Abstract

Natural killer group 2 member D ligands (NKG2DLs) are expressed as stress response proteins in cancer cells. NKG2DLs induce immune cell activation or tumor escape responses, depending on their expression. Human pancreatic cancer cells, PANC-1, express membrane MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A/B (mMICA/B), whereas soluble MICB (sMICB) is detected in the culture supernatant. We hypothesized that sMICB saturates NKG2D in NKG2DLow T cells and inhibits the activation signal from mMICB to NKG2D. Knockdown of MICB by siRNA reduced sMICB level, downregulated mMICB expression, maintained NKG2DLow T cell activation, and inhibited NKG2DHigh T cell activation. To maintain mMICB expression and downregulate sMICB expression, we inhibited a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM), a metalloproteinase that sheds MICB. Subsequently, the shedding of MICB was prevented using ADAM17 inhibitors, and the activation of NKG2DLow T cells was maintained. In vivo xenograft model revealed that NKG2DHigh T cells have superior anti-tumor activity. These results elucidate the mechanism of immune escape via sMICB and show potential for the activation of NKG2DLow T cells within the tumor microenvironment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-73712-1.

Keywords: NKG2DL, NKG2D, T cell, MICB, ADAM, Pancreatic tumor, Immunity

Subject terms: Cancer, Cancer microenvironment, Cancer therapy, Tumour immunology

Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy has emerged as a fourth-line treatment for refractory and advanced cancers that have not responded to surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have recently become the standard of care in this field1,2. However, the response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors alone remains low, typically ranging from 10 to 20%3. Additionally, the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors has not been established for pancreatic cancer. Therefore, in order to improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy, the focus has shifted toward targeting activation signals as a new therapeutic strategy that is independent of conventional T-cell receptor signal (Signal 1)4 and co-signals (Signal 2), such as PD-1/PD-L15,6.

Natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) is an activation receptor expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, CD8 + T cells, and γδ T cells7. The NKG2D ligands (NKG2DLs) include MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence (MIC) A and MICB8–10 and six UL-16 binding proteins (ULBP1–ULBP6)11,12. NKG2DLs are typically absent from normal cell surfaces but are induced and overexpressed in tumor cells in response to various stimuli related to cellular stress7,13. The expression of NKG2DLs renders tumors vulnerable to NKG2D-positive (+) lymphocytes14,15, highlighting the pivotal role of the NKG2D system in immune surveillance. However, soluble NKG2DLs downregulate NKG2D expression on NK cells and CD8 T cells, suppressing their activation and contributing to tumor immune evasion16–18. Soluble NKG2DLs are released through proteolytic cleavage, a process known as shedding19–21, and the cleavage of MICA and MICB involves the metalloprotease, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)22–24. The immune escape mechanism through cleavage of membrane ligands presents an appealing target for enhancing the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy, though no effective approach has been identified thus far.

In a prior study, we reported that NKG2D expression in tumor tissue from gastric cancer patients was correlated with overall survival25. Furthermore, majority of NKG2D high cells were CD8 + T cells, suggesting that NKG2D-high CD8 T cells exert an anti-tumor effect and are associated with an improved prognosis. It has been shown that CD8 + T cells are activated via NKG2D17,26; however, it is not clear whether the level of NKG2D expression on CD8 + T cells affects the regulatory mechanism of activation by membrane-type NKG2DLs or the inhibitory mechanism by soluble-type ligands.

In this study, the activities of NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow CD8 T cells were measured separately to show that NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells were more activated than NKG2DLow CD8 T cells in an in vitro co-culture system. NKG2DLow CD8 T cells were more sensitive to the inhibition by soluble MICB (sMICB) than NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells were. Furthermore, NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells had superior anti-tumor activity in an in vivo xenograft model. This study suggests that the regulation of sMICB production may counteract tumor immune evasion and enhance the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy.

Methods

Cell culture

The human pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 (CRL-1469, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and MIA PaCa-2 (CRL-1420, American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, high glucose) containing L-glutamine, phenol red, and sodium pyruvate (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Isolation of NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow T cells by cell sorter

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation. T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-human CD3 (2 µg/ml, clone OKT3) and anti-human CD28 (2 µg/ml, clone CD28.2) antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) in the presence of 100 U/ml interleukin-2 (IL-2, ProSpec, East Brunswick, NJ, USA). They were cultured in 25-cm2 cell culture flasks with iMediam for T (GC Lymphotec, Tokyo, Japan) of total volume of 10 ml and maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2. We diluted this sample by adding fresh culture medium supplemented with 25 U/ml IL-2 on days 4, 7, and 10. On day 14, T cells were used for co-culture with PANC-1. These cells were then sorted using Cell Sorter SH800S (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The top and bottom 10% of the NKG2D expression within CD3 + CD8 + T cells were sorted as the NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow group, respectively, and used for co-culture experiments. For tumor xenograft model, the top and bottom half were sorted as NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow cells, respectively. Antibodies used for cell sorting were listed in supplementary Table 1. All protocols and experiments involving primary PBMCs from healthy donors were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Showa University. Informed consent was obtained from all the volunteers. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Co-culture experiments

