Abstract

Soft tissue masses are very common and may appear in the context of rheumatic diseases. They usually occur alone but may occasionally be part of the syndromes and can sometimes involve periarticular tissues. Soft tissue masses can be divided into several categories. In this article, we have categorized them into 3 different groups: (1) pseudotumors, (2) benign tumors, and (3) malignant tumors. Parotid enlargement will also be discussed in this study. The majority of Soft tissue masses are pseudotumors or benign tumors, which can be easily characterized with ultrasound, therefore, considered the first screening tool in the study of this type of lesion. If the tumor is deep or poorly accessible, or present with suspected signs of malignancy, the sonographer may suggest expanding the study with magnetic resonance imaging and/or an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the lesion. Ultrasound is also a good technique for the parotid and submandibular glands and is very useful for evaluating and monitoring Sjogren’s syndrome.

Keywords: Ultrasound, soft tissue masses, parotid gland, sjögren disease

Introduction

Pseudotumors

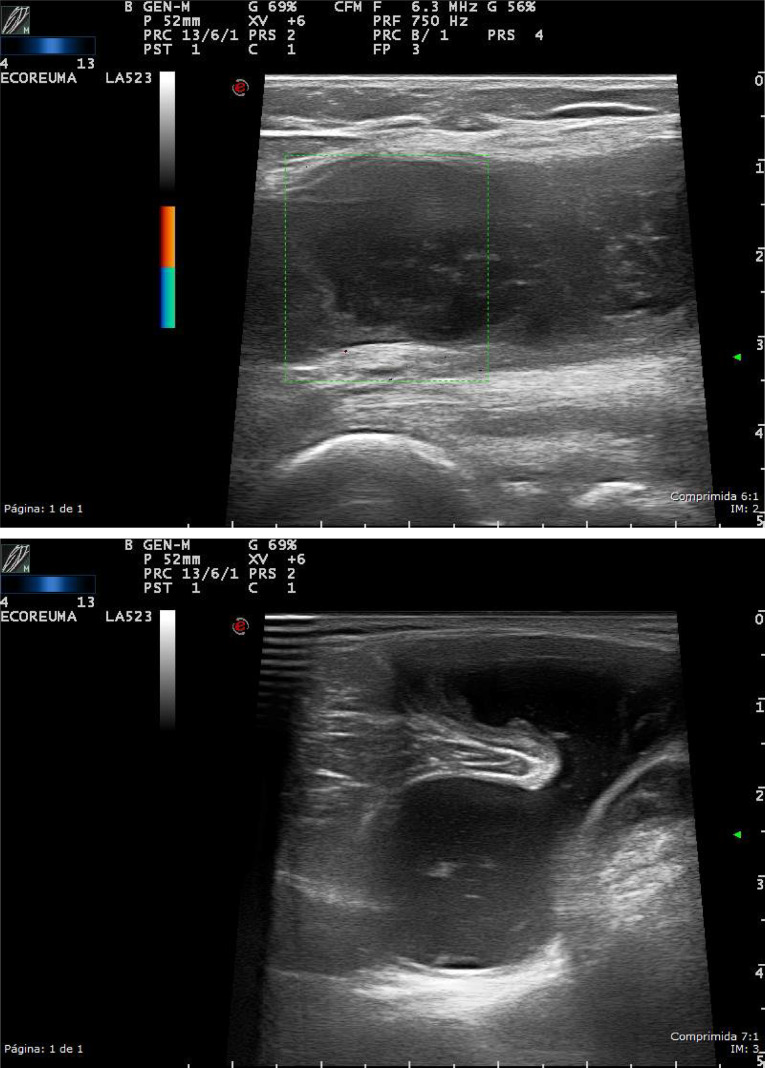

Synovial cyst is a continuation or herniation of the synovial membrane through the joint capsule. The most characteristic one is Baker’s cyst. They are associated with joint diseases such as osteoarthrosis, inflammatory, and post-traumatic joint diseases.1 In ultrasound (US), it appears as nodular anechoic lesions with well-defined edges with the typical extension toward the joint (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

High-resolution ultrasound of the knee, in grayscale (longitudinal and transversal) from a patient with popliteal synovial cyst. Nodular anechoic lesions with well-defined edges, with a fluid-containing neck between the tendon of semimembranosus and medial head of gastrocnemius.

Ganglion cyst is formed by dense connective tissue filled with gelatinous fluid rich in hyaluronic acid and other mucopolysaccharides. Ultrasound may show an ovoid single or poly-lobulated anechoic, well-defined lesion, with no obvious communication with the adjacent joint.

Sonographic compression can be helpful to differentiate a synovial cyst, normally more easily compressible, from a ganglion cyst. Synovial cysts related to active disease might show synovial hypertrophy changing its compressibility, for instance, in a case of a Baker cyst with synovial hypertrophy in rheumatoid arthritis2 (Table 1) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Ganglion Cyst Versus Synovial Cyst. Ultrasound Characteristics Through a Review of the Literature

| Ultrasound Characteristic and Discriminative Findings | Ganglion Cyst | Synovial Cyst |

|---|---|---|

| Compressibility | No | Yes |

| Location (more frequent) | Wrist, hand, ankle, foot. | Knee (gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa) Hip (iliopsoas bursa). |

| Similar findings | ||

| Blood flow by Doppler evaluation | Absence | Absence or possible |

| Echogenicity | Anechoic to hypoechoic. | Anechoic to hypoechoic. |

| Configuration | Uni or multilocular +/− septations | Uni or multilocular +/− septations |

| Borders | Thin and well defined | Thin and well defined |

| Joint communication | +/− | +/− |

| Posterior acoustic shadowing | +/− | +/− |

Giard, M., Pineda, C. Ganglion cyst versus synovial cyst ? Ultrasound characteristics through a review of the literature. Rheumatol Int 35,597–605 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-3120-1

