Abstract

Background

Parturition is an inflammation process. Exaggerated inflammatory reactions in infection lead to preterm birth. Although nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) has been recognized as a classical transcription factor mediating inflammatory reactions, those mediated by NF-κB per se are relatively short-lived. Therefore, there may be other transcription factors involved to sustain NF-κB-initiated inflammatory reactions in gestational tissues in infection-induced preterm birth.

Methods

Cebpd-deficient mice were generated to investigate the role of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein δ (C/EBPδ) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced preterm birth, and the contribution of fetal and maternal C/EBPδ was further dissected by transferring Cebpd−/− or WT embryos to Cebpd−/− or WT dams. The effects of C/EBPδ pertinent to parturition were investigated in mouse and human myometrial and amnion cells. The interplay between C/EBPδ and NF-κB was examined in cultured human amnion fibroblasts.

Results

The mouse study showed that LPS-induced preterm birth was delayed by Cebpd deficiency in either the fetus or the dam, with further delay being observed in conceptions where both the dam and the fetus were deficient in Cebpd. Mouse and human studies showed that the abundance of C/EBPδ was significantly increased in the myometrium and fetal membranes in infection-induced preterm birth. Furthermore, C/EBPδ participated in LPS-induced upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as genes pertinent to myometrial contractility and fetal membrane activation in the myometrium and amnion respectively. A mechanistic study in human amnion fibroblasts showed that C/EBPδ, upon induction by NF-κB, could serve as a supplementary transcription factor to NF-κB to sustain the expression of genes pertinent to parturition.

Conclusions

C/EBPδ is a transcription factor to sustain the expression of gene initiated by NF-κB in the myometrium and fetal membranes in infection-induced preterm birth. Targeting C/EBPδ may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of infection-induced preterm birth.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-024-03650-2.

Keywords: C/EBPδ, Inflammation, Preterm birth, Parturition, Myometrium, Fetal membranes, NF-κB

Background

Preterm birth (delivery before 37 weeks gestation), which occurs in approximately 5% to 18% of all pregnancies worldwide, is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in newborns and children under 5 years of age [1, 2]. Although a number of factors are known to underlie preterm birth, microbe-induced intrauterine inflammation is considered to be the most common and recognized cause, accounting for at least 25–40% of all preterm deliveries [3–5].

Ascending microbes (predominantly bacteria) from the lower genital tract and their products (e.g., lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria) can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors [6], such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), in the gestational tissues including fetal membranes/placenta and maternal uterus/decidua, thereby activating intracellular pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and infiltration of immune cells, resulting in increased expression of genes pertinent to parturition. These genes are involved in the activation of the crucial events associated with labor onset, including myometrial contraction, membrane activation, and cervical ripening [7–11]. Therefore, elucidating the mechanism underlying infection-induced inflammatory reactions in gestational tissues is of paramount importance for the development of effective therapeutic strategies to prevent infection-induced preterm birth.

Although nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) has been recognized as a major classical pro-inflammatory transcription factor mediating the expression of a wide array of pro-inflammatory mediators in inflammatory reactions [12, 13], emerging evidence indicates that a complex network of negative feedback loops exists to terminate NF-κB-stimulated inflammatory reactions by inducing the expression of NF-κB inhibitory protein IκBs [14–17] However, the feedforward process of parturition, including infection-induced preterm birth, is essentially a process of persistent inflammation of the gestational tissues, indicating that there should be a supplementary mechanism to the dominant mechanism mediated by NF-κB itself to ensure sustained inflammatory reactions of the gestational tissues in parturition.

The CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family consists of six members with the basic leucine zipper motif, namely C/EBPα, β, δ, γ, ε, and ζ [18–20]. Among them, C/EBPδ is emerging as a crucial transcription factor underlying a number of cellular events including proliferation and differentiation as well as inflammation [19, 21, 22]. Our previous study has demonstrated that C/EBPδ is also engaged in labor onset at term by inducing the expression of a number of crucial genes related to labor onset in the fetal membranes, such as PTGS2, the gene encoding the rate-limiting enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) for prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, and HSD11B1, the gene encoding 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (11β-HSD1) which regenerates biologically active glucocorticoids from their inactive counterparts [23–25]. Interestingly, it has been reported that C/EBPδ, upon induction by inflammatory factors such as LPS and pro-inflammatory cytokines [26–28], can supplement the early but relatively transient inflammatory reactions elicited by NF-κB itself to sustain inflammatory reactions, suggesting that C/EBPδ may act as an extender of NF-κB-mediated acute inflammatory reactions [29–31]. However, it remains unknown whether C/EBPδ participates in the sustained inflammatory reactions in gestational tissues in infection-induced preterm birth. Based on the rationale described above, we hypothesized that in contrast to the relatively short-lived effects induced by NF-κB per se, C/EBPδ, upon induction by NF-κB, might continue the actions of NF-κB in the induction of genes pertinent to inflammation and parturition in gestational tissues in infection-induced preterm birth.

To address this hypothesis, we first investigated the role of C/EBPδ in infection-induced preterm birth by using Cebpd−/− mice. Embryo transfer strategies were then utilized to discriminate the contribution of fetal and maternal C/EBPδ in infection-induced preterm birth. The exact role of C/EBPδ in infection-induced preterm birth was further investigated by using maternal uterine and fetal membrane tissues, cultured maternal myometrial cells, and fetal amnion fibroblasts. Finally, the interplay between C/EBPδ and NF-κB in the regulation of infection-induced inflammation and parturition was examined in cultured human amnion fibroblasts.

Methods

Mouse studies

Intraperitoneal administration of LPS in pregnant mice and observation of pregnancy outcomes

Wide type (WT) or Cebpd deficiency (Cebpd−/−) C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University and housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light–dark cycle. Cebpd−/− mice were generated using a CRISPR/Cas9 system as described in detail in our previous study [24]. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, and carried out under guidelines for animal studies. Ten- to twelve-week-old female mice were mated with male mice of the same genotype with proven fertility overnight. The presence of a vaginal plug in the morning was counted as gestational age 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). All animals were randomly assigned to experimental or control groups using a random number table prior to the following experiments.

On 16.5 dpc, WT or Cebpd−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with LPS (20 μg/dam; Sigma; St. Louis, MO) or an equal volume of phosphate buffer solution (PBS). Some of the mice were allowed to deliver spontaneously for observation of gestational age, and some were sacrificed 12 h after injection of LPS or PBS for collection of myometrium and fetal membranes. Time to delivery was calculated according to the time from LPS or PBS injection until the birth of the first pup.

Embryo transfer and collection of tissues in the mice

Superovulation was conducted in eight- to ten-week-old WT or Cebpd−/− female mice by intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU (in 100 μL) of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Sansheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) and 5 IU (in 100 μL) of human chorionic gonadotropin (Sansheng Pharmaceutical Co.) for collection of oocytes 15 h later. Oocytes were fertilized in vitro with the sperm obtained from male mice of the same genotype. After fertilization, 2-cell embryos were collected and twenty 2-cell embryos were transferred to WT or Cebpd−/− pseudopregnant mice on 0.5 dpc. About half of them were successfully developed. Pseudopregnant recipient mice were created by mating with vasectomized males of the same genotype overnight, and the appearance of a vaginal plug next morning was used as an indicator of pseudopregnancy. After embryo transfer, weights of the recipient mice were monitored daily, and pregnancy was confirmed by a weight gain of ≥ 2 g by 12.5 dpc. The resulting WT dams carrying WT or Cebpd–/– fetuses and Cebpd–/– dams carrying WT or Cebpd–/– fetuses were examined to determine time to parturition following intraperitoneal administration of LPS or vehicle as described above. For tissue collection, pregnant mice were euthanized 12 h after LPS injection, and surgery was performed to collect uterus and fetal membranes. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for total RNA and protein extraction or embedded in paraffin after fixing in 10% formalin for immunohistochemical staining.

Extraction of total RNA from mouse tissues and analysis with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qrt-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the fetal membranes and myometrium using a total RNA isolation Kit (Foregene, Chengdu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After examination of RNA concentration and quality using a Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific), reverse transcription was carried out using a Prime-Script RT Master Mix Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The expression of Cebpd, Ptgs2, Oxtr, Ptgfr, Gja1, Il1b, Il6, and Hsd11b1 mRNA was determined with qRT-PCR using the reverse-transcribed cDNA and power SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa). The housekeeping gene Actb (β-actin) was amplified in parallel as an internal loading control. The relative mRNA abundance was quantitated using the 2−△△Ct method, which was normalized to Actb, and then the fold change of each sample relative to one of the control was used for analysis. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Extraction of protein from mouse tissues and analysis with western blotting

Total cellular protein was extracted from the snap-frozen fetal membranes and myometrium with an ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) containing inhibitors for both protease and phosphatase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). After centrifugation and determination of protein concentration using the Bradford method, the supernatant was used to measure the abundance of C/EBPδ, COX-2, OXTR, Cx43, FP and 11β-HSD1 with Western blotting. In brief, 30 μg of protein from each sample was electrophoresed in a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel. After transferring to a nitrocellulose membrane blot, the blot was blocked with 5% non-fat milk and incubated with primary antibodies against C/EBPδ, COX-2, OXTR, Cx43, FP, and 11β-HSD1 overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The peroxidase activity was developed with a chemiluminescence detection system (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and visualized using a G-Box chemiluminescence image capture system (Syngene, Cambridge, U.K.). The internal loading control was performed by probing the same blot with an antibody against β-actin. The ratio of target protein band intensities to that of β-actin was used to indicate the target protein abundance. The antibody information is illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Cytokine microarray assay in mouse tissues

Fetal membranes and myometrium collected from WT and Cebpd–/– mice were ground and homogenized with Cell Lysis Buffer without SDS (#EPX-99999–000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected for measurements of cytokines in using the Mouse Th1/Th2 cytokines 11-Plex ProcartaPlex assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cytokines measured with this kit includes GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-18, and TNFα. Plates were read with the Luminex 200 (Luminex, Austin, TX), and cytokine concentrations were calculated using xPONENT version 4.2 (Luminex).

