Abstract

Evidence suggests that microglia/macrophages can change their phenotype to M1 or M2 and participate in tissue damage or repair. Berberine (BBR) has shown promise in experimental stroke models, but its effects on microglial polarization and long-term recovery after stroke are elusive. Here, we investigated the effects of BBR on angiogenesis and microglial polarization through AMPK signaling after stroke. In the present study, C57BL/6 mice were subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO), intragastrically administrated with BBR at 50 mg/kg/day. Neo-angiogenesis was observed by 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD micro-PET/CT and immunohistochemistry. Immunofluorescent staining further exhibited an increase of M2 microglia and a reduction of M1 microglia at 14 days after stroke. In vitro studies, the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced BV2 microglial cells were used to confirm the AMPK activation effect of BBR. RT-PCR, Flow cytometry, and ELISA all demonstrated that BBR could inhibit M1 polarization and promote M2 polarization. Furthermore, treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with conditioned media collected from BBR-treated BV2 cells promoted angiogenesis. All effects stated above were reversed by AMPK inhibitor (Compound C) and AMPK siRNA. In conclusion, BBR treatment improves functional recovery and promotes angiogenesis following tMCAO via AMPK-dependent microglial M2 polarization.

Keywords: Berberine, Angiogenesis, Microglia/macrophages, Polarization, Ischemic Stroke

Introduction

After cerebral infarction occurs, a process of angiogenesis is triggered in the ischemic penumbra, where angiogenesis is a critical compensation route and the course of regenerating new blood vessels by sprouting to meet the biological functions of local tissues effectively (Huang et al. 2016; Madelaine et al. 2017; Seto et al. 2016). It is largely dependent on the balance of a mix of angiogenic growth factors and angiostatic factors to promote or sustain endothelial cell proliferation and migration (Liu et al. 2014; Manavski et al. 2018). Several lines of documents have highlighted that there is an encouraging relationship between angiogenesis and stroke outcome (Li et al. 2018b). Clinically, higher microvessel density in the ischemic border is associated with a better long-term prognosis in stroke patients (Krupinski et al. 1994). Hence, it is now recognized that pro-angiogenesis may represent a potent therapeutic strategy for long-term recovery after ischemic stroke.

Previous studies suggested that microenvironment in brain tissue plays a contributing role in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury (CI/RI) (Xiong et al. 2016). Resident microglia and infiltrated macrophages exert the initial action of active immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS), which respond dynamically to the regulation of inflammatory condition in the injured brain (Liu et al. 2018, 2017). Actually, the dual roles of microglia/macrophages are throughout the course of ischemic injury (Kabba et al. 2018). Within the symptom initiation, microglia/macrophages show a transient M2 phenotype in the ischemic penumbra and then secrete high levels of neurotrophic factors, including TGF-β, IL-10, and VEGF to prolong neuron survival, lessen cerebral infarction volume, and participate in forming new blood vessels, and then activated microglia/macrophages whose shift to the M1 phenotype could exacerbate brain injury by releasing multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Xiang et al. 2018; Jiang et al. 2018; Ganta et al. 2017). In essence, when reperfusion begins, microglia/macrophages start to expand cellular protrusions toward the adjacent blood vessels, and the role of M2 polarization in modulating an angiogenic response in ischemia has gained enormous acceptance worldwide (Donners 2013; Lin et al. 2014). Interestingly, there is evidence that adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation is responsible for neuroinflammation alleviation and macrophage/microglial polarization to the M2 phenotype (Sag et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2018a, b). Therefore, pharmacologically promoting the transition from the M1 to M2 phenotype would be a challenge of vascular remodeling and perfusion recovery by targeting AMPK after ischemic stroke.

Berberine (BBR), a common isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from traditional Chinese medicine, has the pharmacological and bioactive properties for treatment of CNS disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral ischemia (Lin and Zhang 2018; Sohn et al. 2019). The ability of BBR to transport cross the blood–brain barrier and accumulate in the brain to function with neurons provokes researchers’ interest (Lu et al. 2010). Based on our previous animal experiments, we chose 50 mg/kg as the representative concentration to investigate the mechanisms of brain protective function in tMCAO mice (Zhu et al. 2018); however, the potential mechanisms of such a phenomenon remain unclear. According to the published data, we hypothesis that BBR could facilitate angiogenesis against ischemic stroke through modulating microglial polarization toward M2 type via AMPK signaling.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model and Drug Administration

All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing First Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, and animal experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. A total of 350 healthy adult male C57BL/6 mice, weighed 20–24 g, were purchased from Vital River Laboratories (Beijing, China). Mice were randomly divided into BBR, vehicle, and sham groups, intragastrically administrated with 50 mg/kg/day BBR solution (Berberine hydrochloride (BP1108, Sigma, USA) dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium) and equivalent solvent, respectively. Mice underwent tMCAO surgery as described previously (Zhu et al. 2018). Animals were anesthetized by 4% chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.). In brief, a midline skin in the neck was incised, then the right common carotid artery(CCA), external carotid artery (ECA), and internal carotid artery (ICA) were separated at the same time. A silicon-coated 6-0 suture (0623, Yunshun, Heinan) was inserted into the ECA and advanced from the ICA to the opening of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The suture was withdrawn after 45 min of occlusion, followed by reperfusion. Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was monitored by Perfusion Speckle Image System (FLP12, Gene & I, Beijing) throughout the ischemia and reperfusion in all stroke mice. Results were presented as percent change compared to baseline.

Assessment of Neurological Function

Neurological deficit scores were measured according to the method of Longa et al. (1989) by an examiner blinded to the experimental groups on days 1, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO. Neurological functions were scored on a five-point scale: 0, no neurological deficit; 1, the failure to extend left paw fully; 2, circling to left; 3, falling to left; 4, the failure to walk spontaneously and lack of consciousness.

Corner Test

The sensorimotor function after tMCAO was examined by the corner test on days 1, 7, 14, and 28. Mice were placed between two cardboards with an angle of 30°. When mice faced the deepest part of the corner, they turned either right or left to the open side. However, when mice were suffered surgery, they preferred to turn selectively to right. The numbers of right turns over 10 trials were recorded.

Rotarod Test

Motor coordination was examined by comparing the ability to stay on the accelerating rotating rod. At first, mice were trained for 3 days before the surgery until they reached the same level around 5 min. Then, mice were tested on days 1, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO. All mice were placed on an accelerating rotating rod at an increasing speed from 4 to 40 rpm within 5 min for 3 times, and the time until the mouse fell onto the platform below was recorded.

Measurement of Cerebral Infarction

After 24 h reperfusion, mice were eventually anesthetized and sacrificed by decapitation. The brains were cut into 4 slices (2 mm thickness each) and stained with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) in 37 °C water bath for 30 min in the dark. After TTC staining, the colored and the non-colored areas of the slices were measured by ImageJ, respectively. The results were calculated and expressed as percentage infarction area, described as brain infarction size = (contralateral volume − ipsilateral non-infarction volume)/contralateral volume × 100%.

Determination of Cerebral Edema

To determine cerebral edema, brains were quickly removed at 24 h after reperfusion and immediately weighed (wet weight). After dehydration at 105 °C for 24 h, brains were weighed again (dry weight). Brain edema was determined using the following formula: brain water content = [(wet weight − dry weight)/wet weight] × 100%.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) Staining

On day 14 after surgery, mice were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate, and intracardially perfused with 200 mL normal saline and 200 mL 4% paraformaldehyde. Their brains were cut into 5-μm-thick slices and stained by HE; histological changes were observed under the Olympus CX23 microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Staining

The brains were harvested on day 14 post-tMCAO for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining, as described elsewhere (Jin et al. 2014). The sections were embedded in paraffin and further sliced into 5-μm-thick sections for immunohistochemistry. The samples were incubated with anti-mouse polyclonal antibody against CD31 (1:100; CST, USA) at 4 °C for 12 h, followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) as the secondary antibody for 30 min at 37 °C. The proteins were detected by using the DAB kit (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the distribution of CD31 cells was observed using a light microscope (BH-2; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). On the other hand, the brain slices acquired above were subjected to immunofluorescence staining. Non-specific staining was blocked with 10% normal serum. Then, brain slices were incubated with primary antibodies against Ki67 (1:500, GB13030-2), CD31 (1:100, GB13063), Iba1 (1:200, GB12015), CD16 (1:200, GB14026), CD206 (1:200, GB11062) overnight at 4 °C. Then the slices were treated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies: Cy3 mark donkey anti-goat (1:300), FITC mark donkey anti-rabbit (1:200), Cy3 mark goat anti-mouse (1:300), and 488 mark goat anti-rabbit (1:400), at room temperature for 50 min, respectively. The nuclei of cells were stained with DAPI (G1012) before photographing. The above antibodies were provided by Servicebio (Wuhan, China). All images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (NIKON ECLIPSE C1, Nikon, Germany). In brief, observation was conducted at a lower magnification firstly, then switched to high magnification in the target region, and the number of stained cells was counted. The stained cell number was calculated from six randomly selected microscopic fields across six consecutive sections. Data were presented as mean ± SD of the number of CD31+ cells and the percentage of CD16+ or CD206+ cells to the Iba-1+ cells of view.

