Abstract

We present a case of secondary T-cell deficiency particularly affecting CD4 T cells, along with the emergence of chronic spontaneous urticaria in a patient following COVID-19 vaccination. The condition was partially managed with omalizumab after initial first-line therapy proved ineffective.

Key words: Secondary T-cell deficiency, chronic spontaneous urticaria, COVID-19 vaccine, omalizumab, idiopathic total lymphopenia, autoimmune-induced lymphopenia

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic prompted a global race to develop vaccines, with the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (ChAdOx1/AZD1222) emerging as a key player. This adenoviral vector vaccine has proved effective in preventing severe illness. However, concerns about its safety have been raised owing to potential adverse reactions, ranging from mild local symptoms to rare but serious events such as thrombotic events with thrombocytopenia syndromes and autoimmune hepatitis.1,2 Despite these concerns, there have been no reported cases of secondary T-cell deficiency following administration of this vaccine. Here, we present a case report detailing spontaneous urticaria and an associated idiopathic total lymphopenia following administration of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

The patient, a 64-year-old man with asthma who was not under active treatment, received the vaccine in April 2021; he had no prior contact with simian viruses or ChAdOx1 vaccination. Two weeks later, he developed an extensive migratory urticarial rash on his trunk and proximal limbs (Fig 1). The rash persisted despite commencement of high doses of antihistamines. His physical examination findings were unremarkable, with no reported symptoms of dyspnea, angioedema, arthritis, or systemic issues.

Fig 1.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria 2 weeks after vaccination.

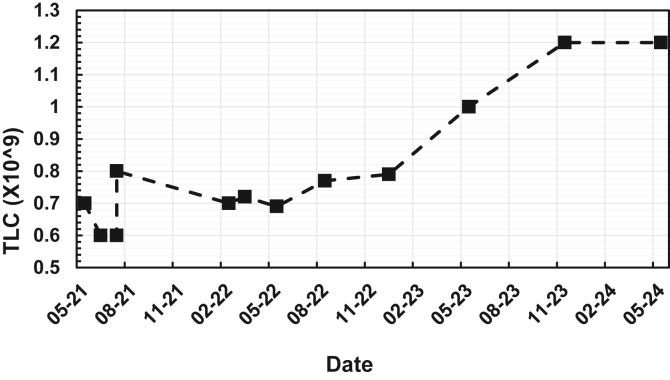

The patient was evaluated by the dermatology department, and a skin biopsy sample suggested urticarial vasculitis, although direct immunofluorescence was not supportive. A referral to our clinic was made pursuant to a total lymphocyte count (TLC) of 0.7 × 109/L (reference range 1.0-4.0 × 109/L), with no prior abnormal TLC values (Fig 2). A comprehensive immunologic workup was conducted, revealing mildly elevated inflammatory markers, including an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 16 mm per hour and a C-reactive protein level of 10 mg/L. He had tested positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) with an associated low positive result of testing for myeloperoxidase antibodies (2.6 AI [reference range <1.0 AI]). Negative test results were also obtained for antinuclear antibodies), anti–double-stranded DNA, extractable nuclear antigen, tryptase, and lactate dehydrogenase. The results of serum protein electrophoresis were also negative, and the patient’s level of free light chains was within the normal range.

Fig 2.

TLC, 2021-2024.

During ongoing close follow-up, the patient’s lymphopenia persisted, and he continued to experience urticaria flares. Despite being trialed on additional nizatidine for urticaria, his Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) was 35 of 42. Therefore, he began receiving 300 mg of omalizumab monthly by June 2021, with that dose increased to 600 mg by July 2022 for his persistent flares. He was later vaccinated with the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine without any adverse effects. Lymphocyte subset analysis revealed a sustained lymphopenia alongside a normal white cell count of 5.00 × 109/L (reference range 4.0-11.0 × 109/L), which was secondary to a significant CD4 T-cell lymphopenia of 80 × 109/L (reference range 389-1569 × 109/L) and a borderline B-cell count of 96 × 106/L (reference range 102-594 × 106/L). Memory B-cell analysis showed a slightly increased marginal zone B-cell population of 39.1% (reference range 7.0%-23.0%). The patient’s CD4 T-cell lymphopenia was due to a marked decrease in level of naive CD4 T cells (15 × 106/L [reference range 122-573 × 106/L]) (Fig 2). No clonal lymphocyte population was detected by flow cytometry.

The patient had no notable infections during the follow-up period, but he did exhibit impaired T-cell proliferation, with PHA stimulation showing a rate of 43.7% compared with 95.7% in the control (by a flow-based assay using intracellular Ki67 staining). Furthermore, his immunoglobulin profile demonstrated an IgG level of 10.9 g/L (reference range 7.5-15.6 g/L), IgM level of 1.5 g/L (reference range 0.4-3.0 g/L), and IgA level of 1.1 g/L (reference range 0.8-4.5 g/L).

