Abstract

Background:

Public health campaigns have often used persuasive techniques to promote healthy behaviors but the use of persuasion by doctors is controversial. We sought to examine older women’s perspectives.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 20 community-dwelling older women from the Baltimore metropolitan area. We asked whether participants thought it was ethically appropriate for doctors to try to persuade patients and explored their rationales. We probed about commonly used persuasive techniques and two example decisional contexts – stopping mammograms and moving out of one’s house after multiple falls. We used qualitative thematic analysis to code the transcripts and summarized results into major themes.

Results:

We found mixed views on the ethical appropriateness of persuasion (theme 1); supporters of persuasion were motivated by the potential benefit to patients’ health, whereas opponents thought patients should be the ultimate decision-makers. Perspectives depended on the persuasive technique (theme 2), where emotional appeals elicited the most negative reactions while use of facts and patient stories were viewed more positively. Perspectives also varied by the decisional context (theme 3), where higher severity and certainty of harm influenced participants to be more accepting of persuasion. Participants suggested alternative communication approaches to persuasion (theme 4) that emphasized respect for patients.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that the type of persuasive technique and the decisional context are important considerations in the ethical debate around the use of persuasion. Limiting the use of persuasion to high-stakes decisions and using facts and patient stories rather than emotional appeals are likely more acceptable.

INTRODUCTION

Persuasion, defined as trying to change another person’s beliefs or actions, is often used in public health campaigns to change health behaviors.1–7 Use of persuasion has also been documented in doctor-patient communication.8,9 Different types of persuasion have been described, ranging from rational persuasion using reason and evidence to persuasion by appealing to emotions and using stories.1–4,10 However, controversy exists around the ethics of using persuasion.1–4,10–14 Ethical frameworks weigh promoting benefits (beneficence) and minimizing harms (non-maleficence) against the concern that persuasion may threaten patient autonomy.1–4,10–12 On the other hand, others have argued that certain forms of persuasion may be permissible, such as persuasion using rational arguments or persuasion for removing bias, particularly if the goal is to influence decisions to align with patients’ own long-term goals.1–4,13,14

Although there has been much debate in the scientific literature on the ethics of persuasion, there has been little study of the patient perspective. Better understanding patient perspectives can help provide an empirical basis for ethical arguments, generate new areas for theoretical inquiry, and identify challenges for implementing ethical principles in practice.15 Among older patients, medical decision-making has the added challenge that the benefits/harms balance of a specific decision often evolves as an individual ages and their health and functional status change.16 Two common decisions in which older patients may likely disagree with clinician recommendations and raise consideration for using persuasion are stopping routine cancer screening and moving out of one’s home. For example, in older women with multiple chronic conditions and limited life expectancy, breast cancer screening poses more potential harms, such as over-diagnosis and over-treatment of clinically unimportant cancers, than benefits but many of these women continue to get screened beyond guideline recommended age or life expectancy thresholds. 17,18 Robust literature suggests the existence of pro-screening bias, where women consistently over-estimate screening benefits and under-estimate the harms.19–21 In this context of known bias, it is not clear whether persuading older women to stop screening is ethically appropriate.

Another common and challenging decision that older adults and their physicians face is whether to change living environments as the older adults’ health and functional status decline. Approximately 27% of adults 60 years and older live alone and this proportion increases with age.22 Older adults who live alone face higher health and safety concerns.23,24 In particular, falls can be devastating events for older adults living alone with high risk of serious injuries.25,26 Yet, older adults generally prefer to stay in their homes.27 It is not clear if physicians persuading older adults to move to a more supported living environment after repeated falls is ethically appropriate.

We sought in this study to examine older women’s perspectives about the ethical appropriateness of persuasion in doctor-patient communication and specifically about two example decisional contexts - stopping breast cancer screening and moving out of one’s home after frequent falls. We chose a qualitative study design to explore perspectives in depth given that little is known about the topic. Our goal was to explore patient perspectives to better inform clinical discussions.

