Abstract

CKLF1 is a chemokine with increased expression in ischemic brain, and targeting CKLF1 has shown therapeutic effects in cerebral ischemia model. Microglia/macrophage polarization is a mechanism involved in poststroke injury expansion. Considering the quick and obvious response of CKLF1 and expeditious evolution of stroke lesions, we focused on the effects of CKLF1 on microglial/macrophage polarization at early stage of ischemic stroke (IS). The present study is to investigate the CKLF1-mediated expression of microglia/macrophage phenotypes in vitro and in vivo, discussing the involved pathway. Primary microglia culture was used in vitro, and mice transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model was adopted to mimic IS. CKLF1 was added to the primary microglia for 24 h, and we found that CKLF1 modulated primary microglia skew toward M1 phenotype. In mice transient IS model, CKLF1 was stereotactically microinjected to the lateral ventricle of ischemic hemisphere. CKLF1 aggravated ischemic injury, accompanied by promoting microglia/macrophage toward M1 phenotypic polarization. Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines were observed in mice subjected to cerebral ischemia and administrated with CKLF1. CKLF1−/− mice were used to confirm the effects of CKLF1. CKLF1−/− mice showed lighter cerebral damage and decreased M1 phenotype of microglia/macrophage compared with the WT control subjected to cerebral ischemia. Moreover, NF-κB activation enhancement was detected in CKLF1 treatment group. Our results demonstrated that CKLF1 is an important mediator that skewing microglia/macrophage toward M1 phenotype at early stage of cerebral ischemic injury, which further deteriorates followed inflammatory response, contributing to early expansion of cerebral ischemia injury. Targeting CKLF1 may be a novel way for IS therapy.

Keywords: CKLF1, CCR4, Ischemic stroke, Microglia/macrophage, Polarization

Introduction

Ischemic stroke (IS), a debilitating and devastating disease, leads to severe morbidity and mortality worldwide (Cramer et al. 2017). Multiple mechanism is involved in this complex progression, including inflammatory reaction (Jin et al. 2013), toxicity of excitatory amino acids (Huang et al. 2017), cellular signal transduction including Ca2+ overload and NO damage (Chen et al. 2017), oxygen free radical production (Nash et al. 2018), etc. More recently, microglia/macrophage polarization dysregulation is found to be a novel mechanism for cerebral ischemia induced injury (Hu et al. 2012). Microglia/macrophage show two phenotypes, one is pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype characterized by releasing inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and NO, which often associated with poor outcome. The other is anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype characterized by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which is considered with neuroprotective effects (Ma et al. 2017). The dual roles of polarized microglia/macrophages are seen in several CNS disorders including multiple sclerosis (Parsa et al. 2016), spinal cord injury (David and Kroner 2011), and intracerebral hemorrhage (Lan et al. 2017). When cerebral ischemia occurs, the resident microglia and macrophages recruited from periphery to brain initiate polarization, causing deleterious pathological responses to aggravate the ischemic damage. Selective modulation of microglia/macrophage polarization by inhibiting M1 phenotype or skewing toward M2 phenotype may be a potential therapeutic strategy for treating cerebral ischemia. It is urgent to clarify the factors that dominate the microglia/macrophage polarization in IS setting. The M1/M2 classification has served to set an experimental framework for examination of microglial/macrophage function and inflammation, while there is a growing literature demonstrating different activation pathways outside the traditional M1/M2 phenotype. This has led to the proposal that microglia and macrophages be classified based on more complex standards (Murray et al. 2014). In this research, we studied the effects of CKLF1 in the established M1/M2 experimental system and built a foundation for future detailed research.

Chemokine-like factor 1 (CKLF1) is a chemokine with multiple biological activities (Han et al. 2001). Our previous studies have found significant increase in CKLF1 expression in damaged brain as early as 3 h after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), peaking at day 2 in cerebral ischemic rats (Kong et al. 2011). Moreover, applying C19, an antagonist peptide of CKLF1, can improve cerebral ischemia injury in rats (Kong et al. 2012). In addition, administration of anti-CKLF1 antibody also shows beneficial effects with decreased infarction and better neurological behavior in rats (Kong et al. 2014). According to these results, we postulate that targeting CKLF1 and decreasing its expression at acute stage may be a therapeutic way for IS. However, it still remains unclear the specific function of increased CKLF1 at acute stage in IS. In this study, we determined the effects of CKLF1 from the aspect of microglia/macrophage polarization. We firstly demonstrated that CKLF1 can modulate microglia/ macrophage toward an M1 phenotypic polarization at acute stage in IS and further deteriorates inflammatory response, leading to expansion of cerebral damage finally.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The CKLF1 peptide (Aliyrkllfnpsgpyqkkpvhekkevl, AL-27) with a purity of 97.99% was provided by GL Biochem (Shanghai, China).

Cell Culture

Primary cultures of microglial cells were obtained from brains of newborn C57BL/6 mice (0–24 h) by modified methods based on previous report (Shao et al. 2015). Briefly, brain cortices were mechanically dissociated and suspended in DMEM/F12 with Glutamax I (Gibco, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin. Cells obtained from three mice brains were seeded at a T75 culture flask and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% O2, with half medium replacement every 3 days. Microglia were shaken off at 200 rpm for 4 h after 10 days culture. The isolated primary microglia were seeded in 24-well plates or 6-well plates at a desired density. For M1 induction, lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 100 ng/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ; 20 ng/ml, PeproTech, NJ, USA) were added to the microglial cultures for indicated time. For M2 induction, IL-4 (20 ng/ml, PeproTech, NJ, USA) was used. For CKLF1 stimuli, 1, 10, and 100 nM CKLF1 were added in medium separately, and microglia were collected after 24 h for subsequent assays. C 021 dihydrochloride (Cat# 3581, Tocris Bioscience) 1, 10, 100 nM and DAPTA (Cat# ab120810, Abcam) 1, 10, 100 nM were applied at the same time with CKLF1 for 24 h in the inhibitors experiments. For the experiments treated with both M1 and M2 stimuli, microglia were first treated with IL-4 for 24 h and then LPS plus IFN-γ were added for 12 h with or without CKLF1 (100 nM).

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (20–25 g) were purchased from SiBeiFu (Beijing). CKLF1−/− mice were kindly provided by Professor Zhang (Key Laboratory of Human Disease Comparative Medicine, NHFPC, Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking Union Medicine College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences). All of the procedures were in accordance with the standards established in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources of the National Research Council (US) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Peking Union Medical College and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Animals were housed in a climate-controlled room under a 12/12-h reverse light/dark cycle (lights off at 11:00 h), and food and water were provided ad libitum throughout the study.

Mice MCAO Model and Stereotaxic Microinjection

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane for induction and maintained with 1.5% isoflurane, 70% N2O, and 30% O2 via a face mask. Vehicle, CKLF1, and LPS plus IFN-γ were injected into the rat brain in the peri-ischemic lateral ventricle before MCAO procedure. Briefly, Bregma was chosen as the origin of coordinate axis, and a tiny hole was drilled at the stereotaxic coordinates: (AP: 2.3 mm, LM: 3.0 mm). 2 µl reagents was injected into the brain tissue at a depth of 4.0 mm using a 5-µl microinjector at the rate of 0.4 µl/min. The needle remained in position for 5 min before removal to ensure a complete dispersion of the liquids.

Focal cerebral ischemia was produced by intraluminal occlusion of the right MCA for 60 min as previously described (Jin et al. 2014). Anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% isoflurane, 70% N2O, and 30% O2 via a face mask. The rectal temperature of mice was controlled at 37.0 ± 0.5 °C via a temperature regulated heating pad during surgery. The right MCA was occluded with a nylon monofilament with silicone-coated tip, resulting in severe reduction (> 70%) of blood flow to the MCA region, which was recorded by transcranial laser-Doppler flowmetry. The monofilament was retracted after 60 min, allowing reperfusion to occur. Reperfusion was confirmed by an increase in regional cerebral blood flow, which was measured by transcranial laser-Doppler flowmetry. Concurrent Sham-operated control animals underwent all procedures except ligation of arteries and insertion of the monofilament. Mice were monitored until they regained consciousness and were then returned to their cages.

