Abstract

Background

Prisons in Europe remain high-risk environments and conducive for infectious disease transmission, often related to injection drug use. Many infected people living in prison unaware of their infection status (HIV, hepatitis C). Despite all Council of Europe (CoE) member states providing community needle and syringe programmes (NSP), prison NSP are limited to seven countries. The study aim was to scrutinise the Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (CPT) reporting of periodic and ad hoc country mission visits to prisons, with an explicit focus on the extent to which member states are/were fulfilling obligations to protect prisoners from HIV/hepatitis C; and implementing prison NSP under the non-discriminatory equivalence of care principle.

Study design

Socio-legal review.

Methods

A systematic search of the CPT database was conducted in 2024 with no date restriction. All CPT reports were screened in chronological order with the terms; “needle”, “syringe”, “harm reduction” and “NSP”. Relevant narrative content on prison NSP operations, including repeat CPT reminders and any official/publicly expressed reasons for not implementing is presented.

Results

CPT reporting reveals limited prison NSP provision in selected prisons visited on mission, with little change in status over time, despite documented evidence of prior observations around absent/insufficient harm reduction measures and explicit (often longstanding) recommendations to address deficits. Reasons for not implementing prison NSP include; existing availability of opioid substitute treatment, lack of evidence for injecting drug use, for security and maintenance of order, and contradiction with prison protocols sanctioning drug use.

Conclusions

Prison health is public health. Regular research and evaluations of prison NSP in Europe are warranted. Future CPT visits should also continue to assess availability and standards of provision; recommend where appropriate including when opioid substitute treatment is already provided, and in line with broad availability of community NSP in Europe.

Keywords: Council of europe, European committee for the prevention of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment, CPT, HIV, Hepatitis C, Prison, Needle and syringe programme, Harm reduction

1. What this study adds to the existing evidence base

-

•

All Council of Europe member states provide community needle and syringe programmes (NSP), with prison NSP in Europe limited to seven countries.

-

•

Few process and outcome evaluations of prison NSP in Europe are available.

-

•

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (or CPT) routinely documents absent or insufficient harm reduction provision in prisons, and issues explicit (often longstanding) recommendations to address such deficits, including recommendation to provide prison NSP.

2. Implications for policy and practice

-

•

Prison health is public health, and given the human traffic cycling in and out of European prisons and the consequent bridge of infectious disease, we urge governments to initiate, pilot, operationalise and evaluate prison NSP.

-

•

Further research and evaluations of prison NSP in Europe are warranted to enhance the limited evidence base and inform public and prison health policy and practice.

-

•

All future CPT ad hoc and periodic country missions should assess availability and standards of prison NSP; recommend provision where appropriate including where opioid substitute treatment is already provided.

3. Background

The global prison population of 11.5 million on any given day has reached its highest level to date, increasing by 24 % since 2000 [1]. About one in five are detained for drug offences [1]. Prisoners are disproportionately affected by poor health, particularly relating to mental and drug use disorders and infectious diseases (HIV, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections) [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. The global burden of treatable mental disorders in prison populations is significant and often co-morbid (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychotic illness, alcohol or drug use disorder) [2,7,8]. High prevalence of infectious diseases is observed in prison populations [9]. The risk of acquiring HIV is 35 times higher among people who inject drugs (PWID) than among those who do not [10], and in countries with high incarceration rates of PWID, the prevalence of HIV in prisons can be 15 to 20 times that of the general population [3]. Where documented, HIV infection is strongly associated with a history of imprisonment in Europe, Russia, Canada, Brazil, Iran and Thailand [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. UNAIDS estimates that prisoners are seven times more likely to be living with HIV than adults in the general population; with women in prison disproportionately affected and five times more likely to living with HIV than women in the general population [5,17]. Hepatitis C is also a substantial concern, with one in six prisoners having a current or past hepatitis C virus infection [2]. Most recent analysis in 2022 indicates a global prevalence of hepatitis C virus among people in prison ranging from between 10 and 30 % over five continents (Asia, Europe, United States, Africa, Australia, Oceania) [18,19], with varying estimates of levels of antibody positivity [3,20]. Recent incarceration is associated with an 81 % and 62 % increased likelihood of HIV infection and hepatitis C virus infection among PWID (respectively) [21].

The combination of high prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C, and drug use disorder in prison populations, and the sharing of injecting drug equipment fuels a high risk environment for circulation of diseases, and onward transmission into the community [5,[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Many infected are unaware of their infection status [26]. Unsterile injecting of drugs is the most important independent determinant of HIV infection in prison [27], and is observed to contribute to transmission of both HIV and hepatitis C within prisons, rising incidence of infection and in some prisons has led to outbreaks (e.g. Australia, Scotland, Russia, Lithuania, Germany) [9,22,[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. Extent and patterns of drug injecting and needle sharing vary, and relate to available provision of safe injecting equipment; prisoners continue to inject drugs whilst in prison or initiate injecting, or switching from inhaling/snorting to intravenous drug use during their sentence mostly for economic reasons; generally with less frequent injecting but with much higher sharing of injecting equipment than in the community [3,22,27,33,34]. Cost of clean needles in prison also fuels shared drug injecting, often despite prisoner awareness of viral transmission risks [29]. Ultimately this fuels onward transmission of disease into the community on release [3,9,22].

3.1. Prison needle and syringe programmes (NSPs)

Harm reduction components form part of the comprehensive package of 15 interventions that are essential for effective HIV (and also hepatitis C) prevention, testing, treatment, care and support in prisons; and are effective in reducing injection of drugs, high risk behaviours and levels of infectious disease [5,24,[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. A significant proportion of incarcerated PWID however continue to lack access to these essential interventions, resulting in a persistent pattern of drug injection and consequent transmission of infection inside prisons [41,42]. Worldwide prison NSP have been implemented (with some suspended operations) in countries with adequate infrastructure and resourcing (e.g. Germany, Spain, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Canada, Portugal) and in countries with reduced resources (e.g. North Macedonia, Republic of Moldova, Armenia, Romania, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan); in male and female prisons of different capacities (generally 200–600 prisoners) and in one facility or across the domestic prison system [38,[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]]. In 2021, UNAIDS reported that 59 countries reported opioid substitute treatment (OST) in prison (an increase from 52 in 2017); and 10 countries provided prison needle and syringe programmes (NSP) in at least one facility (an increase from 8 in 2017) [5]. In 2023, Harm Reduction International also reported that 10 countries were implementing prison NSP (Ukraine, Moldova, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain, Switzerland, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Canada) [35].

