ABSTRACT

Background

The occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) was associated with an increased mortality rate among acute pancreatitis (AP) patients, indicating the importance of accurately predicting the mortality rate of critically ill patients with acute pancreatitis–associated acute kidney injury (AP-AKI) at an early stage. This study aimed to develop and validate machine learning–based predictive models for in-hospital mortality rate in critically ill patients with AP-AKI by comparing their performance with the traditional logistic regression (LR) model.

Methods

This study used data from three clinical databases. The predictors were identified by the Recursive Feature Elimination algorithm. The LR and two machine learning models—random forest (RF) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—were developed using 10-fold cross-validation to predict in-hospital mortality rate in AP-AKI patients.

Results

A total of 1089 patients from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) and eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) were included in the training set and 176 patients from Xiangya Hospital were included in the external validation set. The in-hospital mortality rates of the training and external validation sets were 13.77% and 54.55%, respectively. Compared with the area under the curve (AUC) values of the LR model and the RF model, the AUC value of the XGBoost model {0.941 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.931–0.952]} was significantly higher (both P < .001) and the XGBoost model had the smallest Brier score of 0.039 in the training set. In the external validation set, the performance of the XGBoost model was acceptable, with an AUC value of 0.724 (95% CI 0.648–0.800). However, it did not differ significantly from the LR and RF models.

Conclusions

The XGBoost model was superior to the LR and RF models in terms of both the discrimination and calibration in the training set. Whether the findings can be generalized needs to be further validated.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, acute pancreatitis, eICU-CRD, in-hospital mortality, machine learning, MIMIC-IV

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

The occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) was associated with an increased mortality rate of acute pancreatitis (AP), indicating the importance of accurately predicting the mortality rate of critically ill patients with AP-AKI at an early stage.

This study adds:

The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model was superior to the logistic regression and random forest models in terms of both the discrimination and calibration in the training set with data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV and eICU Collaborative Research Database.

Potential impact:

It is suggested to use the XGBoost model for better prediction of in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with AP-AKI in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a leading cause of hospitalization for gastrointestinal diseases worldwide [1–3]. Numerous studies of different regions have reported a consistent increase in the incidence and hospitalization rates of AP [4–7]. Acute pancreatitis–associated acute kidney injury (AP-AKI) is one of the most common complications associated with AP [8–10]. The reported incidence of AP-AKI varies across studies, ranging from 7.9% to 69.3% [8, 11–13]. AKI is considered a primary cause of mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with AP [12]. Previous studies have indicated that AKI could increase the mortality rate of AP patients by ≈5–6 times [4, 9] and its mortality rate was reported to be 80% in patients with severe AP [11, 12]. Therefore, accurately predicting the mortality rate of critically ill patients with AP-AKI at an early stage is of utmost importance.

Machine learning (ML) is a multidisciplinary field that combines mathematics with computer science. Its primary focus is on extracting knowledge from extensive datasets that encompass numerous variables and can handle intricate clinical information [14]. ML relies on mathematical algorithms to detect potential patterns within data, and its versatile algorithms, such as the commonly used algorithms eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and random forest (RF), become increasingly important in clinical data analysis. ML enables the development of robust risk models and enhances prediction capabilities, making it widely applicable in disease prediction, including the assessment of mortality rate in critically ill patients [14]. Several studies on ML models for predicting mortality rate or hospital prognosis in patients with AP or AKI have been reported [15–17]. However, currently there is a lack of research specifically focused on the development of an ML-based predictive model for in-hospital mortality rate in AP-AKI patients. Clinical severity scoring systems, such as the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Logistic Organ Dysfunction System (LODS), are commonly used to assess disease severity and mortality risk in critically ill patients [18–21]. Traditional logistic regression (LR) models are also frequently employed to predict mortality rate in critically ill patients. Nevertheless, methodological limitations in their clinical application have been indicated, including but not limited to low specificity and sensitivity, inadequate discriminative power and subpar prediction accuracy [20, 22, 23]. ML has shown potential advantages over traditional scoring systems and LR, exhibiting superior predictive performance [22, 24]. Hence it is necessary to develop an ML-based predictive model for assessing in-hospital mortality rate in critically ill AP-AKI patients, which can help accurately predict those with high risk of in-hospital mortality at an early stage in clinical practice.

