Abstract

Background

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by total mesorectal excision is a standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer. Mismatch repair-deficient locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) was highly sensitive to PD-1 blockade. However, most rectal cancers are microsatellite stable (MSS) or mismatch repair-proficient (pMMR) subtypes for which PD-1 blockade is ineffective. Radiation can trigger the activation of CD8 + T cells, further enhancing the responses of MSS/pMMR rectal cancer to PD-1 blockade. Radioimmunotherapy offers a promising therapeutic modality for rectal cancer. Progenitor T exhausted cells are abundant in tumour-draining lymph nodes and play an important role in immunotherapy. Conventional irradiation fields include the mesorectum and regional lymph nodes, which might cause considerable damage to T lymphocytes and radiation-induced fibrosis, ultimately leading to a poor response to immunotherapy and rectal fibrosis. This study investigated whether node-sparing modified short-course irradiation combined with chemotherapy and PD-1 blockade could be effective in patients with MSS/ pMMR LARC.

Methods

This was a open-label, single-arm, multicentre, prospective phase II trial. 32 LARC patients with MSS/pMMR will receive node-sparing modified short-course radiotherapy (the irradiated planned target volume only included the primary tumour bed but not the tumour-draining lymph nodes, 25 Gy/5f, 5 Gy/f) followed by CAPOX and tislelizumab. CAPOX and tislelizumab will be started two days after the completion of radiotherapy: oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 intravenous infusion, day 1; capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 oral administration, days 1–14; and tislelizumab 200 mg, intravenous infusion, day 1. There will be four 21-day cycles. TME will be performed at weeks 14–15. We will collect blood, tumour, and lymphoid specimens; perform flow cytometry and in situ multiplexed immunofluorescence detection; and analyse the changes in various lymphocyte subsets. The primary endpoint is the rate of pathological complete response. The organ preservation rate, tumour regression grade, local recurrence rate, disease-free survival, overall survival, adverse effects, and quality of life will also be analysed.

Discussion

In our research, node-sparing modified radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy probably increased the responsiveness of immunotherapy for MSS/pMMR rectal cancer patients, reduced the occurrence of postoperative rectal fibrosis, and improved survival and quality of life. This is the first clinical trial to utilize a node-sparing radiation strategy combined with chemotherapy and PD-1 blockade in the neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer, which may result in a breakthrough in the treatment of MSS/pMMR rectal cancer.

Trial registration

This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov. Trial registration number: NCT05972655. Date of registration: 31 July 2023.

Keywords: Microsatellite stability, Locally advanced rectal cancer, Nodes-sparing, Short-course radiotherapy, Chemotherapy, Tislelizumab, Total mesorectal excision, Pathological complete response

Background

The standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) includes neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) combined with total mesorectal excision (TME) [1]. For patients with low LARC, the anus needs to be resected, which leads to great physical and psychological trauma for the patients [2]. Although some patients can undergo anus preservation surgery after nCRT, a series of postresection syndromes, such as radiation-induced fibrosis, frequent defecation, and defecation incontinence or difficulty, affect the quality of life (QoL) of patients [3].

Some LARC patients can achieve a clinical complete response (cCR) after receiving nCRT and then adopt a watch-and-wait strategy, which can lead to a long-term prognosis similar to TME. However, traditional nCRT has a low complete response (CR) rate. Therefore, the improvement of the nCRT strategy for rectal cancer is important for improving the CR rate and the organ preservation rate of rectal cancer patients.

As an immunosuppressive pathway, immune checkpoints can inhibit antitumour immunity and promote tumorigenesis [4]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can restore immune function by blocking specific protein ligands of T cells [5]. Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1 are currently the most widely used ICIs [4, 5]. Recently, Cercek and colleagues published the results of anti-PD1 immunotherapy in mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) LARC. One single agent of dostarlimab achieved a 100% cCR rate, exempting subsequent CRT and surgery, and no patients had progression or recurrence during follow-up [6]. However, for rectal cancers, 95% are microsatellite stability (MSS) or mismatch repair-proficient (pMMR) types, which cannot benefit from ICIs alone [7]. Studies have shown that radiotherapy can lead to the death of tumour immunogenic cells, release new tumour-associated antigens, and increase the infiltration of T lymphocytes, thus producing a synergistic effect with ICIs [8]. Clinical trials have studied the application of nCRT and ICIs in MSS/pMMR LARC, which increases the probability of pathological complete response (pCR) [9, 10]. For instance, in the VOLTAGE trial, 30% of MSS/pMMR LARC patients reached pCR after receiving nCRT followed by nivolumab [9].

