Abstract

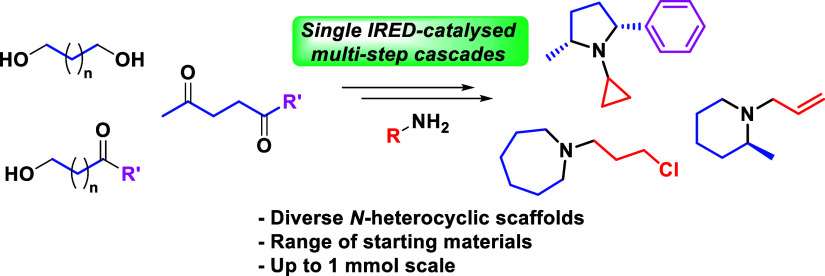

Saturated N-heterocycles constitute a vital scaffold for pharmaceutical chemistry but are challenging to access synthetically, particularly asymmetrically. Here, we demonstrate how imine reductases can achieve annulation through tandem inter- and intramolecular reductive amination processes. Imine reductases were used in combination with further enzymes to access unsubstituted, α-substituted, and α,α′-disubstituted N-heterocycles from simple starting materials in one pot and under benign conditions. This work shows the remarkable flexibility of these enzymes to have broad activity against numerous substrates derived from singlular starting materials.

Keywords: imine reductase, reductive aminase, cyclization, N-heterocycles

Introduction

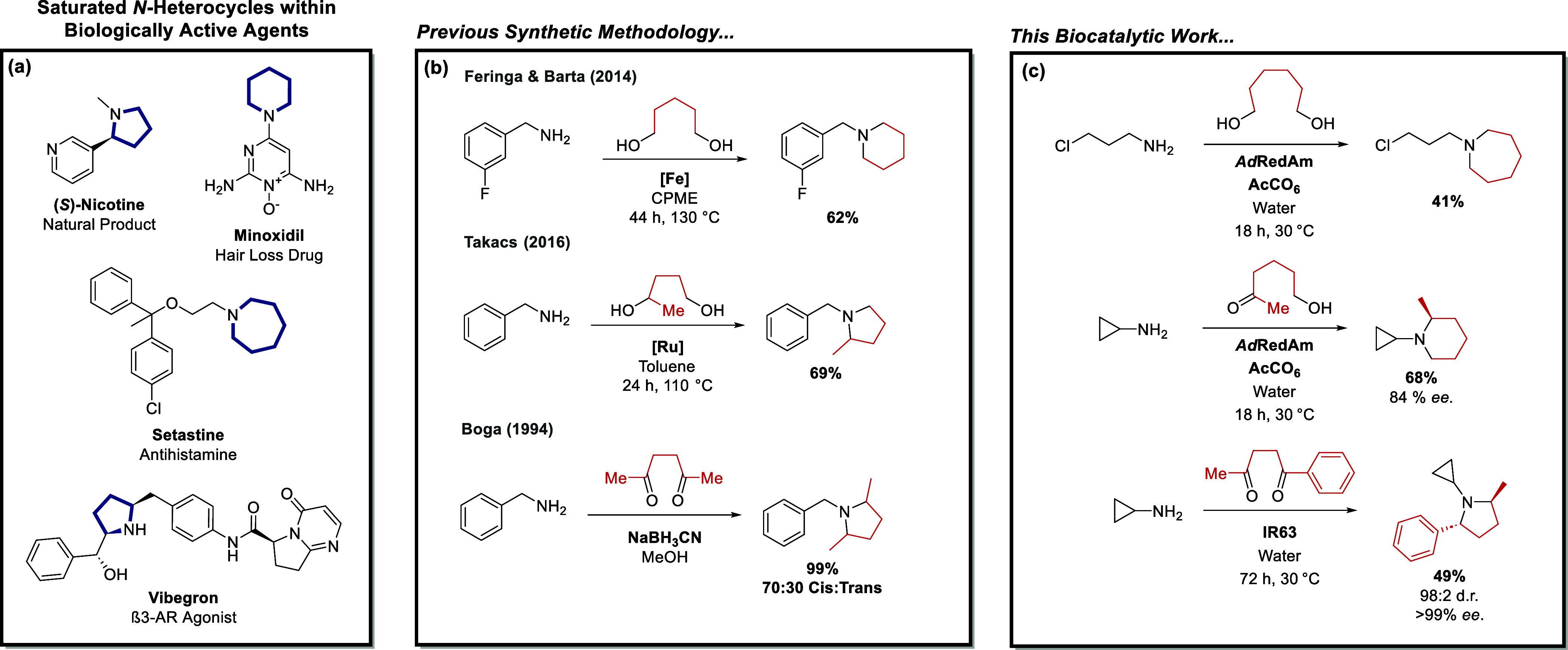

With half of all FDA-approved pharmaceuticals containing saturated N-heterocycles, improved methods for their synthesis are essential (Figure 1a).1 Current approaches, with limitations around stereochemical control through to sp3 C–H functionalization, limit access to diverse scaffolds. One specific challenge is N-alkylation, with methods such as reductive amination and nucleophilic substitution resulting in overalkylation and poor atom economy while depending on unsustainable reagents.2,3 Recently, borrowing hydrogen catalysis has seen application in the synthesis of saturated N-heterocycles through N-alkylation of amines with terminal diols; however, amine coupling partners have typically been limited to benzylamine and aniline derivatives.4−6 To access α-substituted N-heterocycles, diol substrates containing a secondary alcohol would permit retention or generation of a stereocenter. Although this has been demonstrated asymmetrically, the scope remains limited to few examples employing benzylamines, with reports proceeding with poor chemoselectivity.7,8 While intramolecular hydroamination offers an alternative route to these scaffolds, recent research has focused on C–H substitution at this position. Traditionally, this transformation has been performed using low-temperature lithiation chemistry,9 but modern methods have achieved it under preferable conditions by utilizing transition metal10−12 and photoredox catalysis (Figure 1b).13,14 Although synthesis of di-α-substituted heterocycles has been achieved through double reductive amination of diketone compounds,15 with key examples described in total and iminosugar syntheses,16,17 a general asymmetric catalytic platform is yet to be disclosed. Instead, strategies that prioritize redox-neutral cyclization chemistry (i.e., Paal-Knorr) followed by a global reduction are often preferred,18 despite the associated challenges in stereocontrol.

Figure 1.

Biologically active molecules containing saturated N-heterocycles (a) and a comparison between previous chemocatalytic and chemical annulation methodology (b) and the work outlined in this article (c).

