Abstract

Background

To mitigate the growing burden of non-communicable diseases, doctors training to become paediatricians should be equipped with concepts and knowledge regarding Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD).

Methods

We assessed the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of medical officers, resident physicians, as well as junior and senior residents practising in the paediatric department of a tertiary women’s and children’s hospital. This was done through a cross-sectional online survey, with questions developed after focused group discussions with domain experts, and responses based on a 5-point Likert scale.

Results

A total of 95 physicians met the inclusion criteria, grouped into Medical Officers (MOs) and Registrars (REGs), and we received a 100% response rate. Results showed that few physicians (n = 22, 23.2%) knew the term DOHaD, and majority rated their colleagues to be inadequately informed (n = 84, 88.4%). Among the physicians, one third (n = 32, 33.7%) were not confident in their ability to counsel patients about initiating healthy feeding practices to prevent future metabolic diseases in their children. However, there was a readiness to be better equipped with DOHaD principles and knowledge, and 95.8% (n = 91) strongly acknowledged the physician’s responsibility to optimise early life determinants of cardiometabolic health.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings suggest a poor translation of DOHaD concepts, indicating that bridging the gap between DOHaD research knowledge and clinical application represents an unmet need. These principles should be inculcated early in the professional training of all healthcare providers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06036-3.

Keywords: Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, Medical education, Population health, DOHaD

Introduction

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) conceptualises that environmental and maternal factors can shape the development and health of individuals, progressing from the early embryonic period to childhood and beyond [1, 2]. It is believed that some developmental processes can affect an individual’s susceptibility and resistance to diseases, including chronic conditions [3], with epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation in genes related to metabolism and relevant pathways that have been associated with diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity [4]. Given the increasing burden of obesity [5] and related non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease globally [6], efforts to tackle this epidemic have been gaining traction [7]. However, the translation of DOHaD knowledge into healthcare is lacking globally [8], restricting its potential clinical impacts from preconception to postnatal care in the first 1000 days of a child’s life [9]. Thus, efforts to assess the prevailing knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians are crucial, in order to identify barriers and individualize interventions to increase uptake of DOHaD practice.

Locally in Singapore, the government first launched a nation-wide initiative to wage war against diabetes mellitus [10], followed by the launch of the Healthier SG Strategy [11]. Multi-pronged measures including primary and secondary preventive methods were largely aimed at adopting a healthy lifestyle with the emphasis on going beyond healthcare to health [12]. Subsequently, a similar approach has been developed in improving preventive efforts to promote maternal and child health in Singapore, underpinning the importance of DOHaD perspectives in modern day practice [13]. However, while such models are being developed to advance care for maternal and child health at the policy level, there has been a paucity of formal studies conducted in Singapore to assess the knowledge and opinions regarding DOHaD among physicians involved in maternal and child health. A recent study by Ku et al. in Singapore found poor translation of DOHaD awareness into clinical practice among obstetrics and gynaecology residents, paediatric residents, and medical students [14]. However, given a small representation of paediatric residents (9 out of 117 respondents) [14], generalizability and applicability of the results towards identifying gaps in post-graduate medical education and paediatric residency training may be limited. Furthermore, paediatricians play a vital role in integrating, shaping, and building the foundation for maternal and child health, together with their obstetric colleagues [15]. Paediatric care has far-reaching benefits and consequences on health into adulthood. They must therefore be armed with the necessary knowledge and skills early in their training, with DOHaD principles ingrained and translated into clinical practice.

Therefore, we aimed to perform a study targeting physicians who underwent training in the paediatric department, to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards DOHaD. The overarching goal is to identify potential areas for improvement in our current training system for our next generation of doctors, and to develop a more robust system to improve translation of DOHaD concepts into clinical practice, thus enhancing maternal and child health as a cohesive unit in a tertiary women’s and children’s hospital. Moving forward, this can also encompass primary care, potentially providing seamless care across the health system.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey among medical officers and registrars from the department of paediatrics in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH), Singapore, from June to August 2022. Inclusion criteria were medical officers who were doing their general paediatric posting during the study period with at least a year of clinical experience, junior residents, senior residents, and resident physicians. House officers (HOs) and consultants (Cs) were excluded from the survey. Medical officers doing their general paediatric posting and junior residents were grouped as “Medical Officers” (MOs); senior residents and resident physicians were grouped as “Registrars” (REGs). Information including their age, sex, year of graduation, and length of service was recorded.