In wild-type (WT) mice study, mice were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: (1) Sham (n = 18), non-MCAO controls given vehicle, (2) CKLF1-Sham (n = 18), non-MCAO controls given CKLF1 (10 µg), (3) model (n = 18), animals subjected to MCAO given vehicle, (4) LPS + IFN-γ (n = 18), animals subjected to MCAO given LPS plus IFN-γ, (5) CKLF1 0.1 µg (n = 18), animals subjected to MCAO given CKLF1 (0.1 µg), (6) CKLF1 1 µg (n = 18), animals subjected to MCAO given CKLF1 (1 µg), (7) CKLF1 10 µg (n = 18), animals subjected to MCAO given CKLF1 (10 µg).

In CKLF1−/− mice study, mice were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: (1) WT Sham (n = 9), non-MCAO WT controls given vehicle, (2) WT CKLF1-Sham (n = 9), non-MCAO WT controls given CKLF1 (10 µg), (3) WT model (n = 9), WT animals subjected to MCAO given vehicle, (4) WT CKLF1-model (n = 9), WT animals subjected to MCAO given CKLF1 (10 µg), (5) KO Sham (n = 9), non-MCAO CKLF1−/− controls given vehicle, (6) KO CKLF1-Sham (n = 9), non-MCAO CKLF1−/− controls given CKLF1 (10 µg), (7) KO model (n = 9), CKLF1−/− animals subjected to MCAO given vehicle, (8) KO CKLF1-model (n = 9), CKLF1−/− animals subjected to MCAO given CKLF1(10 µg).

Evaluation of Neurological Deficit

The neurological deficits of mice were assessed by Zea Longa test in a blinded manner as previously described (Wang et al. 2018). 0: no neurological deficit, 1: failure to extend left forepaw fully, 2: circling to the left, 3: falling to the left, 4: failure to walk spontaneously or no consciousness, 5: death.

Infarct Volume by TTC Staining

Mice were sacrificed at 24 h after reperfusion, and the brains were cut into six 1-mm-thick slices. The sections were stained using 1% (w/v) 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min on each side at 37 °C and further fixed in 10% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 24 h. The brain slices were placed as followed order: the first slice is the side of the olfactory bulb up, and the last one is the brainstem side down. The images were photographed, and the infarct and edema ratio were blindly analyzed across the sections with image analysis software by an experimenter who was blinded to the group information. The infarction was analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA): infarct ratio (%) = total infarct area/total section area × 100, edema ratio (%) = left brain area/right brain area × 100.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI Scans were Performed at 24 h After the Reperfusion

The animals were anaesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and fixed in a body restrainer with tooth-bar in an MRI spectrometer (PharmaScan 70/16, Bruker, Germany). Their brains were scanned using a mice head surface coil. T2-weighted images were acquired with the following parameters: repetition time 5 min, matrix size 256 × 256 pixels, field of view 23 × 23 mm, acquisition time 10 min, slice thickness 0.5 mm, TR = 2800 ms, TEeff = 35 ms. Hyperintense infarct areas in T2-weighted images were assigned with a region of interest tool and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software: infarct ratio (%) = total infarct area/total section area × 100%, edema ratio (%) = left brain area/right brain area × 100%.

Nissl Staining

Nissl staining was performed with Cresyl Violet, which can selectively stain the Nissl body in survival neurons. Mice were sacrificed under anesthesia at 24 h after reperfusion, and then immediately perfused by cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) and 4% (w/v) PFA. The brains were removed and immersed in fixative and then embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections (5 µm) were cut on glass slides, stained with 1% Cresyl Violet dissolved in 0.25% acetic acid, and examined under a light microscope (CKX41, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) by a pathologist blinded to the study groups.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Staining

For cultured microglia, cell immunofluorescence staining was performed as follows: cells were grown on cover slips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 24-well plates, fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min, and washed for 5 min three times with PBS. Cells were permeabilized by 0.1% (v/v) Triton-X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min and blocked by 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the followed primary antibodies: rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500, Cat# 019-19741, RRID: AB_839504, Wako Chemical), rat anti-CD16/32 (1:100, Cat# 553141, RRID: AB_394656, BD Biosciences Pharmingen), and goat anti-CD206 (1:200, Cat# AF2535, RRID: AB_2063012, R&D Systems). After washed with PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and sealed with 90% (v/v) glycerol. The secondary antibodies are Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), Alexa 546-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and Cy3-labeled goat anti-rat IgG (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China).

For brain tissues, the brains were fixed in 4% (v/v) PFA, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization, endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by 3% (w/v) H2O2 for 10 min at 37 °C (only immunohistochemistry need H2O2-block step). Then, the slices were permeabilized by 0.1% (v/v) Triton-X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature followed by PBS washing. After blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA for 1 h, slices were then treated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies are rabbit anti-CKLF1 (1:500, Cat# ab180512, Abcam) (for immunohistochemistry staining), and same as culture microglia (for immunofluorescence staining). After washing three times in PBST (0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 in PBS), the slices were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig G (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 2 h (for immunohistochemistry staining) and for 1 h for secondary antibodies same as culture microglia (for immunofluorescence staining). The expression of CKLF1 was detected with 3, 3-diaminobenzidin (DBA) as the substrate. At last, cells or slices were captured using a microscope (CKX41, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (for immunohistochemistry staining) or a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP2, Leica, Solms, Germany) (for immunofluorescence staining) in a blinded manner. The images were analyzed by using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from ischemic brains using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 µg of total RNA according to the manufactures’ instruction. The amplification of cDNA was performed with Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Foster City, CA, USA) using TransStart Tip Green qPCR Supermix kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 30 s for pre-denaturation, 94 °C for 5 s and 53 °C for 30 s to denaturation, and at 72 °C for 10 s for 40 cycles to extension. The mRNA level of individual genes was normalized to the expression of GAPDH housekeeping control gene for each sample and calculated using the ΔΔCT method. The primers used for each target gene are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for qPCR analysis

| Genes | Primers | |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | ||

| iNOS | SENS: CAAGCACCTTGGAAGAGGAG | |

| REVS: AAGGCCAAACACAGCATACC | ||

| CD16 | SENS: TTTGGACACCCAGATGTTTCAG | |

| REVS: GTCTTCCTTGAGCACCTGGATC | ||

| CD32 | SENS: AATCCTGCCGTTCCTACTGATC | |

| REVS: GTGTCACCGTGTCTTCCTTGAG | ||

| M2 | ||

| Arg1 | SENS: TCACCTGAGCTTTGATGTCG | |

| REVS: CTGAAAGGAGCCCTGTCTTG | ||

| CCL-22 | SENS: CTGATGCAGGTCCCTATGGT | |

| REVS: GCAGGATTTTGAGGTCCAGA | ||

| TGF-internal control | SENS: TGCGCTTGCAGAGATTAAAA | |

| REVS: CGTCAAAAGACAGCCACTCA | ||

| GAPDH | SENS: TCATTGACCTCAACTACATGGT | |

| REVS: CTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCAG |

Western Blot Analysis

Ischemic brains were prepared for western blot as previously described (Zuo et al. 2016). Briefly, tissue samples were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were assessed with a BCA kit (Applygen, Beijing, China). Proteins (40 µg for each sample) were separated on 15% (w/v) SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% (w/v) BSA, the membranes were blotted with primary antibodies as follows overnight at 4 °C: anti-IL-1β (1:500, Cat# sc-7884, RRID:AB_2124476, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-TNF-α (1:500, Cat# ab6671, RRID:AB_305641, Abcam), anti-TGF-β (1:500, Cat# ab64715, RRID:AB_1144265, Abcam), anti-BDNF (1:500, Cat# sc-546, RRID:AB_630940, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1000, Cat# sc-109, RRID:AB_632039, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Phospho-NF-κB p65 Ser536 (1:1000, Cat# 3036S, RRID:AB_331281, Cell Signaling Technology). β-Actin (1:1000, CST, Cat# sc-47778, RRID: AB_626632) was measured as loading control. Then secondary antibodies Affinity Purified Antibody Peroxidase Labeled Goat anti-Rabbit IgG H&L and Peroxidase-Labeled Streptavidin were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. The expression of each protein was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence plus detection system (Molecular Device, Lmax). The density of each band was quantified using image analysis software Gel-Pro Analyzer (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All of the data were expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed by GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The statistical analysis used in this study is Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, and two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