Previous studies have identified some factors that may contribute to in-hospital mortality in AP-AKI patients [8, 25, 26]. Specifically, laboratory indicators included peak serum creatinine (SCr) >3 mg/dl and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) [25], comorbidities included circulatory failure and chronic diseases [4, 25, 26] and treatment requirements included the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) and mechanical ventilation [4, 13, 25]. However, the sample size of these studies was limited, with a range from 44 to 287, and there is still a lack of comprehensive assessment of potential predictive factors [4, 8, 12, 13]. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate ML-based predictive models for in-hospital mortality rate in critically ill patients with AP-AKI by employing a large sample size and comprehensively assessing the role of demographic characteristics, laboratory indicators, vital signs, comorbidities and treatment requirements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This study was a retrospective cohort study that used data from three clinical databases: the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV), the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) and the clinical data repository from Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China. The MIMIC-IV (version 2.2) is a large, single-centre public database containing unidentified patient data from all ICU centres and emergency departments at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA, USA) from 2008 to 2019 [27]. Similarly, the eICU-CRD (version 2.0) is a freely accessible multicentre critical care research database that encompasses data on >200 000 patients from 335 ICU centres across 208 hospitals in the USA between 2014 and 2015 [28]. The MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD are both critical care databases, and the eICU-CRD was constructed following the MIMIC-IV and expanded the scope of research by including data from multiple healthcare institutions. Therefore, AP-AKI patients from these two databases might be homogeneous. To increase the statistical power for model development, AP-AKI patients from these two databases were combined to constitute the training set. AP-AKI patients from the ICU of Xiangya Hospital (January 2013–February 2023) were regarded as the external validation set. Xiangya Hospital is a nationally administered tertiary Grade A comprehensive hospital under the supervision of the National Health Commission of China.

To access the databases of MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD, the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative courses were completed (record ID: 58637411). The MIMIC-IV was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA, USA). Ethical approval for the eICU-CRD was not applicable because it was released under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Safe Harbor provision. The external validation set was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital (protocol 202403060). Due to the unidentified nature of the protected patient information in this study, written informed consent was not required. The study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement [29].

Individuals who met the following criteria were included: a clinical diagnosis of AP and AKI and admission to the ICU. Individuals who met the following criteria were excluded: age <18 years, had an ICU stay of ≤24 hours and ≥25% missing data or outcome variable missing. For those with multiple admissions, only the first ICU admission was included in this study.

Data collection

Data on demographic characteristics, laboratory indicators, vital signs, comorbidities and treatment requirements within the initial 24 hours following ICU admission were retrieved from three databases and were considered as potential predictors. Demographic characteristics included age, ethnicity and sex. Laboratory indicators included white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, haemoglobin level, platelet count, haematocrit, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, eosinophil count, basophil count, monocyte count, percentage of neutrophils (NEUT%), percentage of lymphocytes (LYMPH%), percentage of eosinophils (EO%), percentage of basophils (BAS%), percentage of monocytes (MONO%), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), SCr, albumin level, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, alanine transaminase (ALT) level, blood glucose (BG) level, potassium level, sodium level, chloride level, calcium level, phosphorus level, prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and APTT. Vital signs included temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Comorbidities included coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypertriglyceridaemia, malignancy, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and sepsis. Treatment requirements included RRT, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid administration, diuretic administration and vasopressor administration.

The outcome variable of this study was in-hospital mortality, and relevant data were extracted from three databases. Due to the special social and cultural background in China, in-hospital mortality of the external validation set was defined as both mortality during the hospital and within 24 hours of discharge [30, 31].

Statistical analysis

For normally distributed and homoscedastic continuous data, statistical descriptions were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and group differences were compared using the Student's t-test. Skewed data were described using median and interquartile range (IQR), with group differences assessed using the rank sum test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and group comparisons were conducted using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Missing values were imputed using the multiple imputation method by generating five datasets. Specifically, categorical missing values were combined using the mode of the generated data and continuous missing values were combined using the mean of the generated data as appropriate. P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Model development

The training set included data from the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD. Multicollinearity of variables with statistical significance by between-group comparisons was assessed by the variance inflation factor (VIF), with a VIF value >5 considered to exhibit multicollinearity. The variable with the highest VIF was removed first, followed by recalculating the VIF for the remaining variables. This process was repeated until all variables had a VIF value <5. The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) algorithm was used for feature selection to identify the optimal subset. In each iteration, the least important feature was removed and the model was rebuilt. This process was repeated until the optimal feature subset was found. Finally, the optimal subset was selected as the predictors for the model.

For the XGBoost model, grid search was used and the model parameters were constantly tuned [32, 33], and for the RF model, the parameters were tuned one by one [34, 35]. To address the issue of class imbalance (death/survival), random oversampling was employed. Ten-fold cross-validation was used to develop the LR and ML models based on the selected predictors to predict in-hospital mortality rate among AP-AKI patients.

Model evaluation and validation

The external validation set included data from the ICU of Xiangya Hospital. The discrimination of the predictive models in the training and external validation sets were assessed by the area under the curve (AUC), Youden index, accuracy (ACC), sensitivity, specificity, F1 score, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). An AUC value of 0.7–0.8 and >0.8 is considered acceptable and satisfactory, respectively [36]. The Delong's tests were used to compare whether the differences in the AUC values across different models were statistically significant and Bonferroni's corrections were used for multiple comparisons. The models’ calibration was evaluated by the calibration curves and Brier scores. The Brier score ranges from 0.00 to 1.00, with closer to 0.00 representing better calibration.

