Abstract

Damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) is a popular Rosa species cultivated for the industrial production of rose oil worldwide. In the current study, the morphological characteristics and genetic diversity among 12 populations of these species collected from Kelaat M’gouna in Morocco were examined to identify more variable traits and compare their genetic structure. Observations were recorded for a total of 24 morphological traits. The phenotypic variation coefficient (CV) of the studied traits varied from 4.79 % to 42.52 %, confirming the high phenotypic variation between accessions. Cluster analysis grouped accessions into two major clusters based on their morphological resemblance. For molecular investigations, nuclear DNA was amplified using 13 ISSR markers. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) indicated that the highest proportion was within populations (87 %) rather than between them (13 %). Boutaghrar region recorded high values of genetic diversity (He = 0.237), percentage polymorphic loci (PPL = 67 %) and Shannon information index (I = 0.358) Clustering based on Jaccard similarity divided studied the accessions into three distinct clusters. STRUCTURE analysis and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) were consistent with the genetic relationships derived from cluster analysis. Our study suggests that the wide genetic variation and haplotype observed in Moroccan Damascene roses are valuable for future improvement and conservation of rose programs, particularly for enhancing commercial traits, flower yield, and breeding stability.

Keywords: Rosa damascena, Phenotypic diversity, Genetic diversity, ISSR markers, Population structure

1. Introduction

The genus Rosa has a wide distribution in the Northern Hemisphere, comprising 200 species and more than 18,000 cultivars.1, 2 Rosa damascena is one of the most important Rosa species, and some of its varieties have great importance in the production of essential oil. In addition to its importance as an essential material for the aromatic and cosmetics industries, it is widely cultivated as a garden rose.3 This plant has been widely used in traditional medicine and has been scientifically proven to possess antioxidant, radical-scavenging, and antimicrobial properties.4 Rose plants are propagated using seeds and methods of vegetative propagation, such as stem cuttings, grafting, budding, cutting grafting (stenting), cutting-budding, root grafting, and tissue culture.5

The Damask rose has a tetraploid genome (8n = 56) with a probable triparental origin. Being a heterozygous and polyploid species, preference is given to asexual reproduction, which ensures the stability of the desired characteristics, that is, the high productivity and quality of rose oil.6

Currently, this species is cultivated extensively in Turkey, Iran, Bulgaria, India, Morocco, South Italy, China, and South France.7 In Morocco, Rosa damascena is a symbolic plant of Kalaat M'Gouna. According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Maritime Fisheries of Morocco,8 the cultivation of Damask rose extends over 3250 km in the form of hedges and fences along the cultivated lands of two valleys, the Dadès Valley and the Rose Valley, giving an average annual 3900 tons production of fresh rose. To our knowledge, no documentary evidence has been found to date, indicating the beginning of Rosa damascena cultivation in the Dadès Valley at Kelaat M'gouna in Morocco. However, the local tradition states that the cultivation of Rosa damascena was established by Muslim pilgrims to produce rose water and dried rose buds (Personal communication 2022). In the 1940s, French colonial perfumers built on tradition and distilleries at Kalaat M’Gouna in Dadès Valley to produce essence and oil rose.9

Many researchers have classified rose varieties according to their phenotypic traits, such as flower weight, peduncle length, flower diameter, number of stamens, number of petals, prickle shape, and number of leaflets. Although the Rosa genus has a wide morphological deviation that is influenced by environmental circumstances, classification based on morphological data alone is insufficient.10, 11, 12

Characterization, assessment, and diversity analysis play a major role in breeding programs and the future improvement of roses. DNA-based marker systems are more efficient and informative for understanding the genetic relationships among accessions. Diverse markers have been developed and used to assess genetic diversity in Rosa, such as sequence-tagged microsatellite site (STMS),13 amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP),14 restriction fragment length polymorphism(RFLP), randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), conserved DNA-derived polymorphism (CDDP),15 simple sequence repeats (SSR)16 and inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR).17 The ISSR marker technique has been successfully used for the genetic characterization of many plant species.18, 19 Among molecular markers, microsatellite or simple sequence repeats and ISSR as rapid techniques are useful in several areas of plant genetic studies. ISSR PCR produces variable patterns of loci that are reproducible, abundant, and polymorphic.20 However, no studies have been conducted on the genetic diversity and conservation of Rosa damascena in Morocco. This study aimed to evaluate Moroccan Rosa damascena accessions from Kelaat M'Gouna, including their morphological diversity based on specific phenotypic traits and their genetic diversity using molecular markers of different inputs for use in breeding and conservation programs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling

A set of 36 accessions of Rosa damascena was collected from 12 sites in the Kelaat M'gouna region in Morocco during the flowering period of April to May 2021. The small town of Kelaat M’ gouna is located between Roses Valley and Dades Valley, which is irrigated by the Asif M'goun River (Fig. 1). It is a region with a pre-Saharan bioclimate and relatively low temperatures that are suitable for increasing growth. At each site, two to four samples were collected at random, and all sampled individuals were separated by at least 20 m. Young leaves with good growth and disease-free growth were collected and stored at −20 °C for later use. The coordinates and altitude which were determined by GPS, the geographic location, and ecological factors were recorded for each research site in Table 1.

Fig 1.

Kelaat M’gouna Map with Rosa damascena collected sites.

Table 1.

Rosa damascena accession informations.

| site | number | Accessions | latitude | longitude | altitude (m.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ait Sedrate Sahl El Gharbia | 1 | SG1 | 31.19209694 | −6.21108587 | 1411.22 |

| 2 | SG2 | 31.19191671 | −6.21059541 | 1419.13 | |

| Hdida | 3 | H1 | 31.34161027 | −6.17076937 | 1590.77 |

| 4 | H2 | 31.34208588 | −6.17102211 | 1579.39 | |

| 5 | H3 | 31.34188776 | −6.17135297 | 1578.93 | |

| Boutagharar | 6 | BT1 | 31.39284592 | −6.13324834 | 1633.87 |

| 7 | BT2 | 31.39258043 | −6.13324834 | 1646.85 | |

| 8 | BT3 | 31.39193460 | −6.13323480 | 1624.37 | |

| Timssiggit | 9 | TM1 | 31.37163383 | −6.16770760 | 1600.62 |

| 10 | TM2 | 31.37139222 | −6.16783027 | 1604.91 | |

| 11 | TM3 | 31.37117834 | −6.16798835 | 1598.97 | |

| Tigharmatine | 12 | TG1 | 31.31471674 | −6.17122014 | 1551.76 |

| 13 | TG2 | 31.31471674 | −6.17122014 | 1551.76 | |

| 14 | TG3 | 31.31471674 | −6.17122014 | 1551.76 | |

| Imlil | 15 | IM1 | 31.17158610 | −6.26384604 | 1404.91 |

| 16 | IM2 | 31.17150138| | −6.26411220 | 1405.36 | |

| 17 | IM3 | 31.17218789 | −6.26336382 | 1406.29 | |

| Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia A | 18 | SC1 | 31.23126567 | −6.10557920 | 1463.15 |

