Keywords: acute kidney injury, mortality, sex disaggregated analysis, sickle cell anemia, vaso-occlusive pain crises

Abstract

A growing body of research is categorizing sex differences in both sickle cell anemia (SCA) and acute kidney injury (AKI); however, most of this work is being conducted in high-resource settings. Here, we evaluated risk factors and clinical parameters associated with AKI and AKI severity, stratified by sex, in a cohort of children hospitalized with SCA and vaso-occlusive pain crisis (VOC). The purpose of this study was to explore sex disparities in a high-risk, vulnerable population. This study was a secondary analysis of data collected from a cohort of Ugandan children between 2 and 18 yr of age prospectively enrolled. A total of 185 children were enrolled in the primary study; 41.6% were female and 58.4% were male, with a median age of 8.9 yr. Incident or worsening AKI (P = 0.026) occurred more frequently in female compared with male children, despite no differences in AKI on admission. Female children also had altered markers of renal function including higher creatinine levels at admission (P = 0.03), higher peak creatinine (P = 0.006), and higher urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) at admission (P = 0.003) compared with male children. Female children had elevated total (P = 0.045) and conjugated bilirubin at admission (P = 0.02) compared with male children and higher rates of hematuria at admission (P = 0.004). Here, we report sex differences in AKI in children with SCA and VOC, including increased incidence and worsening of AKI in female pediatric patients, in association with an increase in biological indicators of poor renal function including creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and NGAL.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY In this study, we report an increased risk of developing acute kidney injury (AKI) during hospitalization, worsening AKI, and death among females with sickle cell anemia (SCA) hospitalized with an acute pain crisis compared with males. The sex differences in AKI were not explained by socioeconomic differences, severity of pain, or disease severity among females compared with males. Together, these data suggest that female children with SCA may be at increased risk of AKI.

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an autosomal recessive hemoglobinopathy resulting in sickle-shaped red blood cells (RBCs), with reduced deformability and shortened lifespan. An estimated 300,000 children are born each year with SCA, 80% of whom are living in sub-Saharan Africa (1, 2). The presence of SCA is associated with a substantial increase in childhood morbidity and mortality with decreased health-related quality of life (3), which can lead to marginalization and psychosocial stress within families (4). Vasco-occlusive pain crises (VOCs) are a common complication of SCA that occurs when blood flow in capillaries is blocked by rigid sickled RBCs, leading to ischemia, tissue necrosis, and multi-organ damage. VOCs are associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) and subsequent mortality (5, 6). Established risk factors for AKI in children experiencing VOC include volume depletion and nephrotoxic medications [e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain, aminoglycosides for infection] (6, 7). Emerging research indicates that sex may also be an important factor in the clinical progression of pediatric sickle cell disease, including risk for AKI and mortality (8, 9).

In children with SCA and VOC, we previously reported that the development of incident or worsening AKI and AKI-associated mortality occurred more frequently in female children compared with male children (9). However, the relationship between sex, VOC, and AKI in children with SCA has not been examined. Current evidence suggests the relationship between sex and renal disease is multifaceted (10–12). While female sex is a risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease, male sex is associated with more rapid progression to renal failure and mortality (10, 12). In the context of AKI, much of the data surrounding sex disparities are conflicting and etiologically or contextually dependent (11). Sexual dimorphism is a recognized factor in the pathobiology of renal disease; however, more research is required to fully elucidate the nature of this complex relationship. Moreover, most research examining sex and AKI has been conducted in preclinical studies or adult populations in high-income settings. In contrast, the impact of sex and AKI on pediatric populations in sub-Saharan Africa, where children have the highest burden of risk factors for AKI (e.g., infection, septic shock, SCA, etc.) and lowest access to renal replacement therapy (13), is understudied.

Current research suggests that AKI is an underreported problem in children with SCA in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and evidence in high-income settings suggests that sex impacts clinical outcomes for children with SCA, including disease progression (8, 14, 15). Here, we evaluated risk factors and clinical parameters associated with AKI and AKI severity, stratified by sex, to explore putative mechanisms underlying sex disparities in outcomes in a high-risk, vulnerable population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This study was a secondary analysis from a prospective cohort study designed to assess the prevalence of AKI in children admitted to Mulago National Referral Hospital in Uganda with SCA and VOCs. The sample size was calculated based on previously reported prevalence rates of AKI (2.3% in children with pain crises, 6.9% in children with moderate acute chest syndrome, and 13.6% in children with severe acute chest syndrome) among children with SCA and VOC as previously described (9). The objective of this secondary analysis was to evaluate sex differences in the incidence, etiology, and outcomes of AKI in children with SCA and VOC.

Study Cohort and Procedures

Children were recruited between January and August 2019 from the pediatric emergency unit, which admits an average of three children daily with SCA and VOC. Inclusion criteria included age between 2 and 18 yr, hospital admission and willingness to complete study procedures, SCA documented by hemoglobin electrophoresis, and a pain score of ≥2 (assessed using age-specific pain scales). Pain in children aged 2–3 yr was assessed using the face, legs, activity, cry, and consolability (FLACC) scale (16), the Wong-Baker FACES pain scale in children 3–7 yr of age, and the numeric pain scale in children ≥ 8 yr (17). Children received routine care, which included daily folic acid, malaria prophylaxis (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine), and penicillin V prophylaxis for children under 5 yr of age. A small proportion of children also received hydroxyurea.

At enrollment, each child underwent a thorough history and physical exam that included a detailed assessment of medication use and medical history, anthropometry, signs and symptoms of infection, an evaluation of pain using age-appropriate scales, urinalysis (including dipstick, microscopy, and measurement of albumin and creatinine), complete blood count, and a detailed assessment of kidney function. A basic metabolic panel was assessed using point-of-care iSTAT CHEM8+ cartridges [creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose, ionized calcium, sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate] (Abbott Point of Care, Princeton, NJ). The reported blood pressure was the mean of three independent measurements. Data on Tanner staging were not collected.