Biocatalysis has emerged as a robust platform for synthesis.19 It possesses distinct advantages over traditional synthetic reagents, such as operation under benign conditions, catalyst complementarity, excellent stereoselectivity, and no requirements for protecting groups. This potential has been realized most in amine synthesis, with multiple pharmaceutical process methods described, including contributions from Merck,20 GSK,21 Pfizer,22,23 Novartis,24 and others.25 While enzymes such as amine oxidases (MAOs)26 and imine reductases (IREDs)27 provide options for setting stereocenters in preformed N-heterocycles, cyclization through N-alkylation by a single enzyme has been long unfeasible due to known options such as transaminases (TAs)28 and amine dehydrogenases (AmDHs)29 being limited solely to primary amination. In 2017, an imine reductase subclass (reductive aminases, RedAms) capable of catalyzing full aqueous reductive amination was reported.30 This synthetic potential has since been realized through industrial application in the synthesis of several drug candidates on a process scale.25

One-pot cascade reactions showcase the potential of biocatalysts for their synthesis. This has been exemplified in heterocycle synthesis, where TA-IRED combinations have generated saturated N-heterocycles from dicarbonyl substrates.31−33 Recent metagenomic IRED panels have also increased the number of applications of these enzymes in cascades.34,35 This includes setting stereocenters following cyclization,36−39N-alkylation with redox surrogate reagents through a hydrogen borrowing approach,40 and combination with alcohol oxidase or carboxylic acid reductase for N-alkylated products.41 Recent work also demonstrated the combination of chemoenzymatic approaches with amine oxidases,42 and the use of aldolases to synthesize aminopolyols.43 There has also been disclosure of multifunctional biocatalysts that simultaneously mediated several synthetic steps in one go.44 Herein, we further demonstrate this multifunctional ability of IREDs to form N-heterocycles through a sequential inter–intramolecular reductive amination ring closure approach in the first report of these specific types of transformations (Figure 1c). This approach showcases the multifunctionality of RedAms,44 with the biocatalyst operating on two individual substrates derived from the starting material in a one-pot cascade fashion.

Results and Discussion

Oxidation-IRED Cascades

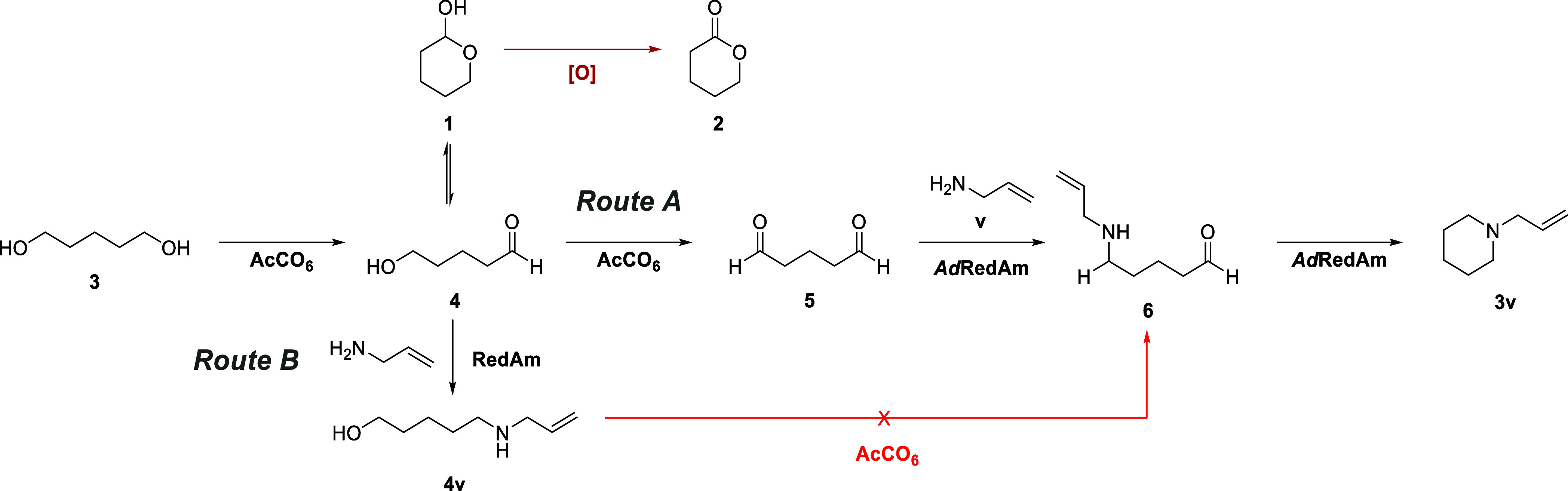

In a previous paper describing the engineering of AcCO6, we noted a general trend of high specific activity for terminal diol substrates.45 Inspired by this, we sought to compare our enzyme cascades to the chemical borrowing hydrogen literature, which inspired us to pursue a biocatalytic equivalent to the reported diol annulation chemistry. While alcohol oxidases have been previously applied to the oxidation of diols,46 access to the dialdehyde is often limited by overoxidation or the interception of intermediate hemiacetal tautomers to form lactones (Scheme 1).47

Scheme 1. Potential Biocatalytic Routes for AcCo6AdRedam Catalyzed Amine Diol Annulation.