Items of our questionnaire were developed after focused group discussions. Content validity was determined by domain experts comprising obstetricians and gynaecologists (O&G), paediatricians and medical students. Development was in accordance to existing KAP guides [16]. After its use to investigate KAP among medical students, O&G residents, and paediatric residents [14], some questions were revised to increase their applicability and relevance to daily paediatric practice. Supplementary Figure S1 shows a sample of the questionnaire used.

The first section of the questionnaire was on Knowledge, focusing on physicians’ awareness of the definitions and clinical impacts of DOHaD concepts on a child’s lifelong metabolic health. There were 15 questions in this section, evaluating understanding of how preconception health, in-utero conditions, and the first two years of a child’s life can influence his or her lifelong cardiometabolic outcomes. They were also asked to appraise their own level of knowledge, as well as that of their colleagues. Their responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, ‘not’ to ‘very’, and ‘null’ to ‘excellent’. Higher scores within this section indicate a better understanding of the principles of DOHaD and their clinical relevance.

The attitudes and opinions of the physicians on the significance and long-term clinical implications of DOHaD were assessed in the Attitudes section. Similarly, nine questions within this section were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Questions were posed on how much the physician prioritized the pivotal role of infant growth assessment, including the critical role of empowering parents, with proper counselling and guidance. The higher the scores, the stronger the degree of belief and ownership regarding the importance of counselling patients’ parents about DOHaD concepts, given its long-term repercussions on cardiovascular diseases.

The translation of DOHaD theories into a physician’s clinical practice was evaluated in the Practice section. Here, five questions clarified whether a physician’s management of a child incorporated knowledge about DOHaD, such as the importance of optimal weaning and nutrition practices for children as well as holistic growth assessment. A 5-point Likert scale was used, from ‘never’ to ‘always’, reflecting the translation of DOHaD concepts into clinical management.

The questionnaire was administered electronically via the FormSG web-based platform [17], a secure digital government form.

Sample size calculation

There was a total of 95 medical officers, junior residents, resident physicians, and senior residents in the institution. Using Slovin’s formula, with a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error, a minimum sample size of 77 was required.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 25 and the R programming language. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To gain a holistic view of the performances in each section (Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice), the mean scores for each KAP domain were calculated. Independent t-tests were conducted to determine the differences in KAP mean scores between junior and senior doctors. Chi-square statistics were used to compare sex differences between the groups. The internal consistency for each section was determined by Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, with an acceptable value taken to be 0.70 and higher [18].

Results

There was a total of 95 physicians who met inclusion criteria, comprising MOs (n = 52) and REGs (n = 43). There was a 100% response rate, and their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The respondents were predominantly female (n = 68, 71.6%). On average, MOs and REGs were 4 and 8 years post-graduation respectively, with a corresponding age gap of almost 4 years. Proportion of responses and their mean scores of selected questions for discussion are shown in Table 2. These questions were selected from their respective sections (Knowledge, Attitudes, or Practices) because (i) the overall mean scores were among the lowest, or (ii) the highest overall percentage of responses indicating “Agree”, “Frequently”, or “Yes”. The complete breakdown of the responses of each individual question is shown in Figure S2 (MOs) and Figure S3 (REGs).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of medical officers and registrars in the paediatric department who responded to the DOHaD questionnaire

| Overall | Medical Officers | Registrars | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Doctors | 95 | 52 | 43 | |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 30.72 (4.02) | 28.98 (3.52) | 32.88 (3.55) | < 0.001 |

| Length of Service, Mean (SD) | 6.02 (3.06) | 4.38 (2.56) | 8.00 (2.36) | < 0.001 |

| Job Position, n (%) | ||||

| Medical Officer (Junior Resident) | 25 (26.3) | 25 (48.1) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Medical Officer (Non-Resident) | 27 (28.4) | 27 (51.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Senior Resident | 42 (44.2) | 0 (0.0) | 42 (97.7) | |

| Resident Physician | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 68 (71.6) | 35 (67.3) | 33 (76.7) | 0.432 |

| Male | 27 (28.4) | 17 (32.7) | 10 (23.3) | |

P-values for continuous variables were calculated using the independent t-test, p-values for categorical variables were calculated using the chi-squared test. Variables are presented in n (%), unless, otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; n, number of respondents

Table 2.

