Abstract

In the first trimester of pregnancy the human placenta grows rapidly, making it sensitive to changes in the intrauterine environment. To test whether exposure to an environment in utero often associated with obesity modifies placental proteome and function, we performed untargeted proteomics (LC-MS/MS) in placentas from 19 women (gestational age 35–48 days, i.e. 5+0–6+6 weeks). Maternal clinical traits (body mass index, leptin, glucose, C-peptide and insulin sensitivity) and gestational age were recorded. DNA replication and cell cycle pathways were enriched in the proteome of placentas of women with low maternal insulin sensitivity. Driving these pathways were the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins MCM2, MCM3, MCM4, MCM5, MCM6 and MCM7 (MCM-complex). These proteins are part of the pre-replicative complex and participate in DNA damage repair. Indeed, MCM6 and γH2AX (DNA-damage marker) protein levels correlated in first trimester placental tissue (r = 0.514, P<0.01). MCM6 and γH2AX co-localized to nuclei of villous cytotrophoblast cells, the proliferative cell type of the placenta, suggesting increased DNA damage in this cell type. To mimic key features of the intrauterine obesogenic environment, a first trimester trophoblast cell line, i.e., ACH-3P, was exposed to high insulin (10 nM) or low oxygen tension (2.5% O2). There was a significant correlation between MCM6 and γH2AX protein levels, but these were independent of insulin or oxygen exposure. These findings show that chronic exposure in utero to reduced maternal insulin sensitivity during early pregnancy induces changes in the early first trimester placental proteome. Pathways related to DNA replication, cell cycle and DNA damage repair appear especially sensitive to such an in utero environment.

Keywords: insulin resistance, obesity, placenta

Introduction

The periconceptional and early pregnancy period are critical for fertilization, placentation and embryogenesis [1,2]. These processes require physiological adaptations in the mother and are sensitive to changes in the intrauterine environment [3]. The rapid growth of the human placenta in the first trimester makes it particularly sensitive to perturbations in the intrauterine environment [4,5].

Maternal overweight and obesity, clinically defined as body mass index (BMI) 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively, associate with metabolic changes in the intrauterine environment that are present already in the first trimester [6,7]. It affects embryonic development and is associated with reduced early fetal growth [8]. This may compromise further fetal development and increase the risk for metabolic diseases later in life. Indeed, offspring born from pregnancies complicated by obesity are at higher risk of developing obesity and metabolic diseases in adulthood [9].

In the first trimester of pregnancy, embryonic and fetal growth associate with placental volume and utero-placental vascular volume [10]. Lower volumes in pregnancies complicated by obesity suggest reduced growth not only of the fetus [8] but also of the placenta. In a previous study, we found that maternal obesity alters cell cycle and DNA-damage checkpoint regulators (i.e., breast cancer 1: BRCA1; checkpoint kinase 1: Chk1; checkpoint kinase 2: Chk2; suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic 2/3: SMAD2/3; cell division cycle 25C: CDC25C) in the placenta [11], suggesting increased DNA damage and/or impaired DNA damage repair. However, neither the metabolic traits associated with maternal obesity that impair DNA stability nor the contributing molecular species have been identified.

In the present study, we hypothesized that exposure to an environment often associated with obesity affects placental development very early in pregnancy (week 5+0–6+6 based on the last menstrual period, LMP) by altering the placental proteome. Specifically, we aimed to identify key players in the biological processes severely affected by placental exposure to a metabolically adverse environment

To this end, we first analysed the proteome of 19 first trimester placentas (gestational age 5+0–6+6 weeks) of women with a wide BMI range (19.7–32.4 kg/m2) kg/m2) to cover metabolic variations. Then we identified the clinical traits that associated with the proteome signature. These analyses lead to the further focus on up-regulated key proteins, e.g., minichromosome maintenance (MCM) 6, and we studied their cellular location in first trimester placenta sections. Finally, we conducted in vitro experiments to examine the potential effect of key traits dysregulated in the obese intrauterine environment during the first trimester of pregnancy on the identified proteins. These in vitro experiments were carried out using an established first trimester trophoblast cell line.

Materials and methods

Study participants and placental collection

The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical committee of the Medical University of Graz (no. 29-095 ex 16/17, December 23, 2016 and 31-094 ex 18/19, March 1, 2019). All subjects provided written informed consent. Patient details were limited to those listed in Table 1 to protect patient privacy as a requirement of the ethics approval. Women undergoing a voluntary pregnancy termination (n=35) were recruited. Allocation of samples to experiments is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Inclusion criteria were a singleton pregnancy and no comorbidities, e.g., pre-existing diabetes mellitus, hypertension. Exclusion criterion was maternal age <18 years. Gestational age (days) was calculated based on the last menstrual period (LMP) and confirmed by ultrasound measurement of the crown-rump length. Participants’ height (m) and weight (kg) were measured on the day of pregnancy termination and used to calculate the BMI (kg/m2). Placental tissues were collected during surgical pregnancy termination, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Maternal blood was collected after overnight fast and used to measure concentrations of leptin (ng/ml), glucose (mmol/l) and C-peptide (pmol/l), as previously described [6]. The Homeostatic model assessment of insulin sensitivity index (ISHOMA) was calculated using fasting glucose and C-peptide values [12].

Table 1. Maternal clinical traits of the cohort used for proteomic analysis.

| Discovery cohort (n=19) | |

|---|---|

| Median; IQR | |

| Gestational age (days) | 36 (35–46) |

| Maternal age (years) | 32 (28–39) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8 (19.7–29.0) |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 13.6 (6.1–20.6) |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.4 (4.7–6.0) |

| C-peptide (pmol/l) | 421.2 (306.4–599.2) |

| ISHOMA index | 0.61 (0.37–0.76) |

Maternal clinical traits (median, IQR) of the women whose placental tissue was subjected to untargeted proteomics analysis (n=19).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ISHOMA, homeostatic model assessment of insulin sensitivity; IQR, interquartile range.

Untargeted proteomics in placental tissue

The proteome of 19 first trimester placentas (gestational age week 5+0–6+6 LMP) was analyzed with untargeted proteomics (LC-MS/MS) as previously described [13]. Placenta tissue was thawed and suspended in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, U.S.A.). After 1 h incubation at 37°C, the tissue was lysed by sonication (10 s, 70% amplitude) with a Sonoplus mini20 hand sonicator. Protein content was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay method (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) [14]. The lysate was brought to 100 µl PBS containing 50 µg protein. For reduction and alkylation, 10 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 40 mM 2-chloracetamide (Sigma-Aldrich) were added followed by heating to 95°C for 10 min. Acetone precipitation was performed overnight (–20°C). After centrifugation (14,000 × g; 10 min; 4°C), the protein pellet was dissolved in 25% trifluoroethanol (TFE) in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), which was subsequently diluted to 10% TFE with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Proteins were pre-digested for 2h using 1:100 (w/w) LysC (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) at 37°C and further digested overnight with 1:100 (w/w) sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) at 37°C. The resulting peptide solution was brought to 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Peptide solution containing 4 g protein was used for desalting with Styrene Divinylbenzene-Reversed Phase Sulfonate (SDB-RPS) stage tips (Empore, CDS analytical, Oxford, PA, U.S.A.). After desalting, samples were dried in a vacuum concentrator centrifuge and dissolved in 0.1% formic acid (FA), 2% acetonitrile (ACN) in water.

Samples were analyzed by nano-HPLC (Dionex Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Aurora Series Emitter nanocolumn with CSI fitting (C18, 1.6 µm, 120 Å, 250 × 0.075 mm). Peptides were separated at 35°C at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Solvent A (0.1% FA in water) and solvent B (0.1% FA in ACN) were used in a 133 min chromatography gradient from 2% B up to 95% B. Chromatography was coupled to a Bruker maXis II ETD Q-TOF MS (Bruker, Billerica, MA, U.S.A.) operated with nano-ESI source in positive mode.

For label-free quantitation, MaxQuant software (version 1.6.0.16) with the integrated peptide search engine Andromeda was employed [15]. The match-between-runs feature of MaxQuant was enabled with a retention window of 0.7 min and an alignment window of 20 min. For the database search, the false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1% for both peptides and proteins [15]. Subsequent steps included unsupervised principal component analysis and two-sided unpaired t-test with permutation-based FDR control at a level of 5%.

Mass spectrometry proteomics data was deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [16] partner repository with the data set identifier PXD056380.

