Abstract

Background:

Intermittent hypoxemia (IH) events are common in preterm neonates and are associated with adverse outcomes. Animal IH models can induce oxidative stress. We hypothesized that an association exists between IH and elevated peroxidation products in preterm neonates.

Methods:

Time in hypoxemia, frequency of IH, and duration of IH events were assessed from a prospective cohort of 170 neonates (<31 weeks gestation). Urine was collected at one week and one month. Samples were analyzed for lipid, protein, and DNA oxidation biomarkers.

Results:

At one week, adjusted multiple quantile regression showed positive associations between several hypoxemia parameters with various individual quantiles of isofurans, neurofurans, dihomo-isoprostanes, dihomo-isofurans, and ortho-tyrosine and a negative correlation with dihomo-isoprostanes and meta-tyrosine. At one month, positive associations were found between several hypoxemia parameters with quantiles of isoprostanes, dihomo-isoprostanes and dihomo-isofurans and a negative correlation with isoprostanes, isofurans, neuroprostanes, and meta-tyrosine.

Conclusions:

Preterm neonates experience oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA that can be analyzed from urine samples. Our single-center data suggest that specific markers of oxidative stress may be related to IH exposure. Future studies are needed to better understand mechanisms and relationships to morbidities of prematurity.

Category of study: clinical

Introduction

The fetal to neonatal transition activates multiple metabolic pathways critical for extrauterine life, including the antioxidant system. Under normal circumstances, the fetal enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant system matures during the final weeks of the third trimester.1 At parturition the newborn emerges into an oxygen rich environment and oxygenation and ventilation is initiated via the lungs instead of the placenta, raising tissue oxygenation within minutes of birth. A portion of oxygen forms reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are neutralized or scavenged by inherent antioxidant pathways. The preterm infant has immature antioxidant defenses and a proclivity for oxidative tissue injury. Furthermore, preterm infants often require supplemental oxygen immediately after birth and for subsequent days and weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) resulting in elevated oxidative stress.2 As a consequence, the postnatal increase in oxygen contributes to generation of ROS and enhanced oxidative damage in the preterm infant, constituting a “free radical disease of prematurity.” 3

ROS act upon cellular molecules to produce oxidized derivatives, thus relative oxidative stress can be characterized by measuring molecular biomarkers of oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA (Figure 1). Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are ubiquitous lipids present in the central nervous system and other cell membranes. PUFAs undergo lipid peroxidation to form detectable cyclic products in human biofluids. Arachidonic acid is oxidized through enzymatic reactions to form prostacyclin, prostaglandins, thromboxane, and other biologically active molecules. When antioxidant defenses are overwhelmed by ROS, non-enzymatic peroxidation of arachidonic acid produces isoprostanes (IsoPs) and isofurans (IsoFs). IsoPs have been associated with a normoxic environment, while IsoFs are preferentially generated under hyperoxic conditions.4 The PUFA docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is abundantly found in the central nervous system, more specifically the cerebral grey matter and retina. Peroxidation of DHA gives rise to neuroprostanes (NeuroPs) and neurofurans (NeuroFs) in a similar manner, and these are markers of neuronal oxidative damage.5 Adrenic acid is present in the cerebral white matter and retina with oxidation products of dihomo-isoprostanes (dihomo-IsoPs) and dihomo-isofurans (dihomo-IsoFs).6 Several amino acid residues can be oxidized by free radicals. Protein phenylalanine (Phe) residues react with hydroxyl radicals to convert Phe into ortho-tyrosine (o-Tyr) or meta-tyrosine (m-Tyr) that can be detected in the urine;2,7 both o-Tyr and m-Tyr are not otherwise physiologically produced. The main oxidative damage to DNA is 2-deoxyguanosine (2dG) oxidation to 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG). Oxidized nucleosides and bases excreted into the urine do not undergo further metabolization processes4 and thus can be quantitatively measured in the urine;7 expressed as the ratio of damaged to undamaged 2-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG/2dG).

Figure 1. Biochemical Products Resulting from Oxidative Stress.

Preterm neonates are at risk for oxidative stress that may result from intermittent hypoxemia (IH) induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can damage lipids, protein, and DNA to form oxidative biomarkers that are excreted in the urine.

Hypoxemia events and re-oxygenation resulting in intermittent hypoxemia (IH) are prevalent in preterm neonates8 and increased IH events over the first days and month of life are associated with adverse neural and pulmonary outcomes and mortality.9,10 ROS are abundantly produced in human fetal cells exposed to cycles of intermittent hypoxia-hyperoxia.11 Animal models have shown that some IH events are capable of inducing oxidative stress.12 We have previously shown in a moderate preterm cohort (31 – 33 6/7 weeks gestation) with relatively few co-morbidities that IH frequency was positively associated with PUFA peroxidation.13

The aim of this cross-sectional analysis was to determine the associations between hypoxemia events and urinary oxidative biomarkers at one week and one month of age in preterm infants <31 weeks gestation. We hypothesized that an association exists between IH and elevated peroxidation products in preterm neonates.