Limited implementation of prison NSP (and decisions to cease operations) are generally due to political sensitivities around admitting drug use inside prisons, staff resistance, security concerns around needle stick injuries, fears around breaches of confidentiality by users, and lack of system focus on circulation of HIV and hepatitis C (including re-infection) in prisons [26,[46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. In countries where prison NSP are evaluated, findings potentially support their effectiveness (similar to community NSP) in reducing needle sharing, HIV and hepatitis C incidence, overdoses and abscesses; raising awareness of transmission risks; and generating more positive relationships with staff, with few negative consequences [43,49,9,37]. Optimal implementation of prison NSP takes time, and uptake can be hindered the structural incompatibility of the programme with prison system rules and operations which criminalise drugs; prisoner concerns for confidentiality and securitised surveillance; and changing drug availability inside prisons causing displacement from opioid use to novel psychoactive substances and anabolic steroids [26,[46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]].

3.2. Drug use and related harms in Europe prisons

The European prison population is just under ½ a million; with one in five awaiting trial (483,600 in 2022) [53]. It benefits from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Health in Prisons Programme which is the only one of its kind worldwide; with strategic objectives to monitor the health of prisoners and standards of detention, and strengthen the interface between national and prison health systems [[54], [55], [56], [57]]. The European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) supports the monitoring of drugs and related services in prison via the European Questionnaire on Drug Use among People living in prison (EQDP) and the European Facility Survey Questionnaire (EFSQ) [58]. Systematic reviews and prison data (where available) and varying by country indicate high levels of lifetime prevalence of drug use before imprisonment (especially of heroin, cocaine and amphetamines), compared with the general population, and emerging challenges of NPS in prison [58,59]. In 2023, the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe reported on a concerning rise in prevalence of mental health disorders (32.8 %) and drug use disorders (8 %) in the European prison population [6,60]. Whilst many prisoners cease injecting drug use on committal to prison in Europe, for those that continue, unsafe injecting practices are a major concern, particularly relating to substantial risk of transmission of HIV and hepatitis C [58].

3.3. Prison NSP in Europe: what do we know

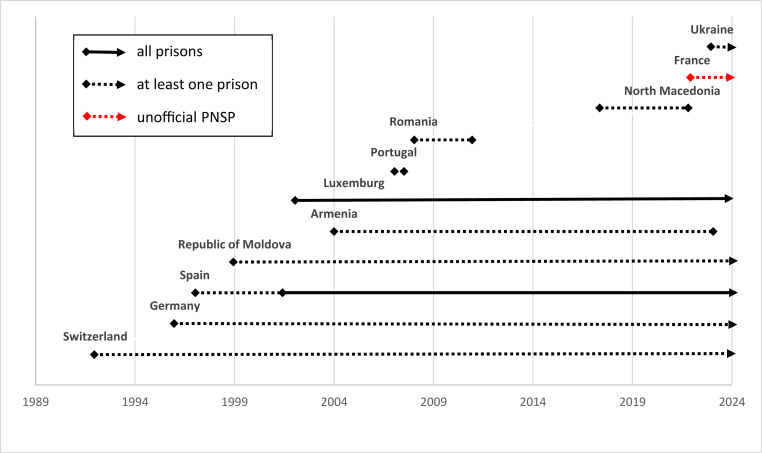

In 2023 the EMCDDA reported that all European Union member states and Norway had OST and NSP available in the community [61]. In contrast, availability and coverage of harm reduction interventions in European prisons are limited with 29 countries providing prison OST (albeit with low coverage, compared to the community) [42]. The most recent Harm Reduction International global data report indicates that prison NSP are (at the time of writing) provided in at least one facility in seven European countries (Germany, France, Luxembourg, Republic of Moldova, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine) [35]. There are anecdotal reports of an unofficial PNSP in France. There is no European or global monitoring data available on Liechtenstein and San Marino. Various trans-European and reviews on the status of PNSP provision have observed limited country level provision; ranging from pilot projects, to one or a small number of facilities or across the system [22,[42], [43], [44], [45],[62], [63], [64], [65], [66]]. The first prison NSP was operationalised in Switzerland in 1992 [67,68], closely followed by Germany between 1996 and 1998 [69,70], Spain in 1997 and 1998 [[71], [72], [73]], Republic of Moldova in 1999 and 2002 [74], and more recently a pilot was launched in the Ukraine in 2023 [35,75]. Since then the state of prison NSP provision is dynamic with various European countries assessing feasibility and piloting (e.g. Ukraine in 2023), providing with very limited coverage in only one facility for women out of 181 prisons in total (Germany), discontinuing (e.g. Armenia from 2004 to 2023; Romania from 2008 to 2011; North Macedonia from 2018 to 2022; Portugal terminated its pilot programme in 2007), providing with partial (Switzerland) and full or close to full coverage of PNSP provision (e.g. Republic of Moldova, Spain, Luxembourg), or are providing PNSP unofficially (France in Mont Pelier prior to 2022) [35,[42], [43], [44],62,75,76]. Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of PNSP provision in the Council of Europe Region since 1992.

Prison NSP models in Europe vary regarding access and distribution of sterile injecting equipment (via prison healthcare or counselling staff, automatic dispensing, external community health workers, civil society organizations and peer outreach). While the Republic of Moldova, Spain and Luxembourg offer close to full or full national coverage, Switzerland has NSP in 15 out of 89 prisons (e.g. Hindelbank women's prison, Champ-Dollon). In Germany, only one facility provides NSP (the Berlin prison for women Lichtenberg). Distribution methods also reflect diversity. Germany and Switzerland offer dispensing machines alongside prison staff for hand-to-hand distribution. Luxembourg only applies the latter. The Republic of Moldova utilises a peer-to-peer model, while Spain employs external personnel or civil society organizations.

Evaluations reported in Spain, the Republic of Moldova, Germany and Switzerland in prisons ranging in size from 200 to 600 prisoners [66] indicate that sharing of drug injecting equipment ceased or substantially declined along with favourable reductions in HIV and Hepatitis C incidence, overdoses and abscesses, and that used syringe disposal was unproblematic [45,[63], [64], [65],[69], [70], [71],73,74,[77], [78], [79], [80]]. These evaluations also reported that acceptance by the prison community of staff and prisoners improved over time, with crucial factors for successful implementation centring on political support and commitment, prison management buy-in; and the assurance of trust, ease of access and confidentiality, ideally supported by peer outreach. Other reported benefits included enhanced engagement of prisoners with drug use disorder treatment programmes in prison, increased prisoner awareness of transmission risks, and reduced accidental stick injuries during cell searches. Retractable syringes have been piloted in Switzerland but require further amendments and evaluation [81].