Bioinformatics

Downstream data analysis was performed in Perseus (version 1.6.10.43) [17]. Filtering criterion was set to proteins with at least 9 valid values (>0) in at least one group (ISHOMA ≤0.61; ISHOMA >0.61). This was followed by imputation of missing values from normal distribution with regards to the total data matrix. Unsupervised principal component analysis was used to identify clusters in the data. The ISHOMA cut-off was based on the median ISHOMA of the cohort (median ISHOMA = 0.61). Two-sided unpaired T-test (FDR = 0.05) was used to identify proteins that differ between placentas of women with high and low insulin sensitivity. All the proteins in the low ISHOMA group, which were enriched with a P<0.05 (compared with the high ISHOMA group), were selected for building a protein–protein interaction network and functional enrichment analysis in String, version 11.5 [18]. The predefined Homo sapiens library in String uses Ensembl ver. 99 [19] and served as background. The statistically significant enriched terms, for each type of analysis i.e., pathway, biological process, molecular function, cellular component, were selected (based on Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate P-values).

Cell culture

The first trimester trophoblast cell line ACH-3P was cultured in Ham’s F12 medium with glutamine (Biowest, Nuaillé, FR) supplemented with 10% (v/v) defined fetal bovine serum (FBS, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, U.S.A.) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were used within two passages to avoid phenotypic drift and were visually monitored. The cells (2.5 × 104 cells/well in 6-well plates) were transferred to a hypoxic workstation (Xvivo System Model X3, BioSpherix, Redfield, NY, U.S.A.) and allowed to accommodate to the respective oxygen tension for 48 h. All experiments were performed at 6.5% O2, except the oxygen challenge experiment in which cells were cultured at 2.5%, 6.5% or 21% O2. Cell viability (cell morphology and colony formation) was visually examined using a microscope (EVOS Cell Imaging System, Thermo Fisher Scientific) integrated in the hypoxia chamber.

Titration of DNA damage induction

After 72 h in culture, ACH-3P cells were challenged for 1 h with 1, 5 or 10 µM etoposide (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) or DMSO (vehicle) (Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, cells were collected for gene expression and protein analyses.

DNA damage induction and recovery

Cells were maintained in culture for 72 h and thereafter challenged with 10 µM etoposide or DMSO (vehicle) for 1 h. Medium was aspirated and the cells were allowed to recover for 3 or 24 h in fresh medium (Ham’s F12, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin), followed by cell collection for subsequent gene expression and protein analyses.

To investigate γH2AX and MCM6 co-localization in response to different DNA damage inducers, ACH-3P cells were cultured in 4-well chamber slides (1 × 104 cells/well) for 48 h. Thereafter, cells were treated for 1 h with 10 µM etoposide or 10 µM bleomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) (DMSO or F12 medium as respective vehicle controls) and further allowed to recover in fresh medium (Ham’s F12, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin) for 1h. Thereafter, ACH-3P cells were immunostained and γH2AX and MCM6 co-localization assessed.

Insulin treatment

After 48 h in culture (6.5% O2), the medium was replaced by low serum medium (Ham’s F12, 2% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin) for 24 h to reduce insulin in the serum (final insulin concentration: 1.4 × 10−4 nM). Thereafter, cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 10nM insulin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) for further 24 or 48 h and collected for gene expression and protein analyses.

Oxygen challenge

To closely mimic in vivo physiology, cells were cultured for 48 h at 2.5% O2 (physiological oxygen tension until approximately week 8 of pregnancy) [20]. After 48 h, cell were maintained at 2.5% O2 or transferred to 6.5% O2 or 21% O2 for additional 48 h, respectively.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Tissue/Cells Advanced Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, DE) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The methods uses guanidine-based tissue and cell lysis followed by silica-membrane-based purification of total RNA. RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Luna Script RT SuperMix Kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, U.S.A.). TaqMan universal PCR master mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) and TagMan gene expression assays (MCM6: Hs00195504_m1; MCM3: Hs00172459_m1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to assess MCM6 and MCM3 mRNA expression by RT-qPCR in a CFX384 RT-qPCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). Cycle threshold (Ct) values were automatically generated by Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). ΔCt values were calculated using the housekeeping genes TATA-binding protein (TBP: Hs03929085_g1, Thermo Fischer Scientific) and peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIA, Hs04194521_s1, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For graphical representation, the results were normalized to the reference category (insulin experiments: vehicle control; oxygen experiments: 2.5% O2), using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Protein isolation and Western blotting

Placental tissue and ACH-3P cells were resuspended in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing protease (Roche, Mannheim, DE) and phosphoprotease inhibitors (MedChemExpress, Princeton, NJ, U.S.A.). Placental tissue was homogenized in a MagNa Lyser device (Roche). Protein concentration was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein lysates were mixed with Laemmli buffer 2x (Sigma-Aldrich) and denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Equal amounts of total protein (10 µg/well for tissue lysates and 5 µg/well for cell lysates) were loaded on to 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (BioRad Technologies) and resolved at 120 V for 75 min. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad Technologies) and stained with Ponceau S (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk (BioRad Laboratories) in tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) + 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich). After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against MCM6 (1:500 Abcam, cat# ab201683, Cambridge, U.K.); γH2AX (1:1000, Merck, cat# 05-636-1) and α-Tubulin (1:1000, Merck, cat# CP06-100UG) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed three times with TBE and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (anti-rabbit, cat# 1706515; anti-mouse, cat# 1706516; Bio-Rad Laboratories). The SuperSignal West Pico kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for immunodetection in a ChemiDoc Touch imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Band density was quantified in image Lab 6.0.1 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). In tissue, MCM6 and γH2AX band intensities were normalized to α-tubulin. In cell culture experiments (ACH-3P cells), MCM6 and γH2AX band intensities were normalized to Ponceau S to avoid insulin and etoposide effects on α-tubulin [21,22]. To account for inter-membrane variation, data were normalized to an internal standard (placenta tissue or untreated ACH-3P protein lysate cultured at 6.5% oxygen). For graphical representation, results were expressed relative to vehicle control at 24 h (insulin experiment) or 2.5% oxygen (oxygen exposure experiment).

Immunostaining

Paraffin embedded placental tissues were cut into 3.5 µm sections and placed on Superfrost Plus slides (Menzel, Braunschweig, DE). Heat induced antigen-retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.5) in a decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, U.S.A.) for 15 min at 120°C. Peroxidase and protein blocking solutions (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added prior to antibody incubation. For immunohistochemistry, tissue sections from two different placentas were incubated with primary antibodies (MCM6 1:500, Abcam, cat# ab280215; MCM3 1:500, Abcam, cat# ab40125) for 1 h at room temperature followed by 15 min incubation with HRP polymer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and 5 mi AEC single solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were counterstained with Mayer’s haematoxylin (Gratt Koller, Absam, Austria). Images were acquired using a 40× objective in a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using the AxioVision software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

For immunofluorescence, tissue section from 4 different first trimester placentas were incubated with primary antibodies (MCM6 1:500, Abcam, cat# ab201683; γH2AX, 1:100, Merck, cat# 05-636-1) overnight at 4°C and incubated with secondary antibody (1:1000 anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568, cat# 11011; 1:200 anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488, cat# 11001, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1.5 h. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI). To reduce auto-fluorescence, the tissue was incubated for 5 min in 0.3% Sudan Black B (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 70% (v/v) ethanol. For overall MCM6 and γH2AX, images were acquired using a 40× objective in a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus) using AxioVision software (Zeiss). For visualization purposes, the brightness/contrast was adjusted a posteriori using the OlyVia software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For co-localization analysis, images were acquired with A1R confocal microscope (Nikon CEE GmbH, Vienna, Austria) using a 100× objective and same set ups for all images. Three images of different regions were taken for each sample. Co-localization was assessed with ImageJ Fiji software [23]. A scan line was drawn in the area of interest and the intensity (a.u.) per pixel (µm) quantified. The results were plotted in GraphPad Prism (Version 8.4.0, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Z-stacks were used to build 3D images with NIS-Elements software (Nikon). For visualization purposes, the brightness/contrast was adjusted a posteriori in ImageJ Fiji, also stated in figure legends as applies.