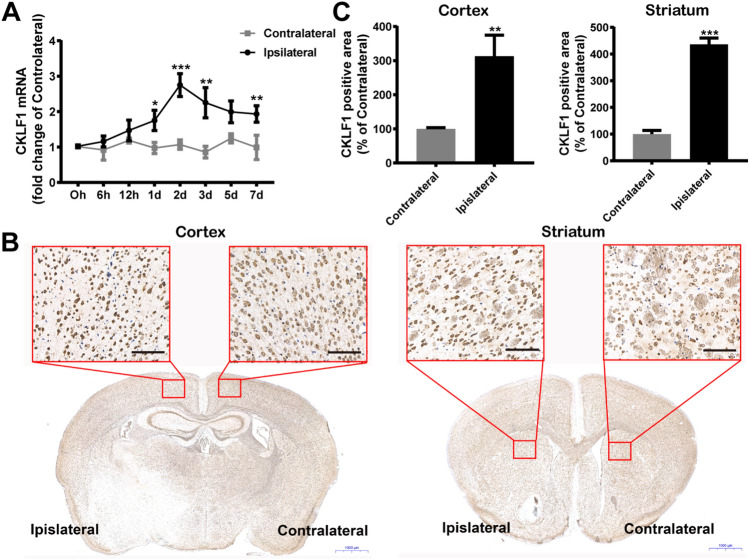

Increased Expression of CKLF1 in Ischemic Brains of Mice

We investigated the expression of CKLF1 in mice brain suffered with MCAO treatment. qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA expression of CKLF1 in ipsilateral brains increased significantly poststroke compared with contralateral brains, initiating at 6 h and peaking at 2 day (Fig. 1a). CKLF1 showed markedly higher expression in cortex and striatum of ipsilateral brain compared with the contralateral brain determined by immunohistochemistry staining (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

CKLF1 increases in ischemic brain. a qPCR analysis of dynamic expression of CKLF1 in ipsilateral and contralateral brains of mice subjected to MCAO at different time points (n = 6 mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus contralateral. b Immunohistochemical staining of CKLF1 in cortex and striatum of ipsilateral and contralateral brains of mice 24 h after MCAO. Scale bars 100 µm. c Quantitative analysis of CKLF1 expression in cortex and striatum of ipsilateral and contralateral brains of mice 24 h after MCAO (n = 6 mice). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus contralateral

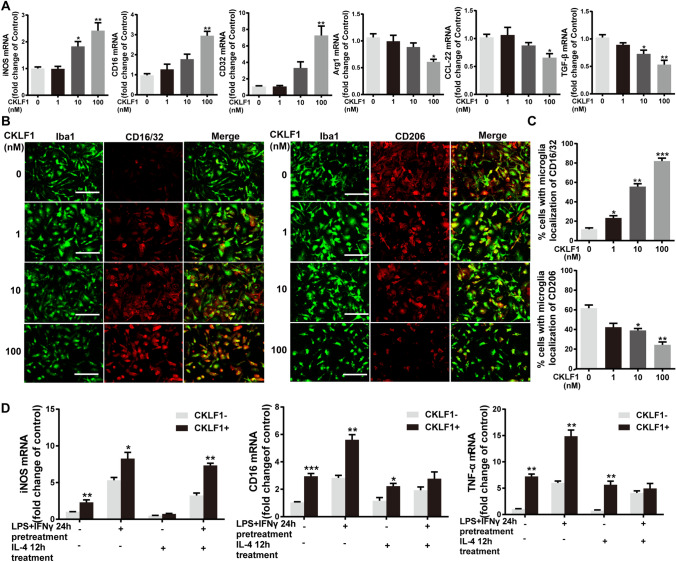

CKLF1 Modulates Microglia Polarize Toward M1 Phenotype In Vitro

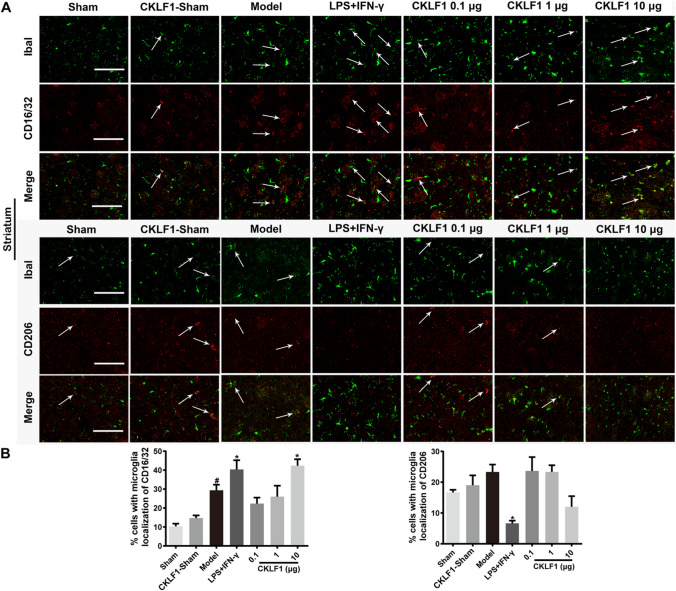

To examine the effects of CKLF1 on microglia polarization, qPCR analysis and immunofluorescence staining were applied for detecting M1 and M2 markers. CKLF1 increased the mRNA expression of iNOS, CD16 and CD32, which characterized as M1 markers with a dose-dependent manner in microglia. The expression of Arg1, TGF-β and CCL-22 characterized as M2 markers showed decreased expression when stimulated with CKLF1 (Fig. 2a). Moreover, the immunofluorescence intensity of CD16/32, a common marker for M1 polarization in immunofluorescence analysis, showed enhancement after CKLF1 treatment. While the immunofluorescence intensity of M2 marker CD206 showed attenuation to CKLF1 stimulation (Fig. 2b, c). Further, we performed a study to determine the effects of CKLF1 on the dynamics between M1 and M2 polarization. We found the CKLF1 enhanced the LPS plus IFN-γ induced M1 polarization, suppress the IL-4 induced M2 polarization in primary microglia (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

CKLF1 modulates the microglia M1/M2 polarization in vitro. a qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of M1 markers (iNOS, CD16, CD32) and M2 markers (Arg1, CCL-22, TGF-β) in primary microglia treated with indicated concentration of CKLF1 for 24 h (n = 6 cell samples). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control. b Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in primary microglia treated with CKLF1 for 24 h. c Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia (n = 6 cell samples). Scale bars 100 µm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control. d qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of M1 markers in microglia treated with IL-4 (20 ng/ml) for 12 h and subsequent LPS (100 ng/ml) plus IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) with or without CKLF1 (100 nM) for 24 h (n = 6 cell samples). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus CKLF1-

