Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular diseases due to arteriosclerosis are the most common causes of death and disability in both men and women. Hypercholesterolemia, a treatable risk factor, is often detected after a delay in women, and then inadequately treated. It is, therefore, important to know the sex-specific aspects of cholesterol metabolism and to address them specifically.

Methods

We conducted a selective literature search in PubMed with particular attention to current guidelines.

Results

In the population as a whole, the age-associated rise in serum cholesterol levels occurs approximately 10 years later in women than in men. Women are exposed to a higher cholesterol load than men at the beginning of their lives, and especially after menopause. This is correlated with a later, but nonetheless clinically relevant rise in the incidence of myocardial infarction in older women. Because women’s LDL cholesterol and lipoprotein(a) levels rise after menopause, their lipid profiles should be re-evaluated at this time. Moreover, conditions that are specific to women such as polycystic ovary syndrome, contraception, and especially the phases of life—such as planning to become pregnant, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—need to be considered for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Sex-specific differences and cholesterol-associated risks are particularly pronounced in women with familial hypercholesterolemia (prevalence 1:250).

Conclusion

Lowering high cholesterol levels, especially in postmenopausal women, may prevent the development of cardiovascular diseases.

CME plus+

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. The questions on this article can be found at http://daebl.de/RY95. The closing date for entries is June 13, 2025.