Tumour draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) are the classical sites for T-cell priming and activation [11, 12]. Blocking the egress of lymphocytes from lymph organs using a specific blocking agent abrogates ICI efficacy [13]. Progenitor or precursor exhausted T cells (Tpex) are a subset of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with high proliferative capacity expressing transcription factor-1 and are abundant in TDLNs [14]. A study of human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas revealed that Tpex cells can differentiate into intermediate-exhausted CD8+ T cells after ICI treatment, driving an increase in terminally exhausted T cells (Tex) in the tumour microenvironment [14]. This phenomenon can also be seen in mouse models [15]. Hence, TDLNs are the primary site where Tpex is activated and plays an important role in the response to ICI therapy.

The standard short/long-course radiotherapy target volume includes the rectal tumour and TDLNs, which will deplete the critical immune cells in the rectal tumour and TDLNs, reducing the effectiveness of immunotherapy [16]. In addition, one severe complication of conventional wide-field irradiation is radiation-induced fibrosis (RIF) [17]. RIF will aggravate rectal stenosis and loss of tissue compliance, which significantly affects the overall quality of life in rectal cancer patients. Therefore, the exclusion of TDLNs from the radiotherapy target volume would increase the efficacy of radioimmunotherapy and reduce the incidence of RIF.

In summary, previous research indicates the promising benefit of radioimmunotherapy and the importance of TDLNs in immunotherapy. We are conducting node-sparing short-course radiotherapy plus CAPOX and tislelizumab for neoadjuvant therapy in MSS/pMMR LARC patients to assess the safety and efficacy.

Methods and study design

Study design

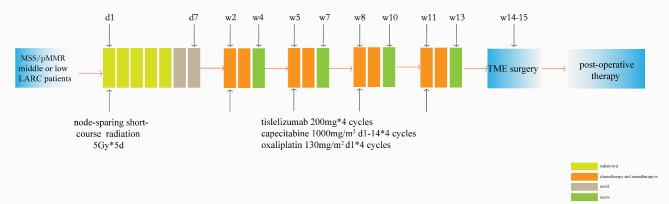

The study is an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, prospective phase II trial. MSS/pMMR LARC Patients will receive node-sparing modified short-course radiotherapy (25 Gy/5f). The irradiated planned target volume will only include the primary tumour bed but not the tumour-draining lymph nodes, followed by 3 cycles of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) chemotherapy and tislelizumab. Then, patients will undergo TME. The pCR rate, adverse effects, and long-term prognosis will be analysed. The study flow chart is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The trial flow chart. LARC: Locally advanced rectal cancer; MSS: Microsatellite stability; TME: Total mesorectal excision

Trial organization, ethics approval, drug supply and insurance

The trial was initiated by the Colorectal Department of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Thirty-two patients with localized RC will be enrolled in two centres. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval number: 2023 − 0386). All enrolled patients will sign informed consent forms. Tislelizumab has been obtained free of charge by Beijing BeiGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd., which has purchased liability insurance for the subjects.

Study population

LARC patients who meet the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria (Table 1) will be included in this clinical trial. Only MSS/pMMR patients can be included in our study. The trial was opened on 31 July 2023. The first patient was recruited on 21 August 2023.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1. Patients who have a strong willingness to preserve the anus and are willing to receive neoadjuvant therapy. |

| 2. Male or female aged 18–75 years. |

| 3. Patients diagnosed with low rectal cancer within 10 cm from the lower edge of the tumour to the anal verge by pelvic MRI and anorectoscopy, the clinical stage is cT2N + M0/cT3-4bN0/+M0, the lymph nodes are limited to the mesorectum. |

| 4. Histologically confirmed rectal adenocarcinoma; genetic testing suggests MSI-L or MSS, or tumour biopsy immunohistochemistry reveals pMMR, that is, MSH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 are all positive. |