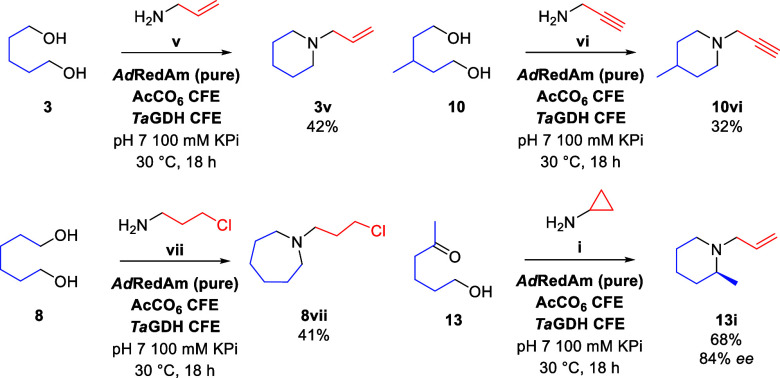

Initial analytical scale biotransformations analyzed by GC-MS showed no presence of carboxylic acids or δ-valerolactone 2 when 1,5-pentanediol 3 was subjected to oxidation by AcCO6, although glutaraldehyde 5 was also unobserved. We next sought to test the coupling of 3 with allylamine v under the standard AcCO6–RedAm cascade conditions outlined previously,41 with the better expressing “AdRedAm” used in lieu of “AspRedAm”. Unfortunately, we observed no product from this biotransformation. Hypothesizing that perhaps the intermediate hemiacetal intermediate tautomer 1 may be intercepted and oxidized by the glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) enzyme “CDX-901” required for cofactor recycling, we measured the specific activity of CDX-901 cell-free extract (CFE) with 5-hydroxypentanal 4 through an NADPH formation assay. The CDX-901 CFE was found to be active toward the oxidation of 4 and was replaced with the GDH fromThermoplasma acidophilum(TaGDH).48 The side activity was not confirmed as being due to CDX-901 itself or another enzyme present in the crude preparation. To our delight, when the biotransformation was repeated with TaGDH, we observed the formation of 1-allylpiperidine 3v. We speculate that 5 was not observed due to its known role as an enzyme cross-linking reagent and that without further reaction it may simply cross-link enzymes involved in its formation. This clearly demonstrated the versatility of this class of enzyme, mediating two distinct reductive amination reactions, first using a primary amine donor and then a secondary amine donor. The bifunctionality was of interest, leading us to probe the reaction pathway, given the number of potential reaction partners (Scheme 1). The potential intermediate N-allyl-5-hydroxypentan-1-amine 4v was synthesized and subjected alongside 4 to an oxidase activity screen as outlined previously.45 As 4 was shown to be a substrate for AcCO6 while 4v was not (shown in red), we concluded that “Route A” was the mechanism by which the heterocycle was formed. Following this, we sought to establish the product scope for this cascade reaction.

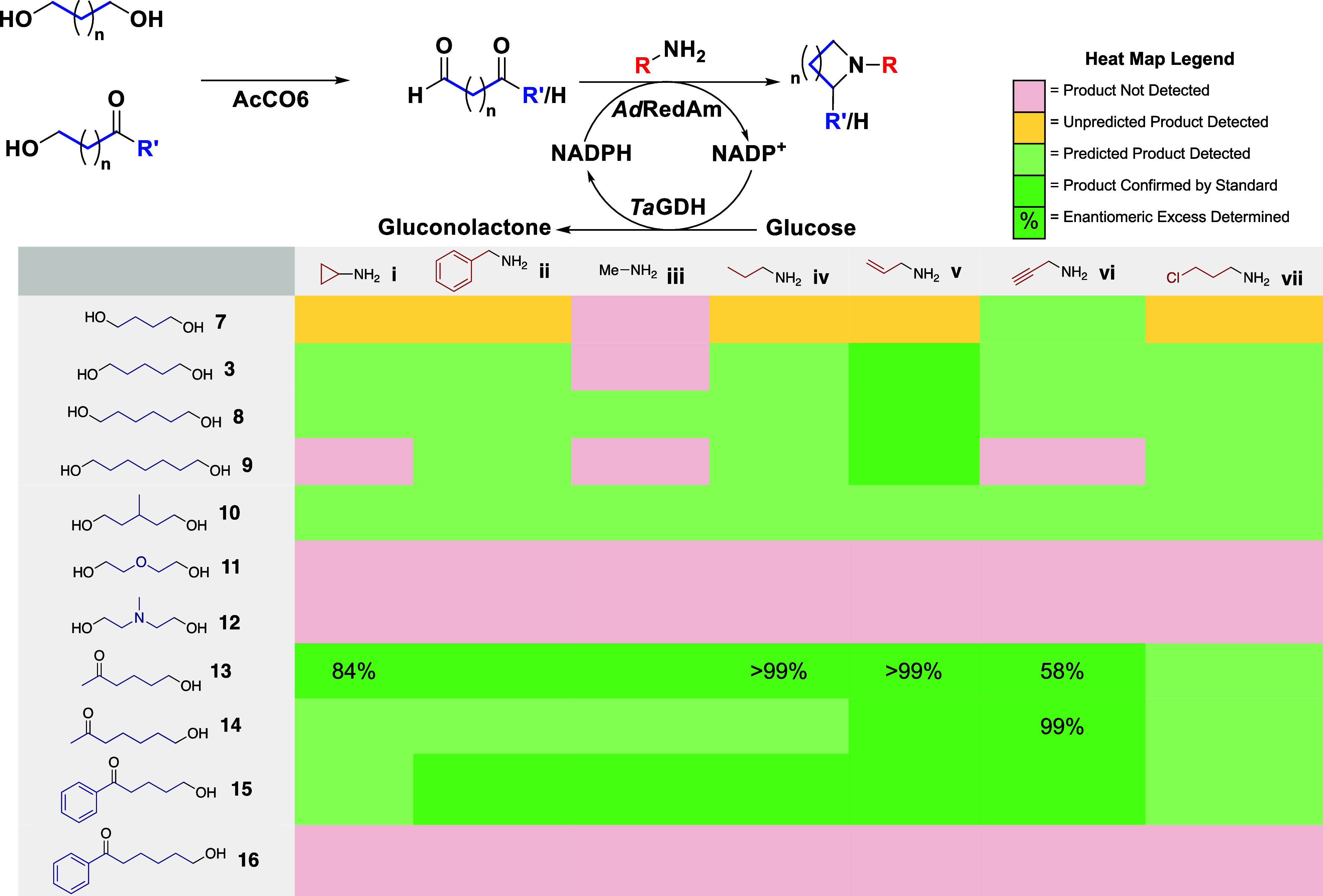

Initially, a panel of diol substrates was subjected to activity screening (see Supporting Information). Alongside previously tested aliphatic diols, diethylene glycol and N-methyl-diethanolamine were screened to investigate whether the methodology may be applied to form morpholines and piperazines. While diethylene glycol and N-methyl-diethanolamine were moderately active substrates for the engineered and wild-type choline oxidases, respectively, applying them under IRED- cascade conditions suggested no product formation by GC-MS analysis. Despite this, correct masses for heterocyclic products were successfully detected from the panel of aliphatic diols (Table 1). While the formation of saturated heterocycles was observed for 6–8 membered rings, 1,4-butanediol 7 largely yielded products of mass consistent with pyrroles, possibly through a Paal-Knorr reaction. Incubating 9 with a primary amine and lone AcCO6 did not yield a possible pyrrole product, indicating the involvement of the IRED in this transformation. Both N-methylpyrrolidine 7iii and N-methylpiperidine 3iii were undetected by GC-MS, but we speculate this is due to coretention with the solvent due to the low boiling point. While the majority of products were observed as single peaks in GC chromatograms, no reaction conversions are claimed due to the potential for undetectable side reactions such as enzyme cross-coupling. Our attention then turned to the synthesis of α-substituted N-heterocycles. 5-Oxohexanol 13 and 6-oxoheptanol 14 were synthesized and found to be substrates for AcCO6. Subjecting these substrates to conditions identical to those utilized in the terminal diol work yielded a range of asymmetric heterocycles (Table 1). Where possible, ee and absolute configuration were determined using chiral GC-FID, although these assignments are largely limited due to challenges in achieving the separation of nonderivitizable products and accessing enantiomerically pure standards. The use of aryl ketones 15 and 16 yielded enamine substrates, with AdRedAm unable to mediate the reduction of the more stable conjugated intermediate. Chemical reduction of these substrates still enabled a synthetic approach to 2-aryl substituted saturated N-heterocycles, but not in the same fashion as described above (see Supporting Information).