PANC-1 cells (3 × 105 cells) were seeded in six-well plates. The next day, the medium was replaced with iMediam for T, and 1.5 × 105 NKG2DHigh or NKG2DLow T cells were added. To knockdown MICA and MICB, siRNA was transfected one day before co-culture. For drug treatment, the PANC-1 cell medium was changed and treated with either GW280264X (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), an inhibitor of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM), an anti-MICA/B antibody (6D4)28,29, or MICB-Fc (BioLegend) four hours before adding T cells. To prepare the GW280264X control, DMSO was added at the same concentration. Mouse IgG2aκ and human IgG1 at the same concentration were used as a control for 6D4 and MICB-Fc, respectively. PANC-1 and T cells were co-cultured for 72 h before analysis. For RT-qPCR analysis of IFNG expression, T cells were isolated by cell sorting. After collecting the floating cells, the adherent cells were trypsinized and collected. Subsequently, the cells were replaced with flow buffer, reacted with Fc-block, and stained with a fluorescently labeled anti-CD3 and anti-CD45 antibodies (Supplementary Table 1). CD3 + and CD45 + cells were isolated as T cells for RNA extraction. For apoptosis assay, collected mixture of PANC-1 and T cells were subjected to the analysis. For cell counting, mixture of cells was stained with trypan blue and manually counted. Small and large cells were defined as T and cancer cells, respectively. When analysing surface activation markers by flow cytometry, unsorted T cells (2 × 106 cells) were co-cultured with PANC-1 cells (2 × 106 cells) in a 10-cm dish. After 24 h co-culture, all cells were collected as described and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Gene silencing via small interfering RNA

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) for MICA and MICB was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). To transfect siRNA into PANC-1 cells, ScreenFect (FUJIFILM Wako) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

Cells was collected and preincubated with Fc-block at 20 °C for 10 min. Fluorescently labeled antibodies were then incubated at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark. For live cell gating, Fixable Viability Stain (FVS) 780 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The flow cytometry was performed on BD FACSLyric (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software 10.7.1 (BD Biosciences). Antibodies used in this study were listed in supplementary Tables 1–3.

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with 7-AAD (Biolegend) was used to determine apoptotic cells together with PE-Cy7 labelled anti-CD3 (clone HIT3a, BioLegend) and APC-labelled anti-CD8a (clone xRPA-Ta, BioLegend) antibodies. Annexin V positive and 7-AAD negative cells within CD3-negative and CD8-negative population were defined as apoptotic PANC-1 cells.

Reverse transcription real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

The mRNA levels were analyzed using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). RNA extraction and reverse transcription were performed using RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan) and High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Multiplex qPCR assays were performed on QuantStudio3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Prime Time Gene Expression Master Mix (Integrated DNA Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). These assays used a FAM-labeled probe for a target gene and a HEX-labeled human HPRT1 probe (assay ID Hs.PT.58v.45621572) as a reference gene. FAM-labeled probes for target genes of interest used in this study are as follows: human MICA (assay ID Hs.PT.58.22397993.g), human MICB (assay ID Hs.PT.58.28367354), human ULBP1 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.19849762), human ULBP2 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.3538345), human ULBP3 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.19536712), human ULBP4 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.24833062.g), human ULBP5 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.26620058), human ULBP6 (assay ID Hs.PT.58.40857249.g), human NKG2D(assay ID Hs.PT.58.) and human interferon (IFN)-γ(assay ID Hs.PT.58.3781960). All probes were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Gene expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method27.

Public database analysis

Cox regression analysis to explore the effect of expression level of eight NKG2D ligands mRNA on overall survival was performed by using R2 Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi) on pancreatic adenocarcinoma (2022-v32) data set from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. The Kaplan Scan tool was used to draw Kaplan-Meier curves where optimal survival cutoff was set based on statistical testing.

Saturation-binding and inhibition experiments using the anti-MICA/B antibody (6D4)

These experiments were adapted from previous studies24,30. For saturation-binding experiments, recombinant human MICB-Fc chimera (BioLegend), an MICB-Fc fusion protein, was solid-phased at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml. A 96-well plate was coated with 50 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (–) containing 5 µg/ml human MICB-Fc fusion proteins at 4 °C overnight. After washing, the samples were blocked with PBS (–) containing 10% FBS. The 6D4 antibody was added at each concentration and allowed to react for 2 h at 20 °C. After washing, the HRP-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was reacted and chromogenized using the 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate set (BioLegend). TMB substrate was added, and the reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. For binding inhibition experiments, the MICB-Fc fusion protein recombinant human MICB-Fc chimera was coated on ELISA plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. After washing, the samples were blocked with PBS (–) containing 10% FBS. The 6D4 antibody was added at each concentration and allowed to react for 2 h at 25 °C. After washing, biotinylated NKG2D-Fc fusion protein (1299-NK-050, R&D Systems) was added. Biotinylation was performed using EZ-Link™ Sulfo-NHS-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After washing, the samples were reacted with avidin-HRP (BioLegend), and color was developed using the TMB substrate set (BioLegend). TMB substrate was added, and the reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Tumor cells were cultured at 3 or 4 × 105 cells (2.0 ml) in six-well culture plates. After 72 h of mono- or co-culture, cell-free supernatants were harvested, and the level of soluble MICB was determined using commercially available sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

PANC-1 xenograft model

Female SCID beige mice (6-week-old) were obtained from Oriental Yeast (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained at a constant temperature (23 ± 1 °C) with a 12 h light/dark cycle under specific pathogen-free conditions. The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Showa University, and all experiments were conducted according to the ARRIVE guidelines. Mice were subcutaneously injected with 3 × 106 PANC-1 cells with Matrigel (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA) in the right flank at day − 12. At day 0 mice received intravenous injection of 1 × 106 sorted NKG2DHigh or NKG2DLow T cells. Tumor size was measured using a caliper twice a week, and tumor volume was determined as length × width2 × 0.5. All mice were euthanized by inhalation of carbon dioxide after the experiment according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020) .