68Ga-NODAGA-RGD Micro-PET/CT Imaging

Imaging of the mouse brains was performed using a micro-PET/CT scanner (Inveon, Siemens Medical Solutions, Germany) on day 14 after tMCAO surgery. All group mice were administered with 3.7 MBq 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD via tail vein injection under isoflurane anesthesia. A 10-min static PET scan was acquired at 35 min after injection with an energy window of 350–650 keV. The CT images were acquired with the radiographic tube voltage of 80 kV, current of 500 µA, exposure time of 255 ns. The list-mode PET data were post-processed using a 3-dimensional ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm (OSEM3D) with CT-based attenuation correction into 256 × 256 × 95 matrices with a voxel size of 1.5 mm3.

Cell Culture Methods

BV-2 microglial cells and HUVEC, provided by Prof. Yunman Li, China Pharmaceutical University, were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Everygreen, Tianhang Biotechnology, China) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The medium was changed every 2 days. The cells were split with 0.25% trypsin, 0.02% EDTA (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) when they reached 80% confluence, and subcultured for further passages. Cell viability was determined using the CCK-8 assay (C0041, Beyotime, China). Briefly, 2 × 103 cells per well were plated in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated with different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 10, or 20 μM) of BBR for 24, 48, 72 h, respectively. Then the cells were treated with 100 μL of 10% CCK-8 and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a BD plate reader. The experiments were performed in triplicate, independently.

Transfection

BV-2 cells cultured in 6‐well plates were transfected with scrambled control siRNA (UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT) and AMPKα siRNA (GAGAAGCAGAAGCACGACGTT). These specific siRNA reagents were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and siRNA were premixed in OPTI‐medium (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’ instructions and applied to the cells. After 6 h of transfection, the OPTI‐medium was replaced by RMPI 1640 medium without FBS. Then the transfected BV-2 cells were treated with BBR (1 μM) for another 24 h, followed by exposure to LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h.

Flow Cytometry

To further determine whether the neuroprotective effect of BBR could be associated with the promotion of microglial polarization toward the M2 phenotype, we assessed the membrane protein expression of CD16/32 and CD206 in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells by flow cytometry. BV-2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) and treated with LPS, and after 24 h treatment with BBR, Compound C (S7840, Selleck, China), and AMPK siRNA, respectively. After 24 h, the cells were harvested for analysis. The M1 cells presented membrane protein CD16/32 were detected by direct immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated monoclonal rat CD16/32 antibody (ab210219, Abcam, UK) at 4 °C for 1 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then suspended in PBS in the dark at 4 °C. The M2 cells presented membrane protein CD206 were detected by indirect immunofluorescence staining with PE-conjugated monoclonal mouse CD206 antibody (ab64693, Abcam, UK) at 4 °C for 2 h. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS, and suspended in PBS in the dark at 4 °C. FITC- and PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies with irrelevant specificity were used as negative controls. Light scatter characteristics of 106 cells of each sample were analyzed using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD, USA). Data were acquired using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Real-Time PCR for mRNA Expression

Total RNA was extracted from ischemic brain of C57BL/6 mice on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO (Jin et al. 2014) or from the treated BV-2 microglial cells by TRIzol (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed as follows: RNA samples were reverse-transcribed to cDNA with a commercially available kit according to the manufacturers’ protocol (ABM, Canada), forward and reverse primers, and SYBR Green 2 × PCR master Mix (ABM, Canada) by ABI 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Thirty-five cycles were conducted as follows: 95 °C for 15 s (denaturation step), 60 °C for 60 s (to allow extension and amplification of the target sequence). The PCR results were normalized to GAPDH expression and quantified by the comparative method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The primer sequences of M1 markers (IL-1β, CD32, TNF-α, and iNOS) and M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 5′-CAGGCTCCGAGATGAACAAC-3′ | 5′-GGTGGAGAGCTTTCAGCTCATA-3′ |

| CD32 | 5′-AATCCTGCCGTTCCTACTGATC-3′ | 5′-GTGTCACCGTGTCTTCCTTGAG-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-TATGTCTCAGCCTCTTCTCATTCC-3′ | 5′-TGAGTGTGAGGGTCTGGGC-3′′ |

| iNOS | 5′-TTGACCAGAGGACCCAGAGA-3′ | 5′-AGCTGGTAGGTTCCTGTTGT-3′ |

| CD206 | 5′-ACCCTGTATGCCTGTGATTC-3′ | 5′-ACTCTGTGCCCTTGATTCC-3′ |

| Arg-1 | 5′-GGGAAAGCCAATGAAGAG-3′ | 5′-AGGGGAGTGTTGATGTCAG-3′ |

| IL-10 | 5′-GAAGACAATAACTGCACCCACT-3′ | 5′-CTTAAAGTCCTGCATTAAGGAGTCG-3′ |

| Ym1/2 | 5′-GCTGCTACTCACTTCCACAGG-3′ | 5′-GGACTATTTTCTCCAGTGTAGCCA-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-TCCTGCACCACCAACTGC-3′ | 5′-ACGGCCATCACGCCAC-3′ |

Cytokine Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA)

On days 3 and 14 after tMCAO (Jin et al. 2014), infarcted brain sections were collected and homogenized for ELISA analysis. After BV-2 cells being treated above, culture supernatants were collected for ELISA analysis. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 levels were determined by corresponding ELISA kit (Maijian Biotechnology Center, China) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins from the ipsilateral and contralateral brains on days 3 and 14 after tMCAO (Jin et al. 2014) or from the treated BV-2 cells stated above were extracted by protein extraction kit (Key GEN Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s protocols, and the quantity of total proteins was assessed by the BCA protein assay kit (Key GEN Biotech, China). The protein samples (20 μg each) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred on a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA), and blocked in 5% non-fat milk (BD, USA) in TBS-Tween 20 (TBST), following incubation overnight at 4 °C with rabbit monoclonal antibody against AMPK (1:1000, Cell Signaling), phosphorylated AMPK (1:1000, Abcam Biotechnology), and β-actin (1:1000, Beyotime, China), respectively. The membranes were washed three times with TBST for 10 min each time and then incubated with the following appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature: anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (1:6000), or anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (1:6000, Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, China). Labeled proteins were visualized with Image Quant LAS 4000 mini system using a New Super ECL Assay (KeyGEN BioTECH, China). β-actin was used as a loading control. The optical densities of the protein bands were semi-quantified with ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the results were expressed as the ratio of the phosphorylated protein to the corresponding total protein.

HUVEC Migration

HUVEC migration was assessed by the scratch wound assay and 8.0 μm transwell inserts (Corning, USA). BV-2 cells were treated as mentioned above. After treatment, the culture supernatants were collected as conditioned medium (DM). When the HUVEC growth reached 90% fusion in 6-well plates, a scratch was made in the well bottom by using a sterile 10-μL spear in cultured cells. The pictures of cell migration were taken on day 0 and 1 after scratch. The migration rate of each group was calculated by ImageJ. On the other hand, HUVEC was resuspended in serum-free 1640, and 3 × 104 cells per well were seeded into the transwell inserts to allow the cells to migrate through the 8.0-μm pore polycarbonate membrane to the underside with DM for 24 h. At the time point, the inserts were removed and the cells in the upper inserts were wiped with a cotton swab. Then, the cells on the bottom of the inserts were stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and the stained cells attached to the base membrane of the inserts were counted by a fluorescence inverted microscope (NIKON ECLIPSE C1, Nikon, Germany).