Culture and treatment of primary mouse myometrial cells

Myometrium cells were isolated from uteri obtained from pregnant mice on 16.5 dpc. The intimal surface of the uterus was quickly removed with a sterile gauze after the uterus was dissected from the euthanized pregnant mouse. The remaining myometrial tissue was washed with PBS and cut into 1 cm3 for 2 × digestion with 0.2% collagenase (Sigma) at 37 °C for 20 min to isolate myometrial cells. Cells in the digestion medium were spun down and resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (all from Life Technologies Inc.; Carlsbad, CA) for culture in 75 cm2 culture flasks (Corning Inc., Lowell, MA) at 37 °C in 5% CO2/95% air. This initial culture was designated as passage 0 (p0). When cell growth reached 80–90% confluence, cells were passaged at a ratio of 1:3 and plated into a new 75 cm2 culture flask, designated as passage 1 (p1). The purity of myometrium cells was determined with immunofluorescence staining for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), which showed > 95% cells expressing α-SMA (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). For cell treatments, the cells were plated into a 6-well culture plate (Corning Inc.) at 1 × 106 cells/well. Cells of passages 2–5 were used for all experiments. To investigate the effect of LPS on the expression of Cebpd, Il1b, Il6, Ptgs2, Gja1, Ptgfr, and Oxtr mRNA, cells were treated with LPS (1, 10 and 50 ng/mL; Sigma) for 12 h. To examine the role of C/EBPδ in the mediation of LPS-induced effects, the cells were treated with LPS (50 ng/mL; 12 h) in the presence or absence of siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD as described below. After treatments, total RNA and cellular protein were extracted for the determination of Cebpd, Il1b, Il6, Ptgs2, Gja1, Ptgfr, and Oxtr mRNA abundance with qRT-PCR with primers illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1 and for the determination of C/EBPδ, COX-2, OXTR, Cx43, and FP protein abundance with Western blotting with antibodies illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S2. The culture medium was collected for the measurement of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) concentrations with mouse IL-1β and IL-6 ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kits (both from Abclonal, Wuhan, China) according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer. Methods of RNA and protein extraction, qRT-PCR, and Western blotting in myometrial cells were the same as the methods described in the tissue section. The abundance of target mRNA and protein was normalized to ACTB or β-actin, and then the fold change of each sample relative to the untreated control was used for analysis.

Transfection of sirna in mouse myometrial cells with electroporation

To study the role of the C/EBPδ in the mediation of LPS-induced effects, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD was performed. Briefly, after isolation, the mouse myometrial cells were transfected with 50 nM of siRNA against Cebpd (5′-CUCUUCAACAGCAACCACATT-3′) (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) in Opti-MEM (Life Technologies Inc.) using an electroporator (Nepa Gene, Chiba, Japan) at 165 V for 5 ms. Due to the short coding sequence of the mouse Cebpd gene, only a pair of small interfering RNAs could be designed in this study. Randomly scrambled siRNA served as control. After transfection, the myometrial cells were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics for 72 h before LPS treatment. The knockdown efficiency was assessed with qRT-PCR and Western blotting, shown in the corresponding figures.

Mouse myometrial cell contraction assay

Collagen gel contraction assay was used for evaluating the contraction of mouse myometrial cells after LPS treatment in the presence or absence of Cebpd knock-down. Briefly, collagen solution was prepared from rat tail type 1 collagen (Life Technologies Inc.) and mixed with myometrial cells with or without prior siRNA-mediated knock-down of Cebpd. This cell-collagen mixture (1:4; 1 mL) was added to each well of a 12-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C to allow gel formation after which DMEM containing 10% FBS was layered over the cell-collagen matrix overnight. LPS (50 ng/mL) or vehicle was then added to the medium to incubate for another 12 h. Afterwards, oxytocin (10 nM; 6 h) was added to stimulate myometrial cell contraction. The gel areas of each group were recorded with a camera, and the area (cm2) was measured using the ImageJ software. A decrease or an increase in gel area correlates with an increase or a decrease in contractility respectively [32].

Human studies

Collection and processing of human myometrial tissue and fetal membranes

Human myometrial tissue and fetal membranes were obtained from uncomplicated pregnancies with written informed consent under a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (approval code: RA-2022–172). Twin pregnancy and pregnancies with complications such as preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and gestational diabetes were excluded from this study. The detailed information of recruited pregnant women is listed in Additional file 1: Table S3 and S4. Detailed collection procedures and processing of human myometrial tissue and fetal membranes are described as follows.

Human myometrial tissue was biopsied at the upper margin of the lower uterine segment incision at elective cesarean section without labor at term (designated as term non-labor, TNL), which were placed immediately in sterile cold PBS containing antibiotics (Life Technologies Inc.), and transported to the laboratory for cell isolation. The methods of cell isolation and treatments, determination of mRNA and protein levels, and contraction in human myometrial cells were the same as described in the mouse studies except that primers and antibodies used for qRT-PCR and Westering blotting were against human counterparts as illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1 and S2 respectively.

Human fetal membranes were collected from TNL, term pregnancies with spontaneous labor (designated as term labor, TL), preterm pregnancies terminated by elective cesarean section without labor for maternal or fetal conditions including placenta previa, vasa previa, and fetal distress (designated as preterm non-labor, PNL), and preterm labor with infection (designated as preterm labor, PL). The amnion layer was peeled off the fetal membranes immediately after delivery. For determination of C/EBPδ mRNA and protein abundance in the amnion tissue of TNL, TL, PNL, and PL groups with qRT-PCR and Western blotting, the amnion tissue was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA and protein extraction. The methods of RNA and protein extraction, qRT-PCR and Western blotting were the same as described in the mouse studies except that primers and antibodies for qRT-PCR and Western blotting were against human counterparts as illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1 and S2 respectively. For amnion fibroblast isolation, the amnion tissue obtained from TNL was placed in sterile cold PBS containing antibiotics (Life Technologies Inc.) and transported to the laboratory for cell isolation as described below.

Culture and treatment of primary human amnion fibroblasts

The amnion tissue from TNL was digested twice with 0.125% trypsin (Life Technologies Inc.) for 20 min and then washed thoroughly with PBS to remove epithelial cells. The remaining mesenchymal tissue was further digested with 0.1% collagenase (Sigma) for 20 min to release fibroblasts. The isolated fibroblasts in the digestion medium were then spun down and resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics and cultured in a 6-well culture plate at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well at 37 °C in 5% CO2/95% air. This method of isolation yields high purity of amnion fibroblasts (> 95%), which have been characterized previously with immunofluorescence staining of vimentin and cytokeratin-7, the respective markers for mesenchymal and epithelial cells [33].

Three days after plating, human amnion fibroblasts were treated with the following reagents in FBS-free DMEM. The concentration-dependent effects of LPS on the expression of CEBPD, PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 mRNA were studied by treating the cells with 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL LPS (Sigma) for 12 h. For the time course study of the effect of LPS on the gene expression and p65 phosphorylation, an indicator of NF-κB activation, the cells were treated with LPS (50 ng/mL) for 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 h. To examine the enrichments of p65 and C/EBPδ at PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 gene promoters, the cells were treated with LPS (50 ng/mL) for 2 and 8 h. To investigate the role of C/EBPδ and NF-κB in the induction of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, IL6, and TLR4 by LPS, the cells were treated with LPS (50 ng/mL) for 3 h and 12 h in the presence or absence of p65 antagonist JSH (10 μM; Selleck, Houston, TX) or siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD. Two separate CEBPD-Homo siRNA (5′-CCCUUUGUAUUGUAGAUAATT-3′ and 5′-ACAGCCUGGACUUACCACCACUAAA-3′) (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) were used in this study. Randomly scrambled siRNA served as control. The method of siRNA transfection was the same as described in the mouse cells.

After treatments, total RNA and cellular protein were extracted, the mRNA abundance of CEBPD, IL1B, IL6, PTGS2, and HSD11B1 was determined with qRT-PCR with primers illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1, and the protein abundance of C/EBPδ, COX-2, and 11β-HSD1 was measured with Western blotting with the antibodies illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S2. Methods of qRT-PCR and Western blotting were the same as described for the mouse tissue. The culture media were collected for measurement of IL-1β and IL-6 concentrations with human IL-11β and IL-6 ELISA kits respectively (both from Abclonal, Wuhan, China) according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (chip) assay in human amnion fibroblasts

The enrichment of p65 and C/EBPδ at PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 promoters in human amnion fibroblasts following LPS treatment were determined with ChIP assay as described previously [34]. Briefly, after crosslinking with 1% formaldehyde, amnion fibroblasts were lysed with 1% SDS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. The chromatin DNA of the lysed cells was sheared to optimal size of around 500 bp with sonication and was then immunoprecipitated with antibodies against human p65 (Cell Signaling Technology; #8242) or C/EBPδ (GeneTex, San Antonio, TX; GTX115047). An equal amount of pre-immune IgG served as negative control, and sheared DNA without immunoprecipitation served as input control. The immunoprecipitate was pulled down with the Protein A + G agarose Magnetic Beads (Millipore) on a magnetic stand. After reverse crosslinking, the sample was digested with proteinase K and RNase to remove protein and RNA respectively, and then subjected to DNA extraction using a DNA purification kit (Cwbiotech, Beijing, China) for subsequent qRT-PCR with primers aligning to the putative binding sites of p65 and C/EBPδ at PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 promoters. The primer sequences for ChIP assay are illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S5. The ratio of DNA precipitated by p65 and C/EBPδ antibodies over that of input control was calculated as a measure of p65 and C/EBPδ enrichment at PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 promoters.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The number for each experiment indicates replicate experiments using different tissues from independent patients or animals. After testing for normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test, paired or unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA test followed by the Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests was performed where appropriate to assess the difference statistically. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to plot and compare the gestational length data (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

