Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha factor (LITAF), also called p53-induced gene 7 (PIG7), was identified as a transcription factor that activates transcription of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Previous studies have identified LITAF as a potential tumor suppressor in several neoplasms, including prostate cancer, B-NHL, acute myeloid leukemia, and pancreatic cancer. However, the expression and function of LITAF in human glioma remain unexplained. The present study aimed to analyze the regulation of LITAF in gliomas. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database revealed that LITAF mRNA expression in glioma tissues was higher than that in normal brain tissues, and lower LITAF expression in gliomas showed a good prognosis in patients who received radiotherapy, by Kaplan–Meier analysis. In our collected specimens, however, LITAF showed low expression in glioma tissues compared to that in the normal brain tissue. Proliferation and apoptosis of glioma cells were not affected by knockdown or overexpression of LITAF in glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells, but LITAF was able to enhance the radiosensitivity of glioma cells. Furthermore, we found that LITAF enhanced radiosensitivity via FoxO1 and its specific downstream targets BIM, TRAIL, and FASLG. Taken together, our present results demonstrate that LITAF expression is decreased in glioma tissues and might enhance radiosensitivity of glioma cells via upregulation of the FoxO1 pathway.

Keywords: LITAF, FoxO1, Glioma, Radiosensitivity, Proliferation, Apoptosis

Introduction

Gliomas represent 75% of malignant primary brain tumors and are the most common malignant tumors of the central nervous system in adults. The 2016 WHO classification system categorizes gliomas into circumscribed gliomas (WHO grade I) and diffusely infiltrating gliomas (WHO grades II–IV; including both astrocytic and oligodendroglial) based on their growth pattern and the presence or absence of IDH mutations. Most circumscribed gliomas are benign resectable lesions. Conversely, diffusely infiltrating gliomas are difficult to cure by resection alone. Among them, more than half are glioblastomas (GBM, WHO grade IV), which are the most malignant glioma tumors. The annual incidence of glioblastomas is about 3–4 cases per 100,000 individuals (Lapointe et al. 2018; Louis et al. 2016; Ostrom et al. 2017; Schijns et al. 2018; Wesseling and Capper 2018). At present, maximum surgical resection and adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the main treatment methods for glioblastomas, but the biological characteristics of highly invasive growth and resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy of glioma cells often result to recurrence in most patients with glioma. The median survival time is only 14.6 months, with death mostly due to cerebral edema or increased intracranial pressure in patients with GBM (Agnihotri et al. 2013; Gallego 2015). Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of this disease is critical to new therapeutic strategies.

Lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-α factor (LITAF) exists in various tissues and functions as a transcription factor. In the inflammatory response, LITAF may interact with STAT6B and form a complex to activate transcription of inflammatory cytokine genes, such as those encoding TNF-α, IL-6, and CXCL16 in macrophages in response to LPS (Tang et al. 2005, 2006, 2010). The expression of LITAF is increased in intestinal tissues from patients with inflammatory bowel disease and may be related to the development of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis by activating transcription of genes encoding inflammatory factors (Stucchi et al. 2006). It has also been suggested to be correlated with the incidence of osteoarthritis (Merrill et al. 2011). LITAF was also characterized as p53-inducible gene 7 (PIG7), because of the fact that it is positively regulated by the tumor suppressor gene p53 (Polyak et al. 1997). In the following years, many studies highlighted LITAF as a tumor suppressor which inhibited cell growth and promoted apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (Polyak et al. 1997), acute myeloid leukemia (Wang et al. 2009), B-cell lymphoma (Bertolo et al. 2013; Mestre-Escorihuela et al. 2007), and pancreatic cancer (Zhou et al. 2018). Moreover, LITAF was recognized to be a novel target of miR-106a, and its knockdown recapitulates miR-106a-induced radioresistance in prostate cancer cells (Hoey et al. 2018).

Until now, the expression and function of LITAF in human gliomas remain unexplained. We chose glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells to explore the effect of LITAF expression on proliferation, apoptosis, and radiosensitivity of glioma cells. The experimental results showed that low expression or overexpression of LITAF did not influence the proliferation and apoptosis of glioma U251, U87, U373 cells, but LITAF could enhance the radiosensitivity of glioma U251 and U373 cells. Moreover, we found that LITAF enhanced radiosensitivity of human glioma cells via the FoxO1/Bim-TRAIL-FASLG pathway.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Tissue Samples

U251, U373, and U87 glioma cell lines (Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and incubated in a 37 °C cell culture incubator containing 5% CO2. Tissue specimens were collected from the Department of Pathology, Xinqiao Hospital. Fifty-seven glioma specimens and ten normal brain tissues were pathologically diagnosed. This experiment was approved by the Xinqiao Hospital Ethics Committee. All tissue specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen for further analysis.

TCGA Data Analyses

Analysis of LITAF expression in normal brain tissue and glioma tissue was performed using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) online database (http://firebrowse.org). In order to obtain these data from the database, one must enter “LITAF” in the search box and click “View,” then, click “Filter on” to check “GBLGG” (glioblastoma and low-grade glioma). The effect of LITAF expression on the prognosis of glioma patients who received radiotherapy was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier. Expression data and clinical information of 630 glioma patients were downloaded from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). Of these, 404 samples were from patients who received radiotherapy. The order was sorted from low to high according to LITAF mRNA expression, such that the first 202 samples comprised the low expression group and the remaining samples comprised the high expression group.