Methods

Subjects

The current study represents a pre-planned secondary cross-sectional biomarker analysis in a prospective cohort study of preterm infants less than 31 weeks gestational age (GA) enrolled between 2019–2021 at the tertiary level 4 NICU at UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio, USA. The cohort study was the Prematurity-Related Ventilatory Control (Pre-Vent) study at the Case Western Reserve University site; infants less than 29 weeks GA were also co-enrolled in the multi-center study.14 Inpatients in the NICU were eligible for this parent cohort study if they were born ≤30 6/7 weeks GA and <7 days postnatal age without major congenital anomalies. Infants were included in this cross-sectional analysis if they had matched IH data and at least one urine sample at the given timepoint(s). The institutional review board at University Hospitals in Cleveland, OH approved the study (#041626). Written parental consent was obtained.

Clinical parameters

Clinical data were extracted from the electronic medical record or short maternal survey (self-identified race/ethnicity, maternal education, tobacco use during pregnancy). For infants on supplemental oxygen, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was recorded from the respiratory equipment at the time of urine collection. An effective FiO2 was calculated for infants on oxygen nasal cannula using the equations from the STOP-ROP trial.15 Chorioamnionitis was defined by clinical diagnosis and/or placental pathology. Severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) was made by radiologic diagnosis of a Grade 3 or 4 IVH by head ultrasound during hospitalization. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University Hospitals (UH REDCap: Clinical and Translational Science Award - UL1TR002548).

Measurements of intermittent hypoxemia

Oxygen saturation (SpO2) was continuously recorded from the bedside oximeter (averaging time = 8 seconds, sample rate = 1 hz; Masimo, Radical-7, Irvine, CA) using a custom data acquisition system (National Instrument, Hungary and Labview, Austin, TX). Oxygen saturation targets during the timeframe of this study were a goal SpO2 of 90–95% if in supplemental oxygen titrated by the bedside nurse or respiratory therapist. The percent time hypoxemic was the percentage of cumulative time with SpO2 < 80% over the preceding 24 hours. IH was defined as SpO2 < 80% for > 10 seconds and < 5 minutes using previously validated software (Matlab, Natick, MA).16 Duration thresholds were chosen to distinguish IH events from sustained hypoxemia. Based on the temporal relationship reported by Kuligowski et. al,17 urinary oxidative biomarkers were correlated with hypoxemia parameters in the preceding 24 hr window. Periods with 0% SpO2 or 0 bpm for heart rate were considered artifact and removed from the data. Additional signal loss occurred due to corrupt or software error in writing to data files. Data were normalized for the 24-hour period preceding urine collection to account for any missingness.

Measurements of urinary oxidative biomarkers

For lipid peroxidation and protein and DNA oxidation analysis, urine samples were collected using cotton balls/Hollister bags during the end of the 1st week of age (7 ± 3 days) and 1st month of age (30 ± 5 days) as previously described.13 Urine was aliquoted and stored in microcentrifuge tubes at −80°C. Samples were shipped frozen on dry ice to University & Polytechnic Hospital La Fe, Valencia, Spain. At time of analysis, samples were thawed on ice, homogenized in vortex, and centrifuged. For lipid peroxidation analyses, samples were additionally subjected to solid phase extraction followed by evaporation-dissolution using Discovery® DSC-18 SPE 96-well plates (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Recovered extracts were analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) performed on an Acquity-Xevo TQS system (Waters, Milford, MA) according to previously developed methods for lipids6,17,18 and protein and DNA7 oxidation biomarkers.

All raw UPLC-MS/MS data were processed with the MassLynx v4.2 software (Waters, Milford, MA). A semi-quantitative analysis of total lipid peroxidation parameters was performed as it has been reported elsewhere.6,17–19 Briefly, a total area of UPLC-MS/MS profiles of selective signals to IsoPs, IsoFs, NeuroPs, NeuroFs, dihomo-IsoPS, and dihomo-IsoFs were obtained and normalized by the average signals of isotopically labeled internal standards (i.e., 15-F2t-IsoP-D4, 10-epi-10-F4t-NeuroP-D4, and PGF-2α-D4). For DNA and protein oxidation biomarkers a quantitative determination was carried out employing pure standards of Phe, p-Tyr, o-Tyr, m-Tyr, 2-dG, and 8OHdG to build linear internal standard calibrations with isotopically labeled compounds (i.e. phenylalanine-D5, p-tyrosine-D2, 2-deoxyguanosine-13C15N, 8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine-13C15N2).7 In some situations, there was not adequate urine volume to perform multiple UHPLC-MS/MS runs, subject numbers for each variable are noted in Table 2. Samples below the limits of quantification (<LOQ) were imputed as zero in the analyses. Total and quantified parameters were normalized to sample creatinine concentration (DetectX® creatinine detection kit, Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Table 2: Quantified Oxidative Stress Biomarkers.

