Introduction

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is a progressive dysfunction of sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves in the feet and hands characterized by loss of proprioception, pain and temperature sensations, decreased joint mobility, and asymmetric muscle atrophy. Although commonly associated with diabetes, PN also affects 25% to 32% of older adults without diabetes (1). PN predisposes to lower extremity weakness, gait abnormalities, and an increased risk of falls in persons with diabetes. However, associations of PN with lower extremity function in older adults without diabetes are not well-described. We examined associations of PN with lower extremity physical performance, including gait speed, in a diverse community-based cohort of older adults with and without diabetes.

Methods

The study cohort comprised participants in the prospective longitudinal Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study who completed ARIC study visit 6 (2016–2017), did not use walking aids during gait testing, and had complete demographic, clinical, PN and lower extremity functional testing data (see Supplemental Materials) (5).

PN was defined as plantar foot sensory deficits by Semmes-Weinstein 10g monofilament test (1). Diabetes was defined as doctor diagnosis, antihyperglycemic medication use, and/or HbA1c > 6.5%. Gait speed was collected by usual pace 4-meter walk test on a flat, even surface. Gait speed was evaluated as a continuous variable (meaningful absolute difference >0.05m/s) and further categorized as normal (≥1m/s) or slow (<1m/s) based on commonly used cut points (6,7). Lower extremity function was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which evaluates gait speed, standing balance, and repeated chair stands to calculate a composite score of 0 to 12 (6). Higher scores represent better lower extremity function: ≥10 indicates little/no lower extremity functional impairment, 6 to 9 mild impairment, and < 6 moderate/severe impairment (6).

Associations of PN with continuous gait speed and categorical slow gait were estimated using multivariable linear and logistic regression models. Multinomial logistic regression models estimated associations of PN with SPPB score categories. All regression analyses were performed using a sequential modelling approach based on demographic and clinical covariates of interest selected a priori based on demonstrated associations with PN and gait speed Analyses were repeated in subgroups stratified by diabetes status.

Results

Of the 2,786 ARIC participants included in the study, 32.1% (N=894) were classified as having PN. Adults with PN tended to be older, more frequently male, and had a higher prevalence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics according to peripheral neuropathy (PN) status, the ARIC Study (Visit 6, 2016–2017)

| No PN | PN | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N | 1892 | 894 |

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 78.5 (4.2) | 79.9 (4.7) |

| Female sex | 1238 (65) | 346 (39) |

| Black race | 332 (18) | 170 (19) |

| Diabetes* | 562 (30) | 303 (34) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| < 25 | 573 (30) | 246 (28) |

| 25 to <30 | 767 (41) | 332 (37) |

| ≥30 | 552 (29) | 316 (35) |

| Prevalent CVD† | 314 (17) | 204 (23) |

| Cognitive status | ||

| Normal | 1536 (81) | 654 (73) |

| MCI/dementia | 356 (19) | 240 (27) |

All data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified; SD=standard deviation; CVD=cardiovascular disease; MCI=mild cognitive impairment

self-reported doctor diagnosis, antihyperglycemic medication, or A1c ≥ 6.5%

history of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, or cardiac procedural intervention, hospitalization for heart failure, and/or definite or probable ischemic stroke