Clinical Definitions

Sepsis was defined according to international pediatric sepsis consensus guidelines (18), including temperature <36°C or >38.5°C and ≥1 of age-specific tachycardia, tachypnea, or leukocytosis using age-specific thresholds for children with SCA (18). Hepatomegaly was assessed by abdominal palpation and defined based on the liver being palpable below the costal margin with tender hepatomegaly defined as tenderness on palpation of the liver. Hypertension was defined as a systolic or diastolic blood pressure >95 percentile for children < 13 yr or mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg for children 13 yr of age or older (19). Children were diagnosed with a urinary tract infection based on a positive nitrite or leukocyte test by urinalysis in a child with a history of fever. An acute infection was defined by the presence of a urinary tract infection, sepsis, or malaria.

Laboratory Evaluations

Malaria was evaluated using Giemsa microscopy. A random spot urine sample was collected on admission using a urine bag or urine container for older children and sent to the laboratory within 2 h of collection for urinalysis and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) testing as previously reported (17). Urine creatinine and albumin were assessed using a Cobas 6000 analyzer 501 module (Roche) at Mulago National Referral Hospital. Creatinine was assessed using the modified Jaffe method, and albumin was assessed using an immunoturbidimetric assay. Microalbuminuria was defined as a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 3–30 mg/mmol and macroalbuminuria as a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of >30 mg/mmol. Liver function (aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, albumin, total bilirubin, and conjugated bilirubin) was measured in serum by the Johns Hopkins University Infectious Disease Institute Laboratory on serum samples using a Cobas machine (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Cystatin C was measured on cryopreserved serum using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine immunoassay, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) that correlates to the reference standard (Cat. No. ERM-DA471/IFCC) with a slope of 1.07 and R2 value of 0.998 (20). Pooled serum samples and commercial controls were tested in duplicate on every plate (QC23: Quantikine Immunoassay Control Group 8, R&D Systems). Microbiology to culture blood or urine samples was not feasible.

Assessment of Kidney Function

AKI was defined according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, which use an increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or a 50% increase in baseline creatinine within 7 days (19). Serial creatinine measures were assessed on enrollment, 48 h follow-up, and day 7 or discharge, whichever happened earlier. The iSTAT creatinine assay is an enzymatic assay with amperometric detection on a platinum electrode and is traceable to the isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) reference method using the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference material SRM967. Samples below the limit of detection were assigned a value of 0.19 mg/dL. The definition was modified to exclude children with a 50% increase in creatinine from 0.2 to 0.3 mg/dL. As SCA is associated with kidney dysfunction, baseline serum creatinine was defined using the lowest creatinine measured during hospitalization. In instances where only a single creatinine measure was available, baseline creatinine was estimated using age-based approaches validated in healthy Ugandan children assuming a normal glomerular filtration rate of 120 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (20). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the following CKiD creatinine and cystatin C-based formulas (21): creatinine, eGFR = (0.413 × height)/SCr; cystatin C, eGFR = 70.69 × (serum cystatin C)−0.931; SCr and cystatin C, eGFR = 39.8 × [(height/SCr)0.456] × [(1.8/cystatin C)0.418] × [(30/BUN)0.079] × (1.076male) × [(height/1.4)0.179].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), STATA v17.0 (StataCorp), and GraphPad Prism version 7.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data stratified by sex were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for non-parametric, continuous data) or Pearson’s χ2 test (for categorical data). To evaluate the relationship between sex and AKI risk and severity, multiple Poisson regression models were generated to obtain unadjusted and adjusted estimates with robust estimates of standard errors. Poisson regression was used for binary outcomes as models failed to converge using binomial regression. Models adjusted for the duration of pain, the presence of vomiting, severe anemia, tender hepatomegaly, an acute infection, and exposure to nephrotoxins. Covariates were included based on previously described or hypothesized relationships with AKI. Age was modeled as a spline with a knot at 7 yr of age corresponding to an inflection point in the risk of AKI by sex.

Ethical Approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all study participants, and assent was obtained for children 8 yr of age and older. The Institutional Review Board of Makerere University School of Biomedical Sciences Research and Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the study (first approval date May 13, 2018, IRB No. SBS-S46). The Uganda National Council for Science and Technology provided additional regulatory approval for the study (approval date September 7, 2018, Approval No. HS 2443).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

A total of 185 children were enrolled in the parent study (9). Of these, 41.6% (n = 77) were female and the remaining 58.4% (n = 108) were male. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] age of children in this cohort was 8.9 (5.9, 11.75). While a higher proportion of children under 5 yr old were males [14% (males) vs. 5.4% (females), P = 0.017], there were no other differences in demographics, routine medication use, or medical history between males and females. An overview of the study population disaggregated by sex is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the study population

| Combined (n = 185) |

Male (n = 108) |

Female (n = 77) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr | 8.9 (5.9, 11.8) | 8.5 (5.1, 11.6) | 9.1 (6.3, 11.8) | 0.26 |

| Age categories, n (%) | ||||

| <5 yr | 36 (19.5) | 26 (24.1) | 10 (13.0) | 0.02 |

| 5–10 yr | 73 (39.5) | 39 (36.1) | 34 (44.2) | 0.93 |

| >10 yr | 76 (41.1) | 43 (39.8) | 33 (42.9) | 0.59 |

| Height-for-age z score | −1.4 (−2.3, −0.4) | −1.6 (−2.2, −0.6) | −1.2 (−2.6, −0.2) | 0.49 |

| Weight-for-age z score1 | −1.5 (−2.0, −0.5) | −1.6 (−2.1, −0.8) | −1.1 (−2.0, −0.2) | 0.21 |