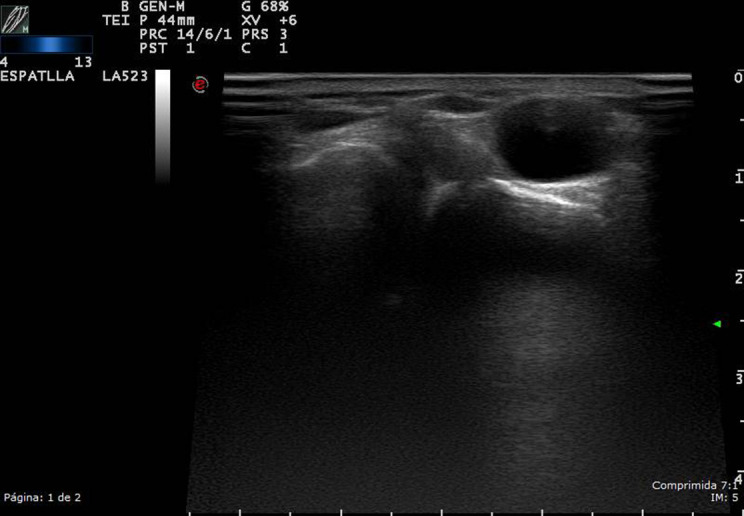

Figure 2.

High-resolution ultrasound ganglion cyst of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, in grayscale from a patient with swelling at the AC joint; a non-compressible, cystic mass with no obvious communication with the joint, at the site of the swelling.

Tenosynovitis is the inflammation of a tendon and its synovial sheath. In US, it shows an increased thickness and heterogeneity in the echo-structure of the affected tendon, as well as the presence of fluid in its tendon sheath (Figure 3).3

Figure 3.

High-resolution ultrasound tenosynovitis of the hand, in a patient with psoriatic arthritis, in grayscale and color Doppler. The longitudinal scan of the fifth finger flexor tendon shows a thickening tendon sheath with signs of synovial proliferation and increased vascularity.

Bursitis is the inflammation of the small fluid-filled pads, called bursae. Ultrasound shows a collection of well-defined anechoic edges, or with fine echoes inside, in the usual bursa location. Color Doppler (CD) can likewise be used to show signs of infection, such as hyperemia of the bursa and the surrounding tissues (Figure 4).4,5

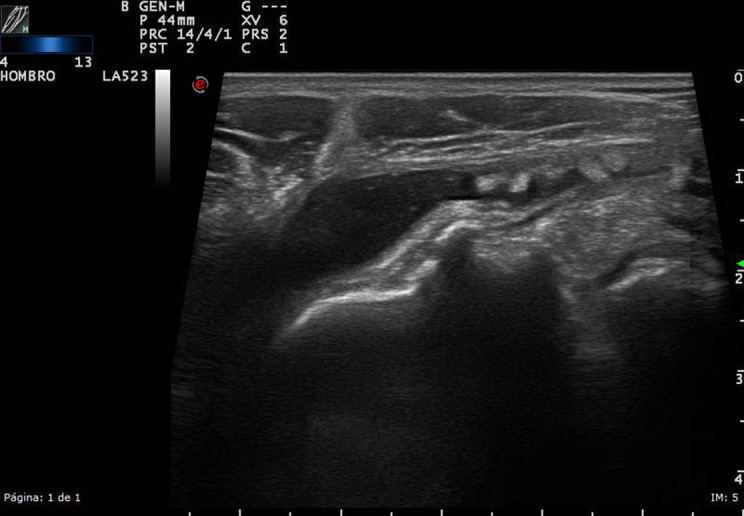

Figure 4.

High-resolution ultrasound bursitis of the shoulder, in a patient with pain and limitation of motion, in grayscale. The longitudinal scan shows the distension of the subdeltoid – subacromial bursitis, with some echoes inside, suggesting microcrystalline disease.

Rheumatoid nodules are more common in overlying joint areas such as the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints. Nodules appear as oval, generally homogenous (85%), hypoechoic (85%) masses closely attached to the bone surface. The size varies from 2 mm to 5 cm; they are firm, non-tender, and movable in subcutaneous tissue.6-8

Tophi are typically in yellow-white color, non-tender, and located within the articular structures, or bursae, and the first MTP joint is the most common but can appear in hands, feet, elbows, and ears.

Sonographically, tophi appear as a heterogeneous mass (80%), composed of hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas, and have poorly defined contours. They can form multiple groups with surrounding anechoic haloes.7,9,10

Benign Tumors

Lipoma is considered the most common soft tissue tumor and is seen in ~2% of the population. They are usually subcutaneous and in US, appear as soft variably echogenic masses. If capsulated, it may be more difficult to identify on US.11

When they present a heterogeneous echotexture, more than minimal CD flow or large-size liposarcoma should be suspected. Few authors suggest that a systematic review on the ultrasonography of the soft-tissue lipomas may help to better ascertain the true diagnostic value of this test and that US is a useful tool in the diagnosis of superficial lipomas with good sensitivity and even better specificity and should still be considered the first diagnostic tool option (Figure 5).12

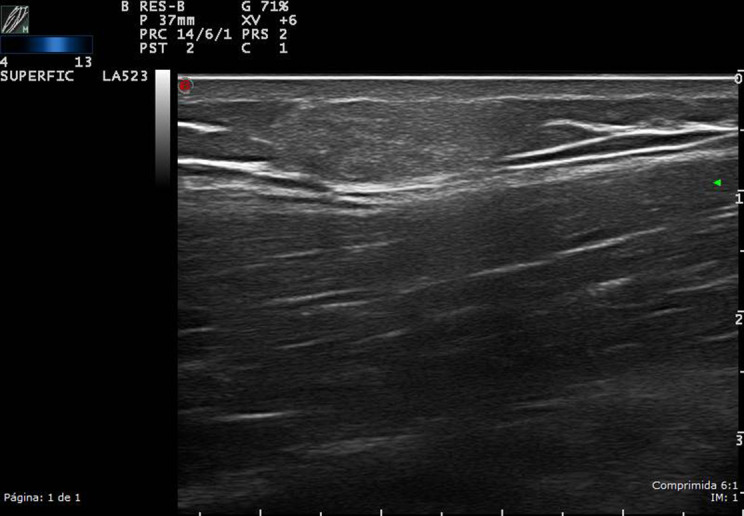

Figure 5.