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using an unpaired or paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Differential activation between NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow expressing CD8 T cells in vitro

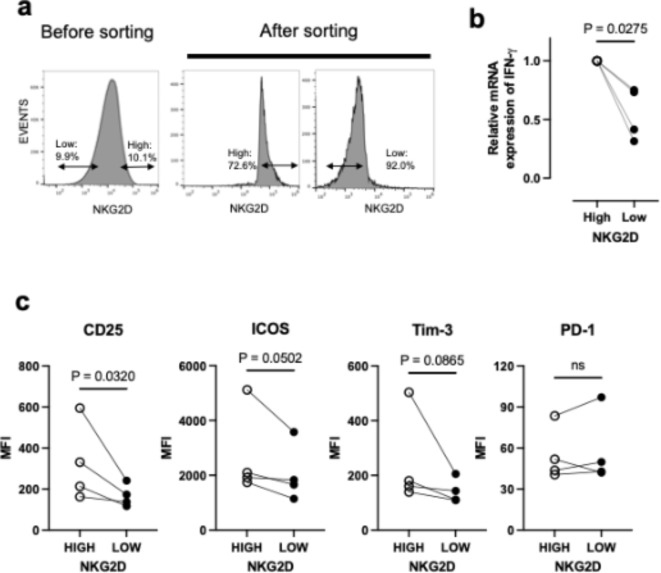

First, we investigated how high or low NKG2D expression affects T cell function in an in vitro co-culture system with cancer cells. NKG2D is a receptor for eight NKG2D ligands in humans. Analysis of public databases showed that in pancreatic cancer patients, only MICB was associated with outcome (Fig. S1a, S1b). Because PANC-1 cells expressed more MICB (Fig. S1c) among the pancreatic cancer cell lines we selected this cell line for experiments in this study. Among PBMC-derived activated T cells, NKG2D was highly expressed in CD8-positive T cells and its expression was heterogeneous (Fig. S2a). The top and bottom 10% of cells for NKG2D expression were isolated by cell sorter and co-cultured with PANC-1 to examine IFNG gene expression as an activation marker (Fig. 1a). Immediately after isolation, T cells showed no difference in IFNG mRNA expression, regardless of whether they expressed more or less NKG2D (Fig. S2b), but after co-culture, IFNG gene expression in NKG2DHigh T cells was higher than that in NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 1b). When T cells were mono-cultured, there was no variation in IFNG expression between NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. S2c), suggesting that this difference was induced by co-culturing with cancer cells. The expression of several cell surface activation markers was also examined by flow cytometry (Fig. S2d). Unsorted activated T cells derived from PBMCs were co-cultured with PANC-1 cells to examine the differential expression of activation markers due to high or low NKG2D expression. CD25 was expressed more in NKG2DHigh than NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 1c). ICOS and Tim-3 also tended to be expressed more in NKG2DHigh than in NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 1c). However, no change in PD-1 expression was observed with NKG2D expression levels (Fig. 1c). These results suggest that NKG2DHigh T cells may be more active than NKG2DLow T cells.

Fig. 1.

NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells are more activated than NKG2DLowcells are. (a) A representative histogram showing NKG2D expression before (left) and after (right) sorting. (b) IFNG mRNA expression of NKG2DHigh or NKG2DLow CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells for 72 h. Data are represented as fold-changes relative to the NKG2DHigh T cells and are means with S.E.M. from four experiments using T cells from two different donors. Each pair of connected dots represents data from a single experiment. (c) Expression of surface activation markers of NKG2DHigh or NKG2DLow CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells. Data are mean with SEM from four independent experiments using T cells from three different donors. Each pair of connected dots represents data from a single experiment.