8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine/ 2-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG/2dG), Interquartile range (IQR), Procedure defined unit (p.d.u.); p-values indicate biomarker comparisons between 1st week and 1st month group medians by Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

| Urinary Oxidative Stress Biomarkers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Biomarker | End of 1st Week | End of 1st Month | Comparison | |||

| n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | p-value | ||

| Lipid peroxidation biomarkers (p.d.u.) | Isoprostanes | 154 | 328.5 (201.2, 625.0) | 150 | 340.7 (225.7, 476.5) | 0.176 |

| Isofurans | 154 | 729.5 (295.7, 1795.5) | 150 | 188.3 (99.3, 308.1) | <0.001 | |

| Neuroprostanes | 154 | 41.1 (19.5, 78.6) | 150 | 194.9 (67.2, 491.5) | <0.001 | |

| Neurofurans | 154 | 14.1 (3.5, 25.8) | 150 | 15.6 (5.3, 29.3) | 0.271 | |

| Dihomo-Isoprostanes | 154 | 42.8 (28.1, 76.2) | 150 | 21.0 (13.9, 30.9) | <0.001 | |

| Dihomo-Isofurans | 154 | 98.7 (61.8, 195.0) | 150 | 93.7 (59.4, 139.1) | 0.014 | |

| Protein oxidation biomarkers (nmol L−1) | meta-Tyrosine | 165 | 108.3 (76.5, 158.7) | 158 | 116.7 (63.8, 194.3) | 0.081 |

| ortho-Tyrosine | 165 | 386.4 (275.3, 585.8) | 158 | 532.4 (357.0, 846.0) | <0.001 | |

| DNA oxidation biomarker | 8OHdG/2dG | 165 | 78.6 (50.9, 128.6) | 158 | 79.3 (50.6, 145.8) | 0.207 |

A detailed experimental protocol of UPLC-MS/MS parameters are available in the Supplemental Materials.

Statistical Analyses

The oxidative biomarkers were not normally distributed so Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare 1st week and 1st month biomarker group medians. The datasets did not meet assumptions of normalcy or equal variance so mixed multiple quantile regression analyses, mixed effects for same family exchangeable correlations for siblings, were performed on the associated biomarker outcome by quantiles.20 Adjusted beta-coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values are reported separately for the 25th quantile (Q25), the median 50th quantile (Q50), and the 75th quantile (Q75) of each oxidative biomarker. Co-variants were chosen a priori. Co-variants included in the adjusted regression models were gestational age at birth, sex, black race, birthweight Z-score, caffeine within 7 days of urine collection, chorioamnionitis, day of age at collection, effective FiO2 at collection, Fenton birthweight category (small, appropriate, or large for gestational age), maternal tobacco use, and intubated with an endotracheal tube at time of urine collection. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). The parent cohort study included 175 infants and was powered for the primary outcomes of length of hospitalization and post-discharge respiratory wheeze.

Results

Of the 175 infants enrolled in the parent cohort study, 170 subjects had a urine sample at one or both time points. Valid oximetry recordings and paired urine sample data were available for 165 subjects at the end of the 1st week of age and 159 subjects at the end of the 1st month of age. Of the 5 cases without 1st week data, all 5 had 1 month data. One subject was excluded for postnatal diagnosis of a major congenital anomaly. Seven infants died during hospitalization. Parental request was withdrawn for two infants. Missing or unknown values were excluded from the Table 1 denominators as noted. Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Patient Characteristics.

Median (Interquartile range) or number (%).

| Patients (n=170) | |

|---|---|

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 28.6 (26.4, 29.9) |

| Birth Weight (grams) | 1105 (810, 1390) |

| Male Sex | 85/170 (50.0%) |

| Multiple Gestation (twin, triplet) | 47/170 (27.6%) |

|

| |

| Maternal Age (years) | 28 (23, 33) |

| Maternal Race | |

| Black/African American | 100/170 (58.8%) |

| White/Caucasian | 64/170 (37.6%) |

| Asian | 2/170 (1.2%) |

| Mixed/Other | 4/170 (2.4%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 5/170 (2.9%) |

| Highest Maternal Education | |

| Did not graduate High School | 22/165 (13.3%) |

| High School Graduate | 39/165 (23.6%) |

| Any College | 55/165 (33.3%) |

| Trade School | 13/165 (7.9%) |

| Associates Degree | 14/165 (8.5%) |

| College Graduate | 16/165 (9.7%) |

| Graduate Degree | 6/165 (3.6%) |

| Tobacco Use During Pregnancy | 26/170 (15.3%) |

| Antenatal Steroids | 158/169 (93.5%) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 23/170 (13.5%) |

|

| |

| Surfactant | 113/170 (66.5%) |

| Caffeine | 163/170 (95.9%) |

| Intraventricular Hemorrhage (Grade III/IV) | 7/169 (4.1%) |

|

| |

| Supplemental Oxygen at 1st Week Collection | 75/165 (45.5%) |

| Effective FiO2 (%) | 21 (21, 28) |

| Intubated | 47/165 (28.5%) |

| Supplemental Oxygen at 1st Month Collection | 67/159 (42.1%) |

| Effective FiO2 (%) | 21 (21, 28) |

| Intubated | 33/159 (20.8%) |

The levels of urinary oxidative biomarkers at the end of the 1st week and 1st month of age are shown in Table 2. The 1st week samples were obtained at a median (IQR) age of 7 (6, 8) days and 1st month age of 30 (29, 32) days. The percentage of samples above the limits of quantification (>LOQ) were 79.2–100% for lipids, 98.7–100% for protein, and 100% for DNA oxidation biomarkers (see Supplement). There was a significant difference in IsoFs, NeuroPs, dihomo-IsoPs, dihomo-IsoFs, and o-Tyr group medians from the 1st week and the 1st month samples. A difference between group medians at 1 week and 1 month was not detected for IsoPs, NeuroFs, m-Tyr, and the ratio of 8OHdG/2dG.

