorder prediction; the absence of a predicted structure from tools such as AlphaFold2 (refs. 47,48) and trRosetta49 implicates a region as being disordered (although the resulting structure predicted by these tools should not be taken as a faithful prediction of the ensemble properties50). As a result, IDRs can generally be confidently identified from the amino acid sequence51,52.

Unconstrained by the requirement to fold into a 3D structure, paralogous and orthologous IDR sequences can be highly variable across evolution (see Box 3)53-55. This can make sequence alignment difficult and often misleading, necessitating alternative routes to measure conservation38,55-59. In particular, the underlying physical chemistry encoded by an IDR sequence dictates the resulting ensemble, and the properties of the ensemble can dictate function. Thus, one approach for understanding conservation and function in IDRs is by considering if and how ensemble properties might contribute to function, enabling the decoding of sequence-ensemble-function relationships24,38,60.

Box 3. The Evolution of IDRs.

IDRs often show poor sequence conservation when assessed by alignment-based metrics53,54,178,440,441. This poor conservation could be interpreted as a lack of important cellular function, yet the realization that IDRs play many critical roles in molecular and cellular biology invalidates this interpretation. An emerging paradigm suggests that conservation in IDRs can operate at the level of sequence features as opposed to on specific amino acid sequences38,55-58,72,92,174,178,442. If the conserved features include SLiMs, these may ‘diffuse’ around within an IDR, such that even if a SLiM is well-conserved, its relative or absolute position need not be 178,179. IDRs in which certain regions are highly conserved, as based on multiple sequence alignment, may reflect evolutionary coupling between that region and a folded partner, whereby the rate of change for this region has been slowed to match the partner’s surface, as shown recently for the bacterial tubulin homolog FtsZ442-444. Alternatively, variation in IDR sequences across evolutionary timescales may lead to compensatory changes in protein interaction networks, such that the overall function of a cellular programme is preserved even as individual disordered regions change445.

There are at least two related possible reasons for the limited sequence conservation observed in IDRs. First, because IDRs lack a specific 3D structure, they are not sensitive to (i) destabilizing mutations, (ii) mutations that impact folding pathways, or (iii) mutations that disrupt specific finely tuned allosteric networks. By contrast, in the case of folded domains, mutations can impact all three of these. As an example, mutations across enzymes can have a substantial impact on their function by altering stability, folding, and/or allosterically regulating function446,447. In effect, a stable 3D structure imparts a tight and cooperative coupling between sequence, fold, and function, and its absence loosens this coupling. Second, as discussed in the main text, IDR-mediated functions often depend on sequence features instead of specific sequences. Given that natural selection operates on the level of function, not on sequence, two IDRs with equivalent functionality are equally fit, regardless of how similar their sequences are. In this way, combining IDR sequence analysis with evolutionary analysis is one route to aid in identifying sequence features that may be important for molecular function55,59,92,178,263.

Amino Acid Physical Chemistry Defines Sequence-to-Ensemble Relationships

The twenty natural amino acids offer a chemically diverse set of building blocks to encode distinct ensemble properties33,34,61. The relative abundance and position of different amino acids are often called sequence features. For sequence-ensemble relationships, certain sequence features are more influential than others. The number, charge, and relative positioning – termed patterning – of charged residues are key determinants of ensemble properties in IDRs providing repulsive and attractive electrostatic interactions coupled with favourable free energies of solvation (Fig. 2d, e, f)58,62-70. Aromatic residues can engage in intramolecular interactions driven by their sidechain π:π interactions (π-electrons), cations:π interactions (with arginine, lysine, and protonated histidine), methyl:π interactions, or hydrophobic interactions (with aliphatic residues) (Fig. 2e, 2f)57,71-73. Aliphatic residues can drive intramolecular interactions via the hydrophobic effect and desolvation, whereas polar residues can engage in hydrogen bonds or dipole-dipole interactions18,74-76. Finally, due in part to steric effects, proline residues generally make chain dimensions more expanded than they would otherwise be, and, along with glycine, suppress transient helicity and β-strand formation61,63,77-80. In all cases, the clustering and patterning of these different residues can impact ensemble properties57,61,81-83. In addition to genetically-encoded sequence biases, IDRs are disproportionately post-translationally modified compared to folded domains84,85. By dynamically re-writing sequence chemistry through PTMs, IDR ensembles can be modulated in a reversible and controllable way86-90. In summary, sequence features can be quantified via recently established sequence parameters, enabling comparison between IDRs without reliance on (often impossible) sequence alignments4,25,34,55,91-93.

Sequence features – and hence ensemble properties – can be used for comparisons, evolutionary analysis, and quantitative predictions relevant to understanding IDR function55,56,92,94-96. For example, the C-terminal IDR in the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 protein PSC is essential, poorly conserved as assessed by sequence alignments, yet highly conserved in terms of disorder and charge properties, highlighting the potential for function to be maintained with minimal sequence conservation58. More broadly, the preservation of overall charge or charge clusters in seemingly divergent IDRs has been used to explain functional conservation across evolutionary lineages or between seemingly unrelated proteins59,97-101. Finally, changes in IDR sequence features can compensate for evolutionary changes in IDR length, if ensemble properties are conserved. For example, in a linker IDR from the Adenovirus protein E1A, the fraction of proline and negatively-charged residues decreases as the linker sequence becomes longer (more residues), such that the global dimensions of the linker are conserved, a phenomenon termed conformational buffering38.

Attractive and Repulsive Intramolecular Interactions Determine Ensemble Properties

Attractive or repulsive intra-molecular interactions encoded by IDR sequence features can influence ensemble properties (Fig. 2b). These effects can be local or global and can act synergistically or antagonistically, with consequences for IDR-associated function.

Local lowly-populated (10-30%) helicity is common in IDRs, and is driven by local sequence features that stabilize the network of backbone hydrogen bonds found in α-helices17,21,102-106 Transient helicity can orientate sidechains to pre-organize binding interfaces. For example, the N-terminal disordered region of the androgen receptor can bind small molecules via two transiently-formed helical regions that arrange hydrophobic sidechains in a way that let them sandwich and bind small hydrophobic molecules107. In some systems, transient helicity appears to be evolutionarily tuned, in others, it determines molecular specificity. While the presence of transient helicity does not necessarily imply functional significance, conserved elements that form transient helices – especially those with aliphatic or aromatic residues along the helix face – often appear as functionally important elements within IDRs. The importance of transient helicity is further underscored by the fact that mutations that modulate helicity can lead to disease21,35,104,108-110.

Attractive and repulsive interactions along the IDR chain can lead to global chain compaction or expansion, driven by different chemical origins 24,33,60. Compaction here refers to a scenario in which an ensemble has a smaller global dimensions that expected by chance, whereas expansion means the ensemble is larger than expected by chance. Evenly-distributed aromatic or hydrophobic residues can drive labile attractive intramolecular interactions, as is seen in many low-complexity prion-like domains (Fig. 2e, left)18,57,72,76,111-113. Alternatively, clusters of oppositely charged residues can interact through long-range electrostatic attraction, as can aromatic and arginine residues (Fig. 2e, right)72,81-83,114,115. Finally, long repeats of some polar amino acids can lead to chain compaction via local dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding. In the case of polyglutamine (polyQ), a combination of helix formation and long-range intramolecular dipole interactions appears to govern global chain dimensions74,116-119. However, other polar tracts (e.g., glycine-serine repeats) behave as flexible chains that are neither overly compact nor expanded120,121. Chain compaction serves various functional roles, including modulating accessibility of binding motifs122 or enhancing the local concentration of adhesive interactions that can drive the formation of biomolecular condensates (discussed in the section IDRs and Biomolecular Condensates )18,57,123.