Table 1. Activity Heat Map for the AcCO6-AdRedAm Catalyzed Synthesis of N-Heterocyclesa.

Reaction conditions: 10 mM alcohol, 100 mM amine, 0.1 mM NADP+, 80 mM glucose, 1 mg mL–1AdRedAm, 1 mg mL–1 AcCO6, 0.5 mg mL –1TaGDH, 0.5 mg mL –1, 50 mg mL–1 6-HDNO whole cells*, 40 mM NH3BH3*, 2% (v/v) DMSO, 100 mM pH 7.0 KPi buffer, 500 μL reaction volume, 30 °C, 250 rpm, 18 h. *Substrates 15 and 16 only.

Following the establishment of the product scope, our attention moved to synthesis on a preparative scale. Through using a calibration curve, we were able to determine conditions that would yield piperidines and azepanes with high conversion, although we were not able to produce pyrroles or azocanes at conversions that were synthetically useful. Preparative scale reactions were performed on a 1 mmol scale with N-heterocycle products isolated by distillation (Scheme 2). Preparative scale synthesis was again performed on a 1 mmol scale on keto-alcohol precursor 13, with (S)-N-cyclopropyl-2-methylpiperidine 13i isolated in good yield and ee following distillation.

Scheme 2. Preparative Scale AcCO6-IRED Cascade Reactions.

10 mM diol, 100 mM amine, 200 μM NADP+, 80 mM glucose. See Supporting Information for full experimental details.

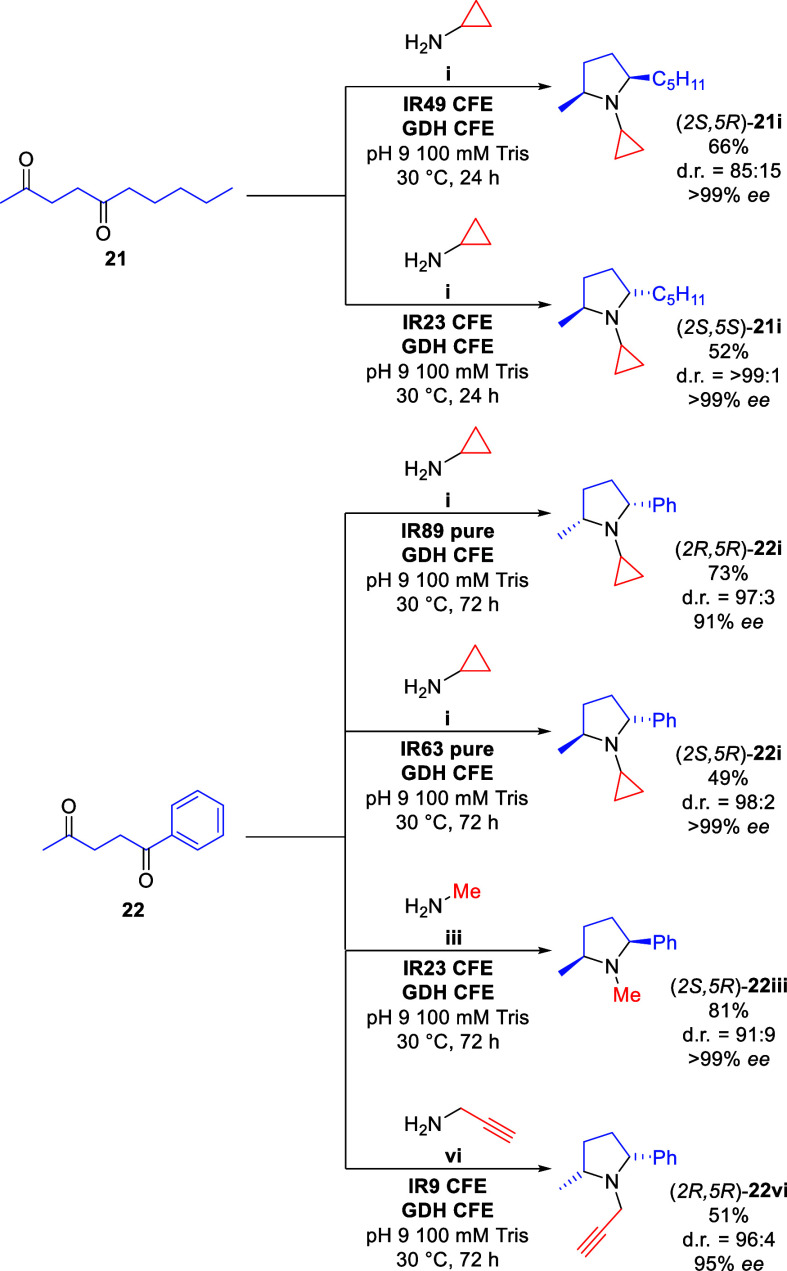

IRED-Mediated Diketone Cyclization

We next sought to extend the approach to disubstituted N-heterocycles, specifically the synthesis of N-alkylated 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines from 1,4-diketones via a three-step one-pot cascade catalyzed solely by an IRED. Initially, AdRedAm afforded N-methylpyrrolidine 21iii in good to high conversions (>80%) from 2,5-decadione and methylamine, with no pyrrole formation observed. However, low diastereomeric ratios were observed under all conditions tested. The reactions also did not prove amicable toward scaling, with byproducts consistently observed.

