Abstract

Data on cholestasis and biliary injury in patients with COVID-19 are scarce. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of cholestasis and factors associated with its development and outcome in critically ill patients with COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In this retrospective exploratory study, COVID-19 patients with ARDS admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) at the Medical University of Vienna were evaluated for the development of cholestasis defined as an alkaline phosphatase level of 1.67x upper limit of normal for at least three consecutive days. Simple and multiple logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate parameters associated with development of cholestasis and survival. Of 225 included patients 119 (53%) developed cholestasis during ICU stay. Patients with cholestasis had higher peak levels of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, bilirubin and inflammation parameters. Factors independently associated with cholestasis were extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, ketamine use, high levels of inflammation parameters and disease severity. Presence of cholestasis and peak ALP levels were independently associated with worse ICU and 6-month survival. Development of cholestasis is a common complication in critically ill COVID-19 patients and represents a negative prognostic marker for survival. It is associated with disease severity and specific treatment modalities of intensive care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-73948-x.

Keywords: COVID-19, ICU, Liver injury, Cholestasis, Ketamine

Subject terms: Biliary tract disease, Liver diseases

Introduction

COVID-19-associated liver injury comprises a broad spectrum of different pathogenetic mechanisms. Besides direct cytotoxic effects following active viral replication of SARS-CoV-21, immune mediated damage due to systemic inflammation and cytokine storm may be involved2–5. Furthermore, hypoxic hepatitis and ischemic cholangitis in the presence of severe ARDS may contribute to hepatic and biliary injury3. Drug induced liver injury (DILI) as a consequence of polypharmacy during the ICU stay may be another reason for COVID-19 associated liver disease, and lastly, preexisting hepatopathy might exacerbate during infection3.

Elevated transaminases were found in up to 76.3% of patients with COVID-196–9. According to recent meta-analyses the pooled rate of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 20-22.5% and 14.6–20.1%, respectively, and was associated with worse outcomes6. While cholestatic patterns of liver disease were initially considered to be rare, a recent analysis identified elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (γGT) in 6.1% and 21.1%, respectively6. Moreover, a biphasic course with initially elevated transaminases followed by cholestasis might reflect an inflammatory-induced cholestasis at the hepatocellular/canalicular level or a more pronounced biliary damage at advanced disease stages10. Data on clinical outcome of liver injury – particularly cholestasis – in patients with COVID-19 are scarce.

There is growing evidence of biliary tract injury during SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may result in development of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC)11–16. However, cholestasis in critically ill patients is not restricted to the bile duct level17,18 and several factors, including disease severity of the critical illness, parenteral nutrition and ketamine use, may contribute to the development of cholestasis in critically ill patients19–25.

The aim of this retrospective exploratory study was to evaluate the prevalence of cholestasis, risk factors for its development and its impact on clinical outcome parameters in patients with SARS-CoV-2 associated ARDS treated in an ICU at a tertiary referral center.

Patients and methods

Study design and cohort

We conducted a retrospective exploratory study of COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU at a large tertiary ECMO-referral center in Vienna, Austria (Medical University of Vienna/Vienna General Hospital). During the pandemic, a total of six ICUs of the Departments of Internal Medicine I and III, and the Department of Anesthesia and General Intensive Care were dedicated to receive COVID-19 patients. All adult patients (18 years and older) with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 associated ARDS treated in one of these ICUs between March 1st, 2020 and March 31st, 2022 were included in the study. ARDS was defined according to the Berlin definition26. Patients with post-COVID-19 ARDS negative for SARS-CoV-2 for longer than 2 weeks before ICU admission at our center were excluded. To evaluate alterations in cholestasis parameters and liver chemistries during ICU stay the observation period was set from ICU admission to ICU discharge from our center or death. Data for the determination of 6-month survival were retrieved from the Austrian death data registry.

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (ethic vote number: 1872/2021) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in recent definition. Given the retrospective design of the study, informed consent statements were waived by the local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna. This study followed the recommendations of the STROBE initiative for reporting observational studies in epidemiology.

Laboratory parameters and cholestasis

All laboratory parameters including liver chemistries (AST, ALT, ALP, γGT, and total bilirubin), global tests of coagulation and blood cell counts were assessed by routine laboratory assays once daily. The local laboratory thresholds for men and women were used to determine the upper limit of normal (ULN) for parameters of hepatocellular (AST and ALT) and cholestatic liver injury (ALP, γGT, and bilirubin). Laboratory parameters were recorded as first available value at ICU admission and last available value prior to ICU discharge or death. In addition, peak or nadir levels (as applicable) of all relevant laboratory parameters were documented.

The occurrence of cholestasis was defined as an ALP level of > 1.67x ULN for at least three consecutive days during ICU stay27. All included patients’ medication during ICU stay was assessed for the use of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).

Data collection

Data were extracted from electronic patient charts (IntelliSpace Critical Care and Anesthesia, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands). This patient data management system is routinely used at all ICUs at the Medical University of Vienna to document patient characteristics [age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), vital signs, comorbidities/underlying disease (including preexisting diabetes mellitus, obesity, arterial hypertension, chronic lung disease, chronic liver disease and chronic kidney disease)] and laboratory tests (daily routine blood chemistry, global tests of coagulation and blood cell count). In addition, complete information on ICU-specific parameters/therapies including fluid balance, medication, nutrition and artificial life support [invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), renal replacement therapy (RRT), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)] is provided. In order to quantify the severity of critical illness and extent of organ dysfunction for patients admitted to the ICU, simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) II, sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA) and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation score (APACHE) II were calculated within the first 24 h upon ICU admission. The lowest recorded value of the PaO2/FiO2 ratio (= nadir of the ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen and the fraction of inspired oxygen) for each patient was used to grade ARDS severity (i.e. mild, moderate, severe) according to the Berlin definition26.

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of cholestasis and factors associated with its presence/development in patients with COVID-19 ARDS requiring ICU admission. Predefined secondary objectives were the identification of parameters associated with ICU- and 6-month overall survival in patients requiring critical care due to COVID-19 ARDS.