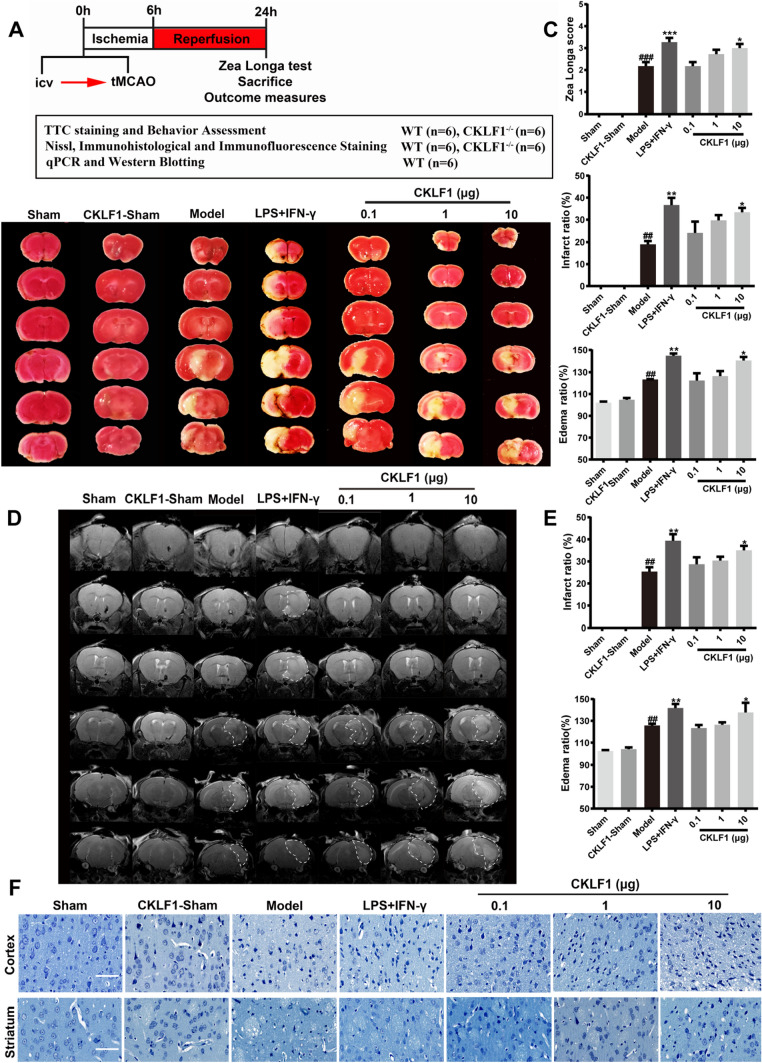

CKLF1 Aggravates the Cerebral Ischemia Injury at Early Stage in Mice MCAO Model

A study was designed to investigate the effects of excessive CKLF1 at early stage of cerebral ischemia. Mice were stereotaxic injected with vehicle, CKLF1 or LPS plus IFN-γ (positive control for M1 polarization), followed by MCAO, and then sacrificed after 24 h for outcomes measures (Fig. 3a). To investigate the effects of CKLF1 on cerebral ischemia injury, TTC staining and neurological behavior test were performed. LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 treatment increased the MCAO induced brain infarction (Fig. 3b). The infarction ratio and edema ratio all increased in LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 treated MCAO mice. LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 also significantly worsen the neurological deficits in MCAO model compared with mice received vehicle (Fig. 3c). MRI scans showed similar results with the TTC shown (Fig. 3d, e). Normal neurons in cortex and striatum sharply decreased in mice of model group assayed by Nissl staining, and LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 further significantly decreased the number of positive neurons. Although CKLF1 treatment alone could not lead to infarction, mice in CKLF1-Sham group showed significant neuron loss (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

CKLF1 aggravates cerebral ischemia in mice MCAO model. a Workflow of the animal experiment. b Representative images of TTC staining and white area represents the infarct area. c Infarction ratio, edema ratio, and Longa score of mice at 24 h after MCAO or Sham operation (n = 6–12 mice). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus model. d Representative images of MRI and white area circled by dashed line represents the infarct area. e Infarction ratio and edema ratio of mice at 24 h after MCAO or Sham operation (n = 6 mice) ##P < 0.01 versus Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus model. f Photomicrographs of Nissl-stained coronal sections of cortex and striatum. Scale bars 100 µm

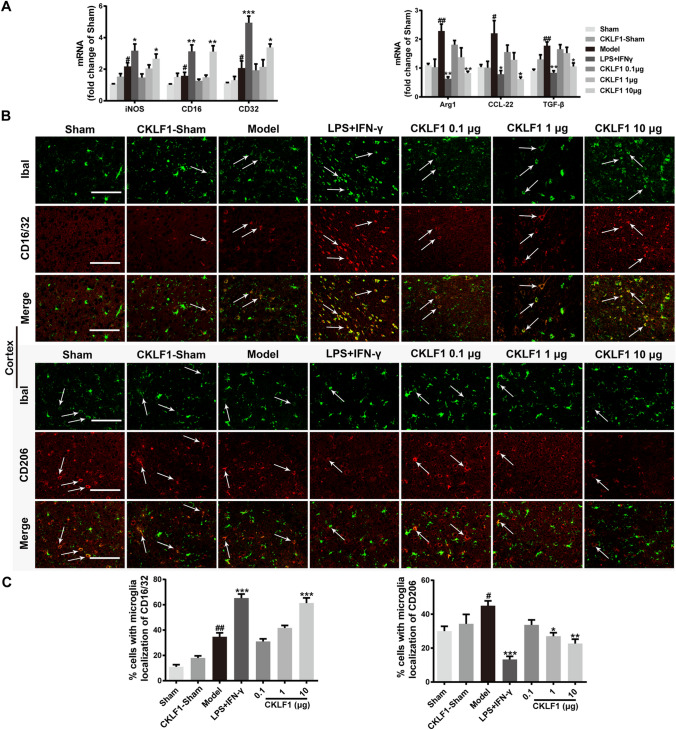

CKLF1 Modulates Microglia/Macrophage Polarize Toward M1 Phenotype in Mice MCAO Model

To examine the effects of CKLF1 on microglia/macrophage polarization, we investigated the mRNA expression of M1 markers iNOS, CD16 and CD32, and M2 markers Arg1, TGF-β and CCL-22 in ischemic hemisphere by qPCR analysis. The mice in model group showed higher expression of both M1 and M2 markers compared with the mice in Sham group. LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 significantly increased the mRNA expression of M1 markers and decreased the mRNA expression of M2 markers in model mice compared with the vehicle-treated model mice (Fig. 4a). The immunofluorescence staining of M1 marker CD16/32 and M2 marker CD206 were also performed to study the polarization effects of CKLF1 in vivo. The results showed that LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 treated model mice showed higher immunofluorescence intensity of CD16/32 and lower immunofluorescence intensity of CD206 in cortex (Fig. 4b, c) and striatum (Fig. 5a, b) compared with model mice treated with vehicle.

Fig. 4.

CKLF1 skews microglia/macrophage polarization toward M1 phenotype in mice MCAO model. a qPCR was performed using total RNA extracted from ischemic hemisphere at 24 h after MCAO and from Sham-operated brains. Expression of mRNA for M1 markers and M2 markers (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus model. b Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the ischemic cortex. Scale bars 100 µm. c Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia/macrophages in the cortex (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus model

Fig. 5.

CKLF1 skews microglia/macrophage polarization toward M1 phenotype in mice MCAO model. a Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the ischemic striatum. Scale bars 100 µm. b Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia/macrophages in the striatum (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05 versus Sham; *P < 0.05 versus model

CKLF1 Deteriorates Inflammatory Response in Mice MCAO Model

Western blot was used to assess levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β and TNF-α, anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). CKLF1-treated Sham-operated mice showed higher IL-1β and TNF-α levels compared with the Sham mice. IL-1β and TNF-α levels in ischemic brain showed significant increase in MCAO-operated mice compared with the Sham-operated mice. LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 both intensified these increase in cytokines in ischemic setting (Fig. 6a). For the TGF-β and BDNF, CKLF1 treatment with and without MCAO operation both increased these cytokine levels compared with Sham animals. LPS plus IFN-γ and CKLF1 suppressed the levels of TGF-β and BDNF in MCAO-operated mice compared with the model mice (Fig. 6b). To determine the involvement of Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway in the CKLF1-mediated microglia/macrophage polarization, expression of p-NF-κB and NF-κB were examined by western blotting. Activated NF-κB pathway was observed in Sham mice given with CKLF1. MCAO operation activated NF-κB pathway, and CKLF1 enhanced this activation (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

CKLF1 deteriorates inflammatory response in mice MCAO model. a Representative blots and densitometry data for IL-1β and TNF-α in the ischemic brain obtained from mice 24 h after MCAO, or from Sham animals (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05 versus Sham; *P < 0.05 versus model. b Representative blots and densitometry data for TGF-β and BDNF (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05 versus model. c Representative blots and densitometry data for NF-κB/p-NF-κB ratio (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus Sham; *P < 0.05 versus model