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis was dismissed after testing established normal C3, C4, and C1q levels. The results of tests for Helicobacter antibodies, strongyloidiasis, HIV, and hepatitis B and C were negative. Because of his CD4 lymphopenia, the patient began prophylactic treatment for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Montelukast, 10 mg daily, was added to improve urticarial control.

The patient contracted COVID-19 during treatment, but there was no exacerbation of his chronic spontaneous urticaria rash or change in his TLC. By May 2023, the patient’s TLC increased, with his level of CD4 T cells rising to 165 × 106/L (Fig 2). His levels of CD8 T, natural killer, and B cells remained normal. Although the result of testing for ANCA remained positive (a myeloperoxidase level of 4.4 IU/mL), the levels of the patient’s other inflammatory markers provided reassurance. The patient’s urticaria did not exhibit typical vasculitis characteristics, and no renal function complications or other vasculitis complications were observed. The patient’s CD4 lymphopenia, which is not typical of vasculitis, suggests that his increase in ANCA level was due to the overall inflammatory process.

At this point in time, the patient has experienced a period of stability, suggesting that his symptoms were due to chronic spontaneous urticaria. As a result, his omalizumab dosage was reduced from 600 mg to 300 mg per month, eliminating the need for high-dose antihistamines. We implemented a strategy to gradually reduce the dosage of omalizumab every 8 weeks, while also administering additional pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 13-valent; herpes zoster vaccine; pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23-valent; and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine to prevent further complications.

To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of secondary T-cell deficiency following administration of COVID-19 vaccine. The precise mechanism underlying this occurrence remains unknown, although there have been numerous reports highlighting the association between COVID-19 vaccination and autoimmune disorders. A speculating hypothesis involves molecular mimicry between antigenic epitopes of the virus and certain human proteins, potentially leading to an inflammatory response in predisposed individuals, thereby triggering an autoimmune cascade.3 Similar phenomena have been observed in conditions such as post–COVID-19 inflammatory myopathies, transient cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and demyelinating polyneuropathy.4, 5, 6

The incidence of spontaneous urticaria with an associated lymphopenia could be assumed to be interconnected. Systemic autoimmune cascade and inflammation can contribute to lymphopenia, as these might disrupt the normal homeostasis of lymphocytes, causing abnormal proliferation and death of these cells, thus further exacerbating lymphopenia.7 Ultimately, a defective immune regulation can manifest as various autoimmune phenomena, including urticaria.8

Nonetheless, it is important to note that such occurrences are rare and could be influenced by a multitude of factors, including environmental influences, genetic predisposition, hormonal changes, and life stressors.9 Consequently, this case report may serve as an initial piece of evidence warranting further research aimed at understanding and treating autoimmune-induced lymphopenia.

Data sharing statement: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary material.

Disclosure statement

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Sara Barnes for her supervision and invaluable guidance throughout the project. Also, special thanks to Dr Marsus Pumar for his insights, critical revisions, and feedback, which have been instrumental in the completion of this work.

Footnotes

Patient consent: The patient has given informed consent for the distribution of information and media. The risks associated with the patient’s unique medical condition, including the potential for identification owing to its rarity, were thoroughly explained. Despite these risks, the patient has approved implementation of the study.

References

- 1.Sharifian-Dorche M., Bahmanyar M., Sharifian-Dorche A., Mohammadi P., Nomovi M., Mowla A. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis post COVID-19 vaccination; a systematic review. J Neurol Sci. 2021;428 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton-Chubb D., Schneider D., Freeman E., Kemp W., Roberts S.K. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccine. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1249–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappello F., Marino Gammazza A., Dieli F., Conway de Macario E., Macario A.J. Does SARS-CoV-2 trigger stress-induced autoimmunity by molecular mimicry? A hypothesis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2038. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gil-Vila A., Ravichandran N., Selva-O’Callaghan A., Sen P., Nune A., Prithvi Sanjeevkumar Gaur P.S., et al. COVID-19 vaccination in autoimmune diseases (COVAD) study: vaccine safety in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Muscle Nerve. 2022;66:426–437. doi: 10.1002/mus.27681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmer S., Bourke J., Nima Mesbah Ardakani. Transient cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis following ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. Case Rep. 2022;15 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2022-250913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza A., Oo W.M., Giri P. Inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy after the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine may follow a chronic course. J Neurol Sci. 2022;436 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheu T.T., Chiang B.L. Lymphopenia, lymphopenia-induced proliferation, and autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4152. doi: 10.3390/ijms22084152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracken S.J., Abraham S., MacLeod A.S. Autoimmune theories of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Front Immunol. 2019;10:627. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moutsopoulos H.M. Autoimmune rheumatic diseases: One or many diseases? J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]