Urinary oxidative biomarkers were correlated with hypoxemia parameters in the preceding 24 hr window.17 Median (min-max range) percent-time with an SpO2 <80% was 0.2 (0–67.6) percent at 1 week and 0.8 (0–22.3) at 1 month. IH episodes occurred at a median rate of 6.0 (0–115.3) episodes per day at 1 week and 18.1 (0–296.5) at 1 month. Median IH duration was 23.8 (0–140.5) seconds at 1 week and 19.9 (0–85.4) at 1 month.

Full results of the multiple quantile regression analyses for oxidative biomarker prediction outcomes and co-variants are reported in the Supplement.

At the 1st week of age collection, after adjusting for co-variants significant relationships between hypoxemia parameters and urine lipid peroxidation and oxidized protein biomarkers were detected (Figure 2). IsoF levels were positively associated with percent-time with SpO2 <80% at the 25th (Q25) and 50th (Q50) quantiles. IsoF levels were positively associated with IH frequency at the 75th (Q75) quantile. NeuroF levels were positively associated with percent-time SpO2 <80% at Q25. Dihomo-IsoP levels were positively associated with IH duration at Q50 and negatively associated with IH frequency at Q25. Dihomo-IsoF levels were positively associated with IH frequency at Q75. Meta-Tyr levels were negatively associated to IH frequency at Q75 and IH duration at Q75. Ortho-Tyr levels were positively associated with IH duration at Q75. Significant associations were not detected between 1st week of age hypoxemia parameters and any quantile of IsoP or NeuroP levels.

Figure 2. Correlation Coefficient of 1st Week Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Hypoxemia Parameters.

Forest plots of multiple quantile regression analysis β-coefficient (dot) and 95% confidence intervals (bars) for associations between biomarker 25th (Q25), 50th (Q50), and 75th (Q75) quantiles. Key predictors are intermittent hypoxemia (IH) parameters. Models were adjusted for gestational age at birth, sex, black race, birthweight Z-score, caffeine, chorioamnionitis, day of age at collection, effective FiO2 at collection, Fenton birthweight category, maternal tobacco use, and mechanical ventilation at time of urine collection. *p<0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