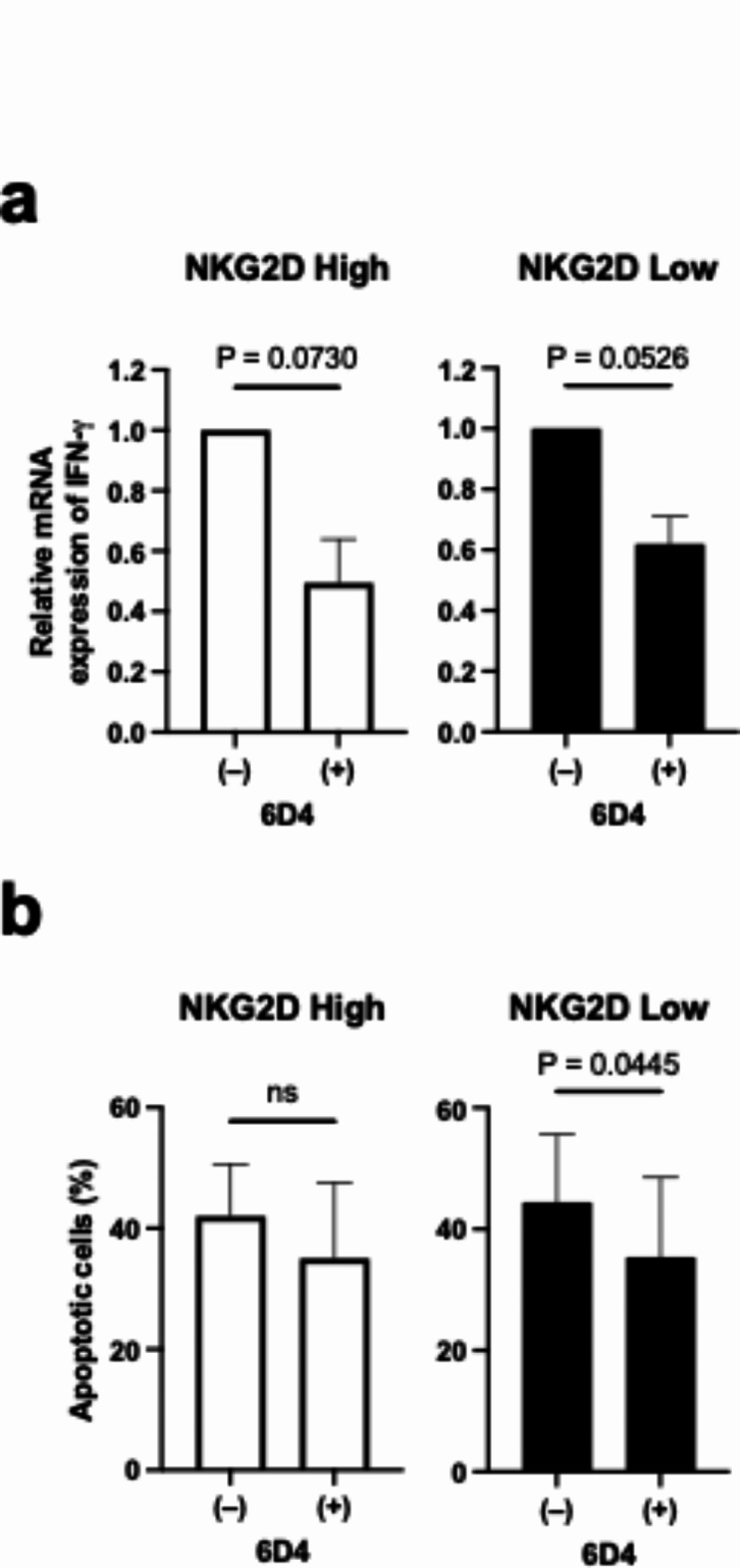

Effect of anti-MICA/B antibodies

Next, to investigate the possibility that the aforementioned NKG2D expression level-dependent activation of CD8-positive T cells is dependent on the NKG2D ligand, the effect of the anti-MICA/MICB antibody, 6D4, was examined. Binding experiments by ELISA showed that at 100 nM 6D4 binding was saturated (Fig. S3a). In contrast, the inhibitory effect on the binding of NKG2D to MICB increased in a concentration-dependent manner, with maximum inhibition observed at 100 nM, although the inhibitory effect was partial and not complete (Fig. S3b). When NKG2DLow or NKG2DHigh T cells were co-cultured with PANC-1 cells in the presence of 100 nM 6D4 antibody, IFNG expression levels were reduced by around 40% or 50% respectively (Fig. 2a). The percentage of PANC-1 cells that underwent apoptosis during co-culture was also reduced in the presence of 6D4 (Fig. 2b). These results suggest that the activation of T cells by co-culture is mediated by the interaction of NKG2D with the NKG2D ligands MICA or MICB.

Fig. 2.

Anti-MICA/MICB antibody 6D4 blocks activation of T cells by coculture. (a) IFNG mRNA expression of NKG2DHigh (left) and NKG2DLow (right) CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells with or without 6D4 antibody at 100 nM. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (b) Apoptotic PANC-1 cells after coculture with NKG2DHigh (left) or NKG2DLow (right) CD8 T cells with or without 6D4 antibody at 100 nM. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments.