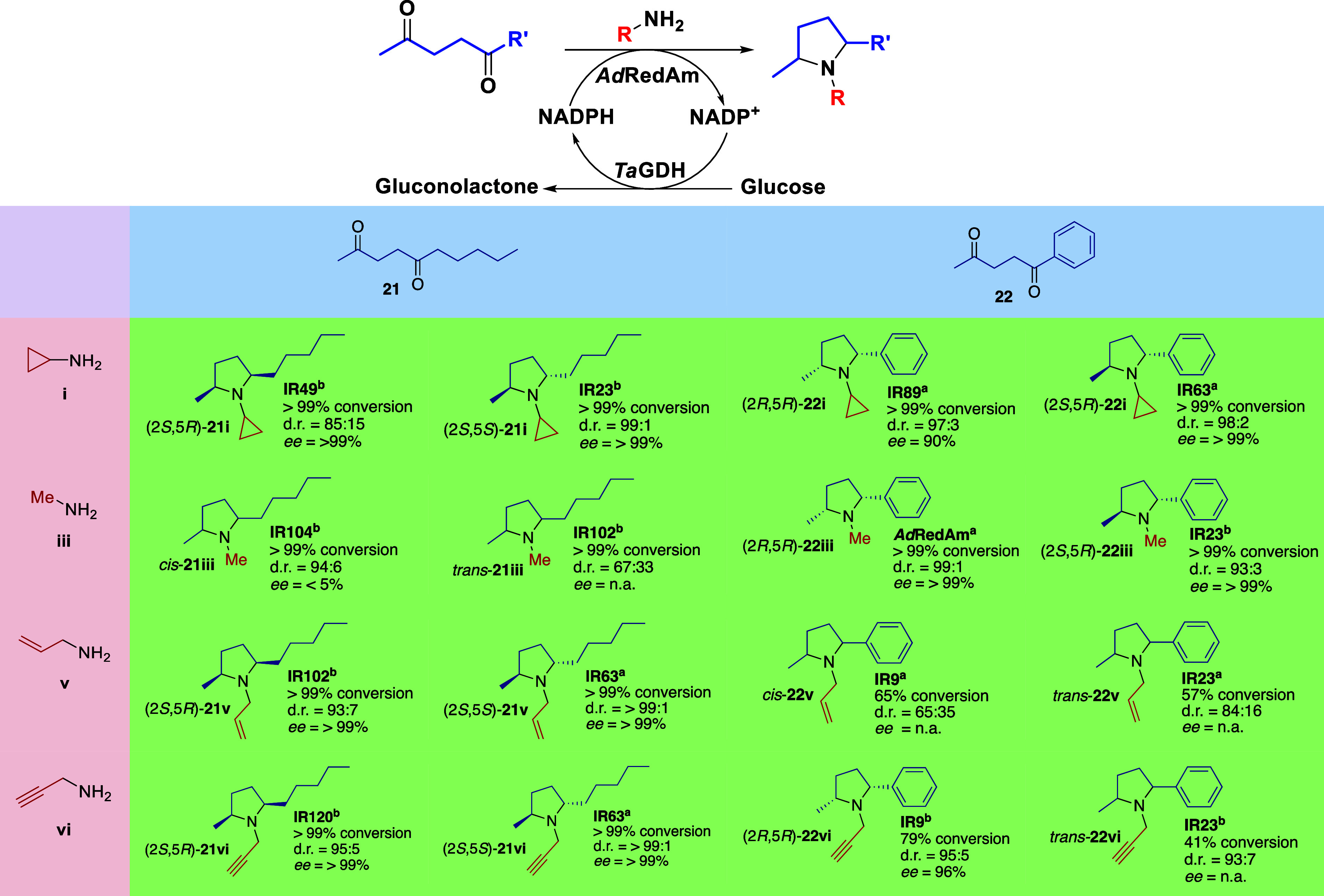

In an attempt to improve the stereochemical outcome, 30 IREDs were selected from a metagenomic panel and screened against two 1,4-diketone substrates (21 and 22) and four amine partners (i, iii, v, vi) (see Supporting Information for complete set of IREDs and screening results).35 As a result, we were pleased to obtain all eight N-alkylated 2,5-dissubstituted pyrrolidines from the combination of the two diketones and four amines evaluated, in good to high conversions within 24 h (Table 2).

Table 2. Product Scope of Diketone Annulationa.

Reaction conditions: 5 mM diketone, 100 mM amine, 0.5 mM NADP+, 50 mM glucose, 1 mg mL–1 purified IREDa or 5 mg mL–1 IRED lyophilized cell-free extract, 0.5 mg mL–1 GDH (CDX-901), 1% (v/v) DMSO, 100 mM Tris buffer pH 9.0, 500 μL reaction volume, 30 °C, 250 rpm, 24 h.