Participation is possible at cme.aerztebatt.de

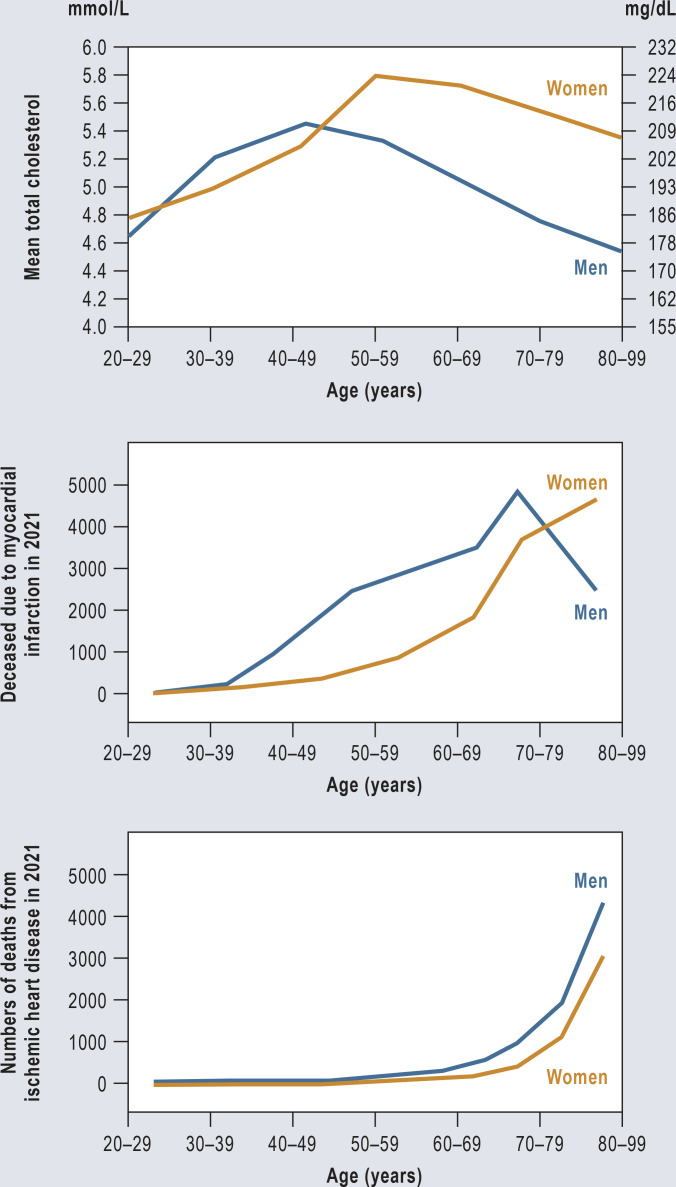

Cardiovascular diseases are by far the most common cause of death in women (1). In 2022, 190 736 women died in Germany as a result of this group of diseases (2). The sequelae of arteriosclerosis are a major factor for morbidity, physical disability, and reduced quality of life in women. The increase in risk per mg of LDL cholesterol is the same for women as for men (3, 4). In both sexes, the increase in serum cholesterol levels over the course of life precedes the increase in heart attacks (Figure). Cholesterol levels in men rise approximately 10 years earlier. Overall, the percentage of deaths from cardiovascular causes is higher in men across all age groups (3). In women, serum cholesterol levels do not rise significantly until after menopause, reaching higher levels over time than in men (5). The rate of myocardial infarction then rises in women in the 7th decade of life.

Figure.

Mean total cholesterol, myocardial infarction mortality, and ischemic heart disease mortality in women and men in Germany by age.

Data source: German Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt, Destatis) 2022 (e13) and Martin et al. 2023 (e14)

Current data point to particular sex-specific aspects of pathogenesis—for example, microvascular manifestations are significantly more common in women (6). A considerable proportion of cases of arteriosclerosis can be treated by timely diagnosis of the risk factor hypercholesterolemia (7). There are important special aspects of cholesterol metabolism in women. For example, cholesterol load rises significantly following the menopause in particular. Here, the possible preventive potential of lowering high cholesterol levels becomes evident.

Methods

The research for this study is based on a selective literature search in PubMed. Current guidelines were also taken into consideration.

Prenatal phase

The human prenatal phase is characterized as a whole by low cholesterol levels (8). Towards the end of pregnancy, between the 36th and 40th week, total cholesterol is around 50 mg/dL. As early on as in the 1980s, Braun and Goldstein compared average cholesterol levels in mammals with those in Homo sapiens as part of their Nobel Prize-winning work. During the embryonic phase, in which pronounced cell division and organ development take place, levels in humans are similar to those in animals (serum LDL cholesterol level of around 25 mg/dL). According to Braun and Goldstein’s calculations, 2.5 mg/dL LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) is sufficient for optimal binding to hepatic LDL receptors; physiological levels of serum LDL-C are around 25 mg/dL (9–11). Following birth, serum cholesterol rises markedly. Investigations using magnetic resonance spectroscopy show that female newborns have on average higher levels of cholesterol metabolites and polyunsaturated fatty acids compared to male newborns (12).

LDL-cholesterol in childhood

The Dutch Lifelines cohort study investigated 8071 children (3823 boys and 4248 girls) (13). In boys aged 8 years, the median LDL-C is around 90 mg/dL. From the age of 12 years onwards, the average LDL-C falls, with the lowest values measured at around the age of 15 years; levels rise slightly towards the ages of 17 and 18 years.

The serum LDL cholesterol level in girls is overall higher compared to that in boys. Much like in boys, there is a slight drop in LDL-C around the age of 10 years, with the lowest values seen around the age of 14 years. The subsequent rise in LDL-C is more pronounced in girls than in boys. At around the age of 17 years, the LDL-C level in young women is significantly higher, with a median value of 95 mg/dL compared to 82 mg/dL in boys. The 95th percentile is 144 mg/dL in girls versus 126 mg/dL in boys. Thus, overall, cholesterol levels are higher in girls than in boys up until young adulthood.

Cholesterol level and duration of exposure determine the extent of vascular damage

In addition to the level of an endothelium-damaging noxious agent (for example, the number of cigarettes smoked, blood pressure, blood glucose level, cholesterol level), the duration of exposure plays a major role in the development of arteriosclerosis and the subsequent arteriosclerosis-related vascular complications in middle and old age (14). Much like pack-years in smokers, one can also calculate “cholesterol years” (15–17). Thus, even small increases in vascular risk factors that emerge early in life and/or persist over a long period of time have a significant cumulative negative effect on cardiovascular risk.