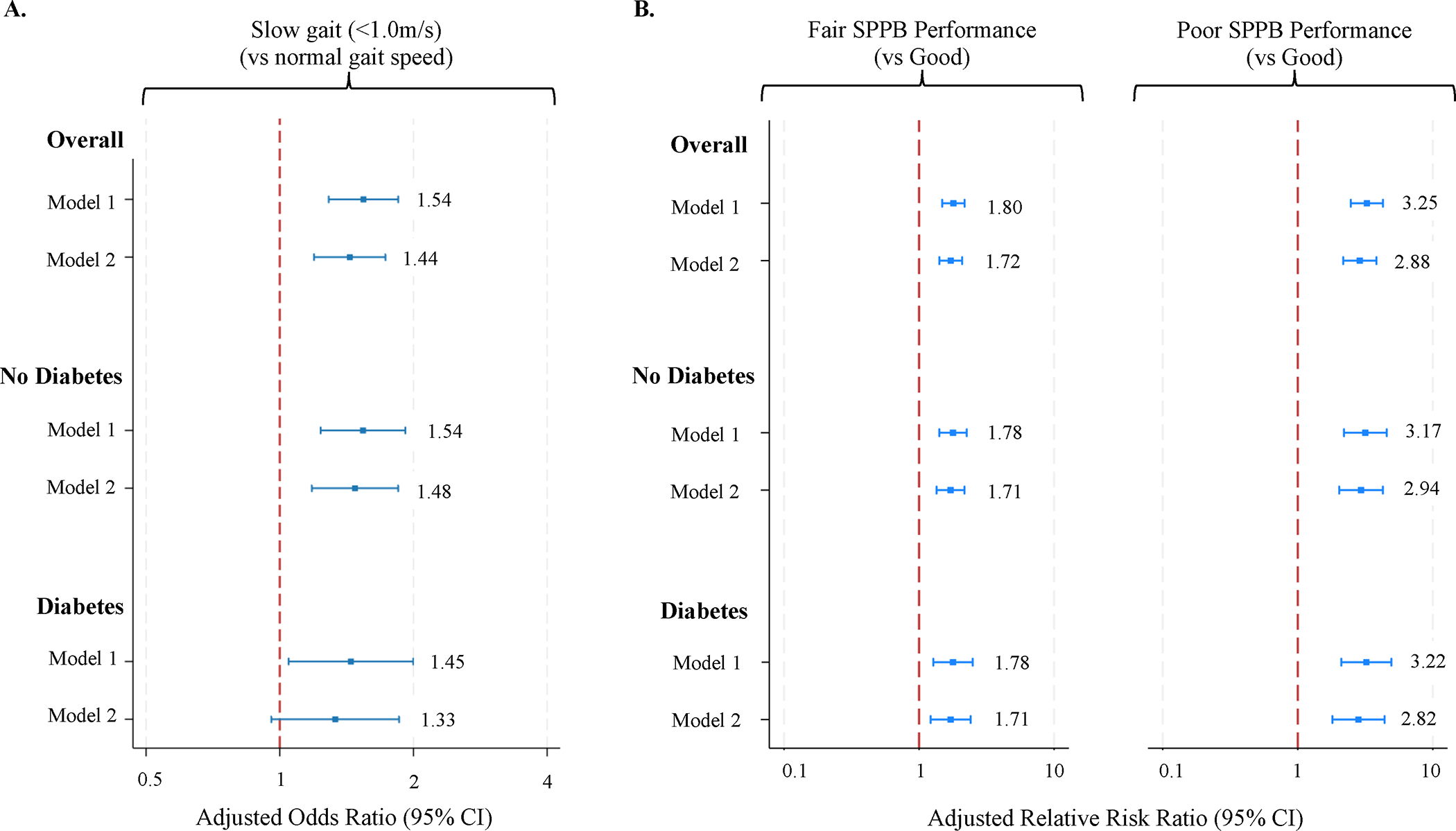

Adults with PN had slower mean gait speed and a higher prevalence of slow gait compared to adults without PN (63.4% vs 55.0%, P<0.001, see Supplemental Materials). After adjusting for demographics and comorbidities, PN remained associated with slower gait speed (β −0.04 m/s, 95% CI −0.05, −0.02 m/s) and higher odds of slow gait (aOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.19, 1.73). Findings were similar in subgroups stratified by diabetes status (P>0.05 for interactions, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Minimally and maximally adjusted* associations of peripheral neuropathy (PN) with relative risk of slow gait (A) and impaired short physical performance battery (SPPB) testing (B).

*Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, race; Model 2: Model 1 + body mass index, diabetes status (only in overall sample), prevalent cardiovascular disease, cognitive status; reported associations of PN and slow gait (A) reflect logistic regression; associations of PN and SPPB (B) reflect multinomial logistic regression

Median SPPB scores were lower in participants with PN compared to participants without PN (9.0 [IQR 7.0–11.0] vs 10.0 [9.0–11.0], P<0.001, see Supplemental Materials). In adjusted multinomial logistic regression models, PN was associated with increased risk of mild and moderate/severe impairment by composite SPPB scores, and these associations were similar regardless of diabetes status (P>0.05 for interaction, Figure 1).