Selected questions with their mean scores and breakdown of responses in knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to DOHaD among junior doctors and senior paediatric trainees in the paediatric department

| KNOWLEDGE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Medical Officers | Registrars | Overall | p-value |

| I know the term ‘Developmental Origins of Health and Disease’ (DOHaD). | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 2.40 (1.12) | 2.91 (1.13) | 2.63 (1.15) | 0.033 |

| Disagree, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 29 (55.8) | 14 (32.6) | 43 (45.3) | 0.071 |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 14 (26.9) | 16 (37.2) | 30 (31.6) | |

| Agree, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 9 (17.3) | 13 (30.2) | 22 (23.2) | |

| How would you evaluate your knowledge about DOHaD? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 2.25 (0.90) | 3.00 (0.82) | 2.59 (0.94) | < 0.001 |

| Null to poor, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 29 (55.8) | 9 (20.9) | 38 (40.0) | 0.001 |

| Average, n (%) (Score 3) | 20 (38.5) | 24 (55.8) | 44 (46.3) | |

| Good to excellent, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 3 (5.8) | 10 (23.3) | 13 (13.7) | |

| How well do you think your colleagues, or other healthcare individuals in a similar position as you, are informed about DOHaD? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 2.69 (0.70) | 2.98 (0.67) | 2.82 (0.70) | 0.048 |

| Null to poor, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 15 (28.8) | 8 (18.6) | 23 (24.2) | 0.111 |

| Average, n (%) (Score 3) | 34 (65.4) | 27 (62.8) | 61 (64.2) | |

| Good to excellent, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 3 (5.8) | 8 (18.6) | 11 (11.6) | |

| A woman’s health and wellbeing during pregnancy affects her grandchildren’s risk of developing metabolic diseases later in life. | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 3.54 (0.87) | 3.86 (0.89) | 3.68 (0.89) | 0.079 |

| Disagree, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 3 (5.8) | 3 (7.0) | 6 (6.3) | 0.078 |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 25 (48.1) | 11 (25.6) | 36 (37.9) | |

| Agree, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 24 (46.2) | 29 (67.4) | 53 (55.8) | |

| Would you be interested to receive training in the topics related to DOHaD? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 4.38 (0.75) | 4.12 (0.96) | 4.26 (0.85) | 0.128 |

| No, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (7.0) | 4 (4.2) | 0.150 |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 2 (3.8) | 5 (11.6) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Yes, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 49 (94.2) | 35 (81.4) | 84 (88.4) | |

| ATTITUDES | ||||

| Question | Medical Officers | Registrars | Overall | p-value |

| I am confident in counselling patients regarding prevention of future metabolic disease in the child by initiating healthy eating practices from the start of weaning. | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 3.63 (0.79) | 3.86 (0.83) | 3.74 (0.81) | 0.180 |

| Disagree, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 3 (5.8) | 3 (7.0) | 6 (6.3) | 0.441 |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 17 (32.7) | 9 (20.9) | 26 (27.4) | |

| Agree, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 32 (61.5) | 31 (72.1) | 63 (66.3) | |

| The concept of early life effects on future child health development is relevant in my professional practice. | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 4.63 (0.69) | 4.65 (0.48) | 4.64 (0.60) | 0.894 |

| Disagree, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | NA |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Agree, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 51 (98.1) | 43 (100.0) | 94 (98.9) | |

| It is my responsibility to educate parents regarding the importance of early childhood nutrition on subsequent child health. | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 4.35 (0.62) | 4.58 (0.59) | 4.45 (0.61) | 0.063 |

| Disagree, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.501 |

| Not Sure, n (%) (Score 3) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (4.7) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Agree, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 50 (96.2) | 41 (95.3) | 91 (95.8) | |

| PRACTICES | ||||

| Question | Medical Officers | Registrars | Overall | p-value |

| Have you ever counselled parents about the appropriate weaning and nutrition practices for their child? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 3.96 (0.77) | 4.33 (0.47) | 4.13 (0.67) | 0.008 |