Cell Transfection

Lentiviral vectors for overexpression of LITAF (NM_004862) and knockout of LITAF (CCA UUU UCU GUA AUC AAA UGA) were purchased from Shanghai Genechem Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). Blank lentiviral vector was used as a control. Cell transfection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After 72 h of transfection, medium containing puromycin (6 μg/ml) was added for cell selection. After about 10 days of selection, stable transfected cells were cultured with normal medium.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from cells and frozen tissues was extracted using RNAiso Plus (Takara). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by reverse transcription of 1 μg total RNA using PrimeScript RT reagent (Takara), and the PCR-amplified sequence was detected by the ABI 7500 Prism System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 5 s, 40 cycles, and 60 °C for 34 s. The expression of β-ACTIN was used as a reference for relative expression. Quantitative real-time PCR primers were as follows: β-ACTIN, forward: 5′-GTG AAG GTG ACA GCA GTC GGT T-3′, reverse: 5′-GAA GTG GGG TGG CTT TTA GGA-3′; and LITAF, forward: 5′-ATG TCG GTT CCA GGA CCT TAC-3′, reverse: 5′-TACG AAG GAG GAT TCA TGC CC-3′. To further analyze the mRNA expression of stably transfected cells after ionizing radiation, total RNA was isolated from stably transfected U251 and U373 cells using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa) at 48 h after irradiation. cDNA synthesis and amplification conditions were the same as those described above. Gene-specific primers were as follows: FoxO1, forward: 5′-TCG TCA TAA TCT GTC CCT ACA CA-3′, reverse: 5′-CGG CTT CGG CTC TTA GCA AA-3′; TRAIL, forward: 5′-TGC GTG CTG ATC GTG ATC TTC-3′, reverse: 5′-GCT CGT TGG TAA AGT ACA CGT A-3′; FASLG, forward: 5′-ATT TAA CAG GCA AGT CCA ACT CA-3′, reverse: 5′-GGC CAC CCT TCT TAT ACT TCA CT-3′; and BIM, forward: 5′-TAA GTT CTG AGT GTG ACC GAG A-3′, reverse: 5′- GCT CTG TCT GTA GGG AGG TAG G -3′.

Western Blotting Analysis

Whole frozen tissues and stably transfected cells were gathered and lysed in RIPA Lysis Buffer (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) containing 1% protease inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) on ice for 10 min. After separation by 10% SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Roche Group, Switzerland), blocked with 5% BSA (Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated overnight with the specific primary antibody. The blots were detected with BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China), after incubating with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. For western blot analysis of stably transfected cells after ionizing radiation, total proteins were collected from stably transfected U251 and U373 cells at 48 h after irradiation. The method of western blot analysis was the same as mentioned above. Primary antibodies were as follows: mouse monoclonal anti-β-ACTIN (dilution 1:1000; BOSTER, BM0627), rabbit polyclonal anti-LITAF (dilution 1:1000; Proteintech Group, Inc; 16797-I-AP), rabbit polyclonal anti-FoxO1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. 2880S), rabbit polyclonal anti-TRAIL (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. 3219S), rabbit polyclonal anti-FASLG (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. 4273S), and rabbit polyclonal anti-BIM (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. 2933S).

Proliferation Assays

The proliferation of stably transfected cells was assessed using iClick™ EdU Andy Fluor™ 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (GeneCopoeia, USA). The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells per well with the normal medium for 24 h, then all cells were cultured in medium treated with 30 μmol/ml EdU for 6 h and detected according to the recommended staining protocol. The flow cytometry assay was performed according to the assay kit instructions. The data were analyzed using software Flowjo_V10 (Treestar Inc. USA).

Cell Irradiation

Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 culture flasks (2 × 105 cells/flask) with 10 ml DMEM medium containing 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. After the cells attached, sealing film was used to seal the bottle cap and venting hole. The flasks were then sterilized with 75% alcohol. Next, the cells were irradiated with a 6-MeV electron ray from a linear accelerator (Varian Trilogy, USA). After irradiation, the culture flasks were sterilized again with 75% alcohol, then the sealing film was torn off. Then cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for further analysis. For the irradiation conditions, the treatment room was sterilized by ultraviolet light for 30 min before irradiation at room temperature. Cells were irradiated by a 6-MeV electron ray. The dose rate was 300 Mu/min, the source-skin distance was 100 cm, and the radiation field was 25 cm × 25 cm. The depth of the culture medium was 5 mm (10 ml medium), and the 1-cm-thick tissue equivalent compensation block was placed under the culture bottle. The dose schedule was calculated by a physicist in the Eclipse radiotherapy planning system.

Apoptosis Assay

Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 culture flasks (2 × 105 cells/flask) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All the cells were washed in PBS and stained using an Annexin V-PE/7-AAD apoptosis kit (BD Biosciences, Inc. USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Apoptosis was assayed using a Beckman CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc. USA) and analyzed using software Flowjo_V10 (Treestar Inc. USA). In order to measure apoptosis of stably transfected cells after ionizing radiation, cells were seeded in 25 cm2 culture flasks (2 × 105 cells/flask), exposed to 13 Gray irradiation after adhesion, and then incubated for 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, all cells were harvested to assay apoptosis as described above.

Clonogenic Assay

After 7 Gray irradiation, cells were plated in six-well plates at 2 × 103 cells per well and incubated for 10–14 days at 37 °C in 5% CO2 until colonies containing at least 50 cells were formed. Cells were stained with hematoxylin. The surviving fraction was calculated as follows: (number of colonies formed)/(total number of cells plated × plating efficiency).