METHODS

Design, setting, and subject recruitment

Semi-structured interviews lasting 20–60 minutes were conducted with community-dwelling older women (65 years or older) without history of breast cancer. We recruited participants using multiple strategies. We recruited from a research registry of older adults started in 2007 as part of the Johns Hopkins Older Americans Independence Center; it consists of community-dwelling older adults, recruited from the Beacham Ambulatory Care Center (Geriatric Medicine Clinic), the Bayview General Internal Medicine Outpatient clinic, community health fairs, and outreach events focused on older adults throughout the Baltimore metropolitan area. We also recruited through community outreach events, presentations and fliers in senior apartment buildings, and referrals. Eligibility criteria included age 65 or older, female, English-speaking, able to provide informed consent, and not having had breast cancer. Sampling was stratified by participant age (65-<75 years vs. 75+) and by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. other) to ensure diversity. Each participant was offered $75. This project was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Interview guide

The interview guide was developed by the study team, informed by literature on health communication, specifically regarding persuasive techniques.5–7 At the beginning of the interview, we asked respondents about the meaning of persuasion. We then described a scenario where the doctor made a recommendation about medical care and explained the reasons for the recommendation, but the patient disagreed with the recommendation. We explained that we were trying to understand whether the doctor should try to persuade the patient because the doctor believed the recommendation to be in the best interest of the patient. We defined “persuade” as “try to change another person’s beliefs or actions”. We asked in general whether it was ethically appropriate for doctors to try to persuade patients and explored the participants’ reasons for their responses. We then asked about the ethics of persuasion in two specific decisional contexts – i.e., stopping mammograms and moving out of one’s house after multiple falls. Regarding the mammogram decision, we probed about scenarios in which guidelines would recommend against screening, such as advanced age (e.g., 90-years-old) or limited life expectancy (e.g., a woman with dementia or multiple serious illnesses).17 We probed about commonly used persuasive techniques, including emotional appeals (i.e., make the patient feel guilty or scared in order to get them to stop mammograms or to agree to move), presenting unbalanced information on benefits/harms (i.e., emphasize the harms over the benefits of mammograms), and sharing stories about other patients (i.e., a story about someone who did not follow the doctor’s advice and later regretted the decision) (see Appendix for full interview guide).

Data collection and analysis

One investigator (S.H.) conducted the interviews in person or via Zoom from March to August 2023. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We continuously reviewed the transcripts and stopped data collection when no new ideas emerged. We collected information about participants’ age, race/ethnicity, trust in physician,28 past breast cancer screenings, self-reported health, health literacy,29 and education.

We used qualitative thematic analysis to code the transcripts. A codebook was developed based on the interview guide and review of four randomly selected transcripts. Two investigators (N.S. and S.H.) independently coded four transcripts, different than those used for codebook development, and reconciled differences by consensus. The two investigators (N.S. and S.H.) then coded the rest of the transcripts separately. Analyses took the forms of open coding (line-by-line examination of the data to generate concepts), memo writing (to track analysis and minimize introduction of preconceived notions), axial coding (determining applicable dimensions for concepts), and constant comparison to assess saturation and integration of emerging concepts.30 Analysis was aided by qualitative data analysis software, MAXQDA 18. Results were summarized into major themes and illustrated by representative quotes.

