Abstract

Vincristine is a toxic chemotherapeutic agent which often triggers neuropathic pain through inflammation. Morin isolated from figs (Ficus carica) exerts anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities. We investigated whether morin ameliorates vincristine-induced neuropathic pain and the underlying mechanism. Vincristine was injected i.p. for 10 days (day 1–5 and day 8–12). Morin was orally administered every other day from day 1 to 21. The pain behaviors were determined by measuring paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) and paw withdrawal latency (PWL). The axons of sciatic nerves were stained with toluidine blue to study the histological abnormality. Function deficit of sciatic nerves was evaluated by sciatic functional index and the sciatic nerve conduction velocity. Neuronal excitability was assessed electrophysiologically and inflammatory mediators were detected using western blotting in dorsal root ganglia. The vincristine-induced reduction in PWT, PWL, and body weight gain was attenuated by morin. Morin restored the sciatic nerve deficits both histologically and functionally in vincristine-injected rats. The vincristine-induced neuronal hyperexcitability and increase in the expression of IL-6, NF-κB, and pNF-κB were abolished after morin administration. This study suggests that morin treatment suppressed vincristine-induced neuropathic pain by protecting the sciatic nerve and inhibiting inflammation through NF-κB pathway.

Keywords: Vincristine, Morin, Neuropathic pain, Inflammation, NF-κB pathway

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) generated during anti-tumor treatment is one of the most serious complications which leads to motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction (Park 2014). CIPN is usually long-lasting and pain or unpleasant paresthesias can persist or even aggravate following the cessation of chemotherapy (Verstappen et al. 2005). Vincristine is known as one of the most neurotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs, which stabilizes tubulin and blocks depolymerization of this protein, causing the degradation of axonal microtubule cytoskeleton and demyelination (Tanner et al. 1998). Vincristine administration promotes the release of proinflammatory mediators including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α by activating astrocyte, microglia, and immune cells in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Gautam and Ramanathan 2018). These inflammatory mediators play crucial roles in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain (Schomberg et al. 2012). Moreover, the inhibition of inflammation reduces neuronal death, leading to the attenuation in thermal allodynia and mechanical hyperalgesia in several pain models (Bachewal et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2018; Kiguchi et al. 2009). Therefore, CIPN induced by vincristine intoxication is the most important limiting factor that affects the effective dose and continuity of anti-cancer treatment.

Although multiple compounds have been developed in order to treat CIPN, their analgesic effects are still controversial (Hu et al. 2019). Therefore, novel drugs or therapies that suppress CIPN caused by vincristine without attenuating its anti-cancer effects are of great significance. Morin (3,5,7,20,40-pentahydroxyflavone), a naturally occurring bioflavonoid derived from the family members of Moraceae has been found to play an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role (Fang et al. 2003; Kapoor and Kakkar 2012). Morin exhibits neuroprotective activity in diabetic neuropathy and colon cancer (Bachewal et al. 2018; Sharma et al. 2018). The treatment with morin blocks astrocyte activation and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Jiang et al. 2017). Previous studies have shown that morin mediates its anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects through inhibition of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway.

The transcription factor NF-κB is a protein complex that regulates cytokine production, immune response, and apoptosis (Ducut Sigala et al. 2004; Karin and Ben-Neriah 2000). In the unstimulated state, the NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm by the inhibitor of κB (IκBα) (Ghosh et al. 1998). Various external stimuli induce phosphorylation and thus triggers degradation of IκBα, allowing the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus to regulate gene expression (Verma et al. 1995). The activation of the NF-κB pathway leads to the production and release of proinflammatory mediators including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), TNF-α, and IL-6, which facilitates the pain processing (Sommer and Kress 2004).

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effect and molecular basis of morin treatment on inflammation and the progression of vincristine-induced neuropathic pain in rats. The function and histology of sciatic nerve, which regulates the pain responses, was also studied. Neuronal excitability in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) was evaluated by recording the resting membrane potential and action potential. Together, our findings provided evidence of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory role of morin in vincristine-induced CIPN.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats with a body weight of 250–300 g were kept in a room with controlled temperature and humidity under a standard 12-h light/dark cycle and received ad libitum access to food pellets and purified water. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University approved all the experiments involving animals, which were performed according to the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain. The health status of each animal was closely monitored and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Drugs

Vincristine (aqueous, 1 mg/ml) was purchased from Cipla (Mumbai, India) with brand name Cytocristin. Vincristine (0.1 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in two courses of treatment with a two-day interval (from day 1 to 5 and from day 8 to 10). Morin was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and was reconstituted in sodium carboxymethyl cellulose solution (0.5% in H2O). The prepared solution was administered per os (p.o.) at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg every other day for totally 11 times (on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21). In the vincristine + vehicle group, rats received vincristine injection as stated above and oral administration of 0.5% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose solution (vehicle) on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21.