High-resolution ultrasound lipoma of the right arm in grayscale, in a patient with a soft, slow-growing tumor in the proximal arm. The upper part of the arm was explored: a well-defined, homogeneous, isoechoic oval, superficial lesion of approximately 1.5 cm2.

Nodular fasciitis is typically composed of well-defined, ovoid or lobulated, hypoechoic subcutaneous masses, which may also affect deep muscle fascia.

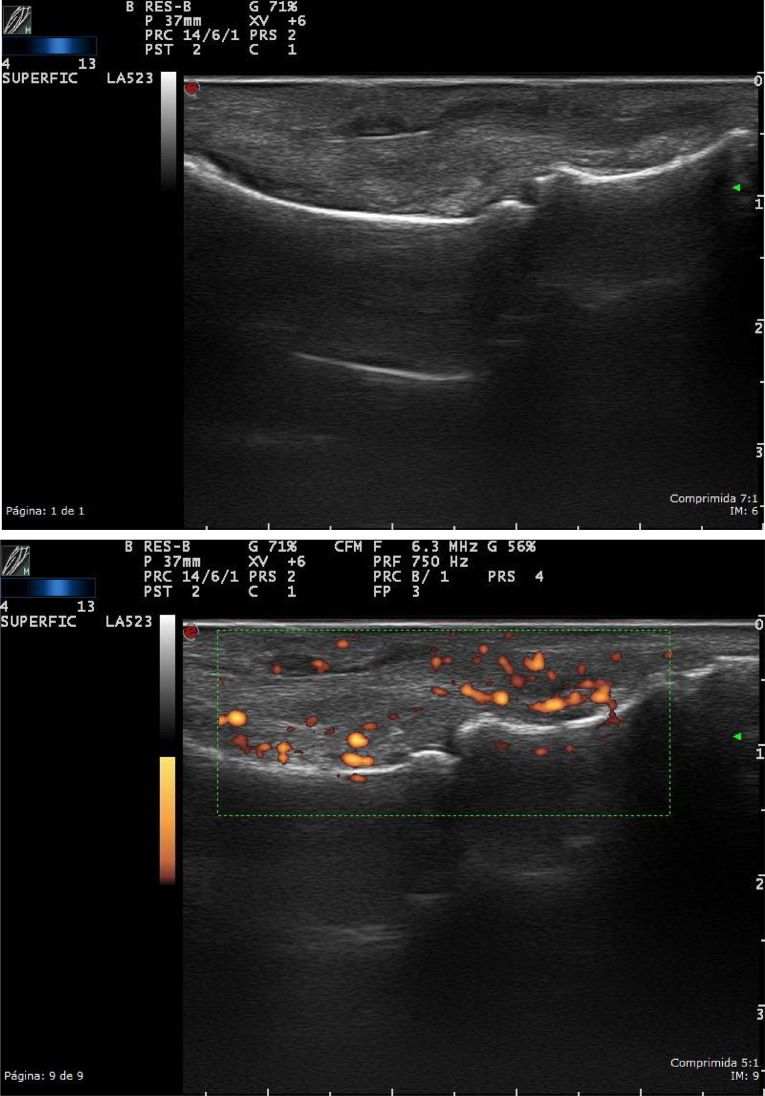

Elastofibroma dorsi has characteristic location (subscapularis) and imaging appearance: US demonstrates a well-defined multi-layered pattern of hypoechoic linear areas of fat deposition intermixed with echogenic fibroelastic tissue (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A soft tissue tumor was studied in a 60-year-old patient located in the scapular area, which was not painful and appeared on mobilization of the scapula. High-resolution ultrasound in grayscale, of subescapularis zone, demonstrates a well-defined multi-layered pattern of hypoechoic linear areas of fat deposition intermixed with echogenic fibroelastic tissue due to elastofibroma dorsi.

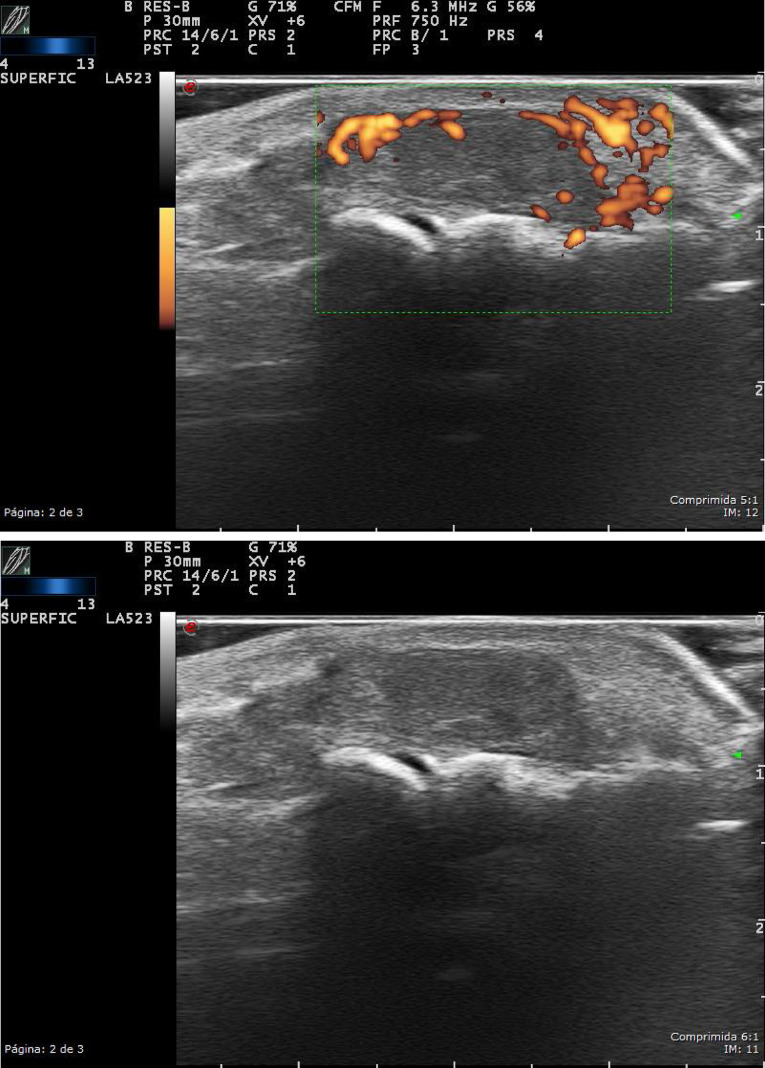

Plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease) or palmar fibromatosis (Dupuytren´s disease) is hypoechoic in US with often a little blurry margination without calcifications or any cystic components, affecting the plantar or palmar fascia, respectively. The lesions may show hypervascularity in a symptomatic phase (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