With regard to serum cholesterol, this relationship is particularly significant in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (18). Elevated serum cholesterol levels in childhood and adolescence correlate with higher cholesterol levels in later life (19). Childhood cardiovascular risk factors are associated with a higher number of cardiovascular events in middle age (20).

Lipid profiles in young adulthood

Young adult women have lower levels of LDL-C and triglycerides and higher levels of serum HDL cholesterol compared to men. At the ages of 20–49 years, LDL-C in men (median 154 mg/dL) increases by around 64%, while triglyceride levels almost double. In women, LDL-C levels remained virtually unchanged between the ages of 18 and 35 years. In contrast, levels rise by around 42% up to the age of 59 years (median 142 mg/dL), while triglyceride levels remain stable in older women (5, 21).

Large data sets, such as those from the Copenhagen General Population Study, show that the rise in cholesterol levels with age begins approximately 10 years earlier in men than in women (6). While the peak of this rise in cholesterol occurs in men between the ages of 40 and 50, it occurs in women between the ages of 50 and 60 years. These epidemiological data have been reproduced in many countries (5).

In men, a marked rise in triglyceride levels is seen between the ages of 30 and 50 years, while in women, triglyceride levels rise overall less sharply and later in life. The increase in triglycerides in men may be associated in part with their higher alcohol consumption. In women, one sees an increase in HDL cholesterol from the age of 30 years onwards, peaking at around the age of 50 years, with HDL-C levels remaining relatively constant in later life. The increase in HDL-C levels and median levels are significantly lower in men (21).

LDL cholesterol during the menstrual cycle

Estrogens are associated with an increase in apolipoprotein (apo) B synthesis and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) production as well as increased expression of LDL receptors. This leads to a rise in triglycerides and HDL-C and a drop in LDL cholesterol (22). Therefore, serum LDL-C levels in women during the mid-follicular phase of their cycle with low estrogen levels is slightly higher (102 mg/dL on average) than during the mid-luteal phase with higher estrogen levels (LDL-C on average 97 mg/dL, that is to say, a delta of 5 mg/dL).

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine diseases in women of child-bearing age, with a prevalence rate of between 6 and 10% (23–25). Increased release of androgens from theca cells in the ovaries plays an important role in its pathology. PCOS is associated with elevated triglyceride levels (on average + 26 mg/dL), elevated LDL-C levels (+ 12 mg/dL) as well as obesity and insulin resistance. All in all, it significantly increases the risk for arteriosclerotic disease (24). A large prospective cohort study found that the adjusted relative risk of a fatal cardiovascular event in women with extremely irregular menstrual cycles was increased with a hazard ratio of 1.88 (95% confidence interval [1.32; 2.67]; 2.7% of the population) (26).

Effects of contraception on LDL cholesterol

Estrogen-containing contraceptives lead to a slight decrease in LDL-C levels. These effects are counteracted by progesterone. Women on combined oral contraceptives have on average a 13–75% increase in fasting triglycerides and a 12–14% reduction in LDL-C levels (27–29). Contraceptives containing progesterone only, whether oral or intrauterine, as well as copper intrauterine devices (IUDs) do not produce clinically relevant changes in serum lipid profile (27–29).

Pregnancy

The largest changes in lipid profile occur during pregnancy (30). From the second month of pregnancy onwards, the levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides rise steadily. The average increase in LDL-C is in the range of 40–60%, while HDL-C rises by 20–40%. Triglyceride levels rise between two- and three-fold. Furthermore, the lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) level approximately doubles (6).