Categorical variables are given as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed or median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed parameters as assessed by visual inspection of histograms. For comparison of categorical variables, the χ2- or Fisher’s exact test was used. Continuous variables were compared between groups by Mann Whitney U tests. Correlation analysis was carried out by Spearman’s rank test. All tests were two-sided, where appropriate, and a p-value of 0.05 was used as level of significance. For evaluation of factors that were independently associated with the presence of cholestasis or survival we performed simple and multiple logistic regression models with backward variable selection including all clinically reasonable variables. Due to the exploratory character of the study, no adaptations of the p-values for multiple hypotheses were performed.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM, New York, NY, USA), R 4.2.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Basic characteristics of the study cohort

In total, 225 patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 associated ARDS were included in this study. Patients were predominantly male (n = 154, 68%) with a mean age of 56.2±12.1 years. Median SOFA, SAPSII and APACHEII score upon ICU admission was 8 (7–10), 41 (34–51) and 19 (14–22), respectively. The median ICU length of stay (LOS) was 30 days (15–50). ICU survival was 63% (n = 141). A detailed description of the clinical characteristics, comorbidities and all ICU-specific therapies is displayed in Table 1. Chronic liver disease was documented in 18 patients, most of them exhibited metabolic dysfunction associated liver disease (MASLD; n = 14), followed by liver cirrhosis (n = 3) and alcoholic liver disease (n = 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without cholestasis.

| Variable | All patients | Cholestasis | No cholestasis | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 225 | 119 (53) | 106 (47) | |

| Male, n (%) | 154 (68) | 79 (66) | 75 (71) | 0.575 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 56.2 (12.1) | 57.1 (9.8) | 55.2 (14.3) | 0.248 |

| BMI, kg/m2 mean (SD) | 32 (7.5) | 31.4 (6.3) | 32.8 (8.7) | 0.156 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 67 (30) | 40 (34) | 27 (25) | 0.235 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 100 (44) | 53 (44) | 48 (45) | 0.917 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 128 (57) | 72 (61) | 56 (53) | 0.305 |

| Chron. lung disease, n (%) | 30 (13) | 16 (13) | 14 (13) | 0.999 |

| Chron. liver disease, n (%) | 18 (8) | 12 (10) | 6 (6) | 0.33 |

| Chron. kidney disease, n (%) | 18 (8) | 12 (10) | 6 (6) | 0.33 |

| SOFA, median (IQR) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (7–10) | 0.304 |

| SAPSII, median (IQR) | 41 (34–51) | 40 (34–46) | 43 (33–53) | 0.12 |

| APACHEII, median (IQR) | 19 (14–22) | 18 (15–23) | 19 (13–22) | 0.889 |

| P/F ratio nadir, median (IQR) | 60 (52–71) | 57 (50–65) | 64 (53–76) | 0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days), median (IQR) | 30 (15–50) | 40 (28–66) | 18 (8–31) | < 0.001 |

| 28-day survival, n (%) | 167 (74) | 87 (73) | 80 (75) | 0.801 |

| ICU survival, n (%) | 141 (63) | 66 (55) | 75 (71) | 0.026 |

| 6-month survival, n (%) | 132 (59) | 61 (51) | 71 (67) | 0.024 |

| IMV, n (%) | 210 (93%) | 118 (99%) | 92 (87%) | < 0.001 |

| IMV (days), median (IQR) | 28 (12–45) | 38 (24–58) | 15 (7–29) | < 0.001 |

| Prone position, n (%) | 177 (79) | 100 (85) | 77 (73) | 0.055 |

| Prone position (days), median (IQR) | 4 (1–8) | 5 (2–9) | 3 (0–6) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 130 (58) | 93 (78) | 37 (35) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO (days), median (IQR) | 23 (13–35) | 25 (14–36) | 15 (10–34) | 0.114 |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 209 (93) | 117 (98) | 92 (87) | 0.002 |

| Norepinephrine (days), median (IQR) | 12 (6–26) | 19 (9–32) | 7 (2–15) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressin, n (%) | 38 (17) | 23 (19) | 15(14) | 0.392 |

| Dobutamine, n (%) | 34 (15) | 20 (17) | 14 (13) | 0.571 |

| Ketamine, n (%) | 184 (82%) | 111 (93) | 73 (69) | < 0.001 |

| Ketamine (days), median (IQR) | 10 (3–17) | 14 (9–21) | 6 (0–11) | < 0.001 |

| Neuromuscular blockade, n (%) | 144 (64) | 87 (73) | 57 (54) | 0.004 |

| Neuromuscular blockade (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 3 (0–7) | 2 (0–4) | < 0.001 |

| Parenteral nutrition, n (%) | 149 (66) | 90 (76) | 59 (56) | 0.003 |

| Parenteral nutrition (days), median (IQR) | 5 (0–11) | 7 (2–15) | 2 (0–7) | < 0.001 |

| UDCA, n (%) | 107 (48) | 87 (73) | 20 (19) | < 0.001 |

| UDCA (mg/kg BW), median (IQR) | 15 (10–18) | 15 (11–18) | 11 (7–16) | 0.009 |

n., number of patients; %, percent; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score; SAPSII, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; APACHEII, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; BW, body weight.

Trajectory of laboratory parameters

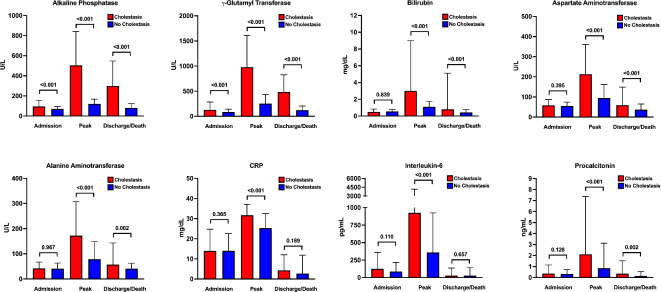

A total of 119 patients (53%) were found to develop laboratory signs of cholestasis during ICU stay. Alterations of different laboratory parameters at three occasions (ICU admission, peak, last value prior to ICU discharge/death) over the course of the ICU stay regarding development of cholestasis are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Patients with cholestasis had higher ALP and γGT values at all three time points and higher bilirubin, AST and ALT levels at peak and last timepoints compared to patients without cholestasis.