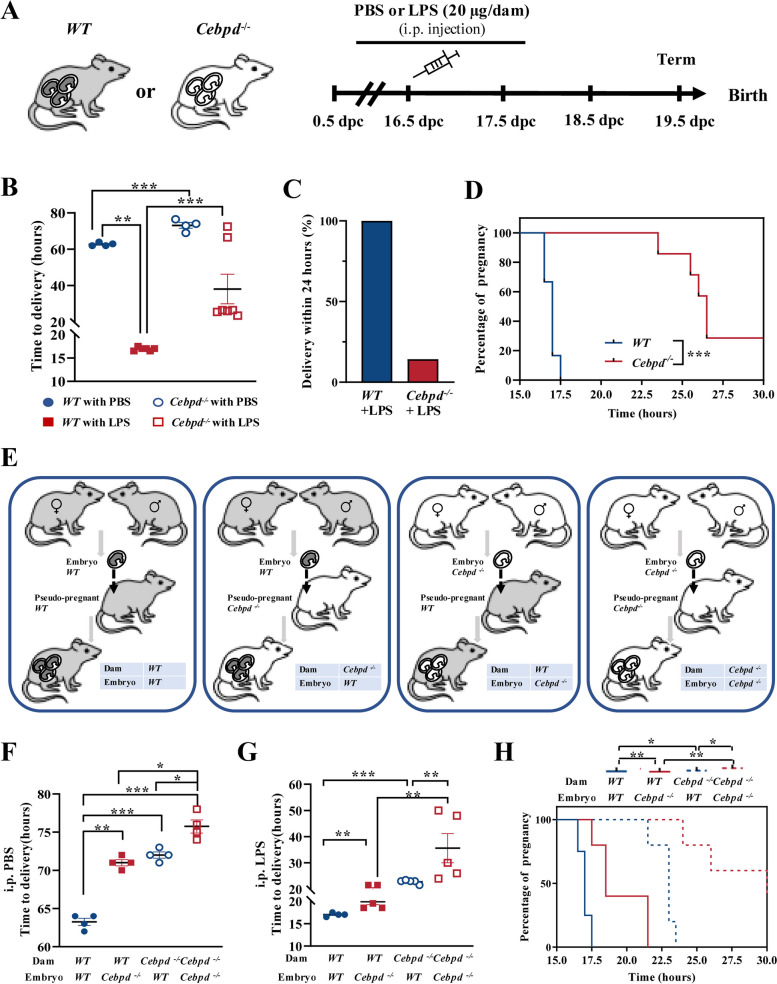

Cebpd deficiency delays infection-induced preterm birth

To investigate the role of C/EBPδ in infection-induced preterm labor, Cebpd–/– C57BL/6 mice were generated. Intraperitoneal administration of LPS (20 μg/dam, dissolved in PBS) was conducted at 16.5 dpc in WT (conceived by WT male mice) and Cebpd–/– pregnant mice (conceived by Cebpd–/– male mice) to simulate infection-induced preterm birth (Fig. 1A). As expected, all the WT mice delivered prematurely at 16.92 ± 0.38 h after LPS injection (at about 17 dpc), while all the WT mice injected with PBS delivered at term (at about 19.5 dpc) (Fig. 1B, C). However, in comparison to WT mice, a significant delay in delivery was observed in Cebpd–/– mice not only with PBS injection (Fig. 1B) as we demonstrated before [24] but also with LPS injection (Fig. 1B–D). These data indicate that C/EBPδ participated in both normal parturition at term and in infection-induced preterm birth.

Fig. 1.

Cebpd deficiency delays infection-induced preterm birth in the mouse. A The time-line illustrating the procedure of LPS (20 μg/dam, dissolved in 100 μL PBS) administration in pregnant mice. i.p., intraperitoneal injection. B Time to delivery after PBS (WT mice, n = 4; Cebpd−/− mice, n = 6) or LPS (WT mice, n = 4; Cebpd−/− mice, n = 7) injection. One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test was used. C The percentage of delivery within 24 h of WT or Cebpd−/− mice injected with LPS. D Gestational lengths in WT or Cebpd−/− mice injected with LPS. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test was used. E Experimental design for embryo transfers. Four groups were included: WT dams carrying WT embryos, WT dams carrying Cebpd−/− embryos, Cebpd−/− dams carrying WT embryos, and Cebpd−/− dams carrying Cebpd−/− embryos. F Time to delivery after PBS injection (n = 4 per group). One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test was used. G, H Time to delivery (G) and gestational lengths (H) of WT or Cebpd−/.− mice injected with LPS (n = 4–5 per group). One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test (G) and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test (H) was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

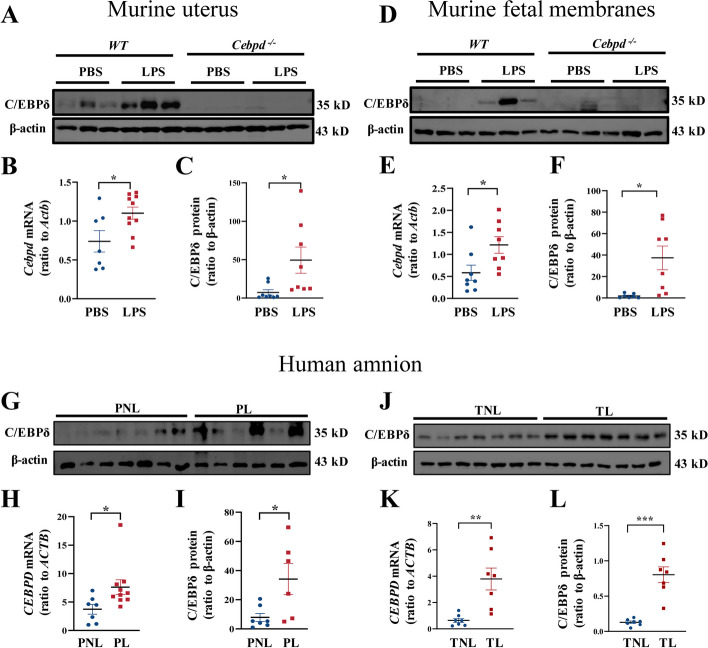

Next, we discriminated the contribution of fetal and maternal C/EBPδ signaling in infection-induced preterm birth by performing reciprocal embryo transfers, which resulted in the following four groups: WT dams with WT embryos transferred, WT dams with Cebpd–/– embryos transferred, Cebpd–/– dams with WT embryos transferred, and Cebpd–/– dams with Cebpd–/– embryos transferred (Fig. 1E). WT dams conceiving WT embryos delivered at term with PBS administration, while Cebpd–/– dams carrying Cebpd–/– embryos delivered post-term by about 12 h (Fig. 1F). As anticipated, preterm birth occurred in all WT dams with WT embryos after LPS administration. However, gestation was significantly prolonged irrespective of whether Cebpd was deficient only in the mother (Cebpd–/– dams carrying WT embryos) or only in the fetus (WT dams carrying Cebpd–/– embryos) in comparison with WT dams carrying WT embryos following either PBS or LPS administration (Fig. 1F–H). Notably, gestation was further prolonged in pregnancies with Cebpd deficiency in both mother and fetus when compared to pregnancy with Cebpd deficiency only in mother or fetus following either PBS or LPS administration (Fig. 1F–H). These data indicate that both maternal and fetal C/EBPδ participated in normal term parturition as well as in infection-induced preterm birth. The participation of both maternal and fetal C/EBPδ in infection-induced preterm birth was further supported by our finding that the abundance of C/EBPδ was significantly increased in both maternal uterus and fetal membranes following LPS administration to WT mice (Fig. 2A–F). Significant increases in C/EBPδ abundance were also observed in human fetal membranes, which are more readily obtained than human uterine tissue, both in normal spontaneous delivery at term and in infection-induced preterm birth in comparison with their respective controls (Fig. 2G–L). Next, we investigated the exact C/EBPδ-mediated inflammatory and parturition effects in maternal uterine tissue and fetal membranes.

Fig. 2.

Abundance of C/EBPδ in the mouse uterus and fetal membranes with or without LPS administration, and in the human amnion at term and preterm labor. A–F Abundance of C/EBPδ in the uterus (A–C) and fetal membranes (D–F) of WT or Cebpd−/.− mice with PBS or LPS administration (n = 7–10 per group). A and D are the representative immunoblots, B and E are the average mRNA data, C and F are the average protein data. G–L Abundance of C/EBPδ in the human amnion at preterm (G–I) and term (J–L) with or without labor. PNL, preterm non-labor; PL, preterm labor with infection. TNL, term non-labor; TL, term labor (n = 6–9 per group). G and J are the immunoblots, H and K are the average mRNA data, I and L are the average protein data. Unpaired Student’s t-test was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