Discussion

This cross-sectional analysis of community-dwelling older adults demonstrated that PN is associated with slow gait and impaired lower extremity physical performance in older adults both with and without diabetes. To our knowledge, our study is the largest to date to examine the associations of PN and lower extremity function in community-dwelling older adults and to directly compare these associations in adults with and without diabetes. Our results confirm that the relationship between PN and slow gait persists into advanced age, even accounting for normal declines in gait speed among healthy adults (8), and provide evidence that the cross-sectional associations of PN, slow gait, and impaired lower extremity function are similar regardless of diabetes status.

Both slow gait and poor SPPB function are associated with increased risk of falls, loss of independence, and mortality among older adults (9,10). Annual screening for PN in adults with diabetes is recommended by multiple professional societies, but peripheral sensation is not routinely tested in older adults without diabetes. The associations of PN with impaired lower extremity function in this group suggest that screening for PN may be a strategy to identify individuals at increased risk of adverse outcomes. Our findings support monofilament testing as a useful and feasible tool to screen for gait dysfunction and impaired lower extremity performance in older adults without diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Dr. McDermott is supported by NHLBI T32HL007024; Dr. Selvin is supported by NHLBI K24 HL152440; Dr. Hicks is supported by NIDDK K23DK124515; the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (75N92022D00001, 75N92022D00002, 75N92022D00003, 75N92022D00004, 75N92022D00005). The ARIC Neurocognitive Study is supported by U01HL096812, U01HL096814, U01HL096899, U01HL096902, and U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD). The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Sponsors’ Role

The authors are responsible for the content of this article, and the sponsors had no role in design, analysis, or interpretation of results.

Funding and Disclosures

Dr. McDermott is supported by NHLBI T32HL007024; Dr. Selvin is supported by NHLBI K24 HL152440; Dr. Hicks is supported by NIDDK K23DK124515; the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (75N92022D00001, 75N92022D00002, 75N92022D00003, 75N92022D00004, 75N92022D00005). The ARIC Neurocognitive Study is supported by U01HL096812, U01HL096814, U01HL096899, U01HL096902, and U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD). No authors have relevant financial or professional conflicts of interest to report.

Preliminary results of this analysis were presented at the American Heart Association Epi | Lifestyle Conference 2023, Feb 28-Mar 3, 2023, Chicago, IL

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hicks CW, Wang D, Windham BG, Matsushita K, Selvin E. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy defined by monofilament insensitivity in middle-aged and older adults in two US cohorts. Sci Rep. 2021. Sep 27;11(1):19159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hicks CW, Selvin E. Epidemiology of Peripheral Neuropathy and Lower Extremity Disease in Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019. Oct;19(10):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell G, Skubic M. Balance and Gait Impairment: Sensor-Based Assessment for Patients With Peripheral Neuropathy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018. Jun 1;22(3):316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam U, Riley DR, Jugdey RS, Azmi S, Rajbhandari S, D’Août K, et al. Diabetic Neuropathy and Gait: A Review. Diabetes Ther. 2017. Dec;8(6):1253–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JD, Folsom AR, Coresh J, Sharrett AR, Couper D, Wagenknecht LE, et al. The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study: JACC Focus Seminar 3/8. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021. Jun 15;77(23):2939–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful Change and Responsiveness in Common Physical Performance Measures in Older Adults: MEANINGFUL CHANGE AND PERFORMANCE. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006. May;54(5):743–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyrdalen IL, Thingstad P, Sandvik L, Ormstad H. Associations between gait speed and well-known fall risk factors among community-dwelling older adults. Physiother Res Int. 2019. Jan;24(1):e1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osoba MY, Rao AK, Agrawal SK, Lalwani AK. Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review: Balance and Gait in the Elderly. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019. Feb;4(1):143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsitz LA, Manor B, Habtemariam D, Iloputaife I, Zhou J, Travison TG. The pace and prognosis of peripheral sensory loss in advanced age: association with gait speed and falls. BMC Geriatr. 2018. Dec;18(1):274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrer P, Trevisan C, Curreri C, Giantin V, Maggi S, Crepaldi G, et al. Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament Examination for Predicting Physical Performance and the Risk of Falls in Older People: Results of the Pro.V.A. Longitudinal Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018. Jan;99(1):137–143.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.