| Infrequently, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.016 |

| Sometimes, n (%) (Score 3) | 7 (13.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Frequently, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 43 (82.7) | 43 (100.0) | 86 (90.5) | |

| Have you ever provided patients with healthy lifestyle advice if he/she is underweight or overweight/ obese? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 4.40 (0.80) | 4.67 (0.47) | 4.53 (0.68) | 0.044 |

| Infrequently, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.278 |

| Sometimes, n (%) (Score 3) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Frequently, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 49 (94.2) | 43 (100.0) | 92 (96.8) | |

| Have you ever counselled parents about how their child’s health during the first 2 years of life can affect their future risk for obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adulthood? | ||||

| Mean Score (SD) | 3.35 (1.06) | 3.44 (1.12) | 3.39 (1.08) | 0.671 |

| Infrequently, n (%) (Score 1–2) | 13 (25.0) | 9 (20.9) | 22 (23.2) | 0.495 |

| Sometimes, n (%) (Score 3) | 15 (28.8) | 9 (20.9) | 24 (25.3) | |

| Frequently, n (%) (Score 4–5) | 24 (46.2) | 25 (58.1) | 49 (51.6) | |

P-values for continuous variables were calculated using the independent t-test, p-values for categorical variables were calculated using the chi-squared test. Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; n, number of respondents. These questions were selected from their respective sections because (i) overall mean scores were among the lowest, or (ii) highest overall percentage of “Agree”, “Frequently”, or “Yes”

Knowledge

Few physicians (n = 22, 23.2%) knew the term ‘DOHaD’. Majority assessed their knowledge about DOHaD to be poor, with only 13.7% (n = 13) rating their conceptual understanding as ‘good’ and ‘excellent’. In addition, they generally rated their colleagues to be inadequately informed, as 88.4% (n = 84) felt that their peers were not familiar with DOHaD. Although the majority demonstrated a grasp of how maternal well-being preconception and during pregnancy could affect the metabolic health of their children, they were unaware of the potential impact on the risk of non-communicable diseases of future grandchildren, with 44.2% (n = 42) either unsure or disagreeing with transgenerational metabolic health influences. Majority were interested to have a deeper understanding of the early determinants of non-communicable diseases, with 88.4% (n = 84) interested to receive training in topics related to DOHaD.

Awareness of the term DOHaD together with self and peer appraisal of knowledge regarding its concepts corresponded with seniority, as REGs had higher mean scores in the relevant questions in comparison with their junior colleagues (p = 0.016).

Attitudes

One-third of physicians (n = 32, 33.7%) were not confident in their abilities to counsel patients regarding the prevention of future metabolic diseases in children by initiating healthy eating practices from the start of weaning. On the other hand, they generally felt strongly (n = 91, 95.8%) about the physician’s responsibility in anticipatory guidance and health promotion regarding early childhood nutrition and eating habits, and the importance of holistic growth assessment during the first 2 years of life on the outcomes of lifelong metabolic health. They also recognized the significance of DOHaD concepts in clinical practice (n = 94, 98.9%). The responses were similar between the senior (REGs) and junior ranks of physicians (MOs) (p = 0.214).

Practices

The MOs and REGs had generally integrated some elements of the DOHaD principles into their practice, counselling parents about the appropriate weaning and nutrition practices for their children (n = 86, 90.5%), providing them with lifestyle advice if the child was under or overweight (n = 92, 96.8%), and all of them have made onward referrals to a dietician if there were concerns about inadequate nutritional intake. Majority also understood the importance of evaluating weight in relation to length (n = 92, 96.8%). However, a significant proportion did not emphasize the link between wellbeing during the first 2 years of life, and lifelong risk of non-communicable diseases (n = 46, 48.5%).

The REGs reported providing counselling and advice on healthy lifestyles, feeding and nutritional habits for children to a greater extent than their junior colleagues (p = 0.008).