The mechanisms involved in the transfer of serum lipids via the placenta and yolk sac into the fetal circulation and the trophoblast are not yet fully understood. There is an association between maternal cholesterol values and fetal cholesterol levels. Experimental studies have given rise to the well-founded hypothesis that this could play an important role in the programing of fetal development (30, 31). Relative to the population as a whole, there is evidence that the cardiovascular risk increases by > 50% in women with six or more pregnancies (32, 33). Of particular quantitative relevance is the rise in cholesterol levels during pregnancy in young women with familial hypercholesterolemia (34, 35). Following childbirth, levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C fall again. This fall occurs faster in women who breastfeed than in those who bottlefeed (30, 31).

Lipid-reducing drugs during pregnancy

Statins

The use of statins is not approved during pregnancy, and women wishing to become pregnant must discontinue their statin medication 1–2 months prior to conception (36, 31). However, a growing number of case reports show no evidence of teratogenicity for statins in humans. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also continues to recommend against the use statins during pregnancy. However, it suggests that a joint decision be made in selected women; this applies, for example, to patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or pre-existing manifestations of arteriosclerosis (36, 31). As part of the necessary patient education of women of childbearing age when prescribing statins, it is important on the one hand to highlight the lack of approval of these drugs during pregnancy and to document this, but at the same time not to place a negative connotation on the drug class. The key to success here is to take sufficient time when first prescribing a lipid-lowering medication in young patients.

Ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, PCSK9 inhibitors, and high-dose omega-3 fatty acids (for example, eicosapentaenoic acid) are also not approved for use during pregnancy.

Fibrates

With regard to fibrates, a relevant re-evaluation has taken place in recent years, since a number of large studies show that they have no effect on clinical endpoints (37). Older recommendations issued by US medical societies suggest that the use of fibrates should be considered in individual cases of very high triglyceride levels (> 1000 mg/dL), for example, in pregnant women with a history of pancreatitis or triglyceride levels > 1000 mg/dL (38). When used, fibrates should be taken in the second semester after embryogenesis. However, there is no reliable evidence of efficacy for the use of fibrates in the prevention of pancreatitis. Therefore, there are generally few grounds for prescribing a fibrate.

Anion exchange resins (e.g., colestyramine, colestipol) inhibit enteral lipid absorption and do not in themselves have a systemic effect. This is a potential safety benefit in the case of pregnancy. In contrast, one must take into account the fact that the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and other components is inhibited, which in turn could have a negative effect on the fetus.

The problem of the lack of data and the resulting lack of approval for lipid-lowering drugs also applies to the period of breastfeeding. The Table provides an overview of the lipid-lowering drugs available and their possible use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Table. Lipid-reducing drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

| Drug | Transfer via the placenta | Excretion in breast milk | Indication during pregnancy |

| Colestyramine | Not known | No Can be used during breastfeeding. |

Treatment of choice for hyperlipidemiaduring pregnancy |

| Gemfibrozil | Yes | Not known Should not be used during breastfeeding. |

Not indicated |

| Fenofibrate | Yes | Not known Should not be used during breastfeeding. |

Not indicated |

| Ezetimibe | Not known | Not known Rat studies have shown that ezetimibe passes into breast milk. Must not be used during breastfeeding. |

Not indicated |

| Statins | Yes | Not known Excreted in rat milk. |

Contraindicated The decision on whether statin use should continue during pregnancy requires joint decision-making by the patient and doctor. |

| Alirocumab | Yes Alirocumab is a recombinant IgG1 antibody and, as such, presumably crosses the placental barrier |

Not known Human immunoglobulin G (IgG) passes into breast milk, particularly into the colostrum; during this phase, the use of alirocumab is not recommended in breastfeeding women. |

The use of alirocumab is not recommended during pregnancy unless the clinical status of the mother requires treatment with alirocumab. |

| Evolocumab | Yes Evolocumab is a recombinant IgG1 antibody and, as such, presumably crosses the placental barrier |