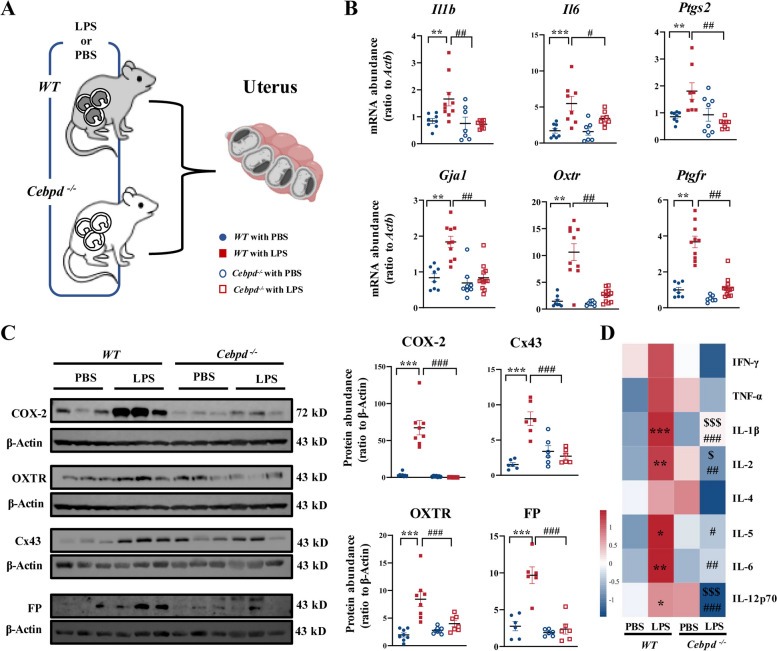

C/EBPδ-mediated inflammatory and parturition effects in the maternal uterus

Signals from multiple sources that initiate parturition converge onto the maternal uterus converting the myometrium from a quiescent state to a highly excitable state that can contract rhythmically and forcefully in labor [5, 35, 36]. During the transition, a series of genes encoding contraction-associated proteins (CAPs) are upregulated including Gja1 (encoding connexin-43, Cx43), Oxtr (encoding oxytocin receptor, OXTR), and Ptgfr (encoding PGF2α receptor, FP) and also pro-inflammatory genes such as Il1b (encoding interleukin 1β, IL-1β), Il6 (encoding interleukin 6, IL-6), and Ptgs2 (encoding COX-2) [37–40]. Using qRT-PCR, we found that the expression of Il1b, Il6, Ptgs2, Gja1, Oxtr, and Ptgfr were significantly increased in uterine tissue of the WT pregnant mouse at 12 h after LPS administration (Fig. 3A, B). However, these increases were not observed in the uterine tissue of Cebpd−/− mice at 12 h following LPS injection (Fig. 3B). Western blotting and cytokine microarray assays confirmed these changes at the protein level. Abundance of IL-1β, IL-6, COX-2, Cx43, OXTR, and FP was increased significantly in the uterine tissue of WT mice at 12 h after LPS injection (Fig. 3C, D, Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Knockout of Cebpd significantly attenuated the induction of these genes by LPS (Fig. 3C, D, Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Cebpd deficiency prevents LPS-induced uterine contractility and inflammation. A A schematic diagram showing experimental design and grouping. Pregnant WT and Cebpd−/− mice were injected with LPS (20 μg/dam) or PBS on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc), and the uterine tissues were collected on 17 dpc. B The mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes in the uterus as measured with qRT-PCR (n = 7–12 per group). C The protein abundance of contraction-associated proteins in the uterus as measured with Western blotting. Left panel is the representative immunoblots, and right panel is the average data (n = 7–9 per group). D The protein abundance of inflammatory cytokines as measured with cytokine microarray assay (n = 4 per group). One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test was used (B–D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT with PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. WT with LPS; $P < 0.05, $$$P < 0.001 vs. Cebpd−/− with PBS

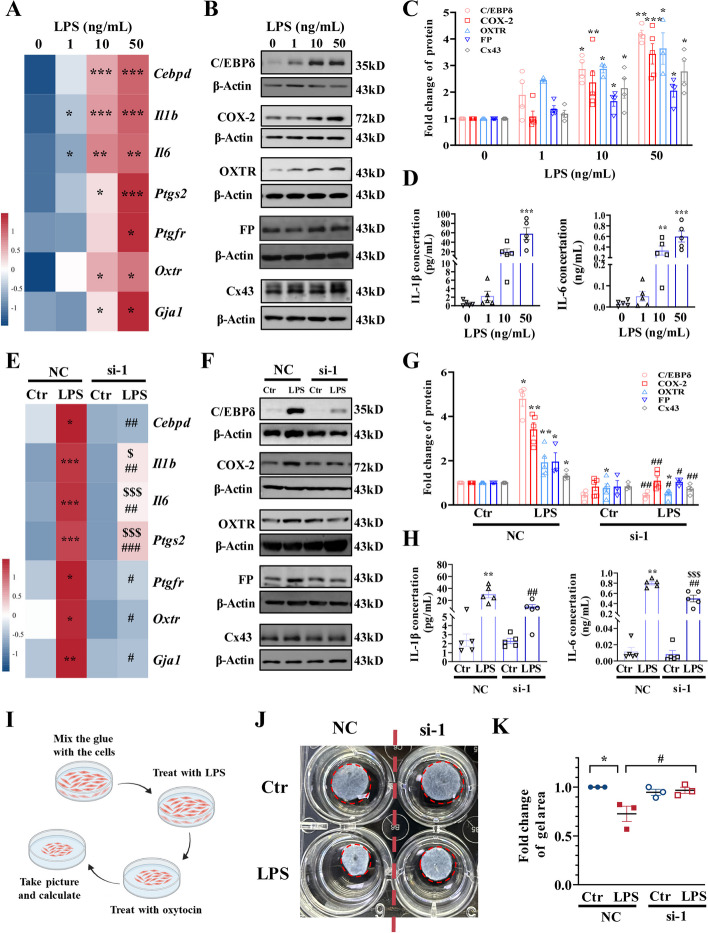

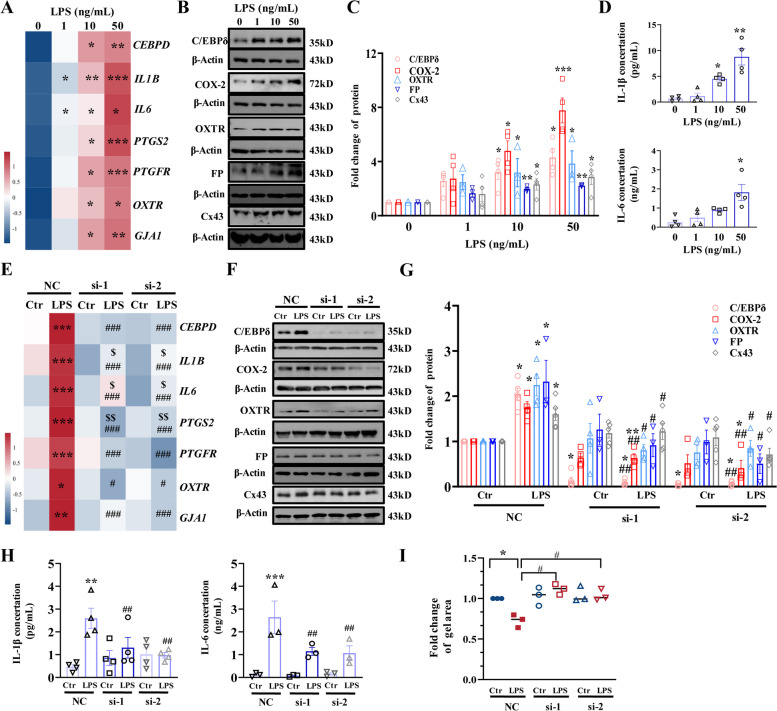

The role of C/EBPδ in the regulation of genes pertinent to inflammation and myometrial transition/contraction was further investigated in cultured mouse and human primary myometrial cells prepared from the myometrial tissue of pregnant dams and women. We found that LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) dose-dependently induced not only Cebpd but also IL1b, IL6, Ptgs2, Gja1, Ptgfr, and Oxtr mRNA in mouse myometrial cells (Fig. 4A, Additional file 1: Fig. S3A). Consistently, protein abundance of IL-1β, IL-6, COX-2, Cx43, FP, and OXTR as well as C/EBPδ was also dose-dependently increased by LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) in mouse myometrial cells (Fig. 4B–D). Although siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd had no effect on the basal expression of the genes mentioned above, knockdown of Cebpd significantly attenuated the induction of these genes by LPS (50 ng/mL) in mouse myometrial cells (Fig. 4E–H, Additional file 1: Fig. S3B). Moreover, collagen gel contraction assay showed that LPS (50 ng/mL; 12 h)-induced shrinkage in gel area, an indicator of myometrial cell contraction, was significantly attenuated by siRNA-mediated Cebpd knockdown (Fig. 4I–K), suggesting the involvement of C/EBPδ in LPS-induced contractility of myometrial cells at 12 h.

Fig. 4.