Fig. 1.

Liver and inflammatory parameters in critically ill COVID-19 patients according to cholestasis development. Comparison of liver chemistries (ALP, γGT, bilirubin, AST and ALT) and inflammatory parameters (CRP, IL-6 and PCT) between patients with (red) and without cholestasis (blue) at three different time points (i.e. admission, peak values and discharge/death) as indicated. Bars represent median values; vertical lines indicate interquartile range.

Inflammation parameters (CRP, IL-6 and PCT) were not different between the groups at ICU admission (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Peak values of IL-6 and PCT were higher in patients with cholestasis (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Factors associated with cholestasis

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without cholestasis are shown in Table 1. Patients with cholestasis had a longer ICU LOS (40 vs. 18 days; p < 0.001) and more often required IMV (99% vs. 87%; p < 0.001) and ECMO (78% vs. 35%; p < 0.001). Further, cholestatic patients more often received norepinephrine (98% vs. 87%; p = 0.002), ketamine (93% vs. 69%; p < 0.001), continuous neuromuscular blockade (73% vs. 54%; p = 0.004) and parenteral nutrition (76% vs. 56%; p = 0.003) compared to patients without cholestasis. In addition, we found significant differences in the duration of IMV (38 vs. 15 days; p < 0.001), prone positioning (5 vs. 3 days; p < 0.001), norepinephrine use (19 vs. 7 days; p < 0.001), ketamine use (14 vs. 6 days; p < 0.001), neuromuscular blockade (3 vs. 2 days; p < 0.001), and parenteral nutrition (7 vs. 2 days; p < 0.001). Disease severity scores on admission (SOFA, SAPSII and APACHEII) were not different between the groups. PaO2/FiO2 ratio nadir during ICU stay was significantly lower in cholestatic patients (57 vs. 64; p = 0.001).

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, duration of ketamine use (OR: 1.103; CI: 1.043–1.171; p = 0.001), ICU LOS (OR: 1.042; CI: 1.018–1.070; p = 0.001), ECMO treatment (OR: 3.094; CI: 1.366–7.140; p = 0.007), peak IL-6 (OR: 1.411; CI: 1.085–1.861; p = 0.012) and SOFA score at ICU admission (OR: 1.228; CI: 1.048–1.457; p = 0.014) remained independent risk factors for the development of cholestasis in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Detailed results of the simple and multiple logistic regressions are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses of factors associated with the development of cholestasis.

| Parameter | Simple | Multiple | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| ECMO | 6.670 (3.741–12.215) | < 0.001 | 3.094 (1.366–7.140) | 0.007 |

| ICU LOS | 1.045 (1.031–1.062) | < 0.001 | 1.042 (1.018–1.070) | 0.001 |

| Cumulative Days Norepinephrine | 1.059 (1.037–1.086) | < 0.001 | 0.945 (0.900–0.990) | 0.019 |

| Cumulative Days of ketamine | 1.134 (1.091–1.184) | < 0.001 | 1.103 (1.043–1.171) | 0.001 |

| Cumulative Days of NMB | 1.107 (1.039–1.188) | 0.003 | ||

| Cumulative Days of PN | 1.080 (1.041–1.126) | < 0.001 | ||

| Cumulative Days of IMV | 1.050 (1.034–1.068) | < 0.001 | ||

| Peak CRP | 1.065 (1.036–1.097) | < 0.001 | ||

| Peak IL-6* | 1.596 (1.322–1.959) | < 0.001 | 1.411 (1.085–1.861) | 0.012 |

| Peak PCT* | 1.507 (1.251–1.837) | < 0.001 | ||

| P/F ratio nadir | 0.985 (0.972–0.996) | 0.013 | ||

| Prone position | 1.982 (1.041–3.847) | 0.039 | 0.472 (0.162–1.321) | 0.159 |

| SOFA Score | 1.084 (0.975–1.211) | 0.141 | 1.228 (1.048–1.457) | 0.014 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; PN, parenteral nutrition; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; NMB, neuromuscular blockade; PCT, procalcitonin; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2 ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score.

*logarithmized.

Factors associated with ICU survival and long-term survival

Differences between ICU survivors and non-survivors are depicted in Table 3. ICU non-survivors were older (61.7 vs. 53.0 years; p < 0.001) and showed higher SOFA (9 vs. 7; p < 0.001), SAPSII (46 vs. 38; p < 0.001) and APACHEII (21 vs. 17; p < 0.001) scores. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio nadir was lower in ICU non-survivors (52 vs. 64; p = 0.001). ICU non-survivors had a higher rate of IMV (100% vs. 89%; p = 0.005), norepinephrine treatment (100% vs. 89%; p = 0.003) and vasopressin use (31% vs. 9%; p < 0.001). In addition, duration of prone positioning (5 vs. 4 days; p = 0.047), ECMO therapy (22 vs. 14 days; p < 0.001), norepinephrine treatment (15 vs. 10 days; p = 0.005), continuous neuromuscular blockade (3 vs. 2 days; p = 0.041) and parenteral nutrition (7 vs. 4 days; p = 0.015) was significantly longer in the non-survivor group. ICU non-survivors more frequently developed cholestasis (63% vs. 47%; p = 0.026).