RESULTS

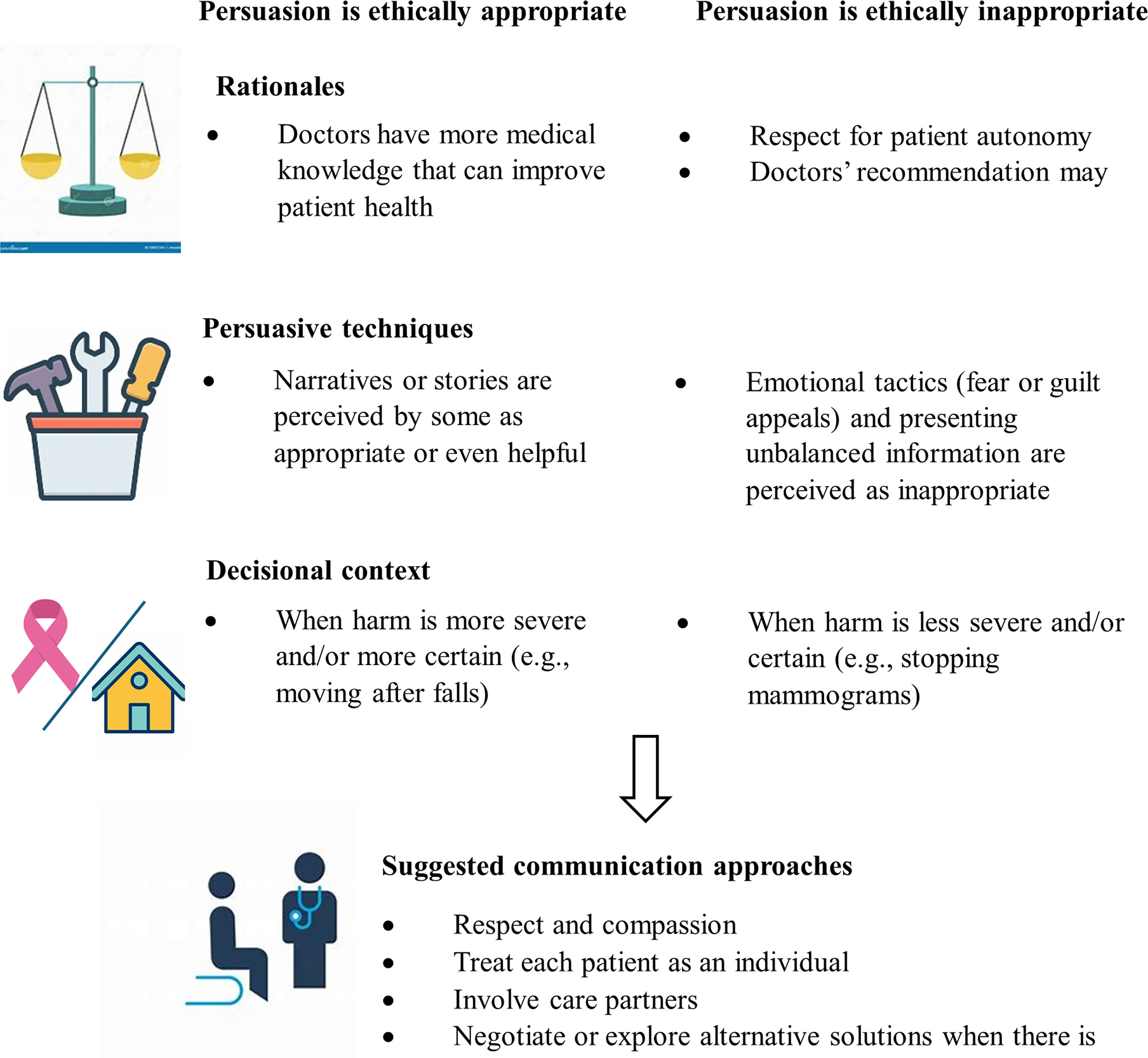

Twenty women participated in the study (Table 1). The mean age was 74.9 years, with 10 (50%) ages 75 or older. 9 (40%) of the participants were White; 9 (40%) Black, and 2 (10%) declined to report race. Content analysis revealed four major themes (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=20).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <75 | 10 (50) |

| 75+ | 10 (50) |

| Race | |

| White | 9 (45) |

| Black | 9 (45) |

| Declined to answer | 2 (10) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High School | 3 (15) |

| ≥Some College | 17 (85) |

| Low health literacy a | 2 (10) |

| Mammogram in past 2 years | 14 (70) |

| Self-reported health | |

| Excellent or Very Good | 9 (45) |

| Good | 8 (40) |

| Fair or Poor | 3 (15) |

| Trust in physician, mean (SD) b | 40.3 (8.4) |

Health literacy was measured using a validated question: “how confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?” Responses of “somewhat”, “a little bit” or “not at all” were categorized as low health literacy. 29

Trust in physician was measured using a validated 10-question scale, scores range from 10–50 with higher score indicates higher trust. 28

Figure 1.