Not known A risk to the breastfed newborn/infant cannot be ruled out. |

Not indicated Evolocumab must not be used during pregnancy unless the clinical status of the mother requires treatment with evolocumab. |

| Inclisiran | Not known | Not known This drug should not be used during breastfeeding. Inclisiran has been found in the milk of lactating rats. |

As a precautionary measure, the use ofinclisiran shall be avoided during pregnancy. |

| Bempedoic acid | Yes | Not known Its use is contraindicated during breastfeeding. |

Contraindicated |

High cholesterol exposure in young women with familial hypercholesterolemia

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is one of the most common genetic diseases, with a worldwide prevalence rate of approximately 1: 313 (39). Familial hypercholesterolemia is underdiagnosed and continues to be associated with early-onset arteriosclerosis and related diseases (18, 40, e1). The principles of treatment do not differ between men and women (e2). The particular risk to young women with familial hypercholesterolemia in terms of their cholesterol-associated lifetime risk arises from several components:

All factors that increase cholesterol levels in young women have a particularly pronounced effect due to the much higher absolute levels when familial hypercholesterolemia is present (15). Many people with familial hypercholesterolemia go undiagnosed or are diagnosed late (39). Furthermore, women receive poorer care in terms of lipid-lowering drugs (e3–e5). Women are approximately 22% less likely to achieve their LDL-C target level than are men (e6). And finally, young women of childbearing age with heterozygous hypercholesterolemia and wishing to have children experience considerable treatment interruptions, both during the period of trying to become pregnant as well as during pregnancy and breastfeeding. This results in a significantly higher cholesterol load in young women with FH compared to men with FH—a load that is naturally even more pronounced compared to individuals without FH (15).

Cholesterol following menopause

The reduction and loss of follicular function in the ovaries leads to a reduction in endogenous estrogen production and the end of menstruation (e7, e8). This is accompanied by a significant rise in levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-C (e9). There is also an association with increased visceral fat tissue, body mass index, blood pressure, and insulin resistance. Altogether, this results in a higher arteriosclerotic cardiovascular risk. LDL-C levels in postmenopausal women are significantly and consistently higher than those in men (Figure). Furthermore, one sees a significant increase in Lp(a) in women after the age of 50 years, with Lp(a) values reaching higher levels in older women than in men (6). While estrogen therapy may have a small beneficial effect on LDL-C levels, blood glucose levels, and insulin, large studies have shown that hormone replacement therapy does not confer any beneficial effects in terms of primary or secondary cardiovascular prevention (e7, e8). The addition of gestagen weakens the positive effects of estrogens on lipids.

Statin-related muscle pain

Clinical studies and large registries consistently show that statin-related muscle pain occurs more frequently in women compared to men (relative risk of around 1.5) (e10, e11). At present, neither the underlying cause of this clinically relevant problem nor sex-specific strategies for risk stratification and therapy are well understood. Further research is needed here.

Résumé

Cardiovascular diseases are by far the most common cause of death in women. Furthermore, arteriosclerosis is a major factor for morbidity, physical disability, and reduced quality of life in women. A significant proportion of cases of arteriosclerosis can be well treated if cardiovascular risk factors hypercholesterolemia are diagnosed in a timely manner. The data show that, contrary to the widely held view, women are exposed to a higher cholesterol load than men both at the beginning of life and then in particular following menopause. Sex-specific conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome and, in particular, the phases of life such as planning to become pregnant, pregnancy, and breastfeeding need to be considered. Sex-specific differences are particularly pronounced in women with familial hypercholesterolemia. Due to the increase in LDL-C and lipoprotein(a) levels following menopause, it is judicious to re-evaluate patients’ lipid profile at this time. Our most important recommendations are summarized in the Box (e12).

Box. Cholesterol as a risk factor in women.

Cardiovascular diseases are the most common cause of death also in women. The medical care of women should include a review of traditional and sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors as early on as in childhood and adolescence.

Elevated lipid levels (LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, lipoprotein [a]) should be diagnosed and managed with the treatment recommended in the guidelines.