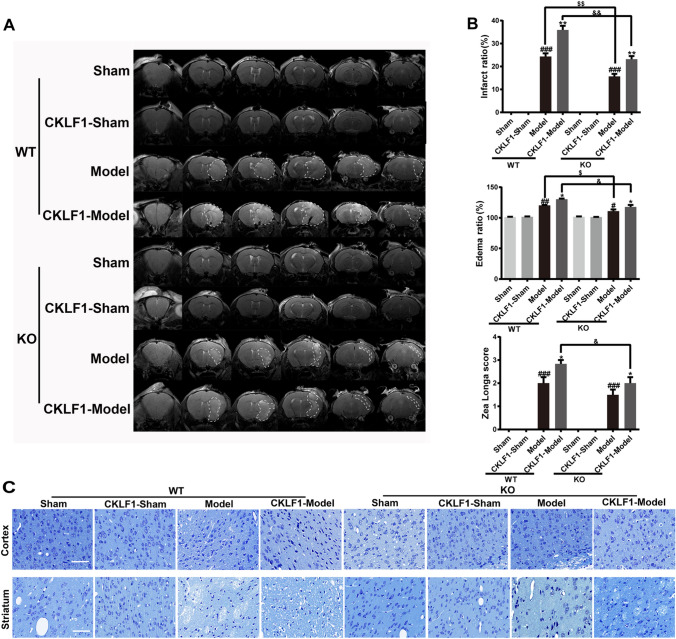

Knock Out of CKLF1 Decreases Brain Damage and M1 Phenotypic Microglia/Macrophage, and Supplement with CKLF1 Aggravates the Injury and Increases the M1 Phenotypic Microglia/Macrophage in Mice MCAO Model

Moreover, CKLF1−/− mice were used to further study the effects of CKLF1 on microglia/macrophage polarization, and treatment with CKLF1 in CKLF1−/− mice mimicked the increase in CKLF1 after cerebral ischemia. MRI scans were performed to determine the cerebral injury, and the outcomes are shown in Fig. 7a. CKLF1−/− mice showed decreased cerebral injury compared with the WT mice. CKLF1−/− mice received with CKLF1 suffered no MCAO showed no brain infarction and behavior abnormalities. After MCAO operation, CKLF1−/− mice received with CKLF1 showed increased infarction volume and edema volume than mice received vehicle and also exhibited more deleterious neurological performance. CKLF1-treated CKLF1−/− mice also showed ameliorated damage and better behavioral performance, compared with the CKLF1 treated WT mice after MCAO operation (Fig. 7b). Nissl staining showed CKLF1−/− mice had more alive neurons in cortex and striatum than WT mice in ischemic setting. Model mice treated with CKLF1 showed decreased number of normal neurons compared with mice treated with vehicle. CKLF1 treated mice with Sham and MCAO operation both showed reduced alive neurons compared with the Sham mice received vehicle (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Knock out of CKLF1 decreases brain damage and supplement with CKLF1 aggravates the injury in mice MCAO model. a Representative images of MRI and white area circled by dashed line represents the infarct area. b Infarction ratio, edema ratio, and Longa score of mice at 24 h after MCAO, or from Sham animals (n = 6–8 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus WT or KO Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus WT or KO model; $P < 0.05, $$P < 0.01 versus WT model; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 versus WT CKLF1-model. c Representative photomicrographs of Nissl-stained coronal sections of cortex and striatum. Scale bars 100 µm

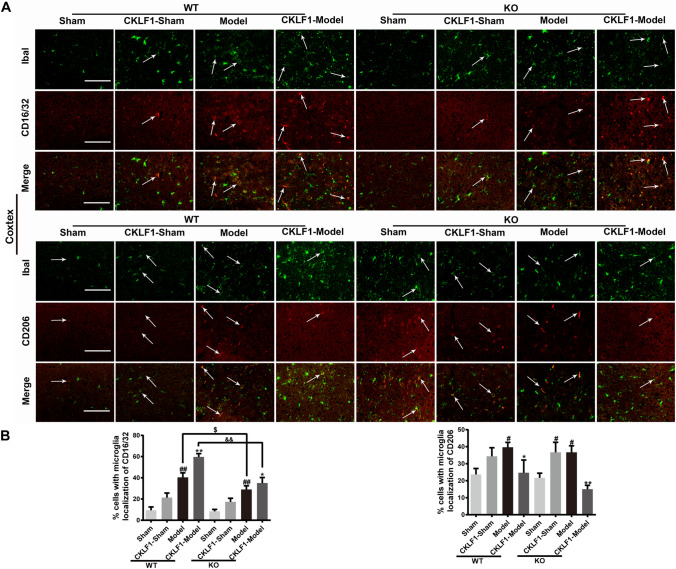

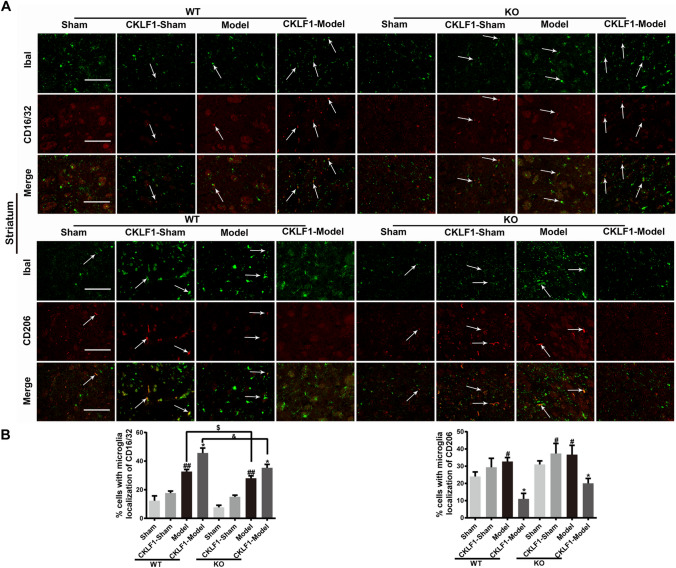

MCAO operation increased the immunofluorescence intensity of M1 and M2 markers in CKLF1−/− mice significantly. CKLF1−/− mice showed fewer M1 phenotypic microglia/macrophage in cortex (Fig. 8a, b) and striatum (Fig. 9a, b) compared with the WT mice subjected to MCAO operation. CKLF1 treated CKLF1−/− mice showed higher expression of M1 marker CD16/32 compare with the vehicle treated CKLF1−/− mice. Moreover, CKLF1-treated WT mice showed higher CD16/32 immunofluorescence intensity in cortex than CKLF1-treated CKLF1−/− mice suffered with MCAO operation (Figs. 8, 9).

Fig. 8.

Knock out of CKLF1 decreases microglia/macrophage M1 phenotype and supplement with CKLF1 increases the M1 phenotype in mice MCAO model. a Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the ischemic cortex. Scale bars 100 µm. b Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia/macrophages in the cortex (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus WT Sham or KO Sham; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus WT or KO model; $P < 0.05 versus WT model; &&P < 0.01 versus WT CKLF1-model

Fig. 9.

Knock out of CKLF1 decreases microglia/macrophage M1 phenotype and supplement with CKLF1 increases the M1 phenotype in mice MCAO model. a Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the ischemic striatum. Scale bars 100 µm. b Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia/macrophages in the striatum (n = 6 mice). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus WT Sham or KO Sham; *P < 0.05 versus WT or KO model; $P < 0.05 versus WT model; &P < 0.05 versus WT CKLF1-model

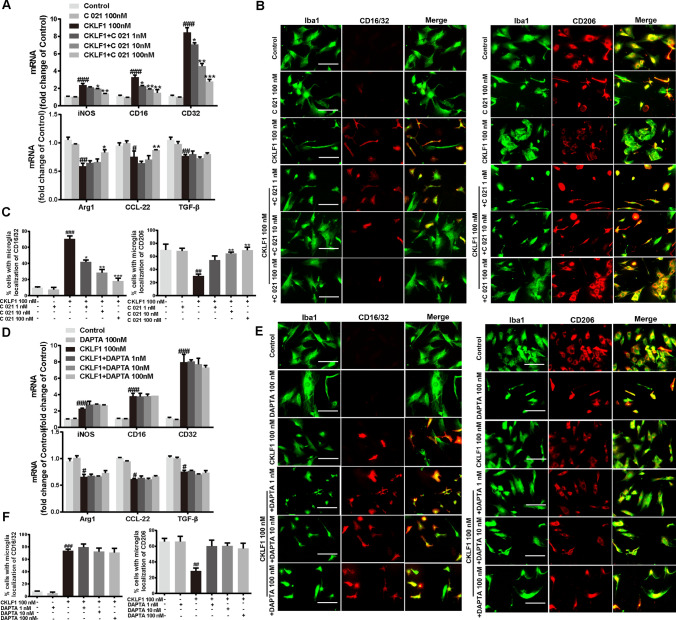

CKLF1 Modulates Microglia Toward M1 Phenotypic Polarization Partly Through CCR4

CCR4 and C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) are two receptors of CKLF1; we speculated that CKLF1 may exert its effects on microglia polarization via these two receptors. To verify this hypothesis, we conducted experiments using C 021 dihydrochloride (CCR4 selective inhibitor) and DAPTA (CCR5 selective inhibitor). CCR4 and CCR5 inhibitors both showed no effects on the mRNA expression of M1 marker iNOS, CD16 and CD32, and M2 markers Arg1, TGF-β and CCL-22 in primary microglia. C 021 dihydrochloride blocked the increased mRNA expression of M1 markers and decreased mRNA expression of M2 markers induced by CKLF1 (Fig. 10a). C 021 dihydrochloride also inhibited the increased immunofluorescence intensity of M1 marker CD16/32 and decreased immunofluorescence intensity of M2 marker CD206 induced by CKLF1 (Fig. 10b, c). However, DAPTA showed no significant suppression function on CKLF1 induced polarization, determined in both qPCR analysis and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 10d–f).