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to ICU survival status.

| Variable | All patients | Survivors | Non-survivors | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 225 | 141 (63) | 84 (37) | |

| Male, n (%) | 154 (68) | 96 (68) | 58 (69) | 0.998 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 56.2 (12.1) | 53.0 (12.3) | 61.7 (9.8) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 mean (SD) | 32 (7.5) | 32.1 (7.3) | 32.0 (7.9) | 0.951 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 67 (30) | 37 (26) | 30 (36) | 0.176 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 100 (44) | 59 (42) | 41 (49) | 0.38 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 128 (57) | 71 (50) | 57 (68) | 0.015 |

| Chron. lung disease, n (%) | 30 (13) | 14 (10) | 16 (19) | 0.081 |

| Chron. liver disease, n (%) | 18 (8) | 7 (5) | 11 (13) | 0.055 |

| Chron. kidney disease, n (%) | 18 (8) | 7 (5) | 11 (13) | 0.055 |

| SOFA, median (IQR) | 8 (7–10) | 7 (7–9) | 9 (7–11) | < 0.001 |

| SAPSII, median (IQR) | 41 (34–51) | 38 (32–46) | 46 (39–53) | < 0.001 |

| APACHEII, median (IQR) | 19 (14–22) | 17 (13–21) | 21 (16–25) | 0.001 |

| P/F ratio nadir, median (IQR) | 60 (52–71) | 64 (57–76) | 52 (47–61) | < 0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days), median (IQR) | 30 (15–50) | 32 (16–56) | 28 (14–41) | 0.081 |

| IMV, n (%) | 210 (93) | 126 (89) | 84 (100) | 0.005 |

| IMV (days), median (IQR) | 28 (12–45) | 28 (12–48) | 26 (11–39) | 0.345 |

| Prone position, n (%) | 177 (79) | 107 (76) | 70 (83) | 0.25 |

| Prone position (days), median (IQR) | 4 (1–8) | 4 (1–8) | 5 (2–9) | 0.047 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 130 (58) | 76 (54) | 54 (64) | 0.166 |

| ECMO (days), median (IQR) | 23 (13–35) | 14 (0–32) | 22 (9–32) | < 0.001 |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 209 (93) | 125 (89) | 84 (100) | 0.003 |

| Norepinephrine (days), median (IQR) | 12 (6–26) | 10 (4–23) | 15 (9–29) | 0.005 |

| Vasopressin, n (%) | 38 (17) | 12 (9) | 26 (31) | < 0.001 |

| Dobutamine, n (%) | 34 (15) | 17 (12) | 17 (20) | 0.143 |

| Ketamine, n (%) | 184 (82%) | 110 (78) | 74 (88) | 0.086 |

| Ketamine (days), median (IQR) | 10 (3–17) | 9 (3–15) | 12 (5–20) | 0.052 |

| Neuromuscular blockade, n (%) | 144 (64) | 85 (60) | 59 (70) | 0.174 |

| Neuromuscular blockade (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–5) | 3 (0–6) | 0.041 |

| Parenteral nutrition, n (%) | 149 (66) | 88 (62) | 61 (73) | 0.156 |

| Parenteral nutrition (days), median (IQR) | 5 (0–11) | 4 (0–9) | 7 (0–14) | 0.015 |

| Cholestasis, n (%) | 119 (53) | 66 (47) | 53 (63) | 0.026 |

| UDCA, n (%) | 107 (48) | 61 (43) | 46 (55) | 0.100 |

| UDCA (mg/kg BW), median (IQR) | 15 (10–18) | 15 (10–18) | 14 (9–17) | 0.323 |

n., number of patients; %, percent; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; Surv., survivors; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score; SAPSII, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; APACHEII, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; BW, body weight.

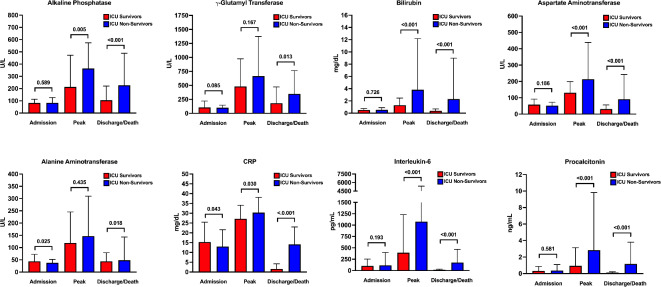

The time course of various laboratory parameters during the ICU stay according to ICU survival is displayed in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2. Except for ALT and CRP, there were no differences regarding ICU survival in liver chemistries or inflammation parameters at ICU admission. ICU non-survivors had higher peak values of ALP, bilirubin, AST, CRP, IL-6 and PCT (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Liver and inflammatory parameters in critically ill COVID-19 patients according to ICU survival. Comparison of liver chemistries (ALP, γGT, bilirubin, AST and ALT) and inflammatory parameters (CRP, IL-6 and PCT) between ICU survivors (red) and ICU non-survivors (blue) at three different time points (i.e. admission, peak values and discharge/death) as indicated. Bars represent median values; vertical lines indicate interquartile range.

In a next step, we evaluated potential parameters associated with ICU survival by performing simple and multiple logistic regression analysis with backward variable selection. Shorter duration of norepinephrine use (OR: 0.932; CI: 0.886–0.976; p = 0.004), longer ICU LOS (OR: 1.061; CI: 1.037–1.089; p < 0.001), lower peak AST (OR: 0.619; CI: 0.396–0.937, p = 0.028), lower peak IL-6 (OR: 0.659; CI: 0.474–0.901; p = 0.010) and higher PaO2/FiO2 ratio nadir (OR: 1.048; CI: 1.024–1.075; p < 0.001) were independently associated with ICU survival after multivariable adjustment (Table 4). Factors associated with long-term survival are depicted in Table 5. Absence of cholestasis (OR: 0.418; CI: 0.187–0.913; p = 0.031), shorter duration of norepinephrine use (OR: 0.936; CI: 0.893–0.977; p = 0.004), longer ICU LOS (OR: 1.053; CI: 1.030–1.079; p < 0.001), lower peak PCT (OR: 0.711; CI: 0.537–0.928, p = 0.014) and higher PaO2/FiO2 ratio nadir (OR: 1.030; CI: 1.012–1.051; p = 0.002) were independently associated with 6-month survival according to multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 5).

Table 4.

Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses of prognostic factors associated with ICU survival.

| Parameter | Simple | Multiple | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Cholestasis | 0.515 (0.294–0.891) | 0.019 | ||

| ECMO | 0.650 (0.370–1.127) | 0.128 | ||

| ICU LOS | 1.008 (0.999–1.018) | 0.096 | 1.061 (1.037–1.089) | < 0.001 |

| Cumulative Days Norepinephrine | 0.983 (0.967-1.000) | 0.048 | 0.932 (0.886–0.976) | 0.004 |

| Cumulative Days of ketamine | 0.974 (0.949–0.998) | 0.039 | ||

| Cumulative Days of NMB | 0.949 (0.894–1.005) | 0.073 | 1.073 (0.984–1.17) | 0.108 |

| Cumulative Days of PN | 0.962 (0.930–0.993) | 0.018 | ||

| Cumulative Days of IMV | 1.004 (0.994–1.014) | 0.464 | ||

| Peak AST* | 0.521 (0.375–0.698) | < 0.001 | 0.619 (0.396–0.937) | 0.028 |

| Peak CRP | 0.971 (0.945–0.997) | 0.029 | ||

| Peak IL-6* | 0.625 (0.512–0.753) | 0.028 | 0.659 (0.474–0.901) | 0.010 |

| Peak PCT* | 0.621 (0.505–0.753) | < 0.001 | 0.772 (0.572–1.032) | 0.084 |

| P/F ratio nadir | 1.046 (1.026–1.070) | < 0.001 | 1.048 (1.024–1.075) | < 0.001 |

| Prone position | 0.629 (0.307–1.235) | 0.189 | ||

| SOFA Score | 0.766 (0.673–0.863) | < 0.001 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; NMB, neuromuscular blockade; PN, parenteral nutrition; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCT, procalcitonin; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2 ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score.

*logarithmized.

Table 5.

Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses of prognostic factors associated with 6-month survival.

| Parameter | Simple | Multiple | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Cholestasis | 0.518 (0.300-0.887) | 0.017 | 0.418 (0.187–0.913) | 0.031 |

| ECMO | 0.724 (0.419–1.241) | 0.243 | ||

| ICU LOS | 1.006 (0.997–1.015) | 0.226 | 1.053 (1.030–1.079) | < 0.001 |

| Cumulative Days norepinephrine | 0.983 (0.967–0.999) | 0.045 | 0.936 (0.893–0.977) | 0.004 |

| Cumulative Days of ketamine | 0.977 (0.953–1.002) | 0.071 | ||

| Cumulative Days of NMB | 0.965 (0.910–1.021) | 0.213 | 1.075 (0.992–1.165) | 0.077 |

| Cumulative Days of PN | 0.969 (0.938-1.000) | 0.052 | ||

| Cumulative Days of IMV | 1.004 (0.994–1.014) | 0.437 | ||

| Peak AST* | 0.573 (0.420–0.761) | < 0.001 | ||

| Peak CRP | 0.979 (0.954–1.004) | 0.102 | ||

| Peak IL-6* | 0.677 (0.560–0.809) | < 0.001 | 0.776 (0.581–1.027) | 0.079 |

| Peak PCT* | 0.612 (0.498–0.742) | < 0.001 | 0.711 (0.537–0.928) | 0.014 |

| P/F ratio nadir | 1.033 (1.016–1.052) | < 0.001 | 1.030 (1.012–1.051) | 0.002 |

| Prone position | 0.729 (0.370–1.399) | 0.349 | ||

| SOFA Score | 0.770 (0.677–0.867) | < 0.001 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; NMB, neuromuscular blockade; PN, parenteral nutrition; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCT, procalcitonin; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2 ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score.

*logarithmized.

We also conducted an analysis including peak ALP levels as continuous variable rather than cholestasis as dichotomous variable. The results can be found in Supplementary Table S3 and S4. For both short- and long-term mortality peak ALP remained an independent risk factor.

In order to analyze a single time-point for variables of interest as potential predictors of adverse outcome we only included laboratory parameters at ICU admission in our simple and multiple logistic regressions models. As expected, laboratory values of liver chemistries (i.e. ALP and AST) at ICU admission were not independently associated with ICU and 6-month mortality, as their elevations occurred during the course of the ICU stay. In contrast, high CRP levels at ICU admission (indicating severe COVID-19 disease) represented a negative prognostic marker for short- and long-term survival (Supplementary Table S5 and S6).

Treatment with UDCA

During ICU stay, a total of 107 patients (48%) received UDCA treatment; in the subgroup of patients with cholestasis 87 (73%) received UDCA. The median UDCA dose applied was 15 (10–18) mg/kg body weight (BW). In 49 subjects (56%) UDCA dose was > 15 mg/kg BW, whereas in 19 patients (22%) dose was < 10 mg/kg BW. No effects of UDCA treatment on ICU survival were observed (Table 3). Patients with cholestasis receiving UDCA had higher peak ALP levels compared to those patients with no UDCA therapy (528 U/L vs. 398 U/L; p = 0.013). However, ALP levels did not differ at ICU discharge (323 U/L vs. 240 U/L; p = 0.080). In addition, we did not find any differences in the reduction of ALP levels when comparing cholestatic patients with and without UDCA treatment (relative reduction: 36.3% vs. 31.0%; p = 0.579).

Discussion

This cohort study of critically ill COVID-19 patients showed that laboratory signs of cholestasis were a frequent complication in patients with COVID-19 ARDS and an important risk factor for survival. Development of cholestasis was found to be associated with disease- and therapy-related factors, especially disease severity, ketamine treatment and ECMO support. Notably, UDCA had no impact on ICU survival in patients with laboratory signs of cholestasis.

Our study showed that more than half of the included patients developed cholestasis, which is substantially higher than previously reported3,11–16,28. This may be interpreted as a consequence of greater severity of illness and more severe hypoxia, specifically in our patient population at a tertiary referral center. Most of the patients had severe COVID-19 associated ARDS requiring IMV and prone positioning; more than half of the patients required ECMO support. In this context, (prolonged) hypoxia in the bile ducts causing endothelial dysfunction and coagulopathy has been mentioned as risk factors for cholestasis3,29. Indeed, infection by SARS-CoV-2 causes endotheliopathy leading to both microvascular and macrovascular thrombotic events causing thrombotic complications and ultimately organ dysfunction/failure30,31. Apart from structural damage (with development of SSC), hypoxia could also interfere with ductal/ductular bile secretion accounting for up to 30% of bile flow in humans32,33, since the role of bile ducts as primary site for functional impairment of bile flow may be underestimated34. In contrast to our data, an observational study from 2021 by Harnisch et al. showed no correlation between hypoxia (as indicated by lowest paO2), ECMO, prone position, and biomarkers of cholestasis in 70 patients with ARDS35. However, both studies are hardly comparable as we only included patients with COVID-19 associated ARDS. In addition, the rate of severe ARDS in the study of Harnisch et al. was only 40% (n = 21) compared to 92% (n = 207) in the present study35. These differences in the severity of ARDS are also represented by a higher rate of prone positioning (79% vs. 50%) and ECMO support (58% vs. 30%) in our patient population and may therefore explain the divergence of results35.