3.4. Human rights norms and standards: study rationale

International and European human rights framework's mandate that the State is obliged to take appropriate action to safeguard the health of prisoners, inclusive of including right to access free non-discriminatory healthcare equivalent to that available in the community; and inclusive of aspects of inspections and preventative medicine, environmental determinants of health, disease mitigation, prevention and treatment measures [[82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]]. The Council of Europe's (CoE) European Prison Rules and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (CPT) publish European prison standards which include focus on the medical care of prisoners and provision of and access to healthcare services in prison, including harm reduction measures; and engages in routine monitoring of same standards [88,89]. The European Prison Rules explicitly state that prisoners who use drugs should be permitted access to harm reduction measures (OST, NSP, condom and education programmes, psychosocial support) same as that which is available in the community so as to reduce transmission risks of HIV and viral hepatitis [88]. The CPT organises visits to prisons, in order to assess standards of detention and how prisoners are treated.

The study aim was to scrutinise the CPT reporting of prison visits during CPT ad hoc and periodic country missions, with an explicit focus on the extent to which member states are/were fulfilling obligations to protect people living in prison from HIV/hepatitis C; and implementing prison needle and syringe programmes under the non-discriminatory equivalence of care principle.

4. Methods

A socio legal study design was adopted, whereby a systematic search of the CoE CPT database was conducted with no date restriction, using the terms; “needle”, “syringe”, “harm reduction” and “NSP”. All relevant CPT reports of periodic and ad hoc country visits to selected prisons in the CoE region were scrutinized for reference to prison NSP. The final data set were systematically screened by author one, two and three with all relevant narrative content on prison NSP operations documented. We provide a tabular and mapping of CPT periodic and ad hoc mission documentation of CoE member states implementation or prohibition of prison NSP, recommendations for government to implement, and (where possible) the official State responses as to why prison NSP are prohibited.

5. Results

We could not locate CPT reference to prison NSP or prison harm reduction measures in any CPT reports for 19 countries (Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Norway, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Turkey, United Kingdom, Liechtenstein, Monaco and San Marino).

The earliest CPT report which referred to prison NSP was published in 2003 (visit to Germany from 3 to December 15, 2000 with the most recent report from 2024 reflecting a visit to North Macedonia from 2 to October 12, 2023). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of CPT reports by year and country.

| Year – Country |

|---|

| 2024 – Albania, Luxembourg, North Macedonia |

| 2023 – Austria, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Republic of Moldova, Netherlands, Portugal |

| 2022 – Belgium, Germany, Romania, Switzerland |

| 2021 – Armenia, Kosovoa, North Macedonia, Spain |

| 2020 – Denmark, Portugal, Spain |

| 2019 – Andorra, Denmark, Georgia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Romania |

| 2018 – Azerbaijan, Poland, Republic of Moldova |

| 2017 – Spain |

| 2016 – Armenia, Lithuania, Kosovoa, Republic of Moldova, Sweden, Switzerland |

| 2015 – Austria, Georgia, Luxembourg |

| 2014 – Poland, Ukraine |

| 2012 – North Macedonia |

| 2011 – Poland |

| 2009 – Portugal |

| 2007 – Denmark, Portugal, Spain |

| 2006 – Andorra, Republic of Moldova, Poland |

| 2004 – Luxembourg |

| 2003 – Germany |

All reference to Kosovo, whether to the territory, institutions or population, in this text shall be understood in full compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 and without prejudice to the status of Kosovo. As of October 2023 Kosovo is an accepted member candidate of the Council of Europe.

Despite the shifting landscape of prison NSP piloting, provision and discontinuation (see Fig. 1), the CPT only documented the presence of prison NSP in a small number of reports regarding prisons visited in Spain (Ávila Women's Prison Brieva, Castellón II Prison, Madrid V Prison Soto del Real, Madrid VII Prison Estremera, Seville I Prison, Seville II Prison, Valencia Prison Picassent, Alicante Penitentiary Psychiatric Hospital, Seville Penitentiary Psychiatric Hospital, León Prison, Puerto I Prison, Puerto III Prison, Teixeiro Prison, Villabona Prison, Tenerife Prison), Switzerland (Champ-Dollon, La Croisée), in Germany (Berlin prison for women, Lichtenberg), and in the three prisons visited in Republic of Moldova (Prison no. 4 in Cricova, Prison no. 13 in Chișinău and Prison no. 18 in Brănești). Reference was made to prison NSP starting in Luxembourg by the CPT report in 2023. No CPT report referred to prison NSP on visits to prisons in France.

There are direct observations by the CPT over time with regard to lack of broad based harm reduction measures in prisons including prison NSP (and OST, provision of disinfectant, awareness raising material around needle sterilisation, condoms) in selected prisons visited in several countries (e.g. Austria, Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Belgium, Denmark, Georgia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Ukraine and Kosovo) despite evidence for drug use and injecting inside prisons.

Official responses regarding rationale not to provide PNSP were documented in 11 CPT reports (Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Denmark, Germany, Latvia, Kosovo, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania and Sweden). Several prisons visited in Armenia, Austria and Germany indicated an official view that prisons already have OST so prison NSP is not required. Others provide hygiene packages (Azerbaijan) or bleach/cleaning fluid which were viewed as an appropriate alternative (Denmark; Portugal). Three refer directly to the contradiction of PNSP with the prison ethos to reduce drug use and promote abstinence (Denmark, Portugal, Sweden), and the prison protocol to sanction possession of equipment (Denmark). Four countries observe the lack of evidence of injection of drugs inside prisons or prisoner demand for NSP; for example, Romania which implemented PNSP from 2008 to 2011 reported a lack of demand, Kosovo observed there was no health indication to support the need for PNSP, and similarly the Netherlands and Sweden both reported that injection drug use is extremely rare in its prisons.

With regard to CPT recommendations for prison NSP; single recommendations were issued in to Armenia (2016), Belgium (2022), Sweden (2016), Denmark (2019), Germany (2022) and Netherlands (2023). Several countries received two recommendations; Austria (2015, 2023), Azerbaijan (2018, 2018), Georgia (2015, 2019), Kosovo (2016, 2021), and Romania (2019, 2022). Recommendations to implement prison NSP has been issued by the CPT on three occasions to Poland (2011, 2014, 2018) and Lithuania (2018, 2019, 2023). And to Portugal on four occasions (2007, 2009, 2020, 2023). See Table 2.

Table 2.