Involvement of C/EBPδ in the induction of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes by LPS in the mouse myometrial cells. A Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes (n = 4). B–D Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on the protein abundance of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes (n = 3–5). B is the representative immunoblots, C is the average data of B, D is the concentration of IL-1β and IL-6 in the culture medium. E Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS (50 ng/mL; 12 h)-induced expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the mRNA level (n = 3–4). F–H Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS (50 ng/mL; 12 h)-induced expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the protein level (n = 3–5). F is the representative immunoblots, G is the average data of F, H is the concentration of IL-1β and IL-6 in the culture medium. I Diagram illustrating the procedure of collagen contractility assay. J, K Effect of Cebpd knockdown on contractility of murine myometrial cells as measured with collagen contractility assay (n = 3). J is the representative image and K is the average data. One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test (A, C–E, G, H, K) was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 or NC-Ctr; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. NC-LPS; $P < 0.05, $$$P < 0.001 vs. si-Ctr

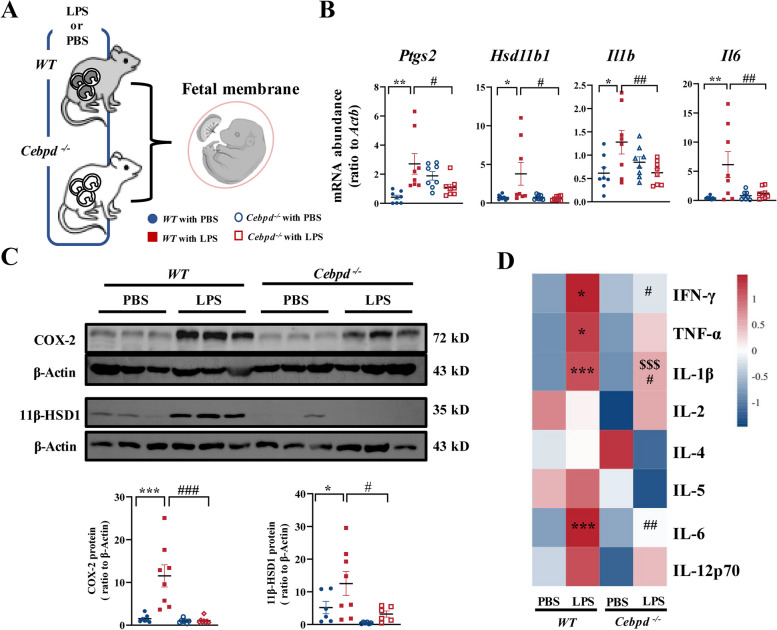

Consistently, studies in human myometrial cells also showed that LPS (1, 10 and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) treatment dose-dependently upregulated the mRNA abundance of not only CEBPD, but also IL1B, IL6, PTGS2, GJA1, PTGFR, and OXTR (Fig. 5A, Additional file 1: Fig. S4A). Protein abundance of IL-1β, IL-6, COX-2, Cx43, FP, and OXTR as well as C/EBPδ was also increased by LPS (1, 10 and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) in a concentration-dependent manner in human myometrial cells (Fig. 5B–D). Although siRNA-mediated CEBPD knockdown had no effect on the basal expression of the genes mentioned above, CEBPD knockdown significantly attenuated the induction of these genes by LPS (50 ng/mL) in human myometrial cells (Fig. 5E–H, Additional file 1: Fig. S4B). Collagen gel contraction assay also showed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD attenuated LPS (50 ng/mL; 12 h)-induced human myometrial cell contraction (Fig. 5I). These results suggest that C/EBPδ plays a similar role in the mouse and human myometrium in the induction of genes pertinent to inflammation and parturition.

Fig. 5.

Role of C/EBPδ in the induction of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes by LPS in human myometrial cells. A Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on the expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the mRNA levels (n = 3–4). B–D Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on the expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the protein levels (n = 3–5). B is the representative immunoblots, C is the average data of B, D is the concentration of IL-1β and IL-6 in the culture medium. E Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS-induced expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the mRNA level (n = 4). F–H Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS-induced expression of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes at the protein level (n = 3–5). F is the representative immunoblots, G is the average data of B, H is the concentration of IL-1β and IL-6 in the culture medium. I Effect of Cebpd knockdown on contractility of human myometrial cells. The contractility was determined by collagen contractility assay (n = 3). si-1 and si-2 are two separated siRNA. One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test (A, C–E, G–I) was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 or NC-Ctr; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. NC-LPS; $P < 0.05, $$P < 0.01 vs. si-Ctr

C/EBPδ-mediated inflammatory and parturition effects in the fetal membranes

The fetal membranes have a unique role in parturition. The membranes not only are the reservoir of PGE2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines but also boast the largest capacity of glucocorticoid regeneration among fetal tissues, an action crucial for labor onset [41–50]. Therefore, the fetal membranes are among the most important gestational tissues that give rise to parturition-initiating signals. A surge of these signals is an indicator of membrane activation for labor onset [51, 52]. Membrane rupture and infection are well-recognized stimuli of membrane activation [52, 53]. Therefore, we investigated the role of C/EBPδ in LPS-induced expression of those genes involved in the synthesis of PGE2 and classical pro-inflammatory cytokines and glucocorticoid regeneration in the fetal membranes of WT and Cebpd–/– mice. The results showed that the fetal membranes of WT mice displayed a drastic upregulation of Ptgs2, Hsd11b1, Il1b, and Il6 at 12 h after LPS injection (20 μg/dam). However, these increases were not observed in the fetal membranes of Cebpd–/– mice at 12 h after LPS administration (Fig. 6A, B). Western blotting and cytokine microarray assays confirmed the above changes at the protein level. Abundance of 11β-HSD1, COX-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 was all significantly increased in WT at 12 h after LPS administration (Fig. 6C, D, Additional file 1: Fig. S5). Knockout of Cebpd significantly attenuated the induction of these genes by LPS (Fig. 6C, D, Additional file 1: Fig. S5).

Fig. 6.

Cebpd deficiency hampers LPS-induced fetal membrane activation. A A schematic diagram showing experimental design and grouping. Pregnant WT and Cebpd−/− mice were injected with LPS (20 μg/dam) or PBS on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc), and the fetal membrane tissues were collected on 17 dpc. B The mRNA abundance of Ptgs2, Hsd11b1, Il1b, and Il6 in the fetal membranes as measured with qRT-PCR (n = 8 per group). C The protein abundance of COX-2 and 11β-HSD1 in the fetal membranes as measured with Western blotting. Top panel is the representative immunoblots, and bottom panel is the average data (n = 6–8 per group). D The protein abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines as measured with cytokine microarray assay (n = 4 per group). One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test (B–D) was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT with PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. WT with LPS; $$$P < 0.001 vs. Cebpd−/− with PBS

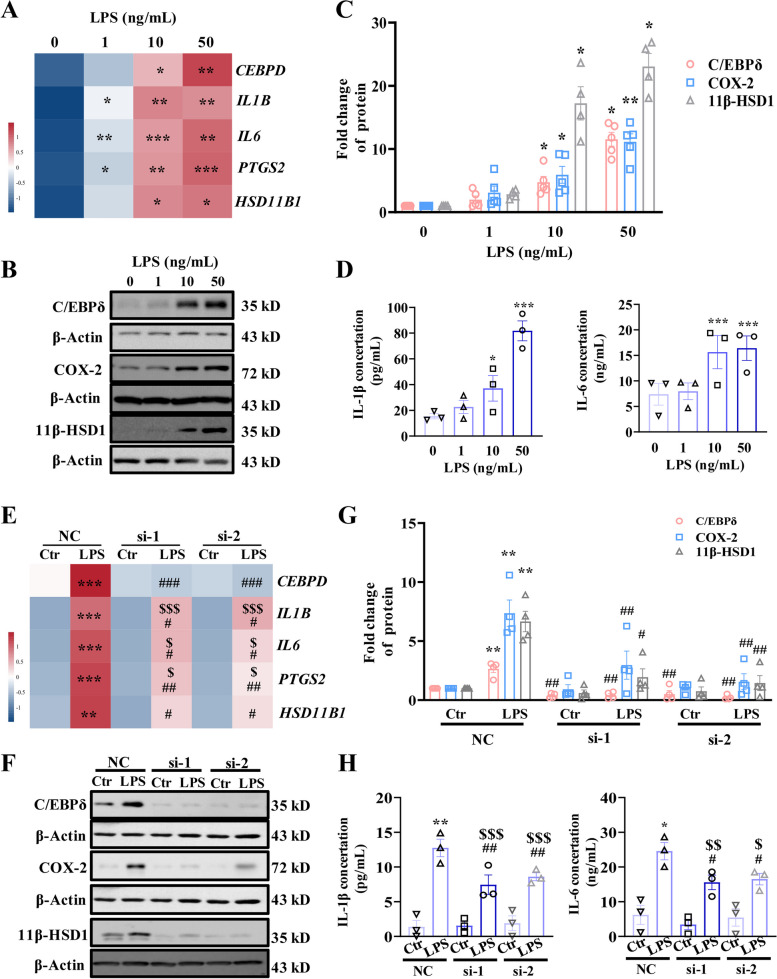

Studies in cultured human amnion fibroblasts, a major site of PGE2, pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis and glucocorticoid regeneration at parturition [41, 45–49] showed that LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) increased the abundance of CEBPD, PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 mRNA and C/EBPδ, 11β-HSD1, COX-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 protein in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7A-D, Additional file 1: Fig. S6A). Although siRNA-mediated knockdown of had no effect on the basal expression of these genes, CEBPD knockdown significantly attenuated the induction of these genes by LPS (50 ng/mL) in human amnion fibroblasts (Fig. 7E–H, Additional file 1: Fig. S6B), indicating a crucial role of C/EBPδ in the activation of fetal membrane by LPS.

Fig. 7.