Older women’s perspectives regarding the ethical appropriateness of persuasion, defined as trying to change someone’s beliefs or actions, in doctor-patient communication

Theme 1 – We found a spectrum of views on the ethical appropriateness of persuasion in doctor-patient communication.

We found diverse opinions on the ethical appropriateness of persuasion. Some participants believed that it was acceptable for doctors to persuade patients because doctors have more medical knowledge and their recommendations can improve the patient’s health. One participant said: “I think the doctor would know more about that than the patient. So I’m thinking [persuasion] is appropriate.” Other participants considered persuasion inappropriate because the doctor should only provide information and leave the decision to the patient. One participant commented that persuasion “cancels out the person’s personhood.” Another participant mentioned that doctors should not persuade patients because, despite their good intentions, their recommendations may have unintended consequences: “They think the fall is going to kill [the patient], but a lot of times, the patient being removed from [home] to another environment, they give up the will to live. And so they die, quickly, in the assisted living place or wherever they are supposedly in a safe place to live.”

Theme 2 – Perceived ethical appropriateness of persuasion varied depending on the persuasive technique.

Emotional tactics, such as appealing to fear or guilt, were generally perceived as inappropriate. One participant said: “If a doctor was laying a guilt trip on me, that would be the last time I would see that physician. End of relationship.” Even participants who thought that the concept of persuasion was generally acceptable reacted negatively to persuasion using emotional tactics. One participant said: “Persuade with facts. Persuade with possibilities, not persuade with guilt or fear.”

Presenting unbalanced information on the benefits and harms of a decision was also generally perceived as inappropriate, because such a practice would contradict the doctors’ role to provide information for patients to make informed decisions. One participant said: “I think a doctor should present both sides…the harm and the good. And then let the person make their own decision.”

Views were more mixed regarding telling a story about other patients as a way to persuade someone. Those who were against this approach believed that it was inappropriate because everyone is an individual and another person’s story is not relevant to the patient at hand. However, others found narratives about other patients helpful and mentioned that patients were already getting such narratives from family and friends and would welcome similar narratives from a doctor: “If they have the opportunity to hear from friends or family, those kind of stories of this happened and then the patient got worse, or this happened and then the patient got better. That kind of information can convince or change what someone thinks. When people talk to friends and family that’s what they are hoping to hear, and that’s what’s helpful to hear. You don’t often hear that from a doctor, but if you did, then I think it would be appropriate. I think it would be helpful.”

Theme 3 - Perceived ethical appropriateness of persuasion varied depending on the decisional context.

The participants’ views about the ethical appropriateness of persuasion were often similar across the two decisional contexts – stopping mammograms and moving out of one’s home – but there were some decision-specific variations. Among those who thought persuading patients to stop mammograms was not ethical, some of the reasons for their responses were unique to the decision. Some participants did not believe there was any downside to mammograms so there was no justification for doctors to persuade a patient to stop. One person said: “What do I have to lose [from getting another mammogram]? If I want to, he should just let me do it.” Some participants also perceived mammograms as part of medical care that everyone deserves to have, and therefore considered persuasion to stop mammograms as unethical. One participant said the following when asked about stopping mammograms in older women with dementia: “People with dementia are still people… they deserve to know if they have cancer, and just because they might die in five years doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be treated as anyone else.” Many participants did not consider it appropriate to persuade a patient to stop mammograms even if the patient was 90 years or older, had multiple chronic conditions, or dementia.