Matrigel Tube Formation Assay

Briefly, 96-well plates were filled with 50 μL Matrigel (Corning, USA) and allowed to solidify at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, HUVECs (4 × 104 cells/50 μL) were gently seeded on top of the gel. Subsequently, microglial DM was collected from BV-2 cells that were treated as described above. After incubation of 8 h, the total number of the pro-angiogenic tube structures was quantified by a fluorescence inverted microscope (NIKON ECLIPSE C1, Nikon, Germany). The results were presented as the total number of pro-angiogenic structures/well.

Statistical Analyses

All measurement data were presented as mean ± SD and differences of means across multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by LSD test. Student’s t test was used for comparisons of neurological scores between two experimental groups. All tests were performed by SPSS 24.0 software (IBM, USA), and p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical figures were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA).

Results

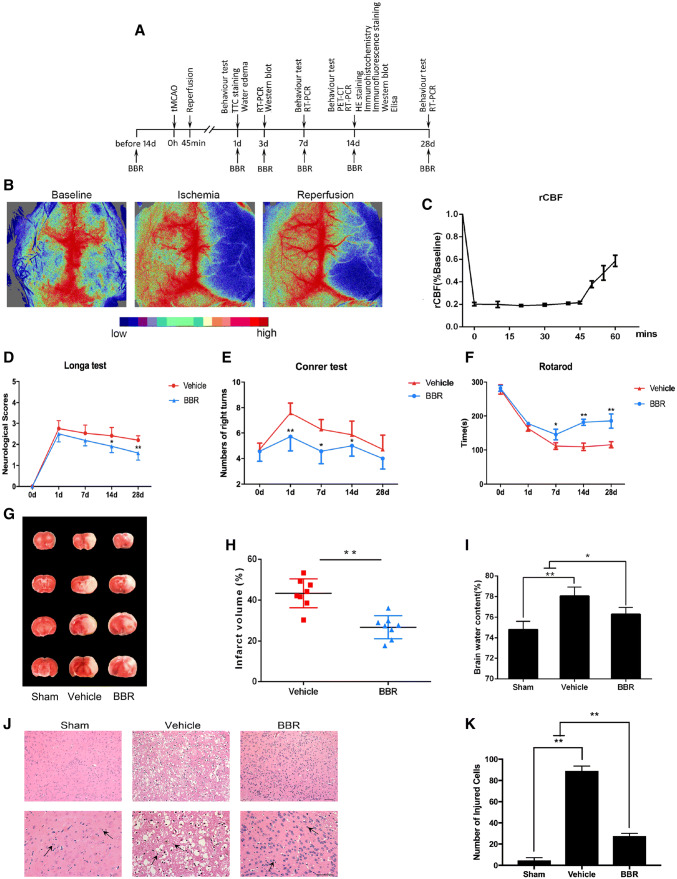

BBR Significantly Ameliorates Ischemia/Reperfusion Lesion after tMCAO

The experimental procedures are shown in Fig. 1a. In total, 350 mice were used for experiments, including 32 mice for the sham group. The mortality rate was approximately 35%. The animal model tMCAO in this study was proved with successful reperfusion by the result that CBF down to 21.3 ± 4.23%, and a CBF up to 52.3 ± 5.86% compared to baseline (Fig. 1c). The effects of BBR on neurological dysfunctions induced by tMCAO were analyzed by the method of Longa, confirming that the score of BBR group decreased significantly compared with vehicle group on days 14, and 28 after tMCAO (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 1d). In addition, Corner test and Rotarod test were conducted to test the sensorimotor function of mice after tMCAO. As shown in Fig. 1e, we found that mice in the BBR group had a lower number of right turns on days 1, 7, and 14 after tMCAO (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively). In the Rotarod test, all mice subjected to surgery showed severe impairment and the time of BBR‐treated mice was significantly longer than that of the vehicle group on days 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 1f). As measured with TTC staining of brain infarction, BBR exhibited a significant reduction in infarction size compared with vehicle group (p < 0.01, Fig. 1h). As expected, administration of BBR diminished more brain water content than vehicle group (p < 0.05, Fig. 1i).

Fig. 1.

The neuroprotective effect of BBR treatment in ischemic stroke. a Timeline for determining the role of BBR in macrophages/microglial polarization and angiogenesis after tMCAO in mice. BBR (50 mg/kg/day) was administrated intragastrically. b, c Representative images of cerebral blood flow during tMCAO and percent change of rCBF compared to baseline in occlusion and reperfusion (n = 6). d Evaluation of neurological deficit on days 1, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO (n = 12–18). e Evaluation of sensorimotor function by corner test on days 1, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO (n = 12–18). f Evaluation of sensorimotor function by Rotarod test on days 1, 7, 14, and 28 after tMCAO (n = 12–18). g Representative images of TTC-stained brain sections of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion mice treated with BBR, vehicle control, or sham at 24 h after tMCAO (n = 8). h Quantification of infarct volume in the vehicle or BBR pretreatment groups. i Quantification of mice brain water content in the vehicle versus BBR groups (n = 6). j Photomicrograph of mice brain tissues region by HE staining. Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifications of the microphotograph, × 20, × 40, respectively. The arrows point to inflammatory infiltrating cells. k Quantification of injured cells in the vehicle or BBR groups (n = 6). Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

HE staining revealed histological changes in the ischemic cortex. As shown in Fig. 1j, sham group showed homogeneous color, with clear and integrated tissue structures. In the vehicle group, a large-scale loss of cerebral structure, absence of neurons, and cytoplasm with red-dyed particles were observed. Inflammatory cell infiltration was also obvious. While in the BBR group, the infarction area was found to be significantly shrunken. Only partial neuronal loss was found in the ischemia center, and the neurons in the cortical area were relatively intact in structure and alignment; inflammatory cell infiltration was also decreased. The percentage of injured cells in ischemic cortex region was significantly lower in BBR group than in vehicle group. (p < 0.01, Fig. 1k) Taken together, these findings indicated that BBR could serve as a feasible agent to attenuate ischemia/reperfusion injury in animal model.

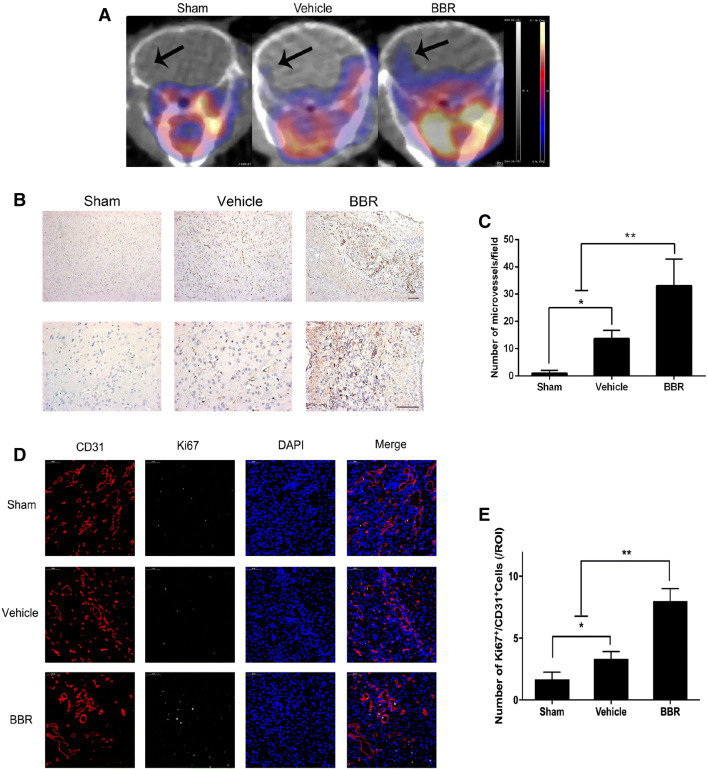

BBR Facilitates Angiogenesis in the Ischemic Brain

To determine whether BBR could promote ischemic cerebral angiogenesis, 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD PET/CT scan was used. As shown in Fig. 2a, cerebral ischemia induced an augment in the uptake of 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD in mice, while a significant upregulated uptake of 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD was observed in BBR group on day 14 after tMCAO. Meanwhile, we counted the number of microvessels stained with CD31 in all groups and found that it was significantly increased in BBR group compared to others on day 14 after tMCAO (p < 0.01 vs. vehicle group, Fig. 2c). In addition, we performed dual-IF staining for the endothelial marker, CD31, and the cell proliferation marker, Ki67. Cells positive dual for CD31/Ki67 were significantly increased in BBR group compared with vehicle group, indicating brain endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenic remodeling (p < 0.01, Fig. 2e). We also found that many Ki67-positive cells were CD31-negative, suggesting the presence of other proliferating cell types. Taken together, these results suggested that BBR could enhance vascular density during the recovery phase following stroke.