Fig. 10.

CKLF1 modulates the microglia polarization through CCR4. a qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of M1 markers (iNOS, CD16, CD32) and M2 markers (Arg1, CCL-22, TGF-β) in primary microglia treated with CKLF1 and C 021 dihydrochloride for 24 h (n = 6 cell samples). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus CKLF1 100 nM. b Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the primary microglia treated with CKLF1 and C 021 dihydrochloride for 24 h. Scale bars 100 µm. c Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia (n = 6 cell samples). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus CKLF1 100 nM. d qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of M1 markers (iNOS, CD16, CD32) and M2 markers (Arg1, CCL-22, TGF-β) in primary microglia after treatment with CKLF1 and DAPTA for 24 h (n = 6 cell samples). #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus control. e Representative photomicrographs of double-staining immunofluorescence of CD16/32 or CD206 with Iba1 in the primary microglia after treatment with CKLF1 and DAPTA for 24 h. Scale bars 100 µm. f Quantitative analysis of CD16/32-positive and CD206-positive microglia (n = 6 cell samples). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus control

Discussion

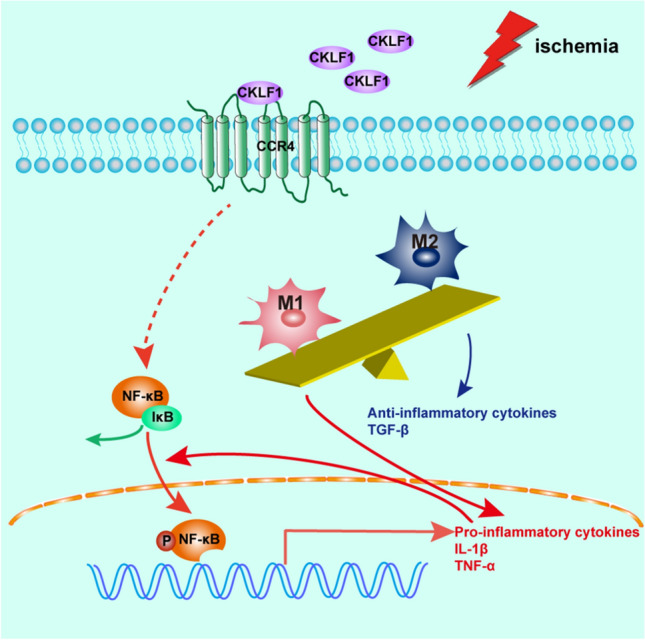

Despite the fact that anti-CKLF1 shows beneficial effects through multiple pathways, the role of CKLF1 in cerebral ischemia remains unclear. The rapid and severe increase in CKLF1 in brain when ischemia occurs suggests that CKLF1 may play an important role in early stage of IS; thus, we focused the effects of CKLF1 on microglia/macrophage polarization at ischemic acute stage. In the present study, we found that CKLF1 modulated primary microglia polarization, driving toward M1 phenotype. In vivo, we demonstrated that increased CKLF1 at acute stage aggravated the cerebral ischemia injury, partly via promoting the microglia/macrophage toward M1 phenotypic polarization and deteriorating subsequent inflammatory response (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

CKLF1 modulates microglia/macrophage polarize toward M1 phenotype and aggravates cerebral ischemia injury at early stage. When cerebral ischemia occurs, expression of CKLF1 in ischemic brain increases rapidly and sharply. The excessive CKLF1 bind with CCR4 and modulates microglia/macrophage polarize toward M1 phenotype. NF-κB pathway may be involved in this progress and subsequent promote transcription and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α. The released pro-inflammatory cytokines further activates the NF-κB and forms a vicious circle. The microglia/macrophage with M1 phenotype dominants than M2 phenotype which release the TGF-β with anti-inflammatory functions, and the imbalance between microglia/macrophage with M1 and M2 phenotype leads to deteriorated inflammatory response and injury expansion

Previous studies have shown that selective inhibition of CKLF1 activity exert protective effects on rats suffered with cerebral ischemia, suggesting CKLF1 may play detrimental role in cerebral ischemia. In this study, we supplied CKLF1 in WT mice to investigate the effect of CKLF1 on microglia/macrophage polarization and cerebral ischemic injury. At 24 h, endogenous CKLF1 had not reached its peak, which at about 48 h according to our finding in this paper, and was in the ascending process; thus, CKLF1 administration mimicked the later higher CKLF1 expression. CKLF1−/− mice have no endogenous CKLF1, and CKLF1 supplement mimics the CKLF1 increase in ischemic setting, which can be used to examine the role of CKLF1 and endogenous CKLF1 in short-term neurobehavioral and neuropathological outcomes after focal cerebral ischemia. In the presence of endogenous CKLF1, supplement with CKLF1 promotes M1 phenotypic polarization and aggravates ischemic injury; in the absence of endogenous CKLF1, supplement with CKLF1 also promotes M1 phenotypic polarization and aggravates ischemic injury. It is worth noting that CKLF1−/− mice show slighter cerebral ischemic injury compared with WT mice, and M1 phenotypic polarization is also less. The results of two in vivo experiments indicate that the increase in CKLF1 in early cerebral ischemia plays an important role in promoting M1 phenotypic polarization, leading to the early damage of cerebral ischemia partly.

Microglia/macrophages are the primary mediators of the brain’s innate immune response to injury and disease (Hu et al. 2012; Loane and Byrnes 2010). These primary immune cells of the CNS act not only as the major inflammatory cell type in the brain, but also as very important roles in maintaining the homeostatic environment. Recent research on the functions of microglia in the injured CNS provides strong evidence to support their phenotypic activation into M1 or M2 subtypes and their dual roles—both beneficial and harmful. As the microenvironment changes, microglia/macrophages migrate to the site of injury and initiate the secretion of effector molecules rapidly, drastically altering their phenotypes and function. A large number of studies indicate that M1 polarized microglia contribute to neuronal dysfunction and cell death by releasing pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, reactive oxygen species and MMPs (Espinosa-Garcia et al. 2017; Woo et al. 2008; Won et al. 2015). However, M2 polarized microglial activation exerts beneficial effects in the injured brain through removing cellular debris and help to restore tissue regeneration (Pan et al. 2015; Lalancette-Hebert et al. 2007). Although both phenotypes of microglia exist during IS, the vulnerable brain environment favors M1 microglia, leading to damage expansion and neurologic deficits (Xia et al. 2015; Hu et al. 2012). In contrast, the M2 phenotype shows inferior with the development of IS. Thus, modulating microglia/macrophage polarization may be a therapeutic target for stroke therapy. We observed an increase in both M1 and M2 microglia/macrophage in mice subjected to MCAO operation at 24 h, which is in line with previous work in which microglia are activated and polarized to both phenotype at early stage of cerebral ischemia (Hu et al. 2012). Moreover, CKLF1-treated mice suffered MCAO showed more microglia/macrophage with M1 phenotype in both WT and CKLF1−/− mice. CKLF1−/−mice also showed fewer M1 polarized microglia/macrophage compared with the WT mice in similar ischemic setting. To us, it seems increasingly apparent that CKLF1 heightens the M1 microglia/macrophage reaction after stroke. These results demonstrated that both exogenous CKLF1 and endogenous CKLF1 modulated the microglia/macrophage polarization toward M1 at ischemic acute stage.