| Weight-for-height z score1 | −1.6 (−2.2, −0.4) | −1.8 (−2.5, −0.5) | −1.3 (−2.0, −0.4) | 0.30 |

| BMI-for-age z score1 | −1.3 (−2.3, −0.4) | −1.3 (−2.0, −0.4) | −1.2 (−2.4, 0.1) | 0.49 |

| MUAC, cm | 16.0 (15.0, 17.8) | 16.0 (15.0, 17.4) | 16.3 (15.0, 18.2) | 0.13 |

| HIV infection, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0.42 |

| Routine medication use | ||||

| Folic acid, n (%) | 117 (63.2) | 70 (64.8) | 47 (61.0) | 0.60 |

| Ferrous sulfate, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hydroxyurea, n (%) | 61 (33.0) | 36 (33.3) | 25 (32.5) | 0.90 |

| Penicillin V prophylaxis, n (%) | 11 (6.0) | 8 (7.4) | 3 (3.9) | 0.37 |

| Children <5 yr of age | 5 (13.9) | 3 (11.5) | 2 (20.0) | 0.60 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Prior admission, n (%) | 78 (42.2) | 50 (46.3) | 28 (36.4) | 0.18 |

| Prior transfusion, n (%) | 140 (75.7) | 83 (76.9) | 57 (74.0) | 0.66 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 24 (13.0) | 13 (12.0) | 11 (14.3) | 0.65 |

Values are medians (interquartile ranges) or n (%). Comparisons were made between male and females using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous measures or Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables. BMI, body mass index; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MUAC, middle upper arm circumference.

Disease Severity at Admission and In-Hospital Medication Disaggregated by Sex

No differences by sex were seen in clinical characteristics at admission including fever, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory distress, organomegaly, or severe anemia. A higher proportion of female children presented with vomiting (P = 0.04), but there were no differences by sex in other parameters of hypovolemia, including hypotension, diarrhea, or inability to drink. There were no differences in infection status or pain (score, location, or duration) by sex (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics associated with disease severity on admission

| Combined (n = 185) |

Male (n = 108) |

Female (n = 77) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics on admission | ||||

| Temperature, °C | 37.1 (36.7, 37.8) | 37.1 (36.7, 38.0) | 37.1 (36.6, 37.5) | 0.21 |

| Fever (axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C), n (%) | 64 (34.6) | 40 (37.0) | 24 (31.2) | 0.41 |

| Temperature ≥ 38.5 °C | 24 (13.0) | 18 (16.7) | 6 (7.8) | 0.08 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 108 (98, 121) | 108 (99, 123) | 109 (96, 120) | 0.56 |

| Respiratory rate, beats/min | 29 (24, 36) | 29 (24, 36) | 30 (24, 36) | 0.93 |

| Altered consciousness, n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.9) | 0.31 |

| Difficulty breathing, n (%) | 40 (21.6) | 26 (24.1) | 14 (18.2) | 0.34 |

| Deep breathing, n (%) | 32 (17.3) | 18 (16.7) | 14 (18.2) | 0.79 |

| Blood pressure category, n (%) | ||||

| Hypotensive | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.3) | 0.75 |

| Normotensive | 149 (80.5) | 89 (82.4) | 60 (77.9) | |

| Hypertension | 34 (18.4) | 18 (16.7) | 16 (20.8) | |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 4 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0.14 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 13 (7.0) | 4 (3.7) | 9 (11.7) | 0.04 |

| Unable to drink/breastfeed, n (%) | 8 (4.3) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (6.5) | 0.22 |

| Severe anemia, Hb < 8.0 g/dL, n (%) | 131 (70.8) | 74 (68.5) | 57 (74.0) | 0.42 |

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 18 (9.7) | 10 (9.3) | 8 (10.4) | 0.89 |

| Hepatomegaly, n (%) | 78 (42.2) | 47 (43.5) | 31 (40.3) | 0.80 |

| Tender hepatomegaly, n (%) | 38 (20.5) | 20 (18.5) | 18 (23.4) | 0.60 |

| Reduce urine output, n (%) | 15 (8.1) | 6 (5.6) | 9 (11.7) | 0.13 |

| Tea colored urine, n (%) | 79 (42.7) | 40 (37.0) | 39 (50.7) | 0.07 |

| Infection status | ||||

| Sepsis, n (%) | 19 (10.3) | 13 (12.0) | 6 (7.8) | 0.35 |

| Malaria, n (%) | 17 (9.6) | 10 (9.9) | 7 (9.2) | 0.88 |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.7) | >0.99 |

| Acute infection, n (%) | 38 (20.5) | 23 (21.3) | 15 (19.5) | 0.76 |

| Pain assessment | ||||

| Pain score, median (IQR) | ||||

| FLACC-R, ≤3 yr, n = 18 | 4 (4, 8) | 5 (4, 8) | 4 (3.5, 7) | 0.52 |

| Wong-Baker, >3–7 yr, n = 89 | 6 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 8) | 0.55 |

| Numeric scale, ≥8 yr, n = 78 | 6 (4, 8) | 5.5 (4, 8) | 6 (5, 8) | 0.10 |

| Overall | 6 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 8) | 0.69 |

| Location of pain | ||||

| Chest | 64 (34.6) | 42 (38.9) | 22 (28.6) | 0.15 |

| Abdomen | 77 (41.6) | 46 (42.6) | 31 (40.3) | 0.75 |

| Back | 55 (29.7) | 36 (33.3) | 19 (24.7) | 0.20 |

| Lower limb | 120 (64.9) | 66 (61.1) | 54 (70.1) | 0.21 |

| Upper limb | 56 (30.3) | 28 (25.9) | 28 (36.4) | 0.13 |

| Other | 7 (3.8) | 5 (4.6) | 2 (2.6) | 0.70 |

| Duration of pain, days | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 0.35 |

Values are medians [interquartile ranges (IQE)] or n (%). Comparisons were made between male and females using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous measures or Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables.