To investigate γH2AX and MCM6 co-localization in response to different DNA damage inducers, ACH-3P cells were incubated with primary antibodies (MCM6 1:100, Abcam, cat# ab201683; γH2AX, 1:100, Merck, cat# 05-636-1) for 1 h at room temperature followed by secondary antibody incubation (1:200 anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568, cat# 11001; 1:200 anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633, cat# A-21050; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1.5 h. Images were acquired with A1R confocal microscope and processed as above described.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of the variables and residuals was assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test and Q-Q plot examination. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two groups and one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni multiple comparison test) or Kruskall–Wallis test (Dunn’s multiple comparison test) to compare more than two groups. Correlations were tested using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation as appropriate. A P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS (Version 28.0.1.0) and GrapPhad Prism (Version 8.4.0).

Results

Study participants

We performed untargeted proteomics analysis on 19 first trimester placentas. Clinical traits including BMI, C-peptide and ISHOMA of the women undergoing elective terminations are described in Table 1.

The placental proteome differs between women with low and high insulin sensitivity

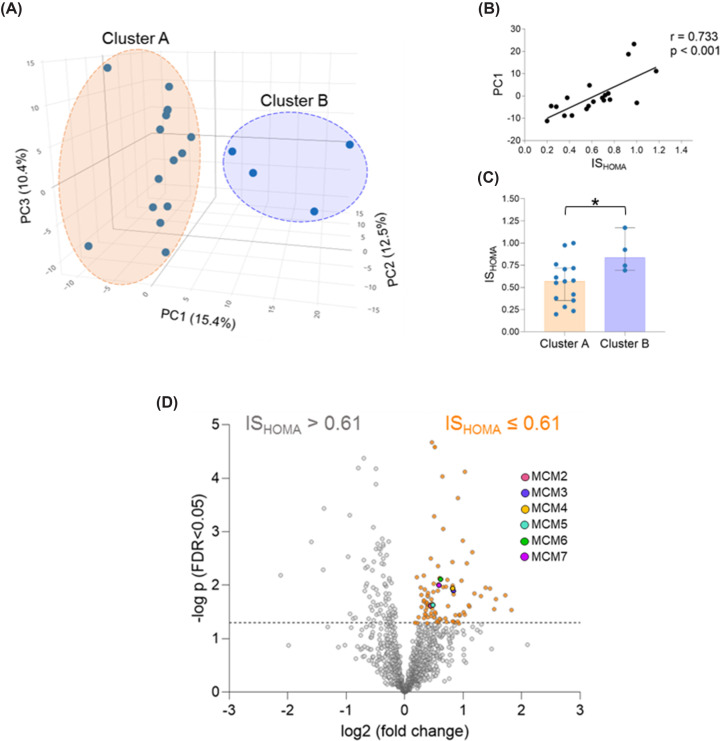

The proteome of 19 first trimester placentas was analysed by untargeted proteomics. Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated two clusters of placental samples (Cluster A: n=15; Cluster B: n=4) (Figure 1A). To identify the driver of cluster separation in PC1, clinical traits of the women (BMI, leptin, glucose, C-peptide and ISHOMA index) and gestational age were correlated with PC1 coordinates. Insulin sensitivity, i.e., ISHOMA, was the clinical trait that best correlated (highest correlation coefficient) with PC1 (r = 0.733, P<0.001) (Figure 1B). When the clinical traits were compared between clusters using a group-comparison test, only ISHOMA was significantly different (P=0.049) between clusters. ISHOMA was higher in women whose placentas grouped in cluster B (Figure 1C). BMI did not significantly differ between clusters despite a correlation between BMI and ISHOMA (r = −0.556, P=0.013).

Figure 1. Maternal insulin sensitivity associates with changes in the placental proteome.

The proteome of first trimester placental tissue (n=19) was analyzed by untargeted proteomics (MS/MS). (A) Principal Component Analysis demonstrated two clusters. (B) ISHOMA was the clinical trait that better correlated with PC1 (C) Maternal ISHOMA was the only parameter significantly (P<0.05) different between clusters (Mann–Whitney U test). Individual data as well as median and 95% confidence intervals are presented. (D) The samples were classified into high (ISHOMA≥0.61) or low (ISHOMA<0.61) insulin sensitivity based on the median ISHOMA value (median ISHOMA = 0.61) and their proteome compared. Proteins above the dotted line are significantly (P<0.05) enriched. Proteins significantly enriched in the low ISHOMA group are colored in orange. BMI, body mass index; ISHOMA, homeostatic model assessment of insulin; ns, non-significant; *P<0.05.

Thereafter, we used the median ISHOMA of the cohort (median ISHOMA = 0.61) as cut-off to classify placental samples of women into those with ISHOMA>0.61 or ISHOMA≤0.61 and denoted them as ‘high’ and ‘low’ insulin sensitivity, respectively. Clinical traits of women in these two groups are shown in Table 2. Differential expression analysis compared the proteomes between the two groups. It identified 86 proteins enriched in the group of placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity as represented in a volcano plot (Figure 1D).

Table 2. Clinical traits of the women whose placental tissue was used for proteomics stratified by ISHOMA.

| Discovery cohort (n=19) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ISHOMA > 0.61 (n=9) | ISHOMA ≤ 0.61 (n=10) | ||

| Median; IQR | Median; IQR | P-value | |

| Gestational age (days) | 35 (35–43) | 45 (35–48) | 0.113 |

| Maternal age (years) | 35 (25–39) | 32 (29–35) | 0.780 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.2 (19.7–23.2) | 28.7 (23.3–32.4) | 0.079 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 9.3 (2.7–14.2) | 19.2 (14.0–28.5) | 0.055 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.2 (4.1–5.8) | 5.5 (4.8–6.4) | 0.278 |

| C-peptide (pmol/l) | 308.5 (277.6–413.0) | 599.2 (510.7–760.8) | <0.001 |

| ISHOMA index | 0.75 (0.7–0.98) | 0.34 (0.26–0.57) | <0.001 |

Maternal clinical traits (median, IQR) of the women whose placental tissue was subjected to untargeted proteomics analysis (n=19) stratified by ISHOMA.

BMI, body mass index; ISHOMA, homeostatic model assessment of insulin sensitivity; IQR, interquartile range; P: P-value.

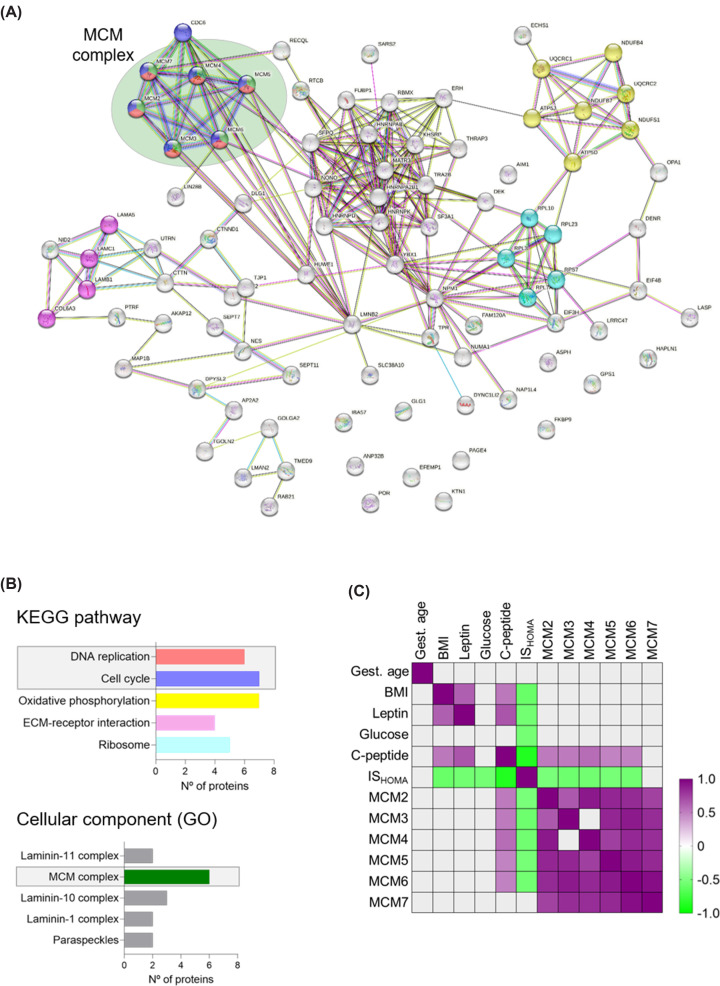

DNA replication and cell cycle pathways are up-regulated in the placental proteome of women with low insulin sensitivity

Using STRING network analysis [18], we explored associations between the 86 proteins enriched in the group of placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity. The individual proteins up-regulated in the low ISHOMA group and their interrelationship are visualized in Figure 2A. Using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) we found ‘DNA replication’, ‘cell cycle’ and ‘ribosome processes pathways’ significantly enriched in placentas of women with low ISHOMA (Figure 2B). Terms related to DNA replication, DNA damage and DNA repair were recurrent in other databases such as gene ontology and reactome pathways (Supplementary Table S1). Proteins driving DNA-related pathways were MCM2, MCM3, MCM4, MCM5, MCM6 and MCM7. The MCM proteins constitute the MCM-complex (Supplementary Figure S2) and are components of the pre-replicative complex at the origins of replication during the G1 phase of the cell cycle [24]. MCM proteins are also known to participate in DNA damage repair [25–27].