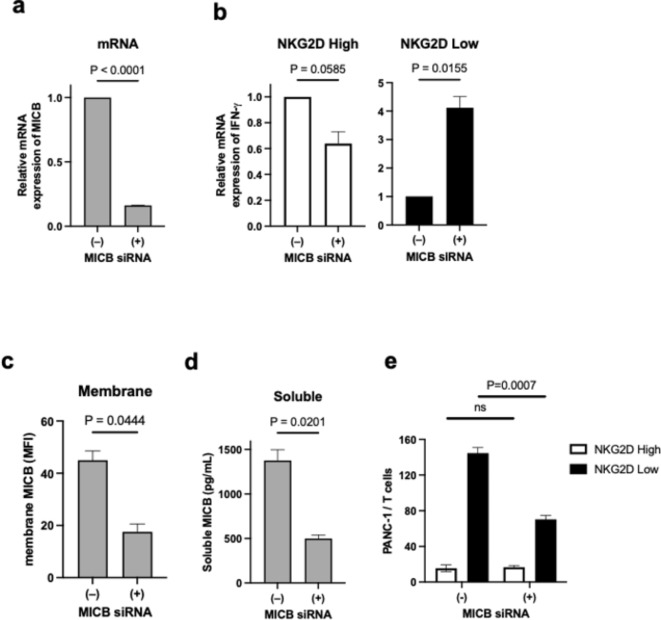

Effects of MICB knockdown

Next, we investigated whether regulating NKG2D ligands on the cancer cell affects T-cell activation. Among eight NKG2D ligands, PANC-1 mainly expresses MICA and MICB at the mRNA level (Fig. S1c). These two ligands were knocked down by siRNA and their effects on T-cell activation during co-culture were investigated. MICA and MICB mRNAs expression were reduced by MICA and MICB siRNAs in PANC-1 compared to control siRNA, respectively (Fig. S4a and 3a). IFNG gene expression after co-culture was unchanged in both NKG2DLow and NKG2DHigh T cells when MICA was downregulated in PANC-1 (Fig. S4b). In contrast, when co-cultured with PANC-1 treated with MICB siRNA, IFNG gene expression was increased by fourfold in NKG2DLow T cells, while that in NKG2DHigh T cells was reduced by half (Fig. 3b). To explore the reason for this, we measured membrane MICB expression in PANC-1 cells treated with MICB siRNA, as well as the concentration of soluble MICB in the culture supernatant. Flow cytometric analysis showed that membrane-type MICB was reduced by half by MICB siRNA (Fig. S4c, 3c). The concentration of soluble MICB in the culture supernatant was also reduced to less than half by MICB siRNA (Fig. 3d). Cytotoxicity to PANC-1 during co-culture was higher in NKG2DHigh T cells than in NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 3e). The addition of MICB siRNA did not alter the cytotoxicity of NKG2DHigh T cells, but it did elevate the cytotoxicity of NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, MICB siRNA did not alter the surface expression of PD-L1 (Fig. S4d), suggesting that PD-L1 to PD-1 signaling is not involved in the differences in T-cell activity due to NKG2D expression levels. These results suggest that the main NKG2D ligand in PANC-1 is MICB and that NKG2DLow T cells are more susceptible to the inhibitory effect of its soluble form.

Fig. 3.

Differential responses of NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells treated withMICB siRNA. (a) MICB mRNA expression of PANC-1 cells treated with control (−) or MICB (+) siRNA. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (b) IFNG mRNA expression of NKG2DHigh (left) and NKG2DLow (right) CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells treated with control (−) or MICB (+) siRNA. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (c) Expression of membrane MICB on PANC-1 cells treated with control (−) or MICB (+) siRNA. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (d) Concentration of soluble MICB in culture supernatant of PANC-1 cells treated with control (−) or MICB (+) siRNA. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (e) Cytotoxicity of NKG2DHigh (open) and NKG2DLow (closed) CD8 T cells against PANC-1 cells treated with control (−) or MICB (+) siRNA. Data are expressed as ratio of PANC-1/T cell number and are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. ns, not significant.

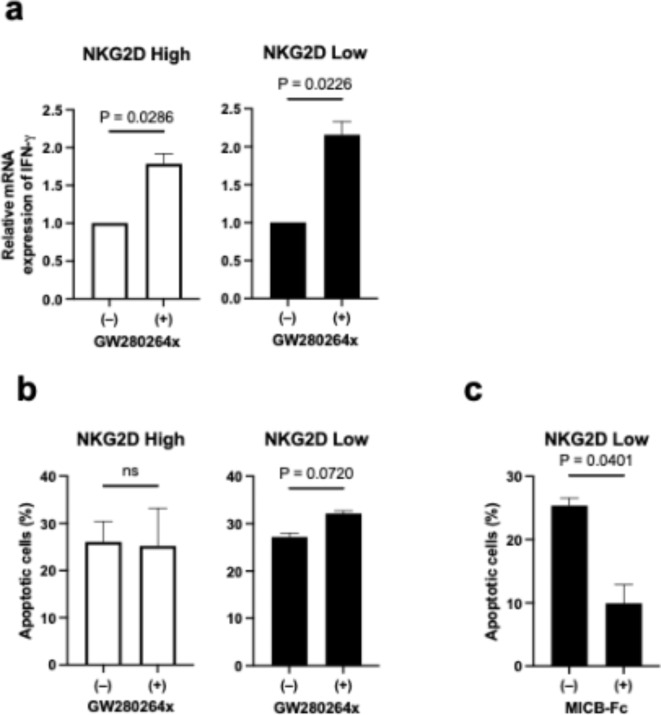

Effects of ADAM inhibitors

Many NKG2D ligands are known to be cleaved by ADAM family proteases to form soluble forms. Therefore, to reduce the production of soluble MICBs, we investigated the effect of the ADAM inhibitor GW280264x on NKG2D-mediated T-cell activation in a co-culture system. GW280264x reduced the concentration of soluble MICBs in PANC-1 culture supernatants in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S5a). At concentrations below 10 µM, the cell viability remained unchanged (Fig. S5b). In the presence of 10 µM GW280264x, IFNG gene expression by co-culture was increased in both NKG2DLow and NKG2DHigh T cells (Fig. 4a). In addition, the percentage of apoptotic PANC-1 cells was increased by GW280264x when co-cultured with NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 4b). These findings suggest that the ADAM inhibitor GW280264x increases the activity of NKG2DLow T cells by reducing soluble MICBs. When a fusion protein of the MICB extracellular domain and the human IgG Fc region was added during co-culture to mimic soluble MICB, the percentage of apoptotic PANC-1 cells during co-culture with NKG2DLow T cells was reduced (Fig. 4c). This result more directly suggests that soluble MICBs suppress NKG2DLow T cells.

Fig. 4.