Role of C/EBPδ in the induction of genes pertinent to fetal membrane activation by LPS in human amnion fibroblasts. A Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 mRNA expression (n = 3). B–D Concentration-dependent effects of LPS (1, 10, and 50 ng/mL; 12 h) on COX-2 and 11β-HSD1 protein (B and C, n = 4–5) abundance and IL-1β and IL-6 (D; n = 3) secretion. B is the representative immunoblots, and C is the average data of B. E Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS-induced expression of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 at the mRNA level (n = 3). F–H Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cebpd on LPS-induced expression of COX-2 and 11β-HSD1 (F and G; n = 4), and secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 (H; n = 3) at the protein level. F is the representative immunoblots, and G is the average data of F. si-1 and si-2 are two separated siRNA. One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test (A, C–E, G, H) was used. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 or NC-Ctr; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.01 vs. NC-LPS; $P < 0.05, $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.01 vs. si-Ctr

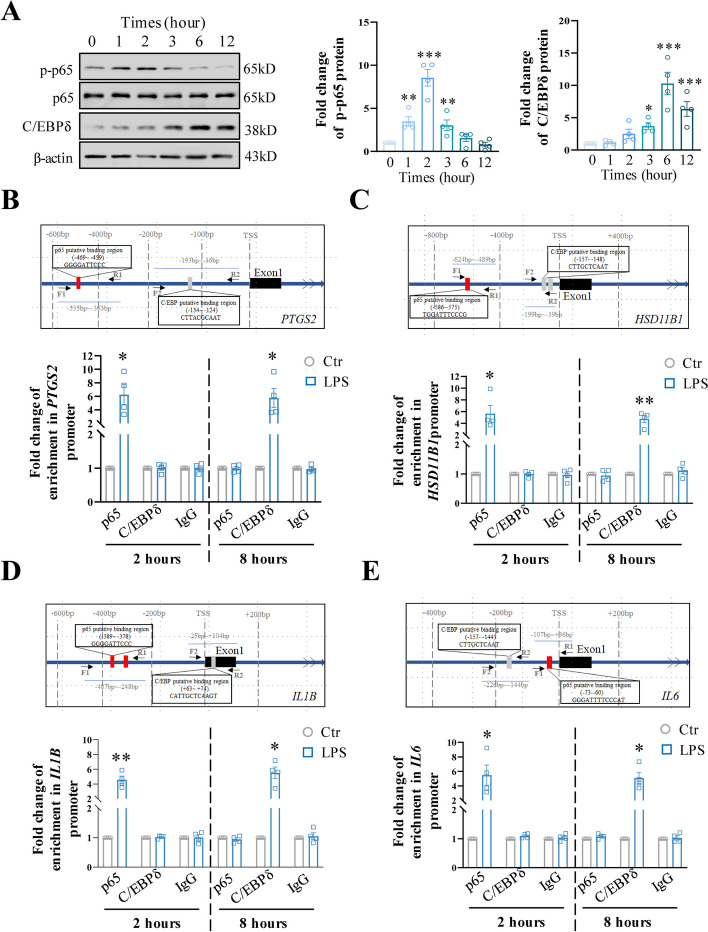

Interplay of C/EBPδ and NF-κB in the mediation of LPS-induced effects pertinent to inflammation and parturition

Next, we used cultured human amnion fibroblasts, which are more readily obtained than myometrial cells, to address the involvement of C/EBPδ in LPS-induced expression of genes pertinent to inflammation and parturition. We found that the induction of CEBPD, PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 mRNA by LPS (50 ng/mL) lasted for at least 12 h (Additional file 1: Fig. S7). However, the induction of p65 phosphorylation, an indicator of NF-κB activation, by LPS lasted for only 3 h. By contrast, the induction of C/EBPδ protein did not occur until 3 h after LPS treatment and lasted for at least 12 h (Fig. 8A). These results indicate that NF-κB and C/EBPδ may mediate LPS-induced inflammatory responses in a consecutive manner. This notion was supported by ChIP assay which showed that the enrichment of p65 was significantly increased at the promoters of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 at 2 h but not at 8 h after LPS (50 ng/mL) treatment, while the enrichment of C/EBPδ at the promoters of these genes was significantly increased at 8 h but not at 2 h after LPS (50 ng/mL) treatment in human amnion fibroblasts (Fig. 8B–E). Further support was provided by the findings that the induction of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 by LPS (50 ng/mL) at 3 h was completely blocked by JSH (10 μM), a specific p65 antagonist, but not by siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD expression (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). Of interest, the induction of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 by LPS at 12 h could be significantly blocked by either siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD (Fig. 7C, D) or JSH (10 μM) (Additional file 1: Fig. S9). Because NF-κB activation lasted for only 6 h and no increases in NF-κB enrichment at these gene promoters were observed at 8 h after LPS treatment, we believe that this inhibitory effect of JSH on the induction of PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, and IL6 by LPS at 12 h can be attributed to the blockade of NF-κB-mediated CEBPD expression by LPS (Additional file 1: Fig. S8 and S9). All these data suggest that NF-κB and C/EBPδ may act in a consecutive manner in the induction of genes pertinent to inflammation and parturition. Of interest, TLR4 was found to be a target gene of C/EBPδ in macrophages [54]. Despite the constitutive expression of TLR4 in human amnion fibroblasts, there was no change of TLR4 expression by LPS (50 ng/mL; 3 h) or upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of CEBPD in human amnion fibroblasts (Additional file 1: Fig. S10). These results indicate that TLR4 expression was not affected by LPS or C/EBPδ in this cell type, at least at this early time point.

Fig. 8.

Interplay of C/EBPδ and NF-κB in the mediation of LPS-induced inflammatory reactions in human amnion fibroblasts. A Time-dependent effects of LPS (50 ng/mL; 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 h) on C/EBPδ protein and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation (n = 4). Left panel is the representative immunoblots, and right panel is the average data. One-way ANOVA test followed by Newman-Keuls multiple-comparisons test was used. B–E ChIP assay showing the enrichments of p65 and C/EBPδ at PTGS2 (B), HSD11B1 (C), IL1B (D), and IL6 (E) gene promoters in human amnion fibroblasts at 2 h and 8 h after LPS treatment (50 ng/mL) (n = 4). IgG served as negative control. Top panels of B–E are diagrams showing the putative binding sites for p65 and C/EBPδ at PTGS2 (B), HSD11B1 (C), IL1B (D), and IL6 (E) gene promoters. Red box indicates p65 binding sites, and gray box indicates C/EBPδ binding sites. Arrows indicate primer aligning positions in ChIP assay. F1 (forward primer 1) and R1 (reverse primer 1) are used to amplify sequences containing p65 binding sites; F2 and R2 are used to amplify sequences containing C/EBPδ binding sites. TSS, transcription start site. Paired Student’s t-test was used. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 or Ctr

Discussion

Infection-induced inflammation of the intrauterine tissues is a major cause of preterm birth [3–5]. It has been very well recognized that invading microorganisms can activate the innate immune system resulting in an intrauterine milieu rich in pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and prostaglandins. Among intrauterine tissues, the myometrium and fetal membranes are particularly worthy of attention in relation to initiation of parturition since events induced by inflammation in these tissues are well-recognized causes of parturition. Inflammation will transform the myometrium from a quiescent state to a highly contractile state [37–40, 55–57], while inflammation of the fetal membranes will not only induce abundant production of pro-labor factors but also remodel the extracellular matrix leading to membrane rupture [52, 53, 58–60]. Undoubtedly, the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and COX-2 is under the tight control of the classical pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB in gestational tissues [61–65]. In the present study, we also demonstrated that NF-κB per se not only directly mediated early inflammatory responses directly but also indirectly mediated late inflammatory responses through induction of C/EBPδ. However, NF-κB activation is relatively short-lived because of a negative feedback loop reinforced by the NF-κB inhibitory proteins IκBs [14–17]. Consistently, several studies have found that the abundance of IκBs is increased in intrauterine tissues in both term and preterm labor irrespective of the presence or absence of infection [66–69], indicating that the inflammatory responses mediated by NF-κB per se would not last long. In this study, we revealed that C/EBPδ, induced by NF-κB, may serve as another crucial pro-inflammatory transcription factor to sustain the initial inflammatory responses induced by NF-κB. We believe that this sequential activation of NF-κB and C/EBPδ may be required for the persistent inflammation in the intrauterine tissues in both normal term and infection-induced preterm labor since Cebpd deficiency delayed labor in both scenarios in the mouse.

The interaction between NF-κB and C/EBPδ in the induction of inflammatory responses has been documented in a number of non-gestational tissues [29–31]. C/EBPδ is a critical mediator of LPS-induced acute lung injury by inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine productions in macrophage [70]. C/EBPδ is also found to underly LPS-induced systemic inflammation, as reflected by reduced plasma TNFα and IL-6 levels in Cebpd-deficient mice [71]. Given the interaction between NF-κB and C/EBPδ in the inflammatory responses in multiple tissues, we believe that this collaboration between NF-κB and C/EBPδ might be a general mechanism underlying persistent inflammatory reactions in both gestational and non-gestational tissues. This feature of C/EBPδ-mediated late inflammatory responses in gestational tissues may be of particular importance to the success of parturition given the feedforward nature of the labor process. Therefore, targeting C/EBPδ would help change the course of the late inflammatory responses in gestational tissues, which may be of clinical value in the treatment of infection-induced preterm birth.

Myometrial contraction, cervical ripening, and fetal membrane activation are events common to both normal term and infection-induced preterm labor processes [3, 5]. All these crucial events can be initiated by inflammation. In this study, we found that C/EBPδ is essential for infection-induced expression of not only pro-inflammatory genes (e.g., IL1b, IL6, PTGS2) but also for CAPs genes (OXTR, PTGFR, and GJA1) in myometrial cells. Since pro-inflammatory mediators can promote the expression of CAPs in the myometrium [72, 73], we are still uncertain whether C/EBPδ regulates the expression of CAPs directly or indirectly through inducing pro-inflammatory mediators in myometrial cells. However, binding sites for C/EBPs have been identified in the promoters of a series of genes pertinent to parturition, including PTGS2, IL1B, IL6, and HSD11B1 [24, 74–77]. In this study, we also found that C/EBPδ could directly bind to the promoters of those genes to induce their expression under LPS stimulation in human amnion fibroblasts, suggesting that these genes may be subject to the regulation by C/EBPδ directly or indirectly following stimulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The fetal membranes not only cover about 70% of the inner uterine wall in pregnancy but are also a reservoir for a number of crucial parturition-initiating factors, including pro-inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and glucocorticoids (via regeneration by 11β-HSD1) [41–49]. An upsurge of synthesis or regeneration of these effectors is a landmark event of activation of fetal membranes in parturition [51, 52]. Prostaglandins, specifically PGE2 and PGF2α synthesized by COX-2, are well-recognized potent inducers of cervical ripening, myometrial contraction, and membrane rupture in parturition [78–80]. Glucocorticoids regenerated by 11β-HSD1 are not only involved in extracellular matrix remodeling associated with membrane rupture [81–84] but also in the induction of prostaglandin synthesis [24, 85–87]. In this study, we found that C/EBPδ participated in all these events associated with activation of fetal membranes in infection. Our previous study has shown that C/EBPδ acts as a common transcription factor for 11β-HSD1 and COX-2 expression in human amnion fibroblasts in normal parturition at term [24], indicating that C/EBPδ participates in both normal term parturition and in infection-induced preterm birth. This conclusion was also supported by findings in this study that C/EBPδ abundance was significantly increased in human fetal membranes both in normal parturition at term and in infection-induced preterm birth.