Males and females received the same access to analgesics, antibiotics, antimalarial medications, and fluid resuscitation (Table 3). Male and female children also experienced similar exposure to nephrotoxic medications while in hospital. Although there were no differences in the incidence of severe anemia or hemoglobin levels by sex at admission, females were more likely to receive a transfusion in the hospital, with 29.9% of females receiving a transfusion compared with 17.6% of males (P = 0.049) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Medication use in hospital based on sex

| Combined (n = 185) |

Male (n = 108) |

Female (n = 77) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | ||||

| Paracetamol, n (%) | 172 (93.0) | 101 (93.5) | 71 (92.2) | 0.73 |

| Ibuprofen, n (%) | 155 (83.8) | 91 (84.3) | 64 (83.1) | 0.84 |

| Diclofenac, n (%) | 19 (10.3) | 10 (9.3) | 9 (11.7) | 0.59 |

| NSAIDa, n (%) | 160 (86.5) | 94 (87.0) | 66 (85.7) | 0.80 |

| Opioidsb, n (%) | 163 (88.1) | 94 (87.0) | 69 (89.6) | 0.59 |

| Antibiotics | ||||

| Gentamicin, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| Azithromycin, n (%) | 54 (29.2) | 35 (32.4) | 19 (24.7) | 0.25 |

| Ceftriaxone, n (%) | 125 (67.6) | 78 (72.2) | 47 (61.0) | 0.11 |

| Antimalarial medications | ||||

| Artesunate or artemether-lumefantrine, n (%) | 14 (7.6) | 6 (5.6) | 8 (10.4) | 0.22 |

| Intravenous fluids or transfusion | ||||

| Normal saline, n (%) | 149 (80.5) | 88 (81.5) | 61 (79.2) | 0.85 |

| Ringer’s lactate, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Bicarbonate, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Albumin, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Transfusion, n (%) | 42 (22.7) | 19 (17.6) | 23 (29.9) | 0.049 |

| Nephrotoxic medications | ||||

| Any nephrotoxic medicationc, n (%) | 160 (86.5) | 94 (87.0) | 66 (85.7) | 0.80 |

| Number of nephrotoxic medicationsd, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 25 (13.5) | 14 (13.0) | 11 (14.3) | 0.88 |

| 1 | 145 (78.4) | 86 (79.6) | 59 (76.6) | |

| 2 | 15 (8.1) | 8 (7.4) | 7 (9.1) |

Values are n (%). Differences between groups were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact, as appropriate.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) defined as having received ibuprofen or diclofenac.

Opioid medication defined as having received morphine, codeine, fentanyl, or tramadol.

Nephrotoxic medication defined as having received an NSAID (ibuprofen or diclofenac) or gentamicin.

Number of nephrotoxic medications administered (sum of ibuprofen, diclofenac, or gentamicin).

Measures of Kidney Function, AKI, and Liver Function Disaggregated by Sex

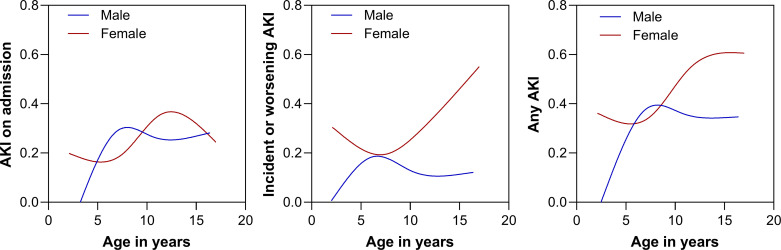

On admission, the incidence of AKI was comparable between females and males with the risk of low AKI in younger males and peaking among males between 7 and 8 yr of age, whereas the risk in females peaked at around 13 yr (Fig. 1). Although there were no differences in AKI on admission, females were more likely to develop incident or worsening AKI (P = 0.026) and more likely to progress to a more severe stage of AKI during hospitalization (P = 0.02) compared with male children (Table 4). The relationship between increased risk of incident or worsening AKI among females was most evident among adolescents with the risk increasing with age among females and decreasing among males in adolescence (Fig. 1). These relationships remained significant even after adjusting for risk factors for AKI in the context of SCA and VOC (Table 5), including age, vomiting, duration of pain, severe anemia, acute infection, tender hepatomegaly, and exposure to nephrotoxic medications. These effects were consistent in a sensitivity analysis where children with only a single creatinine measure were excluded.

Figure 1.

Risk of acute kidney injury by age and sex. Line graphs depict the frequency of acute kidney injury (AKI) on admission (left), the development of incident or worsening AKI (middle), or AKI at any point (right) among males (blue) and females (red). The lines represent a smoothing spline with four knots.

Table 4.

Laboratory measures of renal function and liver function disaggregated by sex

| Combined (n = 185) | Male (n = 108) | Female (n = 77) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | ||||

| AKI during hospitalization, n (%) | 67 (36.2) | 32 (29.6) | 35 (45.5) | 0.03 |

| AKI stage during hospitalization, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 25 (13.5) | 16 (14.8) | 9 (11.7) | 0.02 |

| 2 | 18 (9.7) | 8 (7.4) | 10 (13.0) | |

| 3 | 24 (13.0) | 8 (7.4) | 16 (20.8) | |

| AKI on admission, n (%) | 43 (23.2) | 23 (21.3) | 20 (26.0) | 0.46 |

| AKI stage on admission, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 21 (11.4) | 13 (12.0) | 8 (10.4) | 0.19 |

| 2 | 11 (6.0) | 7 (6.5) | 4 (5.2) | |

| 3 | 11 (6.0) | 3 (2.8) | 8 (10.4) | |

| Incident or worsening AKI, n (%) | 28 (19.2) | 11 (12.6) | 17 (28.8) | 0.02 |

| Creatinine and eGFR | ||||

| Admission creatinine, mg/dL | 0.30 (0.19, 0.40) | 0.30 (0.19, 0.40) | 0.30 (0.20, 0.40) | 0.03 |