Some participants who did not perceive persuasion as ethically appropriate in the mammogram decision changed their views and considered persuasion acceptable regarding the decision to move out of one’s home. The reason for this was that the perceived harm of not following the recommendation was both more severe and more certain: “How many times are you going to fall before you may seriously fall and end up killing yourself?... When it could have been prevented if you had lived with somebody who was there with you… I think that it would be more important to really persuade that person to move before anything serious could happen.” One participant who did not think telling a story about other patients was appropriate to persuade someone to stop mammograms explained why she thought this tactic was appropriate when persuading someone to move: “With the breast cancer screening that was a different story. But with something that’s really gonna hurt you I think that’s appropriate.” Some participants even were willing to accept emotional tactics in this scenario: “I think a scare tactic may be what they need to know… I mean, it is scary if you fall down”; a different participant said: “maybe a scare tactic here wouldn’t hurt to get them to move.”

Theme 4 – Participants suggested alternative communication approaches instead of persuasion.

Participants discussed that persuasion, whether ethical or not, may not be effective in changing the patient’s mind and suggested alternative ways for doctors to communicate with the patient. Participants commented on both general principles of good communication and specific suggestions on how to approach patients disagreeing with the doctor’s recommendation.

Participants emphasized the importance of respect and compassion during discussions and how this can significantly influence the patients’ response to the doctor’s recommendations: “Particularly with older patients, doctors need to listen more than talk. It’s a matter of respect…. It makes a big difference in how they react to the doctor if they don’t get that respect up front.” Participants also agreed on the importance of treating each patient as an individual: “I think they should look at the individual patient… and get a sense of who it is that they’re talking to and how they can best explain information.” Lastly, participants highlighted the importance of recognizing and accommodating different learning styles; one participant who preferred written information said: “People have different learning styles, so if the patient learns better by listening, then talking to them more is going to help. But for me I need something written that I can read again.”

Participants made specific suggestions for dealing with disagreements, such as involving family members or care partners in the discussion, negotiating to find common ground, and exploring alternative solutions. Regarding the mammogram decision, one participant suggested: “Make a deal, you get one more and if it’s negative we don’t do it again, and maybe that will satisfy the patient.” Regarding the moving decision, a participant suggested: “There are multiple alternatives [to persuasion] to help the patient get to that decision on their own. … there are more programs that are popping up to help seniors remain independent.” Another participant said: “If I was inclined to not go along with the doctor’s suggestion, I’d want to know a full range of alternatives, and I’d love to know a full range of outcomes to weigh one against the other.”

DISCUSSION

We explored in depth older women’s perspectives about the ethical appropriateness of persuasion in doctor-patient communication and found a spectrum of views, which varied by persuasive techniques and by the decisional context. Our findings add to the literature since, to our knowledge, there have not been empirical studies of older patients’ perspectives about the ethics of persuasion and the empirical findings can help inform ethical theories. The participants’ rationales for supporting versus opposing the use of persuasion mirrored the ethical principles put forth in the scientific debate, namely the tension between promoting benefits and minimizing harms (beneficence / non-maleficence) and respect for autonomy.1–4,10–14 Those participants who supported the use of persuasion did so because of the potential health benefits from following the doctor’s recommendation and those who opposed the use of persuasion were motivated by the belief that the patient should be the ultimate decision-maker. The idea that persuasion should not be used because of potential unintended consequences from following the doctor’s recommendation is a novel finding and highlights the importance of thoroughly understanding the patient’s concerns and exploring anticipated outcomes from the decision together.