Figure 2. DNA replication and cell cycle pathways are up-regulated in the placental proteome of women with low insulin sensitivity and the MCM-complex drives this enrichment.

(A) Proteins enriched (n=86, P<0.05) in the low ISHOMA group (ISHOMA<0.61) were selected for further network analysis (String V.11.5). (B) DNA replication, cell cycle and ribosome pathways were significantly enriched KEGG pathways in the low ISHOMA group. Six proteins from the MCM-complex (MCM2-7) were the drivers for enrichment of DNA replication and cell cycle pathways (Gene Ontology). (C) Clinical traits known to be dysregulated in maternal obesity in the first trimester of pregnancy were correlated with raw LFQ values (Label Free Quantification; semi-quantitative measure of concentration) of MCM2-7 proteins. All proteins of the MCM-complex, except MCM7, were positively correlated with C-peptide and inversely correlated with ISHOMA. Most individual MCM proteins were positively correlated with each other. ECM, Extracellular matrix; GO, Gene Ontology; ISHOMA, homeostatic model assessment of insulin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Next, we sought to test for correlations between maternal clinical traits and MCM2-7 protein levels. ISHOMA was inversely correlated with MCM2-6 suggesting that placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity have increased MCM2-6 protein levels. C-peptide, a component of ISHOMA calculation, was positively correlated (Figure 2C and Supplementary Table S2). MCM7 was not significantly correlated with any clinical trait. Moreover, protein levels of each MCM correlated with those of all other MCMs tested except of MCM3, which did not correlate with MCM4 (Supplementary Table S3). This suggests that MCM2-7 act synergistically as part of the MCM2-7 heterohexamer (MCM-complex) [24,28]. Because of this, we selected MCM6, the MCM most enriched in the low ISHOMA group (proteomic analysis), as a representative of the MCM-complex for further investigation (Supplementary Figure S2).

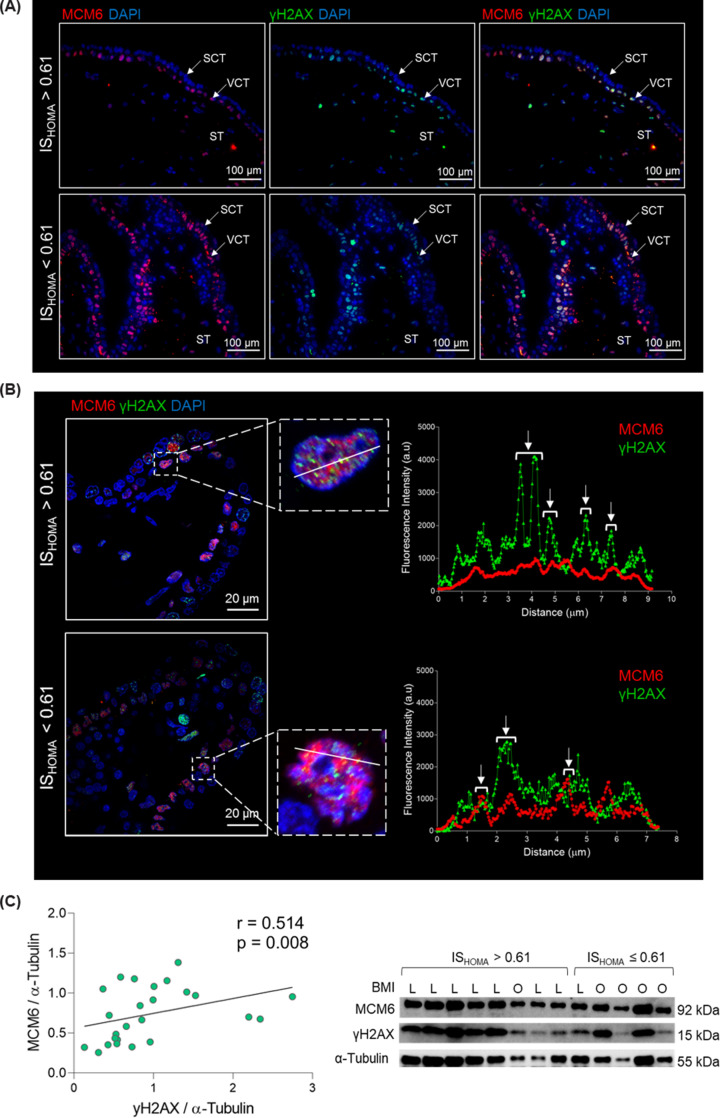

γH2AX and MCM6 co-localize in human first trimester cytotrophoblast cells

Because the MCM-complex has a role in the repair of DNA double strand breaks, we hypothesized that increased MCM levels in placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity reflect increased DNA damage in these placentas. To fulfil its function, MCM6 has to be present in close proximity to DNA damage sites (γH2AX foci) [29,30]. Therefore, we ascertained the cellular and subcellular localization of MCM6 and γH2AX in tissue sections from four different first trimester placentas (Figure 3A; Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Figure S2). The MCM6 protein was mainly localized to the nuclei of villous cytotrophoblast cells, the proliferative cell type of the placenta. Some nuclei of stromal cells were also immunopositive for MCM6. Surprisingly, some MCM6 foci were also detected in cytoplasmic regions (Supplementary Figure S3). Similarly, γH2AX foci were also predominantly found in the nuclei of villous cytotrophoblast cells with some nuclei in the syncytiotrophoblast and stroma also immunopositive for γH2AX.

Figure 3. γH2AX and MCM6 co-localize to the nuclei of villous cytotrophoblast cells in the first trimester placenta.

Placenta tissue of high (n=2) and low (n=2) insulin sensitive pregnant women was stained with anti-MCM6, anti-γH2AX antibodies and DAPI (nucleus). Representative images are shown. (A) Tissue overview of MCM6 and γH2AX staining acquired in a light microscope (40×). MCM6 and γH2AX localize predominantly to the nuclei of cytotrophoblast cells. Some MCM6 foci are visible in the cytoplasm (see supplementary Figure S3). (B) For co-localization assessment, z-stacks were acquired in a confocal microscope (100×). The line scan tool (ImageJ, FIJI) was used to measure fluorescence intensity (a.u.) per pixel (µm) and the data plotted using GraphPad prism. (C) First trimester placental lysates (n=23) were resolved in SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-MCM6, anti-γH2AX and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. Band intensity was quantified and normalized to α-tubulin. MCM6 and γH2AX protein levels were correlated (Spearman’s correlation). Brightness and contrast adjusted for visualization purpose. ISHOMA, homeostatic model assessment of insulin; L, lean; O, overweight-obese.

We performed co-localization analyses to investigate whether MCM6 and γH2AX are in close proximity (Figure 3B). We found that MCM6 and γH2AX fluorescence intensities overlap in villous cytotrophoblast nuclei, indicating co-localization of MCM6 and γH2AX in this specific cell type. This co-localization was found in placentas of women with low and high ISHOMA (Figure 3B).

Furthermore, γH2AX significantly correlated with MCM6 protein levels in total placental tissue (n=23; r = 0.514; P<0.01), suggesting that increased DNA damage associates with increased MCM6 protein levels (Figure 3C and Supplementary Table S4).