High-resolution ultrasound in grayscale of the plantar area of the foot in a patient with pain when walking. Ultrasound shows a plantar fibromatosis with hypoechoic heterogenous mass, without calcifications or any cystic components. No hypervascularity was found.

Tenosynovial giant cell tumors arise from the tendon sheath. It is unclear whether these lesions represent neoplasms or are merely reactive masses. Ultrasound allows not only the characterization of the lesion but also describes the relationship with the tendon sheath (Figure 8).13

Figure 8.

High-resolution grayscale and color Doppler ultrasound of the hand, in a young patient with a solitary subcutaneous soft tissue nodule on the volar surface of the second finger. Ultrasound reveals a homogeneous hypoechoic nodule, with hypervascularity, further confirming a tenosynovial giant cell tumors.

Glomus tumor is usually located in acral areas (typical subungual location). Normally painful under pressure, US shows a hypoechoic lesion with significant Doppler vascularity.14

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in US usually present with a defined lesion with markedly heterogeneous echotexture and sometimes contain internal areas, pseudocystic and phleboliths (hyperechoic images with acoustic shadowing). They may have a hyperechoic image (fat) in the periphery of the lesion.14

Schwannomas are benign tumors of the nerve sheath. Pathognomonic features are the connection with a nerve and the presence of tiny inner pseudocysts. They usually are well vascularized without necrotic areas.14

Neurofibromas are circumscribed, spindle-shaped defined masses with typically layered appearance in axial scans. In contrast to schwannomas, vascularization is sparse. Multifocal neurofibromas, plexiform and multifocal variants, may occur in neurofibromatosis type 1 disease (Figure 9).14

Figure 9. A, B.

High-resolution grayscale and color Doppler ultrasound of the ankle. Ultrasound reveals a homogeneus, hypoechoic mass of solid appearance, in the posterior tibial nerve due to a neurofibroma.

Myxomas are the demonstration of a well-defined hypoechoic-anechoic mass surrounding soft tissue and often show a heterogeneous echotexture. Posterior acoustic enhancement may be observed in a significant portion of cases. There may be some internal echoes that are increased through transmission. In ~85% of cases, there is a sonographic bright rim sign of increased echogenicity around the myxoma (i.e., peripheral rim of echogenicity). Frequently, a bright cap sign is seen as a triangular hyperechoic area adjacent to at least one of the poles of the mass. The lesion is hypovascular or avascular on CD US.15,16

Malignant Tumors

Liposarcoma’s sonographic appearance is large, multilobulated, well-defined isoechogenic/hyperechogenic mass, with tiny hyperechogenic lines and hypervascularity, which might contain nodular or globular foci with echotexture other than adipose tissue.17

Myxoid liposarcoma represents 20%-50% of all liposarcomas and has an intermediate malignant behavior. Ultrasound appearance reveals a complex, well-defined hypoechogenic heterogeneous mass, with solid anechoic non-cystic areas, with posterior acoustic enhancement, that might contain thin septa. Moreover, the Doppler assessment shows hypervascularity surrounding the anechoic areas.17

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans represent 6% of all soft tissue sarcomas and it occurs in males between 20 and 50 years old.18 The US assessment shows an ovoid or lobulated circumscribed subcutaneous nodule without posterior acoustic enhancement and constitutes a combination of hypoechoic and hyperechoic regions; however, it can appear entirely as a hyperechogenic mass. Tiny intralesional punctuate non-shadowing echogenic foci may also emerge at the scan evaluation. Typically, it has well-defined contours but may have irregular margins. Power Doppler (PD) shows predominantly hypervascularity in hypoechogenic areas.19

Adult fibrosarcoma is a rare malignant neoplasm. The US imaging shows a non-specific mass, associated with hypoechogenic and hyperechogenic heterogeneous areas, along with calcifications or ossification, relatively hypovascular, and sometimes may present a pseudocapsule formation with tendency to invade adjacent structures.20

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare malignant smooth muscle neoplasm that typically occurs in adults. The US scan shows a well-circumscribed oval hypoechogenic mass, with increased posterior enhancement, and may be seen as variable degree of anechoic areas due to necrotic, cystic changes and hemorrhage, with intralesional Doppler increased blood flow.20

Rhabdomyosarcoma is an aggressive malignant striated muscle tumor and it is the most common soft tissue neoplasm of childhood and adolescence. The rhabdomyosarcoma US imaging lacks specificity; can feature a heterogeneous irregular well-defined mass with low to medium echogenicity and may have anechoic irregular areas in zones of necrosis.21

Glomangiosarcoma or malignant glomus tumor is an extremely infrequent soft tissue sarcoma that has high metastatic risk and it is most frequently reported in the lower extremities and in the gastrointestinal tract.22 Ultrasound characteristics are non-specific, given the lack of cases reported.