| Baseline creatinine, mg/dL | 0.20 (0.19, 0.30) | 0.19 (0.19, 0.30) | 0.20 (0.19, 0.30) | 0.004 |

| Maximum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.30 (0.20, 0.50) | 0.30 (0.20, 0.40) | 0.30 (0.20, 0.70) | 0.006 |

| Admission eGFR (SCr), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 185 (137, 228) | 186 (151, 228) | 179 (107, 227) | 0.15 |

| Admission eGFR (Cys C), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 86 (68, 107) | 91 (70, 113) | 81 (63, 105) | 0.03 |

| Admission eGFR (SCr + Cys C), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 133 (104, 160) | 145 (109, 165) | 119 (83, 144) | <0.001 |

| Lowest eGFR (SCr), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 167 (113, 211) | 171 (133, 212) | 153 (67, 198) | 0.03 |

| Discharge eGFR (SCr), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 211 (162, 255) | 223 (177, 259) | 198 (120, 240) | 0.009 |

| Other renal function measures | ||||

| BUN, mg/dL | 4.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (3.0, 5.5) | 4.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 0.22 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 138 (135, 140) | 137 (135, 140) | 138 (136, 140) | 0.46 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 3.8 (3.6, 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6, 4.1) | 3.8 (3.5, 4.1) | 0.93 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | 105 (102, 108) | 105 (102, 107) | 105 (103, 108) | 0.16 |

| Total CO2, mg/dL | 21 (19, 22) | 21 (19, 23) | 20 (18, 21) | 0.01 |

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 0.81 (0.64, 1.05) | 0.76 (0.61, 1.01) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | 0.03 |

| Urine NGALa, ng/mL | 9.8 (5.0, 33.5) | 8.4 (5.0, 17.9) | 17.7 (5.0, 62.2) | 0.003 |

| Urine NGAL:Cra, ng/mmol | 3.8 (2.1, 9.7) | 3.4 (1.8, 5.5) | 5.8 (2.7, 26.9) | 0.001 |

| Liver function | ||||

| Aspartate transaminase, U/L | 54 (36, 90) | 50 (34, 79) | 58 (39, 102) | 0.13 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 22 (14, 35) | 20.5 (13.5, 29.1) | 24.0 (15.0, 49.3) | 0.08 |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase, IU/L | 30.6 (20.1, 60.5) | 29.2 (18.9, 53.2) | 36.7 (20.2, 62.2) | 0.17 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 38.9 (35.3, 42.9) | 39.5 (35.8, 43.1) | 37.8 (34.7, 42.8) | 0.20 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.93 (1.02, 3.87) | 1.69 (0.99, 3.34) | 2.40 (1.21, 4.61) | 0.045 |

| Conjugated bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.67 (0.47, 1.39) | 0.61 (0.46, 1.04) | 0.81 (0.50, 2.38) | 0.02 |

| Complete blood count | ||||

| WBC count × 103/μL | 22.6 (16.7, 33.4) | 22.4 (16.7, 33.1) | 23.7 (16.8, 35.2) | 0.88 |

| Neutrophil count × 103/μL | 12.1 (8.3, 17.2) | 12.1 (8.3, 17.4) | 12.0 (8.2, 17.1) | 0.83 |

| Platelet count × 103/μL | 418 (306, 525) | 429 (334, 542) | 383 (279, 511) | 0.12 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7.2 (6.3, 8.2) | 7.4 (6.2, 8.3) | 7.0 (6.3, 8.0) | 0.52 |

| RBC count × 106/mm3 | 2.4 (2.1, 2.9) | 2.5 (2.1, 3.1) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.6) | 0.10 |

| Hematocrit % | 22.2 (19.1, 25.4) | 22.7 (19.0, 26.1) | 21.8 (19.8, 24.3) | 0.30 |

| Urinalysis | ||||

| Albumin-to-creatinine ratioa, n (%) | ||||

| <3 | 105 (60.0) | 64 (62.8) | 41 (56.2) | 0.12 |

| 3–30 | 55 (31.4) | 33 (32.4) | 22 (30.1) | |

| >30 | 15 (8.6) | 5 (4.9) | 10 (13.7) | |

| Hematuria by dipstick, n (%)b | 14 (7.6) | 3 (2.8) | 11 (14.3) | 0.004 |

| ≤5 yr | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.07 |

| >5 to ≤10 yr | 4 (5.5) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.8) | 0.33 |

| >10 yr | 8 (10.5) | 2 (4.7) | 6 (18.2) | 0.07 |

| Proteinuria by dipstick, n (%) | 28 (15.1) | 13 (12.0) | 15 (19.5) | 0.16 |

| Bilirubinuria by dipstick, n (%) | 16 (8.7) | 4 (3.7) | 12 (15.6) | 0.005 |

Data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges) or n (%). Comparisons were made across male and females by the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables or Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate.

AKI, acute kidney injury; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Urine results available for 182 children for NGAL, 175 for urine-to-albumin creatinine ratio, and 173 children for NGAL normalized to creatinine.

Hematuria broken down by age because differences in group > 10 yr could be accounted for by menstrual cycle in females.

Table 5.