| 5. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 0 or 1. |

| 6. No previous treatment (including antitumour therapy、immunotherapy or pelvic radiation). |

| 7. Adequate haematologic, hepatic, renal, thyroid and cardiac function: white blood cells ≥ 3500/mm3, neutrophils ≥ 1800/mm3, platelets ≥ 100,000/mm3, haemoglobin ≥ 100 g/L; activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time and international normalized ratio ≤ 1.5 × ULN; aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase ≤ 3.0 × upper limit of normal (ULN), bilirubin ≤ 1.25 × ULN, serum albumin ≥ 28 g/L, creatinine clearance ≥ 50 mL/mi, creatinine ≤ 1.5 × ULN. |

| 8. Informed consent form signed. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1. Patients with a previous history of malignant tumours besides rectal cancer. |

| 2. Patients with distant metastases before enrolment. |

| 3. Patients with positive internal or external iliac lymph nodes are assessed by MRI or CT. |

| 4. Patients with obstruction, perforation, or bleeding that require emergency surgery. |

| 5. Patients with severe concomitant diseases and estimated survival time ≤ 5 years. |

| 6. Allergic to any component of the therapy. |

| 7. Patients with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, or mucinous adenocarcinoma. |

| 8. Patients who received immunosuppressive or systemic hormone therapy for immunosuppressive purposes within 1 month prior to the initiation of therapy. |

| 9. Patients who have received any other experimental drug (including immunotherapy) or participated in another interventional clinical trial within 30 days before screening. |

| 10. Factors leading to study termination, such as alcoholism, drug abuse, other serious illnesses (including psychiatric disorders) requiring combination therapy, and patients with severe laboratory abnormalities. |

| 11. Patients with congenital or acquired immune deficiency (such as HIV infection). |

| 12. Vulnerable groups, including mentally ill, cognitively impaired, critically ill patients, minors, pregnant or lactating women, illiterate, etc. |

| 13. Other conditions that investigators consider not suitable for this study. |

Therapeutic schedule

The enrolled patients will receive node-sparing modified short-course radiotherapy combined with CAPOX and tislelizumab, and then, they will undergo TME. The detailed process is as follows:

① Node-sparing modified short-course radiotherapy (25 Gy/5 f, 5 Gy/f, 5 days) in the first week using three-dimensional conformal or intensity-modulated radiotherapy technology. The irradiation field was limited to the tumour bed, and the TDLNs were not irradiated.

② On the 8th day after the start of radiotherapy, the enrolled patients will be treated with four cycles of CAPOX (capecitabine,1000 mg/m2, bid, po, days 1–14; oxaliplatin, 130 mg/m2, ivgtt, day 1) combined with a PD-1 inhibitor (tislelizumab 200 mg, ivgtt, day 1) every 3 weeks.

③ TME will be performed at least one week after the end of chemotherapy.

Data collection, management and outcomes analysis

Data will be recorded on a case report form. All forms must be completed, signed, and dated by the person completing them. The research director will check the database monthly and urge each centre to complete the data registration. The clinical data collection will be completed by colorectal surgeons. If there are any missing data, the reasons must be stated.

The primary endpoint is the pCR rate. All enrolled patients will receive TME surgery 1–2 weeks after the end of chemotherapy. Two independently experienced pathologists will evaluate the resected rectal specimens according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging as soon as the TME surgery is completed. The secondary endpoints include the organ preservation rate, tumour regression grade (TRG), 3-year local recurrence rate (LRR), 3-year disease-free survival (DFS), 3-year overall survival (OS), adverse effects rate, and QoL scores.

Sample size

As reported, the pCR rate of short-course chemoradiotherapy with surgery is approximately 10% [18]. The estimated pCR rate of our trial was 30% [19]. The sample size was calculated using PASS software (V.15). Using α = 0.05 and β = 0.2, the sample size should be 29 patients. Assuming a maximum dropout rate of 10%, the final sample size will be 32 patients.