Angiosarcoma, at US examination, appears predominantly hypoechoic with the increased flow in color and PD imaging, similar to other malignant soft-tissue masses. Heterogeneity areas can be due to hemorrhage.23

The malignant peripheral nerve tendon sheath tumor constitutes malignant forms of neurofibromas and schwannomas and half of them are associated with neurofibromatosis type I, and 11% of them present after post-radiation therapy.20 Ultrasound cannot distinguish between benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, however, is featured as a homogeneous hypoechogenic and fusiform mass with peripheral nerve continuity and posterior acoustic enhancement.21

Metastases and Lymphomas

The most frequent primary neoplasms which metastasize to muscles are breast carcinomas in woman and lung carcinoma in men. Some metastatic disease rarely affects the skin.24 Ultrasound imaging has low specificity to show the histologic origin of the tumor but predominantly are well-defined, round or lobular hypoechogenic masses with hypervascularity in Doppler assessment.25 Extranodal lymphoma usually appears in extremities, and US shows a hypoechoic mass, with infiltrative margins and significantly increased vascularity; necrosis is commonly absent (Figure 10).21

Figure 10. A, B.

High-resolution grayscale and color Doppler ultrasound of the forearm, in a 53-year-old patient with painless tumor in the front of the forearm, without a history of trauma. A round tumor of less than 1 cm iso/hypoechogenic mass in grayscale was observed, moderately delimited, with an attached vessel that nourished the lesion. An important signal Doppler was observed. Due to signs of suspicion, such as heterogeneity, high vascularity, and a very important Doppler signal, an MRI was requested, which showed a well-defined, rounded, 1 cm image, with hypersignal in T1, leading to a metastatic lesion. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Ultrasound of the Parotid and Submandibular Glands in Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS) is a systemic autoimmune disease that affects 1-23 people/10 000 inhabitants in Europe and presents with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations and a profile of specific autoantibodies (Ab).26 Dryness syndrome dominates the clinical scene and translates an immuno-mediated glandular compromise, accompanied by fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and a systemic picture in a significant percentage of patients, occasionally complicated by lymphoma in 2%-5% of patients.27,28

The diagnosis of the disease is not easy, since different classification criteria have been proposed from the initials of Fox et al.29 even though the most accepted are the American-European of Vitali et al 2002,30 with new updates later in 2012 and 2016.31 None of them has the diagnostic reliability of isolated glandular disease been determined using imaging techniques, such as US. Throughout the history of this disease, an objective and non-invasive technique has been sought to help confirm the diagnosis in a specific way. In 1992, Vitali et al30 began the study of the application of high-resolution US of the parotid and submandibular glands, with the aim of implementing this technique in clinical practice for the diagnosis of SjS. The authors established a US score for glandular lesion severity with heterogeneous results, summarized in a recent review.32 Recent works have compared this glandular lesion by US imaging with magnetic resonance imaging and sialography.33,34 The limitations of these works are the lack of standardization of the technique, which is why Jousse-Joulin et al35 proposed a consensus on how to standardize the evaluation of key findings by US of the salivary glands and their reliability, which includes: echogenicity, homogeneity, hyperechoic bands, number of hypo/anechoic areas, location of these areas in the gland, number of abnormal lymphoid nodules in the gland, calcifications, visible posterior margin; all in the parotid and submandibular glands bilaterally (Table 2). Based on these US findings, the experts confirmed the diagnostic suspicion, ruled out SjS, or assessed it as undetermined. The final conclusion of this international group was that, after evaluating the reliability of the images, the typical glandular pattern of patients with SjS with an inhomogeneous gland with hypoechoic/anechoic areas in its parenchyma observed on US images could be used by experts in salivary gland US along with the other classification criteria in the diagnosis of SjS concomitantly to reach greater final diagnostic certainty (Figures 11 and 12).35 However, the US indices described so far present diverse results due to: the heterogeneity of the patients studied, the differences in the US machines used, the different indices, and finally, but not least, that it is a sonographer-dependent technique. Cornec et al.,36 evaluated the role of glandular US in the diagnosis of SjS, concluding that adding it to the American College of Rheumatology and 2002 classification criteria in clinical practice, sensitivity increases and conversely, the number of biopsies needed decreases, suggesting the performance of biopsies only in those patients with US not suggestive of SjS.

Table 2.

Major salivary gland ultrasonography points and grading method of the submandibular and parotid glands in primary Sjögren Syndrome

| Parotid Glands | Submandibular Glands | |

|---|---|---|

| Left Right |

Left Right |

|

| Echogenicity | ||

| Normal (0); abnormal (fibrosis) 1 | ||

| Homogeneity | ||

| Normal (0); abnormal (1) | ||

| Hyperechoic bands | ||

| None (0); <50% of the parenchyma (1); >50% (2) | ||

| Number of hypoechoic/anechoic area (mm)* | ||

| Size of the largest hypoechoic/anechoic areas (mm)** | ||

| Location of the hypoechoic/anechoic areas in the gland | ||

| None (0); isolated (<25% of the surface area) (1); localized (25-50%) (2); scattered (>50%) (3); diffuse (4) | ||

| Number of abnormal lymph nodes in the gland*** | ||

| Presence of normal lymph nodes at the upper and / or lower poles of the parotid glands: no (0); yes (1) | ||

| Calcifications | ||

| No (0); yes (1) | ||

| Posterior border visible | ||

| No (0); yes (1) | ||

| Diagnosis advice of pSS based on the seven items | ||

| Ruled out (0); indeterminate (1); ruled in (2) |

Quantitative variables were categorized as follows: *number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas: none (0), 1-4 (1), >5 (2); **size of the largest area: none (0), <2 (1), >2 (2), ***abnormal lymph nodes: no (0), yes (1).