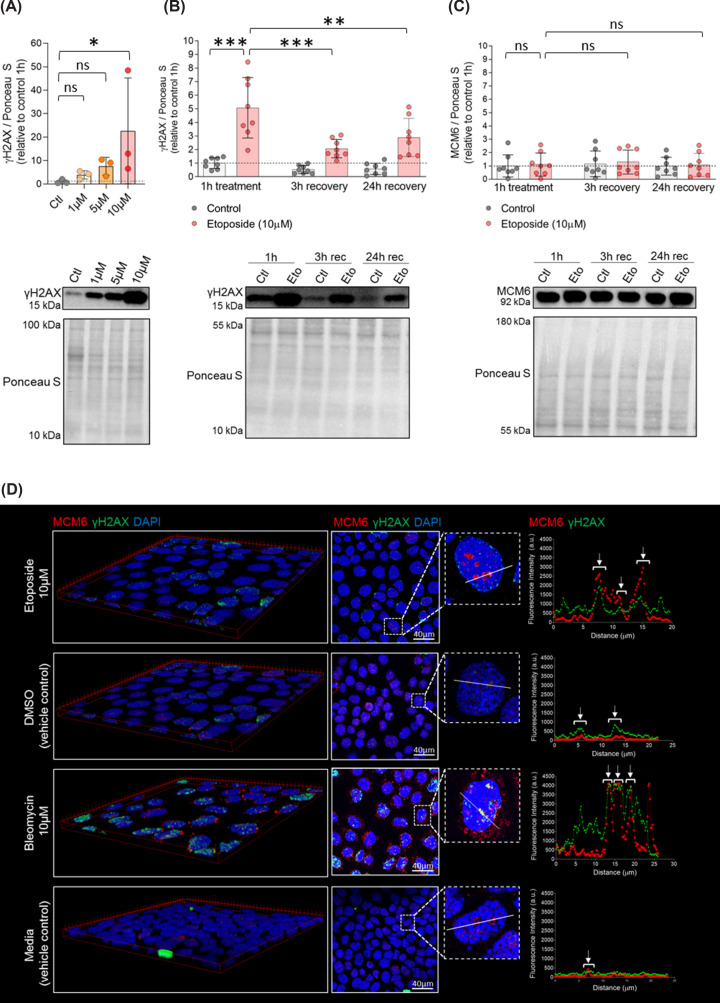

DNA damage induction in ACH-3P cells

To study the dynamics of DNA damage and DNA damage repair in the first trimester placenta, the first trimester trophoblast cell line ACH-3P was used [31]. In a positive control experiment, exposure to etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor, for 1 h was sufficient to induce DNA damage (γH2AX increase) (Figure 4A). DNA damage was partially repaired after 3 h of culture in absence of this drug (Figure 4B). However, this was not accompanied by changes in MCM6 levels (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Etoposide induces DNA damage in ACH-3P cells and the damage is repaired within 3 h.

(A) ACH-3P cells (n=1 experiment; in triplicates) were cultured at 6.5% O2 in absence (control) or presence of etoposide (1, 5 and 10 µM) for 1 h. Cells were harvested immediately and cell lysates subjected to Western blotting. DNA damage (measured as γH2AX) was quantified and protein levels normalized to Ponceau S. Data are presented as mean ± SD. (B,C) After 1 h of treatment (control or 10 µM etoposide), cells (n = 3 experiments; in triplicates) were allowed to recover in fresh media for 3 or 24 h. Thereafter, cells were harvested and cell lysates subjected to Western blotting using anti-γH2AX and anti-MCM6 antibodies. Results are shown relative to control at 1 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with post hoc test and Bonferroni correction was used to compare protein levels between control after 1 h of exposure (reference) and etoposide after 1 h of exposure and 3 and 24 h of recovery. (D) MCM6 is recruited to sites of DNA damage. ACH-3P cells (n = 1 experiment, in triplicates) were cultured at 6.5% O2 in presence of etoposide (10 µM), bleomycin (10 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO and F12 media, respectively) for 1 h. Thereafter, cells were allowed to recover in fresh media (F12 media) for 1 h. Subsequently, cells were incubated overnight with anti-MCM6 and anti-γH2AX. DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. Images were acquired with a confocal microscope. 3D images and co-localization analysis in ImageJ - Fiji. Arrows indicate regions, i.e., pixels, where γH2AX and MCM6 signals co-localize. Brightness and contrast of immunofluorescence and Ponceau S staining adjusted for better visualization. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ns: non-significant. Ctl: vehicle control (DMSO); Eto: etoposide; Rec: recovery.

To address whether MCM6 can be actively recruited to sites of DNA damage, ACH-3P cells were challenged with etoposide (causes DNA damage at origin of replication sites) or bleomycin (causes damage at random sites of the chromosomes). Both treatments induced formation of γH2AX foci and γH2AX and MCM6 co-localized in both experimental conditions. Visual inspection of co-localization analysis after bleomycin treatment indicates that MCM6 can be recruited to sites of DNA damage (Figure 4D).

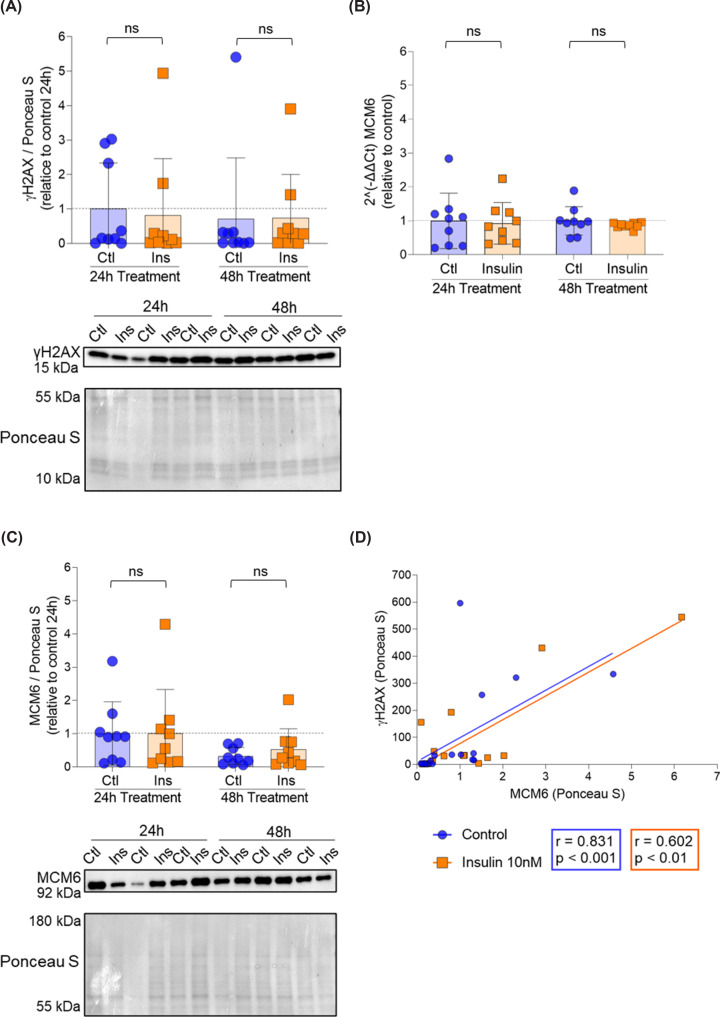

Insulin and oxygen do not induce DNA damage in ACH-3P cells

Insulin sensitivity (ISHOMA index) is calculated using glucose and C-peptide values. Because insulin sensitivity itself cannot induce changes in the placental proteome, we speculated that the changes in MCMs protein levels must be mediated by glucose or C-peptide. Since only C-peptide (surrogate of insulin) was significantly correlated with MCMs protein levels (Figure 2), we chose insulin to challenge ACH-3P cells and obtain mechanistic insight. Insulin exposure for 24 and 48 h did not cause DNA damage (Figure 5A) and it did not affect MCM6 mRNA expression (Figure 5B) nor protein levels (Figure 5C). There was a significant correlation between γH2AX and MCM6 protein levels, but it was independent of insulin treatment (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. The correlation between γH2AX and MCM6 is independent of insulin.

ACH-3P cells (n = 3 experiments; in triplicates) were cultured at 6.5% O2 for 48 h to accommodate them to the oxygen tension. After 72 h, cells were treated with vehicle control (F12 media) or 10 nM insulin. Cells were harvested after additional 24 and 48 h and cell lysates subjected to RT-qPCR and western blotting. (A) DNA damage (measured as γH2AX) was quantified by Western blotting and protein concentration normalized to Ponceau S. (B) MCM6 expression was quantified by RT-qPCR and normalized to housekeeping genes peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIA) and TATA-binding protein (TBP). (C) MCM6 was quantified by western blotting and protein concentration normalized to Ponceau S. (D) γH2AX and MCM6 protein levels were correlated using Spearman correlation. Results (A–C) are shown relative to control 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare expression and protein levels between controls and insulin treated samples. Brightness and contrast of Ponceau S staining adjusted for better visualization. ns: non-significant.