In addition to attractive interactions, some IDRs are enriched in residues that minimize intra-molecular interactions61,78,124,125. These self-avoiding IDRs serve various roles. For linker IDRs that connect folded domains, linker length and sequence features influence the interaction between the folded domains. By setting the effective concentration of the folded domains for one another, dynamic and flexible (or compact) linkers enhance inter-domain interactions in a length-dependent manner, while expanded linkers suppress inter-domain interaction (Fig. 2g)37,38,69,121,126,127. These effects can be regulated by PTMs, offering a route to tune interdomain interaction22,37,128. Changing the effective concentration of two folded domains can tune partner binding129, impact autophosphorylation22, and alter allosteric communication between folded domains40,130,131. Self-avoiding IDRs can also serve scaffolding roles, as seen for the disordered tail of the transmembrane protein LAT, onto which several SH2 domains can bind at defined distances132, or in the growth hormone receptor133. Finally, IDRs can exert an entropic force. This is an intermolecular effect, whereby a reduction in the volume accessible to an IDR-ensemble causes it to “push” against any molecular components that reduce its volume134. Given the generated entropic force is proportional to the loss of ensemble volume, IDR chain dimensions can tune the strength of the force by altering the volume occupied by the ensemble124,134,135. This entropic force can tune binding events124, sense/influence membrane curvature125,135,136, or even enable entropy-driven translocation of IDRs through bacterial cell walls137.

IDRs in Context

Many IDRs function by engaging in intermolecular interactions with other biomolecules. IDRs can interact in various ways (discussed in the following two sections). These include but are not limited to (i) sequence motifs composed of ~5 – 12 residue elements that encode sequence-specific recognition modules recurrent in many different and even unrelated proteins, known as Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs)138, (ii) multivalent interactions driven by specific sequence features (e.g., distributed aromatic residues or clusters of positively charged residues), (iii) folding-upon-binding to an appropriate partner, or (iv) some combination of these. IDRs can be highly multivalent, with several SLiMs or repeats orchestrating higher-order complexes, as seen in signalling hubs13. Moreover, IDRs may possess repetitive features that encode multivalency and lead to the formation of biomolecular condensates (discussed in the section IDRs and Biomolecular Condensates )139-141. Intra- and intermolecular interactions driven by IDRs can be suppressed or enhanced by changes in context that affect the physical chemistry of the amino acid residues (Fig. 3a-f). These changes in context can be transient or long-lived and can emerge from various origins.

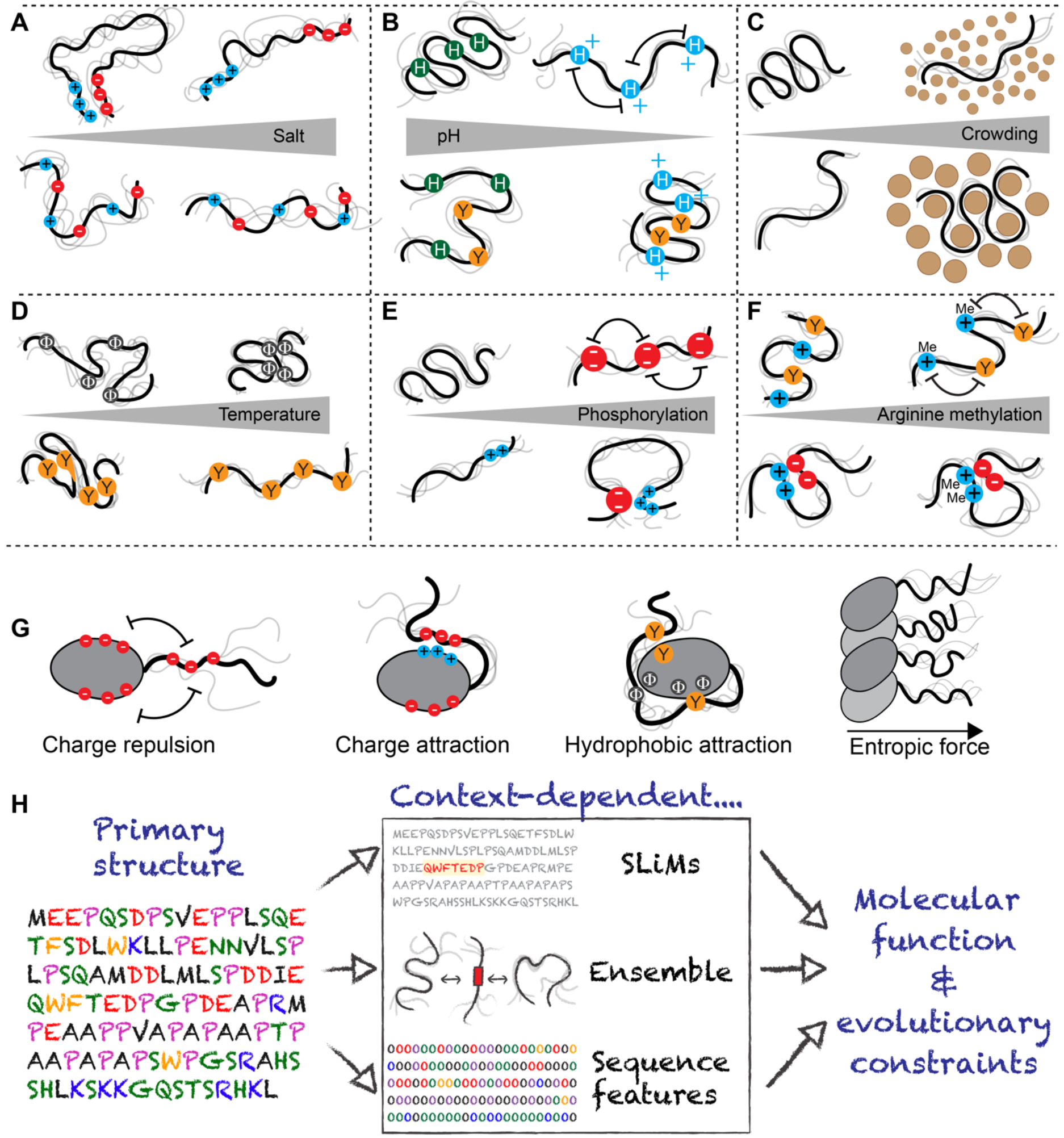

Figure 3: IDR ensemble properties are context dependent.