CPT reporting on (non) availability of prison NSP in selected prisons visited on mission here.

| Country CPT report narrative over time | Year of Visit | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | ||

| Finally, it is important that harm reduction measures (for example,needle exchange programmes, condom distribution, etc.) be introduced in prisons. The CPT recommends that the Albanian authorities develop a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems, as part of a wider national drugs strategy, taking into account the above remarks. |

2023 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2024): Report to the Albanian government on the periodic visit to Albania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 4 to May 15, 2023 [CPT/Inf (2024) 01]. Strasbourg. |

| Andorra | ||

| However, this care was not accompanied by measures to reduce the risk of infection (distribution of syringes, needlesand/or condoms). The CPT recommends that the Andorran authorities add a harm reduction component to its addiction care programme, in line with the recommendations of the Ministry of Health. | 2018 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Rapport au Gouvernement d’Andorre relatif à la visite effectuée en Andorre par le Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 29 janvier au 2 février 2018 [CPT/Inf (2019) 12]. Strasbourg. |

| For example, there was no drug-free therapeutic programme and no infectious risk reduction measures, such as condom provision orneedle exchange, were offered. (…) The CPT recommends that a strategy for assisting all drug users in prisons be drawn up, in the light of the above comments. | 2004 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2006): Rapport au Gouvernement d’Andorre relatif à la visite effectuée en Andorre par le Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 3 au 6 février 2004 [CPT/Inf (2006) 32]. Strasbourg. |

| Armenia | ||

| The penitentiary establishments of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Armenia implement the process of methadone substitution treatment programme for people suffering from drug addiction, which is considered a solution to the problem for those suffering from the mentioned diseases. | 2019 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2021): Response of the Armenian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Armenia from 2 to December 12, 2019 [CPT/Inf (2021) 11]. Strasbourg. |

| Harm-reduction measures are being carried out at 9 penitentiary institutions, which include thesingle-use syringe exchange, AIDS tests, condom availability programmes. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Response of the Armenian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Armenia from 5 to October 15, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 32]. Strasbourg. |

| However, as far as the delegation could ascertain there were no harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy, syringe and needle exchange programmes, provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and no specific psycho-socio-educational assistance. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Report to the Armenian Government on the visit to Armenia carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 5 to October 15, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 31]. Strasbourg. |

| Austria | ||

| It is currently not envisaged to implement aneedle-exchange programmein Austrian prisons since the prisons' substitution programme offers numerous ways of stabilising substance use in line with the requirements set out in the external (OST) guidelines. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Response of the Austrian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its periodic visit to Austria from 23 November to December 3, 2021 [CPT/Inf (2023) 04]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, none of the prisons visited had in place aneedle-exchange programme(whereas, as acknowledged by staff, used syringes and needles were regularly found within the establishments). Given the existence of needle-exchange programmes in the outside community, the CPT recommends that the Austrian authorities introduce such programmes in the prison system. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Report to the Austrian Government on the periodic visit to Austria carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 23 November to December 3, 2021 [CPT/Inf (2023) 03]. Strasbourg. |

| Althoughneedle-exchange programmeshave proven to be adequate prevention measures against hepatitis B/C and HIV infections, such measures are not yet allowed in Austrian prisons. But as intravenous administering of narcotics is quite common in Austrian prisons, needle-exchange programmes would be a useful method of health-care and are planned for the future. For the time being, “harm reduction” measures are taken by providing “take care” kits, lectures and trainings to staff members. | 2014 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2015): Response of the Austrian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Austria from 22 September to October 1, 2014 [CPT/Inf (2015) 35]. Strasbourg. |

| That said, none of the prisons visited had in place aneedle-exchange programme(whereas, as acknowledged by staff, used syringes and needles were regularly found within the establishments). Given the existence of needle-exchange programmes in the outside community, the CPT encourages the Austrian authorities to introduce such programmes in the prison system. | 2014 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2015): Report to the Austrian Government on the visit to Austria carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 22 September to October 1, 2014 [CPT/Inf (2015) 34]. Strasbourg. |

| Azerbaijan | ||

| Even thoughneedle exchange programmesare not implemented in prisons in the framework of the harm-reduction programs, the work is done on distribution of condoms and provision with hygiene packages. | 2016 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Response of the Azerbaijani Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Azerbaijan from 29 March to April 8, 2016 [CPT/Inf (2018) 36]. Strasbourg. |

| Even thoughneedle exchange programmesare not implemented in prisons in the framework of the harm-reduction programs, the work is done on distribution of condoms and provision with hygiene packages | 2016 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Response of the Azerbaijani Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Azerbaijan from 29 March to April 8, 2016 [CPT/Inf (2018) 36]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, there were still no harm-reduction measures (e.g. distribution of condoms,syringe and needle exchange programmes, provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and only some specific limited psycho-socio-educational assistance (offered by psychologists employed in the framework of a project financed by the Global Fund) was available. | 2016 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Report to the Azerbaijani Government on the visit to Azerbaijan carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 29 March to April 8, 2016 [CPT/Inf (2018) 35]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, as far as the delegation could ascertain there were no harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy, syringe andneedle exchange programmes,provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and only some specific psycho-socio-educational assistance (offered by psychologists employed in the framework of a project financed by the Global Fund) | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Report to the Azerbaijani Government on the visit to Azerbaijan carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 15 to June 22, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2018) 33]. Strasbourg. |

| Belgium | ||

| However, despite the CPT's repeated recommendations, no risk reduction measures measures (e.g. information on how to sterilise equipment used for injecting substances,syringe exchange programmes) had been introduced. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022): Rapport au Gouvernement de Belgique relatif à la visite effectuée en Belgique par le Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 2 au 9 novembre 2021 [CPT/Inf (2022) 22]. Strasbourg. |

| Denmark | ||

| The Department of the Prison and Probation Service can advise that in 1996, a cleaning fluid scheme was introduced (…), with the possibility of using cleaning fluid to clean syringes and needles before use. (…) The scheme was made permanent in 2000. Since the cleaning fluid scheme is already in place, the Prison and Probation Service has decided not to introduce thesyringe exchange scheme. (…) with the current cleaning fluid scheme there is an acceptable offer for the addicts. (…) it may seem inconsistent to hand out syringes and needles to the prisoners at the same time as the Prison and Probation Service actively seeks to reduce drug abuse and prevent possession of tools in prisons and remand prisons, and where possession of such objects is generally subject to disciplinary punishment. | 2019 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2020): Response of the Danish Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Denmark from 3 to April 12, 2019 [CPT/Inf (2020) 26]. Strasbourg. |

| It would be desirable to expand this good practice, e.g. by also providing condoms at prison infirmaries, in the establishments visited and in all other prisons in Denmark. Furthermore, other prevention services should be made available, such asneedle and syringe exchange programmesand relevant vaccination. | 2019 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Report to the Danish Government on the visit to Denmark carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 3 to April 12, 2019 [CPT/Inf (2019) 35]. Strasbourg. |