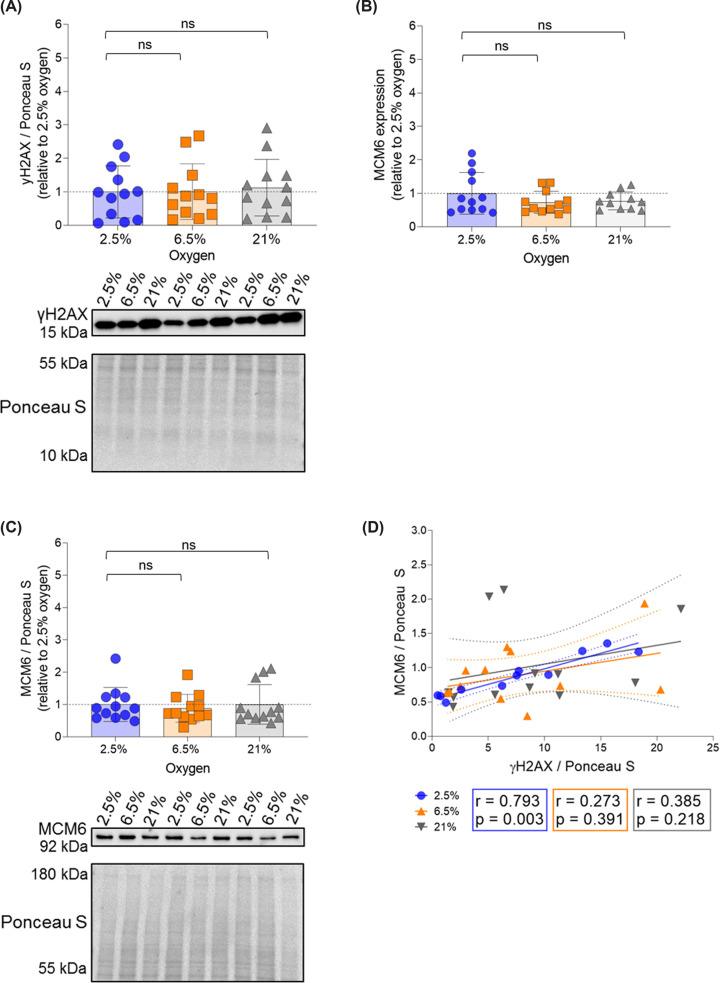

Evidence suggests a delay in spiral artery remodelling of placentas exposed to maternal obesity [32]. Consequently, these placentas are exposed to lower oxygen tension for a prolonged time. We speculated that the prolonged exposure to low oxygen combined with hypoxia-reoxygenation [33] induces increased MCMs expression and protein levels. Culturing ACH-3P cells at 2.5% O2, i.e. physiological oxygen tension before spiral artery remodeling, during 96 h did not result in differences in γH2AX protein levels (Figure 6A), MCM6 mRNA expression (Figure 6B) or protein levels (Figure 6C) compared with cells transferred to 6.5% (physiological oxygen tension after the spiral artery remodelling) or 21% (hyperoxygenation) for 48 h. Again, γH2AX and MCM6 protein levels were significantly correlated, but only at 2.5% oxygen (Figure 6D). However, large variation of the data may have precluded correlation at 6.5% and 21% oxygen.

Figure 6. The correlation between γH2AX and MCM6 is independent of oxygen tension.

ACH-3P cells (n = 4 experiments; in triplicates) were cultured at 2.5% O2 for 48 h. Afterward, one plate per experiment was kept at 2.5%, while the other plates were transferred to 6.5% or 21% for 48 additional hours. Thereafter, cells were harvested and cell lysates subjected to PCR or Western blotting. (A) DNA damage (measured as γH2AX) was quantified and protein level normalized to Ponceau S. (B) MCM6 expression was quantified by RT-qPCR and normalized to the house keeping genes PPIA and TBP. (C) MCM6 was quantified and protein level normalized to Ponceau S. (D) γH2AX and MCM6 protein levels were correlated using Spearman correlation. Results are shown relative to 2.5% O2. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare protein levels between samples at 2.5% O2 (reference category) and samples exposed to 6.5% and 21% O2. Brightness and contrast of Ponceau S staining adjusted for better visualization. ns: non-significant.

Discussion

This is the first untargeted study analysing the proteome of human first trimester placentas exposed to an obesogenic environment in utero. We found that exposure to low maternal insulin sensitivity associates with changes in the placental proteome. These changes include up-regulation of cell cycle and DNA damage repair pathways. We identified the MCM-complex as a key player in these pathways. While the MCM-complex has been studied intensively in cancer, where it is overexpressed and used as diagnostic marker of disease progression [34], its potential role in metabolic pathophysiology has not been described yet.

The MCM-complex is formed by six homologous proteins that are recruited to the origins of replication to initiate DNA replication in the S-phase of the cell cycle [35]. However, MCM proteins are estimated to be 40- to 100-fold more abundant than the number of origins of replication in the cell and only a fraction of MCMs is associated with chromatin during the S-phase [27,36]. This phenomenon is known as the MCM-paradox and suggests alternative roles for MCM proteins. These alternative roles include maintaining chromosome stability and participating in DNA damage repair by interacting with checkpoint regulators (e.g., radiation (Rad)17) [37] and proteins involved in DNA damage repair (ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related protein; TP53, tumor protein 53; 53BP1, tumor protein 53 binding protein) [38–40]. Of note, protein levels of Rad52, which together with Rad 51 is critical for homologous recombination, are highly elevated in placentas of women with obesity [11]. Our finding of a correlation between γH2AX (marker of DNA damage) and MCM6 protein level in the first trimester placental tissue together with the co-localization of both proteins in villous cytotrophoblast nuclei suggests that MCMs participate in repairing DNA damage in this cell type. However, this notion requires formal testing.

The gene coding for MCM6 is located at chromosome 2, in proximity to the lactase gene (LCT). Because LCT has been shown to be overexpressed in people with obesity [41,42], the MCM6 increase found here may be genetically driven. However, each MCM gene is located on a different chromosome, excluding the hypothesis of MCM6 overexpression only due to genetic background. Moreover, the correlation between protein levels of individual MCMs in the first trimester placenta argues for a synergistic action of MCMs as part of the MCM-complex, rather than they executing individualized functions. A further argument for a synergistic activity of MCM2-7 is that MCM proteins, which are not part of the MCM-complex but rather act individually (MCM1, MCM8 and MCM9) [24], were not enriched in placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity.

To investigate whether MCMs role in repairing DNA damage is limited to breaks occurring at origins of replication or whether MCMs can be actively recruited to sites of DNA damage, we challenged ACH-3P cells with etoposide (topoisomerase II inhibitor) and bleomycin (cleaves DNA in the presence of iron and oxygen). Co-localization of γH2AX and MCM6 in cells treated with bleomycin shows that MCMs can be recruited to sites of DNA damage which are not located at origins of replication. This indicates that MCMs participate in DNA damage repair also at other locations in the chromatin. Interestingly, MCM6 foci also localized to the cytosol and this was especially evident in cells treated with bleomycin. Re-examining stained tissue sections for MCM6, we corroborated that cytoplasmic localization also occurs in placental tissue. The role of cytoplasmic MCM6 foci is unclear, but increasing evidence suggests a role in the stability of stress granules [42]. Further studies in this direction are required and may establish a new role for MCM proteins as coordinators of stress response pathways and DNA replication.

The ISHOMA index is calculated from fasting glucose and C-peptide values. Because C-peptide, the by-product of insulin synthesis, but not glucose, was significantly correlated with MCMs protein levels, we speculated that increased MCMs levels in placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity might be the result of hyperinsulinemia rather than hyperglycemia. To establish a causal link between hyperinsulinemia and MCMs up-regulation, we challenged the ACH-3P cell line with insulin. However, we did not detect an increase in DNA damage nor MCM6 concentration under these experimental conditions, although ACH-3P are insulin responsive [43,44].