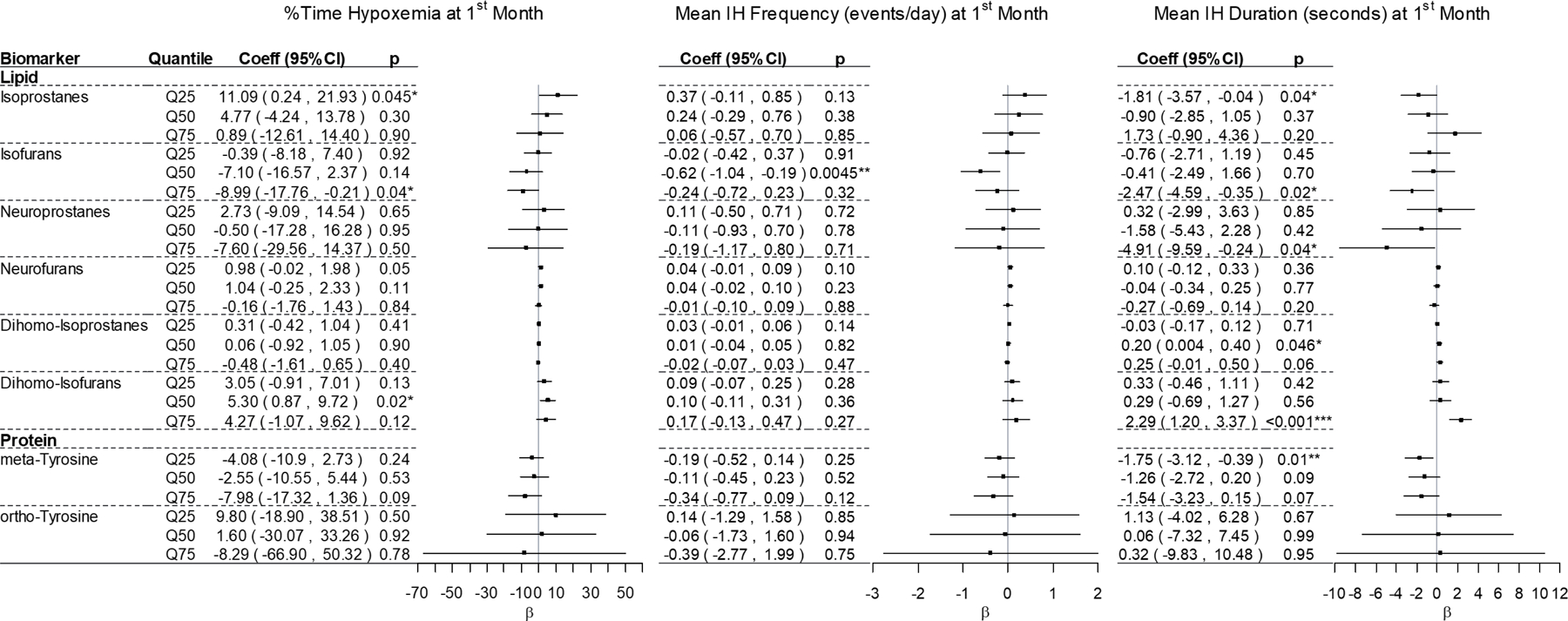

At the 1st month of age collection, after adjusting for co-variants significant relationships between hypoxemia parameters and urine lipid peroxidation and oxidized protein biomarkers were again detected (Figure 3). IsoP levels were positively associated with percent-time with SpO2 <80% at Q25. IsoP levels were negatively associated with IH duration at Q25. IsoF levels were negatively associated with percent-time with SpO2 <80% at Q75, IH frequency at Q50, and IH duration at Q75. NeuroP levels were negatively associated with IH duration at Q75. Dihomo-IsoP levels were positively associated with IH duration at Q50. Dihomo-IsoF levels were positively associated with percent-time with SpO2 <80% at Q50 and IH duration at Q75. Meta-Tyr levels were negatively associated with IH duration at Q25. Significant associations were not detected between 1st month of age hypoxemia parameters and any quantile of NeuroF or o-Tyr levels.

Figure 3. Correlation Coefficient of 1st Month Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Hypoxemia Parameters.

Forest plots of multiple quantile regression analysis β-coefficient (dot) and 95% confidence intervals (bars) for associations between biomarker 25th (Q25), 50th (Q50), and 75th (Q75) quantiles. Key predictors are intermittent hypoxemia (IH) parameters. Models were adjusted for gestational age at birth, sex, black race, birthweight Z-score, caffeine, chorioamnionitis, day of age at collection, effective FiO2 at collection, Fenton birthweight category, maternal tobacco use, and mechanical ventilation at time of urine collection. *p<0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

After adjusting for co-variants, no significant relationships between hypoxemia parameters and DNA oxidative damage to guanosine (ratio of 8OHdG:2dG) were detected at any quantile at either time-point.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of preterm neonates, hypoxemia parameters were both positively and negatively associated with urine lipid and protein biomarkers and varied by the quantile of peroxidation products and postnatal age. In this exploratory analysis, the highest quantiles (Q75) of IsoFs, dihomo-IsoFs, and o-Tyr at 1 week were positively associated with IH parameters; products that may link early oxidative injury to the reported associations of elevated IH parameters on outcomes such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, and neurodevelopmental impairments.

The temporal changes observed for urinary IsoFs decreasing over time and NeuroPs increasing over time correspond with previously reported trends during the first month of age in very low birth weight18 and first two weeks of age in moderate preterm newborns.13 We now report additionally upon postnatal alternations in dihomo-IsoPs, dihomo-IsoFs, and o-Tyr levels between the 1st week and 1st month of age in preterm infants. Of note, in an animal model of oxidative stress, lung o-Tyr levels also increase over time.21

Previous studies have shown that the percentage of recorded time with hypoxemia has been associated with late death, severe IVH, retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and neurodevelopmental disability.22–24 We observed significant positive associations with percent-time hypoxemic between 1st week IsoFs and NeuroFs and 1st month IsoPs and dihomo-IsoFs. IsoFs and NeuroFs are isomers of F2-Isoprostanes that are characterized by a substituted tetrahydrofuran ring structure as a consequence of being exposed to high oxygen concentrations.25 Kuligowski et al. have reported that elevated urine IsoFs obtained from very low birth weight newborns during the first days of life have been associated with the diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age.18 NeuroFs and dihomo-IsoFs arise from oxidative damage to DHA and adrenic acid, important structural components of the central nervous system implying neuronal oxidative damage.5,26 Matthews et al. have reported that increasing serum IsoPs during the first month of age predicted respiratory morbidity and neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants.27 Additionally, at 1 month we detected an unexpected negative relation between percent time hypoxemic and Q75 IsoFs. Studies in cyanotic heart disease indicate that in conditions of hypoxemia a metabolic switch to activate the pentose pathway occurs and provided the glutathione redox cycle with electrons needed to rebuild reduced glutathione and thus counteract oxidative stress28 which might in-part explain the changes in IsoF relationships between 1st week and 1st month samples. Prolonged hypoxemia and/or the use of high FiO2 upon stabilization of a hypoxic event can be extremely damaging for oxy-dependent tissues such as the central nervous system, myocardium, retina and tissue that directly receive the impact of oxygen radicals as is the case of the lung. Further correlations with these oxidative biomarkers on neural and pulmonary tissues may provide mechanistic insight into the observations that neonates with increased percent-time hypoxemic are at higher risk for these adverse infant and childhood outcomes.