It is well known that microglia/macrophage polarization and the subsequent neuroinflammatory responses contribute to secondary brain injury after stroke. M1 phenotypic microglia/macrophage polarization is involved in the initiation and perpetuation of neuroinflammation in other diseases as well as stroke, whereas M2 polarized microglia/macrophage is more related to the resolution of neuroinflammation through engulfment and degradation of invading pathogens, peptides and apoptotic cells. The proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α in ischemic brain were increased significantly with MCAO insult, and CKLF1 increased release of these proinflammatory mediators. TGF-β is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, and BDNF is a factor can protect damage neuron from death, improve the pathological morphology of neuron, and help to restore neurogenesis. CKLF1 decreased the expression of TGF-β and BDNF in mice MCAO model, which is detrimental for aggravating the excessive inflammatory response and inhibiting recovery. NF-κB is considered the central transcription factor of inflammatory mediators, which plays a crucial role in microglial activation (Lawrence 2009; Shih et al. 2015). Numerous studies show that cerebral ischemia result in NF-κB activation (Clemens et al. 1997; Venna et al. 2012). Our finding is consistent with the former studies that ischemia leads to NF-κB activation. In addition, we further found that CKLF1-induced NF-κB activation at physiological state or enhance NF-κB activation in ischemic episode, which suggested that CKLF1 may drive microglia/macrophage toward M1 phenotype through NF-κB pathway.

In the present study, CKLF1 increased the M1 markers and decreased M2 markers in primary microglia. However, CKLF1 showed different effects on microglia/macrophage polarization in in vivo study. In mice received with CKLF1 and without MCAO operation, the M1 and M2 markers both showed significant increase. Interestingly, when CKLF1 treated mice suffered the MCAO operation, despite WT or CKLF1−/− mice, CKLF1 seemed to enhance the expression of M1 markers but decrease the expression of M2 markers. This discordant effects of CKLF1 may due to the microenvironment in which microglia are located. The in vitro environment of microglia is relatively simple compared with the in vivo condition. In Sham-operated mice, the microenvironment of brain is stable and powerful to restore to the homeostasis when insulted by mild stress. CKLF1 stimulation is slight compared with MCAO operation, and effects of CKLF1 stimulation may compensate by other factors with strong regulatory capacity. In ischemic setting, the brain suffers severe damage and the microenvironment homeostasis is totally disturbed. Another reason may be the pure primary microglia was used in vitro study, but in the mice, the population of microglia and macrophage was determined. The migrated macrophage may showed different property of polarization with the resident microglia. For CKLF1 may play important role poststroke, it dominates the initiation and progression of cerebral ischemia at early stage, and its M1 polarized effects may amplified in this condition.

It is reported that CCR5 is closely related to IS, although with some contradictory outcomes (Sorce et al. 2010; Li et al. 2016, 2017; Victoria et al. 2017). Sorce et al. reported that mice lacking the chemokine receptor CCR5 showed increased brain damage after permanent IS (Sorce et al. 2010). However, later study found knockdown of CCR5 is protective against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury (Victoria et al. 2017). Since complex participation of cellular and humoral inflammations in ischemic brain injury, the neuroinflammation may various in different experimental models (Zhou et al. 2013), and these different outcomes may due to the different stroke model. In the present study, we found CKLF1 modulates microglia/macrophage polarization through the CCR4. There is no study suggests the function of CCR4 in cerebral ischemia yet. This finding may indicate us that CCR4 is also involved in IS, and further studies are needed to clarify its role in cerebral ischemia.

Despite in clinical investigations or basic animal studies, female showed significant difference in incidence, mortality and morbidity of stroke compared with male (Chauhan et al. 2017; Zuo et al. 2013). In the present study, we used only male subjects to minimize confounding variables such as hormonal cycling and estropause for this first series of experiments. We are very aware of potential sex differences in stroke outcome (Gibson 2013) and in immune responses (Bekhbat and Neigh 2018; Klein and Flanagan 2016). Our future research will enroll sex as a biological variable to clarify CKLF1 functions in IS.

In addition, this study only focused the role of CKLF1 at acute stage about 24 h after reperfusion, what is the role of CKLF1 in a later stage needed further research. Studies have shown cerebral ischemia is associated with marked induction of chemokine which leading to extensive leukocyte infiltration to the ischemic brain, and worsening cerebral damage (Mirabelli-Badenier et al. 2011; Frangogiannis 2007). However, chemokine also show other functions such as promote neuroblast migration (Yan et al. 2007), neovascularization (Mao et al. 2014) and functional brain repair (Mori et al. 2015). Thus, CKLF1 may mediate both beneficial and detrimental effects depending on pathophysiological conditions. Exploring whether CKLF1 play detrimental role in restorative phase, or exert beneficial effects through other mechanisms is of our great interest and future study aim.

Conclusions

In the present study, we demonstrated that CKLF1 modulates microglia/macrophage toward M1 polarization and aggravates injury expansion at ischemic early stage in mice MCAO model. These findings are supported by data obtained from primary microglia in vitro. Our results confirm and extend findings that CKLF1 worsens the inflammatory response to ischemia/reperfusion by priming microglia and exacerbating their activation, but also by inducing phenotypic and functional changes. We further find that this polarization-associated effects is partly dependent on the CCR4, which may be involved with the activation of NF-κB pathway, giving us more indications for the role of CKLF1 in cerebral ischemia. These data may have implications for CKLF1 as a potential therapeutic intervention targeting the modulation of microglial/macrophage phenotypes and the inflammatory response following ischemic injury.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730093, 81730096, 81873026, U1402221); the National Mega-project for Innovative Drugs (2018ZX09711001-002-007, 2018ZX09711001-003-005, 2018ZX09711001-009-013); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2016-I2M-1-004); Beijing Key Laboratory of New Drug Mechanisms and Pharmacological Evaluation Study (BZ0150); The State Key Laboratory Fund Open Project (GTZK201610); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2013M540066); Project of NDRC and State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (60011000); Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory for Standardization of Important Chinese Herbal Pieces (BG201701, 4981-0901020).

Author Contributions

Chen Chen, Shi-feng Chu, Zhao Zhang, Nai-hong Chen conceptualized and designed the study; Chen Chen, Qi-di Ai, Fei-Fei Guan, Sha-Sha Wang, Yi-Xiao Dong, Jie-Zhu, Nai-hong Chen acquired and analyzed the data; Chen Chen, Qi-di Ai, Wen-Xuan Jian, Nai-hong Chen drafted the text and prepared the figures. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: in Figure 10B the merge image of C021 100 nM group of microglia stained with CD206 has been corrected.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/10/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s10571-024-01480-7