| 19 | SC2 | |31.23143716 | −6.10604294 | 1459.19 | |

| 20 | SC3 | 31.23170517 | −6.10637280 | 1471.59 | |

| Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B | 21 | SC4 | 31.23087756| | −6.10509154 | 1462.96 |

| 22 | SC5 | 31.23104920 | −6.10457494 | 1459.34 | |

| 23 | SC6 | 31.23171657 | −6.10425158 | 1470.25 | |

| Souk El-Khémis Dades | 24 | KD1 | 31.30794713 | −6.06739413 | 1588.20 |

| 25 | KD2 | 31.30740848 | −6.06760821 | 1590.00 | |

| 26 | KD3 | 31.30715258 | − 6.06806057 | 1590.40 | |

| 27 | KD4 | 31.30652498 | −6.06890313 | 1593.75 | |

| Kelâat M'Gouna A | 28 | KM1 | 31.25753099 | −6.12616662 | 1496.46 |

| 29 | KM2 | 31.25765323 | −6.12577441 | 1498.71 | |

| 30 | KM3 | 31.25792039 | −6.12583134 | 1488.87 | |

| Kelâat M'Gouna B | 31 | KM4 | 31.25818382 | −6.12907626 | 1484.64 |

| 32 | KM5 | 31.25815801 | −6.12922268 | 1490.44 | |

| 33 | KM6 | 31.25802017 | −6.12945271 | 1490.46 | |

| Tazzakht | 34 | TZ1 | 31.25702333 | −6.07238778 | 1480.22 |

| 35 | TZ2 | 31.25643439 | −6.07157144 | 1476.80 | |

| 36 | TZ3 | 31.25536093 | −6.07042506 | 1475.11 |

2.2. Morphological characters

The data were collected during the blooming period (between March and April). Twenty-four morphological traits were selected in the full-bloom stage for measurement and data analysis. Each parameter was recorded five times, with three replicates for each. The morphological characters examined include flower weight (g), flower diameter (cm), flower length (cm), petals number, petals length (cm), petals width (cm), stamens number, Stylar channel diameter (mm), sepals number, peduncle length (cm), leaflets number, leaflets length (cm), leaflets width, prickles number, floral scent, style shape, sepals position, leaflet shape (Sharp oval/Obovoide/Elongate/Oval), leaflet color (light green/dark green), leaflet dentition, sepals shape, prickles color (purple/brown), prickles shape (curved/ slender/ strongly curved) and the leaflets front side.

Leaf-related traits were measured in triplicate per sample to calculate the average value. Flower weight was measured using an electronic balance with 0.01 of precision. Statistics on the number of leaflets per leaf were obtained based on visual observations, and three leaves were counted for each sample. The number of prickles was measured randomly on 10 cm of the secondary stem of each plant by selecting all prickle shapes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Different prickles shape of Rosa damascena stem.

2.3. DNA extraction and quantification

Genomic DNA was extracted from freeze-dried young leaves using the CTAB (cetyl-rimethyl ammonium bromide) method,21 with slight modifications (2 % CTAB and 0.2 % PVP).22 Ten microliters of genomic DNA were separated on a 1 % agarose gel in 0.5 × TBE buffer at 90 V for 105 min, and the gels were stained with 5 mg/ml ethidium bromide, visualized, and photographed using a Molecular Imager® Gel Doc XR System (BIO-RAD). The DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The DNA was diluted to 10 ng/µL and stored at −20 °C for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

2.4. ISSR primers amplification

Twenty-five ISSR primers (Biolegio) were selected and used for the molecular characterization of 36 Rosa damascena accessions. Thirteen primers with good banding patterns were selected for further analyses. The inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) primers are shown in Table 2. PCR reactions were carried in thermal cycler (AerisTM), within 10 µl total volume containing 1 µl genomic DNA (25 ng/µl), 2.5 µl (5x) taq Reaction Buffer, comprises of 5 mM dNTPs, 15 mM MgCl2 (meridian BIOSCIENCES), 1 µl of each primer (10 pmol), 0.1 µl of Taq DNA polymerase (5U/µL) (meridian BIOSCIENCES) and 5.4 µl bidistilled water. The PCR amplification conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, primer annealing temperatures for 30 s (Table 2), 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were separated on a 6 % polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X TBE buffer at 300 Volt, stained with BET, and visualized under UV light using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad). The molecular size of the amplified fragments was estimated using a 50pb DNA ladder (meridian BIOSCIENCES).

Table 2.

ISSR primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequence 5′ → 3′ | Ta (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAC | 48.5 | 17 |

| I3 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAA | 51 | 17 |

| UBC8 34 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGCT | 51.5 | 17 |

| UBC8 11 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAC | 49 | 17 |

| UBC 825 | ACACACACACACACACT | 52 | 23 |

| UBC8 41 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGACTC | 51.5 | 17 |

| UBC8 42 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGACG | 51.5 | 17 |

| UBC8 80 | GGAGAGGAGAGGAGA | 51 | 17 |

| UBC 808 | AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GC | 51 | 23 |

| UBC8 89 | DBDACACACACACACAC | 49.5 | 23 |

| ISSR 1 | AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GYT | 49.5 | 24 |

| ISSR 2 | GAG AGA GAG AGA GAG AC | 49.5 | 24 |

| ISSR 3 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYT | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 4 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYC | 51 | 24 |

| ISSR 5 | CA CA CA CA CA CA CA CA RC | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 6 | CACACACACACACACARG | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 7 | CACACACACACACACART | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 8 | CTCTCTCTCTCTCTCTRA | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 9 | ACA CAC ACA CAC ACA CYG | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 12 | AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GYG | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR13 | GTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTYA | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 14 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGT | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 15 | AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GC | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 20 | GTG TGT GTG TGT GTG TC | 49 | 24 |

| ISSR 32 | CCCGTGTGTGTGTGTGT | 50.8 | 24 |

2.5. Data analysis

Data for morphological traits, coefficient of variation (CV), and standard deviation (SD) of each trait were calculated using the SAS software (SAS for Windows. version 16). Pearson correlation coefficients among phenotypic traits were determined using SAS software version 16. Principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis based on the Euclidean distance coefficient were performed using the GenStat 18th Statistical Version.25