Soluble MICB regulates the activation of T cells cocultured with PANC-1. (a) IFNG mRNA expression of NKG2DHigh (left) and NKG2DLow (right) CD8 T cells cocultured with PANC-1 cells with or without ADAM inhibitor GW280264x at 10 µM. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (b) Apoptotic PANC-1 cells after coculture with NKG2DHigh (left) and NKG2DLow (right) CD8 T cells with or without ADAM inhibitor GW280264x at 10 µM. Data are mean with SEM from three independent experiments. (c) Apoptotic PANC-1 cells after coculture with NKG2DLow CD8 T cells with or without MICB-Fc fusion protein at 200 ng/mL. Data are mean with SEM from two independent experiments.

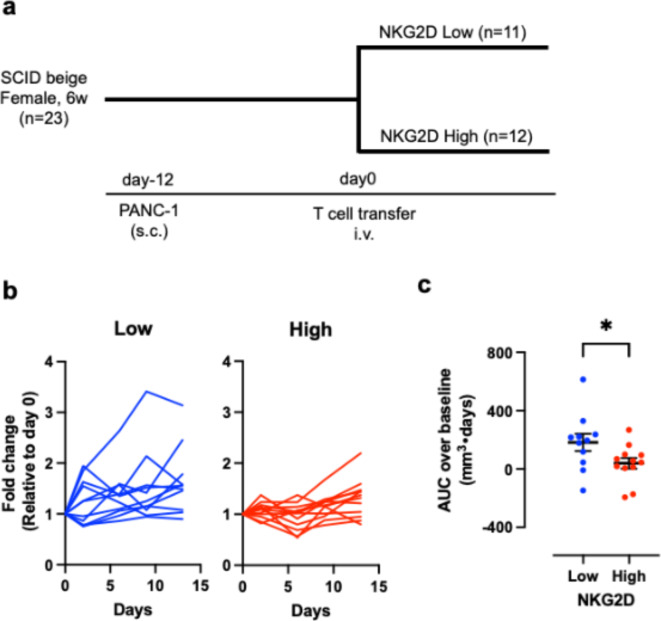

Superior anti-tumor effect of NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells

In vitro data from co-culture systems suggest that among CD8 T cells, NKG2DHigh T cells may have superior anti-tumor activity. In order to prove this concept in vivo, we subcutaneously transplanted PANC-1 cells into SCID beige mice, lacking T and B cells and having dysfunctional NK cells, and transferred NKG2DLow T cells or NKG2DHigh T cells isolated by cell sorter (Fig. 5a). Changes in relative tumor volume over time are shown in Fig. 5b. Although there was inter-individual variation, tumors were larger in mice that received NKG2DLow T cells compared to those did the NKG2DHigh T cells (Fig. 5b). When AUC was compared based on tumor size at the time of T cell transfer, the tumor burden was significantly lower in mice with the NKG2DHigh T cells compared to those with the NKG2DLow T cells (Fig. 5c). Actual tumor size at the time of T-cell transfer was similar in both groups (NKG2DHigh: 51.1 ± 6.8 mm3, n = 11; NKG2DLow: 51.9 ± 5.0 mm3, n = 12, mean ± SEM). These results suggest that NKG2DHigh T cells have superior anti-tumor activity in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Superior anti-tumor activity of NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells in PANC-1 xenograft model. (a) Experimental schedule of PANC-1 xenograft model. SCID beige mice were subcutaneously transplanted with PANC-1 cells (3 × 106) with Matrigel in the right flank at day − 12. At day 0, NKG2DLow or NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells (1 × 106) were intravenously injected. (b) Tumor growth curves of individual mice injected with NKG2DLow (left) and NKG2DHigh (right) CD8 T cells. (c) Tumor burden was expressed as area under the curve (AUC) over baseline (tumor size at day 0) of individual tumor growth curve.

Discussion

NKG2D interactions with NKG2DLs, such as MICB, play an important role in cancer immunity. However, their function has been primarily studied in the context of their anti-tumor activity on NK cells22,32. In our previous study25, we observed that NKG2D + cells infiltrating tumor tissue were CD8 + T cells. Therefore, this study focused on CD8 + T cells. Recent studies have shown that CD8 + T cells exert anti-tumor effects on MHC-I-deficient cancer cells, which are less responsive to cancer immunotherapy via NKG2DL/NKG2D signaling33. It has long been recognized that NKG2D-expressing CD8 + T cells are activated by membrane-type NKG2DLs17,26. However, it has not been fully elucidated whether different levels of NKG2D expression on CD8 + T cells alter their susceptibility to inhibition by soluble NKG2DLs. In this study, we demonstrate that the soluble form of one of the NKG2DLs, MICB, inhibits the activation of NKG2DLow T cells. Knockdown of MICB mRNA in cancer cells resulted in a decrease in the membrane form of MICB on the cell surface and a decrease in the soluble form of MICB in the culture supernatant. Consequently, the activation of NKG2DLow T cells co-cultured with these cancer cells was enhanced four-fold. This finding suggests that the de-inhibition due to the decrease in sMICB affects T cell activity more strongly than the decrease in activation caused by the reduction in membrane MICBs. Notably, the altered T cell activity observed in this co-culture system, even when T cells and cancer cells were not HLA matched, suggests signaling changes other than T cell receptor signals, pointing to NKG2D receptor activation by the NKG2DL. On the other hand, co-culture with cancer cells in which MICB mRNA was knocked down did not enhance the activation of NKG2DHigh T cells; rather, it suppressed it, indicating that NKG2DHigh T cells are less susceptible to the soluble form.