Source: Adapted from Jousse-JoulinS et al RMD Open 2017;3:e000364. doi:10.1136/ rmdopen-2016-000364.

pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

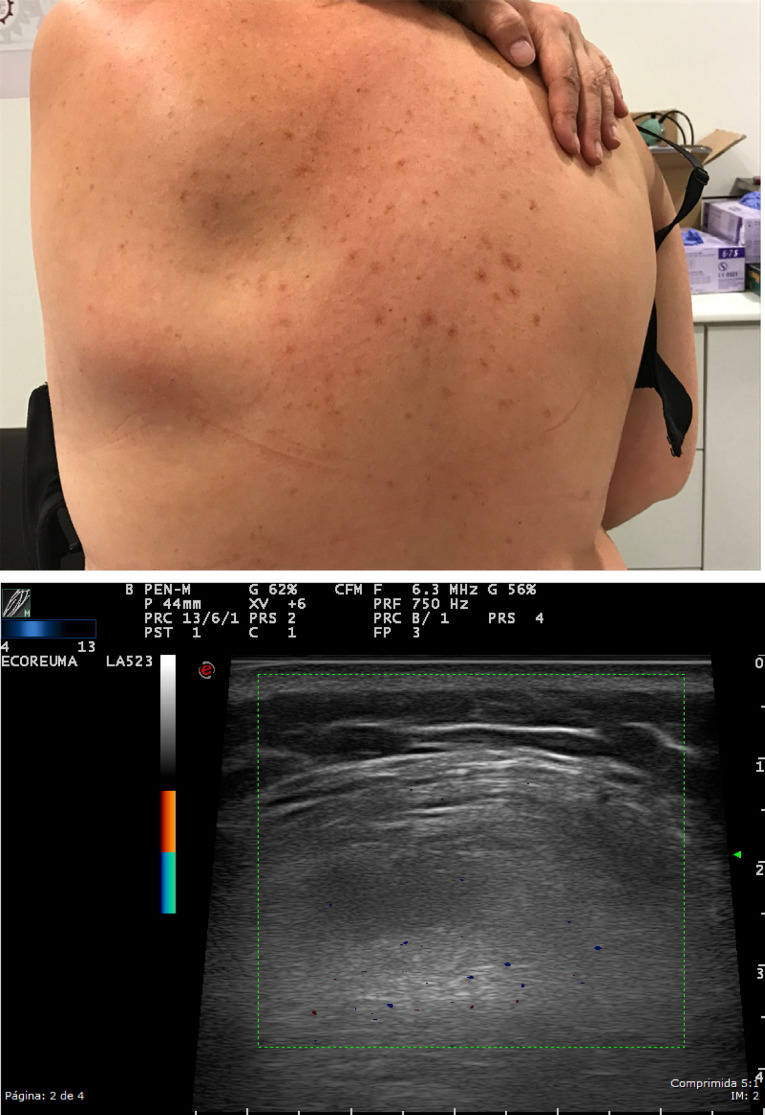

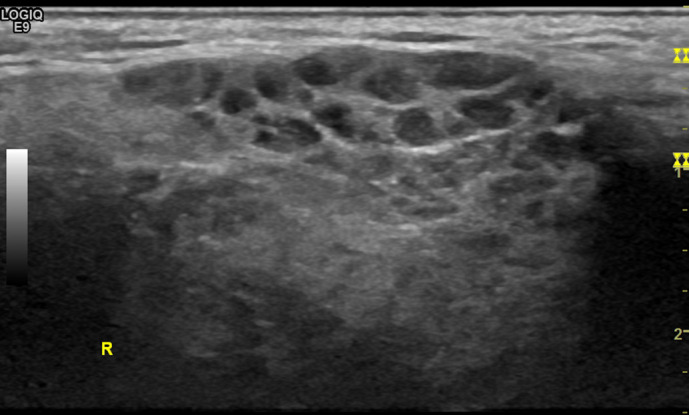

Figure 11.

Parotid gland: high-resolution ultrasound of the parotid gland (EG) in grayscale from a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome. Heterogeneity with numerous hypo/anechoic areas and cystic appearance, without visibility of the posterior border.