Polymorphic markers were scored as present (1) or absent (0) of amplicons, and the molecular weight of bands was estimated using a 50 bp DNA step ladder as a size standard to generate a binary matrix for all bands in gels. Indices to verify the efficiency of the ISSR primers were calculated using the online program iMEC.26 Cluster-based Jaccard similarity data were constructed using GenStat version ver.18.25 Molecular variation analysis (AMOVA) and PCoA were conducted using GenAlEx 6.501.27

The program used the Bayesian iterative algorithm to group individuals by comparing likelihoods under the assumptions of admixed ancestry and correlated allelic frequencies using unlinked markers.28 The number of groups (K) in the data was determined by a series of analyses performed with K values ranging from K = 1 through 10, using 100,000 burn-in and 100,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations, with three independent iterations for each K value. The optimal K value was determined by examining the ad hoc statistic DeltaK and L(K) based on the percentage of variation in the log probability of the molecular markers29 using Structure Harvester software.30 Mantel test among similarity matrix of morphological and molecular data was performed using the NTSYS pc v2.01.31

3. Results

3.1. Morphological description

Of the 24 traits examined, six traits were similar in all accessions, namely sepal number, floral scent, style shape, sepal shape, leaflet dentition, and sepal position. Other significant characteristics were flower diameter, flower weight, flower length, petals length, petals number, petals width, leaflet number, stylar channel diameter, peduncle length, leaflet number, leaflet length, leaflets width, prickle number, leaflet shape, leaflet color, prickle color, prickle shape, and front-side leaflets.

The coefficient of variation (CV), standard deviation, and mean, minimum, and maximum values of morphological traits are presented in Table 3. The coefficient of phenotypic variation of the studied traits varied from 4.79 % to 42.52 %, confirming the wide morphological diversity between accessions. Indeed, prickle number, peduncle length, and flower weight showed the highest variability (CV = 42.52 %, CV = 38.03 %, and CV = 25.02 %, respectively), while the lowest was observed in altitude (CV = 4.79 %) and stylar channel diameter (CV = 7.16 %). Further, the length and width of petals range are 2.20 cm to 4.10 cm and 2 to 4.30 cm respectively. The optimal petal number (50) and flower weight (3.124 g) were determined in the Boutaghrar population.

Table 3.

Coefficient of variation (CV), mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, and maximum for Rosa damascena quantitative traits.

| Characters | Unit | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | CV % |

F value Among populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower diameter | cm | 4.80 | 8.20 | 6.47 | 0.76 | 11.78 | 4.23** |

| Flower weight | g | 0.78 | 3.12 | 1.95 | 0.49 | 25.02 | 4.18** |

| Flower length | cm | 1.30 | 3.30 | 2.49 | 0.51 | 20.47 | 5.22** |

| Petal number | 25.00 | 50.00 | 34.44 | 6.07 | 17.62 | 2.05* | |

| Petal length | cm | 2.20 | 4.10 | 3.14 | 0.46 | 14.57 | 2.61* |

| Petal width | cm | 2.00 | 4.30 | 3.11 | 0.51 | 16.49 | 1.87 |

| Stamens number | 65.00 | 115.00 | 97.08 | 12.39 | 12.76 | 1.24 | |

| Stylar channel diameter | mm | 1.50 | 2.00 | 1.96 | 0.14 | 7.16 | 2.41* |

| Peduncle length | cm | 1.20 | 5.40 | 2.56 | 0.97 | 38.03 | 2.50* |

| Leaflets number | 5.00 | 9.00 | 6.89 | 0.67 | 9.68 | 1.00* | |

| Leaflets length | cm | 3.15 | 5.65 | 4.09 | 0.67 | 16.44 | 1.78 |

| Leaflets width | cm | 2.30 | 4.25 | 3.17 | 0.50 | 15.75 | 2.02 |

| Prickles number | 79.00 | 325.00 | 170.81 | 72.62 | 42.52 | 5.45** | |

| Altitude | 1405.00 | 1647.00 | 1519.00 | 72.76 | 4.79 | 761.41** |

Significant at 5%,

Significant at 1%.

Three leaflet forms (Obovoid, Elongate, and Oval) were found in all populations, with a high frequency of oval shapes (52.78 %). A significant difference was observed in leaflet color, with a high frequency of dark green color (66.67 %). In our study, the frequencies of glands and hair on the underside of leaflets and prickle-shaped slender, and slightly curved were 69.44 % and 80.56 %, respectively.

3.2. Inter-trait correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis (Table 4) between different quantitative characters revealed that traits related to the same organs were highly correlated, such as flower diameter with petal width (r = 0.73; p = 0.0001) and petal length (r = 0.71; p = 0.0001). Peduncle length was positively correlated with leaflet length, width, and prickle number. However, prickle number and peduncle length were negatively correlated with flower weight traits, with −0.41 and −0.43 respectively. Correlation analysis between Rosa damascena phenotypic traits and geographical factors showed that the majority of traits were significantly different and not influenced by altitude.

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlation between various quantitative morphological traits of Rosa damascena accessions from the last M'Gouna region.

| Characters | Flower diameter | Flower weight | Flower length | Petals number | Petal length | Petal width | Stamens number | Stylar channel diameter | Peduncle length | Leaflets number | Leaflets length | Leaflets width | Prickles number | Altitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower diameter | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Flower weight | 0.38* | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Flower length | 0.36* | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Petals number | −0.17 | 0.04 | 0.17844 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Petal length | 0.71** | 0.35* | 0.13364 | −0.21 | 1 | |||||||||

| Petal width | 0.73** | 0.43** | 0.25283 | −0.14 | 0.61** | 1 | ||||||||

| Stamens number | −0.22 | −0.14 | −0.02657 | −0.08 | −0.19299 | −0.20 | 1 | |||||||

| Stylar channel diameter | −0.27 | −0.12 | 0.17484 | 0.48** | −0.30* | −0.29 | 0.42** | 1 | ||||||

| Peduncle length | −0.14 | −0.43** | −0.43** | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.20 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 1 | |||||

| Leaflets number | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.34* | 1 | ||||

| Leaflets length | 0.0621 | −0.19 | −0.18 | −0. 16 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.48** | −0.14 | 1 | |||

| Leaflets width | 0.00221 | −0.23 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.19 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.54** | −0.22 | 0.87** | 1 | ||

| Prickles number | −0.44** | −0.41** | −0.17 | 0.25 | −0.42** | −0.40** | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.47** | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.33* | 1 | |

| Altitude | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.13 | −0.15 | −0.25 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.24 | 0.27 | 0.27 | −0.08 | 1 |

Significant at 5%,

Significant at 1%.