C/EBPδ belongs to the C/EBP family, which includes six members [18–20]. In inflammatory responses, in addition to C/EBPδ, the expression of C/EBPβ can also be induced by LPS and pro-inflammatory cytokines [26–28, 88]. Notably, dimerization (either homodimer or heterodimer) is a prerequisite for C/EBP members to bind DNA [18, 19, 89], indicating that other C/EBP members may also be required to heterodimerize with C/EBPδ in the induction of inflammatory reactions in intrauterine tissues at parturition. However, our previous study demonstrated that C/EBPδ is the most abundant C/EBP member in the human amnion tissue [24], suggesting C/EBPδ may play a dominant role at least in the amnion in the induction of inflammatory responses. It would be of interest to examine the interaction of C/EBPδ with other C/EBP members in the inflammatory responses of the gestational tissues in both normal term parturition and in infection-induced preterm birth. Previous studies demonstrated that NLRP3 (NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3) and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-M and IRAK-4 are involved in the LPS-induced inflammatory reactions [90–93]. The role of NLRP3 and IRAK-M and IRAK-4 in C/EBPδ signaling in infection-induced inflammatory responses in intrauterine tissues is another interesting issue to examine in the future. Although we found that C/EBPδ deficiency can delay both normal term and infection-induced preterm birth, parturition eventually ensues, suggesting that in vivo, there must be a mechanism to compensate for C/EBPδ deficiency in parturition. At the current stage, we are unclear about this compensatory mechanism, but it is certainly an interesting issue to explore in the future.

Limitations

Although preterm birth induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS is a classical mouse model of infection-induced preterm birth [94–96], this mouse model does not fully reflect the complexities of infection-induced preterm birth in humans. Unlike the sepsis encountered in this mouse model, there are usually no maternal symptoms of sepsis in the majority of infection-induced preterm deliveries in humans. At the current stage, we could not rule out the effect of systemic inflammation on preterm birth in this mouse model, despite the evidence of involvement of the intrauterine tissue inflammation. In addition, the role of C/EBPδ in inflammatory responses was investigated only in myometrial cells and amnion fibroblasts, the two important cell types in parturition. It should be kept in mind that there is increased infiltration of immune cells in intrauterine tissues in parturition, which further intensifies the inflammatory reactions. Undoubtedly, the role of C/EBPδ in infiltrated immune cells is another interesting issue to examine in the future.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated for the first time that C/EBPδ is a crucial transcription factor underlying infection-induced sustained inflammatory responses in both maternal myometrial tissue and fetal membranes. Moreover, we have revealed that C/EBPδ, induced by NF-κB, may act to sustain NF-κB-initiated inflammatory responses. Therefore, targeting C/EBPδ may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of infection-induced preterm birth.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figures S1-S10, and Tables S1-S5. Fig. S1 Immunofluorescence staining of myometrial cells with α-SMA. Fig. S2 The protein abundance of inflammatory cytokines in the uterus of mouse with PBS or LPS administration. Fig. S3 Involvement of C/EBPδ in the induction of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes by LPS in the mouse myometrial cells. Fig. S4 Role of C/EBPδ in the induction of pro-inflammatory and contraction-associated genes by LPS in human myometrial cells. Fig. S5 The protein abundance of inflammatory cytokines in the fetal membranes of mouse with PBS or LPS administration. Fig. S6 Role of C/EBPδ in the induction of genes pertinent to fetal membrane activation by LPS in human amnion fibroblasts. Fig. S7 Time-dependent effect of LPS (50 ng/mL; 0, 1, 2, 3, 6 and 12 h) on PTGS2, HSD11B1, IL1B, IL6 and CEBPD mRNA in human amnion fibroblasts. Fig. S8 Role of NF-κB in the mediation of LPS-induced genes associated with inflammation and parturition at 3 h in human amnion fibroblasts. Fig. S9 Role of NF-κB in the mediation of LPS-induced genes associated with inflammation and parturition at 12 h in human amnion fibroblasts. Fig. S10 Abundance of TLR4 mRNA in human amnion fibroblasts. Table S1 Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR. Table S2 Antibody information. Table S3 Demographic and clinical characteristics of recruited pregnant women with preterm deliveries. Table S4 Demographic and clinical characteristics of recruited pregnant women with term deliveries. Table S5 Primer sequences used in ChIP.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lu-yao Wang, Yao Su, and Hao Ying for assistance with sample collection.

Abbreviations

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- C/EBP

CCAAT enhancer-binding protein

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- PG

Prostaglandin

- 11β-HSD1

11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1

- WT

Wide type

- Cebpd−/−

Cebpd Deficiency

- dpc

Days post coitum

- i.p.

Intraperitoneal

- PBS

Phosphate buffer solution

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RIPA

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- α-SMA

α-Smooth muscle actin

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- interleukin 1β

IL-1β

- interleukin 6

IL-6

- TNL

Term non-labor

- TL

Term labor

- PNL

Preterm non-labor

- PL

Preterm labor

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- CAPs

Contraction-associated proteins

- Gja1/Cx43

Connexin-43

- OXTR

Oxytocin receptor

- Ptgfr/FP

PGF2α receptor

- NLRP3

NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- IRAK

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase

Authors’ contributions

W.S.W and K.S conceived the idea and designed the study. W.J.L, F.Z, M.D.L and F.P, performed the experiments. L.J.L and J.W.L collected and analyzed clinical samples. W.J.L, F.Z and W.S.W analyzed the data. W.S.W, K.S, L.M. and W.J.L wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071677 82271717 and 81830042), National Key R & D Program of China (2022YFC2704602), Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZLCX20210201), Three-Year Action Plan for Strengthening the Construction of the Public Health System in Shanghai (GWVI-11.1–36), and Shanghai’s Top Priority Research Center Construction Project (2023ZZ02002).

Availability of data and materials

This study has not generated data that requires deposition in a public repository. The original data and materials presented in the study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (approval code: RA-2022–172). All participants provided written informed consent for collection of myometrial tissue and fetal membranes for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wen-Jia Lei and Fan Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Kang Sun, Email: sungangrenji@hotmail.com.