ICU LOS was longer in patients with cholestasis than in those without and was also found to be an independent risk factor associated with the development of cholestasis. Duration of ketamine use (as well as cumulative dose) and IMV are time variables that are inherently highly correlated with length of ICU stay4. Longer ICU LOS was independently associated with ICU survival, potentially because non-survivors died before acquiring extensively long ICU stays. Together, our results indicate that the severity of the COVID-19 predisposes for the later occurrence of cholestasis rather than the long-term intensive care treatment itself. According to the literature this statement seems to hold true not only for COVID-19 associated ARDS but also for other diseases requiring intensive care treatment20,36–38. Even though the COVID-19 pandemic now seems to have come to an end, many of the findings from this study might also be valid for ARDS of other origins37,38. In addition to other viral infections like influenza A (H1N1)-associated ARDS, critical illness associated cholestasis is mainly observed in patients suffering from sepsis, polytrauma, burns and other life-threatening conditions20,36–38. Similar to COVID-19 ARDS, these diseases are also associated with high severity of disease20. Although most data, including the current study, indicate that development of cholestasis is a consequence of severe critical illness, further research is required to evaluate potential differences between cholestasis patterns of various disease entities.

Polypharmacy, including use of ketamine, has been described as risk factor for development of cholestasis during critical illness. Similar to previous studies, ketamine use was independently associated with the development of cholestasis4,23,24. The reason for this is still controversial: on the one hand, ketamine is used as a second line sedative agent in patients with more severe disease indicating greater inflammation and increased ventilation requirements. On the other hand, recent data suggest that precipitation of ketamine itself may be responsible for cast formation, biliary obstruction and thus possible development of SSC in critically ill patients24,25. Indeed, ketamine use itself has been associated with bile duct injury, irrespective of critical illness4,39. However, to date it is not clear to what extent ketamine contributes to the development of SSC in critically ill patients as various other suspected causes for biliary injury coexist (i.e. ischemia, SIRS, other medication).

At the beginning of the pandemic, patients with advanced or decompensated liver disease (i.e. cirrhosis) were not transferred to an ICU due to the limited capacities and in view of the dismal prognosis. Therefore, only few patients (8%) with pre-existing liver disease were included in the current study. Interestingly, this number is comparable to a previous study by Hartl et al. (preexisting liver disease in 13.1% of included patients) investigating the prevalence of cholestasis in a cohort of hospitalized patients with COVID-1928. Further, they observed an ICU admission rate of 43.1% in patients with liver disease, and COVID-19 patients with known liver disease developed progressive cholestasis in 23.1%28. In the present study, a potentially pre-existing (mild) liver disease might not be reported in a large number of patients. In view of the high prevalence of diabetes, arterial hypertension and obesity, the presence of MASLD in a significant proportion of patients in our study population is very likely. In line with the data reported by Hartl et al., these circumstances may have also contributed to the comparatively high rate of patients with cholestasis, as MASLD / the presence of metabolic dysfunction represents a risk factor for cholestatic liver failure or the development of SSC28.

Presence of cholestasis/alterations in ALP levels was independently associated with both ICU and 6-month mortality. These results are well in line with the data of other large studies, who also identified altered ALP levels as independent risk factor for hospital mortality in their COVID-19 patient populations40–42. Interestingly, the prognostic significance of peak AST levels in short- and long-term survival was outperformed by peak ALP levels in our patient cohort contrasting already published data40–42. However, there are many differences between the present and the cited studies limiting the comparability: First, while we observed elevations in aminotransferases in our patient population indicating hepatocellular damage, these alterations were generally mild. In contrast, alterations in cholestasis parameters were more pronounced, which might explain the prognostic relevance of peak ALP levels compared to peak AST levels. Second, in all three mentioned studies the frequency of patients requiring mechanical ventilation and/or intensive care treatment was rather low (16.3-28.7%) indicating less severely ill patient cohorts40–42. In our study, we only included ICU patients, 93% of these required invasive mechanical ventilation, 79% prone positioning and 58% ECMO support. In addition, the rate of abnormal ALP levels in the mentioned studies was considerably lower (4.8-16.1%) compared to our study (53%)40–42. These differences are of high interest and highlight the relevance of our data, as this might indicate that particularly in critically ill patients with COVID-19, parameters of cholestasis such as ALP are of particular prognostic interest. Importantly, cholestasis (with or without jaundice) is a well-established negative prognostic factor in critically ill patients with sepsis/SIRS, major trauma, burns and cardiogenic shock43. The actual causality whether cholestasis may be primarily a biochemical expression of the severity of the disease or secondary to iatrogenic causes may be difficult to determine, since most of our patients required extensive critical care including ECMO therapy for serval days. Indeed, ECMO support, duration of IMV and SOFA score – all factors indicating disease severity – were independently associated with the occurrence of cholestasis.

The majority of our patients with cholestasis received UDCA, which has anticholestatic, cytoprotective and immunomodulatory effects44,45. Although UDCA is considered a first-line drug with proven survival benefits in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), its use in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), SSC and other cholestatic liver diseases remains controversial44,45. Data on UDCA treatment in critically ill patients with and without signs of cholestasis is scarce. A more recent study in patients with septic shock reported no positive effects of UDCA treatment on laboratory values, disease severity and survival46. In our study population, we were also unable to identify any benefit from UDCA with regard to cholestasis or survival. A substantial proportion of patients (22%) in our cohort received very low doses (< 10 mg/kg BW) of UDCA, probably limiting its therapeutic impact. In PBC, a dose of 13–15 mg/kg BW is recommended, and in PSC the dose is somewhat higher (up to 20 mg/kg BW) according to the literature47,48. Despite an increasing frequency of ICU-associated cholangiopathies and SSC, a recommended dose of UDCA for these disease entities is still not defined. The question, if UDCA treatment at which dose could be beneficial, especially for long term survival, should be readdressed in future prospective and controlled studies.