Our exploration of the ethical appropriateness of specific persuasive techniques is also novel. Participants reacted the most negatively to emotion-based persuasion. This is consistent with the increasing recognition of negative consequences from fear or threat-based messaging.31,32 For example, these types of messages have not been as successful in encouraging positive actions such as preparedness for emergencies or disasters, but rather heightened avoidance and denial.31 Participants also reacted negatively to unbalanced information sharing. However, literature demonstrates that communications in clinical encounters are often unbalanced, sometimes without an explicit intention to persuade.8,33 For example, physicians self-reported that they were less awareness of screening harms, especially for breast cancer screening, and less often discussed screening harms, relative to benefits, with patients.33 Our results highlight the importance of providing balanced information in doctor-patient communication so patients can make informed decisions.

Sharing narratives or anecdotes about other patients were viewed more positively; some participants found this type of information not only acceptable but potentially helpful. Narratives or anecdotes have been used in public health and science communication.34–36 Our findings suggest that narratives may be a useful communication tool during clinical encounters for some patients but that clinicians should avoid using emotion-based persuasion or persuasion using unbalanced information.

Our finding that the perceived ethical appropriateness of persuasion varied by the decisional context is new to the literature. We found that the severity and the certainty of anticipated harm from not following the doctor’s recommendation influenced how participants viewed the ethics of persuasion, such that some changed their minds and considered persuasion appropriate when the potential for harm is relatively high. Consistent with prior work, participants perceived minimal harm to breast cancer screening,37 which contributed to their lower acceptance of persuasion in the mammogram decision compared to the moving decision. This empirical finding adds a new dimension to the theory-driven ethical frameworks around persuasion which currently considers promoting benefits (beneficence) and minimizing harms (non-maleficence) but not the extent or certainty of those benefits or harms. Future research may more comprehensively explore different types of decisional contexts and systematically examine the effects of varying specific aspects of the decisional context, such as the certainty or timing of harm.

Our results need to be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. While the focus of qualitative research is not generalizability, we sampled only older women because of the example decision of breast cancer screening and their views may not be applicable to older men and may be specific to the current generation of older women. We also recruited within a single metropolitan area and the results may not reflect the views of older adults from other geographic areas. We included only English-speaking participants, and the results may not be generalizable to non-English speakers or other cultures. We did not include care partners who may often be involved in health decisions with older adults. We elicited reactions to clearly defined and labeled examples of persuasion in our study, but whether patients will necessarily recognize or perceive a similar conversation as persuasive during a discussion is not clear. Our study design probed perspectives regarding hypothetical decisions, and results may not fully reflect their responses in real-world decisions.

In summary, we found mixed views about the ethical appropriateness of persuasion in doctor-patient communication among older women. Perspectives varied by persuasive techniques and by decisional context, where the severity and certainty of harm involved in the decision led participants to consider persuasion more acceptable. Limiting the use of persuasion to high-stakes decisions and using fact or patient stories rather than emotional appeals in clinical discussion are likely more acceptable to patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Funding/support:

This project was made possible by NIA R01AG066741-02S1 grant from the National Institute on Aging. In addition, Dr. Boyd was supported by 1K24AG056578 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: No author had any conflict of interest. Dr. Pollack has stock ownership in Gilead Sciences, Inc. Dr. Boyd receives honorarium from UpToDate for authoring a chapter on multimorbidity. However, we do not believe these have resulted in any conflict with the design, methodology, or results presented in this manuscript.