Pain Behavioral Tests

Von Frey monofilaments were used to measure pain intensity to mechanical stimuli. Rats were placed on an elevated mesh screen in a transparent Perspex box. A series of Von Frey filaments with logarithmical increments of pressure intensities (0.407, 0.692, 1.202, 2.041, 3.63, 5.495, 8.511, 15.14 g) were applied to the plantar surface of each hind paw. Starting with the 2.041 g filament, if the animal responded to the stimulus with a sharp paw withdrawal, the next smaller filament was chosen; if the paw withdrawal response was absent, the next larger filament was presented. Paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was calculated by converting the pattern of negative and positive responses to a 50% threshold value using the up-down method of Dixon (Chaplan et al. 1994).

To measure paw withdrawal latencies to noxious heat, a radiant heat source was targeted at the plantar surface of each hind paw. A photoelectric recorder located on the top of the testing chamber detected light emitted from the radiant heat source and stopped recording when paw movement interrupted the light. Paw withdrawal latency (PWL) was defined as the shortest duration between the activation of radiant heat and the foot lift of the animal. To prevent tissue damage in hind paws, maximal heating time is 20 s.

To determine paw withdrawal latencies to noxious cold, each rat was placed on the cold plate set at 0 °C in a chamber. The paw withdrawal latency was defined as the duration between the placement of the rat’s hind paw on the cold plate and the animal jumping. To prevent tissue damage in hind paws, maximal time on the cold plate is 60 s.

All the pain behaviors were tested before the first dose of vincristine administration to establish a baseline and continued on days 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21.

Measurement of Body Weight

Rats were weighed using a digital scale before every behavior test on days 0, 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21.

Toluidine Blue Staining

Rats were anaesthetized by inhaling 2% isoflurane and their biceps femoris muscles were dissected to expose the sciatic nerve. To minimize structural degradation, tissue was fixed in vivo by adding fixative solution (4% formaldehyde, 1% glutaraldehyde in 1 × PBS) onto the sciatic nerve for three times (10 min each). Next, the nerve tissue was obtained and transferred to 2% osmium tetroxide for 2 h. After dehydration in acetone, nerve tissue was embedded in resin medium using epoxy embedding medium kit (Sigma Aldrich). The resin-embedded nerve blocks were placed onto ultramicrotome (RMC Products, Tucson, Arizona, USA), and several 8 µm cross sections were sliced using a glass knife. The sciatic nerve sections were attached on glass slides and stained in 1% toluidine blue (Sigma Aldrich) solution for 30 s. The sections were gently rinsed in deionized water and allowed to dry at room temperature overnight. The sciatic nerve sections were examined and photographed using a light microscope with 60 × oil immersion lens (Olympus BX51, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA).

Sciatic Functional Index Test

Paper strips were dyed with a 0.5% bromophenol blue (Sigma Aldrich) in acetone and air dried. The dried paper strips were yellow colored and returned to deep blue when contacting moisture. The hind paws of the rats were dipped in water and the animals could walk on the dyed paper strips before vincristine treatment and on days 3, 7, 10, 14 of vincristine treatment. The footprints of the rats were developed on the paper strips and scanned into digitized images. The following parameters were measured from the footprint images of both the experimental (E) and normal (N) paws: (I) print length (PL, the distance from the heel to the longest toe tip); (II) toe spread (TS, the distance between the first and the fifth toes); (III) intermediary toe spread (ITS, the distance between the second and the fourth toes). The sciatic functional index (SFI) was calculated using the formula derived by Bain et al. (Bain et al. 1989) as follows:

Sciatic Nerve Conduction Velocity Tests

To assess sciatic nerve conduction velocity, rats were anaesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and two needle electrodes were placed in the small foot muscles. The compound muscle action potential was recorded during distal stimulation by placing two electrodes on the tibial nerve at the ankle, and during proximal stimulation by placing two electrodes on the sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch. Sciatic nerve conduction velocity was calculated from the sciatic nerve latency measurements.