While percent-time hypoxemic accounts for all time with SpO2 <80%, IH counts capture hypoxemic events and subsequent re-oxygenation. Di Fiore et al. have shown that the frequency of daily IH events in extremely preterm neonates increases dramatically during the first month of age.8 Previous studies have shown that increased IH frequency at a given postnatal age and the trajectory of daily IH counts were associated with development of retinopathy of prematurity requiring laser surgery, development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia with associated neurodevelopmental impairment, and childhood wheezing.16,23,24,29,30 Of note, these studies have used various thresholds for defining IH such that absolute event counts may not be directly comparable to this study. We observed significant positive associations between 1st week IH frequency with IsoFs and dihomo-IsoFs. As noted, Kuligowski et al. reported that elevated IsoFs during the first few days after birth were associated with later diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, however this relationship was not detected at one month of age18 indicating that early, more so than later, oxidative stress may cause or predict risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Pro-oxidant aggression in the first week is likely related to oxygen supplementation in the delivery room and the NICU due to respiratory immaturity.2 At this stage, the antioxidant defense system, including non-enzymatic antioxidants is at its most immature stage with a predominance of IsoFs reflecting IsoPs alteration by the action of oxygen.4 At one month infants are in a more stable metabolic and anti-oxidant situation,31 IsoFs have been shown to decline by a month of age,18 whereas IH event frequency peaks at this time8 so interpretation of a negative β-coefficient correlation at 1 month for IsoFs is complex. Newborn and fetal animal models indicate that IH increases cerebral superoxide,32 induces oxidative stress in the cortex and brainstem,33,34 and adversely effects myelination.35,36 In our study, 1st week IH frequency was associated with increased dihomo-IsoFs. In hyperoxic conditions, dihomo-IsoFs are the result of peroxidation of adrenic acid, found in the retina and brain white matter.6,26 Conversely, the lowest quantile dihomo-IsoPs were negatively associated with 1st week IH frequency. Meta-Tyr was negatively correlated with IH frequency such that IH frequency predicted a lower 1st week m-Tyr level indicating that IH events may be unlikely to oxidize ubiquitous phenylalanine resulting in m-Tyr formation. Additionally, lipids are more sensitive to oxidative stress because ROS trigger a chain reaction in which free radicals beget free radicals and continue damaging lipid structure altering function and structure of cell membranes.

Previous studies have reported that the average duration of an IH event was significantly longer in preterm infants that developed retinopathy of prematurity37 and bronchopulmonary dysplasia.30 In secondary analyses of the Canadian Oxygen Trial, only IH events greater than 1 minute in duration increased the risk of late death or disability.22 We observed significant positive associations between 1st week IH duration with dihomo-IsoP and o-Tyr levels and 1st month dihomo-IsoPs and dihomo-IsoFs. We also detected significant negative associations between 1st week IH duration with m-Tyr and 1st month IsoPs, IsoFs, NeuroPs, and m-Tyr. We again observe that adrenic acid peroxidation to form dihomo-IsoPs and dihomo-IsoFs was positively associated with a hypoxemia parameter which has been implicated in retinopathy of prematurity and poor neurodevelopmental outcomes. We observed that IH duration and oxidation of phenylalanine was positively correlated with 1st week o-Tyr and negatively correlated with 1st week and 1st month m-Tyr products. In our study, urine o-Tyr was more abundant than m-Tyr indicating that oxidation of phenylalanine may favor the formation of o-Tyr and might explain the opposing directions of correlations. It has been speculated that due to phenylalanine’s hydrophobic benzyl ring the amino acid is positioned in such a way that the ortho positions are more readily accessible than the meta positions for oxidation events.38 The negative associations observed at 1 month between IH duration and IsoPs, IsoFs, and NeuroPs were not anticipated and might indicate differential maturation of antioxidant defenses and establishment of enteral feedings.31 Antioxidant activity increases exponentially in term babies in the first days after birth.39 However, Asikainen et al. examined serial lung specimens throughout gestation and found that antioxidant manganese superoxide dismutase protein does not increase during lung development and does not appear to increase significantly in preterm infants in response to increased ROS exposure40 which again may explain the different directions of associations at 1 month. These differing 1st week and 1st month associations may also be the result of our IH definitions or due to additional confounders relevant to IH duration at 1 month of age that were not accounted for in the adjusted model.

A limitation of any observational study is that causation cannot be established, however animal studies have shown inducing IH results in increased ROS32,41–43 and decreased antioxidants.33,34,44 While we attempted to adjust for numerous potential co-variants to describe the relationship between hypoxemia events and oxidative stress biomarkers; co-morbidities and other confounders may contribute to oxidative stress and/or hypoxemia events. Not all IH parameters induce oxidative stress, just as not all IH have been linked to adverse outcomes. Specifically in other cohort studies, events less than 1 minute in duration did not predict late death or disability22 and events clustered within 1 minute apart or occurring greater than 20 minutes apart were not associated with development of retinopathy of prematurity37 or bronchopulmonary dysplasia.30 We used thresholds for IH that have been commonly described in the outcomes literature, however as there are no standard IH definitions, different criteria may give different results. Urine creatinine was used for normalization of biomarker concentrations as previously reported,13 however there are limitations to the use and interpretations of creatinine, as it can be affected by factors such as muscle mass and renal function which can vary among preterm infants. As an exploratory investigation of these complex data, the quantile regression models showed not all quantiles of oxidative biomarkers were significant and models did not include corrections for multiple comparisons. Multiple quantile regression analyses were necessary because they do not presume normal distribution and are robust to outliers and skew in data, thus can model the full distribution of the outcome variable, not just the mean. These exploratory analyses show various relationships between IH and markers of oxidative damage to lipids and proteins. Cautious interpretation of results, particularly at one month after birth, are warrented which may reflect a more mature antioxidant defense system and exogenous antioxidant intake after establishing enteral feeds.31

In conclusion, preterm neonates experience oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA that can be quantified from noninvasive urine samples. We set out to investigate if these products of oxidative stress were associated with preceding IH. After adjusting for multiple co-variants, significant associations with hypoxemia event parameters were found for lipid and protein peroxidation products, however the pattern varies by marker quantile and IH parameter. Both positive and negative associations were detected depending on the parameter and oxidative biomarker such that the complex associations are likely multifactorial. These data could be useful in designing future laboratory and clinical studies to better understand mechanisms and potential relationships to disease. We speculate initiation of an oxidative cascade by 1st week IH may be one pathway implicated in poor outcomes. Early IsoF levels may be of particular interest based on the biological plausibility and early IH findings of this study. Urinary oxidative stress biomarkers and IH patterns may provide new insight on disease pathogenesis and early identification of high-risk neonates.