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis of results. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed distribution unpaired Student t-tests. All histograms are presented as mean ± SEM. Results were considered significantly different at p < 0.05.

Results

LITAF Expression in Glioma Tissues

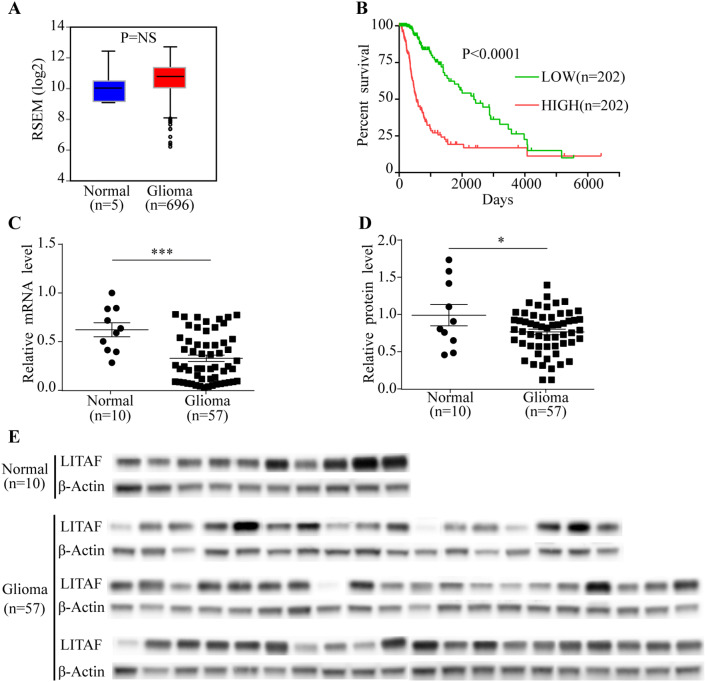

To explore the role of LITAF in gliomas, we analyzed the LITAF mRNA expression of gliomas in the TCGA database. The mRNA levels of LITAF in glioma tissues were elevated compared to that in normal tissues, but no significant difference (P = NS) (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, according to Kaplan–Meier analysis using the TCGA database, lower LITAF expression showed a good prognosis in glioma patients who received radiation therapy relative to those with high LITAF expression (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b). Contrary to other neoplasms, these results suggested that LITAF might act as an oncogene in gliomas. Therefore, we further examined the mRNA and protein levels of LITAF in glioma and normal brain tissues that we collected, using qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Interestingly, the mRNA levels of LITAF were decreased in 57 glioma tissue samples compared to that in 10 samples of non-tumor brain tissues (P = 0.0008) (Fig. 1c). The results of western blotting also showed lower LITAF protein levels in glioma tissues than in non-tumor brain tissues (P = 0.0404) (Fig. 1d, e). This distinct conclusion sparked a great interest in the role of LITAF in glioma cells in our research group.

Fig. 1.

Expression of LITAF in human glioma tissues. a LITAF mRNA expression in normal brain specimens and glioma specimens, data from TCGA database. P = NS. b Kaplan–Meier analysis of glioma patients with different expression levels of LITAF after receiving radiation therapy. Clinical data were from the TCGA database. c Expression of LITAF mRNA in normal brain tissue and glioma tissue samples. P = 0.0008. d Statistical results of LITAF protein expression in tissues. P = 0.0404. e Expression of LITAF detected by western blotting in normal brain tissues and glioma tissues. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (mean ± SEM, Student’s t-test). Normal: normal brain tissues. Glioma: glioma tissues

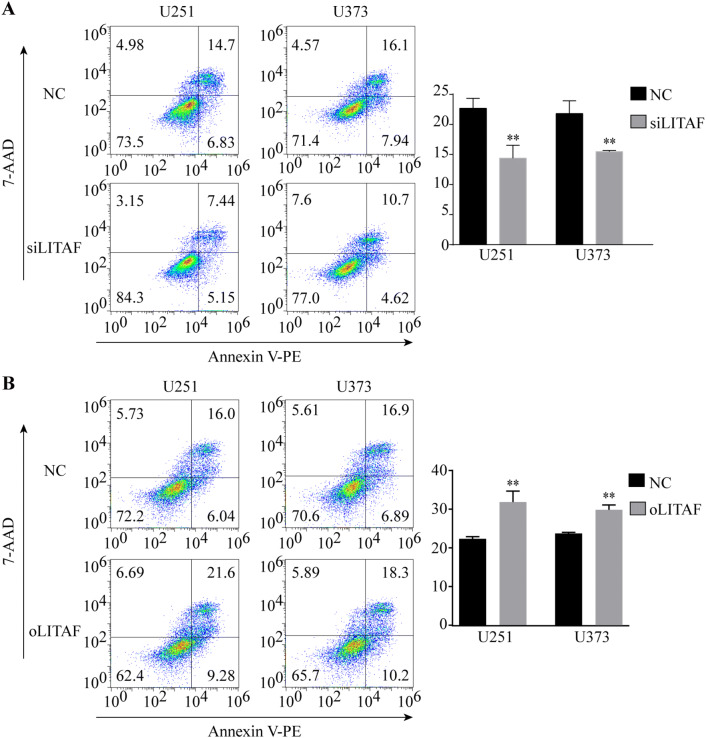

LITAF Expression did not Influence the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Glioma Cells