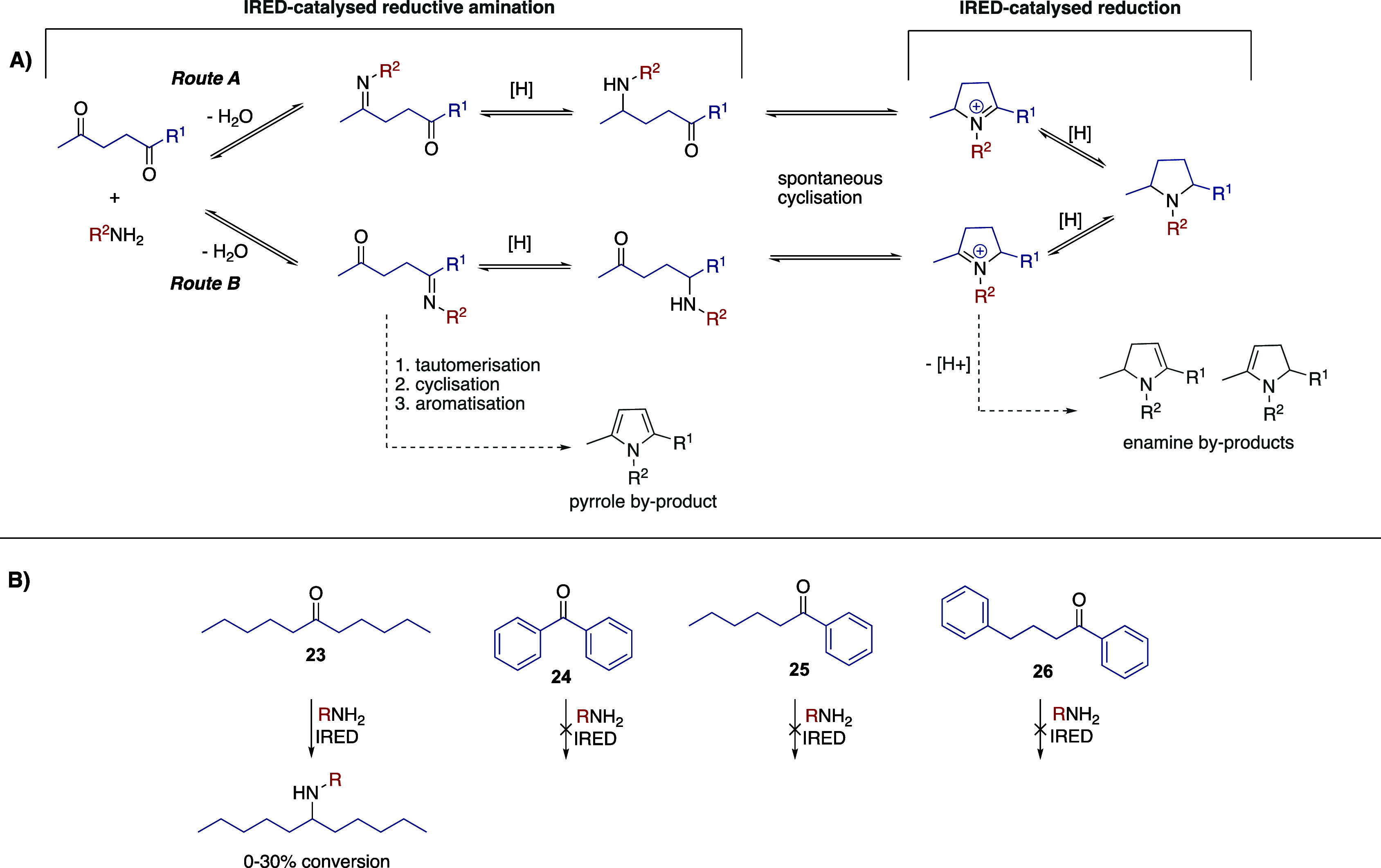

To our surprise, the proposed cascade also allowed us to access both cis and trans pyrrolidines in good to excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivities, dependent on the biocatalyst utilized. These results show that some IREDs retain absolute enantiopreference in both steps, affording trans products (e.g., 2S,5S-21i from IR23), while others switch selectivity to afford the cis products (e.g., 2S,5R-21i from IR49). These findings indicate that the substrate binding modes differ broadly among the evaluated IREDs and the acyclic–cyclic imine intermediates. Furthermore, access to both diastereoisomers suggests that the diastereoselectivity is primarily governed by the enzyme and not chemically dictated by the previously defined stereocenter.

Our proposed route assumed that the first reductive amination step occurs exclusively at the less hindered ketone moiety (Route A, Scheme 3a). To test this hypothesis, we evaluated four ketones (23–26,Scheme 3b) of analogous hindrances and electronic effects to the bulkier side of our diketones. None of the phenyl ketones (24–26) underwent reductive amination (see Supporting Information), implying that for diketone 22, the cascade occurs exclusively through Route A (Scheme 3a). Conversely, amine products were observed when using pentyl ketone 23 as the substrate, indicating that Route B could occur simultaneously with Route A for reactions using diketone 21. However, despite the presence of products, low conversions (10–30%) were obtained, which when combined with the fact that the selected IREDs showed high diastereo- and excellent enantioselectivies (Table 2), led us to conclude that Route A is the fastest, and most likely, the sole pathway followed in reactions using diketone 21.

Scheme 3. Investigating the Mechanism of IRED Catalyzed Diketone Annulation.

(A) Potential routes and byproducts thereof. (B) Bulky substrates evaluated.

Finally, to demonstrate the synthetic applicability of the investigated cascade, a series of preparative-scale syntheses were performed. Attempts to intensify reactions were unsuccessful, and consequently, the same conditions used on the analytical scale were applied for the preparative-scale reactions. Using our three-step one-enzyme cascade, six N-alkylated 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines were successfully synthesized on a 0.3 mmol scale (Scheme 4). Both diastereoisomers of pyrrolidines 21i were synthesized with excellent enantioselectivities and good yields within 24 h, but 72 h was required for most other substrates. Typically, full substrate consumption was observed after 24 h and the enamine intermediate/byproduct was observed along with the desired product, followed solely by production of the desired product in the following 24–48 h.

Scheme 4. Preparative Scale Biocatalytic Diketone Annulation.

6 mM diketone, 100 mM amine, 250 μM NADP+, 100 mM glucose. See Supporting Information for full experimental details.

Conclusions

The work presented here has demonstrated the bifunctionality of a series of wild-type IREDs, able to catalyze multiple reductive aminations in a cascade sequence derived from the same starting materials. We have expanded the biocatalytic reaction toolbox through the demonstration of IRED-catalyzed annulation reactions and have demonstrated how enzyme engineering may influence catalysis with the first alcohol oxidase capable of generating dialdehydes with complete chemoselectivity. Through applying these enzymes in combination, four distinct synthetic steps were achieved within one pot, and transformations previously unique to precious metal-catalyzed borrowing hydrogen chemistry requiring forcing conditions are achieved at 30 °C in water with an expanded amine scope. The ability to form α-substituted heterocycles is a transformation underrepresented in heterogeneous catalysis, and here we demonstrate it with stereocontrol. Finally, by extending this work to the synthesis of N-alkylated α,α-disubstituted pyrrolidines from simple diketone starting materials, we have demonstrated a remarkable ability of these biocatalysts to build complexity with complete diastereomeric control. While there are limits to the synthetic application of our methodology, the recent expansion of our imine reductase panel demonstrated in the diketone cascade and the potential for the engineering of these enzymes toward this chemistry presents enormous potential. With the unprecedented speed with which IREDs have moved from discovery to industrial application, we are hopeful that this novel methodology may achieve a similar impact.

Acknowledgments

N.J.T. and B.Z.C. acknowledge the ERC for an Advanced Grant (BIO-BORROW, grant number 742897). We would also like to acknowledge an EPSRC CASE award for J.I.R.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- RedAm

reductive aminase

- IRED

imine reductase

- GDH

glucose dehydrogenase

- AcCO6

alcohol oxidase

- 6-HDNO

6-hydroxy-D-nicotine oxidase

- TA

transaminase

- CAR

carboxylic acid reductase

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.4c03832.