For the predictive model with the highest performance in the training set, a variable importance ranking plot was generated to identify the most influential features. The Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method, which is based on the Shapley value principle from game theory and analyses the contribution and contribution direction of each feature to the model's prediction, was employed to provide further explanation. The generalizability of the predictive model was evaluated based on the findings of the external validation set.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

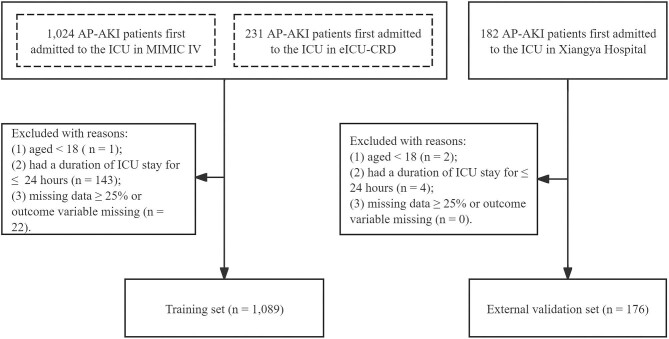

A total of 1089 eligible records with AP-AKI were extracted from the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD and a total of 176 eligible AP-AKI patients from Xiangya Hospital were included in this study (Fig. 1). Thus the training and external validation sets consist of 1089 and 176 individuals, respectively. The in-hospital mortality rate of the training and external validation sets was 13.77% and 54.55%, respectively.

Figure 1:

Flow chart of the study population.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the training and external validation sets. The patients in the training and external validation sets were ages 61.47 years (IQR 49.23–73.65) and 53.91 years (SD 1.12), respectively. Additionally, the proportion of females in the training and external validation sets was 45.27% and 24.43%, respectively. Additionally, the training and external validation sets differed significantly in laboratory indicators, including RBC, haemoglobin, platelet, haematocrit, lymphocytes, eosinophils, basophils, NEUT%, LYMPH%, EO%, RDW, BUN, SCr, AST, ALT, BG, sodium, calcium, INR and APTT; vital signs, including temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate and DBP; comorbidities, including coronary heart disease, hypertension, hypertriglyceridaemia, malignancy and chronic pulmonary disease; and treatment requirements, including RRT, mechanical ventilation and glucocorticoids (all P < .05).

Table 1:

Characteristics of the training and external validation sets.

| Characteristics | Training set (n = 1089) | External validation set (n = 176) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 61.47 (49.23–73.65) | 53.91 ± 1.12 | <.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 493 (45.27) | 43 (24.43) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| White | 745 (68.41) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Black | 130 (11.94) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Asian | 30 (2.75) | 176 (100.00) | |

| Hispanic | 42 (3.86) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Other/unknown | 142 (13.04) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Laboratory indicators | |||

| WBC (×109/l) | 12.30 (8.40–18.10) | 13.15 (8.53–17.50) | .572 |

| RBC (×1012/l) | 3.74 (3.13–4.35) | 3.00 (2.49–3.91) | <.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.20 (9.40–13.10) | 9.25 (7.60–11.60) | <.001 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 196.00 (133.00–279.00) | 151.50 (105.75–213.00) | <.001 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 34.54 ± 0.24 | 27.85 (23.08–35.08) | <.001 |

| Neutrophil (×109/l) | 10.04 (6.51–15.07) | 11.20 (6.90–16.10) | .218 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/l) | 0.99 (0.63–1.56) | 0.80 (0.50–1.28) | <.001 |

| Eosinophil (×109/l) | 0.06 (0.01–0.14) | 0.00 (0.00–0.10) | <.001 |

| Basophil (×109/l) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) | 0.00 (0.00–0.04) | <.001 |

| Monocyte (×109/l) | 0.56 (0.34–0.94) | 0.60 (0.30–1.08) | .186 |

| NEUT% | 81.44 (74.67–87.40) | 86.15 (81.6–91.05) | <.001 |

| LYMPH% | 9.00 (5.00–14.00) | 6.70 (3.93–10.80) | <.001 |

| EO% | 0.50 (0.10–1.10) | 0.20 (0.10–0.80) | <.001 |

| BAS% | 0.20 (0.04–0.40) | 0.20 (0.10–0.40) | .092 |

| MONO% | 5.00 (3.00–7.00) | 5.10 (3.20–7.88) | .104 |

| MCV (fl) | 92.00 (87.65–98.00) | 91.65 (89.60–95.78) | .999 |

| MCH (PG) | 30.50 (28.80–32.10) | 30.50 (29.40–31.50) | .737 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 33.00 (31.90–34.00) | 33.10 (32.12–33.84) | .236 |

| RDW (%) | 14.90 (13.80–16.50) | 14.60 (13.90–15.70) | .011 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 23.00 (14.00–39.00) | 43.54 (28.39–70.60) | <.001 |