This is a study investigating the prevalence and clinical significance of cholestasis in a large and well-characterized cohort of critically ill patients with COVID-19 ARDS. Further strengths of our work lie in the completeness of the included patients’ datasets and availability of long-term survival data. Due to the retrospective design, a limitation of our study relates to missing information regarding further characterization of cholangiopathies as potential long-term sequela. Furthermore, compared to other studies examining altered liver chemistries in COVID-19 patients, we here present a relatively small patient population. However, in contrast to these studies, we only included severely ill COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care treatment at ICU wards of a large tertiary hospital. The severity of illness is thereby also represented by the high frequency of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, prone positioning and ECMO support. Data on COVID-19 related cholestasis is scarce and often limited to case series or smaller patient cohorts11–14. In this regard we report one of the largest single-center cohorts of critically ill COVID-19 patients analyzing the presence of and risk factors for cholestasis. However, this selection might also introduce bias and therefore restrict the generalizability of the results.

In our study, presence of cholestasis was primarily defined by changes in ALP. Thereby, a large spectrum of clinically relevant cholestatic disease was detected. On the one hand, cholestasis may only be a laboratory sign of dysfunctional biliary excretion, on the other hand, it may already be an indicator of severe and (potentially) irreversible damage to the bile ducts in the sense of SSC. Diagnostic imaging including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and histologic examinations were not performed. These investigations are difficult to perform in ICU patients, and more importantly, ERCP represents a high-risk procedure. In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic the Vienna General Hospital had stringent criteria for transportation of isolated patients in order to minimize the virus transmission rate within the hospital. Liver sonography was conducted on site as bedside procedure on a regular basis and mechanical cholestasis was not documented in any patient. Therefore, advanced diagnostic imaging would not have had any clinical meaningful consequence.

Moreover, the definition of cholestasis used in this study was solely based on changes in ALP. To date there is no universally accepted definition for cholestasis or biliary injury in critically ill patients. We used a cut-off of 1.67 x ULN of ALP levels during ICU stay, which is well established in other cholestatic liver diseases (e.g. PBC), but remains a somewhat arbitrary cut-off27,49. In contrast, other studies investigating the development of cholestasis in COVID-19 patients requiring ICU admission used higher cut-off values (i.e. >3 x ULN or > 5 x ULN) for ALP levels or a combination of deranged liver chemistries including ALP, bilirubin and γGT (> 3 x ULN) making valid comparisons difficult11,12,19,28,36. Importantly, even this relatively low cutoff for cholestasis seems clinically relevant as it proved to be an independent predictor for mortality in this cohort of patients.

In summary, the occurrence of cholestasis is a common complication in patients with SARS-CoV2-induced ARDS and is associated with disease severity. In addition, it also appears to have an independent impact on overall survival, which highlights the importance for intensive care physicians to pay particular attention to this complication. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm effects of specific risk factors for the development of cholestasis and especially to evaluate the benefits of UDCA treatment. Furthermore, our data suggest that the use of ketamine in the context of ARDS should be evaluated carefully.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all involved ICU teams for providing the data on the patients they treated.The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Katharina Krenn, whose contributions to this manuscript were invaluable. Although she is no longer with us, her influence continues to resonate in this work.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BW

Body weight

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- γGT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IMV

Invasive mechanical ventilation

- LOS

Length of stay

- MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction associated liver disease

- NIV

Non-invasive ventilation

- NMB

Neuromuscular blockade

- PBC

Primary biliary cholangitis

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- PSC

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- SAPSII

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SARS-CoV2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SD

Standard deviation

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score

- SSC

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis

- UDCA

Ursodeoxycholic acid

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

- vv

Venovenous

Author contributions

Concept of the study (M.S-G., K.K., E.H., M.T., A.F.S.), data collection (M.S-G., K.K., M.P., P.H., L.H., F.K., L.A., N.B., T.S., C.Z.), statistical analysis (C.K., G.S., M.S-G., A.F.S.), drafting of the manuscript (M.S-G., K.K., A.F.S.) and revision for important intellectual content as well as approval of the final manuscript (all authors).

Funding

No specific financial support was received for this study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing interests outside the submitted work

M.T. received speaker fees from BMS, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Intercept, Ipsen, Jannsen, Madrigal, MSD and Roche; he advised for Abbvie, Agomab, Albireo, BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chemomab, Cymabay, Falk Pharma GmbH, Genfit, Gilead, Hightide, Intercept, Janssen, LoopLab, Mirum, MSD, Novartis, Phenex, Pliant, Rectify, Regulus, Siemens and Shire. He further received travel support from Abbvie, Falk, Gilead, Intercept and Jannsen and research grants from Albireo, Alnylam, Cymabay, Falk, Genentech, Gilead, Intercept, MSD, Takeda and UltraGenyx. He is also co-inventor of patents on the medical use of norUDCA filed by the Medical Universities of Graz and Vienna. K.K. received research grants from Apeptico, Biotest, Bayer and Alterras and travel support from Biotest.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 1872/2021). Given the retrospective design of the study, informed consent statements are not required.

Footnotes

Michael Trauner and Albert Friedrich Stättermayer share senior authorship and correspondence.

Katharina Krenn: Deceased.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mathias Schneeweiss-Gleixner and Katharina Krenn contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Michael Trauner, Email: michael.trauner@meduniwien.ac.at.

Albert Friedrich Stättermayer, Email: albertfriedrich.staettermayer@meduniwien.ac.at.