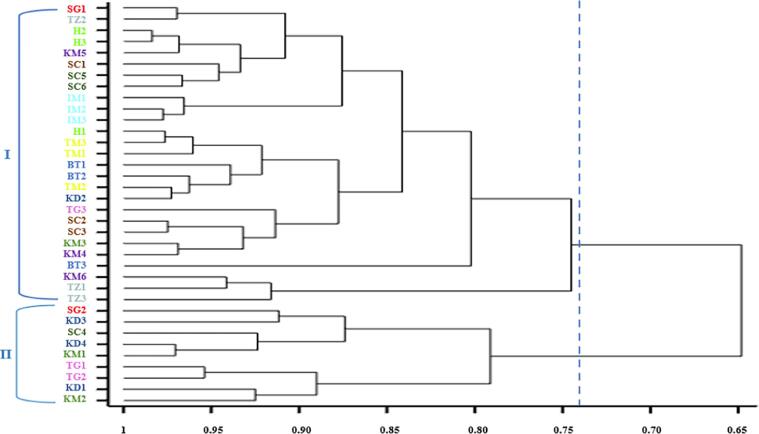

3.3. Hierarchical cluster analysis based on phenotypic traits

The dendrogram was constructed based on the Euclidean distance among the accessions (Fig. 3). Cluster analysis based on 24 quantitative characters revealed different hierarchical levels and grouped them into two main clusters at a 74 % similarity distance. The first cluster, Cluster I, contained 27 accessions that formed three sub-clusters. Cluster II has two sub-clusters and contains 9 accessions.

Fig. 3.

Multivariate clustering based on morphological traits of Rosa damascena accessions.

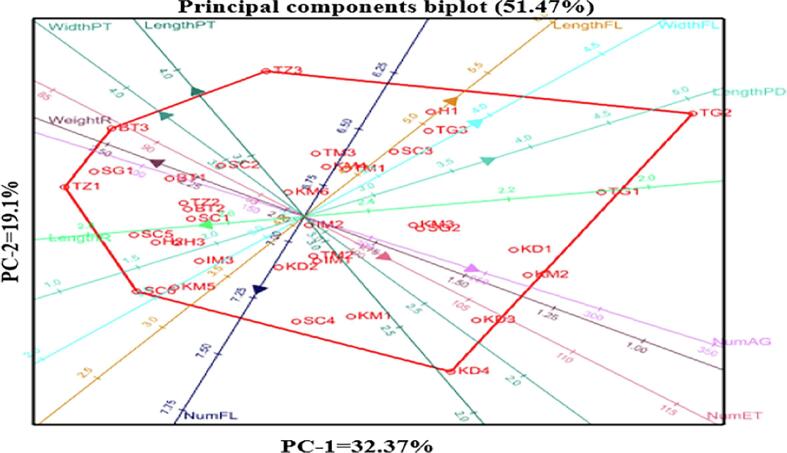

3.4. PCA of quantitative traits

Principal component analysis results showed wide variation among the 36 accessions according to morphological characteristics (Fig. 4). PC1 had a high variance (32.37 %) and major characteristics such as leaflet length, peduncle length, petal length, prickle number, flower weight, leaflet width, and petal width. PC2 contributed 19.10 % of the total variability with leaflet length, petal length, leaflet width, and petal width. Together, the two components accounted for 51.47 % of the variation. Thus, these morphological traits were appropriate for evaluating the phenotypic diversity of R. damascena.

Fig. 4.

Bi-plot of 36 Rosa damascena accessions based on morphological traits.

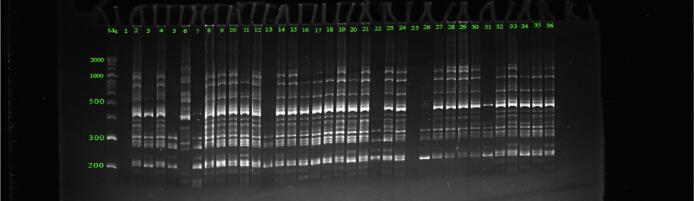

3.5. Molecular analysis using inter-simple sequence repeats

Thirteen primers used in this study revealed polymorphic amplification profiles and produced 377 clear bands. The number of bands produced per primer ranged from 27 to 47, with an average of 36.6. I3 exhibits the maximum number of bands (47). The PIC value ranged from 0.35 with UBC842 0.41 and UBC843. UBC842 had the highest marker index value (MI = 7.57), whereas the lowest value (3.31) was associated with I1. Regarding the resolving power (Rp), the highest value was 20.11 for ISSR12, and the lowest value (8.11) was assigned to ISSR15 (Table 5). The ISSR profile of UBC841 is shown in Fig. 5.

Table 5.

The genetic diversity parameters details of ISSR primers including number of polymorphic bands (NPB), percentage of polymorphic bands (PPB), total amplified bands (TAB), resolving power (Rp), marker index (MI), polymorphism information content (PIC), expected heterozygosity (He) and annealing temperature (Ta).

| Primers | He | PIC | MI | Rp | TAB | NPB | PPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I 1 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 3.31 | 12.89 | 27 | 27 | 100 % |

| I 3 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 4.45 | 17.11 | 47 | 47 | 100 % |

| UBC8 34 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 6.65 | 17.83 | 36 | 35 | 97.22 % |

| UBC8 11 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 4.23 | 18.06 | 41 | 41 | 100 % |

| UBC8 41 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 7.22 | 17.06 | 37 | 37 | 100 % |

| UBC8 42 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 7.57 | 10.67 | 43 | 43 | 100 % |

| UBC8 80 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 4.60 | 14.72 | 28 | 27 | 96.42 % |

| UBC8 89 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 6.13 | 18.78 | 43 | 43 | 100 % |

| ISSR 3 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 4.90 | 15.89 | 29 | 29 | 100 % |

| ISSR 4 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 4.62 | 8.22 | 30 | 30 | 100 % |

| ISSR 32 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 6.28 | 14.50 | 39 | 36 | 92.30 % |

| ISSR 12 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 4.77 | 20.11 | 45 | 45 | 100 % |

| ISSR 15 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 3.41 | 8.11 | 32 | 32 | 100 % |

| Mean | 0.39 | 0.37 | 5.24 | 14.92 | 36.69 | 36.69 | 98.91 % |

B: A, G, or T; D: C, G, or T.