Whole-Cell Patch Clamp Recording

After two courses of vincristine treatments, dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were isolated and DRG neurons were dissociated and plated on culture dishes coated with poly-d-lysine. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings on DRG neurons were made within 10 h after acute isolation. Cells were superfused with extracellular solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 5 glucose, pH 7.38 with NaOH) at room temperature. The patch pipette with a resistance of 3–5 MΩ was filled with intracellular solution contained the following (in mM: 135 KCl, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na2ATP, 1.1 CaCl2, 2 EGTA, and 5 glucose, pH 7.38 with KOH). Analog signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz (Multiclamp 700B, Axon Instruments) with pClamp 10.4 (Molecular Devices). In current-clamp mode, the resting membrane potential of DRG neurons was measured after a stable baseline recording was established. Series resistances were compensated to 80%. Cell capacitance was measured directly by the amplifier displayed as the whole-cell capacitance compensation. Leak currents were minimized using the P/4 leak subtraction. To evoke action potentials, the cells were held at their resting membrane potentials (−40 mV ~ −60 mV) and a series of 200 ms current steps of 100 pA incremental amplitude from 100 to 1200 pA at 1 Hz. Rheobase was defined as the threshold current to elicit a single AP.

Western Blotting

Bilateral lumbar 4–6 DRGs were obtained and homogenized in chilled lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM benzamidine, 40 μM leupeptin, 150 mM NaCl, 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail I and cocktail II). The specimen was then centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 1000 g and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentrations were determined and the samples were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) electrophoretically. After blocking nonspecific binding sites with 3% low‐fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight on shaker. The primary antibodies including rabbit-anti-IL-6 (diluted at 1:1000), rabbit-anti-NF-κB (diluted at 1:1000), rabbit-anti-phospho-NF-κB (diluted at 1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA) and rabbit-anti-β-actin antibody (diluted at 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as a loading control. After being washed in Tris-buffered saline, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and exposure to film. The optical densities of protein bands were quantified with densitometry.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS for Windows version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For western blot experiments, the protein expression levels were statistically analyzed with the Friedman test. Comparisons between three or more groups were made with a one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

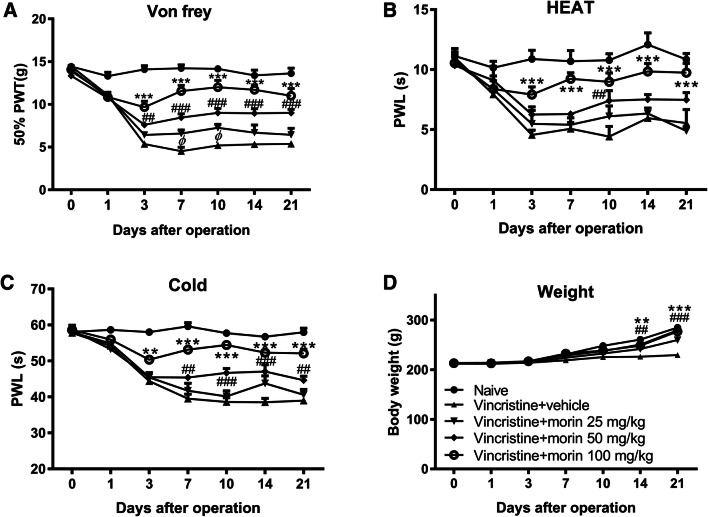

Morin Treatment Suppresses Vincristine-Induced Neuropathic Pain

To understand how vincristine trigger neuropathic pain, we first explored whether two 5-day vincristine treatment courses influence the pain hypersensitivity. Compared to the naïve group, pain behavioral analysis by assessing paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) using mechanical (Von Frey filament) insult showed that vincristine injection led to mechanical hyperalgesia that persisted for more than three weeks (Fig. 1a). Heat allodynia and cold allodynia determined using paw withdrawal latency (PWL) were also robustly produced by vincristine in a similar time course as mechanical hyperalgesia (Fig. 1b, c). To study the effect of morin on vincristine-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and thermal allodynia, morin was administered p.o. every other day from day 1 to day 21 of vincristine treatment. Significant reductions in paw withdrawal threshold in Von Frey test and paw withdrawal latency in response to heat or cold stimulation were seen in rats treated with 50 mg/kg morin (Fig. 1a–c). Moreover, 100 mg/kg morin produced a more prominent suppression on mechanical hyperalgesia and thermal allodynia in vincristine-treated animals (Fig. 1a–c). Therefore, morin treatment induced a dose-dependent reduction of vincristine-induced pain hypersensitivity. In addition, vincristine-induced loss of body weight gain was reversed after morin treatment (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that the repeated morin administration leads to blunting of long-lasting vincristine-induced neuropathic pain.

Fig. 1.