Multivariable regression analyses of AKI risk in females hospitalized with sickle cell anemia and a vaso-occlusive crisis

| Entire Cohort |

Sensitivity Analysis2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI)a | P Value | aRR (95% CI) | P Value |

| AKI on admission | 1.22 (0.72, 2.06) | 1.00 (0.58, 1.74) | >0.99 | 1.00 (0.56, 1.79) | 0.99 |

| AKI during hospitalization | 1.53 (1.05, 2.25) | 1.35 (0.92, 1.98) | 0.13 | 1.39 (0.94, 2.05) | 0.10 |

| AKI stage during hospitalizationc | 1.93 (1.25, 2.97) | 1.74 (1.11, 2.72) | 0.02 | 1.78 (1.13, 2.79) | 0.01 |

| Incident or worsening AKI | 2.28 (1.15, 4.52) | 2.10 (1.01, 4.39) | 0.048 | 2.20 (1.07, 4.53) | 0.03 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; aRR, adjusted risk ratio (RR); CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for risk factor for AKI in sickle cell anemia and vaso-occlusive crisis, including predisposition for hypovolemia (vomiting), age in years (spline with knot at 7 yr), duration of pain, severe anemia, acute infection, tender hepatomegaly, and exposure to nephrotoxic medications. Estimates were obtained using Poisson regression with robust estimates to generate the 95% CI.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted including only children with multiple creatinine measures to estimate baseline creatinine (n = 6 participants excluded with only a single creatinine measure).

Estimates represent the incident rate ratio and adjusted incident rate ratio.

Although there were no differences in AKI at admission, female children had altered markers of kidney function at admission including higher creatinine (P = 0.03) and a lower estimated GFR when using cystatin C-based estimating equations with or without creatinine (P < 0.001 or P = 0.03, respectively) as well as a higher urine NGAL concentration at admission with or without normalization for urine creatinine (P = 0.001 and P = 0.003, respectively) compared with male children. Female children also had elevated total (P = 0.045) and conjugated bilirubin at admission (P = 0.02) compared with male children and higher rates of hematuria at admission (P = 0.004) even after stratifying by age to account for the potential contribution of menstruation (Table 4).

Mortality Differences by Sex

As previously described, all study deaths occurred in females. Overall, there were six deaths in the cohort with a mortality of 0% in males compared to 7.8% in females (P = 0.005). Of the children who died, 83.3% (n = 5/6) had AKI and the mean age was 11.0 yr (standard deviation = 3.4). Among study deaths with AKI, one participant had a stroke, one participant had severe malaria, two participants had acute chest syndrome, and one participant had multiple organ failure. There was one participant without AKI who died of cardiopulmonary failure.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of pediatric patients with SCA admitted to the hospital with VOC, we observed higher post-admission incidence of AKI and higher rates of worsening AKI in female children. We also observed altered markers of kidney function in female children with higher creatinine measures over hospitalization and an increase in urine NGAL as a sign of structural injury to the kidney. Furthermore, females had higher rates of vomiting at admission, increases in conjugated bilirubin, were more likely to receive a transfusion while hospitalized, and had a higher frequency of hematuria compared with male children, which could reflect a predisposition to volume depletion and increased hemolysis leading to more severe AKI in female children with SCA. These findings suggest sex differences in children with SCA in the post-admission incidence of worsening of AKI.

No differences between male and female participants were observed in clinical characteristics at admission (e.g., fever, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory distress, organomegaly, severe anemia, or diarrhea) or in access to analgesics, antibiotics, antimalarial medications, fluid resuscitation, or exposure to nephrotoxic medications. Therefore, in this cohort of children with SCA admitted with VOC, differences in disease severity at admission or treatment received in hospital, which could be reflections of societal gender norms in the timing of access to or provision of care, were unlikely to be a cause of sex differences in incident or worsening of AKI. Females were more likely to receive a transfusion during hospitalization compared with males but with increases in hematuria and markers of hemolysis, this likely reflects increased hemolysis among females.

Sickle cell disease is an autosomal recessive disorder and, therefore, is not inherited via sex chromosomes, making a genetic cause for sex differences less likely. In adults, higher mortality has been reported in males with SCA compared with females (22). Previous research has reported higher pain crisis frequency in male pediatric patients as well as severe infectious and cardiovascular complications (8). The frequency of pain crisis was not assessed in this cohort, precluding a clear comparison. It is possible that sex differences are age dependent as previous research was conducted in adult populations. Furthermore, sex hormones fluctuate over a life course and there is some evidence that they may also be playing a role in sex differences in SCA outcomes. Females had the highest risk of developing incident or worsening AKI in adolescence with a linear increase in AKI risk with increasing age, which may reflect the onset of puberty and increases in sex hormones (Fig. 1).

No research to date has reported an increased incidence of AKI in female pediatric patients with SCA; however, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine sex differences in this age group. AKI is recognized as a complication of SCA in children; however, previous research is largely based in high-resource settings (7). Independent of SCA, data suggest that women have a lower incidence of AKI due to acute insults compared with men, with women having a survival advantage in community-acquired AKI and sepsis-associated AKI compared with men with some of the reduced risk of AKI attributed to the kidney protective action of estrogen (11, 21). The results reported here suggest that young females have a higher risk of AKI associated with SCA with the risk increasing during adolescence when estrogen levels are expected to increase. As this was an observational study design, it was not possible to closely examine the pathobiology leading to the higher incidence and worsening of AKI in female patients with SCA and VOC. However, the observation of lower eGFR at admission, and higher levels of creatinine and NGAL, could reflect more severe underlying kidney disease with tubular injury in female patients. Underlying kidney pathology is common in children with SCA and accurate AKI staging on admission in the context of an unknown incidence of chronic kidney disease in the population may be challenging. Current literature suggests that episodes of AKI contribute to sickle cell nephropathy via VOC, volume depletion, NSAID exposure, and heme toxicity (23). Elevated bilirubin and higher rates of hematuria in female patients may be indicators of increased hemolysis, resulting in more severe AKI. The higher rates of vomiting among females may have predisposed them to an increased risk of hypovolemia, which in turn predisposes them to sickling of red blood cells (RBCs) and hemolysis. Female sex hormones have been associated with increased risk of nausea and vomiting and may have contributed to the increased risk of AKI in this patient population (24). However, even after controlling for these traditional risk factors for AKI in SCA and VOC (e.g., vomiting, severe anemia, and nephrotoxic medications), the female sex remained significantly associated with an increased risk for more severe AKI and incident/worsening AKI, indicating that differences in these risk factors do not fully explain the sex disparity. Additional sex-disaggregated analyses of children with SCA and AKI are required to validate and extend these findings and identify additional pathways that could be contributing to the sex disparity in AKI outcomes in children with SCA.