Materials, experimental procedures, analytic methods, GC traces and spectra, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.I.R. and B.Z.C. contributed equally to this work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was financially supported by an ERC Advanced Grant (Grant Number 742987).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vitaku E.; Smith D. T.; Njardarson J. T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (24), 10257–10274. 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irrgang T.; Kempe R. 3d-Metal Catalyzed N- and C-Alkylation Reactions via Borrowing Hydrogen or Hydrogen Autotransfer. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (4), 2524–2549. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero-Antonino J. R.; Adam R.; Beller M. Catalytic Reductive N-Alkylations Using CO2 and Carboxylic Acid Derivatives: Recent Progress and Developments. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (37), 12820–12838. 10.1002/anie.201810121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid M. H. S. A.; Allen C. L.; Lamb G. W.; Maxwell A. C.; Maytum H. C.; Watson A. J. A.; Williams J. M. J. Ruthenium-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of Amines and Sulfonamides Using Borrowing Hydrogen Methodology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (5), 1766–1774. 10.1021/ja807323a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T.; Feringa B. L.; Barta K. Iron Catalysed Direct Alkylation of Amines with Alcohols. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5 (1), 5602. 10.1038/ncomms6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Zhang C.; Gao W.-C.; Ma Y.; Wang X.; Zhang L.; Yue J.; Tang B. Nickel-Catalyzed Borrowing Hydrogen Annulations: Access to Diversified N-Heterocycles. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (54), 7844–7847. 10.1039/C9CC03975A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marichev K. O.; Takacs J. M. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Amination of Secondary Alcohols Using Borrowing Hydrogen Methodology. ACS Catal. 2016, 6 (4), 2205–2210. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K.; Fujii T.; Yamaguchi R. Cp*Ir Complex-Catalyzed N-Heterocyclization of Primary Amines with Diols: A New Catalytic System for Environmentally Benign Synthesis of Cyclic Amines. Org. Lett. 2004, 6 (20), 3525–3528. 10.1021/ol048619j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beak P.; Lee W. K. Alpha.-Lithioamine Synthetic Equivalents: Syntheses of Diastereoisomers from the Boc-Piperidines. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55 (9), 2578–2580. 10.1021/jo00296a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos K. R.; Klapars A.; Waldman J. H.; Dormer P. G.; Chen C. Enantioselective, Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of N-Boc-Pyrrolidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (11), 3538–3539. 10.1021/ja0605265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschiulli A.; Smout V.; Storr T. E.; Mitchell E. A.; Eliáš Z.; Herrebout W.; Berthelot D.; Meerpoel L.; Maes B. U. W. Ruthenium-Catalyzed α-(Hetero)Arylation of Saturated Cyclic Amines: Reaction Scope and Mechanism. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, 19 (31), 10378–10387. 10.1002/chem.201204438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Ma L.; Paul A.; Seidel D. Direct α-C-H Bond Functionalization of Unprotected Cyclic Amines. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10 (2), 165–169. 10.1038/nchem.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally A.; Prier C. K.; MacMillan D. W. C. Discovery of an α-Amino C–H Arylation Reaction Using the Strategy of Accelerated Serendipity. Science 2011, 334 (6059), 1114–1117. 10.1126/science.1213920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. H.; Shurtleff V. W.; Terrett J. A.; Cuthbertson J. D.; MacMillan D. W. C. Native Functionality in Triple Catalytic Cross-Coupling: Sp3 C–H Bonds as Latent Nucleophiles. Science 2016, 352 (6291), 1304–1308. 10.1126/science.aaf6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boga C.; Manescalchi F.; Savoia D. Diastereoselective Synthesis of 2,5-Dimethylpyrrolidines and 2,6-Dimethylpiperidines by Reductive Amination of 2,5-Hexanedione and 2,6-Heptanedione with Hydride Reagents. Tetrahedron 1994, 50 (16), 4709–4722. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter E. W.; Reitz A. B. Expeditious Synthesis of Aza Sugars by the Double Reductive Amination of Dicarbonyl Sugars. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59 (11), 3175–3185. 10.1021/jo00090a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laventine D. M.; Davies M.; Evinson E. L.; Jenkins P. R.; Cullis P. M.; García M. D. Stereoselective Synthesis by Double Reductive Amination Ring Closure of Novel Aza-Heteroannulated Sugars. Tetrahedron 2009, 65 (24), 4766–4774. 10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano R.; Kashiwabara M.; Ohsumi M.; Kusano H. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 2,3,5-Trisubstituted Pyrroles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (3), 808–809. 10.1021/ja7102422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. L.; Finnigan W.; France S. P.; Green A. P.; Hayes M. A.; Hepworth L. J.; Lovelock S. L.; Niikura H.; Osuna S.; Romero E.; Ryan K. S.; Turner N. J.; Flitsch S. L. Biocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2021, 1 (1), 46. 10.1038/s43586-021-00044-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savile C. K.; Janey J. M.; Mundorff E. C.; Moore J. C.; Tam S.; Jarvis W. R.; Colbeck J. C.; Krebber A.; Fleitz F. J.; Brands J.; Devine P. N.; Huisman G. W.; Hughes G. J. Biocatalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Chiral Amines from Ketones Applied to Sitagliptin Manufacture. Science 2010, 329 (5989), 305–309. 10.1126/science.1188934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober M.; MacDermaid C.; Ollis A. A.; Chang S.; Khan D.; Hosford J.; Latham J.; Ihnken L. A. F.; Brown M. J. B.; Fuerst D.; Sanganee M. J.; Roiban G. D. Chiral Synthesis of LSD1 Inhibitor GSK2879552 Enabled by Directed Evolution of an Imine Reductase. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2 (10), 909–915. 10.1038/s41929-019-0341-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R.; Karmilowicz M. J.; Burke D.; Burns M. P.; Clark L. A.; Connor C. G.; Cordi E.; Do N. M.; Doyle K. M.; Hoagland S.; Lewis C. A.; Mangan D.; Martinez C. A.; McInturff E. L.; Meldrum K.; Pearson R.; Steflik J.; Rane A.; Weaver J. Biocatalytic Reductive Amination from Discovery to Commercial Manufacturing Applied to Abrocitinib JAK1 Inhibitor. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4 (9), 775–782. 10.1038/s41929-021-00671-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steflik J.; Gilio A.; Burns M.; Grogan G.; Kumar R.; Lewis R.; Martinez C. Engineering of a Reductive Aminase to Enable the Synthesis of a Key Intermediate to a CDK 2/4/6 Inhibitor. ACS Catal. 2023, 13 (15), 10065–10075. 10.1021/acscatal.3c01534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E. J.; Siirola E.; Moore C.; Kummer A.; Stoeckli M.; Faller M.; Bouquet C.; Eggimann F.; Ligibel M.; Huynh D.; Cutler G.; Siegrist L.; Lewis R. A.; Acker A.-C.; Freund E.; Koch E.; Vogel M.; Schlingensiepen H.; Oakeley E. J.; Snajdrova R. Machine-Directed Evolution of an Imine Reductase for Activity and Stereoselectivity. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (20), 12433–12445. 10.1021/acscatal.1c02786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- France S. P.; Lewis R. D.; Martinez C. A. The Evolving Nature of Biocatalysis in Pharmaceutical Research and Development. JACS Au 2023, 3 (3), 715–735. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista V. F.; Galman J. L.; Pinto D. C.; Silva A. M. S.; Turner N. J. Monoamine Oxidase: Tunable Activity for Amine Resolution and Functionalization. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (12), 11889–11907. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangas-Sanchez J.; France S. P.; Montgomery S. L.; Aleku G. A.; Man H.; Sharma M.; Ramsden J. I.; Grogan G.; Turner N. J. Imine Reductases (IREDs). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 37, 19–25. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slabu I.; Galman J. L.; Lloyd R. C.; Turner N. J. Discovery, Engineering, and Synthetic Application of Transaminase Biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (12), 8263–8284. 10.1021/acscatal.7b02686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus T.; Böhmer W.; Mutti F. G. Amine Dehydrogenases: Efficient Biocatalysts for the Reductive Amination of Carbonyl Compounds. Green Chem. 2017, 19 (2), 453–463. 10.1039/C6GC01987K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleku G. A.; France S. P.; Man H.; Mangas-Sanchez J.; Montgomery S. L.; Sharma M.; Leipold F.; Hussain S.; Grogan G.; Turner N. J. A Reductive Aminase from Aspergillus Oryzae. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9 (10), 961–969. 10.1038/nchem.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France S. P.; Hussain S.; Hill A. M.; Hepworth L. J.; Howard R. M.; Mulholland K. R.; Flitsch S. L.; Turner N. J. One-Pot Cascade Synthesis of Mono- and Disubstituted Piperidines and Pyrrolidines Using Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CAR), ω-Transaminase (ω-TA), and Imine Reductase (IRED) Biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2016, 6 (6), 3753–3759. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa B. Z.; Galman J. L.; Slabu I.; France S. P.; Marsaioli A. J.; Turner N. J. Synthesis of 2,5-Disubstituted Pyrrolidine Alkaloids via A One-Pot Cascade Using Transaminase and Reductive Aminase Biocatalysts. ChemCatChem. 2018, 10 (20), 4733–4738. 10.1002/cctc.201801166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarenga N.; Payer S. E.; Petermeier P.; Kohlfuerst C.; Meleiro Porto A. L.; Schrittwieser J. H.; Kroutil W. Asymmetric Synthesis of Dihydropinidine Enabled by Concurrent Multienzyme Catalysis and a Biocatalytic Alternative to Krapcho Dealkoxycarbonylation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (2), 1607–1620. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roiban G. D.; Kern M.; Liu Z.; Hyslop J.; Tey P. L.; Levine M. S.; Jordan L. S.; Brown K. K.; Hadi T.; Ihnken L. A. F.; Brown M. J. B. Efficient Biocatalytic Reductive Aminations by Extending the Imine Reductase Toolbox. ChemCatChem. 2017, 9 (24), 4475–4479. 10.1002/cctc.201701379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. R.; Yao P.; Montgomery S. L.; Finnigan J. D.; Thorpe T. W.; Palmer R. B.; Mangas-Sanchez J.; Duncan R. A. M.; Heath R. S.; Graham K. M.; Cook D. J.; Charnock S. J.; Turner N. J. Screening and Characterization of a Diverse Panel of Metagenomic Imine Reductases for Biocatalytic Reductive Amination. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13 (2), 140–148. 10.1038/s41557-020-00606-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlinghaus N.; Gergel S.; Nestl B. M. Biocatalytic Access to Piperazines from Diamines and Dicarbonyls. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (4), 3727–3732. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe T. W.; France S. P.; Hussain S.; Marshall J. R.; Zawodny W.; Mangas-Sanchez J.; Montgomery S. L.; Howard R. M.; Daniels D. S. B.; Kumar R.; Parmeggiani F.; Turner N. J. One-Pot Biocatalytic Cascade Reduction of Cyclic Enimines for the Preparation of Diastereomerically Enriched N-Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (49), 19208–19213. 10.1021/jacs.9b10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawodny W.; Montgomery S. L.; Marshall J. R.; Finnigan J. D.; Turner N. J.; Clayden J. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Substituted Azepanes by Sequential Biocatalytic Reduction and Organolithium-Mediated Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (51), 17872–17877. 10.1021/jacs.8b11891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus T.; Corrado M. L.; Mutti F. G. One-Pot Biocatalytic Synthesis of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Amines with Two Stereocenters from α,β-Unsaturated Ketones Using Alkyl-Ammonium Formate. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (23), 14459–14475. 10.1021/acscatal.2c03052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S. L.; Mangas-Sanchez J.; Thompson M. P.; Aleku G. A.; Dominguez B.; Turner N. J. Direct Alkylation of Amines with Primary and Secondary Alcohols through Biocatalytic Hydrogen Borrowing. Angew. Chem. - Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (35), 10491–10494. 10.1002/anie.201705848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden J. I.; Heath R. S.; Derrington S. R.; Montgomery S. L.; Mangas-Sanchez J.; Mulholland K. R.; Turner N. J. Biocatalytic N-Alkylation of Amines Using Either Primary Alcohols or Carboxylic Acids via Reductive Aminase Cascades. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (3), 1201–1206. 10.1021/jacs.8b11561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa V.; Thorpe T. W.; Marshall J. R.; Sangster J. J.; Gilio A. K.; Pirvu L.; Heath R. S.; Angelastro A.; Finnigan J. D.; Charnock S. J.; Nafie J. W.; Grogan G.; Whitehead R. C.; Turner N. J. Synthesis of Stereoenriched Piperidines via Chemo-Enzymatic Dearomatization of Activated Pyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (46), 21088–21095. 10.1021/jacs.2c07143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford G. J.; Swanson C. R.; Bradshaw Allen R. T.; Marshall J. R.; Mattey A. P.; Turner N. J.; Clapés P.; Flitsch S. L. Three-Component Stereoselective Enzymatic Synthesis of Amino-Diols and Amino-Polyols. JACS Au 2022, 2 (10), 2251–2258. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe T. W.; Marshall J. R.; Harawa V.; Ruscoe R. E.; Cuetos A.; Finnigan J. D.; Angelastro A.; Heath R. S.; Parmeggiani F.; Charnock S. J.; Howard R. M.; Kumar R.; Daniels D. S. B.; Grogan G.; Turner N. J. Multifunctional Biocatalyst for Conjugate Reduction and Reductive Amination. Nature 2022, 604 (7904), 86–91. 10.1038/s41586-022-04458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. S.; Birmingham W. R.; Thompson M. P.; Taglieber A.; Daviet L.; Turner N. J. An Engineered Alcohol Oxidase for the Oxidation of Primary Alcohols. ChemBioChem. 2019, 20 (2), 276–281. 10.1002/cbic.201800556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahart A. J. C.; Staniland J.; Miller G. J.; Cosgrove S. C. Oxidase Enzymes as Sustainable Oxidation Catalysts. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9 (1), 211572 10.1098/rsos.211572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C.; Trajkovic M.; Fraaije M. W. Production of Hydroxy Acids: Selective Double Oxidation of Diols by Flavoprotein Alcohol Oxidase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (12), 4869–4872. 10.1002/anie.201914877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright J. R.; Byrom D.; Danson M. J.; Hough D. W.; Towner P. Cloning, Sequencing and Expression of the Gene Encoding Glucose Dehydrogenase from the Thermophilic Archaeon Thermoplasma Acidophilum. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 211 (3), 549–554. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.