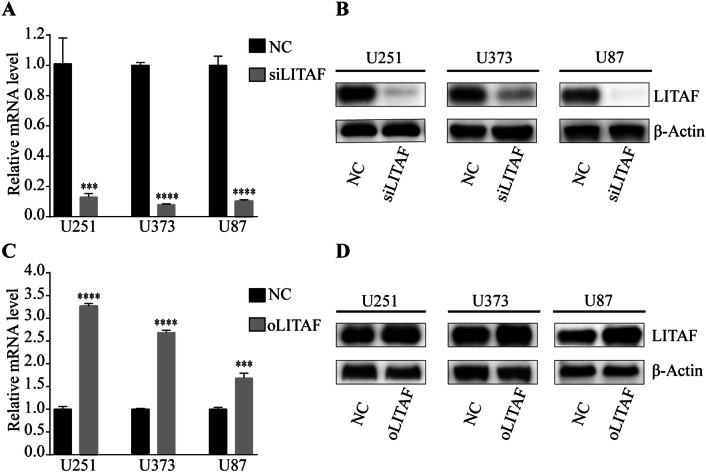

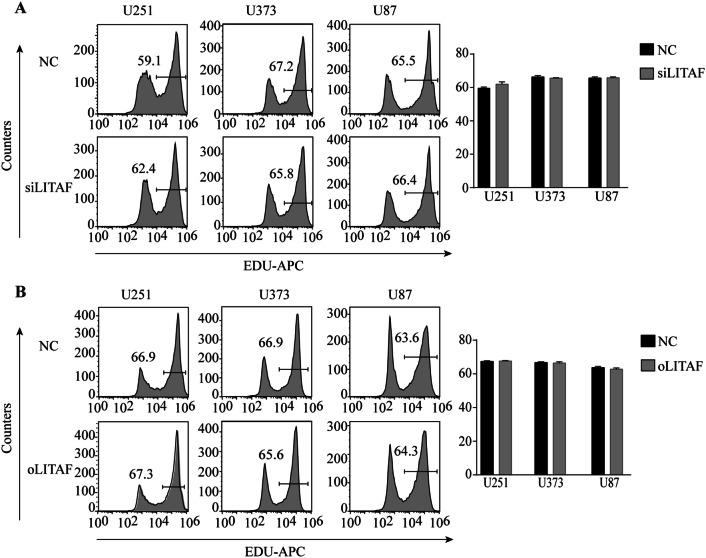

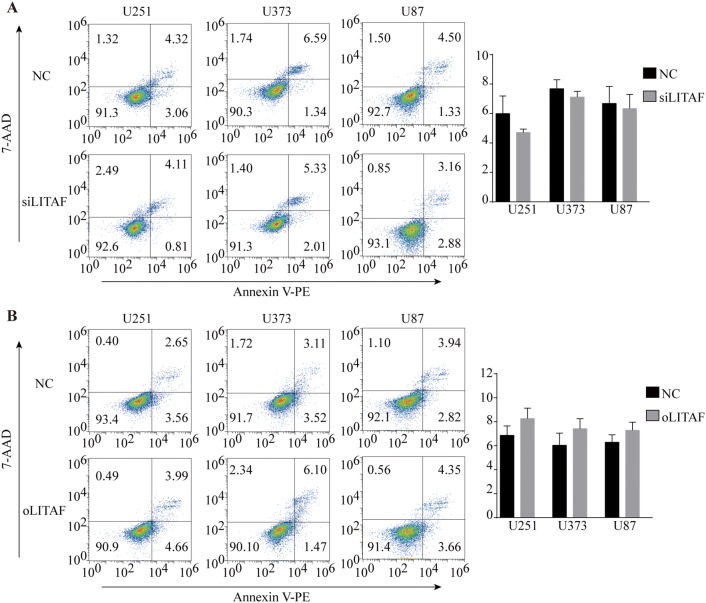

To explore the role of LITAF in glioma cells, we overexpressed or suppressed LITAF via lentiviral vector in glioma U251, U373, and U87 cell lines. The effective knockdown and overexpression of LITAF were confirmed by qPCR and western blotting. Compared with that in the negative control cells, LITAF-overexpressing vector (oLITAF)-transfected cells showed high LITAF expression, while LITAF-knockdown vector (siLITAF)-transfected cells showed significantly reduced LITAF expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a–d). Cell proliferation and apoptosis were then assessed in these stably transfected cells. EDU assays showed that the proliferation of glioma cells was not influenced by siLITAF compared with that in the negative control (NC) group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Similarly, cell proliferation was not influenced in the oLITAF group compared with that in the NC group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3b). Flow cytometry assays revealed that compared to that in the NC group, siLITAF did not inhibit apoptosis (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4a), and the same results were observed in the LITAF overexpression group compared with those in the NC group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results indicated that the expression of LITAF did not influence the proliferation and apoptosis of glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells.

Fig. 2.

Transfection efficiency of glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells after exogenously altering LITAF expression. (a, c) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of LITAF mRNA expression in stably transfected U251, U373, and U87 cells (P < 0.05). (b, d) Protein levels of LITAF in stably transfected U251, U373, and U87 cells (P < 0.05). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.001 (mean ± SEM). NC group versus siLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group versus oLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

Fig. 3.

Proliferation of glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells after exogenously altering LITAF expression. a Flow cytometry results of EDU-stained U251, U373, and U87 cells transfected with control lentiviral vector or LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector (P > 0.05). b Cell proliferation in U251, U373, and U87 cells with or without LITAF overexpression assessed by EDU (P > 0.05). NC group versus siLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group versus oLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

Fig. 4.