Behaviour of the IDR ensemble is highly context dependent. (a) Highly charged IDRs can be sensitive to changes in salt, although how salt influences ensemble properties depend on the IDR sequence features and the salt. If IDRs possess clusters of oppositely charged residues, these clusters can interact with one another driving chain compaction, an effect that is reduced as salt concentration is increased (top). By contrast, if charged residues are uniformly patterned, an increase in salt concentration may have a comparatively modest impact on IDR dimensions as no strong intramolecular interactions are found (bottom). Finally, divalent ions can bind to clusters of negatively charged residues with effects on local and global compaction (not shown). (b) Changes in pH can influence IDRs with amino acids that may be protonated (Asp, Glu, His) or deprotonated (Lys, Tyr, Arg, His) within physiological regimes. As a note, arginine deprotonation would seem to be almost impossible under physiological conditions. For uncharged IDRs with many histidine residues, a reduction in pH can lead to histidine protonation, driving intramolecular repulsion and leading to chain expansion (top). Conversely, if an IDR contains histidine and aromatic residues, protonation can lead to strong cations interactions between positively charged histidine and aromatic residues, driving chain compaction (bottom). (c) IDR dimensions respond to crowders differently; if crowders have weakly favourable non-specific interactions with IDRs then small crowders can drive IDR expansion while large crowders drive compaction. As a result, some IDRs may be well-poised to act as sensors of cellular crowding on specific length scales. (d) IDRs are sensitive to changes in temperature. For IDRs enriched in aliphatic hydrophobic residues (i.e., valine, leucine, isoleucine, methionine, alanine), the enhanced strength of the hydrophobic effect at higher temperatures leads to chain compaction (top). For IDRs enriched in aromatic residues, π:π interactions are enthalpically dominated, such that as temperature increases π:π interactions become weaker, and these chains become more expanded (bottom), and for IDRs in general, there is a loss of polyproline-II structures - an extended left-handed secondary structure that usually but not necessarily involves prolines - with temperature, leading to compaction. (e) Phosphorylation can have opposing effects on IDR dimensions. Phosphorylation of an uncharged region can lead to chain expansion driven by electrostatic repulsion between phosphate groups (top). However, phosphorylation of IDRs with clusters of positively charged residues can lead to chain compaction, driven by electrostatic interactions between phosphorylated residues and residues with positively charged clusters (bottom). Both effects can occur within a single IDR. Phosphorylation also impacts local structure and can stabilize and destabilize transient helices in a position dependent manner (not shown) (f) Arginine methylation weakens cation:p interactions between arginine and aromatic groups, which could lead to an increase in IDR dimensions (top). However, methylation does not neutralize arginine, such that intramolecular interactions driven by arginine-acidic residue interactions would likely be largely unaffected. (g) As solution context can influence IDR properties, folded domains adjacent to IDRs can do so too. The impact that folded domain surface features have on IDR ensemble properties depends on the chemistry of the folded domain and the IDR sequence. From left to right: Same charged residues on a folded domain surface and an IDR will repel one another, preventing intramolecular interaction and ensuring an IDR is projected into solution, away from the folded domain. Oppositely charged residues on a folded domain surface and an IDR will attract one another, driving intramolecular interaction. Hydrophobic interactions between aliphatic and/or aromatic residues on folded domain surfaces and IDRs can lead to intradomain interaction. If many IDRs are projected from a filament formed from folded domains, inter-IDR interaction and repulsion can lead to a bottle-brush architecture and a resulting entropic force. (h) Figure summarizing a current model for IDR function. IDRs are encoded by their amino acid sequence (left). That sequence determines the presence of SLiMs (middle top), the overall ensemble (middle center) and the presence of sequence features (middle bottom). All three properties and/or their functionality are influenced by IDR context. Ultimately, these context-dependent properties dictate both molecular function and the evolutionary constraints that govern IDR sequence variation over generations.

Physicochemical context

Physicochemical context can substantially alter IDR form and function46. For example, electrostatic interactions can be screened by changes in ionic strength (ionic activity), as can occur from an influx of Ca2+, Na+, K+, or by cellular sulfation gradients142-144. Interactions can be enabled or suppressed upon protonation or deprotonation of titratable groups upon pH changes, as occurs in transit from the cytosol to endosomes, during cellular stress, or in disease states with high glycolytic activity97,145,146. Macromolecular crowding can alter IDR global dimensions, e.g., upon hyper-osmotic shock or due to enhanced ribosomal production, implicating IDRs as potential mechanosensors62,147,148. Many proteins involved in desiccation tolerance are also disordered prior to desiccation, yet acquire helicity upon desiccation149-151. Finally, IDRs often show temperature-dependent changes in their molecular interactions, an effect capitalized on by IDRs that act as cellular thermosensors, as seen in the yeast heat shock response or in cellular programs that control germination in plants18,152-156.

Post-translational modifications

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) offer another way to alter IDR context. PTMs enable covalent but reversible changes in IDR sequence chemistry, which can influence intra- and inter-molecular interactions61,67,68. Given the importance of charged residues in determining IDR global dimensions, phosphorylation (gain of negative charge) and lysine acetylation (loss of positive charge) are two examples of PTM-mediated charge changes that can directly drive expansion or compaction, and hence may impact ensemble properties, depending on how these PTMs alter IDR sequence properties and where they are positioned157,158. Phosphorylation can also enable switch-like behaviour, whereby adding a phosphate moiety substantially changes an IDR’s ensemble14,159-161. For example, phosphorylation of the stress granule protein G3BP1 alters long-range intramolecular electrostatic interactions and suppresses RNA binding114, while the protein 4E-BP2 can switch from a disordered ensemble to a stable folded state upon phosphorylation162.

Structural context

Finally, the structural context of an IDR can alter ensemble behaviour and molecular function. For IDRs connected to folded domains, the steric impact of the folded regions and their chemical makeup can significantly influence IDR ensemble properties and function (Fig. 3g)163-167. This is true for IDRs in the same polypeptide chain but also for those in multiprotein assemblies, as is the case for histone tails168,169. For example, charged patches on the surface of folded domains can enable IDR interactions if complementary charged regions are found in the IDR163,166,170. Similarly, if IDRs are found adjacent to binding sites on folded domains, they can behave as locally tethered competitive inhibitors171-173. Moreover, even IDRs that do not engage in attractive interactions but are adjacent to ligand binding sites can impede ligand binding through entropic effects. Mechanistically, this can occur if ligand binding reduces the accessible volume of the IDR, as seen for the IDR of the UDP-α-D-glucose-6-dehydrogenase124,134,174 In summary, the ensemble properties of IDRs are inherently tuned by their context such that changes in context offer a complex and multifaceted route to recode and reroute IDR function.

Sequence and context are inextricably intertwined

Ultimately, IDR function depends on sequence and context (Fig. 3h). Sequence can be viewed through two complementary lenses: (i) the sequence-encoded 3D ensemble (or 4D ensemble, if the timescales of conformational re-arrangement are considered) and (ii) the 2D (d1 = residue identity, d2 = position) sequence-encoded information, such as sequence features or SLiMs. These two lenses are not independent – IDRs with certain sequence features will reliably show certain ensemble properties – yet they provide complementary views. For example, sequence changes to a motif may have no discernible impact on ensemble properties, yet these changes may entirely abrogate function. Finally, context can impact ensemble properties and sequence-encoded information and may do so to different extents. For example, phosphorylation may alter the net charge substantially but may have no major impact on global ensemble properties61,79, or it may induce or decrease local helicity dependent on the position within the helix and its sequence. 175,176.