Fig. 2.

BBR induced post-ischemic angiogenesis in mice brain. a Above are the coronal sections of the mice in sham group, vehicle group, and BBR group. The colors from yellow to blue represent the uptake of 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD from high to low. The area indicated by the arrow in the diagram is the area of interest (right). b Representative images showing capillary densities by IHC analyses of CD31 in ischemic brain from stroke mice on day 14. Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifications of the microphotograph, × 20, × 40, respectively. c The number of microvessels with staining positive for CD31. d Representative images of immunostaining of the newborn blood vessels (cells dual positive CD31 and Ki67) in ischemic brains from stroke mice on day 14. Scale bar: 50 μm. e Quantitative data of post-ischemic angiogenesis, as indicated by the number of CD31 and Ki67 dual positive cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

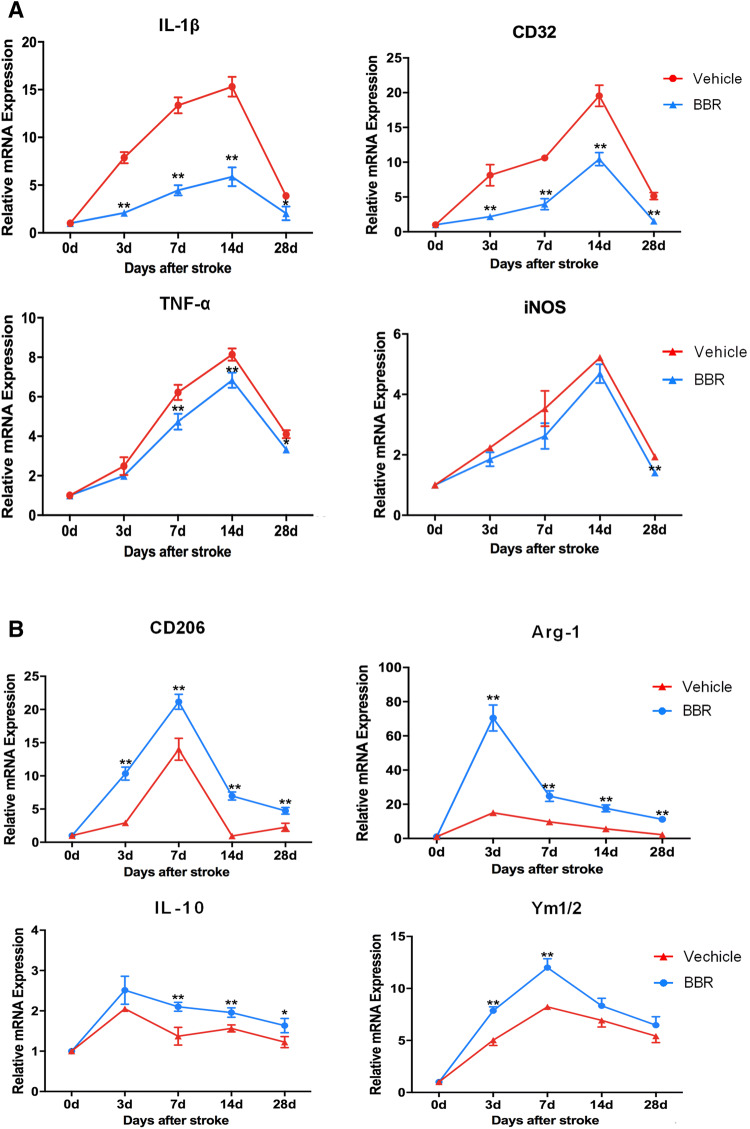

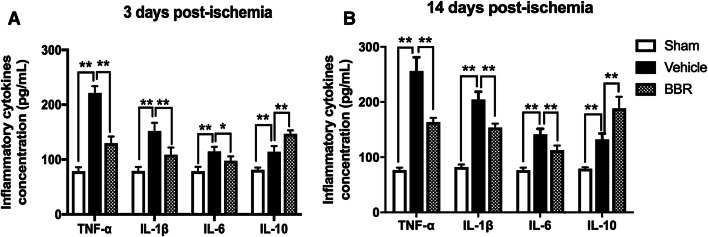

BBR Inhibits M1 Polarization and Promotes M2 Polarization of Microglia/Macrophages

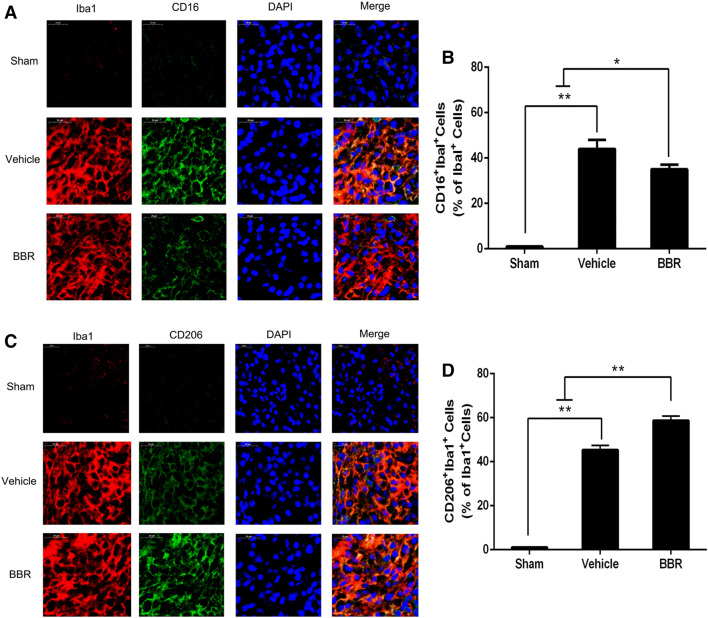

To examine whether BBR could affect macrophage/microglial polarization, RT-PCR was first used to detect mRNA expression levels of M1 phenotype markers (IL-1β, CD32, TNF-α, and iNOS) and M2 phenotype markers (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2). As shown in Fig. 3, compared with the vehicle control, BBR decreased levels of IL-1β (3, 7, and 14 days, p < 0.01; 28 days p < 0.05), CD32 (3, 7, 14, and 28 days, p < 0.01), TNF-α (7, 14, and 28 days, p < 0.01), iNOS (28 days, p < 0.01), and increased levels of CD206 (3, 7, 14, and 28 days, p < 0.01), Arg-1(3, 7, 14, and 28 days, p < 0.01), IL-10 (7 and 14 days, p < 0.01; 28 days, p < 0.05), and Ym1/2 (3 and 7 days, p < 0.01). Then, we performed ELISA to measure the systematic inflammatory cytokines in ischemic brains on days 3 and 14 after tMCAO, showing that BBR reduced the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and increased the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 relative to the vehicle group (Fig. 4). To further verify the RT-PCR and ELISA results, we detected microglial polarization markers by immunofluorescent in the brain after tMCAO. As shown in Fig. 5, the percentage of CD16+Iba1+ cells among total Iba1+ microglia was significantly higher in vehicle-treated mice than in BBR-treated tMCAO mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 5b). Moreover, BBR administration significantly increased the percentage of CD206+Iba1+ M2 microglia after tMCAO (p < 0.05, Fig. 5d). Taken together, these results demonstrated that BBR promoted M2 polarization and inhibited M1 polarization after tMCAO, consistent with the above results.