| SCr (µmol/l) | 106.08 (70.72–193.15) | 255.70 (141.68–414.10) | <.001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.00 (2.50–3.50) | 2.92 ± 0.03 | .072 |

| AST (U/l) | 67.00 (33.00–156.50) | 55.40 (30.10–109.15) | .023 |

| ALT (U/l) | 46.00 (23.00–119.50) | 26.35 (14.25–64.25) | <.001 |

| BG (mmol/l) | 7.50 (5.86–10.50) | 10.20 (7.38–13.28) | <.001 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 4.10 (3.70–4.70) | 4.05 (3.76–4.76) | .912 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 138.00 (134.00–141.00) | 142.21 ± 0.53 | <.001 |

| Chlorine (mmol/l) | 103.00 (99.00–108.00) | 103.05 ± 0.56 | .953 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.03 (1.85–2.18) | 1.97 (1.76–2.10) | <.001 |

| Phosphorus(mmol/l) | 1.13 (0.87–1.45) | 1.04 (0.66–1.52) | .072 |

| PT (s) | 14.70 (12.90–17.70) | 15.30 (13.70–17.10) | .161 |

| INR | 1.30 (1.10–1.60) | 1.26 (1.14–1.42) | .007 |

| APTT (s) | 31.00 (27.48–38.50) | 38.25 (33.05–46.00) | <.001 |

| Vital signs | |||

| Temperature (°C) | 36.78 (36.44–37.22) | 37.00 (36.60–38.00) | <.001 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 20 (17–25) | 23 (20–30) | <.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 97 (83–114) | 114.93 ± 1.60 | <.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 123 (105–144) | 126.16 ± 1.96 | .599 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 68 (57–82) | 74 (64–83) | .015 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Coronary heart disease | 219 (20.11) | 17 (9.66) | .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 341 (31.31) | 48 (27.27) | .281 |

| Hypertension | 587 (53.90) | 48 (27.27) | <.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 249 (22.87) | 85 (48.30) | <.001 |

| Malignancy | 101 (9.27) | 4 (2.27) | .002 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 219 (20.11) | 6 (3.41) | <.001 |

| CKD | 214 (19.65) | 30 (17.05) | .416 |

| Sepsis | 558 (51.24) | 93 (52.84) | .693 |

| Treatment requirements, n (%) | |||

| RRT | 150 (13.77) | 57 (32.39) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 351 (32.23) | 94 (53.41) | <.001 |

| Glucocorticoid | 191 (17.54) | 15 (8.52) | .003 |

| Diuretic | 238 (21.85) | 43 (24.43) | .445 |

| Vasopressor | 384 (35.26) | 56 (31.82) | .373 |

| Outcome variable, n (%) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | 150 (13.77) | 96 (54.55) | <.001 |

Values are presented as median (IQR) or mean ± SD unless stated otherwise.

Predictor selection

The final optimal subset of features identified eight variables: age, neutrophils, RDW, BUN, albumin, SBP, RRT and vasopressor. These eight variables were considered as the predictors for developing the in-hospital mortality predictive models.

Model development

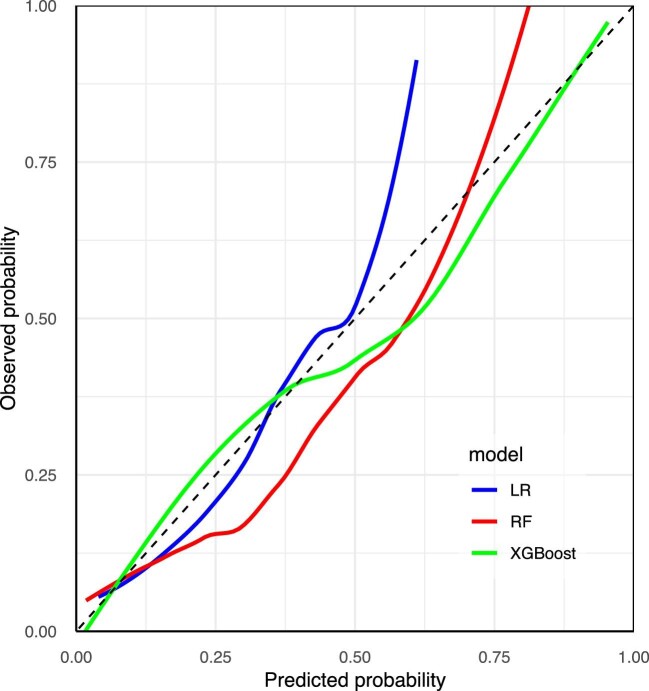

Table 2 shows the results for the discrimination of the LR, RF, and XGBoost models in the training set. Compared with the AUC values of the LR model [0.788 (95% CI 0.767–0.808)] and the RF model [0.894 (95% CI 0.880–0.908)], the AUC value of the XGBoost model [0.941 (95% CI 0.931–0.952)] was significantly higher (both P < .001) in the training set (Fig. 2).