Fig. 5.

The polyacrylamide gel picture represents the amplification profile of primer UBC841 (Mq: 50 bp DNA ladder).

3.6. Molecular variance analysis and PCoA

AMOVA showed a highly significant difference between the studied samples (PhiPT = 0.127, p = 0.001), with a higher variation within populations (87 %), compared to 13 % between populations (Table 6). The genetic diversity index (Na, Ne, I, He, PPL, and PB) was provided for all populations and varied greatly among them (Table 7). The highest level of variability (He = 0.24) was observed in the Boutaghrar population, whereas the Ait Sedrate Sahl El Gharbia population showed the lowest level (He = 0.063). Boutaghrar, Ait Sedrate Sahl Charquia B, and Souk El-Khémis Dade populations had high Shannon information index values (I = 0.36, 0.30, and 30, respectively). A high level of polymorphism was observed among the populations. Indeed, Boutaghrar, Souk El-Khémis Dades, Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B, Hdida and Kelâat M'Gouna B populations revealed the higher genetic diversity values 66.67 %, 55.56 %, 50.31 %, 42.56 % and 41.51 % respectively. Furthermore, private alleles number was highest in Boutaghrar population (57 private alleles), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B (9 private alleles), Hdida (8 private alleles), Souk El-Khémis Dades (4 private alleles), Imlil (3 private alleles), Tigharmatine (2 private alleles) and a single private allele existing in Ait Sedrate Sahl El Gharbia, Kelâat M'Gouna A, Kelâat M'Gouna B and Tazzakht, suggesting a wide genetic diversity in studied populations.

Table 6.

Analysis of molecular variances (AMOVA) summary based on ISSR for Rosa damascena accessions.

| Source of variation | Df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | Var % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 11 | 944.83 | 85.89 | 8.73 | 13 % |

| Within Pops | 24 | 1433.92 | 59.75 | 59.75 | 87 % |

| Total | 35 | 2378.75 | 145.64 | 68.48 | 100 % |

Df degree of freedom, SS sum of squares, MS mean of squares, Est. Var estimated variance components, Var total variance.

Table 7.

Genetic variation parameters of different Rosa damascena accessions of population based ISSR primers.

| Population | Na | Ne | I | PPL | He | PB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ait Sedrate Sahl El Gharbia | 0.60 | 1.11 | 0.09 | 15 | 0.063 | 1 |

| Hdida | 0.97 | 1.29 | 0.25 | 43 | 0.167 | 8 |

| Boutaghrar | 1.42 | 1.39 | 0.36 | 67 | 0.237 | 57 |

| Timssiggit | 0.87 | 1.19 | 0.16 | 29 | 0.109 | 0 |

| Tigharmatine | 0.77 | 1.16 | 0.13 | 22 | 0.091 | 2 |

| Imlil | 0.90 | 1.22 | 0.19 | 32 | 0.127 | 3 |

| Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia A | 0.82 | 1.18 | 0.15 | 27 | 0.105 | 0 |

| Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B | 1.15 | 1.36 | 0.30 | 50 | 0.202 | 9 |

| Souk El-Khémis Dades | 1.20 | 1.35 | 0.30 | 56 | 0.204 | 4 |

| Kelâat M'Gouna A | 0.95 | 1.24 | 0.20 | 34 | 0.135 | 1 |

| Kelâat M'Gouna B | 1 | 1.28 | 0.24 | 42 | 0.161 | 1 |

| Tazzakht | 0.73 | 1.17 | 0.14 | 25 | 0.097 | 1 |

| Mean | 0.95 | 1.25 | 0.21 | 37 | 0.142 | 7.25 |

Na, observed number of alleles; Ne, number of effective alleles;I, Shannon’s information index; PPL, percentage of polymorphic loci; He,expected heterozygosity;PB,number of private bands.

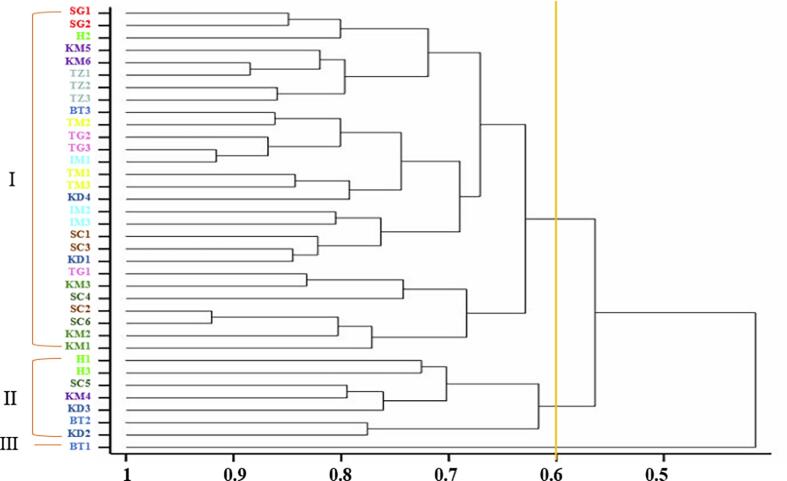

PCoA assisted in analyzing and representing the genetic relationships between Rosa damascena accessions. The PCoA divided the accessions into three groups, PCoA1, PCoA2, and PCoA3, which accounted for 14.44 %, 9.4 %, and 7.46 % of the variation in the Damask rose accessions, respectively (Fig. 6). The cluster analysis results support these observations (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Principal coordinate analysis of 12 Rosa damascena accessions based on ISSR primers.

Fig. 7.

Dendrogram based on Jaccard’s genetic similarities between 36 Damask rose accessions calculated from ISSR data.