Since lipoprotein(a) levels rise in women after the menopause, it is beneficial to measure them again after the age of 50 years.

The cholesterol load is higher in women with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) compared to men. This is due to frequently delayed diagnosis, inadequate pharmacological lipid-lowering, and the discontinuation of these treatments before and during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Therefore, women with FH require particularly close monitoring.

Improved awareness of sex-specific aspects of the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, combined with the modern treatment options available, would lead to a significant risk reduction in women.

Questions on the article in issue 12/2024:

Special Aspects of Cholesterol Metabolism in Women

The submission deadline is 13 June 2025. Only one answer is possible per question.

Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Approximately how high is total cholesterol in the fetus towards the end of pregnancy (36th–40th gestational week)?

25 mg/dL

50 mg/dL

75 mg/dL

125 mg/dL

150 mg/dL

Question 2

Which statement regarding sex-specific differences in cholesterol levels is true according to the article?

Men have on average higher total cholesterol than women of the same age at any age.

In women, serum cholesterol levels steadily fall from the age of 19 years.

In men, the average serum cholesterol level steadily increases from the age of 20 years.

In old age (> 70 years), men have on average higher serum cholesterol levels than women.

In women, serum cholesterol levels rise significantly after menopause, reaching higher levels over time than in men.

Question 3

At what age does the LDL cholesterol level in boys usually reach its lowest value?

Around the age of 3 years

Around the age of 7 years

Around the age of 10 years

Around the age of 15 years

Around the age of 18 years

Question 4

According to the information in the article, how does a woman’s lipid metabolism change during pregnancy?

LDL cholesterol and triglycerides steadily increase from the 2nd month of gestation.

Her HDL cholesterol level steadily falls from the 2nd trimester onwards.

Only HDL cholesterol increases during pregnancy, while LDL and triglycerides usually remain unchanged.

LDL cholesterol increases in early pregnancy and decreases again from the beginning of the 2nd trimester.

Not until the end of pregnancy (in the 3rd trimester) do LDL and HDL cholesterol increase slightly.

Question 5

What effects do combined oral contraceptives have on cholesterol metabolism in women?

They cause LDL cholesterol levels to rise and fasting triglycerides to fall.

The effect of oral contraceptives on cholesterol levels is not measurable.

They cause fasting triglycerides and LDL cholesterol levels to rise.

They cause an increase in fasting triglycerides and a decrease in LDL cholesterol levels.

They cause fasting triglycerides and LDL cholesterol levels to fall.

Question 6

According to the text, which disease is associated with elevated LDL cholesterol levels, elevated triglycerides, obesity, and insulin resistance?

Endometriosis

Adnexitis

Uterine fibroids

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Hypothyroidism

Question 7

According to the text, which adverse effects of cholesterol-lowering medications occur more commonly in women than in men?

Statin-related muscle pain

Fibrate-related gastric symptoms

Statin-related gastric symptoms

Fibrate-related muscle pain

Statin-related migraine attacks

Question 8

What statement does the article make regarding the drug treatment of hyperlipidemia during pregnancy?

Fenofibrate prevents pancreatitis.

Ezetimibe should be used.

Evolocumab is approved.

Colestyramine can inhibit the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Bempedoic acid should be used.

Question 9

According to the information in the article, which statement regarding the use of statins during pregnancy most applies?

Case reports provide evidence for teratogenic effects of statins in humans.

If a pregnancy begins while statins are being used, the statin dose needs to be increased promptly.

Statins are not approved for use during pregnancy and should be discontinued 1–2 months prior to conception if possible.

Preferably, bempedoic acid should be prescribed as an alternative to statins during pregnancy.

Due to the altered cholesterol metabolism, there is no need to use cholesterol-lowering drugs during pregnancy, even in women with familial cholesterolemia.

Question 10

According to the information in the article, which statement regarding familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) most applies?

Due to X-linked inheritance, FH only affects males.