A challenge in studying IDRs is that the functional importance of ensemble properties vs. sequence features vs. SLiMs is system-specific. A SLiM may be essential for one function, while the IDR's overall net charge may be the most important factor for another. Moreover, two IDRs may have similar ensemble properties (e.g., similar overall ensemble dimensions) even if their sequences differ in composition or length 38,61,69,79. This redundancy leads to a much looser relationship between sequence and molecular function, raising challenges and opportunities for evolutionary analysis (see Box 3). As a result, IDRs often appear less well-conserved when assessed by linear sequence alignment53,55,177,178. Exceptions here are SLiMs, which often have conserved sequence positions, although this is not a requirement179,180. Notwithstanding these challenges, an interpretable understanding of IDR function is accessible if the underlying biochemical and biophysical principles are jointly considered.

Modes of Molecular Interactions Mediated by IDRs

Molecular recognition reflects the specific, non-covalent interaction between two different molecules. The canonical model is one in which chemical and shape complementarity cooperate to enable specific binding events, as a hand fits a glove181-183. For IDRs, where one or both interacting partners exist as disordered ensembles, the models for molecular recognition require rethinking. Indeed, as described below, IDRs may comply with known interaction models, but they also extend the possible mechanisms through which molecular recognition is achieved. In this way, IDRs expand the cell's communication toolbox by offering complementary alternatives to the traditional 1:1 model of molecular specificity.

IDRs can bind other biomolecules through three main mechanisms: (i) Coupled folding and binding, where a disordered region folds to enable shape and chemistry complementarity in the bound complex102,184,185. Coupled folding and binding may involve an entire IDR, a single subregion, or two or more locally folded anchors connected by a disordered linker 186-188. (ii) As a fuzzy complex, where a finite number of structurally distinct bound-state configurations are observed and needed for function189,190. (iii) As a fully disordered bound-state complex, where both partners remain disordered.

The delineation of binding modes in this section is convenient from a didactic standpoint. However, molecular recognition involves a continuum of binding modes and principles from multiple mechanisms will likely be relevant for any given binding event. Indeed, the same IDR can bind to different partners with different mechanisms, as seen for the C-terminal tail of RNA Polymerase II111,113,191. Moreover, binding affinity192,193, specificity194-196, and even the binding mechanism can be tuned by context, as discussed above196,197. The range of potential partners bound via different mechanisms enables context-dependent crosstalk between various cellular programs and pathways. This tunability also has the potential for errors: miscommunication driven by aberrant interactions, signifying the need for negative design principles to minimize unwanted interactions.

Coupled Folding and Binding

In coupled folding and binding, either a subregion or the entire IDR folds upon binding to a folded – or disordered - partner, typically with the involvement of a conserved SLiM (Fig. 4a)198-202. In this situation, the free energy of binding must compensate for the loss of entropy experienced upon folding a disordered chain. Compared to binding a folded partner, the magnitude of this can be fairly small (on average ~2.5 kcal mol−1)203,204, but remains within a range that can determine biological functions205. Compensation may come from enthalpic contributions from inter or intra-molecular non-covalent bond formation but could also be entropic, driven by the release of solvent from hydrophobic residues and/or the release of counterions from charged side chains 36,206,207. Coupled folding and binding can follow induced fit 102, conformational selection 208, or – as is usually the case – some combination of the two, and kinetic measurements are needed for teasing these apart209-212. Coupled folding and binding can involve various interactions, including IDR–protein, IDR–DNA, and IDR–RNA199,213-215. In many ways, coupled folding and binding is analogous to intermolecular protein folding, as opposed to the intramolecular process one typically associates with protein folding in general.

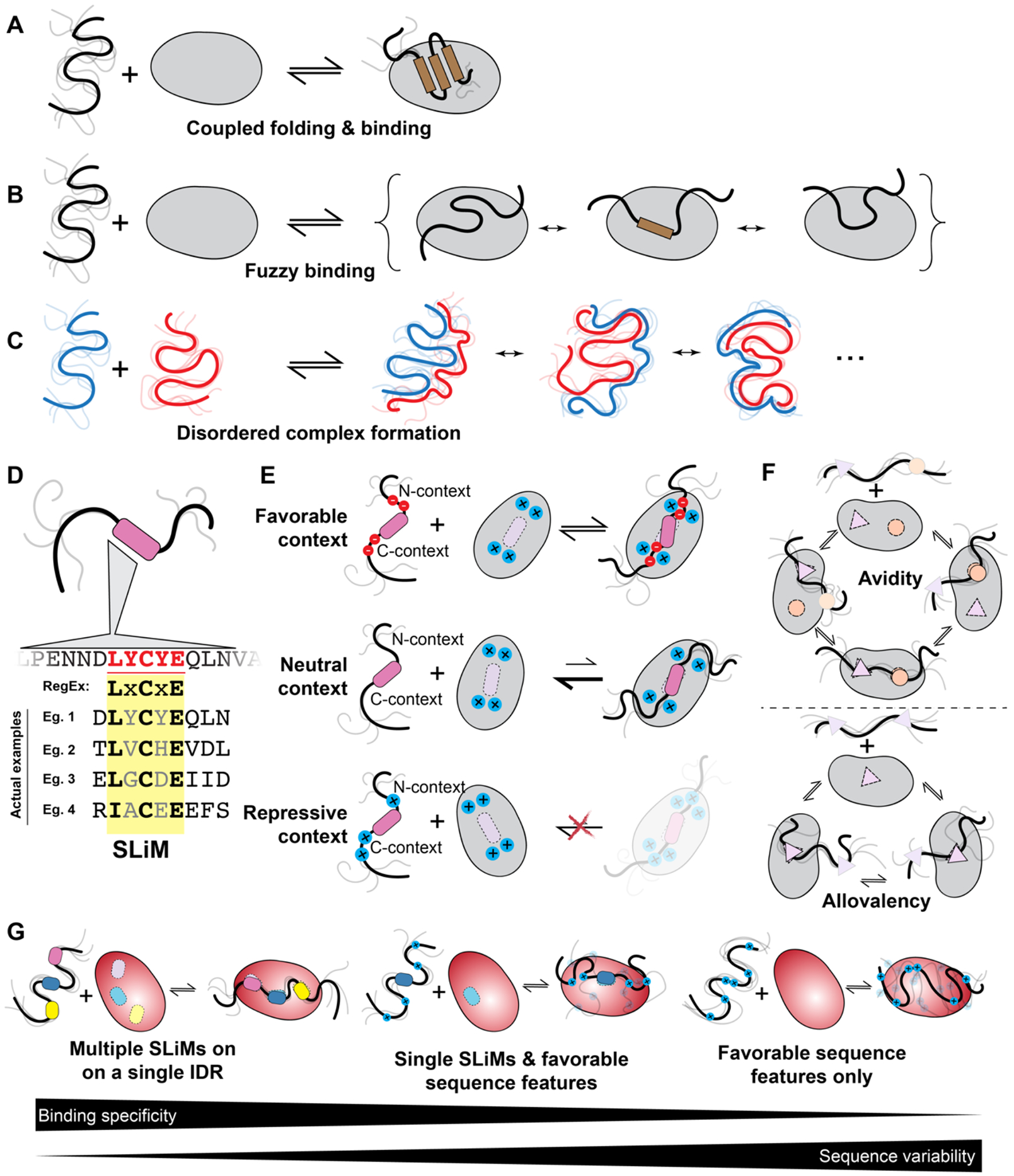

Figure 4: IDRs enable a range of molecular recognition modes.