3.7. Cluster and population structure

Genetic similarity between 36 accessions of Rosa damascena as determined by Jaccard’s similarity coefficient ranged from 0.42 to 0.92 with a mean of 0.67, indicating wide diversity among accessions. Clustering analysis based on Jaccard genetic similarities grouped all accessions of Damask rose into three major groups at 0.60 a similarity coefficient. Cluster I was the largest, consisting of 28 accessions, one accession from Boutaghrar, one accession from Hdida, three accessions from Kelâat M'Gouna A, two accessions from Kelâat M'Gouna B, three accessions from Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia A, two accessions from Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B, three accessions from Timssiggit, three accessions from Tigharmatine, three accessions from Imlil, two accessions from Souk El-Khémis Dades. Cluster II comprised accessions from Hdida (two accessions), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B (one accession), Kelâat M'Gouna B (one accession), Souk El-Khémis Dades (two accessions), Boutaghrar (one accession). Cluster III included only one accession from Boutaghrar (Fig. 7).

The population structure of the 36 Rosa damascena accessions was further assessed using the STRUCTURE Harvester program (Fig. 8). Based on the highest value of ΔK (K = 3), the population structure was divided into three subpopulations. Out of the 36 accessions, Subpopulation 1 had the largest of the accessions (22) from Ait Sedrate Sahl El Gharbia (2), Hdida (1), Boutaghrar (1), Timssiggit (3), Tigharmatine (3), Imlil (2), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia A (3), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B (1), Souk El-Khémis Dades (1), Kelâat M'Gouna A (3), Kelâat M'Gouna B (2) and Tazzakht (2). while sub-population 2 comprises 7 accessions from Hdida (1), Imlil (1), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B (1), Souk El-Khémis Dades (2), Kelâat M'Gouna B (1) and Tazzakht (1). Five accessions from Hdida (1), Boutaghrar (2), Ait Sedrate Sahl charquia B (1) and Souk El-Khémis Dades (1) were classified into sub-population 3. The results obtained from the dendrogram related to genotype structuring were comparable to those obtained from the PCoA analysis.

Fig. 8.

Structure of 36 Rosa damascena accessions based on all ISSR markers.

The Mantel test showed a low correlation and was not statistically significant (r = 0.116, p = 0.5) between the similarity matrix of the molecular and morphological data.

4. Discussion

Large phenotypic variations were observed among the most studied accessions of Rosa damascena from Kelaat M’gouna in Morocco. As indicated by our results, the morphological traits of the Rosa damascena resources examined all showed different degrees of variation and presented a rich morphological diversity. Khadivi-Khub and Etemadi-Khah (2015)32 indicated that the CV may be an indicator to distinguish between genotypes based on morphology. However, a high CV also reflects that the traits are substantially influenced by the environment. Kaul et all,33 reported similar results in the same species.34 and35 reported that petal number, leaf margin type, stipule shape, leaflet shape, flower shape, Flower weight, Flower diameter, prickles shape, and vestiture of leaflet ventral side are key characteristics of differentiation of Rosa species. Khaleghi and Khadivi.12 observed that the largest variability was for leaf color (CV = 73.48 %), whereas the lowest was for petal weight/flower weight (CV = 8.20 %) and leaflet/leaf number (CV = 6.63 %), which are similar to those of our study. The CV of Rosa platyacantha indicated relatively lower phenotypic variation in Rosa platyacantha populations than in other rosa species.36

A significant positive correlation was revealed between morphological traits related to spininess, leaf length, and flower diameter. Indeed, there was an agreement with Tabaei-Aghdaei et al.,10 who showed a significant correlation between different characteristics related to flowers and prickles. Pal and Mahajan (2017)]37 and Kumar et al. (2023)38 reported a similar observation based on the correlation of floral traits, where flower yield and weight were significantly correlated with the number of flowers and petal number, respectively. Moreover, PCA indicated that leaflet length, leaflet width, and petal width were determinant traits (51.47 %) for morphological diversity studies. Cluster analysis classified the Moroccan Damask rose accessions into two large groups. Accessions from different sites were grouped into the first group, so there was no geographical conservation.

Understanding genetic diversity in rose species is essential for breeders to assess germplasm characteristics and produce superior progeny. The previous study (Gaurav et al., 2018), found that morphological analysis based on descriptors alone was insufficient for characterizing Rosa species. Consequently, morphological analysis of Rosa damascena accessions was strengthened by genetic diversity assessments using molecular markers. This study provides the first detailed analysis of genetic variation and relationships among 36 Rosa damascena accessions from Morocco, which were evaluated using 13 ISSR markers. In the present study, these markers were found to have a high level of polymorphism (98.91 %). Given this polymorphism percentage, ISSR markers can be a strong tool for identifying and differentiating rose genotypes, which is in line with other research on Rosa damascena genotypes using RAPD, ISSR, or SCoT markers. Indeed, a study on the genetic diversity of 29 R. damascena genotypes in India, using SCoT primers, indicated a high level of polymorphism.39 Mostafavi et al. used URP and SCoT markers and Panwar et al.41 used RAPD and ISSR markers reported 100 % and 94 % genetic polymorphism respectively. A high level of polymorphism (99.27 %) was also noted in wild Moroccan rose using ISSR and DAMD markers.17 These high levels of polymorphism may be related to the polyploid structure and heterozygosity of the rose species genome, recombination, mutations, natural hybridization, gene flow, and random segregation of heterozygous chromosomes during meiosis.40, 42, 43 Based on high values of expected heterozygosity (He = 0.39), polymorphic information content (PIC = 0,37), and resolving power (Rp = 14,92), high genetic diversity was observed in R. damascena in the present study. Compared with our results, large values of these indices were noted in R. damascena accessions from Iran.40 Panwar et al. Aparna et al44, 6, and45 also reported high genetic diversity index values based on RAPD, ISSR, SCoT, and SSR markers in India Greece, Turkey, France, and Bulgaria.

According to the AMOVA results, the genetic diversity between all accessions of Rosa damascena was more important within populations (87 %) than between populations (13 %). This is consistent with the results of Mostafavi et al.,40 who studied genetic relationships among 40 Damask rose genotypes from Iran using URP and SCoT markers and reported that genetic variation within populations was more important than the variation between them. High genetic diversity within populations is crucial for the adaptability and overall health of a species. Genetic diversity allows for a wide range of phenotypic traits, which can enhance the ability of individuals to adapt to varying environmental conditions. For instance, studies have shown that genetic diversity is important for ecological performance and resilience through the expression and variance of phenotypic traits.46

In the current study, PCoA was performed to assess the relative distribution of ISSR markers in the genome. Rosa damascena accessions were well dispersed in the biplot, which showed that ISSR primers used in this study had a high distribution throughout the genome. Therefore, ISSR results can be considered more reliable and precise.