Fig. 3.

BBR treatment inhibits M1 polarization and promotes M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages after tMCAO. RT-PCR was performed on mRNA collected from ischemic ipsilateral brain on days 3,7,14, and 28 after tMCAO. a BBR decreased the mRNA expression of M1 polarization after tMCAO. b BBR increased the mRNA expression of M2 polarization markers after tMCAO. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Fig. 4.

BBR suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines in ischemic ipsilateral brain on days 3 and 14 after tMCAO. a, b The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10) were measured by ELISA. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Fig. 5.

BBR treatment enhances M2 polarization and suppresses M1 polarization of microglia/macrophages in the ischemic cortex on day 14 after tMCAO. Representative dual-immunofluorescence staining for CD16 or CD206 and Iba-1 markers in brain sections obtained from BBR or vehicle-treated mice on day 14 after tMCAO, or from sham-operated mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. a Cortex sections co-stained for CD16 (M1 marker) (green), Iba-1 (red), and DAPI (blue). b Quantification of the percentage of CD16+/Iba-1+ cells among total Iba-1+ cells. c Cortex sections co-stained for CD206 (M2 marker) (green), Iba-1 (red), and DAPI (blue). d Quantification of the percentage of CD206+/Iba-1+ cell among total Iba-1+ cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

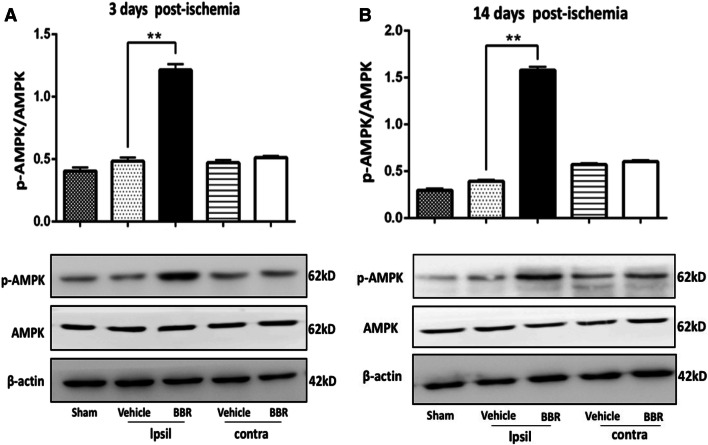

BBR Increases Microglial AMPK Activation Following tMCAO

To investigate the molecular mechanism by which BBR promoted M2 microglia/macrophage, Western blot analysis showed that cerebral-phosphorylated AMPK activation was significantly increased by BBR compared to the vehicle-treated brains on days 3 and 14 in the ipsilateral brain (p < 0.01, Fig. 6a, b). The results suggested that the AMPK signaling pathway was involved in the BBR enhancing M2 microglia/macrophages in the ischemic brains.

Fig. 6.

BBR enhances AMPK activation in the ischemic brain following tMCAO. Western blot was performed using brain tissue on days 3 and 14 after tMCAO or from sham-operated mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. a, b Representative images of Western blot analysis and quantitative data of the ratio of phosphorylated/total AMPK in the ischemic brain. Ipsil: ipsilateral sides, Contra: contralateral sides. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). **p < 0.01

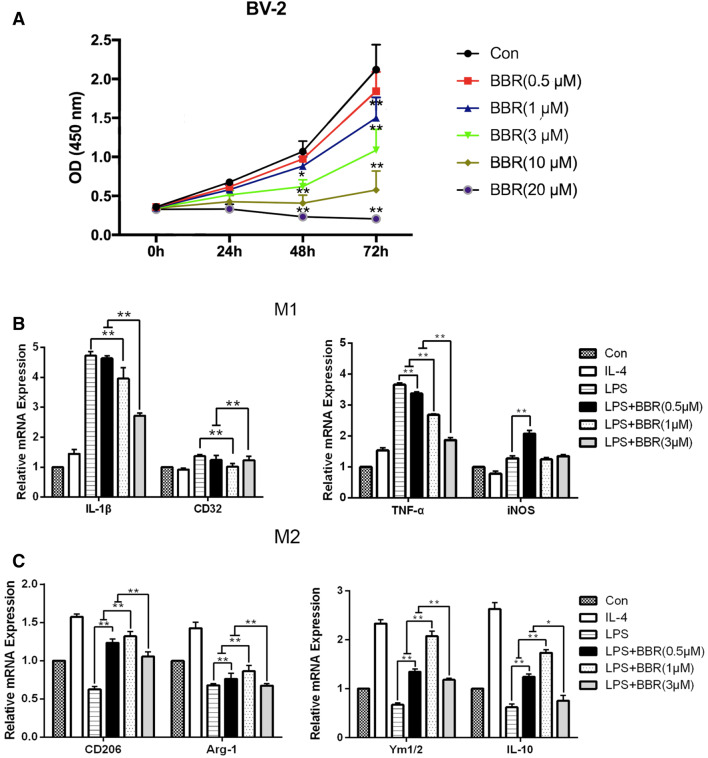

BBR Activated AMPK in LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Cells

The BV-2 microglial cell line was used to further confirm the effects of BBR on microglial polarization in vitro. First, to evaluate the effects of BBR on BV-2 cells proliferation, we conducted CCK-8 assays and found this was greatly reduced by BBR in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7a). To generate a model of macrophage/microglial polarization, M1 phenotype was induced by 100 ng/mL LPS and M2 phenotype was induced by 20 ng/mL IL-4. Thus, we used 0.5,1, and 3 μM BBR to detect the effect on M2 polarization by RT-PCR. The results indicated the mRNA expression of M1 markers (IL-1β, CD32, TNF-α, and iNOS) was increased drastically after stimulation with LPS, but IL-1β, CD32, and TNF-α were remarkably decreased by 3 μM BBR (p < 0.01, Fig. 7b). However, the mRNA expression of iNOS was not notably reduced by BBR. In contrast, the mRNA expression of M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2) was reduced after stimulation with LPS and enhanced after stimulation with IL-4, while 1 μM BBR reversed the reduction of M2 markers obviously compared with LPS stimulation alone (p < 0.01, Fig. 7c). Thus, the optimal and beneficial effects were observed at 1 μM, and as such, this concentration was used in all subsequent experiments to explore the role of BBR in microglial polarization.

Fig. 7.

BBR treatment promotes M2 microglial polarization in BV-2 microglial cells. BV-2 cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 24 h, and then treated with BBR at the concentrations of 0.5, 1, 3, 10, and 20 μM. a Cell viability after BBR treatment was assessed via CCK-8. b and c M1 markers (IL-β, CD32, TNF-α, and iNOS) and M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2) were measured by RT-PCR. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

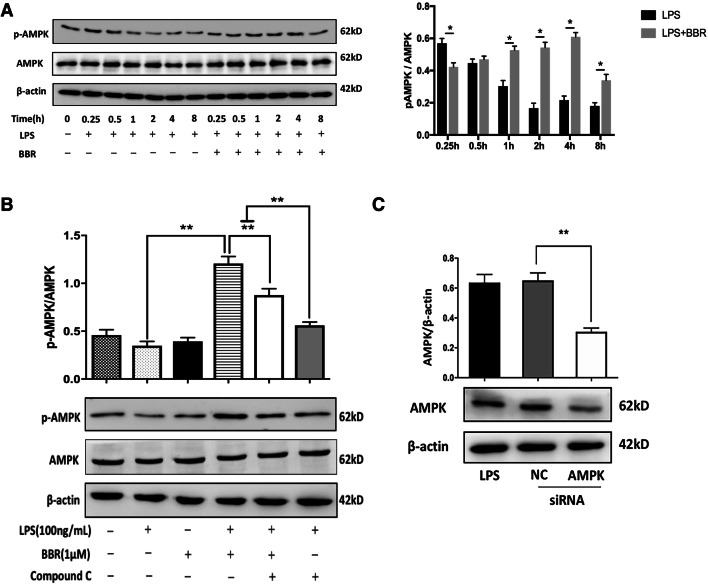

Similar to the in vivo experiments, we examined the expression levels of AMPK and p-AMPK in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells. First, we chose 4 h for the most expression of p-AMPK (Fig. 8a). To further observe the effects of BBR on AMPK, cells were treated with 5 μM Compound C, and the increased expression of p-AMPK by BBR was reversed (p < 0.01, Fig. 8b). Then, we assayed the transfection efficiency of AMPK siRNA and found it could partially silence AMPK (Fig. 8c). Collectively, the in vivo and in vitro results verified that AMPK activation is indispensable for the promotion of macrophage/microglial polarization toward M2 phenotype.