Prior presentations: Abstract was presented at the Society of Medical Decision Making at Philadelphia, PA in October 2023.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Rubinelli S Rational versus unreasonable persuasion in doctor-patient communication: A normative account. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal-Barby JS. Between reason and coercion: ethically permissible influence in health care and health policy contexts. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2012;22(4):345–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw D, Elger B. Evidence-based persuasion: an ethical imperative. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1689–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell AA, Partin MR. The role of persuasion. JAMA. 2013;310(6):646–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishbein M, Cappella JN. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J Commun. 2006;56(suppl_1), S1–S17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viswanath K, Finnegan JR Jr, Gollust S. Communication and health behavior in a changing media environment. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bassy A Wiley Brand, 2015:327–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuire WJ Input and Output Variables Currently Promising for Constructing Persuasive Communications. In: Rice RE and Atkin CK, Eds., Public Communication Campaigns, 3rd Edition. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2001, 22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez KA, Hurwitz HM, Rothberg MB. Qualitative analysis of patient-physician discussions regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(12):1260–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geurts EM, Pittens CA, Boland G, van Dulmen S, Noordman J. Persuasive communicatoin in medication decision-making during consultations with patients with limited health literacy in hospital-based palliative care. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(5):1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlstrom MF, Ho SS. Ethical considerations of using narrative to communicate science. Science Communication. 2012;34(5):592–617. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo SK, McKasy M. Emotion and humor as misinformation antidotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(15):e2002484118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs N Two ethical concerns about the use of persuasive technology for vulnerable people. Bioethics. 2020;34(5):519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swindell JS, McGuire AL, Halpern SD. Beneficent persuasion: techniques and ethical guidelines to improve patients’ decisions. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubov A Ethical persuasion: the rhetoric of communication in critical care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(3):496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulmasy DP, Sugarman J. “Types of ethical inquiry”. Methods in Medical Ethics. 2001. Georgetown University Press. Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American Geriatrics Society Guiding Principles on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: A review. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1336–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yourman LC, Bergstrom J, Bryant EA, et al. Variation in receipt of cancer screening and immunization by 10-year life expectancy among U.S. adults aged 65 or older in 2019. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39(3):440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torke AM, Schwartz PH, Holtz LR, Montz K, Sachs GA. Older adults and forgoing cancer screening: “I think it would be strange”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):526–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman E, Woloshin S, Schwartz Lm, Byram SJ, Welch HG, Fischhoff B Women’s views on breast cancer risk and screening mammography: a qualitative interview study. Med Decis Making. 2001;21(3):231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ Jr., Welch HG Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Administration on Aging. 2020. Profile of older Americans. Publication date: May 2021 (https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2020ProfileOlderAmericans.Final_.pdf) Accessed May 2024.

- 23.Liu K, Peng W, Ge S, et al. Longitudinal associatoins of concurrent falls and fear of falling with functional limitations differ by living alone or not. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1007563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henning-Smith C, Tuttle M, Tanem J, et al. Social isolation and safety issues among rural older adults living alone: perspectives of meals on wheels programs. J Aging Soc Policy. 2024;36(2):282–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Beil TL Interventions to Prevent Falls in Older Adults Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA Clin. Rev. Educ. 2018;319:1705–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frieson C, Tan M, Ory M, Smith M Evidence-based practices to reduce falls and fall-related injuries among older adults. Front. Public Health. 2018;6:222. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binette Joanne, and Farago Fanni. 2021 Home and Community Preference Survey: A National Survey of Adults Age 18-Plus. Washington, DC: AARP Research, November 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(3):293–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saldana J The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Third edition. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones AM. Use of fear and threat-based messages to motivate preparedness: costs, consequences and other choices: part one. J Bus Contin Emerg Plan. 2012;6(2):180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodsworth L, Ahearne G, Dingwall, et al. The three Rs of fear messaging in a global pandemic: recommendations, ramifications and remediation. Clin Psychol Psychother 2024;31(2):e2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enns JP, Pollack CE, Boyd C, Massare J, Schoenborn NL. Discontinuing cancer screening for older adults: a comparison of clinician decision-making for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screenings. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1122–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):777–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HS, Bigman CA, Leader AE, Lerman C, Cappella JN. Narrative health communication and behavior change: The influence of exemplars in the news on intention to quit smoking. J Commun. 2012;62(3):473–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Annals of Internal Medicine Editors. When evidence collides with anecdote, politics, and emotion: breast cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):531–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutkowi-Hemstreet A, Vu M, Harris R, Brewer NT, Dolor RJ, Sheridan SL. Adult patients’ perspectives on the benefits and harms of overused screening tests: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.