Table 2:

Discrimination indicators of the predictive models in the training and external validation sets.

| Models | AUC (95% CI) | Youden index | ACC (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1 score | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | ||||||||

| LR | 0.788 (0.767–0.808) | 0.45 | 72.42 | 64.64 | 80.19 | 0.70 | 76.54 | 69.40 |

| XGBoost | 0.941 (0.931–0.952) | 0.75 | 87.49 | 93.50 | 81.47 | 0.88 | 83.46 | 92.62 |

| RF | 0.894 (0.880–0.908) | 0.61 | 80.51 | 85.62 | 75.40 | 0.81 | 77.68 | 83.99 |

| External validation set | ||||||||

| LR | 0.691 (0.613–0.769) | 0.23 | 59.66 | 40.62 | 82.50 | 0.52 | 73.58 | 53.66 |

| XGBoost | 0.724 (0.648–0.800) | 0.19 | 56.82 | 32.29 | 86.25 | 0.45 | 73.81 | 51.49 |

| RF | 0.677 (0.599–0.756) | 0.23 | 59.66 | 42.71 | 80.00 | 0.54 | 71.93 | 53.78 |

Figure 2:

The receiver operating characteristics curves of the training set.

Figure 3 shows the calibration curves of the established models in the training set. The Brier scores of the LR, RF and XGBoost models were 0.099, 0.066 and 0.039, respectively. Figure 4 shows the feature importance rankings in the XGBoost model and Fig. 5 shows the importance of each feature based on its SHAP values.

Figure 3:

The calibration curves of the training set.

Figure 4:

The feature importance rankings in the XGBoost model of the training set.

Figure 5:

The importance of each feature based on the SHAP values of the training set. Each line in the y-axis represents a feature and the x-axis represents the SHAP value of the feature. Each dot represents a participant and the feature value is indicated by the colour, with red indicating a higher value and blue indicating a lower value. The positive associations between the feature and SHAP values suggest risk factors of in-hospital mortality rate, whereas the negative associations suggest protective factors of in-hospital mortality rate.

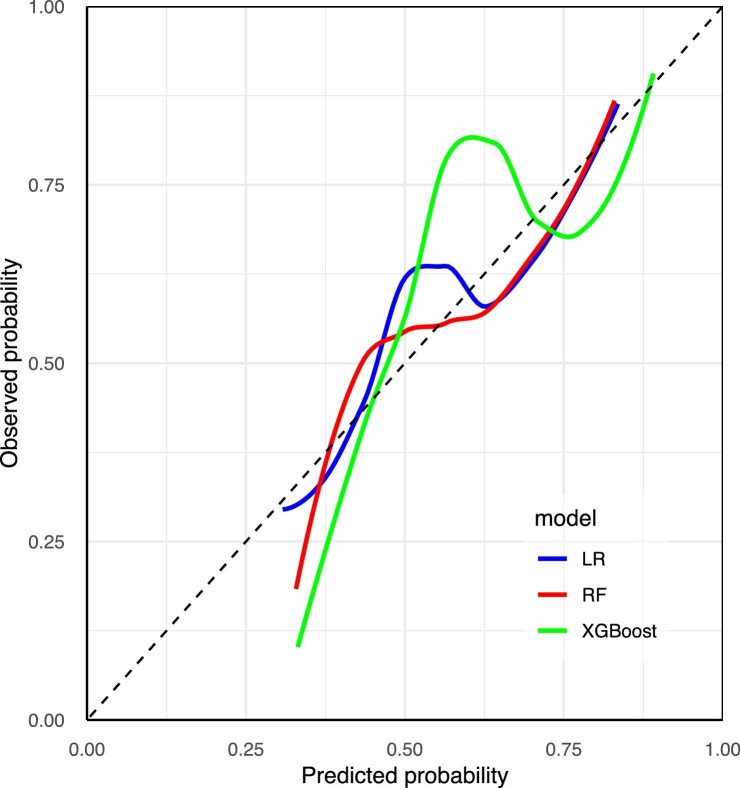

Model validation

The results for the discrimination of the LR, RF and XGBoost models in the external validation set are also shown in Table 2. The performance of the XGBoost model was acceptable, with an AUC value of 0.724 (95% CI 0.648–0.800). However, it did not differ significantly from the LR (P = .898) and RF models (P = .206) in the external validation set (Fig. 6). Figure 7 shows the calibration curves of the established models in the external validation set. The Brier scores of the LR, RF and XGBoost models were 0.221, 0.224 and 0.217, respectively.

Figure 6:

The receiver operating characteristics curves of the external validation set.

Figure 7:

The calibration curves of the external validation set.

DISCUSSION

This study developed two ML-based predictive models for in-hospital mortality rate in critically ill patients with AP-AKI using eight predictors by comparing their performance with the traditional LR model in a training set with a large sample size. This study found that the XGBoost model was superior to the other two models for both discrimination and calibration. The finding was further validated using an external cohort with a limited sample size, and a similar tendency was observed in the external validation set. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop ML-based models to predict in-hospital mortality rate of critically ill patients with AP-AKI.