Fig. 8.

BBR increases AMPK activation in LPS-treated BV-2 microglial cells. a Representative images of Western blot analysis for p-AMPK time-dependently manner and quantitative analysis of the ratio of phosphorylated to total AMPK in the time-dependent manner. b Representative images of Western blot analysis for p-AMPK with 1 μM BBR or 5 μM AMPK inhibitor Compound C, respectively, and quantitative analysis of the ratio of phosphorylated to total AMPK. c Representative images of Western blot analysis for the expression of AMPK protein by transfection with 40 nM AMPK siRNA for 48 h and quantitative analysis of the ratio of AMPK to β-actin. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

BBR Promotes M2 Polarization and Inhibits M1 Polarization In Vitro Through AMPK Activation

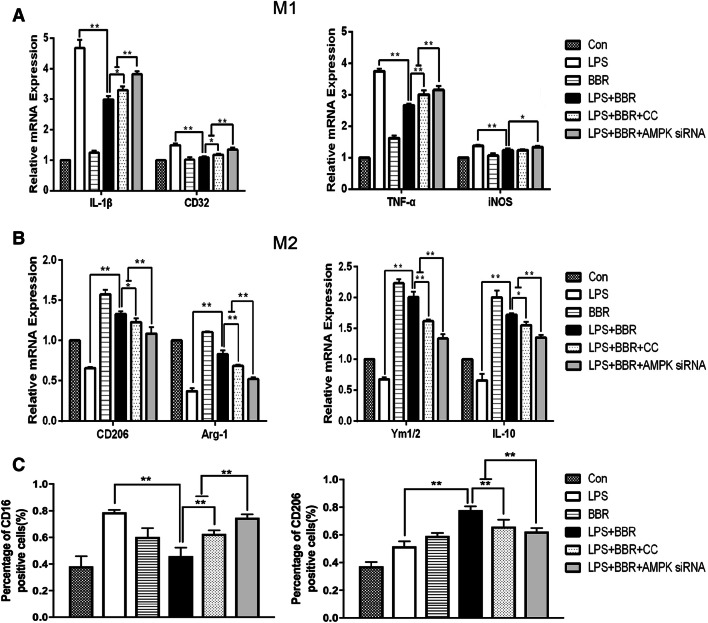

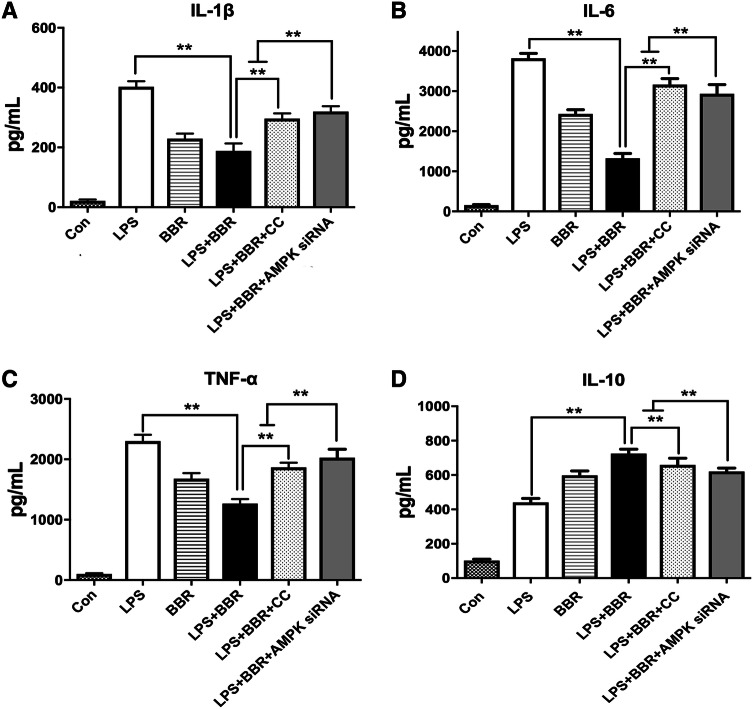

To determine whether BBR could promote M2 polarization dependent on AMPK signaling, the mRNA levels of M1/M2 phenotype were assessed by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 9a, b, BBR-mediated downregulation of M1 markers (IL-β, CD32, and TNF-α) and upregulation of M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2) were all reversed by the AMPK inhibitor and AMPK siRNA, respectively; however, there was no significant difference in iNOS levels after Compound C administration. Meanwhile, we measured the membrane protein expression of CD16/32 and CD206 in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells by flow cytometry. The CD16/32 was significantly downregulated in the LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells treated with BBR, in contrast, the CD206 was significantly upregulated. However, the reversed effect of BBR was observed in use of the AMPK inhibitor or siRNA, respectively, shown in Fig. 9c. To further confirm the effect of BBR, we performed ELISA to measure the release of pro/anti-inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated and various treatment of BV-2 cells. BBR significantly reduced the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6(p < 0.01, Fig. 10a–c) and increased the secretion of IL-10 (p < 0.01, Fig. 10d). However, the reversed effect of BBR was observed in use of the AMPK inhibitor or siRNA. Taken together, our in vitro data demonstrated that BBR promoted M2 polarization and inhibited M1 polarization of microglia through AMPK activation.

Fig. 9.

BBR inhibits M1 polarization and promotes M2 polarization in LPS-activated BV-2 cells, dependent on AMPK signaling. BV-2 were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL), and then treated with 1 μM BBR, 5 μM AMPK inhibitor Compound C, or 40 nM AMPK siRNA, respectively. mRNA expression of M1 markers (a) (TNF-α, IL-1β, CD16, and CD32) and M2 markers (b) (CD206, Arg-1, IL-10, and Ym1/2) were measured by RT-PCR. c Flow cytometry analyses of the effects of BBR on CD16/32 and CD206 protein expression in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Fig. 10.

BBR suppresses inflammatory cytokines in LPS-treated BV-2 microglial cells. BV-2 cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL), and then treated with vehicle or 1 μM BBR or 5 μM AMPK inhibitor Compound C or 40 nM AMPK siRNA. The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines [TNF-α (a), IL-1β (b), IL-6 (c), and IL-10 (d)] were measured by ELISA. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

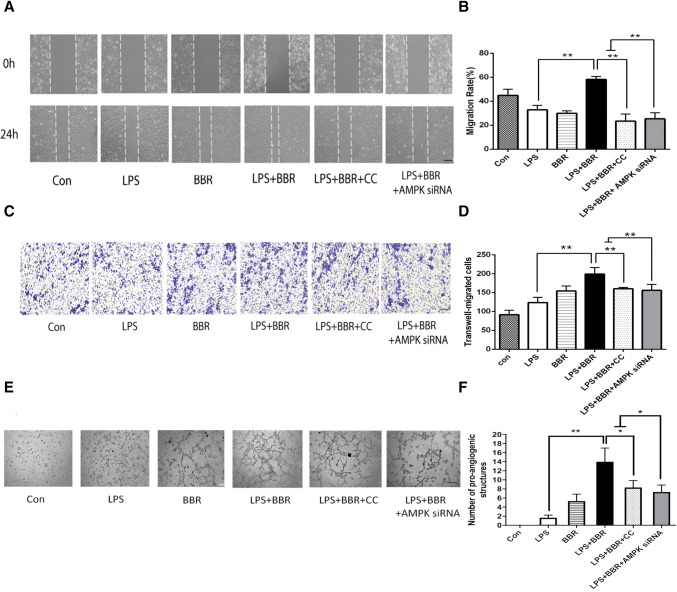

BBR Promotes HUVEC Migration and Tube Formation

In order to determine the effects of BBR via M2 polarization on endothelial cells, we performed scratch wound assay and transwell in HUVEC. As shown in Fig. 11a, c, BBR increased the ability of HUVEC to repair the scratch injury and promoted more migrated number of cells in the transwell assay. As expected, inhibition of AMPK by Compound C or AMPK siRNA reduced cell migrations in HUVEC. In addition, vascular formation ability was examined by Matrigel assay and showed that BBR increased the number of nodes and total tube length compared to Compound C or AMPK siRNA group, indicating its pro-angiogenesis ability (Fig. 11e). Above all, BBR showed these effects in angiogenesis-related process including migration and tube formation.