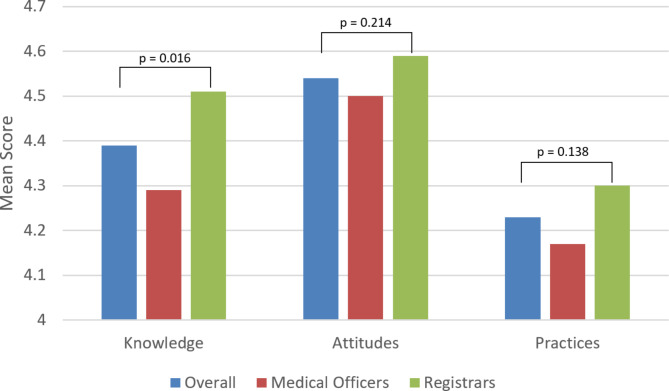

The REGs also had a higher mean Knowledge score of 4.51 (see Fig. 1) as compared to their junior colleagues at 4.29 (p = 0.016). Although there were also correspondingly higher scores in Attitudes (p = 0.214) and Practices (p = 0.138), these were not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores in Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices related to DOHaD among Medical Officers and Registrars in the paediatric department, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore. P-values for continuous variables were determined from the independent t-test

Internal consistency and reliability were good in the Knowledge and Attitudes sections, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.79 and 0.75 respectively, but it was 0.52 for the Practices section.

Discussion

Key findings

While good practices were demonstrated among REGs, self-assessed knowledge of the DOHaD principles in both groups were shown to be generally poor. This suggests an uncertainty regarding the clinical translation of DOHaD concepts into practice among physicians. Nevertheless, both groups expressed their interest in being properly equipped by learning more about DOHaD.

Low DOHaD literacy among paediatric physicians

Our study showed that REGs possessed greater self-assessed knowledge of DOHaD, compared to MOs. This is expected, given that REGs have likely received a longer duration of training in the field of paediatrics and may potentially have been more exposed to relevant concepts. However, self-assessed knowledge of DOHaD in both groups remained poor, which is consistent with a Canadian study that reflected a general lack of knowledge in DOHaD among various healthcare providers [9]. Our results suggest that there may be insufficient formal training or exposure to DOHaD within the current training of paediatric physicians. These findings are similar to another qualitative study conducted in Japan and New Zealand, which showed poor awareness of DOHaD concepts among university healthcare students despite having prior exposure, indicating that current efforts to inculcate DOHaD principles and practices through medical education may be inadequate [19]. Given the rising prominence of DOHaD [20] and its role in targeted interventions to reduce the risks of developing non-communicable diseases, more must be done to improve the literacy of DOHaD among physicians. By applying DOHaD principles, physicians can provide tailored guidance and counselling on childhood nutrition and lifestyle behaviours, especially to caregivers of children at risk of poor metabolic health. This approach not only facilitates identifying and managing high-risk groups, but also enhances downstream clinical management, potentially leading to better long-term health outcomes.

Uncertainty regarding clinical translation of DOHaD concepts

Interestingly, despite the poor self-assessment of knowledge, our study has shown that REGs have good practices, including providing appropriate nutrition and healthy lifestyle advice. We postulate three contributing factors to account for this. Firstly, it is possible that there is an under-reporting of self-assessed knowledge among the physicians about DOHaD, which may be assessed through on-site observations and interviews in future studies. Secondly, the practices performed may have been perceived to be ideal by physicians, but this may not be objectively true on the ground. The relevant concepts and latest evidence surrounding the early determinants of metabolic diseases may not have been sufficiently translated into clinical practice, a widely recognized occurrence [9, 21]. Lastly, it is plausible that while physicians may seem well-versed in such practices, they could have been influenced by other aspects of their training within paediatric medicine, such as observational and experience-based learning [22], rather than being firmly grounded using the DOHaD principles and thereafter applying them to their clinical practice. Our study thus indicates that more needs to be done to understand the association between the physicians’ knowledge and practice of DOHaD, including the knowledge barriers faced.

Expression of interest in being more well-equipped

Paediatric physicians, both junior and senior alike, expressed their interest in being properly equipped and aware of the DOHaD concepts through formal training. They recognized the relevance and importance to their practice in health promotion efforts [23] to positively influence the risk of developing non-communicable diseases during the first 2 years of a child’s life. In addition, they conveyed feeling a sense of duty and responsibility to be the ones providing counselling and anticipatory guidance regarding this, given that they are the first point of contact whenever a child comes into their clinic for well-baby visits, or opportunistically during consultations for other medical reasons. This is inherent to being a paediatrician, serving as an advocate holistically for the child’s health and wellbeing [24–26].