XGBoost is a gradient boosting tree algorithm that leverages efficient algorithms and optimization techniques to construct powerful and efficient ML models. Consequently, the XGBoost model offers several advantages, including high accuracy and scalability, making it suitable for a wide range of regression and classification problems. The majority of prior work on comparing the performance between the XGBoost and traditional LR models showed the superiority of the XGBoost model, especially in clinical prediction [37, 38]. For instance, in a study on ML for predicting AKI in sepsis patients, the XGBoost model exhibited the best predictive performance among nine models in terms of discrimination, calibration and clinical applicability [38]. Similarly, in another study predicting 28-day mortality rate in sepsis-associated AKI patients, the XGBoost model outperformed traditional scoring systems and other ML models, demonstrating superior predictive performance [16]. Consistently, this study found that the XGBoost model was superior to the LR and RF models for both discrimination and calibration in the training set. Therefore, it is suggested to use the XGBoost model for better prediction of in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with AP-AKI in clinical practice.

This study identified eight predictors—age, neutrophils, RDW, BUN, albumin, SBP, RRT and vasopressor—to develop the in-hospital mortality predictive models. Previous studies have indicated the role of age in predicting mortality among patients with severe illnesses [18, 25, 39, 40]. The association of advanced age with increased mortality rate can be attributed to age-related physiological decline, such as decreased immune function and organ dysfunction [41–43]. Therefore, AP-AKI patients with advanced age should be given special attention to reduce the mortality rate.

The predictive value of RDW and serum albumin concentration in predicting in-hospital mortality has been indicated in previous studies of critically ill patients [44–52]. Its underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated and it has become evident that RDW may be a non-specific parameter to provide effective risk stratification for patients with severe illnesses [44]. The neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a marker of inflammation and physiological stress. The NLR is strongly correlated with early onset, progression and recovery in AKI, as well as the in-hospital and post-discharge mortality rates of these patients [53]. For example, a study found that high NLRs were associated with an increased risk of 30-day and 90-day mortality in AKI patients [54]. Additionally, BUN is an important blood test indicator of kidney function. A previous study found that the BUN:creatinine ratio was useful for risk stratification of AKI [55]. Another study indicated that the BUN:serum albumin ratio was a promising and easily obtainable biomarker that can serve as a prognostic predictor for AKI and in-hospital mortality in ICU patients with intracerebral haemorrhage [56]. Consistently, this study found similar results, indicating the possible value of neutrophils, RDW, BUN and albumin as indicators of in-hospital mortality rate in critically ill patients with AP-AKI.

In terms of vital sign measurements, a previous study found that patients with an SBP of 180–199 mmHg have a decreased risk of developing AKI compared with those with an SBP <180 mmHg [57]. Similarly, this study found protective effects of high SBP against in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with AP-AKI. Additionally, this study found that treatment requirements of RRT and vasopressor were predictors for in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with AP-AKI, which was consistent with previous studies in numerous populations and could be explained by the fact that those treated with RRT or vasopressor were more critical compared with their counterparts [13, 25, 31, 58]. Therefore, more medical resources should be allocated to those treated with RRT or vasopressor in the context of limited medical resources for critically ill patients with AP-AKI patients.

The strengths of this study included the retrospective cohort design with multiple ICU centres, the large sample size of the training set, the comprehensive assessment of possible predictors and the external validation of the established models, which significantly added credibility when interpreting relevant findings. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study used data from established databases. Therefore, the predictive value of factors that were not recorded was unknown. For example, the aetiology of pancreatitis, which was not considered in this study, may be associated with the in-hospital mortality of critically ill patients with AP-AKI. Similarly, this study considered factors collected within the initial 24 hours following ICU admission exclusively. Therefore, the predictive value of factors collected out of this time frame need to be further explored. Furthermore, the characteristics of the study population, the in-hospital mortality rate and the sample size of the external validation set varied greatly from the training set, which may affect the performance of the predictive models in the external validation set, although a similar tendency was observed. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings of the training set remains an issue and future validation is still needed.

CONCLUSIONS

The XGBoost model was superior to the LR and RF models in terms of both the discrimination and calibration in the training set with data from the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD, and eight predictors (age, neutrophil, RDW, BUN, albumin, SBP, RRT and vasopressor) were identified. However, due to the differences in the characteristics of the study population, the in-hospital mortality rate and the sample size between the training and external validation sets, the generalizability of the findings of the training set remains an issue and future validation is still needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Database-IV and the eICU Collaborative Research Database for sharing a large amount of data.