(a) IDRs can bind partners via coupled folding and binding, where an IDR (or a subregion) folds upon interaction with its partner, be it DNA, RNA, protein, or a membrane. (b) IDRs can bind partners via fuzzy interactions, whereby multiple structurally distinct bound states are relevant to function. Illustrated here is a scenario where an IDR consistently interacts with the same interface in structurally distinct bound states. However, fuzzy interactions could also involve a scenario whereby an IDR possesses several non-overlapping motifs or binding residues that exchange in binding a single interface on the surface of a folded domain. (c) IDRs can bind disordered partners to form fully disordered complexes where no persistent structure or contacts are seen in either partner in the bound state. (d) IDR molecular recognition is often facilitated by Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs). These are often well-described as a consensus motif with evolutionary conserved and invariant positions, while other positions are partially or fully redundant. As a result, SLiMs can be described in terms of “regular expressions” (RegExs), a term borrowed from computer science that describes patterning matching when a subset of positions in a sequence are under some set of constraints (e.g., the PIP box binding to PCNA (QxxLxxFF), where X is any amino acid). (e) The sequence context around SLiMs is a critical determinant of binding. The same SLiM present in different proteins may bind with high affinity or not all, depending on the complementary chemical interactions between the residues flanking a SLiM and the surface surrounding the binding site. Thus, when the features of the flanking regions match those of the binding partner, the context is favourable (top), when no determining features are present, only the SLiM is deterministic for binding (middle) and when the features of the flanking regions and those of the binding partner surface do not match, the context is repressive (bottom). (f) Binding of IDRs often involves avidity and allovalency. Avidity emerges when multiple binding sites (e.g. SLiMs) enable two molecules to interact through two or more independent binding interfaces (top). Allovalency reflects the situation in which a single binding site on one partner is complemented by multiple identical binding interfaces on another (bottom). (g) IDRs can encode binding specificity in a variety of ways. Multiple SLiMs within a single IDR offer one route to high-specificity (and high affinity) binding, whereby only a limited set of partners possess binding interfaces common to all the SLiMs present, providing specificity combinatorily via many weak motifs (left). While conceptually this may be straightforward to understand, a growing body of work suggests the existence of a continuum of multivalent binding modes, whereby a combination of SLiMs and sequence features enable a trade off between sequence conservation and binding to a specific target (middle). Finally, IDRs may interact solely via chemical specificity, whereby specific sequence features lead to favourable interactions between the IDR and a partner, such as a positively-charged IDR binding to a negatively charged partner (right). The discriminatory power available for such a simple sequence feature may be limited, and other properties such as number of charges or charge density or properties yet to be discovered may enable specific molecular recognition

The molecular details surrounding coupled folding and binding are tuned to fit the needs of the cell. A well-described example is the N-terminal IDR from the master tumour suppressor p53, which undergoes coupled folding and binding, and for which residual helicity tunes affinity and specificity in inter-molecular interactions21,35,184,200,216,217. A more recent example shows evolutionary fine-tuning of helicity and that the correlation between the amount of residual helicity in the IDR and binding affinity for a folded domain is manifested in altered bound-state lifetime218. In some systems, like the pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins, the conformational landscape of coupled folding and binding is encoded by the IDR sequence219, as opposed to being templated by different folded partners220. In contrast, for the measles virus nucleoprotein, coupled folding and binding of the C-terminal IDR is driven by an induced folding pathway, whereby intermolecular contacts form before or in parallel with intramolecular folding102,221. As a final example, the nuclear co-activator domain NCBD from p300/CBP is a hub domain that is folded yet metastable. Upon binding one of its many partners – the disordered activation domain of the nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR – a transient electrostatically-steered complex forms, followed by an intramolecular folding reaction that stabilizes both proteins42. The formation of a stable bound-state complex from states where both partners are partially (NCBD) or fully (ACTR) disordered reflects the fact that NCBD can form distinct structured complexes with different disordered partners 217,222-225. In this way, a single partially folded domain can function as a multi-modal input receptor for cell signalling, transducing the identity and concentration of potential binding partners into distinct structural complexes.

Fuzzy Binding

In fuzzy binding, a number of structurally distinct states make up the bound complex (Fig. 4b)190,226,227. Fuzzy binding may involve static disorder, where each individual binding event yields a structurally distinct bound state that remains stable for its lifetime without exchanging to another state228. An extreme example of static disorder is the assembly of amyloid fibrils formed from disordered proteins229-231. While structurally-distinct fibres can and do form, interconversion between fibres of different structural states appears effectively impossible once formed. Alternatively, fuzzy binding may involve dynamic disorder, in which the bound state complex rearranges on timescales that are fast when compared to the timescales for dissociation. For dynamic disorder, fuzzy complexes could involve just a handful of structurally-distinct bound conformations that interconvert, or could reflect a scenario in which IDR conformational heterogeneity is similar in the bound and unbound states17,187,232. A classic example is the complex formed between the activation domain of the yeast transcription factor GCN4 and the co-activator Gal11 (refs. 233-236).

Fuzzy interactions are ubiquitous across IDR-mediated molecular recognition events. As one example, nuclear import and export rely on nuclear transport receptors, folded proteins that enable the passage of an appropriate cargo through the lumen of the nuclear pore complex237,238. The phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats from IDRs of nuclear pore proteins form fuzzy complexes with nuclear transport receptors239. This dynamic interaction is central to the ability of the nuclear pore to provide a chemical selectivity filter, a feature conserved across evolution240-242.

Transcription factor IDRs and their cognate co-activators can also form fuzzy complexes with some folding-upon-binding of local motifs7,187,233,243. Indeed, modulation of transcription factor interactions by competing binding partners or PTMs may enable fine-tuning of gene expression in a manner that allows different inputs to enhance or suppress transcriptional output, in effect acting as a network switch for signal integration 7,42,187,233,234,236,244. For example, the interaction between the folded TAZ1 domain of a transcription coactivator and IDRs from two transcription factors (HIF-1α and CITED2) provides a remarkable example of dynamic allosteric regulation enabled by a fuzzy complex188. When measured independently, HIF-1α binds TAZ1 and CITED2 with an equal affinity. Consequently, it might seem impossible for CITED2 to ever fully outcompete HIF-1α from binding to TAZ1. However, upon the interaction of CITED2 with the HIF-1α–TAZI complex, a transient ternary complex involving all three proteins is formed. Here, CITED2 takes over a shared binding site on TAZ1, leading to a conformational re-arrangement of TAZ1 and a subsequent reduction in affinity for HIF-1α. This complex allosteric mechanism highlights how IDRs can reshape folded domain ensembles to modulate molecular function.

Fully Disordered Complexes

The third mechanism of IDR-mediated recognition is one in which two IDRs bind one another and remain disordered in their bound state (Fig. 4c). For disordered bound-state ensembles, binding can be driven by distributed complementary chemical interactions that undergo fast timescale conformational re-arrangements, leading to a highly dynamic, heterogeneous bound-state ensemble245. These distributed chemical interactions can be driven by electrostatic interactions, aromatic interactions, or, in principle, any interaction mode whereby degenerate multivalency, i.e., the presence of many binding interfaces with approximately the same interaction strength, is encoded in an IDR.