| Drug abusers in the prisons have access to disinfectant liquids. The purpose is to give injecting drug addicts, who share needles and syringes, a possibility to cleanse them in order to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV, Hepatitis B and C. The programme should be seen as an alternative todispensing sterile syringes. Such a programme has not been introduced in Danish prisons | 2002 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2007): Response of the Danish Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Denmark from 28 January to February 4, 2002 [CPT/Inf (2007) 46]. Strasbourg. |

| Georgia | ||

| Further, there were no harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy,syringe and needle exchange programmes, provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and almost no specific psycho-socio educational assistance. (…) The Committee calls upon the Georgian authorities to develop and implement a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems (as part of a wider national drugs strategy) including harm reduction measures, in the light of the above remarks | 2018 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Report to the Georgian Government on the visit to Georgia carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 10 to September 21, 2018 [CPT/Inf (2019) 16]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, there were no harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy,syringe and needle exchange programmes, provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and no specific psycho-socio-educational assistance.(…) The Committee would like to receive more information on this subject, including the time-line for the implementation of the new programmes. In this context, the CPT also recommends that the Georgian authorities take duly into account the Committees remarks set out above. | 2014 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2015): Report to the Georgian Government on the visit to Georgia carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 1 to December 11, 2014 [CPT/Inf (2015) 42]. Strasbourg. |

| Germanyb | ||

| All the Länder offer comprehensive addiction treatment programmes in prison, especially substitution treatment. Against this backdrop, it is not considered necessary to introduce aneedle and syringe exchange programme. Among the main arguments against introducing such a programme are reasons of security and order, in particular the need to avert potential danger to the life and limb of (fellow) prisoners and staff. | 2020 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022): Response of the German Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its periodic visit to Germany from 1 to December 14, 2020 [CPT/Inf (2022) 19]. Strasbourg. |

| Moreover, it is praiseworthy that aneedle and syringe exchange programmewas in place at Berlin Prison for Women. The CPT encourages the prison authorities of all other Länder to introduce a needle and syringe exchange programme in prisons. | 2020 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022): Report to the German Government on the periodic visit to Germany carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 1 to December 14, 2020 [CPT/Inf (2022) 18]. Strasbourg. |

| “Needle exchange programmes” are rejected by most Federal Länder for fundamental reasons; in the Länder of Berlin and Lower Saxony they are however being tried out for reasons of healthcare in pilot tests. | 2000 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2003): Response of the German Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Germany from 3 to December 15, 2000 [CPT/Inf (2003) 21]. Strasbourg. |

| Kosovoa | ||

| However, as in the past, in none of the establishments visited were there any harm-reduction measures (such asneedle-exchange programmes), although such measures are apparently available to the community at large. The CPT encourages the relevant authorities to further develop the programme for the management of prisoners with drug dependence, in the light of the above remarks. | 2020 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2021): Report to the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) on the visit to Kosovoa carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 6 to October 16, 2020 [CPT/Inf (2021) 23]. Strasbourg. |

| Needle exchange programis not available yet for many reasons. Main reason for as is that yet we do not have health indications for it at Kosovo Prisons. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Response of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Kosovoa from 15 to April 22, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 24]. Strasbourg. |

| However, none of the establishments visited had put in place any harm reduction measures (such as the provision of bleach and information on how to sterilise needles orneedle-exchange programmes), although the delegation was told that such programmes were available to the general public. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Report to the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) on the visit to Kosovoa carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 15 to April 22, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 23]. Strasbourg. |

| Latvia | ||

| The distribution of syringes and needles to imprisoned persons is not provided for in the Latvian legislation. | 2011 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2013): Responses of the Latvian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Latvia from 5 to September 15, 2011 [CPT/Inf (2013) 21]. Strasbourg. |

| Lithuania | ||

| However, despite the CPT's repeated recommendations, no harm reduction measures (for example, information on how to sterilise material used for injecting drugs,needle-exchange programmesetc.) or preventive measures (for example, the supply of condoms) have been introduced so far. (…) The Committee calls upon the Lithuanian authorities to finally develop and implement a comprehensive strategy for the provision of medical and psychosocial assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems, taking into account the above remarks. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Report to the Lithuanian Government on the periodic visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 10 to December 20, 2021 [CPT/Inf (2023) 01]. Strasbourg. |

| The Lithuanian authorities were urged to develop a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems and to put an end to the supply of drugs, reduce the demand and provide prisoners concerned with the necessary assistance including harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy,syringe and needle exchange programmes) and specific psycho-socio-educational support. (…) Further, there was still nothing on offer in terms of harm reduction, such as asyringe and needle exchange, distribution of condoms, etc. (…) Furthermore, the Committee calls upon the Lithuanian authorities to fully implement its long-standing recommendation on the need to develop a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug related problems (as part of a wider national drugs strategy). | 2018 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Report to the Lithuanian Government on the visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 20 to April 27, 2018 [CPT/Inf (2019) 18]. Strasbourg. |

| Unfortunately, the situation in this respect had worsened since the 2012 visit, mainly because hardly anything had been done to put an end to the supply of drugs, reduce the demand and provide prisoners concerned with necessary assistance including harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy,syringe and needle exchange programmes) and specific psycho-socio-educational support. (…) The CPT urges the Lithuanian authorities to develop a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems (as part of a wider national drugs strategy), in the light of the above remarks. | 2016 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Report to the Lithuanian Government on the visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 5 to September 15, 2016 [CPT/Inf (2018) 2]. Strasbourg. |

| An anonymous survey was carried out among the prisoners of the three penal institutions (the Alytus Correction House, the Marijampole Correction House and the Vilnius CorrectionHouse No.2). The total number of respondents was 994 inmates. The goal of the survey was to find out the opinion of the inmates about the real degree of spread of drug use at the penalinstitutions and also, their attitude towards the harm reduction (needle exchange) program. | 2004 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2006): Response of the Lithuanian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Lithuania from 17 to February 24, 2004 [CPT/Inf (2006) 10]. Strasbourg. |

| Luxembourgaa | ||

| Theneedle exchange programmewill begin shortly. Procedural issues have yet to be resolved. | 2023 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2024). Réponse du Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg au rapport du Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) relatif à sa visite effectuée Luxembourg du 27 mars au 4 avril 2023 [CPT/Inf (2024) 13]. Strasbourg. |

| However, at the CPU, theneedle exchange programmewas not yet operational but, according to the information gathered by the delegation, was due to start shortly. The Committee would like to receive confirmation that the needle exchange programme at the CPU is operational. | 2023 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023). Rapport au Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg relatif à la visite périodique effectuée au Luxembourg par le Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 27 mars au 4 avril 2023 [CPT/Inf (2023) 26]. Strasbourg |