Morin treatment alleviates vincristine-induced pain hypersensitivity. a–c Mechanical (a), thermal (b), and cold (c) sensitivity in the naïve group, vin + vehicle group, and vin + morin 25/50/100 mg/kg groups. d Body weight of rats in the naïve group, vin + vehicle group, vin + morin 25/50/100 mg/kg groups. n = 6 rats in each group. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vin + morin 100 mg/kg group versus naïve group; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vin + morin 50 mg/kg group versus naïve group; φ p < 0.05 vin + morin 125 mg/kg group versus naïve group; repeated measured two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test

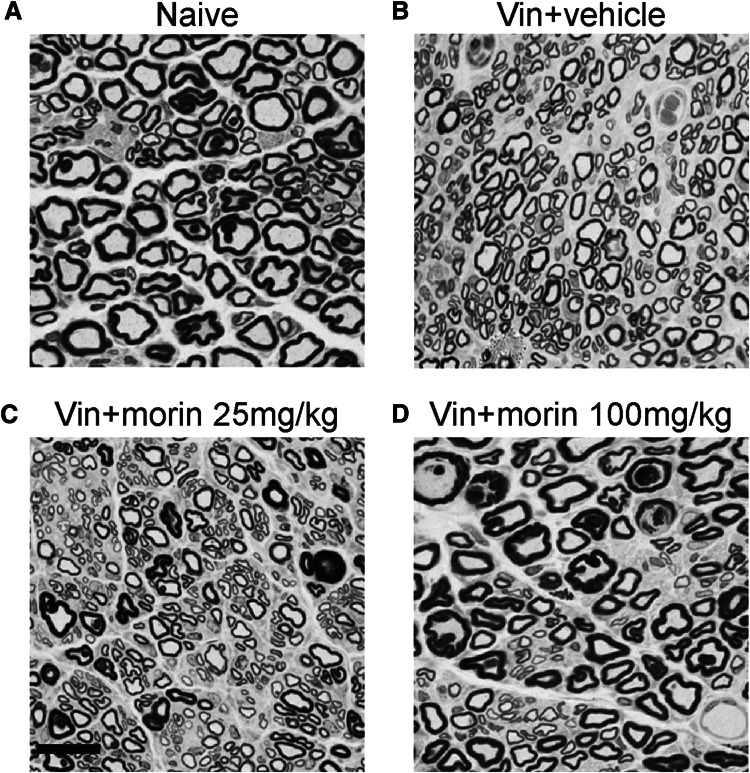

Morin Treatment Restores Vincristine-Induced Histological Abnormality in Sciatic Nerve

Because pain behaviors were tested based on the response of the hind paws of rats, we next determined whether morin affects tissue histology of sciatic nerves that mediate sensation to the skin and paws after vincristine injection. The toluidine blue-stained axons of sciatic nerves showed a severe myelin degeneration and a reduction in the diameters of fibers in vincristine group compared with the naïve animals (Fig. 2a, b). When the vincristine-injected animals were treated with 25 mg/kg morin, the myelination and fiber diameters in the sciatic nerve were slightly ameliorated (Fig. 2c). Moreover, a higher dose (100 mg/kg) of morin induced a predominance of myelinated fibers and significantly increased the diameters of the fibers (Fig. 2D). Thus, morin protects sciatic nerve from vincristine-induced pathological abnormality characterized by demyelination and fiber diameter reduction.

Fig. 2.

Morin treatment restores the vincristine-induced sciatic nerve neuropathy. a–d Toluidine blue-stained axons of sciatic nerve from rats in naïve group (a), vin + vehicle group (b), vin + morin 25 mg/kg group (c), and vin + morin 100 mg/kg group (d). A noted increase in the number of small myelinated fibers in vincristine-treated group and a recovery of fiber diameter in vin + morin 100 mg/kg group were observed. Scale bar: 25 μm

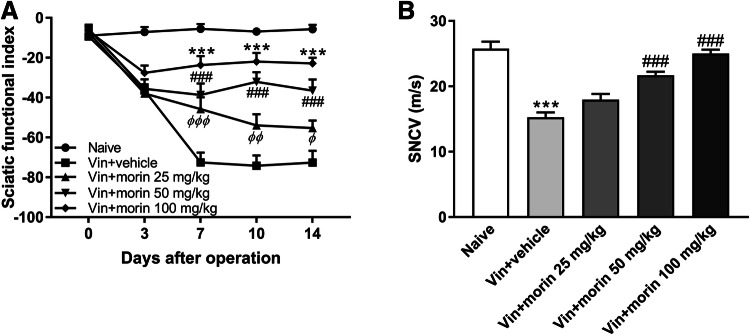

Morin Treatment Recovers Vincristine-Induced Functional Loss in Sciatic Nerve

Given that morin restored sciatic nerve morphological abnormality in vincristine-injected rats, we next investigated the effect of morin on the function of sciatic nerve. Vincristine induced a dramatic decrease in sciatic functional index, indicating a loss of the ability to spread the toes of the hind leg assessed using footprint parameters (Fig. 3a). However, morin treatment exerted a dose-dependent recovery in the sciatic functional index (Fig. 3a). On the last day of vincristine injection, rats were anaesthetized and the sciatic nerve conduction velocity (SNCV) was measured using two needle electrodes. We found that both 50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg morin treatment in rats reversed the vincristine-induced decrease in the sciatic nerve conduction velocity (Fig. 3b). Together, these data indicate a protective effect of morin treatment on function of sciatic nerve in vincristine-intoxicated animals.