The first rigorously characterized example of a fully disordered complex is the interaction between the negatively-charged histone chaperone prothymosin α and the positively-charged linker histone H1.0 (refs. 169,246-248). The interaction between such oppositely and highly charged proteins could be considered an extreme case of multivalency, with many short-lived and rapidly exchanging interactions between the individual charged groups. It could alternatively be considered as an average (mean field) electrostatic attraction that holds the two dynamically interconverting chains in very close proximity to one another with ultra-high affinity. Importantly, due to the electrostatic nature of this interaction, the measured affinity is exquisitely sensitive to salt, enabling binding affinities to be tuned by ionic strength in a rheostat-like manner. Dynamic, high-affinity interactions offer advantages to fast regulation of biology. Histone H1.0 also forms a high-affinity disordered complex with the nucleosome. The strength of this interaction should, in principle, impede nucleosome remodelling. However, enabled by the molecular dynamics found in H1.0 bound states, prothymosin α can dynamically outcompete the nucleosome, dislodging H1.0 by forming a transient H1.0–prothymosin α–nucleosome heterotrimer, followed by the release of H1.0, in a process of competitive substitution169,247. This ensures that nucleosomal remodelling can occur on timescales compatible with biological regulation. Similarly, disordered complexes have been observed for IDR-RNA interaction43,44. In the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, preprinted works shows that a short N-terminal IDR adjacent to the canonical, folded RNA binding domain enhances RNA binding ~50-fold, yet this IDR remains fully disordered in the bound complex44,174. Another example can be drawn from the nuclear pore complex. The interior of the nuclear pore provides a local chemical environment defined by tethered IDRs with FG repeats240,242,249. These disordered FG repeats interact with one another (homotypic interactions) via distributed phenylalanine residues, leading to a finely tuned chemical portal that enables efficient nucleo-cytoplasmic transport based on the surface-exposed chemistry of molecules in transit250. As a point of comparison, if those molecules in transit are folded domains (e.g., nuclear import receptors), they will interact with individual FG-rich IDRs as a fuzzy complex (as discussed above).

IDR-mediated Binding is Multifaceted

The separation of IDR-mediated binding modes into three subclasses might imply mechanistic stringency of interactions, making it possible to neatly categorize a given molecular complex. Yet, in reality, IDR-associated binding events can involve multiple modes. Fuzzy complexes often involve some degree of folding upon binding226. Folded domains are far from rigid, and IDR-associated binding may enhance or suppress molecular dynamics in folded domains251. We emphasize that this continuum of binding modes reflects the structural malleability associated with IDRs, and that it is generally worth considering all the types of interactions when understanding how an IDR may interact with a partner.

Molecular Specificity in IDR-mediated Interactions

Given the many different binding modes available, IDRs may appear poised to be promiscuous and adaptable. However, lack of specificity is not a general trait, and it may not be obvious if and how IDRs can encode specific molecular recognition. Specificity is defined in terms of both affinities and the availability of ligands252. The importance of affinity is obvious — if a protein/IDR binds many ligands with equal affinity, it would be considered promiscuous, such that binding one ligand with higher affinity than all others is typically how specificity is described. However, ligand availability is also key. A protein/IDR may — in principle — bind many different ligands, but if one is highly abundant, then it will behave with high specificity252,253. Thus, specificity is tunable by the cell. As a result, in a situation where affinities are low and/or many different binding-competent ligands are present, an IDR may appear promiscuous, despite that under a different scenario (a single binding-competent ligand), it may appear specific. While specificity can be encoded in canonical sequence-specific structured interfaces, emerging work suggests that specificity can also be obtained by combining several molecular interfaces on a single IDR.

SLiM-Mediated Specificity

One source of binding specificity is through SLiMs (Fig. 4d)138,186,254,255. SLiMs can bind to partner proteins in concert with the acquisition of secondary structure, as is seen for the PIP-Box motifs that bind PCNA, a trimeric DNA clamp that plays a central role in DNA replication192,256. SLiMs may also bind without taking on any specific structure, as is seen for the Disordered Ubiquitin-Binding Motif, a SLiM seen across many proteins257. Some folded binding partners can accommodate different SLiM-carrying IDRs that bind with different degrees (and kinds) of structure and disorder20,258. The converse is also true; the same SLiM can bind folded partners that differ substantially in tertiary structure, likely because of closely overlapping SLiMs259. As such, both simultaneously and competitively, one IDR can bind many folded domains, and a single folded domain can bind many IDRs, offering the opportunity for complex, context-dependent interactomes 260.

SLiMs enable specific molecular recognition, yet they often possess substantial redundancy. Redundancy here reflects the fact that for a SLiM binding to a specific partner, a subset of SLiM positions may be essential for binding, while other redundant positions can tolerate sequence changes (i.e., are partially or fully redundant) 138,261-263. This architecture means that SLiMs are frequently described in terms of so-called regular expressions, a computer science term used for pattern-matching that encompasses one or more unique sequences. For example, one such regular expression is “LxCxE”, where ‘x’ implies any residue is tolerated, whereas the leu (L), Cys (C), and Glu (E) are required138,255,264. This scenario is further complicated because this redundancy can depend on the binding partner. For example, for one partner, the appropriate regular expression might be LxCxE, while for another, it might be the more restrictive L[K|R]CxE – i.e., the second position must be positively charged. The potential for multiple constraints on SLiM variation depending on which binding partners are relevant can lead to complex patterns in sequence conservation and divergence 178,265.

Another source of complexity in SLiM-mediated binding is via overlapping SLiMs, a scenario in which several SLiMs partially overlap one another. Overlapping SLiMs enable competition-based regulation of intracellular communication (e.g., in signalling cascades). For example, the intracellular IDR from the transmembrane Growth Hormone Receptor (GHR) possesses overlapping SLiMs for two different kinases, such that direct competition between these kinases leads to distinct downstream signalling profiles depending on which kinase is bound266. Similarly, SLiMs in the N-terminal IDR of p53 bind several partners with different affinities and structures, leading to distinct downstream responses21,216,217,267-272. In short, overlapping SLiMs that define mutually exclusive binding interfaces provide a means to build biological exclusive “OR” (XOR) logic gates, where either one or another bound state can exist.

Specific mutations in SLiMs can have devastating phenotypic consequences273. Mutations in a degron SLiM embedded in the N-terminal IDR of β-catenin lead to unfettered proliferative growth in a variety of cancers274. Similarly, in cases with overlapping SLiMs, mutation can change the balance between interactors, rewiring downstream signalling138,260,275. While IDRs are often less susceptible to individual point mutations, SLiMs are an exception, where single mutations can abrogate or instigate function178,179,273,276.

The importance of understanding SLiM-mediated molecular recognition has catalyzed efforts to systematically measure SLiM binding using high-throughput methods260,277-279. Identified SLiMs are catalogued in a database of curated entries, which includes both specific instances and inferred regular expressions264. In essence, SLiMs can be thought of as short, flexible sequence-specific protein interfaces that enable molecular targeting for intracellular communication.