Fig. 11.

Effects of BBR on in vitro angiogenesis. BV-2 cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL), then treated with vehicle or 1 μM BBR or 5 μM AMPK inhibitor Compound C or 40 nM AMPK siRNA. a BBR promoted HUVEC migration, as evaluated by scratch wound assay and analyzed by the ratio of non-migrated area to the baseline wound area. Scale bar: 50 μm. b Quantitative analysis of migration rate. c The Transwell assay also revealed the same trend as the wound assay and was analyzed by the number of migrated cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. d Quantitative analysis of migrated cells. e Representative images of tube formation of HUVEC cells treated with conditioned media collected from BV-2 cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. f Quantitative data of pro-angiogenic tube structures from HUVEC treated with different conditioned media. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Discussion

It is well known that BBR has anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and antioxidative stress effects against stroke and other neurological diseases (Yang et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016). The present study strikingly demonstrated that this protective effect subjected to ischemic stroke was probably attributed to AMPK-mediated modulation of M2 macrophage/microglial polarization. To our knowledge, this is the first work investigating the function of BBR on angiogenesis by modulating M2 macrophage/microglial polarization through AMPK signaling after stroke.

Of note, numerous studies have proved the importance of microglia switching from M1 to M2 phenotype in response to ischemic insult and the benefits of regulation on microglial M1/M2 phenotype have also catched more attentions recently (Yang et al. 2017; Thakkar et al. 2018). After ischemic stroke, there is an elevation of both M1 and M2 markers in microglia/macrophages, with a M2-dominant phenotype on day 3 and a transition into M1-dominant responses on day 14 (Hu et al. 2012; Suenaga et al. 2015). Therefore, the 14th day was selected to determine the role of BBR on macrophage/microglial polarization and angiogenesis. Consistent with previous findings, when exposed to tMCAO, M0 microglia/macrophages differentiate into “classically activated” M1 phenotypes. After BBR treatment, the increased M1 markers were obviously reduced, except iNOS, whereas the “alternatively activated” M2 phenotypes’ markers were upregulated significantly. To further determine the effects of BBR on modulating microglia M1/M2 polarization, we utilized BV-2 immune cell activated by LPS as an in vitro model of microglial inflammation. Results were coincided with the in vivo results. Collectively, this BBR-induced convert in macrophage/microglial polarization shows functional importance on neuroprotection after stroke.

Accumulated evidence has exhibited that the inflamed microenvironment immensely affects the phenotypic changes in microglia/macrophages, dependent on inflammatory factors (Pan et al. 2015; Hanisch and Kettenmann 2007; Chen et al. 2018). M1 polarization of microglia/macrophages results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which exacerbates stroke-induced brain injury. While M2 polarization results in the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and so on, to promote the regeneration and repair of brain tissue. Blood vessels are essential for all endothelial growth and need to recruit numerous growth factors and cytokines from M2 microglia/macrophages to support their growth (Suarez-Lopez et al. 2018). Clinical studies and experimental outcomes also suggest that M2 microglia/macrophages contribute to angiogenesis, progression, metastasis, and intravasation (Lambertsen et al. 2012; Hu et al. 2014). We obtained similar results indicating that BBR could inhibit release of pro-inflammatory mediators in M1 microglia/macrophage and increase the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators in M2. Hence, the pivotal role of M2 phenotype in promoting brain restorative processes on angiogenesis should be focused. The present study of BBR has further supported long-term functional recovery as well as vascular remodeling effects remarkably. With the rapid development of molecular imaging technology, angiogenesis imaging in ischemic diseases is experiencing a major breakthrough. Several previous studies found NODAGA-RGD illustrated the neo-angiogenesis process with tracer uptake clearly localized in non-FDG-avid perilesional structures (Shu et al. 2017; Haubner et al. 2016). Neo-vessel is characterized by ανβ3 integrin expression at the lesion surface of activated endothelial cells (Van Der Gucht et al. 2016). Therefore, we also observed the condition of new blood vessels in ischemic brain on day 14 after tMCAO by 68Ga-NODAGA-RGD PET/CT. Meanwhile, an in vitro angiogenesis model was used to further verify the related link between the BBR-enhanced M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages and tissue repair. A remarkable increase of angiogenesis can be observed in HUVEC cultured with conditioned media from BBR-polarized microglia. These results are primarily due to the effect of BBR on angiogenesis by enhancing M2 polarization.

There is growing evidence that inflammation involves in the control of metabolic reprogramming and functional phenotypes of immune cells, including microglia. AMPK, a heterotrimeric serine/threonine kinase, has been proposed to inhibit inflammation of macrophage, microglia, and astrocytes (Sekar et al. 2018; Ji et al. 2018), and recently it has been verified to promote the alternative activation of M2 microglia/macrophages (Li et al. 2018a). In line with our study, p-AMPK levels were notably elevated after treatment by BBR, and innovatively established the relationship between AMPK activation and BBR-enhanced M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages in experimental stroke. However, AMPK can be activated by various forms of stress, including liver kinase B1 (LKB1), calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase kinase beta (CaMKKβ), and low ATP/AMP ratios (Zhang et al. 2018). In addition, AMPK is an upstream kinase that regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation, a ligand-activated nuclear receptor with the capability of anti-inflammation and energy regulation (Yazawa et al. 2010). Therefore, it is exciting for us to further investigate the detailed link between BBR-induced AMPK activation and M2-polarized pro-angiogenesis.

Conclusions

This work demonstrated that BBR could enhance the post-ischemic M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages in the ischemic brain and improve angiogenesis following tMCAO. In total, BBR may serve as a potent therapeutic agent to promote functional recovery for ischemic stroke and other neurological diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81773987 to YZ), Program of Nanjing Health and Family Planning Commission (YKK188107), and Hospital Pharmaceutical Research Program of Nanjing Pharmaceutical Commission (2017YX001). We would like to thank Prof. Hongguang Xie (Nanjing First Hospital) and Dr. Bangshun He (Nanjing First Hospital) for their informative advice.

Abbreviations

- BBR

Berberine

- tMCAO

Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- CI/RI

Cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury

- CNS

Central nervous system

- AMPK

Adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- CCA

Common carotid artery

- ECA

External carotid artery

- ICA

Internal carotid artery

- MCA

Middle cerebral artery

- rCBF

Regional cerebral blood flow

- TTC

2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- HE

Hematoxylin eosin

- OSEM3D

3-Dimensional ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene difluoride

- TBST

TBS-Tween20

- DM

Conditioned medium

- LKB1

Liver kinase B1

- CaMKKβ

Calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase kinase beta

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

Author Contributions

All authors listed contributed immensely to this study. YZ, YL, and JZ conceived and designed the study. DC, CG, and ML performed the experiments. JW, JZ, FW, and YZ analyzed the data. JZ and DC wrote the paper. YZ, WF, and YL reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Junrong Zhu, Dingwen Cao, and Chao Guo have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yingdong Zhang, Email: zhangyingdong@aliyun.com.

Weirong Fang, Email: weirongfang@163.com.

Yunman Li, Email: yunmanli@cpu.edu.cn.