The incidence of SCA is highest in tropical areas, including sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Middle East, which are often also resource-constrained settings. In low-resource settings, access to early SCA diagnosis and treatment can be severely restricted. The vast majority, an estimated 80%, of children born with SCA annually reside in Africa (1, 2). Previous research from our laboratory has reported that AKI is a common complication in children with SCA admitted to hospital with VOC (9). Multiple risk factors for AKI are common in children with SCA admitted to hospital, including exposure to nephrotoxic medications to manage pain (6). Our data suggest that despite equal exposure to many of these risk factors, and even after controlling for them, female children are still at higher risk for more severe and worsening AKI during hospitalization compared with male children. Current estimates suggest up to 17% of children hospitalized with VOC develop AKI in high-resource settings (5, 6, 23, 25, 26). Data on AKI in pediatric populations are limited in LMICs; however, research from this study cohort suggests that the rate of AKI may be higher in children with SCA living in LMICs (at 36.3%) (9). More research in this field is urgently needed to determine how the global disease burden is compounded by a lack of access to diagnosis and renal replacement therapy (13). High exposure to risk factors for AKI in LMICs, including common infections, preventable conditions, and inherited conditions such as SCA, could place many children, especially female children, at risk of developing life-long consequences from treatable and reversible cases of AKI (13).

This study was a secondary analysis of an observational study examining AKI in children with SCA hospitalized with VOC; therefore, the study was not designed as a sex-stratified analysis and the sample size may be insufficient to identify some differences in clinical parameters associated with sex. Moreover, sex differences, or a lack thereof, in outcomes resulting from sex-based biases in clinical care are often the result of immediate cultural ecosystems (27). Therefore, the results may be of limited value in extrapolating beyond this cohort. Additional research is needed to validate and expand upon the results reported in this cohort. Assessment of AKI in this study was based on serum creatinine as urine output was not available and the lowest creatinine over hospitalization was used as baseline as prior creatinine measures were not available for any participant. For six participants, only a single creatinine was measured and population-based estimates were used for baseline, but the effects were robust when excluding those participants. It is worth noting that diagnosis of AKI in children with SCA based on creatinine can be challenging as glomerular hyperfiltration and increased tubular secretion of creatinine impact creatinine readouts (7). However, using serial creatinine measures, we were able to overcome this limitation to some extent. Additional research is required to establish alternative biomarkers of AKI in children with SCA, in particular biomarkers that are appropriate for use in resource-constrained settings, like urine NGAL. This study benefits from a well-categorized cohort of children with detailed clinical data in a region with a high burden of SCA. The comprehensive data set allowed for the examination of multiple clinical parameters in association with sex, SCA, VOC, and AKI.

Sex and gender are established determinants of health access and outcomes in children and adolescents in LMICs (28–31). A growing body of research is identifying sex differences in the clinical outcomes of inherited disease. However, most of this work is being conducted in high-resource settings. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine sex differences in clinical outcomes associated with AKI in children with SCA and VOC. A better understanding of sex differences in the clinical outcomes of SCA and AKI will increase our understanding of underlying pathophysiology and create new avenues for personalized care.

Perspectives and Significance

Here, we report an increase in incident or worsening AKI among female pediatric patients with sickle cell disease in Uganda. These findings were independent of age and disease severity and were associated with differences in multiple biological indicators of AKI, including increases in urine NGAL. Sex differences in AKI risk were notably higher in adolescence suggesting that sex hormones may contribute to increased AKI risk in this susceptible population. Additional research in the space is required to better understand the pathobiology of sex impacts on clinical outcomes for children with SCA and AKI.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Source data can be found at the following link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/REGLDZ (Harvard Dataverse, V2).

GRANTS

This work was supported by the following: National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), Grant D43TW010132 (to A.B.); NIH, FIC, NHLBI, Grant D43TW009345 (to A.B.); and NIH, FIC, United States Department of State’s Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy, and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Grant 1R25TW011213 (to A.B.). S.K.N. was supported by FIC Grant D43TW010928.