Genetic similarity ranged from 0.42 to 0.92, indicating a high genetic variability of Rosa damascena in Kelaat M’gouna. Cluster I and Cluster II showed that there was an overlap between most populations, which may be due to the origin of Rosa damasecna accessions and human transmission of plants or genetic displacement and gene flow by natural hybridization.47, 40 Moreover, the presence of the Boutaghrar accession (BT1) alone in group III could be due to its different genetic origins.

The results of the model-based STRUCTURE analysis were in agreement with those of the cluster and PCoA. Therefore, gene flow was revealed among the 36 accessions of Rosa damascena. Saghir et al.,17 Jiang and Zang,15 and Agarwal et al.39 studied the population structure of roses to understand the genetic relationships among populations.

The Mantel test showed no significant correlation between phenotypic traits and genetic distance among Rosa damascena accessions, indicating that the studied morphological traits were not discriminant of R. damascena. A similar result was previously reported by Yang et al.36 for Rosa platyacantha.

In summary, Ecological and environmental factors such as climate, propagation methods, and gene flow significantly influence the genetic and phenotypic diversity of Rosa damascena. Studies have shown that variations in temperature, humidity, rainfall, and other climatic conditions can lead to differences in physiological and phenotypic traits. Additionally, molecular analyses have revealed the impact of these factors on the genetic diversity and population structure of this species. Understanding these influences is crucial for the conservation and cultivation of Rosa damascena.12

Moroccan Rosa damascena originated in the Middle East and was introduced in Morocco more than 300 years ago. Despite the use of the rosa propagation method, which is mainly performed by cutting, this study revealed high diversity within and among populations. Boutaghrar accessions had higher values of private alleles, heterozygosity values (He), and Shannon’s information index (I). Thus, the Boutaghrar population can be considered as a bank of various genes responsible for important traits. These results are important for the establishment of future Moroccan rose breeding programs.

5. Conclusion

The present study identified high genetic diversity among Rosa damascena accessions collected from the Kelaat M'gouna region and confirmed the usefulness of ISSR molecular markers in the characterization of Rosa damascena. Indeed, the more genetically distant the relationship between parents, the more heterosis was marked. Cluster analysis clarified the genetic relationships among the studied accessions, which have potential uses in breeding programs for the introduction of certain economic traits. Given the high genetic diversity and number of haplotypes found at the Boutaghrar site, it is crucial to preserve these unique genetic resources. Incorporating them into national breeding programs can introduce valuable economic traits and support their inclusion in the national catalog in the future. Conservation efforts should include the establishment of gene banks and in situ conservation strategies to maintain the genetic diversity of this population. High-throughput sequencing of Rosa damascena will help preserve the unique genetic resources of the Boutaghrar site by identifying rare haplotypes and ensuring their conservation. This ensures that valuable traits are not lost and can be used in future breeding program.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nezha Lebkiri: Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis. Younes Abbas: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis. Driss Iraqi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Methodology. Fatima Gaboun: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Data curation. Karim Saghir: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology. Mohamed Fokar: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis. Ismail El hamdi: Resources, Methodology. Khadija Bakhy: Visualization, Validation. Rabha Abdelwahd: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Ghizlane Diria: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources.

Contributor Information

Nezha Lebkiri, Email: LEBKIRI.nezha@inra.ma.

Younes Abbas, Email: a.younes@usms.ma.

Driss Iraqi, Email: driss.iraqi@inra.ma.

Fatima Gaboun, Email: fatima.gaboun@inra.ma.

Mohamed Fokar, Email: m.Fokar@ttu.edu.

Ismail El hamdi, Email: elhamdi_ismail@yahoo.fr.

Khadija Bakhy, Email: khadija.bakhy@inra.ma.

Rabha Abdelwahd, Email: rabha.abdelwahd@inra.ma.

Ghizlane Diria, Email: ghizlane.diria@inra.ma.

References

- 1.Rose G.S. In: Plant Breeding Reviews. Janick J., editor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. Genetics and Breeding; pp. 159–189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehder A. Malus. Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs 1949:389–99.

- 3.Rusanov K., Kovacheva N., Vosman B., et al. Microsatellite analysis of Rosa damascena Mill. accessions reveals genetic similarity between genotypes used for rose oil production and old Damask rose varieties. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111(4):804–809. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-2066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moualek I., Lahcene S., Salem-Bekhit M.M., et al. Assessment of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of aqueous extract of rosa sempervirens leaves. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2023;69(3):214–222. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2023.69.3.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaafi B., Kahrizi D., Zebarjadi A., Azadi P. The effects of nanosilver on bacterial contamination and increase durability cultivars of Rosa hybrida L. through of stenting method. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2022;68(3):179–188. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.3.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziogou F.T., Kotoula A.A., Hatzilazarou S., et al. Genetic assessment, propagation and chemical analysis of flowers of Rosa damascena Mill. Genotypes cultivated in Greece. Horticulturae. 2023;9(8):946. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae9080946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S., Kumar R. Effect of temperature and storage duration of flowers on essential oil content and composition of damask rose (Rosa×damascena Mill.) under western Himalayas. J Appl Res Med Aromatic Plants. 2016;3(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmap.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Agriculture and Maritime Fisheries of Morocco. Kelâa M’gouna Dadès rose and Kelâa M’gouna-Dadès rose water. Published online 2019. Accessed November 10; 2022. https://www.agriculture.gov.ma/fr/filiere/rose-a-parfum.

- 9.Mattock RE. Cultural linkage facilitated the transmigration of the remontant gene in Rosa x damascena, the Damask rose, in circa 3,500 BCE from the river Amu Darya watershed in Central Asia, the river Oxus valley of the Classics, to Rome by 300 BCE. Published online 2017.