References

- Bekhbat M, Neigh GN (2018) Sex differences in the neuro-immune consequences of stress: focus on depression and anxiety. Brain Behav Immun 67:1–12. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Moser H, McCullough LD (2017) Sex differences in ischaemic stroke: potential cellular mechanisms. Clin Sci 131(7):533–552. 10.1042/CS20160841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li Z, Hatcher JT, Chen QH, Chen L, Wurster RD, Chan SL, Cheng Z (2017) Deletion of TRPC6 attenuates NMDA receptor-mediated Ca(2+) entry and Ca(2+)-induced neurotoxicity following cerebral ischemia and oxygen-glucose deprivation. Front Neurosci 11:138. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens JA, Stephenson DT, Dixon EP, Smalstig EB, Mincy RE, Rash KS, Little SP (1997) Global cerebral ischemia activates nuclear factor-kappa B prior to evidence of DNA fragmentation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 48(2):187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Wolf SL, Adams HP Jr, Chen D, Dromerick AW, Dunning K, Ellerbe C, Grande A, Janis S, Lansberg MG, Lazar RM, Palesch YY, Richards L, Roth E, Savitz SI, Wechsler LR, Wintermark M, Broderick JP (2017) Stroke recovery and rehabilitation research: issues, opportunities, and the National Institutes of Health StrokeNet. Stroke J Cereb Circ 48(3):813–819. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Kroner A (2011) Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 12(7):388–399. 10.1038/nrn3053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Garcia C, Sayeed I, Yousuf S, Atif F, Sergeeva EG, Neigh GN, Stein DG (2017) Stress primes microglial polarization after global ischemia: therapeutic potential of progesterone. Brain Behav Immun 66:177–192. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis NG (2007) Chemokines in ischemia and reperfusion. Thrombosis Haemostasis 97(5):738–747 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL (2013) Cerebral ischemic stroke: is gender important? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(9):1355–1361. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Lou Y, Tang J, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Gu W, Huang J, Gui L, Tang Y, Li F, Song Q, Di C, Wang L, Shi Q, Sun R, Xia D, Rui M, Tang J, Ma D (2001) Molecular cloning and characterization of chemokine-like factor 1 (CKLF1), a novel human cytokine with unique structure and potential chemotactic activity. Biochem J 357(Pt 1):127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S, Gao Y, Chen J (2012) Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke J Cereb Circ 43(11):3063–3070. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Cheng G, Tan H, Qin R, Zou Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y (2017) Capsaicin protects cortical neurons against ischemia/reperfusion injury via down-regulating NMDA receptors. Exp Neurol 295:66–76. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Liu L, Zhang S, Nanda A, Li G (2013) Role of inflammation and its mediators in acute ischemic stroke. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 6(5):834–851. 10.1007/s12265-013-9508-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Cheng J, Liu Y, Wu J, Wang X, Wei S, Zhou X, Qin Z, Jia J, Zhen X (2014) Improvement of functional recovery by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced alternative activation of microglia/macrophages and increased angiogenesis and neurogenesis following experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun 40:131–142. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Flanagan KL (2016) Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 16(10):626–638. 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong LL, Hu JF, Zhang W, Yuan YH, Ma KL, Han N, Chen NH (2011) Expression of chemokine-like factor 1 after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neurosci Lett 505(1):14–18. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong LL, Hu JF, Zhang W, Yuan YH, Han N, Chen NH (2012) C19, a C-terminal peptide of chemokine-like factor 1, protects the brain against focal brain ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett 508(1):13–16. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong LL, Wang ZY, Han N, Zhuang XM, Wang ZZ, Li H, Chen NH (2014) Neutralization of chemokine-like factor 1, a novel C-C chemokine, protects against focal cerebral ischemia by inhibiting neutrophil infiltration via MAPK pathways in rats. J Neuroinflamm 11:112. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalancette-Hebert M, Gowing G, Simard A, Weng YC, Kriz J (2007) Selective ablation of proliferating microglial cells exacerbates ischemic injury in the brain. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 27(10):2596–2605. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5360-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Yang QW, Wang J (2017) Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol 13(7):420–433. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T (2009) The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb perspect Biol 1(6):a001651. 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhi D, Shen Y, Liu K, Li H, Chen J (2016) Effects of CC-chemokine receptor 5 on ROCK2 and P-MLC2 expression after focal cerebral ischaemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Brain Injury 30(4):468–473. 10.3109/02699052.2015.1129557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Wang L, Zhou Y, Gan Y, Zhu W, Xia Y, Jiang X, Watkins S, Vazquez A, Thomson AW, Chen J, Yu W, Hu X (2017) C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5)-mediated docking of transferred Tregs protects against early blood–brain barrier disruption after stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 6 (8). 10.1161/jaha.117.006387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loane DJ, Byrnes KR (2010) Role of microglia in neurotrauma. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother 7(4):366–377. 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Yang GY (2017) The biphasic function of microglia in ischemic stroke. Prog Neurobiol 157:247–272. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Huang M, Chen SC, Li YN, Xia YP, He QW, Wang MD, Huang Y, Zheng L, Hu B (2014) Endogenous endothelial progenitor cells participate in neovascularization via CXCR4/SDF-1 axis and improve outcome after stroke. CNS Neurosci Ther 20(5):460–468. 10.1111/cns.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabelli-Badenier M, Braunersreuther V, Viviani GL, Dallegri F, Quercioli A, Veneselli E, Mach F, Montecucco F (2011) CC and CXC chemokines are pivotal mediators of cerebral injury in ischaemic stroke. Thrombosis Haemostasis 105(3):409–420. 10.1160/TH10-10-0662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Matsubara K, Matsubara Y, Uchikura Y, Hashimoto H, Fujioka T, Matsumoto T (2015) Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a crucial role based on neuroprotective role in neonatal brain injury in rats. Int J Mol Sci 16(8):18018–18032. 10.3390/ijms160818018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, Mantovani A, Martinez FO, Mege JL, Mosser DM, Natoli G, Saeij JP, Schultze JL, Shirey KA, Sica A, Suttles J, Udalova I, van Ginderachter JA, Vogel SN, Wynn TA (2014) Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41(1):14–20. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash KM, Schiefer IT, Shah ZA (2018) Development of a reactive oxygen species-sensitive nitric oxide synthase inhibitor for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Free Radic Biol Med 115:395–404. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Jin JL, Ge HM, Yin KL, Chen X, Han LJ, Chen Y, Qian L, Li XX, Xu Y (2015) Malibatol A regulates microglia M1/M2 polarization in experimental stroke in a PPARgamma-dependent manner. J Neuroinflamm 12:51. 10.1186/s12974-015-0270-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa R, Lund H, Tosevski I, Zhang XM, Malipiero U, Beckervordersandforth J, Merkler D, Prinz M, Gyllenberg A, James T, Warnecke A, Hillert J, Alfredsson L, Kockum I, Olsson T, Fontana A, Suter T, Harris RA (2016) TGFbeta regulates persistent neuroinflammation by controlling Th1 polarization and ROS production via monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Glia 64(11):1925–1937. 10.1002/glia.23033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Deng T, Zhang T, Li P, Wang Y (2015) FAM19A3, a novel secreted protein, modulates the microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics and ameliorates cerebral ischemia. FEBS Lett 589(4):467–475. 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih RH, Wang CY, Yang CM (2015) NF-kappaB signaling pathways in neurological inflammation: a mini review. Front Mol Neurosci 8:77. 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S, Bonnefont J, Julien S, Marq-Lin N, Rodriguez I, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH (2010) Increased brain damage after ischaemic stroke in mice lacking the chemokine receptor CCR5. Br J Pharmacol 160(2):311–321. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00697.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venna VR, Weston G, Benashski SE, Tarabishy S, Liu F, Li J, Conti LH, McCullough LD (2012) NF-kappaB contributes to the detrimental effects of social isolation after experimental stroke. Acta neuropathol 124(3):425–438. 10.1007/s00401-012-0990-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victoria ECG, de Brito Toscano EC, de Sousa Cardoso AC, da Silva DG, de Miranda AS, da Silva Barcelos L, Sugimoto MA, Sousa LP, de Assis Lima IV, de Oliveira ACP, Brant F, Machado FS, Teixeira MM, Teixeira AL, Rachid MA (2017) Knockdown of C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) is protective against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. Curr Neurovasc Res 14(2):125–131. 10.2174/1567202614666170313113056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhao H, Zhai ZZ, Qu LX (2018) Protective effect and mechanism of ginsenoside Rg1 in cerebral ischaemia–reperfusion injury in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 99:876–882. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won S, Lee JK, Stein DG (2015) Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator promotes, and progesterone attenuates, microglia/macrophage M1 polarization and recruitment of microglia after MCAO stroke in rats. Brain Behav Immun 49:267–279. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo MS, Park JS, Choi IY, Kim WK, Kim HS (2008) Inhibition of MMP-3 or -9 suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines and iNOS in microglia. J Neurochem 106(2):770–780. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia CY, Zhang S, Gao Y, Wang ZZ, Chen NH (2015) Selective modulation of microglia polarization to M2 phenotype for stroke treatment. Int Immunopharmacol 25(2):377–382. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, Park SW, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ (2007) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27(6):1213–1224. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Liesz A, Bauer H, Sommer C, Lahrmann B, Valous N, Grabe N, Veltkamp R (2013) Postischemic brain infiltration of leukocyte subpopulations differs among murine permanent and transient focal cerebral ischemia models. Brain Pathol 23(1):34–44. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00614.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo W, Zhang W, Chen NH (2013) Sexual dimorphism in cerebral ischemia injury. Eur J Pharmacol 711(1–3):73–79. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo W, Yang PF, Chen J, Zhang Z, Chen NH (2016) Drp-1, a potential therapeutic target for brain ischaemic stroke. Br J Pharmacol 173(10):1665–1677. 10.1111/bph.13468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]