Supplementary Material

Impact:

Hypoxemia events are frequent in preterm infants and are associated with poor outcomes

The mechanisms by which hypoxemia events result in adverse neural and respiratory outcomes may include oxidative stress to lipids, proteins, and DNA

This study begins to explore associations between hypoxemia parameters and products of oxidative stress in preterm infants

Oxidative stress biomarkers may assist in identifying high-risk neonates

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the neonatal research staff, specifically Advanced Clinical Research Nurse Ms. Arlene Zadell, and our scientific collaborators at Institut des Biomolecules Max Mousseron, UMR 5247 CNRS, ENSCM, Universite de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, specifically Camille Oger, Jean-Marie Galano, and Thierry Durand.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [U01HL133643 and U01HL133708, Co-PIs AMH and RJM; and UL1TR002548, PI Grace A McComsey].

ASI acknowledges the support of RETICS from the Health Research Institute Carlos III, Spain (ISCIII) - European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) [RD16/0022/001], the PFIS grant from ISCIII (Ministry of Science and Innovation) [FI16/00380], and Margarita Salas grant [UP2021-044-MS21-084] from the Ministry of Universities of the Government of Spain, financed by the European Union, NextGeneration EU.

MV acknowledges the support of RETICS [PN 2018-2021 (Spain)], ISCIII, Spain - Sub-Directorate General for Research Assessment and Promotion and FEDER [RD16/0022], and ISCIII (Ministry of Science and Innovation) [PI20/00964].

JK acknowledges the support of ISCIII, Spain and co-funded by the European Union [CPII21/00003].

Footnotes

Competing Interests

Authors have no potential conflicts of interest to report.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Consent Statement