Adverse events

Adeverse event variables included hematological toxicity (anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, et al.), neurological toxicity (headache, dizziness, seizures, neuropathy, altered mental status), gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, et al.), hepatic toxicity (elevated liver enzymes, hyperbilirubinemia, hepatitis, et al.), renal toxicity (elevated creatinine, decreased glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, et al.), cardiac toxicity (arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, heart failure, et al.) and other toxicities (fatigue, fever, vomiting, nausea, rash, constipation, pruritus, hyperthyroidism, et al.). Adverse events management for our study will follow the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) 4.0. The incidence and management of adverse events and detailed reasons for suspension/permanent discontinuation will be recorded.

Follow-up

Follow-up will be completed by experienced professional follow-up personnel. Patients will be followed up every 3 months in the first year postoperatively and every 6 months in the next two years. Follow-up included digital rectal examination, complete blood count, blood biochemical examination, and serum tumour markers (CEA, CA199, AFP) every 3 months for the first 2 years, and then every 6-12months thereafter. Imaging examinations (pelvic MRI, abdominal CT, and chest CT) will be performed at baseline, before surgery, every 3–6 months after the surgery for the first 2 years, and then every 6–12 months thereafter, two independent radiologists will read and evaluate the imaging data of enrolled patients. Colonoscopy, quality of life assessment (EORTC QLQ-CR29/C30), and Wexner score will be performed every 6 months. The dates and locations of local recurrence, distant metastasis, and date and cause of death will be recorded in detail.

Statistical analysis

The computer (R language or Prism 7.0) software package will be used to carry out the statistical analysis. Continuous variables are represented by the means ± standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals and will be analysed by unpaired t tests. Categorical variables are represented by numbers and percentages and will be analysed by the chi-square test. The Kaplan‒Meier and LogRank methods will be used to analyse survival, and the Cox proportional hazards model will be used for prognostic analysis. p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences.

Discussion

nCRT increases the probability of pCR in LARC patients; however, the pCR rate is lower than 20% [20, 21]. Most LARC patients treated with nCRT will suffer RIF [17] and rectal stenosis after TME, which will have a considerable impact on QoL. Therefore, a better strategy is needed to improve the CR rate and reduce the probability of postoperative complications.

Studies have shown that irradiation can lead to the death of tumour immunogenic cells, release new tumour-associated antigens, promote the antigen presentation function of dendritic cells (DCs), and increase the infiltration of T lymphocytes, thereby changing MSS-type rectal cancer from a “cold tumour” to a “hot tumour” [22]. Seo [23] suggested that radiotherapy could induce apoptosis in three colon cancer cells and downregulate various MMR-related genes. Irradiation significantly increased the tumour mutation burden (TMB) in LARC tissues, thereby increasing the recruitment of M2 macrophages and CD8+ T cells into the tumour microenvironment; these findings suggest that nCRT may enhance MSS LARC responsiveness to immunotherapy.

It is still unknown which radiotherapy regimen can achieve the best synergistic effect with immunotherapy. Takeshima et al. [24] showed that a single dose of 15 Gy irradiation to tumours implanted in the legs of mice resulted in a significant increase in cytotoxic CD8 + T cells. Irradiation (2 Gy) significantly reduced this effect. Morisada et al. [25] showed that high-dose hypofractionated ionizing radiation (2Í8 Gy) combined with PD-1 blockade will reverse immune resistance and enhance CD8 + cell-dependent primary tumour relapse compared to low-dose ionizing radiation (10Í2 Gy), revealing the potential advantages of hypofractionated radiotherapy. Therefore, our study aims to use short-course radiotherapy to acquire more tumour antigen release and maximize the immune response. This needs to be further confirmed by clinical and basic research.