References

- 1.Xu, Z. et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med.8, 420–422 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta, P. et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet395, 1033–1034 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nardo, A. D. et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms of liver injury in COVID-19. Liver Int.41, 20–32 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henrie, J. et al. Profile of liver cholestatic biomarkers following prolonged ketamine administration in patients with COVID-19. BMC Anesthesiol.23, 44 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marjot, T. et al. COVID-19 and liver disease: Mechanistic and clinical perspectives. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.18, 348–364 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulkarni, A. V. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Liver manifestations and outcomes in COVID-19. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.52, 584–599 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav, D. K. et al. Involvement of liver in COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut70, 807–809 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar-M, P. et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the liver: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Int.14, 711–722 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paliogiannis, P. & Zinellu, A. Bilirubin levels in patients with mild and severe Covid-19: A pooled analysis. Liver Int.40, 1787–1788 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernal-Monterde, V. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a dual response in liver function tests: Association with mortality during hospitalization. Biomedicines8, 328 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonhardt, S. et al. Hepatobiliary long-term consequences of COVID-19: Dramatically increased rate of secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Hepatol. Int.17, 1610–1625 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunyady, P. et al. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A multicenter retrospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis.76, e179–e187 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards, K., Allison, M. & Ghuman, S. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients: A rare disease precipitated by severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMJ Case Rep.13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Roth, N. C. et al. Post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy: A novel entity. Am. J. Gastroenterol.116, 1077–1082 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durazo, F. A. et al. Post-covid-19 Cholangiopathy-A new indication for liver transplantation: A case report. Transpl. Proc.53, 1132–1137 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butikofer, S. et al. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis as cause of persistent jaundice in patients with severe COVID-19. Liver Int.41, 2404–2417 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geier, A., Fickert, P. & Trauner, M. Mechanisms of disease: Mechanisms and clinical implications of cholestasis in sepsis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.3, 574–585 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horvatits, T., Drolz, A., Trauner, M. & Fuhrmann, V. Liver injury and failure in critical illness. Hepatology. 70, 2204–2215 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonhardt, S. et al. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients: Clinical presentation, cholangiographic features, natural history, and outcome a series of 16 cases. Medicine94, e2188 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonhardt, S. et al. Trigger mechanisms of secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients. Crit. Care19, 131 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beath, S. V. & Kelly, D. A. Total parenteral nutrition-induced cholestasis: Prevention and management. Clin. Liver Dis.20, 159–176 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madnawat, H. et al. Mechanisms of parenteral nutrition-associated liver and gut injury. Nutr. Clin. Pract.35, 63–71 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wendel-Garcia, P. D. et al. Long-term ketamine infusion-induced cholestatic liver injury in COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care26, 148 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Tymowski, C., Dépret, F., Dudoignon, E., Legrand, M. & Mallet, V. Ketamine-induced cholangiopathy in ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med.47, 1173–1174 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonhardt, S., Baumann, S., Jürgensen, C., Hüter, L. & Leonhardt, J. Role of intravenous ketamine in the pathogenesis of secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients: Perpetrator or innocent bystander? Answers provided by forensic toxicology. Intensive Care Med.49, 1549–1551 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranieri, V. M. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome the berlin definition. JAMA307, 2526–2533 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumagi, T. et al. Baseline ductopenia and treatment response predict long-term histological progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol.105, 2186–2194 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartl, L. et al. Progressive cholestasis and associated sclerosing cholangitis are frequent complications of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology76, 1563–1575 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Y. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the liver directly contributes to hepatic impairment in patients with COVID-19. J. Hepatol.73, 807–816 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iba, T., Connors, J. M. & Levy, J. H. The coagulopathy, endotheliopathy, and vasculitis of COVID-19. Inflamm. Res.69, 1181–1189 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lax, S. F. et al. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 with fatal outcome: Results from a prospective, single-center, clinicopathologic case series. Ann. Intern. Med.173, 350–361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trauner, M., Meier, P. J. & Boyer, J. L. Molecular pathogenesis of cholestasis. N. Engl. J. Med.339, 1217–1227 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trauner, M. & Boyer, J. L. Bile salt transporters: Molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev.83, 633–671 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vartak, N. et al. On the mechanisms of biliary flux. Hepatology74, 3497–3512 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harnisch, L. O. et al. Biomarkers of cholestasis and liver injury in the early phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome and their pathophysiological value. Diagnostics11, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.de Tymowski, C. et al. Contributing factors and outcomes of burn-associated cholestasis. J. Hepatol.71, 563–572 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruemmele, P., Hofstaedter, F. & Gelbmann, C. M. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.6, 287–295 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weig, T. et al. Abdominal obesity and prolonged prone positioning increase risk of developing sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients with influenza A-associated ARDS. Eur. J. Med. Res.17, 30 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong, G. L. et al. Liver injury is common among chronic abusers of ketamine. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.12, 1759–1762e1751 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding, Z. Y. et al. Association of liver abnormalities with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19. J. Hepatol.74, 1295–1302 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartl, L. et al. Age-adjusted mortality and predictive value of liver chemistries in a viennese cohort of COVID-19 patients. Liver Int.42, 1297–1307 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krishnan, A. et al. Abnormal liver chemistries as a predictor of COVID-19 severity and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. World J. Gastroenterol.28, 570–587 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer, L., Jordan, B., Druml, W., Bauer, P. & Metnitz, P. G. Incidence and prognosis of early hepatic dysfunction in critically ill patients—A prospective multicenter study. Crit. Care Med.35, 1099–1104 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trauner, M. & Graziadei, I. W. Review article: Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of ursodeoxycholic acid in chronic liver diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.13, 979–996 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beuers, U., Trauner, M., Jansen, P. & Poupon, R. New paradigms in the treatment of hepatic cholestasis: From UDCA to FXR, PXR and beyond. J. Hepatol.62, S25–37 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al Sulaiman, K. et al. Impact of ursodeoxycholic acid in critically ill patients with sepsis: A retrospective study. J. Pharm. Pract.36, 566–571 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines. The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J. Hepatol.67, 145–172 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.EASL Clinical Practice. Guidelines on sclerosing cholangitis. J. Hepatol.77, 761–806 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murillo Perez, C. F. et al. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: Treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am. J. Gastroenterol.115, 1066–1074 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.