The disease heterozygous FH is very rare with a prevalence rate of 1: 300,000.

Many people with FH go undiagnosed or are diagnosed late.

Due to X-linked inheritance, FH only affects women.

Due to Y-linked inheritance, FH only affects males

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

IGB received lecture fees, reimbursement of travel expense and congress fees as well as honoraria for Advisory Board activities and/or research support from Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, Sanofi, Synlab, Amarin, and Ultragenyx. She is Deputy Chairperson of DACH and a member of the IAS Executive Committee.

UL received lecture fees, reimbursement of travel expense and congress fees as well as honoraria for Advisory Board activities and/or research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Synlab. He fulfills various functions in the DGK, DACH, EAS, and ESC.

References

- 1.Timmis A, Vardas P, Townsend N, et al. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021: executive summary. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8:377–382. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?sequenz=tabelleErgebnis&selectionname=23211-0002#abreadcrumb (last accessed on 5 April 2024) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Group WCRCW. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3. e1332-e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel B, Acevedo M, Appelman Y, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet. 2021;397:2385–2438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00684-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin SS, Niles JK, Kaufman HW, et al. Lipid distributions in the Global Diagnostics Network across five continents. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2305–2318. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgozoglu LS, Badimon L, et al. Women, lipids, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a call to action from the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:4157–4173. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parhofer KG, Laufs U. Lipid profile and lipoprotein(a) testing. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;120:582–588. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2023.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson HJ, Jr, Simpson ER, Carr BR, MacDonald PC, Parker RC., Jr The levels of plasma cholesterol in the human fetus throughout gestation. Pediatr Res. 1982;16:682–683. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198208000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein JL, Basu SK, Brunschede GY, Brown MS. Release of low density lipoprotein from its cell surface receptor by sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Cell. 1976;7:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichl D, Myant NB, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Biologically active low density lipoprotein in human peripheral lymph. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:64–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI108926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Øyri LKL, Bogsrud MP, Christensen JJ, et al. Novel associations between parental and newborn cord blood metabolic profiles in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. BMC Med. 2021;19:91. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01959-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balder JW, Lansberg PJ, Hof MH, Wiegman A, Hutten BA, Kuivenhoven JA. Pediatric lipid reference values in the general population: the Dutch lifelines cohort study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D, et al. Two phase 3 trials of inclisiran in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1507–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen AK, Bogsrud MP, Christensen JJ, et al. Young women with familial hypercholesterolemia have higher LDL-cholesterol burden than men: novel data using repeated measurements during 12-years follow-up. Atheroscler Plus. 2023;51:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.athplu.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt HH, Hill S, Makariou EV, Feuerstein IM, Dugi KA, Hoeg JM. Relation of cholesterol-year score to severity of calcific atherosclerosis and tissue deposition in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro MD, Bhatt DL. „Cholesterol-Years“ for ASCVD risk prediction and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaboration EASFHS. Global perspective of familial hypercholesterolaemia: a cross-sectional study from the EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC) Lancet. 2021;398:1713–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borén J, Chapman MJ, Krauss RM, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2313–2330. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs DR, Jr., Woo JG, Sinaiko AR, et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1877–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balder JW, de Vries JK, Nolte IM, Lansberg PJ, Kuivenhoven JA, Kamphuisen PW. Lipid and lipoprotein reference values from 133,450 Dutch Lifelines participants: age- and gender-specific baseline lipid values and percentiles. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.05.007. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mumford SL, Schisterman EF, Siega-Riz AM, et al. A longitudinal study of serum lipoproteins in relation to endogenous reproductive hormones during the menstrual cycle: findings from the BioCycle study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95 doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0109. E80-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCartney CR, Marshall JC. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:54–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1514916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild RA, Rizzo M, Clifton S, Carmina E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1073–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.027. e1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krentowska A, Kowalska I. Metabolic syndrome and its components in different phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2022;38 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3464. e3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2013–2017. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godsland IF, Crook D, Simpson R, et al. The effects of different formulations of oral contraceptive agents on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1375–1381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011153232003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graff-Iversen S, Tonstad S. Use of progestogen-only contraceptives/medications and lipid parameters in women age 40 to 42 years: results of a population-based cross-sectional Norwegian survey. Contraception. 2002;66:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng YW, Liang S, Singh K. Effects of Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) and Ortho Gynae T380 intrauterine copper device on lipid metabolism—a randomized comparative study. Contraception. 2009;79:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiznitzer A, Mayer A, Novack V, et al. Association of lipid levels during gestation with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:482. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.032. e1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wild R, Feingold KR. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. South Dartmouth (MA): Endotext; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ness RB, Harris T, Cobb J, et al. Number of pregnancies and the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1528–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305273282104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ness RB, Schotland HM, Flegal KM, Shofer FS. Reproductive history and coronary heart disease risk in women. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:298–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klevmoen M, Bogsrud MP, Retterstol K, et al. Loss of statin treatment years during pregnancy and breastfeeding periods in women with familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2021;335:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klevmoen M, Mulder J, Roeters van Lennep JE, Holven KB. Sex differences in familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25:861–868. doi: 10.1007/s11883-023-01155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpern DG, Weinberg CR, Pinnelas R, Mehta-Lee S, Economy KE, Valente AM. Use of medication for cardiovascular disease during pregnancy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:457–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das Pradhan A, Glynn RJ, Fruchart JC, et al. Triglyceride lowering with pemafibrate to reduce cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1923–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, Waugh J, Robson SC, Bell R. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beheshti SO, Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Worldwide prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia: meta-analyses of 11 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2553–2566. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svendsen K, Krogh HW, Igland J, et al. 2.5-fold increased risk of recurrent acute myocardial infarction with familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2021;319:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Ferrières J, Farnier M, Bruckert E, et al. Burden of cardiovascular disease in a large contemporary cohort of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atheroscler Plus. 2022;50:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.athplu.2022.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Watts GF, Gidding SS, Hegele RA, et al. International Atherosclerosis Society guidance for implementing best practice in the care of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:845–869. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Gouni-Berthold I, Berthold HK, Mantzoros CS, Bohm M, Krone W. Sex disparities in the treatment and control of cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1389–1391. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Hopstock LA, Eggen AE, Lochen ML, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T. Secondary prevention care and effect: total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and lipid-lowering drug use in women and men after incident myocardial infarction—the Tromso Study 1994-2016. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17:563–570. doi: 10.1177/1474515118762541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Xia S, Du X, Guo L, et al. Sex differences in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in China. Circulation. 2020;141:530–539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Gavina C, Araujo F, Teixeira C, et al. Sex differences in LDL-C control in a primary care population: the PORTRAIT-DYS study. Atherosclerosis. 2023;384 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2023.05.017. 117148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women‘s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353–1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Ko SH, Kim HS. Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients. 2020;12:202. doi: 10.3390/nu12010202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Bytyci I, Penson PE, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Prevalence of statin intolerance: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3213–3223. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Bair TL, May HT, Knowlton KU, Anderson JL, Lappe DL, Muhlestein JB. Predictors of statin intolerance in patients with a new diagnosis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease within a large integrated health care institution: the IMPRES Study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020;75:426–431. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12. https://herzmedizin.de/nationale-herz-kreislauf-strategie.html#Frueherkennung (last accessed on 5 April 2024) [Google Scholar]

- E13.Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) Deutscher Herzbericht 2022. https://www.dgpk.org/wp-content/uploads/DHB22-Herzbericht-2022.pdf (last accessed on 9 April 2024) [Google Scholar]

- E14.Martin SS, Niles JK, Kaufman HW, et al. Lipid distributions in the Global Diagnostics Network across five continents. European Heart Journal. 2023;44:2305–2318. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]