SLiM Context

Recent work has implicated the importance of the local sequence context into which a SLiM has evolved, or has evolved around a SLiM17,31,41,178,224,262,280,281. Rather than existing as independent binding modules, the N- and C-terminal regions flanking a SLiM can influence molecular recognition, either by ensuring a SLiM is fully accessible or by providing additional auxiliary interactions that contribute to productive binding encounters (Fig. 4e)41,224,280. A SLiM and its sequence context can cooperate synergistically to enhance the affinity and specificity of interactions of IDRs with their cellular targets. For example, a C-terminal lysine-rich region is required adjacent to the PxxPxK proline-rich motif for correct SH3 domain recognition in the HS1–HPK1 interaction282. Similarly, flanking regions and phosphorylation sites around the LxCxE motif of the human papillomavirus E7 protein tune binding affinity, controlling molecular interactions that impact cellular proliferation283. Finally, work on proteins that interact with PCNA revealed that most PCNA-binding motifs reside in IDRs, and that changes in flanking regions that increase the number of positive charges in the IDR tune affinity across four orders of magnitude192. These results implicate an emerging hierarchical model for specificity, where motifs and flanking regions cooperate to enable short-term fine-tuning via PTMs and long-term (evolutionary) fine-tuning via changes in the protein sequence.

The emerging importance of flanking regions in determining SLiM binding affinity and specificity reflects the conceptual challenge that regions around SLiMs are often poorly conserved, as assessed by linear sequence alignment. This apparent lack of conservation has given way to an appreciation that sequence features (discussed above) may be conserved despite divergence in primary structure (see Box 3) 6,55-57,59,92,178,244,284 When viewed through this lens, specificity can be dually encoded via two distinct types of interactions. If we accept that SLiMs enable sequence specificity (i.e., SLiMs cannot tolerate being shuffled; the action of randomly re-ordering the sequence without changing composition), then flanking regions essential for binding that lack bona fide SLiMs can be considered to possess sequence feature specificity (i.e., chemical specificity). Chemical specificity reflects local sequence chemistry that is complementary to a binding partner (Fig. 4e) 41,89,90,178,252. While conservation of SLiMs may require specific residues to be retained, conservation of sequence features can be achieved despite large-scale remodelling of the underlying amino acid sequence. Finally, flanking regions can overrule a SLiM by presenting incompatible features that prohibit binding. Thus, the presence of a sequence that — in principle — matches a known SLiM regular expression is not necessarily sufficient to define a bona fide SLiM (i.e., a motif that reliably binds its expected partner). For molecular communication, this hierarchical recognition that combines SLiMs with local sequence context enables specific, and in some cases high-affinity binding, with only a few conserved amino acids.

Balancing Affinity and Specificity

Although presenting a relatively limited binding interface, individual SLiMs can be highly specific. For example, TFIIS N-terminal domain (TND)-interacting motifs (TIMs) are SLiMs from transcription regulators that selectively recognize specific domains in the eukaryotic elongation machinery20. Although SLiMs can be high-affinity206,285, in many cases, the binding of individual SLiMs — especially if surrounded by sub-optimal flanking regions — can be relatively weak262. One way to enhance the binding affinity (and specificity) of an IDR is to embed multiple SLiMs that bind non-overlapping sites in a partner. If each SLiM binds a different recognition interface and only the appropriate partner possesses the full set of recognition interfaces, binding can be both high affinity (due to an avidity effect, Fig. 4f) and high specificity (due to the combinatorics) despite individually weak binding affinities associated with any single SLiM (Fig. 4g)38,110,286,287.

An alternative to carrying multiple SLiMs is for an IDR to possess a single SLiM with specific sequence features that interact via chemical specificity with a given partner or set of partners. This is similar to how SLiM context influences binding, but in this case sequence features may stretch far (10s-to-100s of residues) from the SLiM location, as opposed to simply defining a local permissive context. These sequence features may not offer the same degree of specificity that multiple SLiMs would. However, because these sequence features operate at the level of distributed chemical interactions instead of sequence-specific binding interfaces (as SLiMS can), they place a much lower burden on sequence conservation in the IDR or, indeed, sequence or structural conservation in the folded domain17,55,110,178,288. Moreover, an IDR with a single SLiM can interact specifically with many different partners that share only a single SLiM-binding interface, e.g., a PDZ-binding SLiM can bind many different proteins as long as each possesses a PDZ domain with surface chemistry complementary to the flanking sequence around the SLiM38,262,289. If intracellular communication lines depend on the fidelity of messages passed, the repertoire of molecular interfaces — from sequence-specific motifs to an appropriate net charge offer a broad toolkit for ensuring reception, transmission, and fine-tuning of those messages 18,120,146,152,154,160,162,290-292.

Combining multiple equivalent binding sites (i.e., SLiMs, repeats, or individual residues) in a single IDR can also enhance affinity through allovalency (Fig. 4f)189,275,293. Allovalency refers to a multiplicative increase in affinity brought about by a high copy number of independent binding sites that bind to the same site on a partner. For example, increasing the number of FG repeats in a nuclear pore IDR revealed that the low per-FG repeat affinity avoids high-avidity interaction between FG-nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) while the many FG repeats promote frequent FG-NTR contacts, resulting in enhanced selectivity294.

The dynamic ranges of affinities, timescales, and specificities available to IDRs are no different from those observed for folded domains203. Indeed, fully disordered complexes can form with picomolar affinity246, while individual SLiMs that fold upon binding may bind with high discriminatory power yet weak affinities262. Although there are numerous examples of IDRs that fold upon binding225,295, they likely only constitute a fraction of complexes involving IDR, allowing for a much broader view of how disorder contributes to molecular communication in cells. As biophysical/biochemical studies typically examine binding between small fragments from larger IDRs and cognate partners, it raises the question of how disorder-based interaction may manifest in full-length proteins. Moving towards studying proteins in context, we are only beginning to understand where and how disordered complexes contribute to function and cellular regulation. IDRs provide a broad toolkit of distinct mechanisms of molecular recognition that can enable complex, highly tunable interactions that underlie transcriptional networks, signalling pathways, and cellular organization.

IDRs and Biomolecular Condensates

Recently, the role of IDRs in biomolecular phase transitions has captured increasing attention (Fig. 5a, b). Assemblies formed via phase transitions are often called biomolecular condensates, a catch-all term defining membrane-less non-stochiometric assemblies that concentrate specific biomolecules and exclude others296. Condensates can range in diameter from a few nanometers (e.g., transcriptional condensates) to micrometers (e.g., membraneless organelles such as nucleoli or P-granules)19,297-299. Condensates can also possess different material properties, with some behaving like liquids and others like solids300. While all droplets formed by phase separation are condensates, not all condensates form via phase separation296. The physical principles underlying phase transitions in biology have been reviewed extensively elsewhere140,301-305, as has the form and function of biomolecular condensates296,300,306,307. As such, our focus here is on the roles IDRs can play in biomolecular condensates but not on the underlying physical principles.