Recommendations

Our findings demonstrated poor knowledge about DOHaD concepts in physicians (MOs and REGs), concurring with another local DOHaD KAP study by Ku et al. [14]. However, the responses from this study are more representative of the needs from a paediatric postgraduate medical education perspective. The tailored questionnaire used in this study was also more applicable and reflective of DOHaD-related practices amongst paediatric physicians, including the uncertainty regarding clinical translation of relevant concepts. This fosters a stronger push towards bridging the gap between DOHaD research knowledge and clinical applicability.

To our knowledge, there are no programmes dedicated to physicians regarding the education and integration of DOHaD concepts from bench to bedside in Singapore. This is not unique to Singapore, as barriers to clinical translation and knowledge acquisition among healthcare providers, including the lack of practice guidelines, have been similarly identified in other countries such as Canada [9]. Till date, current literature also revealed that much international efforts for DOHaD knowledge translation have been focused on adolescents and university students [8, 21]. With these in mind, we recommend improving knowledge translation efforts locally through a multi-pronged approach: (i) restructuring formal undergraduate medical education and post-graduate training, (ii) publishing clinical practice guidelines which integrate DOHaD principles, and (iii) improving outreach and health promotion efforts within the community.

DOHaD concepts should be incorporated into the curriculum of medical education, starting early from medical school. This can be reinforced further for those pursuing formal residency training in paediatric medicine. Routine assessments may be conducted, including organising theory tests to appraise knowledge of DOHaD concepts, and conducting practical sessions with standardised patients to assess communication and counselling skills. Embedding patient education and counselling skills into the curriculum are essential, as this could enhance the confidence and effectiveness of the medical professional in guiding healthy nutrition and lifestyle choices in their patients and caregivers. Providing continuing medical education and training programmes for DOHaD should also be considered. This may be available in the form of workshops, conferences, and seminars. In addition, although not examined in this study, such training should not be confined to paediatric residents, obstetrics and gynaecology residents, and medical students. To provide effective maternal and child healthcare in an institution, every healthcare provider, including doctors of all ranks, nurses, and allied health professionals, should be equipped with the proficiency and be well versed in DOHaD theories. The efficacy of such interventional educational policies may be analysed in further follow-up studies.

From a policy point of view, it may be ideal to consider creating clinical practice guidelines grounded in DOHaD concepts to help translate these ideas into clinical practice and assist physicians when counselling patients. This would raise the standards of care rendered to women and children, making the transformation of DOHaD principles into routine practice. To increase the outreach of these guidelines and their relevant concepts, trained providers may hold sharing sessions for other physicians who work in a primary care setting. Accreditation programmes in DOHaD counselling can also be considered for these physicians practicing in the primary care setting, with the focus on health promotion and lifestyle behavioural changes. This will equip them with the necessary skills to counsel their patients in the community on an opportunistic basis. From a health promotion standpoint, such initiatives may ensure that relevant principles are readily accessible to the general public including parents and other members of the family nucleus. Online educational materials and modules catered to parents may also be developed, as seen in initiatives from other countries like First 1000 Days Australia [27], as well as Healthier Together in the United Kingdom [28].

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is possessing a 100% response rate, which increases the reliability of our results. However, there was a lack of a validated questionnaire when assessing the KAP of physicians in a paediatric department. We acknowledge that there was no face, construct, or criterion validation by conducting a pilot evaluation among a smaller group of respondents. However, we ensured content validation by incorporating input from domain experts during the development of the questionnaire items, in accordance with existing KAP guidelines. In addition, the knowledge and attitudes sections of our questionnaire had good Cronbach’s Alpha indices of at least 0.7, suggesting good internal consistency. Nevertheless, this study can be further expanded to evaluate the KAP of other healthcare professionals involved in maternal and child health, including nurses and allied health professionals. Instead of solely administering questionnaires, conducting on-site evaluation of practices and interviews of these healthcare professionals can also be considered in future studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrated the existing lack of awareness about DOHaD among paediatric physicians. Despite close contact with patients, with opportunities to counsel and provide anticipatory guidance, this is not congruent with a sense of competence and being well-equipped enough to do so. However, it is a positive sign that both MOs and REGs, who interact with caregivers of patients during the first two years of life, express a desire to learn more about DOHaD principles, so that they are able to provide an improved level of care to impact maternal and child health. With this in mind, changes can be made to pragmatically enhance the understanding and practice of DOHaD within healthcare, and even beyond to the community.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