| Drug addicts were cared for by the “programme Tox“. A multidisciplinary team monitored drug addicts and offered aneedle and syringe exchangeprogramme. Compared with the previous visit, drug-related problems seemed to have decreased. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2015). Rapport au Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg relatif à la visite effectuée au Luxembourg par le Comité européen pour la prevention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 28 janvier au 2 février 2015 [CPT/Inf (2015) 30]. Strasbourg. |

| The “Global project for the care of drug-dependent persons in prisons” or “Tox Project” is financed by the Fonds de lutte contre la toxicomanie and provides for the following actions for 2003–2004: (…)Exchange of syringesin prison. | 2003 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2004). Réponse du Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg au rapport du Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) relatif à la visite effectuée au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg du 2 au 7 février 2003 [CPT/Inf (2004) 13]. Strasbourg. |

| Montenegro | ||

| The delegation also noted that there were no additional therapeutic activities arranged for inmates suffering from drug addiction, for example, the establishment of drug-free units, harm reduction tools such as asyringe and needle exchange, distribution of condoms, etc. Overall, there was a lack of a multi-disciplinary strategy to decrease the supply of and demand for drugs. The CPT recommends that the above precepts be addressed by the Montenegrin authorities and substitution therapy be provided to all inmates in need, rather than only to those who had previously been prescribed therapy before admission. Such an approach would be consistent with that already being followed in the community at large. | 2017 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Report to the Government of Montenegro on the visit to Montenegro carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 9 to October 16, 2017 [CPT/Inf (2019) 2]. Strasbourg. |

| North Macedonia | ||

| Given the availability of drugs, and moreover the number of prisoners who were confirmed as injecting drugs, and the absence of a comprehensive approach that included, inter alia harm reduction education andneedle exchange programmes, the number of prisoners infected with hepatitis C was likely to be high, in particular at Idrizovo Prison. | 2023 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2024). Report to the Government of North Macedonia on the visit to North Macedonia carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 2 to October 12, 2023 [CPT/Inf (2024) 17]. Strasbourg. |

| Given the availability of drugs and moreover the number of prisoners who were confirmed as injecting drugs and the absence of a comprehensive approach that included inter alia harm reduction education andneedle exchange programmes(…). | 2019 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2021). Report to the authorities of North Macedonia on the visit to North Macedonia carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 2 to December 10, 2019 [CPT/Inf (2021) 8]. Strasbourg. |

| In this respect, at Idrizovo Prison, the delegation observed that prison staff and inmates had little understanding about the most prevalent disease in the establishment, hepatitis C, and that no measures were taken by health care staff to raise awareness of the risk factors associated with its transmission, or to provide advice for at-risk groups (needle sharing, tattooing, etc.). A similar state of affairs was observed in Skopje and Štip Prisons. The CPT reiterates its recommendation that the national authorities ensure that prison health care services take a proactive role towards preventive health care in prisons. This should include instituting a health information programme in all prisons about transmissible diseases, and providing prison staff with specific training on the issue of transmissible diseases. | 2010 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2012). Report to the Government of “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” on the visit to “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 21 September to October 1, 2010 [CPT/Inf (2012) 4]. Strasbourg |

| Netherlands | ||

| The injection of drugs such as heroin in the Netherlands is extremely rare. This means there is no need for aneedle exchange programme. | 2022 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Response of the Government of the Netherlands to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to the Kingdom of the Netherlands from 10 to May 25, 2022 [CPT/Inf (2023) 13]. Strasbourg. |

| The CPT recommends that the Dutch authorities take further steps to provide support to detained persons in dealing with substance-use issues as well as various treatment options, including opioid agonist therapy, rehabilitative programmes and harm reduction measures (includingneedle-exchange programmes). | 2022 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Report to the Government of the Netherlands on the periodic visit to the Kingdom of the Netherlands carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 10 to May 25, 2022 [CPT/Inf (2023) 12]. Strasbourg. |

| Poland | ||

| However, despite the CPT's repeated recommendations, no harm reduction measures (e.g. information on how to sterilise material used for injecting drugs,needle-exchange programmes) or preventive measures (e.g. the supply of condoms) were introduced | 2017 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018): Report to the Polish Government on the visit to Poland carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 11 to May 22, 2017 [CPT/Inf (2018) 39]. Strasbourg. |

| However, none of the prisons visited had put in place any harm reduction measures (such as, for instance, the provision of bleach and information on how to sterilise needles,needle-exchange programmesor the supply of condoms) | 2013 | Report to the Polish Government on the visit to Poland carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 5 to June 17, 2013 [CPT/Inf (2014) 21]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, none of the establishments visited had in place harm-prevention measures (such as, for instance, the provision of bleach and information on how to sterilise needles,needle-exchange programmesor the supply of condoms). | 2009 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2011): Report to the Polish Government on the visit to Poland carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 26 November to December 8, 2009 [CPT/Inf (2011) 20]. Strasbourg. |

| The new programme of exchangingneedles and syringesis prepared. | 2004 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2006): Response of the Polish Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Poland from 4 to October 15, 2004 [CPT/Inf (2006) 12]. Strasbourg. |

| Portugal | ||

| Santa Cruz do Bispo Women's Prison Addictive Pathologies Unit: (…) Regarding possible ‘exchange programmes and availability ofneedles and syringes’, the vision of this team is to promote abstinence, and therefore the consideration of safe practices of self-administration of narcotic substances in prison environment was not considered coherent. | 2022 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Response of the Portuguese Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Portugal from 23 May to June 3, 2022 [CPT/Inf (2023) 36]. Strasbourg. |

| There were no harm reduction interventions in prison to reduce the transmission of blood-borne viruses (i.e.needle and syringe programmes, take-away naloxone, access to condoms, etc.). The CPT recommends that the Portuguese authorities take the necessary steps to introduce such interventions in Tires and Santa Cruz do Bispo Feminino Prisons and in other prison establishments as needed. Information, education and counselling should be widely implemented, including awareness on risks of overdosing. In undertaking such programmes, attention should be paid to the fact that not all prisoners are literate. Full information on the existence of such harm reduction programmes should be given to inmates by healthcare staff immediately after committal. | 2022 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023): Report to the Portuguese Government on the periodic visit to Portugal carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 23 May to June 3, 2022 [CPT/Inf (2023) 35]. Strasbourg. |

| Condoms could be obtained from the infirmary, butno needle or syringe exchange programmesexisted at the establishments visited. Consideration should be given to establishing such programmes. | 2019 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2020): Report to the Portuguese Government on the visit to Portugal carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 3 to December 12, 2019 [CPT/Inf (2020) 33]. Strasbourg. |