The conventional preoperative irradiation field includes the rectum and TDLNs [26]. Since TDLNs constitute the main platform for T-cell cross-priming, T cells in lymphoid tissue are extremely sensitive to radiation. Hence, irradiation of TDLNs impairs the antitumour immune response. Buchwald et al. [27] established a modified B16F10 flank tumour model by bilateral subcutaneous injection. Irradiation of local tumours increased the proliferation of total CD8+ T cells and stem-like CD8+ T cells in the TDLNs and improved distant tumour control (the abscopal effect). Simultaneous irradiation of TDLNs will significantly reduce tumour-specific CD8+ T cells and stem cell-like CD8+ T-cell subsets in both irradiated and nonirradiated areas. Takeshima et al. [24] also found that in mice whose TDLNs were surgically removed or genetically deficient (Aly/Aly mice), the production of tumour site-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes was greatly reduced, and the radiotherapy-induced antitumour effect was weakened, which indicated that TDLNs were crucial for the activation and accumulation of radiation-induced T cells. In a study of Ib node-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with node-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy, regional lymph node recurrence was found to be rare in these patients, which means that irradiation of lymph nodes is not necessary [28]. For LARC, conventional irradiation target volume planning is obviously unfavourable for protecting lymphocytes in TDLNs. Tyc-Szczepaniak et al. [29, 30]. use irradiation targeted on the primary tumor and adjacent enlarged lymph nodes plus a 1 cm margin to treat stage IV rectal cancer, 35% of enrolled patients had significant improvement, 63% patients reported significant or complete symptom resolution, suggest that irradiation targeted only at the primary tumor site is a valid option for stage IV rectal cancer. To reduce the negative impact of radiotherapy on immune cells, we should consider the protection of lymph nodes. Therefore, in our study, we used node-sparing short-course radiotherapy to stimulate the differentiation of Tpex cells in TDLNs, resulting in the accumulation of Tex cells in the tumour microenvironment and further increasing tumour regression by combining PD-1 blockade.

There are many complications related to radiotherapy, among which RIF may have a great impact on the function and survival of cancer patients [17]. Postoperative fibrosis, stiffness, and stenosis of the rectum greatly affect the QoL of rectal cancer patients. Radiotherapy is a risk factor for rectal stiffness and stenosis [31, 32]. Conventional wide-field irradiation may cause great damage to the rectum and surrounding tissues, inducing RIF and rectal stenosis. In our study, irradiation limited to the tumour bed possibly reduced RIF and rectal stenosis and improved the QoL of patients receiving TME.

The interval between short-course radiotherapy and TME is still unclear. The common practice was to perform TME within one week after the end of short-course radiotherapy [33]. The short interval strategy resulted in an increased anastomotic leakage [34]. More recently, a long interval of TME after short-course radiotherapy has been widely used to achieve a higher pCR rate and a lower postoperative complication rate [35–37]. In the Stockholm III clinical trial [36], short-course radiotherapy followed by delayed surgery had similar oncological results compared with short-course radiotherapy followed by immediate surgery. Four to eight weeks of delayed surgery was associated with few postoperative complications. In the RAPIDO clinical trial [35], short-course radiotherapy followed by 6 cycles of CAPOX chemotherapy achieved less disease-related treatment failure. In our clinical trial, we conducted 4 cycles of CAPOX combined with PD-1 blockade after short-course radiotherapy. This long-interval protocol may further increase the probability of pCR and reduce the incidence of postoperative complications, such as tissue oedema, anastomotic leakage, rectal fibrosis and stenosis.

In summary, our study provides a new strategy of radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy and immunotherapy for LARC. Specifically, we will study the effectiveness and safety of node-sparing modified short-course radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant treatment of MSS rectal cancer patients. We hypothesized that irradiation of tumours induces neoantigen release, triggering an adaptive antitumour immune response, whereas a node-sparing strategy would increase the differentiation of immune cells in TDLNs and infiltration into the tumour microenvironment. Combination with tislelizumab reverses the function of exhausted T cells. Additionally, irradiation confined to the tumour bed reduces postoperative rectal tissue fibrosis and improves the QoL of LARC patients. Our clinical trial will generate important clinical data on the safety and efficacy of this combination, thus providing new perspectives for neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank BeiGene Co., Ltd., for providing tislelizumab free of charge and for having purchased liability insurance for the patients enrolled in this clinical trial. We also want to thank the following participating centres: Sir Run Run Shao Hospital, Zhejiang University; Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital, Zhejiang University.