Apoptosis of glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells after exogenously altering LITAF expression. a Cell apoptosis analyzed by apoptosis kit staining and flow cytometry in U251, U373, and U87 cells with or without LITAF-knockdown (P > 0.05). b Cell apoptosis analyzed by flow cytometry in U251, U373, and U87 cells with or without LITAF overexpression (P > 0.05). NC group vs siLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group vs oLITAF group, NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

LITAF Enhanced Radiosensitivity of Glioma U251 and U373 Cells

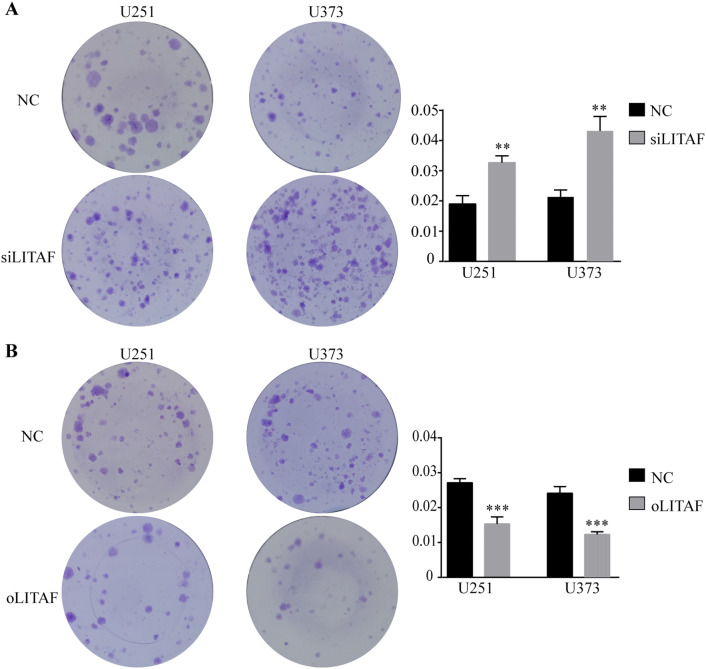

Although the expression of LITAF did not have a statistically significant effect on the apoptosis of glioma cells, the number of apoptotic cells increased with increasing LITAF expression. The survival time showed significant differences in glioma patients with different expression levels of LITAF who received radiotherapy in the TCGA database. Additionally, LITAF knockdown has been shown to recapitulate miR-106a-induced radioresistance in prostate cancer cells (Hoey et al. 2018). Since radiotherapy is a common adjuvant therapy for patients with glioma, we suspected that this gap would increase further after encountering external stimuli such as irradiation. Because glioma U87 cells exhibited strong radioresistance in previous experiments, we chose U251 and U373 cells to verify this hypothesis. Apoptosis assessments by flow cytometry showed that compared to that in the NC group, knockdown of LITAF expression decreased the pro-apoptotic effects of ionizing radiation (IR) on glioma U251 and U373 cells that received 13 Gray irradiation (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a). In contrast, more apoptotic cells were found in LITAF-overexpressing group than in NC group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5b). Colony formation assays were then performed after seven Gray irradiation. Compared to that in the NC group, LITAF-knockdown group was resistant to IR, and the apoptosis in the LITAF-overexpressing group remarkably increased after IR compared to that in the NC group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6a, b). These results indicated that LITAF expression was able to enhance radiosensitivity of glioma U251 and U373 cells.

Fig. 5.

Apoptosis of glioma U251 and U373 cells with exogenously altered LITAF expression after receiving 13 Gray irradiation. a Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF knockdown receiving 13 Gray irradiation. b Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF overexpression after receiving 13 Gray irradiation. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01, (mean ± SEM). NC group vs siLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group vs oLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

Fig. 6.

Colony formation assays of glioma U251 and U373 cells with exogenously altered LITAF expression after receiving 7 Gray irradiation a Cloning efficiency of U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF knockdown after 7 Gray irradiation. b Cloning efficiency of U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF overexpression after 7 Gray irradiation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (mean ± SEM). NC group vs siLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group vs oLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

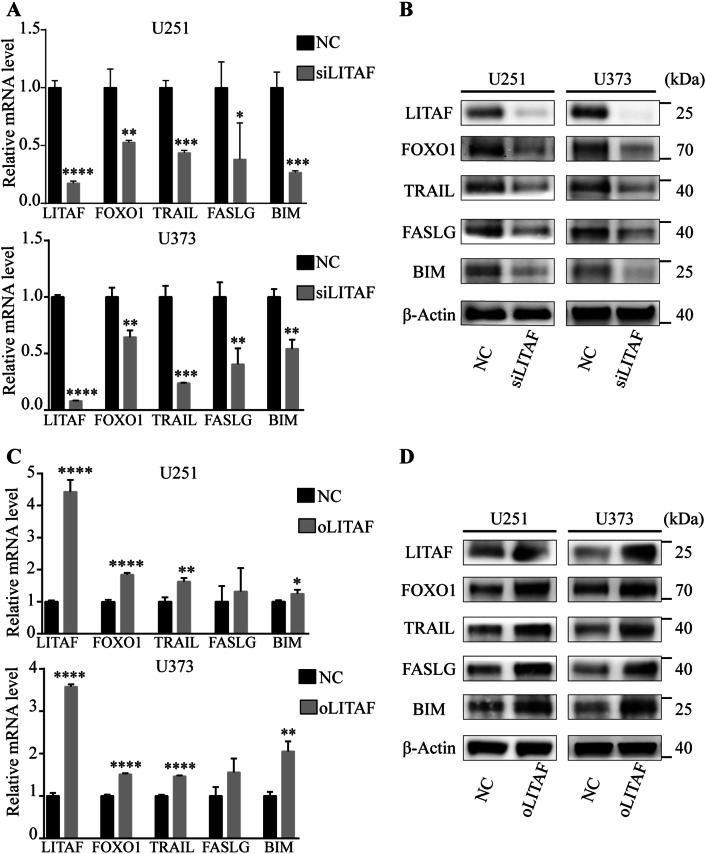

LITAF Enhanced Radiosensitivity of Human Glioma U251 and U373 Cells via the FoxO1 Pathway