Contributor Information

Yamin Liu, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Xu Zhu, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, College of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Jing Xue, Department of Scientific Research, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Rehanguli Maimaitituerxun, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Wenhang Chen, Department of Nephrology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Wenjie Dai, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ40972).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.L. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, data acquisition and management, formal analysis, visualization, writing the original draft and review and editing. X.Z. was responsible for methodology, data acquisition and management, review and editing and validation. J.X. and R.M. were responsible for data acquisition and management, review and editing and validation. W.C. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, review and editing, supervision, formal analysis and validation, funding acquisition and project administration. W.D. was responsible for methodology, review and editing, supervision, formal analysis and validation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2021. Gastroenterology 2022;162:621–44. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lankisch PG, Apte M, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet 2015;386:85–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60649-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA et al. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet 2020;396:726–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31310-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Devani K, Charilaou P, Radadiya D et al. Acute pancreatitis: trends in outcomes and the role of acute kidney injury in mortality – a propensity-matched analysis. Pancreatology 2018;18:870–7. 10.1016/j.pan.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krishna SG, Kamboj AK, Hart PA et al. The changing epidemiology of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations: a decade of trends and the impact of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 2017;46:482–8. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamada S, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T. Management of acute pancreatitis in Japan: analysis of nationwide epidemiological survey. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:6335–44. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Song K, Wu Z, Meng J et al. Hypertriglyceridemia as a risk factor for complications of acute pancreatitis and the development of a severity prediction model. HPB 2023;25:1065–73. 10.1016/j.hpb.2023.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wajda J, Dumnicka P, Maraj M et al. Potential prognostic markers of acute kidney injury in the early phase of acute pancreatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3714. 10.3390/ijms20153714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang HL, Nie X, Cai B et al. Procalcitonin levels predict acute kidney injury and prognosis in acute pancreatitis: a prospective study. PLoS One 2013;8:e82250. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petejova N, Martinek A. Acute kidney injury following acute pancreatitis: a review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2013;157:105–13. 10.5507/bp.2013.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu S, Zhou Q, Cai Y et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for the early occurrence of acute kidney injury in patients with acute pancreatitis. Ren Fail 2023;45:2194436. 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2194436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nassar TI, Qunibi WY. AKI associated with acute pancreatitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:1106–15. 10.2215/CJN.13191118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou J, Li Y, Tang Y et al. Effect of acute kidney injury on mortality and hospital stay in patient with severe acute pancreatitis. Nephrology 2015;20:485–91. 10.1111/nep.12439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zeng Z, Yao S, Zheng J et al. Development and validation of a novel blending machine learning model for hospital mortality prediction in ICU patients with sepsis. BioData Mining 2021;14:40. 10.1186/s13040-021-00276-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luo XQ, Yan P, Duan SB et al. Development and validation of machine learning models for real-time mortality prediction in critically ill patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Front Med 2022;9:853102. 10.3389/fmed.2022.853102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang J, Peng H, Luo Y et al. Explainable ensemble machine learning model for prediction of 28-day mortality risk in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Front Med 2023;10:1165129. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1165129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu C, Zhang Y, Nie S et al. Predicting in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute kidney injury. Nat Commun 2023;14:3739. 10.1038/s41467-023-39474-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tang H, Jin Z, Deng J et al. Development and validation of a deep learning model to predict the survival of patients in ICU. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2022;29:1567–76. 10.1093/jamia/ocac098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou H, Liu L, Zhao Q et al. Machine learning for the prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury during hospitalization. Front Immunol 2023;14:1140755. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1140755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerry S, Bonnici T, Birks J et al. Early warning scores for detecting deterioration in adult hospital patients: systematic review and critical appraisal of methodology. BMJ 2020;369:m1501. 10.1136/bmj.m1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basile-Filho A, Lago AF, Menegueti MG et al. The use of APACHE II, SOFA, SAPS 3, C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, and lactate to predict mortality of surgical critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16204. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hou N, Li M, He L et al. Predicting 30-days mortality for MIMIC-III patients with sepsis-3: a machine learning approach using XGboost. J Transl Med 2020;18:462. 10.1186/s12967-020-02620-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhuang J, Huang H, Jiang S et al. A generalizable and interpretable model for mortality risk stratification of sepsis patients in intensive care unit. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2023;23:185. 10.1186/s12911-023-02279-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu P, Li Y, Liu Y et al. Comparison of conventional logistic regression and machine learning methods for predicting delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a multicentric observational cohort study. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:857521. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.857521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Selvanathan DK, Johnson PG, Thanikachalam DK et al. Acute kidney injury complicating severe acute pancreatitis: clinical profile and factors predicting mortality. Indian J Nephrol 2022;32:460–6. 