DC, SC, and FY were involved in the conception and design of the study. RZ cleaned and analyzed the data. DC, KCW, LSL and RZ collectively interpreted the analyzed data and findings. DC, TH, and RZ drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and revised by KCW, LSL, SC, CMC, and FY.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in our institution in accordance to the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB). Informed consent to participate in this study was provided by each respondent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fleming TP, Watkins AJ, Velazquez MA, Mathers JC, Prentice AM, Stephenson J, et al. Origins of lifetime health around the time of conception: causes and consequences. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1842–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Developmental origins of health and disease–global public health implications. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(1):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penkler M, Hanson M, Biesma R, Müller R. DOHaD in science and society: emergent opportunities and novel responsibilities. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(3):268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianco-Miotto T, Craig JM, Gasser YP, van Dijk SJ, Ozanne SE. Epigenetics and DOHaD: from basics to birth and beyond. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2017;8(5):513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, Brauer M, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai H, Alsalhe TA, Chalghaf N, Riccò M, Bragazzi NL, Wu J. The global burden of disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: an analysis of the global burden of Disease Study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(7):e1003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnusson RS. Global health governance and the challenge of chronic, non-communicable disease. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38(3):490–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKerracher L, Moffat T, Barker M, Williams D, Sloboda DM. Translating the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease concept to improve the nutritional environment for our next generations: a call for a reflexive, positive, multi-level approach. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(4):420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molinaro ML, Evans M, Regnault TRH, de Vrijer B. Translating developmental origins of health and disease in practice: health care providers’ perspectives. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2021;12(3):404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.War On Diabetes. Ministry of Health, Singapore; [ https://www.moh.gov.sg/wodcj

- 11.Promoting overall healthier living while targeting specific sub-populations: Ministry of Health, Singapore. 2022 [ https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/promoting-overall-healthier-living-while-targeting-specific-sub-populations

- 12.Tan CC, Lam CSP, Matchar DB, Zee YK, Wong JEL. Singapore’s health-care system: key features, challenges, and shifts. Lancet. 2021;398(10305):1091–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap F, Loy SL, Ku CW, Chua MC, Godfrey KM, Chan JKY. A Golden Thread approach to transforming Maternal and Child Health in Singapore. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku CW, Kwek LK, Loo RSX, Xing HK, Tan RCA, Leow SH et al. Developmental origins of health and disease: knowledge, attitude and practice of obstetrics & gynecology residents, pediatric residents, and medical students. Women Health. 2023:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Moscetti CW, Pronk NP. Invisible seams: preventing childhood obesity through an improved obstetrics-pediatrics care continuum. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrade C, Menon V, Ameen S, Kumar Praharaj S. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in Psychiatry: practical Guidance. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(5):478–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FormSG. [https://form.gov.sg/.].

- 18.Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyamada M, Lim A, Dixon R, Wall C, Bay J. Development of understanding of DOHaD concepts in students during undergraduate health professional programs in Japan and New Zealand. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2018;9(3):253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes MD, Heaton TL, Goates MC, Packer JM. Intersystem Implications of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease: Advancing Health Promotion in the 21st Century. Healthc (Basel). 2016;4(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jacob CM, Hanson M. Implications of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease concept for policy-making. 2020.

- 22.Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE Guide 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunha AJ, Leite Á, Almeida IS. The pediatrician’s role in the first thousand days of the child: the pursuit of healthy nutrition and development. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91(6 Suppl 1):S44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damm L, Leiss U, Habeler U, Ehrich J. Improving Care through Better Communication: understanding the benefits. J Pediatr. 2015;166(5):1327–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodson NA, Talib HJ, Gao Q, Choi J, Coupey SM. Pediatricians as child health advocates: the role of Advocacy Education. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(1):13–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniels SR, Hassink SG, NUTRITION CO. The role of the Pediatrician in Primary Prevention of obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e275–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australia FD. First 1000 Days Australia Australia [ https://www.first1000daysaustralia.com/

- 28.England NHS. Healthier Together [ https://www.what0-18.nhs.uk/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].