Fig. 3.

Morin recovers the vincristine-induced sciatic nerve function deficit. a Sciatic nerve index in naïve group, vincristine group, and vin + morin 25/50/100 mg/kg groups. ***p < 0.001 vin + morin 100 mg/kg group versus naïve group; ###p < 0.001 vin + morin 50 mg/kg group versus naïve group; φ p < 0.05, φφ p < 0.01, φφφ p < 0.001 vin + morin 25 mg/kg group versus naïve group; repeated measured two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. b Sciatic nerve conduction velocity (SNCV) in naïve group, vincristine group, and vin + morin 25/50/100 mg/kg groups. ***p < 0.001 versus naïve group and ###p < 0.001 versus vin + vehicle group, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6 rats in each group

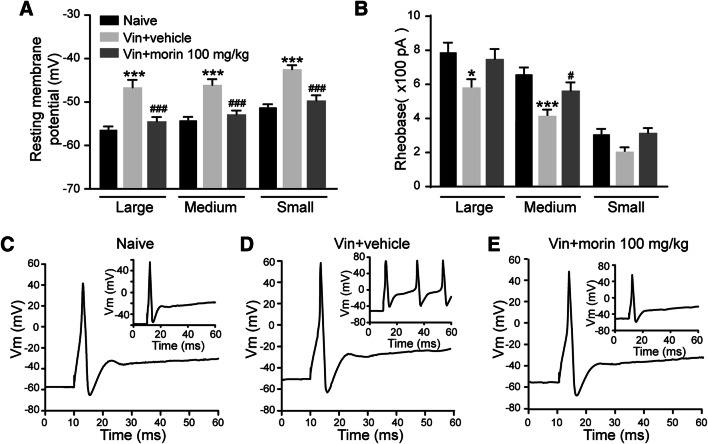

Morin Treatment Suppresses Vincristine-Induced Hyperexcitability of DRG Neurons

Because previous studies have shown that the development of neuropathic pain requires the excitation of the primary sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG), we sought to determine the excitability of DRG neurons in morin- and vincristine-treated rats. Whole-cell current-clamp recording was performed after two treatment courses of vincristine in large, medium, and small DRG neurons. Compared to the naïve group, the resting membrane potentials were significantly increased in all three types of DRG neurons in vincristine group and this vincristine-induced depolarization was reversed 100 mg/kg morin treatment (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the rheobase, which is the threshold current for a single action potential firing, was reduced following vincristine exposure in large and medium DRG neurons, whereas morin treatment diminished this effect (Fig. 4b). By injecting 200 pA current into the DRG neurons, we also found that morin suppressed the vincristine-induced increase in the numbers of action potentials (Fig. 4c–e). Therefore, the hyperexcitability of DRG neurons occurred after vincristine injection was suppressed by morin.

Fig. 4.

Morin treatment attenuates the hyperexcitability of DRG neurons induced by vincristine. a Resting membrane potential of large, medium, and small DRG neurons. N = 20, 20, 21 for large, medium, and small neurons in each group. b Rheobase of DRG neurons. N = 15 for large, medium, and small neurons in each group. c–d Action potential traces of DRG neurons in naïve, vin + vehicle, and vin + morin 100 mg/kg group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 versus naïve group and #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 versus vin + vehicle group, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6 rats in each group