Abbreviations

- LARC

locally advanced rectal cancer

- nCRT

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

- TME

total mesorectal excision

- cCR

clinical complete response

- CR

complete response

- ICIs

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- PD-1

programmed cell death-1

- dMMR

mismatch repair-deficient

- MSS

microsatellite stability

- pCR

pathological complete response

- TDLNs

tumour-draining lymph nodes

- Tex

exhausted T cells

- Tpex

progenitor or precursor exhausted T cells

- RIF

radiation-induced fibrosis

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- TRG

tumour regression grade

- LRR

local recurrence rate

- DFS

disease-free survival

- OS

overall survival

- QoL

quality of life

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- TMB

tumour mutation burden

Author contributions

ZS and JD initially designed this study and are the principal investigators of this study; CC and XZ wrote the manuscript; XS, BG and SD was responsible for the treatment plans of modified short-course radiotherapy; JW, LC, EC, XH, WL, and XW performed TME and evaluated the postoperative complications; CC and HW performed the molecular biology experiments; ZS and JD revised the manuscript; LC and XZ coordinated ethics approval; EC coordinated collaboration among researchers across all institutions; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82273265), Zhejiang Committee of Science and Technology (Grant No. GZY-ZJ-KJ-23029) and Major Project of Social Development of Jinhua Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2023-3-100).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shao Hospital, Zhejiang University (Approval number: 2023 − 0386) and by the ethics review committees of all the participating centres. All participants were required to sign written informed consent before participating in the study. The identities of the participants will not be disclosed in any reports or publications.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Cheng Cai and Xia Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jinlin Du, Email: djl9090@163.com.