LITAF is well known for its role as a transcriptional regulator of TNF-α (Zou et al. 2015). TNF-α is a pleiotropic cytokine that stimulates a large variety of events in many cell types. TNF-α exerts its biological activity by activating several different signaling pathways that can affect diverse functions such as inflammation, survival, or cell death. Among them, TNF-α activates pro-apoptotic factor FoxO1 (Alikhani et al. 2005; Kayal et al. 2010). Then, FoxO1 induces apoptosis through its specific downstream targets Bim, TRAIL, and FASLG (Gilley et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2011). Therefore, we selected the FoxO1 pathway components as candidate targets of LITAF. To determine whether LITAF enhances radiosensitivity of human glioma U251 and U373 cells via the FoxO1 pathway, the expression of FoxO1 and its specific downstream targets Bim, TRAIL, and FASLG were analyzed individually by qPCR and western blotting in glioma U251 and U373 cells that received ionizing radiation. The results showed that as the expression of LITAF increased, the expression of FoxO1 and its downstream targets Bim, TRAIL, and FASLG also increased in U251 and U373 cells that received ionizing radiation (Fig. 7a–d). These results suggested that LITAF may enhance radiosensitivity of human glioma cells via activation of the FoxO1 pathway.

Fig. 7.

LITAF enhanced radiosensitivity of glioma U251 and U373 Cells via FoxO1 pathway. a The relative mRNA levels of LITAF, FoxO1, TRAIL, FASLG, and BIM in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF knockdown after receiving ionizing radiation. b Western blotting analysis of LITAF, FoxO1, TRAIL, FASLG, and BIM in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF knockdown after receiving ionizing radiation. c Relative mRNA levels of LITAF, FoxO1, TRAIL, FASLG, and BIM in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF overexpression after receiving ionizing radiation. d Western blotting analysis of LITAF, FoxO1, TRAIL, FASLG, and BIM in U251 and U373 cells with or without LITAF overexpression after receiving ionizing radiation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 (mean ± SEM). NC group vs siLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. siLITAF: LITAF-knockdown lentiviral vector-infected cells. NC group vs oLITAF group. NC: negative lentiviral vector-infected cells. oLITAF: LITAF-overexpressing lentiviral vector-transfected cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell types

Discussion

LITAF is located on chromosome 16 and encodes a 23.9 kDa protein containing 228 amino acids (Zou et al. 2015). LITAF was originally termed p53-inducible gene 7, because the protein encoded by LITAF could be regulated by the tumor suppressor protein p53 (Polyak et al. 1997). It is widely expressed in human tissues, including the spleen, lymph nodes, peripheral blood leukocytes, and so on (Myokai et al. 1999). LITAF can form a complex with STAT6B under the stimulation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and jointly regulates the expression of TNF-α, IL-10, and other inflammatory factors which play an important role in normal inflammatory responses (Tang et al. 2005). A collection of studies have recently pointed out that LITAF might be a potential tumor suppressor, inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis in many tumors. Zhou et al. promoted the viewpoint that LITAF inhibits the proliferation of prostate cancer cells by regulating TNFSF15 (Zhou et al. 2011). Meanwhile, Zhou et al. found that methylation of the LITAF promoter was prevalent in pancreatic cancer tissues and reduced LITAF expression. Demethylation of the LITAF promoter could inhibit the proliferation and apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells (Zhou et al. 2018). Hoey et al. found that prostate cancer cells with low LITAF expression showed resistance to radiation therapy (Hoey et al. 2018). Wang et al. analyzed promoter methylation status of the LITAF gene in 105 paraffin specimens of B-cell lymphoma, and found that the frequency of LITAF gene methylation in B-cell lymphoma was 89.5%. LITAF gene silencing with aberrant CpG methylation may be one of the most critical events in the oncogenesis of B-cell lymphoma (Wang et al. 2014a).