| The implementation of the Pilot-Program onNeedle Exchangehas occurred, on the whole, as programmed: it has included the disclosure and dissemination of information and enlightenment sessions directed to prison staff and prisoners. The Regulation of the Program was approved and, in each Prison Establishment involved, the respective Internal Rules of Procedure were endorsed. | 2008 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2009): Response of the Portuguese Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Portugal from 14 to January 25, 2008 [CPT/Inf (2009) 14]. Strasbourg. |

| The delegation was also informed about a pilot project concerning the introduction ofneedle exchange programmesin two prisons. The CPT would like to receive updated information on these pilot projects. | 2008 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2009): Report to the Portuguese Government on the visit to Portugal carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 14 to January 25, 2008 [CPT/Inf (2009) 13]. Strasbourg. |

| Until now, the benefits ofneedle exchange programshave not yet been realized. Consideration, referred to in paragraph 89 of the Report. Nevertheless, the Ministries of Justice and Health have entered into an agreement for the collection of information, the study and evaluation allowing a final decision to be made on this issue. | 2003 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2007): Réponse du Gouvernement du Portugal au rapport du Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) relatif à sa visite au Portugal du 18 au 26 novembre 2003 [CPT/Inf (2007) 14]. Strasbourg. |

| In all the establishments visited, the prevention measures were almost non-existent. Thus, in Faro, bleach, used to sterilise syringes, was only provided if it was expressly requested by the inmate, and in no establishment was there aneedle exchange program. The CPT seeks comments from the authorities Portuguese on this point | 2003 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2007): Rapport au Gouvernement du Portugal relatif à la visite effectuée au Portugal par le Comité européen pour la prevention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 18 au 26 novembre 2003 [CPT/Inf (2007) 13]. Strasbourg. |

| Romania | ||

| At the same time, thesyringe exchange programwas carried out at the level of the penitentiary units between 2008 and 2011. After this moment, there were no further requests from persons deprived of their liberty for entry into this program. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022): Response of the Romanian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its ad hoc visit to Romania from 10 to May 21, 2021 [CPT/Inf (2022) 07]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, no harm reduction measures were in evidence such as aneedle and syringe exchangeprogramme (NSP) or prevention group discussions.(…) The CPT recommends once again that the Romanian authorities ensure that a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems (as part of a wider national drugs strategy) is operating effectively throughout the prison system. Access to OAT should be facilitated and be managed by health care providers in the prisons (e.g. the GP's). Harm reduction measures (i.e. condom distribution, needle exchange programmes) should be introduced forthwith in all prisons. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022): Report to the Romanian Government on the ad hoc visit to Romania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 10 to May 21, 2021 [CPT/Inf (2022) 06]. Strasbourg. |

| At the same time, no harm reduction measures were in evidence such as aneedle and syringe exchange programme(NSP) or the distribution of condoms (condoms were only made available to prisoners having intimate visits). (…) The CPT recommends that the Romanian authorities ensure that a comprehensive strategy for the provision of assistance to prisoners with drug-related problems (as part of a wider national drugs strategy) is operating effectively throughout the prison system. Access to OST should be facilitated and be managed by health care providers in the prison. Harm reduction measures (i.e. condom distribution,needle exchange programmes) should be introduced forthwith in all prisons. | 2018 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2019): Report to the Romanian Government on the visit to Romania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 7 to February 19, 2018 [CPT/Inf (2019) 7]. Strasbourg. |

| Republic of Moldovaaa | ||

| 57. As for the treatment of drug use, it is positive thatneedle exchange programmeswere in place in the three prisons visited (…). | 2022 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2023). Report to the Moldovan Government on the ad hoc visit to the Republic of Moldova carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 5 to December 13, 2022 [CPT/Inf (2023) 27]. Strasbourg. |

| It is also commendable that harm reduction measures (such as the distribution ofneedles/syringesand condoms to prisoners through their peers) were in place in both prisons for the prevention of transmissible diseases. That said, the CPT considers that these procedures could be further improved, for example, by collecting data regarding the numbers of needles/syringes returned by prisoners. | 2018 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2018). Report to the Government of the Republic of Moldova on the visit to the Republic of Moldova carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 5 to June 11, 2018 [CPT/Inf (2018) 49]. Strasbourg. |

| Further, the CPT was pleased to note that there was aneedle-exchange programmein place at Soroca Prison. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016). Report to the Government of the Republic of Moldova on the visit to the Republic of Moldova carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 14 to September 25, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 16]. Strasbourg. |

| At Colony No. 4, aneedle exchange programmefor drug users had existed since May 2002. According to the information gathered by the delegation, other needle exchange programmes exist in two other prisons. The CPT notes the existence of such programmes to prevent the infectious risks associated with drug use and wishes to emphasise that appropriate treatment for drug dependence must also include the creation of medico-psycho-socio-educational detoxification programmes and substitution programmes for opiate-dependent patients who are unable to stop using opiates. | 2004 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2006). Rapport au Gouvernement de la République de Moldova relatif à la visite effectuée en Moldova par le Comité européen pour la prevention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 20 au 30 septembre 2004 [CPT/Inf (2006) 7]. Strasbourg. |

| Spainaa | ||

| (…) Further,needle and syringe exchange programmeswere in place. | 2020 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2021). Report to the Spanish Government on the visit to Spain carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 14 to September 28, 2020 [CPT/Inf (2021) 27]. Strasbourg. |

| Needle and syringe exchange programmesexisted at the establishments visited. | 2020 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2020). Report to the Spanish Government on the visit to Spain carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 6 to September 13, 2018 [CPT/Inf (2020) 5]. Strasbourg. |

| Harm reduction measures such asneedle exchangecontinued to be implemented at the establishments visited with the exception of Puerto I, II, III and Sevilla II Prisons, due to the lack of support by the regional health authorities of Andalusia. The CPT recommends that the Spanish authorities take the appropriate measures in order to harmonise the approach to the provision of harm reduction measures to inmates affected by drug addiction nationwide. | 2016 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2017). Report to the Spanish Government on the visit to Spain carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 27 September to October 10, 2016 [CPT/Inf (2017) 34]. Strasbourg. |

| It has been precisely the well-structured policy for the prevention of contagious illnesses in the area of drug-dependencies has merited particular approval by the CPT, as it has confirmed the existence ofneedle exchange programmesat two of the prison centres visited, along with other similar preventative measures. | 2003 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2007). Response of the Spanish Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Spain from 22 July to August 1, 2003 [CPT/Inf (2007) 29]. Strasbourg. |