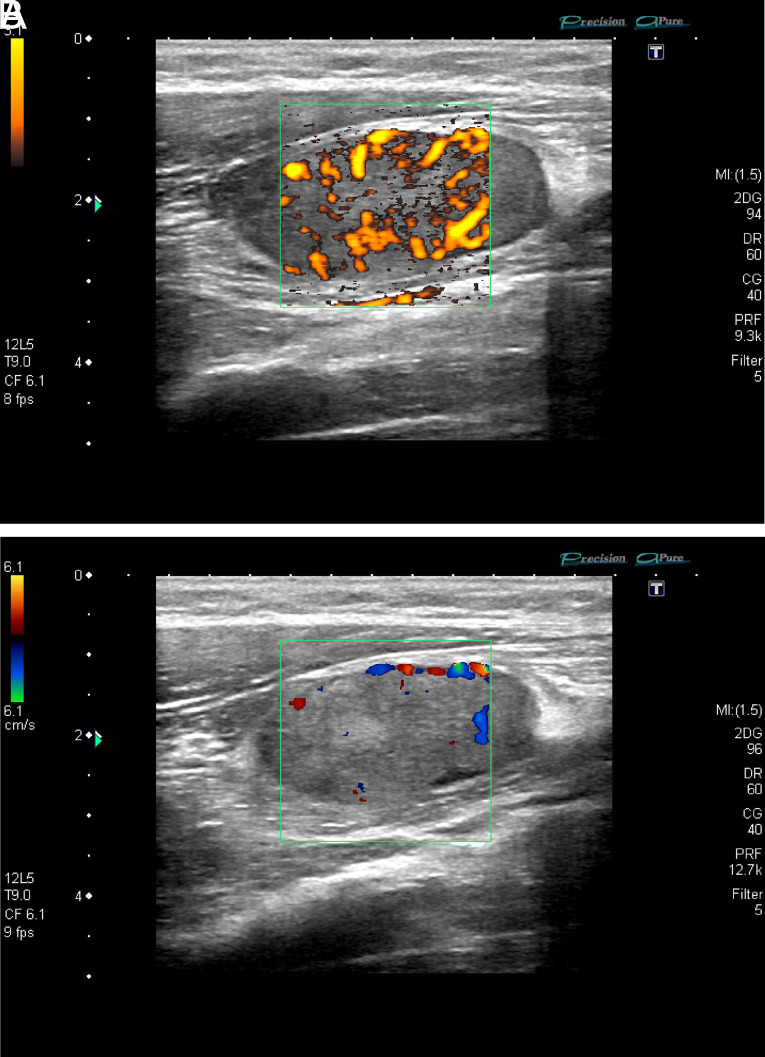

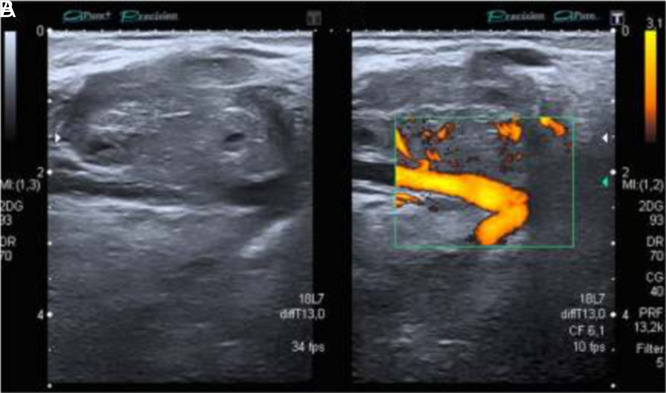

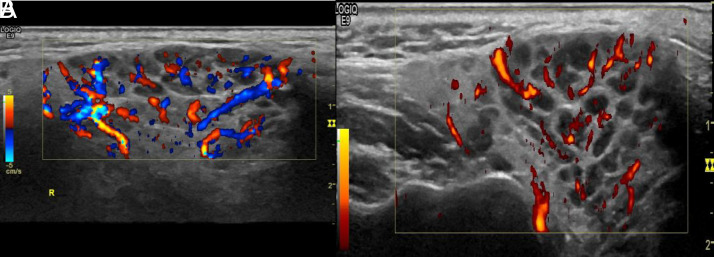

Figure 12. A, B.

Parotid gland: (A, B) high-resolution ultrasound of the same parotid gland (color Doppler/power Doppler from a patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome). Heterogeneity with anechoic, septa, and cystic images with loss of the posterior border.

Besides the gray scale and CD US for the diagnosis of SjS, elastography is increasingly offering some structural information about the gland. Elastography is a non-invasive US method that depicts the elasticity and stiffness of the parenchyma to be measured in vivo after deforming stress. It provides a quantitative/qualitative measurement and a dynamic visualization of this tissue stiffness in a wide variety of clinical structures, especially in soft tissue examinations: breast, thyroid, muscle, and salivary gland (Figure 13).

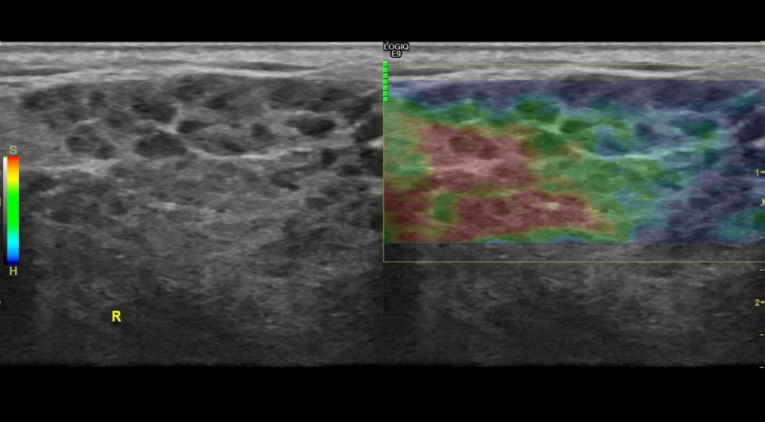

Figure 13.

Parotid gland: elastography of the right parotid gland from a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ultrasound machine with 4D imaging. (GE Logic 9). Heterogeneous density with cystic areas and soft and compressible differentiated focal glandular images (S-red) and rigid non-compressible areas (H-blue).

The different elastographic modalities are based on the fact that different pathological processes, which can be inflammatory, fibrotic, or tumor, can cause disturbances in tissue elasticity. As a tool, elastography is reproducible, measures differences in parenchymal stress, and offers high precision in measurements integrated into a color spectrum (elastographic score). At the same time, it obtains pressure ratios in numerical values thanks to specific software. The applicability of elastography in the study of liver, muscle, or breast tissue has been progressively extended, but there are currently very few studies that have attempted to influence the role that diagnosis of glandular involvement of SjS may have.37,38

To summarize, gray scale (EG) and CD or PD US study for the SjS offers detailed information on the structural lesions of the gland according to the currently accepted score.39 In a short period of time, it will become a necessary tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with SjS since it could be key in improving diagnostic sensitivity, increasing glandular structural definition, describing the inflammatory versus fibrotic pattern, and improving the monitoring while reducing the number of salivary gland biopsies. Conversely, although elastography is also non-invasive, accessible, and fast, the weakness of preliminary data does not allow us to know the real role it has played so far.

Funding Statement

The authors declare that this study had received no financial support.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – H.C.; Design – D.R.; V.N.; Supervision – H.C.; Literature Review – H.C.; D.R.; V.N.; O.C.; Writing – H.C., D.R., V.N., O.C.; Critical Review – H.C., D.R.