MCM expression is up-regulated in proliferating cells [45,46]. Cytotrophoblast cells have been shown to proliferate under low oxygen tension (2%) and to differentiate when oxygen tension rises (20%) [47]. We speculated that the increased MCM levels in placentas of women with low insulin sensitivity might reflect low oxygenation in these placentas. This could be caused by delayed opening of the spiral arteries, which has been suggested in pregnancies complicated by obesity [32]. However, in ACH-3P cells, a suitable cell model for first trimester proliferating cytotrophoblast cells [31] that respond to insulin and oxygen tension changes [43,44], exposure to low oxygen tension (2.5%) did not increase DNA damage nor MCM6 concentration, despite a correlation between γH2AX and MCM6 only at this specific oxygen tension. The MCM paradox as well as the short exposure time in vitro mimicking acute effects of the environment may account for the lack of change in MCM6 concentration in ACH-3P cells under the tested experimental conditions. Indeed, MCM6 expression in a mouse model of obesity-insulin resistance (BTBR ob/ob) is increased in the pancreatic islets and adipose tissue at 10 weeks, but not at 4 weeks of age [48]. Similarly, in humans with overweight-obesity, hepatic MCM2 and muscular MCM4 are overexpressed in the low insulin sensitive compared with the normal insulin sensitive group [49].

This is the first study on how the maternal environment often associated with obesity alters the placental proteome and function already in the first trimester. An important strength is that we considered maternal clinical traits like leptin, glucose, C-peptide and insulin sensitivity and not only BMI. This is important because individuals with high BMI can still be metabolically healthy [50], making BMI a poor metabolic health indicator [51].

We included samples of a narrow gestational age range (5+0–6+6 weeks) to prevent confounding effects of a wider gestational age range. This is important to avoid differences caused by the transition from histiotrophic to haematotrophic nutrition and rise in oxygen tension in the intervillous space between weeks 6 and 12 of pregnancy [52,53]. Such transitions would hide the association between placenta proteins and a specific maternal phenotype [54]. Rather, we captured effects predominantly caused by exposure to the maternal obesogenic environment in utero. Similar to our study, a gene expression microarray found cell cycle and DNA metabolism pathways up-regulated in first trimester (6+3–8+3 days) compared with second trimester (15+4–16+3 weeks) placentas [55], indicating that up-regulation of these pathways is common in the first trimester period. Unfortunately, that study did not provide information on maternal characteristics, which precludes interpreting whether their findings are due to an overrepresentation of women with obesity in their cohort.

A limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size, which precluded analysing potential fetal sex effects on the placenta proteome. However, MCMs expression was not significantly different in transcriptomic analysis of male and female placentas [56,57]. The small amount of tissue in this very early period also made it impossible to run all experiments on all tissue samples. It shall also be noted that immunohistochemistry was used solely for qualitative measurements.

Our in vitro studies failed to induce in vitro MCM changes in ACH-3P cells by treating them with insulin. This may be accounted for by ACH3-P cell properties and needs to be formally confirmed in another first trimester cell line model such as AL07 cells [58]. As noted above, it is important to keep in mind that these experiments mimic acute changes whereas the placentas studied here have been exposed to the obesity-associated intrauterine environment for several weeks. Hence, the in vivo first trimester placental findings are the result of chronic exposure. Consequently, acute in vitro studies using cell cultures may not be suitable to capture the homeostatic and allostatic mechanisms that are in place in vivo to drive placental development. Systems-wide approaches capturing these mechanisms are needed and should be the next step.

In conclusion, chronic exposure in utero to reduced maternal insulin sensitivity during 5+0– 6+6 weeks in the first trimester of human pregnancy induces changes in the placental proteome, especially of pathways related to DNA replication, cell cycle and DNA damage repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the women participating in the study. The authors would also like to thank Dr Nick Rhind, Dr Pia Nyeng, Ing. Daniel Bergmann, Francisco Jose Fernandez-Hernandez MSc and Dr Bruno di Geronimo.

Abbreviations

- 53BP1

tumor protein 53 binding protein

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related protein

- BRCA1

breast cancer 1

- CDC25C

cell division cycle 25C

- Chk1

checkpoint kinase 1

- Chk2

checkpoint kinase 2

- DAPI

4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindol

- PCA

principal component analysis

- SMAD2/3

suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic 2/3

- TP53

tumor protein 53

Data Availability

Mass spectrometry proteomics data was deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [16] partner repository with the data set identifier PXD056380.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) 10.55776/DOC31 (doc.funds DP-iDP). For open access purposes, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. J.B.-M. received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) 0.55776/DOC31 (doc.funds DP-iDP) and the Medical University Graz through the PhD Program Inflammatory Disorders in Pregnancy (DP-iDP). A.M.-M. and G.D. were supported by a fund of the Österreichische Nationalbank, Vienna (Anniversary Fund, project number: 17950). S.E.H. and R.B.-G. received funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF [grant number F73 (SFB ‘Lipid hydrolysis’) and W1226 (Doctoral School ‘DK-Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease’)] as well as the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research for funding (Marietta Blau scholarship awarded to S.E.H. by the OeAD-GmbH).

CRediT Author Contribution

Julia Bandres-Meriz: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Marta Inmaculada Sanz-Cuadrado: Investigation, Visualization. Irene Hurtado de Mendoza: Investigation, Visualization. Alejandro Majali-Martinez: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Sophie Elisabeth Honeder: Investigation, Methodology. Tereza Cindrova-Davies: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Ruth Birner-Gruenberger: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Louise Torp Dalgaard: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Gernot Desoye: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing—review & editing.

References

- 1.Moreno I., Capalbo A., Mas A., Garrido-Gomez T., Roson B., Poli M.et al. (2023) The human periconceptional maternal-embryonic space in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 103, 1965–2038 10.1152/physrev.00050.2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cindrova-Davies T. and Sferruzzi-Perri A.N. (2022) Human placental development and function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 131, 66–77 10.1016/j.semcdb.2022.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton G.J., Jauniaux E. and Charnock-Jones D.S. (2010) The influence of the intrauterine environment on human placental development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 54, 303–312 10.1387/ijdb.082764gb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desoye G. (2018) The human placenta in diabetes and obesity: friend or foe? The 2017 Norbert Freinkel Award Lecture Diabetes Care 41, 1362–1369 10.2337/dci17-0045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoch D., Gauster M., Hauguel-de Mouzon S. and Desoye G. (2019) Diabesity-associated oxidative and inflammatory stress signalling in the early human placenta. Mol. Aspects Med. 66, 21–30 10.1016/j.mam.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandres-Meriz J., Dieberger A.M., Hoch D., Pochlauer C., Bachbauer M., Glasner A.et al. (2020) Maternal obesity affects the glucose-insulin axis during the first trimester of human pregnancy. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 566673 10.3389/fendo.2020.566673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandres-Meriz J., Majali-Martinez A., Hoch D., Morante M., Glasner A., van Poppel M.N.M.et al. (2021) Maternal C-peptide and insulin sensitivity, but Not BMI, associate with fatty acids in the first trimester of pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1–13 10.3390/ijms221910422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Duijn L., Rousian M., Laven J.S.E. and Steegers-Theunissen R.P.M. (2021) Periconceptional maternal body mass index and the impact on post-implantation (sex-specific) embryonic growth and morphological development. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 45, 2369–2376 10.1038/s41366-021-00901-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Entringer S., Buss C., Swanson J.M., Cooper D.M., Wing D.A., Waffarn F.et al. (2012) Fetal programming of body composition, obesity, and metabolic function: the role of intrauterine stress and stress biology. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 632548 10.1155/2012/632548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reijnders I.F., Mulders A., Koster M.P.H., Kropman A.T.M., de Vos E.S., Koning A.H.J.et al. (2021) First-trimester utero-placental (vascular) development and embryonic and fetal growth: The Rotterdam periconception cohort. Placenta 108, 81–90 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch D., Bachbauer M., Pochlauer C., Algaba-Chueca F., Tandl V., Novakovic B.et al. (2020) Maternal obesity alters placental cell cycle regulators in the first trimester of human pregnancy: new insights for BRCA1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1–18 10.3390/ijms21020468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radaelli T., Farrell K.A., Huston-Presley L., Amini S.B., Kirwan J.P., McIntyre H.D.et al. (2010) Estimates of insulin sensitivity using glucose and C-Peptide from the hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 33, 490–494 10.2337/dc09-1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomin T., Fritz K., Gindlhuber J., Waldherr L., Pucher B., Thallinger G.G.et al. (2018) Deletion of Adipose Triglyceride Lipase Links Triacylglycerol Accumulation to a More-Aggressive Phenotype in A549 Lung Carcinoma Cells. J. Proteome Res. 17, 1415–1425 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith P.K., Krohn R.I., Hermanson G.T., Mallia A.K., Gartner F.H., Provenzano M.D.et al. (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox J. and Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 10.1038/nbt.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Riverol Y., Bai J., Bandla C., Garcia-Seisdedos D., Hewapathirana S., Kamatchinathan S.et al. (2022) The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D543–D552 10.1093/nar/gkab1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyanova S., Temu T., Sinitcyn P., Carlson A., Hein M.Y., Geiger T.et al. (2016) The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 10.1038/nmeth.3901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Nastou K.C., Lyon D., Kirsch R., Pyysalo S.et al. (2021) The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D605–D612 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. www.ensembl.org dates of access: 2020–2023.