| The CPT welcomes the existence of aneedle exchange programmein both establishments. Thirteen prisoners were participating in such a programme at Tenerife Prison and 19 at Villabona Prison. There were no particular requirements for enrolment, and the programmes were operating in a satisfactory manner and without incident since they had been set up. | 2003 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2007). Report to the Spanish Government on the visit to Spain carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 22 July to August 1, 2003 [CPT/Inf (2007) 28]. Strasbourg. |

| Sweden | ||

| As regards the question of initiatives such asneedle exchangewithin the Prison and Probation institutions the need must be set against the possible security risk posed by possession of needles. An important condition for enabling the Prison and Probation Service to give inmates of prisons and remand prisons the opportunity to stop misusing and committing crimes is that the institutions are entirely free from drugs. (…) the incidence of narcotics is very low in the Swedish Prison and Probation Service institutions. (…) it is not relevant to introduce needle exchange activities in the Swedish Prison and Probation Service. The other components ofneedle exchange activities, including advice, testing and vaccination, will, however, be offered to inmates of prisons and remand prisons on the same terms as other people in society at large. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Response of the Swedish Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Sweden from 18 to May 28, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 20]. Strasbourg. |

| however, as far as the delegation could ascertain, there were no harm-reduction measures (e.g. substitution therapy,syringe and needle exchange programmes, provision of disinfectant and information about how to sterilise needles) and no specific psycho-socio-educational assistance. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016): Report to the Swedish Government on the visit to Sweden carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 18 to May 28, 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 1]. Strasbourg. |

| Switzerlandaa | ||

| In August 2020, the Vaud Prison Service (SPEN), in close collaboration with the Vaud University Hospital, set up the PREMIS pilot project (sterileinjection material exchange programme) at La Croisée Prison. | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022). Réponse du Conseil fédéral Suisse au rapport du Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) relatif à la visite effectuée en Suisse du 22 mars au 1er avril 2021 [CPT/Inf (2022) 10]. Strasbourg |

| (…)As for harm reduction policy, Champ-Dollon prison had set up a needle exchange programme. In addition, it was explained after the visit that a pilotneedle exchange programmehad been initiated in a prison in the canton of Vaud (La Croisée). | 2021 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2022). Rapport au Conseil fédéral suisse relatif à la visite effectuée en Suisse par le Comité européen pour la prévention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 22 mars au 1 er avril 2021 [CPT/Inf (2022) 9]. Strasbourg. |

| With regard to drug addiction in prisons, the delegation noted the comprehensive and accessible range of preventive and therapeutic care available at Champ-Dollon prison. Appropriate risk reduction measures such as condom distribution,needle exchange programmesand therapy were offered to prisoners. | 2015 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2016). Rapport au Conseil fédéral Suisse relatif à la visite effectuée en Suisse par le Comité européen pour la prevention de la torture et des peines ou traitements inhumains ou dégradants (CPT) du 13 au 24 avril 2015 [CPT/Inf (2016) 18]. Strasbourg. |

| Ukraineaa | ||

| Further, none of the establishments visited had put in place any harm reduction measures (such as the provision of bleach and information on how to sterilise needlesor needle-exchange programmes). | 2013 | European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) (2014). Report to the Ukrainian Government on the visit to Ukraine carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 9 to October 21, 2013 [CPT/Inf (2014) 15]. Strasbourg |

All reference to Kosovo, whether to the territory, institutions or population, in this text shall be understood in full compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 and without prejudice to the status of Kosovo. As of October 2023 Kosovo is an accepted member candidate of the Council of Europe.

Countries currently providing prison NSP according to most recent global reporting in 2023 (Germany, France, Luxembourg, Republic of Moldova, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine). No CPT report referred to prison NSP on visits to prisons in France.

6. Discussion

This year is the twenty year anniversary of the 2004 Dublin Declaration on Partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia [87] which emphasised HIV as an important political priority and provided a framework for mounting an effective response to HIV/AIDS and co-infections (Hepatitis C, tuberculosis) in the prisons, and emphasised the right of prisoners to protect themselves against infections. Our unique assessment of CPT reporting of visits to selected prisons in the CoE region overtime since the first CPT reference to prison NSP in 2000 (Germany) reveals very limited provision of NSP in selected prisons visited during mission visits in Europe, with small changes in status including piloting and discontinuation over time, despite documented evidence of prior CPT observations around absent or insufficient harm reduction measures and explicit (often longstanding) recommendations to address programme deficits by including prison NSP.

The situation remains rather static, despite evidence for broad based acceptability and effectiveness of NSP in the community setting across Europe [61], and positive evaluations in the small number of countries who has implemented to varying degrees (pilot, limited number of facilities, system wide) [22,[42], [43], [44], [45],[63], [64], [65], [66]]. The assessment provides unique insight into CPT visits to selected prisons during period and ad hoc missions across Europe, and findings support previous European assessments, editorials and commentaries which underscore the glaring discrepancy concerning international recommendations regarding harm reduction, both weak and encouraging evaluation findings of prison NSP in some countries and continued reluctance to implement (or scale up) by many government actors in Europe [26,[42], [43], [44], [45],49,62,65,76]. Official responses to refuse prison NSP often given without empirical data, centre on denial of drug use occurring in prisons, the clash between prison based abstinence and security protocols, and the existing access to OST. This is contra the comprehensive package which recommends delivery as a whole package to achieve greatest impact in preventing transmission of HIV and viral hepatitis [5]. Harm-reduction programmes can be implemented in prisons without increasing drug use, or posing a security risk or potential for harm to prisoners or staff [90]. The same accounts for OST, which often show a high risk of additional side consumption of (often) injectable drugs [91]. Denmark and Portugal are the only countries reported by the CPT to provide disinfectant. This socio-legal assessment highlights the discrepancy in access to preventive healthcare between community and prison, as current coverage of community NSP across Europe is strong. By not implementing prison NSP as part of the comprehensive package of prison based HIV interventions [24], member states are also disregarding the WHO guidance which first publicly supported prison NSP in 1993 [92], and more recently reaffirmed its position regarding the comprehensive package in 2023 [39]. From an ethical point of view and also in accordance with the Mandela Rules (Rule 27.2), the decision to provide clean syringes and needles for PWID in prison is a clinical decision that “may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff”. Lack of prison NSP availability violates the prisoner's right to access equivalent non-discriminatory health care and protection whilst deprived of their liberty, and their general right to health under the international human rights framework. Failure to implement prison NSP in any setting cannot be justified by perceived lack of demand or sufficient evidence [93]. The evidence base in support of community NSP is substantial with regard to HIV transmission reduction, and mixed with regard to hepatitis C transmission [[94], [95], [96]].