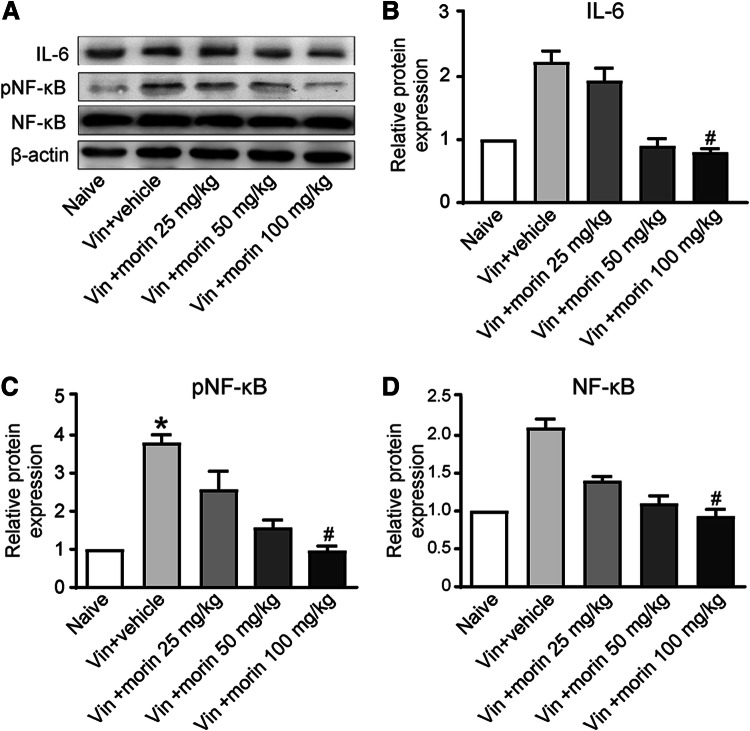

Morin Treatment Alleviate Vincristine-Induced Inflammation

It has been reported that morin plays an anti-inflammatory role in pain inhibition, here we tested whether the inflammatory response is involved in the morin-induced suppression of neuropathic pain. After repeated treatment of higher doses of morin, the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) was significantly reduced compared with vincristine-injected rats in DRG (Fig. 5a, b). The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is a transcription factor that controls the release of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6. We found that the vincristine-induced increase in NF-κB expression was abolished when morin was administered (Fig. 5a and d). To assess the activity of NF-κB pathway, the expression of phospho-NF-κB (pNF-κB) in DRG was also tested. Morin exerted a dose-dependent suppression of the increase of pNF-κB expression triggered by vincristine intoxication (Fig. 5a and c), indicating NF-κB pathway activation leads to inflammation during neuropathic pain progression and morin attenuated this effect.

Fig. 5.

Effect of morin on inflammatory mediator levels in rats with vincristine-induced neuropathic pain. a Western blot images representing the expression of IL-6, pNF-κB, NF-κB, and β-actin. b–d Histograms showing relative expressions of IL-6 (b), pNF-κB (c), NF-κB (d) in L4-L6 DRGs. *p < 0.05 versus naïve group and #p < 0.05 versus vin + vehicle group by Friedman test

Discussion

Cancer patients undergoing treatment with vincristine frequently develop sensorimotor peripheral neuropathic pain that reduces their quality of life and may lead to dose reduction or even premature cessation of chemotherapy (Lin et al. 2018). Vincristine intoxication initiates and maintains pain behaviors through the pathological alteration and increase in spontaneous discharge of both A-fibers and C-fibers (Xiao and Bennett 2008). Consistent with previous findings (Gautam and Ramanathan 2018; Geis et al. 2011), we found that the changes in pain-related behavioral responses including mechanical hyperalgesia, thermal, and cold allodynia developed within one week and continued to deteriorate during the second and third weeks since the first dose of vincristine. The body weight gain was also abolished in the vincristine group. To determine whether morin ameliorates vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy and loss of body weight gain, morin was treated p.o. to rats at three different doses including 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg every other day for 11 times. The repeated morin administration had a dose-dependent attenuation of vincristine-induced hyperalgesic effects and recovered body weight gain. These findings revealed an antinociceptive role of morin on Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN).

Pain signals are transmitted to the central nervous system through sciatic nerves located at lumbar 4–6 (Asato et al. 2000). It is well accepted that partial denervation of rat sciatic nerve triggers neuropathic pain (Bennett and Xie 1988). In addition, inherited peripheral neuropathies is associated with predominantly smaller unmyelinated axons in sciatic nerve (Kroner et al. 2009). We also observed this nerve disorder in the vincristine-injected rats by staining the axons of sciatic nerves with toluidine blue. The vincristine-induced demyelination resulted in a severe loss of sciatic nerve function, which was determined by measuring the sciatic functional index and sciatic nerve conduction velocity. Our data have shown that the sciatic nerve conduction velocity was decreased by vincristine, consistent with the role of myelin, which insulates the axon with Schwann cells to speed up action potential conduction (Steinman 1996). Impaired sciatic functional index was observed after vincristine injection, indicating that the sciatic nerve demyelination results in an abnormal gait in rats. Oral administration of morin abolished the impairment in sciatic nerve morphology caused by vincristine injection, therefore morin restored the function of hind limb and the sciatic nerve conduction velocity. In morin-treated rats, the sensation of the harmful insults can be transmitted faster and more accurately to the central nervous system via the myelinated fibers, thus the over-activation of A-fiber and C-fiber is prevented. Together, our studies in histology, electrophysiology, and function of sciatic nerve suggest that the antinociceptive effect of morin is attributable to its maintenance of myelination.