Wang-Sheng Wang, Email: wangsheng_wang@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ohuma EO, Moller AB, Bradley E, Chakwera S, Hussain-Alkhateeb L, Lewin A, Okwaraji YB, Mahanani WR, Johansson EW, Lavin T, et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2023;402(10409):1261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perin J, Mulick A, Yeung D, Villavicencio F, Lopez G, Strong KL, Prieto-Merino D, Cousens S, Black RE, Liu L. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(2):106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazor M. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):17–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345(6198):760–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero R, Grivel JC, Tarca AL, Chaemsaithong P, Xu Z, Fitzgerald W, Hassan SS, Chaiworapongsa T, Margolis L. Evidence of perturbations of the cytokine network in preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):836 e831–836 e818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown AG, Maubert ME, Anton L, Heiser LM, Elovitz MA. The tracking of lipopolysaccharide through the feto-maternal compartment and the involvement of maternal TLR4 in inflammation-induced fetal brain injury. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019;82(6): e13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal V, Hirsch E. Intrauterine infection and preterm labor. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17(1):12–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero R, Erez O, Espinoza J. Intrauterine infection, preterm labor, and cytokines. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12(7):463–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Presicce P, Park CW, Senthamaraikannan P, Bhattacharyya S, Jackson C, Kong F, Rueda CM, DeFranco E, Miller LA, Hildeman DA, et al. IL-1 signaling mediates intrauterine inflammation and chorio-decidua neutrophil recruitment and activation. JCI Insight. 2018;3(6):e98306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(6): a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renner F, Schmitz ML. Autoregulatory feedback loops terminating the NF-kappaB response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(3):128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearns JD, Basak S, Werner SL, Huang CS, Hoffmann A. IkappaBepsilon provides negative feedback to control NF-kappaB oscillations, signaling dynamics, and inflammatory gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(5):659–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razani B, Zarnegar B, Ytterberg AJ, Shiba T, Dempsey PW, Ware CF, Loo JA, Cheng G. Negative feedback in noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling modulates NIK stability through IKKalpha-mediated phosphorylation. Sci Signal. 2010;3(123):ra41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298(5596):1241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nerlov C. The C/EBP family of transcription factors: a paradigm for interaction between gene expression and proliferation control. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(7):318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramji DP, Foka P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 2002;365(Pt 3):561–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsukada J, Yoshida Y, Kominato Y, Auron PE. The CCAAT/enhancer (C/EBP) family of basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors is a multifaceted highly-regulated system for gene regulation. Cytokine. 2011;54(1):6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu X, Si J, Zhang Y, Dewille JW. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-delta (C/EBP-delta) regulates cell growth, migration and differentiation. Cancer Cell Int. 2010;10: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balamurugan K, Sterneck E. The many faces of C/EBPdelta and their relevance for inflammation and cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9(9):917–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman KE, Kotelevtsev YV, Jamieson PM, Williams LJ, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR. Tissue-specific modulation of glucocorticoid action by the 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25(2):583–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu JW, Wang WS, Zhou Q, Ling LJ, Ying H, Sun Y, Myatt L, Sun K. C/EBPdelta drives key endocrine signals in the human amnion at parturition. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(6): e416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim H, Paria BC, Das SK, Dinchuk JE, Langenbach R, Trzaskos JM, Dey SK. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;91(2):197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alam T, An MR, Papaconstantinou J. Differential expression of three C/EBP isoforms in multiple tissues during the acute phase response. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(8):5021–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardinaux JR, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. Pro-inflammatory cytokines induce the transcription factors C/EBPbeta and C/EBPdelta in astrocytes. Glia. 2000;29(1):91–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granger RL, Hughes TR, Ramji DP. Stimulus- and cell-type-specific regulation of CCAAT-enhancer binding protein isoforms in glomerular mesangial cells by lipopolysaccharide and cytokines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1501(2–3):171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu YC, Kim I, Lye E, Shen F, Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Gerondakis S, Akira S, Gaffen SL, Yeh WC, et al. Differential role for c-Rel and C/EBPbeta/delta in TLR-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2009;182(11):7212–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poli V. The role of C/EBP isoforms in the control of inflammatory and native immunity functions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(45):29279–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litvak V, Ramsey SA, Rust AG, Zak DE, Kennedy KA, Lampano AE, Nykter M, Shmulevich I, Aderem A. Function of C/EBPdelta in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4-induced signals. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngo P, Ramalingam P, Phillips JA, Furuta GT. Collagen gel contraction assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mi Y, Wang W, Lu J, Zhang C, Wang Y, Ying H, Sun K. Proteasome-mediated degradation of collagen III by cortisol in amnion fibroblasts. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;60(2):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang F, Lu JW, Lei WJ, Li MD, Pan F, Lin YK, Wang WS, Sun K. Paradoxical Induction of ALOX15/15B by cortisol in human amnion fibroblasts: implications for inflammatory responses of the fetal membranes at parturition. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison EA, Cushman LF. Prevention of preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(19):1979 author reply 1979–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith R, Imtiaz M, Banney D, Paul JW, Young RC. Why the heart is like an orchestra and the uterus is like a soccer crowd. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mittal P, Romero R, Tarca AL, Gonzalez J, Draghici S, Xu Y, Dong Z, Nhan-Chang CL, Chaiworapongsa T, Lye S, et al. Characterization of the myometrial transcriptome and biological pathways of spontaneous human labor at term. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(6):617–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pique-Regi R, Romero R, Garcia-Flores V, Peyvandipour A, Tarca AL, Pusod E, Galaz J, Miller D, Bhatti G, Para R, et al. A single-cell atlas of the myometrium in human parturition. JCI Insight. 2022;7(5):e153921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leimert KB, Xu W, Princ MM, Chemtob S, Olson DM. Inflammatory amplification: a central tenet of uterine transition for labor. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11: 660983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan YW, van den Berg HA, Moore JD, Quenby S, Blanks AM. Assessment of myometrial transcriptome changes associated with spontaneous human labour by high-throughput RNA-seq. Exp Physiol. 2014;99(3):510–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keelan JA, Blumenstein M, Helliwell RJ, Sato TA, Marvin KW, Mitchell MD. Cytokines, prostaglandins and parturition–a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl A):S33-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy BE. Chorionic membrane as an extra-adrenal source of foetal cortisol in human amniotic fluid. Nature. 1977;266(5598):179–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menon R. Human fetal membranes at term: dead tissue or signalers of parturition? Placenta. 2016;44:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duchesne MJ, Thaler-Dao H, de Paulet AC. Prostaglandin synthesis in human placenta and fetal membranes. Prostaglandins. 1978;15(1):19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okazaki T, Casey ML, Okita JR, MacDonald PC, Johnston JM. Initiation of human parturition. XII. Biosynthesis and metabolism of prostaglandins in human fetal membranes and uterine decidua. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 139(4):373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li W, Wang W, Zuo R, Liu C, Shu Q, Ying H, Sun K. Induction of pro-inflammatory genes by serum amyloid A1 in human amnion fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keelan JA, Sato T, Mitchell MD. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 production by human amnion: regulation by cytokines, growth factors, glucocorticoids, phorbol esters, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Biol Reprod. 1997;57(6):1438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun K, Myatt L. Enhancement of glucocorticoid-induced 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression by proinflammatory cytokines in cultured human amnion fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2003;144(12):5568–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lei WJ, Zhang F, Lin YK, Li MD, Pan F, Sun K, Wang WS. IL-33/ST2 axis of human amnion fibroblasts participates in inflammatory reactions at parturition. Mol Med. 2023;29(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang F, Sun K, Wang WS. Identification of a feed-forward loop between 15(S)-HETE and PGE2 in human amnion at parturition. J Lipid Res. 2022;63(11): 100294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W, Chen ZJ, Myatt L, Sun K. 11beta-HSD1 in human fetal membranes as a potential therapeutic target for preterm birth. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(3):241–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menon R, Behnia F, Polettini J, Richardson LS. Novel pathways of inflammation in human fetal membranes associated with preterm birth and preterm pre-labor rupture of the membranes. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(4):431–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menon R, Richardson LS. Preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes: a disease of the fetal membranes. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(7):409–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balamurugan K, Sharan S, Klarmann KD, Zhang Y, Coppola V, Summers GH, Roger T, Morrison DK, Keller JR, Sterneck E. FBXW7alpha attenuates inflammatory signalling by downregulating C/EBPdelta and its target gene Tlr4. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tribe RM, Moriarty P, Dalrymple A, Hassoni AA, Poston L. Interleukin-1beta induces calcium transients and enhances basal and store operated calcium entry in human myometrial smooth muscle. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(5):1842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frascoli M, Coniglio L, Witt R, Jeanty C, Fleck-Derderian S, Myers DE, Lee TH, Keating S, Busch MP, Norris PJ, et al. Alloreactive fetal T cells promote uterine contractility in preterm labor via IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(438):eaan2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Friebe-Hoffmann U, Chiao JP, Rauk PN. Effect of IL-1beta and IL-6 on oxytocin secretion in human uterine smooth muscle cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001;46(3):226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menon R, Richardson LS, Lappas M. Fetal membrane architecture, aging and inflammation in pregnancy and parturition. Placenta. 2019;79:40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gomez-Lopez N, Laresgoiti-Servitje E, Olson DM, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Vadillo-Ortega F. The role of chemokines in term and premature rupture of the fetal membranes: a review. Biol Reprod. 2010;82(5):809–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Menon R, Fortunato SJ. Infection and the role of inflammation in preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(3):467–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi SJ, Oh S, Kim JH, Roh CR. Changes of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in human myometrium before and during term labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132(2):182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allport VC, Slater DM, Newton R, Bennett PR. NF-kappaB and AP-1 are required for cyclo-oxygenase 2 gene expression in amnion epithelial cell line (WISH). Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(6):561–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khanjani S, Kandola MK, Lindstrom TM, Sooranna SR, Melchionda M, Lee YS, Terzidou V, Johnson MR, Bennett PR. NF-kappaB regulates a cassette of immune/inflammatory genes in human pregnant myometrium at term. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(4):809–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindstrom TM, Bennett PR. The role of nuclear factor kappa B in human labour. Reproduction. 2005;130(5):569–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Allport VC, Pieber D, Slater DM, Newton R, White JO, Bennett PR. Human labour is associated with nuclear factor-kappaB activity which mediates cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression and is involved with the ‘functional progesterone withdrawal.’ Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7(6):581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haddad R, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Mazor M, Romero R. Human spontaneous labor without histologic chorioamnionitis is characterized by an acute inflammation gene expression signature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):394 e391-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li R, Ackerman WEt, Summerfield TL, Yu L, Gulati P, Zhang J, Huang K, Romero R, Kniss DA. Inflammatory gene regulatory networks in amnion cells following cytokine stimulation: translational systems approach to modeling human parturition. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee Y, Allport V, Sykes A, Lindstrom T, Slater D, Bennett P. The effects of labour and of interleukin 1 beta upon the expression of nuclear factor kappa B related proteins in human amnion. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9(4):213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bukowski R, Sadovsky Y, Goodarzi H, Zhang H, Biggio JR, Varner M, Parry S, Xiao F, Esplin SM, Andrews W, et al. Onset of human preterm and term birth is related to unique inflammatory transcriptome profiles at the maternal fetal interface. PeerJ. 2017;5: e3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan C, Johnson PF, Tang H, Ye Y, Wu M, Gao H. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta is a critical mediator of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(2):420–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slofstra SH, Groot AP, Obdeijn MH, Reitsma PH, ten Cate H, Spek CA. Gene expression profiling identifies C/EBPdelta as a candidate regulator of endotoxin-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sivarajasingam SP, Imami N, Johnson MR. Myometrial cytokines and their role in the onset of labour. J Endocrinol. 2016;231(3):R101–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peltier MR. Immunology of term and preterm labor. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1: 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Caivano M, Gorgoni B, Cohen P, Poli V. The induction of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in macrophages is biphasic and requires both CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBP beta ) and C/EBP delta transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(52):48693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gout J, Tirard J, Thevenon C, Riou JP, Begeot M, Naville D. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) regulate the basal and cAMP-induced transcription of the human 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase encoding gene in adipose cells. Biochimie. 2006;88(9):1115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hungness ES, Luo GJ, Pritts TA, Sun X, Robb BW, Hershko D, Hasselgren PO. Transcription factors C/EBP-beta and -delta regulate IL-6 production in IL-1beta-stimulated human enterocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(1):64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas B, Berenbaum F, Humbert L, Bian H, Bereziat G, Crofford L, Olivier JL. Critical role of C/EBPdelta and C/EBPbeta factors in the stimulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene transcription by interleukin-1beta in articular chondrocytes. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(23):6798–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Challis JR, Sloboda DM, Alfaidy N, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Patel FA, Whittle WL, Newnham JP. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction. 2002;124(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li WJ, Lu JW, Zhang CY, Wang WS, Ying H, Myatt L, Sun K. PGE2 vs PGF2alpha in human parturition. Placenta. 2021;104:208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]