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L.C. and A.B. conceived and designed the study; A.W., C.R.M., and A.L.C. analyzed the data; S.K.N., D.E.S., A.L.C., and A.B. interpreted the study results; A.W. and C.R.M. drafted the manuscript; A.W., C.R.M., S.K.N., D.E.S., A.L.C., and A.B. edited and revised the manuscript; A.W., C.R.M., S.K.N., D.E.S., A.L.C., and A.B. approved the final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the children and caretakers who participated in the study. The authors are also grateful to the medical officers, nurses, laboratory team, and all staff who were involved in this study and provided support to the study activities. BioRender.com was used to create the graphical abstract.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chakravorty S, Williams TN. Sickle cell disease: a neglected chronic disease of increasing global health importance. Arch Dis Child 100: 48–53, 2015. doi: 10.1136/archdisschild-2013-303773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGann PT, Hernandez AG, Ware RE. Sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa: advancing the clinical paradigm through partnerships and research. Blood 129: 155–161, 2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-702324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodigari F, Brugnera G, Colombatti R. Health-related quality of life in hemoglobinopathies: a systematic review from a global perspective. Front Pediatr 10: 886674, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.886674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lelo PVM, Kitetele FN, Akele CE, Sam DL, Boivin MJ, Kashala-Abotnes E. Caregivers' perspective on the psychological burden of living with children affected by sickle cell disease in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Children (Basel) 10: 261, 2023. doi: 10.3390/children10020261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCormick M, Richardson T, Warady BA, Novelli EM, Kalpatthi R. Acute kidney injury in paediatric patients with sickle cell disease is associated with increased morbidity and resource utilization. Br J Haematol 189: 559–565, 2020. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baddam S, Aban I, Hilliard L, Howard T, Askenazi D, Lebensburger JD. Acute kidney injury during a pediatric sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain crisis. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 1451–1456, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3623-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nath KA, Hebbel RP. Sickle cell disease: renal manifestations and mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 161–171, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ceglie G, Di Mauro M, Tarissi De Jacobis I, de Gennaro F, Quaranta M, Baronci C, Villani A, Palumbo G. Gender-related differences in sickle cell disease in a pediatric cohort: a single-center retrospective study. Front Mol Biosci 6: 140, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Batte A, Menon S, Ssenkusu J, Kiguli S, Kalyesubula R, Lubega J, Mutebi EI, Opoka RO, John CC, Starr MC, Conroy AL. Acute kidney injury in hospitalized children with sickle cell anemia. BMC Nephrol 23: 110, 2022. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wyld MLR, Mata NL, Viecelli A, Swaminathan R, O'Sullivan KM, O'Lone E, Rowlandson M, Francis A, Wyburn K, Webster AC. Sex-based differences in risk factors and complications of chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 42: 153–169, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neugarten J, Golestaneh L. Sex differences in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 42: 208–218, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carrero JJ, Hecking M, Chesnaye NC, Jager KJ. Sex and gender disparities in the epidemiology and outcomes of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 14: 151–164, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCulloch M, Luyckx VA, Cullis B, Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO, Yap HK, Feehally J, Smoyer WE. Challenges of access to kidney care for children in low-resource settings. Nat Rev Nephrol 17: 33–45, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kasztan M, Aban I, Hande SP, Pollock DM, Lebensburger JD. Sex differences in the trajectory of glomerular filtration rate in pediatric and murine sickle cell anemia. Blood Adv 4: 263–265, 2020. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masese RV, Bulgin D, Knisely MR, Preiss L, Stevenson E, Hankins JS, Treadwell MJ, King AA, Gordeuk VR, Kanter J, Gibson R, Glassberg JA, Tanabe P, Shah N; Sickle Cell Disease Implementation C. Sex-based differences in the manifestations and complications of sickle cell disease: report from the sickle cell disease implementation consortium. PLoS One 16: e0258638, 2021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Voepel-Lewis T, Zanotti J, Dammeyer JA, Merkel S. Reliability and validity of the face, legs, activity, cry, consolability behavioral tool in assessing acute pain in critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care 19: 55–61, 2010. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young KD. Assessment of acute pain in children. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 18: 235–241, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2017.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Opoka RO, Ndugwa CM, Latham TS, Lane A, Hume HA, Kasirye P, Hodges JS, Ware RE, John CC. Novel use of hydroxyurea in an African Region with Malaria (NOHARM): a trial for children with sickle cell anemia. Blood 130: 2585–2593, 2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-788935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, de Ferranti SD, Dionne JM, Falkner B, Flinn SK, Gidding SS, Goodwin C, Leu MG, Powers ME, Rea C, Samuels J, Simasek M, Thaker VV, Urbina EM; Subcommittee on Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 140: e20171904, 2017. [Erratum in Pediatrics 140: e20173035, 2017, and in Pediatrics 142: e20181739, 2018]. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R&D Systems. Product Datasheet. Human Cystatin C Immunoassay [Online]. https://www.rndsystems.com/products/human-cystatin-c-quantikine-elisa-kit_dsctc0 [Accessed 26 July 2024].

- 21. Dahiya A, Pannu N, Soranno DE. Sex as a biological variable in acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 29: 529–533, 2023. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000001091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, Klug PP. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med 330: 1639–1644, 1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mammen C, Bissonnette ML, Matsell DG. Acute kidney injury in children with sickle cell disease-compounding a chronic problem. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 1287–1291, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matchock RL, Levine ME, Gianaros PJ, Stern RM. Susceptibility to nausea and motion sickness as a function of the menstrual cycle. Womens Health Issues 18: 328–335, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Audard V, Homs S, Habibi A, Galacteros F, Bartolucci P, Godeau B, Renaud B, Levy Y, Grimbert P, Lang P, Brun-Buisson C, Brochard L, Schortgen F, Maitre B, Mekontso Dessap A. Acute kidney injury in sickle patients with painful crisis or acute chest syndrome and its relation to pulmonary hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2524–2529, 2010. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lebensburger JD, Palabindela P, Howard TH, Feig DI, Aban I, Askenazi DJ. Prevalence of acute kidney injury during pediatric admissions for acute chest syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 31: 1363–1368, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merdji H, Long MT, Ostermann M, Herridge M, Myatra SN, De Rosa S, Metaxa V, Kotfis K, Robba C, De Jong A, Helms J, Gebhard CE. Sex and gender differences in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 49: 1155–1167, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet 362: 233–241, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khera R, Jain S, Lodha R, Ramakrishnan S. Gender bias in child care and child health: global patterns. Arch Dis Child 99: 369–374, 2014. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calu Costa J, Wehrmeister FC, Barros AJ, Victora CG. Gender bias in careseeking practices in 57 low- and middle-income countries. J Glob Health 7: 010418, 2017. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Starr MC, Barreto E, Charlton J, Vega M, Brophy PD, Ray Bignall ON, 2nd, Sutherland SM, Menon S, Devarajan P, Akcan Arikan A, Basu R, Goldstein S, Soranno DE; ADQI 26 workgroup. Advances in pediatric acute kidney injury pathobiology: a report from the 26th acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) conference. Pediatr Nephrol 39: 941–953, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s00467-023-06154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Source data can be found at the following link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/REGLDZ (Harvard Dataverse, V2).