The functional and morphological damage in the sciatic nerve is associated with excitation of primary sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (Wang et al. 2018). Previous studies have shown that voltage-gated potassium channels modulate the progression of neuropathic pain by regulating resting membrane potentials and the excitability of DRG neurons (Fan et al. Fan 2014). Peripheral nerve damage is a known inhibitor of voltage-gated potassium channels on both transcriptional and translational levels in the injured DRG, leading to hypersensitivity to pain (Chien et al. 2007). Indeed, our whole-cell current-clamp experiments have shown vincristine-induced neuropathic pain depolarized the resting membrane potentials and decreased the current threshold to generate action potentials in DRG neurons. The increased DRG neuronal excitability triggers the production and secretion of neurotransmitters including calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P, and glutamate from the axons of the primary neurons, leading to the central sensitization of spinal cord and hyperalgesia (Devor 2009; Zhao et al. 2017). However, repeated treatment of morin reversed the pathological hyperexcitability of DRG neurons in this model of vincristine neuropathy. Thus, these data suggest that morin exerts a neuroprotective effect on chemotherapy-induced excitotoxicity in peripheral neuropathy, contributing to pain management during anti-cancer treatment.

Chronic treatment of morin inhibits glial cells to downregulate the proinflammatory cytokines, leading to the suppression of neuropathic pain by glia-neuron interactions (Jiang et al. 2017). The vincristine-induced nerve injury promotes glial modulator secretion to activate microglia (Tsuda et al. 2003). Astrocyte activation following microglia activation regulates neuronal plasticity in the spinal cord by producing various proinflammatory mediators (Gautam and Ramanathan 2018). The attenuation of the these proinflammatory mediators ameliorates neuropathic pain (Kiguchi et al. 2009). Thus, we sought to test whether the morin-mediated neuroprotection in DRG is due to its suppression on neuroinflammation. We provided evidence that morin reversed the increase in IL-6 expression in vincristine-injected animals, suggesting its suppression on proinflammatory cytokine release from glial cells. We further explored the molecular mechanism of morin by determining the involvement of NF-κB pathway. It is clear that morin reversed the vincristine-induced promotion of NF-κB signaling. This is consistent with previous studies that morin exhibit anti-tumor activity by blocking NF-κB pathway (Manna et al. 2007). Here, we conclude that morin alleviates the vincristine-induced inflammation in DRG by suppressing the activation of NF-κB pathway.

In the current study, we have provided an alternative chemotherapy treatment plan by introducing morin co-treatment with the traditional anti-cancer drug vincristine. The application of morin can dramatically reduce the vincristine-induced neuropathic pain which is the largest limiting factor of chemotherapy.

Conclusions

This study suggests that activation of NF-κB pathway plays an important role in promoting inflammatory response thereby triggers the hyperexcitability of DRG neurons during vincristine intoxication. The function and morphology of sciatic nerve are also impaired by vincristine, resulting in the progression of neuropathic pain. Morin administration during chemotherapy treatment exhibits an anti-inflammatory response and reverses the vincristine-induced deficits in sciatic nerve and DRG neurons, thus attenuates mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Ke Jiang and Jinshan Shi: Performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Jing Shi: Designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final submission.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors (Ke Jiang, Jinshan Shi, Jing Shi) declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ke Jiang and Jinshan Shi have contributed equally to this study.