10.4103/ijn.IJN_476_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tran DD, Oe PL, de Fijter CW et al. Acute renal failure in patients with acute pancreatitis: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1993;8:1079–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data 2023;10:1. 10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pollard TJ, Johnson AEW, Raffa JD et al. The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci Data 2018;5:180178. 10.1038/sdata.2018.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015;350:g7594. 10.1136/bmj.g7594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu J, Jin JW, Lin N et al. Prognostic analysis of 558 emergency tracheal intubation patients. World J Clin Med 2023;2:37–42. 10.57237/j.wjcm.2023.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fang J, Chen Q, Chen C et al. Effect of early continuous renal replacement therapy on in-hospital mortality of patients with sepsis. Chin J Emerg Med 2023;32:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Y, Xu Y, Ma Z et al. An XGBoost-based model for assessment of aortic stiffness from wrist photoplethysmogram. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2022;226:107128. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noorunnahar M, Chowdhury AH, Mila FA. A tree based eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) machine learning model to forecast the annual rice production in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2023;18:e0283452. 10.1371/journal.pone.0283452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thapelo TS, Mpoeleng D, Hillhouse G. Informed random forest to model associations of epidemiological priors, government policies, and public mobility. MDM Policy Pract 2023;8:23814683231218716. 10.1177/23814683231218716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu J, Zhou Z, Kong S et al. Application of random forest based on semi-automatic parameter adjustment for optimization of anti-breast cancer drugs. Front Oncol 2022;12:956705. 10.3389/fonc.2022.956705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang D, Zhao L, Kang J et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for acute kidney injury in patients with moderately severe and severe acute pancreatitis. Clin Exp Nephrol 2022;26:770–87. 10.1007/s10157-022-02219-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Z, Ho KM, Hong Y. Machine learning for the prediction of volume responsiveness in patients with oliguric acute kidney injury in critical care. Crit Care 2019;23:112. 10.1186/s13054-019-2411-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yue S, Li S, Huang X et al. Machine learning for the prediction of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. J Transl Med 2022;20:215. 10.1186/s12967-022-03364-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020;55:2000524. 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramazani J, Hosseini M. Prediction of mortality in the medical intensive care unit with serial full outline of unresponsiveness score in elderly patients. Indian J Crit Care Med 2022;26:94–9. 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li C, Hu S, Yu C. All-cause and cancer mortality trends in Macheng, China (1984–2013): an age-period-cohort analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2068. 10.3390/ijerph15102068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fantacone ML, Lowry MB, Uesugi SL et al. The effect of a multivitamin and mineral supplement on immune function in healthy older adults: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients 2020;12:2447. 10.3390/nu12082447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S et al. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age—a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1431. 10.1186/s12889-019-7762-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hong J, Hu X, Liu W et al. Impact of red cell distribution width and red cell distribution width/albumin ratio on all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and foot ulcers: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022;21:91. 10.1186/s12933-022-01534-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karampitsakos T, Torrisi S, Antoniou K et al. Increased monocyte count and red cell distribution width as prognostic biomarkers in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2021;22:140. 10.1186/s12931-021-01725-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zou Z, Zhuang Y, Liu L et al. Role of elevated red cell distribution width on acute kidney injury patients after cardiac surgery. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2018;18:166. 10.1186/s12872-018-0903-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu J, Huang L, He H et al. Red cell distribution width to platelet ratio is associated with increasing in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Dis Markers 2022;2022:4802702. 10.1155/2022/4802702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang RR, He M, Ou XF et al. The predictive value of RDW in AKI and mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury. Clin Lab Anal 2020;34:e23373. 10.1002/jcla.23373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang B, Lu H, Gong Y et al. The association between red blood cell distribution width and mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:9658216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jia L, Cui S, Yang J et al. Red blood cell distribution width predicts long-term mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a retrospective database study. Sci Rep 2020;10:4563. 10.1038/s41598-020-61516-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hu Y, Liu H, Fu S et al. Red blood cell distribution width is an independent predictor of AKI and mortality in patients in the coronary care unit. Kidney Blood Press Res 2017;42:1193–204. 10.1159/000485866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cai N, Jiang M, Wu C et al. Red cell distribution width at admission predicts the frequency of acute kidney injury and 28-day mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Shock 2022;57:370–7. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schiffl H, Lang SM. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio-a new diagnostic and prognostic marker of acute kidney injury. Barriers to broad clinical application. Int Urol Nephrol 2023;55:101–6. 10.1007/s11255-022-03297-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fan LL, Wang YJ, Nan CJ et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is associated with all-cause mortality among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin Chim Acta 2019;490:207–13. 10.1016/j.cca.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takaya Y, Yoshihara F, Yokoyama H et al. Risk stratification of acute kidney injury using the blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circ J 2015;79:1520–5. 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang F, Wang R, Lu W et al. Prognostic value of blood urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio for acute kidney injury and in-hospital mortality in intensive care unit patients with intracerebral haemorrhage: a retrospective cohort study using the MIMIC-IV database. BMJ Open 2023;13:e069503. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qureshi AI, Huang W, Lobanova I et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction and acute kidney injury in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2020;51:3030–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Keying Q. Factors associated with early mortality in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. Jilin Med Coll 2022;43:1658–60. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.