References

- Chen G, Liu S, Pan R, Li G et al (2018) Curcumin attenuates gp120-induced microglial inflammation by inhibiting autophagy via the PI3K pathway. Cell Mol Neurobiol 38(8):1465–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganta VC, Choi MH, Kutateladze A, Fox TE et al (2017) A MicroRNA93-interferon regulatory factor-9-immunoresponsive gene-1-itaconic acid pathway modulates M2-like macrophage polarization to revascularize ischemic muscle. Circulation 135(24):2403–2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H (2007) Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci 10(11):1387–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R, Finkenstedt A, Stegmayr A, Rangger C et al (2016) [68 Ga]NODAGA-RGD—metabolic stability, biodistribution, and dosimetry data from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43(11):2005–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H et al (2012) Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 43(11):3063–3070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Leak RK, Shi Y, Suenaga J et al (2014) Microglial and macrophage polarization—new prospects for brain repair. Nat Rev Neurol 11(1):56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Huang Q, Wang F, Milner R et al (2016) Cerebral ischemia-induced angiogenesis is dependent on tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-mediated upregulation of α5β1 and αVβ3 integrins. J Neuroinflammation 13(1):227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten N, Verbruggen S, Gijbels MJ, Post MJ, De Winther MP, Donners MM (2014) Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis 17(1):109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Xue TF, Guo XD, Yang J et al (2018) Antagonizing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma facilitates M1-to-M2 shift of microglia by enhancing autophagy via the LKB1-AMPK signaling pathway. Aging Cell 17(4):e12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Wang H, Jin M, Yang X et al (2018) Exosomes from MiR-30d-5p-ADSCs reverse acute ischemic stroke-induced, autophagy-mediated brain injury by promoting M2 microglial/macrophage polarization. Cell Physiol Biochem 47(2):864–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Cheng J, Liu Y, Wu J et al (2014) Improvement of functional recovery by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced alternative activation of microglia/macrophages and increased angiogenesis and neurogenesis following experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun 40:131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabba JA, Xu Y, Christian H, Ruan W et al (2018) Microglia: housekeeper of the central nervous system. Cell Mol Neurobiol 38(1):53–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S et al (1994) Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke 25(9):1794–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen KL, Biber K, Finsen B (2012) Inflammatory cytokines in experimental and human stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32(9):1677–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Zhang C, Zhou H, Feng Y et al (2018a) Inhibitory effects of betulinic acid on LPS-induced neuroinflammation involve M2 microglial polarization via CaMKKβ-dependent AMPK activation. Front Mol Neurosci 11:98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liao Y, Gao L, Zhuang T et al (2018b) Coronary serum exosomes derived from patients with myocardial ischemia regulate angiogenesis through the miR-939-mediated nitric oxide signaling pathway. Theranostics 8(8):2079–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Zhang N (2018) Berberine: pathways to protect neurons. Phytother Res 32(8):1501–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-Y, Huang B-R, Yeh W-L, Lee C-H et al (2014) Antineuroinflammatory effects of lycopene via activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-α1/heme oxygenase-1 pathways. Neurobiol Aging 35(1):191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang Y, Akamatsu Y, Lee CC et al (2014) Vascular remodeling after ischemic stroke: mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Prog Neurobiol 115:138–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Ran Y, Huang S, Wen S et al (2017) Curcumin protects against ischemic stroke by titrating microglia/macrophage polarization. Front Aging Neurosci 9:233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wen S, Yan F, Liu K et al (2018) Salidroside provides neuroprotection by modulating microglial polarization after cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25(4):402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R (1989) Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20(1):84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D-Y, Tang C-H, Chen Y-H, Wei IH (2010) Berberine suppresses neuroinflammatory responses through AMP-activated protein kinase activation in BV-2 microglia. J Cell Biochem 110(3):697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madelaine R, Sloan SA, Huber N, Notwell JH et al (2017) MicroRNA-9 couples brain neurogenesis and angiogenesis. Cell Rep 20(7):1533–1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manavski Y, Lucas T, Glaser SF, Dorsheimer L et al (2018) Clonal expansion of endothelial cells contributes to ischemia-induced neovascularization. Circ Res 122(5):670–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Jin JL, Ge HM, Yin KL et al (2015) Malibatol A regulates microglia M1/M2 polarization in experimental stroke in a PPARgamma-dependent manner. J Neuroinflammation 12:51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sag D, Carling D, Stout RD, Suttles J (2008) Adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase promotes macrophage polarization to an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype. J Immunol 181(12):8633–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar P, Huang DY, Hsieh SL, Chang SF et al (2018) AMPK-dependent and independent actions of P2X7 in regulation of mitochondrial and lysosomal functions in microglia. Cell Commun Signal 16(1):83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto SW, Chang D, Jenkins A, Bensoussan A et al (2016) Angiogenesis in ischemic stroke and angiogenic effects of Chinese herbal medicine. J Clin Med 5(6):56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu S, Zhang L, Zhu YC, Li F et al (2017) Imaging angiogenesis using (68)Ga-NOTA-PRGD2 positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with severe intracranial atherosclerotic disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37(10):3401–3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn E, Kim Y, Lim H-S, Kim B-Y et al (2019) Hwangryunhaedok-tang exerts neuropreventive effect on memory impairment by reducing cholinergic system dysfunction and inflammatory response in a vascular dementia rat model. Molecules 24(2):343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez L, Sriram G, Kong YW, Morandell S et al (2018) MK2 contributes to tumor progression by promoting M2 macrophage polarization and tumor angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(18):E4236–E4244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga J, Hu X, Pu H, Shi Y, Hassan SH, Xu M, Leak RK, Stetler RA, Gao Y, Chen J (2015) White matter injury and microglia/macrophage polarization are strongly linked with age-related long-term deficits in neurological function after stroke. Exp Neurol 1(272):109–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar R, Wang R, Wang J, Vadlamudi RK et al (2018) 17β-Estradiol regulates microglia activation and polarization in the hippocampus following global cerebral ischemia. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018:4248526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Gucht A, Pomoni A, Jreige M, Allemann P et al (2016) 68 Ga-NODAGA-RGDyK PET/CT imaging in esophageal cancer. Clin Nucl Med 41(11):e491–e492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Huang Y, Xu Y, Ruan W, Wang H, Zhang Y, Saavedra JM, Zhang L, Huang Z, Pang T (2018) A dual AMPK/Nrf2 activator reduces brain inflammation after stroke by enhancing microglia M2 polarization. Antioxid Redox Signal 28(2):141–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang B, Xiao C, Shen T, Li X (2018) Anti-inflammatory effects of anisalcohol on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV2 microglia via selective modulation of microglia polarization and down-regulation of NF-κB p65 and JNK activation. Mol Immunol 95:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X-Y, Liu L, Yang Q-W (2016) Functions and mechanisms of microglia/macrophages in neuroinflammation and neurogenesis after stroke. Prog Neurobiol 142:23–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liu H, Zhang H, Ye Q et al (2017) ST2/IL-33-dependent microglial response limits acute ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 37(18):4692–4704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Yan H, Li S, Zhang M (2018) Berberine ameliorates MCAO induced cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via activation of the BDNF-TrkB-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Neurochem Res 43(3):702–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa T, Inaoka Y, Okada R, Mizutani T et al (2010) PPAR-γ coactivator-1α regulates progesterone production in ovarian granulosa cells with SF-1 and LRH-1. Mol Endocrinol 24(3):485–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Y-C Wang, Dzyubenko E, Sanchez-Mendoza EH, Sardari M et al (2018) Postacute delivery of GABAa α5 antagonist promotes postischemic neurological recovery and peri-infarct brain remodeling. Stroke 49(10):2495–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Bian H, Guo L, Zhu H (2016) Pharmacologic preconditioning with berberine attenuating ischemia-induced apoptosis and promoting autophagy in neuron. Am J Transl Res 8(2):1197–1207 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wang C, Shi H, Wu D et al (2018) Extracellular degradation into adenosine and the activities of adenosine kinase and AMPK mediate extracellular NAD + -produced increases in the adenylate pool of BV2 microglia under basal conditions. Front Cell Neurosci 12:343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-r Lu, H-d Guo C, W-r Fang et al (2018) Berberine attenuates ischemia–reperfusion injury through inhibiting HMGB1 release and NF-κB nuclear translocation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 39:1706–1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]