Declaration of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1. Vanhoenacker F, Van Goethem JWM, Vandevenne JE, Shahabpour M. Synovial tumors. Imaging of Soft Tissue Tumors. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg; 2001:273 300. Accessed September 3, 2020. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-07856-3_16. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carra BJ, Bui-Mansfield LT, O’Brien SD, Chen DC. Sonography of musculoskeletal soft-tissue masses: techniques, pearls, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(6):1281 1290. ( 10.2214/AJR.13.11564) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ray G, Tall MA. Tenosynovitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31335044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parker RH. Bursitis. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015:445 447. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513340/. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corominas H, Balius R, Estrada-Alarcón P, Reina D, Moya P, Videla M. Giant pes anserinus bursitis: A rare soft tissue mass of the medial knee. Reumatol Clin. 2021;17(7):420 421. ( 10.1016/j.reumae.2020.06.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Askari A, Moskowitz RW, Goldberg VM. Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules and serum rheumatoid factor without arthritis. JAMA. 1974;229(3):319 320. ( 10.1001/jama.1974.03230410043024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Selim N, Hector C, Benjamin H, Chen Lan X, Ralph SH, Tasanee K. Ultrasonography for assessment of subcutaneous nodules | Request PDF. The Journal of Rheumatology. Accessed September 3, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10728252_Ultrasonography_for_assessment_of_subcutaneous_nodules. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rheumatoid nodules. UpToDate. Accessed September 3, 2020 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rheumatoid-nodules. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dirken-Heukensfeldt KJM, Teunissen TAM, Van De Lisdonk H, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Clinical features of women with gout arthritis. A systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(6):575 582. ( 10.1007/s10067-009-1362-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Ávila Fernandes E, Kubota ES, Sandim GB, Mitraud SAV, Ferrari AJL, Fernandes ARC. Ultrasound features of tophi in chronic tophaceous gout. Skelet Radiol. 2011;40(3):309 315. ( 10.1007/s00256-010-1008-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murphey MD, Carroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of the AFIP: Benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. RadioGraphics. 2004;24(5):1433 1466. ( 10.1148/rg.245045120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rahmani G, McCarthy P, Bergin D. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for soft tissue lipomas: a systematic review. Acta Radiol Open. 2017;6(6). ( 10.1177/2058460117716704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Middleton WD, Patel V, Teefey SA, Boyer MI. Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath: analysis of sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(2):337 339. ( 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830337) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ESR, European Society of Radiology. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.myesr.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petscavage-Thomas JM, Walker EA, Logie CI, Clarke LE, Duryea DM, Murphey MD. Soft-tissue myxomatous lesions: review of salient imaging features with pathologic comparison. RadioGraphics. 2014;34(4):964 980. ( 10.1148/rg.344130110) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Girish G, Jamadar DA, Landry D, Finlay K, Jacobson JA, Friedman L. Sonography of intramuscular myxomas: The bright rim and bright cap signs. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(7):865 86 9. ( 10.7863/jum.2006.25.7.865) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shimamori N, Kishino T, Morii T.et al. Sonographic appearances of liposarcoma: correlations with pathologic subtypes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45(9):2568 2574. ( 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.05.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Snow SN, Gordon EM, Larson PO, Bagheri MM, Bentz ML, Sable DB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a report on 29 patients treated by Mohs micrographic surgery with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Cancer. 2004;101(1):28 38. ( 10.1002/cncr.20316) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shin YR, Kim JY, Sung MS, Jung JH. Sonographic findings of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(2):269 274. ( 10.7863/jum.2008.27.2.269) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Widmann G, Riedl A, Schoepf D, Glodny B, Peer S, Gruber H. State-of-the-art HR-US imaging findings of the most frequent musculoskeletal soft-tissue tumors. Skelet Radiol. 2009;38(7):637 649. ( 10.1007/s00256-008-0602-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stramare R, Beltrame V, Gazzola M.et al. Imaging of soft-tissue tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(4):791 804. ( 10.1002/jmri.23791) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abu-Zaid A, Azzam A, Amin T, Mohammed S. Malignant glomus tumor (glomangiosarcoma) of intestinal ileum: a rare case report. Case Rep Pathol. 2013. ( 10.1155/2013/305321) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaballah AH, Jensen CT, Palmquist S.et al. Angiosarcoma: clinical and imaging features from head to toe. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1075). ( 10.1259/bjr.20170039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corominas H, Estrada P, Reina D, Cerdà-Gabaroi D. Ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for skin metastasis of a prostate adenocarcinoma. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12(1):54 56. ( 10.1016/j.reuma.2015.03.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park SB, Kang BS. Value of ultrasonographic evaluation for soft-tissue lesions: focus on incidentally detected lesions on CT/MRI. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35(9):485 494. ( 10.1007/s11604-017-0657-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brito-Zerón P, Baldini C, Bootsma H.et al. Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16047. ( 10.1038/nrdp.2016.47) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Díaz-López C, Geli C, Corominas H.et al. Are there clinical or serological differences between male and female patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(7):1352 1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Birt JA, Tan YM, Mozaffarian N. Sjögren’s syndrome: managed care data from a large United States population highlight real-world health care burden and lack of treatment options. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(1):98 107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fox RI, Robinson CA, Curd JG, Kozin F, Howell FV. Sjögren’s syndrome. Proposed criteria for classification. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(5):577 585. ( 10.1002/art.1780290501) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R.et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. BMJ Publishing Group; 2002;62:554 558. Accessed July 4, 2020. www.annrheumdis.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R.et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;69(1):35 45. Accessed July 4, 2020. /pmc/articles/PMC5650478/?report=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luciano N, Ferro F, Bombardieri S, Baldini C. Advances in salivary gland ultrasonography in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(5):159 164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baldini C, Zabotti A, Filipovic N.et al. Imaging in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: the “obsolete and the new.” Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(3):215 221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Niemelä RKN, Takalo R, Paä E.et al. Ultrasonography of salivary glands in primary SjögrenSjögren’s syndrome. A comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance sialography of parotid glands. Rheumatology. 2004;43:875 87 9. Accessed July 4, 2020. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article-abstract/43/7/875/2899091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jousse-Joulin S, Nowak E, Cornec D.et al. Salivary gland ultrasound abnormalities in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: consensual US-SG core items definition and reliability. RMD Open. 2017;3(1):e000364. ( 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000364) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cornec D, Jousse-Joulin S, Pers JO.et al. Contribution of salivary gland ultrasonography to the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome: toward new diagnostic criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):216 225. ( 10.1002/art.37698) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cindil E, Oktar SO, Akkan K.et al. Ultrasound elastography in assessment of salivary glands involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Imaging. 2018;50:229 234. . ( 10.1016/j.clinimag.2018.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Klauser AS, Miyamoto H, Bellmann-Weiler R, Feuchtner GM, Wick MC, Jaschke WR. Sonoelastography: musculoskeletal applications. Radiology. 2014;272(3):622 633. ( 10.1148/radiol.14121765) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hofauer B, Mansour N, Heiser C.et al. Sonoelastographic modalities in the evaluation of salivary gland characteristics in Sjögren’s syndrome. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42(9):2130 2139. ( 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a