- 10.Tabaei-Aghdaei S.R., Babaei A., Khosh-Khui M., et al. Morphological and oil content variations amongst Damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) landraces from different regions of Iran. Scientia Horticulturae. 2007;113(1):44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2007.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh K., Sharma Y.P., Gairola S. Morphological characterization of wild Rosa L. germplasm from the Western Himalaya, India. Euphytica. 2020;216(3):41. doi: 10.1007/s10681-020-2567-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khaleghi A., Khadivi A. Morphological characterization of Damask rose (Rosa × damascena Herrm.) germplasm to select superior accessions. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2020;67(8):1981–1997. doi: 10.1007/s10722-020-00954-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esselink G., Smulders M., Vosman B. Identification of cut rose (Rosa hybrida) and rootstock varieties using robust sequence tagged microsatellite site markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106(2):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basaki T., Mardi M., Kermani M.J., et al. Assessing Rosa persica genetic diversity using amplified fragment length polymorphisms analysis. Sci Hortic. 2009;120(4):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang L., Zang D. Analysis of genetic relationships in Rosa rugosa using conserved DNA-derived polymorphism markers. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32(1):88–94. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2017.1407255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghose K., McCallum J., Fillmore S., et al. Structuration of the genetic and metabolite diversity among Prince Edward Island cultivated wild rose ecotypes. Sci Hortic. 2013;160:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saghir K., Abdelwahd R., Iraqi D., et al. Assessment of genetic diversity among wild rose in Morocco using ISSR and DAMD markers. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2022;20(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s43141-022-00425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaman K., Dalda-Şekerci A., Yetişir H., Gülşen O., Coşkun Ö.F. Molecular, morphological and biochemical characterization of some Turkish bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) genotypes. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;123:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kıraç H., Dalda Şekerci A., Coşkun Ö.F., Gülşen O. Morphological and molecular characterization of garlic (Allium sativum L.) genotypes sampled from Turkey. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2022;69(5):1833–1841. doi: 10.1007/s10722-022-01343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bornet B., Branchard M. Use of ISSR fingerprints to detect microsatellites and genetic diversity in several related Brassica taxa and Arabidopsis thaliana: brief report. Hereditas. 2004;140(3):245–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2004.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle J. In: Molecular Techniques in Taxonomy. Hewitt G.M., Johnston A.W.B., Young J.P.W., editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1991. DNA protocols for plants; pp. 283–293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi S., Jin W., Yuan Y., Fang Y. An optimized CTAB method for genomic DNA extraction from freshly-picked Pinnae of Fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris L. Bio-Protocol. 2018;8(13) doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomar R.S., Gajera H.P., Viradiya R.R., Patel S.V., Golakiya B.A. Characterization of mango genotypes of Gir region based on ISSR markers. Indian J Hortic. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbarzadeh Z, Khosh-khui M, Salehi H, Shahsavar AR, Saberivand A. Assessment of Genetic Relatedness in Roses by ISSR Markers. Published online 2013.

- 25.Goedhart P, Thissen JTNM. Biometris GenStat Procedure Library Manual 21th Edition. Published online 2016.

- 26.Amiryousefi A., Hyvönen J., Poczai P. iMEC: online marker efficiency calculator. Appl Plant Sci. 2018;6(6):e01159. doi: 10.1002/aps3.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peakall R., Smouse P.E. genalex 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006;6(1):288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard J.K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evanno G., Regnaut S., Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure : a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(8):2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earl D.A., vonHoldt B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genet Resour. 2012;4(2):359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohlf F.J. NTSYS-pc: numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. Appl Biostat. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khadivi-Khub A., Etemadi-Khah A. Phenotypic diversity and relationships between morphological traits in selected almond (Prunus amygdalus) germplasm. Agroforest Syst. 2015;89(2):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10457-014-9754-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaul K., Karthigeyan S., Dhyani D., Kaur N., Sharma R.K., Ahuja P.S. Morphological and molecular analyses of Rosa damascena×R. bourboniana interspecific hybrids. Sci Hortic. 2009;122(2):258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2009.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S., Dhyani D., Nag A., Sharma R.K. Morphological and molecular characterization revealed high species level diversity among cultivated, introduced and wild roses (Rosa sp.) of western Himalayan region. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2017;64(3):515–530. doi: 10.1007/s10722-016-0377-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yousefi B., Shahbazi K., Khamisabady H., Safari H., Ghytoury M. Evaluation of genetic diversity in fifteen Rosa damascena Mill. genotypes based on morphologic and yield traits. IJGPB. 2022 doi: 10.30479/ijgpb.2022.16930.1314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S., Guo N., Ge H. Morphological and AFLP-based genetic diversity in Rosa platyacantha population in eastern Tianshan mountains of northwestern China. Hortic Plant J. 2016;2(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.hpj.2016.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pal P.K., Mahajan M. Pruning system and foliar application of MgSO4 alter yield and secondary metabolite profile of Rosa damascena under rainfed acidic conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar A., Gautam R.D., Singh S., et al. Phenotyping floral traits and essential oil profiling revealed considerable variations in clonal selections of damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):8101. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34972-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agarwal A., Gupta V., Haq S.U., Jatav P.K., Kothari S.L., Kachhwaha S. Assessment of genetic diversity in 29 rose germplasms using SCoT marker. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2019;31(4):780–788. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mostafavi A.S., Omidi M., Azizinezhad R., Etminan A., Badi H.N. Genetic diversity analysis in a mini core collection of Damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) germplasm from Iran using URP and SCoT markers. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s43141-021-00247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panwar S., Singh K.P., Sonah H., Deshmukh R.K., Prasad K.V., Sharma T.R. Molecular fingerprinting and assessment of genetic diversity in rose (Rosa × hybrida) Indian J Biotechnol. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simard M.J. Gene flow between crops and their wild relatives: book review. Evol Appl. 2010;3(4):402–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadeem M., Wang X., Akond M., Awan F.S., Riaz A., Younis A. Hybrid identification, morphological evaluation and genetic diversity analysis of ’Rosa x hybrida’ by SSR markers. Aust J Crop Sci. 2014;8(2):183–190. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aparna KB, T janakiram KP, DVS Raju SP. Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure of fragrant rose (Rosa× hybrida) cultivars using microsatellite markers. In: ICAR; 2019.

- 45.Gaurav A.K., Namita R.D., et al. Genetic diversity analysis of wild and cultivated Rosa species of India using microsatellite markers and their comparison with morphology based diversity. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;31(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s13562-021-00655-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engelhardt K.A.M., Lloyd M.W., Neel M.C. Effects of genetic diversity on conservation and restoration potential at individual, population, and regional scales. Biol Conserv. 2014;179:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nybom H., Carlson-Nilsson U., Werlemark G., Uggla M. Different levels of morphometric variation in three heterogamous dogrose species (Rosa sect Caninae, Rosaceae) Plant Syst Evol. 1997;204(3):207–224. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.