In our previous study, we found that inhibition of LITAF led to a decrease in the number of radiation-induced apoptotic cells, but the mechanism remained unclear. Thus, we performed these trial experiments to explore this underlying mechanism. First, we analyzed the TCGA database and found that although the mRNA levels of LITAF in glioma tissues were increased compared to those in normal tissues, there was no statistical difference. Meanwhile, lower LITAF expression in glioma patients who received radiotherapy indicated a good prognosis. The results suggest that LITAF may be a potential poor prognostic indicator in glioma patients. To further verify this result, we collected 57 glioma tissues to analyze their LITAF expression. Surprisingly, the LITAF expression was decreased in glioma tissues compared with that in normal brain tissues. The question then arose: what is the real role of LITAF? Nevertheless, this contrasting result prompted us to explore the biological role of LITAF in gliomas. Subsequently, LITAF expression was exogenously altered in glioma U251, U373, and U87 cells. The proliferation and apoptosis of the three cell lines were not influenced after LITAF knockdown, compared to that in negative control cells. The same results were confirmed in overexpression group. Although there were no statistical differences in the apoptosis results, the number of apoptotic cells gradually increased with increasing LITAF expression in glioma cells. These results implied that LITAF does not associate intensively with the regulation of proliferation in glioma cells, but might participate in the regulation of apoptosis in glioma cells. Radiotherapy is a common adjuvant treatment for glioma patients, and the Kaplan–Meier analysis of the results of the gliomas patients who received radiotherapy in TCGA database showed that LITAF expression affected the prognosis of the patients with glioma. We hypothesized whether ionizing radiation could further expand this difference. Then, we chose glioma U251 and U373 cells to verify this conjecture. The apoptosis assessment by flow cytometry and colony formation assays showed that LITAF indeed enhanced radiosensitivity of glioma U251 and U373 cells. The apoptosis of glioma cells that received irradiation increased significantly and cloning efficiency decreased markedly when LITAF expression increased. DNA damage resulting in apoptosis was the dominant effect of irradiation to cells. These results indicated that LITAF may be involved in apoptotic regulation of glioma cells treated with ionizing radiation.

FoxO1 belongs to the Forkhead box O (FoxO) transcription factor family, which has four subtypes in humans: FoxO1, FoxO3, FoxO4, and FoxO6. FoxO proteins are associated with oxidative stress, cell differentiation, apoptosis, proliferation, and DNA repair (Jiang et al. 2018). FoxO1 is a major target protein for activated P13 K/AKT signaling, which regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and DNA repair (Zhao et al. 2016). FoxO1 has tumor suppressive effects and is associated with the regulation of proliferation and angiogenesis in several tumor cells and its expression is diminished or deleted in a variety of tumors, such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Xie et al. 2012), breast cancer (Wu et al. 2012), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (Bois et al. 2005), and GBM (Yan and Wu 2018). In the regulation of apoptosis, several studies demonstrated that pro-apoptotic FOXO1 can be activated by TNF-α, inducing insulin resistance and delaying wound healing in diabetic patients (Alikhani et al. 2005; Ito et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2014b; Zheng et al. 2011). LITAF is known for its ability to regulate TNF-α (Myokai et al. 1999). Therefore, we assumed that LITAF enhanced the radiosensitivity and induced the apoptosis of glioma cells through FoxO1. Western blot and qPCR assays were performed in glioma U251 and U373 cells after ionizing radiation. Interestingly, the results showed that the mRNA and protein levels of FoxO1 expression were related to those of LITAF. It has been reported that FoxO1 regulates cell apoptosis by its specific downstream targets including Fas ligand, Bim, or TRAIL (Zhang et al. 2011). Hence, we continued to analyze the specific downstream targets of FOXO1. The results showed that the expression of Bim, TRAIL, and FASLG were also consistent with LITAF expression in glioma U251 and U373 cells that received ionizing radiation. These results revealed that LITAF might enhance radiosensitivity of glioma cells via the FoxO1 signaling pathway.

Taken together, our data showed that LITAF could improve the radiosensitivity of human glioma U251 and U373 cells. The activation of LITAF stimulates expression of FoxO1 and its downstream targets Bim, TRAIL, and FASLG in glioma U251 and U373 cells that received ionizing radiation. LITAF might enhance radiosensitivity of glioma cells via upregulation of the FoxO1 pathway. More work is needed to elucidate the mechanism underlying this regulation.

Author Contributions

CH, DC, and HZ performed the experiments and analyzed the data. SL and QL provided the human specimen. CH and GL wrote the paper. DC and GL designed the research.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81372408).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest for this manuscript.