Soluble NKG2DLs are generated when membrane-type NKG2DLs are cleaved by enzymes such as ADAM. MICB is cleaved by ADAM10 and ADAM1714,34, primarily expressed in PANC-1. In this study, we discovered that GW280264 ×35, which selectively inhibits ADAM10 and ADAM1736,37, reduces sMICB production. This reduction in sMICB is accompanied by enhanced activation of NKG2DLow T cells and increased apoptosis of cancer cells during co-culture. This suggests that the sMICB, which inhibits NKG2DLow T cell activation, is generated by ADAM-mediated cleavage. In contrast, for NKG2DHigh T cells, GW280264X did not alter apoptosis of cancer cells during co-culture, indicating that NKG2DHigh T cells are less susceptible to the soluble ligand, similar to the effect of siRNA-based knockdown.

This study suggests that regulating the cleavage of membrane-type NKG2DLs may reactivate NKG2DLow T cells that are inhibited by soluble NKG2DLs. As demonstrated in this study, ADAM inhibitors may increase membrane-type NKG2DLs by blocking NKG2DL cleavage. However, since ADAM is expressed outside of cancer cells, as shown in previous studies38–41, ADAM inhibitors may not be effective therapeutic agents. Future studies are needed to elucidate the regulatory mechanism of ADAM activation specific to cancer cells in order to control this mechanism.

This study also suggests that sMICB may serve as a prognostic marker for pancreatic cancer. Correlations between soluble NKG2DLs detected in the serum and prognosis have been reported in several cancer types20,42. Higher serum soluble ULBP2 levels have been associated with a worse prognosis in lung cancer43. Additionally, it has been reported that soluble NKG2DL levels in the serum of melanoma patients inversely correlate with survival and serve as important biomarkers for anti-PD-1 therapy44. Our results suggest that sMICB levels in the blood may be a new biomarker for pancreatic cancer immunotherapy.

Another major finding of this study is that NKG2D expression levels in CD8 T cells correlate with anti-tumor activity in in vivo xenograft model. This is consistent with our previous study24 in which NKG2D-positive CD8 T cells in gastric cancer tissue specimens correlated with a favourable prognosis. This response is independent of the binding of the MHC-peptide complex to the TCR and can occur if T cells are present in the vicinity of cancer cells. Thus, the recruitment of NKG2DHigh CD8 T cells from blood to tumor tissue would be a novel cancer therapy. Furthermore, the fact that expression levels of PD-1 were similar between NKG2DHigh and NKG2DLow T cells indicates that these two signals are independent. This means that therapies targeting the NKG2DLs-NKG2D interaction may be effective in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-L1/PD-1.

In this study, the regulation of T-cell activity by soluble MICB was evaluated mainly by using the expression level of IFNG mRNA as an indicator. However, mRNA expression levels are not solely determined by transcription, but also by stability and other factors. Therefore, it should be noted that there are limitations in discussing T cell activation based solely on mRNA levels. In addition, since these results were shown only in in vitro co-culture systems, it is yet to be determined whether similar regulation occurs in vivo setting.

In conclusion, our study reveals that MICB, the primary ligand of pancreatic cancer cells, inhibits the activation of NKG2DLow T cells by shedding through ADAM. This suggests that NKG2DLow T cells, which are suppressed by sMICB, can be reactivated, potentially enhancing the anti-tumor effect of NKG2D + CD8 + T cells. Although the development of patient-specific methods to stimulate NKG2DLow T cells is needed, our study suggests that the regulation of sMICB, a suppressor of NKG2DLow T cells, may be an effective therapeutic target.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage for their assistance with English language editing. We thank Showa University Clinical Medicine Joint Research Laboratory for the use of BD FACSLyric.