- 20.Jauniaux E., Watson A.L., Hempstock J., Bao Y.P., Skepper J.N. and Burton G.J. (2000) Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 2111–2122 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walgren J.L., Vincent T.S., Schey K.L. and Buse M.G. (2003) High glucose and insulin promote O-GlcNAc modification of proteins, including alpha-tubulin. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284, E424–E434 10.1152/ajpendo.00382.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grzanka A. (2001) Estimation of changes in tubulin induced with etoposide in human leukemia cells line K-562 by immunofluorescence microscope. Neoplasma 48, 48–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T.et al. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsburg S.L. (2004) Eukaryotic MCM proteins: beyond replication initiation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 109–131 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.109-131.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drissi R., Chauvin A., McKenna A., Levesque D., Blais-Brochu S., Jean D.et al. (2018) Destabilization of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex modulates the cellular response to DNA double strand breaks. Cell Cycle 17, 2593–2609 10.1080/15384101.2018.1553336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drissi R., Dubois M.L., Douziech M. and Boisvert F.M. (2015) Quantitative proteomics reveals dynamic interactions of the minichromosome maintenance complex (MCM) in the cellular response to etoposide induced DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 2002–2013 10.1074/mcp.M115.048991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailis J.M. and Forsburg S.L. (2004) MCM proteins: DNA damage, mutagenesis and repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 17–21 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davey M.J., Indiani C. and O'Donnell M. (2003) Reconstitution of the Mcm2-7p heterohexamer, subunit arrangement, and ATP site architecture. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4491–4499 10.1074/jbc.M210511200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shastri V.M., Subramanian V. and Schmidt K.H. (2021) A novel cell-cycle-regulated interaction of the Bloom syndrome helicase BLM with Mcm6 controls replication-linked processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 8699–8713 10.1093/nar/gkab663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polo S.E. and Jackson S.P. (2011) Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 25, 409–433 10.1101/gad.2021311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiden U., Wadsack C., Prutsch N., Gauster M., Weiss U., Frank H.G.et al. (2007) The first trimester human trophoblast cell line ACH-3P: a novel tool to study autocrine/paracrine regulatory loops of human trophoblast subpopulations–TNF-alpha stimulates MMP15 expression. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 137 10.1186/1471-213X-7-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St-Germain L.E., Castellana B., Baltayeva J. and Beristain A.G. (2020) Maternal obesity and the uterine immune cell landscape: the shaping role of inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21,1–28 10.3390/ijms21113776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cindrova-Davies T., Spasic-Boskovic O., Jauniaux E., Charnock-Jones D.S. and Burton G.J. (2007) Nuclear factor-kappa B, p38, and stress-activated protein kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways regulate proinflammatory cytokines and apoptosis in human placental explants in response to oxidative stress: effects of antioxidant vitamins. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 1511–1520 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y., Chen H., Zhang J., Cheng A.S.L., Yu J., To K.F.et al. (2020) MCM family in gastrointestinal cancer and other malignancies: From functional characterization to clinical implication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1874, 188415 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sclafani R.A., Fletcher R.J. and Chen X.S. (2004) Two heads are better than one: regulation of DNA replication by hexameric helicases. Genes Dev. 18, 2039–2045 10.1101/gad.1240604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell S.P. and Dutta A. (2002) DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 333–374 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsao C.C., Geisen C. and Abraham R.T. (2004) Interaction between human MCM7 and Rad17 proteins is required for replication checkpoint signaling. EMBO J. 23, 4660–4669 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z. and Xu X. (2019) Post-translational modifications of the mini-chromosome maintenance proteins in DNA replication. Genes (Basel) 10, 1–23 10.3390/genes10050331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y., Weng C., Zhang H., Sun J. and Yuan Y. (2018) A direct interaction between P53-binding protein 1 and minichromosome maintenance complex in Hepg2 cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 47, 2350–2359 10.1159/000491607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang J., Luo H.L., Pan H., Qiu C., Hao T.F. and Zhu Z.M. (2018) Interaction between RAD51 and MCM complex is essential for RAD51 foci forming in colon cancer HCT116 cells. Biochemistry (Mosc) 83, 69–75 10.1134/S0006297918010091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kettunen J., Silander K., Saarela O., Amin N., Muller M., Timpson N.et al. (2010) European lactase persistence genotype shows evidence of association with increase in body mass index. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1129–1136 10.1093/hmg/ddp561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Protter D.S.W. and Parker R. (2016) Principles and properties of stress granules. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 668–679 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tandl V., Hoch D., Bandres-Meriz J., Nikodijevic S., Desoye G. and Majali-Martinez A. (2021) Different regulation of IRE1alpha and eIF2alpha pathways by oxygen and insulin in ACH-3P trophoblast model. Reproduction 162, 1–10 10.1530/REP-20-0668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peric M., Horvaticek M., Tandl V., Beceheli I., Majali-Martinez A., Desoye G.et al. (2023) Glucose, insulin and oxygen modulate expression of serotonin-regulating genes in human first-trimester trophoblast cell line ACH-3P. Biomedicines 11, 1–15 10.3390/biomedicines11061619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madine M.A., Swietlik M., Pelizon C., Romanowski P., Mills A.D. and Laskey R.A. (2000) The roles of the MCM, ORC, and Cdc6 proteins in determining the replication competence of chromatin in quiescent cells. J. Struct. Biol. 129, 198–210 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leone G., DeGregori J., Yan Z., Jakoi L., Ishida S., Williams R.S.et al. (1998) E2F3 activity is regulated during the cell cycle and is required for the induction of S phase. Genes Dev. 12, 2120–2130 10.1101/gad.12.14.2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Genbacev O., Zhou Y., Ludlow J.W. and Fisher S.J. (1997) Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 277, 1669–1672 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Attie Lab Diabetes Database University of Wisconsin Gene expression in 6 tissues as a function of age, strain and obesity. http://diabetes.wisc.edu/date of access: 2022-2023 [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Kolk B.W., Kalafati M., Adriaens M., van Greevenbroek M.M.J., Vogelzangs N., Saris W.H.M.et al. (2019) Subcutaneous adipose tissue and systemic inflammation are associated with peripheral but not hepatic insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes 68, 2247–2258 10.2337/db19-0560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blueher M. (2020) Metabolically healthy obesity. Endocr. Rev. 411–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nuttall F.Q. (2015) Body mass index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutr. Today 50, 117–128 10.1097/NT.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burton G.J., Watson A.L., Hempstock J., Skepper J.N. and Jauniaux E. (2002) Uterine glands provide histiotrophic nutrition for the human fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 2954–2959 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodesch F., Simon P., Donner C. and Jauniaux E. (1992) Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 80, 283–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prater M., Hamilton R.S., Wa Yung H., Sharkey A.M., Robson P., Abd Hamid N.E.et al. (2021) RNA-Seq reveals changes in human placental metabolism, transport and endocrinology across the first-second trimester transition. Biol. Open 10, 1–17 10.1242/bio.058222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikheev A.M., Nabekura T., Kaddoumi A., Bammler T.K., Govindarajan R., Hebert M.F.et al. (2008) Profiling gene expression in human placentae of different gestational ages: an OPRU Network and UW SCOR Study. Reprod. Sci. 15, 866–877 10.1177/1933719108322425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braun A.E., Muench K.L., Robinson B.G., Wang A., Palmer T.D. and Winn V.D. (2021) Examining sex differences in the human placental transcriptome during the first fetal androgen peak. Reprod. Sci. 28, 801–818 10.1007/s43032-020-00355-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez T.L., Sun T., Koeppel A.F., Lee B., Wang E.T., Farber C.R.et al. (2018) Sex differences in the late first trimester human placenta transcriptome. Biol. Sex Differ. 9, 4 10.1186/s13293-018-0165-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H., Wang L., Wang Y., Zhu Q., Aldo P., Ding J.et al. (2020) Establishment and characterization of a new human first trimester Trophoblast cell line, AL07. Placenta 100, 122–132 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Mass spectrometry proteomics data was deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [16] partner repository with the data set identifier PXD056380.