Ethics Approval

All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of The Xinqiao Hospital, Chongqing 40037, China (No. AF/SC-08/1.0). All procedures performed in studies involving human specimen were in accordance with the ethical standards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agnihotri S, Burrell KE, Wolf A, Jalali S, Hawkins C, Rutka JT, Zadeh G (2013) Glioblastoma, a brief review of history, molecular genetics, animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 61:25–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhani M, Alikhani Z, Graves DT (2005) FOXO1 functions as a master switch that regulates gene expression necessary for tumor necrosis factor-induced fibroblast apoptosis. J Biol Chem 280:12096–12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolo C, Roa S, Sagardoy A, Mena-Varas M, Robles EF, Martinez-Ferrandis JI, Sagaert X, Tousseyn T, Orta A, Lossos IS, Amar S, Natkunam Y, Briones J, Melnick A, Malumbres R, Martinez-Climent JA (2013) LITAF, a BCL6 target gene, regulates autophagy in mature B-cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol 162:621–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois PRJ, Izeradjene K, Houghton PJ, Cleveland JL, Houghton JA, Grosveld GC (2005) FOXO1a acts as a selective tumor suppressor in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. J Cell Biol 170:903–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gallego O (2015) Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr Oncol 22:e273–e281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J (2003) FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol 162:613–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey C, Ray J, Jeon J, Huang X, Taeb S, Ylanko J, Andrews DW, Boutros PC, Liu SK (2018) miRNA-106a and prostate cancer radioresistance: a novel role for LITAF in ATM regulation. Mol Oncol 12:1324–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Daitoku H, Fukamizu A (2009) Foxo1 increases pro-inflammatory gene expression by inducing C/EBPbeta in TNF-alpha-treated adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 378:290–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Li T, Yang Z, Hu W, Yang Y (2018) Deciphering the roles of FOXO1 in human neoplasms. Int J Cancer 143(7):1560–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayal RA, Siqueira M, Alblowi J, McLean J, Krothapalli N, Faibish D, Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC, Graves DT (2010) TNF-α mediates diabetes-enhanced chondrocyte apoptosis during fracture healing and stimulates chondrocyte apoptosis Through FOXO1. J Bone Miner Res 25:1604–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe S, Perry A, Butowski NA (2018) Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet 392:432–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JC, You J, Constable C, Leeman SE, Amar S (2011) Whole-body deletion of LPS-induced TNF-alpha factor (LITAF) markedly improves experimental endotoxic shock and inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:21247–21252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestre-Escorihuela C, Rubio-Moscardo F, Richter JA, Siebert R, Climent J, Fresquet V, Beltran E, Agirre X, Marugan I, Marin M, Rosenwald A, Sugimoto KJ, Wheat LM, Karran EL, Garcia JF, Sanchez L, Prosper F, Staudt LM, Pinkel D, Dyer MJS, Martinez-Climent JA (2007) Homozygous deletions localize novel tumor suppressor genes in B-cell lymphomas. Blood 109:271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myokai F, Takashiba S, Lebo R, Amar S (1999) A novel lipopolysaccharide-induced transcription factor regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression: molecular cloning, sequencing, characterization, and chromosomal assignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:4518–4523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Vecchione-Koval T, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2017) CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol 19:v1–v88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (1997) A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature 389:300–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schijns V, Pretto C, Strik AM, Gloudemans-Rijkers R, Deviller L, Pierre D, Chung J, Dandekar M, Carrillo JA, Kong XT, Fu BD, Hsu F, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Zidovetzki R, Bota DA, Stathopoulos A (2018) Therapeutic Immunization against glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci 19:2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucchi A, Reed K, O’Brien M, Cerda S, Andrews C, Gower A, Bushell K, Amar S, Leeman S, Becker J (2006) A new transcription factor that regulates TNF-alpha gene expression, LITAF, is increased in intestinal tissues from patients with CD and UC. Inflamm Bowel Dis 12:581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Marciano DL, Leeman SE, Amar S (2005) LPS induces the interaction of a transcription factor, LPS-induced TNF-alpha factor, and STAT6(B) with effects on multiple cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:5132–5137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Metzger D, Leeman S, Amar S (2006) LPS-induced TNF-alpha factor (LITAF)-deficient mice express reduced LPS-induced cytokine: evidence for LITAF-dependent LPS signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:13777–13782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Woodward T, Amar S (2010) A PTP4A3 peptide PIMAP39 modulates TNF-alpha levels and endotoxic shock. J Innate Immun 2:43–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Liu J, Tang K, Xu Z, Xiong X, Rao Q, Wang M, Wang J (2009) Expression of pig7 gene in acute leukemia and its potential to modulate the chemosensitivity of leukemic cells. Leuk Res 33:28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shi Y, Wang L, Ren G, Bai Y, Shi H, Zhang X, Jiang X, Zhou R (2014a) Significance of expression and promoter methylation of LITAF gene in B-cell lymphoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 43:516–521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XW, Yu Y, Gu L (2014b) Dehydroabietic acid reverses TNF-alpha-induced the activation of FOXO1 and suppression of TGF-beta1/Smad signaling in human adult dermal fibroblasts. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7:8616–8626 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling P, Capper D (2018) WHO 2016 classification of gliomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 44:139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Elshimali Y, Sarkissyan M, Mohamed H, Clayton S, Vadgama JV (2012) Expression of FOXO1 is associated with GATA3 and Annexin-1 and predicts disease-free survival in breast cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2:104–115 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Ushmorov A, Leithauser F, Guan H, Steidl C, Farbinger J, Pelzer C, Vogel MJ, Maier HJ, Gascoyne RD, Moller P, Wirth T (2012) FOXO1 is a tumor suppressor in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 119:3503–3511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Wu A (2018) FOXO1 is crucial in glioblastoma cell tumorigenesis and regulates the expression of SIRT1 to suppress senescence in the brain. Mol Med Rep 17:2535–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gan B, Liu D, Paik J (2011) FoxO family members in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 12:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Luo R, Liu Y, Gao L, Fu Z, Fu Q, Luo X, Chen Y, Deng X, Liang Z, Li X, Cheng C, Liu Z, Fang W (2016) miR-3188 regulates nasopharyngeal carcinoma proliferation and chemosensitivity through a FOXO1-modulated positive feedback loop with mTOR–p-PI3 K/AKT-c-JUN. Nat Commun 7:11309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Zou J, Wang W, Feng X, Shi Y, Zhao Y, Jin G, Liu Z (2011) Tumor necrosis factor-α increases angiopoietin-like protein 2 gene expression by activating Foxo1 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 339:120–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Yang Z, Tsuji T, Gong J, Xie J, Chen C, Li W, Amar S, Luo Z (2011) LITAF and TNFSF15, two downstream targets of AMPK, exert inhibitory effects on tumor growth. Oncogene 30:1892–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Huang J, Yu X, Jiang X, Shi Y, Weng Y, Kuai Y, Lei L, Ren G, Feng X, Zhong G, Liu Q, Pan H, Zhang X, Zhou R, Lu C (2018) LITAF is a potential tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 9:3131–3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Guo P, Lv N, Huang D (2015) Lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha factor enhances inflammation and is associated with cancer. Mol Med Rep 12:6399–6404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]