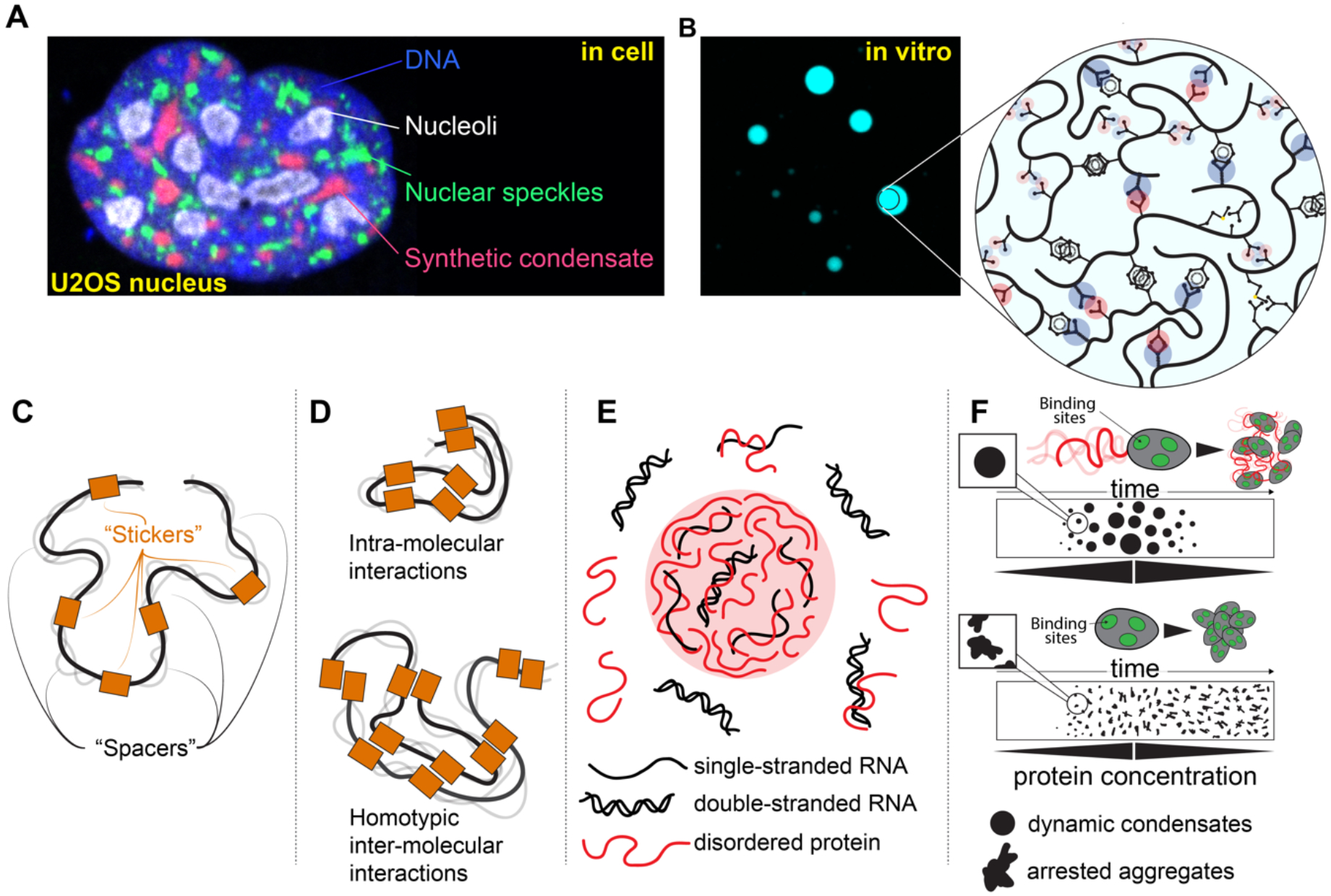

Figure 5: IDRs can undergo phase separation and contribute to biomolecular condensate formation.

(a) Biomolecular condensates are non-stoichiometric assemblies that concentrate specific biomolecules while excluding others. In cells, many condensates can co-exist, as shown here where nucleoli, nuclear speckles, and synthetic condensates generated using the PopTag oligomerization domain coexist in the same U2OS cell nucleus. (b) Condensates formed in vitro and in vivo through phase separation are often stabilized by IDRs, with a variety of distinct chemical interactions tuning condensate formation, maintenance, and material state. (c) IDRs that drive phase transitions can be described in terms of stickers and spacers, where stickers reflect regions or residues that have an outsized role in driving attractive interactions, while spacers are regions that connect stickers. (d) For IDRs that drive homotypic phase separation where many copies of the same IDR interact, favourable multivalent intra-molecular drive chain compaction, whereas favourable multivalent inter-molecular interactions drive phase separation. (e) If intra-condensate IDR concentrations are high, the high concentration of sidechain chemistries presented by the many IDR molecules effectively provides a novel solvent environment that can destabilize e.g., nucleic acid duplexes, but could also in principle catalyze chemical reactions. (f) The presence of IDRs adjacent to folded domains can prevent the formation of arrested condensates (irreversibly formed) through IDRs acting as local molecular ‘lubricants’. If the IDR engages in many weak interactions with the surface of the folded domain, those interactions can impede strong intermolecular interactions between folded domains that would otherwise lead to arrested condensates. In this way IDRs can act to ensure the condensates are dynamic and, upon a reduction in overall protein concentration, undergo disassembly. Here, folded domains are represented with discrete binding sites that mediate interactions with other folded domains. If folded domains lack IDRs, they readily assemble via interactions between folded domains, but those condensates become trapped irreversibly on the timescale of the schematic. In contrast, if folded domains possess IDRs, the IDRs lubricate folded domain interactions, leading to dynamic and reversible condensate formation. Image in part a is a courtesy of Steven Boeynaems, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Molecular Basis for Phase Transitions

In general, IDRs are neither necessary nor sufficient for phase transitions308. Nevertheless, there are many specific examples where IDRs are both necessary and sufficient and many more cases where IDRs modulate phase transitions. One reason why IDRs are often found to be associated with phase transitions is the same reason that IDRs enable dynamic, tunable molecular recognition: multivalency (Fig. 5b)39,57,309. Phase separation requires multivalent interactions that enable networks. IDRs provide a convenient platform upon which SLiMs and surrounding sequence features can cooperate to enable multivalency301,308.

One framework for describing multivalent IDRs is in terms of “stickers” and “spacers”, a framework originally developed for associative polymers 39,57,301,305,310-316. Stickers are defined as regions or residues that are the primary drivers of attractive multivalent interactions, while spacers connect stickers and influence overall solubility as well as sticker-sticker cooperativity (Fig. 5c). This is a deliberate simplification when applied to biomolecules in that “spacer” regions can and do contribute crucial attractive or repulsive interactions to tune biomolecular phase transitions112,163,313,317. Nonetheless, the stickers-and-spacers offers a convenient approach to capture the most important sequence-determinants of IDR-mediated phase transitions39,57,72,318-323. If multivalent IDRs are fully flexible and interact via homotypic interactions, there exists a symmetry between the degree of chain compaction (intra-molecular interaction) and the extent of phase separation (inter-molecular interaction) (Fig. 5d)57,123,324. While multivalency is not sufficient for phase separation (i.e., multivalent molecules can form system-spanning gels rather than locally dense droplets), it is certainly necessary39,311.

Roles of IDRs in Condensates