Parent or guardian provided written informed consent for their child’s participation in this study. Oversight was provided by a local institutional review board and observational and safety monitoring board appointed by the NHLBI.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Berkelhamer SK & Farrow KN Developmental Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes and Their Impact on Neonatal Lung Disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling 21, 1837–1848 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vento M et al. Preterm Resuscitation with Low Oxygen Causes Less Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Chronic Lung Disease. Pediatrics 124, e439–449 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saugstad OD, Sejersted Y, Solberg R, Wollen EJ & Bjoras M Oxygenation of the Newborn: A Molecular Approach. Neonatology 101, 315–325 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrante G, Carota G, Li Volti G & Giuffre M Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress for Neonatal Lung Disease. Frontiers in pediatrics 9, 618867 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solberg R et al. Resuscitation with Supplementary Oxygen Induces Oxidative Injury in the Cerebral Cortex. Free Radic Biol Med 53, 1061–1067 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Illana A et al. Adrenic Acid Non-Enzymatic Peroxidation Products in Biofluids of Moderate Preterm Infants. Free Radic Biol Med (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuligowski J et al. Assessment of Oxidative Damage to Proteins and DNA in Urine of Newborn Infants by a Validated Uplc-Ms/Ms Approach. PLoS One 9, e93703 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Fiore JM et al. Prematurity and Postnatal Alterations in Intermittent Hypoxaemia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Fiore JM, MacFarlane PM & Martin RJ Intermittent Hypoxemia in Preterm Infants. Clin Perinatol 46, 553–565 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Fiore JM & Raffay TM The Relationship between Intermittent Hypoxemia Events and Neural Outcomes in Neonates. Exp Neurol 342, 113753 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartman CM, Awari DW, Pabelick CM & Prakash YS Intermittent Hypoxia-Hyperoxia and Oxidative Stress in Developing Human Airway Smooth Muscle. Antioxidants 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Fiore JM & Vento M Intermittent Hypoxemia and Oxidative Stress in Preterm Infants. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology 266, 121–129 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah VP et al. The Relationship between Oxidative Stress, Intermittent Hypoxemia, and Hospital Duration in Moderate Preterm Infants. Neonatology 117, 577–583 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennery PA et al. Pre-Vent: The Prematurity-Related Ventilatory Control Study. Pediatr Res 85, 769–776 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supplemental Therapeutic Oxygen for Prethreshold Retinopathy of Prematurity (Stop-Rop), a Randomized, Controlled Trial. I: Primary Outcomes. Pediatrics 105, 295–310 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Fiore JM et al. A Higher Incidence of Intermittent Hypoxemic Episodes Is Associated with Severe Retinopathy of Prematurity. J Pediatr 157, 69–73 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuligowski J et al. Analysis of Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Extremely Low Gestational Age Neonate Urines by Uplc-Ms/Ms. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 406, 4345–4356 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuligowski J et al. Urinary Lipid Peroxidation Byproducts: Are They Relevant for Predicting Neonatal Morbidity in Preterm Infants? Antioxidants & redox signaling 23, 178–184 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez-Illana A et al. Novel Free-Radical Mediated Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Newborn Plasma. Analytica chimica acta 996, 88–97 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galarza CE, Lachos VH & Bandyopadhyay D Quantile Regression in Linear Mixed Models: A Stochastic Approximation Em Approach. Statistics and its interface 10, 471–482 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly FJ & Lubec G Hyperoxic Injury of Immature Guinea Pig Lung Is Mediated Via Hydroxyl Radicals. Pediatr Res 38, 286–291 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poets CF et al. Association between Intermittent Hypoxemia or Bradycardia and Late Death or Disability in Extremely Preterm Infants. Jama 314, 595–603 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen EA et al. Association between Intermittent Hypoxemia and Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 204, 1192–1199 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairchild KD, Nagraj VP, Sullivan BA, Moorman JR & Lake DE Oxygen Desaturations in the Early Neonatal Period Predict Development of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Pediatr Res 85, 987–993 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fessel JP, Porter NA, Moore KP, Sheller JR & Roberts LJ 2nd. Discovery of Lipid Peroxidation Products Formed in Vivo with a Substituted Tetrahydrofuran Ring (Isofurans) That Are Favored by Increased Oxygen Tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 16713–16718 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bultel-Poncé V, Durand T, Guy A, Oger C & Galano J-M Non Enzymatic Metabolites of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Friend or Foe. OCL 23, D118 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews MA et al. Increasing F2-Isoprostanes in the First Month after Birth Predicts Poor Respiratory and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Very Preterm Infants. J Perinatol 36, 779–783 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pineiro-Ramos JD et al. A Reductive Metabolic Switch Protects Infants with Transposition of Great Arteries Undergoing Atrial Septostomy against Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Fiore JM et al. Early Inspired Oxygen and Intermittent Hypoxemic Events in Extremely Premature Infants Are Associated with Asthma Medication Use at 2 Years of Age. J Perinatol 39, 203–211 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raffay TM et al. Neonatal Intermittent Hypoxemia Events Are Associated with Diagnosis of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia at 36 Weeks Postmenstrual Age. Pediatr Res 85, 318–323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledo A et al. Human Milk Enhances Antioxidant Defenses against Hydroxyl Radical Aggression in Preterm Infants. The American journal of clinical nutrition 89, 210–215 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabian RH, Perez-Polo JR & Kent TA Extracellular Superoxide Concentration Increases Following Cerebral Hypoxia but Does Not Affect Cerebral Blood Flow. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience 22, 225–230 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laouafa S et al. Erythropoietin and Caffeine Exert Similar Protective Impact against Neonatal Intermittent Hypoxia: Apnea of Prematurity and Sex Dimorphism. Exp Neurol 320, 112985 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan S et al. Increased Injury Following Intermittent Fetal Hypoxia-Reoxygenation Is Associated with Increased Free Radical Production in Fetal Rabbit Brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58, 972–981 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manlapaz-Mann A et al. Effects of Omega 3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Antioxidants, and/or Non-Steroidal Inflammatory Drugs in the Brain of Neonatal Rats Exposed to Intermittent Hypoxia. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience 81, 448–460 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darnall RA et al. Early Postnatal Exposure to Intermittent Hypoxia in Rodents Is Proinflammatory, Impairs White Matter Integrity, and Alters Brain Metabolism. Pediatr Res 82, 164–172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Fiore JM et al. The Relationship between Patterns of Intermittent Hypoxia and Retinopathy of Prematurity in Preterm Infants. Pediatr Res 72, 606–612 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ipson BR & Fisher AL Roles of the Tyrosine Isomers Meta-Tyrosine and Ortho-Tyrosine in Oxidative Stress. Ageing research reviews 27, 93–107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilinska M, Borszewska-Kornacka MK, Niemiec T & Jakiel G Oxidative Stress and Total Antioxidant Status in Term Newborns and Their Mothers. Annals of agricultural and environmental medicine : AAEM 22, 736–740 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asikainen TM, Heikkila P, Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Kinnula VL & Raivio KO Cell-Specific Expression of Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Protein in the Lungs of Patients with Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Chronic Lung Disease, or Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension. Pediatric pulmonology 32, 193–200 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan G, Nanduri J, Khan S, Semenza GL & Prabhakar NR Induction of Hif-1alpha Expression by Intermittent Hypoxia: Involvement of Nadph Oxidase, Ca2+ Signaling, Prolyl Hydroxylases, and Mtor. J Cell Physiol 217, 674–685 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Agrosa C et al. Comparison of Coenzyme Q10 or Fish Oil for Prevention of Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Oxidative Injury in Neonatal Rat Lungs. Respir Res 22, 196 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beharry KD et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Accumulation in the Choroid During Intermittent Hypoxia Increases Risk of Severe Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy in Neonatal Rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 7644–7657 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nanduri J et al. Intermittent Hypoxia Degrades Hif-2alpha Via Calpains Resulting in Oxidative Stress: Implications for Recurrent Apnea-Induced Morbidities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 1199–1204 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.