References

- Asato F, Butler M, Blomberg H, Gordh T (2000) Variation in rat sciatic nerve anatomy: implications for a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Peripher Nerv Syst 5:19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachewal P, Gundu C, Yerra VG, Kalvala AK, Areti A, Kumar A (2018) Morin exerts neuroprotection via attenuation of ROS induced oxidative damage and neuroinflammation in experimental diabetic neuropathy. BioFactors 44:109–122. 10.1002/biof.1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain JR, Mackinnon SE, Hunter DA (1989) Functional evaluation of complete sciatic, peroneal, and posterior tibial nerve lesions in the rat. Plast Reconstr Surg 83:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Xie YK (1988) A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain 33:87–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL (1994) Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 53:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J-Y, Chu L-W, Cheng K-I, Hsieh S-L, Juan Y-S, Wu B-N (2018) Valproate reduces neuroinflammation and neuronal death in a rat chronic constriction injury model. Sci Rep 8:16457. 10.1038/s41598-018-34915-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien L-Y, Cheng J-K, Chu D, Cheng C-F, Tsaur M-L (2007) Reduced expression of A-type potassium channels in primary sensory neurons induces mechanical hypersensitivity. J Neurosci 27:9855–9865. 10.1523/jneurosci.0604-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M (2009) Ectopic discharge in Abeta afferents as a source of neuropathic pain. Exp Brain Res 196:115–128. 10.1007/s00221-009-1724-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducut Sigala JL, Bottero V, Young DB, Shevchenko A, Mercurio F, Verma IM (2004) Activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB requires ELKS, an IkappaB kinase regulatory subunit. Science 304:1963–1967. 10.1126/science.1098387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L et al (2014) Impaired neuropathic pain and preserved acute pain in rats overexpressing voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.2 in primary afferent neurons. Mol Pain 10(1):8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S-H, Hou Y-C, Chang W-C, Hsiu S-L, Chao P-DL, Chiang B-L (2003) Morin sulfates/glucuronides exert anti-inflammatory activity on activated macrophages and decreased the incidence of septic shock. Life Sci 74:743–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam M, Ramanathan M (2018) Saponins of Tribulus terrestris attenuated neuropathic pain induced with vincristine through central and peripheral mechanism. Inflammopharmacology. 10.1007/s10787-018-0502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis C, Beyreuther BK, Stöhr T, Sommer C (2011) Lacosamide has protective disease modifying properties in experimental vincristine neuropathy. Neuropharmacology 61:600–607. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB (1998) NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 16:225–260. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-Y, Mi W-L, Wu G-C, Wang Y-Q, Mao-Ying Q-L (2019) Prevention and treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: therapies based on CIPN mechanisms. Curr Neuropharmacol 17:184–196. 10.2174/1570159x15666170915143217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Wang Y, Sun W, Zhang M (2017) Morin suppresses astrocyte activation and regulates cytokine release in bone cancer pain rat models. Phytother Res 31:1298–1304. 10.1002/ptr.5849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R, Kakkar P (2012) Protective role of morin, a flavonoid, against high glucose induced oxidative stress mediated apoptosis in primary rat hepatocytes. PLoS ONE 7:e41663. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y (2000) Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol 18:621–663. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiguchi N, Maeda T, Kobayashi Y, Saika F, Kishioka S (2009) Involvement of inflammatory mediators in neuropathic pain caused by vincristine. Int Rev Neurobiol 85:179–190. 10.1016/s0074-7742(09)85014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner A, Schwab N, Ip CW, Sommer C, Wessig C, Wiendl H, Martini R (2009) The co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 modulates disease severity in a model for an inherited, demyelinating neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis 33:96–103. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MJ-Y, Paul MR, Kuo DJ (2018) Severe neuropathic pain with concomitant administration of vincristine and posaconazole. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 23:417–420. 10.5863/1551-6776-23.5.417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna SK, Aggarwal RS, Sethi G, Aggarwal BB, Ramesh GT (2007) Morin (3,5,7,2′,4′-Pentahydroxyflavone) abolishes nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by various carcinogens and inflammatory stimuli, leading to suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene expression and up-regulation of apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 13:2290–2297. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-06-2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HJ (2014) Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathic pain. Korean J Anesthesiol 67:4–7. 10.4097/kjae.2014.67.1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomberg D, Ahmed M, Miranpuri G, Olson J, Resnick DK (2012) Neuropathic pain: role of inflammation, immune response, and ion channel activity in central injury mechanisms. Ann Neurosci 19:125–132. 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.190309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SH, Kumar JS, Chellappan DR, Nagarajan S (2018) Molecular chemoprevention by morin—a plant flavonoid that targets nuclear factor kappa B in experimental colon cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 100:367–373. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Kress M (2004) Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett 361:184–187. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L (1996) Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system. Cell 85:299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD, Levine JD, Topp KS (1998) Microtubule disorientation and axonal swelling in unmyelinated sensory axons during vincristine-induced painful neuropathy in rat. J Comp Neurol 395:481–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Mizokoshi A, Kohsaka S, Salter MW, Inoue K (2003) P2X4 receptors induced in spinal microglia gate tactile allodynia after nerve injury. Nature 424:778–783. 10.1038/nature01786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S (1995) Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev 9:2723–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstappen CCP et al (2005) Dose-related vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy with unexpected off-therapy worsening. Neurology 64:1076–1077. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000154642.45474.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y et al (2018) Sensitization of TRPV1 receptors by TNF-α orchestrates the development of vincristine-induced pain. Oncol Lett 15:5013–5019. 10.3892/ol.2018.7986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao WH, Bennett GJ (2008) Chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain: abnormal spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fiber primary afferent neurons and its suppression by acetyl-L-carnitine. Pain 135:262–270. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J-Y et al (2017) DNA methyltransferase DNMT3a contributes to neuropathic pain by repressing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Commun 8:14712. 10.1038/ncomms14712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]