Zhangfa Song, Email: songzhangfa@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, Martus P, Tschmelitsch J, Hager E, Hess CF, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celerier B, Denost Q, Van Geluwe B, Pontallier A, Rullier E. The risk of definitive stoma formation at 10 years after low and ultralow anterior resection for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen TH, Chokshi RV. Low anterior resection syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haanen JB, Robert C. Immune Checkpoint inhibitors. Prog Tumor Res. 2015;42:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraehenbuehl L, Weng CH, Eghbali S, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(1):37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, Lamendola-Essel M, El Dika IH, Segal N, Shcherba M, Sugarman R, et al. PD-1 blockade in Mismatch Repair-Deficient, locally advanced rectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(25):2363–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cercek A, Dos Santos Fernandes G, Roxburgh CS, Ganesh K, Ng S, Sanchez-Vega F, Yaeger R, Segal NH, Reidy-Lagunes DL, Varghese AM, et al. Mismatch repair-deficient rectal Cancer and resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(13):3271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lizardo DY, Kuang C, Hao S, Yu J, Huang Y, Zhang L. Immunotherapy efficacy on mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer: from bench to bedside. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1874(2):188447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bando H, Tsukada Y, Inamori K, Togashi Y, Koyama S, Kotani D, Fukuoka S, Yuki S, Komatsu Y, Homma S, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy plus Nivolumab before surgery in patients with microsatellite stable and microsatellite instability-high locally advanced rectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(6):1136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Z, Cai M, Zhang P, Li G, Liu T, Li X, Cai K, Nie X, Wang J, Liu J et al. Phase II, single-arm trial of preoperative short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy and camrelizumab in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Itano AA, Jenkins MK. Antigen presentation to naive CD4 T cells in the lymph node. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(8):733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiam-Galvez KJ, Allen BM, Spitzer MH. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(6):345–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fransen MF, Schoonderwoerd M, Knopf P, Camps MG, Hawinkels LJ, Kneilling M, van Hall T, Ossendorp F. Tumor-draining lymph nodes are pivotal in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint therapy. JCI Insight 2018, 3(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rahim MK, Okholm TLH, Jones KB, McCarthy EE, Liu CC, Yee JL, Tamaki SJ, Marquez DM, Tenvooren I, Wai K, et al. Dynamic CD8(+) T cell responses to cancer immunotherapy in human regional lymph nodes are disrupted in metastatic lymph nodes. Cell. 2023;186(6):1127–e11431118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller BC, Sen DR, Al Abosy R, Bi K, Virkud YV, LaFleur MW, Yates KB, Lako A, Felt K, Naik GS, et al. Subsets of exhausted CD8(+) T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(3):326–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A. Tumor draining lymph nodes, immune response, and radiotherapy: towards a revisal of therapeutic principles. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877(3):188704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Wei J, Meng L, Wang H, Qu C, Chen X, Xin Y, Jiang X. Advances in pathogenic mechanisms and management of radiation-induced fibrosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettersson D, Lörinc E, Holm T, Iversen H, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Martling A. Tumour regression in the randomized Stockholm III Trial of radiotherapy regimens for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102(8):972–8. discussion 978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bando H, Tsukada Y, Ito M, Yoshino T. Novel immunological approaches in the treatment of locally advanced rectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2022;21(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Jiang T, Xiao L, Yang S, Liu Q, Gao Y, Chen G, Xiao W. Total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) versus standard Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal Cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2021;26(9):e1555–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoendervangers S, Couwenberg AM, Intven MPW, van Grevenstein WMU, Verkooijen HM. Comparison of pathological complete response rates after neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy or chemoradiation followed by delayed surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(7):1013–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi J, Sun Z, Gao Z, Huang D, Hong H, Gu J. Radioimmunotherapy in colorectal cancer treatment: present and future. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1105180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo I, Lee HW, Byun SJ, Park JY, Min H, Lee SH, Lee JS, Kim S, Bae SU. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation alters biomarkers of anticancer immunotherapy responses in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Takeshima T, Chamoto K, Wakita D, Ohkuri T, Togashi Y, Shirato H, Kitamura H, Nishimura T. Local radiation therapy inhibits tumor growth through the generation of tumor-specific CTL: its potentiation by combination with Th1 cell therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70(7):2697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morisada M, Clavijo PE, Moore E, Sun L, Chamberlin M, Van Waes C, Hodge JW, Mitchell JB, Friedman J, Allen CT. PD-1 blockade reverses adaptive immune resistance induced by high-dose hypofractionated but not low-dose daily fractionated radiation. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(3):e1395996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchwald ZS, Nasti TH, Lee J, Eberhardt CS, Wieland A, Im SJ, Lawson D, Curran W, Ahmed R, Khan MK. Tumor-draining lymph node is important for a robust abscopal effect stimulated by radiotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Chen J, Ou D, He X, Hu C. Sparing level ib lymph nodes by intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19(6):998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyc-Szczepaniak D, Wyrwicz L, Kepka L, Michalski W, Olszyna-Serementa M, Palucki J, Pietrzak L, Rutkowski A, Bujko K. Palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy instead of surgery in symptomatic rectal cancer with synchronous unresectable metastases: a phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyc-Szczepaniak D, Wyrwicz L, Wiśniowska K, Michalski W, Pietrzak L, Bujko K. Palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy instead of surgery in symptomatic rectal cancer with synchronous unresectable metastases: long-term results of a phase II study. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(11):1369–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Li S, Jin X, Wu X, Zhang Z, Shen L, Wan J, Wang Y, Wang Y, Yang W, et al. Protective ileostomy increased the incidence of rectal stenosis after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17(1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu H, Bai B, Shan L, Wang X, Chen M, Mao W, Huang X. Preoperative radiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer: a risk factor for non-reversal of ileostomy caused by stenosis or stiffness proximal to colorectal anastomosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(59):100746–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verweij ME, Franzen J, van Grevenstein WMU, Verkooijen HM, Intven MPW. Timing of rectal cancer surgery after short-course radiotherapy: national database study. Br J Surg. 2023;110(7):839–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparreboom CL, Wu Z, Lingsma HF, Menon AG, Kleinrensink GJ, Nuyttens JJ, Wouters MW, Lange JF. Anastomotic leakage and interval between Preoperative Short-Course Radiotherapy and Operation for rectal Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(2):223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Roodvoets AGH, Nagtegaal ID, Beets-Tan RGH, Blomqvist LK, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erlandsson J, Holm T, Pettersson D, Berglund Å, Cedermark B, Radu C, Johansson H, Machado M, Hjern F, Hallböök O, et al. Optimal fractionation of preoperative radiotherapy and timing to surgery for rectal cancer (Stockholm III): a multicentre, randomised, non-blinded, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glynne-Jones R, Hall M, Nagtegaal ID. The optimal timing for the interval to surgery after short course preoperative radiotherapy (5 ×5 Gy) in rectal cancer - are we too eager for surgery? Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;90:102104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.