Abbreviations

- ADAM

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FCM

Flow cytometry

- IFN-γ

Interferon gamma

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- MIC

MHC class I chain-related gene

- mMIC

Membrane MHC class I chain-related gene

- sMIC

Soluble MHC class I chain-related gene

- NK cell

Natural killer cell

- NKG2D

Natural killer group 2 member D

- NKG2DL

Natural killer group 2 member D ligand

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription real-time qPCR

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

- ULBP

UL-16 binding protein

Author contributions

KY conceived the study; HT, KY, and AK designed and performed the experiments and interpreted the data; MM, MH, YN, JI, YB, KT, EF, YM, AS and MS wrote the manuscript; KN, SW, HK, MT, SK, TT, YKu, and YKi edited the manuscript; YH, TT, HA, TI, RS, SK, AH, NH, and TS performed the immunohistochemistry of tumor samples; HT, MH, AK, and KY summarized the data analysis; KY holds responsibility for the contents of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: 21K08785).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Topalian, S. L. et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.366, 2443–2454 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer, J. R. et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.366, 2455–2465 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferris, R. L. et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med.375, 1856–1867 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, D. S. & Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 39, 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamanishi, J. et al. IPD-1/PD-L1 blockade in cancer treatment: Perspectives and issues. Int. J. Clin. Oncol.21, 462–473 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ai, L., Xu, A. & Xu, J. Roles of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: Signaling, cancer, and beyond. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1248, 33–59 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raulet, D. H. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat. Rev. Immunol.3, 781–790 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahram, S., Bresnahan, M., Geraghty, D. E. & Spies, T. A second lineage of mammalian major histocompatibility complex class I genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 91, 6259–6263 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groh, V. et al. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 96, 6879–6884 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stastny, P. Introduction: MICA/MICB in innate immunity, adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, cancer, and in the immune response to transplants. Hum. Immunol.67, 141–144 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Gazzar, A., Groh, V. & Spies, T. Immunobiology and conflicting roles of the human NKG2D lymphocyte receptor and its ligands in cancer. J. Immunol.191, 1509–1515 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosman, D. et al. ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity. 14, 123–133 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry, A. R. & O’Callaghan, C. A. Regulation of ligands for the activating receptor NKG2D. Immunology. 121, 439–447 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chitadze, G. et al. Shedding of endogenous MHC class I-related chain molecules a and B from different human tumor entities: Heterogeneous involvement of the a disintegrin and metalloproteases 10 and 17. Int. J. Cancer. 133, 1557–1566 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayakawa, Y. Targeting NKG2D in tumor surveillance. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 16, 587–599 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nausch, N. & Cerwenka, A. NKG2D ligands in tumor immunity. Oncogene. 27, 5944–5958 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groh, V., Wu, J., Yee, C. & Spies, T. Tumor-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 419, 734–738 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konagai, A. et al. Correlation between NKG2DL expression and antitumor effect of protein-bound polysaccharide-K in tumor-bearing mouse models. Anticancer Res.37, 4093–4101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salih, H. R., Rammensee, H. G. & Steinle, A. Cutting edge: Down-regulation of MICA on human tumors by proteolytic shedding. J. Immunol.169, 4098–4102 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salih, H. R., Goehlsdorf, D. & Steinle, A. Release of MICB molecules by tumor cells: Mechanism and soluble MICB in sera of cancer patients. Hum. Immunol.67, 188–195 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, J. D., Atteridge, C. L., Wang, X., Seya, T. & Plymate, S. R. Obstructing shedding of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related gene B prevents tumor formation. Clin. Cancer Res.15, 632–640 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer, S. et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 285, 727–729 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldhauer, I. et al. Tumor-associated MICA is shed by ADAM proteases. Cancer Res.68, 6368–6376 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes, M. A., Li, P., Petersdorf, E. W. & Strong, R. K. Structural studies of allelic diversity of the MHC class I homolog MIC-B, a stress-inducible ligand for the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D. J. Immunol.169, 1395–1400 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamei, R. et al. Expression levels of UL16 binding protein 1 and natural killer group 2 member D affect overall survival in patients with gastric cancer following gastrectomy. Oncol. Lett.15, 747–754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groh, V. et al. Costimulation of CD8alphabeta T cells by NKG2D via engagement by MIC induced on virus-infected cells. Nat. Immunol.2, 255–260 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groh, V., Steinle, A., Bauer, S. & Spies, T. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial gammadelta T cells. Science. 279, 1737–1740 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groh, V., Bruhl, A., El-Gabalawy, H., Nelson, J. L. & Spies, T. Stimulation of T cell autoreactivity by anomalous expression of NKG2D and its MIC ligands in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 9452–9457 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hundhausen, C. et al. The disintegrin-like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood. 102(4), 1186–1195 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chitadze, G. et al. Shedding of endogenous MHC class I-related chain molecules a and B from different human tumor entities: Heterogeneous involvement of the a disintegrin and metalloproteases 10 and 17. Int. J. Cancer. 133(7), 1557–1566 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jinushi, M. et al. Critical role of MHC class I-related chain A and B expression on IFN-alpha-stimulated dendritic cells in NK cell activation: Impairment in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Immunol.170, 1249–1256 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerner, E. C. et al. CD8+ T cells maintain killing of MHC-I-negative tumor cells through the NKG2D-NKG2DL axis. Nat. Cancer. 4, 1258–1272 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludwig, A. et al. Metalloproteinase inhibitors for the disintegrin-like metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that differentially block constitutive and phorbol ester-inducible shedding of cell surface molecules. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen.8, 161–171 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dutta, I. et al. Postovit LM and Siegers GM: ADAM protease inhibition overcomes resistance of breast cancer stem-like cells to γδ T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Lett.496, 156–168 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hundhausen, C. et al. The disintegrin-like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood. 102, 1186–1195 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommer, D. et al. ADAM17-deficiency on microglia but not on macrophages promotes phagocytosis and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Brain Behav. Immun.80, 129–145 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein, H. G. et al. Comparative localization of ADAMs 10 and 15 in human cerebral cortex normal aging, Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. J. Neurocytol. 32, 153–160 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukata, Y. et al. Disruption of LGI1-linked synaptic complex causes abnormal synaptic transmission and epilepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 3799–3804 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakatsuki, S., Kurisaki, T. & Sehara-Fujisawa, A. Lipid rafts identified as locations of ectodomain shedding mediated by Meltrin beta/ADAM19. J. Neurochem. 89, 119–123 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asakura, M. et al. Cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited by antagonism of ADAM12 processing of HB-EGF: Metalloproteinase inhibitors as a new therapy. Nat. Med.8, 35–40 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang, B., Sikorski, R., Sampath, P. & Thorne, S. H. Modulation of NKG2D-ligand cell surface expression enhances immune cell therapy of cancer. J. Immunother. 34, 289–296 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi, K. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic impact of serum-soluble UL16-binding protein 2 in lung cancer patients. Cancer Sci.103, 1405–1413 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maccalli, C. et al. Soluble NKG2D ligands are biomarkers associated with the clinical outcome to immune checkpoint blockade therapy of metastatic melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 6, e1323618 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.